Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 51

August 11, 2023

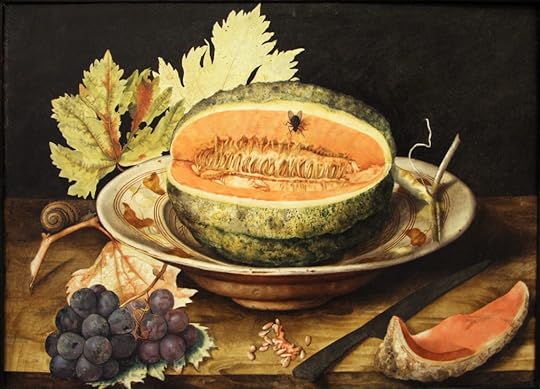

Giovanna Garzoni: painter and natural scientist

Considered the most prominent miniaturist of the Baroque Era, Giovanna Garzoni distinguishes herself for the production of still lives, parchments painted in a particular style called “a guazzo” and swift impressions in guache that almost seem to come out of another era. Her style alone would make her interesting material for my WIP novel.

Giovanna Garzoni, “Tray with Cherries and a Carpenter Bee” (1642-51)

Giovanna Garzoni, “Tray with Cherries and a Carpenter Bee” (1642-51)She was born from a family of Venetian crafters, and studied in Venice: she attended a school of calligraphy founded by Giacomo Rogni and the workshop of painters such as Jacopo Palma the Younger, impressing both with her fresh talent. She quickly broke away from traditional painting, pursuing less traditional forms of art and “minor” disciplines such as miniatures.

Between 1618 and 1621 she moved to Florence, where she tried to find a place at court with Maria Maddalena d’Austra, Grand Duchess of Tuscany, and met with the greatest painter of this time: Artemisia Gentileschi. She would move to Naples with Artemisia herself, where they both will work for Viceroy Fernando Alfan de Ribera, Duke of Alcalà.

When the Duke was recalled to Spain, Giovanna turned to an acquaintance she had met during their travels with Artemisia: Cassiano Dal Pozzo. Cassiano was a collector and mecenate, and had introduced her to the naturalistic studies of the recently funded Accademia dei Lincei: he introduced her to several patrons and Giovanna turned to portraits, a subject that was likely to pay your bills. She produced several of them during her stay in Rome, and this work earned her enough fame to be called at the court of Cristina di Francia, Duchess of Savoy, in Turin. She painted several portraits, there, but also indulged in the production of mythological subjects and, of course, her beloved miniatures.

Giovanna Garzoni, “Still life with popone, grapes, a fly and a snail” (1642-51)

Giovanna Garzoni, “Still life with popone, grapes, a fly and a snail” (1642-51)In Turin, however, she discovered what was going to be her favourite subject: naturalistic still lives. She met with artists such as Fede Galizia, Panfilo Nuvolone, Lodewijck Susi, Isaak Soreau and Peter Benoit.

When Vittorio Amedeo di Savoia died in 1637, she briefly visited England where her friend Artemisia was working, and eventually moved to Paris, where she counted as her patrons prominent figures such as Cardinal de Richelieu and King Louis XIII himself. Her fame brought her back to Rome and Florence, where she studied natural sciences through the drawings of Jacopo Ligozzi and could consult the Medici collection of natural wonders. Grand Duke Ferdinando II commissioned her several paintings, and she became close friends with his wife Vittoria della Rovere.

Giovanna Garzoni, “Chinese Vase with Flowers, a Fig and a Bean”

Giovanna Garzoni, “Chinese Vase with Flowers, a Fig and a Bean”She moved to Rome in 1651 and never moved again. She would paint miniatures and still lives, execute commissioned portraits and pursue natural studies, regularly giving parts of her work to the local Accademia di San Luca, but she would never be admitted to the scientific lectures. Three hundred years later, Beatrix Potter would share the same fate.

She died in 1670 and left everything to the Academy, which would build her a monument in the Church of Saint Luca and Martina.

July 28, 2023

Marietta Robusti

Marietta Robusti had one problem in life: being born to a famous father. In an age where emerging as a female artist was almost as difficult as today, she would live her life under his shadow and eventually became known as “the Tintoretta”.

Marietta was born outside and prior to the painter’s marriage, allegedly from a liaison with a German woman he was very much in love with. We know very little of her mother, of her childhood and we even ignore her exact date of birth: all we know is that she and her brother Domenico were working in their father’s atelier and assisting him with the many commissioned portraits. They were so efficient that, according to a family friend, they were able to finish a portrait of Doge Girolamo Priuli in around half a hour (they had already prepared lots of the work, foreseeing the arrival of this commission).

News of Marietta come primarily from two sources: a 1584 treaty by Raffaello Borghini titled Il riposo (The Rest), and the biography of her father penned by Carlo Ridolfi in 1642. According to the latter, Marietta was fair and gracious, could play the lute exceedingly well and was a highly accomplished painter.

We have no way of knowing the extent of her contribution to her father’s works, but we know at least of two works she finished alone: the portrait of Ottavio Strada, an antiquarian at the court of Emperor Maximilian II, and a self-portrait the Emperor himself was very fond of. Another audacious self-portrait in the Venetian style is currently preserved at the Prado Museum.

Marietta Robusti, Portrait of Ottavio Prada. The antiquarian is receiving stuff straight from Heaven.

Marietta Robusti, Portrait of Ottavio Prada. The antiquarian is receiving stuff straight from Heaven.

Marietta Robusti, Self Portrait.

Marietta Robusti, Self Portrait.Her specific presence was requested at court by both Philiph of Spain and Archduke Ferdinand, but he refused and married her off to some guy, so that she wouldn’t leave his side. In writing Tintoretto’s biography, Ridolfi paints this decision as that of a loving father, and not the one of a possessive asshole who didn’t want his thunder being stolen by his talented daughter. Thanks to his decision, we don’t have any certainty as to which paintings the authored. She lived the rest of her days in her father’s shadow.

She died four years before him, and one of her most famous depictions is by Romantic painters such as Guglielmo De Martino or Léon Cogniet, who imagines Tintoretto painting his daughter on her deathbed. Such a painting does not exist.

July 21, 2023

Ginevra Cantofoli

Ginevra died in 1672 aged 54 years, and that’s the only way we know she was born in 1618. News of her life are scarce, but she entered the orbit of the more famous paintress Elisabetta Sirani and from her diary we know Ginevra Cantofoli was a lady and a paintress in her own right. Elisabetta’s portrait is sadly lost, but it was one of the first works she did in her early career: it’s delightful to imagine an accomplished Ginevra offering patronage and work to a younger, talented Elisabetta, and it’s also very sad to see how short-lived was Ginevra’s fame. At this time, Ginevra was accustomed to working on small portraits, often on glass, and her friend of twenty years younger prompted her to challenge the public with larger pieces. Biographers get it the other way around, with Ginevra often considered a “disciple” of Elisabetta because I guess what Elisabetta herself writes is of little interest to them.

Amongst the first important works Ginevra was commissioned, already married and mother of a girl, we have news of an altarpiece in 1658 in the very centre of Bologna, where the artistic competition had to be extreme. The church was San Giacomo Maggiore, where she will be buried, and it’s an absolutely stunning place.

The Bentivoglio Chapel in San Giacomo Maggiore (Bologna)

The Bentivoglio Chapel in San Giacomo Maggiore (Bologna)Throughout her career, Ginevra will produce six altarpieces in Bologna alone, a remarkable number for the time and place: five of them are lost, but one was reproduced and we know how it might have looked from several contemporary drawings.

After the death of her husband in 1668, she drafted an inventory of her own works to safeguard their daughter Orsola, and this is the most comprehensive catalogue we have of her paintings. Alongside the small works she painted on glass during her early career, the catalogue includes 51 paintings of larger dimensions and reproductions of her own works. Some sadly lost pictures include non-religious subjects such as a tale on Calypso. Some of her scenes are so unusual that historians have no other way to describe them as an “unknown allegory”: the most famous example is this scene of two women with a snake.

She painted some Sibyls and several allegories of painting, including a favourite challenge of artists throughout all times: the mirror. Particularly beautiful to me is a Cleopatra dropping a pearl into a cup.

Ginevra Cantofoli, Allegory of… something

Ginevra Cantofoli, Allegory of… something

Ginevra Cantofoli, Allegory of Painting

Ginevra Cantofoli, Allegory of Painting

Ginevra Cantofoli, Sibyl

Ginevra Cantofoli, Sibyl

Ginevra Cantofoli, Cleopatra

Ginevra Cantofoli, CleopatraWhen she died in 1672, she was a wealthy and accomplished professional, with several properties in both land and buildings. Her work has often been attributed to her (male) cotemporaries, such as this beautiful painting of a lady in a turban, longly attributed to Guido Reni.

Ginevra Cantofoli, Woman with a turban (attributed to Guido Reni)

Ginevra Cantofoli, Woman with a turban (attributed to Guido Reni)

July 14, 2023

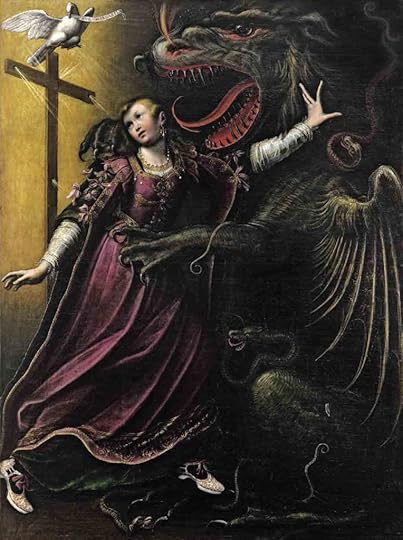

Orsola Maddalena Caccia

What can you do when all you want to do is paint and you have the full support of your family but society would never accept it? The Caccia family knew the answer: you take the vows and found your own artistic school, disguising it as a monastery. Let’s take a dive into XV Century art history and explore the life and works of Orsola Maddalena, born Theodora Caccia, one of the most prolific painters of her time.

The post came out yesterday in early access on my Patreon.

Orsola Maddalena CacciaMoncalvo (Asti), 1596 – Moncalvo (Asti), 1676Theodora came from a family of artists: her father was possibly the most famous painter, Moncalvo was a duchy under Mantua and it was ruled by Vincenzo I Gonzaga and Eleonora de’ Medici. Her father worked with Federico Zuccari at the Carlo Emanuele I Gallery in Turin, and in Milan with artists in the retinue of Federico Borromeo, and Orsola’s mother also came from a family of artists, so it’s safe to assume she supported her daughters Orsola and Francesca in their pursuit of an artistic career. During their lifetime, the two sisters were called “the Fontanas of Monferrato“, with reference to Lavinia and Artemisia Fontana.

Theodora started studying at home, and a composition painted in her youth is a testimony to her fondness for Raphael.

Raffaello, Madonna del Divino Amore (1516)

Raffaello, Madonna del Divino Amore (1516)

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Sacra Famiglia

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Sacra FamigliaShe soon started working with her father, replacing him on several commissions, but the spectre of marriage eventually started looming on her life and her sisters, and they all choose the monastery: in 1620 Theodora took vows with the Ursuline sisters in Bianzé, she choose the name Orsola Maddalena and kept painting, alongside producing incredible illuminated initials. Her two sisters followed though we don’t know whether they worked together.

Five years later, their wealthy father pulled off a bold move: he financed the founding of a new monastery within his own residence, a place more akin to a painting atelier, where his daughters could keep painting and be safe. Orsola was nominated abbess of this unusual retirement place, and the sisters could inherit all of their father’s wealth when he died later the same year. She will remain in this position till 1652 and gave us several maternal scenes with the Virgin and Sant’Anna.

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Vergine con Bambino e Sant’Anna (1630)

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Vergine con Bambino e Sant’Anna (1630)With her altarpieces, she’s one of the most prolific artists of the modern age, but she also painted lots of works destined for private places and a delicate selection of still-lifes.

Amongst her favourite subjects, the depiction of the contemporary mystic Osanna Andreasi from Mantua, who followed in the footsteps of Catherine from Siena and took her vows to flee an arranged marriage. Orsola dedicated her a vibrant painting in 1648, titled The Mystic Marriage of Osanna Andreasi and currently preserved in Mantua.

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Matrimonio Mistico di Osanna Andreasi (1648)

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Matrimonio Mistico di Osanna Andreasi (1648)There’s a subtle element of resistance in the choice of this topic, and the same delicate expression of self can be seen in other portraits of contemporary female saints. My favourite painting of hers of course has to be a more visionary one: an extraordinary Saint Marguerite of Antiochia with the dragon that often gets overlooked in favour of more traditional subjects and compositions.

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Santa Margherita di Antiochia con il Drago

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Santa Margherita di Antiochia con il DragoThe same subject is also present in another less violent painting, in which the Saint is simply shunning the dragon’s temptation and prefers to look at the Cross.

Regardless of the ascetic subjects and her monastic condition, we mustn’t think of Orsola as a shy painter recusing the temptations of mundane life: she sought affirmation as an artist in the European courts and established rich relationships with both the Gonzagas, particularly Bishop Scipione Agnelli, and with the Savoias. Her letters to Christine of France, born Princess and longly regent of the Savoia duchy, are a testament to her cleverness and ambition.

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Margherita di Antiochia e il Drago

Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Margherita di Antiochia e il DragoWithin her own monastery, other women sought shelter in other to pursue the artistic career, most notably Angiola Maria and Laura Bottero who took their vows and were named Angelica and Candida Virginia.

Orsola’s sister Francesca died in 1628 when she was in her 20s, and she could be a good choice when writing about characters who fell through the cracks of history.

June 19, 2023

Covid, Rats and Blues: an update

For those of you who don’t follow me on Twitter, here’s a small update on the status of my novel and its author.

First of all, the English draft of the novel is finished and I have an idea for a title. The working title of the series was The Marvellous Voyages of the Queen Anne, and I always knew it was never going to be the final title, but I teased my beta-readers with an acronym. Well, now they know what it stood for.

The next steps are:

1. querying for sensitivity readers (I have a good option in mind, but she’s fairly expensive for the current status of my pockets… more on that later);

2. querying for an agent to represent me.

This week I wanted to start looking into both: there’s material to be produced, and material I massively suck at, such as outlines and a synopsis. That’s when it happened.

I live at the ground floor of a fairly old building (think XIX century). It’s vernacular architecture, nothing fancy, but we have a wooden ceiling and very thick walls, with a massive industrial-style entrance door in glass and iron.

The building is in the canal district, a very popular place for people who want to party and, as you might imagine, for the Norwegian Rat.

If you’re thinking “I know where this is going”, you’re probably right.

Rats have always been a problem. My upstairs neighbour, one of my least favourite people in the world right now, has been neglecting a rat infestation in her floor for almost a decade because it doesn’t affect her much and she could afford to live somewhere else.

The problem got worst and worst.

It meant we sometimes had to sleep with all the lights on, waking up to scratching noises in the middle of the night and rushing to spray natural repellents or bang stuff against the ceiling (a historical wooden ceiling with massive supporting beams and planks thrown across them). There’s only so much you can do while you live inside the house.

The fear has always been they would find a way to munch through the wood and break havoc or dig a hole in the wall and break in.

They never succeeded.

Before this month.

On Thursday I was determined to find the source of a very unpleasant odour and… well, I discovered I had a rat nest right behind my favourite spot for working, writing and dining. I thought it was my corner. It turns out I was sharing it with neighbours.

The bad smell was one of such neighbours, who had decided to crawl inside a container and die.

I still fancy him more than the upstairs neighbour.

Now we’re carefully inspecting everything we have and packing it as fast as we can since there’s no guarantee there isn’t more of them roaming around at night. It will take months.

But that’s not all, folks!

This morning I woke up coming down with a cold and, of course, I took covid test. Guess what? I won’t be packing any boxes of books any time soon: I’ll be at my current shelter, unpacking DVDs to recycle the boxes and pondering around the meaning of life.

Meanwhile, I left my novel with my trusted beta readers and my heart still hopes I’ll be able to assemble some material for a couple of sensitivity editors. Am I dreaming? Send good vibes.

May 20, 2023

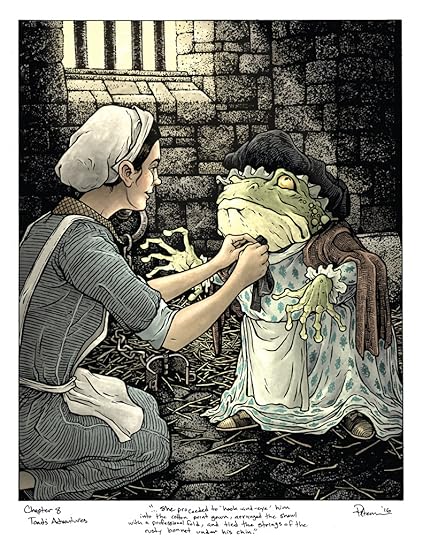

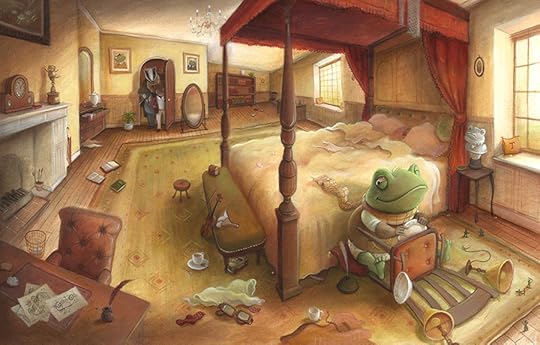

Washerwomen and Cross-Dressing Heroes: Toad’s Great Escape

Well, we’ve reached Chapter 8 in the re-reading of The Wind in the Willows (I already mentioned it here and here), and Chapter 8 is where we see Toad’s misadventures reaching a peak of misery: the rascal has been put in prison where he laments his bad fate, he gets into the good graces of the gaoler’s daughter, cross-dresses as a washerwoman and daringly escapes on board of a train. There you have it.

Now, as you know I’m not particularly fond of Toad, but there are a couple of interesting features in this chapter and I’d like to address them in comparison with other tales I’m very fond of. So stick with me if you’re fond of washerwomen and cross-dressing heroes.

1. Mrs Tiggy-Winkle, laundresses in the night and other working-class ladiesWasherwomen are a recurring element in Breton’s folklore, particularly as the so-called lavandières de la nuit, laundresses of the night: they’re ghostly women cursed to do their laundry for eternity, who go around scaring the shit out of people in the middle of the night, and variants of these include the Washer at the Ford trope, the Gaelic bean-nighe, ghostly women in Ireland who wash the bloodied skirt of people about to die, oracle figures in Scotland and wish-granters in Wales (if they don’t rip your arms out like a Wookie, that is).

Jean-Édouard “Yan” Dargent painted them in his 1861 work, and I think you get the idea.

Yan’ Dargent, Lavandières de la nuit (1861)

Yan’ Dargent, Lavandières de la nuit (1861)Illustrations on the same subject were drawn by a plethora of local artists such as Victor Lemonnier (see here) and Emile Souvestre (see here). There’s a beautiful blog post about them, telling one of the scariest legends, at this address.

When Grahame started writing his story, however, society had already declassified laundry as a job fit for lower-class women. The infamous Magdalene asylums picked this specific job as suitable for their “fallen women”, and not by chance. The way Charles Dickens shows us a washerwoman, in his Christmas Carol, is a good indication of the place they had in society: such a woman steals the blankets and curtains from the mysterious man who died unloved during the vision with the spirit of Christmas Yet To Come.

“His blankets? Why, Mrs Dilber, they’re still warm.”

“His blankets? Why, Mrs Dilber, they’re still warm.”The most famous washerwoman in children’s literature, however, is quite possibly Beatrix Potter‘s Mrs Tiggy-Winkle in the homonymous tale. Published in October 1905, the story took inspiration from an old Scottish countrywoman Beatrix had met during her childhood, Kitty MacDonald, when the Potters were spending their holidays at Dalguise, Perthshire. Their relationship was close enough for Beatrix to visit her again when she moved back to Scotland, this time in Birnam, aged 27. The woman was 83, at this time, but Beatrix described her as…

…old Katie MacDonald, the Highland washerwoman. She was a tiny body, brown as a berry, beady black eyes and much wrinkled, against an incongruously white frilled mutch. She wore a small plaid crossed over shawl pinned with a silver brooch, a bed jacket, and a full kilted petticoat. She dropped bob curtsies, but she was outspoken and very independent, proud and proper.

If you want to read more about their relationship, I suggest you take a look here. A mutch, as defined by the Scots Language Centre, is a headdress of white linen or muslin, quite similar to a cowl.

The name Mrs Tiggy-winkle, on the other hand, comes from Potter’s pet hedgehog.

Two studies of a hedgehog by Beatrix Potter, preserved at the Victoria & Albert museum.

Two studies of a hedgehog by Beatrix Potter, preserved at the Victoria & Albert museum.The main character of the tale is Lucie Carr, modelled after a real-life Lucy, and it’s one of the few stories by Potter in which a child is invited to partake in the animal kingdom and its day-to-day functioning.

As she’s roaming the Little-Town farm in search of three pocket handkerchiefs and a pinafore she lost (again, the pinafore is some sort of apron), little Lucie follows a trail of clothes up a grassy hill, finds a small wooden door and hears someone singing.

Lily-white and clean, oh!

With little frills between, oh!

Smooth and hot – red rusty spot

Never here be seen, oh!

That’s how she learns of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle who lives inside the house, and whom she finds doing the laundry, ironing and, of course, singing.

She found Lucie’s lost clothes, washed them and ironed them. Picking up a big basket of laundry, the two set off to return all the rest of the clothing to animals and birds in the neighbourhood: there’s a pair of yellow socks for Sally Henny-penny, the spotted hen who has been running barefoot since the beginning of the story, there’s a red handkerchief belonging to old Mrs Rabbit which smelled rather nastily of onions, there’s a pair of mittens for Tabby Kitten, dicky shirt-fronts for Tom Titmouse and woolly coats belonging to the little lambs at Skelghyl. It is as if Potter revisited all her previous stories and concocted a character who’s tidying up the animal’s apparel behind the scenes.

Lucie and Mrs Tiggy-Winkle have tea together, and then they set off to return the laundry to each one of these animals. Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny even make guest appearances.

When the two are done, however, a magical thing happens, which is also quite unlike in Potter’s stories.

Lucie scrambled up the stile with the bundle in her hand; and then she turned to say “Good-night,” and to thank the washer-woman.—But what a very odd thing! Mrs. Tiggy-winkle had not waited either for thanks or for the washing bill!

She was running, running, running up the hill—and where was her white frilled cap? and her shawl? and her gown—and her petticoat?

And how small she had grown—and how brown—and covered with prickles!

Why! Mrs. Tiggy-winkle was nothing but a Hedgehog!

(Now some people say that little Lucie had been asleep upon the stile—but then how could she have found three clean pocket-handkins and a pinny, pinned with a silver safety-pin?

And besides—I have seen that door into the back of the hill called Cat Bells—and besides I am very well acquainted with dear Mrs. Tiggy-winkle!)

Her vanishing is by far less scary than any story you might read on the washerwomen in the night, but not less supernatural. There seems to be something otherworldly about doing the laundry, especially when it’s bourgeoise authors who write about it.

Sir Frederick Ashton performed in the role of Mrs Tiddy-Winkle during the 1971 Tales of Beatrix Potter with the Royal Ballet, a show that returned around 10 years ago. He was also the choreographer, so he really can’t blame anybody but himself.

Now, Grahame is not as accurate as Potter in his description of the clothes the laundress sells Toad as a device for his escape. They’re a cotton print gown, an apron, a shawl, and a rusty black bonnet with strings that are tied under Toad’s chin. Many illustrators have tried their hand at depicting the scene. David Peterson, who worked on his illustrations for a book published by IDW around 2016, gives us a detailed account of his process in this marvellous blog post.

illustration by David Peterson

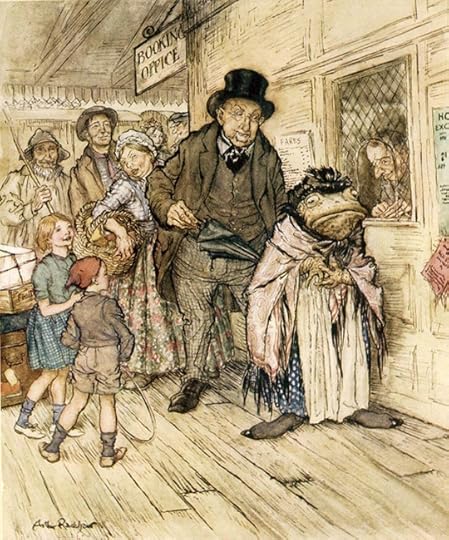

illustration by David PetersonThe most refined depiction of Toad’s disguise is however, in my humble opinion, depicted by Arthur Rackham. The cap, the shawl, the detail of the skirt and even the idea of the sloppy socks used to conceal Toad’s feet are an absolute delight.

Illustration by Arthur Rackham2. Cross-dressing heroes

Illustration by Arthur Rackham2. Cross-dressing heroesIn his book Children’s Literature, Seth Lerer dedicates a whole chapter to Edwardian literature and, by calling it “Pan in the Garden”, a great part of it is dedicated to our Kenneth Grahame. He has something particularly interesting to say about Toad’s disguise, comparing it with contemporary adventure stories like Anthony Hope’s tremendously influential Prisoner of Zenda (1894), Robert L. Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde which is all about changing appearances (1886) and Sir Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories.

What readers… found so enduring in these works was their concern with costume and impersonation. They make adventure inseparable from dress-up, and Toad’s tale chimes with their details.

Illustration by Chris Dunn. The illustrator decides on an accurate Victorian cap.

Illustration by Chris Dunn. The illustrator decides on an accurate Victorian cap.And he continues (spoiler alert from the following chapters):

When he comes home from his exploits, he finds Rat and recognizes that “he could lay aside a disguise that was unworthy of his position”. Such a decision llies at the heart of these late Victorian and Edwardian works, for it asks the questions central to the age: What is the nature of the self? How do we dress to reveal, or conceal, our inner being? Will the dark inside come out, regardless of our costume? …Toad’s escapades had been ones of “escapes”, “disguises,” and “subterfuges.” And when Rat finally gets Toad to calm down, he implores him to “go off upstairs at once, and take off that old cotton rag that looks as if it might formerly have belonged to some washerwoman, and clean yourself thoroughly, and put on ome of my clothes, and try and come down looking like a gentleman, if you can.” For Rat, impersonation is a vice. The true gentleman is not a creature of the theatre, but a man of the house.

Now, this angle is tremendously interesting, in my opinion, for we aren’t sure at all Grahame entirely agreed with Rat’s firm position and, if we are, his remark is more classist than specifically referred to the cross-dressing aspect of the whole situation.

As pointed out by Annie Gauger in her paramount Annotated version of the book, Toad’s dress-up has noble roots in literature and bears a strong echo of Falstaff’s misadventures in Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor, in which the hero is aided by Mistress Page and disguised as her aunt, a woman known as “the fat woman of Brentford”. To disguise the knight, they fetch a gown, a hat or some linen for his head, a muffler, and a handkerchief. Things develop in a way so unheroic that Toad’s escape seems like a chivalrous runaway: even posing as the fat lady, Falstaff is beaten black and blue or, as he put it, in all the colours of the rainbow.

In an early version of the tale, Toad got beaten by one of the guards in a similar fashion, as he bore resentment because the actual washerwoman had mismanaged his laundry. The beating was erased in the final version but oddly replaced with sexual tension where Toad has to undergo all the usual humiliations and catcalls from the guards in order to escape. A weird thing to put in a book for children, I know.

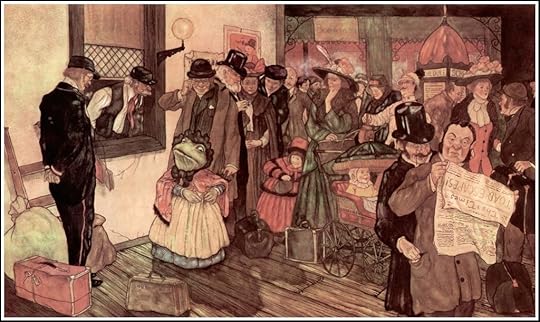

Toad trying to buy a train ticket by Michael Hague

Toad trying to buy a train ticket by Michael HagueA much nobler predecessor is to be found in Greek epics, and there’s no doubt of an explicit connection between The Wind in the Willows and Homer (as we’ll see in the title of the very last chapter). Geraldine Poss in her “An Epic in Arcadia”, quoted by Gauger, draws an early parallel between Toad and Ulysses, as they both escape with the aid of a woman, but I think the parallel is much more accurate when made between Toad’s unbecoming disguise and what Achilles tries to pull off while trying to avoid leaving for war. Though absent in the canonical Ilyad, the story sees the hero disguising himself as a girl at the court of the king of Skyros, falling in love with one princess Deidamia, and marrying her. Sometimes, she even cross-dresses in return and follows him to war posing as a man. It’s traditionally Odysseus who reveals the trick with his proverbial cunning, hence a bit of bad blood between the two.

Gerard de Lairesse paints Achilles disguised as a woman and… can you spot him? Because I can’t.

Gerard de Lairesse paints Achilles disguised as a woman and… can you spot him? Because I can’t.Ludovico Ariosto doesn’t fail to pick up gender swapping as a central theme in his Orlando Furioso: when Fiordespina falls in love with Bradamante after seeing her in full armour, a tale left incomplete by Boiardo in his Orlando Innamorato, it is her brother who disguises himself as a woman and snatches the fruit of this passion.

If you think you can dismiss the notion of a cross-dressing hero just because it’s just Greeks being Greeks and Italians being Italians, I’ve got bad news for you: Norse mythology is literally riddled with heroes who dress as women through tribulation or as some part of a trick. Most famously, Thor dresses as a woman in the Þrymskviða poem of the Poetic Edda, posing as no other than Freyja dressed up as a bride. If you’re wondering, it’s of course Loki who convinces him, and dresses up as his bridesmaid. Now tell me it’s a thing you don’t wish to see in the Marvel version.

[image error] Carl Larsson gives us a beautiful illustration of the sceneThe notion of men dressing up as women to aid an escape is also a common trope in English ballads: Robin Hood and the Bishop, collected by Francis James Child, sees the titular hero trading clothes and accessories with an old spinner woman; the Duke of Athole is aided by an innkeeper’s daughter and disguised as a baker to save him from women who came for him instead of his love; Robin Brown uses a similar trick to hook up with the king’s daughter, though depending on the version he’s not always lucky.

Being a trickster, Disney’s Robin Hood isn’t a stranger to cross-dressing either. The idea of using a gipsy fortune-teller echoes Jane Eyre (1847), in which Mr Rochester employs that trick to try and extort a love confession from the main character.

Being a trickster, Disney’s Robin Hood isn’t a stranger to cross-dressing either. The idea of using a gipsy fortune-teller echoes Jane Eyre (1847), in which Mr Rochester employs that trick to try and extort a love confession from the main character.

May 16, 2023

#OTD in Stoker’s Dracula

—God preserve my sanity, for to this I am reduced. Safety and the assurance of safety are things of the past. Whilst I live on here there is but one thing to hope for, that I may not go mad, if, indeed, I be not mad already. If I be sane, then surely it is maddening to think that of all the foul things that lurk in this hateful place the Count is the least dreadful to me; that to him alone I can look for safety, even though this be only whilst I can serve his purpose. Great God! merciful God! Let me be calm, for out of that way lies madness indeed. I begin to get new lights on certain things which have puzzled me. Up to now I never quite knew what Shakespeare meant when he made Hamlet say:—

“My tablets! quick, my tablets!

‘Tis meet that I put it down,” etc.,

for now, feeling as though my own brain were unhinged or as if the shock had come which must end in its undoing, I turn to my diary for repose. The habit of entering accurately must help to soothe me.If you want to read something nice about the usage of Shapeskeare in Dracula, I suggest you take a look here.My favourite take on the subject, however, has to be Christy Desmet’s essay “Remembering Ophelia: Ellen Terry and the Shakespearizing of Dracula” in the excellent Shakespearean Gothic published by the Wales University Press.

May 15, 2023

#OTD in Stoker’s Dracula

My main character is waiting for an answer over a message they sent, and stressing about it, and everyone else is carrying on with their own business.Still, the day features in Stoker’s Dracula, and I thought it unkind not to have a post about it. Jonathan Harker has accepted he is either loosing his marbles or witnessing something terrible, at this point in his diary.—Once more have I seen the Count go out in his lizard fashion.

He moved downwards in a sidelong way, some hundred feet down, and a good deal to the left. He vanished into some hole or window.

When his head had disappeared, I leaned out to try and see more, but without avail—the distance was too great to allow a proper angle of sight. I knew he had left the castle now, and thought to use the opportunity to explore more than I had dared to do as yet.

I went back to the room, and taking a lamp, tried all the doors. They were all locked, as I had expected, and the locks were comparatively new; but I went down the stone stairs to the hall where I had entered originally. I found I could pull back the bolts easily enough and unhook the great chains; but the door was locked, and the key was gone! That key must be in the Count’s room; I must watch should his door be unlocked, so that I may get it and escape.

I went on to make a thorough examination of the various stairs and passages, and to try the doors that opened from them. One or two small rooms near the hall were open, but there was nothing to see in them except old furniture, dusty with age and moth-eaten.

At last, however, I found one door at the top of the stairway which, though it seemed to be locked, gave a little under pressure. I tried it harder, and found that it was not really locked, but that the resistance came from the fact that the hinges had fallen somewhat, and the heavy door rested on the floor. Here was an opportunity which I might not have again, so I exerted myself, and with many efforts forced it back so that I could enter.

I was now in a wing of the castle further to the right than the rooms I knew and a storey lower down. From the windows I could see that the suite of rooms lay along to the south of the castle, the windows of the end room looking out both west and south. On the latter side, as well as to the former, there was a great precipice. The castle was built on the corner of a great rock, so that on three sides it was quite impregnable, and great windows were placed here where sling, or bow, or culverin could not reach, and consequently light and comfort, impossible to a position which had to be guarded, were secured. To the west was a great valley, and then, rising far away, great jagged mountain fastnesses, rising peak on peak, the sheer rock studded with mountain ash and thorn, whose roots clung in cracks and crevices and crannies of the stone.

This was evidently the portion of the castle occupied by the ladies in bygone days, for the furniture had more air of comfort than any I had seen. The windows were curtainless, and the yellow moonlight, flooding in through the diamond panes, enabled one to see even colours, whilst it softened the wealth of dust which lay over all and disguised in some measure the ravages of time and the moth.

My lamp seemed to be of little effect in the brilliant moonlight, but I was glad to have it with me, for there was a dread loneliness in the place which chilled my heart and made my nerves tremble. Still, it was better than living alone in the rooms which I had come to hate from the presence of the Count, and after trying a little to school my nerves, I found a soft quietude come over me.

Here I am, sitting at a little cake table where in old times possibly some fair lady sat to pen, with much thought and many blushes, her ill-spelt love-letter, and writing in my diary in short hand all that has happened since I closed it last.

It is nineteenth century up-to-date with a vengeance.

And yet, unless my senses deceive me, the old centuries had, and have, powers of their own which mere “modernity” cannot kill.

May 12, 2023

Who’s afraid of the Great God Pan?

I’ve been reading a splendid and passionate book on the God Pan by Paul Robichaud, and it seems to be perfectly on point with the collective re-reading of The Wind in the Willows we’re doing on Twitter with a group of people. As you might remember, there’s one particular chapter I’m particularly fond of – Chapter 7 – in which our heroes the Mole and the Rat go out at night looking for a lost baby otter. If you haven’t, I suggest you take a look at this old article I wrote before you proceed.

According to Tolkien, the appearance of the Great God Pan in this story is an overdoing on behalf of Kenneth Grahame, «that addition of an extra colour that spoils the palate». But of course, I don’t agree with him in this instance, though I understand the purity he expects from stories.

Now, there’s one particular passage in the chapter, where the Rat and the Mole come face to face with the divine apparition, and Grahame knows better than to pick words lightly when it comes to Pan.

“Afraid! Of Him? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!”

The connection between Pan and terror is an ancient one, and it had fleeting fortune throughout the centuries.

Among the many epithets for the god, we find Phorbas, “the terrifying one”. According to some sources, it was one of the primary aspects of the god, equally important to Agreus, “the hunter”, and the pastoral Nomios.

The name of Mr Agreus in the tv show Carnival Row alludes to Pan.

The name of Mr Agreus in the tv show Carnival Row alludes to Pan.I’m sure you’re all familiar with Algernon Blackwood‘s powerful usage of mythical creatures as a source of horror, as it happens in The Centaur (1911), and the most famous usage of Pan in this way is probably made by his contemporary Arthur Machen in his novella The Great God Pan (1890). Tiptoeing the fine lines between Gothic, fantasy and science fiction, Machen’s novel tells the story of a disturbing woman who’s the source of death and horror to the people around her, and who’s later revealed to be the offspring of the forced encounter between a woman and the god Pan during an occult experiment.

Take Pan, replace it with an extraterrestrial entity, and you have a story by H.P. Lovecraft.

Illustration by Aubrey Beardsley

Illustration by Aubrey BeardsleyPan here is given a dark twist, with him representing “intelligence blended with a darker power, deeper, mightier, and more universal than the conscious intellected man”, as S.T. Coleridge put it more than a century before Machen while looking at a strangely horned statue of Moses by Michelangelo.

The same idea will be picked up by John Keats in the Hymp to Pan featured in his Endymion (1818):

O hearkenee to the loud-clapping shears,

While ever and anon to his shorn peers

A ram goes bleating: Winder of the horn,

When snouted wild-boars routing tender corn

Anger our huntsman: Breather round our farms,

To keep off mildews, and all weather harms:

Strange ministrant of undescribed sounds,

That come a-swooning over hollow grounds,

And wither drearily on barren moors:

Dread opener of the mysterious doors

Leading to universal knowledge—see,

Great son of Dryope,

The many that are come to pay their vows

With leaves about their brows!

The German scholar and philologist Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher will be paramount in the definition of this concept and linked Pan to the experience of the nightmare in his Ephialtes: A pathological-mythological treatise on nightmares and the half-demons of classical antiquity (1900 sharp).

But are these phantasies grounded in the original sources? Let’s find out.

Panic in appearance: half-man, half-animal

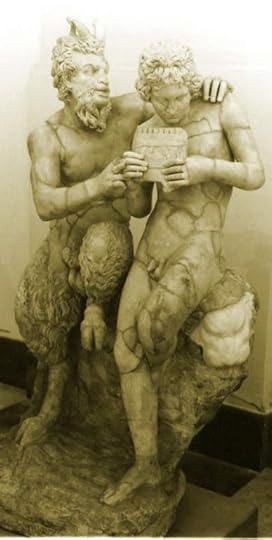

According to Paul Robichaud in the book I mentioned above, a first reason for terror in confronting the god Pan comes from his hybrid physical features and indeed the first result of the god’s birth was freaking people out.

Though sources give conflicting accounts of his father and all these stories are likely to originate when the Peloponnesian Greeks tried to absorb into their pantheon a pastoral deity born in the Arcadian region, Pindar and the so-called Homeric hymn all agree on one account: when the infant god was born, the first one to see him fled in terror. In the Homeric hymn, the one to flee is his nurse, while his father Hermes laughs at the son’s difformities and takes them as a sign of mischief. He brings the child to Olympus and the gods are equally delighted at his sight, particularly Dyonisus who probably is starting to see some resemblances between him and the goat-footed creature. Both gods in fact are associated with an altered state of mind, have strong connections with feral animals such as the lynx and go around with a retinue of merry women you shouldn’t mess with (nymphs for Pan, and maenads for Dyonisus).

In this sense, it’s interesting how Reinassance and Baroque pick up on Pan’s lively attitude and connect him with another hybrid, half-man, half-bird this time: winged Cupid.

Painting by Giovanni Bilivert

Painting by Giovanni BilivertFrom the Homeric hymn comes the very old but erroneous idea that the name “Pan” is connected to the Greek word “all”. The origin most likely lies in the word “paean”, to pasture, with a play on words with the similar term “opaon”, companion.

Another account, by Aeschylus, runs similarly but shuffles roles and parts: in his story, Pan’s father is Zeus and his mother is the nymph Kallisto. Pindar even claims his father is Apollos. But that’s inconsequential to us.

The satyr boy represented by Titian in this painting of Bacchus and Ariadne is sometimes interpreted as an infant Pan.

The satyr boy represented by Titian in this painting of Bacchus and Ariadne is sometimes interpreted as an infant Pan.This particular kind of fear Pan is able to inspire since his birth stems simply from his appearance: by showing a hybrid between man and beast, men are frightened in confronting their own bestiality, while Gods are very well aware of this human side and are simply amused at the god’s clever way of communicating this trait.

According to Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates was a great advocate of coming to terms with this dual nature: he addresses the god by calling him “dear”, and prays to him that he’ll be able to “become beautiful within”, by reconciling inner and outer worlds so that “what is in my possession outside me may be in friendly accord with what is inside”. Instead of being a god of excess and imbalance, Pan becomes a cosmic symbol of balance, a trait that will often surpass his nature as Phorbas.

Stoic philosophy will wholeheartedly embrace the idea of Pan as the embodiment of all elements and will see the god as an allegory of the universe.

Nicholas Poussin, Triumph of Pan (detail)

Nicholas Poussin, Triumph of Pan (detail)This aspect was also particularly significant in the Orphic cults, which will try to summon the god in number 10 of the 87 surviving hymns. You can read it here, and it’s rather beautiful.

By the end, the poet specifically mentions panic and says (in this translation by Thomas Taylor):

Come, Bacchanalian, blessed power draw near, fanatic Pan, thy humble suppliant hear,

Propitious to these holy rites attend, and grant my life may meet a prosp’rous end;

Drive panic Fury too, wherever found, from human kind, to earth’s remotest bound.

Porphyry, in his De abstinentia, warns that this evocation can be dangerous as many forms of what he starts to call “black magic”: worshippers are most likely to die of fright if the summoning is a success.

If you’re interested in Porphyry and his accounts on magic, as you should be, see here.

Perilous settings: the wilderness

The Homeric hymn also adds another element to the aspect of Pan as a god to be feared, by stressing the connection between his activities (and his cult) and wilderness. People are dancing dangerously close to the edge when worshipping this strange god from Arcadia.

“Through wooden glades

he wanders with dancing nymphs

who foot it on some sheer cliff’s edge“

This aspect is supported by archaeological findings, with a temple of Pan being in a gorge of the River Neda, near Mount Lykaion. and another famous place of worship being a cave near Athens. The most recent discovery of a temple to Pan was made in 2020 at the Nahal Hermon Nature Reserve in current Israel, below a Byzantine place of worship, and I urge you to see for yourself the sheer beauty of that natural setting. You can read about the finding here.

Wolves also constitute a significant bridge connecting the god with a fear of wilderness, and not just only through the geographical proximity with Mount Lykaion: as a protector of herds and a hunting god, it is believed he held some sort of power over packs.

Livy will take this connection further in Roman times, by linking Pan with Faunus and Faunus with Lupercus, the pastoral god celebrated in February with the revelries known as Lupercalia. They were a wolf festival allegedly instituted by the legendary Arcadian leader Evander and Justin himself connects them with Pan in his Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus when he says they were cults of “the Lycaean god, whom the Greeks call Pan and the Romans Lupercus”.

Andrea Camassei, “Lupercalia”

Andrea Camassei, “Lupercalia”The connection between fear and nature will be furtherly expanded upon by Francis Bacon, who will justify that Pan inspires terror because “nature has implanted fear in all living creatures”.

Inspired Panic

The most powerful way Pan manifests his terrifying trait is by inspiring supernatural and unmotivated fear without even showing himself.

A first account for this particular manifestation comes from the geographer Pausanias in his Guide for Greece where – possibly quoting a lost account by Hieronymus of Cardia – he recounts how the Galatians tried to invade Greece.

They camped where night overtook them retreating, but during the night they were seized by the Panic terror. (It is said that terror without a reason comes from Pan.) The disturbance broke out among the soldiers in the deepening dusk, and at first only a few were driven out of their minds; they thought they could hear an enemy attack and the hoof-beats of the horses coming for them. It was not long before madness ran through the whole force. They snatched up arms and killed one another or were killed, without recognizing their own language or one another’s faces or even the shape of their shields. They were so out of their minds that both sides thought the others were Greeks in Greek armor speaking Greek, and this madness from the god brought on a mutual massacre of the Gauls on a vast scale.

This incredible Roman statue is often called “The Dying Gladiator”, but the portrayed figure was identified as a Galatian around the XIX Century. The neck ring, interpreted as a sign of slavery, was jewellery in fashion amongst the so-called barbarians, or so the Romans thought.

This incredible Roman statue is often called “The Dying Gladiator”, but the portrayed figure was identified as a Galatian around the XIX Century. The neck ring, interpreted as a sign of slavery, was jewellery in fashion amongst the so-called barbarians, or so the Romans thought.Herodotus gives a similar account in his Histories while writing about the Persian Wars, though his account is most likely derivative.

The story inspired Robert Browning in his 1879 poem Pheidippides.

The most significant account for this behaviour possibly is to be found in Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe, one of the few surviving novels from ancient times.

In the story, fair Chloe is kidnapped by pirates and her betrothed Daphnis, traditionally the inventor of pastoral poetry, prays to the nymphs for help and promises to sacrifice a goat if the woman is saved.

But, when night began to fall and put an end to their enjoyment, suddenly the whole earth appeared in flames: the splash of oars was heard upon the waters, as if a numerous fleet were approaching. They called upon the general to arm himself: they shouted to each other: some thought they were already wounded, others lay as if they were dead. One would have thought that they were engaged in a battle by night, although there was no enemy.

After a night thus spent, a day followed even more terrible to them than the night. They saw Daphnis’s goats with ivy-branches, loaded with berries, on their horns: while Chloe’s rams and ewes were heard howling like wolves: Chloe herself appeared, crowned with a garland of pine. Many marvellous things also happened on the sea.

When they attempted to raise the anchors, they remained fast to the bottom: when the oars were dipped into the water to row, they snapped. Dolphins, leaping from the waves, lashed the ships with their tails, and loosened the fastenings. From the top of the steep rock overhanging the promontory was heard the sound of a pipe: but the sound did not soothe the hearers, but terrified them, like the blast of a trumpet.

Then, smitten with affright they ran to arms, and called upon their invisible enemies to appear: after which, they prayed for the return of night, hoping that it might afford them some relief. All who possessed any intelligence clearly understood that all the marvellous things that they had seen and heard were the work of God Pan, who was angry with them for some offence they had committed against him: but they could not guess the cause of it, for they had not plundered any spot that was sacred to him.

At last, however, at mid day, when their general had fallen asleep, not without the intervention of the Gods, Pan himself appeared to him and spoke as follows:

“O most impious and sacrilegious of men! what has driven your frenzied minds to such audacity? You have filled with war the country that I love, and have carried off the herds of cattle and flocks of sheep and goats entrusted to my care: you have dragged away from my altars a young girl whom Love has reserved for himself, to adorn a tale. Nay, you did not even respect the presence of the Nymphs, nor me, the great God Pan. Wherefore you shall never again see Methymna with such booty on board, nor shall you escape this pipe, which has so smitten you with alarm: I will swamp you in the waves and give you as food to the fishes, unless you speedily restore Chloe and her flocks, sheep and goats, to the Nymphs. Arise then, put ashore the young girl with all that I have mentioned: and then I will guide your course by sea, and Chloe’s by land.”

A translation of the work can be found here.

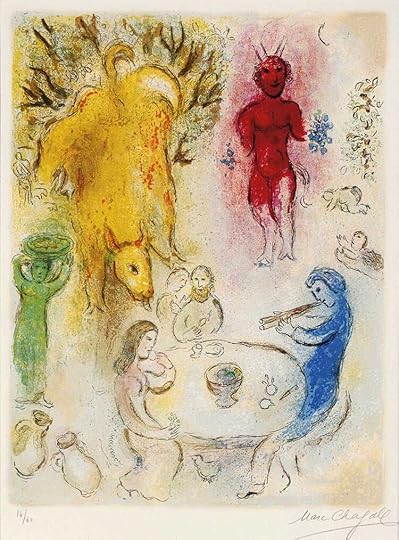

Pan is represented by Marc Chagall in one of his 42 coloured lithographs illustrating the story.

Lithograph by Marc Chagall

Lithograph by Marc ChagallInterestingly enough, the connection between Pan and the sea is not unheard of: according to Philippe Borgeaud, Pan Aktios was venerated by fishermen as the god of sea promontories and the connection might be found in how the goats are fond of salt.

The episode might also be an echo of a similar story in which Dionysus is kidnapped by sailors while disguised as a boy, and he breaks havoc on them as punishment.

Pan teaching Daphnis to play the flute (100 B.C., Pompeii)

Pan teaching Daphnis to play the flute (100 B.C., Pompeii)Daphnis and Chloe is a very influential work and will inspire three operas, one famous ballet and two movies.

Not all of them feature Pan’s direct intervention, but many of them try to incorporate the god in one way or the other.

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier was the first one to adapt the story to music and wrote a pastorale in 3 acts in 1747. It’s his Op. 102.

If you’re curious about it, I suggest you read it here.

You can listen to it and see the score here.

Another pastorale heroïque was written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (yes, he also wrote music) between 1774 and 1776, but he died in 1778 and he never finished. One can only guess what kind of philosophical significance he would have embued the story with.

Jacques Offenbach‘s 1860 one-act opérette, inspired by a theatrical adaptation of the original novel performed at the Théâtre du Vaudeville in 1849, sees Pan interpreted by a bass and the original performer in the March 27th premiere was Amable “Désiré” Courtecuisse, who will also play the part of Jupiter in the 1874 Orpheus in the Underworld.

This picture of Johann Nestroy playing Pan in 1870 gives an idea of the way the character is portrayed in the play.

This picture of Johann Nestroy playing Pan in 1870 gives an idea of the way the character is portrayed in the play.In this opérette, Pan is not so much a helper and is introduced as an element of tension: Daphnis insults him and he scorns the lovers, trying to win Chloe for himself. The resolution comes fortuitously, as the lascivious god accidentally drinks a sip of water from river Léthée and forgets all about his intent to pursue Chloe. Below you can see a reinterpretation by the Cambridge Youth Opera.

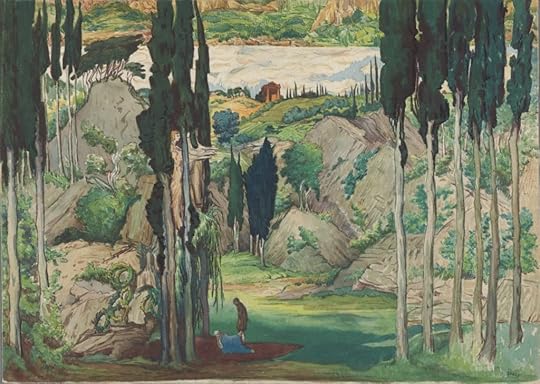

The ballet was composed in 1912 by no other than Maurice Ravel, for no other than Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and it was choreographed by that same Michel Fokine who worked on the solo dance The Dying Swan for Anna Pavlova from the highly influential last piece in Camille Saint-Saëns’ Carnival of the Animals. The set was designed by Léon Bakst and it must have been absolutely stunning.

One surviving set design

One surviving set designThe ballet, or symphonie choréographique as it’s preferably referred to, is far more faithful to the original novel, if compared to what Offenbach decided to do, and its strikingly impressionistic features are exemplified by the way both Nymphs and Pan are represented as outlines in the background, melting with the natural scenery, and come to life at night in a manifestation of the uncanny.

Pan in particular is invoked when pirates abduct unsuspecting Chloe, at the end of Part I.

Part II is the most powerful in this sense: at the pirates’ camp, Chloe is repeatedly forced to dance for her abductors, and frightening satyrs manifest just when she’s about to be violated by their leader.

The whole ballet with the score can be listened to here.

The passages where Ravel confronts himself with the uncanny manifestation of the supernatural are the Danse lente et mystérieuse des Nymphes, at the end of Part 1 as I was saying, and the end of Part 2. Most of these musical pieces will feature in what’s commonly known as Suite n.1, Fragments symphoniques de ‘Daphnis et Chloé’ (Nocturne—Interlude—Danse guerrière) developed by Ravel himself around 1911.

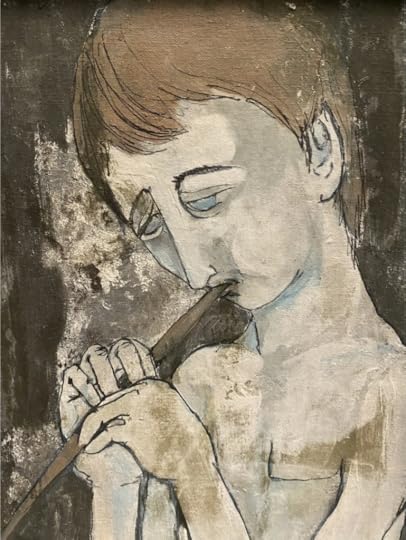

Panic through music

Though Pan’s ability to instil fear often doesn’t need any prompt, one shouldn’t forget his connection with music. The story of how he created his famous flute from reeds is well-known in Ovid‘s retelling: while pursued by the horned god, the nymph Syrinx was transformed into a reed on the banks of the River Ladon. While clutching what was left of the object of his desire, the reeds whistled with a haunting sound and Pan vowed to create a musical instrument out of her body. Objectification at its best.

Painting by Hans Makart

Painting by Hans MakartTheocritus is probably the first to connect Pan, fear and music in one of his Idylls, when the shepherd Thyrtis refuses to play his flute and says:

No, no man; there’s no piping for me at high noon.

I go in too great dread of Pan for that.

Virgil is possibly the one who took the musical aspects of Pan to absolutes. He however also adds interesting features in his Eclogues, by showing us a Pan with vermillion pigments smeared on his face.

Pan came, Arcady’s god, and we ourselves saw him,

crimsoned with vermilion and blood-red elderberries.

Talk about freaking out.

Pan and Syrinx from an XVII Century painting (on sale here)

Pan and Syrinx from an XVII Century painting (on sale here)The same Porphyry connects Pan with danger through music. As Eusebius quotes, he states nine people were found inexplicably dead and, when summoned, Apollo’s oracle stated this to be the cause:

“Lo! where the golden-horned Pan

In sturdy Dionysos’ train

Leaps o’er the mountains’ wooded slopes!

His right hand holds a shepherd’s staff,

His left a smooth shrill-breathing pipe,

That charms the gentle wood-nymph’s soul.

But at the sound of that strange song

Each startled woodsman dropp’d his axe,

And all in frozen terror gaz’d

Upon the Daemon’s frantic course.

Death’s icy hand had seiz’d them all,

Had not the huntress Artemis

In anger stay’d his furious might.

To her address thy prayer for aid.” ‘

As death befalls any mortal witnessing the true form of a god, we might as well argue that music is the true manifestation of Pan.

[image error] John Reinhard Weguelin, The Magic of Pan’s Flute (1905)Music brings us back to the Wind in the Willows too: the Mole and the Rat promptly forget seeing Pan, but a lingering music brings them back to the sweet sorrow of having been blessed and forgot about it.

The ultimate terror: a dying god

Lest the awe should dwell—

And turn your frolic to fret—

You shall look on my power at the helping hour—

But then you shall forget!

—forget, forget—

Lest limbs be reddened and rent—

I spring the trap that is set—

As I loose the snare you may glimpse me there—

For surely you shall forget!

Helper and healer, I cheer—

Small waifs in the woodland wet—

Strays I find in it, wounds I bind in it—

Bidding them all forget!

There’s another kind of fright that Pan can inspire, and probably one that will strike our modern minds more: Pan is the only ancient god who eventually dies. In his De Defectu Oraculorum, Plutarch recounts this terrifying event and swears that one Epitherses…

…designing a voyage to Italy, he embarked himself on a vessel well laden both with goods and passengers. About the evening the vessel was becalmed about the Isles Echinades, whereupon their ship drove with the tide till it was carried near the Isles of Paxi; when immediately a voice was heard by most of the passengers (who were then awake, and taking a cup after supper) calling unto one Thamus, and that with so loud a voice as made all the company amazed; which Thamus was a mariner of Egypt, whose name was scarcely known in the ship. He returned no answer to the first calls; but at the third he replied, “Here! here! I am the man.” Then the voice said aloud to him, “When you are arrived at Palodes, take care to make it known that the great God Pan is dead.”

Epitherses told us, this voice did much astonish all that heard it, and caused much arguing whether this voice was to be obeyed or slighted.

Detail from a 1960 painting by Martha Cassels (on sale here)

Detail from a 1960 painting by Martha Cassels (on sale here)Thamus, for his part, was resolved, if the wind permitted, to sail by the place without saying a word; but if the wind ceased and there ensued a calm, to speak and cry out as loud as he was able what he was enjoined.

Being come to Palodes, there was no wind stirring, and the sea was as smooth as glass. Whereupon Thamus standing on the deck, with his face towards the land, uttered with a loud voice his message, saying, “The great Pan is dead.”

He had no sooner said this, but they heard a dreadful noise, not only of one, but of several, who, to their thinking, groaned and lamented with a kind of astonishment. And there being many persons in the ship, an account of this was soon spread over Rome, which made Tiberius the Emperor send for Thamus; and he seemed to give such heed to what he told him, that he earnestly enquired who this Pan was; and the learned men about him gave in their judgments, that it was the son of Mercury by Penelope. There were some then in the company who declared they had heard old Aemilianus say as much.

Christian chronicles are of course delighted with this news and initially link Pan’s death with Christ exorcising all demons and false gods (see Eusebius, who draws this conclusion from the erroneous idea that Pan means “all”).

Oddly enough, later scholars will come to identify Pan with Christ, but that’s a different story.

For now, is there anything more terrifying than such a powerful creature consumed and fading away?

May 1, 2023

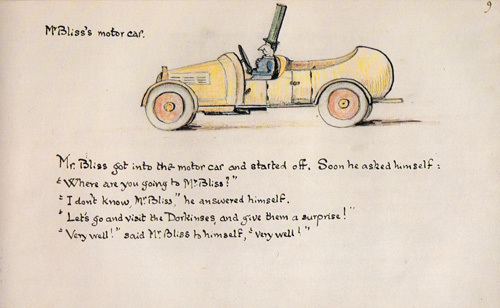

Mr Toad’s Motorcar

Well, I’ve joined a delightful group of people on Twitter and we’re engaged in a read-along of The Wind in the Willows. As you know, it’s one of my favourite books of all time, and a couple of years ago I produced some of my best recent articles surrounding my favourite chapters.

We’ve now reached Chapter VI and, as I already mentioned when talking about The Open Road, I’m not very fond of the character of Toad, and I’ve got a lot of reasons, some rational and some less so.

First of all, I’m all for a rascal as a main character but I don’t like the lack of accountability that seems to come with Toad. Grahame seems to think Toad’s imprisonment isn’t fair, and he depicts it as some sort of social injustice, where the accursed amphibian was behaving like a bully and using his money to wreak havoc on the innocent countryside.

Another reason I don’t like Toad has its roots in the genesis of these chapters.

Grahame wrote the book for (and a lot of times with) his son Alistair, but these particular chapters date back to a time when the relationship with his son had started to deteriorate. Alistair is often complaining his parents don’t come to visit him, and he reached a point where he changed his name to Robinson as a provocation for his father (Robinson was the name of the guy who tried to shoot him back in 1903).

Lots of biographers, from Alison Prince to Humphrey Carpenter, have speculated that Kenneth’s writings on Toad’s excesses were a way to patronise Alistair. Maybe that’s what I’m picking up when I instinctively dislike Toad so much. I loathe patronising writing.

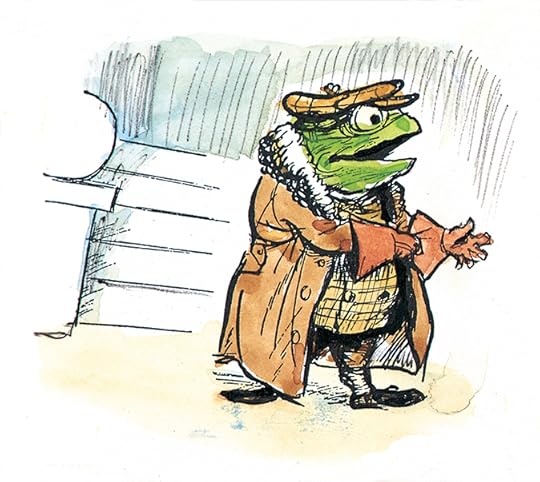

I do love, however, this illustration by Richard Johnson with Toad pretending to be driving his motor.

I do love, however, this illustration by Richard Johnson with Toad pretending to be driving his motor.What about Toad, then?…he would arrange bedroom chairs in rude resemblance of a motor-car and would crouch on the foremost of them, bent forward and staring fixedly ahead, making uncouth and ghastly noises, till the climax was reached, when, turning a complete somersault, he would lie prostrate amidst the ruins of the chairs, apparently satisfied for the moment.

Well, I come here neither to bury Toad nor to praise him. I have no interest in writing an article on why I dislike something. I prefer to focus on some interesting aspects of the chapter and make something nice out of it. So I’ve decided to talk about Toad’s car.

Grahame has a striking anti-industrial mentality, something that strongly ties him to Tolkien, and when dealing with Toad’s car he employs a couple of narrative tricks.

The first one is ridicule by exaggeration: when describing Toad’s attitude and attire, we’re drawn to believe Toad fancies himself a modern knight on his noble steed, in a very quixotic way, and his attire reflects his delusion: his “singularly hideous habiliments”, as Graham puts it, “transform him from a (comparatively) good-looking Toad into an Object which throws any decent-minded animal that comes across it into a violent fit”.

The very word “habiliments“, according to Annie Gauger in her excellent annotated edition, is a voluntary archaism: a version of the words appear in Sir Thomas Malory’s 1470s Morte d’Arthur, and in Raoul Lefévre‘s Histoire de Jason the word is specifically used to describe the vestiments of a chevalier:

Hauyng the forme and habylement of a knight.

It’s only natural that the word comes from the Old French habillement, and we still find it in the Italian very common “abbigliamento”, simply meaning “clothing”.

Grahame’s attitude towards technology is also conveyed through another trick: random capitalization. According to Gauger, the capitalization follows the Gothic style and it’s meant to convey how something familiar can be transformed into an Object of horror, into something that looms over humanity with its menacing shadow.

You’ll recognise a similar approach in Tolkien’s description of Saruman’s madness:

To take the more obvious example first, Saruman shows many signs of being equatable with industrialism, or technology. His very name means something of the sort. Searu in Old English (the West Saxon form of Mercian *saru) means ‘Device, design, contrivance, art’. Bosworth-Toller’s Dictionary says cautiously that often you cannot tell ‘whether the word is used with a good or with a bad meaning’.

— Tom Shippey. The Road to Middle-earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien created a new mythology

Toad’s ridiculous attire rarely gets illustrated properly, as many artists decide to represent faithfully what might have been the clothing of a bourgeoise “motorcarist” at the beginning of the last century. On the historical context surrounding the motorcar phenomenon, take a look at this excellent article.

E.H. Shepard’s take on ToadWhat about the car?

E.H. Shepard’s take on ToadWhat about the car?As I wrote in The Open Road, cars were made legal to run in England’s open roads in November 1896, with the Light Locomotives on Highways Act. The Act set the speed limit to 12 Mph, and superseded a previous Locomotive Act from 1865, which set a speed limit of 4 Mph and demanded that the car was preceded by a man on foot waving a red flag, which kind of defeats the purpose.

Roads and highways were often unpaved and unprepared for a superior speed, as people very rarely went racing in stagecoaches, although that was not unheard of.

Only nine models of cars were manufactured in the UK at the time when Grahame wrote The Wind in the Willows.

Albion 24/30 (1906–1912)

Albion 24/30 (1906–1912)The Albion 24/30 was the fourth model of car produced by Albion Motors, following the Albion 8, the Albion 12 and the Albion 16. It was a 4175 cc 4-cylinder and it would be the penultimate before the Scottish firm ceased its production of passenger cars in 1915.

Argyll 14 16

Argyll 14 16The first Argyll car was produced in 1899 at The Hozier Engineering Company, a factory founded by one Alex Govan. The car was fundamentally a Renault rip-off, though significant updates were made between 1902 and 1903. The Company changed its name to Argyll Motors Ltd. and eventually grew enough to have its own private railway line for supplying parts, opened in 1906 by John Douglas, 2nd Baron Montagu of Beaulieu, a big supporter of motorization in Great Britain. The Company went into decline when its founder died in 1907, and by 1908 it was being liquidated for bankruptcy. It would be revived in 1910, and called Argylls Ltd., but The Wind in the Willows’ outline would have been mostly completed, by then.

If Toad’s car was an Argyll, it could have been a model 14 16, one of the last produced before the Company’s downfall.

25/30 hp Austin open tourer

25/30 hp Austin open tourerThe Austin Motor Company Limited was founded in 1905 by Herbert Austin, as a spin-off of his successful Wolseley Sheep Shearing Machine Company based in London, after having built three of the first British cars in his spare time around 1895. The Company produced its first 31 cars in 1906. The following year, the number would go up to 180 and we might like to think that Toad was amongst one of them. If so, the car might have been the 25/30 hp open tourer.

Daimier 48hp

Daimier 48hpThe Daimler Motor Company Limited, which adjusted its name in 1910, is known as Britain’s oldest car manufacturer and is associated with the Royal Crown since it received patronage from Edward VII in 1908. Not that it would have made Badger change his mind on the subject, as we know. The 48hp from 1908 would certainly be a good candidate for Toad. And take a look at that red!

Humber 10/12

Humber 10/12The motor division of the already existing Humber Limited, which specialized in cycles, began in 1896 and struggled to take off the ground until the company was sold to Raleigh in 1932. The car production started with a prototype and nine exemplars, followed in November 1896 by an exhibition of one of those prototypes at the Stanley Cycle Show in London. Proof of this exhibition gives Humber the right to claim they produced the first motorcar on British soil.

At the time of The Wind in the Willows‘ writing, the Humber 10/12 and the Humber 30/40 were both in production.

Napier 60

Napier 60The D. Napier & Son Limited company built luxurious cars after 1895, when Montague Stanley Napier inherited a failing business from his father. A passionate car racer himself and a talented engineer, he sold his first six cars in 1900 sharp. They were an 8 hp and a 16 hp. On behalf of the novelist Mary Eliza Kennard, they entered the Thousand Miles Trial of the Automobile Club in 1904, being the first British car to do so, and they won their class with Kennard herself on board. The Company will later continue its tradition of women riding its cars: look Dorothy Levitt up if you don’t believe me.

I like to think this particular attention to racing might have drawn Toad’s attention.

If so, the purchased car might have been a Napier 60.

Rover 20

Rover 20Rover, as in Range Rover and Land Rover, is possibly the most influential Company amongst this bunch. Like Humber, it had been a bicycle manufacturing company since 1885, and moved to motorcars in 1904 although its first one was en electrical car from 1888, never produced. The first cars were designed by Edmund Lewis, who had previously worked at the Damier Company, and around 1907 we have three models being produced: the 8, the 6, the 10/12, the 16 and the 20.

If Toad was partial to any of these, it had to be the latter, a replica of the car which won the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy Race in 1906. It’s an open tourer, and it comes in red.

Vauxhall Motors Limited was founded in 1857 by a marine engineer, and initially produced boat engines. They tried their hands at motorcars in 1903, with 70 exemplars of a a 5hp single-cylinder model, and it had a tiller – like a boat – instead of a steering wheel. Maybe Rat would have approved of this particular motor, but a more sensible approach was taken in 1904.

Around 1907, its cars were being designed by a young talent named Laurence Pomeroy, 22 at the time, who designed a wonderful car during his boss’ vacation and swiftly took his place. Subversive and revolutionary, the Y-Type Y1 would perfectly fit Toad’s tastes. I unfortunately don’t have a picture for it.

Last but not least, Wolseley Motors produced some wonderful cars between their establishment in 1901 and 1905, but the two-cylinder Wolseley-Siddeley is the only one recent enough to be enthralling for a character such as Toad.

When Jan Needle wrote his sequel The Wild Wood in 1981, he wrote that Toad’s favourite car was an Armstrong Hardcastle Special Eight. Though Armstrong Siddeley was a British engineer group active in car design and spun off from Wolseley, I don’t think Armstrong Hardcastle has ever been a thing.

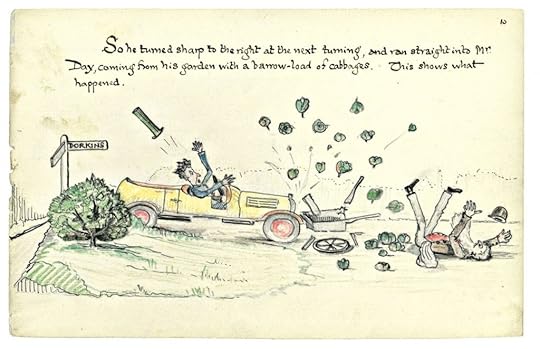

Eccentric Countrymen and their MotorcarsIt’s impossible to talk about Toad, and Grahame, to mention Tolkien and not draw attention to one of the strongest parallels between the two authors: Tolkien’s Mr Bliss. David Sander wrote an essay about it called Mr. Bliss and Mr. Toad: Hazardous Driving in J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Mr. Bliss” & Kenneth Grahame’s “The Wind in the Willows”, published on Mythlore in September 1997. Of course, you can’t read it unless you’re willing to sacrifice your firstborn to Jstor.

His cabbages!

His cabbages!Mr Bliss was written and illustrated by Tolkien around 1935 and never published, though he had submitted it to his publisher after The Hobbit, when people were harassing him for more tales.

According to Humphrey Carpenter in his biography:

The purchase of a car in 1932 and Tolkien’s subsequent mishaps while driving it led him to write another children’s story, ‘Mr Bliss’. This is the tale of a tall thin man who lives in a tall thin house, and who purchases a bright yellow automobile for five shillings, with remarkable consequences (and a number of collisions).

— H. Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography.

Though Beatrix Potter is more often quoted as the inspiration for this book, because of it being hand-illustrated and neatly bound, we can’t ignore the strong Toad vibes coming from the main character’s driving style.

After trading his silver bicycle for a yellow car, Mr Bliss’ misadventures include several accidents, but he’s immediately more sympathetic than Toad: Mr Bliss is just eccentric, not a bully, and every time he damages one of his neighbours he tries to make up for it. When he hits poor Mr Day and his barrow-load of cabbages, he haults him (and the cabbages) on his car, and does the same with Mrs Knight and her donkey-cart of bananas.

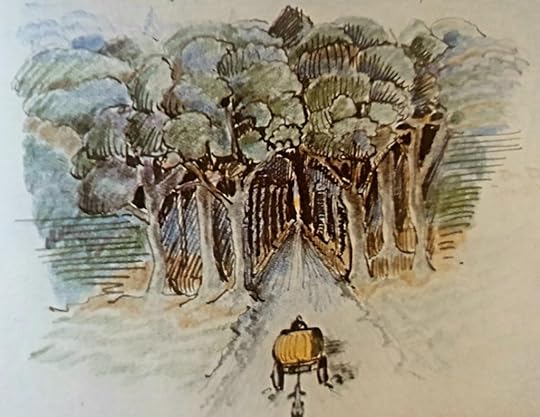

Mr Bliss’ adventures also involve crossing through a dark wood, delightfully illustrated in such a way that’s impossible not to think of Mirkwood (I wrote about its connections with The Wind in the Willows’ Dark Woods over here), the encounter with the three feral (teddy) bears Archie, Teddy and Bruno.

So Mr Bliss had to stop, because he could not get by without running over them.

“I like bananas,” said Teddy.

“And I like cabbages,” said Archie.

“And I want a donkey!”, said Bruno.

“And I want a motor-car,” they all said together.

“But you can’t have this motor-car, it’s mine”, said Mr Bliss.

“And you can’t have these cabbages — they’re mine”, said Mr Day.

“And you can’t have these bananas or this donkey — they’re mine”, said Mrs Knight.

“Then we shall eat you all up — one each!”, said the bears.

The woods will re-appear in all their glory a few pages further on, by night.

The woods will re-appear in all their glory a few pages further on, by night.Of course, the bears want a lift too, so now Mr Bliss’ car has Mrs Knight, Mr Day and three bears, with the donkey tied behind.

Thus encumbered, the car’s brakes don’t function properly, and the group sends it crashing against the Dorkinses’ garden wall.

Eventually, Mr Bliss is forced to have his wrecked car towed by the donkey and his neighbours’ ponies.

Eventually, Mr Bliss has his troubles with authorities too, as the whole neighbourhood blames him for their misfortunes though, to be honest, a fair share of the blame is to be laid on the bears. Sargeant Boffin, a name we’ll find again in the Shire, leads an expedition of furious townspeople who want compensation from the eccentric gentleman and storm his gate.

Mr Bliss is a man of honour, though, and the story ends with him breaking his money-box, and settling his debts with everybody, with an additional touch of community for a happy ending.

…Mr Bliss is quite happy. […] He drives a little donkey cart now, not a motor, and Sergeant Boffin salutes him every time he appears in the village.

I think we’ll have a hard time comparing his attitude to the one of Toad.