Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1343

November 13, 2014

An Easy Way to Make Your Employees Happier

November 12, 2014

To Motivate Employees, Help Them Do Their Jobs Better

Why Citi Got Rid of Assigned Desks

It may seem odd to use a dystopian world as a model for an office workspace, but that’s just what Citi did.

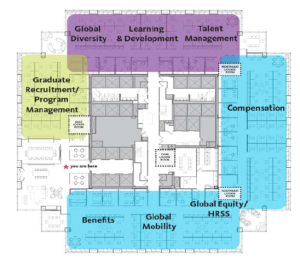

Susan Catalano, Citi’s Managing Director and Chief Operating Officer of HR, was reading the Divergent series — about a future society broken up into five social factions cultivating different virtues — around the same time she was asked to assist with an open floor plan for the HR group’s new workspace and the book influenced the end product. “We created what we call neighborhoods — a compensation neighborhood, a learning and development neighborhood, etc. — to help individuals feel they ‘owned’ their space, even though no one has a designated workspace and no one has a private office,” she explains.

Workspace is an emerging dimension of what the Families and Work Institute has identified as an effective workplace. The physical environment, if done right, can foster elements of an effective workplace like collaboration and autonomy, work-life fit and opportunities for learning. However, as many of the articles in the special section on office space in the October issue of HBR makes clear, this is easier said than done.

The issues that Catalano and her team faced in designing the new space ranged from minor — Where do employees put their personal items such as knapsacks or handbags? How do we stop people from speaking too loudly? to major — How can we be open and collaborative if people are separated by specialties?

The space is a pilot in an initiative called CitiWorks, which is meant to optimize the company’s workspaces. It addressed two problems. First, people had been scattered in different offices throughout the metropolitan area, creating a fractured feeling. Second, an internal study showed that some offices, like most workplaces, were underutilized because of travel, vacation, illness and flexible working arrangements.

The end result for the HR team is a consolidated space in Long Island City — an entire floor that overlooks New York City. The periphery of the space includes rows of workstations, each with large double-screened computers. In the center of the spaces are larger conference rooms, smaller meeting rooms, and private spaces for focused work. There are cozy seating areas scattered throughout the space as well as areas where people can meet or have lunch together.

The design intends for no one to have an assigned desk and there are only 150 spaces for 200 people. For those who were initially resistant to losing their assigned space, Catalano says, “it was hard to argue with real data that the old space was underutilized.” Employees have a locker where they put their personal belongings, and then they set up in the morning where they want to work. There are sanitized wipes on every desk so that the shared workstations are left clean. The entire space is “green” so the window shades, lights and temperature are programmed to respond to usage and conditions, such as the amount of sunlight streaming into the space.

Despite the beautiful space, old habits die hard. Karyn Likerman, Head of Inclusion Programs and Work-Life Strategies, admits, “Even though the space is completely unassigned seating, I typically sit in the same place each day and so do most of my colleagues.”

The color-coded “neighborhoods” are in smaller sections of the larger space, enabling a sense of belonging, and also fostering a healthy sense of identity.

One of the biggest benefits of the more-open space is innovation. People talk to others whom they might not have known before and as a result, are coming up with new ideas. Likerman relays one example:

We have a new colleague, who came in thinking his job would be mostly focused on affirmative action reporting and auditing. A conversation with someone who sits on the other side of the floor in recruiting got him thinking about how to involve our employee networks in diversity recruiting. After that conversation, he rolled his chair over to me, since I oversee our networks and we came up with a new, innovative, and more formal recruiting approach to expand the network’s involvement.

Other benefits include a greater sense of fun and camaraderie. Now more people eat lunch together, instead of alone at their desks. The office neighborhoods have started planning fun, informal events — breakfasts or Friday afternoon mixers. “Many of these are people I have worked with for years but I never met them in person. Now, we get a chance to connect on a more personal level, and it’s fun,” says Likerman. And the smaller footprint has saved millions of dollars in Citi’s HR budget.

To be clear, the new space alone didn’t create these results. The workspace has to be carefully managed — as does the transition to it. Here are some of the lessons learned from Citi’s experience:

Use technology that supports the space. Among the most important features is a white noise machine that evens out the sounds so that the workspace is quiet enough for people to be able to concentrate. In addition, everyone is given headsets to allow for hands-free talking. When employees log in to their computers, their desktops and phone numbers follow them.

Create new norms. Susan Catalano and the CitiWorks team are working on a playbook that lays out guidelines for how to best work in the new space. At the same time, they know that the playbook will evolve and change, as people get used to the space.

Allow people to personalize. When groups wanted to personalize their neighborhoods, Catalano didn’t stand in their way. One neighborhood showcases a collection of snow globes that an employee has gathered from colleagues’ travels. The Diversity team displays the awards Citi has received, which is a great source of pride for the group.

Emphasize problem solving. When issues arise, Catalano emphasizes that everyone, not just leaders, are involved in addressing the kinks. For example, Likerman says that people used to call or email each other even if their offices were next door. Now they simply turn around and talk. Despite the white noise machines, booming voices can sometimes cause problems. “We need to enable people to feel comfortable to remind others that they are speaking too loudly,” she says.

While neighborhoods have helped the HR group, the new setup is a work in progress. Catalano and her team remain focused on creating neighborhoods that give different groups a sense of belonging while ensuring they don’t inhibit a fully open and collaborative workspace. “I think,” Catalano surmises, “over time people will continue to come together as the neighborhood lines blur.”

November 11, 2014

Setting the Record Straight on Job Interviews

You scored a job interview, and now it’s time to get ready. Before you start prepping, you have to consider whose advice to take. Should you believe your colleague when she says that you have to wear a suit even though you’re interviewing at a tech start-up? Or do you trust your friend who says, “Just be yourself”? There’s so much conflicting advice out there, it can be hard to decide on the best approach for you. So we asked readers (and our own editors) what advice they hear most often and then talked with two experts to get their perspectives on whether the conventional wisdom holds up in practice and against research.

1. “Always wear a suit.”

“In some ways, Britain is more formal but this advice has gone out the window even in the UK,” says John Lees, a UK-based career strategist and author of How to Get the Job You Love and Job Interviews: Top Answers to Tough Questions. Wearing a suit when everyone at the office is dressed more casually sends the message: I don’t understand your culture. This is especially true in laid-back Silicon Valley, says John Sullivan, an HR expert, professor of management at San Francisco State University, and author of 1000 Ways to Recruit Top Talent. “If you go to an interview at Facebook in a suit, you’re going to look like an idiot,” he says.

You want to overdress but only by a little. “Wear one or two notches smarter than what people wear in the office,” says Lees. It’s much easier now than it’s ever been to find out how formal or informal an office is. Go to the company’s website. Look on glassdoor.com or vault.com. Sullivan says you can even go as far as calling the receptionist or an intern and asking how people dress. “If necessary, bring an extra set of clothes and then walk in and ask the receptionist, ‘Is this going to embarrass me?’ If he or she says yes, then go out to your car and change.”

This is just one part of better understanding your potential employer. “You shouldn’t go near a job interview without decoding the organization, the people you’re talking to, the hidden agenda of what the job is about. Definitely don’t go into an interview without having spoken to someone who works there and finding out what kinds of people they like to hire,” says Lees.

2. “Be yourself.”

This one is particularly irksome to Lees: “The is a useless piece of advice. It’s like saying, ‘sit there and look handsome’.” Sullivan agrees: “That’s a good way to not get hired.”

It’s important to remember that “a job interview isn’t a natural slice of life, it’s a performance,” says Lees. Sullivan says you should demonstrate that you can give the company what it needs: “You want apples, I’ve got apples. You want oranges, I’ve got oranges.”

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be authentic, nor should you lie. But it’s your job as the candidate to figure out what the hiring manager is looking for and tell a story that shows you meet those requirements. Sullivan encourages candidates to figure out in advance what questions the interviewer will ask (again this can be easy using the internet and social media) and what answers they’re looking for. Then write scripted responses. “Don’t memorize them but know what you’ll say,” he advises. He also suggests that you practice by videotaping yourself to see how you come across.

The first 90 seconds of the interview are particularly crucial. “The myth is that you have 45-60 minutes to get to know each other. The reality is that first impression matters most. And it’s almost content free. It doesn’t have to do with skills and experience and knowledge; it’s about whether you look like a good colleague,” says Lees. Studies have shown over and over (see this one and this one and Malcolm Gladwell’s findings in Blink) how quickly we make judgments about people and how important it is to make a good first impression. So don’t fool yourself into thinking you can just be who you are. You need to nail those first few seconds by carrying the right props (think sleek briefcase or purse, not disheveled backpack), sitting in the right place (across from the interviewer not next to her), and handling the handshake properly (make it firm). And don’t forget that you need to be good at small talk too. As you walk from reception to the interview room, you want to be sure you “talk naturally, in a normal speed of voice, look someone in the eye, and exchange pleasantries,” says Lees. “You are trying to create the impression of someone who is comfortable with themselves.”

3. “Remember they’re not just interviewing you. You’re also interviewing them.”

Generally speaking, this doesn’t really hold up. “It’s not a conversation. One side is scared to death,” says Sullivan. And Lee concurs: “I see this piece of advice a lot and I really don’t like it. It encourages lack of preparation and passivity. When you’re in the interview room you should act and behave as if the is the only job you want.”

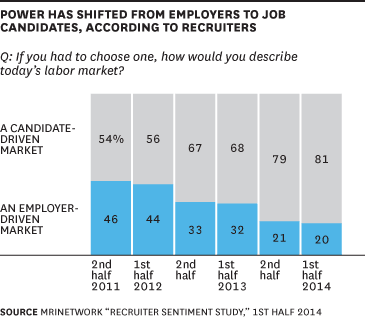

But Sullivan also says that the approach can sometimes work in certain settings. “I call it the Joe Montana interview where you ask, ‘Why should I play for your team?’ And it’s ok to say ‘I’m in demand’ but then you have to be able to back it up.” This is a tricky thing to pull off though so it’s probably better to focus on demonstrating what you can give the employer rather than expecting them to sell you on the role. Generally, that’s the power dynamic in the room. Though it can shift, depending on the industry, the region, and the health of the economy. Recent surveys show that power has slipped to the applicant.” In fact, a 2014 survey of recruiters showed that 81% felt that today’s job market is driven by candidates, not employers.

4. “When asked what your greatest weakness is, give one that’s really a strength.”

“Don’t admit you have weaknesses” is bad advice. Claiming that you’re “too much of a perfectionist” or “too passionate” has become a cliché – your interviewer has probably heard this many times. This not only means you may come across as not 100% genuine; it also means you’re missing an opportunity to demonstrate self-awareness and a willingness to adapt. Sullivan says that you want your answer to follow this logic: “I, like everyone else, have weaknesses. But unlike everyone else, I find them, recognize them, and fix them.” Of course you don’t want to admit a weakness that would really count against you. Avoid saying something like, “I really don’t read people well.” But point out something that you’re genuinely working on. “That will show that you’re able to learn and develop,” says Lees.

5. “Don’t talk about money until you have an offer in hand.”

You don’t want to start talking about money until the time is right. “Companies don’t hire people who put money — or vacation time — first,” says Sullivan. “They want to know what you’re going to contribute not what you want.” If you can, delay asking or talking about money or benefits until you have an offer. “The best time to talk salary is when you have leverage, and you have leverage when they’ve fallen in love with you,” says Lees.

Of course, the hiring manager or recruiter may ask you about salary requirements. This is not an easy question to dodge, even though that might be in your best interest. Lees advises candidates to prepare short, professional responses and several lines of defense. First, have a general answer ready, something like “My requirements are negotiable”. If pushed, be prepared to go deeper and say something along the lines of: “This is roughly what I’m currently making but the job you’re interviewing me for is obviously different.” And, then, have a third answer ready if the interviewer pushes you further. Lees likes this kind of answer: “Well, I’m being interviewed for jobs paying…” He says it’s effective because “it’s a projection of where you see yourself in the marketplace.”

6. “Don’t ever admit you’ve been fired before.”

The good news is that employers’ attitudes toward switching jobs has changed. In fact, 55% of employers in a recent survey said they have hired a job-hopper and 32% said they have come to expect candidates to move jobs frequently. The bad news is that hiring managers still don’t want another manager’s rejects. So if you were fired or laid off, Sullivan advises avoiding the “f-word” if you can. “Your response should be short, uncomplicated, and as positive as possible,” says Lees. You can say “I didn’t expect to be there forever” or “I learned a lot on that job and then I moved on to the next opportunity”. And be sure not to criticize your former employer. That just reflects badly on you. Of course, if you’re asked directly if you’ve been fired, you have to be truthful. “The trick is to move on to the present by saying something like, ‘I was lucky because it gave me a chance to…’ and then bring the focus back to the present,” says Lees.

Interviews are rarely fun for anyone involved. Hiring managers don’t like to conduct them, candidates don’t like going to them, and in reality, they don’t seem to help to either side. “Interviews are horrible predicting devices,” says Sullivan, pointing to research by Google and academics that shows that interview performance wasn’t linked to job performance. That’s why many firms are moving toward testing candidates by giving them actual work to perform. “It’s like hiring a chef. Do you want to talk to him or taste his cooking?” says Sullivan.

But unfortunately, the interview is probably here to stay — at least until someone comes up with a better alternative. In the meantime, it’s your job as an applicant to recognize the process is flawed but do your best to shine anyway.

For more on interviewing, see:

Signs That You’re a Micromanager

Finding the Money in the Internet of Things

November 10, 2014

How to Spend the Last 10 Minutes of Your Day

How much sleep did you get last night? If the answer is “not enough” you’re hardly alone. According to Gallup’s estimates, almost half the people you’ll run into today are suffering from some level of sleep deprivation.

We often dismiss a little morning fatigue as an inconvenience, but here’s the reality. Missing sleep worsens your mood, weakens your memory, and harms your decision-making all day long. It scatters your focus, prevents you from thinking flexibly, and makes you more susceptible to anxiety. (Ever wonder why problems seem so much more overwhelming at 1:00am than in the first light of day? It’s because our brains amplify fear when we’re tired.)When we arrive at work sleepy, everything feels harder and takes longer. According to one study, we are no more effective working sleep-deprived than we are when we’re legally drunk.

It’s worth noting that no amount of caffeine can fully compensate for lack of sleep. While a double latte can make you more alert, it also elevates your stress level and puts you on edge, damaging your ability to connect with others. Coffee can also constrain creative thinking.

To perform at our best, our bodies require rest—plain and simple. Which underscores an important point: on days when we flourish, the seed has almost always been planted the night before.

Since most of us can’t sleep later in the morning than we currently do, the only option is to get to bed earlier. And yet we don’t. Why? The reason is twofold. First, we’re so busy during the day that the only time we have to ourselves is late in the evening – so we stay up late because it’s our only downtime. Second, we have less willpower when we’re tired, which makes it tougher to force ourselves into bed.

So, how do you get to bed earlier and get more sleep? Here are a few suggestions, based on goal-setting research.

Start by identifying an exact time when you want to be in bed. Be specific. Trying to go to bed “as early as possible” is hard to achieve because it doesn’t give you a clear idea of what success looks like. Instead, think about when you need to get up in the morning and work backwards. Try to give yourself 8 hours, meaning that if you’d like to be up by 6:45am, aim to be under the covers no later than 10:45pm.

Next, do a nighttime audit of how you spend your time after work. For one or two evenings, don’t try to change anything—simply log everything that happens from the moment you arrive home until you go to bed. What you may discover is that instead of eliminating activities that you enjoy and are keeping you up late (say, watching television between 10:30 and 11:00), you can start doing them earlier by cutting back on something unproductive that’s eating up your time earlier on (like mindlessly scanning Facebook between 8:30 and 9:00).

Once you’ve established a specific bedtime goal and found ways of rooting out time-sinks, turn your attention to creating a pre-sleep ritual that helps you relax and look forward to going to bed. A major impediment to getting to sleep on time is that when 11:00pm rolls around, the prospect of lying in bed is not as appealing as squeezing in a quick sitcom or scanning tomorrow’s newspaper headlines on your smartphone. Logically, we know we should be resting, but emotionally we’d prefer to be doing something else.

To counteract this preference, it’s useful to create an enjoyable routine; one that both entices you to wind down and enables you to go from a period of activity to a period of rest. The transition is vital. Being tired simply does not guarantee falling asleep quickly. First you need to feel relaxed. But what relaxes one person can exasperate another. So I’ll offer a menu of ideas to help you identify a bedtime ritual that’s right for you:

Read something that makes you happy. Fiction, poetry, graphic novels. Whatever sustains your attention without much effort and puts you in a good mood. (Warning: Never read anything work-related in bed. Doing so will make it more difficult for you to associate your bed with a state of relaxation.)

Lower the temperature. Cooler temperatures help us fall asleep and make the prospect of lying under the covers more appealing. The National Sleep Foundation recommends keeping your thermostat between 60 and 67 degrees overnight.

Avoid blue light. Exposure to blue light – the kind emanating from our smartphones and computer screens – suppresses the body’s production of melatonin, a hormone that makes us to feel sleepy. Studies show that reducing exposure to blue light, either by banishing screens before bedtime or by using blue light-blocking glasses, improves sleep quality.

Create a spa-like environment. Create a tranquil environment with minimal stimulation. Dim the lights, play soothing music, light a candle.

Handwrite a note. One of the most effective ways of boosting happiness is expressing gratitude. You can experience gratitude while writing a thank-you note to someone you care about, or privately, by listing a few of your day’s highlights in a diary.

Meditate. Studies show that practicing mindfulness lowers stress and elevates mood.

Take a quiet walk. If the weather’s right, an evening walk can be deeply relaxing.

Experts recommend giving yourself at least 30 minutes each night to wind down before attempting to sleep. You might also try setting an alarm on your smartphone letting you know when it’s time to begin, so that the process becomes automatic.

However you choose to use the time before bed, do your best to keep this time free of negative energy. Avoid raising delicate topics with your spouse, and don’t even set your morning alarm right before going to bed – it will just get your mind thinking about the stresses of the next day. (Instead, re-set your alarm for the following morning right when you wake up.)

And finally, keep a notepad and a light-up pen nearby. If you think of something you need to do the next day, jot it down instead of reaching for your smartphone. Do the same for any important thought that pops into your head as you are trying to fall asleep. Once you’ve written it down, you’ll find it’s a lot easier to let go.

November 7, 2014

Tactics for Asking Good Follow-Up Questions

Whether you are looking to hire someone, decide whether to trust someone, or enter a business partnership, the better you are at judging people, the better off you will be. Unfortunately, most people are just plain bad at reading others. Several decades of research among psychologists has indicated all sorts of blind spots, biases, and judgment errors we make in assessing people. Much of that research has focused on the mental processes we use to interpret what we see or hear. But errors also occur way before that – the problem can begin with the questions we ask to understand people in the first place.

When you want to get a read on someone, what questions do you ask? Most people have go-to questions. The ones I hear most often are open-ended questions like, “What are your greatest strengths and weaknesses?” “What do you want to be doing in five years?” and “What motivates you?” Some savvier questioners ask behavior-based questions, like “Tell me about a time when you….”. Sounds great, right? Now, ask yourself if you have ever once actually learned the truth about someone by their responses to these questions. How many times have you relied on people’s responses to these questions only to see later that those responses meant nothing at all? Most people ask a question like this and then move onto another topic, seemingly satisfied that they heard what they needed to hear. In reality, they learned nothing about the other person.

In my experience conducting interview-based assessments for the last 12 years, I have found that this is because the first answer to one of these questions is only marginally helpful and may even be irrelevant. Yet most askers simply accept what they hear (good or bad) and, without asking any follow-ups, move on to the next topic on their list.

But the key to understanding people lies in the follow-up question. In my experience, there are two major reasons people don’t ask good (or any) follow-up questions. First, many interviewers aren’t actually paying close enough attention to ask detailed follow-up questions. To ask a good follow-up, you need to pay very close attention to how the interviewee responds to your initial question, and then build on his or her answer. The second reason most people are hesitant to probe is out of fear of offending the other person. But being polite isn’t the same thing as letting the other person off the hook.

Ask a follow-up that will help you really uncover what you are seeking to learn. Be curious, and you will be amazed what you uncover. Here are three types of follow-up questions that will enable you to understand more about a person:

1. Ask your original question again, slightly differently. Don’t be afraid to ask the same question twice. If I am interviewing someone and the person either deflects my first question or doesn’t give a real response, I will often say, “Let me ask you this another way…”. It is effective because you communicate that you are not letting the person off the hook, but you’re allowing them to save face by at least implying that maybe your initial question just wasn’t clear enough. It is a highly effective method of extracting a real response that will actually be predictive of behavior.

Caution: just make sure you change the way you phrase this second question, otherwise it can seem adversarial. The key is to ask the question another way, and declare that you are doing so.

2. Connect their answers to each other. One of my favorite strategies to understand people better is to link their responses to something they said earlier. I’m not talking about an attempt to catch someone in a lie, but instead connecting the dots between their answers. Good judges of character do this naturally – they listen intently, and tie what they hear to something said earlier in the conversation. Ask something like, “Oh, that’s like the time you…?” or, “Is that what you meant earlier when you said…?”. Beyond allowing you to understand the person better, it communicates that you are really listening, and actually provides meaningful insight to the person by pointing out a connection that he or she may have not even seen. It allows you to synthesize information rather than just hear it.

Caution: Overusing this can make you seem like a police detective seeking a “gotcha” moment. Avoid saying things like, “But that’s not what you said earlier…” What I am suggesting is to synthesize rather than interrogate.

3. Ask about the implications of their answer. When people answer a question without being particularly revealing, or by giving a very safe answer, what do you do? For instance, when asked about greatest weakness, someone says, “I’m a perfectionist” or “I work too hard.” Rather than accept answers like that at face value, seek to really understand the person by asking about the implications of their answers. With a self-proclaimed perfectionist, you might ask, “How does your perfectionism play out in the workplace?” or “What are the consequences of your detail orientation?” And don’t stop there – keep asking implication questions until you are satisfied you know what you need to know about the person.

Caution: When asking about implications, avoid being a litigator and turning them into leading questions. Instead, truly be curious about the behavior and what its effects are.

Coming up with a great list of questions is only the first step in conducting an in-depth interview. It’s the follow-up questions that will really tell you who you’re dealing with.

What Makes Someone an Engaging Leader

“How can we have the highest profitability in five years and still have gaps in employee engagement?” asks an executive at a large industrial products company. The reality is that the two don’t necessarily go together. This management team, like many others, has fought to increase profitability through business transformation, restructuring, and cost-cutting, without devoting much thought to keeping employees engaged and connected. As a result, the company may find it hard to sustain the gains, much less drive future growth. Organizational agility, innovation, and growth are really difficult without engaged employees.

The research team at AON Hewitt has made it a priority to understand what is going on in enterprises where both financial performance and employee engagement levels are soaring. Our ongoing study of the companies we’ve labeled Aon Hewitt Best Employers – firms that achieve both top quartile engagement levels and better business results than their peers – finds that they do have something in common. It’s the prevalence of a certain kind of leader, not just at the top, but throughout the ranks of the organization. These individuals – we call them engaging leaders – are distinguished by a certain set of characteristics.

What do these leaders of highly engaged teams have in common? Through extensive interviews we learned that they tend to have had early stretch experiences that shaped them; tend to share a set of beliefs about leading; and tend to exhibit certain behaviors that help to engage those around them.

Formative early experiences. Engaging leaders don’t just start out this way. “I started in the call center,” a CEO from a financial services business unit told us. “I know what it’s like and I still like to go sit with agents and listen.” We often heard in our interviews, as Warren Bennis and Bob Thomas did in their crucibles of leadership research, about early experiences that leaders felt had shaped them. They were not always of the unpleasant, mettle-testing sort; sometimes the person had a caring, attentive mentor; a stretch assignment that “chose the leader” instead of the leader’s choosing it; an assignment that required them to win over people who used to be their peers. The common thread is the reflection on the early experience that allows a leader to learn something, and gain self-confidence, humility, and empathy.

Guiding beliefs. Underneath an engaging leader’s behaviors are a powerful set of beliefs. They feel it is their responsibility to serve their followers, especially in times of crisis and change. Many expressed core beliefs about the importance of personal connection. For example, a CEO of a beverage company, asked to name the most important responsibility of a leader, said it was “to create the emotional bond between our people and the organization.” Another CEO declared that “Leadership is a contact sport.” When we talked to a leader in an engineering department about why he thought he was regarded as an engaging leader, his thoughtfulness about human relationships came through. “People won’t remember what I did,” he said, “but they will remember how I made them feel.”

Engaging behaviors. We also noted a set of common behaviors, no doubt driven by the beliefs we’ve just been discussing, and clustering around five themes. Engaging leaders step up, opting to proactively own solutions where others cannot or do not. They energize others, keeping people focused on purpose and vision with contagious positivity. They connect and stabilize groups by listening, staying calm, and unifying people. They serve and grow, by empowering, enabling, and developing others. And they stay grounded, remaining humble, open, candid, and authentic in their communication and behavior. These behaviors are continually validated in our leadership workshops, where we see people in action and hear about recent challenges they have worked to overcome.

These are the hallmarks, then, of engaging leaders – and almost every company has at least some of them. Few workforces, however, enjoy the general condition of having engaging leadership. That’s a systemic belief in the power of engagement that transcends the personal strengths and discretionary actions of individual managers. The organizations trying to make engaging leadership part of their culture are figuring out how to do four things on an ongoing basis:

Measure engagement levels. You can’t manage what you don’t measure. The CEO needs to own the engagement survey and follow-through. Enough said.

Develop engaging leaders. Workshops and coaching are required to help leaders reflect on their early experiences, find their own beliefs and purpose, and make engaging behaviors more habitual. When the number of engaging leaders amounts to a critical mass, their energy and mutual support can change the engagement culture of the organization.

Assess and select engaging leaders. Filling a lot of high-impact roles with engaging leaders should be the objective. Now that we have a good understanding of the experiences, beliefs, and behaviors that typify engaging leaders, it should be possible to use personality instruments, structured interviews, and 360 instruments to predict whether someone is likely to be engaging or not in a leadership role.

Measure and reward engagement achieved. Tying incentives to engagement survey scores is tricky and can lead to unintended consequences. However, we are seeing more organizations get serious about recognizing leaders who are engaging and holding those who are not accountable.

Engagement is a leadership responsibility – but by and large, with only , leaders are failing in this regard. Our research suggests that, for most companies, the turnaround won’t happen quickly. The fact that the most engaging leaders are the products of early experiences and deeply held beliefs means that new ones can’t be minted overnight. It will never be a matter of running through some behavioral checklist. But there are steps that employers can take to give more teams the benefit of engaging leadership – and, over time, to reach the levels of innovation, quality, and productivity that can only come from highly engaged people.

November 6, 2014

5 Examples of Great Health Care Management

I may not be in touch with all my emotions, but there is one I know all too well — jealousy. I have worked my entire career in great health systems with fabulous people. And yet, when I go “outside,” I constantly see health care providers working brilliantly together in innovative ways that I had not even imagined. It makes my chest ache with envy. This type of jealousy is the deepest and most sincere expression of respect of which I am capable.

Here are just five examples of the dozens of innovations out there that make my head and my heart hurt. I hope they make you feel envious, too — and that you will send us your own examples so that we might learn from them as well.

1. Transparency at University of Utah Health Care

In December, 2012, the University of Utah health care system started posting on its “Find-a-Doctor” sites all patient comments received after office visits. It wasn’t easy for Utah to reach this decision – its physicians had plenty of misgivings, but they were also irritated by the negative comments made by small numbers of patients on existing social media sites.

The logic was that trying to get data from all patients would lead to a much higher volume of comments, and they would paint a more accurate picture of the quality of care that the University of Utah offered. So, after a period of “internal transparency” during which only Utah personnel could see the data, Utah went public with all the ratings and comments – good, bad, and ugly.

As it turns out, the vast majority of comments have been extremely positive, the kind of praise that would make one’s mother blush. And the relatively few negative comments have had a profound impact on the physicians themselves. Physicians suddenly understand that every patient visit is a high stakes interaction, after which patients might write positive or negative comments.

The result has been so much more than a marketing ploy – it has changed the care being delivered. The Utah physicians with whom I have spoken all agree (some grudgingly) that the transparency has made them better and more compassionate caregivers.

2. Culture of shared responsibility at Mayo Clinic

When I visited the Mayo Clinic this spring I was amazed by how well everyone worked together to give patients first-rate, coordinated care. For example, if a patient is referred to a heart failure specialist because of shortness of breath, but the real problem turns out to be lung disease, the patient will be sent to a pulmonologist – but that initial heart failure specialist continues to play to role of doctor to the patient, making sure all the loose ends are tied up during and after the consultation. It’s wonderful for the patients, but not the way most specialists in U.S. health care work.

I asked some Mayo physicians why they were willing to do this “extra work” beyond their specialty expertise. One said, “Look, we think we are pretty good, but we know that these patients did not come here for us as individuals. They came because we’re the Mayo Clinic. So we all know that they are not really ‘my’ patients – they are ‘our’ patients.”

I thought of how most organizations attract patients using the “star” system – they market the superstar cardiologist or neurosurgeon, for example. But the schedules of those superstars are often booked for months in advance. Guess which model is more likely to accommodate growth? The “star” system or the group culture?

3. Teamwork at Northwestern’s Integrated Pelvic Health Program

At Chicago’s Northwestern Medicine, the Integrated Pelvic Health Program provides care for patients with problems like incontinence, uterine and vaginal prolapse, anal fissures and fistulas. The specialists with the expertise needed to address these difficult issues are all concentrated in one place – gynecology, urogynecology, and colorectal surgery. And in the middle are the physical therapists, who teach the patients exercises that strengthen the muscles to get their problems under control.

When I walked around this center and saw physical therapists talking with surgeons about shared patients, it suddenly dawned on me that I could not remember the last time I had actually talked to a physical therapist taking care of one of my patients. In fact, I wasn’t sure that I had ever talked to a physical therapist taking care of one of my primary care patients. There was no question that the care delivered by physicians and physical therapists who were really working like teammates was better than what I had been doing.

This is just one of dozens of examples I’ve seen of co-location leading to better teamwork. Hennepin County Medical Center moved dental next to the emergency department. University of Utah put case management right in the intensive care units. Teamwork is not just easy – it’s natural. These organizations understand how critical co-location is to real teamwork, and how important real teamwork is to patients.

4. Addressing socioeconomic issues at Contra Costa

At Contra Costa Health, a Bay Area safety-net provider, patients in waiting rooms were asked about their most important health concerns. The number one issue, named by 62% of patients, was having enough food. That was followed by housing (58%), then jobs and utilities. Not long after, Contra Costa began working with HeathLeads, which trains college-aged “advocates” to address socioeconomic issues like the ones named by Contra Costa’s patients, and places the advocates in emergency departments and practices. HealthLeads helps address problems that fall outside of what traditional health care can do, such as access to food subsidies.

Within weeks of the launch, Contra Costa physicians could see that some of their patients had better control of their chronic conditions because they had access to healthier food. In discussing one patient who had lost four pounds in eight weeks, one physician said, “I felt like I had finally been a good doctor to him and it wasn’t due to anything I learned in medical school.” Another doctor said, “This is the help I have needed for the past two decades to care for my patients. I now have something to offer my patients when I tell them to eat healthier and they can barely afford groceries.”

Contra Costa’s CEO told me that they know their job is producing health, not health care. They understand that to do so, they need to figure out who outside of traditional health care can help them make a real dent in their patients’ health problems. And that required developing a collaboration focused upon their patients’ socioeconomic issues — the core competency of HealthLeads.

5. Consolidating care with the London Stroke Initiative

In 2010, the city of London decided to consolidate the care of patients with strokes at just eight of its 34 hospitals. This meant that 26 hospitals, including some quite famous ones, had to close their stroke services, so that there was sufficient volume at the eight Hyperacute Stroke Centers to support care by special teams of physicians, nurses, and therapists who were completely focused upon stroke patients. As described in the HBR-NEJM insight center last year, the result was a decrease in mortality for stroke by 25%, and a reduction in total spending for stroke patients by about 6%, despite the greater number of stroke patients who survived.

Concentrating volume led to better care, better outcomes, and saved money. Most London hospitals (some kicking and screaming) gave up their ability to care for acute stroke patients in the interest of patients and society.

When I presented this case to a class at Harvard Business School last year, one student from the U.S. said, “This is phenomenal. We could never do it here.”

What makes these five examples so painful for me is that none of them required much in the way of capital investment. But all of them required (and continue to demand) expenditure of social capital, changing in the way people work together. The results are impressive.

There are going to be more examples of things that make me jealous during this eight week HBR/NEJM Insight Center. As those roll out, we would like to invite you to send your own — perhaps from your own organization, or from somewhere else. Maybe even from a competitor.

The more it hurts, the better.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers