Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 44

November 26, 2023

#MermaidMonday: Atargatis of Ashkelon

Atargatis, also known as Ataratheh and redubbed Derceto by Pliny the Elder, was a chief goddess in northern Syria, with evidence of her cult being discovered at Palmyria. She was a fertility goddess but also presided over her city at Aleppo, called Hierapolis by the Greek, where she was the baalat (the “mistress”) and presided over the welfare of her people: doves were sacred to her, as a testament to her role as love goddess, but she’s also connected to fishes and it’s said she turned into a fish herself. She’s today’s profile on my Patreon.

November 25, 2023

Milan’s Archaeological Museum

On Friday I wrote a piece concerning an exhibition you can see at Milan’s Archeological Museum and, in passing, I mentioned the museum’s collection amouns to… well, next to nothing. Since the internet is a beautiful place, people got upset and I thought I should rectify my statement: the very small archaeological museum in Milan has precisely two things worth seeing, at least in my humble opinion.

The Trivulzio Diatreta CupThis luxurious piece carries the name of the collector who brought it to Milan during the XVIII Century, alongside some objects that are now lost. It was part of a funerary trousseau found in the area of Novara, presumably near the grave of a high-rank individual.

Carlo Trivulzio was an abbot, one of the wealthiest collectors in Milan because the vow of poverty applies loosely: he bought this cup from Ferdinando Dardanoni, an antiquarian, and dedicated to the object a manuscript describing it with meticulous details on its discovery and the many hands it went through. According to his testimony and to the diary of the master of ceremonies in Novara’s cathedral, the cup was discovered on June, 9th 1675.

Due to its extraordinary beauty, the piece is also included in the additional notes to Winckelmann’s Ancient History of art and drawing when it was published in Milan in 1779.

The inscription reads: “Drink, and live many years”. Who am I to argue?

The Parabiago PlateThe second significant piece in Milan’s Archeological Museum is the so-called Parabiago Plate, a large dish discovered during building excavation works in 1907.

The shape of the object suggests a big platter used in ceremonies or simply banquets, and the scenes depicted on it also connect it with merriment: it’s the triumph of Cybele and Attis in the presence of the gods, a scene particularly loved by the high-rank society that helps us date the plate around the 4th Century A.D.

This particular date means the object is a resistance piece: Cybele and Attis were connected to the eternal cyclic renewal of life and prosperity, an anti-Christian concept, and the 4th Century A.D. saw an effort, from intellectual circles in the ruling classes, to restore the classical culture. Emperor Julianus (360-363 A.D.), labelled as “Apostate” by Christian writers, was the foremost of this intellectual and political movement.

November 24, 2023

Eyes, barley and wine

If you ask anyone to name an iconic symbol connected with Ancient Egypt, some will say the scarab, but many will say the eye.

The Egyptian seemed to be positively obsessed with that body part and it’s not very difficult to guess why: it looks like a jewel, and yet it’s soft and vulnerable; it can be scorched by the sun, and yet it produces water; it’s an element of symmetry in the human face, and yet it’s not that uncommon for an individual to have different eyes. They’re apparently redundant and yet, with their knowledge of medicine and their keen observant aptitude, Egyptian scholars must have been aware of what happens to your sense of depth when you lose one.

More on that later

More on that laterAdd to the mixture a linguistic fact: the noun used for “eye” is a feminine noun, and this leads to the eyes of certain gods being personified as goddesses. This is where things get interesting.

The Eye of RaRa creates stuff in disgusting ways I will not recount here. Suffice it to say that men were often said to be created by the tears of the Sun God’s eyes, and this is reflected in one of the plays on words that aren’t lost to us.

The creator brings forward the primaeval waters and then sets one of his eyes to wander around. The reasons are unstated and still escape us, but the Eye of Ra was also known as The Distant Goddess and, after her separation from the Sun God, they were never reunited.

Humanity, it says, came forth from the Sole Eye, which was sent out while the creator Atum was still alone ahd inert in the primeval waters. The cause of the Eye’s weeping is not stated, but it may be from loneliness as it searches for other beings.

Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (2002)

What’s interesting here is that humanity is not technically created by Ra, but it’s created by his Eye instead: this means that between the Creator and humanity there is a bigger distance than between the Creator and the gods, who sprung directly from his sweat (or other humours).

This also means that the vengeful Eye is technically humanity’s creator, which makes it more interesting when you think about that time when the Eye went on a vengeful spree and was placated with beer.

the Sole Eye was a separable active force even when the creator was still inert in the primeval waters. The Eye was sometimes treated as a female form of the sun god, but she was also called the “daughter of Ra.” Various important goddesses were associated with this role, most commonly Bastet, Hathor, Mut, Sekhmet, Tefnut, and Wadjyt.

Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (2002)

But we’re not here to talk about that.

We’ll talk about beer, but it will take me a longer route to get there.The Eye of Horus

We’ll talk about beer, but it will take me a longer route to get there.The Eye of HorusThe Eye of Ra is the right one (wedjat), but Horus is the god predestined to replace him and of course this means he has troubles with his eyes too.

The myths connected with Horus losing one of both of his eyes are a lot, which can’t be confusing if you’re looking for a singular narration that makes sense. Invariably the loss of one eye involves the enemy Seth, a foreign god worshipped by the Hyksos who became the epitome enemy in the narrations of the myths of Osiris and Horus: sometimes Seth rips one eye from Horus in battle, other times he simply pokes him, and in some narrations the eyes are ripped off as a punishment after the ungrateful Horus brings harm to his own mother Isis. In his Falcon form, it is said that the two eyes of Horus represent the Sun and the Moon, the latter being white and the former being red or green (two colours that the Egyptians treat as very similar in yet another attempt to blow your mind). The white eye can also be an allusion to blindness, of course, and sometimes it’s Thoth, the god of medicine, who looks for pieces of the eyes and restores them in the head of the falcon.

The Papyrus Jumilhac however tells a different story.

Basically a Ptolemaic monograph on religious rites of the XVII and XVIII centuries from Upper Egypt, particularly in the region represented by the falcon spreading his wings (nmtj) and the one represented by the jackal (jnpwt). The text was translated into French by Jacques Vandier in 1961, it’s preserved at the Louvre Museum, and you can see pictures of the pages through the website of the French National Museums Association.

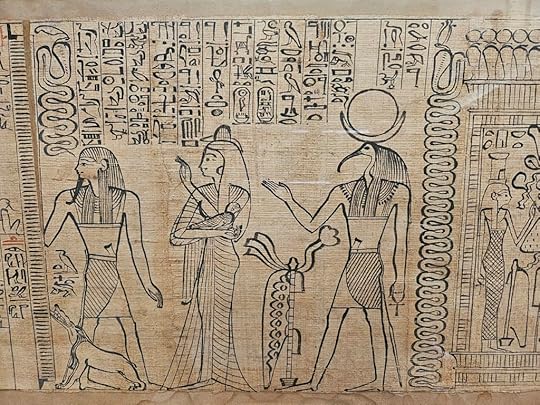

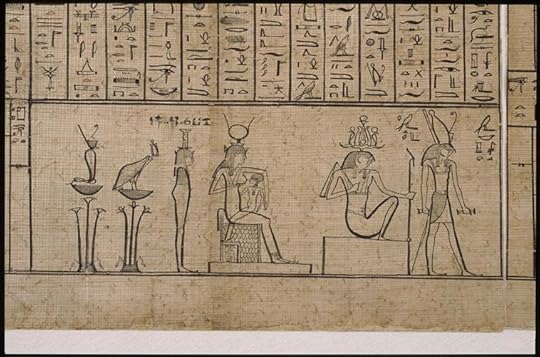

One of the pages from the Jumilhac Papyrus, showing Horus growing up and doing things.

One of the pages from the Jumilhac Papyrus, showing Horus growing up and doing things.In this story, it’s the jackal god Anubis who is given boxes with the eyes of Ra, and goes burying them around, particularly on a mountainside.

In this particular version of the myth — analysed by Philip John Turner in his 2013 book Seth: A Misrepresented God in the Ancient Egyptian Pantheon — his mother Isis wanders around and finds the buried treasure, but even she can’t violate what the jackal god has buried: his protection over tombs was one of the cardinal points of the whole pantheon, a source of reassurance for a culture that was genuinely worried about people messing with their tombs.

Isis weeps over the buried eyes of her beloved son.

From her tears, the first grapevines are born.

And we are certainly grateful for that.

And we are certainly grateful for that.However it happens that Horus loses his eyes, and however it happens that his eyes are restored, a final sacrifice is required: when Horus wins over Seth and the Divine Tribunal grants him the right to rule over Egypt, the son gifts one of his eyes to the mummy of his deceased father Osiris, and this sacrifice is the last piece needed for his father to be revived, if only in the Underworld.

In commemoration of this event, a wedjat eye was often placed over the evisceration wound on a mummy to make the body whole again.

Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (2002)

Beer and WineThe connection between wine and the Eye of Horus is far from being universal. The mainstream version is made popular by Diodorus Siculus, who claims it was Osiris who invented the vineyard and taught viticulture to his people before his untimely demise (you can read more about the Egyptians and wine in this excellent article). After his murder, his blood reddens the floodwaters of the Nile and waters the fields, which in turn can produce wine.

Wine however was not the Egyptians’ primary specialty (and still isn’t, with the exception of a couple of shiraz, but that’s just my personal opinion): their specialty was beer. And barley was closely, undoubtedly connected with Osiris.

Though the death of Osiris is a cardinal myth, his death was considered taboo, and we don’t have graphical depictions of what actually happened until very late in Egyptian history: we know that his brother Seth killed him multiple times, and his wife Isis went to extreme lengths to bring him back, eventually extracting life from his dead body (if you know what I mean) to give birth to Horus. The body of Osiris needs to be guarded against Seth and his followers, who repeatedly try to defile it. Eventually, he rises from his inert condition and becomes ruler of the Underworld, also thanks to the final gift of an eye from his son’s head.

“Are you an alien?”

“Are you an alien?”“…no?”

“Then, son, you’ve got a condition.”

His skin can be black or green. These colors may originally have indicated putrefaction, but they came to symbolize the connection of Osiris with a cycle of death and regeneration based on plant life.

Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (2002)

You wouldn’t believe how black the earth really is after the Nile has licked her feet.

You wouldn’t believe how black the earth really is after the Nile has licked her feet.During festivals of Osiris, the devotees used to build creepy little penis-shaped corn mummies, and they buried them in strategic locations, believing them to ensure both the resurrection of the dead and the fertility of fields. That part at least we can be sure it was true, as religion often makes for great fertilizer. The earliest example of the body of Osiris being linked to barley comes from a Middle Kingdom royal ritual, in which Seth is equated to donkeys trampling over the barley and destroying the crops. The connection between barley and the body of a god is only one of the many similarities between Egyptian theology and the early Christian traditions, but I digress.

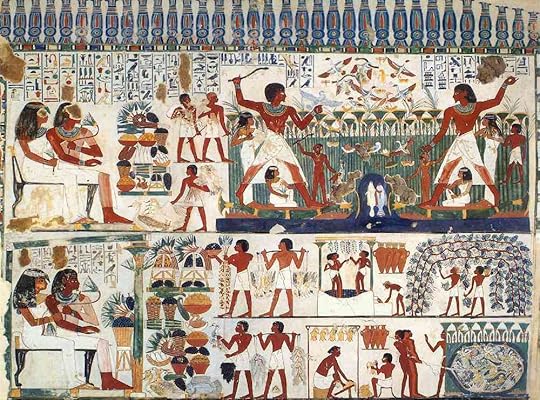

One of the things we did (not) see in Thebes, is a rare scene of people harvesting grapes and making wine on the walls of the tomb of a XVIII dynasty astronomer called Nakht.

One of the things we did (not) see in Thebes, is a rare scene of people harvesting grapes and making wine on the walls of the tomb of a XVIII dynasty astronomer called Nakht.Barley is often seen sprouting from the belly of the dead god, and from the New Kingdom onwards every bodily liquid conceivable created a connection between Osiris and the waters of the Nile. Although it’s not supported by the most recent archaeological findings, my favourite theory for the birth of beer is that someone forgot barley in an underground silos, and then the flood of the Nile came. The barley was submerged in water, the extreme heat did the rest. And when people came back to the fields, someone opened the silos and went like “shit, we forgot all the barley!” And they found the one who was responsible, and they told him he had to be the one to go down and clean all the messy, gruely grub. And the guy emerged rather happy from his chore.

Beer was (relatively) easy to make, and barley itself didn’t require much effort: more than anything, it was exposed to the fair chance the Nile wasn’t going to be generous, hence connecting it with the need of praying Osiris to provide enough nourishment.

Vineyards, on the other hand, were not happy to grow on the banks of the Nile. Though a certain Canaanite influence can be theorised, it must not have been easy to produce wine. This seems to be supported by the fact that, if beer is depicted as a thing for everyday life, wine is either a beverage to placate the gods or a drink promised to the pharaoh in the afterlife.

So, basically, Osiris makes barley with his body, waters it himself and makes beer, but it took one eye and a few tears to make wine in Egypt.

November 23, 2023

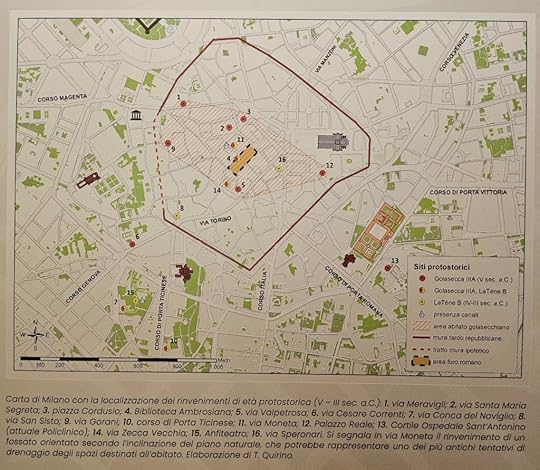

Mediolanum and its Waterways

As my followers know, especially those on Instagram, I’m partial to water bodies: give me a river, a lake, a channel or the sea, and I’m a happy girl. As such, I couldn’t turn down to go and see the recent exhibition on Milan and its Waterways, closing next March and curated by a bunch of universities around the city.

The exhibition is in Milan’s Archeological Museum, and it’s a small place, they have close to nothing, but they try their damn best, okay? It focuses on the millenary history the city has with waterways, on the importance water had in forming the shape of today’s city, and on the role these waterways had in the city’s growth.

It’s divided into 7 sections:

Water and the early urban phases of the city;Water regulation and water as a resource to be managed;Water and crafting;Water in the late imperial era;Water in houses;Sacred water;Water after the Roman era.Many of the pieces you can find in this exhibition come from recent excavations, meaning they came from contemporary people who were minding their own business and trying to build an underground parking or line 4 of the tube. A couple of excavation sites were particularly significant for this exhibition: one between Santa Croce and via Calatafimi, in the Ticinese district and not far from where today’s surviving harbour rests, and the other one in Piazza Meda, on the border between the city centre and the fashion’s quadrilateral, where traffic had been stuck for years, and now I guess I know why.

“Water is the best of things.”

– Pindaro, Pitiche I

Silver cup with a fisherman and marine animals (II – III century AD). The central part of the bowl shows an elderly fisherman sitting on a pier, with a basket behind him. Around him, a plethora of fishes, snakes, shells, crustaceans and animals. Particularly striking is the figure of a wading bird, holding a dragonfly in its beak.Water and Milan’s Origins

Silver cup with a fisherman and marine animals (II – III century AD). The central part of the bowl shows an elderly fisherman sitting on a pier, with a basket behind him. Around him, a plethora of fishes, snakes, shells, crustaceans and animals. Particularly striking is the figure of a wading bird, holding a dragonfly in its beak.Water and Milan’s OriginsThe oldest sources referring to people wandering around in the big bad swamp we now call Milan come from the Bronze Age, around 1600 B.C., but the first attested settlement is from the V century B.C. and they’re connected with people called Culture of Golasecca, a group of Celtic folks who mysteriously liked it wet and decided to settle between the Sesia and the Serio rivers. Which is frankly hilarious if you think that “golasecca” literally means “dry throat”.

This group of people started working a pivotal role in the trades taking place between people up that way and people down the other way, between all those guys left and all those people right. The settlement soon had to be reorganized to better serve its purpose of connection between the trades taking place by land and the water routes.

More people started coming in, more people started roaming around, the Romans came in they had a one-track mind. The next thing you know, water isn’t a means of connection anymore.

A Ring of Water to Defend the CityAfter the Romans came sweeping in and conquered the ass of people who were just minding their own business, the settlement then known as Medilanum was reorganized and, between the II and the I century B.C., it started showing signs of being encircled by a demarcation line. Roman urbanistic doesn’t like blurred lines.

Of course the picture is crooked: I took it.

Of course the picture is crooked: I took it.Starting from 49 B.C., Rome gave citizenship to every person in the region known as the Cisalpine Gaul, de facto removing its status of mere province and incorporating it into Italy. Milan started developing into a “proper Roman city”, which means it needed defensive walls. These walls were around 2 meters wide, between 7 and 9 meters high, and they were developing for around 3,5 km, surrounding an area of approximately 70 hectares.

Different gates allowed entrance into the city: the only surviving portion is a tower in the medieval Porta Ticinese, close to my house.

Walls are nothing without a moat, though, and this one was fed water by the Seveso and the Nirone, connected by artificial channels. Traces of these channels, and the arched bridges crossing them, have been found all around the city. In some places, the moat had to be regimented through cementitious retention walls or wooden piling works.

A Roman WaterwayOnce upon a time, a guy was just trying to build an underground parking lot between Via Calatafimi and Via Santa Croce. Since we’re at the archaeology museum, you can imagine it did not go well: they found a piece of a large artificial channel with wooden piling going 3 meters deep, a stone quay and a third order of piles possibly working as breakwater or docking poles for boats. The wood was dated to the 1st Century A.D., and it was only the tip of the iceberg. By continuing the dig, archaeologists found a shitload of coins, and those have many wonderful qualities: they aid you in buying stuff, of course, but they also have a date stamped on them. These were minted between 39 and 98 A.D., attesting that the pier had been in use at least between those decades.

The pier was later interred on purpose. We know this from finding signs that significant portions of the quays were removed and the channel bed transformed into a landfill. This probably happened around the 3rd Century A.D.

From written sources, we can imagine this happened during a change of destination for the area which Landolfo Seniore, in his XI Century Historia Mediolanensis, calls Vettabbia.

Reconstruction hypothesis.

Reconstruction hypothesis.So far, we have testimonies of waterways being used for defence and for trade. What’s missing is organized watercrafts, and this is where an inscription from 233 A.D. comes to the rescue.

Dedicated to the craft and honour of one Marcus Celsius Artemas, the marble plaque tells us he was a member of the Collegium Nautarum, the professional guild of ferrymen which had headquarters in Como, Pavia and Peschiera. The painted inscription tells us the plaque was placed when Lucius Valerius Maximus and Cnaeus Cornelius Paternus.

Craftsmen and TradersWaterways were a public commodity, in Roman times, and they were administered by the Government. The River Po had an enormous importance for both people and trade routes, since travelling by foot in a swamp is never advisable, and it led to important Harbour cities on the Adriatic Sea such as Aquileia and Ravenna.

Both Strabo and Plinio attest that industries in Milan were particularly flourishing, especially the wool industry. The presence of carding and weaving factories is confirmed by funerary plaques where we see people selling blankets or heavy cloaks, both to civilian and military personnel, and — a thing that never fails to blow my mind — we have testimonies of woollen blankets especially produced with the purpose of firefighting.

Other factories in Milan included leatherwork and metalcraft.

Do you know what all these industries need?

Water.

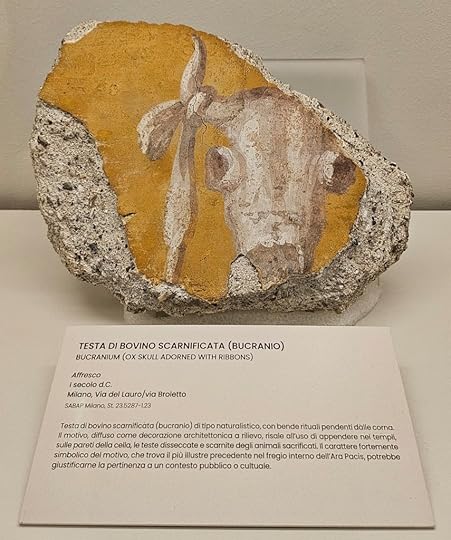

The Imperial EraDuring the Early Imperial Era of Augustus, Milan was a thoroughly Roman city whose importance continued to increase. Renovation works included enlarging the moat next to the defensive walls, reorganizing the square in front of the Forum, building a new theatre and creating a new infrastructure system keeping together both water and landways. This included sewer and more channels serving factories. Local manufacturing soared.

This 1st Century fresco depicts an ox skull (bucranio) depicted with naturalistic attention, with ritual ribbons or bandages dangling from its horns. This was a widespread motif and it came from the (gruesome) habit of hanging the heads of sacrificed animals to the walls of temples and letting them decay there.Water Infrastructure

This 1st Century fresco depicts an ox skull (bucranio) depicted with naturalistic attention, with ritual ribbons or bandages dangling from its horns. This was a widespread motif and it came from the (gruesome) habit of hanging the heads of sacrificed animals to the walls of temples and letting them decay there.Water InfrastructureWater was being distributed through lead pipes called fistulae and they were fabricated by specialized craftsmen called plumbarii. A flat plate of lead was created by pouring metal on a refractory material made of clay or stone, and was bent or moulded into a cylindrical shape while it was lukewarm. The surface had inscriptions of district names, of the craftsmen who constructed the pipes or of other people of interest.

Piping was produced out of other materials too, like bronze, clay, stone or wood, but lead was considered a favourite material because it melted at a very low-temperature point, it was resistant, and it was easy to mould. Unfortunately, it’s also toxic as hell and causes a nice little thing called lead poisoning.

I guess we all have to die eventually.

“If you carefully consider the abundance of water this infrastructure gives to the community (baths, pools, channels, houses, gardens, country villas) and the distance water covers, the arches that have been built, the galleries that have been excavated, the gorges that have been flattened, we will have to admit that nothing grander has ever been built in the entire world.”

— Plinius, Natural History

Aqueducts are the grandest of engineering works performed by the Romans and a signature mark wherever they have been, from Spain to Turkey. Water arrived in the city and was collected into big tanks called “water castles” (castella aquae), and then was brought through walls. It took bronze connections called calices, terracotta pipes (tubuli) and those beloved lead pipes (fistulae) I was talking about before.

One of the major sources we have on water management in Roman times is De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae by Sesto Giulio Frontino, curator of waters in 97 A.D. The treaty provides us with several technical, legal and administrative details.

In the republican age, water management was divided among various magistrates. The censors were in charge of the construction and maintenance of the aqueducts, as well as supervising the supply of public utilities and the concessions (or sale) to private individuals; the latter two functions were also attributed to the aediles. Quaestors, on the other hand, were entrusted with revenue administration (rent taxes, fines, expenditure control, etc.), while praetors handled legal disputes.

Unfortunately, the myth of a fully functional state in Roman times is not accurate: not all waters were public, in fact, and smaller rivers, lakes, reservoirs and conduits could be either state or private. The right of ownership of water also depended on the status of the land in which it flowed.

In the Augustan age, curatores aquarum such as Sesto Giulio Frontino were chosen by the emperor and established to be in charge of every aspect, from the technical to the administrative, from financial to legal matters. Dependent on them were various workers: the castellarii (for the supervision of the water distribution basins); the circitores (who supervised the construction sites); the vilici (in charge of measuring and marking the pipes).

Statal activity was accompanied by local initiatives, supported by city councils or wealthy private citizens who financed the construction of fountains, pipelines or maintenance work in order to gain visibility and political prestige. Pliny the Younger, just to name one, donated 200,000 sesterces to Como, his home town, for the maintenance of the thermal baths over there, and put 200,000 sesterces on top of them for special decorations.

An incredible piece in the exhibition is a water pump in tender oak wood and lead, found at the bottom of a well and usually preserved at the Museum of Natural History.

This is an exceptional finding: only 19 of these artefacts exist.

The pumps, which retain the lead pipes but lack the pistons that ran inside them, represent a variant of the hydraulic pump of Ctesibius, an invention usually dated around the 3rd century BC.

They were operated manually by a handlebar connected to the pistons: when one piston ran downwards, the pressure pushed water into the collecting chamber; at the same time, the second piston ran upwards, collecting water in the lead pipe. The alternating movement of the two pistons allowed the collection chamber to be filled continuously and the water was probably carried further upwards via an additional pipe connected to the stump.

Mediolanum was a swamp and people insisted on inhabiting it: it’s only natural for numerous drainage, land drainage and land reclamation works to be documented since the earliest stages of its urbanisation.

These works included both the control of surface water and measures to stabilise the ground and isolate buildings from subsoil moisture.

Works for this purpose are attested even before the Roman occupation, as documented by the findings in Via Moneta, where a ditch oriented according to the inclination of the natural ground may represent one of the earliest attempts at draining the built-up area.

In Roman times, interesting is the use of amphorae, containers for transporting grains and other kinds of food, often reused as building material to improve the soil. The hollow bodies of the amphorae, intentionally perforated, functioned as air chambers that promoted the ventilation of the soil.

Accumulations of amphorae were also used to consolidate the soil, so as to prevent subsidence, in foundations, filling systems and substructures. Fragments of plaster have also been found pressed into layers with the function of insulating against moisture.

A further consolidation system consisted in driving massive wooden piles into the ground under the foundations of imposing structures, such as the Roman theatre. This tradition has continued over time, as demonstrated by the piling beneath the basilica of San Lorenzo, the Spanish walls and the dock. And I have bad news for you: we still do it today.

Milan, as in many other Roman cities, had an articulated water supply and distribution system, accompanied by an adequate sewage system, from the earliest stages of urban planning. At first, it was a modest and local sewage system. It soon became widespread, due to the urban evolution and the progressive demographic increase: the network came to cover very large areas, differentiating the drains reserved for clear water from those for sewage.

The Roman sewerage system is quite reconstructible in the central core of the Roman settlement, where numerous finds have been made between Piazza Cordusio and Piazza Duomo, in the area around the Forum (today Piazza San Sepolcro) and the Cardo Maximus, and in the area of Piazza Missori.

The main canals were often large, real tunnels with internal lining in clay slabs, vaulted roofs and inspection manholes: their orientation followed the ancient road routes, below the road pavements. Other conduits are more modest in size, consisting of terracotta tubules protected by a brick structure bound by mortar.

With the transition to the Middle Ages and the decay of the great Roman hydraulic systems, there was a reversal of the trend and a return to a small-scale organisation, in which each household or social group provided for their own disposal.

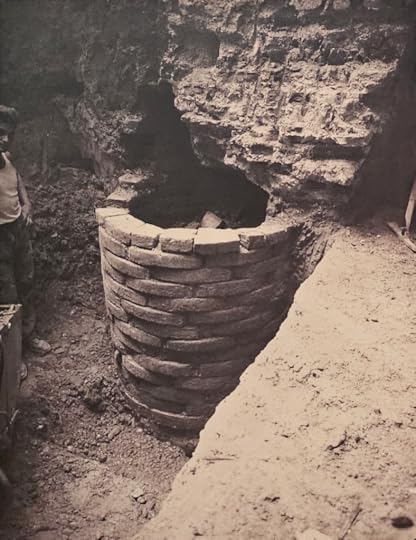

Thanks to the shallow water table, the main water supply system in Milan has been represented since Roman times by the capture of groundwater through the use of wells, found in large numbers in every part of the city. If you want to put it into another way: you dig a hole and water comes up, whether you like it or not.

Exemplary is the testimony of the writer Bonvesin de la Riva, who at the end of the 13th century surveyed more than six thousand wells throughout Milan. That is a lot of wells.

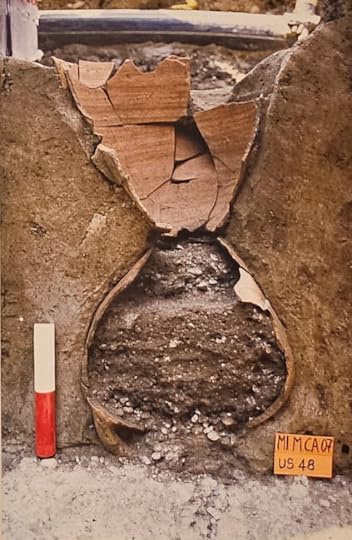

A well excavated near Piazza Fontana, right behind Piazza Duomo.

A well excavated near Piazza Fontana, right behind Piazza Duomo.Easily recognisable by the prevalent use of the characteristic round-arched bricks (pozzali), wells from the Roman period vary in diameter, from 70 cm up to approximately 1.80 metres. The bottom could be closed with compact material, in some cases with a circle or a wooden slab that served to provide a stable and elastic support surface for the entire artefact.

As a rule, wells were constructed by drilling cylindrical pits of varying depths in waterlogged soils. Structuring could then be done in a variety of manners, applying the ‘lining’ or ‘sinking’ technique.

The first step in the works involved the excavation of the pit up to the calculated level and the progressive laying of the stone or brick facing, possibly reinforcing the walls with wooden bulkheads.

The second step entailed a shallow excavation and the placement of a wooden ring with a stabilising function: on top of the wooden ring, the stone or brick structure was piled up to a height well above the floor level, and after excavating the bottom from the inside, the entire structure was pushed downwards, repeating the operation up to the desired depth and from time to time reconstructing the upper part of the masonry.

That’s called top-down construction and it’s considered revolutionary. Can you believe it?

Surviving Roman wells were often reused in later periods, as documented by the medieval and sometimes Renaissance materials found in them.

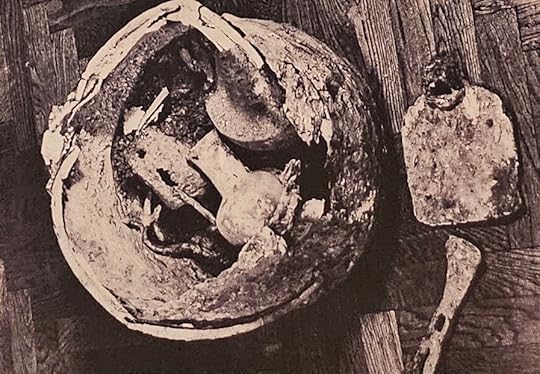

A well excavated in Corso di Porta Romana.

A well excavated in Corso di Porta Romana.Between the 3rd and 5th centuries, we witness a phase of political and social instability. As early as the second half of the 3rd century AD, various foreign people penetrated the territory of the Roman Empire on several occasions, returning favours the Roman Armies had dispensed for centuries across the alps and plundering areas of central and northern Italy. These incursions were followed in the 5th century by veritable migrations of folks, with the occasional violent episode such as the siege of Rome in 410 by Alaric at the head of the Visigoths, the arrival of Attila around 451, and the settlement of the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric in 489. We were just in the middle of the highway and we couldn’t hope to escape: around 538 the Ostrogoth Uraia besieged and sacked Milan.

In this climate of uncertainty, the local populations abandoned their homes and objects considered valuable were hidden in the hope of recovering them later. Chosen as secret repositories are — you guessed it — wells, which become perfect hiding places.

Well excavated in Via Speronari.

Well excavated in Via Speronari.At least three wells in Milan stored precious objects that their owners never recovered: a well near the church of Santa Maria presso San Satiro in Via Speronari (excavated in 1959), a second well found in Via San Raffaele during the construction of the Rinascente Store (excavated in 1949) and another in Via Santa Maria Fulcorina (excavated in 1985). The materials found included various objects of use, coins, copper and bronze containers. Metal vessels were considered valuable, as they were long-lasting objects, often preserved and used for several generations.

In general, the materials were found piled up on the bottom; it is therefore probable that the pits were still in use at the time of the burial.

Close-up of the materials found during the excavations near San Satiro.Water and CraftsmanshipCeramic production

Close-up of the materials found during the excavations near San Satiro.Water and CraftsmanshipCeramic productionThe basis for producing a ceramic object is clay, whose name in Greek was κέραμος (kéramos), meaning “stuff that’s good for pottery”. This, in turn, is thought to come from κεράννυμι (keránnumi, “to mix”), but that’s highly debated.

What’s not up for debate, however, is that this one is a cute elephant.

What’s not up for debate, however, is that this one is a cute elephant.In its natural state, this material is not directly usable and must undergo several processing steps such as purification, modelling, drying, and baking. In Roman times, these activities were mainly carried out in specialised workshops that required, among other things, abundant and readily available water sources to function and stay safe. That’s where our waterways come in.

The waterways were also a transport route for the distribution and sale of finished products.

The remains of a kiln for the production of ceramics have recently emerged in the area in front of the Sant’Eustorgio basilica: the structure, which has yielded functional and discarded ceramic material, was located near the watercourse between via Calatafimi and via Santa Croce, from which come battered or deformed ceramic fragments, matrices (moulds) for oil lamps and for the decoration of terra sigillata crockery and clay vessels used in the construction of kiln vaults.

MetalworksThe earliest traces of metalworking in Milan date back to the Celtic oppidum, but it was especially during the 2nd century that this activity acquired an increasingly important role, characterising the city’s physiognomy. The metallurgical technology of the time did not presuppose the use of hydraulic motive power, which would have been widely exploited in the Renaissance period, but water was nonetheless indispensable in many processing stages.

The production district that emerged from the excavations in Via Moneta, in the heart of the first settlement and active mainly in the 2nd century, testifies to how early metalworking was developed in the city.

Minerals and raw materials were not processed in Milan, but only refining metallurgy was carried out there: through the waterways of the iron and steel centres in the area (Poltello-Rodara area), ready-processed goods arrived to be transformed into finished artefacts that were then marketed.

Iron forges were found in Via San Vincenzo, and along the main access roads, e.g. in the western area, in the courtyard of the current Catholic University (late 1st century BC). Later, the area of Porta Romana and piazza Erculea became a real ‘industrial hub’ for large-scale production of brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) used in furniture objects and mirrors. This was highly specialised workmanship, which in the

imperial period found comparisons only in Germany and Gaul, and for brass, in Britain. Milan obtained zinc supplies from the nearby Bergamo mines, as Pliny the Elder informs us: even the late antique mints needed water for some stages of gold coin production, and Milan could provide it in abundance.

One of Mediolanum’s most developed manufacturing activities was the tanning of hides destined for various applications, as can be seen from inscriptions mentioning shoemakers and leather merchants.

The most famous testimony of a leather craftsman is probably the so-called Lambrate Sarcophagus (above), dated between the end of the 3rd Century and the beginning of the next and discovered in March 1905 during some excavation works in the area.

These testimonies have recently been enriched by the archaeological finding of a processing plant in Piazza Meda.

In the 1st Century A.D., an articulated tanning complex occupied this district to the northeast of the city, cleverly and significantly outside the walls because tanneries smell and pollute.

The abundance of water, essential in all tanning operations, also influenced the choice of this district, close enough to the town and in communication with the area towards Bergamo and Brescia.

The tanning facilities found in the excavation belong to a complex with at least three well-equipped workshops, which, due to their extensions, take on the character of a proper leather industry. This might be the first actual factory found in Milan. Look me in the eyes and tell me this isn’t a big deal, and I’ll punch your nose through the back of your skull.

The western workshop, which is better preserved, comprised two rooms opening onto a large courtyard with a central masonry tank served by a lead pipeline. Inside the rooms were two rows of underground wooden vats in which hides could be treated with vegetable substances (tannins) by being immersed for long periods. The tannins prevented the hides from rotting, believe it or not.

Six additional vats were buried in a double row in the courtyard under a roof, separated by a drainage channel for water. In the open air, the many operations of washing and finishing the hides took place without people collapsing and dying, which was considered more of a priority than it is today.

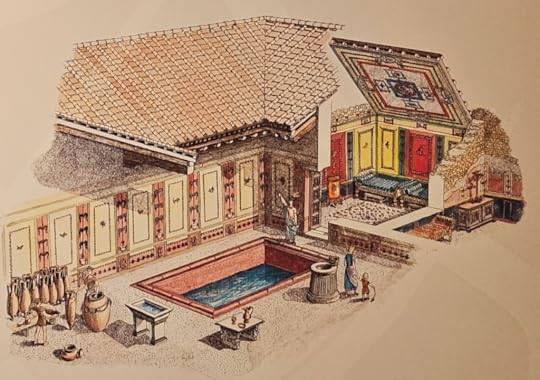

Visual reconstruction of the tannery.Capital of the Empire

Visual reconstruction of the tannery.Capital of the EmpireWe don’t like to talk about it, but Milan was the capital of the Roman Empire from 286 onwards, when a guy called Maximian decided to come and live here.

“In Milan everything is worthy of admiration, there is a profusion of riches

and there are innumerable stately homes… The city has expanded and is surrounded by a double circle of walls; there is the circus, where the people enjoy shows, the theatre with its wedge-shaped tiers of seats, the temples, the fortress of the imperial palace, the mint, the district named after the famous Herculean baths… Its buildings appear one more imposing than the others, as if they were rivals, and not even its proximity to Rome diminishes its greatness.”

— Ausonius, Ordo urbium nobilium

As you might imagine, this meant the city underwent a series of critical urban changes, first and foremost the extension of the fortified city wall and its moat because a lot of time had passed but the Romans still had a one-tracked mind.

The city walls came to incorporate new areas to the east and west. Along the north-eastern boundary, a residential and commercial quarter developed around the Porta Orientalis and was called the Regio Herculea, which also included the city’s largest bath complex. The imposing structure (15,000 square metres) stood between today’s Corso Europa and Corso Vittorio Emanuele, and was located near the moat and a branch of the Acqualunga fontanile. This, in turn, entered the city at the Porta Orientalis, and flowed along today’s Corso Vittorio Emanuele in the direction of the area later occupied by the Episcopal complex.

As you can easily guess, water is pretty important if you’re trying to run a public bath.

In the western quarter, the new section of wall encloses the circus, the new performance building connected to the imperial palace.

A horreum, a large storehouse of food for military troops and the court, was also built along the road axis to Novum Comum (Como), not far from the moat.

You have to decide whether you want thermal baths or tanneries, from an urbanistic point of view, at least you do if they’re growing in the same district. And when it comes to the Romans… well, you can always trust them to pick their thermal baths.

In the 2nd century AD, the expansion of the city into the suburban areas led to the progressive contraction of the activities of the tannery complex, which finally came to an end at the end of the 3rd century A.D.

The extension across the northeastern sector of the defensive wall initiated a process of major urban transformations throughout the district, which, from being a craft-productive area, took on a residential and commercial character.

The same old story.

The dwellings facing the two intersecting streets of the area were enlarged and enriched with frescoed porticoes, surviving in a large portion of walls found on the via S. Paolo and dated to the Constantinian period (early 4th century). The gravel streets, equipped with sewage services, reveal repeated maintenance work due to the heavy traffic. The commercial vocation of the district was maintained even in later periods (12th-13th centuries), which documented the persistence of the road layout and urban fabric, with buildings and shops equipped with wells, cisterns and iceboxes. No more tanneries, though. As I already mentioned, they smell.

Leather-related handicrafts seem to have been concentrated, since the Middle Ages, in the southern part of the city between Piazza Vetra and the Ticinese.

Which is where I live.

Cheers!

The construction of the Herculean Baths was part of a more articulated urban planning project to redevelop and enlarge the city, chosen as the imperial seat by Maximian in 286 AD.

The exceptionally extensive facilities occupied an area of approximately 14,500 square metres, currently bounded by Corso Europa and Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, corresponding to the northeastern part of the city and not far from the Porta Orientalis.

A monumental entrance on the north side gave access to the gymnasium, consisting of a large courtyard surrounded by a colonnade. On the same axis we found, in succession, the frigidarium flanked by two rooms interpreted as dressing rooms, the tepidarium (medium-heated room) and the calidarium (high-temperature room). The rooms were heated by injecting hot air below the floors, which were raised on small columns made of circular bricks (suspensurae).

Water in Private HousesWater played a central role in private homes of Roman period, both for strictly functional and service purposes and, in the case of the most prestigious residences, for recreational purposes. Just as it happens today.

As far as the utilitarian aspect is concerned, recurring is the presence of wells intended for the collection of groundwater, sometimes flanked by underground cisterns or by special tanks located within gardens and porticoed courtyards, designed for the collection and conservation of rainwater.

A rainwater well, for instance, came to light in the Domus discovered in Via Cesare Correnti in 1992.

Excavations of the main pool in via Cesare Correnti.

Excavations of the main pool in via Cesare Correnti.In the absence of such installations, the water needed for the most common domestic needs had to be drawn directly from public fountains, which were widespread throughout the city.

Running water was common only inside the wealthiest homes, though it was lead-flavoured as we have seen before. In such cases, it could also be used in private baths and thermal areas for the care and well-being of the body, but also in accessory apparatuses such as fountains and nymphaea intended to satisfy the aesthetic and artistic taste of the owners.

Visual reconstruction of the house.Fountains and Nymphaea

Visual reconstruction of the house.Fountains and NymphaeaIn addition to installations for functional purposes, in residences of greater value and wealth, water could also be widely used within more or less articulated ornamental apparatuses, such as fountains and nymphaea, in which a generic practical purpose was accompanied by a more targeted search for aesthetic values and the fulfilment of artistic demands.

If fountains could be adorned with sculptures, nymphaeums offered the possibility of deploying more complex settings, both architecturally and decoratively, enriched with mythological subjects often set in a natural context.

Installations of this kind derive their origin from natural places consecrated to the cult of nymphs, and they were destined for convivial encounters and rest, cheered by the constant flow of water within aediculae decorated with mosaics or shaped in imitation of small caverns and grottoes overlooking gardens.

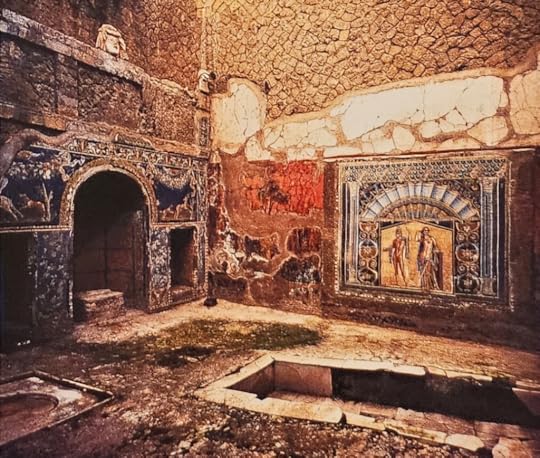

The most famous and better-preserved nymphaeum is the one in Ercolanum.

The most famous and better-preserved nymphaeum is the one in Ercolanum.In Milan, remains of probable nymphaeums belonging to luxury residences were brought to light during excavations conducted in 1950 in the area of Piazza Borromeo and in 2012 in Piazza Fontana.

Eaves and GuttersGutters and eaves of course had the function of collecting and draining water from the roofs, but in the pre-industrial era you could expect stuff to be charming too. Rainwater was piped into special collection tanks located in the peristyles (courtyards), and those were not particularly charming even in the pre-industrial era.

Primarily made in moulds, eaves took different shapes: comic or Silenian masks, animals, and especially dogs which recalled the role of the guard, protecting the house and warding off evil spirits. Or it’s simply that Romans liked puppies just as much as we do.

Sacred WaterAs in many other cultures, Roman civilisation linked springs and running water to the concepts of regeneration, purity and sacredness. Springs are a valuable thing when you don’t have bottled water, and they were consecrated to nymphs or considered works, property or residence of a local deity, especially where thermal waters were concerned.

Water, as an instrument of physical and spiritual purification, is present in various rituals that mark the life of society and the individual: birth, marriage, funeral rites.

It is also an indispensable instrument of purification in cases of bloodshed: Aeneas, fleeing from Troy, asks his father to carry the sacred images and the Penates until he has purified himself from the carnage wrought in battle by washing himself in the river.

Upon entering a sacred space, the citizen had to either wash his entire body or just his right hand, depending on the level of involvement and the rite in question, and they did so in special basins placed at the entrances of the temple areas.

Washing one’s hands before the ritual slaughtering of an animal was an essential act, and this purification also involved the sacrificial victim, the instruments used and the participants in the ritual, all of which were purified by sprinkling water with branches.

Finally, water is present in the geography of the underworld, where it demarcates the passage between life and death and forces the deceased to undergo one final rite of passage, the paying of Charon and the ferrying across the Acheron.

Because the Romans had common sense above pretty much everything else, necropolises were located outside the urban perimeter, and Milan was no exception. Some necropolises have yielded traces of watercourses or artificial canals, which in some cases delimited the burial area itself, and this is less of a good idea, as people in London will find out during their cholera outbreak.

The presence of water in necropolises was probably connected to funerary rituals, as running water was considered an instrument of purification.

In addition to purification practices, water was used for banquets and libations practised during festivities to remember the dead, festivals such as the Parentalia in February and the Lemuralia, held in May, meant to exorcise the angry spirits of those who were dead in violence.

On such occasions, liquid offerings such as water, wine, milk and honey were sometimes scattered on the ground or poured into specially made conduits made with perforated amphorae, opposing tiles or lead pipes so that they flowed into the burial. Such conduits are documented, for instance, in the necropolis in Via Madre Cabrini, in the Policlinico area and the Catholic University’s courtyards.

An example of amphorae conduits to channel liquid offerings to the dead (found in Via Madre Cabrini).

An example of amphorae conduits to channel liquid offerings to the dead (found in Via Madre Cabrini).Milan practised both cremation, prevalent until the beginning of the 2nd century AD, and inhumation, which became widespread with Christianity as many other bad ideas. The objects placed in the tomb to accompany and protect the deceased in the afterlife include glass and ceramic containers, oil lamps, coins and, on rarer occasions, toiletries and objects with a magical protective function.

November 22, 2023

#ChthonicThursday: Sokar

Sokar was the ancient god of the cemeteries in Memphis and became god of a death seen as a transformative process, the middle ring of a cycle that started with Ptah and ended with reborn Osiris.

Alongside Apophis, Anubis, and other Egyptian-inspired characters, Sokar is also a character in Stargate and comes from the Goa’uld, the main villains and dominant race.

He’s this week’s Chthonic Thursday deity on my Patreon.

The Marvels

I haven’t done a movie review in ages, but… what is wrong with you people? Seriously, what the fuck is wrong with you?

The Marvels is a perfectly regular piece of superhero fiction: it’s a light-hearted story with cosmic fights, a villain that could have been better, good sidekicks and a good dose of both humour and drama.

If you google it, though, the first five results are backlashes: MovieWeb, both GameRant and ScreenRant, CBR all doubled-down on the fact that the movie is a mess, and that director Nia DaCosta is either incompetent or was absent during production. They’re all one stone’s throw from suggesting she couldn’t work on the movie because she had to buy groceries and go breastfeeding random children.

Some of my usual movie companions didn’t come to see The Marvels because they heard the movie wasn’t good from these and other “reliable” websites.

Now, let me give you an intriguing piece of information if you will: MovieWeb is owned by a company called Valnet Inc. GameRant and ScreenRant are both owned by a company called Valnet Inc. CBR, an acronym that stands for Comic Book Resources, is owned by… yes, you guessed: a company called Valnet Inc.

So maybe it’s time you start thinking for yourselves.

In the best-case scenario, you are paying heed to content published by a company that has often been criticised for having no quality check and for pursuing click baits.

In the worst-case scenario, you are all listening to one person.

You might as well listen to me.

The CharactersThe titular trio is made up of Carol Danvers (Captain Marvel in the movies, Ms Marvel in the comics, which always causes me to mess up when I talk with friends), Monica Rambeau (no superhero nickname) and young Kamala Khan (who takes up the nickname Ms Marvel in honour of her idol). The first concern nowadays always is: how many other movies and tv series do I need to see in order to enjoy this one? Very little, in my opinion.

the first Captain Marvel movie is enjoyable but it’s not necessary. All you need to know is that Carol lives in space, has powers and once fell into “a disagreement” with the super artificial intelligence governing the alien race of the Kree: the movie provides enough framing for that;no Avengers movie is necessary: all you need to know is that there’s a guy called Nick Fury, he’s a director of some governative agency, and he’s a cool guy. The movie provides enough framing for that;no tv series is necessary, not even Ms Marvel, and I know this for a fact because I didn’t see it: all you need to know is that she has a magic bracelet, and the movie provides enough framing for that.I knew and loved Carol from the previous movies, and she doesn’t disappoint, though she occasionally offers a softer and more human side than she did in her titular movie. I didn’t care much for Monica, probably because Wanda Vision hasn’t been my piece of cake, but she’s a tough, relatable, rounded character with depth and nuances. The biggest surprise has been Kamala, because I usually dislike teen characters (and that’s why I didn’t see her series): the character isn’t banal, she’s a well-written teen without the usual stupidity writers inject into a teen, and the actress is outstanding! She’s good enough I might actually go back and watch her series.

Now for the weak part and, as it often happens, it’s the villain. Do you remember Lee Pace in the first Guardians of the Galaxy? No? Well, that’s normal. He was playing one of my favourite characters in the comics, Ronan the Accuser, a guy who showed unexpected depths. In the comics.

In the movie, he was just a guy who had issues with people. Which issues? Which people? We’re told in passing, but we actually don’t know. Something about a war that has been dragging on for centuries.

Unfortunately, Zawe Ashton‘s Dar-Benn has the same problem: she’s also an accuser, or at least she has the hammer for it, and she has issues with people for reasons we know, we see in passing but fail to create any emotional attachment. And it’s not the actress’ fault: Ashton is intense, her look is on point (dental work aside), and her gear looks natural. The movie could have used twenty minutes more of suffering Kree, possibly at the beginning, to ground this idea that maybe Dar-Benn is right and Carol really is at fault when she rushed into a civilization and destroyed a piece of it without anybody’s consent.

Ooopsie-daisies! Spoiler alert.

Ooopsie-daisies! Spoiler alert.Also, if you’re curious, Dar-Benn was a Kree general in the comics too, but he was a dude. He created a robot of the Silver Surfer and he was killed by Deathbird during the Kree-Shi’ar war. Who are the Shi’ar, do you ask? They’re birds and Charles Xavier has a kink for them, so let’s hope Marvel Studios never remember their existence.

These are the Shi’ar. Hope they stay in the comics.

These are the Shi’ar. Hope they stay in the comics.The other supporting characters all put in an honest day’s work: Nick Fury is a dispenser of laser shots and good advice (especially: “Okay, no more touching shit. Especially glowing, mysterious shit”), Kamala’s family is solid and funny but never to the point of becoming grotesque, Valkyrie makes her glorious cameo and… there’s no one else. It’s a tightly packed movie, no drooling of extra characters just for flavour, which should increase its chances of being liked by people who don’t want to study for hours before going to the movies.

The Plot TricksBe careful, spoilers ahead.

The main plot trick employed is one: the activation of Kamala’s second bracelet, found in space by Dar-Benn and her minions, causes a random entanglement in the trio’s powers and they switch places each time they use them. Also, Dar-Benn is using her bracelet to rip new a-holes to the space continuum and funnel resources into the atmosphere of her dying planet.

Only one of these two is really a theme (and not really explored in depth): even though the switching places could have led to an exploration of what it means to walk in someone else’s shoes (a supposedly indestructible cosmic hero, a black woman, a Muslim teenager), the movie chooses not to pursue this road and opts for a lighthearted approach.

The ecological subplot is also not really a subplot: the Kree have destroyed themselves with war, but the movie doesn’t try to push any deeper message.

Which brings me to my main objection.

How is this movie “woke”?

There are literally no social themes in this movie. None. Nothing. Zilch.

It’s a regular superhero movie, not better nor worse than Ragnarok or Spider-Man, you could take the characters and replace them with dudes and it wouldn’t change much.

Literally.

Literally.So, honestly, what are y’all whining about? Take a good, hard look in the mirror and recognise that you’re complaining because there are women in your superhero movie.

My superhero movies have been filled with dudes for ages: I think it’s time we take turns.

One of the other controversies has been that there seems to be something off with the montage, and I have to agree here. In particular, there’s a fighting sequence in which Kamala is sporting her superhero suit: next thing you know, she’s falling from the sky in her civilian clothes. Something went awry in post-production, for sure.

Is it reason enough to trash an enjoyable movie? Honestly, we all know it isn’t.

November 21, 2023

400 centuries of folding screens

In my endeavour not to spend my days in misery, last Monday I went to Fondazione Prada here in Milan to see their new temporary exhibition: Folding Screens from the 17th to the 21st Century. It’s the kind of thing I would have visited when I was more into design, and yet I enjoyed it for many reasons.

The ConceptThat of fhe folding screen is thus a story of cultural migration, hybridisation, collaboration and what this object conceals and reveals, retains and unfolds. This story, and especially the way it manifests itself in the present, is a narrative of liminal objects and the very concept of liminality: being between one thing and another, literally and metaphorically, undermining the rigid distinctions and hierarchies between different disciplines, art and architecture, decoration and design.

I’ve always been partial to folding screens, no doubt under the influence of one of my first employers: Italian design and architect Piero Lissoni.

He used folding screens a lot, in his interior design, especially in public places. I mostly worked on the construction of hotels: designing and finding folding screens was always one of the most delicate and intellectually stimulating parts of the job, as odd as it might sound.

I did not design these, technically, but I’ve always been partial to them.The Setting

I did not design these, technically, but I’ve always been partial to them.The SettingThe exhibition takes place on two levels in the so-called podium of the complex and it’s designed by SANAA, as you immediately guess by taking a look at the curved glass partitions and sinuous sets of curtains.

Regardless of how fed up you might be with this signature style, especially if you walk past the Bocconi campus every day, there’s one thing you have to admit: at the ground level of the podium, SAANA was able to create an intriguing itinerary in what would have otherwise been a banal and rectangular room. They create screens inside an exhibition on folding screens. How avant-guard.

Alas, the second level is far less interesting but then, you can’t see it from the street: you only see it if you’re actually interested in the exhibition and this is Fondazione Prada after all.

The exhibition has six sections on the ground floor:

“Readings, East and West”, reflecting on how you read a folding screen depending on the culture and significance: from left to right, the other way around, front and back, top to bottom;“Public / Private”, highlighting how folding screens have traditionally been used to create intimate spaces and how this gives the object a sensual, sexual and erotic connotation;“Split Screens”, melts the physical world and the digital experiences;“Four Seasons: Space and Time, Figuration and Abstraction”, looks at the folding screen as a storytelling medium;“World of Interiors” looks at the folding screen in its primary function: a piece of furniture;“Parody / Paradox”, looks at transparent screens that do not seem to fit their purpose and often employ irony to highlight social paradoxes.At level one, the exhibition takes a chronological approach instead of a theme-based one.

My top 10 in the exhibitionIt would be madness to list all the pieces one by one. Still, there are so many that I can hardly command myself to resist the urge. It has been hard to shrink it down to just 10.

10. Goshka Macuga, In Time or Space or State (2023)The screen is created by bookshelves and the symbolic division of a metal detector, of a security gate. Israel and Palestine, Russia and Ukraine, China and Taiwan are on opposite sides of the screen, in an expressive gesture that clearly wants to express a relatable concept and yet I can’t help but question it intellectually, as the division between Israel and Palestine are far from being the same as Russia and Ukraine.

Still, if the idea is to tear the bloody thing down, I couldn’t agree more.

Portuguese sources from the XVI century claim that, in 1543, a ship trading through the South Chinese Sea was thrown off course by a typhoon and ended up in the Japanese archipelago. Civil war was raging in the area, piracy had led the Chinese government to stop all sailing, and the Portuguese saw an opportunity to broker a deal between the struggling China and the rich Japanese merchants. This movement eventually led to the Portuguese settlement on the coast of Guandong, where they could make a port between Malacca and Japan. This port will be known as the city of Macao. This anonymous Chinese screen from the second half of the XVII Century is one of many showing Westerner ships in an oriental style.

Another wooden painted screen from the second half of the XVIII Century comes from the Oriental Art Museum in Lisbon and it’s absolutely delightful, much more to my taste than the two massive golden screens placed in front of it. It shows a view of Macao, meticulously depicting the Portuguese monuments, while on the other side we find Canton, with the Lui-rong pagoda, the Mohammedan minaret and the triumphal arc. The piece was probably commissioned to document the Portuguese influence in the region, but the particular choice of framing and composition makes this a vibrant piece on the reality of colonialism.

A third glorious Japanese screen from the XVIII Century, coming in through Portugal, depicts the very western ship that would probably bring back the piece during the period in which relationships between Japan and Portugal were more open.

8. Chen Zhifo, Seasonal Flowers and Birds (1947)Another favourite of mine in the exhibition, this Seasonal Flowers and Birds is from 1947 and represents the classical theme of seasons, using a technique called gongbi that involves highly detailed brushstrokes and an abstract quality to the composition.

7. William Morris (panels: 1860, screen: 1889)Designed on a project by William Morris but embroidered by Elizabeth Burden, sister-in-law of the artist, and by his wife Jane Morris. The subjects of the screen are three heroines: Lucretia (I wrote about her here), Hippolyta queen of the Amazons, and Helene of Troy. The three women embody three different sides: strength in the face of ordeals, active power and the more passive power, if you will, of beauty intertwined with fate.

6. Man Ray, Les Yeux Fertiles (1935)Dedicated to Faili Elliard, the folding screen is inspired by one of his poem and depicts a young woman, posing as a Venus but deprived of her right to show a face. A plethora of red glowing eyes draws the line of a fictional hill on her right, going down into the sea, while on the left a group of hands rise from a fountain.

5. Lê Phổ, Paysage du Tonkin (1932-34)

Amidst the production of this Vietnamese painter, the screen on display is possibly the largest and certainly unique in its employment of lacquer.

It’s said the geometrical elements were inspired by Jean Dunand, a Swiss and French Art Deco painter who worked as a decorator in Paris and whom Lê Phổ saw at the Colonia Expo of Paris in 1931. Through Dunand, Seizo Sugawara is an indirect influence and this is why we have this perfect mixture of oriental, geometrical and decorative art.

4. William N. Copley, Konku (1982)Also known as CPLY, William N. Copley was an American Surrealist painter, writer, publisher and entrepreneur, precursory to Pop Art. He produced many folding screens and this Konku (1982) is part of a series denouncing the stereotypical distinction between “good” women and “bad” women, ofter using the figure of the prostitute as a paramount example: a role required by men, and yet judged and denounced by those same men.

The back of the screen is a flat pattern, with the writing “men” and pointing fingers both signifying direction and accusation.

On the front, figures of women in their lingerie are placed half-in and half-out, like a decorative motive of classical times, and significantly without a head nor a face.

3. Lorna Simpson, Screen 4 (1986)Her Screen 4 (1986) is part of a series denouncing the sexualization of black women. In the words of Bonita Mclaughlin as quoted by the curators:

“Simpson draws attention to the emphasis and sexuality that often accompanies representations of black women, simply by omitting it. Showing herself with her arms crossed, or resting on her hips, or stretched along her sides, and wearing a common, loose, crumpled white pinafore, Simpson’s model chooses not to please or attract. The gap between her reality and the desire for eroticism inherent in the male gaze is evoked in the quote on the left panel.”

The writing says: “She was no more exotic than the sparse room she posed in.”

2. Carrie Mae Weems, The Apple of Adam’s Eye (1993)The Apple of Adam’s Eye (1993) is a painted and embroidered screen denouncing gender and role differences in the biblical story of Adam and Eve. The naked body of the woman is completely covered by a veil and it’s a mere allusion.

The front reads: “She’d always been the apple of Adam’s eye”.

The rebellious approach, however, is evident from the quote at the back of the folding screen, which reads:

Temptation my ass, desire has its

place, and besides, they were both

doomed from the star.

The quote is adorned with a falling leaf fashioned like the feather of a cursed angel.

1. Lisa Brice, Untitled (2022)Another potent piece of the exhibition, untitled and made last year, it’s a folding screen painted with different pigments on a simple wooden support and it’s a fierce denounce of patriarchy. In a dark, suffocating interior, a group of different women are gathered and drink, smoke, talk, read, think: all covert activities to the patriarchal society. The clearest denounce is a paintress, in the foremost left panel, who’s painting a new version of Gustave Courbet‘s famous Origin of the World but is doing so in secret, covering herself with a drape and holding between her legs a mirror we cannot see: we are only allowed to see what she represents of herself, and this is one of the strongest assertions of freedom you will find.

http://www.shelidon.it/splinder/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/20231120_153143.mp4Extra featuresI couldn’t feature them among my favourites, but I couldn’t scratch them either. Here’s another bunch of interesting stuff, in sparse order.

Anthea Hamilton, Shame Paravent (2023)Her work, also a very recent piece from this year, is a statement on the very concept of shame through the choices of materials, as it uses oak wood, chestnut husks, rattan, goat wool.

Elmgreen & Dragset, Paravent (2008)“To me, in the idea of the screen, there is an implicit subtext of shame; it is always – in scale and use – in relation to the body. Shame develops in itself and is visual; guilt depends on an external judge and is acoustic. Shame is a revolutionary feeling.”

“My favourite sculpture is a wall with a hole framing the space on the other side.”

– Andy Warhol

Willing alluding to Warhol’s favourite sculpture being a glory hole, this is what the Danish and Norwegian couple propose to us: a scene dripping queerness with two pairs of Levi’s 501 jeans and some toilet paper.

Kenneth Halliwell, Cat Screen (1966)This decoupaged folding screen with quaint figures of cats and (less quaint) figures of Egyptian tragedies is at the centre of a tragedy: it was done by Kenneth Halliwell in his house on Noel Road, in Islington, where he was living with playwright Joe Orton. The couple used to take books from libraries, paste pictures of naked men and cats between their pages and then give them back, so that other readers might find the “surprise”.

No, I do not approve.

Nor do I approve of the fact that Halliwell eventually killed Orton, in August 1967, before killing himself.

Here’s a close-up of the screen.

Hernan Bas, Decorative screen for the foyer of a homosexuals summer home (2012)An astonishing piece, the reverse of Elmgreen & Dragset’s and a style much more akin to my taste: the homosexual aesthetics and identity aren’t explored through the pursuit of the crude.

Golden foil with fading sunflowers and a derelict home on a hill are much better than Levi’s jeans and toilet paper. But then again, I’m not a gay man.

Francis Bacon, Painted Screen (1929)Francis Bacon worked as an interior decorator in Paris between 1928 and 1930, and I have a hard time picturing him in pursuit of chairs, tables and armoirs. Folding screens and carpets are an entirely different matter, and much more akin to painting. They’re decoration, though, and the artist came to loathe the word, so much that this piece stayed hidden in his study for many years.

Giacomo Balla, Screen with Interpenetrating Forms (1932)Giacomo Balla, an icon of Italian futurism and a highly prolific painter produced many folding screens and they’re all in the same style: flat shapes, intertwining one to the other, and more akin to a fashion pattern than to the compositions of his paintings. This screen is no exception.

November 20, 2023

Stories of Samurai Women

The exhibition has been going on for a while, but I’ve been:

depressed;busy with my forced relocation;depressed;busy with looking for a construction crew that can handle the repairing works in my house;depressed;busy with work;depressed;away on a journey.Said journey helped and I’m not depressed anymore (I know, that’s not how it works), plus I have time on my hands because my novel is on hiatus waiting for feedback from beta readers, and I managed to attend the second to last week of the thing.

Stories of Women Samurai is the second exhibition Tenoha dedicates to a book by French illustrator Benjamin Lacombe, the first being a combination of two books I talked about here, and it goes back to the origins of previous exhibitions such as the one on Tokyo Storefronts, with giant reproductions of works by Mateusz Urbanowicz: it’s less ambitious, in a way, with more focused projections and almost no animatronics (and I can’t blame them: they were a maintenance nightmare).

And before I proceed, let me clarify that this is what I mean when I say “less immersive” and “more focused projections”.

http://www.shelidon.it/splinder/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/20231117_164441.mp4I also tried to upload it here, hoping it would adapt it into a horizontal frame, but YouTube is trying to be FuckTok, these days, so shorts can’t be embedded in a web page.

The video mapping is done by the digital creative company Hitohata, and it shows scenes from the city of Okazaki, its history and its evolution into modernity, on top of the reproduction of a samurai armour alluding to Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of a Shogunate which would rule from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Here’s another short from a side angle (and here it is too):

http://www.shelidon.it/splinder/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/20231117_164523.mp4As a general principle, the exhibition is much more focused in lending you stuff so that you can take pictures of yourself in the different rooms, either wearing a kimono, wielding a katana or sporting a fan. Or all of the above.

No, I didn’t do it.

Still, the entrance provides a good decompression room so that you can get into the mood of the exhibition.

http://www.shelidon.it/splinder/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/20231117_164118.mp4Drawings and stories are present too, inside, though they’re much more out-of-the-way, and they managed to concoct an activity even I would enjoy: you can buy a small notebook at the entrance, and fill it with different stamps you can find around the exhibition.

But what is featured in the exhibition? Which are the women in the book? Well, you’re in luck: I was wise enough to keep it out of the relocation boxes.

Onna-mushaFirst of all, in pre-modern Japan there’s a specific word for a woman warrior and it’s onna-musha. They were not wayward women pretending to be men and sneaking into battle: they were proper members of the warrior class (the bushi), and were properly trained to use weapons. Being female guards outside of harems was only one of their fields of employment. In that case, they were referred to as besshikime (women with a different style).

Some of them are considered mythical figures, such as Tomoe Gozen who fought in the Genpei War (1180–1185). Some others’ existence is considered more plausible, like Ichikawa no Tsubone who defended Kōnomine Castle with her ladies-in-waiting during the Sengoku period. For some others, we have actual historical evidence.

Ōhōri Tsuruhime (1526–1543)The first set of drawings is dedicated to this warrior either from the Sengoku period (1467–1638) or the Muromachi period (1336–1573), depending on which group of scholars you stand with. Tsuruhime was born the daughter of a priest, the chief priest of the Ōyamazumi Shrine on the island of Ōmishima. Ōhōri Yasumochi, the priest, had two other brothers: Tsuruhime claimed she had received divine inspiration, but she was living in a temple dedicated to the older brother of the Japanese sun goddess Amaterasu, god of war, and it was a place of pilgrimage for samurai who often visited and left their weaponry there. It’s easy to see where the inspiration might have come from.

She participated in many battles, but the inciting incident to her career is probably the threat that Ōuchi Yoshitaka constituted for her home island. A war eventually broke out between his clan and the Kōno clan who controlled the island of Ōmishima at the time. Tsuruhime was fifteen at the time and she wasn’t the rebel daughter who wanted to fight: her father had died a year before, and she had been given the position of chief priest. Her stance against the Ōuchi clan was an official one, with her two elder brothers already killed in battle: she proclaimed herself the avatar of a kami, organized the resistance when the Ōuchi samurais raided her island and eventually led an army which drove them back into the sea.

The sea is the main character of the part Benjamin Lacombe decides to illustrate, a story set four months later when the invaders return.

Tsuruhime resumes her role as leader of the resistance once again and throws herself into the cold sea, in an impulsive plan to reach the main ship of the invaders before they can reach the island and raid it again. The water is cold, she’s without her armor, but the sea creatures embrace her and give her strength.

On a side note, I love how the illustration above reverses popular tropes spawning from illustrations such as

The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife

that Lacombe must know very well. If there’s any eroticism in the picture, Tsuruhime has a definitely active role.

On a side note, I love how the illustration above reverses popular tropes spawning from illustrations such as

The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife

that Lacombe must know very well. If there’s any eroticism in the picture, Tsuruhime has a definitely active role.She eventually reaches the ship, where an Ōuchi general, Ohara Takakoto, is drinking with his men. The maiden challenges him in a duel and eventually beheads him. Lacombe decides to illustrate the metaphorical general as an actual one.

After this victory, Tsuruhime goes back to her island and reunites with her army.

After the duel, it’s said the young warrior goes to rest and has a dream: she dreams of peace, at last, but a peace she can only reach by walking into the ocean, drowning herself and communing perpetually with the sea creatures who dwell in there. Some narrators justify her suicide with grief for the death of her betrothed Yasunari Ochi, but I prefer this version better.

Tomoe Gozen (late XII Century)The first proper room is dedicated to Tomoe Gozen, however, who has also a panel with illustrations by the end of the itinerary. I talked about her a while ago in the second of my three pieces on the Heike Monogatari, where she features as one of the most prominent characters.

Her room revolves around a part of her story as told in Chapter 9 of the traditional ensemble for the Heike Monogatari: her lord is trying to flee from a lost battle, alongside her and his foster brother, but his horse gets stuck in the mud of a paddy field, the enemy’s archers catch up with them and the lord is struck to death.

“Quickly now,” Lord Kiso said to Tomoe. “You are a woman, so be off with you; go wherever you please. I intend to die in battle, or kill myself if I am wounded. It would be unseemly to let people say, ‘Lord Kiso kept a woman with him during his last battle.’

Needless to say, she doesn’t take it well.

She initiates a flight, surrounded by the hissing of arrows, but ultimately can’t stand leaving her lord. She turns around and reaches him, in time to see enemies beheading him and celebrate with his head on a pike. She disembowels one enemy and rips the head off another, recomposes the body and disappears.