Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 4

August 12, 2025

Bepi from the Ice

During this summer break, I started reading a charming little book I bought in Venice at the remarkable venue Libreria Acqua Alta (High Waters Bookshop): it’s a small volume whose title roughly translates to Mysteries of the Lagoon and Tales of Witches, by one Alberto Toso Fei.

It’s a collection of tales, grounded in landmarks and venues, some of them are tales from folklore, and some others are more recent anecdotes, such as the ones connecting Rodolfo Valentino to the Hotel Excelsior or Lord Byron to the Armenian church.

The Armenian church is also connected to the history of a young Bolshevik dude from Georgia, who arrived in 1907 and was welcomed as a buddy by the local community of anarchists, who gave him the nickname of Bepi del Giass (Bepi from the Ice in the local vernacular).

Bepi tried his hand at ringing the bells for the local Armenian church, but wouldn’t listen when the patriarch asked him to ring the bells according to the Latin rite, and persisted in ringing them in the Orthodox way. Eventually, they presented him with an ultimatum, and Bepi went back to Russia, just in time to participate in the revolution.

Cool.

Except there’s a twist.

“A few years later he became… General Secretary of the Communist Party and leader of the Soviet Union with the nickname “Little Father” and the universally known pseudonym “Stalin”, Iosif Stalin.“

That was… unexpected.

August 9, 2025

The Ghost Tower

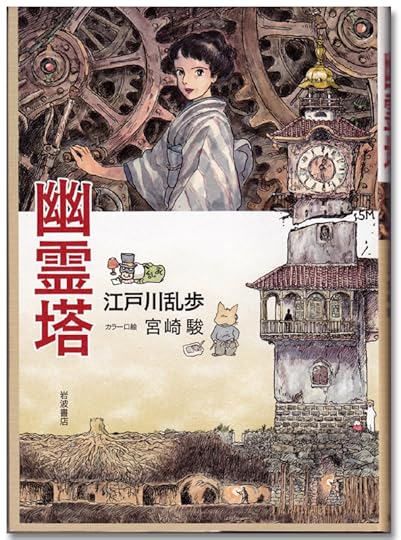

Remember Edogawa Ranpo? The Japanese author of horror and thrilller who gave us the strange and haunting Panorama Island. After reading the graphic novel, I read the novel last summer, and apparently it became tradition that I read Japanese horror when I’m on the traditional 10-days summer vacation with my friends, and this year I grabbed a relatively new Italian translation of Yūrei tō, translated as La Torre Spettrale – Ghost Tower.

The novel is better known for being the inspiration behind some elements of Miyazaki’s Castle of Cagliostro, and it has an intricate story. Published in 1936 after appearing serially in a magazine, it springs from Ranpo’s wish to make more accessible a work by Ruikō Kuroiwa – The Spectral Tower – published in 1900 also serially. According to what Ranpo himself writes as a preface to one of the chapters, the style of the original work would have been too old-fashioned for modern readers and nevertheleess he thought a waste to forget such a marvellous work just for the language barrier.

A connection has also been suggested between this work and Alice Muriel Williamson‘s A Lady in Grey, which I’m not familiar with: apparently Kuroiwa saw a movie from 1920 with scenes of an adaptation, and sought out the original work to make it available into Japanese, making significant adaptation in its translation.

Regardless of its intricated origin, the novel remains one of the most brilliant Japanese mystery novels I’ve read, with a complex mixture of traditional elements and values (family honor and vengeful ghosts being the more obvious), a touch of romanticism with cursed beauties and poisons, plain horror with elements such as the house of spiders, and strikingly modern elements that wouldn’t be out of place in a contemporary sci-fi thriller.

Highly recommended.

Note: there’s also a comic book version with drawings by Miyazaki himself.

August 6, 2025

Werewolves Wednesday: The Wolf-Leader (24)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter XXIV: Hunting Down the Were-WolfThibault had got well ahead of the dogs, thanks to the precaution he had taken of making good his escape at the first note of the bloodhound. For some time he heard no further sound of pursuit; but, all at once, like distant thunder, the baying of the hounds reached his ears, and he began to feel some anxiety. He had been trotting, but he now went on at greater speed, and did not pause till he had put a few more leagues between himself and his enemies. Then he stood still and took his bearings; he found himself on the heights at Montaigue. He bent his head and listened the dogs still seemed a long way off, somewhere near the Tillet coppice.

It required a wolfs ear to distinguish them so far off. Thibault went down the hill again, as if to meet the dogs; then, leaving Erneville to the left, he leaped into the little stream which rises there, waded down its course as far as Grimau-court, dashed into the woods of Lessart-Abbesse, and finally gained the forest of Compiegne. He was somewhat reassured to find that, in spite of his three hours’ hard running, the steel-like muscles of his wolf legs were not in the least fatigued. He hesitated, however, to trust himself in a forest which was not so familiar to him as that of Villers-Cotterets.

After another dash of a mile or so, he decided that by doubling boldly he would be most likely to put the dogs off the scent. He crossed at a gallop all the stretch of plain between Pierrefond and Mont-Gobert, took to the woods at the Champ Meutard, came out again at Vauvaudrand, regained the stream by the Sanceres timber floatage, and once more found himself in the forest near Long-Font. Unfortunately for him, just as he reached the end of the Route du Pendu, he came across another pack of twenty dogs, which Monsieur de Montbreton’s huntsman was bringing up as a relay, for the Baron had sent his neighbour news of the chase. Instantly the hounds were uncoupled by the huntsman as he caught sight of the wolf, for seeing that the latter kept its distance,

he feared it would get too far ahead if he waited for the others to come up before loosing his dogs. And now began the struggle between the were-wolf and the dogs in very earnest. It was a wild chase, which the horses, in spite of their skilled riders, had great difficulty in following, a chase over plains, through woods, across heaths, pursued at a headlong pace. As the hunt flew by, it appeared and disappeared like a flash of lightning across a cloud, leaving behind a whirlwind of dust, and a sound of horns and cries which echo had hardly time to repeat. It rushed over hill and dale, through torrents and bogs, and over precipices, as if horses and dogs had been winged like Hippogriffs and Chimeras. The Baron had come up with his huntsmen, riding at their head, and almost riding on the tails of his dogs, his eye flashing, his nostrils dilated, exciting the pack with wild shouts and furious blasts, digging his spurs into his horse’s sides whenever an obstacle of any kind caused it to hesitate for a single instant. The black wolf, on his side, still held on at the same rapid pace; although sorely shaken at hearing the fresh pack in full pursuit only a short way behind him, just as he had got back to the forest, he had not lost an inch of ground. As he retained to the full all his human consciousness, it seemed to him impossible, as he still ran on, that he

should not escape in safety from this ordeal; he felt that it was not possible for him to die before he had taken vengeance for all the agony that others made him suffer, before he had known those pleasures that had been promised him, above all for at this critical moment his thoughts kept on running on this before he had gained Agnelette’s love. At moments he was possessed by terror, at others by anger. He thought at times that he would turn and face this yelling pack of dogs, and, forgetting his present form, scatter them with stones and blows. Then, an instant after, feeling mad with rage, deafened by the death-knell the hounds were ringing in his ears, he fled, he leaped, he flew with the legs of a deer, with the wings of an eagle. But his efforts were in vain; he might run, leap, almost fly, the sounds of death still clung to him, and if for a moment they became more distant, it was only to hear them a moment after nearer and more threatening still. But still the instinct of self-preservation did not fail him; and still his strength was undiminished; only, if by ill luck, he were to come across other relays, he felt that it might give way. So he determined to take a bold course so as to out-distance the dogs, and to get back to his lairs, where he knew his ground and hoped to evade the dogs. He therefore doubled for the second time. He first ran back to Puiseux, then skirted past Viviers, regained the forest of Compiegne, made a dash into the forest of Largue, returned and crossed the Aisne at Attichy, and finally got back to the forest of Villers-Cotterets at the low lands of Argent. He trusted in this way to baffle the strategical plans of the Lord of Vez, who had, no doubt, posted his dogs at various likely points.

Once back in his old quarters Thibault breathed more freely. He was now on the banks of the Ourcq between Norroy and Trouennes, where the river runs at the foot of deep rocks on either side; he leaped up on to a sharp-pointed crag overhanging the water, and from this high vantage ground he sprang into the waves below, then swam to a crevice at the base of the rock from which he had leapt, which was situated rather below the ordinary level of the water, and here, at the back of this cave, he waited. He had gained at least three miles upon the dogs; and yet, scarcely another ten minutes had elapsed, when the whole pack arrived and stormed the crest of the rock. Those who were leading, mad with excitement, did not see the gulf in front of them, or else, like

their quarry they thought they would leap safely into it, for they plunged, and Thibault was splashed, far back as he was hidden, by the water that was scattered in every direction as they fell into it one by one. Less fortunate, however, and less vigorous than he was, they were unable to fight against the current, and after vainly battling with it, they were borne along out of sight before they had even got scent of the were-wolf’s retreat. Over head he could hear the tramping of the horses’ feet, the baying of the dogs that were still left, the cries of men, and above all these sounds, dominating the other voices, that of the Baron as he cursed and swore. When the last dog had fallen into the water, and been carried away like the others, he saw, thanks to a bend in the river, that the huntsmen were going down it, and persuaded that the Baron, whom he recognised at the head of his hunting-train, would only do this with the intention of coming up it again, he determined not to wait for this, and left his hiding-place. Now swimming, now leaping with agility from one rock to the other, at times wading through the water, he went up the river to the end of the Crene coppice. Certain that he had now made a considerable advance on his enemies, he resolved to get to one of the villages near and run in and out among the houses, feeling sure that they would not think of coming after him there. He thought of Preciamont; if any village was well known to him, it was that; and then, at Preciamont, he would be near Agnelette. He felt that this neighbourhood would put fresh vigour into him, and would bring him good fortune, and that the gentle image of the innocent girl would have some influence on his fate. So he started off

in that direction. It was now six o’clock in the evening; the hunt had lasted nearly fifteen hours, and wolf, dogs and huntsmen had covered fifty leagues at least. When, at last, after circling round by Manereux and Oigny, the black wolf reached the borders of the heath by the lane of Ham, the sun was already begining to sink, and shedding a dazzling light over the flowery plain; the little white and pink flowers scented the breeze that played caressingly around them; the grasshopper was singing in its little house of moss, and the lark was soaring up towards heaven, saluting the eve with its song, as twelve hours before it had saluted the morn. The peaceful beauty of nature had a strange effect on Thibault. It seemed enigmatical to him that nature could be so smiling and beautiful, while anguish such as his was devouring his soul. He saw the flowers, and heard the insects and the birds, and he compared the quiet joy of this innocent world with the horrible pangs he was enduring, and asked himself, whether after all, notwithstanding all the new promises that had been made him by the devil’s envoy, he had acted any more wisely in making this second

compact than he had in making the first. He began to doubt whether he might not find himself deceived in the one as he had been in the other.

As he went along a little footpath nearly hidden under the golden broom, he suddenly remembered that it was by this very path that he had taken Agnelette home on the first day of their acquaintance; the day, when inspired by his good angel, he had asked her to be his wife. The thought that, thanks to this new compact, he might be able to recover Agnelette’s love, revived his spirits, which had been saddened and depressed by the sight of the universal happiness around him. He heard the church bells at Preciamont ringing in the valley below; its solemn, monotonous tones recalled the thought of his fellow men to the black wolf, and of all he had to fear from them. So he ran boldly on, across the fields, to the village, where he hoped to find a refuge in some

empty building. As he was skirting the little stone wall of the village cemetery, he heard a sound of voices, approaching along the road he was in. He could not fail to meet whoever they might be who were coming towards him, if he himself went on; it was not safe to turn back, as he would have to cross some rising ground whence he might easily be seen; so there was nothing left for it but to jump over the wall of the cemetery, and with a bound he was on the other side. This graveyard as usual adjoined the church; it was uncared for, and overgrown with tall grass, while brambles and thorns grew rankly in places. The wolf made for the thickest of these bramble bushes; he found a sort of ruined vault, whence he could look out without being seen, and he crept under the branches and hid himself inside. A few yards away from him was a newly-dug grave; within the church could be heard the chanting of the priests, the more distinctly that the vault

must at one time have communicated by a passage with the crypt. Presently the chanting ceased, and the black wolf, who did not feel quite at ease in the neighbourhood of a church, and thought that the road must now be clear, decided that it was time to start off again and to find a safer retreat than the one he had fled to in his haste.

But he had scarcely got his nose outside the bramble bush when the gate of the cemetery opened, and he quickly retreated again to his hole, in great trepidation as to who might now be approaching. The first person he saw was a child dressed in a white alb and carrying a vessel of holy water; he was followed by a man in a surplice, bearing a silver cross, and after the latter came a priest, chanting the psalms for the dead.

Behind these were four peasants carrying a bier covered with a white pall over which were scattered green branches and flowers, and beneath the sheet could be seen the outline of a coffin; a few villagers from Preciamont wound up this little procession. Although there was nothing unusual in such a sight as this, seeing that he was in a cemetery, and that the newly-dug grave must have prepared him for it, Thibault, nevertheless, felt strangely moved as he looked on. Although the slightest movement might betray his presence and bring destruction upon him, he anxiously watched every detail of the ceremony.

The priest having blessed the newly-made grave, the peasants laid down their burden on an adjoining hillock. It is the custom in our country when a young girl, or young married woman, dies in the fullness of her youth and beauty, to carry her to the grave-yard in an open coffin, with only a pall over her, so that her friends may bid her a last farewell, her relations give her a last kiss. Then the coffin is nailed down, and all is over. An old woman, led by some kind hand, for she was apparently blind, went up to the coffin to give the dead one a last kiss; the peasants lifted the pall from the still face, and there lay Agnelette. A low groan escaped from Thibault’s agonised breast, and mingled with the tears and sobs of those present. Agnelette, as she lay there so pale in death, wrapped in an ineffable calm, appeared more beautiful than when in life, beneath her wreath of forget-me-nots and daisies. As Thibault looked upon the poor dead girl, his heart seemed

suddenly to melt within him. It was he, as he had truly realised, who had really killed her, and he experienced a genuine and overpowering sorrow, the more poignant since for the first time for many long months he forgot to think of himself, and thought only of the dead woman, now lost to him forever.

As he heard the blows of the hammer knocking the nails into the coffin, as he heard the earth and stones being shovelled into the grave and falling with a dull thud on to the body of the only woman he had ever loved, a feeling of giddiness came over him. The hard stones he thought must be bruising Angelette’s tender flesh, so fresh and sweet but a few days ago, and only yesterday still throbbing with life, and he made a movement as if to rush out on the assailants and snatch away the body, which dead, must surely belong to him, since, living, it had be longed to another.

But the grief of the man overcame this instinct of the wild beast at bay; a shudder passed through the body hidden beneath its wolf skin; tears fell from the fierce blood-red eyes, and the unhappy man cried out: “O God! take my life, I give it gladly, if only by my death I may give back life to her whom I have killed!”

The words were followed by such an appalling howl, that all who were in the cemetery fled, and the place was left utterly deserted. Almost at the same moment, the hounds, having recovered the scent, came leaping in over the wall, followed by the Baron, streaming with sweat as he rode his horse, which was covered with foam and blood.

The dogs made straight for the bramble bush, and began worrying something hidden there.

“Halloo! halloo!! halloo!!!” cried the Lord of Vez, in a voice of thunder, as he leapt from his horse, not caring if there was anyone or not to look after it, and drawing out his hunting-knife, he dashed

towards the vault, forcing his way through the hounds. He found them fighting over a fresh and bleeding wolf-skin, but the body had disappeared.

There was no mistake as to its being the skin of the were-wolf that they had been hunting, for with the exception of one white hair, it was entirely black.

What had become of the body? No one ever knew. Only as from this time forth Thibault was never seen again, it was generally believed that the former sabot-maker and no other was the were wolf.

Furthermore, as the skin had been found without the body, and, as, from the spot where it was found a peasant reported to have heard someone speak the words: “O God! take my life! I give it gladly, if only by my death I may give back life to her whom I have killed,” the priest declared openly that Thibault, by reason of his sacrifice and repentance, had been saved!

And what added to the consistency of belief in this tradition was, that every year on the anniversary of Agnelette’s death, up to the time when the Monasteries were all abolished at the Revolution, a monk from the Abbey of the Premonstratensians at Bourg-Fontaine, which stands half a league from Preciamont, was seen to come and pray beside her grave.

Such is the history of the black wolf, as it was told me by old Mocquet, my father’s keeper.

The End

Poetry Reading List for Architects

Architecture, as a discipline, has long claimed dominion over the notion of space. From Vitruvius’ triad of firmitas, utilitas, venustas to Le Corbusier’s declaration of the house as “a machine for living in”, architects have positioned themselves as the stewards of spatial order. Yet, for all the technical precision and aesthetic theory, architectural discourse often reduces space to geometry, structure, and function, what the eye can measure and the hand can build.

Le Corbusier once wrote, “Architecture is the learned game, correct and magnificent, of forms assembled in light.” But in this emphasis on light, form, and assembly, something slips through the cracks: the lived, felt, and imagined qualities of space. Juhani Pallasmaa, in The Eyes of the Skin, laments this very reductionism, arguing that modern architecture has become a “retinal art”, too focused on vision at the expense of the full sensory and emotional experience of space. As you know, I’ve never been a fan of the crow.

Space in architectural discourse can become rigid, formalised, a domain of grids, plans, and sections. But human experience of space is messier, more fluid, and harder to pin down. And this is where poetry begins to offer its lessons.

Poetry, unlike architecture, is unburdened by gravity, budget, or building code. It can conjure vast cathedrals in a single line or collapse entire worlds into the tight confines of a haiku. Where architects draw elevations and axonometrics, poets map the inner landscapes of memory, sensation, and longing.

Consider Rainer Maria Rilke’s evocation of space in Duino Elegies:

“Ah, but what can we take along

into that other realm? Not the art of looking,

which is learned so slowly, and nothing that happened here.

Nothing. The sufferings, then. And, above all, the heavy,

the ponderous weight of space…”

Here, space is not an external void to be measured but a burden we carry within us. The poet reminds us that space is as much an emotional and existential construct as it is a physical one.

Similarly, Emily Dickinson’s “I dwell in Possibility / A fairer House than Prose” reimagines the very boundaries of habitation. Her “house” is a metaphor for the infinite potential of the imagination, a space that expands precisely because it is unbuilt.

The Value of Cross-Disciplinary InsightsWhy, then, should architects — those who give material form to our shared environments — pay heed to poets? Because poets help us remember what architecture sometimes forgets: that space is not just seen, but felt; not just planned, but lived. The poet teaches us to be attuned to atmospheres, thresholds, silences, and the invisible contours of experience.

As architect Peter Zumthor reflects, “Architecture is not about form, it is about many other things. The light and the air. The smell and the sound. The way things feel. The memory of a space.” These are precisely the elements that poetry has always known how to capture. When architects borrow the poet’s sensitivity, they can aspire to create spaces that resonate not just in the mind’s eye but in the body’s memory.

This post proposes that five poets — each with a distinct way of understanding and shaping space through words — can help architects (and all of us) see space anew. They remind us that space is not simply a void between walls, but a condition shaped by perception, history, and desire.

Possibly my favourite project by Peter Zumthor.Poet #1: Emily Dickinson and the Architecture of Interior SpaceMicrocosms of a Room and the Mind

Possibly my favourite project by Peter Zumthor.Poet #1: Emily Dickinson and the Architecture of Interior SpaceMicrocosms of a Room and the MindEmily Dickinson, the reclusive poet of Amherst, lived much of her life within the bounds of a single house and, more precisely, within the confines of her small upstairs room. Yet in her poetry, this narrow space becomes a boundless universe, a microcosm where the architecture of the mind unfolds in endless variation.

In one of her most famous lines, Dickinson declares:

“The Brain – is wider than the Sky –”

“For – put them side by side –”

“The one the other will contain”

“With ease – and You – beside –”

Here, spatial scale collapses: the brain, enclosed within the skull, out-expands the sky itself. Dickinson’s room, like her brain, becomes a site where immensity is not measured by external dimensions, but by the reach of thought and imagination.

This stands in stark contrast to the modernist architect’s fascination with open plans and expansive vistas. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe famously championed “less is more”, but his minimalism aimed at clarity and openness. Dickinson’s minimalism, on the other hand, finds vastness in enclosure, a reminder that scale is a matter of perception as much as proportion.

Emily in a family portrait (she’s the one on the left)How Minimalism and Enclosure Create Infinite Worlds

Emily in a family portrait (she’s the one on the left)How Minimalism and Enclosure Create Infinite WorldsDickinson’s physical world was one of walls, windows, and limited horizons. Yet this very constraint fostered a deeper engagement with the textures of inner space. The smallness of her environment was not a prison but a portal:

“A Prison gets to be a friend –”

“Between its Ponderous face”

“And Ours – a Kinsmanship express –”

Here, enclosure generates intimacy, familiarity, and even affection. Dickinson teaches us that the bounded space can nurture an expansive interiority, much as a cloister or a cell might provide the contemplative with room for spiritual wandering.

Peter Zumthor echoes this sensibility when he writes in Atmospheres:

“I try to create buildings that are loved. Loved by the people who live in them, who work in them, who encounter them. This is only possible if architecture has something of the quality of silence about it.”

Dickinson’s space is precisely that: silent, intimate, inwardly resonant. Where architects sometimes seek to dissolve boundaries in the name of transparency or flow, Dickinson’s poetry reminds us of the value of shelter, of places where the self can retreat, reflect, and expand inwardly.

Managing to be intimate in a vast space, and silent in a public venue, is possibly one of Zumthor’s highest achievements in his Thermæ of Vals.Lessons for Architects on Introspection and Scale

Managing to be intimate in a vast space, and silent in a public venue, is possibly one of Zumthor’s highest achievements in his Thermæ of Vals.Lessons for Architects on Introspection and ScaleWhat can architects learn from Emily Dickinson? First, that scale is not an absolute. A small room can contain infinite possibilities if it engages the imagination and the senses.

Second, that introspection requires spaces that allow for withdrawal as much as for interaction. The rush toward openness in contemporary design risks neglecting the human need for pause, solitude, and inwardness. See any open space for reference. As Frank Lloyd Wright observed: “space is the breath of art.” But Wright’s breath often took the form of grand, sweeping volumes. Dickinson reminds us that sometimes, breath is drawn deepest in the quiet stillness of a small, enclosed space.

Architects might consider, then, how to design not only for movement and spectacle, but for stillness and thought. In Dickinson’s minimal, bounded spaces, we find a model for architecture that honours the private vastness of the mind, a space where, as she wrote, “possibility is a fairer House than Prose.”

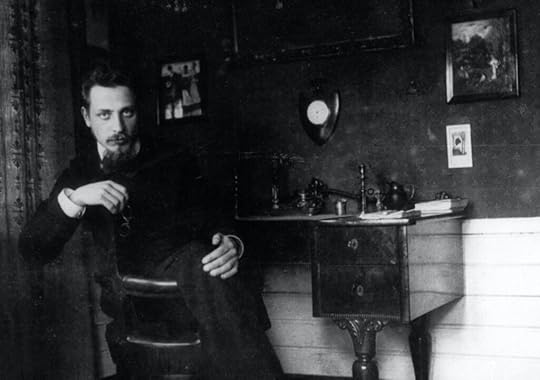

Poet #2: Rainer Maria Rilke and the Poetics of ThresholdsSpaces of Transition and Liminality

Poet #2: Rainer Maria Rilke and the Poetics of ThresholdsSpaces of Transition and LiminalityRainer Maria Rilke’s work brims with a profound sensitivity to spaces that lie between: between inside and outside, life and death, the visible and the invisible. His poetry is attuned to thresholds, those in-between zones where identity dissolves and transforms. As he writes in the Duino Elegies:

“For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror,

which we are still just able to endure,

and we are so awed because it serenely disdains

to annihilate us.”

Here, beauty itself is liminal: poised at the edge of terror, existing in a space of ambiguity. Rilke’s spatial imagination is one of doors left ajar, windows opening onto darkness, stairways that vanish into silence. His houses, cities, and rooms are not static enclosures but vessels of becoming, passage, and transformation.

This echoes the architectural reflections of Juhani Pallasmaa, who writes: “the door handle is the handshake of the building.” Pallasmaa, like Rilke, focuses on the moment of crossing, the tactile encounter at the threshold that defines our relationship with space. Rilke teaches architects to cherish these transitional moments not as mere connectors between “real” spaces, but as spaces of their own, charged with meaning.

The modular building is possibly one of Juhani Pallasmaa’s most enchanting projects.The Duino Elegies and the Metaphorical House

The modular building is possibly one of Juhani Pallasmaa’s most enchanting projects.The Duino Elegies and the Metaphorical HouseIn the Duino Elegies, Rilke invokes the metaphor of a house not as an object of shelter, but as an existential condition. The house is where the human spirit negotiates its place between the earthly and the eternal. In the First Elegy, he speaks of “the open house of the earth”, a place where angels, humans, and animals intermingle in uneasy proximity. His imagery suggests that our dwellings are never truly ours: they are shared with ghosts, memories, and the forces of nature. The house becomes a threshold in itself, a site of dialogue between permanence and flux. As he writes: “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ hierarchies?” The house, in Rilke’s hands, is less a fortress than a question—a permeable structure open to the winds of the unseen.

This resonates with the ethos of architects like Peter Zumthor and Álvaro Siza, who design not with the arrogance of control but with humility toward place. Zumthor notes:

“I have often thought that my buildings try to be a vessel for the human soul rather than monuments to the architect’s ego.”

Rilke’s poetic houses, likewise, are vessels for the soul’s uncertainties.

One of Alvaro Siza’s monuments to his poetic approach is the Tea House in Porto.What Architects can learn about Ambiguity and Becoming

One of Alvaro Siza’s monuments to his poetic approach is the Tea House in Porto.What Architects can learn about Ambiguity and BecomingRilke’s gift to architecture lies in his reverence for ambiguity: the refusal to define, the embrace of what is in process. In a world where architectural practice often privileges clarity, function, and resolution, Rilke asks us to consider the virtues of the unresolved, the liminal, the space of becoming.

Thresholds, in Rilke’s poetics, are not obstacles to cross but experiences to inhabit. They invite us to dwell in uncertainty, to attune ourselves to the subtleties of change. As Louis Kahn famously said: “A room is not a room without natural light.” But Rilke might counter that a room is not a room without shadow, without mystery, without the sense of what lies beyond.

For architects, Rilke’s work suggests designing spaces that honour these moments: foyers that slow our passage, staircases that invite pause, windows that frame the ungraspable. To design with Rilke’s sensitivity is to create buildings that do not merely shelter bodies but accompany souls in their ceaseless transition.

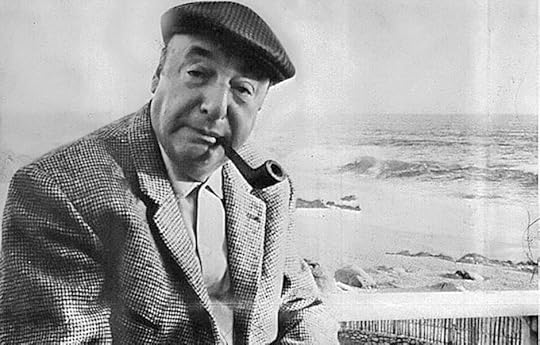

Poet #3: Pablo Neruda – The Tactile and the ElementalOdes to Everyday Objects and Spaces

Poet #3: Pablo Neruda – The Tactile and the ElementalOdes to Everyday Objects and SpacesPablo Neruda’s Odas elementales are celebrations of the ordinary. In these poems, he sings the praises of spoons, onions, chairs, socks, and the most unremarkable of rooms. Far from trivial, these odes elevate the material world to the realm of the sacred. Neruda writes:

“I love things with a fervour

that I can’t explain:

the metal compass and the carpenter’s plane,

the carpenter’s saw,

the smell of wood,

and the smell that unfolds

from the firewood.”

Here, the poet’s gaze lingers not on monumental spaces or heroic structures, but on the humblest artefacts that shape daily life. Neruda understands that space is not made grand by scale, but by its relationship to the objects and gestures that inhabit it.

This attention to the everyday echoes the wisdom of architects like Peter Zumthor, who writes: “Materials have the capacity to awaken the emotions in us. A certain material, or the sound of it, or the way light falls on it, can transport us to another place in our memory.” Neruda’s odes remind us that architecture begins not with abstractions, but with the intimate dialogue between hand, tool, and matter.

Architecture as Intimacy with MaterialityNeruda’s poetry invites architects to rediscover materiality not as a means to an end, but as an end in itself. His words caress surfaces, textures, smells. He praises the density of wood, the weight of stone, the grain of bread. For Neruda, to know the world is to touch it, to breathe it in, to taste its presence.

His Ode to the Table exalts this sensorial bond:

“The world is a table… engulfed in honey and smoke smothered by apples and blood. The table is already set, and we know the truth as soon as we are called…”

In the same way, architecture that is truly human must honour the table, the threshold, the window sill, the small-scale elements that root us in place. This perspective counters the tendency in contemporary design toward sleekness and dematerialisation, where glass facades and synthetic skins often mask the tactile reality of structure. Neruda’s elemental poetics call to mind the ethos of Alvar Aalto, who observed: “Form must have a content, and that content must be linked with nature and the human soul.” Neruda’s harmonies of wood, stone, bread, and cloth challenge architects to rediscover the sensual unity of material and life.

Designing with the Senses, not Just the EyeModern architecture, with its privileging of vision, has too often neglected the full range of human sensation. Neruda’s poetry compels us to design for touch, smell, taste, and sound, to create spaces that embrace the body, not just impress the eye. His Ode to the Onion reminds us that even a simple aroma can evoke entire worlds: “You make us cry without hurting us.”

In the same spirit, Juhani Pallasmaa, in The Eyes of the Skin, urges architects to reject ocularcentrism and engage all the senses: “Every touching experience in architecture is multi-sensory; qualities of matter, space, and scale are measured equally by the eye, ear, nose, skin, tongue, skeleton, and muscle.”

Neruda, through his poetry, teaches architects to approach space as an orchestra of sensations where the roughness of a wall, the creak of a stair, or the coolness of a stone floor become as vital as the play of light or the sweep of form. Designing with Neruda’s spirit means shaping spaces where materiality is not hidden, but celebrated; where the sensual encounter with the world is at the heart of the architectural experience.

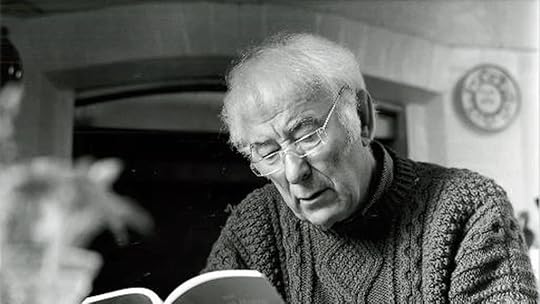

Pablo NerudaPoet #4: Seamus Heaney, excavating Memory in the LandscapeThe Layered Spatiality of History and Soil

Pablo NerudaPoet #4: Seamus Heaney, excavating Memory in the LandscapeThe Layered Spatiality of History and SoilSeamus Heaney’s poetry draws deeply from the soil, not just as physical matter, but as a medium of history, memory, and identity. His verses are filled with bogs, fields, and furrows, where each layer of earth conceals the traces of those who have gone before. In Digging, Heaney writes:

“Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.”

The poet’s act of writing mirrors the act of excavation. Both the farmer’s spade and the archaeologist’s trowel unearth hidden narratives, buried truths, and forgotten lives. In Heaney’s hands, the landscape is no blank canvas: it is a stratified archive, rich with stories waiting to be revealed.

Architects, too, work upon the land, but too often they erase rather than reveal its histories in the name of progress or supposed poetics. Heaney’s sensitivity to the earth challenges designers to see the site as a text to be read, not a page to be cleared. His bog poems, in particular, invite us to contemplate land as both witness and participant in human drama, a place where time is inscribed in layers of peat and mud.

Space as Palimpsest: the Invisible in the VisibleHeaney’s landscapes are palimpsests, surfaces inscribed, erased, and inscribed again, where new meanings emerge only through attentive excavation. In Bogland, he writes:

“Our pioneers keep striking

Inwards and downwards,

Every layer they strip

Seems camped on before.”

Here, space is not simply a backdrop for human action; it is an active agent in the formation of memory. The visible landscape conceals invisible histories — of violence, of toil, of ritual — that shape our sense of belonging.

This idea finds resonance in architectural thought. Kenneth Frampton, in his call for critical regionalism, warns against placelessness and urges designers to root their work in the cultural and topographic specificity of the site. Heaney’s poetry gives voice to this ethos, reminding us that every site is haunted by its own past, and that good design listens for these echoes rather than silencing them.

The architectural theorist and practitioner Peter Zumthor echoes this respect for the invisible in the visible: “The site is not simply a place where I build; it is part of what I build. The building does not stand on the ground, it emerges from the ground.” Heaney’s bogs and fields offer architects a model for how to engage with landscape as a living archive.

Kenneth FramptonTopography and the Ethics of Place-Making

Kenneth FramptonTopography and the Ethics of Place-MakingAt the heart of Heaney’s spatial poetics is an ethics of place-making. His work asks us to honour the integrity of the land, to recognise its layered meanings, and to design in dialogue with its memory. In The Tollund Man, he writes of the bog body:

“I will feel lost,

Unhappy and at home.”

This tension — between belonging and estrangement, between the known and the unknowable — defines his relationship with place. Heaney teaches us that to make a place ethically is to acknowledge these tensions, to design not for mastery over the land but for companionship with it. For architects, this means resisting the urge to overwrite the land with generic forms, and instead engaging in what Heaney might call a conversation with topography. It means allowing the shape of a hill, the course of a stream, or the memory of a field boundary to inform the shape and orientation of a building. It means seeing a place not as property, but as a partner. In the words of Glenn Murcutt: “We do not impose on the landscape; we work with it.”

Heaney’s vision of space as layered, storied, and morally charged offers a powerful counterpoint to the flattening tendencies of globalised design. His poetry asks architects to dig deeper, to see more, and to build with humility before the deep time of the land.

Poet #5: Matsuo Bashō and the Ephemeral JourneySpace as a Sequence of Moments

Poet #5: Matsuo Bashō and the Ephemeral JourneySpace as a Sequence of MomentsMatsuo Bashō, master of the haiku and of the poetic journey, invites us to experience space not as a static entity but as a sequence of moments, each fleeting, each charged with transience. His travel journals, like Oku no Hosomichi (something along the lines of The Narrow Road to the Deep North), trace paths through landscapes where space is continually revealed and redefined by the traveller’s passage.

For Bashō, space is not a fixed composition but an unfolding of encounters: the sudden opening of a view through mist, the shifting of light on water, the momentary alignment of stone, tree, and sky. This conception of space resonates with the idea of architecture not as object, but as experience, an architecture that emerges, as Bashō’s poems do, through time and movement.

Architects like Kengo Kuma echo this sensibility. Kuma writes: “We pursue an architecture that vanishes. An architecture that melts into the landscape.” Like Bashō’s path, Kuma’s architecture seeks not permanence, but presence, attuned to the rhythms of nature and the temporality of human life.

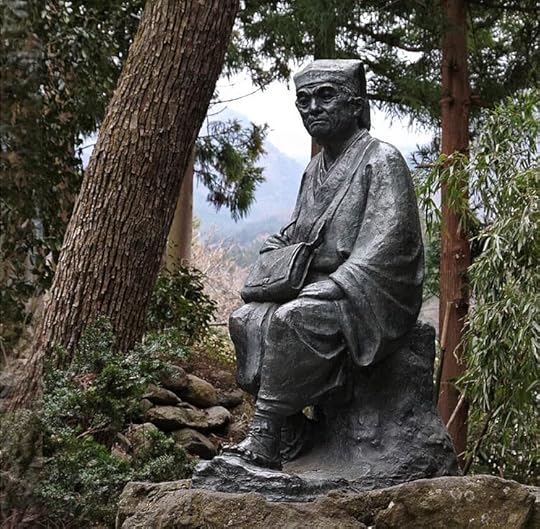

A statue to the poetThe Haiku as a Spatial Composition

A statue to the poetThe Haiku as a Spatial CompositionBashō’s haiku are themselves micro-architectures of space and time. With the utmost economy, they conjure entire worlds within seventeen syllables. Consider his famous haiku:

“An old pond,

*a frog jumps in,

the sound of water.”

Here, space unfolds through a sequence: the stillness of the pond, the leap of the frog, the ripple and sound that mark the moment’s passing. The haiku is not a snapshot but a choreography, a spatial composition that depends on what precedes and what follows, on silence and sound, on absence and presence.

This minimalist spatial poetics offers profound lessons for design. In architecture, as in haiku, what is left unsaid — the pause, the void, the interval — is as significant as what is articulated. And as much as this might escape us when translated in our Western languages, Tadao Ando captures this in his reflection: “I don’t believe architecture has to speak too much. It should remain silent and let nature in the guise of sunlight and wind speak.” Like the haiku, architecture can frame and heighten awareness of the transient, the subtle, the barely-there.

Tadao Ando’s architecture in NaoshimaTemporal Architecture: Learning from Impermanence

Tadao Ando’s architecture in NaoshimaTemporal Architecture: Learning from ImpermanenceBashō’s vision of space is inseparable from his deep embrace of impermanence, or mujō. His poetry celebrates the passing of the seasons, the weathering of buildings, the falling of blossoms. This attitude challenges the Western architectural obsession with durability and monumentality. Bashō’s lesson is that beauty and meaning arise precisely because things change and fade. In Oku no Hosomichi, Bashō reflects on the decayed ruins of past grandeur:

“The summer grasses—

All that remains

Of warriors’ dreams.”

The remains of castles and temples are not failures of permanence, but reminders of the natural cycles to which all human works belong. For architects, this suggests a practice that designs with time in mind, not to defy it, but to move with it. The patina of materials, the growth of moss, the erosion of stone: these are not defects, but part of architecture’s dialogue with the world. This idea resonates with the philosophy of wabi-sabi and with contemporary designers like Peter Zumthor, who is scarcely Japanese and still he writes:

“Buildings that have the qualities of age and time… they touch us because they bear witness to the life that has been lived within them.”

Bashō’s haiku, with their distilled temporality, remind architects to create spaces that are not frozen in time, but that invite and embody the passage of time. To build in Bashō’s spirit is to accept that architecture, like the journey, is always incomplete, always becoming.

Common ThreadsAcross cultures, eras, and languages, the poets we have explored — Emily Dickinson, Rainer Maria Rilke, Pablo Neruda, Seamus Heaney, and Matsuo Bashō — offer a vision of space that challenges, enriches, and ultimately transcends conventional architectural thinking. Though their voices differ, they share key insights that architects might find stimulating to heed.

Space as Lived Experience, Not Abstract FormEach of these poets teaches us that space is not a neutral container, a stage upon which life merely happens. Instead, space is something felt, inhabited, and made meaningful through memory, perception, and use. Dickinson’s small room expands through imagination; Rilke’s thresholds invite transformation; Neruda’s table becomes the altar of daily ritual; Heaney’s bog preserves the deep time of human histories; Bashō’s path reveals space as momentary and ever-changing.

This stands in stark contrast to an architectural tradition that has often privileged visual composition, geometric rigour, or iconic form. As Louis Kahn put it: “Architecture is the making of the world as it should be, not as it is.” But the poets remind us that architecture is not merely the art of creating what nature cannot, but the art of creating spaces in dialogue with nature, time, and the human condition.

The Value of Ambiguity, Silence, and the UnseenPoetic space is rarely totalizing or complete. It leaves room for the unknown, the incomplete, the ambiguous. Rilke’s houses are porous to angels and shadows; Heaney’s landscapes hold histories we can never fully uncover; Bashō’s spaces exist only in the instant of perception.

Architects can learn here the value of designing not only for clarity but for mystery. Peter Zumthor’s call for buildings that have “a beautiful silence about them” echoes the poet’s wisdom: space should not always shout; sometimes it should listen.

Materiality and Sensory RichnessWhere much contemporary architecture risks becoming dematerialised — relying on glass, steel, and abstract surfaces — the poets draw us back to the world of touch, scent, and sound. Neruda’s odes are hymns to grain, weight, and texture. Heaney’s soil and Bashō’s rain wet the hands and the feet. Dickinson’s room is felt in the hush of solitude.

This is an invitation for architects to engage all the senses in their design: to think about how a floor feels beneath bare feet, how a door handle greets the palm, how a space smells after rain.

Time as a Dimension of DesignFinally, these poets show us that space cannot be separated from time. Buildings are not fixed objects: they weather, they age, they are lived in and changed. Bashō’s haiku is architecture in miniature: a structure built to house a moment. Heaney’s bog is architecture in the deep time of geology and history. Dickinson’s room is a vessel for memory. In embracing impermanence, architects can move beyond the illusion of permanence toward designs that gracefully accommodate growth, decay, and renewal.

August 5, 2025

A Jury of Her Peers

A Jury of Her Peers by Susan Glaspell

At first glance, A Jury of Her Peers by Susan Glaspell might appear to be a little novel tucked away in the archives of early 20th-century American literature. However, beneath its seemingly simple narrative lies a profound exploration of gender dynamics, justice, and the often-overlooked emotional landscapes that govern human relationships. Written over a century ago, its themes resonate as sharply today as they did in the era of its publication.

Susan Glaspell (1876–1948) was an American playwright, novelist, journalist, and actress. Though perhaps lesser-known in mainstream literary circles, she is a towering figure in early feminist literature and American theatre. Co-founder of the Provincetown Players, an influential theatre group that nurtured talents like Eugene O’Neill, Glaspell was a groundbreaking voice advocating for women’s perspectives and experiences long before feminist discourse entered the academic mainstream.

Glaspell’s works often delve into the intricate interplay between societal norms and individual conscience, particularly focusing on women’s struggles in a patriarchal world. A Jury of Her Peers, published in 1917, is a perfect embodiment of her narrative style—quietly subversive, deeply empathetic, and poignantly observant.

The book is an adaptation of Glaspell’s earlier one-act play Trifles, which itself was inspired by a real murder trial she covered as a young reporter. The plot revolves around two women accompanying their husbands — a county official and a testimony – on a visit to the home of Minnie Wright, a woman accused of murdering her husband.

While the men conduct their investigation with officious arrogance, dismissing the domestic sphere as trivial, the two women begin to “sift through clues” found among the ordinary objects of Minnie’s household. They piece together the quiet desperation of Minnie’s life: the isolation, emotional abuse, and gradual erasure of her identity.

Through their subtle yet incisive observations, they uncover the chilling truth that eludes the men. The climax doesn’t hinge on a dramatic revelation but rather a quiet, inevitable conclusion: the women’s verdict, delivered in the form of shared understanding, becomes a more profound form of justice than the legal proceedings themselves.

In an era where conversations about gender bias, domestic violence, and systemic injustice are ever more pressing, A Jury of Her Peers serves as a timeless reminder of how societal structures can silence women’s experiences. Yet, it also showcases the quiet power of empathy, observation, and solidarity in challenging these structures.

Glaspell doesn’t deliver a tale of courtroom drama or sensational revelations. Instead, she offers a nuanced, quietly unsettling narrative where justice emerges from the overlooked, the domestic, and the “trifling” details of women’s lives.

August 4, 2025

L’Océan de Léa

I’m on vacation in Southern France, and yesterday we wandered into L’Océan de Léa, an immersive world crafted entirely from paper at the Centre des Congrès OcéaNice in Nice. The installation is a vast, dreamy seascape sculpted by the master origami-artist Junior Fritz Jacquet, and it’s definitely worthy of a visit.

Born in Haiti and now based in Paris, Jacquet has spent over 20 years transforming paper into sweeping sculptural landscapes. Often celebrated as a master of origami, he’s recognized by the Nippon Origami Association for evolving the art beyond crisp folds to embrace folded, crumpled, textured expression. His works have traversed the globe, from the Grand Palais to diplomatic venues.

What struck me most is Jacquet’s commitment to using reclaimed, industrial paper — discarded sheets collected from a closing factory — to compose monumental underwater formations. In doing so, he offers a sharp statement: art may arise from waste, resistance can be folded into beauty, and redemption can take shape in the ruin of our overconsumption.

This mode of papercraft as resistance insists we rethink materials: even what’s destined to be thrown away can become an instrument of wonder and environmental advocacy. The entire installation used perhaps ten tonnes of such salvaged paper, turned into creatures, reefs, and caverns in an ambitious four-month collaborative residency.

Stepping into the exhibition is like diving into a slow-motion dream. Hanging jellyfish drift overhead; manta-ray silhouettes glide through light; coral-like posidonia waves undulate along shimmering caves and grottos, all shaped from the same humble medium and in three shades of colour. The play of light — cool blues, warm ambers, soft whites — animates every fold. The delicacy of the material contrasts with the scale: small fragile forms composing an oceanic cathedral. It felt both soothing and stirring. Spanning 2,000 m², the installation invites quiet wandering and free-form imagination, never strict visual realism.

By engaging visitors not with charts or guilt‑laden messages, but with empathy and imaginative immersion, the exhibition gently stirs awareness of the ocean’s beauty and the urgency to preserve it. Jacquet’s ocean is silent, still, paper‑quiet, but its fragility echoes the vulnerability of marine environments. It reminds us that coral, fish, seaweed, and waves are delicate, and that emotional connection may be the most powerful invitation to conservation.

In our era of mass plastic pollution and ocean warming, L’Océan de Léa serves as both tribute and warning. It exemplifies how art can channel ecological consciousness while remaining accessible and enchantingly beautiful. Preserving the ocean isn’t just about policy but also about feeling. When we sit with paper‑sculpted reefs, or imagine manta rays gliding through light, our hearts align with what needs protecting. The exhibition asks us to translate that emotional bond into action.

If you’re in Nice before 14 September 2025, don’t miss this tender, visionary installation.

July 30, 2025

Werewolves Wednesday: The Wolf-Leader (23)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter XXIII: The AnniversaryAs soon as Thibault ceased to hear the furious cries of his pursuers Behind him, he slackened his pace, and the usual silence again reigning through out the forest, he paused and sat down on a heap of stones. He was in such a troubled state of mind that he did not recognise where he was, until he began to notice that some of the stones were blackened, as if they had been licked by flames; they were the stones of his own former hearth.

Chance had led him to the spot where a few months previously his hut had stood.

The shoemaker evidently felt the bitterness of the comparison between that peaceful past and this terrible present, for large tears rolled down his cheeks and fell upon the cinders at his feet. He heard midnight strike from the Oigny church clock, then one after the other from the other neighbouring village towers. At this moment the priest was listening to Agnelette’s dying prayers.

“Cursed be the day!” cried Thibault, “when I first wished for anything beyond what God chooses to put within the reach of a poor workman! Cursed be the day when the black wolf gave me the power to do evil, for the ill that I have done, instead of adding to my happiness, has destroyed it forever!”

A loud laugh was heard behind Thibault’s back.

He turned; there was the black wolf himself, creeping noiselessly along, like a dog coming to rejoin its master. The wolf would have been invisible in the gloom but for the flames shot forth from his eyes, which illuminated the darkness; he went round the hearth and sat down facing the shoemaker.

“What is this!” he said. “Master Thibault not satisfied? It seems that Master Thibault is difficult to please.”

“How can I feel satisfied,” said Thibault. “I, who since I first met you, have known nothing but vain aspirations and endless regrets? I wished for riches, and here I am in despair at having lost the humble roof of bracken under shelter of which I could sleep in peace without anxiety as to the morrow, without troubling myself about the rain or the wind beating against the branches of the giant oaks.

“I wished for position, and here I am, stoned and hunted down by the lowest peasants, whom formerly I despised. I asked for love, and the only woman, who loved me and whom I loved became the wife of another, and she is at this moment cursing me as she lies dying, while I, notwithstanding all the power you have given me, can do nothing to help her!”

“Leave off loving anybody but yourself, Thibault.”

“Oh! yes, laugh at me, do!”

“I am not laughing at you. But did you not cast envious eyes on other people’s property before you had set eyes on me?”

“Yes, for a wretched buck, of which there are hundreds just as good browsing in the forest!”

“You thought your wishes were going to stop at the buck, Thibault; but wishes lead on to one another, as the night to the day, and the day to night. When you wished for the buck, you also wished for the silver dish on which it would be served; the silver dish led you on to wish for the servant who carries it and for the carver who cuts up its contents. Ambition is like the vault of heaven; it appears to be bounded by the horizon, but it covers the whole earth. You disdained Agnelette’s innocence, and went after Madame Poulet’s mill; if you had gained the mill, you would immediately have wanted the house of the Bailiff Magloire; and his house would have had no further attraction for you when once you had seen the Castle of Mont-Gobert.

You are one in your envious disposition with the fallen Angel, your master and mine; only, as you were not clever enough to reap the benefit that might have accrued to you from your power of inflicting evil, it would perhaps have been more to your interest to continue to lead an honest life.”

“Yes, indeed,” replied the shoemaker, “I feel the truth of the proverb, ‘Evil to him who evil wishes’ “But”, he continued, “can I not become an honest man again?”

The wolf gave a mocking chuckle. “My good fellow, the devil can drag a man to hell,” he said, “by a single hair. Have you ever counted how many of yours now belong to him?”

“No.”

“I cannot tell you that exactly either, but I know how many you have which are still your own. You have one left! You see it is long past the time for repentance.”

“But if a man is lost when but one of his hairs belongs to the devil,” said Thibault, “why cannot God likewise save a man in virtue of a single hair?”

“Well, try if that is so!”

“And, besides, when I concluded that unhappy bargain with you, I did not understand that it was to be a compact of this kind.”

“Oh, yes! I know all about the bad faith of you men! Was it no compact then to consent to give me your hairs, you stupid fool? Since men invented baptism, we do not know how to get hold of them, and so, in return for any concessions we make them, we are bound to insist on their relinquishing to us some part of their body on which we can lay hands. You gave us the hairs of your head; they are firmly rooted, as you have proved yourself and will not come away our grasp… No, no, Thibault, you have belonged to us ever since, standing on the threshold of the door that was once there, you cherished within you thoughts of deceit and violence.”

“And so,” cried Thibault passionately, rising and stamping his foot, “and so I am lost as regards the next world without having enjoyed the pleasures of this!”

“You can yet enjoy these.”

“And how, I pray.”

“By boldly following the path that you have struck by chance, and resolutely determining on a course of conduct which you have adopted as yet only in a half hearted way; in short, by frankly owning yourself to be one of us.”

“And how am I to do this?”

“Take my place.”

“And what then?”

“You will then acquire my power, and you will have nothing left to wish for.”

“If your power is so great, if it can give you all the riches that I long for, why do you give it up?”

“Do not trouble yourself about me. The master for whom I shall have won a retainer will liberally reward me.”

“And if I take your place, shall I also have to take your form?”

“Yes, in the night-time; by day you will be a man again.”

“The nights are long, dark, full of snares; I may be brought down by a bullet from a keeper, or be caught in a trap, and then good-bye riches, good-bye position and pleasure.”

“Not so; for this skin that covers me is impenetrable by iron, lead or steel. As long as it protects your body, you will be not only invulnerable, but immortal; once a year, like all were-wolves, you will become a wolf again for four and twenty hours, and during that interval, you will be in danger of death like any other animal. I had just reached that dangerous time a year ago to-day, when we first met.”

“Ah!” said Thibault, “that explains why you feared my Lord Baron’s dogs.”

“When we have dealings with men, we are forbidden to speak anything but the truth, and the whole truth; it is for them to accept or refuse.”

“You have boasted to me of the power that I should acquire; tell me, now, in what that power will consist?”

“It will be such that even the most powerful king will not be able to withstand it, since his power is limited by the human and the possible.”

“Shall I be rich?”

“So rich, that you will come in time to despise riches, since, by the mere force of your will, you will obtain not only what men can only acquire with gold and silver, but also all that superior beings get by their conjurations.”

“Shall I be able to revenge myself on my enemies?”

“You will have unlimited power over everything which is connected with

evil.”

“If I love a woman, will there again be a possibility of my losing her?”

“As you will have dominion over all your fellow creatures, you will be able to do with them what you like.”

“There will be no power to enable them to escape from the trammels of my will?”

“Nothing, except death, which is stronger than all.”

“And I shall only run the risk of death myself on one day out of the three hundred and sixty-five?”

“On one day only; during the remaining days nothing can harm you, neither iron, lead, nor steel, neither water, nor fire.”

“And there is no deceit, no trap to catch me, in your words?”

“None, on my honour as a wolf!”

“Good,” said Thibault, “then let it be so; a wolf for four and twenty hours, for the rest of the time the monarch of creation! What am I to do? I am ready.”

“Pick a holly-leaf, tear it in three pieces with your teeth, and throw it away from you, as far as you can.”

Thibault did as he was commanded.

Having torn the leaf in three pieces, he scattered them on the air, and although the night till then had been a peaceful one, there was immediately heard a loud peal of thunder, while a tempestuous whirlwind arose, which caught up the fragments and carried them whirling away with it.

“And now, brother Thibault,” said the wolf, “take my place, and good luck be with you! As was my case just a year ago, so you will have to become a wolf for four and twenty hours; you must endeavour to come out of the ordeal as happily as I did, thanks to you, and then you will see realised all that I have promised you. Meanwhile, I will pray the lord of the cloven hoof that he will protect you from the teeth of the Baron’s hounds, for, by the devil himself, I take a genuine interest in you, friend Thibault.”

And then it seemed to Thibault that he saw the black wolf grow larger and taller, that it stood up on its hind legs and finally walked away in the form of a man, who made a sign to him with his hand as he disappeared.

We say it seemed to him, for Thibault’s ideas, for a second or two, became very indistinct. A feeling of torpor passed over him, paralysing his power of thought. When he came to himself, he was alone. His limbs were imprisoned in a new and unusual form; he had, in short, become in every respect the counterpart of the black wolf that a few minutes before had been speaking to him. One single white hair on his head alone shone in contrast to the remainder of the sombre coloured fur; this one white hair of the wolf was the one black hair which had remained to the man.

Thibault had scarcely had time to recover himself when he fancied he heard a rustling among the bushes, and the sound of a low, muffled bark… He thought of the Baron and his hounds, and trembled. Thus metamorphosed into the black wolf, he decided that he would not do what his predecessor had done, and wait till the dogs were upon him. It was probably a bloodhound he had heard, and he would get away before the hounds were uncoupled. He made off, striking straight ahead, as is the manner of wolves, and it was a profound satisfaction to him to find that in his new form he had tenfold his former strength and elasticity of limb.

“By the devil and his horns!” the voice of the Lord of Vez was now heard to say to his new huntsman a few paces off, “you hold the leash too slack, my lad; you have let the bloodhound give tongue, and we shall never head the wolf back now.”

“I was in fault, I do not deny it, my Lord; but as I saw it go by last evening only a few yards from this spot, I never guessed that it would take up its quarters for the night in this part of the wood and that it was so close to us as all that.”

“Are you sure it is the same one that has got away from us so often?”

“May the bread I eat in your service choke me, my lord, if it is not the same black wolf that we were chasing last year when poor Marcotte was drowned.”

“I should like finely to put the dogs on its track,” said the Baron, with a sigh.

“My lord has but to give the order, and we will do so, but he will allow me to observe that we have still two good hours of darkness before us, time enough for every horse we have to break its legs.”

“That may be, but if we wait for the day, l’Eveille, the fellow will have had time to get ten leagues away.”

“Ten leagues at least,” said l’Eveille, shaking his head.

“I have got this cursed black wolf on my brain,” added the Baron, “and I have such a longing to have its skin, that I feel sure I shall catch an illness if I do not get hold of it.”

“Well then, my lord, let us have the dogs out without a moment’s loss of time.”

“You are right, l’Eveille; go and fetch the hounds.”

L’Eveille went back to his horse, that he had tied to a tree outside the wood, and went off at a gallop, and in ten minutes’ time, which seemed like ten centuries to the Baron, he was back with the whole hunting train. The hounds were immediately uncoupled.

“Gently, gently, my lads!” said the Lord of Vez, “you forget you are not handling your old well-trained dogs; if you get excited with these raw recruits, they’ll merely kick up a devil of a row, and be no more good than so many turnspits; let ’em get warmed up by degrees.”

And, indeed, the dogs were no sooner loose, than two or three got at once on to the scent of the were-wolf, and began to give cry, whereupon the others joined them. The whole pack started off on Thibault’s track, at first quietly following up the scent, and only giving cry at long intervals, then more excitedly and of more accord, until they had so thoroughly imbibed the odour of the wolf ahead of them, and the scent had become so strong, that they tore along, baying furiously, and with unparalleled eagerness in the direction of the Yvors coppice.

“Well begun, is half done!” cried the Baron. “You look after the relays, l’Eveille; I want them ready whenever needed! I will encourage the dogs… And you be on the alert, you others,” he added, addressing himself to the younger keepers, “we have more than one defeat to avenge, and if I lose this view halloo through the fault of anyone among you, by the devil and his horns! he shall be the dogs’ quarry in place of the wolf!”

After pronouncing these words of encouragement, the Baron put his horse to the gallop, and although it was still pitch dark and the ground was rough, he kept the animal going at top speed so as to come up with the hounds, which could be heard giving tongue in the low lands about Bourg-Fontaine.

…to be continued.

When the Model breaks: what accidents reveal about Design

There’s a peculiar silence that follows a model crash. A moment of suspended disbelief, cursor frozen mid-command, screen blinking in quiet rebellion, the machine silently buzzing and… well, not responding. In the world of digital design — especially in the complex ecosystem of tools you need to work in BIM — failure is not just disruptive: it’s disorienting. The model, after all, is supposed to obey every rule we set and every constraint we define.

And yet, it breaks.

When it does, it’s tempting to treat these episodes as mere technical hiccups. A corrupted family in Revit? Those things happen. A misfired node in Dynamo? Everyone can be distracted once in a while. A misaligned geometry in Navisworks? No standard can survive in the field. They’re all bugs to fix, glitches to patch, and every BIM coordinator knows how to move a geometry in Navisworks, don’t they? But what if these breakdowns are not exceptions to the system but revelations from it? And I don’t mean it in the biblical sense, as they’re often treated. Failure isn’t just in the software, but in the way we think through it.

1. The Beauty of the BreakdownWe often approach digital tools with a sense of mastery, armed with templates, scripts, and clean logic. But the more fluent we become, the more invisible our assumptions grow. We begin to see the interface as neutral, the logic as infallible, the model as truth. Until something goes wrong. And in that moment — when the system refuses to comply, when the geometry folds in on itself, when a routine loops into infinity — we’re granted a rare glimpse behind the curtain.

Failure exposes the scaffolding of our thinking. It forces us to confront the cognitive shortcuts we’ve taken, the blind spots in our workflows, the metaphors we’ve projected onto machines. It reminds us that design, even at its most digital, is an interpretive act full of ambiguity, contingency, and contradiction.

This week’s article follows up on a series on the usefulness of failure, and it’s about those moments. Not the polished outputs or the best practices, but the stumbles, the wrong turns, the crashes, the contour of accidents using them not as cautionary tales, but as field notes from the edges of certainty. Because sometimes, when the model breaks, it’s trying to tell us something we’ve forgotten how to hear.

2. Moments of Rupture: Revit, Dynamo, and Navisworks in FreefallSome failures arrive like avalanches: no warning, just the sudden weight of a system that collapses. Others creep in quietly, unnoticed, until a single trigger sets off a chain reaction. In digital design, we build with logic, geometry, and metadata, but the things that break our models are rarely as neat.

This is a story in three acts. Each one begins with intention. Each one ends with collapse.

2.1. The Revit Handle That Killed a SkyscraperIt started innocently, as these things often do: a detail-oriented designer trying to count door handles not by the door because you never know. In a skyscraper. So they did what any skilled modeller might be tempted to: created a shared handle family, nested it into the door, and loaded it into the model. On the other side of the office, another similarly detail-oriented designer did the same thing. With the same handle. Two handles. Same name. Different geometry. Both shared. Both loaded into the model. At the same time.

And that’s how the giant fell.

It wasn’t a dramatic crash at first. Just slow, grinding lag. Then unexpected errors when syncing. Weird shit going down. Eventually, the model refused to open. A building, thousands of elements strong, felled by two tiny handles vying for attention at the naming level. They were nested inside every door in a 35-story structure, duplicating themselves recursively, confusing the project browser and corrupting the central file.

David didn’t kill Goliath with a sling. He did it with a door handle.

This wasn’t just an oversight: it was a symptom of faith. Faith in parametric order, in the clean elegance of shared families, in the idea that a model, once smart, will remain stable. But even intelligence becomes fragile when the logic folds in on itself. And sometimes a complex tool isn’t the right one to solve a simple thing.

2.2. Dynamo’s Material Identity Crisis

2.2. Dynamo’s Material Identity CrisisThis one was mine.

I wrote the script in the middle of office hours, surrounded by people who were whining because they didn’t like Revit and by people who were convinced the BIM coordinator should model their families for them, and yet I was pleased with the simplicity of my approach. A Dynamo routine to rename all materials based on a parameter expressing their ID codes. Elegant, efficient, recursive. I watched it loop through the dataset, line by line, renaming with robotic precision. Except I hadn’t accounted for one thing: univocity. The fucking IDs weren’t unique.

The script dutifully applied the same name to multiple materials. The model hiccupped. Then stuttered. Then died. When I tried re-opening it, it was corrupted beyond recovery. A beautiful logic executed without critical pause.

Dynamo doesn’t give you red flags when logic becomes dangerous. It does what it’s told, even if what it’s told is quietly destructive. The illusion of control is thick in visual programming; every node looks like certainty, but when your assumptions about structure falter, the whole design becomes a house of cards.

These cards. And they’re angry.2.3. The Clash That Wasn’t (But Should Have Been)

These cards. And they’re angry.2.3. The Clash That Wasn’t (But Should Have Been)Navisworks promised clarity. A simple Hard clash test between MEP and Structure: boxes checked, geometries loaded, intersections flagged. We presented the report with confidence: no major clashes between the pipes and the walls. The team breathed easily. Weeks later, someone noticed something on a section of the model. Two pipes, parallel, lost inside a pillar. Completely swallowed. Not flagged in the clash test. Not visible in any report. Not caught in coordination. We had chosen the standard Hard clash with Normal Intersection. Which, as it turns out, only detects intersections between triangles. And Navisworks, under the hood, sees everything as triangles: if the triangles don’t intersect — even if the pipes clearly shouldn’t be there — the test says everything’s fine, and the hungry pillar almost got away with swallowing a whole portion of a system.

We hadn’t known. Or maybe we did know but didn’t connect the brain to the hand when we set up the test. Or maybe I had always used Hard (Conservative) tests — that reports potential collisions even if they might be false positives — and didn’t remember to stay… well, conservative.

In the pursuit of precision, false clarity won over noisy truth.

As a Chinese would say, we had eyes to see but couldn’t recognise Mount Tai

As a Chinese would say, we had eyes to see but couldn’t recognise Mount TaiEach of these moments should have left a crater in its wake, not in the model but in the way we approached our tools. Revit didn’t collapse because of geometry; it collapsed because of a paranoid overzeal. Dynamo executed perfectly, but on flawed assumptions. Navisworks told us what we asked, not what we needed to know.

As we have seen, breakdowns aren’t rare anomalies but they’re the system talking back and revealing, often too late, the gap between our logic and our understanding. So what do we do with them?

3. Layer by Layer: Unpacking the AccidentFailure makes for a compelling story. But once the panic subsides and the laughter — however bitter — fades, something more useful remains and it’s not people screaming in the office for you to get fired (although that has been know to happen, in certain particularly pleasant environments): what remains should be insight. Not into the tools themselves, which are usually easy enough to debug, but into the hidden frameworks we carry into our use of them. Our mental models. Our defaults and defects. The scaffolding of trust we place in digital logic.

Let’s peel back the layers of each collapse, not to blame the software or even the workflow, but to understand the thinking that made the accident possible.

3.1. Revit: The Illusion of Semantic ControlWhat broke: a skyscraper model collapsed after the duplication of a shared nested family — two handles, same name, different geometry — embedded across dozens of doors.

Why it broke: Revit’s shared families rely on strict naming protocols. Nesting two differently defined families with identical names should not be possible and yet it happened, and created a recursive conflict that destabilised the entire file. What appeared to be a local, contained action had global, systemic consequences. See here for more technical information on nested families.

What it revealed: I know we said that the model is the universal source of truth on a project, but maybe we took it a little too far. Wishing to count handles is fine, but this never meant that you should be able to create a literal schedules of the damn handle. It doesn’t even mean — pearl clutching alert — that they need to be modelled. On top of that, the fragility in this case didn’t come from bad modelling but from a misplaced faith in who was in charge of what. Every person assumed they were the Holy Priest of Handles, and that no one else would have the same idea. The skyscraper collapsed under the weight of task mismanagement, a fetish for handles and a pinch of bad luck.

I’m not saying this was the handle, but I’m not saying it wasn’t.3.2. Dynamo: Logic Without Foresight

I’m not saying this was the handle, but I’m not saying it wasn’t.3.2. Dynamo: Logic Without ForesightWhat broke: a Dynamo script renamed materials across a model using an ID system that didn’t enforce uniqueness. The result: multiple materials received the same name, breaking references and irreparably corrupting the file.

Why it broke: the script executed flawlessly from a syntactic perspective. The logic was correct but the assumptions behind it were not. It lacked a validation step to ensure univocity of identifiers. In essence, it treated an unreliable dataset as if it were reliable.

What it revealed: this failure exposed the gap between operational logic and design logic. Dynamo, like all visual programming tools, lulls us into a sense of transparency but visibility isn’t the same as understanding. What was missing wasn’t a warning message or a debugger; it was a reflective pause before execution. A human judgment about the trustworthiness of input. The accident didn’t happen in the nodes: it happened in the blind spot between confidence and caution.

3.3. Navisworks: Visualization as DeceptionWhat broke: a set of pipes embedded within a structural pillar went undetected during coordination because the clash test used (Hard with Normal Intersection) didn’t register triangle-level collisions.

Why it broke: the geometry of the pipes technically didn’t intersect the triangles of the pillar model. Navisworks’ default clash engine looks for triangle-on-triangle contact, not object logic or material conflict. The more thorough test (Hard with Conservative Intersection) wasn’t selected.

What it revealed: this was a failure of interface epistemology, of believing that what the software shows you is what’s real. We mistook absence of evidence for evidence of absence. And in doing so, we revealed a deeper flaw: a habit of reading BIM coordination visuals as objective truth rather than as filtered interpretations of geometry. The software didn’t hide the clash. It just didn’t name it. And in the space between those two things, a mistake risked slipping through.

It always looks so neat… how can it be wrong?

It always looks so neat… how can it be wrong?Each of these failures challenges the same core myth: that digital tools deliver certainty.