Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 2

September 25, 2025

Fairytale Friday – The Awful Drunkard

Once there was an old man who was such an awful drunkard as passes all description. Well, one day he went to a kabak, intoxicated himself with liquor, and then went staggering home blind drunk. Now his way happened to lie across a river. When he came to the river, he didn’t stop long to consider, but kicked off his boots, hung them round his neck, and walked into the water. Scarcely had he got half-way across when he tripped over a stone, tumbled into the water—and there was an end of him.

Now, he left a son called Petrusha. When Peter saw that his father had disappeared and left no trace behind, he took the matter greatly to heart for a time, he wept for awhile, he had a service performed for the repose of his father’s soul, and he began to act as head of the family. One Sunday he went to church to pray to God. As he passed along the road a woman was pounding away in front of him. She walked and walked, stumbled over a stone, and began swearing at it, saying, “What devil shoved you under my feet?”

Hearing these words, Petrusha said:

“Good day, aunt! whither away?”

“To church, my dear, to pray to God.”

“But isn’t this sinful conduct of yours? You’re going to church, to pray to God, and yet you think about the Evil One; your foot stumbles and you throw the fault on the Devil!”

Well, he went to church and then returned home. He walked and walked, and suddenly, goodness knows whence, there appeared before him a fine-looking man, who saluted him and said:

“Thanks, Petrusha, for your good word!”

“Who are you, and why do you thank me?” asks Petrusha.

“I am the Devil. I thank you because, when that woman stumbled, and scolded me without a cause, you said a good word for me.” Then he began to entreat him, saying, “Come and pay me a visit, Petrusha. How I will reward you to be sure! With silver and with gold, with everything will I endow you.”

“Very good,” says Petrusha, “I’ll come.”

Having told him all about the road he was to take, the Devil straightway disappeared, and Petrusha returned home.

Next day Petrusha set off on his visit to the Devil. He walked and walked, for three whole days did he walk, and then he reached a great forest, dark and dense—impossible even to see the sky from within it! And in that forest there stood a rich palace. Well, he entered the palace, and a fair maiden caught sight of him. She had been stolen from a certain village by the evil spirit. And when she caught sight of him she cried:

“Whatever have you come here for, good youth? here devils abide, they will tear you to pieces.”

Petrusha told her how and why he had made his appearance in that palace.

“Well now, mind this,” says the fair maiden; “the Devil will begin giving you silver and gold. Don’t take any of it, but ask him to give you the very wretched horse which the evil spirits use for fetching wood and water. That horse is your father. When he came out of the kabak drunk, and fell into the water, the devils immediately seized him and made him their hack, and now they use him for fetching wood and water.”

Presently there appeared the gallant who had invited Petrusha, and began to regale him with all kinds of meat and drink. And when the time came for Petrusha to be going homewards, “Come,” said the Devil, “I will provide you with money and with a capital horse, so that you will speedily get home.”

“I don’t want anything,” replied Petrusha. “Only, if you wish to make me a present, give me that sorry jade which you use for carrying wood and water.”

“What good will that be to you? If you ride it home quickly, I expect it will die!”

“No matter, let me have it. I won’t take any other.”

So the Devil gave him that sorry jade. Petrusha took it by the bridle and led it away. As soon as he reached the gates there appeared the fair maiden, and asked:

“Have you got the horse?”

“I have.”

“Well then, good youth, when you get nigh to your village, take off your cross, trace a circle three times about this horse, and hang the cross round its neck.”

Petrusha took leave of her and went his way. When he came nigh to his village he did everything exactly as the maiden had instructed him. He took off his copper cross, traced a circle three times about the horse, and hung the cross round its neck. And immediately the horse was no longer there, but in its place there stood before Petrusha his own father. The son looked upon the father, burst into tears, and led him to his cottage; and for three days the old man remained without speaking, unable to make use of his tongue. And after that they lived happily and in all prosperity. The old man entirely gave up drinking, and to his very last day never took so much as a single drop of spirits.

The Russian peasant is by no means deficient in humor, a fact of which the Skazkas offer abundant evidence. But it is not easy to find stories which can be quoted at full length as illustrations of that humor. The jokes which form the themes of the Russian facetious tales are for the most part common to all Europe. And a similar assertion may be made with regard to the stories of most lands. An unfamiliar joke is but rarely to be discovered in the lower strata of fiction. He who has read the folk-tales of one country only, is apt to attribute to its inhabitants a comic originality to which they can lay no claim. And so a Russian who knows the stories of his own land, but has not studied those of other countries, is very liable to credit the Skazkas with the undivided possession of a number of “merry jests” in which they can claim but a very small share—jests which in reality form the stock-in-trade of rustic wags among the vineyards of France or Germany, or on the hills of Greece, or beside the fiords of Norway, or along the coasts of Brittany or Argyleshire—which for centuries have set beards wagging in Cairo and Ispahan, and in the cool of the evening hour have cheered the heart of the villager weary with his day’s toil under the burning sun of India.

It is only when the joke hinges upon something which is peculiar to a people that it is likely to be found among that people only. But most of the Russian jests turn upon pivots which are familiar to all the world, and have for their themes such common-place topics as the incorrigible folly of man, the inflexible obstinacy of woman. And in their treatments of these subjects they offer very few novel features. It is strange how far a story of this kind may travel, and yet how little alteration it may undergo. Take, for instance, the skits against women which are so universally popular. Far away in outlying districts of Russia we find the same time-honored quips which have so long figured in collections of English facetiæ. There is the good old story, for instance, of the dispute between a husband and wife as to whether a certain rope has been cut with a knife or with scissors, resulting in the murder of the scissors-upholding wife, who is pitched into the river by her knife-advocating husband; but not before she has, in her very death agony, testified to her belief in the scissors hypothesis by a movement of her fingers above the surface of the stream. In a Russian form of the story, told in the government of Astrakhan, the quarrel is about the husband’s beard. He says he has shaved it, his wife declares he has only cut it off. He flings her into a deep pool, and calls to her to say “shaved.” Utterance is impossible to her, but “she lifts one hand above the water and by means of two fingers makes signs to show that it was cut.” The story has even settled into a proverb. Of a contradictory woman the Russian peasants affirm that, “If you say ‘shaved’ she’ll say ‘cut.’”

In the same way another story shows us in Russian garb our old friend the widower who, when looking for his drowned wife—a woman of a very antagonistic disposition—went up the river instead of down, saying to his astonished companions, “She always did everything contrary-wise, so now, no doubt, she’s gone against the stream.” A common story again is that of the husband who, having confided a secret to his wife which he justly fears she will reveal, throws discredit on her evidence about things in general by making her believe various absurd stories which she hastens to repeat. The final paragraph of one of the variants of this time-honored jest is quaint, concluding as it does, by way of sting, with a highly popular Russian saw. The wife has gone to the seigneur of the village and accused her husband of having found a treasure and kept it for his own use. The charge is true, but the wife is induced to talk such nonsense, and the husband complains so bitterly of her, that “the seigneur pitied the moujik for being so unfortunate, so he set him at liberty; and he had him divorced from his wife and married to another, a young and good-looking one. Then the moujik immediately dug up his treasure and began living in the best manner possible.” Sure enough the proverb doesn’t say without reason: “Women have long hair and short wits.”

There is another story of this class which is worthy of being mentioned, as it illustrates a custom in which the Russians differ from some other peoples.

A certain man had married a wife who was so capricious that there was no living with her. After trying all sorts of devices her dejected husband at last asked her how she had been brought up, and learnt that she had received an education almost entirely German and French, with scarcely any Russian in it; she had not even been wrapped in swaddling-clothes when a baby, nor swung in a liulka. Thereupon her husband determined to remedy the short-comings of her early education, and “whenever she showed herself capricious, or took to squalling, he immediately had her swaddled and placed in a liulka, and began swinging her to and fro.” By the end of a half year she became “quite silky”—all her caprices had been swung out of her.

But instead of giving mere extracts from any more of the numerous stories to which the fruitful subject of woman’s caprice has given rise, we will quote a couple of such tales at length. The first is the Russian variant of a story which has a long family tree, with ramifications extending over a great part of the world. Dr. Benfey has devoted to it no less than sixteen pages of his introduction to the Panchatantra, tracing it from its original Indian home, and its subsequent abode in Persia, into almost every European land.

Next Friday: The Bad Wife

September 24, 2025

Notes on the Strike for Gaza

On Monday morning, I was travelling for work and I didn’t know if and when I’d be able to get home. It eventually took me around 12 hours for a 1-hour journey by train, because Italy was holding a general strike for Gaza. It involved transportation, public workers, schools and research, with a call for broader participation from other potential activists, such as influencers, and eventually escalated in a few cities, such as Turin (where I was) and Milan (where I was trying to get), with people blocking or trying to block the railway station and the few guaranteed trains.

I’m not complaining and, though I rarely condone this kind of “Sunday afternoon anarchism”, that’s not what I’m here to talk about. What I want to tackle is the question: does it make sense to strike in solidarity against war, and what result does it achieve? Shouldn’t strikes be an instrument of protest against your employer regarding working conditions?

From a legal perspective, the right to strike typically covers collective actions related to labour conditions or mutual aid, but solidarity strikes for causes like opposing war may face more complex legal restrictions depending on the country and the specific labour laws. That being said, there are historical and contemporary examples of solidarity strikes where workers stop work to protest broader social or political issues such as war, genocide, or human rights violations. These strikes aim to exert moral and political pressure beyond the workplace, often to support humanitarian causes or demand government action.

The debated effect of these strikes is always on the layfolk: people who need to go places and are negatively affected aren’t likely to develop political solidarity, social responsibility, or a collective conscience, even when the issue at hand is perceived as a grave social injustice or threat to democracy and peace.

That’s why I don’t think striking is wrong, but I do think it isn’t enough. It needs to be accompanied by a conversation on the topic, by a broader education on what’s happening and why we’re against it, on the nuances of being against genocide *and* against terrorism *and* against antisemitism. This responsibility to talk about these topics, today, falls to all of us. Let the strike be another reason we talk to each other.

Peace will prevail in the end.

Let us hope it isn’t because we killed each other in the process.

September 19, 2025

The Tales of Old Miura

The Tales of Old Miura (I racconti del vecchio Miura), published in Italy by Lindau, brings together short stories by Kidō Okamoto (1872–1939), a Japanese playwright and novelist best remembered for his contribution to kabuki theater and historical fiction.

Born in Tokyo during the Meiji era, Okamoto lived through Japan’s transition into modernity. He is best known for his detective fiction The Curious Casebook of Inspector Hanshichi and for Shuzenji Monogatari (The Mask Maker), a kabuki play still performed today, but his wider body of work — including novels, essays, and short stories — explores the conflict between individual desire and social duty.

In The Tales of Old Miura, this theme is distilled into concise episodes that reflect the values and anxieties of early 20th-century Japan. For today’s readers, the appeal lies less in plot than in the cultural insight these stories provide, offering a window into concepts of honor, dignity, and responsibility that shaped Japanese society.

The collection centers on characters undone by their obsessions, most often with art, occasionally with something as trivial as soy sauce. The ideas behind the stories are striking, and the prose is fluid, but the narratives tend to end abruptly, without the dramatic tension or resolution a modern reader might expect. They function less as entertainment and more as literary curiosities, fragments from a cultural world where passion could be both defining and destructive.

This collection is unlikely to satisfy those looking for gripping drama or neatly structured storytelling. Its value lies instead in the perspective it offers on the moral imagination of its time. Kidō Okamoto may not be as celebrated internationally as some of his contemporaries, but his work remains an evocative record of how literature once grappled with the destructive power of obsession.

The Caves of Steel

When Isaac Asimov published The Caves of Steel in 1954, he achieved something remarkable: he fused the detective novel with hard science fiction, using the tropes of noir to explore the sociological and technological anxieties of the future. This first entry in the Robots cycle introduces us to Detective Elijah Baley and his robotic partner R. Daneel Olivaw, laying the groundwork for Asimov’s long meditation on the place of automation in human society. More than a mystery, it is a sociological map of how humanity adapts — or fails to adapt — under pressure.

At the heart of The Caves of Steel lies the anxiety of automation. Earth is overpopulated, and robots represent both salvation and threat. On one hand, automation promises efficiency and productivity; on the other, it displaces workers, destabilizing the fragile balance of overcrowded urban life. Asimov dramatizes this tension through Baley’s suspicion of robots, which is less about their capabilities and more about what they symbolize: the erosion of stable employment and the fear of becoming obsolete.

As it turns out, this is not just about jobs but it about forced migration. The “caves” of the title are the steel-bound megacities where billions live in enclosed environments, cut off from open sky and farmland. Earthmen live packed together, dependent on rationed resources. The Spacers — descendants of earlier colonists who left Earth for new worlds — enjoy lives of abundance, space, and longevity. Migration here is not a choice but a dividing line: those who stayed behind live in scarcity, while those who left reaped the rewards of frontier expansion. It is a quiet but powerful tale of how technological change can redraw not only economies but geographies of privilege.

One of Asimov’s great insights in The Caves of Steel is the way he distinguishes between healthy traditionalism and dangerous obscurantism. Traditionalism appears in the everyday rituals of Earthmen: their reliance on familiar urban routines, their cultural bonds, and their suspicion of disruptive change. Obscurantism, however, emerges when this caution calcifies into outright rejection of progress, a refusal to engage with new realities even when survival depends on adaptation. Baley himself embodies this tension. He begins as a traditionalist, wary of robots and protective of Earth’s way of life, but over the course of the novel he learns to question those instincts. The anti-robot factions, in contrast, represent obscurantism: they would rather sabotage progress than face the possibility of change. This distinction feels particularly modern—Asimov anticipates the contemporary debate about whether resisting technological upheaval is prudence or denial.

What elevates The Caves of Steel beyond social commentary is the sheer brilliance of Asimov’s worldbuilding. The “caves” are not just a backdrop; they are an architectural expression of humanity’s adaptation to crisis. The steel domes enclosing cities create a claustrophobic environment where privacy is scarce, food is synthesized, and the very idea of fresh air is alien. These environments are described with a matter-of-fact precision that makes them disturbingly believable.

The contrast with the Spacers’ worlds — lush, spacious, technologically advanced — underscores Asimov’s knack for painting socio-technical ecosystems with just a stroke of the pen. He doesn’t just invent gadgets; he builds societies, complete with laws, prejudices, economies, and philosophies. Every element of his universe feels like the logical consequence of prior choices, mistakes, and adaptations.

Nearly seventy years later, The Caves of Steel remains startlingly relevant. Its portrayal of automation as both promise and threat mirrors our own debates about AI, robotics, and job displacement. Its vision of migration and inequality anticipates the tensions between those who can seize new opportunities and those left behind. Its exploration of tradition and obscurantism feels uncannily contemporary in an era of polarized debates about climate change, digitalization, and globalization.

And yet, beyond the themes, what makes the novel endure is its texture. Asimov builds a world so coherent that its social dilemmas feel inevitable, not invented. In the hands of a lesser writer, robots would be mere gimmicks. For Asimov, they are prisms refracting the deepest questions of human survival.

September 18, 2025

Fairytale Friday – The Cross-Surety

Once upon a time two merchants lived in a certain town just on the verge of a stream. One of them was a Russian, the other a Tartar; both were rich. But the Russian got so utterly ruined by some business or other that he hadn’t a single bit of property left. Everything he had was confiscated or stolen. The Russian merchant had nothing to turn to—he was left as poor as a rat. So he went to his friend the Tartar, and besought him to lend him some money.

“Get me a surety,” says the Tartar.

“But whom can I get for you, seeing that I haven’t a soul belonging to me? Stay, though! there’s a surety for you, the life-giving cross on the church!”

“Very good, my friend!” says the Tartar. “I’ll trust your cross. Your faith or ours, it’s all one to me.”

And he gave the Russian merchant fifty thousand roubles. The Russian took the money, bade the Tartar farewell, and went back to trade in divers places.

By the end of two years he had gained a hundred and fifty thousand roubles by the fifty thousand he had borrowed. Now he happened to be sailing one day along the Danube, going with wares from one place to another, when all of a sudden a storm arose, and was on the point of sinking the ship he was in. Then the merchant remembered how he had borrowed money, and given the life-giving cross as a surety, but had not paid his debt. That was doubtless the cause of the storm arising! No sooner had he said this to himself than the storm began to subside. The merchant took a barrel, counted out fifty thousand roubles, wrote the Tartar a note, placed it, together with the money, in the barrel, and then flung the barrel into the water, saying to himself: “As I gave the cross as my surety to the Tartar, the money will be certain to reach him.”

The barrel straightway sank to the bottom; everyone supposed the money was lost. But what happened? In the Tartar’s house there lived a Russian kitchen-maid. One day she happened to go to the river for water, and when she got there she saw a barrel floating along. So she went a little way into the water and began trying to get hold of it. But it wasn’t to be done! When she made at the barrel, it retreated from her: when she turned from the barrel to the shore, it floated after her. She went on trying and trying for some time, then she went home and told her master all that had happened. At first he wouldn’t believe her, but at last he determined to go to the river and see for himself what sort of barrel it was that was floating there. When he got there—sure enough there was the barrel floating, and not far from the shore. The Tartar took off his clothes and went into the water; before he had gone any distance the barrel came floating up to him of its own accord. He laid hold of it, carried it home, opened it, and looked inside. There he saw a quantity of money, and on top of the money a note. He took out the note and read it, and this is what was said in it:—

“Dear friend! I return to you the fifty thousand roubles for which, when I borrowed them from you, I gave the life-giving cross as a surety.”

The Tartar read these words and was astounded at the power of the life-giving cross. He counted the money over to see whether the full sum was really there. It was there exactly.

Meanwhile, the Russian merchant, after trading some five years, made a tolerable fortune. Well, he returned to his old home, and, thinking that his barrel had been lost, he considered it his first duty to settle with the Tartar. So he went to his house and offered him the money he had borrowed. Then the Tartar told him all that had happened and how he had found the barrel in the river, with the money and the note inside it. Then he showed him the note, saying:

“Is that really your hand?”

“It certainly is,” replied the other.

Every one was astounded at this wondrous manifestation, and the Tartar said:

“Then I’ve no more money to receive from you, brother; take that back again.”

The Russian merchant had a service performed as a thank-offering to God, and next day the Tartar was baptized with all his household. The Russian merchant was his godfather, and the kitchen-maid his godmother. After that they both lived long and happily, survived to a great age, and then died peacefully.

There is one marked feature in the Russian peasant’s character to which the Skazkas frequently refer—his passion for drink. To him strong liquor is a friend, a comforter, a solace amid the ills of life. Intoxication is not so much an evil to be dreaded or remembered with shame, as a joy to be fondly anticipated, or classed with the happy memories of the past. By him drunkenness is regarded, like sleep, as the friend of woe—and a friend whose services can be even more readily commanded. On certain occasions he almost believes that to get drunk is a duty he owes either to the Church, or to the memory of the Dead; at times without the slightest apparent cause, he is seized by a sudden and irresistible craving for ardent spirits, and he commences a drinking-bout which lasts—with intervals of coma—for days, or even weeks, after which he resumes his everyday life and his usual sobriety as calmly as if no interruption had taken place. All these ideas and habits of his find expression in his popular tales, giving rise to incidents which are often singularly out of keeping with the rest of the narrative in which they occur. In one of the many variants, for instance, of a widespread and well known story—that of the three princesses who are rescued from captivity by a hero from whom they are afterwards carried away, and who refuse to get married until certain clothes or shoes or other things impossible for ordinary workmen to make are supplied to them—an unfortunate shoemaker is told that if he does not next day produce the necessary shoes (of perfect fit, although no measure has been taken, and all set thick with precious stones) he shall be hanged. Away he goes at once to a traktir, or tavern, and sets to work to drown his grief in drink. After awhile he begins to totter. “Now then,” he says, “I’ll take home a bicker of spirits with me, and go to bed. And to-morrow morning, as soon as they come to fetch me to be hanged, I’ll toss off half the bickerful. They may hang me then without my knowing anything about it.”

In the story of the “Purchased Wife,” the Princess Anastasia, the Beautiful, enables the youth Ivan, who ransoms her, to win a large sum of money in the following manner. Having worked a piece of embroidery, she tells him to take it to market. “But if any one purchases it,” says she, “don’t take any money from him, but ask him to give you liquor enough to make you drunk.” Ivan obeys, and this is the result. He drank till he was intoxicated, and when he left the kabak (or pot-house) he tumbled into a muddy pool. A crowd collected and folks looked at him and said scoffingly, “Oh, the fair youth! now’d be the time for him to go to church to get married!”

“Fair or foul!” says he, “if I bid her, Anastasia the Beautiful will kiss the crown of my head.”

“Don’t go bragging like that!” says a rich merchant—“why she wouldn’t even so much as look at you,” and offers to stake all that he is worth on the truth of his assertion. Ivan accepts the wager. The Princess appears, takes him by the hand, kisses him on the crown of his head, wipes the dirt off him, and leads him home, still inebriated but no longer impecunious.

Sometimes even greater people than the peasants get drunk. The story of “Semilétka”—a variant of the well known tale of how a woman’s wit enables her to guess all riddles, to detect all deceits, and to conquer all difficulties—relates how the heroine was chosen by a Voyvode as his wife, with the stipulation that if she meddled in the affairs of his Voyvodeship she was to be sent back to her father, but allowed to take with her whatever thing belonging to her she prized most. The marriage takes place, but one day the well known case comes before him for decision, of the foal of the borrowed mare—does it belong to the owner of the mare, or to the borrower in whose possession it was at the time of foaling? The Voyvode adjudges it to the borrower, and this is how the story ends:—

“Semilétka heard of this and could not restrain herself, but said that he had decided unfairly. The Voyvode waxed wroth, and demanded a divorce. After dinner Semilétka was obliged to go back to her father’s house. But during the dinner she made the Voyvode drink till he was intoxicated. He drank his fill and went to sleep. While he was sleeping she had him placed in a carriage, and then she drove away with him to her father’s. When they had arrived there the Voyvode awoke and said—

“‘Who brought me here?’

“‘I brought you,’ said Semilétka; ‘there was an agreement between us that I might take away with me whatever I prized most. And so I have taken you!’

“The Voyvode marvelled at her wisdom, and made peace with her. He and she then returned home and went on living prosperously.”

But although drunkenness is very tenderly treated in the Skazkas, as well as in the folk-songs, it forms the subject of many a moral lesson, couched in terms of the utmost severity, in the stikhi (or poems of a religious character, sung by the blind beggars and other wandering minstrels who sing in front of churches), and also in the “Legends,” which are tales of a semi-religious (or rather demi-semi-religious) nature. No better specimen of the stories of this class referring to drunkenness can be offered than the history of—

Next Friday: The Awful Drunkard

September 17, 2025

Drawing Will Never Die

In the age of every Bill and Richard launching a digital crusade, we’ve come to believe that the tools of the past must bow to the technologies of the future. Like the sword giving way to the raygun, or the book to the neural implant, the sketchbook is often portrayed as a romantic relic to be displayed in an exhibition on “how we used to think.” In the architecture and construction industries, this narrative has taken a specific, almost dogmatic form: models will replace drawings. It’s preached at conferences and sold with every new tool that promises “drawing-less” delivery, and it’s been making the rounds here on LinkedIn for the past few months, so I thought I’d express more clearly some of the opinions I’ve been dropping around in comments.

Drawing isn’t dying because it’s misunderstood, and in fact, I don’t think it should.

1. The Myth of ObsolescenceDigitalisation poses as a disruptor, much like Prometheus bringing fire or Neo swallowing the red pill: it offers the power to see things differently, to do things that were never possible before and — why not — to break the system. But sometimes it also strips context, erases tacit knowledge, and flattens expression.

The myth of obsolescence in the construction industry stems from a flawed assumption: that efficiency is the ultimate virtue, and that interpretation is a bug to be eliminated rather than a feature to be embraced. In this view, drawings are cumbersome, ambiguous, and wasteful. Models are clean, rich, definitive. But anyone who has ever navigated a federated model with twelve linked files and no curation knows this isn’t the truth. We’ve traded legibility for data density, and have taught new specialists to read the new language, but what about everybody else?

In the same way a novel isn’t just a Word file and a screenplay isn’t just a CSV of camera movements, a drawing isn’t just a flat projection of geometry: it often is a visual script to understand, to persuade, and to dissent on something that’s being represented. So here’s what I’d like to bring you today:

Sketching by hand is not primitive; it is cognitive. The pencil is a neural interface that our bodies still understand better than any touchscreen.Drawings — particularly technical drawings — are layered, editorial, and intentional storytelling. If we believe raw models can speak for themselves, we lose the ability to narrate our designs because they can’t. At least, not yet.We need to build new frameworks of storytelling that bring the richness of drawing into the model, not by mimicking lines on a screen, but by rethinking how we annotate, filter, and perform our models.This is not a eulogy for drawing but a recruitment call for those who still believe that craft, clarity, and communication matter, that a single well-placed red line on a printout can still save a construction site, and that the rebellion isn’t against tools, but against mindsets.

Let’s draw the line. And then draw again.

2. The Pencil and the Brain: a Cognitive Affordance

2. The Pencil and the Brain: a Cognitive AffordanceIn an industry obsessed with digital transformation, we often forget that the first interface any designer ever masters isn’t a mouse or a touchpad, but a tool that leaves a mark with the flick of a wrist, connected to our brains in ways equally complex and, arguably, more beneficial.

From cave walls to construction details, drawing is not just a representation of ideas but the idea itself that forms in motion. In other words, the act of drawing is a cognitive process just as much as playing with LEGO: it externalises thought, creates feedback loops between mind and hand, and allows the brain to perceive its own intuitions. Drawing doesn’t just document knowledge but builds it, line by line.

Cognitive scientists call this “distributed cognition“, a theory stating that thinking might not be happen in the brain alone, but through interaction with physical tools and the environment. In this framework, the pencil becomes an extension of the mind — not metaphorically or metaphysically, but functionally — responding to our thoughts in real-time, and allowing immediate and nuanced action. Digital tools, for all their sophistication, aren’t sophisticated enough and fail to address this loop. Even the most advanced stylus lacks the haptic richness of graphite on paper, so far. Touchscreens delay response. Parametric constraints rigidify spontaneity. And while AI tools might promise to autocomplete facades or generate floor plans from prompts, they still aim for perfection. There’s no twitch, no tremor, no subconscious gesture that interrupts the algorithm and says: “wait — what if?” The work-in-progress feel of handcrafting still hasn’t been translated into digital tools — with the perhaps illustrious exception of VR sculpting for creating assets in cinema and video games — and it doesn’t seem to have any interest invested in doing so.

The relationship between Distributed Cognition and Human Computer Interaction isn’t my idea: see here for references.

The relationship between Distributed Cognition and Human Computer Interaction isn’t my idea: see here for references.Digital Tools enforce workflows, interfaces, and paradigms that reflect the way software wants us to think, not how humans naturally do, and the problem arises when we think they can be used in any part of the workflow, regardless and forget to ask what we lose when we stop drawing.

For starters, we lose spatial rehearsal, the mental simulation of space that sketching naturally supports. We lose motor memory, which links bodily motion to memory recall and ideation. We lose ambiguity, that beautiful, productive uncertainty that makes us reconsider a shape three times before committing. And we lose silence, the contemplative pause between marks where real creativity and problem-solving often spark.

To be clear: sketching is about access more than nostalgia. It’s a low-barrier, low-latency, high-bandwidth way of thinking, even for people who are highly proficient in digital tools. And right now, no CAD tool, no touchscreen, no gesture-controlled XR setup can rival it in early-stage design. Most digital interfaces are still built for execution, for refining what you’ve already imagined, not conjuring what doesn’t exist yet. So when we talk about man–machine interfaces, we must ask: do they truly enhance cognition, or just constrain it to what’s quantifiable? Because a pencil never asks you to pick a command before you draw. It just follows your thoughts.

Until digital tools can do that, we still need to draw, not as a backup, not as a compromise and not because digital tools are inferior, but because each part of the process needs its own tools and sketching is a first-class citizen in the design process, arguably the only one that still makes space for intuition, chaos, and surprise.

“I want to see, that’s why I draw.”

— Carlo Scarpa

Carlo Scarpa, Sketch for Castelvecchio (1962–1964)3. Drawings as Stories: the Semiotics of Technical Communication

Carlo Scarpa, Sketch for Castelvecchio (1962–1964)3. Drawings as Stories: the Semiotics of Technical CommunicationA drawing is not just a moment of geometry frozen in space: it’s visual storytelling where composition, emphasis, annotation, and silence work together to say “this is what matters”.

We like to think of construction documents as neutral, objective, but that’s never been true. Every drawing is an editorial decision: where you cut the section; what scale you choose based on the available and reliable information; what gets hatched, dimmed, tagged, or left blank. The margin notes, the revision clouds, the general annotation. All of these choices tell a story not just about the building, but about the priorities, risks, and logic behind it.

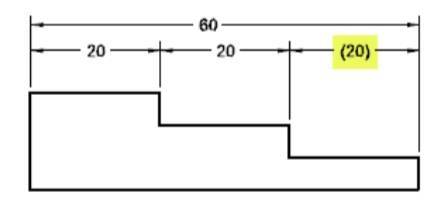

This drawing doesn’t just tell us dimensions: it tells us where to start from while building, and who gets left behind should that “60” be inaccurate. I’m not sure this gets taught in technical schools anymore.

This drawing doesn’t just tell us dimensions: it tells us where to start from while building, and who gets left behind should that “60” be inaccurate. I’m not sure this gets taught in technical schools anymore.In the past, we used to scribble in the margins. Then came CAD, a tool that mimicked the translation from hand-sketch to polished drawings, and there could be no more doodling. Then information modelling, which isn’t a mimic of anything.

That’s a mimic.

That’s a mimic.While digital tools made our drawings cleaner, faster, and easier to reproduce, they also made them quieter. We gained precision but lost the ability to be unsure, which is a fundamental need in many stages of design. Today’s tags and annotation objects carry data, yes, but they rarely carry tone. A model tag will tell you a wall type, but only an additional note will tell you that this wall is contentious, controversial, or critical to the client’s budget, and we’ve been avoiding those. The “Comment” parameter in Revit is being used for literally anything except… comments. And what about details? We live in the dream that you can slice a model whenever you want and get a 2D detail, but the right detail, handpicked and annotated, done right, can say: look here, this matters.

In semiotic terms, drawings are more than signifiers of objects: they are rhetorical devices, often there not to document but to persuade. A drawing can sell a concept in a design review or dismantle an argument in a coordination meeting. They don’t just show the “what”, but they should guide the “why,” and often preempt the “how.” When done right, 2D slices of a model offer curation because they’re selective, intentional, and graphic settings for 2D are equally important. They allow a parallel hierarchy to the one conveyed by categories: thick lines aren’t always for structure, thin lines aren’t always for finishes. In short, they offer visual grammar: dashes, dots, grey tones, callouts. These are not decorative: they are semiotic cues like facial expressions in a conversation. The moment we shift entirely to raw model data, we lose this grammar. We end up in a sea of equally weighted elements, where everything is visible and nothing is legible.

Let’s be honest: most federated models today are anti-narrative and we know that. That’s why the result of clash detection is… a report. Models are overloaded with data and underloaded with intent. The viewer opens the model and asks: “Where do I look?” And the model often responds with silence or, worse, with everything at once.

And you end up like this.

And you end up like this.We’ve taught our tools to deal with complexity, but we still have to teach them to speak. So this is the real loss: not just the romantic stroke of a pen but interpretive control, and the ability to choreograph how someone else enters the project story. Drawings do that: they lead the eye, create rhythm, raise questions, and offer answers. They structure conversation. If we want to move forward — and we should — then the question is not how do we replace drawings? But how do we preserve their storytelling power in a digital world?

Because without narrative, data is noise.

4. From Drawings to Model-Based Storytelling: a FrameworkSo we’ve drawn the line and made the case that drawings are more than lines, but if we’re not here to defend the past, we’re here to bury it. So we need to ask a harder question:

How do we tell stories inside a model?

The federated model, in its raw state, is just a vast, detailed, unmapped terrain. Without guidance, even experienced explorers get lost. Clients panic. Contractors click aimlessly. And design decisions get buried beneath layers of metadata and geometry. It’s not the presence of data that’s the problem: it’s the absence of storytelling structures. We’ve replaced curated drawings with unfiltered environments, and we’re surprised when communication breaks down. So what can we do?

4.1. Bridging the Gap: Storytelling as a LayerWhat if we stopped thinking of drawings and models as mutually exclusive, and instead treated narrative as a transversal layer that moves across both? In other words: what if we stopped asking “how do I annotate this model like a drawing?” and instead asked: how do I guide someone through this model as if it were a story?

Let me propose you three levels of narrative abstraction:

Spatial;Temporal;Interpretive.4.1.1. Spatial Narrative: Framing the SceneJust like cinematographers frame a shot, we must frame our models. This is already partially possible with viewpoints and sections but they’re often underused, untagged, or unstructured. So here’s my suggestion:

Curated viewpoints should be treated as narrative panels, not just bookmarks. Think comics, not coordinates.Named perspectives should include intent: not “View 17” but “Conflicting MEP run at Level 3 – Needs redesign.”View templates can carry symbolic weight that goes beyond traditional representation: bold colors for risk, transparency for future work, grayscale for frozen scope.We need to treat these views as scenes.

4.1.2. Temporal Narrative: Telling Time in a Static ModelDrawings often carry a ghost of history (erasures, revision clouds, phases) but the model doesn’t have to. How can we change that?

Phasing tools should be narrative devices, not just schedule outputs. They can show decision points, not just construction stages.Version tracking should be explicit in-model: not buried in CDE logs, but attached to the geometry itself, if it reflects a crucial design change that needs to be tracker. (“This wall changed in v3.2 because of fire egress.”)Decision breadcrumbs: we could tag objects with decision rationale. “Rotated 90° to align with daylight study from March 15th.” These become internal footnotes—storytelling within the model.Every object has a history. The model should let us read it.

4.1.3. Interpretive Narrative: Making Models Speak to HumansA model shouldn’t speak the same way to everyone. A contractor needs a different story than a sustainability consultant. To achieve that, we can build filters as personas:

a “Clash Detective” persona highlights tolerances, interference risks, unresolved issues;a “Client Walkthrough” persona mutes technical elements and foregrounds finishes, daylight, views;a “Heritage Officer” persona overlays protected elements, regulations, and constraints.Let users choose a narrative lens, and have the model reshape its voice accordingly.

Annotations, in this framework, are live comments, questions, perspectives. This is where we can integrate issue tracking, not as task lists, but as dialogic threads embedded in place.

Tools We Can Use TodayWe can start building this now with existing tools:

Templates and View Filters in Revit, Archicad, and Model View Definitions in the IFC scheme;saved Viewpoints with Notes in Navisworks, BIMcollab, BIM Track;colour-coding and transparency to visually differentiate urgency or narrative type;metadata tagging for design rationale, not just classification;naming conventions that communicate function, not just file structure.Tools aren’t the bottleneck: lack of imagination is, alongside lack of intent. We’ve been trained to use these tools for documentation, not narration, but the potential is there. We just need to reclaim it, and demand better.

Tools that aren’t quite thereIf you’re a software developer, let’s brainstorm: what could Model-Based Storytelling look like? Here’s where I’d like to invite you in:

what if BIM viewers had timelines, like video editors, showing the evolution of design choices? And no, I don’t mean it by forcing phases where you don’t have them. I mean a video rendition of versioning.What if models had voice-over tracks layered by stakeholder? I know, we all hate voice messages, but a certain kind of people would certainly interact more with the model if they could annotate it by voice, and we have the means to translate into text if you don’t want to pause your Ozzy Osbourne revival marathon to listen to them.What if VR walkthroughs had director’s commentary mode, highlighting story arcs and design intent?What if we used symbolic language in model space — icons, overlays, glyphs — to mark tone and status?Conclusion: a Pencil in One Hand, a Model in the OtherBottom line is: the narrative drawing vs modelling is a false dichotomy, born out of the same binary mindset that tells us innovation means erasure. But the best revolutions don’t delete the past: they build on it. Until we’re able to convey through models the same level of storytelling we can convey through technical drawings, those will be the foundation upon which models stand because without them we don’t know how to communicate.

September 14, 2025

Solaris

Some books demand to be read not only because they pioneered something new, but because, decades later, they remain unmatched in their brilliance. Stanisław Lem’s Solaris is one of those rare works that manages to be both the first of its kind and still the best at what it does.

First published in 1961 by the Polish author Stanisław Lem, Solaris quickly became a landmark in science fiction. Written during the Cold War, at a time when both the Soviet Union and the United States were fixated on conquering space, Lem turned his gaze elsewhere and – instead of rockets, moon landings, or interstellar empires – Solaris posed a question that remains as unsettling as ever: what happens when we encounter something truly alien, so different from us that we may never be able to understand it?

The book follows psychologist Kris Kelvin as he arrives at a research station orbiting the planet Solaris, which is covered entirely by a vast, sentient ocean. The ocean, in its incomprehensible intelligence, begins creating physical manifestations drawn from the subconscious of the humans studying it. Kelvin himself is confronted with the reappearance of his long-dead wife, a haunting presence that forces him to grapple not only with the mystery of the planet but with his own grief, guilt, and humanity.

Unlike much of the science fiction of its time, Solaris isn’t about technology as salvation or destruction. It’s about the limits of human understanding. Lem paints a picture of contact with an alien intelligence that refuses to fit into our frameworks of communication, science, or faith. The ocean of Solaris doesn’t give answers; it reflects us back at ourselves in ways that are often unbearable.This is why Solaris is more than a science fiction novel. It is also a psychological thriller and, ultimately, a philosophical meditation. The book unfolds in mirrored steps, escalating the tension until anguish becomes unavoidable. It leaves us with no clear resolution, only the creeping realization that the only thing we can truly study is ourselves.

September 11, 2025

Fairytale Friday – The Treasure

In a certain kingdom there lived an old couple in great poverty. Sooner or later the old woman died. It was in winter, in severe and frosty weather. The old man went round to his friends and neighbors, begging them to help him to dig a grave for the old woman; but his friends and neighbors, knowing his great poverty, all flatly refused. The old man went to the pope, (but in that village they had an awfully grasping pope, one without any conscience), and says he:—

“Lend a hand, reverend father, to get my old woman buried.”

“But have you got any money to pay for the funeral? if so, friend, pay up beforehand!”

“It’s no use hiding anything from you. Not a single copeck have I at home. But if you’ll wait a little, I’ll earn some, and then I’ll pay you with interest—on my word I’ll pay you!”

The pope wouldn’t so much as listen to the old man.

“If you haven’t any money, don’t you dare to come here,” says he.

“What’s to be done?” thinks the old man. “I’ll go to the graveyard, dig a grave as I best can, and bury the old woman myself.” So he took an axe and a shovel, and went to the graveyard. When he got there he began to prepare a grave. He chopped away the frozen ground on the top with the axe, and then he took to the shovel. He dug and dug, and at last he dug out a metal pot. Looking into it he saw that it was stuffed full of ducats that shone like fire. The old man was immensely delighted, and cried, “Glory be to Thee, O Lord! I shall have wherewithal both to bury my old woman, and to perform the rites of remembrance.”

He did not go on digging the grave any longer, but took the pot of gold and carried it home. Well, we all know what money will do—everything went as smooth as oil! In a trice there were found good folks to dig the grave and fashion the coffin. The old man sent his daughter-in-law to purchase meat and drink and different kind of relishes—everything there ought to be at memorial feasts—and he himself took a ducat in his hand and hobbled back again to the pope’s. The moment he reached the door, out flew the pope at him.

“You were distinctly told, you old lout, that you were not to come here without money; and now you’ve slunk back again.”

“Don’t be angry, batyushka,” said the old man imploringly. “Here’s gold for you. If you’ll only bury my old woman, I’ll never forget your kindness.”

The pope took the money, and didn’t know how best to receive the old man, where to seat him, with what words to smooth him down. “Well now, old friend! Be of good cheer; everything shall be done,” said he.

The old man made his bow, and went home, and the pope and his wife began talking about him.

“There now, the old hunks!” they say. “So poor, forsooth, so poor! And yet he’s paid a gold piece. Many a defunct person of quality have I buried in my time, but I never got so from anyone before.”

The pope got under weigh with all his retinue, and buried the old crone in proper style. After the funeral the old man invited him to his house, to take part in the feast in memory of the dead. Well, they entered the cottage, and sat down to table—and there appeared from somewhere or other meat and drink and all sorts of snacks, everything in profusion. The (reverend) guest sat down, ate for three people, looked greedily at what was not his. The (other) guests finished their meal, and separated to go to their homes; then the pope also rose from the table. The old man went to speed him on his way. As soon as they got into the farmyard, and the pope saw they were alone at last, he began questioning the old man: “Listen, friend! confess to me, don’t leave so much as a single sin on your soul—it’s just the same before me as before God! How have you managed to get on at such a pace? You used to be a poor moujik, and now—marry! where did it come from? Confess, friend, whose breath have you stopped? whom have you pillaged?”

“What are you talking about, batyushka? I will tell you the exact truth. I have not robbed, nor plundered, nor killed anyone. A treasure tumbled into my hands of its own accord.”

And he told him how it all happened. When the pope heard these words he actually shook all over with greediness. Going home, he did nothing by night and by day but think, “That such a wretched lout of a moujik should have come in for such a lump of money! Is there any way of tricking him now, and getting this pot of money out of him?” He told his wife about it, and he and she discussed the matter together, and held counsel over it.

“Listen, mother,” says he; “we’ve a goat, haven’t we?”

“Yes.”

“All right, then; we’ll wait until it’s night, and then we’ll do the job properly.”

Late in the evening the pope dragged the goat indoors, killed it, and took off its skin—horns, beard, and all complete. Then he pulled the goat’s skin over himself and said to his wife:

“Bring a needle and thread, mother, and fasten up the skin all round, so that it mayn’t slip off.”

So she took a strong needle, and some tough thread, and sewed him up in the goatskin. Well, at the dead of night, the pope went straight to the old man’s cottage, got under the window, and began knocking and scratching. The old man hearing the noise, jumped up and asked:

“Who’s there?”

“The Devil!”

“Ours is a holy spot!” shrieked the moujik, and began crossing himself and uttering prayers.

“Listen, old man,” says the pope, “From me thou will not escape, although thou may’st pray, although thou may’st cross thyself; much better give me back my pot of money, otherwise I will make thee pay for it. See now, I pitied thee in thy misfortune, and I showed thee the treasure, thinking thou wouldst take a little of it to pay for the funeral, but thou hast pillaged it utterly.”

The old man looked out of window—the goat’s horns and beard caught his eye—it was the Devil himself, no doubt of it.

“Let’s get rid of him, money and all,” thinks the old man; “I’ve lived before now without money, and now I’ll go on living without it.”

So he took the pot of gold, carried it outside, flung it on the ground, and bolted indoors again as quickly as possible.

The pope seized the pot of money, and hastened home. When he got back, “Come,” says he, “the money is in our hands now. Here, mother, put it well out of sight, and take a sharp knife, cut the thread, and pull the goatskin off me before anyone sees it.”

She took a knife, and was beginning to cut the thread at the seam, when forth flowed blood, and the pope began to howl:

“Oh! it hurts, mother, it hurts! don’t cut mother, don’t cut!”

She began ripping the skin open in another place, but with just the same result. The goatskin had united with his body all round. And all that they tried, and all that they did, even to taking the money back to the old man, was of no avail. The goatskin remained clinging tight to the pope all the same. God evidently did it to punish him for his great greediness.

A somewhat less heathenish story with regard to money is the following, which may be taken as a specimen of the Skazkas which bear the impress of the genuine reverence which the peasants feel for their religion, whatever may be the feelings they entertain towards its ministers. While alluding to this subject, by the way, it may be as well to remark that no great reliance can be placed upon the evidence contained in the folk-tales of any land, with respect to the relations between its clergy and their flocks. The local parson of folk-lore is, as a general rule, merely the innocent inheritor of the bad reputation acquired by some ecclesiastic of another age and clime.

Next Friday: The Cross-Surety

September 10, 2025

Against Amnesia: Walking with Ignazio Gardella

Ignazio Gardella (born Mario in 1905 – 1999) was one of the most incisive and restless figures of Italian modernism, a man who managed to embody both rigour and a certain dose of rebellion (though never enough to convince him not to serve the Fascists, for which we should never condone anyone).

Born in Milan into a dynasty of engineers and architects, Gardella never settled for a single stylistic formula: his career stretched from rationalist beginnings in the 1930s, through the experimental postwar reconstruction years, to a late capacity for contextual and civic architecture. What makes him especially relevant to Milan is that the city itself became both his testing ground and his laboratory: his buildings are scattered across its urban fabric like traces of a long conversation between modernity and memory.

A Milanese Humanist of Modernism

A Milanese Humanist of ModernismUnlike many of his contemporaries who either resisted the weight of history or drowned in it, Gardella had a subtle way of weaving past and present. His Casa Tognella along Parco Sempione, with its clean rationalist lines tempered by refined detailing, is a lesson in how to innovate without erasing. His Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (friendly known as PAC) is another symbol: bombed in 1993, later restored under his guidance, it embodies the idea that architecture can absorb trauma and still stand as testimony.

The Pavillion for Contemporary Art in Milan, friendly known as PAC

The Pavillion for Contemporary Art in Milan, friendly known as PACThis duality — innovation with continuity — is what Milan desperately needs to remember today, as it pushes forward with unrelenting urban transformations that too often sacrifice legacy in the name of progress.

A Web of Influences and FriendshipsGardella was not isolated: he belonged to a generation of architects who debated, disagreed, and built Milan together. With Luigi Caccia Dominioni, he shared both professional ground and a spirit of discreet elegance: architecture as urban civility, where modern buildings coexist with the texture of historic streets. Together, they founded Azucena, one of the first design companies of our age.

With Luciano Visconti, the famed film director, Gardella found another kind of kinship: Visconti’s cinematic realism and Gardella’s architectural clarity both sought to reveal the dignity of the ordinary, grounding modernity in lived experience.

Why am I upset?Ah, you’ve noticed. It’s only the last of a series of operations that almost completely destroyed the modernist masterpieces in the historical fair area, now Citylife, with its beautiful park and fucking ugly skyscrapers. The operation was strongly pushed by the last right-wing administration we had in the city — the major being one of the women who destroyed public schools before merrily moving on to try the same on my city — and its victim was the historical fair with the exception of some cherry-picked buildings which were deemed worthy of survival. These buildings, even at the time, did not include the groundbreaking aeronautical pavilion, for instance, because its author wasn’t well-known and well-connected.

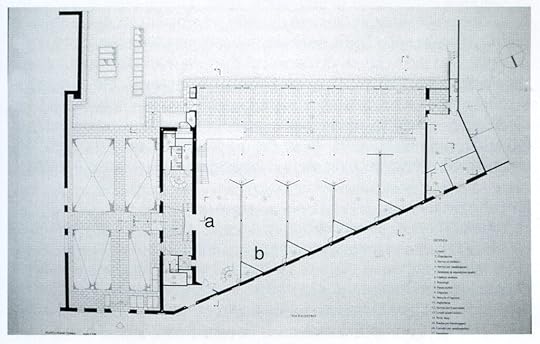

A shot of the historical fair

A shot of the historical fairIn late July 2025, Milan witnessed another erasure: the Agriculture Pavilion (Padiglione dell’Agricoltura) designed by Ignazio Gardella and erected in 1961. What once stood along via Gattamelata as the modernist hallmark of the post‑war expansion of the Fiera Campionaria — its graceful “Palazzata” façade articulated in Vicenza stone, dark red clinker, and a double‑height glass wall with vivid red‑framed steel — was reduced to rubble to make way for a new RAI Production Centre set to open in 2029. Despite its inclusion in the Lombardy cultural heritage inventory, the Pavilion lacked the 70‑year threshold required by preservation law to prevent demolition. Thus, legal protection fell short, and history was deemed expendable. You can read more about it here. They’re as angry as I am.

This was not an unexpected collapse of structure or identity, but a planned amputation, part of the area’s redevelopment strategy that has already swept away most of the old Fiera complex, replaced by the towering silhouettes of CityLife. The Pavilion’s disappearance marks the final chapter of the classic Fiera Campionaria in that corner of the city. No, Palazzo delle Scintille doesn’t count.

Palazzo delle Scintille was here before the historical fair, as a sports facility. Besides, it’s liberty, which means it’s respectable.

Palazzo delle Scintille was here before the historical fair, as a sports facility. Besides, it’s liberty, which means it’s respectable.Milan, in its rush to reinvent itself, often brands these gestures as “riqualificazione urbana,” as if rejuvenation can only happen by erasing layers of the past. Yet when that impulse goes unchecked, it becomes self-sabotage: a city that refreshes its façade at the expense of its memory. The loss of Gardella’s Pavilion is not just an architectural casualty, but a civic one, a rupture in the continuum that binds one generation’s forward thinking to the next generation’s sense of place.

This is why this week I take you through the city with an urban itinerary that touches what’s left of Gardella’s legacy. Take my hand, wear your best shoes, and let’s hit the road.

Core Landmarks (in the City)Stop 1: Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (PAC), Via PalestroThe PAC was commissioned in the early 1950s as part of a postwar civic initiative to provide Milan with a dedicated venue for contemporary art exhibitions. Located on Via Palestro, right next to the Villa Reale and its historic gardens, the building was deliberately conceived as a modern counterpart to the neoclassical fabric around it. In 1993, the pavilion was heavily damaged by a bombing targeting the adjacent Villa Reale. Its destruction could easily have meant the disappearance of another piece of Milan’s architectural memory, but the city chose to restore it and turned again to Gardella himself to lead the work. I studied the building as an architectural student and you have a longer description in this old blog post.

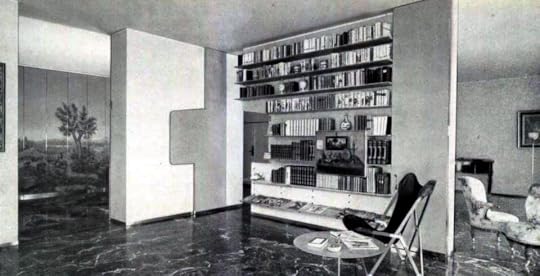

The pavilion’s interiors.

The pavilion’s interiors.Gardella conceived the pavilion as a light, rational structure: an elegant steel skeleton, brick infill, glass expanses, and a modular grid system that allowed flexibility for exhibitions. Unlike the monumental rhetoric of fascist-era pavilions, this was a human-scaled, transparent, and welcoming civic space. After the bombing, Gardella (with his son Jacopo) restored and subtly reinterpreted the building. He preserved its core spirit — the transparency, the rational grid, the fluidity of the interiors — while reinforcing and modernising the structure. The restoration itself became an architectural statement: a refusal to let terror erase culture.

Another shot of the interiors.

Another shot of the interiors.The significance of the PAC lies not only in its architecture but in what it represents for the city. Gardella managed to merge rationalist rigour with a uniquely Milanese sense of refinement, producing a building that is modern without ever becoming brutal, transparent without lapsing into naïveté. Standing beside the Villa Reale, the pavilion engages in a dialogue across centuries: neoclassical monumentality converses with postwar modernity, each reinforcing the other rather than cancelling it out. When that dialogue was tested by tragedy, its restoration transformed the PAC into a civic symbol of resilience, proof that Milan could absorb violence without relinquishing memory. In this sense, the pavilion is not simply a container for contemporary art but one of the city’s strongest metaphors for memory as resistance. Today, as other modernist landmarks fall under the banner of “renewal,” the PAC stands as a reminder that progress can also mean restoration, care, and continuity, that the future need not be built on erasure.

Stop 2: Casa Tognella (Casa al Parco), Via Paleocapa / Via Ricasoli

Stop 2: Casa Tognella (Casa al Parco), Via Paleocapa / Via RicasoliBuilt between 1947 and 1953 on the edge of Parco Sempione, Casa Tognella, often called Casa al Parco, was one of the first private residential buildings to rise in Milan after the devastations of the Second World War. Commissioned by the industrialist Antonio Tognella, it occupies a privileged site overlooking the park, where the scars of bombings and demolitions left both a void and an opportunity. The building immediately attracted attention because of its bold departure from traditional apartment houses of the time, presenting itself as a manifesto of the city’s rebirth. I’m not particularly fond of this one, but the main facade surely has merit for a student.

My favourite facade.

My favourite facade.Ignazio Gardella approached the project with a strong sense of experimentation. Instead of reproducing the decorative formulas of prewar Milanese housing, he designed a slender, transparent structure defined by its large ribbon windows, floating terraces, and a rhythmic façade grid that was both rational and elegant. Technically, it was one of the earliest uses in Milan of pilotis and curtain walls, while still maintaining the compositional discipline of traditional Italian palazzi. Gardella treated the building almost as a laboratory of new urban dwelling: open plans, flexible interiors, and a façade that broke with masonry heaviness in favour of lightness and permeability.

The interiors were absolutely stunning.

The interiors were absolutely stunning.The importance of Casa Tognella lies in its role as a threshold between eras. It is not simply a modernist block transplanted onto a historic park edge. Gardella’s façade, suspended between rigour and lightness, asserts that Milan could move forward without ignoring the weight of its setting. Its presence alongside Parco Sempione is almost polemical: housing could be both modern and urbane, technical and refined. In a city that was eager to rebuild quickly, Gardella insisted on a form of architecture that was neither nostalgic nor reckless, but attentive: a rare quality in the postwar climate.

What makes the building resonate today is precisely this refusal to choose between past and future. Casa Tognella demonstrates that the dignity of everyday housing can embody architectural innovation, and that context is not a burden but an interlocutor. In the activist framework of this itinerary, it serves as an early warning against the dangers of amnesia. Just as the PAC later proved that restoration could be progress, Casa al Parco already showed that innovation could coexist with continuity. In both cases, Gardella’s lesson is the same: Milan’s strength lies in its ability to transform without erasing.

Stop 3: Casa in Via Marina 3–5 (Casa Bassetti), 1960–62

Stop 3: Casa in Via Marina 3–5 (Casa Bassetti), 1960–62In the early 1960s, Milan was consolidating its image as Italy’s financial and cultural capital, and the area around Via Marina, bordering the Giardini Pubblici, became a prime location for high-profile residences. Unlike the urgent, experimental postwar works such as Casa Tognella, the Via Marina commission arose in a moment of relative economic stability and increasing demand for refined, prestigious housing. Gardella collaborated here with architect Roberto Menghi, another key figure of Milanese modernism, to create a building that responded not only to the functional needs of its inhabitants but also to the delicate urban setting facing one of the city’s green lungs.

[image error] Again, not my favourite building.Gardella’s hand is evident in the building’s measured balance between modern typology and Milanese sobriety. The structure is articulated through vertical partitions and horizontal ribbon windows, producing a façade that is rigorous yet softened by the rhythm of projecting loggias and set-back surfaces. Materials are chosen with care: exposed concrete and brick are combined with refined finishes, ensuring that the building feels both solid and elegant. Inside, apartments are organised with flexibility and light, designed to satisfy the expectations of a growing bourgeoisie who wanted contemporary spaces without giving up domestic comfort.

The Via Marina residence marks a turning point in Gardella’s trajectory, revealing his ability to adapt modernist principles to a more mature, almost classical language of urban dwelling. Where Casa Tognella had shocked the Milanese landscape with its radical lightness, Via Marina tempers innovation with composure, establishing a relationship with the tree-lined avenue opposite.

Its significance lies in this subtle negotiation. The building demonstrates that Milanese modernism was never about stylistic purity alone, but about dialogue with the city’s atmosphere: its rhythms, its materials, its understated elegance. For an activist itinerary, Via Marina is the reminder that preservation is not only about monuments but also about the quieter layers of the city’s architectural palimpsest. If works like these are allowed to vanish under speculative redevelopment, Milan loses not just individual buildings but the continuity of its civic character. Gardella shows us here that the future of housing in Milan could be modern and prestigious without severing its ties to the urban and cultural fabric that gave it meaning.

Stop 4: Casa in Via Marchiondi, c. 1950s

Stop 4: Casa in Via Marchiondi, c. 1950sThe postwar years in Milan were marked not only by the reconstruction of cultural landmarks and prestigious residences but also by an urgent demand for affordable housing. Entire swathes of the city’s periphery were being developed to host working- and middle-class families migrating from rural Lombardy and southern Italy. It was in this climate that Gardella contributed to the Via Marchiondi housing project, one of several experimental social housing complexes in the expanding northern districts of the city.

Take a look at the interiors.

Take a look at the interiors.Gardella approached the project with the same seriousness he reserved for more prestigious commissions. Instead of creating anonymous blocks, he sought to combine functionality with dignity, designing buildings that were structurally efficient but still responsive to light, ventilation, and the articulation of communal space. The façades, though simple, were carefully proportioned, relying on rhythm and subtle variation in fenestration to avoid monotony. His intervention in Via Marchiondi reveals his commitment to the ethical role of architecture: even mass housing deserved refinement, and even repetition could hold beauty if guided by proportion.

On the project, he worked with Anna Castelli Ferrieri, and their relationship will leave a beautiful testament in the Kartell headquarters and museum, just outside Milan, still being used today.

The Via Marchiondi housing block is thus significant because it illustrates how Gardella understood architecture as a continuum, not a hierarchy. He did not reserve innovation for villas or museums; he extended it to the everyday homes of ordinary citizens. In this sense, Giardini d’Ercole is as political as it is architectural. It demonstrates that the city’s peripheries were just as deserving of thoughtful design as its elegant boulevards.

For Milan today, which often treats peripheral housing as disposable, this lesson is crucial. To safeguard buildings like Marchiondi is to recognise that collective memory does not reside only in landmarks or in glossy downtown interventions, but also in the quieter architectures that shaped the daily life of thousands. Losing them to speculation or neglect is another form of civic amnesia. Gardella’s insistence on designing dignity into even the most constrained briefs is an activist manifesto in itself: the city betrays its future when it erases the fabric of its ordinary past.

Stop 5: Casa di riposo “Antonietta Biffi”, Via dei Ciclamini 34 (1965–70)

Stop 5: Casa di riposo “Antonietta Biffi”, Via dei Ciclamini 34 (1965–70)During the 1960s, Milan was experiencing rapid economic growth, but also the demographic transformations that came with it: an ageing population, new forms of welfare, and the need to rethink facilities for social care. In this context, the Casa di riposo “Antonietta Biffi”, located in the Barona district on Via dei Ciclamini, emerged as a crucial experiment. Instead of relegating the elderly to anonymous or hospital-like institutions, the project aimed to offer a residential environment that combined functionality with a sense of belonging and dignity.

Gardella’s contribution was to apply his hallmark balance of rationality and humanity. The building is organised around courtyards and green spaces, allowing residents to remain in touch with nature and light — a deliberate rejection of the claustrophobic typologies common to many care facilities of the period. The façades are sober but carefully articulated, using brick and concrete in measured proportions, while interiors are structured to foster both privacy and communal interaction. The architecture here does not patronise or isolate its inhabitants; instead, it acknowledges ageing as a phase of life deserving spaces of beauty, comfort, and continuity with the city.

Stop 6: Università Bocconi, Milan (Aula Magna and New Building, 1949–1956)In the aftermath of World War II, Milan was not only rebuilding its physical infrastructure but also reasserting itself as a capital of knowledge and innovation. The Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi, which had been founded in 1902, needed new spaces to host its growing student population and reaffirm its role as a hub for Italy’s economic and managerial elite. The commission to design the Aula Magna and associated teaching facilities was given to Ignazio Gardella in the late 1940s.

The site was delicate: Bocconi’s historic campus lay close to the city centre, and the architecture had to reconcile institutional gravitas with the modern identity that Milan was beginning to project in the 1950s.

Gardella designed the Aula Magna and the adjoining blocks between 1949 and 1956. The project is emblematic of his ability to calibrate modernist principles with contextual sensitivity. The Aula Magna presents itself as a rational, monumental hall, with a façade of measured verticality and stone cladding, designed to convey the seriousness of the institution. Inside, however, Gardella allowed a warmer, more dynamic atmosphere to emerge, thanks to careful attention to acoustics, light, and materials.

His design provided Bocconi with not only a functional lecture hall but also a symbol of intellectual prestige — an architectural statement that learning was central to Milan’s reconstruction and modernisation. Unlike the residential experiments of Casa Tognella or Via Marina, Gardella embraced a more formal language, but without lapsing into authoritarian monumentality. Instead, the building retains a sense of accessibility and openness that reflects the democratic ideals of postwar education.

The Bocconi commission is significant because it illustrates Gardella’s ability to scale his architectural ethos to an institutional level. The Aula Magna is not simply a box for lectures but an urban forum, where the city’s future leaders gathered and where Milan declared its ambition to be an intellectual and economic powerhouse.

What makes it resonate today is its balance of gravity and lightness: monumental enough to embody authority — because the weak ego of Academia apparently demands that — yet still deeply rooted in human scale and experience. In the activist framework of this itinerary, the Aula Magna stands as proof that Milan once invested in architecture as a civic gesture, not just a private asset. At a time when universities increasingly outsource their identity to anonymous international models, Gardella’s Bocconi project shows that educational buildings can carry cultural memory as well as functional purpose. To preserve and value this work is to defend the idea that institutions, too, are part of the city’s collective history — and that their architecture should express continuity rather than rupture.

Studio Nonis recently touched up on the interiors (see here).

Stop 7: Residenze Mangiagalli II, Via De Predis 11 (1950–1952)

Stop 7: Residenze Mangiagalli II, Via De Predis 11 (1950–1952)Alongside prestigious commissions in the city centre, a vast program of residential expansion was underway to provide housing for middle-class families. The Mangiagalli II residences, located in the northwestern quadrant of the city near Via De Predis, formed part of this effort. They were conceived not as isolated buildings, but as fragments of a new neighbourhood fabric, combining efficiency with livability.

The project was entrusted to a team that included Ignazio Gardella and Franco Albini, one of my favourite designers of that time. Their collaboration exemplified a shared vision: that rationalist architecture could be humanised and adapted to the everyday needs of urban life.

Within this collective framework, Gardella contributed his characteristic attention to façade rhythm and proportional refinement. Where Albini leaned on structural clarity, Gardella nuanced the elevations with materials and details that softened the impact of repetition. The blocks were organised to maximise light, ventilation, and views, avoiding the monotony that too often plagued postwar housing. He sought to give dignity to each dwelling unit while still ensuring the overall coherence of the complex.

The project is therefore less about individual architectural flourish and more about the careful orchestration of everyday architecture, a field in which Gardella excelled, treating even the most modest commissions with the seriousness of a cultural act.

The Mangiagalli II residences are significant because they embody the ethical turn of Milanese modernism in the early 1950s. Unlike luxury projects such as Casa Tognella or Via Marina, here the challenge was to design affordable, efficient housing without surrendering quality. Gardella’s façades, disciplined yet varied, show that repetition need not mean anonymity. The complex becomes a lesson in how to humanise density, producing an urban fabric that could stand the test of time.

Stop 8: Stazione di Milano Lambrate (1983–1999)

Stop 8: Stazione di Milano Lambrate (1983–1999)By the 1980s, Milan was no longer the city of postwar reconstruction, but a metropolitan hub grappling with the demands of mobility and decentralisation. The Lambrate railway station, located in the northeastern quadrant of the city, had long been an important node on the line connecting Milan with Venice and beyond. A decision was made to replace the old facility with a modern passenger station that could serve the growing volume of daily commuters.