Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 6

June 28, 2025

Pride Month 2025 – Words of the Day

“And she beheld me with love,

and made me forget all my suffering.”

— Hadewijch of Brabant, Visions and Poems (13th century)

In the heart of the 13th century Low Countries, amidst convent walls and cloistered contemplation, a voice emerged that transcended both theology and genre. Hadewijch of Brabant, a Beguine mystic and poet, wrote in a Dutch that glowed with lyric fire. Her writings — part mystical vision, part romantic confession — are among the earliest known literary works in her vernacular, and among the most radically intimate articulations in medieval Europe.

Hadewijch does not write of God in distant abstractions. Her Beloved is immediate, bodily, rapturous—sometimes Christ, sometimes a genderless flame, sometimes unmistakably female in voice and presence. In her poetry and prose visions, she is taken up, undone, and re-formed by love, not metaphorically, but sensually, ecstatically, sometimes erotically.

The line between divine and human love collapses in her hands. She speaks of longing that burns the body, of kisses that tear the soul open, of gazes that erase everything else. And she does so without apology. The feminine pronoun in the fragment above — “she held me in her gaze” — appears more than once in her works, challenging attempts to flatten her mysticism into safe orthodoxy.

Whether we read Hadewijch as a mystic, a proto-lesbian poet, a visionary, or all three at once, one truth remains: her language carves out a space where love exceeds all binaries: of gender, of flesh, of faith. In that space, the divine is not male, not removed, but intensely close, tender, and transformative.

June 27, 2025

Pride Month 2025 – Art of the Day

A crucified female saint — dressed in noble garments, arms outstretched, and crowned with an improbable beard — stares out from the cross not in agony, but in defiant serenity. This is Saint Wilgefortis, a virgin martyr whose miraculous beard saved her from forced marriage, and whose cult would inspire centuries of gender-subversive devotion.

In late medieval Europe, among the many saints venerated in times of suffering, Saint Wilgefortis stood out — not just for her courage, but for her body. According to legend, she was a noblewoman in Lusitania (modern-day Portugal or Spain) whose pagan father promised her in marriage. To escape the union, she prayed to be made physically undesirable, and awoke to find a thick beard had sprouted on her face.

When she refused to marry, she was crucified by her enraged father. And yet her bearded, crucified image, clad in a gown, would become a popular object of veneration, particularly among women trapped in unhappy marriages or rigid gender roles. In shrines from Bavaria to the Low Countries, she was known by many names: Kümmernis, Liberata, Uncumber.

Her iconography blurred the sacred and the profane: a woman, bearded like a man, suffering like Christ. In some cases, pilgrims wore her image on amulets or badges, invoking her as a protector not just against violence or grief, but against the constraints of femininity enforced by patriarchy. To later viewers, especially through a queer or trans lens, Wilgefortis is more than a martyr: she is a figure of gender transformation, bodily autonomy, and holy refusal. Her beard is not a curse, but a miracle. Her crucifixion not a defeat, but a rupture in the logic of gendered sacrifice.

Alberto Stabile – The Garden and the Ash

This book took my heart, chewed it up, spit it back out, set it on fire, and then laid a flower on it. Although I was in Jerusalem almost twenty years after Alberto Stabile, in events closely related to another hotel, my life was intertwined with what had become the Colony and it is so difficult, in that very high expression of welcome and integration that hotel is by its mission, to describe the precise feeling that another world, of peace and coexistence, was possible. A feeling so intense that you want to shout it out and yet so delicate, so fragile, that you cannot even touch it or whisper it, because it would dissolve under the great weight of politics, of history, of the higher social implications.Yet this book tries, to describe that feeling, simultaneously on tiptoe and in apnea, through delicate portraits that give the impression of having been written in one night. That one great night that began with Rabin’s assassination and that the dawn of a new day never dissipated again.

June 26, 2025

Pride Month 2025 – Story of the Day

Crowned queen at the age of six and ruling in her own right by eighteen, Christina of Sweden stood as one of the most enigmatic and transgressive monarchs of the 17th century — a woman who refused marriage, dressed in men’s clothing, and filled her court with artists, philosophers, and female companions.

Christina cultivated a persona that rejected femininity and challenged dynastic expectations. She openly declared herself uninterested in marriage, calling it a “horrible and offensive thing.” She wore trousers, collected weapons, and preferred horseback riding to embroidery. But beneath the politics of refusal lay a more intimate rebellion: Christina was deeply attached to women, particularly Ebba Sparre, whom she called her “bedfellow” and “the object of my love.”

Their letters are saturated with romantic longing. While such language has often been dismissed as “romantic friendship,” Christina’s lifelong refusal of heterosexual norms, her masculine self-fashioning, and the central role of women in her emotional life suggest a queer consciousness articulated through sovereign performance.

In 1654, Christina abdicated her throne, converted to Catholicism, and relocated to Rome, where she lived as a patron of the arts and philosophy – continuing to inhabit liminal spaces of gender, faith, and sexuality until her death. She was buried in the Vatican, one of the few women to receive such honour – though she had spent her life rejecting the identity that burial presumed.

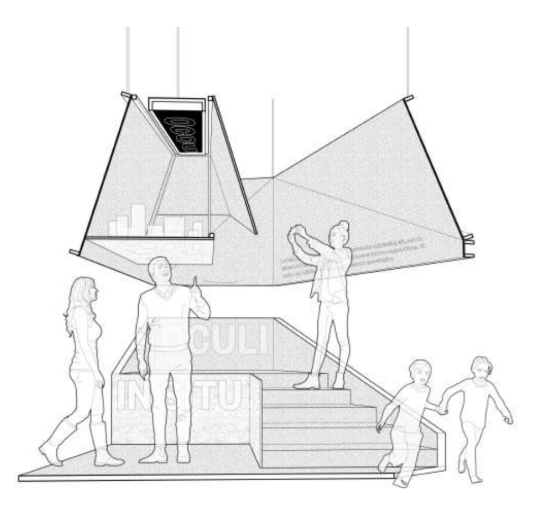

Eyes of the City: a dive back into 2019

I know I’m overdue two important posts, one on the Biennale in Venice and one on the Triennale here in Milan, but I’m still digesting many of the things I saw over there. More importantly, I’m working around the concept of adaptive and responsive architecture for an upcoming paper, so I thought I’d share some notes with you. They dive back into 2019, when Carlo Ratti & gang went to Asia with some inputs that resonate hard with this year’s Biennale. So here they are.

From Shenzhen to Venice: the Eyes of the City and the Evolution of Urban GazeSince its inception, the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) has stood as one of the most forward-looking international platforms for architectural experimentation in urban contexts, with a dual-city structure shared between Shenzhen and Hong Kong. The 2019 edition, hosted in Shenzhen’s Futian high-speed railway station, took the theme of “Urban Interactions”, situating architecture not as a mere container of social life but as an interface reshaped by digital, mobile, and automated forces.

The year 2019 was distinctive for the explicit confrontation between spatial design and emerging technologies, with a focus on how architecture could evolve when cities themselves become sentient, data-rich entities. In this context, the “Eyes of the City” section — one of the Biennale’s main curatorial frameworks — offered a particularly thought-provoking lens into the dilemmas and potentials of digitally augmented environments. The catalogue can still be downloaded for free on the exhibition’s website.

“Eyes of the City”: A Curatorial FrameworkCurated by Carlo Ratti, Michele Bonino, and Sun Yimin, the “Eyes of the City” exhibition was premised on a single powerful question: how does architecture change when every space becomes able to see by itself?

The title alludes to a condition in which buildings, infrastructures, and even urban voids are embedded with sensorial and computational capacities — especially facial recognition and AI-driven analytics — that allow them to observe, interpret, and respond to the presence of human and non-human agents. In this “aware city“, the architectural envelope is no longer passive but active, capable of modulation and reaction.

The choice of a functioning transportation node — Futian Railway Station — as the exhibition venue was not accidental. It served as both a site of transit and surveillance, exemplifying the dynamics of contemporary mobility and its coupling with biometric tracking systems. Rather than creating a neutral gallery space, the curators embedded the works within the operational logic of the station, allowing interventions to become part of the everyday experience and flows.

Interiors of the Futian Railway StationContributions and Themes

Interiors of the Futian Railway StationContributions and ThemesThe “Eyes of the City” section featured over 60 contributors from architectural firms, technology developers, academic institutions, and speculative designers. While their approaches differed, several thematic strands emerged:

Facial recognition and privacy: projects challenged the opaque logic of biometric surveillance, often proposing counter-measures or speculative scenarios of resistance.Urban intelligence and adaptation: several contributors examined how AI can be integrated into the city to enhance responsiveness, including through real-time environmental modulation or anticipatory design.Architecture of presence: the notion of presence itself was questioned—what does it mean to be “seen” by architecture? Can architecture prioritise agency without reducing humans to data points?Alternative ontologies: designers like Liam Young, Philip Beesley, and others presented architectures not as inert spaces, but as symbiotic, soft, and partially autonomous agents in their own right.The catalogue frames these projects within a broader reconsideration of spatial authorship: where before architecture spoke for the city, now it may begin to speak with the city, in an entangled dialogue of code, form, and social feedback.

Why talk about it now?Carlo Ratti’s role as curator of the Venice Biennale 2025 — six whole years after “Eyes of the City” — offers a compelling thread of continuity. While details of the upcoming Biennale are still emerging, Ratti’s long-standing interest in responsive environments, civic sensing, and architectural intelligence suggests that Venice 2025 represents a theoretical maturation of many of the ideas first tested in Shenzhen.

Indeed, Shenzhen served as a test-bed for future urbanity, especially in how architectural intelligence intersects with ethics, politics, and the aesthetics of transparency. Venice, by contrast, may serve as a stage for more reflective, institutional, and globally situated debates, especially in light of Europe’s intensifying conversations on privacy, regulation, and technological sovereignty.

So, here are my notes. Were you lucky enough to see the exhibition? Did you read the book? Lay your insights on us.

Focus 1: Digital Societies

Focus 1: Digital SocietiesCamilla Forina, from Turin’s Politecnico, curates the theoretical backbone to this section in the corresponding publication, Architecture and Urban Space After Artificial Intelligence, published in 2021 as the result of the works in Shenzhen. A few copies of the book were still available at the Biennale’s bookstore when I went there.

Palimpsest Shenzhen: rewriting the Urban Script Through Participatory Foresight“New technologies are redefining the notion of citizenship. How can we interpret the ‘eyes of the city’ idea from this perspective? This section revolved around the interaction between people, technology, and space. From observing what can be achieved when data is used to better understand society to using virtual platforms as spaces to collect people’s input, this section explored new ways in which inhabitants can get involved in the making of the city.”

Among the most conceptually layered and architecturally suggestive contributions to the Digital Societies section of the 2019 Eyes of the City exhibition, Palimpsest Shenzhen by Wee Studio proposed a critical rethinking of how urban futures can be collectively imagined, authored, and materialised. Conceived as a participatory installation embedded directly within the exhibition floor, the project took the form of a large black case — at once object and interface — inviting visitors to input their aspirations, concerns, and priorities regarding the urban development of Shenzhen. Through a hybrid of analogue and digital media, it staged a kind of urban theatre of decision-making, where each action performed within the installation generated an evolving “crowdfunding strategy” for city-making. This speculative platform was not limited to representation: it modelled an architecture of active engagement, where the typical opacity of development processes was dissolved into a public choreography of data, desire, and democratic imagination.

Wee Studio, in a design-research approach at the intersection of urban culture, technology, and participatory policy, structured the installation as a socio-political simulator. Participants were stakeholders in a scenario that, while fictional, drew on real geographic and sociopolitical data. In doing so, Palimpsest Shenzhen echoed both contemporary urban games such as Parsons’ “The Urbano Project” or MIT Media Lab’s CityScope, and historical precedents such as Yona Friedman’s “Ville Spatiale”, Cedric Price’s “Fun Palace”, or even the Delphi participatory planning experiments of the 1970s. Like these, it postulated architecture as a framework for negotiation, not a fixed product but a canvas for collective rewriting.

The use of the term “palimpsest” is critical here: rather than proposing tabula rasa interventions, the project conceptualised the city as a stratified space of successive inscriptions, where each new layer of design is aware of, but not necessarily constrained by, the past. In this sense, the installation resonated with Rem Koolhaas’ reflections on Lagos as a city of “residual structures” and with Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman’s civic platforms for participatory urbanism. Palimpsest Shenzhen brought these concerns into the computational age: its material interface recorded inputs via sensors and interactive mapping tools, simulating how citizen-driven data might inform future governance and spatial planning.

One of Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman’s participatory projects

One of Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman’s participatory projectsImportantly, its inclusion in the Eyes of the City exhibition positioned it within a broader inquiry into how architecture sees, remembers, and acts. In contrast to projects that embedded surveillance as a mode of control or visibility, this installation proposed a reverse gaze: it asked what a city might become if it could be seen through the collective eyes of its inhabitants. In doing so, it offered a counterpoint to more techno-deterministic installations by leveraging the same technologies (sensors, data visualisation, crowd interfaces) in the service of civic agency, not extraction.

The implications of Palimpsest Shenzhen extend beyond Shenzhen. It can be read as a prototype for post-platform urbanism, where algorithmic governance and grassroots intelligence converge in a single design apparatus. In a time when smart city rhetoric often sidelines the messiness of public life, this installation reclaimed the idea that cities are not only data-rich environments but narrative-rich systems, always in the process of being collectively rewritten.

Focus 2: Design Intelligence

Focus 2: Design IntelligenceIn the book, this section is expanded and commented by Valeria Federighi, also from Turin’s Politecnico, and investigates the integration of digital technologies into architectural design processes. It poses fundamental questions about how machines and AI-driven systems should behave in built environments, and how buildings might respond intelligently to their occupants. Far from a techno-utopian celebration, the section critically explores how architecture is transforming at the convergence of human judgment, algorithmic logic, and automated processes. The aim is not only to understand how these technologies operate but to question how they alter architectural agency, authorship, and the cultural processes of design.

Urban Skin: towards a Sentient Architecture of PresenceThe latest advances in Artificial Intelligence pose many ethical questions. How should machines behave? How should buildings imbued with Artificial Intelligence respond to their occupants? This section explores how the quintessential human prerogatives of “téchne” and “logos” can be hybridised with automatisms and algorithms. Ultimately, it showcases how new technologies are reshaping the ways in which we plan, design and build our cities, and new practices are emerging at the intersection of “bits and atoms”.

In Urban Skin, the collaborative work of Li Zhang, Marta Mancini, and Huishu Deng, architecture becomes an interface — at once tangible and intangible — through which the body and the city converse. The installation presented an experimental platform of responsive surfaces, modulated through sensors that capture the intensity and frequency of bodily presence. What emerges is not merely an artifice reacting to stimuli, but a provocative proposition for a new typology: one where architecture listens first, and only then expresses itself.

The system does not imitate traditional kinetic or interactive design, but it composes a soft prosthetic for public space, built from the ephemeral human interactions. The project functions on the edge of perceptibility, registering and amplifying minor shifts in bodily motion and atmospheric conditions. Rather than projecting form or space, Urban Skin yields an ambient intelligence, embedded in the fabric of architecture itself.

This approach echoes early speculative work in responsive environments — again from Cedric Price’s Fun Palace to Nicolas Negroponte’s Soft Architecture Machines — but repositions them within the contemporary logic of embedded AI, edge computing, and ubiquitous sensing. Unlike earlier analogue or centralised cybernetic systems, Urban Skin thrives on decentralisation: the computation is subtle, nearly invisible, and distributed. The project eschews spectacle in favour of phenomenological nuance, inviting a closer look into how data might not only inform design but also become its material.

Urban Skin is best understood as part of a lineage of experiments on cybernetic architecture and performative environments, drawing from mid-century explorations such as Gordon Pask’s Colloquy of Mobiles (1968), while sharply diverging from them in ethos. Rather than producing feedback loops for machine learning alone, the installation restores the primacy of the user’s embodied experience, constructing what might be called an affective interface—one where the physical response of the architecture is modulated not by explicit commands, but by presence, duration, and relationality. In doing so, Urban Skin aligns with contemporary architectural theories of relational aesthetics and new materialism, where space is understood as an emergent, co-constituted field, shaped in real time by human and nonhuman agents. It builds on recent experiments by practices like Philip Beesley’s Hylozoic Ground or the Aegis Hyposurface by dECOi, yet narrows its scope: less operatic and more intimate.

Gordon Pask’s Colloquy of Mobiles

Gordon Pask’s Colloquy of MobilesOne of the most critical dimensions of Urban Skin lies in its implicit rethinking of authorship. The system does not respond to pre-coded variables or programmable thresholds alone, but rather is co-constructed by its inhabitants, whose behaviour dynamically adjusts the parameters through which the installation calibrates itself. This is no longer the territory of architecture as an object, but of architecture as a negotiated field, an ecology of inputs and outputs continually being rewritten. From this standpoint, Urban Skin can be interpreted as an architectural argument rather than an architectural product: it suggests a shift from designing for users to designing with their ephemeral traces, challenging traditional binaries between subject and object, body and building, author and inhabitant.

The project points toward larger questions around urban interfaces, smart infrastructures, and the ethics of environmental data capture. How might buildings anticipate use without surveilling behaviour? How can responsive systems respect the unpredictability and dignity of human presence, rather than converting it into a set of extractable metrics?

In this regard, Urban Skin also stands in critical dialogue with other works in the same section, including AI-chitect’s exploration of generative design via neural networks, or Nomadic Wood’s robotic negotiation of tectonics. Yet while those works foreground the power of automation and machine logic, Urban Skin emphasises situated intelligence, not an all-knowing architecture, but an attuned one. It is less about prediction, and more about resonance. What is ultimately proposed is not a tool, nor even a system, but a prototype for spatial empathy. In an era where urbanism is increasingly shaped by metrics, sensors, and computation, Urban Skin reclaims the uncertain, the proximate, and the lived, offering a skin that does not just cover space, but feels it.

Everyone Is an Urbanist with CIIM!: Gaming the City, Designing Together

Everyone Is an Urbanist with CIIM!: Gaming the City, Designing TogetherIn Everyone Is an Urbanist with CIIM!, the boundaries between expert knowledge and civic participation, between design simulation and social negotiation, are deliberately blurred. Conceived by Weiwen Huang and Xue Chen at the Future Plus Academy, the project merges urban modelling, gamification, and public interaction through an innovative platform built around CIIM, a parametric design system adapted to the urban scale and participatory logic. What the installation offers is not simply a visualisation tool, but a new grammar of urban engagement, where the city becomes a shared interface and design becomes a game of civic intelligence.

At the heart of the project lies a playful but structured mechanism: visitors are invited to interact with the city through an intuitive game-based environment, in which adjustable parameters — density, program, mobility, form — become the levers of co-authorship. The goal is not to arrive at a final design solution, but to negotiate trade-offs, simulate the complexity of planning choices, and reflect on the cascading effects of urban form. In doing so, CIIM challenges both the authority of top-down planning and the presumed expertise of algorithmic optimisation. Instead, it enacts an agonistic, iterative form of planning, foregrounding the messiness and value of public input.

The project aligns with broader movements in civic tech and participatory design, yet its key innovation is to frame design as an accessible epistemology, one that doesn’t require professional fluency to navigate. CIIM is a modelling engine, but also an urban storytelling platform, where inhabitants, stakeholders, and non-specialists engage in a form of situated decision-making. In doing so, the project recalls the experimental ethos of Constant’s New Babylon — where the city was conceived as a field of collective authorship — and pairs it with the computational finesse of parametric platforms. CIIM’s visual language and system logic also resonate with projects like MIT’s CityScope or UNStudio’s Knowledge Models, yet it takes a more populist route. Its game-based interaction borrows from the UX principles of video games and participatory simulations, tapping into the cognitive grammar of gaming to create a non-threatening, low-barrier entry point into complex urban problems. Here, design is no longer the work of drafting a plan; it is the act of playing a meaningful role in the rules and consequences of city-making.

Constant’s New Babylon

Constant’s New BabylonWhat sets Everyone Is an Urbanist with CIIM! apart from typical consultation platforms is its embedded design agency. Participants become co-authors of morphogenetic possibilities. Every action — every toggled parameter or placed structure — translates into real-time urban consequences, immediately visible and modifiable. The interface becomes a mirror of collective values, preferences, and conflicts. This deeply interactive approach confronts the limitations of “tokenistic participation” so often found in urban planning. It offers instead a sandbox of agency, where decisions can be rehearsed, undone, or reconfigured. In this sense, CIIM is less about predicting urban futures, and more about opening up design space for deliberative futures, those forged not by certainty, but by dialogue.

CIIM also serves an educational role: it demystifies urban complexity by making visible the systemic consequences of seemingly simple design moves. It turns urban form into a set of knowable and navigable relationships, a key step toward cultivating urban literacy in an increasingly technocratic landscape. This connects the project with the broader goals of “Design Intelligence” explored in Eyes of the City, where new technologies are deployed not to replace human designers, but to expand the field of contributors to the architectural process. Its implications stretch beyond the walls of the biennale. As a prototype for planning tools in democratic societies, it opens up possibilities for participatory zoning, community-driven infrastructure, and responsive urban scenarios where public values are not post-rationalised, but pre-inscribed into the act of shaping space.

In a world where cities are increasingly governed by data, metrics, and platforms, CIIM proposes a reversal: it leverages computation not for surveillance or optimization, but for distributed authorship and civic empowerment. Rather than flattening the city into a system to be managed, it renders it again as a site of choice, difference, and speculation. The installation speaks not only to the city of Shenzhen — a city shaped by speed, negotiation, and multiplicity — but to global contexts where urban agency is in crisis. CIIM doesn’t pretend to resolve that crisis. It instead opens a space where design becomes a shared game, and urban futures are constructed not from consensus, but from constructive conflict.

June 25, 2025

Werewolves Wednesday: The Wolf-Leader (18)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter XVIII: Death and ResurrectionThe cold morning air brought Thibault back to consciousness; he tried to rise, but the extremity of his pain held him bound. He was lying on his back, with no remembrance of what had happened, seeing only the low grey sky above him. He made another effort, and turning managed to lift himself on his elbow. As he looked around him, he began to recall the events of the previous night; he recognised the breach in the wall; and then there came back to him the memory of the love meeting with the Countess and the desperate duel with the Count. The ground near him was red with blood, but the Count was no longer there; no doubt, Lestocq, who had given him this fine blow that was nailing him to the spot, had helped his master indoors; Thibault they had left there, to die like a dog, as far as they cared. He had it on the tip of his tongue to hurl after them all the maledictory wishes wherewith one would like to assail one’s cruellest enemy. But since Thibault had been no longer Thibault, and indeed during the remainder of the time that he would still be the Baron Raoul, or at least so in outward appearance, his demoniacal power had been and would continue in abeyance.

He had until nine o’clock that evening; but would he live till then? This question gave rise in Thibault to a very uneasy state of mind. If he were to die before that hour, which of them would die, he or the Baron? It seemed to him as likely to be one as the other. What, however, disturbed and angered him most was his consciousness that the misfortune which had befallen him was again owing to his own fault. He remembered now that before he had expressed the wish to be the Baron for four and twenty hours, he had said some such words as these:

“I should laugh, Raoul, if the Comte de Mont-Gobert were to take you by surprise; you would not get off so easily as if he were the Bailiff Magloire; there would be swords drawn, and blows given and received.”

At last, with a terrible effort, and suffering the while excruciating pain, Thibault succeeded in dragging himself on to one knee. He could then make out people walking along a road not far off on their way to market, and he tried to call to them, but the blood filled his mouth and nearly choked him. So he put his hat on the point of his knife and signalled to them like a shipwrecked mariner, but his strength again failing, he once more fell back unconscious. In a little while, how ever, he again awoke to sensation; he appeared to be swaying from side to side as if in a boat. He opened his eyes; the peasants, it seemed, had seen him, and although not knowing who he was, had had compassion on this handsome young man lying covered with blood, and had concocted a sort of hand-barrow out of some branches, on which they were now carrying him to Villers-Cotterets. But by the time they reached Puiseux, the wounded man felt that he could no longer bear the

movement, and begged them to put him down in the first peasant’s hut they came to, and to send a doctor to him there. The carriers took him to the house of the village priest, and left him there, Thibault before they parted, distributing gold among them from Raoul’s purse, accompanied by many thanks for all their kind offices. The priest was away saying mass, but on returning and finding the wounded man, he uttered loud cries of lamentation.

Had he been Raoul himself, Thibault could not have found a better hospital. The priest had at one time been Cure of Vauparfond, and while there had been engaged to give Raoul his first schooling. Like all country priests, he knew, or thought he knew, something about doctoring; so he examined his old pupil’s wound. The knife had passed under the shoulder-blade, through the right lung, and out between the second and third ribs.

He did not for a moment disguise to himself the seriousness of the wound, but he said nothing until the doctor had been to see it. The latter arrived and after his examination, he turned and shook his head.

“Are you going to bleed him?” asked the priest.

“What would be the use?” asked the doctor. “If it had been done at once after the wound was given, it might perhaps have helped to save him, but it would be dangerous now to disturb the blood in any way.”

“Is there any chance for him?” asked the priest, who was thinking that the less there was for the doctor to do, the more there would be for the priest.

“If his wound runs the ordinary course,” said the doctor, lowering his voice, “he will probably not last out the day.”

“You give him up then?”

“A doctor never gives up a patient, or at least if he does so, he still trusts to the possibility of nature mercifully interfering on the patient’s behalf; a clot may form and stop the hemorrhage; a cough may disturb the clot, and the patient bleed to death.”

“You think then that it is my duty to prepare the poor young man for death,” asked the curate.

“I think,” answered the doctor, shrugging his shoulders, “you would do better to leave him alone; in the first place because he is, at present, in a drowsy condition and cannot hear what you say; later on, because he will be delirious, and unable to understand you.” But the doctor was mistaken; the wounded man, drowsy as he was, overheard this conversation, more re-assuring as regards the salvation of his soul than the recovery of his body. How many things people say in the presence of sick persons, believing that they cannot hear, while all the while, they are taking in every word! In the present case, this extra acuteness of hearing may perhaps have been due to the fact that it was Thibault’s soul which was awake in Raoul’s body; if the soul belonging to it had been in this body, it would probably have succumbed more entirely to the effects of the wound.

The doctor now dressed the wound in the back, but left the front wound uncovered, merely directing that a piece of linen soaked in iced water should be kept over it. Then, having poured some drops of a sedative into a glass of water, and telling the priest to give this to the patient whenever he asked for drink, the doctor departed, saying that he would come again the following morning, but that he much feared he should take his journey for nothing.

Thibault would have liked to put in a word of his own, and to say himself what he thought about his condition, but his spirit was as if imprisoned in this dying body, and, against his will, was forced to submit to lying thus within its cell. But he could still hear the priest, who not only spoke to him, but endeavoured by shaking him to arouse him from his legthargy. Thibault found this very fatiguing, and it was lucky for the priest that the wounded man, just now, had no superhuman power, for he inwardly sent the good man to the devil, many times over.

Before long it seemed to him that some sort of hot burning pan was being inserted under the soles of his feet, his loins, his head; his blood began to circulate, then to boil, like water over a fire. His ideas became confused, his clenched jaws opened; his tongue which had been bound became loosened; some disconnected words escaped him.

“Ah, ah!” he thought to himself, “this no doubt is what the good doctor spoke about as delirium; and, for the while at least, this was his last lucid idea.

His whole life and his life had really only existed since his first acquaintance with the black wolf passed before him. He saw himself following, and failing to hit the buck; saw himself tied to the

oak-tree, and the blows of the strap falling on him; saw himself and the black wolf drawing up their compact; saw himself trying to pass the devil’s ring over Agnelette’s finger; saw himself trying to pull out the red hairs, which now covered a third of his head. Then he saw himself on his way to pay court to the pretty Madame Polet of the mill, meeting Landry, and getting rid of his rival; pursued by the farm servants, and followed by his wolves. He saw himself making the acquaintance of Madame Magloire, hunting for her, eating his share of the game, hiding behind the curtains, discovered by Maitre Magloire, flouted by the Baron of Vez, turned out by all three. Again he saw the hollow tree, with his wolves couching around it and the owls perched on its branches, and heard the sounds of the approaching violins and hautboy and saw himself looking, as Agnelette and the happy wedding party went by. He saw himself the victim of angry jealousy, endeavouring to fight against it by the help of drink, and across his troubled brain came the recollection of Francois, of Champagne, and the Inn-keeper; he heard the galloping of Baron Raoul’s horse, and he felt himself knocked down and rolling in the muddy road. Then he ceased to see himself as Thibault; in his stead arose the figure of the handsome young rider whose form he had taken for a while. Once more he was kissing Lisette, once more his lips were touching the Countess’s hand; then he was wanting to escape, but he found himself at a cross-road where three ways only met, and each of these was guarded by one of his victims: the first, by the spectre of a drowned man, that was Marcotte; the second, by a young man dying of fever on a hospital bed, that was

Landry; the third, by a wounded man, dragging himself along on one knee, and trying in vain to stand up on his mutilated leg, that was the Comte de Mont-Gobert.

He fancied that as all these things passed before him, he told the history of them one by one, and that the priest, as he listened to this strange confession, looked more like a dying man, was paler and more trembling than the man whose confession he was listening to; that be wanted to give him absolution, but that he, Thibaubt, pushed him away, shaking his head, and that he cried out with a terrible laugh: “I want no absolution! I am damned! damned! damned!”

And in the midst of all this hallucination, this delirious madness, the spirit of Thibault could hear the priest’s clock striking the hours, and as they struck he counted them. Only this clock seemed to have grown to gigantic proportions and the face of it was the blue vault of heaven, and the numbers on it were flames; and the clock was called eternity, and the monstrous pendulum, as it swung back wards and forwards called out in turn at every beat: “Never! Forever!” And so he lay and heard the long hours of the day pass one by one; and then at last the clock struck nine. At half past nine, he, Thibault, would have been Raoul, and Raoul would have been Thibault, for just four and twenty hours. As the last stroke of the hour died away, Thibault felt the fever passing from him, it was succeeded by a sensation of coldness, which almost amounted to shivering. He opened his eyes, all trembling with cold, and saw the priest at the foot of the bed saying the prayers for the dying, and the hands of the actual clock pointing to a quarter past nine.

His senses had become so acute, that, imperceptible as was their double movement, he could yet see both the larger and smaller one slowly creeping along; they were gradually nearing the critical hour; half past nine! Although the face of the clock was in darkness, it seemed illuminated by some inward light. As the minute hand approached the number 6, a spasm becoming every instant more and more violent shook the dying man; his feet were like ice, and the numbness slowly, but steadily, mounted from the feet to the knees, from the knees to the thighs, from the thighs to the lower part of the body. The sweat was running down his forehead, but he had no strength to wipe it away, nor even to ask to have it done. It was a sweat of agony which he knew every moment might be the sweat of death. All kinds of strange shapes, which had nothing of the human about them, floated before his eyes; the light faded away; wings as of bats seemed to lift his body and carry it into some twilight region, which was neither life nor death, but seemed a part of both. Then the twilight itself grew darker and darker; his eyes closed, and like a blind man stumbling in the dark, his heavy wings seemed to flap against strange and unknown things. After that he sank away into unfathomable depths, into bottomless abysses, but still he heard the sound of a bell.

The bell rang once, and scarcely had it ceased to vibrate when the dying man uttered a cry. The priest rose and went to the side of the bed; with that cry the Baron Raoul had breathed his last: it was exactly one second after the half-hour after nine.

…to be continued.

Pride Month 2025 – Words of the Day

“This reminds me of certain women who love their companions so dearly that they would not share them for all the wealth in the world—jealous as a beggar with his drinking barrel.”

— Pierre de Bourdeille, Seigneur de Brantôme, Les Dames Galantes (c. 1600, written in the 1580s but published posthumously)

Pierre de Bourdeille, known as Brantôme, was a courtier, soldier, and chronicler of scandalous tales. In Les Dames Galantes – his racy collection of anecdotes about the love lives of noblewomen – he included several stories of sapphic desire, told with voyeuristic intrigue but also surprising frankness and a kind of amused admiration.

Though Brantôme was hardly a feminist, he preserved some of the earliest European prose descriptions of romantic and erotic love between women, drawn from the courts of Catherine de’ Medici and Marguerite de Valois. His portraits of these women – often aristocratic, literate, and unapologetically sensual – reveal a social world where same-sex relationships, though officially taboo, were known, whispered about, and even at times admired for their elegance and secrecy.

Did you say Parametric?

Some words age like wine. Others, like milk. And then there are those that never had a fair shot to begin with, poured over cereal before anyone checked the expiration date. “Parametric” might just be one of them. It started in all its glory with Patrick Schumacher’s theories for Zaha Hadid, and with enlightened influencers of our industry like Paul Wintour at Parametric Monkey. And then it got hijacked by common jargon. If you’ve spent any time near architecture studios, BIM strategy meetings, or the trendier corners of LinkedIn, you’ve probably heard it till your ears bled. Parametric this, parametric that, parametricism as a brand, a badge, a vibe. It’s as if saying the word is enough to summon intelligence, innovation, or worse, budget approval.

as a brand, a badge, a vibe. It’s as if saying the word is enough to summon intelligence, innovation, or worse, budget approval.

But let’s be honest: many times, people say parametric, but what they really mean is… wavy. Or complex-looking. Or “I used Grasshopper once and now I know God”. We’ve arrived at a point where the term is so overloaded, misapplied, and glorified that it’s lost nearly all technical precision and intellectual bite. And that’s a problem—not just of semantics, but of mindset.

Because here’s the thing: in design, words are not neutral. They’re not just descriptors; they’re scaffolding. They shape how we approach problems, how we teach, how we justify choices. When we flatten “parametric” into a stylistic tick or a checkbox in a software demo, we drain it of its real, radical power: the power to embed logic, constraints, adaptability, and intelligence into our design process.

This post is not a takedown. (Well, maybe a little.) It’s our usual invitation: to pause, rewind, and dig deeper; to ask what we really mean when we say “parametric;” to distinguish between appearance and behaviour, between tool and way of thinking. And above all, to rescue a term with real potential from the clutches of aesthetic laziness and buzzword fatigue.

Let’s get into it.

1. Etymology and OriginsLet’s begin with a reality check: parametric didn’t fall from the sky into Rhino and Revit. It’s not a proprietary incantation whispered only by computational designers at dawn. It’s a word with roots: stubborn, mathematical, and surprisingly humble.

1.1. Parameters, Variables, and Constraints (a.k.a. The Unsexy Truth)I have this at the beginning of my first book but it’s been a while (seven years, to be exact).

In mathematics, a parameter is nothing fancy. It’s just a variable, specifically one that defines or modifies the behaviour of a system. Usually a curve. Parameters are the dials we turn to get a predictable result within a range of options. They live in the space between freedom and order, describing a range of possibilities within clear boundaries.

The usual example of the ellipse: if you change a, b and c, you will surely get another ellipse. Or, if you’re naughty, a circle.

The usual example of the ellipse: if you change a, b and c, you will surely get another ellipse. Or, if you’re naughty, a circle.Parametric equations describe curves and surfaces using these dials. Think circles drawn not by y = f(x), but by a pair of equations – x(t) and y(t) – that trace a path over time. It’s elegant. It’s relational. And it’s older than most of our fancy façades.

In essence, parametric means: this thing depends on that. It’s about relationships before results. Constraints before shapes. A parametric model isn’t a form: it’s a system that generates a form, reacting and recalibrating as its parameters shift.

1.2. From Spreadsheets to Scripts: a Software Family TreeThe real surprise? Your first parametric design experience might have been in Excel. Before Grasshopper, before Dynamo, before we got seduced by node spaghetti, there were spreadsheets. And they were brilliant, if correctly used. Change a cell, and everything downstream updates. That’s how your spreadsheet is supposed to work, and that’s parametric logic in action: a network of dependencies, rules, and outcomes.

The lineage continues: AutoCAD brought in constraints around 2008 (hello, associative dimensions and dynamic blocks), BIM added data and behaviour, and visual programming tools like Grasshopper let us tinker with geometry like jazz: structures that respond to rhythm, not just score. And maybe we tinkered too much. Somewhere along the way, we forgot the lineage and fixated on the tools. The iconography of the interface replaced the rigour of the logic. “Parametric” became synonymous with “I used sliders,” not “I built a system of interrelated decisions,” and that’s like mistaking Photoshop for photography.

1.3. The Philosophical Roots: Cybernetics, Systems, and the Beauty of FeedbackBehind all this is a deeper, more radical lineage, one not found in the Rhino toolbar: parametric thinking is a cousin of systems thinking, the idea that what we design isn’t isolated but embedded in feedback-rich contexts. Think Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics, with its loops and signals, its obsession with control and adaptation. Think Buckminster Fuller and his design science revolution. Think Cedric Price, who asked not what a building looks like, but what it does over time. These are all names my students are very familiar with, as they are the starting point of every discussion around BIM. See here, for instance.

In this context, parametrics isn’t just a technique; it’s a worldview. It’s about coherence through rules, intelligence through constraints, and change as a first-class citizen in the design process.

And that’s the tragedy of the buzzword: when we reduce parametric to a texture or a topology, we amputate it from this powerful philosophical spine. We trade systems for surfaces, behaviour for branding.

Not on my watch.

2. What Is Parametric Thinking?Let’s peel the word away from the façade panels. No textures, no subdivisions, no seductive gradients or swooping roofs that scream “algorithm!” Let’s talk thinking. Because, as we have seen, parametric is not a look; it’s a logic.

2.1. Relationships over GeometryIf there’s a single hill worth dying on in this whole debate, it’s this: parametric thinking privileges relationships over shapes.

It’s not about how a form looks; it’s about how it behaves when something changes. In a parametric mindset, geometry is not a static product; it’s a consequence, the result of relationships defined between elements. One move here ripples over there. Shift a node, and the model negotiates with itself.

We stop drawing things and start defining how things should relate: “this edge aligns with that axis,” “these floors must step with that terrain,” “this volume scales with this footprint, unless this constraint kicks in.” It’s still Lego blocks, maybe, but with conditional logic, dynamic constraints, and rules that care. It’s the difference between making a model and making a model that makes itself.

2.2. Constraint-Based Logic and AdaptabilityWhat are constraints, then? They aren’t limits: they’re the skeleton of flexibility; to have a system that can flex, you need to tell it where it must hold firm and how it should react when pressed. Think of your skeleton: you wouldn’t be able to move without constraints. You’d be jelly.

Like this guy.

Like this guy.Parametric thinking means we design for change, deliberately, trying to figure out which change will happen when you don’t really know. We guess. We build rules that anticipate variation, scenarios, or even future needs. It’s a form of necromancy: we accept that the designer isn’t always present, so we encode a way for its soul to be snatched out of its body, bound to a skeleton, and carry on modelling with the same design intention even when they’re gone.

Likle this guy.

Likle this guy.This is what makes parametric models so powerful in complex, data-rich environments like AEC: they can adapt to real-world inputs – climate data, site topography, programmatic requirements, budget changes- without having to redraw the entire thing from scratch.

Beware that those constraints need to be engineered and put in place by somebody. And we don’t have an army of necromancers, which is why we’re not chasing infinite possibility. We’re building smart frameworks. And yes, that’s harder than clicking “randomise.”

2.3. Feedback, Iteration, and Rule DefinitionA parametric model without feedback is something horrible to behold, and that must be why nobody’s beholding it. What makes the system sing is iteration: the ability to evaluate, adjust, and rerun scenarios based on changing data or intent.

This is where the mindset becomes truly architectural. Feedback loops allow us to test hypotheses. “What happens if the atrium gets more sun?” “How does that affect energy use, circulation, floor area?” Rather than freezing intent at the first sketch, we evolve it. The designer becomes not just a form-giver, but a rule-maker and scenario curator. That means we need to be more than just “tool fluent.” We need to be rule literate: capable of defining logic, sequencing conditions, and understanding how inputs produce outcomes. Yes, even if that means writing code, or at least, thinking like someone who does.

2.4. Parametricism vs parametricism

And now we must address the elephant in the room: Parametricism , the trademarked, capital-P doctrine championed by Patrik Schumacher and comrades.

, the trademarked, capital-P doctrine championed by Patrik Schumacher and comrades.

To be clear: I think there’s value in trying to define a style that reflects digital production. But let’s not conflate a formal agenda with a cognitive approach. Parametricism as a style has often been about curves, smoothness, complexity for complexity’s sake, and aesthetics that signal computation more than they leverage it. It’s not inherently wrong, but it is limiting when it claims dominion over what parametric means. True parametric thinking is agnostic to form. It might produce curves just as well as it might produce boxes. It might produce things that adapt invisibly to operational criteria. Its allegiance is to relationships, not results.

as a style has often been about curves, smoothness, complexity for complexity’s sake, and aesthetics that signal computation more than they leverage it. It’s not inherently wrong, but it is limiting when it claims dominion over what parametric means. True parametric thinking is agnostic to form. It might produce curves just as well as it might produce boxes. It might produce things that adapt invisibly to operational criteria. Its allegiance is to relationships, not results.

So when someone waves a curvy mesh and says “Look, it’s parametric,” feel free to ask: “What changes when you change something else?” If the answer is “nothing,” congratulations: you’ve found a static sculpture cosplaying as a system.

3. Reclaiming the WordLet’s face it: parametric has been through the wringer. Used, misused, overused, and memed into oblivion. It’s worn as a badge of honour and flung around in pitch decks like confetti, but underneath the hype, the term still holds power if we’re willing to sharpen it again.

How? Three ideas.

3.1. A Precise, Contextual UseLanguage is a tool. And when we dull our tools, we design poorly. So let’s start with some semantic spring cleaning. Parametric is not a synonym for:

FancyCurvedDigitalFuturistic“Generated by software I don’t fully understand”“Generated by software I master because I failed as a designer”It’s not about how something looks: it’s about how it’s made, why it behaves the way it does, and what happens when conditions change. Using the word precisely means acknowledging context. A parametric model is not just any digital model: it’s one whose geometry and logic are explicitly defined by parameters. A parametric design approach means you’re thinking relationally, defining systems, enabling flexibility; not just automating form.

This doesn’t mean gatekeeping. It means respect for meaning. If we’re going to teach, research, write, or build with these concepts, we owe them the dignity of clear language.

3.2. Adding Value

3.2. Adding ValueHere’s the good news: parametric thinking, when used deliberately, is a superpower. It adds value when:

context is in flux (e.g. urban constraints, programmatic changes, environmental variables);multiple scenarios need to be tested, compared, optimised;rules can be abstracted and reused across projects or phases;data-rich coordination is critical, and change is constant.Conversely, it adds no value when:

you’re using it to justify geometry you already liked;you don’t actually need variation or adaptability;the logic is harder to debug than it is to model manually;your stakeholders need clarity, and you hand them spaghetti.There’s a difference between using a tool and thinking with it. The former is aesthetic. The latter is strategic.

3.3. Be Intellectually Rigorous

3.3. Be Intellectually RigorousIf this sounds like a manifesto, good. Because reclaiming parametric isn’t just about defending a term: it’s about defending a way of thinking that architecture desperately needs. Design is not art. As much as it’s not just tech. It’s a negotiation of constraints, values, behaviours, and systems. Parametric thinking gives us a vocabulary for that negotiation, if we use it well. So let’s stop performing complexity and start practising clarity. Let’s build models that explain themselves. Let’s teach students not just how to connect nodes, but how to reason about decisions. Let’s put the rigour back into responsiveness.

Let’s retire the buzzword and bring back the mindset. Because parametric thinking isn’t dead: it’s just been marketed until it’s bleeding.

4. Out of the field, into the Classroom

4. Out of the field, into the ClassroomIt’s tempting to blame practice for the misuse of parametric. But let’s be honest: the rot often starts in schools. There, in the hallowed halls of architectural education, students are introduced to parametric tools – if and when they are – with the reverence of ancient relics and the anxiety of forbidden magic. “Here is Grasshopper,” the instructor says, unleashing a jungle of wires and sliders. “You will be confused, but it will be worth it.” And then? A semester of trial and error, formal gymnastics, and export-to-Illustrator for jury day. Some survive. Many don’t. And almost none learn what parametric thinking actually is.

How does that happen? I’ll give you two scenarios, off the top of my head.

4.1. Kill Scripting as AlienationIn theory, scripting is the new sketching: fast, iterative, responsive. I’ve written about design optioneering in the past. The designer builds relationships instead of lines, adjusts a parameter instead of redrawing a curve. It sounds liberating. In practice? It can be just another wall. When scripting is taught as a foreign language – with syntax but no semantics – it becomes a source of alienation. Tools take centre stage, while thinking exits stage left.

But here’s the trick: the power of scripting lies not in knowing code, but in learning to abstract intent. A good parametric model is like a well-composed sentence. It has structure. It has purpose. And it communicates. We don’t teach sketching by giving students a pencil and saying, “Figure it out.” Why do we do that with code? Scripting can absolutely be empowering. But only if we frame it as a design act, not a technical rite of passage.

4.2. Kill the Fetish of ComplexityComplexity. Studio culture loves it. The bigger the graph, the more intelligent the work must be, right? The more variations we have of a panel, the smarter we are. Right?

Wrong.

Complexity is often a stand-in for confidence: if I can’t explain why my form exists, I can at least say it came out of a “generative process.” Parametric modelling becomes a veil, dense enough to intimidate, mysterious enough to justify anything. We confuse complexity with another, very similar word: complication. Or worse, complexity is fetishisation.

Complexity for its own sake is the antithesis of parametric thinking, which should be about clarity through logic. A wavy façade with tons of different panels isn’t proof of intelligence. A clean rule with clear outcomes? That’s the real flex.

Let’s go back to teaching architectural students that simplicity is not a failure of ambition, but often a mark of mastery.

4.3. Toward Training Constraints and ClaritySo, where do we go from here? We need an education of precision, one that teaches parametric design not as a style or a tool, but as a way of reasoning. That starts with:

modeling with intent, not just curiosity;visualizing logic, not just form;evaluating outcomes, not just workflows;writing rules, not just tweaking sliders.We should treat parameters like design arguments, not magic knobs. Teach students to define what matters, what moves, what stays. Show them how to interrogate systems, not just assemble them. Let them script light, structure, behaviour, not just façades. And above all, let’s remind them: parametric design is not about looking smart; it’s about designing systems that can respond intelligently. Fuck the panels.

If that sounds radical, good. Education should be.

5. Conclusion: Naming, Framing, and Building BetterWords build worlds. Before we draw lines, we draw distinctions, with language. And when we let a word like parametric become sloppy, ornamental, or hollow, we’re not just miscommunicating. We’re misdesigning. So here’s a bold ideas going forward.

5.1. Naming as a Political and Conceptual ActTo name something is to claim it: to give it boundaries, meaning, and legitimacy. Naming is never neutral. When we call something parametric, we place it within a lineage of logic, adaptability, systems thinking. Why do you think there’s a  after the capitalised one?

after the capitalised one?

When we use a word to describe surface effects, aesthetic gestures, or technical gimmicks, we dilute its power, we flatten its potential to challenge assumptions, reshape workflows, and engage complexity with elegance.

Let’s be clear: how we name things reflects how we value them. When we treat parametric thinking as a style, we reduce it to a look. When we frame it as a mindset, we open it up as a method, one that resists stagnation, tolerates ambiguity, and thrives in the company of constraints. Naming is not just description. It’s a decision. It’s a declaration. It’s design.

What if we stopped treating parametrics as a visual language and started treating it as an ethical one? What if our models weren’t just reactive but responsible, capable of engaging context, accommodating change, and making trade-offs visible? What if we taught and practised parametric design not as a badge of digital sophistication, but as a commitment to clarity, adaptability, and accountability? Wouldn’t that be cool?

It would mean building systems that can explain themselves; designing with transparency, not obfuscation; using parametrics to make design more accessible, not more elitist.

Because at its best, parametric thinking is about coherence, the logic you embed in a form, what the model can become under stress. It’s about antifragility. And if we take that seriously – if we reclaim the word, reframe the work, and re-teach the process – then parametric doesn’t have to be a buzzword at all. It can become a blueprint for building better.

June 24, 2025

Pride Month 2025 – Art of the Day

Known as “La Monja Alférez” (The Lieutenant Nun), Catalina de Erauso defied every expectation of early modern gender and class. Fleeing a convent in his teens, assumed male identity, joined the Spanish army, fought in Peru and Chile, and was eventually granted a military pension by the king and — most notably — a dispensation from the Pope to continue living as a man. I guess you could be queer after all, provided you murderous your fair share of indigenous people.

Though he authored memoirs recounting these adventures, Erauso’s gender identity was never entirely defined in binary terms. He used male pronouns, dressed and acted as a man, yet also referred to his “former” life as a nun with pride. His story — thrilling, violent, filled with duels, disguises, and escapes — captivated readers across Europe.

In portraiture, this ambiguity is visually central. The figure appears young and composed, neither fully feminised nor hypermasculine. The sword, the lace collar, the steady gaze, all become part of a visual negotiation of gender, power, and performance, without any hint of cross-dressing.

Portrait of Doña Catalina de Erauso (The Lieutenant Nun), anonymous Spanish painter, c. 1620

Portrait of Doña Catalina de Erauso (The Lieutenant Nun), anonymous Spanish painter, c. 1620

Arnaldo Pomodoro in Milan: a Legacy of Form and Place

Yesterday, on the eve of his 99th birthday, Arnaldo Pomodoro passed away in Milan, the city he elected as his own to live and work in. I decided to honour his memory and his legacy with one of my urban itineraries.

A Life Dedicated to Sculpture

A Life Dedicated to SculptureBorn in Morciano di Romagna, Arnaldo Pomodoro was one of the most emblematic sculptors of the Italian 20th and early 21st centuries. Trained as a surveyor, his path into the arts was anything but linear, yet utterly transformative: he belonged to a generation of artists who emerged from the ruins of post-war Italy with a drive to reformulate the very language of sculpture, stripping away academic conventions in favor of material experimentation, symbolic abstraction, and conceptual depth.

His practice was rooted in a singular obsession: to “violate the perfection of the geometric form” and reveal its inner structure, what he described as “the complexity of the contemporary human condition.” His signature works — bronze spheres cracked open to reveal intricate inner mechanisms, spires, columns, and discs — are aesthetic and philosophical meditations. For over seven decades, Pomodoro’s career intersected with the worlds of architecture, theatre, literature, and politics. He collaborated with architects like Renzo Piano, staged theatrical sets for Beckett and Aeschylus, and engaged deeply with questions of time, memory, and collective identity.

Milan Is the Symbolic City of His WorkThough Pomodoro’s works are scattered across the globe — from the Vatican to Los Angeles, from Tehran to Brisbane — Milan is where his identity as an artist fully matured and where his legacy is most deeply rooted. It was in Milan that he settled in the 1950s and joined the cultural ferment that included Lucio Fontana, Piero Manzoni, and Bruno Munari. It was here that he held his first major exhibitions, developed his atelier and laboratory spaces, and founded the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro in 1995, a cultural institution that continues to host exhibitions, preserve his archives, and promote critical engagement with contemporary sculpture.

Milan embraced Pomodoro as one of its own. The city’s streets, piazzas, and institutions bear the imprint of his vision: the “Disco Solare” in Piazza Meda, the “Sfera con Sfera” at La Triennale, the “Colonna del Viaggiatore” beside the Teatro Manzoni, and many others. These works exist in the daily rhythm of urban life, provoking reflection amid the noise of traffic and the anonymity of modernity.

Sphere nr.5 at Milan’s Museo del 900A Memorial Itinerary

Sphere nr.5 at Milan’s Museo del 900A Memorial ItineraryThe death of Pomodoro marks the closing of a chapter in Italian art history, but not its end, as his works remain vital, present, and provocatively open to interpretation. A memorial itinerary through Milan is more than a homage; it is a gesture of collective reawakening.

By retracing his sculptures through the city, we engage not only with the material traces of his hands but with his vision of art as dialogue between form and void, surface and core, past and future. This itinerary invites us to see Milan through Pomodoro’s eyes: a city as sculpture, a body in transformation, a space layered with memory and potential. It offers a chance to slow down and observe what Pomodoro always made visible: the fractures, tensions, and beauty beneath the polished surface of things. In walking his Milan, we walk with him.

1. The Man and the Artist1.1. From the Marche Region to MilanArnaldo Pomodoro was born in 1926 in Morciano di Romagna, a small town nestled between the rolling hills of the Marche and Romagna regions. His formative years were marked by the turbulence of Fascism and the Second World War, experiences that deeply shaped his sensibility toward history, rupture, and resistance. Initially trained in technical disciplines — he earned a diploma as a surveyor and studied stage design — his path to sculpture emerged gradually, through a synthesis of craft, curiosity, and intuition.

When Pomodoro moved to Milan, in the early 1950s, the city was in the midst of cultural and economic rebirth. It was here that he found fertile ground for experimentation and dialogue, frequenting circles that included artists, poets, designers, and philosophers. The city’s industrial character, dynamic architecture, and intellectual networks all played a formative role in his evolution. His early works combined metal, relief, and texture in ways that evoked both ancient inscriptions and futuristic landscapes, foreshadowing the symbolic vocabulary he would later fully develop.

Pomodoro’s breakthrough came in the 1960s, with his iconic Sfera con Sfera and Disco series. These works launched his international recognition, with commissions from the Vatican, the United Nations, and major institutions worldwide. Yet throughout his career, Milan remained his point of return: his studio, his archive, and his foundation were all rooted there, making the city both stage and sanctuary for his enduring creative inquiry.

Sfera con Sfera at the Trinity College in Dublin1.2. The Poetics of Matter and Time

Sfera con Sfera at the Trinity College in Dublin1.2. The Poetics of Matter and TimePomodoro’s artistic language is grounded in paradox. He takes the perfection of geometric forms — spheres, columns, pyramids — and deliberately fractures them. What emerges is a sculptural tension between surface and interior, order and entropy, monumentality and fragility. His bronzes, deeply etched and incised, reveal inner worlds that seem ancient and mechanical, archaeological and alien, resonant with signs that escape precise decoding.

Time, in Pomodoro’s work, is not linear. His forms seem to hold time still while simultaneously revealing its erosion. They are fossilised yet futuristic, invoking ancient relics and space-age machines in the same gesture. His sculptures are often described as “ruins of the future” or “machines for memory”, phrases that reflect how he imbues matter with layered temporality. Bronze, his favoured medium, is both durable and malleable: a material of legacy and transformation.

Crucially, Pomodoro never saw sculpture as static. For him, it was a “process of thought,” a continuous unmaking and remaking of space. His hands bore not just form, but rhythm, excavation, and breath.

Pomodoro’s Sphere in Pesaro1.3. Connections with Architecture, Theatre, and the City

Pomodoro’s Sphere in Pesaro1.3. Connections with Architecture, Theatre, and the CityPomodoro’s interdisciplinary sensibility sets him apart from many of his contemporaries. He never confined sculpture to pedestals or galleries; instead, he consistently sought to insert art into the fabric of life. Nowhere is this more evident than in his relationships with architecture and theatre.

In architecture, Pomodoro collaborated with leading figures of modern and contemporary design, including Renzo Piano and Vittorio Gregotti. His sculptures often inhabit architectural spaces not as decoration, but as spatial and conceptual counterpoints: the Labirinto installed in via Solari, for instance, is not merely a work to view but one to enter and experience, a sculptural space that echoes the structure of ancient temples and contemporary data networks.

Arnaldo Pomodoro’s stunning Labyrinth

Arnaldo Pomodoro’s stunning LabyrinthIn the theatre, Pomodoro designed sets for plays by Beckett, Pirandello, and Aeschylus, merging spatial abstraction with dramatic tension. His scenographies were immersive landscapes of steel and shadow, evoking emotional atmospheres more than literal backdrops. For him, the stage was another kind of sculpture: ephemeral, expressive, collaborative.

Above all, however, Pomodoro saw the city itself as a living theatre, and sculpture as a script carved into its architecture. In Milan, his works are embedded in the pedestrian flow, in institutional thresholds, and in unexpected corners.

2. The Urban Itinerary2.1. “Great Disc” – Piazza MedaThe WorkLocated in the heart of Milan’s financial district, Arnaldo Pomodoro’s Grande Disco rises from the centre of Piazza Meda like an ancient celestial machine embedded in the city’s surface. Created in 1980, this monumental bronze sculpture — over 3 meters in diameter — stands on a reflective base, emphasizing its circular symmetry and internal complexity. At first glance, the work resembles a massive coin or gear, but upon closer inspection, its perfect surface is interrupted, opened, almost wounded, revealing a dense interior of sharp-edged geometric fragments, mechanical interlocks, and stratified volumes.

Unlike static monuments, the Grande Disco seems to rotate conceptually on its axis. The play between light and bronze gives it a shifting presence throughout the day — golden at sunrise, ominous at dusk —echoing its title and reinforcing the metaphor of the sun as a timeless, generative force. The sculpture evokes both the cosmic and the mechanical, inviting interpretations that range from metaphysical meditations on time and entropy to reflections on the technological unconscious of modern life.

The Context

The ContextPiazza Meda itself is a striking example of 20th-century urban planning: geometrically organised, framed by banks and commercial buildings, yet largely anonymous in character. Pomodoro’s intervention disrupts that anonymity. Rather than embellishing the space, the disc redefines it and offers a counter-monumental presence: abstract, introspective, and tactile.

The work’s scale is imposing but not overpowering, in the large context of the square; its presence transforms the pedestrian experience, introducing an unexpected pause in a zone otherwise dominated by business and traffic. For Pomodoro, the city is not merely a backdrop but a co-author: the disc’s polished and fractured bronze reflects the sky and surrounding facades, creating a constantly shifting dialogue between matter, light, and architecture.

But the disc hasn’t always been here. On 12 October 1976, the Great Disc was installed in Vigevano, in Piazza Ducale, but various controversies arose around this work, due to the stark contrast between ancient and modern, so much so that in 1979 the sculpture was moved permanently to Milan. During the construction of the Piazza Meda car park, which lasted about four years (until mid-2010), the sculpture was placed in Lanza, in front of the Piccolo Teatro di Brera.

Tips for the visitLocation: Piazza Meda, easily reachable by Metro M3 (Montenapoleone or Duomo);Best time to visit: early morning or late afternoon, when the sunlight emphasises the sculpture’s depth. 2.2. Disc in the form of a desert rose – Gallerie d’Italia, Piazza della ScalaThe work

2.2. Disc in the form of a desert rose – Gallerie d’Italia, Piazza della ScalaThe workAmong Arnaldo Pomodoro’s most poetic and enigmatic creations, Disco in forma di rosa del deserto is a monumental bronze sculpture created between 1993 and 1995. Installed in the garden courtyard of the Gallerie d’Italia on Piazza della Scala, the work draws its title from the natural formation known as a “desert rose”, a mineral cluster shaped by wind and sand, delicate in form yet forged through violent erosion.

Pomodoro’s interpretation reimagines this crystalline phenomenon on an architectural scale: a bronze disc fractured and folded into radial, sharp-edged layers, its structure alternately imploding and expanding. Unlike the more contained geometries of his Sfera or Disco series, this work suggests an explosive, centrifugal force, an act of geological becoming rather than mechanical dissection. Its surface, complex and jagged, captures the paradox at the heart of Pomodoro’s poetics: solidity that feels fluid, abstraction that remains tactile, and destruction as a form of creation.

The context

The contextThe setting of the Disco in forma di rosa del deserto is significant: it resides in the internal courtyard of the Gallerie d’Italia, a museum housed in the former headquarters of Banca Commerciale Italiana, in one of Milan’s most institutional and historic zones. This space — a cloister-like garden framed by neoclassical facades — is a place of silence and order. Pomodoro’s intervention subverts that order without negating it: his sculpture sits like a geologic intrusion in a financial temple, a reminder of natural, uncontrollable time against the measured time of capital and commerce.

The piece was acquired by Intesa Sanpaolo as part of its growing engagement with contemporary Italian art. It not only anchors the museum’s sculpture collection but also offers a critical bridge between classical architectural heritage and the radical abstraction of the 20th century.

Tips for the VisitLocation: Gallerie d’Italia, Piazza della Scala (entrance from Via Manzoni or Piazza della Scala);Museum access: entry to the courtyard is usually included in general admission; some exhibitions allow access to the courtyard freely;Best time to visit: midday, when the natural light filters through the courtyard and emphasises the sculpture’s layers and textures.2.3. Sfera Grande – Gallerie d’Italia, Piazza Scala (Garden Courtyard)The workInstalled in the Giardino di Alessandro, a secluded courtyard within the Gallerie d’Italia complex in Milan, Sfera Grande by Arnaldo Pomodoro is a striking example of the artist’s early experimentation with material, scale and form. Realised in 1966 and measuring an imposing 350 cm in diameter, this version of the iconic sphere is made not of bronze—as many others in Pomodoro’s global series are—but of fibreglass, a choice that emphasises its smoothness, lightness, and inner luminosity.

Unlike other works in the Sfera con Sfera series, which dramatize mechanical interiors rupturing through geometric containment, this Sfera Grande offers a more unified surface, yet still fractured, incised, and symbolically exposed. Its gleaming shell captures and distorts the surrounding architecture and landscape, drawing the viewer into an unstable, shifting perception of space.

“The sphere is a magical form. Its polished surface reflects what surrounds it, returning a perception of space different from the real one, and it creates mystery.”

This perception-altering quality is at the heart of Pomodoro’s sculptural philosophy: to intervene not by explaining, but by disorienting, reframing our experience of space, matter, and memory.

The context

The contextLa Sfera Grande was installed in the Giardino di Alessandro as part of the broader project to enhance and recontextualise Milan’s modern and contemporary collections within the Gallerie d’Italia. This discreet, elegant courtyard — bordered by classical architecture and shaded by plant life — becomes a meditative setting for the sphere’s reflective and symbolic presence. Here, the artwork establishes a powerful visual and spatial dialogue with both history and modernity: the garden becomes not just a backdrop but a theatrical chamber. Its fibreglass construction, unusual in Pomodoro’s large-format sculptures, contributes to a sensation of weightlessness, almost astral detachment. And yet, it is firmly anchored in the cultural memory of the city, a visual and tactile punctuation of Milan’s sculptural landscape.

2.4. Colonna del Viaggiatore – Museo del NovecentoThe workCreated in 1959, Colonna del Viaggiatore is one of Arnaldo Pomodoro’s earliest and most evocative works. Housed in the Museo del Novecento, Milan’s premier institution for 20th-century Italian art, this bronze column stands at a pivotal moment in Pomodoro’s artistic evolution, before the geometric perfection of the Sfera and Disco series, yet already revealing his fascination with layered time, encoded surfaces, and sculptural memory.

The column appears like an ancient stele, a totem etched with mysterious signs, as though inscribed in a language no longer spoken but still felt. Its verticality evokes both stability and passage, standing like a relic retrieved from the future or an artefact displaced from antiquity. The surface is densely worked: fractured, scratched, incised with delicate marks that resemble writing, cartography, or circuitry. This texture is not ornamental but essential, and it’s Pomodoro’s early exploration of surface as semantic space. Unlike later works that openly expose mechanical interiors, the Colonna remains closed, its mystery sealed, its message buried in metal. Yet this restraint amplifies its poetic power.

The context

The contextThe sculpture is part of the permanent collection of the Museo del Novecento, located in the Palazzo dell’Arengario on Piazza del Duomo. The museum traces the development of Italian art from the early avant-gardes through Arte Povera and Conceptualism, and Colonna del Viaggiatore holds a unique position within that arc: it bridges modernist abstraction with a personal mythology rooted in memory, archaeology, and symbolic language.

Placed among works by Fontana, Melotti, and Manzoni, Pomodoro’s column forms part of the dialogue that defined Milan’s post-war art scene. It reveals how, even in his early years, he was already carving a distinct path—one that merged sculptural form with the metaphysical ambitions of poetry and philosophy.

The museum also hosts Sfera n.5 from 1965.