Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1348

October 23, 2014

Why We Need to Outsmart Our Smart Devices

Most commentary about the Internet of Things assumes that we sacrifice privacy and security for huge efficiency gains. But what if the notion underlying that tradeoff — the idea that more connectivity always means greater efficiency — is flawed? What if indiscriminate information sharing has the same drawbacks with devices as it does with people?

Research shows, after all, that privacy is a source of productivity in organizations. And excessive transparency — in a totally open work environment, for example — makes us less productive and squashes creative problem solving. When we know we’re being closely monitored, we tend to stick to protocol, even when it’s inefficient.

Too much transparency between smart devices can have a similar effect. As much as we’d like to think that all the devices in our cars (and the cars around us) are talking to one another just to keep us safe, they’re also talking about us — and transmitting our data for analysis. Of course, when devices track our behavior on the job, we’re keenly aware of being watched and evaluated. It’s as if the boss is right there every second, noting every misstep. So we don’t take chances and innovate — unless we feel assured that our data won’t be used against us.

So, how much “talking” should devices do? Executives at a large gas utility wrestled with this question when HBS researcher Shelley Xin Li and I conducted a recent field experiment involving its service mechanics. The company had put in place advanced mobile technology that has become increasingly standard — for instance, laptops in every truck connected to the central dispatch and order system — to track the mechanics as they did their jobs. The goal was to provide developmental feedback and help the mechanics deliver more efficient customer service, but executives weren’t sure how to report the data they gathered.

They considered making it available to everyone, so that each individual would know how she or he ranked in performance compared with anyone else at any given time. Such real-time transparency, they thought, could increase motivation, promote a culture of fairness, provide feedback for self-improvement, and give managers better tools for developing their people.

But the executives could also imagine how unrestricted access to the data might have deleterious effects on culture and performance. It could undermine employees’ willingness to experiment, for instance, and result in missed opportunities for process improvement. Indeed, studies show that it is far easier to demotivate people (at either the top or the bottom of the performance curve) by being transparent with them about their performance than it is to motivate them with similar tactics.

So far, the company seems to have struck the right balance for its employees: sharing team performance with everyone but making individual data available only to the worker in question. Internal focus groups felt that “the culture’s focus on collaboration and productivity” would give way to competition if each person’s data were out there for all to see.

UPS is another company that’s had to sort out how visible to make its real-time performance data. Although its trucks don’t drive themselves yet, they’re loaded with sensors that record drivers’ every move and send the results to computers in New Jersey for data crunching. But in order to use the data to improve efficiency and driver safety, UPS engaged in a prolonged negotiation with the drivers and their union. Their Master Agreement acknowledges that “there have been problems with the utilization of technology in the past” — that is, it’s been used for disciplinary action rather than its intended developmental purposes. Now, UPS has tighter restrictions about sharing the data only for driver development (unless someone intentionally defrauds the company).

As these examples show, it’s not easy to find the right interface between human beings and smart devices. Increased connectivity and transparency can cause employees to engage in unproductive behaviors to ward off retribution. Both the gas utility and UPS have invested a lot of time and money to find the right level of privacy for them — and companies will increasingly incur those costs as the Internet of Things becomes more prevalent in the world of work.

What’s more, devices aren’t always right about us. And we waste energy (and put a drag on productivity) trying to fool them into being right. Consider what happens when the office lights automatically turn off because you haven’t moved and the sensor thinks you’re gone. You wave your arms madly in the dark, waiting for the lights to come back on. You flick the switch to no avail. You walk out of the room and back in again, maybe do a few jumping jacks. This device that’s designed to make your life easier — and does, on the plus side, prevent you from leaving the lights on all night — is also creating headaches by sharing the wrong information about you.

Just imagine what the repercussions would be if your smart office gathered inaccurate data about your performance — for instance, logging fewer hours than you’ve actually put in, because you weren’t at your desk the whole day or didn’t use your computer or phone for an extended period. What workarounds would you devise? Would you feel obliged to sit dutifully at your post, tap-tap-tapping away, rather than getting up to ask people questions and put actual heads together? I know I would.

Maybe the answer is to make devices even smarter, and version 2.0 will solve everything. But more likely, we’ll have to come up with better and better ways to outsmart them.

A Military Leader’s Approach to Dealing with Complexity

The most effective leaders I’ve known or studied all share a common trait: they were unwilling to settle for the existing state of affairs. They believed with all their heart that what we focus on can become reality.

In my quarter-century of military service, I’ve been afforded the rare privilege of leading in a broad array of environments: commanding a 500-person special operations expeditionary air refueling group in the Middle East after 9/11; guiding a 7,000-person military community through a dramatic mission transformation in North Dakota; and leading men and women from 14 NATO nations in building a sustainable, independent Afghan Air Force in an active war zone—something that had never previously been attempted.

I know how daunting it can be to lead dedicated professionals to undertake complex endeavors, and I’ve lived the reality of trying to bring positive change to large, bureaucratic organizations. Here are four principles I’ve learned that can help you enhance your leadership while concurrently bringing out the best in those around you.

Principle 1: Craft your vision in pencil, not ink.

It is a well-accepted role of leaders to focus on the future and pursue the possibility it holds. In other words, leading entails being a visionary—confidently looking ahead and ascertaining how best to transform your current reality into your desired future. One of the most significant errors I see leaders make is developing their vision in isolation and then expecting people to accept it at face value. When leaders do this, they violate one of the most important truths of promoting change: our words create our worlds. How we choose to describe and discuss what we are doing and where we are going is important, but what moves people to sustainable, self-motivated action is understanding the why behind the vision. That vision can only be fully realized if leaders involve others in the process of creating it.

Ultimately, what makes a vision come to life isn’t people understanding it, but people choosing to own it. Making inclusivity a priority will increase ownership, enhance motivation, improve information sharing, and result in leaders making wiser, more informed choices.

Principle 2: Believe no job is too small or insignificant for anyone, especially you.

For those of us who have served in uniform, getting dirty, sleeping in tents, leading marches in the mud, or spending hours rehearsing a mission comes with the territory. As a commander, you don’t get a pass because you have the highest rank. In fact, you should be ready to be the first to face hardship and the last to benefit from success. If your team is cold, wet, hungry, and sleepless, you should be, too. You should be prepared to eat last, own failure, and generously share triumphs. This others-centered approach to leading will build deep trust and enduring respect, and reinforce that you don’t expect anyone on your team to do anything you wouldn’t do yourself.

Ego tempts many leaders toward self-aggrandizement—the higher their rank, the more pronounced the pull. Choose to direct your effort and attention toward what you can give rather than what you can receive. Demonstrate humility, not superiority. Model for others the selfless attitudes and behaviors you desire to see in them.

Principle 3: Remember that l eaders should be generalists, not specialists.

Nobody can be an expert in everything, but the greater your scope of responsibility as a leader, the more you need to learn about what you are demanding of your people. Just like the best sports coaches, who invest countless hours in understanding every position on the field, effective leaders develop a keen sense of how the organization’s various roles, functions, systems, people, and processes contribute to achieving its desired goals. You may be a specialist at one thing, but knowing what others around you do—and how and why they do it—is vital not only to attaining your desired outcomes, but also to realizing your individual and collective potential.

Don’t allow yourself to become stale or small-minded. Make it a personal priority to know more about what is going on around you. If you spent the bulk of your career working in sales, accept a stretch assignment in business development or talent management. You will likely be pleasantly surprised at how this broader, richer view of what’s happening in your organization will enlarge your perspective, enhance your appreciation, and elevate your sense of personal satisfaction.

Principle 4: Recognize that every interaction is an opportunity to equip, engage, empower, and inspire those around you.

The world of physics has a principle: “Every contact leaves a trace.” What this means for leaders is that every interaction with someone—verbal, written, or even through non-verbal mannerisms—makes an impression. Effective leaders understand that every interaction is a potentially powerful means of nurturing a relationship, eliminating an obstruction to progress, or reinforcing trust. Determine to leave a trace that leaves those around you better for knowing you.

Do your part to seed an environment where everyone is compelled by your example. Adopt a walk-the-floor policy instead of an open-door policy. Visit with people in their space. Don’t make them come to yours.

Military work is risky, pressured, and ever-changing. Yet the principles military leaders use to lead effectively are the same skills companies need today to prevail in a climate of increasing uncertainty and accelerating complexity. It is up to each individual leader to choose to put these lessons to work.

Predictive Medicine Depends on Analytics

Regression models, Monte Carlo simulations, and other methods for predicting what’s around the corner have been in use for decades. It’s only recently, though, that advances in information technology have made it possible for predictive tools to access and manipulate big data, and to do so continuously — accelerating the generation of insights, and opening up opportunities to anticipate issues with unprecedented precision. Think of the colleges that are increasingly able to identify students at risk of dropping out and intervene before they do. Or lenders’ enhanced abilities to gauge credit risk. Energy, agriculture, insurance, retail, human resources — no industry is unaffected. But nowhere is the potential of this new era of opportunity more apparent and exciting than it is in health care.

Predictive analytics is fueling a transformation from a focus on the volume of procedures to the value of outcomes. Predictive tools are helping providers — both doctors’ groups and hospitals — assess patients’ risk of contracting a whole host of diseases and conditions. They can come up with individualized regimens by tapping into electronic medical records to identify the types of patients who are most likely to respond to a particular type of therapy. They can pinpoint treatments that sustain health in a more precise way than ever before. And they can identify individuals who are likely to stop benefiting from a specific regimen at a given time. For the volume-to-value paradigm shift in health care, predictive analytics, though rarely visible, is the essential enabler.

Used to its full potential, this is predictive medicine — the ability to integrate and analyze known disease characteristics with a specific patient’s history and health status, and use the resulting insights to change outcomes and inform new directions for life sciences research and development. And in this new arena, the once-clear lines between companies that make drugs and medical devices, providers who diagnosis illnesses and treat patients, and payers who provide the financial support for care are blurring. Actors in this ecosystem are increasingly working together rather than handing off information or tasks to the next entity in a linear process. They are establishing more iterative and interactive connections with each other and with patients. They are collaborating with (sometimes highly unlikely) partners. They’re also sharing risk.

The new business model has yet to solidify, and the leaders have yet to emerge. The positions are there for the taking. But not for long. That’s why pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device companies need to define their relevance in this new health care ecosystem, and soon.

Life sciences companies, for example, might consider staking a claim in the quest to lower hospital admissions and readmissions by working with providers on tailored plans for hospital patients being discharged, based on each individual patient’s propensity to comply with treatment and respond to it.

Consider: Carolinas HealthCare System (CHS), a network of hospitals with more than 900 care locations in North and South Carolina, recently lowered readmission rates by a third by using software from Predixion, a California-based software company. In this particular application, CHS gave its nurses point-of-care information on their patients so that when they were about to be discharged, the nurses could customize clinical interventions based on an individual patient’s predicted risk of readmission. This was a notable success — but what if we combined the insights and resources of a life science company and health provider that were both focused on, say, acute cardiovascular diseases? How much greater would the potential for lowering readmission rates be then?

The options are tangible. Imagine a scenario where a pharmaceutical company marketing a heart failure medication approaches its institutional customers — health systems, hospitals, urgent care centers, and other providers — with a risk-shared value proposition. The contract calls for the provider to use certain evidence-driven predictive analytics tools to define treatment options and possible responses. When predefined treatment goals are attained, both parties contractually benefit. Risk and outcomes, as the scenario plays out, will be managed by predictive models, which are powered by machine learning algorithms that will improve their accuracy rates over time.

Consider another scenario focused on compelling patients to stay the course with treatment. One estimate of the annual cost of medication noncompliance in the United States pegs it at a hefty $289 billion. What if a pharmaceutical company took the lead in conceptualizing and executing a collaborative solution, using predictive analytics to assemble and deliver a package of product and service offerings to motivate patients to stay on track? Think of it as a 360-degree/24-7 support system. It’s not hard to envision; we’re seeing just these sorts of systems popping up — informally, and disconnected from health care providers — with wearable fitness devices that share information among groups of users. With a focus on adhering to treatment, patients, providers, risk bearers, and life science companies would all be beneficiaries.

Medical device companies have begun using predictive analytics and other big data technologies in certain areas of their businesses. For example, consider Minneapolis-based medical device company, Medtronic, which develops diagnostic and intervention devices for cardiac and vascular diseases, diabetes, and neurological and musculoskeletal conditions. Medtronic is using big data and advanced analytics to drive their approach to patient and physician support and manage supply chains.

We’re also seeing some leading pharmaceutical companies — Merck Global Health Innovation, for one — investing and establishing operations to capitalize on new investments in advanced analytics. But this shift shouldn’t just be about capabilities. Life science company executives need to be thinking about what business they want to be in. They need to be thinking about how — and how much — they will develop and integrate predictive analytics capabilities into their services. They need to consider offering services enabled by advanced predictive analytics. And they need to consider business models where partnering to integrate the care that patients receive outside of the walls of provider entities is central to their value proposition.

The variety, velocity, and volume of health care data are allowing predictive analytics solutions to emerge quickly. And while the most visible immediate benefit is cost reduction, the real motivation is a patient-centric business model — one that recognizes that health and care management needs to occur wherever the patient is, not just in hospitals or physician offices. The goal (and it’s within our grasp) is threefold: improve clinical outcomes, enhance patient satisfaction, and drive more value to the entire health care system.

Australia Tries to Keep Older Workers in the Workforce

When Australia introduced its age pension in 1909, only 4% of the population was living long enough to claim it. Today, with life expectancies growing, 9% of Australians draw a full or partial government-funded age pension, often for more than 20 years, according to the Academy of Management Journal. Australia plans to incrementally increase the official retirement age to 70 by 2035, making its retirement age the highest in the world, and the government has a plan to offer cash incentives for companies that hire unemployed people over 50.

Help Your Team Spend Time on the Right Things

What is the most common resource that’s always in short supply? The answer, of course, is time. This applies not only to your time, but to your team’s. It’s the one organizational resource that is neither expandable nor renewable. Therefore, making sure that time is spent in ways that will have the biggest impact is a critical determinant of organizational success.

Unfortunately, many managers don’t think about time as a finite resource in the same way that they consider the limitations of headcount and budget. Therefore they don’t hesitate to give their teams more assignments without taking any away. The consequence of this is that their people work longer hours – and it’s often not clear what’s actually important and what can wait. This cascades through the ranks so that almost everyone feels overstressed and overworked. As one senior executive sadly said to me, “There is no time in the year anymore when things quiet down.”

But steps can be taken by managers to overcome this dynamic and better leverage organizational time. The first is to sharpen their vision of what their unit needs to do better in the next year or two, so that the priorities are clear. The second step is to free up time to move towards that vision by consolidating, eliminating, or streamlining current activities. The third step is to reallocate the newly liberated capacity to short-term experiments that will help them learn how to get to the vision quicker and with greater impact.

Let’s look at the Americas Field Marketing organization for Cisco Systems, as an example of this three-step process. For two years, this nearly 130-person unit had worked hard to drive customer relevance, generate demand, and increase loyalty in partnership with its sales teams across North, South and Central America. They had organized tradeshows, delivered direct marketing, generated leads, and provided useful customer insights – the basics of a successful marketing organization.

During this time, however, Cisco’s customers were beginning to purchase and use technology in new ways. Increasingly, tech-savvy business managers, instead of just IT professionals, were making buying decisions; user-generated applications were being added on top of the basic technology; cloud computing was becoming prominent; and digital media was becoming a key influence in deciding which technologies to purchase. Customers were self-educating and researching buying decisions in new ways – not just with a sales person.

In the face of this new reality, the marketing leadership team realized that many of their traditional face-to-face activities were no longer sufficient. So at an offsite, they began to develop a vision for Marketing 2.0 – with a focus on data analytics, cloud marketing, more targeted use of Cisco.com, 3rd party websites, and social media, and better identification of organizational buyers – all in support of generating better leads (and better tools to build customer relationships) for the Cisco sales teams.

While all of this was very exciting, the reality was that there were no new resources to dedicate to this work. Sales was still dependent on them to do the traditional marketing activities. As a result, the Americas Field Marketing leadership team shaped “capacity creation” projects to get the current work done with fewer resources or less time. This allowed them to redeploy time to new initiatives.

For example, one project was to consolidate similar types of marketing support across several sales groups. Another was to identify low payoff events and stop supporting them. In addition, the marketing team was encouraged to avoid low priority requests from sales. For activities with no demonstrable impact, they were told to answer with a polite “no,” followed by suggestions for more impactful options.

With extra time available, the leadership team commissioned several new pilots that would move the marketing organization towards vision 2.0. To make sure that the pilots wouldn’t become time sinks and would actually get finished, each one was designed to be narrowly focused on a particular aspect of the new vision, involve a limited number of people, and to be completed in 100 days or less. One of these “rapid results” projects was aimed at learning how to take advantage of data analytics. It achieved its goal of integrating digital behavioral data about customers in one country in order to increase their engagement by 20% in 60 days. Another successful project focused on increasing the collaboration between sales and marketing in one market to improve lead conversion rates by 16% in 100 days.

Naturally, this kind of transformation is not a one-time effort, but rather an ongoing process that needs to be continually refreshed and refocused. In the case of the marketing group, the leadership team now considers the portfolio of capacity creation and rapid results projects every quarter, as they move toward their Vision 2.0, so that they can continue to learn, build on what works and what does not, and make adjustments.

There also are skill challenges involved in pulling this off. At Cisco, for example, it became clear that some people did not necessarily have the skills needed for the new kinds of marketing work. So the marketing leadership team had to figure out how to create a more dynamic staffing model for their work through a combination of training, new hires, temporary assignments, and natural attrition.

New initiatives are necessary to move an organization forward. But without a conscious ongoing strategy for managing the time involved, the chances of success may be limited and short-lived.

October 22, 2014

Cable Providers Win Even in an a La Carte World

When HBO and CBS announced that they’re going to go over the top (OTT), offering their programming to internet users who don’t have cable subscriptions, the news was greeted in some quarters as the beginning of the end of cable TV. Thomas Hazlett, a George Mason University economist and author who has been studying the cable business for three decades, tends to scoff at such predictions. But the news has at least made him sit up and pay attention.

“For some time, I’ve had trouble explaining the OTT phenomenon in terms that did not seem dismissive,” Hazlett says. “It’s been real, but very much on the margins. The cable/telco/satellite subscription model has held steady in subs and revenues, adjusted for macro-economics factors. Yet, with the HBO announcement, my reflex reaction is: now things are getting interesting.”

But for Hazlett, interesting doesn’t mean cable TV is facing its demise. If anything, he views HBO’s move less like sedition and more like uncertain hedging, and one that could help platform players ultimately continue to thrive.

It turns out that consumers of cable TV have a lot in common with the cable providers they love to complain about. You don’t like having to pay for huge bundles of channels no one watches? Neither does Comcast.

The real power players in the current arrangement are the cable channels.

Providers want to offer popular channels like ESPN and Discovery on a basic tier, because they get people to subscribe to cable. But content creators like Disney (ESPN’s owner) and Discovery tell them that to get those popular channels, providers must also bundle SoapNet, or the Science channel, and dozens of other channels. Oh, and they’ll have to pay a higher license fee for the main channel they want as well. All a network needs is one really popular channel to create that leverage.

This bundling system has been preposterously great for the content companies. Hazlett reports that the cable revenues were split 90/10 between cable providers and cable networks in 1990. By 2005 it was 50/50. Between 1999 and 2008, the number of cable networks doubled, but cable network revenue tripled to more than $42 billion. Cable providers have passed their increased programming costs on to consumers. Expanded basic cable costs 188% more than it did in 1995. (Drastically more than either inflation or wages in that time frame.)

Meanwhile, forcing dozens of channels into the basic tier also gets the programmers instant scale–110 million households–for advertisers. “The strong channels carry the weak ones,” explains Hazlett. “It’s a marketing ploy to get fledgling networks established.” Sometimes this doesn’t work (CNNfn); sometimes it works brilliantly (The History Channel).

And while the networks reach all those households, they don’t have to market to all of them. The service providers are doing that for them by selling subscriptions with their channels. “[Cable networks] don’t want to deal with the mass market,” Hazlett says. “They don’t want to sign up 100 million customers, they want to sign up 20 providers.”

So where does that leave the cable providers?

For them, change will be tougher. Hazlett says that platform players like Verizon and Comcast can’t mimic the a la carte strategy because of the 1992 Cable Act, which mandates that all cable providers’ offers must start with a basic tier that includes the over-the-air channels, the so-called “buy through provision.” You have to buy through the basic tier; additional channels must be on top of that. Even if they wanted to sell you just a broadband pipe plus just ESPN or HBO, they can’t without a policy change.

Hazlett’s not convinced the providers want to do that anyway.

“People think the the service providers are in the programming business, but programming has always just been one of the main inducements to the platform.” he says. Even if you’re streaming shows over the internet, “you still need [internet] bandwidth coming to your house to get it onto your screens. And Verizon and Comcast and those guys are in the best position to sell you that, probably at a higher price than they do now. It will certainly be lower cost for them if they get out of or reduce their participation in the programming business, because there won’t be those massive license fees going out the back door.” That means that a new, a la carte world might be even better for cable providers than the current system.

If this ever happened, it wouldn’t be for a while. “Cable has legs left. The hip tech blogger view is that cable is a dinosaur. But if you look at subscriber numbers, there’s not a lot of migration away from cable.” Although, Hazlett concedes, “You’re seeing a lot of it with Millennials, yes.” They are the least likely to subscribe to a cable bundle and most likely to watch programming on different devices.

And that means the recent HBO and CBS announcements are less a harbinger and more of a hedge. Or as Hazlett calls it, “a straddle.”

Get the Millennials who don’t have cable to subscribe to HBO. If their media consumption habits stay unbundled over time, or if the world moves that way, you got ‘em. If they get married, have kids, move to the ‘burbs and sign up for cable — young families have always been the target demographic for the cable providers, they’re too busy to worry about managing their media habits — well, you still have contracts with the providers so you still got ‘em.

Ultimately Hazlett keeps coming back to the notion that the favorable economics of cord-cutting aren’t necessarily sustainable. Before streaming services were even a thing, in 2006, he argued in a paper cleverly titled “Shedding Tiers for a la Carte” how regulation and other market conditions made it such that “restricting the basic tier… to just those…channels a given subscriber prefers is actually more expensive than providing the large tier to all.”

OTT services like Netflix and HBO Go seem to have changed that calculus by coming in with a lot of content at a much lower cost, but they still rely on the internet bandwidth going into the house, cable providers have priced, thus far, as all you can eat. That means that the favorable economics of paying only for the content you use relies, ironically, on cable providers not pricing internet bandwidth that way, because if it were, some of the heaviest users would be paying much more for it. “Consumers say it’s unfair that they can’t pay for only what they use when it comes to programming,” Hazlett says, “but if you tell them they’re going to pay for bandwidth by getting charged for what they use, they say that’s unfair, too.”

What Hazlett doesn’t see right now is any one company or model with the inside track on the future of TV. “It’s all in flux. No one knows really where it’s going to go,” he says. “There’s a graveyard of failed experiments and it’s growing. And we’re going to see Apple TV, Roku, Google, Sony, Samsung, and others we’ve never heard of all take more shots at this. No one’s gotten it right, and that includes Netflix, which I think may be in the most precarious position of all.

“All these players are trying to get in there, get a spot on the food chain. There’s intense competition everywhere. This is capitalism. It’s fun to watch.”

The Sectors Where the Internet of Things Really Matters

The Internet of Things is emerging as the third wave in the development of the internet. While the fixed internet that grew up in the 1990s connected 1 billion users via PCs, and the mobile internet of the 2000s connected 2 billion users via smartphones (on its way to 6 billion), the IoT is expected to connect 28 billion “things” to the internet by 2020, ranging from wearable devices such as smartwatches to automobiles, appliances, and industrial equipment. The repercussions span industries and regions.

At Goldman Sachs, we see numerous triggers turning the IoT from a futuristic buzzword to a reality. The cost of sensors, processing power, and bandwidth to connect devices has dropped low enough to spur widespread deployment. Innovative products like fitness trackers and Google’s Nest thermostats are demonstrating the potential for both consumers and enterprises. And corporate alliances are taking shape to set the standards needed to integrate the wide array of devices in a cohesive way.

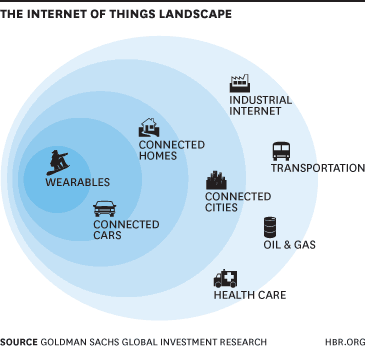

While these enablers make the IoT possible, its long-term success depends on the use cases that help realize the economic potential of connecting billions of devices, either to improve quality of life or save money. We focus on five key verticals where the IoT will be tested first: Connected Wearable Devices, Connected Cars, Connected Homes, Connected Cities, and the Industrial Internet.

Early adopters in these verticals are using the IoT to pioneer new product areas and to find efficiencies that save money or reduce demand for resources. In wearable devices, new consumer categories are emerging in fitness bands, action cameras, smart watches and smart glasses. Cars are becoming more connected with each new model, driven by infotainment, navigation, safety, diagnostics, and fleet management. Consumers in these verticals are able to see the internet extended beyond desktops and mobile devices.

Connected Homes are perhaps the clearest next proving ground for the IoT, combining both the potential to spawn new lines of products and services in areas such as security cameras and kitchen appliances, and the chance to reduce energy use and costs through smart thermostats and HVAC systems.

We believe this segment could generate meaningful revenue in the near term. Samsung said at its 2014 investors forum it expects the global Smart Home Device market to reach $15 billion in 2015, almost doubling from 2013’s $7.8 billion. Samsung expects the bulk of this opportunity to be driven by the U.S., U.K., Australia and China.

In connected cities, the U.S. has emerged as a leading adopter of smart meter technology for power utilities, approaching 50% penetration of 150 million total endpoints. The initial foray into connected cities was catalyzed by over $3 billion in stimulus funding and support for smart grid technology as part of the 2009 American Recovery and Restoration Act. Government initiatives are likely to drive growth internationally as well. In Europe there is a target for 80% of households to have smart meters by 2020.

Smart meters and the grid network architecture lay the foundation for further connectivity throughout cities, including smart street lighting, parking meters, traffic lights, electric vehicle charging, and others. According to The Climate Group, a non-profit organization dedicated to reducing carbon use, combining LED lamps in streetlights with smart controls can reduce CO2 emissions by 50%-70%.

Within the vast Industrials sector, the IoT represents a structural change akin to the industrial revolution. Equipment is becoming more digitized and more connected, establishing networks between machines, humans, and the internet and creating new ecosystems. While we are still in the nascent stages of adoption, we believe the Industrial IoT opportunity could amount to $2 trillion by 2020. Included within this Industrial category are numerous sectors, from transportation to health care to oil and gas, each of which will be affected.

Specifically, we expect IoT to impact three main areas within industrials: building automation, manufacturing, and resources. Factories and industrial facilities will use the IoT to improve energy efficiency, remote monitoring and control of physical assets, and productivity.

With several infrastructure booms coming to an end and rising cross-border competition, industrial companies are looking for new sources of growth. Fixed investment is moving away from traditional capital goods equipment, creating new business models that more seamlessly integrate hardware and software, which support recurring revenue streams and greater customer stickiness.

As with any gold rush, the early winners from the IoT are likely to be the suppliers selling the “shovels” to make the connections possible and to process the vast amounts of data. But in the long run, the ultimate impact of this third wave of the Internet depends on the adopters in these proving grounds finding gold in connecting billions of devices into an intelligent network.

This article is drawn from a series of Goldman Sachs research reports on the Internet of Things that has included contributions from more than 20 analysts across multiple sectors.

Design a Workspace that Gives Extroverts Privacy, Too

Some of the most unlikely people have confessed to being introverts lately. One recent acquaintance–while chatting amiably during a pre-event networking session– leaned over to quietly tell me that she is actually an introvert. She felt she had to learn more extroverted behaviors to succeed in her career. And she’s not the only one.

It seems like everyone is talking about where they are on the introversion spectrum these days, and for good reason. Since Susan Cain, author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking delivered her TED talk in 2012, the public has become more aware of this important aspect of our personalities, and how it impacts our behaviors, emotions and decisions. We now know that introverts aren’t shy, they simply respond to stimulation with greater sensitivity. They are thoughtful people who don’t dominate a conversation or command attention, but their preference for solitude leads to deep insights and creativity. Being an introvert is no longer a problem to be solved or covered up – it’s become kind of cool. And businesses are looking for ways to offer introverts the solitude they crave at work.

Extroverts, meanwhile, seem to be getting a little less attention. Because they love socializing and comfortably spend large chunks of their day interacting with others, working in open spaces seems ideal. In our workplaces at Steelcase it’s pretty easy to spot an extrovert. You can almost always find them in open, community spaces like our Work Café, which is a place that blends the vibe of a coffee shop with a range of work settings where people can collaborate, work individually, or chat with coworkers. It’s the hub of our campus and a great place to see or be seen — an extrovert’s paradise.

But even extroverts get worn out by the amount of stimulation everyone faces. We’re bombarded with information: according to The Happiness Advantage author Shawn Achor, people receive over 11 million bits of information every second, but the conscious brain can only effectively manage about 40 bits. Our technology allows work to follow us everywhere, even into places like the bedroom and bathroom that used to be non-work sanctuaries. We’re collaborating with teammates for longer stretches of time – sometimes the whole workday – requiring longer hours to handle our individual tasks. Even in countries like France and Germany that have long valued the separation of work and life, our jobs have seeped into nights and weekends. The pace of work has intensified everywhere. Which means that everyone – including extroverts – needs access to private places to get stuff done, or simply take a breather.

As humans we need privacy as much as we need human interaction. But too often our workplaces are designed with a strong bias toward collaboration and social connections, without adequate and varied spaces for concentration and rejuvenation. Distractions are troubling for all of us, but extroverts can find them irresistible. We found a number of design strategies to support extroverts’ need for privacy. Here are some ideas:

Extroverts are drawn to social interactions. Create “quiet zones” for individual work that reduce the temptation to interact with others. Orient the furniture to avoid conversations and eye contact.

Create private areas that have frosted glass or other treatments that allow light in, but manage distractions. Situate these in low-traffic areas that limit the temptation for extroverts to look up and engage with passers-by.

Provide enclosed private areas with strong acoustic properties to keep noise out. Extroverts are enticed by conversations, so make sure there are sound seals that minimize or eliminate voices, allowing extroverts to stay focused.

Schedule “quiet time” for everyone to focus on their individual work. The social convention of this practice will help extroverts allocate time that is “interaction-free.”

Help extroverts shield themselves from visual distractions with opaque walls or movable screens.

Extroverts need respite from the intensity of work. Create places with soothing textures, sounds and vistas, where they can seek solitude and rejuvenate.

For these ideas to work, organizations need to embrace the notion that seeking privacy is not anti-social, but part of an essential balance in our workday. Extroverts, as well as introverts, need permission to seek alone time when they need it to do their best work.

When It Comes to Data, Skepticism Matters

Managers should rarely take an important analysis at face value. They should almost always dig into the data and develop a deeper understanding of the hidden insights that lie within. Sometimes there are real gems awaiting discovery. Other times the data contain some truly snarky beasts, and failing to spot them soon enough presages real danger.

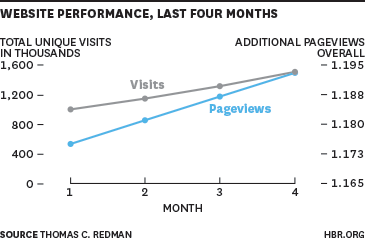

Consider a (hypothetical) company that is trying to drive traffic — especially mobile traffic — to its website. Once people arrive, it wants to keep them there. So two statistics of interest are the number of unique visits and the number of additional page views. The figure below presents results over a four-month period for both variables.

According to the graph, the trends look great, and it’s easy enough to conclude that whatever the company is doing is working, and it should keep it up. One may even be tempted to predict that these efforts will yield even better results in the future.

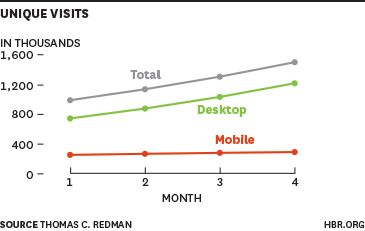

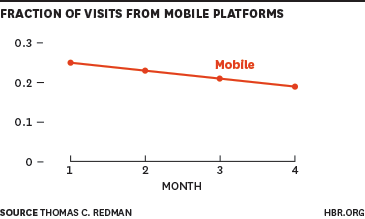

But not so fast! Recall this company has a special interest in mobile platforms, so a deeper look is needed. The next figures provide that look. The first breaks total unique visits into its mobile and desktop constituents, respectively.

It is easy enough to see the terrific growth in desktop traffic. Mobile traffic is also growing, but much more slowly. It is a positive result, but not the most desired one. What’s going on? Could it be that efforts to drive traffic are reaching desktop users, but not mobile users? Or maybe visitors using the mobile platform find something compelling and then visit from their desktop later, when there is more time? Or maybe users don’t like the mobile platform? Could there be some external factor (not related to company efforts) that is causing people to use their desktops? We can’t tell from these data — clearly a deeper look is needed to understand root cause.

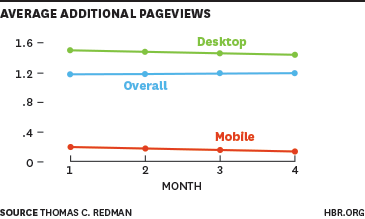

Now let’s look at those additional page views, once people are on the site. The next results are downright mysterious. The figure below shows that, while average additional page views per visit is going up overall, they are going down for both mobile and desktop platforms. This is both surprising and counterintuitive! How can a statistic be trending down for both groups and up overall?

The answer to that question involves Simpson’s paradox. Here, during the first month, mobile traffic was a full 25% of the total. But desktop traffic is growing faster so, by month four, mobile traffic was only 19% of the total (see the figure below). Since desktop visitors view a full additional page, on average, as the months go by they drive the overall average up.

Fortunately, the deeper look revealed the snarky beast. This company now knows that efforts to increase additional page views per visit are not working for either the mobile or desktop platform — even though the first look showed great promise. They must adjust their plans.

What should managers take away from this example both as they seek to understand results brought by others and dive more deeply into data themselves? First, it is too easy to be seduced good news. If something looks too good to be true, it probably is. So be skeptical — very skeptical. Always make sure that important results hold up to a deeper look and, if they do not, get the full explanation.

Second, don’t be satisfied with “analyses of the average.” Here, for example, mobile and desktop comprise distinct subpopulations. Look for them and develop an understanding of how they differ from one another.

Third, if an analysis violates the conventional wisdom, expect some tough (but fair) questions, spirited debate, and even a certain measure of hostility. Dig as deeply into the data as you can, make sure the data can be trusted, and make sure you understand not just the data but the real-life processes that produced them. When you can, seek confirmatory data and develop completely different ways to explore the conventional wisdom.

Fourth, these points aside, don’t be consumed by analysis paralysis. When the time comes to make a decision, do so. See what happens and reevaluate constantly.

Keep in mind, though, that you can’t just question the positive. I could just have easily told a story that started with a negative result, camouflaging the good news underneath. Sometimes you have to reverse these questions.

The bigger and more complex the business problem/opportunity and analyses, the more important these lessons. I’ve crafted this example to be as simple as possible — there’s no bad data, random fluctuation, time pressure, or hidden agenda obscuring the issues. These forces rear their heads in the hurly-burly of real life, and it takes hard work and more courage to follow them. Of course, this is when it matters most.

Successful Innovators Don’t Care About Innovating

Successful innovators care about solving interesting and important problems — innovation is merely a byproduct. If this distinction seems like hair-splitting, it isn’t. The two focuses create vastly different realities.

Focusing on innovating — as a worthy goal unto itself — tends to be born from self-centered motives: We need to protect ourselves from competitive forces. We need to ensure we have a growth engine. We need to keep up with other companies. To do all these things, we need to innovate. This is often a CYA perspective coming from an executive suite looking to protect its turf. It isn’t inherently bad. It’s just that this focus tends to create a culture where customers are on the sidelines, not in the center of the dialogue.

By contrast, focusing on solving interesting and important problems tends to be born from customer-centered motives: What’s going on with this set of customers? Where are they ecstatic? Where are they upset? Where do they feel good? Where do they hurt? How can we better serve them? These types of questions pull customer problems front-and-center and create a culture where that’s expected. And since people naturally want to solve problems, it pulls for innovation.

To illustrate, consider paint maker Sherwin-Williams, a company that has long been obsessed with solving painting contractors’ problems.

Twenty-five years ago while doing customer research, Sherwin-Williams uncovered an important insight: Contractors tend to make paint-buying decisions based more on proximity to job site than brand of paint. To them, time is money. This led to a hypothesis that saturating a market with stores to ensure there’s a store close to any job site will produce outsized market share growth. This was a new and innovative idea in a pre-Starbucks-on-every-corner world. Sherwin-Williams tested the hypothesis in four markets and it worked. But as they tried to roll it out to more markets, competitors quickly caught on. Suddenly it became a race for real estate and competitive advantage was lost.

Fast forward 20 years. During the 2009 recession, Sherwin-Williams’s competitors started shuttering stores in order to cut costs. Despite strong shareholder pushback, Sherwin-Williams did the opposite, opening 60–100 stores per year during the downturn. It was a risky bet, but they didn’t want to miss the opportunity to be close to customers when the market inevitably rebounded. When it did rebound, revenue growth far outstripped that of competitors. Sherwin-Williams’s stock price has quadrupled in the past five years.

So what’s the takeaway? Market saturation was an important distribution innovation, but it wasn’t what drove success for Sherwin-Williams. Success came from an unrelenting focus on solving contractor problems. That focus generated the initial innovation, but more importantly it generated the conviction to stick with the innovation when the going got tough.

When I asked Bob Wells, the Sherwin Williams SVP who shared this story with me, what he felt has driven the company’s success over the years, the word “innovation” never came up. But the word “customer” did — a lot.

“We’ve always looked at business more like dating than war,” Wells noted. “It’s a theme that runs through our 140-year company history. In war, you’re focused on beating the competition. In dating you’re focused on strengthening a relationship. That difference of perspective has a million knock-on effects for how decisions get made.”

Wells’s comment points to a truth so often missed in today’s let’s-get-some-innovation-in-here-quickly climate. Successful innovation is a mindset before it’s a process or outcome. It’s characterized by a dogged determination to see the world through your customers’ eyes. That mindset drives all the little details and decisions that can’t be captured in a process.

So how can you foster this mindset if it’s not already present in your organization? The simple answer is you just start doing it, even if you’re the only one. Disabuse yourself of the notion that innovation is some high-minded creative process reserved for a certain class of people. Remember that most great innovations have been developed by regular people inspired by a problem.

Get out of the building and talk to your customers. Listen to their challenges. Come up with back-of-the-envelope, harebrained ideas about how you can help them. Get comfortable with the idea that you’ll throw 99% of those envelopes in the trash. When you lose your motivation, go back to the problem statement. Never stray from the problem statement. Let it inspire you. Let it lead you. Also, stay mindful that problem statements shift and move. Never stray too far from your customers either.

Before long you’ll embody a customer-centered, problem-focused mindset. You’ll inspire others to start embodying it too. That’s the only way innovation ever really happens. Before all the fancy processes, there’s always a few people with a fire in their belly put there by a problem they can’t help but solve.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers