Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1344

November 6, 2014

What Economists Know That Managers Don’t (and Vice Versa)

Why did Jean Tirole win the Nobel Prize in Economics? Not for the highly-regarded work on competition between small numbers of firms with which his career began more than thirty years ago but for more recent work on how carefully structured regulation can improve performance relative to unbridled market forces. This is a reminder that serious students of market performance take market failures seriously.

But what many economists generally gloss over is a notion that I will argue is highly complementary to market failures: management failures. For policy-making purposes economists assume that all businesses act rationally in the pursuit of profits. The possibility that that might not be the case is generally ignored, or even when mentioned, quickly finessed.

Even Tirole betrays this bias. The section on the profit maximization hypothesis at the end of the introductory chapter of his classic 1988 textbook on industrial organization concludes by saying that even if a firm doesn’t maximize profits, it can be treated, for the purposes of many of its interactions with the outside world, as if it does. Partly because profit maximization is a bedrock assumption and partly because maximization is a basic mathematical tool, economists have trouble dealing with firms that are not maximizing profits.

In this worldview, disasters only happen because the rules of the game in which the businesses operate must be flawed. Economists disagree about the actual incidence of these market failures and the cost-effectiveness of governmental efforts to tackle them, but they broadly agree that the only factors that prejudice performance are external to businesses.

Businesses and management experts, in contrast, tend take the opposite position. Thus, Dominic Barton, among many others, traces capitalism’s current problems to capitalists who work with time horizons that are shorter than they ought to be. And Michael Porter and Mark Kramer point to a big pot of gold for businesses that properly internalize the social consequences of their decisions instead of incorrectly externalizing them. In this view, poor performance is (mostly) caused by management failures — specifically, miscalculations of various sorts — rather than inherent flaws in the workings of the marketplace. And specific prescriptions for practitioners are served up that are supposed to improve both private profits and public welfare.

Neither school of thought, though, has it quite right. In their efforts to characterize important failures as being (for one group) always market failures and (for the other group) management failures, the two groups end up missing out on each other’s insights.

For an example, reconsider the financial crisis. Some, arguably including the Fed Chairman who presided over its eruption, Alan Greenspan, were utopians who thought nothing could go wrong on either front: the rules of the game or managerial responses to them. But the financial sector was clearly subject to a number of the market failures that were well known to most economists.

To begin with, quite a few parts of it are heavily concentrated at a global level (the credit ratings business, for example, or global investment banking), and many more at the national level (just six financial institutions account for 46% of all U.S. banking assets and as such are “too big to fail”). This small-numbers problem invalidates Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” mechanism in which good performance is supposed to be ensured by large numbers of competitors, none controlling more than a sliver of the market and none, therefore, with the power to jack up prices.

Other aspects of the financial sector highlight some of the problems with markets that economists have added to their list since the time of Adam Smith. Because of informational imperfections (think subprime mortgages), segments within financial services have a history of provoking manias, panics, and crashes — volatility exacerbated by recent innovations such as exotic derivatives and high frequency trading. Since capital is like air to other markets, problems with the financial sector can have important effects on the rest of the economy, a version of the market failure referred to under the rubric of externalities.

But having run through those economic problems with financial market attributes, the meltdown probably shouldn’t be chalked up just to them: missteps on the part of key managers also contributed. Consider Lehman Brothers, whose collapse was the trigger for broader sectorial travails. In the aftermath of Dick Fuld’s refusal to agree with the terms proposed by the government to help bail it out, his net worth was estimated to have collapsed from close to $1 billion to about $100 million. Similar points could be made about Jimmy Cayne at Bear Stearns and many others.

Nor was the government — beyond Greenspan and the Fed — blameless in the run-up to the crisis. The push to expand home ownership swelled the subprime mortgages that ended up sinking large chunks of the financial sector. Bailouts — not just the ones after the crisis but also prior ones, such as that of Long Term Capital in 1998 — aggravated the problem of “moral hazard” that informational imperfections can engender. And the complexity of some of the post-crisis regulations seems, in a world of human rather than superhuman managers, to have slowed down recovery from it.

Given such realities — which could also be illustrated with other key sectors such as health care and education — the right response is to pay attention to both market and management failures. Doing so expands one’s sense of both the room to improve performance and the levers that might be pulled to do so. It also helps enhance credibility — another important consideration since recent surveys suggest that Americans, at least, are similarly dissatisfied with their government and with large corporations.

Finally and most importantly, considering both management failures and market failures helps spotlight the most serious problems because of an interaction effect: market failures expand the scope for management failures to matter a lot. For instance, poor decisions by managers at a company will be of more concern if the company is one of a few or, even worse, a monopoly. Choices about how high to set investment hurdles are more likely to be an issue in highly volatile market conditions. And managers are likely to be more confused about what they should internalize and what they should ignore when there are some externalities.

But to see these complementarities you have to take both market failures and management failures seriously — and not enough people are doing that as yet.

This post is part of a series leading up to the 2014 Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 13-14 in Vienna, Austria. See the rest of the series here.

The One Thing About Your Spouse’s Personality That Really Affects Your Career

Here’s something that’s obvious, but at the same time not: We’re all a lot more than we appear to be at work.

We have other dimensions that are invisible to our companies, supervisors, direct reports, and most of our colleagues, and those invisible dimensions have a deep impact on our work.

A couple of pieces of research got me thinking about this. One is a diary study of dual-earner couples showing that people put more time in at work when their intimate relationships are going well, because the absence of drama at home gives them greater emotional, cognitive, and physical vigor to bring to the workplace.

The other shows that spouses’ personalities affect employees’ work outcomes — incomes, promotions, and so on. Both studies are reminders that each individual bent over each task in the office is connected to, and the product of, a social and familial context that matters a lot, and we should all be paying more attention to those contexts.

Which I’ll get to in a second. But first, let me just say that I’m not advocating for more emotional sharing at the office. I really like the peaceful mutual ignorance of private matters that’s the norm at my work. It’s blissful. It’s one of the things that make work great, honestly.

But I do believe we could all benefit from a bigger awareness of the impact — the weight — of our outside lives on our work performance, and by “we” I mean the organizational we, too: The Powers That Be.

Both of the studies I mentioned are thought-provoking, but the second is truly remarkable. Brittany C. Solomon and Joshua J. Jackson of Washington University in St. Louis realized that a rich trove of data on thousands of Australian households would lend itself to an analysis of the effect of spouses’ personality characteristics on people’s employment outcomes, because the database included not only survey results indicating personality dimensions but also information on incomes, promotions, and job satisfaction.

The personality data covered what are known as the “big five” dimensions — extroversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and openness. The researchers found that the only spousal trait that was important to an employee’s work outcomes was conscientiousness, which turns out to predict employee income, number of promotions, and job satisfaction, regardless of gender.

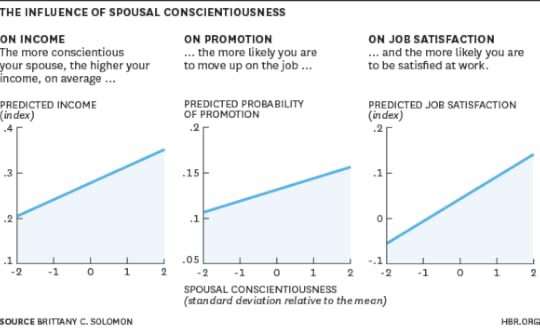

Here you can see the relationships between spousal conscientiousness and income, promotions, and job satisfaction:

To put the income finding in dollar terms, with every 1-standard-deviation increase in a spouse’s conscientiousness, an individual is likely to earn approximately $4,000 more per year, averaging across all ages and occupations, according to Solomon. And one way to frame the promotion finding is that employees with extremely conscientious spouses (two standard deviations above the mean) are 50% more likely to get promoted than those with extremely unconscientious spouses (two standard deviations below the mean).

Even more remarkable is that the data allowed the researchers to figure out why spousal conscientiousness matters.

First, conscientious spouses handle a lot of household tasks, freeing employees to concentrate on work (“When you can depend on someone, it takes pressure off of you,” Solomon told me). Second, conscientious spouses make employees feel more satisfied in their marriages (which ties in to the first study I mentioned). Third, employees tend to emulate their conscientious spouses’ diligent habits.

This doesn’t mean your success depends on your being in a relationship. There are plenty of single people who shine at work, and there are plenty of effective business leaders who are unattached. In fact, research suggests that in certain circumstances, being single can help CEOs run their companies: firms led by unmarried chiefs invest more aggressively and take greater risks than other firms.

But as Solomon says, successful people often turn out to have strong marital relationships. “When you’re in a relationship, you’re no longer just two individuals; you’re this entity,” she says. The more solid the entity, the greater your advantage.

It’s obvious, of course, that our one-dimensional work lives don’t fully represent our multidimensional outside lives, that each of us is just the visible manifestation in cubeland of a sprawling existence that not only extends far and wide in the moment but has a whole history behind it. Although we may look like a collection of dots on a floor plan, each of those dots is like the intersection in space of a long line and a two-dimensional surface. The surface (the workplace) doesn’t see the lines; it sees only the points of intersection, the dots.

But what isn’t obvious is the extent to which so many people are parts of teams, in a sense — two-person teams that are based outside the office. Any particular colleague or boss or direct report might be supported by a truly conscientious spouse, someone who willingly — even joyfully — takes care of details that would otherwise become headaches and interfere with work. For that matter, any particular colleague or boss or report might be hampered by a spousal relationship that’s a couple of standard deviations below the mean, as they say.

We can’t and probably don’t want to know the details about these teams, but as Solomon points out, if organizations really understood the workplace effects of strong outside relationships, they might be more receptive to policies like flextime and telecommuting that make it easier for employees to spend time with their significant others.

Maybe you don’t agree that your company should get involved in trying to improve your spousal relationship. But there are things you can do on your own. You can support your spouse in supporting you. If you depend on his or her reliability, diligence, and goal orientation, don’t take those traits for granted. Maybe you’ve been standing heroically at the bow for so long that you’ve forgotten how much effort it takes to row. So sit down and row for a while.

And while you’re rowing, how about suggesting that your spouse get up and stand heroically in the bow for a change? Emulate his or her conscientious: Really put your back into it. You may find that your conscientious spouse has a compelling vision of his or her own that will take you into unexpected places.

Research: How Female CEOs Actually Get to the Top

Ambitious young women hoping to run a major business someday are often advised to take a particular career path: get an undergraduate degree from the most prestigious college you can, an MBA from a selective business school, then land a job at a top consulting firm or investment bank. From there, move between companies as you hopscotch your way into bigger roles and more responsibility.

That’s what we were told as undergraduates, and later on as students at the Harvard Business School and the Harvard Kennedy School. It’s what Meg Whitman did, more or less, and it’s what Sally Blount, dean of the Kellogg School of Management and the only woman running a top-ten business school, recently recommended: “If we want our best and brightest young women to become great leaders…we have to convince more of them that … they should be going for the big jobs,” which for her meant “the most competitive business tracks, like investment banking and management consulting.”

We decided to put our expensively honed analytic skills to work testing that advice by looking at the career paths of the 24 women who head Fortune 500 companies. What we found surprised us.

Most women running Fortune 500 companies did not immediately hop on a “competitive business track.” Only three had a job at a consulting firm or bank right out of college. A larger share of the female CEOs—over 20%—took jobs right out of school at the companies they now run. These weren’t glamorous jobs. Mary Barra, now the CEO of General Motors, started out with the company as college co-op student. Kathleen Mazzearella started out as a customer service representative at Greybar, the company she would eventually become the CEO of more than 30 years later. All told, over 70 percent of the 24 CEOs spent more than ten years at the company they now run, becoming long-term insiders before becoming CEO. This includes Heather Bresch at Mylan, Gracia Martore at Gannett, and Debra Reed at Sempra Energy.

Even those who weren’t promoted as long-term insiders often worked their way up a particular corporate ladder, advancing over decades at a single company and later making a lateral move into the CEO role at another company. This was the experience of Patricia Woertz, CEO of Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), who built her career over 29 years at Chevron. And it was the experience of Sheri McCoy, who became CEO of Avon after being passed over for the CEO role at Johnson & Johnson, where she worked for 30 years.

The consistent theme in the data is that steady focus wins the day. The median long stint for these women CEOs is 23 years spent at a single company in one stretch before becoming the CEO. To understand whether this was the norm, we pulled a random sample of their male Fortune 500 CEO counterparts. For the men in the sample, the median long stint is 15 years. This means that for women, the long climb is over 50% longer than for their male peers. Moreover, 71% of the female CEOs were promoted as long-term insiders versus only 48% of the male CEOs. This doesn’t leave a lot of time for hopscotch early in women’s careers.

It is hard to parse what drives the long-tenure, insider path that so many of these women took or why their experiences differ from those of the men. Optimistic interpretations could include supportive organizations, strong mentors, or something intrinsic to the women themselves. On the flip side, differences between the long stints for women and men could also result from structures that treat women less favorably, from biases that delay promotions to penalties for taking maternity leave. Regardless of the root cause, it seems important to acknowledge that the long climb is the common path for female Fortune 500 CEOs.

An immediate implication of the long climb is that for ambitious young women, company culture matters a lot. If a common pattern is to spend multiple decades advancing in a single environment, that environment had better fuel female ambition rather than stifle it. A recent Bain survey shows that while women in entry-level jobs have ambition and confidence to reach top management in large companies that matches or exceeds that of men, at mid-career, men’s ambitions and confidence stay the same, while those of women drop dramatically. A company capable of maintaining the drive of its women as they progress in their careers is a better bet for a long stint than one that allows the more common diminishing trend to occur.

Let’s go back to that conventional career advice. What about the prestigious college? Does that matter? While Whitman’s high-prestige background may seem like it should be the norm, she is one of only two woman running a Fortune 500 company to have an undergraduate degree from an Ivy League institution. (This doesn’t appear to be a gendered issue. Only four percent of the men in our sample attended an Ivy League school.)

Early stints in consulting and banking also hardly seem to be a prerequisite for either gender: about three-quarters of the men and women do not have any reference in their publically available resumes to time spent in either industry, liberally defined, at any time. Prestigious MBA programs are also hardly a requirement; only 25% of the women and 16% of the men hold an MBA from a top-ten school. In short, for both male and female Fortune 500 CEOs, collecting a single conventional badge of prestige, let alone collecting a handful of them, may help, but is hardly a gating factor.

Of course, the world may have changed since the current CEOs made the choices that led them to the top seats in corporate America. The average age of the 24 female Fortune 500 CEOs is 56, leaving room for the tide to have shifted. Yet the youngest woman in the group, Heather Bresch of Mylan, 45, still follows the insider trajectory perfectly. Starting out typing drug labels at a Mylan plant in Morgantown, West Virginia, Bresch moved to roles of increasing responsibility over the next 20 years before becoming CEO.

It may be that the playbook for advising young women with their sights set on leading large companies needs to be revised. Just as important, there is something inspiring for young women in the stories of these female CEOs: the notion that regardless of background, you can commit to a company, work hard, prove yourself in multiple roles, and ultimately ascend to top leadership. These female CEOs didn’t have to go to the best schools or get the most prestigious jobs. But they did have to find a good place to climb.

November 5, 2014

Why IBM Gives Top Employees a Month to Do Service Abroad

“Eight out of 10 participants in the Corporate Service Corps program say it significantly increases the likelihood of them completing their career at IBM,” Stanley Litow, VP of Corporate Citizenship & Corporate Affairs, told us.

Recognizing that corporate responsibility can offer a company a competitive advantage today, we became interested in IBM as a pioneer in establishing a skills-based volunteerism initiative that also influences its talent and professional development strategies. Several executives at the company offered to talk with us to figure out why the program has been so successful—not just as a philanthropic gesture, but as a talent development system. As Litow put it, “If participation in these programs increases our retention rate, recruits top talent, and builds skills in our workforce, then it’s addressing the critical issue of competitiveness.”

The IBM Corporate Service Corps, a hybrid of professional development and service, deploys 500 young leaders a year on team assignments in more than 30 countries in the developing world. Employees engage in two months of training while working full time, spend one month on the ground on a 6- to 12-member team tackling a social issue, and then mentor the next group for two months. So far, IBMers have completed over 1,000 projects.

The IBM Corporate Service Corps is an example of how IBM is incorporating service into leadership development as a result of the success of another IBM program, IBM’s On Demand Community, which was launched in 2003 as an online marketplace to connect nonprofits with employees and retirees, as well as a portal offering resources to nonprofits of all kinds. According to Litow, the objective was threefold: to support IBMers in their service engagements, to invest the intellectual capital of IBMers in tackling social issues around the world, and to develop the expertise and leadership of IBMers through volunteer opportunities that leverage their skills and abilities.

Argentinian software developer German Attanasio Ruiz, now part of IBM Watson Research, took advantage of On Demand Community and worked with a team of volunteers to produce a mobile application that helps children with special needs recognize emotions in everyday situations. It has now been translated into five languages. Ruiz volunteered significant hours over a six-month period and added mobile app development to his skill portfolio in the process. The volunteer team has since produced a second app, El Recetario, for more advanced students. They received the Volunteer Excellence Award in 2013 and developed a volunteer tool for On Demand Community called “Mobile Applications for Kids with Special Needs.”

Since the inception of On Demand Community, nearly 260,000 former and current employees from 120 countries have collectively logged more than 17 million hours of service. There’s a clear impact on employee engagement: “When I work for IBM,” says Ruiz, “my hands are bigger in terms of what I can do.”

Diane Statkus, an IBM project manager in Boston, echoes Ruiz’s sentiments. She’s volunteered at Girls Inc., the New England Center for Homeless Veterans, and has used her project management expertise to lead a job-skills assistance event with a team of volunteers each year. She’s startlingly honest in her assessment of how these experiences have affected her: “If I didn’t have the ability to be involved in this volunteer work, I’m not sure I’d still be there.”

So what makes the IBM programs so compelling? We noticed three key differentiators:

A multitude of options, so that everyone can find (or design) something they’re interested in. At the core of the Corporate Service Corps and On Demand Community are projects created by employees, retirees, and not-for-profit organizations. The thousands of IBMers who are engaged in service on a regular basis can select the projects they want to work on from the multitude available.

The On Demand Community portal is more than a marketplace; it’s a library. Volunteers can tap into ready-made presentations, videos, reference links, and software tools. (To expand its breadth of support for volunteerism, IBM made these free resources available to the public in 2011.) This library of tools helps employees get their projects off the ground, and ensures the quality of services that the organizations will receive.

Opportunities are actively pushed to interested employees, and can be used to satisfy professional requirements. Project listings are periodically emailed to employees who’ve filled out profiles with their locations, interests, and skills. Employees also can fulfill their professional development requirements through community service projects.

As a result, not only do IBM employees get to give back while developing their skills, but local communities get a great impression of IBM. One of the organizations that has benefited from IBM’s program is the Girls Scouts of Eastern Oklahoma (GSEOK). Among other efforts, IBMers have volunteered to teach classes and help develop an age-appropriate STEM curriculum. Says CEO Roberta Preston, “The real benefit for us as a not-for-profit is that we have world-class expertise at our fingertips that would otherwise be beyond our reach.”

When employees acquire new skills through volunteering, and enhance the company’s brand by giving back to their communities, there’s a clear benefit to Big Blue’s bottom line. “This is a very important attraction and retention vehicle for our company,” says Diane Melley, VP of IBM Global Citizenship Initiatives. “This brings value to our employees in terms of supporting them as well as acquiring the skills that they need to be successful as IBMers.”

3 Traps That Block Corporate Transformation

The need for transformation has never before been more keenly felt in the corporate world. Digital-first companies, such as Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Twitter, are amassing market share and capitalization, but only a few brick-and-mortar corporations (think Apple, Nissan, and HCL Technologies) have been able to change fast enough to catch up with their rivals. Why do companies that lose their relevance find it so tough to recover?

For decades, the success of a business depended on three key pillars: Innovative Ideas + Cheaper/Faster/Better Execution + Powerful Leadership. Ideas were critical, but execution was the source of competitive advantage even during the internet era for companies such as Toyota, GE, and Dell. They made mediocre ideas look great because of their execution, and a tightfisted, centralized, command-and-control culture dominated such organizations.

But, with the digital era’s dawn, traditional sources of competitive advantage are fading — for three reasons.

One, digital technologies have shortened and simplified execution cycles, and compressed advantages built on physical reach. Two, with the emergence of specialized organizations that can handle manufacturing and logistics, customer support and after-sales services, and IT, entry barriers in many industries have fallen. And three, the new technologies have made possible more consumer analytics, greater visibility, and scale, forcing a move away from standardization and towards personalized offerings and unique experiences.

As a result, the winning formula has become: Innovative Ideas + Delivering Unique Experiences + Enabling Leadership. Uber’s rise, for instance, has been propelled by the novel concept of using mobile devices to hail cabs, and a cool customer experience that features seamless credit card payments and driver ratings. Its managers are committed to transparency and allow employees to constantly scout for new business opportunities. No wonder Uber, which was founded five years ago, is valued at around $17 billion today.

But what if you’re in an existing business rather than a start-up? Going by my experience at HCL Technologies, where I led the change effort, transformation for large companies involves breaking out of three traps:

The Logic Trap. Companies often have to consider doing what others believe is impossible; they can’t change radically by thinking within the boundaries of reason. Could Amazon have come up with the idea of delivery drones, for instance, by thinking within the box?

Smart companies identify gaps, focus on discontinuities, and force the creation of new markets. Their leaders have to move away from incremental steps, such as cost cutting, and think of giant leaps that will put them on the path of transformation. That’s what we did at HCL Technologies with the Employees First, Customers Second idea. Being illogical can sometimes be a way of achieving the impossible.

The Continuity Trap. A comet leaves behind a tail long after it has disappeared, but astronomers, knowing that the comet has gone, quickly re-calibrate their telescopes to search for the next one. By contrast, many business leaders take comfort in the past — essentially staring at the long-gone comet’s tail — rather than getting excited about the uncertainty of the future.

Some argue that uncertainty demotivates employees, leading to increased attrition and corrosion of market value. However, the opposite is also true; the best talent is usually motivated by challenges and how to tackle them. An owner may wax eloquent about his beautiful home, but it’s the leak in the bath that excites the plumber.

HCL Technologies was proud of its leaky pipes, so to say, and laid bare those aspects of the organization that weren’t working. That attracted transformers, who were drawn up by the challenge of fixing big problems. HCL’s clock speed went up, and its talent and energy focused on tackling future discontinuities. As a result, the company has seen revenues and market capitalization grow over seven-fold in the last nine years.

The Leadership Trap. If the source of today’s competitive advantage lies in the interface between employees and customers, the leader’s role must change from being a commander to an enabler of bottom-up innovation. Customer experience is supreme, so leaders must inspire employees to create and deliver unique experiences by tapping into their insights.

Howard Schultz and Jeff Bezos, the CEOs of Starbucks and Amazon, are proponents of the employee empowerment credo. Their goal is to inspire employees to be personally accountable for the customer experience. That’s how more leaders should try to think.

The impact of digital technologies on business and leadership models is the biggest issue facing corporations nowadays. It’s an opportunity for business leaders to stand up, be counted, and convert the threat into an opportunity for transformation without settling for incremental change. Isn’t it stimulating to do what no one has done before you?

This post is part of a series leading up to the 2014 Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 13-14 in Vienna, Austria. See the rest of the series here.

Get Your Organization to Run in Sync

Hundreds of consumers standing in line at your local Apple store. Thousands of protesters rushing to flood the streets of Kiev, Istanbul, or Hong Kong. Millions of fireflies blinking on and off in complete unison. Even the unconscious beating of your heart. These are all synchronized systems.

So it is curious that the institutions we build—and put so much conscious effort towards—are so rarely able to synchronize. Despite our best efforts, most organizations operate disjointedly. Fortunately, research into network science has begun to shed light on how synchronization happens and how we can make our enterprises function more effectively. Three elements are key.

1. Small groups. Most leaders tend to think on a macro level. That shouldn’t be surprising, because our efforts tend to be focused on our responsibilities. So if we’re responsible for an entire organization, then we tend to think in those terms and act accordingly.

However, actions are influenced at the grassroots. As Solomon Asch showed in his famous conformity experiments, we tend to adopt our views our peer group. In fact, his research showed that we conform to those around us even when their views are demonstrably untrue.

Asch’s research helps explain why it is so hard for enterprises to adapt to new challenges. It may be possible to create alignment among the leadership team, but that consensus will break down once the individual members return to their working groups. There, they will find that they are confronted with local majorities opposed to the global leadership view and, in time, even leaders will conform.

That’s what appears to have happened at Blockbuster. Faced with a competitive challenge from Netflix, CEO John Antioco came up with what seems, even in retrospect, to be a viable plan. Nevertheless, various groups within the enterprise balked at the plan, Antioco was fired, and Blockbuster went bankrupt.

So leaders need to treat new initiatives not as mere organizational governance, but as a grassroots movement of small, interconnected groups, each with varying thresholds of resistance—some enthusiastic, others hostile and many in between. Moving an idea forward is not just a matter of persuasion, but also of managing the connections between constituencies.

2. Loose connections. Those close to us tend to have the same limited knowledge we do. They have similar experiences, are confronted with similar challenges and share many of the same personal relationships. So while our views tend to correspond to our peer group’s, the information most valuable to us usually lies outside of it.

That’s exactly what sociologist Mark Granovetter found he began studying how people landed jobs in communities around Boston. It wasn’t through close friends that people found employment, but more distant acquaintances—friends of friends. He called the phenomenon the strength of weak ties.

It is the combination of tight circles and loose connections that drives high performing organizations. A study of star engineers at Bell Labs found that the most accomplished ones worked in a close-knit group, but also frequently reached out to people outside of it.

Another study of Broadway plays found the same thing. If no one in the cast and crew had worked together before, then results were poor. However, if there were too many existing relationships, then performance suffered as well. You need the right mix of cohesion and diversity in order to achieve both innovation and operational efficiency.

And that’s what makes synchronized organizations top performers—they are not only aligned internally but also able to adapt to new information that arises externally.

3. Shared context. In nature, the purpose of a system is hardwired. Nobody has to tell a pacemaker cell in the heart what it is supposed to do. However, in organizations it is incumbent on leaders to set direction.

Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad called this concept strategic intent. Southwest Airlines has prospered by being “the fun low cost airline” and seeks to be nothing else. Google strives to “organize the world’s information.” Apple creates products that are “insanely great.” It is the mission that drives the strategy, because that’s what defines what winning looks like.

Yet a clear mission, although important, is not enough. There also must be a shared context of values and beliefs. Apple, for example, has committed to specific design values and an integrated architecture. Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has described his company’s values at length in a new book called How Google Works, which emphasizes how Google seeks out “smart creatives” and strives to build a working environment where their ideas can thrive at scale.

Firms with strong value systems seamlessly adapt to new challenges. Apple and Google, of course, have been successful across a variety of market contexts. Less familiar examples include the thriving business of McDonalds in India, where it must cater to vegetarian diets, and Cosmopolitan magazine’s success in Islamic countries where public discussions about sex are taboo.

So how do you get your organization more in sync? Most leaders focus on strategies and plans because that is what stakeholders are asking for. It is easier to formulate a story based on market analysis than it is to promote better organizational health. Nevertheless, studies have shown that it’s the informal networks within an organization that are crucial to success.

We can no longer rely on hierarchies. The problem is not that they have suddenly become illegitimate, but that they are slow and the world has become fast. It is no longer enough to merely plan and direct action, today we must inspire and empower movements of belief.

So in addition to their role in formulating strategy and optimizing financial performance, managers must also seek to create synchronized organizations to carry out strategic intent. That requires a focus on small groups, loosely connected — but united by a shared context.

How to Handle Stress in the Moment

You hear a lot of advice about how to reduce stress at work. But most of it is about what to do over the long term — take up yoga, eat a healthy diet, keep a journal, or get more sleep. But what do you do when you’re overcome with stress in the moment — at your desk, say, or in a meeting? Perhaps you’ve heard bad news from a client or were assigned yet another project. How can you regain control?

What the Experts Say

Eighty percent of Americans are stressed at work, according to a recent study by Nielsen for Everest College. Low pay, unreasonable workloads, and hectic commutes were the top sources of tension, followed closely by obnoxious coworkers. What exacerbates the problem is that “people walk into work already laden with stress,” says Maria Gonzales, the founder and president of Argonauta Strategic Alliances Consulting and the author of Mindful Leadership. “If there is a hardship at home, you bring that to the office and it gets layered with your professional stress and — if you’re not careful — it can spiral out of control.” How well you react to and manage daily stressors “impacts your relationships with other people, with yourself, and how others perceive you,” she says. Justin Menkes, a consultant at Spencer Stuart and the author of Better Under Pressure says it’s critical “to get a handle on your reaction to the stressful things that happen to you in the moment.” Here are some techniques to do just that.

Identify your stress signals

Train yourself to recognize “your physiological signs of stress,” says Gonzales. Perhaps your neck stiffens, your stomach clenches, or your palms sweat. These are all the result of what’s happening inside your body. “The minute you start to experience stress, your pulse races, your heart beats faster and hormones [including cortisol and adrenaline] are released,” she says. “This compromises your immune system and your ability to experience relaxation.” When you’re able to recognize the signs — instead of ignoring them — you’ll be able to start addressing the underlying cause of the stress.

Don’t think of it as stress

“Most often the reason your blood pressure rises at work is because you’re being asked to do something important” by your boss or a colleague and you want to succeed, says Menkes. “The stress symptoms are telling you: This matters.” Shift your thinking about the task causing you distress and instead try to view it as “an opportunity to move forward that you want to take seriously,” he adds. The goal is to “use that adrenaline pop” to focus your nervous energy, “heighten your attention, and really apply yourself.”

Talk yourself down

When you’re stressed, the voice inside your head gets loud, screechy, and persistent. It tells you: “I’m so angry,” or “I’ll never be able to do this.” To keep this negative voice at bay, “try talking to yourself in a logical, calm tone and injecting some positivity” into your internal dialogue, says Gonzales. “Say something like, ‘I have had an assignment like this in the past and I succeeded. I can handle this, too.’ Or, if you are faced with an unrealistic request, tell yourself: ‘I am going to calm down before I go back and tell my manager that completing this assignment in this amount of time is not possible.’”

Take three deep breaths

Deep breathing is another simple strategy for alleviating in-the-moment tension. “When you feel anxious, your breath starts to get shorter, shallower, and more irregular,” says Gonzales. “Taking three big breaths while being conscious of your belly expanding and contracting ignites your parasympathetic nervous system, which induces a relaxation response.” You can do this while also lowering your shoulders, rotating your neck, or gently rolling your shoulders. Deep breathing also helps preempt stress symptoms if you need to, say, get on a tense conference call or deliver bad news in a performance review. “When your mind becomes crowded with negative thoughts, let deep breathing occupy your mental real estate,” says Gonzales.

Enlist a friendly ear

You shouldn’t have to face nerve-wracking moments at the office alone. “Everyone needs to have somebody they trust who they can call on when they’re feeling under pressure,” says Menkes. “Select this person carefully: You want it to be somebody with whom you have a mutual connection and who, when you share your vulnerabilities, will respond in a thoughtful manner.” Sometimes venting your frustrations aloud allows you to regroup; at other times, it’s helpful to hear a new perspective. This kind of relationship takes time to build and requires nurturing, and it’s likely you will be asked to return the favor. “When you do, it’s incredibly gratifying to be on the other end.”

Make a list

Creating a to-do list that prioritizes your most important tasks is another way to combat feeling overwhelmed. “The act of writing focuses the mind,” says Gonzales. “Do a brain dump and write out everything you need to do and note whether it’s professional or personal, so you make time for both,” she says. Next to each item, indicate when the task needs to be completed. And here is a critical step: “Identify which are ‘important’ and which of those items are ‘urgent.’” Those are the ones to tackle first.” Once those are finished, move on to the other things that are more routine. “If you spend all your time on the time-consuming mundane things, you may never get to the important things which is how we get ahead,” she says.

Project an aura of calm

Ever notice how when you’re speaking to someone who’s agitated, you start to feel agitated too? That is because stress is contagious. “When someone palpably feels your tension, they react to it,” says Menkes. He suggests “trying to modulate your emotions” when you find yourself in a tense conversation. Force yourself to “keep your speaking voice gentle and controlled,” adds Gonzales. Talk in a reasonable and matter-of-fact manner. “If you are persistently calm, others will be too,” she says.

Do

Identify what your physiological signs of stress are so you can work to alleviate the tension

Counteract stressful situations by taking deep breaths

Find someone whose judgment you trust who can listen and provide counsel

Don’t

Forget the reason you feel stressed in the first place — you are being asked to do something important and you want to succeed

Let the negative voice in your head spiral out of control — talk to yourself in a logical, gentle tone

Project your stress onto others — speak in a calm, controlled way and others will too

Case study #1: Think positive thoughts

Cha Cha Wang was seven months into her job as a business analyst at an online services company when her manager came to her one afternoon and asked for assistance. He needed her to turn around a comprehensive financial forecast for the company. And she had a week to finish it.

“My heart started racing,” recalls Cha Cha. “Our company was newly public and I wanted to do as good a job as possible. I felt like I had two voices inside my head. One was saying: ‘That is impossible. There’s not enough time to do it,’ and the other was saying: ‘You have no choice; it has to get done.’”

Cha Cha excused herself to the bathroom, looked in the mirror, and took a deep breath. She reflected on her days as an MBA student and her stint as a consultant. “In business school and in consulting, you’re inundated with a lot of different assignments and you have to juggle multiple deadlines,” she says. “I told myself: ‘I can do this. My personal life will go on hold for a week and I will not get much sleep, but it will get done.’”

Having calmed her initial stress reaction, Cha Cha then focused on the “tactical execution” of the project. She made a detailed list of all the financial data she needed; she then scheduled meetings with colleagues who had that information. After each session, she incorporated new figures into her statistical models. She worked late every night that week, but she finished the financial forecast by the deadline.

“When I was younger, I reacted more emotionally [to stress],” she says. “But now that I am a little more seasoned, and I’ve worked in several different jobs and tested my limits, I know what I can do.”

Case study #2: Vent to someone who will help you recover and move on

Pablo Esteves, the director of strategic partnerships for Emzingo — a company that runs leadership immersion programs for business schools — had been working on a proposal for a potential client for months. He had visited the prospective client on site and the two had gone back and forth over the proposal numerous times before he submitted it. Pablo expected to hear good news.

But instead, he received an email from the school’s administrator that said: “We see the value in what you’re doing and we like what you’re doing, but it’s not for us.” Pablo immediately felt stressed out. His pulse started racing and he knew that he needed to talk to someone to calm down. “I knew exactly who I could vent to,” he says.

Pablo, who is based in Madrid, sent an email to his colleague and friend, Daniel, who lives in Peru. He explained what had happened. Within an hour, the two men were on the phone. Daniel patiently listened to his problems, agreed with Pablo on certain points, and then offered his own perspective and advice. “He helped me understand why things maybe didn’t work out this time, but he also told me that we had other clients who were going to come through,” says Pablo. “He helped me regroup.”

The pep talk helped. After the call Pablo felt less stressed about the rejection and energized about focusing on new projects.

More on reducing stress:

Nine Ways Successful People Defeat Stress

The Best Way to Defuse Your Stress

Reduce Your Stress in Two Minutes a Day

Using Algorithms to Predict the Next Outbreak

There’s no doubt that our world faces complex challenges, from a warming climate to violent uprisings to political instability to outbreaks of disease. The number of these crises currently unfolding – in combination with persistent economic uncertainty – has led many leaders to lament the rise of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. Resilience and adaptability, it seems, are our only recourse.

But what if such destabilizing events could be predicted ahead of time? What actions could leaders take if early warning signs are easier to spot? Just this decade, we have finally reached the critical amount of data and computer power needed to create such tools.

“What is history? An echo of the past in the future,” wrote Victor Hugo in The Man Who Laughs. Although future events have unique circumstances, they typically follow familiar past patterns. Advances in computing, data storage, and data science algorithms allow those patterns to be seen.

A system whose development I’ve led over the past seven years harvests large-scale digital histories, encyclopedias, social and real-time media, and human web behavior to calculate real-time estimations of likelihoods of future events. Essentially, our system combines 150 years of New York Times articles, the entirety of Wikipedia, and millions of web searches and web pages to model the probability of potential outcomes against the context of specific conditions. The algorithm generalizes sequences of historical events extracted from these massive datasets, automatically trying all possible cause-effect combinations and finding statistical correlations.

For instance, recently my fellow data scientists and I developed algorithms that accurately predicted the first cholera outbreak in 130 years. The pattern that our system inferred was that cholera outbreaks in land-locked areas are more likely to occur following storms, especially when preceded by a long drought up to two years before. The pattern only occurs in countries with low GDP that have low concentration of water in the area. This is extremely surprising, as cholera is a water-born disease and one would expect it to happen in areas with a high water concentration. (One possible explanation might lie in how cholera infections are treated: if prompt dehydration treatment is supplied, cholera mortality rates drop from 50% to less that 1%. Therefore, it might be that in areas with enough clean water the epidemic did not break out.)

The implication of such predictions, automatically inferred by an-ever-updating statistical system, is that medical teams can be alerted as far as two years in advance that there’s a risk of a cholera epidemic in a specific location, and can send in clean water and save lives.

Other epidemics can be predicted in a similar way. Ebola is still rare enough that statistical patterns are tough to infer. Nevertheless, using human casualty knowledge mined from medical publications, in conjunction with recurring events, a prominent pattern for Ebola outbreaks does emerge.

Several publications have reported a connection between both the current and the previous Ebola outbreaks and fruit bats. But what causes the fruit bats to come into contact with humans?

The first Ebola outbreaks occurred in 1976 in Zaire and Sudan. A year before that, a volcano erupted in the area, leading many to look for gold and diamonds. Those actions caused deforestation. Our algorithm inferred, from encyclopedias and other databases, that deforestation causes animal migration – including the migration of fruit bats.

We have used the same approach to model the likelihood of outbreaks of violence. Our system predicted riots in Syria and Sudan, and their locations, by noticing that riots are more likely in non-democratic regions with growing GDPs yet low per-person income, when a previously subsidized product’s price is lifted, causing student riots and clashes with police.

The algorithm also predicted genocide by identifying that those events happen with higher probability if leaders or prominent people in the country dehumanize the minority, specifically when they refer to minority members as pests. One such example is the genocide in Rwanda. Years before 4,000 Tutsis were murdered in Kivumu, Hutu leaders such as Kivumu mayor Gregoire Ndahimana referred to the minority Tutsis as inyenzi (cockroaches). From this and other historical data, our algorithm inferred that genocide probability almost quadruples if: a) a person or a group describes a minority group (as defined by census and UN data) as either a non-mammal or as a disease-spreading animal, such as mice, and b) the speaker does so 3-5 years before they’ve been are reported in the news a minimum of few dozen times and have a local language Wikipedia entry about them.

After an empirical analysis of thousands of events happening in the last century, we’ve observed that our system identifies 30%-60% of upcoming events with 70%-90% accuracy. That’s no crystal ball. But it’s far, far better than what humans have had before.

What would it mean to NGOs, construction companies, and health organizations to know that droughts followed by storms can lead to cholera? What would it mean to mining companies, regulators, environmental organizations, and government leaders to know that mining leads to deforestation, and that deforestation leads to fruit bat migrations, and that fruit bat migrations may increase the risk of an Ebola outbreak? And what would we all do with the information that certain linguistic choices and policy changes can result in widespread violence? How might we all start thinking about risk differently?

Yes, “big data” and sophisticated analytics do allow companies to improve their profit margins considerably. But combining the knowledge obtained from mining millions of news articles, thousands of encyclopedia articles, and countless websites to provide a coherent, cause-and-effect analysis has much more potential than just increasing sales. It can allow us to automatically anticipate heretofore unpredictable crises, think more strategically about risk, and arm humanity with insight about the future based on lessons from the relevant past. It means we can do something about the volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity surrounding us. And it means that the next time there’s a riot or an outbreak, leaders won’t be blindsided.

Our Emotional Attachment to Local Currencies

The Brixton Pound was first issued as paper money in September 2009. Two years later, the electronic B£ pay-by-text platform was announced. Launched with the partnership of the Bristol Credit Union, the Brixton Pound is now used by 650 businesses, with £528,000 of the currency in use in both electronic and paper format.

The Brixton Pound is a medium of exchange, but it is not technically a legal tender since it does not constitute a government-backed promise to pay the bearer. However, Council Staff from the city can take part of their salary, on a voluntary basis, in electronic Brixton Pounds and all trade performed with the currency attracts corporation tax and VAT.

The Brixton pound is a good example of a new phenomenon that I call tribal money. Tribal money is a currency that is created not by a national institution or authority, but by a group of people with common cause. Supporters of the Brixton Pound use the slogan, “Creates Community Pride.” Other areas in the UK and beyond are also experimenting with new currencies. There are 70 complementary currencies in Spain alone, for example, and more than 5,000 worldwide.

Why is “tribal money” on the rise at the same time that barriers to trade and globalization are falling? Classical economics argues that money performs three functions: to give value to tradable goods; as a means of payment; and as a reserve of value. However there is an important and often overlooked, fourth function: to provide a sense of belonging. Money provides a sense of identity. It is no coincidence that coins and notes bear the images of monarchs, presidents, and national heroes.

The Brixton Pound performs the first two functions well: it gives a value to tradable goods; and it can be used as a means of payment. It is probably not so good at the third function, as a value reserve — complementary currencies tend to lose value over time. But most of all, what the Brixton Pound provides is a sense of belonging. It is about being part of a tribe.

During the nineteenth century, newly created nation-states looked for unifying elements to bond a society together. This took different forms: a national constitution a national language; national banks; and a national currency, including national symbols in the newly issued banknotes. For instance, the creation of the Spanish peseta in 1868 went in parallel to the establishment of the Banco de España in 1856, and its monopoly in 1874 of issuing currency, eliminating all other currencies in use at the time (escudos, reales, and maravedies). After the establishment of the peseta, bank notes, coins, and stamps were created having all the symbols of the Spanish nation: kings, queens and other political and cultural icons.

But today, pesetas, francs, deutschmarks, lira, and drachmas – all of which had a special place in the national psyches of their origin countries – have been replaced by the euro. (Tellingly, the UK, an island state, still retains the pound.) Nation-states, at least in Europe, don’t mean what they once did.

As identification with the old nation states loses strength, tribal affiliations are becoming stronger. Think of Scotland in the UK; Catalonia in Spain; or South Tyrol and Sardinia in Italy. Tribes are no longer defined by national borders but by communities of interest. As the symbols of national pride decline, the tribe becomes the carrier of identity – and wants to adopt its own currency. Viewed through that lens, it makes perfect sense that community-based complementary currencies are emerging now.

There is still no great emotional identification with the European Institutions. They are too big, too abstract, and too far away to elicit our emotional attachment. But humans have a fundamental need to belong to a community in which we can contribute and participate. Independent currencies provide a sense of continuity and belonging that European citizens feel in these transitional times.

The emotional attachment to money as part of a community culture – literally and emotionally a tribal currencies often underestimated. But it constitutes a relevant and important aspect to the future of Europe – and the rest of the world.

Engaging Your Older Workers

Older workers — those who are at or approaching the traditional retirement age of 65 — are the fastest-growing segment of the workforce and one of the fastest-growing groups in the overall population. In the U.S. the number of individuals aged 65 or older will increase by about 66% between now and 2035. The growth is driven in part by the Baby Boomer generation, but even more so by an increased life expectancy that’s creating more healthy years for more people.

As we learned in our research for our book, Managing the Older Worker, people who are 65 today have about the same risk of mortality or serious illness as those who were in their mid-50’s a generation ago. The percentage of the population over age 65 who are at serious risk of mortality or life-threatening illness will grow by only about 16% between now and 2035, which means that there will be a huge cohort of healthy individuals in that age group who want and need to work. These changing demographics will transform the U.S. labor market and society as a whole. Any employer who wants to engage a skilled, motivated, and disciplined workforce cannot afford to ignore them.

And yet, these workers are being ignored to some extent. About three quarters of individuals approaching retirement have for some time said that they would like to keep working in some capacity, yet only about a quarter of them actually do. Something is keeping them from working, and that something is on the employer side.

Engaging the older workforce should not be such a big challenge. Older workers tend to be in the workforce because they want to be — relatively few look for jobs because they need them to survive. (During the Great Recession we heard a lot about people not being able to retire because of finances, but we’re hearing that less now.) Older workers want to keep working first and foremost because it keeps them engaged with other people, and also to feel as though they’re contributing. Money is further down the list. Older workers also know what they are getting into and what is required when they accept a job — much more so than younger workers.

So, why aren’t we seeing more older employees in the workforce? The problem seems to be getting them in the door in the first place. Discrimination is certainly one reason. Evidence suggests that we are more biased in our views of older individuals than we are of minorities and women. It’s easy to see that bias if we compare the images that come to mind when we contrast the words “older,” which brings up negative stereotypes, and “experienced,” which brings up positive ones.

The other challenge is fear. Younger supervisors are often afraid of managing older employees because these older workers have more experience than they do. The less experienced managers may wonder, “How can I say, ‘Do this because I know best’ when often I don’t know best?” Older workers may also have some initial trouble being managed by younger supervisors, especially those with less practical experience than they have. But it’s up to supervisors to shape the relationship beginning with the first interaction by saying how they want to use the older worker’s experience, while pointing out what their own responsibilities are for setting goals and holding people accountable.

It’s not just a confidence issue. Younger supervisors may find that what works with most of their staff doesn’t work for older employees. They aren’t as fearful of being fired (they’re already at retirement age) and they have less interest in promotions or a big payout in the future.

So how do you keep an older worker engaged? Start by acknowledging and using their experience. Certainly this is true for any age group: Everyone wants their expertise to be recognized, especially by the boss. But with older workers, it’s even more important, because they typically have a lot of experience — so ignoring it is especially irritating. And older workers themselves can be prickly about being managed by someone who knows less than they do.

The military has developed some good tactics for recognizing and appreciating older workers’ expertise based on the efforts of generations of junior officers fresh out of college and struggling to manage older, more experienced sergeants. Military leaders now advise those officers to treat their experienced subordinates as partners, at least behind the scenes. The supervisor is still in charge, but he’s missing an opportunity (and is more likely to make a mistake) if he doesn’t check in with his more experienced subordinates — at least to hear their thoughts — before making important decisions. The supervisor still sets the goals and holds people accountable for meeting them. But the subordinates have a big say in the execution, and when they walk out of their private meetings with their managers, they need to be on the same page.

In the workplace, it’s useful to check in with individual older workers to ask them what problems they could foresee in executing a specific task (“Here’s what we need done”). If you don’t take any advice they offer, it’s helpful to explain why not (“I know it’s an aggressive deadline, but it’s important to finish this before the new manager takes over”).

In terms of their interests, older workers tend to be more like young workers than like their middle-aged peers. Their big financial needs are typically behind them, work is often a source of social interaction for them, and they care more about the good works that their employer might be doing than the cohorts in middle age. Supervisors should consider giving older works jobs with more customer interaction (frontline jobs) or those dealing with internal customers.

Research also suggests that putting older and young workers together helps both groups perform better. They make good allies in part because of their similar interests, but because of their different stages of life, they are less competitive with each other than workers in the same age cohort might be. That means that they are more likely to help each other and to form good teams.

The bottom line is that companies looking to increase engagement, performance, and loyalty need to do a much better job of engaging this growing — and valuable — segment of the workforce. For employers who say they want a workforce that can “hit the ground running,” that doesn’t need training or ramp-up time to figure out what to do, that will be conscientious, and that knows how to get along with others, older workers are the perfect match.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers