Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1345

November 4, 2014

We Need More Transparency on the Cost of Specialty Drugs

The economics principle “The more you concentrate your buying power, the better your pricing” applies in health care, too. That’s why health insurance companies can offer customers lower premiums by restricting the size of provider networks. They send more patients to fewer hospitals — and get a better deal per patient, passing on at least some of the savings to you.

Next up for restrictions: specialty drugs. These expensive medicines treat diseases, such as specific cancers or multiple sclerosis, that affect relatively small populations. That means you may not get the drug your doctor wants to prescribe — or if you do, it will cost you a lot more money.

Theoretically, there’s nothing wrong with this. If the choices are medically appropriate, the savings to the system should justify the restrictions. But that’s a big “if.” We don’t know how a payer decides to give one specialty medicine preference over another. The drug formulary is a giant black box.

If this opaque process yielded good decisions, you could stop reading now. But it doesn’t. Brian Bresnahan and colleagues have found that pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committees sometimes favor the wrong drugs. In effect, more cost-effective medicines may be ranked lower in a formulary while less cost-effective drugs earn better slots. Somewhere between 600 and 1,000 P&T committees are making these kinds of decisions today.

The Current Process

To understand how all of this works, you first have to see the payer’s point of view. The fastest-growing costs in health care today are for specialty drugs. Take Sovaldi, launched by Gilead Sciences in late 2013 as a treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and recently superseded by Gilead’s newest drug, Harvoni.

Sovaldi represented a true medical breakthrough relative to previous HCV treatments — much shorter duration of therapy, dramatically reduced side effects, and very often a cure. But Sovaldi, Harvoni, and a raft of coming competitors also represent a staggering new economic reality. Sovaldi itself costs about $84,000. Harvoni costs $95,000 for 12 weeks of therapy (roughly equivalent to the cost of Sovaldi and the other drugs that must be taken with it), although Harvoni will cost $63,000 for patients who need only eight weeks of treatment.

In a July 2014 JAMA article, Troyen Brennan and William Shrank, respectively the chief medical and scientific officers at CVS Caremark, a major pharmacy benefit manager (PBM), estimated that with as many as 3 million eligible HCV patients in the U.S., “treatment of patients with HCV could add $200 to $300 per year to every insured American’s health insurance premium for each of the next 5 years.” Meanwhile, analysts’ predictions of total 2018 U.S. sales for Sovaldi, Harvoni, and their competitors cluster between $11 billion and $13 billion.

Sovaldi and Harvoni are just two examples of the explosion in spending on specialty drugs — 20% a year, according to the PBM Express Scripts. That is roughly four times the percentage rise in the cost of health care overall. Given current trends, specialty drugs will account for about half of the U.S. total drug bill within a few years.

That’s precisely why insurance companies and PBMs, largely at the behest of their employer customers, are narrowing their specialty-drug formularies. This practice encourages patients and physicians to choose from a more restricted list of options. And not all the choices are easy — a plan may no longer pay for, say, a rheumatoid arthritis medicine on which a patient is doing well, forcing her to self-experiment with the plan’s other (cheaper) preferred agents.

How to Crack Open the Box

Arguing that payers should not restrict drug formularies would be naive. As costs rise, there’s no other choice. But we contend that, as the stakes of these decisions grow, the transparency and the rigor of the decision-making process must increase proportionately.

To illustrate the problem, let’s start with an example from October 2013, when Express Scripts decided to exclude 46 drugs from its formulary. Several press reports noted that the PBM wouldn’t disclose its rationale, other than to say that its independent P&T committee had found that the excluded drugs offered no additional value over that of existing, lower-cost drugs.

It’s certainly reassuring when P&T committees are independent. But should patients, employers, and physicians simply trust that the independent decisions are medically and economically reasonable for all parties involved when the rationale isn’t published — and particularly when PBMs (and plans) make money through negotiated manufacturer rebates on the drugs they buy? Indeed, the average formulary decision-making process would hardly pass scientific muster. In one analysis, Gordon D. Schiff and colleagues noted that formulary decision making was “often subjective, unsystematic, and incomplete.”

What’s lacking is an evidence-based, systematic, transparent, and customizable approach to how formularies are developed. In effect, we need a database that assesses the value of each drug objectively, albeit from the payer’s point of view, and then allows a payer to make an appropriate choice for the specific population served. That’s no simple task.

An ideal, open-box solution would have four features:

It would incorporate a decision-making framework that accounts for the key criteria on which plans construct their formularies.

It would gather the data and source materials required for a decision.

It would systematically assess the drugs themselves, relative to their competitors, according to the evidence on clinical efficacy and economic impact.

It would do all of these things transparently, so that any interested party could check the logic and the details of each assessment.

The Challenges of an Open Box

The potential impediments here are many. The insurance-company pharmacists who prepare the materials for P&T committees might find their jobs threatened. PBMs and payers might not want their decisions to be second-guessed, particularly given that these often earnings-conscious companies have economic incentives for choosing particular drugs. And pharmaceutical companies might not like how an objective tool judges their drugs. In short, lots of stakeholders have a vested interest in keeping the process as it is: unsystematic, subjective, and opaque.

And yet plenty of other systems rate quality. Similar ratings-based approaches have been developed for physician and hospital performance and for selected high-cost medical services. Even the U.S. government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sponsors a website that compares hospitals and physicians on the basis of quality. And several clinical groups — most notably the American Society of Clinical Oncology — have talked about developing a scorecard that assesses the relative cost-effectiveness of competitive drug regimens, for use by physicians as they treat patients who are often overwhelmed by the cost of cancer care.

Decisions about which drugs to include in and exclude from formularies are part of a larger problem. As a society, we have decided not to allow doctors the freedom to practice medicine as they see fit — because we won’t pay for it. We outsource most of the decision making to insurance companies and PBMs. But we don’t require the decisions to be made transparently, systematically, and based on evidence — even though obscure economic incentives can influence, if not dictate, these institutional choices.

The time has come for us to demand that drug-formulary decisions be made using the best information available — and in broad daylight.

Bureaucracy Must Die

Almost 25 years ago in the pages of HBR, C.K. Prahalad and I urged managers to think in a different way about the building blocks of competitive success. We argued that a business should be seen as a portfolio of “core competencies” as well as a portfolio of products. By building and nurturing deep, hard-to-replicate skills, an organization could fatten margins and fuel growth. While I still believe that distinctive capabilities are essential to distinctive performance, I have increasingly come to believe (as I argued in an earlier post) that even the most competent organizations also suffer from a clutch of core incompetencies. Businesses are, on average, far less adaptable, innovative, and inspiring than they could be and, increasingly, must be.

Most of us grew up in and around organizations that fit a common template. Strategy gets set at the top. Power trickles down. Big leaders appoint little leaders. Individuals compete for promotion. Compensation correlates with rank. Tasks are assigned. Managers assess performance. Rules tightly circumscribe discretion. This is the recipe for “bureaucracy,” the 150-year old mashup of military command structures and industrial engineering that constitutes the operating system for virtually every large-scale organization on the planet. It is the unchallenged tenets of bureaucracy that disable our organizations—that make them inertial, incremental and uninspiring. To find a cure, we will have to reinvent the architecture and ideology of modern management — two topics that aren’t often discussed in boardrooms or business schools.

Architecture. Ask just about any anyone to draw a picture of their organization — be it a Catholic priest, a Google software engineer, a nurse in Britain’s National Health Service, a guard in Shanghai’s Hongkou Detention Center, or an account executive at Barclays Bank — and you’ll get the familiar rendering of lines-and-boxes. This isn’t a diagram of a network, a community, or an ecosystem — it’s the exoskeleton of bureaucracy; the pyramidal architecture of “command-and-control.” Based on the principles of unitary command and positional authority, it is simple, and scaleable. As one of humanity’s most enduring social structures, it is well-suited to a world in which change meanders rather than leaps. But in a hyperkinetic environment, it is a profound liability.

A formal hierarchy overweights experience and underweights new thinking, and in doing so perpetuates the past. It misallocates power, since promotions often go to the most politically astute rather than to the most prescient or productive. It discourages dissent and breeds sycophants. It makes it difficult for internal renegades to attract talent and cash, since resource allocation is controlled by executives whose emotional equity is invested in the past.

When the responsibility for setting strategy and direction is concentrated at the top of an organization, a few senior leaders become the gatekeepers of change. If they are unwilling to adapt and learn, the entire organization stalls. When a company misses the future, the fault invariably lies with a small cadre of seasoned executives who failed to write off their depreciating intellectual capital. As we learned with the Soviet Union, centralization is the enemy of resilience. You can’t endorse a top-down authority structure and be serious about enhancing adaptability, innovation, or engagement.

Ideology. Business people typically regard themselves as pragmatists, individuals who take pride in their commonsense utilitarianism. This is a conceit. Managers, no less than libertarians, feminists, environmental campaigners, and the devotees of Fox News, are shaped by their ideological biases. So what’s the ideology of bureaucrats? Controlism. Open any thesaurus and you’ll find that the primary synonym for the word “manage,” when used as verb, is “control.” “To manage” is “to control.”

Managers worship at the altar of conformance. That’s their calling—to ensure conformance to product specifications, work rules, deadlines, budgets, quality standards, and corporate policies. More than 60 years ago, Max Weber declared bureaucracy to be “the most rational known means of carrying out imperative control over human beings.” He was right. Bureaucracy is the technology of control. It is ideologically and practically opposed to disorder and irregularity. Problem is, in an age of discontinuity, it’s the irregular people with irregular ideas who create the irregular business models that generate the irregular returns.

In this environment, control is a necessary but far from sufficient prerequisite for success. Think of Intel and the extraordinary control it must exert over thousands of variables to produce its Haswell family of 14-nanometer processors. This operational triumph is tempered, though, by Intel’s failure to capitalize on the explosive growth of the market for mobile devices. More than 60% of the company’s revenue is still tied to personal computers, and less than 3% comes from the company’s unprofitable “Mobile & Communications” unit.

Unfettered controlism cripples organizational vitality. Adaptability, whether in the biological or commercial realm, requires experimentation—and experiments are more likely to go wrong than right—a scary reality for those charged with excising inefficiencies. Truly innovative ideas are, by definition, anomalous, and therefore likely to be viewed skeptically in a conformance-obsessed culture. Engagement is also negatively correlated with control. Shrink an individual’s scope of authority, and you shrink their incentive to dream, imagine and contribute. It’s absurd that an adult can make a decision to buy a $20,000 car, but at work can’t requisition a $200 office chair without the boss’s sign-off.

Make no mistake: control is important, as is alignment, discipline and accountability—but freedom is equally important. If an organization is going to outrun the future, individuals need the freedom to bend the rules, take risks, go around channels, launch experiments, and pursue their passions. Unfortunately, managers often see control and freedom as mutually exclusive—as ideological rivals like communism and capitalism, rather than as ideological complements like mercy and justice. As long as control is exalted at the expense of freedom, our organizations will remain incompetent at their core.

There’s no other way to put it: bureaucracy must die. We must find a way to reap the blessings of bureaucracy—precision, consistency, and predictability—while at the same time killing it. Bureaucracy, both architecturally and ideologically, is incompatible with the demands of the 21st century.

Some might argue that the biggest challenge facing contemporary business leaders is the undue prominence given to shareholder returns, or the fact that corporations have too long ignored their social responsibilities. These are indeed challenges, but they are neither as pervasive nor as problematic as the challenge of defeating bureaucracy.

First, only a minority of the world’s employees work in publicly-held corporations that are subject to the rigors and shortcomings of American-style capitalism. Bureaucracy, on the other hand, is universal.

Second, most progressive leaders, like Apple’s Tim Cook or HCL Technologies’ retired CEO Vineet Nayar, already understand that the first priority of a business is to do something truly amazing for customers, that shareholder returns are but one measure of success, that short-term ROI calculations can’t be used to as the sole justification for strategic investments, and that, since corporate freedoms are socially negotiated, businesses must be responsive to the broader needs of the societies in which they operate. All this is becoming canonical among enlightened executives. Yes, work still needs to be done to better align CEO compensation with long-term value creation, but that work is already well underway. And while some CEOs still grumble that Anglo-Saxon investors are inherently short-term in their outlook, their argument breaks down the moment you realize that investors often happily award a fast-growing company a price-earnings multiple that is many times the market average.

Simply put, at this point in business history, the pay-off from reforming capitalism, while substantial, pales in comparison to the gains that could be reaped from creating organizations that are as fully capable as the people who work within them.

I meet few executives around the world who are champions of bureaucracy, but neither do I meet many who are actively pursuing an alternative. For too long we’ve been fiddling at the margins. We’ve flattened corporate hierarchies, but haven’t eliminated them. We’ve eulogized empowerment, but haven’t distributed executive authority. We’ve encouraged employees to speak up, but haven’t allowed them to set strategy. We’ve been advocates for innovation, but haven’t systematically dismantled the barriers that keep it marginalized. We’ve talked (endlessly) about the need for change, but haven’t taught employees how to be internal activists. We’ve denounced bureaucracy, but haven’t dethroned it; and now we must.

We have to face the fact that any change program that doesn’t address the architectural rigidities and ideological prejudices of bureaucracy won’t, in fact, change much at all. We need to remind ourselves that bureaucracy was an invention, and that whatever replaces it will also be an invention—a cluster of radically new management principles and processes that will help us take advantage of scale without becoming sclerotic, that will maximize efficiency without suffocating innovation, that will boost discipline without extinguishing freedom. We can cure the core incompetencies of the corporation—but only with a bold and concerted effort to pull bureaucracy up by its roots.

This post is part of a series leading up to the 2014 Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 13-14 in Vienna, Austria. See the rest of the series here.

The Internet-Connected Engine Will Change Trucking

It’s happened to all of us. You’re driving down the road and the “check engine” light appears on your dashboard. It could be something simple, like time for an oil change, or it could be something bigger. What do you do? Lose your car for a day while you take it to a service station? Keep on driving and hope for the best?

If you’re a commercial truck driver, the stakes are higher. An unplanned repair visit means losing a day of revenue, and potentially hurting your delivery schedule, for a condition that might be very minor. But if you decide to keep driving, you risk something far worse happening to your engine – and your livelihood.

This kind of uncertainty is a fact of life for many drivers. But Daimler Trucks North America (DTNA) is using the Internet of Things to resolve the uncertainty. DTNA is the largest heavy-duty truck manufacturer in North America, selling trucks under brands such as Freightliner, Western Star, Thomas Built, and Detroit Diesel through more than 1,300 dealers. In 2013, the company released a service called Virtual Technician to help existing drivers while also enabling new business models and revenue streams. According to CIO Dieter Haban, whose team identified the idea and led product development, “the innovation combines telematics, mobility, central mission control, big data analytics, and a seamless process from the truck to the driver, fleet manager, and ultimately to an authorized service outlet.”

DTNA’s engines continuously record performance data and send it to their Detroit Diesel Customer Support Center (CSC). When a fault occurs, a team of CSC Technicians examine the data in real time and offer a recommendation. If it’s just a routine repair, technicians can help the driver schedule a service appointment for some convenient time and location. But if it’s a more severe condition, they might say “You need to bring your truck in for service right away. There’s a service station 75 miles down the road. When you get there, we’ll have a service bay open and all of the parts we need on hand. You should be in and out in two hours.”

This kind of service is more than just convenience. It brings certainty to a situation where uncertainty can drive tension into the driver/manufacturer relationship. By capturing information that formerly was available only from an in-person diagnostic test, Daimler Trucks North America creates customer loyalty and reduces risk for commercial drivers. It’s like driving a truck with a team of technicians on board.

Haban described the savings: “From the time a fault is realized, ordering parts, to getting the truck in the shop and repaired, we eliminated all wasteful steps. This cuts down the time tremendously.” But the savings go beyond efficiency. The service gives drivers confidence, and that’s important for a driver who operates alone, often hundreds of miles from home. Drivers are willing to pay for that certainty.

DTNA’s new service offers a number of important lessons for delivering IoT solutions, and digital transformation in general:

Look beyond the limits of the pre-digital age. Why is repair service so maddening? It’s because technicians can only diagnose and recommend services when your vehicle is actually in the shop. Daimler Trucks North America executives saw how IoT technology could fix this fundamental flaw in the design of the repair process, making the process smoother and more efficient for drivers and technicians alike.

Build and share a transformative vision. To the senior leadership team, this wasn’t just about telematics or new revenue. Putting a virtual technician on board each truck was just the start of a much broader process of changing the relationship between drivers or fleet operators and the company. DTNA leaders created this vision, communicated it widely inside the company, and then listened to ideas that could extend the vision.

Lead from the top. Digital transformation often crosses organizational silos, meeting many types of inertia and conflict along the way. It takes strong top-down leadership — a combination of persuasion, incentives, mandates, and examples — to make this kind of change happen. Virtual Technician touches many parts of DTNA, from IT to engineering to customer centers to dealers. Building the service required decisive leadership to invest in the innovation, negotiate across boundaries, address issues, and engage hundreds of people in making the vision real.

Ensure that you have a strong digital platform. DTNA executives had to build a platform that connected engines on the road, engineers and technicians in the control center, and systems in the dealers into a unified process. Failing to connect a link in the chain would lead to service failures and unwanted delays. For example, if dealer service systems were not part of the solution, a driver might arrive for service only to have to wait for a bay to open, or for parts to arrive. Building a platform that spans different organizational units, and even beyond the boundaries of DTNA, is challenging, but it is the foundation for everything else.

Foster close collaboration between IT and business leaders. In Daimler Trucks North America, the CIO is responsible for innovation, not just for IT. Business and IT leaders work closely together to identify and implement ideas. According to Haban, digital transformation is “a joint effort of IT and business. Nobody says ‘I’m the digital guy.’” This is important; neither IT nor business can do it alone.

Stay attuned to new possibilities. The Virtual Technician capability is becoming the centerpiece for new service offerings. For example, fleet managers are willing to pay for a service that lets them know, in real-time, where every truck is, how well it’s working, and when it will next need repairs. The data can also help DTNA understand how to improve its engines, help customers choose the right equipment configurations, or optimize inventory management. And management is paying attention to many other opportunities.

Looking forward:

To date, more than 100,000 trucks have activated the Virtual Technician service. More than 85% of users have already received a notification of needed services, and 98% were satisfied with the notification process. Customers report higher satisfaction and higher uptime on their vehicles equipped with Virtual Technician.

DTNA’s new capabilities make many other services possible for the company and its corporate family. Daimler could offer these services to commercial drivers and fleet managers in other parts of the world. It could extend its engine-focused service to other parts of the truck, like wheels or suspensions. And who knows — Mercedes drivers may someday get the same type of service for their passenger cars.

The internet of things is enabling new possibilities for digital transformation in every industry. It is creating new opportunities that were only dreams a decade ago. Take a look at your business. What can you do that you couldn’t do before? Start to do it now, before someone else does.

Divestment Alone Won’t Beat Climate Change

The fossil fuel divestment movement — an increasingly popular approach with environmentalists — primarily tries to convince pension funds, university endowments, and other asset holders that their investments in oil and coal are unethical because of impact of fossil fuel emissions on the world’s climate. Proponents argue that divestment is a symbolic statement that can discourage fossil fuel consumption by stigmatizing the industry. Despite its recent successes, we believe this approach is limited.

Both of us have done work on sustainable development and are keen to see a transition away from fossil fuels in order to limit climate change. But divestment alone is not the answer.

The key argument for fossil fuel divestment is that the cost of carbon dioxide emissions and other pollutants are not being accurately priced by the market. Divestment can theoretically address this market failure by limiting investment by the fossil fuel industry by depressing company valuations and thereby increasing the cost of capital. The economics of that argument are valid, but it remains uncertain how large the impact of divestment would be. For many companies, most of the capital expenditures are financed from internal cash flows and bank financing. Therefore, for major oil and gas firms and big coal companies, divestment looks like less of a constraint. (For smaller companies it could well prove to be a bigger one.)

Divestment also runs the risk of unintended consequences which could thwart environmentalists’ objectives. Markets have a fundamental correction mechanism for when a company’s valuation falls significantly below its cash flow generating capacity: at some point a buyer steps in, often from private markets. Private equity funds do this best, buying up cash rich companies that are undervalued by public markets. Were divestment ever to succeed in lowering the valuations of fossil fuel companies, an unintended consequence could be a shift from public markets to private markets, if carbon tax regulations are not enforced fast enough. Such a shift could hurt transparency; companies that go private have minimal reporting obligations and they typically become very opaque. This could limit everyone’s ability to engage the management of these companies in a discussion around climate change. In this case, divestment would clearly backfire.

Although divestment has sparked a needed debate, we feel it cannot exclude or replace parallel engagement efforts by shareholder and stakeholders.

Engagement calls for more transparency in the investment decisions of the fossil fuel industry. Shareholders could lobby management to consider climate impacts in all investment decisions, and push firms to avoid spending cash on high-cost, high-carbon capital expenditures. Instead, the firm could return the capital to shareholders as higher dividends or share buybacks, or diversify into other areas which might be less risky than fossil fuels.

If engagement works, then capital expenditures by fossil fuel firms are reduced, yielding lower carbon. Simultaneously, the risk profile of the company can be reduced and potentially share prices can even rise – a win-win.

The question is: will management be receptive to shareholders’ pleas? It is impossible to know, and may vary on a case-by-case basis. However, management should be willing to listen, since an engagement strategy zeroes in on the most carbon-intensive projects rather than seeking to devalue a company’s entire asset base (as divestment does).

None of this is to say divestment has no value. Right now, divestment is causing companies and investors alike to pay attention to the risks of climate change. In other words, if targeted engagement is the carrot, targeted divestment is the stick as the enforcement mechanism for those companies unwilling to engage. This mutually reinforcing process stands a better chance of reducing high cost new fossil fuel development than either approach on its own.

Fossil fuels will have to be part of the transition to a clean-energy future. Ultimately, the goal should be limiting new business development by fossil fuel companies. And rather than focusing only on ethics, the argument should focus on reducing risk to those companies themselves by pursuing a climate-secure global energy system.

Win Over the Person Blocking Your Deal

After two and half decades of doing deals in Silicon Valley I could write a dissertation on what I’ve discovered. Instead, I’ll posit one big, bedrock idea that eludes even the most seasoned of dealmakers: Success in deal making is not primarily about numbers or relationships or even timing. What matters most at the highest levels in business is the ability to leverage the dynamics of position.

When I was younger I spent a year as a professional poker player. After doing some statistical analysis of my playing, I realized that I made almost all of my money when playing hands “in position.” In other words, understanding where I sat at the deal table in relation to everyone else was the single most important factor in winning the game. Contrary to popular lore, being a winning poker player has little to do with bluffing or reading people or being a statistical wizard, and everything to do with maximizing the value of position.

In deal making the same thing holds true. Where someone sits within an organization determines both their underlying motivations and their risk profile — the two factors that determine whether they will say yes or no.

In a previous article, I wrote about the triangle of stakeholders: champions, decision makers, and blockers. Each of these individuals is uniquely positioned to influence a major deal and ultimately get it done or shut it down. In this piece, I’ll focus on the player in the triangle with the sharpest sword: the deal blocker.

There are numerous books, seminars, and courses on the subject of getting from “no” to “yes.” Whether the topic pertains to sales, diplomacy, or politics, the advice canon is vast. Yet there’s precious little available on the dissenter’s rationale. In order to turn deal blockers into advocates (or silent agnostics, worst case), we need to understand their motivations — and we do that by considering their position at the table. Blockers nix the deal because, from where they sit, it is in their best interest to do so. The job of the dealmaker is to turn that around.

What shapes the deal blocker’s motivation? In my experience, it comes down to three basic drivers: respect, advancement, and self-preservation.

Respect. For some blockers — I’ll call them experts – saying “no” is a simple matter of personal pride. They know far more about a specific domain (finance, technology, law) than you do and they want everyone to see that. Why? Because these blockers are less powerful then they are respected — and they want to maintain that high level of respect. This is why lawyers seldom recommend a deal. It’s not their job. Their job is to point out everything that could go wrong. Experts will parse your pitch with a magnifying glass, looking for flaws. And because of where they sit in an organization, experts are risk-averse. If a deal they support goes south they are an easy scapegoat because they don’t have a lot of political clout.

Winning over experts is a two-step process. First, you have to speak to them in language they understand (legal, technological, or what have you). Remember, these are not business owners, so presenting the corporate upside of what you are offering won’t help. What they care about is preserving the respect and trust of their colleagues, and that requires that they maintain a critical stance. In other words, you need to help the experts look smart. By simply showing them the respect they deserve, you are giving them part of what they need to get out of your way. Next, surround yourself with powerful internal and external supporters. Creating an environment where experts can safely jump on board, and insulating them from the side effects of failure, allows them to maintain their prestige and support the deal.

Advantage. Other blockers say “no” to the deal because it’s actually to their advantage to knock it down.

One such blocker—the competitor—is the champion of a competing idea or solution. From where they sit, competitors can enhance their own prospects by using your deal to make theirs look like a better alternative. Competitors are open to risk because they are willing to raise the stakes to ensure their own success. The best way to encourage competitors to support you is by forming an alliance that will help them close their deal. Perhaps your deal will create a market for theirs or serve as a test case? Your deal will look good to competitors if they can tether their success to yours. If that doesn’t work your only option is to isolate that person so his/her opinion doesn’t have the necessary gravitas to block you.

A similar breed of blocker, the doubter, doesn’t ever really say “no” to the deal—but he won’t support it either. Since he has nothing specific to gain by saying yes (he isn’t the champion), he plays devil’s advocate. Why? Because if the deal goes bad, it’s safer on the sidelines. In reality, many doubters are looking for a reason to get in the game and say yes. They want to be a champion. They key to converting doubters, then, is to offer them enough upside to coax them out of the shadows. This can be in the form of a promise to include them on the team, have them speak at an event, introduce them to an industry luminary, or whatever that person might value.

Self-preservation. The next type of blocker, the traditionalist, is someone who’s always done something a particular way. Traditionalists rely heavily on precedent. It’s how they’ve made their mark in the organization — with a one specific process, technology, or incumbent account. By saying yes to something new, the traditionalist is putting his old-line position in jeopardy. Traditionalists are risk-averse because their livelihood depends on it.

The wholesale adoption of “cloud” computing is one example. There are huge numbers of people who have built their careers installing and maintaining software and systems. With cloud computing 90% of that disappears. What happens to the traditionalists who spent 20 years overseeing the last generation of technology? They either get on board or they disappear. The best way to get this type of blocker on your side, then, is to make change seem inevitable. As much as traditionalists fear change, they are more afraid of missing out or being left behind. Bringing the traditionalist on-board gives him hope that he can transition his domain into the inevitable new normal.

The reality is that all blockers say no (or yes) because it is in their best interest to do so. And their motivations, like your own, are dictated by their position around the deal table. By leveraging that, you can neutralize their concern in a way that allows them to either benefit from the deal or get out of the way with their credibility intact. This understanding, in deal making as well as poker, is what separates the professionals from the amateurs.

The Fortune Global 500 Isn’t All That Global

The 2014 DHL Global Connectedness Index that one of us (Ghemawat) prepares with Steven Altman, and that was released on November 3, indicates that global connectedness started to deepen again in 2013 after its recovery stalled in 2012. In other words, there’s now a higher volume of information, capital, people, and trade flows between countries.

But even more striking are the report’s findings concerning the breadth of connectedness –how widely distributed those flows are between different nations. Emerging economies are reshaping global connectedness and are now involved in the majority of international interactions. But advanced economies, in particular, have not kept up with the big shift of economic activity to emerging economies, leading to declines in the breadth of globalization.

Do we see similar patterns when we look at company level—and particularly at multinationals that operate in multiple countries? Specifically, are companies from advanced economies failing to keep up with the big shift? There are indeed some indications that point in this direction. Thus, analysis of a sample of companies by McKinsey indicates that over 1999 to 2008, companies from emerging economies not only grew 10 percentage points faster annually at home than companies from developed economies (18 percent vs. 8 percent), but also enjoyed a similar edge (22 percent vs. 12 percent) in advanced economies, and an even bigger one in other (foreign) emerging economies (31 percent vs. 13 percent). And Bain & Company’s analysis of the performance of nearly 100 Western firms with listed subsidiaries in emerging markets found that these companies increased their profits there by an average of 15 percent a year between 2005 and 2010—compared to 23 percent a year for comparable local companies.

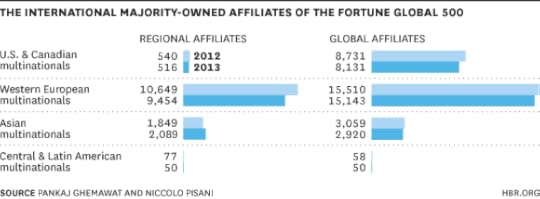

Unfortunately, these data start before or even end with the financial crisis, and the sample selection criteria are not entirely clear. To address the extent of globalization at the company level and provide a firm-level counterpart to the country-level analysis presented in the Global Connectedness Index, we looked at the world’s 500 largest companies, as in companies included in the Fortune Global 500 in 2012 and 2013, and collected data on all their majority-owned affiliates—both national and international (over 75,000 in 2012 and 71,000 in 2013). While this metric has its own limitations—among other things, it reflects choices about internal organization and is likely to change very slowly–it does allow us to be systematic as well as relatively up-to-date.

The data indicate that even the Fortune Global 500 continue to locate nearly one-half of their affiliates at home: Europe was actually the only region in which, overall, more than one-half—about 70%–of companies’ affiliates were international. And while there was, given the numbers reported above, a general tendency toward reducing the total number of affiliates in the 429 companies that were on the list in both 2012 and 2013, the number of international affiliates dropped a bit faster than domestic ones.

The most pronounced differences, however, are at the level of the three major world regions to which most of the Fortune Global 500 can be assigned: the triad of US/Canada, Europe, and Asia. Asian multinationals are the only ones that increased the number of international affiliates between 2012 and 2013, and they chose to reinforce their regional presence rather than their presence elsewhere. This pattern dovetails with the declining distance (and increasing regionalization) observed at the country-level in East Asia & Pacific in the DHL Global Connectedness Index. (South and Central Asian, broken out separately in that report, ranks much lower on both internationalization and regionalization levels.)

European multinationals have the highest proportion of both regional and global (outside-the-region) affiliates within the triad—in keeping with the characterization in the DHL Global Connectedness Index of Europe as both the world’s most internally integrated and globally connected region. Between 2012 and 2013, these companies reduced their international affiliates within Europe particularly rapidly, as one might expect given anemic European growth and forecasts for growth. The cut-backs in their global affiliates, in contrast, were significantly more modest than in the other two regions.

US/Canada consists of just two countries, so as one might expect, companies headquartered in this region have relatively few regional affiliates: global affiliates are more than 15 times as numerous. These companies cut back their numbers of global affiliates to a significantly greater extent than their Asian and European counterparts—which jibes with casual impressions that there is significantly more skepticism about global expansion in the C-Suite in the U.S. (which dominates this region) than elsewhere.

Of course, as is often the case, these averages, mask significant variation: thus 18% of the firms that figured on the Fortune Global 500 lists in both 2012 and 2013 actually increased the percentage of their total affiliates that are international by more than 5 percentage points, versus 13% that registered decreases of 5 percentage points or more. And in the aggregate, the changes reported are relatively small, as one might expect: affiliates aren’t started or stopped on a dime. But they do fit with the pattern of changes observed for the Fortune Global 500 companies between 2011 and 2012 and with the pattern of declining breadth observed at the country level by the 2014 DHL Global Connectedness Index. Perhaps these cutbacks are a response to overshooting earlier on because of “globaloney.” But whatever the explanation, at least some companies—even among the world’s largest—seem to think that globalization has run its course, at least as far as they are concerned.

When Stock Buybacks Are Not a Waste of Money

Buying back stock, pretty much corporate America’s favorite thing to do with its money over the past decade, has come in for a lot of criticism this fall. In an epic September 2014 HBR article, “Profits Without Prosperity,” economist William Lazonick blamed buybacks for much of what ails the U.S. economy. His arguments have begun to catch on, in the media at least.

Two years ago, though, HBR Press published a book that cast buybacks in a much different light. In The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success, Will Thorndike described how share buybacks had helped drive several of the most remarkable corporate successes of the past half century. The Outsiders has been described by The Wall Street Journal as the “playbook” for many of the activist investors currently pushing companies to buy back more shares.

So I asked Thorndike, a managing director at the private equity firm Housatonic Partners, what gives: Are buybacks a travesty, or smart capital allocation? What follows is an edited and condensed version of our conversation. But first, I should probably define a few things that come up: A tender offer is when a company publicly offers to buy a large number of shares, at a set price, over a limited time period. P/E means price-to-earnings ratio. And John Malone is a cable-TV billionaire who figures prominently in Thorndike’s book.

I guess I’ll start where your book starts, with Henry Singleton, who is really the father of the modern stock buyback. What did he do?

The way to think about Henry Singleton is that he demonstrated kind of unique range as a capital allocator. He built Teledyne [in the 1960s] largely by using his very high P/E to acquire a wide range of businesses. He bought 130 companies, all but two of them in stock deals. Throughout that decade his stock traded at an average P/E north of 20, and he was buying businesses at a typical P/E of 12. So it was a highly accretive activity for his shareholders.

That was Phase One. Then he abruptly stops acquiring when the P/E on his stock falls at the very end of the decade, 1969, and focuses on optimizing operations. He pokes his head up in the early ‘70s and all of a sudden his stock is trading in the mid single digits on a P/E basis, and he begins a series of significant stock repurchases. Starting in ‘72, going to ’84, across eight significant tender offers, he buys in 90% of his shares. So he’s sort of the unparalleled repurchase champion.

When he started doing that in ‘72, and across that entire period, buybacks were very unconventional. They were viewed by Wall Street as a sign of weakness. Singleton sort of resolutely ignored the conventional wisdom and the related noise from the media and the sell side. He was an aggressive issuer when his stock was highly priced, and an aggressive purchaser when it was priced at a discount to the market.

The other seven companies in the book, buybacks were a big part of their success too, right?

Yes, that’s correct. Of the eight companies in the book, all but Berkshire Hathaway — kind of a special case, Warren Buffett’s company — bought in 30% or more of shares outstanding over the course of the CEO’s tenure.

Is part of it the era? Most of these stories you tell, the bear market of the ‘70s and early ‘80s is right in the middle of them.

There’s definitely some meaningful overlap across that group in terms of their tenures. But John Malone’s buyback activity is just extraordinary over the last five to eight years. And Buffett has signaled for the first time ever that he’s a buyer. He’s gone from a non-active buyback CEO to one who has changed his approach and gotten very specific about it for the first time, which is interesting.

So in the 1970s, when Henry Singleton and some of these others were getting into buybacks, it was seen as weird, a sign of weakness. Now I think we’re going through the greatest buyback wave ever. Is that good news for investors?

Corporate America’s track record buying in stock is just horrendous. It’s terrible. We are now again approaching a peak of buyback activity, no matter how you measure it. The prior peak occurred in the second half of 2007, the last market peak. The trough in corporate buyback activity? Early ’09. So, kind of a perfect contra-indicator for the stock market.

Not surprisingly, many studies have shown that buybacks don’t produce great returns. But there are very different approaches to buybacks, and they produce very different outcomes. The typical way that corporate America implements a buyback is the board announces an authorization, which is usually equal to a relatively small percentage of market cap — low to mid single digits — and they then proceed to implement that authorization by buying in a specific amount of stock every quarter. Sort of a metronome-like pattern. And generally the amount of stock they repurchase is designed to offset options grants.

The approach of the CEOs in the book was entirely different. It was pioneered by Singleton, and it involved very sporadic, sizable repurchases. I mentioned that Singleton bought in those 90% of shares over eight tender offers. The largest was the last one, which he did in 1984. He bought in 40% of shares outstanding. He tendered for 20-25% and there was excess demand, so he bought in all the shares [that were offered to him].

It’s very different mindset. You’re looking at a stock repurchase as an investment decision with a return and you’re comparing that return to other alternatives, and when it’s attractive you’re aggressive in implementing it.

With Carl Icahn and Apple, Icahn’s argument is, “Do a tender offer, because the stock is relatively cheap compared to where I think it’s headed.”

That’s exactly right. It’s very interesting to see, [because] tenders are rare these days. Even Malone, he’s used tenders occasionally, but he’s generally doing open-market purchases. But you can still implement that sporadic, large-purchase approach in the open market. It’s just you don’t see it that often.

I think the world divides into people who are serious about repurchases and those who are doing it for more cosmetic reasons. You could look at a list of companies who’ve bought in some minimum threshold of shares over the last 24 months, and that’s a group who’s going to have a very different philosophy in this area than the broader market.

So the way to tell buybacks done as capital allocation from buybacks that are done because everybody’s doing buybacks is the size and also the sporadic nature?

It’s the size, it’s the sporadic nature, and also it’s just, how does management talk about buybacks? Are they describing them as attractive investments in their own right? That’s the key, I think. Not as simply another channel for “returning capital to shareholders,” which seems to be the phrasing du jour.

How to Motivate Someone You Don’t Like

The odds are pretty low that you’ll like everyone you have to manage. And while you may think that disliking an employee or two isn’t something to be concerned about (after all, making friends isn’t the point of being a manager), it can actually interfere with your job. A caring manager is key to employee engagement. When you have negative feelings toward an employee, chances are that person will feel less motivated. That disengagement can, in turn, affect your entire team and the outcome of important projects – which ultimately reflects badly upon you.

In my experience, it’s almost impossible for managers to motivate people they don’t like (except perhaps with fear, which is not ideal). So, for the sake of employee engagement — and your own mental health – it’s important to invest some energy in learning to like at least something about each of your direct reports.

Before you even try to motivate a person you don’t like, take ownership of your feelings and assumptions. If the phrase “He makes me so angry” or “She drives me nuts” ever plays in your head, you need to change your thinking. Recognize that anger, frustration, or mistrust is your reaction and that no one has the ability to make you feel something without your consent. Be curious about why you react the way you do and see if you can get to the root of the issue. You need to own your dislike; your team member does not.

Once you have a sense of what behaviors or characteristics you’re reacting to, employ one or more of the strategies below:

1. If you feel uncomfortable around an employee, increase your time together. It may sound like counterintuitive advice, but if you feel awkward, frustrated, or angry around one of your employees, you probably try to avoid her and may even struggle to make eye contact when you’re together. Imagine how demoralizing it can be for the employee whose boss won’t even look her in the eye!

To change the dynamic, you need to actually create more opportunities to be together, so you can get to know the person’s back-story. This will have two benefits: First, you’ll get used to her quirks, which will make you more comfortable with them. Second, you’ll learn about what makes her tick and how you can tap into those values as a source of motivation. Try opening up a conversation by saying, “You and I haven’t had much of an opportunity to get to know one another. What are the most important things to know about you?”

2. If you find an employee’s habits annoying, focus on the positive. Constantly focusing on what you want the person to change can really be a downer (for both of you). Instead, redirect your attention to what you do like and respect about the person. Think about one trait or habit that impresses you—even if it’s a strength that is sometimes over-applied. Does the person plan diligently? Is he a fan favorite among customers? Does he bring attention to the risks inherent in your strategies? Pay more attention to the positive contributions that you want to encourage. The employee will be motivated by hearing how the team is counting on his strengths to be successful.

Imagine a sales associate who is being pushy with clients. If you reframe the pushiness as persistence, you can encourage that behavior while opening up a conversation about when it’s appropriate to back off. You could say something like “I’ve been watching you on the floor today and you are really giving it your all. I admire your persistence. At the same time, I’ve noticed that it doesn’t seem to work with everyone; when do you think it might be best not to approach someone a second time?”

3. If you think your employee acts disrespectfully, get to the root of the behavior. If the source of your dislike for an employee is bad behavior, (e.g., bullying, self-promotion, disrespect) you won’t be able to motivate the person unless you have some empathy. Most bad behavior is not intentionally destructive; it’s self-protective. Figure out what the person is trying to protect. Does he have fragile self-esteem? Is she worried about something? Dig deep. Ask open-ended questions such as “What’s going on for you?” or “What did this discussion trigger?” or “What are you concerned about?”

When you figure out what’s beneath the behavior, you’ll have a better sense of how to motivate good behavior. For example, if you uncover a self-esteem issue, you might determine that an employee needs more opportunities in the spotlight, or that another might be more motivated by small, manageable assignments that allow room for growth without taking undue risk.

Regardless of the source of your dislike for an employee, motivating him or her will be very difficult until you can improve the connection. If you want to be direct about it, you can express your desire to improve the relationship with a statement such as, “I feel like we got off to a bad start and I’d like to change that.” If you want to be more subtle about it, you can signal that you are open to changing your relationship by slowly including the person in more activities, using her as a positive example when talking to the whole team, or just by using your eye contact and body language to be more inclusive.

It’s not your job as a manager to be everyone’s friend. But if a sour relationship is affecting your ability to motivate an employee, the risk is that he will fail, and so will you. Take ownership of your relationships with your direct reports and make the small changes that will help you reframe how you think about them. Even if you don’t end up becoming friendly, your relationship will at least be strong enough to keep the other person motivated.

November 3, 2014

7 Marketing Technologies Every Company Must Use

With over 1,000 companies trying to sell some type of marketing technology in over 40 categories, it’s not surprising that the most common word that marketers use to describe themselves is “overwhelmed.” Indeed, according to my research into 351 mid-market B2B companies, except for companies in software, the adoption rate of marketing technology is very low: companies in other industries are using a median of just 2 out of 9 major marketing technology programs that I identified.

This is a wasted opportunity. Many marketers have reported rapid and significant ROI from adopting these tools; but first, they had to convince higher-ups to make the up-front investment. So, in the interest of helping clear that path, I am suggesting a Marketing Technology Starter Kit: the seven programs that every company’s marketing team should have access to, at a minimum, to grow leads, opportunities, and revenue.

These programs are essentially an online form of direct marketing. Traditionally the two most important factors in the success of direct marketing campaigns have been the list — getting the materials in front of the right audience — and the offer – offering them something that they will value and act on. And direct marketers have been measuring and optimizing to improve results for decades, in a way that even David Ogilvy admired. In my Starter Kit you’ll see repeatedly how marketing technologies help you get in front of the right audience at the right time with the right offer.

Here’s my list of seven technologies that are table stakes for today’s marketer:

Analytics: Marketing is at an inflection point where the performance of channels, technologies, ads, offers – everything — are trackable like never before. Over a century ago retail and advertising pioneer John Wanamaker said, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.” Today smart marketers do know which half isn’t working. But to do that you need to have web analytics programs set up, and have people on the marketing team who know how to use data.

Leading tools:

Far and away the most popular website analytics tool is the free Google Analytics, which is used on over 80% of small and mid-market websites. It’s definitely the place to start; at some point you may find a need for the paid version or other enterprise analytics tools such as Adobe Analytics. Note that the tools below also have their own analytics platforms.

Conversion Optimization: Conversion optimization is the practice of getting people who come to your website (or wherever you are engaging with them) to do what you want them to do as much as possible, and usually that involves filling out a form so that at the very least you have their email address. Typically only about 3% of people coming from an online ad will fill out a website form; with conversion optimization that can be doubled to roughly 6%. With outstanding offers or marketing apps some companies have created conversion rates several times higher than that; I have a form on my website with a 33% conversion rate. If you’re going to go to the effort and expense of getting people to your website, you need to get as many of them as possible to convert.

Leading tools:

Wordstream’s free Landing Page Grader

Optimzely lets you run A/B tests on landing pages and other website elements

With Unbounce you can create and A/B test landing pages

ion interactive provides tools for non-programmers to create marketing apps, which may provide higher levels of engagement and conversion than a form or content download

Email: Email marketing is the 800-pound gorilla of digital marketing. And I’m not talking about spamming people by buying lists that are being sold to your competitors, too. I’m talking about getting people to give you permission to email them additional information, and then sending only valuable content tailored to the person’s interests. It takes more than one touch to close a sale; email marketing is so powerful because you’re staying in front of customers and prospects who have said that they want to hear from you.

Leading Tools:

MailChimp

Constant Contact

Marketing automation programs (see below) usually have robust email marketing capabilities built in

Search Engine Marketing: Search Engine Marketing includes both paid search ads, like Google AdWords, and search engine optimization (SEO) to try to get high organic search listings for your website content. Since most people, even B2B buyers of big ticket items, use search as part of their work, you need to be there when these people are searching for what you’re selling. With search ads you can test and optimize on keywords, ad copy, offers, the website forms you take them to, and more, and track the people downstream if you integrate your Google AdWords data with your Google Analytics data and CRM so that you know not just which ads are clicked on the most but which ads lead to the most opportunities and revenue. These insights can be applied to all of your online and traditional marketing. SEO involves not just technical enhancements to the site but, most importantly, regularly creating high quality content, which is what Google really values and ranks highly.

Leading Tools:

Google AdWords

Bing and Yahoo

WordStream

Wordtracker

BrightEdge

Remarketing: You’ve experienced remarketing: it’s when you go to a website and then, when you leave that site, their ads appear on other sites that you visit. It’s really easy to set up and incredibly cost effective because you’re only advertising to people who have already expressed enough interest in you to come to your site. It can even be customized to show ads for the particular products or services they looked at. And since you usually pay on a CPM basis, you get tons of free impressions. Over 50% of software companies use remarketing, but less than 10% of other companies do; follow the lead of those software companies.

Leading Tools:

Google AdWords remarketing

AdRoll

Perfect Audience (from Marin Software)

Mobile: Half of emails are now opened on smartphones, and soon half of search will be done on smartphones, so all websites need to be mobile friendly. But today, less than a third of them are. Simply put, you need to have a site that is easy to read and use on a phone. If you don’t, Google penalizes you with lower mobile search rankings. So that mobile-friendly site is step one; after setting up a mobile-friendly website you can go on to mobile search advertising and other forms of mobile marketing. But this is, after all, just a starter kit.

Leading Tools:

The most common technique for making a mobile-ready website is to use responsive design, which automatically resizes the website to fit the device on which it’s being viewed. You can usually tell that a site is responsive by resizing your desktop browser from a horizontal to a smaller, vertical (smartphone-like) size and seeing if the site automatically reconfigures itself, as the mayoclinic.org site does. The other major approach is to create and maintain a separate mobile site such as the New York Times does at mobile.nytimes.com; smartphones are automatically directed to that site.

Marketing Automation: Marketing automation brings it all together. It is a terrific technology that includes analytics, online forms, tracking what people do when they come to your website, personalizing website content, managing email campaigns, facilitating the alignment of sales and marketing through lead scoring and automated alerts to sales people, informing these activities with data from your CRM and third party sources, and more. There isn’t enough room to go into more detail here; just get it.

Leading marketing automation programs for small businesses and mid-market companies:

HubSpot

Act-On

InfusionSoft

Leading programs for mid-market and enterprise:

Marketo

Adobe Campaign

Oracle Eloqua

Pardot and ExactTarget (Salesforce)

Silverpop (IBM)

You may have noticed that I mentioned “content” several times while describing the implementation of these programs. Content is the currency of modern marketers, including in B2B when it is ideally tailored to the different members of the buying team and stages of the buying cycle. Content can take many forms including blog posts, webinars, infographics, marketing apps, and videos as well as traditional forms such as events. And the quality of content is key; as MarketingProfs Chief Content Officer Ann Handley asks, “Would your customer thank you for that content?” So high quality, creative content is critical, but it’s not a technology.

And, no, I didn’t forget social media. Social media is important for engagement, for promoting content, and for other purposes, but I don’t put it in my top seven when it comes to lead generation.

While I have described these seven separately, they are in fact synergistic. Search ads by themselves don’t do nearly as much as search ads with great website conversion forms, remarketing, automated email follow up, and all tracked in a marketing automation system and integrated with your CRM. So it can be complicated. Like sales and product development and supply chain management and finance and any other important part of the company, it ultimately comes down to not just what you do but how well you do it. There are no silver bullets, and it’s a poor marketer who blames their tools. If you’re new to digital marketing, you’ll need to work with people who have a holistic view of marketing technology and don’t just want to steer you toward the one or two that they support.

How to Participate in Your Employee’s Coaching

Once upon a time, executive coaching was viewed as a remedial intervention for executives and managers who needed to be “fixed” in some way. Managers were not expected to be particularly involved in the coachee’s exploration or journey. Coaching was even sometimes viewed as “outsourcing” the management of a difficult employee.

But today, executive coaching is often viewed as a strategic investment in human capital – a perk reserved for employees with high potential — and managers have realized that they need to participate in the process. If you are a manager with a direct report who is working with an external coach, there are several things you can do at the beginning of a coaching engagement to help make it successful:

Set broad objectives and frame them positively. At the outset, the more specific you can be about how you define success for the participant, the better. But when you do so, be sure to emphasize professional development goals. So, for example, your objective might be that the individual should “advocate more persuasively for resources, information, and support” by “navigating organizational politics and priorities more effectively” instead of telling your staffer that he or she “needs to fix contentious relationships” with others. Or you might suggest that he or she “manage workload, expectations, and deadlines more effectively” instead of telling them they need to stop over-promising and under-delivering.

Provide data. Coaching is most effective when the participant and the coach have multiple sources of information, which might include past reviews, personality assessment reports, or online or interview-based 360 degree feedback. While the employee may already have this information, it’s often helpful for you to share what you have in your files directly with the coach. If the coach will be conducting 360 degree feedback interviews, you can make sure that he or she speaks with a representative sample of colleagues for the participant, who can provide a broad, not biased, perspective.

Be specific about concrete action steps the employee can take. A good coaching engagement can go to waste if the manager, the coach, and the employee haven’t clearly articulated specific things the employee can do differently or better.

For instance, the head of a division in a pharmaceutical company had a staff member with a reputation for being brilliant but over-committed. When the coach sat down with the manager to define goals for the coaching, the manager was able to articulate two clear prescriptions for the direct report who was working with the coach: 1) Respond to everyone within 24 hours, even if the response was just a simple reply to set expectations about when a full answer to the voicemail or email would be forthcoming and 2) Create a “not to do” list of tasks that the participant would either not take on or would delegate to others. These two prescriptions, which the coaching participant put into practice, helped him satisfy his stakeholders while simultaneously prioritizing more effectively and focusing on his highest value-adding activities.

Define clear parameters on confidentiality. A coach is not acting as a psychologist, and different confidentiality rules apply. On the one hand, there should be confidential aspects of the process, such as the feedback the coach collects on behalf of the participant (otherwise, feedback providers might hold back in their comments due to concerns that their input may have implications for how higher-ups, or Human Resources, evaluate the employee). You can also understand that your direct report might not want to share all of his or her personality assessment reports, or the 360-degree interview feedback that is collected, with you.

On the other hand, coaching is an investment by you and the organization in the development of your subordinate, so there needs to be accountability built in to the process. Therefore, while assessment data should remain confidential, the development plan based on the data should be shared with you, and possibly also with your Human Resource Business Partner or Leadership Development counterpart.

Be blunt with the coach – blunter than you would be with the coachee. While a coach should not become a messenger between you and your staff member, there is an opportunity in the context of executive coaching for you to provide more specific and candid feedback to the coach than you might feel comfortable delivering face-to-face with your employee.

For example, the manager of a talented investor relations executive at a financial services organization told the employee’s coach that he hadn’t been promoted in the last cycle because the executive was viewed as too self-promotional and political. The manager had been reluctant to share her perspective directly with the executive because she was concerned that he wouldn’t find the feedback credible, coming only from her. However, since other feedback providers in the 360 process shared that same observation, and the coach was viewed by the participant as a neutral and supportive outsider, the coaching participant was able to hear the feedback in a way he wouldn’t have had it been provided directly by his manager. The participant got the message when positively communicated by the coach, became more collaborative and supportive of his colleagues, put the firm’s interests above his own, and was promoted the following year. This happy ending was only possible because the manager had been an active sponsor of, and participant in, the coaching – and had been honest with his coach.

By carefully considering your role in the executive coaching of your direct reports, you can help retain talented members of your team while helping them learn and grow as managers, leaders and teammates, and supporting them as they take their performance up to the next level. Your direct reports will progress further and better on their coaching path if you help show them where it is and where it leads, and then provide direction and support along the way.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers