Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 45

November 17, 2023

El Greco

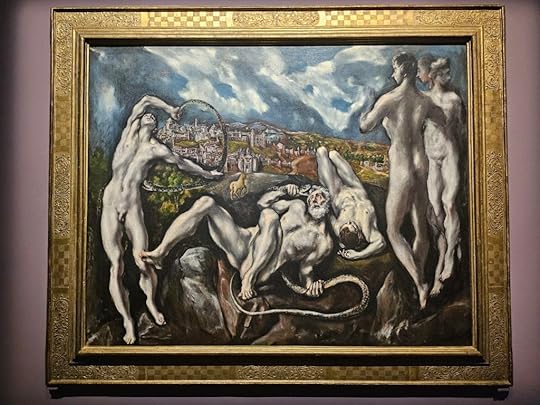

People are always misplacing this one and, due to the proximity of his exhibition to the Goya one I wrote about yesterday, I’m unsurprised that some people queuing for the ticket thought they were contemporaries. Domḗnikos Theotokópoulos, known as El Greco because he moved to Spain, was born in October 1541. Goya was born in March fucking 1746. They have two hundred years of difference. Still, can you blame the laymen when this is what you see?

How can this be over 400 years old?

How can this be over 400 years old?Anyway, let’s proceed with order.

1. The ExhibitionStill in Milan, this one is on the main floor of the royal palace, and it’s curated by a joint venture of Juan Antonio García Castro, director of the museum in Toledo, Palma Martínez – Burgos García, professor of history of art in La Mancha and author of one of the most modern essays on the painter, and Thomas Clement Salomon, bright young author and journalist. None of them is 84 years old and one of them is a woman, which I think is a good start.

The itinerary is divided into sections, from the original work influenced by traditional Orthodox art to religious subjects, and its main focus is always to keep his work grounded in his inspirations and influences, often by casually putting a Tiziano on the wall so that people can see the difference by themselves. It’s ambitious to say the least, and the lighting is absolutely lavishing.

It’s also the first time Italy is seeing stuff such as the Martyrdom of San Sebastiano, coming from the Cathedral of Palencia, the Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple coming from the Church of San Ginés in Madrid, and the Coronation of the Virgin painted for the high altarpiece of the Santuario de Nuestra Señora de la Caridad in Illescas, Toledo.

It would be improper for me to say which paintings I liked best, so this time I think I’ll just give you a couple of themes and elements that particularly hit my imagination.

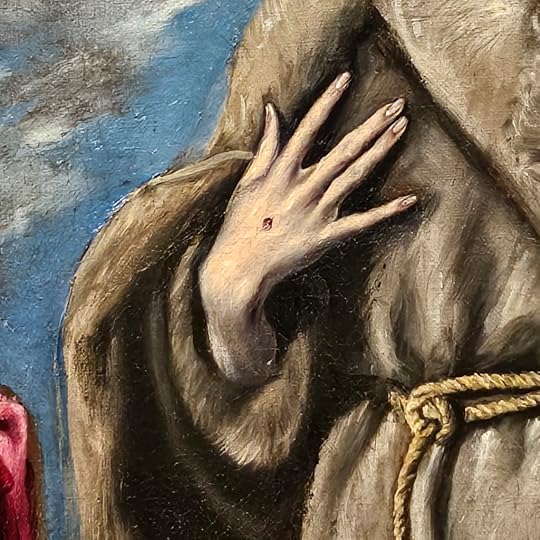

1. HandsI won’t be the first to say it, but you have to take a look at how this guy painted hands. Particularly the hands of men, and particularly the hands of suffering men such as Jesus and Saint Francis. They’re thin, bony hands, with nails made shiny but the incredible light washing them, and their pose is simply perfect. If you’re an artist who needs to get better at hands (and who doesn’t), go and sketch El Greco’s hands.

2. Backgrounds and Foregrounds

2. Backgrounds and ForegroundsThis is why I don’t blame people who think this guy lived in the late XVIII Century. Not only the figures are much closer to Gauguin than Tiziano: take a close look at these paintbrushes, at how a thin black like achieves a natural staccato between the flesh and the robes, and then try to convince me that this thing is from 1610.

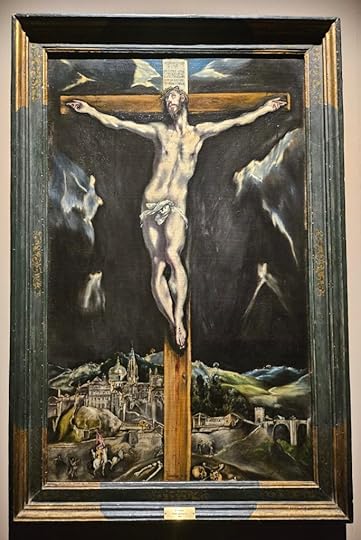

3. Everywhere ToledoYou might not like it, and personally I’m not sure how I feel about it, but one of the revolutionary and controversial moves El Greco did in his paintings was to set them in contemporary times and places. He claimed it was for people to feel closer to the scene, and the argument worked even with the Catholic Church, so who am I to argue? One bonus side is that we get to see a lot of his beloved Toledo as the background of religious subjects who have nothing to do with the city.

Take a look at this one at the bottom of a crucifixion.

Take a look at this one at the bottom of a crucifixion.My personal favourite is represented behind a portrait of Saint Martin, the famous Roman knight who cut his mantle in two pieces to give half of it to a beggar during a cold winter night. It’s a city made of light and water, bare reflections and optic tricks, and the chill they bring you is not a physical one, but it’s pure emotion.

4. LaocoönI know, I said I wasn’t going to pick a favourite painting, but come on, that thing is gorgeous! It’s the painting I showed you at the beginning of the article, created between 1610 and 1614 during four of the most prolific years in the artist’s entire career, and it’s probably my favourite because I have a natural dislike for most religious subjects.

The subject is mythological of course: as you might remember, Laocoön was a Trojan priest and one of the few people still in possession of a brain after seeing the Greeks seemingly leaving their shores. He tried to warn the people of Troy not to bring the fateful wooden horse inside the city’s walls and his god Poseidon rewarded him by sending a sea monster to swallow him and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus. One can survive a ten-year siege but, apparently, not Poseidon’s whims.

The classical Laocoön Group had been unearthed in February 1506 in Rome, in the vineyards of one Felice De Fredis who immediately warned Pope Julius II. Luckily enough, the Pope was an enthusiastic scholar and was very fond of classical arts: he was the patron of both Michelangelo and Raphael, commissioned the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the expansion of the Vatican and Bramante’s courtyard. He was also a warmonger and was mostly responsible for the tensions with the future Protestant Church. Still, another guy might have disregarded the discovery or even destroyed it.

Julius II sent to the site his best people, including Michelangelo and the Florentine architect Giuliano da Sangallo, accompanied by his eleven-year-old son Francesco who would later become a sculptor.

The discovery had a tremendous impact on intellectuals and artists way into the Baroque period. To better put in context El Greco’s groundbreaking work, the exhibition in Milan dedicates a whole room to the painting and gives us a 1:1 chalk reproduction of the original classical complex on one side.

It’s a reproduction, but still…

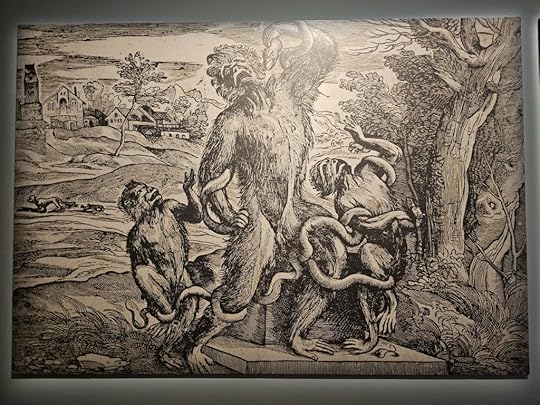

It’s a reproduction, but still…On the other side, we are shown enlarged panels with some contemporary sketches of the work, specifically:

Sisto Baldocchio‘s etching included in the XVI Century Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae;Marco Dente‘s drawing from 1523;Nicolas Beatrizet‘s engraving from the French artist, also included in Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae;a parody by Tiziano.This last one has to be my favourite, and you can almost see how the guy was so fed and tired of hearing people talking about the bloody statue.

Tiziano was not impressed.

Tiziano was not impressed.

November 16, 2023

Goya in Milan

The exhibition is called “The Rebellion of Reason”, echoing Goya’s famous statement on the monsters-producing sleep of reason, it’s set up at the lower level of Milan’s Royal Palace, and it’s curated by Víctor Nieto Alcaide, an 83-years-old Spanish historian of arts (and historian of Spanish art) who published a beautiful book on the usage of light in the Renaissance and the Middle Ages. It spans across 7 sections and doesn’t display an extensive collection, translations are questionable, texts in the curated boards are hilariously banal, but it’s a unique chance to see incredible pieces and you shouldn’t miss that.

One of my favourite “explanations”. It roughly reads: “1815-24: Probably in this span of time, Goya creates the Disparates, etchings that are very difficult to interpret due to their enigmatic quality.” Oh, they’re difficult to interpret because they’re enigmatic? You don’t say.

One of my favourite “explanations”. It roughly reads: “1815-24: Probably in this span of time, Goya creates the Disparates, etchings that are very difficult to interpret due to their enigmatic quality.” Oh, they’re difficult to interpret because they’re enigmatic? You don’t say.To encourage you for a visit, or to make up if you’re unable to drop by and see it, here’s my top 5 works you can see in the exhibition.

5. Might not the pupil know more?Caprice number 37, etched between 1797 and 1799, this work opens the section dedicated to dunces, through which Goya denounces the educational system. You can see why it’s close to my heart. Goya points the finger against teachers, in this particular stance, and those teachers who work through the forceful imposition of authority, threatening a pupil instead of doing their fucking job. You can read more about it on the Prado website and on the MET website.

The etching is displayed with the original copper plate, part of a massive restoration endeavour.

4. The Sleep of ReasonYou know I’m not snobbish, and I won’t say something is not good just because everybody likes it. Except for Everything Everywhere All At Once, of course: I’m still shunning that.

It was very emotionally impactful to see the copper plate for this masterpiece: the fine details are amazing.

3. Scenes from an Asylum

Casa de Locos (literally: Madhouse) is a very small oil on panel painted between 1812 and 1819 after he went to the Saragozza mental asylum to visit his aunt and uncle who were inmates over there. Goya had recently been ill himself, a sickness that created a lasting hearing impediment, and had to battle depression in a period where mentally ill people were seen as possessed.

The dimensions of the painting do nothing to impair details: the claustrophobic scene is illuminated just by the light filtering through a barred window up on the barren wall, characters are raving in a state of complete neglect and they sport accessories meant to symbolise the madness of institutions.

It’s 45 x 72 cm but I swear it looks smaller.

It’s 45 x 72 cm but I swear it looks smaller.2. Cone-hooded people

I’m cheating a bit here, grouping two paintings into one category, but they’re rightfully placed together. The first one is the Procession of Flagellants, painted between 1808 and 1812 and depicting a tradition technically outlawed by King Carlos III back in 1777.

The repentant zealots are dragging a crucifixion and a statue of Nuestra Señora dela Soledad, cleverly depicted without a face. The white fabric on the flagellants is half-transparent, a thing you can’t quite appreciate from any picture, and the largest brush stroke has to be 1 cm maximum. The whole thing is so vivid that it looks much, much smaller.

The second painting is The Inquisition Tribunal, done between 1812 and 1819, and features a miserable dude being interrogated on the stand while two other miserable dudes are sitting miserably on the side. Just like the previous painting, it’s an accusation of how Ferdinand VII’s policies are dragging back Spain to obscurantism.

Guests and witnesses are no more than strokes of the brush, as are the devils and flames on the sanbenitos (robes) of the accused. This unfortunately means they had been found guilty and they were going to burn in the public square.

I think it was a stroke of genius to place these two paintings together with a quote summoning Goya in front of the Inquisition itself because of the Maja Desnuda. Don’t get your hopes up: they’re not on display.

1. The Colossus

The most impressive piece on display, without any doubt, especially after the whole misattribution shenanigans. It isn’t big either, 116 x 105 cm, and again the details of the landscape below the giant are absolutely impressive. Still, there is no way to see what the giant is crushing between his fists nor, I’m afraid, you can get a better look at his ass.

You know you’re looking at something important when it’s the only room with a bench.

You know you’re looking at something important when it’s the only room with a bench.

So, that’s it. My top 5. Did you see the exhibition? What did you think of it?

Next up on my list are El Greco, also at the Royal Palace, Van Gogh at the Cultures Museum, and the exhibition on Samurai Women at Tenoha, with the illustrations of Benjamin Lacombe. I should really get a move on, with this last one.

#ChthonicThursday: Minthe

In Greek mythology, Minthe was an underworld naiad, a nymph of water, connected with the infernal river Cocytus, so I guess this could also work for #MermaidMonday. Hades, king of the Underworld, was very fond of her and she eventually became his mistress, but this didn’t escape Persephone or, according to other accounts, her mother Demeter: the nymph was eventually turned into mint, the aromatic plant we know today. She’s today’s profile on my Patreon.

November 15, 2023

What is a myth?

Among the most common are that myths are stories about gods, myths are sacred stories, myths are stories that explain the way the world is, or myths are simply traditional stories that hand on collective knowledge or experience.

Writers from various disciplines and intellectual movements have interpreted myth in different ways. Myths have been seen as a “disease of language,” as garbled memories of historical events, as a mode of prelogical thought, as expressions of the subconscious mind, as symbolic descriptions of the natural world or symbolic statements about the social order, and as the spoken part of ritual.

Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (2002)

This is how Geraldine Pinch’s book on Egyptian Mythology starts, and this is the first reflection I want to bring to you, as I’m collecting a pool of organized feedback from sensitivity readers on my novel and I wait to undergo what I hope will be the final round of editing. A while ago, we went through some of the Seven Basic Plots from Chrisopher Booker’s acclaimed book on storytelling and tropes: we talked about Monster vs Temptation, about the Dark Power, Overcoming the Monster, The Rebel, and the Descent to the Underworld. There might still be a couple of interesting things to expand upon, in connection to the story I’m writing, but I believe we have exhausted much of the interesting points.

This is why I’m turning to the tropes we can find in myths.

Whatever myths are, whether they’re just stories or attempts at explaining (super)natural phenomena, I always like to take a look at them and find a way to use them in support of my alternate history. Whenever myths are connected to the underworld, darkness, life and blood, death or the stars, I try and find a way to tie them together and explain them in the light of what I’m writing. It’s surprisingly easy, sometimes, and I suspect this is why pseudo-science has such an easy life in justifying all sorts of bullshit connected with ancient mythology. Let us be clear: mine is simply a narrative effort, and shouldn’t be taken too seriously. You can take me seriously when I talk about the necessity of rebelling against an unjust establishment, or how much family can suck.

G.S. Kirk, in his fundamental text Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures published in 1970 by the Cambridge University Press, proposes three main categories of myths:

a myth that tells a story, basically told for entertainment purposes, that can be a variation of the same myth that gets used in rites and ceremonies, only amended of the more secret elements and enriched by the same stuff we put in stories nowadays: action, romance, humour;operative, iterative or validatory myths: these are defined as stories that are believed to have the power to transform the real world and were usually repeated regularly during ceremonies, rituals and formal occasions. The counterpart to these myths are charter myths, equally ritual but thought necessary in order to maintain the status quo.explanatory or speculative myths, etiological in nature and meant to explain the origin of an object or an animal, the nature of a specific natural feature or, in stories such as creation myths, how the world came to be.Just as stories are often considered to be pertaining just to the first category, myths are often relegated to the third category and dismissed as superstitions. In fact, all it would need is a closer look at those stories to understand that there is so much more than “primitive people” believing the sun was created by a giant scarab.

Some myths seem to acknowledge that these questions may be unanswerable but provide strategies for coping with the sorrows and contradictions of human life.

Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (2002)

In taking a closer look at some myths and stories, I hope we will be allowed a deeper reflection on how we tell stories and what is the purpose of the stories we tell. I for one really hope to be telling something akin to an iterative myth, and that people will be encouraged to see modern charter myths when they see one.

November 14, 2023

What is a myth?

Borrowing G.S. Kirk’s distinction between three kinds of myth, today on my Patreon we take a look at entertainment, operative, charter and explanatory myths, and what this distinction means for us when we tell a story. The post will be released to the public tomorrow, over there and here on the blog.

November 12, 2023

#MermaidMonday: the Siren of Lispida

A thermal lake with waters that are rendered warm after staying entrapped for 25 years in crystal, a young Count suffering from chronic pain, a fateful encounter on Saint John’s Eve.

Join me on my Patreon for some Italian merfolk this Monday.

November 8, 2023

#ChthonicThursday: Tuchulcha

Tuchulcha was a double-gendered, lesser deity in Etruscan mythology, announcer of death and guide through the Underworld. They’re today’s feature on my Patreon.

November 6, 2023

Symbols and the Symbolic

In Egypt, concepts that might in other cultures belong to the realm of ab- stract philosophy were expressed by symbols, images, and, to a lesser extent, myths.

Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (2002)

While I was at the Aswan airport, waiting to catch my plane and return from my journey, I entered a local bookstore and grabbed a rather peculiar book. It stroke me as a book on the symbolic thought in Egypt and, possibly influenced by some philosophical discussions I had with my sommelier friend during our vacation, I decided to read it during the brief journey from Aswan to Cairo.

The book is this, and my review on Goodreads should give you a proper idea of what I got myself into.

Symbol and the Symbolic: Ancient Egypt, Science, and the Evolution of Consciousness by R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz

Symbol and the Symbolic: Ancient Egypt, Science, and the Evolution of Consciousness by R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

You should know what you’re getting yourself into (which I didn’t): this is a booklet of pseudoarchaeology which mixes esotericism, philosophy and mysticism. Many of the proposed “facts” about ancient Egypt are to be double-checked through more reliable sources and, though fascinating, lots of them are quite a stretch from credited theories.

Though fascinating, these speculations are far from being harmless and lead to stuff like Theosophy.

Still, I give it two stars instead of one because a couple of concepts might be of interest also to rational people who prefer archaeology over mysticism, particularly the idea of a centripetal vs centrifugal mind process when it comes to processing symbols.

A text to be handled with care.

As I mentioned above, the text is written by a guy who spent too much time in the sun studying the Luxor Temple: though his mapping work is generally considered to be of high value to archaeologists, he was a member of the Theosophical Society and a member of esoteric right-wing groups, not a stranger to antisemitism, and a convinced mystic. In one word: an asshole and a charlatan. Okay, they were five words.

Why am I talking about this booklet, you ask? Well, because if I tell you the two interesting concepts I found in it, you won’t have to buy it.

When an image, a collection of letters, a word or a phrase, a gesture, a single sound, a musical harmony or melogy have a significance through evocation, we are dealing with a symbol.

Or with the really neat picture of a hippo.Centripetal vs Centrifugal mind process

Or with the really neat picture of a hippo.Centripetal vs Centrifugal mind processIt’s significant that one of the most interesting concepts of the booklet isn’t expressed by the author but in the translator’s preface, penned by one Robert Lawlor who doesn’t seem to be any less of a charlatan.

With our present form of writing we use groups of arbitrarily formed abstract symbols (our alphabetical letters) which convey memorized sounds and visual associations. We are trained to thnk and communicate through these alphabetical letters — placed in certain (again, memorized) groupings or words — by reducing these abstract conventions into objective images in our minds. Simply stated, this means that when we read cat, we immediately register the formed image: ≽^•⩊•^≼

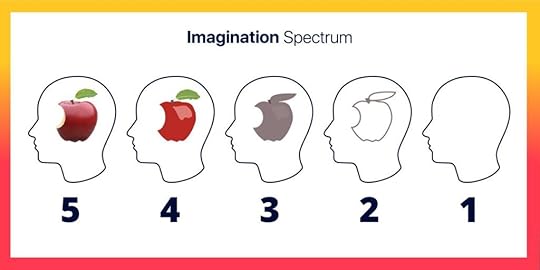

Now, the idea that everyone forms pictures in their minds is fairly outdated: the forming of a mental image is not a datum and can span from being completely absent (a phenomenon called aphantasia) to a high-resolution, almost photographic recreation (called hyperphantasia).

You might have seen this: it circulated on the dead bird social network a while back.

You might have seen this: it circulated on the dead bird social network a while back.People usually rest in between: a somehow foggy mental image is evoked by words and appears in the mind of the reader. Even if there is no picture, something happens. That’s what we need to bring home from this.

This habitual reduction from a nonobjective mental abstraction to a delimited image can be seen as an initially centripetal action, which, subsequently, disperses perception and knowledge into a classification of disconnected facts.

Basically, he’s saying that when you read the word “cat” you form an idea that rarely is a specific cat but mostly likely distils mentally into a specific picture all the cats you have seen in your life. You have your own Platonic idea of cat, in a way, and you might be able to describe some of the characteristics of the first thing that comes to your mind when you say “cat”. Mine is long-haired and grey, for instance.

[…] hieroglyphic writing works in the opposite or centrifugal direction. The image, the form, is there concretely before us, and it can thus expand, evoking within the […] viewer a whole complex of abstract, intuitive notions or states of being — qualities, associations and relationships […].

Trying to cut through the bullshit about inner beings and states of consciousness, what this guy is saying isn’t that far-stretched: a written language that works with abstract symbols such as ours, requires the mind to put symbols together and create a picture. If the picture is already given, the reader has to work out whether it’s a phonogram (red as a sound like our letters, as it often happened with non-determinative hieroglyphic signs), as a logogram (which is to say a written character that has a whole word in it), or as an ideogram. Ideograms in particular and logograms, particularly when the symbols were readable stylizations of objects, force the mind to a different kind of work.

The analytical mode first reduces abstraction to a defined image, followed by a proliferation of disconnected facts.

The analogical mode, on the other hand, first expands from the image into far-reaching associations, the inwardly unifies.

Saying it in another way, the hieroglyphic language might be seen as richer than ours, at least up to the point that each whatevergram can be used to create in the reader broader connections with more concepts than one, as we’re doing when we use word tricks and rhetoric. In this, the hieroglyphic language seems more akin to poetry.

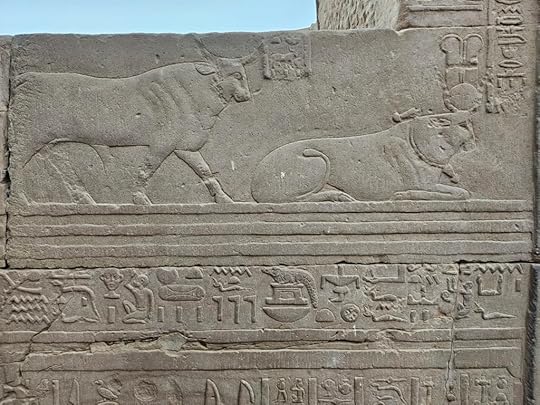

Inscriptions on the wall of the temple of Kom Ombo in Aswan

Inscriptions on the wall of the temple of Kom Ombo in AswanThe symbol is a material representation of immaterial qualities and functions. It is an objectification of things subjective in us and subliminal in nature.

No shit, Sherlock.

The Symbol as SynthesisTo better understand what does this mean, the author drags Kant out from his grave and who am I not to follow?

By synthesis, in the most general sense of the term, I mean the act of adding different representations to one another and of comprehending their multiplicity in one cognition.

Following up on this, and trying to leave out of the discourse his attack on science and the rational mind that doesn’t interest us, the author proceeds to define three kinds of synthesis and three kinds of symbols:

the vital synthesis — which is the natural symbol and its expression (tangible form, characteristic word or sound, and colour) — is the pure symbol;the action of synthesis , which represents the pseudo-symbol (such as the word, the vocable), replacing the image and determining the concept;the synthesizing effect of thought , or psychological synthesis, which represents the para-symbol, through the conventional symbol summarizing a thought.It is well known that the scarab was associated by the Egyptian to the Sun because of their habit of rolling around a ball of shit. No surprise in that. If we try to follow this reasoning, the actual scarab is the pure symbol: we might see one while wandering through the desert and immediately think of the sun, of creation, of the supreme god and so on. The pseudo-symbol which replaces the image is the word for scarab, Khepri, which also means “to develop”, and associates to the scarab one of the many aspects connected with what it actually means. The thought puts everything together: the actual scarab, the meaning encapsulated in its name and unwraps the whole thing in the centrifugal movement that, according to the author, eventually might lead to a deeper, more centred reflection of what it cosmically means to carry around a ball of shit.

A different perspective on animal worshipThis concept appears a couple of times, one in the introduction and one in the proper booklet. The idea is that the symbolic thought doesn’t stop to the hieroglyphic writing, but extends to the way deities were imagined and represented. The given example is the one of Anubis, the jackal.

[it] was not a worship of the animal itself, but a consecration made to the vital function which any animal particularly incarnates, […] used to support and clarify an essential function of nature. The Egyptian saw the jackal as incarnating certain characteristics, functions and processes of […] nature. The jackal is an animal which tears the flesh of its prey into pieces, which it buries and does not eat until they rot.

Note: he doesn’t. He sometimes buries meat to hide it from other predators, as a stash, and is fortunate enough to live in the desert so basically he’s a fan of jerky. That’s all.

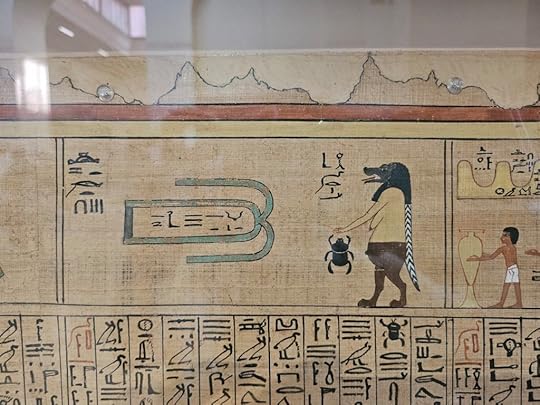

A stele with Anubis preserved at the Museum of Antiquities in Cairo

A stele with Anubis preserved at the Museum of Antiquities in CairoFrom this real, observed behavior, it becomes a symbol for both a metaphysical and physical process: digestion. […] “What would be poisonous for almost all other creatures in him becomes an element of life through a transformation of elements which are bringing about this decomposition”.

It’s a fancy way of saying that the Egyptians observed the jackal was a carrion eater.

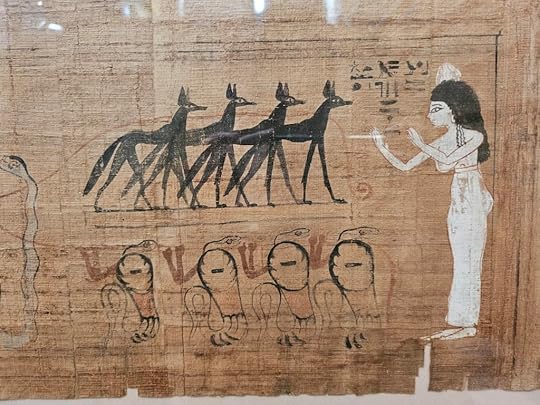

Jackals aiding a mummification process on a scroll preserved at the Antiquities Museum in Cairo

Jackals aiding a mummification process on a scroll preserved at the Antiquities Museum in CairoAnubis is always pictured leading the soul of the deceased into the first stages of the lower realms of the dwat […]. The urn holding the intestines had a jackal drawn on it. […]

The jackal is also the symbol of judgment […] because, in eating, it performs a precise, innate discrimination, separating out the elements capable of transformation and future evolution from the elements that are untransmutable within their present cycle.

Digestion is a destructive process: it is an analysis a break-down of material forms into the constituents elements.

This guy might be onto something, here, though the concept is expressed in such a pompous way that it might be drowned in the bullshit.

Scientists have observed that the jackal has a striking preference for viscera, even when fresh meat is available. This surely didn’t escape ancient Egyptians, when they decided to connect this animal with the dead and the process of mummification: a corpse without its viscera has more chances of preserving correctly in the heat of the desert. That’s why they started removing organs. The idea that judgment is also connected with the jackal’s dietary habits is fascinating enough.

Plus, they’re cute

Plus, they’re cute

November 5, 2023

#MermaidMonday: the Gwragedd Annwn

The Gwragedd Annwn, Wives of the Lower Lands, are Welsh water creatures connected with the myth of how the black cow came to be.

They’re today’s feature on my Patreon.

November 3, 2023

Hathor’s beer

Once upon a time, the god Ra started to grow old and humanity plotted to overthrow him. Upon discovering their treachery, he assembled the gods and decided to send against men a female embodyiment of his wrath: the goddess Hathor in the form of the Eye of Ra.

The goddess found the rebels hiding in the desert and slaughtered a great part of them, bathing in their blood.

Ra though that one day of slaughter was enough, but Hathor had enjoyed the slaughter a little too much, and she didn’t want to stop.

Ra summoned messengers who could travel as fast as shadows and sent them to fetch a large quantity of a certain red mineral. He then ordered his high priest in Heliopolis to grind the mineral, mix it with barley and make a crimson-coloured beer. The 7,000 jars of beer were poured in the fields, flooding them to the point that Hathor stopped to bathe in it and to look at her own beautiful reflection.

“She drank and it delighted her heart. She came back drunk without having noticed humanity. Ra welcomed her back and from that day on beer was drunk during the festivals of Hathor.”

And this is one of the many ways in which beer saved humanity.