Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 50

October 3, 2023

#Spooktober 3 – A Haunting in Venice

I recently went to see this movie with some friends, and it’s perfectly fitting for the haunting season whether you like Banagh’s Poirot or not (I personally have mixed feelings).

It has a couple of things in common with the book of Spooktober Day 1, particularly a detective trying to shed rational light on apparently supernatural events and a general strength in the haunting atmosphere. The story draws from some of Agatha Christie’s short stories and the movie adaptation has a lot of things one might need on a Halloween night: a haunted palace in Venice, creepy masked people, the ghost of a girl who went mad and drowned herself (or did she?), ghosts of orphans out for revenge and an ancient curse, dead flowers and dead bees, a fake medium, a haunted doctor.

The mystery was very Agatha Christie: solidly built, a little obvious once you put the pieces together, with some nice twists you might not expect.The main weakness, as far as I’m concerned, was the pursue of horror movie tropes, but – CONFESSION TIME! – I really don’t like horror movies. I find them silly. And this movie was a little silly, at times, with its attempt at jump scares.October 2, 2023

#Spooktober 2 – The Surprising

I know this opinion might be unpopular with music connoisseurs, but I liked what Deep Purple did with their 2017 studio album Infinite.

My favourite track has to be “The Surprising”, and it’s a perfect feature for this Spooky Season with its haunting atmosphere, its mythical and biblical echoes. With the narrative voice intruding into the music, I often connect it with another track of the same album, “On Top of the World”.

It wasn’t quite the curse of Tutankhamen

Or the kiss of death from Judas in the night

And it felt so far beyond the blue horizon

Tempting me with transports of delight

And then the devil took my hand and said

Come along with me

There I was, wide awake and dreaming

Reaching out for something in the sky

But I could not control that trembling feeling

Everything I want is slipping by

And then the devil took my hand and said

Something you should see

I never knew what happened to my nightmare

Everything went dark that August day

And the eclipse was on the other side of somewhere

But I was on the upside of afraid

And then an angel took my hand and said

Come along with me

October 1, 2023

#Spooktober 1 – The Devil and the Dark Water

A murder on the high seas. A detective duo. A demon who may or may not exist.

I started reading this book based on the description provided by a friend, as it might prove inspirational for the novel I’m writing.

It’s set at sea, it has monsters, it has evil Dutchmen.

It’s 1634 and Samuel Pipps, the world’s greatest detective, is being transported to Amsterdam to be executed for a crime he may, or may not, have committed. Traveling with him is his loyal bodyguard, Arent Hayes, who is determined to prove his friend innocent.

But no sooner are they out to sea than devilry begins to blight the voyage. A twice-dead leper stalks the decks. Strange symbols appear on the sails. Livestock is slaughtered.

And then three passengers are marked for death, including Samuel.

Could a demon be responsible for their misfortunes?

With Pipps imprisoned, only Arent can solve a mystery that connects every passenger onboard. A mystery that stretches back into their past and now threatens to sink the ship, killing everybody on board.

What did I like about this book? Well, the atmosphere.

It’s an alternative history fiction more than historical fiction, as it admittedly takes a lot of liberties with both historical and fictional characters, and it almost entirely takes place on a ship returning from Batavia with a mysterious treasure on board. The haunting starts from the very first pages, and it never recedes. The sensation that people might be the real monsters is there since the beginning and doesn’t leave you.

Some of the characters are better than others, though I would say that they aren’t the book’s strongest suit.

Unfortunately, the real weakness is the mystery. When everything is revealed, inconsistencies in the early pages will have you twist your mouth, especially when scenes are described from the point of view of people who’s supposed to know better.

Still, it’s a good book and it makes for a nice haunting read.

Happy Spooktober!

Happy Spooktober! The best month of the best season of the whole year is here and I am… well, unprepared. And not happy. I’m still mourning the death of a dear friend, a person who had a tremendous impact in my life, I’m still living outside of my house, I haven’t started the renovation works yet, my work is on fire and my upstairs neighbour still claims she’s not responsible for the damages inflicted to me.

Still.

Life has to go on, and Jay would kick my ass if I fell back into depression, so I came up with a plan to give you your daily dose of #Spooktober posts, as it’s in the tradition of my Blog and Patreon, without engaging in projects that might be too ambitious for my current status.

October starts on a Sunday, so I decided to give you a different kind of media each day of the week, spooky of course, and ideally something that influenced the book I’m writing. Sometimes it will be a brief note, sometimes it might be longer stuff. I still don’t know. This I know, though.

#Sunday we’ll do Books

#Moonday we’ll do Music

#Tuesday we’ll do Movies

#Wednesday we’ll do Comics

#Thursday we’ll do Tv Shows

#Friday we’ll do Videogames

#Saturday we’ll do Visual Arts

All things spooky, of course. I’m almost done with the profiles of Italian baroque painters, and I have half a mind to resume with Mermaids on Monday, or to start publishing some notes around legendary, cursed places. But it’s all stuff we’ll see in November.

Enjoy, for now, and thanks for sticking with me through thick and thin.

September 29, 2023

Fede Galizia, the child prodigy

Daughter of the miniaturist Nunzio Galizia and born around 1578, Fede started working at 12 and she’s mostly known for her still lives, though she also worked on the human figure and religious subjects.

She started working very early in her father’s workshop, and her first attributed work is a portrait of the poet Gherardo Borgogni for a collection of his poems published in 1592. From contemporary sources, we also know she did portraits of her father and mother, two noblewomen who were their friends, and one portrait of the historian Paolo Morigia sitting at his desk: only the latter survived, and it’s currently preserved in Milan, her hometown. This particular portrait demonstrates an astonishing attention to expression and detail, echoing studies of Leonardo that were highly popular in Milan. If you look closely at the reading glasses held by the historian, you can see the reflection of a room with high windows and curtains.

My favourite work of hers has however to be her Judith with the head of Olophernes, a favourite subject of baroque female painters (I really wonder why…).

Aside from the vibrant expression of the elderly servant in the background, the stunning attention to detail on Judith’s jewellery and dress rivals contemporary masters such as Artemisia Gentileschi and Lavinia Fontana. Her studies of Correggio and Parmigianino clearly show in this masterpiece. The painting is cleverly signed on the blade.

Her still lives didn’t have the same naturalistic attention as works from her contemporary Giovanna Garzoni, and are more akin to paintings such as those produced by the masters of Nothern Europe. These paintings were destined for bourgeoise salons and sitting rooms of the middle class and their popularity was rising through what was going to be called “mannerism”. Her popularity was huge, though she studied by herself and never attended any art school, and it would be impossible not to see how quickly and cleverly she mastered a genre that was increasingly in demand by the rich patrons, following the turmoil created in the same genre by Ambrogio Figino and, most importantly, by Caravaggio.

. [image error]

[image error]  .

.

She died of the plague in 1630.

September 28, 2023

I miss you too

How do you explain it to normal people when a person meant the world to you but you lived an Ocean apart and you only met in real life a handful of times? I think you don’t, I don’t think you can, but I have to try.

I met Jay Zallan during my first Autodesk University in Vegas. I was a speaker, and he was… well, he was Jay. Striding across the Venetian, an ankle-length sleeveless black and white fur over flared trousers, metallic blue boots with high heels. He was carrying half a dozen beers in his hands while holding an impromptu lecture on innovation.

Like many others, I was star-struck by his unapologetic wit.

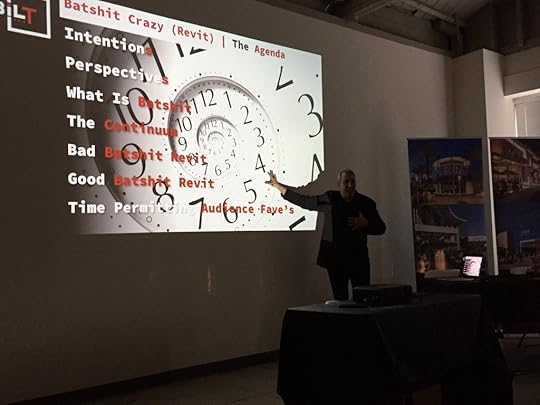

We connected at BILT Singapore, not many months later, when he gave an amazing lecture called Batshit Crazy Revit, which started as a collection of all the insane stuff people persist on doing with the software and quickly turned into an incredible dissertation on innovation, working ethics and the unsustainability of mediocrity.

T minus 15 minutes to Batshit Crazy (Revit) showtime @BILTevent Asia. Both freaking out and excited!!! See you on the other side ;)

— Jay Zallan (@JayZallan) March 30, 2017

This was a lesson I will never forget.

This was a lesson I will never forget.A few years later, I was in a very dark place, and few people knew that. He was one of them. It was my first time in his beloved Los Angeles, and he was my guide, my friend, my confidant. When I was thinking of falling through the cracks and disappear entirely, he held me and cradled me.

I will never know whether he was conscious of how much he meant to me that he was there.

And if you knew Jay, you can have a very clear picture of what we did: we fooled around like kids, and had very profound conversations, and talked philosophy about the construction industry, Lady Gaga, Angry Birds. That was Jay. A man who was able to change the temperature in the room with just a couple of words or a couple of rehearsed gestures, a man who was fully conscious of the impact we can have on others and yet I could never be sure whether he was correspondingly conscious of the impact he himself had on our industry. Of the impact he had on me.

I will forever be inspired by his persistence, by the pureness of his determination to pursue excellence, to drive forward innovation, to shake people from their prejudices and preconceptions. His very existence constantly admonished me that it’s possible to never give up, to hear the very same reactionary bullshit over and over again and still be pissed off as if it was the first time. He reminded me that life is not easy, when you’re not complacent and you’re unwilling to compromise on your beliefs, but it’s a path that’s worth pursuing, over and over again, regardless of the uncertainty, of the struggle, of the enemies you make along the way, of the pain it brings when yet another innovation project goes up in flames. And when the struggle never ends, and the world seems stuck, and nothing you do seems to matter, you can still find it in your soul to be an artist while you carry the fuck on.

So yeah, how do you explain it to normal people when a person meant the world to you but you lived an Ocean apart? I think you can’t. But when you have such a person, make sure they know. Pick up the phone and tell them. Hop on a plane, if you can, bask in the warmth of their company and make sure they know. Make sure they know how much they mean to you, even if normal people would never get it, because you might run out of chances to do it. I hope I did enough to tell Jay knew how much he meant to me.

Farewell, my friend.

You left a hole that won’t be filled.

September 22, 2023

Barbara Longhi, a painter in her family business

Born from an accomplished painter and contemporary of the better-known Lavinia Fontana, Barbara took her first artistic steps in her father’s workshop.

We know very little of her life: Vasari talks of her as you would for a child, though she was 14 years old at the time of his Lives‘ second edition… you could be old enough to marry but, apparently, not to be taken seriously as a painter. He says she drew really well and coloured prettily (inside the lines too, I bet). A more flattering mention of her comes from Muzio Manfredi, who dedicated her some verses in which he said she was a “wonderful painter” and her own father was “marvelling at her talent”. That’s better.

Regardless of her evident skills, she remained relegated to a provincial dimension as her father before her, and her works are mostly private commissions from the family’s circle of patrons. After her father’s death in 1580, the family workshop was taken over by Barbara’s brother Francesco and the business struggled for a while, but Barbara continued working, and her most gracious accomplishment possibly comes from this year: a bust of Saint Catherine of Alexandra, often presumed a self-portrait.

Saint Catherine of Alexandra (1580)

Saint Catherine of Alexandra (1580)She never married and continued working till her death, at the venerable age of 86 years, after drafting a testament in which she left her considerable possessions to her nephews. Amongst her more notable works, particularly interesting is the only non-religious subject I could dig up: a Lady with the Unicorn.

Her paintings are still being discovered all over Europe: only three years ago, a museum in Ravenna intercepted a grand Holy Family at an auction in Vienna.

Lady with the Unicorn

Lady with the Unicorn

September 15, 2023

Lucrina Fetti, whom she gets mixed up with her brother

If you’re passionate about baroque art, you might have heard of Domenico Fetti. Born in 1589, six years before his sister, he worked for the Gonzagas and Mantova’s churches are literally littered with his work, from the Cathedral’s apse to Sant’Orsola. He’s often described as a naturalist, influenced by both Caravaggio and Rubens, and celebrated for his attention to everyday scenes in his late Venetian production.

Domenico Fetti, Sleeping Girl

Domenico Fetti, Sleeping GirlHis sister Giustina, later known as sister Lucrina, didn’t have the luxury of painting everyday scenes, and she wouldn’t have known anything about it: in order to paint, she was forced to seek shelter within the austere walls of a monastery.

When she moved to Mantova in 1614, upon her bother’s hiring at the Gonzaga court, she already was a very talented painter and, through the quality of her work, she was able to attract the attention of Ferdinando Gonzaga, who paid 1500 crests for her to be admitted at the convent of Sant’Orsola. Founded in 1599 by Margherita Gonzaga, the convent was already recognised as a preferential place for noble women to continue their education and pursue their intellectual careers, albeit tied with the principles of the monastic life. None of her paintings survives from before her entering the monastery, but the production of sister Lucrina can be neatly divided into two categories: the religious subjects that were almost compulsory, and political portraits commissioned from outside the nunnery, as a testament of the diplomatic and political influence she exerted on behalf of the monastery.

Saint Margaret, often attributed to her and her brother, though there’s no proof he ever held a brush upon it.

Saint Margaret, often attributed to her and her brother, though there’s no proof he ever held a brush upon it.Her religious subjects decorated the church annexed to the monastery, and we count eleven of them, though some canvases are currently in private collections overseas.

When it comes to the portraits, her work distinctively included several influential ladies at court, such as Margherita Gonzaga, who briefly lived with Lucrina at the monastery. Both her portraits convey a sort of melancholic kindness, paired with austerity, wealth and elegance, and they’ve often been attributed to a generic “Mantuan school” though we possess clear proofs of their attribution to Plautilla. This is probably her more personal work.

Portrait of Margherita Gonzaga, often misattributed.

Portrait of Margherita Gonzaga, often misattributed.Another subject to whom she dedicated more than one painting was Eleonora Gonzaga, to whom she dedicated a smiling, highly political portrait on the occasion of her marriage with Emperor Ferdinando. If you compare this to the previous one, though they might seem similar in pose and effect, you can appreciate how Lucrina was able to fine-tune her style and expressivity to suit the need of the commission: if the first one is an intimate portrait, commissioned by a friend and intended for somewhat private quarters, the second one is part of a dowry and is meant to express the qualities of the new empress to both her husband and his court.

Lucrina Fetti, portrait of Eleonora I Gonzaga

Lucrina Fetti, portrait of Eleonora I GonzagaOther subjects for her portraits were Caterina de’ Medici, who also stayed at the convent for a span while awaiting her marriage with Duke Ferdinand in 1617, and Maria Gonzaga, the daughter of Francesco and Margherita di Savoia.

After the death of her friend and protector Margherita, all this highly political work paid off: the convent, and Lucrina herself, were wealthy enough to provide for their own protection and in 1632 we find testimony that Lucrina was self-sufficient enough to pay herself for her sister’s transfer to her convent. Her dowry had been previously paid by their brother Domenico, but Lucrina didn’t need him anymore. Domenico died in 1623, closely followed by their other male brothers Tommaso, Clemente and Vincenzo, all without heirs. There was no other chance but for Lucrina to inherit their father’s fortune, mostly from the Zuccaro Tower and other properties around the Duchy.

September 8, 2023

Plautilla Nelli, the abbess who tried to teach us collaboration

It is well known that one of the few ways you had to live as an artist in the XVI Century was by joining a nunnery. If you had the misfortune of being a woman, that is.

Some painters had the luxury of founding their own version of a monastery, as we saw for Orsola Maddalena Caccia. In contrast, others didn’t give a flying fuck and lived according to their own rules, like the controversy and frowned-upon Properzia de’ Rossi. Other women, however, were genuinely attracted to the philosophical aspects of spiritual life, and Plautilla Nelli is among them.

Born Pulissena Margherita, we know very little of her before she entered the Dominican convent of Santa Caterina in Cafaggio, one of the establishments revolving around the charismatic and controversial figure of Girolamo Savonarola. The preacher strongly recommended the importance of art in the spiritual and intellectual life of a devotee, and the nearby convent of San Marco could be proud of works by Beato Angelico. Santa Caterina was no less fervent, and Plautilla started her artistic work by illuminating texts and copying masterpieces by Fra Bartolomeo. She soon became a proficient painter and led an “officina sacra” inside the convent, teaching other girls the art of drawing, illuminating and painting.

Vasari briefly mentions her, and for a long time she was only known for works preserved inside the convent, including a glorious Last Supper.

She was head of the priory between 1563-65, 1571-73 and 1583-85, demonstrating a strong entrepreneurial spirit and great leadership. Her depictions of Saint Catherine always reflect the values of sternness and sobriety proposed by Savonarola’s preachings, and her compositions are rigorously sketched since the beginning of the development, but the finished paintings always show different hands at work, reflecting the collaborative and harmonious atmosphere she created inside the convent workshop.

This level of non-homogenous collaboration is rarely seen in paintings coming from the workshop of a master, and it’s clear that the goal here was not self-affirmation through prevarication but leading by example and nurturing artistic differences.

A lesson we’re struggling to learn even today.

September 1, 2023

Lucrezia Quistelli della Mirandola, artist and XVI Century detective

Lucrezia was born in Florence from a foreign noble family who had come to Tuscany to enter the Medici’s court: her father was Alfonso Quistelli della Mirandola, a judge, and Giulia Santi, daughter from a long line of humanists and authors. Vasari mentions her as “accomplished in both painting and drawing” for having diligently attended the school of one Alessandro Allori, a disciple of the court painter Agnolo Bronzino.

“Lamentation over the Dead Christ”, formerly attributed to Alessandro Allori

“Lamentation over the Dead Christ”, formerly attributed to Alessandro AlloriThis connection between Lucrezia and the artistic circle at the Medici court was probably facilitated by her father’s role as a literary patron: Bendetto Varchi, who will dedicate a sonnet to her marriage with Count Clemente Pietra in 1557, possibly was the one to introduce her to Alessandro Allori.

Lucrezia started taking lessons around 1555, aged 14, three years before her marriage, and it’s generally assumed she had access to sketches by Sofonisba Anguissola, which were very popular at the Florence court back in the day. The idea of being a woman painter must have been far from remote. Moreover, her husband was extremely progressive in his views: he had funded the publication of The Nobility of Women by Ludovico Domenichi in 1549, and was a great supporter of intellectual qualities in women, firmly opposing more traditional views that thought a woman could only be accomplished through the application to crafts such as embroidery.

With such premises, their marriage was a happy one: they soon moved to Palace Pandolfini, ideated and designed by Raffaello, and would proceed to have a grand total of eight children.

Their happiness was not to last.

As a decorated war veteran and the trusted man to Francesco I de’ Medici, Count Clemente was the target of court intrigue: in 1574, his rival Francesco Somma stabbed him with a poisoned blade, and the wound proved to be fatal after an agony of three days.

The poison was a refined mixture, not immediately recognised, and the killer tried to claim he acted in self-defence, so Lucrezia undertook an investigation, aided by the Grand Duke himself and by the court physicians. By analysing the strange coagulation of the blood around the wound, Lucrezia could finally prove that the murder of her husband had been premeditated. Through Giovanna d’Asburgo’s intervention, Cardinal Borromeo eventually dissuaded her from pursuing justice, and now I need a novel about this.

The only work we can attribute to her without any doubt is a marriage of Saint Catherine, commissioned and proudly displayed by her son Alfonso. The work was recently restored to its former glory.

Lucrezia Quistelli, The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (1576)

Lucrezia Quistelli, The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (1576)