Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1346

November 3, 2014

The Boundaries Around Your Industry Are About to Change

Most obviously, the Internet of Things has the power to profoundly change operations — that’s where much of the coverage of this burgeoning network has focused. But companies should also be preparing for profound shifts in their competitive strategies as the IoT takes off. It will change the category you compete in, the products and services you sell, and how you market them, and even the talent you acquire. These three mini case studies will show you just how profound those shifts will be.

Lowes: Right now, most retail IoT home products — thermostats, security systems, lighting — are singular. The market won’t scale if companies can’t help consumers tie these things together and manage them as a unit easily. Lowe’s, the $53-billion U.S.-based home improvement retailer, has hence developed and is marketing a full home management system, called IRIS. According to Kevin Meagher, vice president and general manager for Smart Home at Lowe’s, “Connected home is the first truly new category that Lowe’s has added in nearly 20 years, because we realize that we can add value by bringing these devices together.”

A new category means new skills: Suddenly, many of Lowe’s 240,000 retail employees must be able to talk software and apps, and know how to connect IRIS to all these other products, so the company is training them. At the same time, with 15 million consumers walking through Lowe’s stores every week, Meagher and his team believe that they can — must — play an important role in educating consumers on smart home technology, ease anxiety around standards and reduce customer confusion while providing that unifying product. If they don’t, Lowe’s can envision a scenario in which customers would buy an IoT device from the retailer, then work directly with manufacturers on future services and products — go right to Google for Nest-related products, say.

Longer-term, Lowe’s needs to reinvent the way it markets and sells to consumers. Lowe’s sees a future in which the company is delivering air filters to customers’ doorsteps because IRIS is providing accurate HVAC usage and customers have enrolled in a filter subscription program. Meagher takes it a step further and imagines that Lowe’s could use energy usage data to inform consumers of programs that would save them money with local energy companies. This will require careful stewardship and permissions around consumer data, and expertise around mining the information for new useful services.

Thermo Fisher Scientific: Medical devices companies suddenly find themselves in the software and subscription services businesses because of the Internet of Things. Thermo Fisher Scientific has developed cloud-based genome-mapping devices that allow scientists to subscribe to the computing power they need at affordable rates. The value for Thermo Fisher Scientific is twofold. First, the company can now identify who the end customers are and how those doctors and researchers are using these devices. Second, this new explosion of analytics on healthcare research has opened a new line of business around aggregating the results and selling access to curated views of large datasets.

Of course, that means that a medical device company that’s used to focusing on procurement groups who bought their devices en masse is now focused on the actual end users of their devices. A company with a strong legacy of device product managers and engineers, Thermo Fisher Scientific had only one software product manager when its new cloud-enabled genome-mapping tools launched. The company is now making considerable investments to bring on additional people in fields and with skill they’d never focused on to expand into the new lines of business. This includes digital product managers and data scientists.

All Traffic Solutions: A traffic sign manufacturer is a natural for Internet of Things adoption. Ten-year old All Traffic Solutions made the strategic shift to put sensors into its products to track traffic flow data. More than 25% of All Traffic Solutions revenue comes from TraffiCloud, a web-based application that uses connected sensors to collect traffic data and transmits that data to a centralized database letting users (often municipalities) generate relevant reports.

Ted Graef, President of All Traffic Solutions, says one of the biggest challenges his company faced was aligning its sales team around the shift from selling hardware to selling hardware bundled with software services. The company conducted a number of experiments with pricing and marketing until they found what made sense to their customers and their sales channels. Ted says, “We learned very quickly that bundling promotional pricing and providing onboarding training sped up adoption of our services.” All Traffic Solutions hired a team to provide introductory training for customers on setting up and using TraffiCloud. The investment in onboarding, a totally new skill for the company, has resulted in 70-80% renewal rates for the service.

Lest you think these companies are just organically building these new skills and entering these new kinds of businesses, that’s not necessarily the case. Huge shifts in strategy and culture like these can be slow, costly, or frankly, too difficult to pull off organically. CEOs and senior executives are looking outside their organizations for help in making the transition. In fact, new businesses are developing to help companies make the leap. They’re turning to startups like Sprosty, which helps companies with market research on consumers’ feelings, business strategy, and product development in IoT technology. Another company, Zuora, has helped companies build and scale subscription businesses, and understand its dynamics like billing, renewal rates, and customer churn.

There is no single path to success with selling and marketing smart, connected devices. This third wave of IT-driven innovation is reshaping industries and redrawing the lines of competitive rivalry. Companies need to identify which skillsets they want to hire, acquire or outsource to partners. The goal is aligning closer to consumers and building ongoing relationships. The distinctions between industries will become less pronounced than the differences between market leaders and laggards within the same categories.

The World Is Still Not Flat

Globalization marches on. But the pace isn’t all that fast, and the overall level of global connectedness still hasn’t gotten back to its all-time peak of 2007. The overwhelming majority of commerce, investment, and other interactions still occur within — not between — nations.

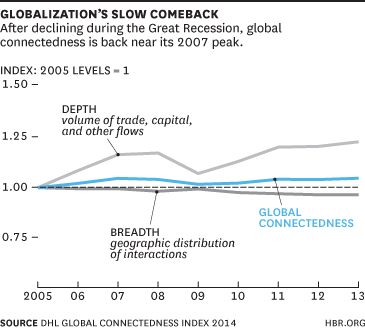

That’s the message from the just-released DHL Global Connectedness Index 2014, which combines measures of trade, capital, people, and information flows to give a picture of how entwined we citizens of the world are with each other. Here’s the headline chart, with the subindexes for “depth” (the volume of flows) and breadth (how widely distributed the flows are among different countries):

The index is compiled by Pankaj Ghemawat, a professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business and the IESE Business School in Barcelona, and Steven Altman, a lecturer at IESE. Ghemawat, a frequent HBR contributor, began arguing in 2007, with the book Redefining Global Strategy, that the world isn’t nearly as flat as Tom Friedman said it was. As he put it that year in Foreign Policy magazine:

Despite talk of a new, wired world where information, ideas, money, and people can move around the planet faster than ever before, just a fraction of what we consider globalization actually exists. The portrait that emerges from a hard look at the way companies, people, and states interact is a world that’s only beginning to realize the potential of true global integration. And what these trend’s backers won’t tell you is that globalization’s future is more fragile than you know.

The financial crisis of 2008 and subsequent global recession demonstrated that fragility, as trade flows shrank dramatically. And in 2011, after Ghemawat published another globalization book, World 3.0, global logistics giant DHL asked him to put together an annual index of globalization’s progress (or regress). When I asked Ghemawat if it wasn’t a little bit weird for a champion of globalization like DHL to commission such research from a globalization skeptic, he laughed and said, “If the world were already connected, they couldn’t trumpet what a role they play in connecting it.”

The big news in the chart above, other than global connectedness getting back close to its 2007 peak, is that the breadth of connectedness is still declining. Breadth is a measure that reflects how many different countries a particular country is interacting with and the distances over which interactions occur, among other things. So the tourist trade in the Bahamas, while it scores high for depth because there are lots of tourists, doesn’t have much breadth because more than 80% of them come from one country, the U.S., that is less than 200 miles away and accounts for less than 10% of the world’s outbound tourists.

This global decline in the breadth of connectness, Ghemawat says, suggests that “with the big shift in economic activity to emerging markets, the world is in some sense getting pulled apart.” For the past couple of decades, globalization been largely driven by trade, investment, and other interactions between developed countries and developing ones. Now the action is among the developing countries (and formerly developing countries), which is having the effect of re-regionalizing many economic flows. South-to-South trade is now growing faster than South-to-North or North-to-South, Ghemawat says, while North-to-North trade “has basically stagnated.”

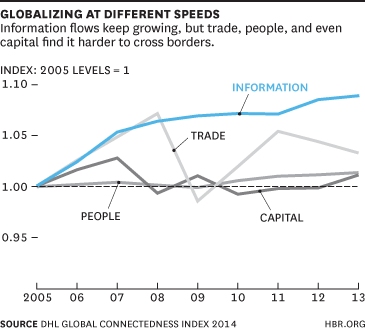

The index’s different “pillars” of connectedness have also followed different trajectories over the past decade:

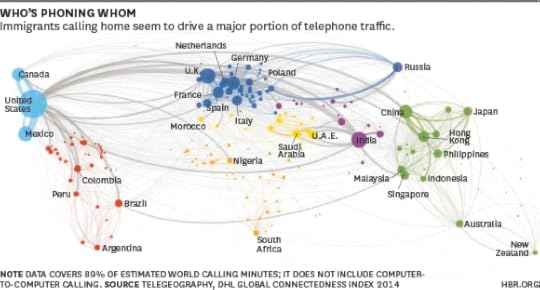

Trade, as already noted, took a big hit and has now rebounded. The number of people studying or working outside their home country hasn’t changed much, while the information index has been rising fast. (The capital measure is a moving three-year average, because otherwise it would be too volatile to make sense of.) But the information flows have been rising from a pretty low base: Less than 20% of internet traffic crosses borders, and fewer than 5% of telephone calls do. The international calls that are made tend to follow immigration routes:

Of the international calls measured here, 41% are made from advanced economies to emerging ones. The route with the most calling minutes, by far, is from the U.S. to Mexico, and second is the U.S. to India.

So the world is still far from flat. And it’s not even getting that much flatter.

The Rise of the Rude Hiring Manager

When his three-hour board interview ended with an offer to join the executives for a beer, 35-year-old Martin* figured he’d nailed the job. He had spent the last two months interviewing for a position as director of operations at a sporting goods company. His resume was spot-on — he’d spent five years as a sporting goods sales rep and several years as an operations manager doing “everything from ordering for shops, to speaking with dealers, to sales.” Senior management at the new company knew him, his successful track record, and the companies he’d worked for. Slam dunk, right? Wrong.

Martin had participated in five interviews, between which he managed myriad back-and-forth e-mails and deliverables. At the company’s request, he created and submitted a five-year business plan and a master list of vendors and buyers. He was asked to explain his strategies for expanding distribution and introducing new products to market. At the time, Martin had felt uncomfortable about offering so much proprietary information to a company for whom he did not yet work, but colleagues who’d more recently been in the job market told him, “This is how the interviewing process works these days — you jump through hoops.” Martin decided he wanted the job, and if he had to give up the keys to the car to get it, he was going to hope for the best.

But after months of interviews and assignments, Martin said, “Instead of making me an offer, they told me they had to make a ‘really tough decision’ and ‘decided to move in a different direction’” — that direction was giving the position to the most junior board member, who lacked any hands-on experience. “We hope this won’t affect our relationship,” they told him. And with months of his “life down the drain,” but knowing that he worked in a small community, Martin felt obliged not come off as a sore loser. “But the fact of the matter is, I got taken.” His goal today? “To ruin this company.”

Maybe you’re thinking that Martin just didn’t know how to play his cards right. Or that maybe, in the end, he simply wasn’t the best candidate for the position. But Martin is not alone. His utter frustration over the hiring process is pretty much par for the course these days. This type of behavior is happening more and more often. Ask five acquaintances about recent hiring experiences and I bet you’ll encounter one friend who personally has suffered something similar. Data compiled for The New York Times by Glassdoor found that an average interview process in 2013 lasted 23 days versus an average of 12 days in 2009. And time-consuming assignments and auditions for candidates as chronicled in the stories here, and here, and here, are the new normal.

This problem is the result of several factors:

Fear of decision-making. Back when I was hiring people as an executive at a large business, I’d solicit candidates, look at a batch of resumes, decide who had the requisite skills on paper, and then interview the top three or four. Each interview lasted about 30 minutes. I had my standard set of questions that probed their personalities, attitudes, ambitions, skill set, and prospective fit with the company ethos. If two potential hires seemed close, I’d have a breakfast with each and then make a decision. And I personally wrote everyone who didn’t get the job. This wasn’t rocket science.

I can’t pinpoint exactly when the hiring process went off the rails, but I believe it began in the late 90s, when cost cutting became a mania and headcount was slashed to the bone, requiring every employee to do the work of many. With so little margin for error, every hire became a fraught decision, and the fear of making a mistake loomed larger and larger. To protect themselves and validate their choices, managers began to seek more and more “evidence” of their thoroughness in vetting their hires. New hurdles were added until someone interested in a director-level position, such as Martin, is now routinely required to submit the kind of analysis and proposals that were once the province of in-house executives or paid consultants.

A culture of rudeness. Rachel, a 60-year-old former news producer turned freelance marketer, was introduced by a friend to the CEO of “a fast growing ‘deep content’ company with clients like GE and Xerox.” The company seemed like a good fit for Rachel’s portfolio of skills, and employed a large staff of experienced journalists, artists, and web designers. After a brief phone conversation, the CEO wanted to meet with Rachel “ASAP.” During their first in-person conversation, Rachel and he discovered shared viewpoints, and after talking for an hour, the CEO asked Rachel to meet with his editorial VP. But first, the CEO gave Rachel his card. “This is my direct line,” he said, “and I return every call on this line. Call me by the end of the week.” Rachel did as requested. Six weeks later, after several awkward interactions with the CEO’s assistant, he finally took Rachel’s call.

CEO: “Hi Rachel, I’m too busy to talk today.”

Rachel: “I understand —maybe Monday?”

CEO: “Well, I can’t commit to that right now, either. And I need to tell you, it doesn’t inspire me that you’ve been calling so much.”

Rachel: “On the day we met you asked me to call you two days later. That was six weeks ago. I’ve called less than once a week.”

CEO: “Well, every time you call your name doesn’t go to the to top of the list – it moves to the bottom! This doesn’t mean I’ve lost interest in you and your work, but it’s not cool to do what you’re doing.”

Rachel: “I understand. I won’t call again. Thank you.”

The colleague who set up the initial contact told Rachel: “There is no bad intent here — like me, he gets 300 emails a day and works 18-hour days across five continents. It’s not personal.”

I wrote a book about emotion in the workplace called It’s Always Personal. And no matter what others say, it nearly always is. People hiring today have precious little time to read, process information, and respond to even urgent issues like staffing. But this comes at great peril to their organizations and to the rude employer. Instead of fostering good will among the prospective hires they interview, enemies like I-live-to-see-this-company-destroyed Martin are made.

My time is more important than your time. An author I know was approached by a publisher to write a book for which the publisher had decided there was a market. The writer was asked to write a proposal, but wasn’t told that he was only one among many other people from whom they’d solicited proposals until midway through the process. That process took “months and months and months,” he says, and “it was always a hurry-up-and-wait situation, where they made me jump through hoop after hoop — every one of them a last-minute-need-it-immediately kind of thing. And then I’d hear nothing for weeks.” When his proposal was finally accepted, they wanted the finished book in six weeks. “It took them about eight months to make a decision to accept the proposal — which, by the way, was their idea in the first place, and which they had approached me about — and then they expected me to just whip the entire book out of thin air in six weeks? What’s wrong with these people?”

This is happening to almost everyone I know looking for any kind of work, even those who have been invited into the process — freelance, contract, full-time. The prospective employer/client needs everything now and then it’s radio silence for days, weeks, months — leaving the prospective supplier/employee in the unenviable position of feeling like they must beg for feedback. During the last decade, it became acceptable behavior to simply not answer e-mails. But that’s the worst kind of ego-sucking, demoralizing power play imaginable. We’re all busy. That’s no excuse for disrespect. And the awful truth? I don’t think the employers have a clue. Fearful of losing their own jobs by making a wrong choice, they’ve lost perspective on what matters.

So what’s lost amid all these changes?

At a time when the buzzwords in corporate America are innovation, disruption, and game-changers — all actions that require recruiting the best talent in the marketplace — organizations, instead, are artificially creating bureaucratic inefficiencies that are inexcusably cumbersome and that result in the creation of legions of antagonists. It’s a waste of human capital, it’s a huge waste of everyone’s productive time, and it damages the reputation of an organization and the individual doing the hiring. Jobs are scarce enough, and the general economic vibe is insecure enough that companies and managers believe that they can be cavalier about how they treat people outside the organization — but in this thinking lies madness. Now that 20th-century-style employer loyalty and benefits are a thing of the past, employees return the disfavor, churning through organizations at a rapid clip. If a typical new hire is only going to stay at a company for two to four years, why sweat the decision so much? Be responsive. Act fast. Trust your gut.

Employers need to streamline the hiring process, calling upon both common sense and basic good manners. Here are six easy actions:

Make the process transparent from the outset for prospective hires

State the timetable for making a decision

Offer updates if the process extends beyond that timeframe

Limit the “tryout” requirements — proposals, plans, original work — and make the deliverables clear at the start of the process

Make the timeframe for submitting any materials reasonable — 3 to 5 business days, never tomorrow

Make certain that everyone who’s being considered for a position is given the courtesy of a definitive response within the stated timeframe. Just as e-mail has compounded our daily load, so too does it liberate us from making those hard calls person to person. Use the tool to your advantage.

The wildly successful actress/producer/director Lena Dunham perhaps said it best in a recent interview: “I’m never going to be the person who lets e-mail and voicemail sit for weeks — I’m going to be the person who responds, even if the answer is no.” How refreshing.

*Names have been changed

October 31, 2014

Governing the Smart, Connected City

As politics at the federal level becomes increasingly corrosive and polarized, with trust in Congress and the President at historic lows, Americans still celebrate their cities. And cities are where the action is when it comes to using technology to thicken the mesh of civic goods — more and more cities are using data to animate and inform interactions between government and citizens to improve wellbeing.

Every day, I learn about some new civic improvement that will become possible when we can assume the presence of ubiquitous, cheap, and unlimited data connectivity in cities. Some of these are made possible by the proliferation of smartphones; others rely on the increasing number of internet-connected sensors embedded in the built environment. In both cases, the constant is data. (My new book, The Responsive City, written with co-author Stephen Goldsmith, tells stories from Chicago, Boston, New York City and elsewhere about recent developments along these lines.)

For example, with open fiber networks in place, sending video messages will become as accessible and routine as sending email is now. Take a look at rhinobird.tv, a free lightweight, open-source video service that works in browsers (no special download needed) and allows anyone to create a hashtag-driven “channel” for particular events and places. A debate or protest could be viewed from a thousand perspectives. Elected officials and public employees could easily hold streaming, virtual town hall meetings.

Given all that video and all those livestreams, we’ll need curation and aggregation to make sense of the flow. That’s why visualization norms, still in their infancy, will become a greater part of literacy. When the Internet Archive attempted late last year to “map” 400,000 hours of television news, against worldwide locations, it came up with pulsing blobs of attention. Although visionary Kevin Kelly has been talking about data visualization as a new form of literacy for years, city governments still struggle with presenting complex and changing information in standard, easy-to-consume ways.

Plenar.io is one attempt to resolve this. It’s a platform developed by former Chicago Chief Data Officer Brett Goldstein that allows public datasets to be combined and mapped with easy-to-see relationships among weather and crime, for example, on a single city block. (A sample question anyone can ask of Plenar.io: “Tell me the story of 700 Howard Street in San Francisco.”) Right now, Plenar.io’s visual norm is a map, but it’s easy to imagine other forms of presentation that could become standard. All the city has to do is open up its widely varying datasets.

A third key development will be some form of unique identifier for citizens. When cities know who they’re talking to, and what the context of the citizen’s relationship to the city includes, more deeply relevant communications become possible. This month’s launch of MIT Media Lab’s Laboratory for Social Machines, aimed at studying large-scale civic issues using Twitter data (and backed by a major investment from Twitter itself), may provide a starting point for the study of voluntary civic engagement along these lines. Deb Roy, who leads the effort, points out that citizens in the tiny town of Jun, Spain, are able to schedule health appointments and reserve city hall conference rooms using their Twitter monikers.

We still have a long way to go until we can realize any of these possibilities. For starters, the privacy implications of ubiquitous, identified streaming have yet to be fully explored. But one thing we know: humans want to share, humans love their cities, and government has to change to serve human needs better. We’ll need both better policies and better technology to make the invisible electronic layer of cities visible to us all. Because only when we can see something can we make progress.

Coworkers Should Be Like Neighbors, Not Like Family

All companies want engaged employees. After all, people who are engaged put in effort that goes above and beyond the minimum that’s required to complete a task. They are less likely to look for another job. And they project positive energy, which improves the mood of other employees and customers.

One way to increase engagement is to foster a “neighbor” relationship.

Research on types of relationships suggests that we can break the world up into several kinds of relationships. I refer to the three that are particularly important in the context of business as strangers, family, and neighbors.

Strangers are people with whom we do not have a close connection; if we need their help, we pay them to provide it. Families are people with whom we have a close bond and for whom we do whatever is needed, often expecting nothing in return. In between strangers and family are neighbors — people with whom we have a reasonably close relationship, who offer us help, and expect help in return.

It’s not good to have a workplace that consists primarily of strangers, because every interaction becomes a fee-for-service transaction and strangers are not motivated to go above and beyond the specific tasks presented to help the organization fulfill its goals. Moreover, the social environment in a workplace full of strangers does not energize employees to want to come to work.

Likewise, it’s dangerous for most organizations to function as a family, because not all employees will pull their own weight. It’s an inefficient and demoralizing way to work.

But with our neighbors, we try to balance what we do for them and what we get from them over time. We construct covenants in which everyone shares a common vision and agrees to do what they can to work toward these common interests.

In a healthy workplace, neighbor-employees work hard, secure in the knowledge that the organization is looking out for them. The organization succeeds because its employees put in a reasonable amount of extra time and effort for each other.

There are several ways to promote a neighborhood in the workplace. At the core of each of these techniques is a demonstration that the organization has a broader vested interest in its employees. This reassurance is particularly important for publicly traded companies that are normally focused on improving earnings each quarter.

One way to support neighborhoods is training. Many companies provide extensive training opportunities for their employees, which give them a chance to develop both work-related and personal skills. This demonstrates that the organization is interested in the employees’ long-term best interests. Any investment in those training opportunities pales in comparison to the cost of replacing people who leave the company.

A second way to promote a neighborhood is to provide regular opportunities for employees to engage directly with higher-ups. Being a part of the neighborhood requires a feeling that the organization knows who you are and cares not just about people in general, about you in particular. Without some points of contact to the upper management of the company, a business unit might become a neighborhood, but that neighborhood may feel disconnected from the rest of the organization.

A third component of the neighborhood is that it needs to have a shared purpose. Residential neighbors are bound together by the desire to create a community that benefits the people who live there. Similarly, companies need a shared vision that transcends the individuals. For example, at the University of Texas (where I work), I have worked with our operational staff to help the various units (like construction, emergency services, and power) to reconnect with the mission of the university in order to make those units feel like a more central part of the neighborhood.

Finally, it’s important for all managers to look for signs that an organization is slipping from a neighborhood to a group of strangers. The biggest signal that a neighborhood is eroding is when employees start finding reasons not to support broader initiatives within the organization because of the narrower job that they have been assigned. They may give excuses for focusing on their particular job instead of what the larger organization needs. When this happens managers need to return to the above approaches, demonstrating that the organization cares about them and remind them of their connection to the broader mission.

Although it does require effort and resources to maintain a neighborhood, the investment is quickly repaid.

How the Market Ruined Twitter

There was a time when Twitter could be described as “plumbing.” Now the best description might be, “giant bank account with a company attached.” It’s hard not to see this as a big step backwards, and to wonder whether the standard venture-capital-to-public-company trajectory is turning out to be entirely wrong for an enterprise like Twitter.

Let me explain, starting with the plumbing. The quote comes from author, tech thinker, and now public-TV personality Steven Johnson: “The history of the Internet suggests that there have been cool Web sites that go in and out of fashion and then there have been open standards that become plumbing,” he told David Carr of The New York Times in January 2010. “Twitter is looking more and more like plumbing, and plumbing is eternal.”

As Johnson had described it in much more depth in a Time cover story a few months before, what made Twitter so promising and interesting and important was “the fact that many of its core features and applications have been developed by people who are not on the Twitter payroll.” Most of its conventions (the hashtag, for example) had been developed by users. And “the vast majority of its users interact with the service via software created by third parties.” It was basically an open-source enterprise, and seemed to owe most of its remarkable success to that openness.

Of course, that “success” didn’t come with a lot of revenue. For its first four years, Twitter was able to keep the servers running thanks to mainly to $150 million in funding from venture capitalists and angel investors. Then, after a few of those investors ousted co-founder and CEO Ev Williams in a boardroom coup late in 2010, Twitter raised another $1.2 billion in less than a year. Not surprisingly, the company stopped glorying in the openness of its ecosystem not long after that. Spooked by investor/entrepreneur Bill Gross’s attempt to build a sort of shadow Twitter by buying up the most popular third-party apps, Twitter began cracking down on those third-party software purveyors and taking control of its relationship with users (in order to better “monetize” them). It’s still the users whose creating and sharing gives Twitter its value as a business, but their activities are now mostly channeled and managed by the company itself. And while Twitter has taken some limited steps lately to win back outside app developers, the bigger news has been its apparent intent to move away from its simple chronological timeline to use algorithmic methods to determine what users see, as rival Facebook has done for years.

This incipient change has met with a hugely negative reaction among Twitter users, who seem to want to keep things just the way they are. As a pretty regular Twitter user, I have that kneejerk reaction, too. But keeping things just the way they are seems like a bad idea in today’s rapidly evolving digital environment. If Twitter were still open to such contributions, entrepreneurs and hackers would probably be experimenting feverishly with new ways to present the timeline, and users would likely be trying them out rather than complaining. But when Twitter itself does this, it feels to users like Big Brother is messing with their world. It’s no longer a user-created ecosystem. It’s just a company, trying to make some money.

Now it is true that Facebook acts in Big-Brother-like fashion all the time, and despite incessant complaints over the years it has proved remarkably successful at keeping users engaged. Twitter started in a different place, though, and its users have different expectations. The company has piles of money — $3.6 billion in cash and short-term investments — and my sense from looking at the numbers for the past couple of quarters is that it could probably be making some money, too (that is, generating positive free cash flow), if that were a priority. But the priority is instead growing fast enough to generate adequate returns on the $4 billion-plus (the company raised another $1.8 billion in its 2013 IPO) that investors have plowed into it. And the company’s latest (Oct. 27) earnings report doesn’t really show that kind of acceleration. “They’re not yet able to generate the kind of topline growth we’d normally expect to see in a company with the asset size they’ve got,” analyst James Gellert of Rapid Ratings International told Forbes after the earnings came out. As I write this, the company’s stock price is down 44% from its peak last December.

In the early days, Twitter clearly owed much of its growth to its open, ecosystem-like approach. That growth would have slowed eventually in any case, but it’s hard not to think Twitter’s prospects as a network and as a societal force would be much greater if it had remained more like an ecosystem and less like a conventional corporation. I think there’s at least a chance that Twitter, Inc., would have brighter prospects under that scenario, too, but that’s easy for me to say. I’m not one of those investors who poured $4 billion into Twitter over the past four years and now understandably want the company to figure out how to make lots of money, pronto.

Could Twitter have chosen not to follow the standard VC-to-IPO path that has brought it to this pass? It would have taken a great degree of self-abnegation on the part of the founders, and a remarkable ability to resist Silicon Valley peer pressure. But there are alternatives. Many companies over the decades that have simply chosen to take things a bit slower and not become entirely beholden to outside investors. Ello, the new anti-Facebook that has gotten a lot of attention and $5.5 million in VC funding in the past few weeks, has organized itself as a public-benefit corporation with a charter that says it will never accept advertising. WordPress operates as an open-source ecosystem with a venture-backed corporation, Automattic, at its heart. The Internet itself is a giant cooperative endeavor that allows lots of companies to make gobs of money but most likely wouldn’t work at all if it were controlled by one of them.

At every corporation there are tensions between the demands and needs of shareholders and those of employees, customers, and other stakeholders. But many of the most important new enterprises of the digital age are especially dependent on their users — a group of people who are neither customers nor employees but often seem to generate almost all the enterprise’s value. Fitting such organizations into the shareholder-dominated straitjacket that is the publicly traded corporation could be more than just irritating to these users. It might also be really bad business.

It’s Not HR’s Job to Be Strategic

Human-capital issues are top-of-mind for CEOs around the world — but their regard for the HR function remains perilously low: In a PwC study, only 34% said that HR is well prepared to capitalize on transformational trends (compared with 56% for finance).

Sadly, chief executives aren’t the only ones with this negative perception. It’s pervasive in organizations — and to make matters worse, HR practitioners have inadvertently played into it. In its “State of Human Capital” report, McKinsey found that people in HR still largely have “a support-function mindset, a low tolerance for risk, and a limited sense of strategic ‘authorship’” — all of which has led to “low status among executive peers, no budget for innovation, and a ‘zero-defects’ mentality.”

Though many HR managers would take exception to those findings, they do, overwhelmingly, want more of a strategic voice than they have now. Look at any HR discussion forum, and you’ll find some version of this question: How can HR get a “seat at the table” and become a strategic business partner?

I’m going to suggest that HR — at least in its current form — shouldn’t be a strategic partner. A few months ago, Ram Charan proposed splitting HR into two parts: one to oversee leadership and organization, and one to handle administration. That was a useful conversation starter. But companies should dice up the function even more finely. Instead of grouping all the people-related activities together under HR, businesses should organize them according to types of service provided — and move a couple of them to other functions altogether.

Consider Deloitte’s service delivery model, which divides activities into four categories: site support, transaction processing, center of expertise, and business partner. In this model, the bulk of HR services fall into the first three categories, where a cost-cutting mindset makes a good deal of sense. Examples include payroll, benefits, risk and compliance, and labor relations.

But talent acquisition and learning and development are altogether different — and they should never be done on the cheap. These areas fall under the fourth rubric, business partner, because their managers need a strong understanding of strategic priorities in order to recruit, prepare, and engage employees to meet them. These managers also bring a valuable perspective to the table. Together, they understand labor market trends and instructional design, which can inform a company’s strategy to “build” or “buy” talent.

First let’s look at talent acquisition. It’s critical to bring in the right people to drive the business forward. The thing is, the labor markets and relevant skills vary widely from function to function. Smart recruiting requires an intimate understanding of the work to be done and the skills needed, as well as the function’s business plan (to forecast demand). That’s the specialized insight required to develop the right sourcing and recruiting strategy. HR often centralizes talent acquisition in order to minimize costs, and that’s short-sighted. Saving a few hundred dollars per hire may seem like a quick win, but a bad hire can cost more than $50,000.

For its part, learning and development should enhance employees’ ability to further the company’s mission, mold future leaders, and build strong teams. But companies aren’t seeing it as the strategic opportunity it is — and that’s because of its placement in HR. I recently spoke with an HR executive at a Fortune 500 packaging firm in the Midwest whose annual budget for the entire high-potential development program was $10,000. That is not a vote of confidence.

You can see this low-value mindset play out in other ways. HR managers adore e-learning, for instance, since they have been conditioned to evaluate everything on cost and scalability. Indeed, according to the Association for Talent Development, nearly 40% of corporate training in 2013 was delivered through technology, and that number is projected to grow. Unfortunately, a lot of e-learning is just plain awful. My company recently surveyed 525 Millennials (people born after 1979) to understand their views on learning and leadership development. Though e-learning was among the most prevalent forms of leadership training, it ranked among those with the least impact — and it was the least desired among all other options. Tech-savvy Millennials are the most likely leaders-in-training to embrace e-learning, yet even they don’t.

Companies will really start feeling the consequences over the next decade. Millennial Branding and Monster.com found that one-third of Millennials rank training and development opportunities as a prospective employer’s top benefit. Cutting corners in this area may jeopardize employee engagement and retention in a demographic that will represent 75% of the U.S. labor force by 2025.

A centralized HR department is ill equipped to address this. But embedding learning and development — along with talent acquisition — within each business function can solve the problem because it will shift the focus from cost reduction to value creation.

By reorganizing HR activities along the lines of the service delivery model, companies can free their cost-focused services to provide excellent support without having to grapple with illusions of strategic grandeur. And they can empower the truly strategic services — talent acquisition and learning and development — to create value without having to view every decision through a cost-cutting lens. At the moment, business leaders are searching for a strategic partner to help them navigate the critical human-capital issues that will make or break their companies. The time has come to give them not one partner, but two.

Identifying the Biases Behind Your Bad Decisions

By now the message from decades of decision-making research and recent popular books such as Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow should be clear: The irrational manner in which the human brain often works influences people’s decisions in ways that they and others around them fail to anticipate. The resulting errors prevent us from making sound business and personal decisions, even when we’ve accumulated abundant work experience and knowledge.

Unfortunately, even though we know a lot about how biases like overconfidence, confirmation bais, and loss aversion affect our decisions, people still struggle to counter them in a systematic fashion so they don’t cause us to make ineffective, or poor, decisions. As a result, even when executives think they are taking appropriate steps to correct or overcome employee bias, their actions often don’t work.

What’s the solution? Behavioral economics — the study of how people make decisions, drawing on insights from the fields of psychology, judgment and decision making, and economics — can provide an answer. Since it is so difficult to rewire the human brain in order to fundamentally undo the patterns that lead to biases, behavioral economics advocates that we accept human decision-making errors as given and instead focus on altering the decision-making context in ways that lead to better outcomes. Managers can use this knowledge to improve the effectiveness of a process or system inside their organizations.

Just as an architect thinks carefully about how to best design environments and physical spaces to avoid inefficiencies, managers can adopt choice architecture. Choice architecture, a term used by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their 2008 book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, refers to the way in which people’s decisions can be influenced by how choices are presented to them. Once managers consciously recognize the flawed thinking that is part of human nature, they can find ways to better design decision-making contexts.

But how to do this? Let’s consider an example. Maybe you remember how on Seinfeld, George Costanza would leave his car parked at the office on purpose, so that his boss would think he was working long hours. That’s an attempt to take advantage of what psychologist’s call input bias — the tendency to use signs of effort to judge outcomes, when actually the two may have little to do with each other. In this case, Costanza uses the bias to his advantage, to change the way his boss judged his productivity.

But knowing about this bias can also help managers enhance organizational effectiveness. For instance, by identifying important elements of the “choice architecture” that improves customer experience. In a recent paper, scholars Ryan Buell and Mike Norton (both at Harvard Business School) studied ways in which service organizations could improve customer satisfaction. They found that when a company visually showed the effort it exerted during transactions, customers were more likely to be satisfied while waiting for the service. When people can see the effort expended on their behalf in the delivery of a service — what Buell and Norton call “operational transparency” — they not only mind waiting less, but they actually value the service more.

Here’s how it works. In one of their studies, Buell and Norton created a fictitious travel website and asked people to search for a flight from Boston to Los Angeles. Some people saw a typical progress bar slowing being colored in, but others experienced operational transparency: The site showed each airline it was searching — “Now searching delta.com… Now searching jetblue.com…” — and created a dynamic running tally of the most affordable flights. Although all participants then received the same list of flights and fares, those who experienced this transparency rated the service much more highly than those who simply viewed the progress bar. And when asked to choose between a site that delivered instant results or one that made them wait, but showed its work, most people chose the latter.

To take another example, consider the default bias: To avoid the discomfort of complex choices, individuals usually opt for the default supplied to them even when choosing the alternative does not require much effort. Knowledge of this bias has led to a growing trend among employers to use defaults when presenting their employees with the choice of whether or not to save for retirement in an employer-sponsored savings plan. Companies are increasingly enrolling new hires in pension schemes automatically; individuals need to explicitly opt out if they are not interested in saving for retirement. Because automatic enrollment policies recognize the human tendency to procrastinate taking an important action, even when that action is personally beneficial, such policies lead to large increases in participation in retirement plans.

What these examples suggest is that insidious biases are often the main cause of ineffectiveness in organizations. But they also highlight that knowing about the existence of these biases and how they operate can lead to effective solutions to organizational problems. We commonly think of leaders as managers. But managers should also be architects who look for opportunities in the way work is structured to improve behavior to the benefit of individuals, customers, and the organization. (See our previous articles “To Change Employee or Customer Behavior, Start Small” and “Experiment with Organizational Change Before Going All In.”)

There are two steps to follow in order to accomplish this systematically. First, it is important to understand the main source of the organizational problem under consideration. Is the problem primarily driven by insufficient motivation or by the presence of cognitive biases?

For instance, let’s imagine your team is late in delivering a product to an important customer. Talking to those working on the team may reveal that they do not feel engaged at work (pointing to a motivation issue). But it may also reveal members made overconfident predictions on their ability to deliver on time (thus pointing to a cognitive-bias issue). If the latter is the case, the solution may be to automatically increase the time that a team predicts it will take it to carry out the work — an approach that has succeeded at Microsoft.

Second, managers need to carefully consider the costs and benefits of possible ways to change the choice architecture, in order to reduce or eliminate the bias. In some cases, the solution may consist of changing the process in order to force the individuals in question to deliberate more before making a decision. For instance, in the case of group decisions, the leader may assign a member to be a devil’s advocate or the person who asks tough questions (e.g., Is there any data suggesting that the course of action we want to take is not the right one?). Or, the leader could just create opportunities for the members to reflect and examine whether their actions are aligned with their plans. In other cases, it may be best to create a new process — like the default discussed above — that automatically takes care of the bias.

These two steps can help executives mitigate biases that prevent their businesses from achieving greater success.

October 30, 2014

Is the Corporate Campus Dying?

Jennifer Magnolfi, Founder & Principal Investigator at Programmable Habitats LLC, on how digital work, and the Internet of Things will fundamentally change the how we use the buildings and neighborhoods we work in. For more, read the article Workspaces That Move People.

Put the “and” Back in “Sales and Marketing”

Nowhere else in the executive suite of a typical corporation are two functions as closely intertwined as sales and marketing. Yet for all the shared responsibility, the marketing and sales relationship has often been a contentious and lopsided one, with sales dominating in B2B sectors while marketing leads in B2C ones.

The joint challenge today for CMOs and heads of sales (or CSOs – Chief Sales Officers) is how they can work together to discover insights that matter, design the right offers and customer experiences based on those insights, and then deliver them effectively to the right people across multiple channels to drive growth. McKinsey research shows that companies with advanced marketing and sales capabilities tend to grow their revenue two to three times more than the average company within their sector.

But to get to that top tier, marketing and sales executives can no longer afford the inefficient silos that have long characterized the relationship. Here are three important elements of the CMO-CSO partnership to get right:

1. Build a joint local strategy. CMOs and sales leaders need to become experts at identifying and tapping micromarkets where there are often significant overlooked growth opportunities. But the real power of the partnership comes from their ability to bring the best of each of their departments—as well as pricing, operations, and other groups—to bear in exploiting those micromarket opportunities.

While that might sound obvious, heads of sales tend to set their goals geographically while CMOs often target segments, making it difficult to have a common baseline for comparing and checking progress. Leaders need to focus on how to create meaningful targets that use the best of each approach.

Consider the case of an Asian telecommunications company that found 20 percent of its marketing budget was being squandered in markets with the lowest lifetime customer value. The company shifted resources to its most lucrative markets, where two-thirds of the opportunity lay. Marketing then partnered with sales to reset customer acquisition goals at each micromarket, basing them on each market’s potential. They set, and met, revenue targets that were 10 percent higher than in previous years.

The CMO and head of sales should take the lead in pulling their departments together to jointly identify the best growth opportunities and translate the resulting insights into tools and plans the marketing and sales teams can use.

One important way to focus the effort is by managing the sales pipeline together. “It is very important for the head of sales and the CMO to have ongoing discussions about pipeline strategy and how the pipeline gets built,” says Linda Crawford, EVP and GM, salesforce.com. “People nailing that are taking the lion’s share of the business these days.”

We have found that when this process works well, marketing often takes on an expanded role by, for example, providing sales with data analytics and by supporting the development and testing of sales plays for a specific micromarket or customer peer group.

2. Collaborate around the customer decision journey. “Because customer expectations have changed so much, it’s even more important that marketing, sales and even service work closely together,” says Lynn Vojvodich, CMO for salesforce.com “Ultimately, you want to create personalized customer journeys that seamlessly integrate touch points across these functions.” The best CMOs and sales leaders are putting mechanisms in place to create a consistent experience for their customers, and identifying which marketing and sales investments will yield the greatest returns. That starts with developing a deep understanding of how customers behave and make decisions. While hardcore data analysis will get you partway, interviewing sales reps is also crucial to uncovering what customers want. “You’ve got to listen to the guys who are taking calls 24/7 and dealing with a customer every two or three minutes,” says Gary Booker, CMO for Dixons Retail. “They really know what the customer wants.”

Marketers and sales people should together be spending a significant percentage of their time with customers to understand current and emerging needs. One well-known product company, for instance, bypassed its distributors and embedded some of its engineers in paint shops because customers had reported having trouble keeping the walls clean. While there, they discovered dust in paint bays was causing defects. So they created a new system for their distributors that reduced paint job defects by 49 percent.

For this sort of collaboration to succeed, the CMO and head of sales need to be deliberate and visible in working with each other. This needs to go further than simply sending out joint emails and joining each other’s meetings. The CMO and head of sales should map out skills and capabilities needed to reach their goals, identify the skills that currently exist and where they reside in the organization, and identify and plan to redress talent gaps. In addition, the two leaders need to identify disconnection points between the two groups and develop processes to bridge them.

When it comes to data, marketing insights teams have to adopt more of a customer service mentality, approaching sales reps on the front lines more like customers. From the sales side, teams need to be trained to take the insights generated by marketing and act on them. Teams from each function can also participate in joint assignments, and team members can be rotated through each other’s departments. Field marketing can also bring marketing closer to the sales force — and the customer. One European retail bank, for example, set up “opportunity labs” in its branches and agencies—i.e., at the point of delivery to the customer—where marketing could come together with sales to develop new customer programs.

3. Create a technology engine that powers the front lines. Investing in better and more useful technologies is critical for sales to move more quickly and effectively on the leads that marketing can uncover. That means investing in technologies to help turn ubiquitous mobile devices into sales tools and becoming more sophisticated about collecting data. In some industries (e.g. high tech), marketing can work with sales to define what data would be valuable then work with product development to create sensors that provide that data. Products can then provide feedback on when to get maintenance and when the product will have reached the end of its useful life.

But for all the potential technology provides, it’s important not to lose sight of what the point is. The fundamental truth about technological innovation is that it needs to help sales people make better decisions on the front lines. In the rush of excitement to build great tools, the resulting analysis is often either too complex for sales people to use or isn’t relevant to the immediate business opportunity. The challenge for the CMO is to reduce all the heavy backend analysis to a set of simple actions and guidelines that front-line sales people can use. And the challenge for the head of sales is to effectively articulate what insights are needed to make better decisions.

Caesars has taken that point of view to heart. When a guest has entered one of their hotels or casinos and interacted with it (through use of their loyalty card, or increasingly, based on beacons and similar technology throughout our properties), a host (the person responsible for helping and serving customers) will be alerted on their Blackberry or iPhone. That alert displays their historical behavior, what they have been interested in, what experience they had when they were last there, what food s/he likes, and where to find that person.

A cargo airline provides another example. Their marketing team developed a complex model that took all the frequently changing dynamics of the cargo industry, as well as opportunities for different negotiation strategies based on supply and demand, into account. But that wasn’t the real win. The company then took all that complexity and hid it behind a simple dashboard that it gave to the sales force. This dashboard provided simple guidelines on flight capacity, corresponding pricing, and competitor options. The result? A 20 percent boost in share of wallet.

The CMO and head of sales stand on the front lines of growth. They are best positioned to spot and understand emerging trends, build strong bonds with customers, and distill new opportunities into real action. But finding above-market growth will remain elusive until CMOs and heads of sales take the lead in developing a more cohesive approach to the marketplace.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers