Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 10

June 4, 2025

The Tyranny of Measurement: On Invisible Cities and Unquantifiable Value

Yes, the fault might be our current project on PowerBI, but this month I’ve been reasoning a lot around our Illuministic obsession over measurements and how that affects our approach to business intelligence in the era of Big Data. On top of this, I’ve been reading and re-reading a lot. Also, I’m getting old and maybe this means I’m getting (more) romantic.

“The emperor is he who listens to the tales of his envoys and reassembles the puzzle of his dominion in his mind’s eye. But Marco Polo spoke of cities that did not fit any puzzle.”

— Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

There is an empire that dreams of order. In this empire, maps stretch their grids across the land like nets cast over waves, hoping to still the undulant flow of life into fixed shapes. Tables are filled with numbers. Diagrams replace gestures. The city is no longer a story—it is a spreadsheet. And in the centre of this empire, a ruler waits, not for poetry, but for precision.

There is a kind of empire that measures itself not in land but in legibility. Its dominion is made of graphs, maps, metrics—where meaning is a function of clarity, and clarity a function of control. In this empire, the city must be surveyed, indexed, optimised. Every corner known, every flow anticipated. The cartographers bring measurements; the engineers, models. And that’s why Calvino’s Marco Polo is entertaining the emperor with stories of cities that aren’t mapped, like a Šahrāzād to his Šahryār, in the psychoanalytic intent of bringing a concept home.

He does not speak of borders or growth. He speaks of cities suspended in air, cities remembered only in dreams, cities unravelling like thread, cities built from silence and sorrow. He does not offer coordinates. He speaks instead of cities where memory is etched in layers of forgetting, where desires tangle in streetlights and silences. Cities suspended on stilts, cities built from the pattern of dreams, cities that are not so much places as states of being. Cities that refuse to be useful. He speaks, and the ruler listens, both enthralled and unsettled. For these cities do not fit the empire’s ledgers.

Marco Polo’s stories disarm Kublai Khan because they undermine the very idea that knowledge is equivalent to mastery. The Khan wants a world that can be grasped, arranged. He wants reports, models, proofs. Polo offers only fragments—unreliable, poetic, unrepeatable. A different kind of knowledge. One that resists capture.

“It is not the voice that commands the story: it is the ear.”

— Invisible Cities, Chapter 9

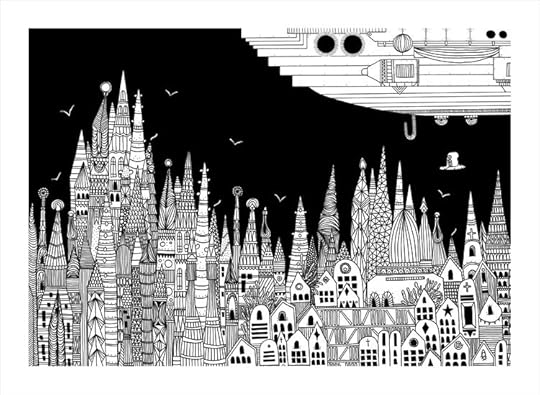

One of Karina Puente’s illustrations to Calvino’s Cities: Ipazia.

One of Karina Puente’s illustrations to Calvino’s Cities: Ipazia.We live now in a world that increasingly resembles Kublai Khan’s imagined empire—a world entranced by the measurable. Our cities are rated, our movements tracked, our knowledge quantified, our value indexed. In architecture, education, and even in the deepest chambers of culture, we are taught to believe that what matters can be counted, and what cannot be counted does not matter. We are inspired by Khan’s dream of precision. Education systems reduce learning to standardised metrics. Architecture bends toward performativity, reducing spatial experience to quantifiable outputs. Digital culture demands legibility at every turn—attention tracked, engagement scored, creativity algorithmically ranked.

But what happens to all that escapes these systems? To the intuition that precedes comprehension, the warmth of a space that cannot be diagrammed, the knowledge acquired through detours, accidents, reverie? We grazed the surface of this unease a few weeks ago, with my article on qualitative KPIs and some heated discussions that followed in private. Some of you reacted with near indignation—as if I had invented the concept. Which, of course, I didn’t.

This reflection springs from those sour words and begins with a suspicion: that in our data-driven fervour to make everything countable, we may be silencing the very dimensions of thought and life that count the most. And it begins with a proposition: that we learn, with Polo, to speak of cities not as systems, but as mysteries. Not to master them, but to dwell within them.

Fedora by Pooja Sanghani-Patel (more illustrations here)1. The Ghost in the Grid: Calvino and the Poetics of the Immeasurable

Fedora by Pooja Sanghani-Patel (more illustrations here)1. The Ghost in the Grid: Calvino and the Poetics of the ImmeasurableCalvino’s Invisible Cities is often framed as a meditation on urbanism, but I think this label misrepresents its ambition. The book is not an architectural dissertation but a cognitive labyrinth—less about cities than about how we think, describe, and fail to systematise experience, which is why I also mentioned it last month while talking about the architecture of memory.

Each of Marco Polo’s tales resists spatial logic and narrative linearity; the cities he evokes are not places to be planned or lived in, but metaphors that collapse under scrutiny and reassemble as paradox. They are epistemological devices, each city a trapdoor to a form of knowledge that cannot be diagrammed. These cities flicker at the margins of meaning—coherent enough to provoke reflection, yet evasive enough to resist classification. In this way, Invisible Cities becomes not a catalogue of possible worlds but a formal critique of measurability itself: a lattice of fragments that defies both optimisation and closure.

Consider Zobeide, a city founded by a failure. Men, haunted by an identical dream of a woman fleeing through unknown streets, build a city to recapture her. But once the streets are laid, she never returns. The dream fails to repeat itself. And so the city remains: not as fulfilment, but as residue.

“This was the city of Zobeide, where they settled, waiting for that scene to be repeated one night. None of them, asleep or awake, ever saw the woman again.”

Zobeide is the negative space of desire—a map of absence. It cannot be instrumentalised, because its reason for existing no longer exists. It endures only because of what is missing.

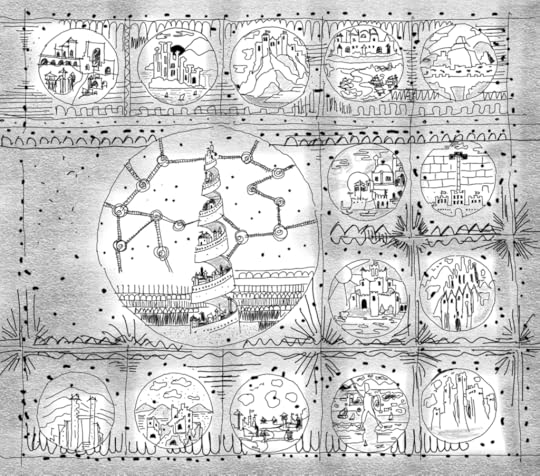

Zobeide by Colleen Corradi Brannigan (see here for information)

Zobeide by Colleen Corradi Brannigan (see here for information)Or take Baucis, the city suspended on stilts high above the ground. From the earth, it looks like scaffolding. The inhabitants—distant, airy, abstract—descend only by rope ladders and retractable baskets. The city itself is not described, only glimpsed. Its presence is eclipsed by its distance. It is there, and not there. Measurable, perhaps, in height—but not in meaning.

Baucis by Giuliana Scatuerchio (see here for details)

Baucis by Giuliana Scatuerchio (see here for details)And then Thekla: the city eternally under construction. No one sees Thekla complete, much like some construction projects here in Milan. To ask for its finished form is to miss the point entirely. Maybe that’s also the spirit of Gioia 22.

“What is the aim of a city under construction unless it is a city? Where is the plan you are following, the blueprint?”

“We will show it to you as soon as the work is finished.”

But we know it never will be.

These cities form a triad of resistance against what Calvino elsewhere called “the inferno of the living”—a world where every space must serve a function, every object a purpose, every citizen a role. In Zobeide, Baucis, and Thekla, meaning is not delivered by instruction but conjured in the reader’s act of imagining. They are not meant to be interpreted. They are meant to be dwelt in, as uncertainties.

This is what makes Invisible Cities so difficult to co-opt into frameworks like urban planning or design thinking: it does not offer prototypes, only parables. It whispers of a knowledge that is unsteady, a logic that disintegrates under scrutiny, and yet it does not dwell in aesthetics as the regular enemy of functionality. In a time when architecture increasingly pushes towards data-driven logic, and cities have the ambition to behave like machines, Calvino reminds us that a building might serve a function but the city lives with its people and is shaped by their narrative—as failure, as dream, as question. And maybe that is the only kind of city worth building.

But I digress.

2. Trading Meaning for Metrics: how we’re trained to ignoreSince the earlier stages of our education, we are taught to see what we are told is important—and to ignore what cannot be named, measured, or monetised. Another concept Calvino plays around with his whimsical Marcovaldo. This is the foundational training of life in datafied systems. What escapes capture is deemed irrelevant, ineffable, or—at best—a nice-to-have. Meaning becomes synonymous with visibility, and visibility is granted only to what aligns with pre-approved value frameworks.

Nowhere is this clearer than in how we evaluate the success of our work. Projects are filtered through KPIs, dashboards, and quantified benchmarks. We build spaces, products, lessons, and strategies, and then we ask: How many? How fast? How often? But rarely: How meaningful? How transformative? How invisible-yet-necessary?

This filtering mechanism finds its most vivid allegory in China Miéville’s The City & the City, a novel that stages two cities—Besźel and Ul Qoma—overlapping in the same geographic space, yet rendered separate by an act of “cultural discipline”. Citizens are trained to unsee the other city, to navigate shared terrain without acknowledging what is right in front of them. To notice the wrong things is to breach. Questioning the rules leads to removal from urban life.

Miéville’s conceit is fiction, and his focus certainly isn’t my trifling with digital concepts, but its logic is not unfamiliar. We, too, are conditioned to unsee in our disciplines: to disregard ambiguity, to undervalue soft outcomes, to ignore, to overlook the quiet systems that do not announce themselves in charts. This selective blindness is not an accident—it is the result of a long Enlightenment inheritance, a rationalist dream where the only knowledge that matters is that which can be made explicit. Which is fine up to a point—I’m no occultist—but one thing is to demand rationality and another thing altogether is being irrationally afraid of what looks too difficult to measure.

To stay in the realm of science fiction, N.K. Jemisin’s “Great Cities” Duology—The City We Became and The World We Make—offers a reversal of this pattern. In her vision, cities are sentient, embodied by avatars whose existence depends on the city’s collective memory, culture, and struggle. These urban entities do not emerge from blueprints—they are born of story, trauma, rhythm, resistance. They are quite literally powered by what a city means to its people. And in this sense, they point us toward a more generous epistemology—one where value is emergent, complex, and irreducibly lived.

If we borrow Jemisin’s lens, we must then ask: what in our own projects have we been trained to unsee? What narratives have been flattened into deliverables, what relationships transformed into transactions, what places stripped of their affective charge in favour of performance indicators?

As it’ll be clear to those who know me, this is not a call to abandon measurement. It is yet another invitation to rethink what we choose to measure, and why. To acknowledge that legibility is not the same as insight. That usefulness is not always immediate. That some of the most valuable dimensions of a project—trust, participation, beauty, doubt, delight—exist outside of quantification, but are no less real for it.

So here we again to ask the same question: what if metrics could be porous, qualitative, even narrative? What if evaluation began with listening, not counting? What if part of our responsibility as practitioners was to develop instruments that detect the murmurings beneath the noise? In a world increasingly governed by what is seen and sorted, this kind of seeing—attuned, critical, imperfect—might be the most radical act of all. The good news? It’s all possible.

3. Utopian Blueprints and Measured DreamsBefore data dashboards, there were cosmological diagrams. Schematics of harmony. Cities imagined not as settlements but as expressions of a universal order that was as parametric as my student’s windows from two weeks ago. One of the most vivid of these is Tommaso Campanella’s La Città del Sole, a 17th-century utopia built not of stone but of knowledge. In Campanella’s vision, the city is structured around concentric walls, each inscribed with visual knowledge: astronomy, botany, history, mathematics. The inhabitants do not just live in the city—they learn from it. The architecture itself becomes education.

[image error]Campanella’s model is seductive in its clarity. Everything has its place. Knowledge is visible, universal, accessible. But beneath this harmony lies a troubling question: Who decides what is worth knowing—and therefore worth inscribing on the walls? What remains outside this canon of enlightenment? What forms of knowledge resist visualisation entirely?

This question echoes into the present, of course. We still crave diagrams of perfect organisation, only now they come dressed as performance indicators, smart city matrices, or user analytics, but the promise is the same: a world rendered knowable, and thus governable, through structure.

Yet even Campanella, writing at the height of the rationalist dream, knew that knowledge must be embodied, shared, and lived. His city was not just a diagram—it was a community. And herein lies a seed for an alternative: what if our frameworks for evaluation were not imposed from above, but constructed collectively, through experience?

Participatory design and co-creation methodologies offer us some tools for this shift. Do you remember them? I did a whole Autodesk University class around them last year. These are not new practices, but they remain undervalued in metrics-obsessed cultures because they don’t always produce easily comparable data. Instead, they generate what philosopher Donna Haraway might call situated knowledge—local, partial, and deeply embedded in context. In participatory evaluation, value is not abstracted from the process—it is the process.

Consider an architectural project evaluated not by post-occupancy energy scores alone, but by how well it adapts to the evolving needs of its users over time. Or an educational programme assessed not only through completion rates, but through the transformative questions it enables learners to ask. These are not vague ideals—they are alternative metrics, grounded in lived interaction, reflexivity, and trust.

We might think of these metrics as relational rather than extractive. They emerge through dialogue, not from dashboards alone. They take longer to establish and resist standardisation—but they are no less rigorous. In fact, their very resistance to flattening is what makes them powerful.

If Campanella imagined a space where knowledge and life were inseparable, taking that proposition seriously leads us to translate its spirit—to create evaluative systems that do not silence the immeasurable, but make space for it. This is not a utopia. It is a viable practice.

4. Buildings of Smoke and Time: Architectural Knowledge and Its ShadowsArchitectural design has always occupied a liminal space—caught between the measurable and the felt, between what is drawn and what is lived. It trades in dimensions, materials, and regulations, but also in memory, intuition, and atmosphere. It promises permanence while shaped by time, culture, decay. Perhaps more than any other discipline, it reveals the limits of a purely quantitative approach and the dangers of a purely aesthetic one. Because architecture does not end at the linework—it begins when someone steps into it.

And yet, as design becomes more enmeshed with data, simulation, and performance analytics, it increasingly aims at solving our inefficiency through rewarding what can be modelled: thermal comfort, circulation, light diffusion, carbon counts. These are vital metrics. But they are not the whole city. The danger is not in the tools themselves, but in the assumption that what cannot be computed—because of our inability to fathom computing the qualitative—does not count. In such a landscape, the immeasurable becomes a kind of ghost—present but unacknowledged.

This spectral quality is echoed in Brian Aldiss’s The Malacia Tapestry, which depicts a city where time is forbidden to advance. Innovation is taboo. Buildings must replicate the styles of the past. But under the polished surfaces, everything is restless—characters ache for change, truth, expression. The city becomes a beautifully regulated prison, where form triumphs over experience. Aldiss’s fictional Malacia reminds us what happens when design suppresses dynamism: we get monuments to control, not containers for life.

Tim Powers’ The Anubis Gates, meanwhile, offers a hallucinatory vision of time as a spatial phenomenon, through a clever crafting of time travel as a narrative device. Its characters wander through 19th-century London, where memory and myth twist the streets into something unstable, folding the past into the present. The city is no longer a backdrop—it becomes a shifting protagonist and, in this, Powers gestures toward something architects often intuit but struggle to prove: that space holds memory, that buildings store emotion, that cities are temporal instruments as much as physical ones.

What would it mean, then, to design not only for efficiency or compliance, but for these shadowed dimensions of experience? For the emotional residue of a corridor, the psychic threshold of a staircase, the sociopolitical choreography of a plaza? These are not ineffable qualities. They are simply resistant to reduction. And as such, they call for new evaluative tools.

In some cases, these tools already exist: participatory post-occupancy evaluations, ethnographic methods, embodied mapping, and narrative walkthroughs. In others, they must be invented—hybrid approaches that combine sensor data with user diaries as it was done years ago in the entertainment field, building logbooks with observations on how people actually interact with the built environment during a trial stage. What matters is not perfect accuracy, but interpretive generosity.

Architecture has always existed at the crossroads of precision and ambiguity. A plan may be dimensioned to the millimetre, but its interpretation—once constructed and inhabited—takes on a life of its own. You can model airflow, predict daylight, and simulate foot traffic, but you cannot quantify the feeling of crossing a threshold, the warmth of filtered morning light, or the informal rituals that emerge around a kitchen counter.

Or can you?

We can try.

What we need is an expanded evaluative toolkit—one that respects the measurable while giving space to the ineffable. That listens as much as it logs. That records experience, not just efficiency. Below are some approaches—some already in use, others emerging—that move us closer to this broader architecture of understanding.

Here’s a set of practical tools to bring our goal home.

1. Participatory Post-Occupancy EvaluationsWe can call it PPOE: it all sounds more reliable with an acronym.

Beyond sensors and spreadsheets, participatory Post-Occupancy Evaluations invite building users to reflect on their lived experience. Rather than asking only “Is the room too warm?”, they might ask:

Do you feel comfortable and welcome here?How has your behaviour changed since moving into this space?Where do conversations naturally happen? Where do they die?Imagine this applied to an office.

Tools to bring this home might include:

Open-ended surveys;Walking interviews where users narrate their experience as they move through space;Participatory mapping, where users mark areas of comfort, stress, memory, or use.These methods can reveal spatial patterns invisible to traditional evaluation: desire paths, zones of appropriation, or sites of emotional tension. The result isn’t a heatmap—it’s a map of affect.

2. Ethnographic and Narrative Walkthroughs

2. Ethnographic and Narrative WalkthroughsBorrowing from anthropology, this method treats the building as a cultural text. Researchers embed themselves in the context, observe behaviours, document rituals, and—most importantly—listen.

Possible applications:

In a co-housing project, for instance, residents might co-create a timeline of shared meals, noting how seasonal changes, light, and even acoustics influence participation.In a school, students could document where they choose to sit and why, revealing power structures or inclusivity gaps not visible in the floor plan.These stories often destabilize the architect’s original assumptions—revealing that the success of a space lies not in its intended function but in its interpreted one, and might create a layer of knowledge to inform renovations or simply to make our projects better.

3. Embodied Mapping and Sensorial Diaries

3. Embodied Mapping and Sensorial DiariesWhere most spatial metrics abstract the user from the data, embodied methods reinsert them.

Examples:

Asking users to record moments when they feel disoriented, inspired, or calm while walking through a space or saying into a room;Mapping routes with sensory notations: light, noise, smell, tactility;Documenting how posture, gait, or breathing changes across spatial thresholds.This method is particularly relevant for health care, learning environments, communication infrastructure, and workplaces—where stress, comfort, and agency deeply affect user outcomes but often go unmeasured.

4. Hybrid Metrics: Sensor Data + User Diaries

4. Hybrid Metrics: Sensor Data + User DiariesTo step things up—since we haven’t invented anything so far—imagine combining real-time environmental metrics (temperature, CO₂, occupancy) with user-submitted qualitative data (journals, voice notes, drawings). A meeting room might register low occupancy—but diaries reveal that it’s avoided because the acoustics create anxiety. Or a well-used stairwell, flagged as inefficient by traffic models, might emerge as a social spine—its pauses and crossings crucial for spontaneous collaboration.

These hybrid systems are not about validating feeling through data—but about creating dialogue between the qualitative and the quantitative. Between what the model sees and what the user experiences.

5. The Living Logbook: Temporal Feedback

5. The Living Logbook: Temporal FeedbackFinally, we must treat buildings as temporal artefacts. Post-occupancy evaluation must not be a one-off snapshot, but a living process, like a logbook or ship’s journal. Over time, this logbook would record shifts in use, anomalies, anecdotes, complaints, reinterpretations.

In housing: how has the threshold changed from transition zone to social buffer?In a library: what new patterns of quiet and congregation have emerged?In public space: when did the fountain stop being a fountain and become a stage?This is not nostalgia. It is operational memory — the kind that helps future designers anticipate, learn, and adapt. What is your Digital Twin recording? What’s it monitoring?

These methods don’t ask us to abandon rigour. They ask us to expand it. To build structures of evaluation that are as layered, contradictory, and alive as the spaces we inhabit.

As Calvino might remind us: a city is not its walls, nor its streets, but the stories we tell within it.

Bookish References:Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino;La città del Sole (The City of the Sun) by Tommaso Campanella;The Great Cities Duology by N.K. Jemisin, comprised of The City We Became and The World We Make;The City & the City by China Miéville;The Malacia Tapestry by Brian Aldiss;The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers.

Bookish References:Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino;La città del Sole (The City of the Sun) by Tommaso Campanella;The Great Cities Duology by N.K. Jemisin, comprised of The City We Became and The World We Make;The City & the City by China Miéville;The Malacia Tapestry by Brian Aldiss;The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers.

Pride Month 2025: Story of the Day

Long before modern notions of gender came into form, the streets of ancient Sumer — in what is now southern Iraq — roamed with people whose identities didn’t feel the need to toe the lines of male or female. Among the most enigmatic and compelling were the Gala priests of Inanna, goddess of love, war, and transformation.

The Gala were individuals born as male, who adopted feminine speech patterns, wore women’s clothing, and performed ritual lamentations and songs in the goddess’s temples. In particular, they composed and recited sacred poetry in the eme-sal dialect — a register of Sumerian associated with female voices and deities — and were believed to channel Inanna’s power through song, grief, and ecstasy. Their role was of official cult functionaries, often held in high esteem.

Texts from the third millennium BCE describe them as “having neither father nor mother” — divine rather than natural. Some were described using words that modern scholars have interpreted as signalling gender-affirming surgery, homosexuality, or gender nonconformity, though these categories must be approached with cultural caution. What’s clear is that the Gala occupied a space well outside normative masculinity, and that this affirmation was not only accepted, but sacralized. Inanna herself was a non-conforming deity: fierce yet seductive, nurturing yet destructive, known for descending into the underworld and emerging transformed. Her followers mirrored this dynamic — living embodiments of fluidity, transformation, and the refusal to conform to fixed gender roles.

The story of the Gala priests reminds us that gender variance is not a modern deviation, but an ancient tradition — honoured, institutionalised, and spiritually powerful. In the temples of Ur and Uruk, queerness was not condemned; it was divine.

Impression of an Akkadian cylinder seal with Inanna resting her foot on a lion while Ninšubur stands before her in obedience, c. 2334- 2154 BC.

Impression of an Akkadian cylinder seal with Inanna resting her foot on a lion while Ninšubur stands before her in obedience, c. 2334- 2154 BC.

June 3, 2025

What’s with me and American Football?

I’ve been posting a little more on the topic lately, especially on Instagram, and some of you asked that question, especially from overseas: why on earth do I follow an American Football Club, and in what capacity?

It’s a legit question.

My significant otter had been playing American Football back in his hometown, in his youth. He says he fell in love with the sport after seeing Bengals@Raiders in 1990, with Bo Jackson running the whole fucking field. We had been together for a few years when he decided he wanted to give it another shot, and found a local team here in Milan. Now, if you know American Football, you know: it’s not an easy sport, it’s a demanding one both in physical and mental terms. Also, you should know me. I believe that a relationship should be supportive of whatever wild endeavour your significant otter decides to undertake, whether it’s pottery or wearing a helmet and pounding the shit out of other fellow humans on a grass field. So that’s me being supportive: I started attending matches, and I started writing about them because I needed something to do. On a particularly rainy match, I did a whole play-by-play update for a fellow teammate who was unable to participate (you can find it here and here). It wasn’t long before I started doing it on a regular basis and, later on, in an official capacity.

Flash forward 15 years, that’s what I do: I update the community on a regular basis on all the different teams we have in the club (4 flag teams, 3 of them junior teams, and one tackle team), I write posts for our website, and generally participate in trying to communicate what we do. So that’s your answer.

Pride Month 2025: Words of the Day

“O my heart’s beloved,

You are the sun of beauty,

And I — merely the eye that follows you.

He kissed me, and I became

The chalice, trembling in the hand of joy.”

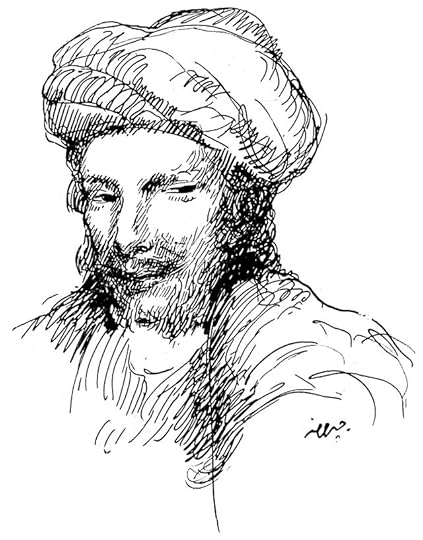

– Abu Nuwas (c. 756–814 CE) – Fragment translated by Reynold A. Nicholson

Abu Nuwas, court poet to the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad, was famous for his open celebration of same-gender love, wine, and pleasure. His verses, steeped in classical Arabic poetic tradition, mix rich sensual imagery with spiritual longing, elevating queer desire into something both erotic and metaphysical.

Rather than veil his intentions, Abu Nuwas often named his male lovers, described their bodies, their voices, and the intoxication they inspired. His love poetry draws not on allegory, but on lived passion — capturing glances in gardens, stolen kisses under moonlight, and the ecstasy of surrender. This was not subversive whispering; this was courtly, canonised art.

While later Islamic orthodoxy attempted to censor or downplay his work, his poems survived — copied, memorised, and admired for centuries. In many versions of the Thousand and One Nights, he is even a character, called the greatest poet of love and wine.

Abu Nuwas gives us a rare and radiant image of queer love not as tragic or shameful, but celebrated, sung, and sensuous. His poems challenge the Western-centric idea that queerness was always hidden in history. In Abbasid Baghdad, at least for a time, it was joyously spoken aloud — in verse, in candlelight, in love.

Abu Nuwas drawn by Khalil Gibran in 1916

Abu Nuwas drawn by Khalil Gibran in 1916

June 2, 2025

Pride Month 2025: Art of the Day

Stone statue of Xochipilli, Aztec deity of flowers, music, and same-sex desire (c. 1450–1500 CE, now in the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City)Xochipilli, Prince of Flowers: Queer Divinity in Aztec Art

Stone statue of Xochipilli, Aztec deity of flowers, music, and same-sex desire (c. 1450–1500 CE, now in the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City)Xochipilli, Prince of Flowers: Queer Divinity in Aztec ArtWhat you’re seeing is a volcanic stone sculpture showing Xochipilli, an Aztec deity part of a group of representing health, pleasure, and happiness, alongside his brothers Ixtlilton (god of health and medicine) and Macuilxóchitl (god of games). Seated in ecstatic trance, his skin and garments adorned with flowers and mushrooms some scholars have suggested to be hallucinogen. This deity has been linked with queer love, artistic creation, and spiritual pleasure, particularly with male homosexuality. Xochiquetzal is his female counterpart.

Before colonial suppression, many Indigenous cultures honored gender variance and same-sex desire through gods, rituals, and artistic expression. Xochipilli’s statue is one of the clearest pre-contact depictions of queer sanctity — a reminder that queerness is not new, Western, or marginal. It is, and has always been, a part of the sacred.

June 1, 2025

What to Catch in Milan This Month

So, what’s in town this month? Let’s take a look at a couple of things you need to catch before they leave. Some of the things I highlighted last month are still on:

Inequalities, Triennale Milano (till November 9th);the amazing I am Leonor Fini at Palazzo Reale (until June 22nd): I talked about it here;The Seduction of Colour: Andrea Solario and Renaissance between Italy and France at Museo Poldi Pezzoli with installation by Migliore+Servetto (until June 30th): I talked about it here.Sabrina Ratté’s Realia at MEET Digital Culture Centre closes today. I talked about it here.

Onwards with this month, now, and remember it’s Pride Month.

DigitalRhino Workshops at EDD 2025 | Envisioning Design Day

DigitalRhino Workshops at EDD 2025 | Envisioning Design DayAn event dedicated to digital design with Rhino, held at the IED (Istituto Europeo di Design) and featuring workshops on surface modelling and optimization, parametric patterns, renderings and AI.

Tickets and program are here.

Until June 29, 2025

Commemorating the centenary of the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, this exhibition at Palazzo Reale offers an extensive exploration of the Art Déco movement. Curated by Valerio Terraroli, the exhibition showcases over 250 works, including ceramics, glassware, furniture, jewellery, paintings, sculptures, and period films. Highlights feature creations by renowned artists and designers such as Gio Ponti, Galileo Chini, Vittorio Zecchin, Paolo Venini, Ettore Zaccari, and Alfredo Ravasco.

A notable section of the exhibition is dedicated to the Royal Hall at Milano Centrale Station, an Art Déco masterpiece. Through a selection of documents and archival materials, visitors can delve into the design and significance of this iconic space. You must catch it before it leaves. You simply must. I talked about it here.

Felice Casorati: A Retrospective, Palazzo Reale

Felice Casorati: A Retrospective, Palazzo RealeUntil June 29, 2025

After more than three decades, Palazzo Reale honours the multifaceted Italian artist Felice Casorati (1883–1963) with a comprehensive retrospective. This exhibition showcases over 100 works, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, and stage designs, tracing Casorati’s artistic journey from his early 20th-century beginnings to the 1950s. The exhibition highlights his exploration of realism, symbolism, and magic realism, and his contributions to scenography and costume design. I talked about it here. I crafted a Casorati-inspired tour of Milan here.

Antonio Canova: Beauty and the Ideal

Antonio Canova: Beauty and the IdealUntil May 2026

You have a full year of time to visit this splendid show: from 16 May 2025 to 17 May 2026, the Pinacoteca di Brera hosts “La Bellezza e l’Ideale”, marking the first major update to its Room since 2018, and offers visitors an intimate encounter with Antonio Canova’s neoclassical genius. Twelve restored plaster busts by Canova, dating from circa 1807–1818, recently discovered in Villa Canal alla Gherla (Treviso) and meticulously restored are displayed for the first time in Milan, and a rare marble bust of the Vestal Virgin (1818–1819) returns to Brera after over a century, enriching the dialogue between marble and plaster within the exhibition setting. The display also features delicate enamel miniatures from the Sommariva collection, small reproductions of key artworks once owned by the Napoleonic art patron Giovanni Battista Sommariva, now part of Brera’s historical treasures.

Hi-TechYukinori Yanagi: ICARUS at Pirelli HangarBicocca

Hi-TechYukinori Yanagi: ICARUS at Pirelli HangarBicoccaFrom 27 March to 27 July 2025, Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan hosts “ICARUS”, the first major European retrospective of Japanese artist Yukinori Yanagi. Curated by Vicente Todolí with Fiammetta Griccioli, it spans key works from the 1990s through today, offering a sweeping view of Yanagi’s thought-provoking art practice. The exhibition title obviously references the Greek myth of Icarus, an allegory for human hubris and our technological overreach, especially likened to nuclear energy, and the show features site-Specific Installations, as monumental works reshape the former industrial spaces of the Hangar’s Navate and Cubo, exploring tension between destruction and rebirth, reality and illusion. A centrepiece is The World Flag Ant Farm 2025, a living re-enactment of his Venice Biennale piece, featuring colored-sand flags that crumble under the migration of live ants, symbolising erosion of national identity. The installation Icarus Container 2025 is a labyrinth built from shipping containers and mirrors, with a light-filled tower that imbues the space with both luminosity and disorientation, and Hinomaru Illumination 2025 is a neon representation of the Japanese flag projected onto reflective water, evoking the fragility and symbolism of national emblems.

A Kind of Language: Storyboards at Fondazione Prada

A Kind of Language: Storyboards at Fondazione PradaFrom 30 January to 8 September 2025, the Osservatorio di Fondazione Prada in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele presents A Kind of Language, curated by Melissa Harris. This exhibition delves into the “secret” visual language of cinema by showcasing over 800 items, including storyboards, sketches, annotated scripts, mood boards, photographs, and notebooks, spanning nearly a century, from Georges Méliès’s early drawings to contemporary works. Contributions from more than 50 creatives across disciplines – directors (Fellini, Hitchcock, Coppola, Miyazaki), cinematographers, animators, choreographers – trace an expansive dialogue between drawing and filmmaking.

Tarek Atoui: Improvisation in 10 Days at Pirelli HangarBicocca

Tarek Atoui: Improvisation in 10 Days at Pirelli HangarBicoccaFrom 6 February to 20 July 2025, Pirelli HangarBicocca transforms its vast SHED into an immersive soundscape with Improvisation in 10 Days, the Lebanese-French artist’s first solo show in Italy. Curated by Lucia Aspesi, the exhibition explores the dynamic interplay between sound, space, and material, revealing how everyday elements become conduits for sonic exploration. Atoui investigates the acoustic properties of materials like water, air, stone, and bronze, which become tools and instruments within sculptural installations that invite sensory interaction.

Pride Month 2025: We Have Always Been Here

As I did in previous months, I will celebrate Pride Month with one post a day, which the new layout of the blog will feature right here, in the dedicated horizontal band or in the dedicated subcategory. Posts will feature in 3 different categories:

Story of the Day;Art of the Day;Words of the Day.A historical journey uncovering the presence, resilience, and beauty of queer individuals from ancient times through the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Each post will celebrate visibility and continuity, debunking the myth that queerness is a modern phenomenon and something we made up. We have always been here. And that’s where we’ll stay.

May 28, 2025

Werewolves Wednesday: The Wolf-Leader (14)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter XIV: A Village WeddingHe had made but a few steps within the forest, when he found himself surrounded by his wolves. He was pleased to see them again; he slackened his pace; he called to them; and the wolves came crowding round him. Thibault caressed them as a shepherd might his sheep, as a keeper of the hounds his dogs. They were his flock, his hunting pack; a flock with flaming eyes, a pack with looks of fire. Overhead, among the bare branches, the screech-owls were hopping and fluttering, making their plaintive calls, while the other owls uttered their melancholy cries in concert. The eyes of these night-birds shone like winged coals flying about among the trees, and there was Thibault in the middle of it all, the centre of the devilish circle.

Even as the wolves came up to fawn upon him and crouch at his feet, so the owls appeared to be attracted towards him. The tips of their silent wings brushed against his hair; some of them alighted to perch upon his shoulder.

“Ah!” murmured Thibault, “I am not then the enemy of all created things; if men hate me, the animals love me.”

He forgot what place the animals, who loved him, held in the chain of created beings. He did not remember that these animals which loved him, were those which hated mankind, and which man kind cursed.

He did not pause to reflect that these animals loved him, because he had become among men, what they were among animals; a creature of the night! a man of prey! With all these animals together, he could not do an atom of good; but, on the other hand, he could do a great deal of harm. Thibault smiled at the thought of the harm he could do.

He was still some distance from home, and he began to feel tired. He knew there was a large hollow oak somewhere near, and he took his bearings and made for it; but he would have missed his way if the wolves, who seemed to guess his thoughts, had not guided him to it. While flocks of owls hopped along from branch to branch, as if to illuminate the way, the wolves trotted along in front to show it him. The tree stood about twenty paces back from the road; it was, as I have said, an old oak, numbering not years, but centuries. Trees which live ten, twenty, thirty times the length of a man’s life, do not count their age by days and nights, but by seasons. The autumn is their twilight, the winter, their night; the spring is their dawn, the summer their day. Man envies the tree, the butterfly envies man. Forty men could not have encircled the trunk of the old oak with their arms.

The hollow made by time, that daily dislodged one more little piece of wood with the point of its scythe, was as large as an ordinarily sized room; but the entrance to it barely allowed a man to pass through. Thibault crept inside; there he found a sort of seat cut out of the thickness of the trunk, as soft and comfortable to sit in as an arm chair. Taking his place in it, and bidding good night to his wolves and his screech owls, he closed his eyes and fell asleep, or at least appeared to do so.

The wolves lay down in a circle round the tree; the owls perched in the branches. With these lights spread around its trunk, with these lights scattered about its branches, the oak had the appearance of a tree lit up for some infernal revel.

It was broad daylight when Thibault awoke; the wolves had long ago sought their hiding-places, the owls flown back to their ruins. The rain of the night before had ceased, and a ray of sunlight, one of those pale rays which are a harbinger of spring, came gliding through the naked branches of the trees, and having as yet none of the short-lived verdure of the year to shine upon, lit up the dark green of the mistletoe.

From afar came a faint sound of music, gradually it grew nearer, and the notes of two violins and a hautboy could be distinguished.

Thibault thought at first that he must be dreaming. But as it was broad daylight, and he appeared to be in perfect possession of his senses, he was obliged to acknowledge that he was wide awake, the more so, that having well rubbed his eyes, to make quite sure of the fact, the rustic sounds came as distinctly as ever to his ear. They were drawing rapidly nearer; a bird sang, answering the music of man with the music of God; and at the foot of the bush where it sat and made its song, a flower, only a snowdrop it is true was shining like a star. The sky above was

as blue as on an April day. What was the meaning of this spring like festival, now, in the heart of winter?

The notes of the bird as it sang in salutation of this bright, unexpected day, the brightness of the flower that shone as if with its radiance to thank the sun for coming to visit it, the sounds of merry

making which told the lost and unhappy man that his fellow-creatures were joining with the rest of nature in their rejoicings under the azure canopy of heaven, all the aroma of joy, all this up-springing of happiness, brought no calmer thoughts back to Thibault, but rather increased the anger and bitterness of his feelings. He would have liked the whole world to be as dark and gloomy as was his own soul. On first detecting the sounds of the approaching rural band, he thought of running away from it; but a power, stronger than his will, as it seemed to him, held him rooted to the spot; so he hid himself in the hollow of the oak and waited. Merry voices and lively songs could be heard mingling with the notes of the violins and hautboy; now and again a gun went off, or a cracker exploded; and Thibault felt sure that all these festive sounds must be occasioned by some village wedding. He was right, for he soon caught sight of a procession of villagers, all dressed in their best, with long ribands of many colours floating in the breeze, some from the women’s waists, some from the men’s hats or button-holes. They emerged into view at the end of the long lane of Ham.

They were headed by the fiddlers; then followed a few peasants, and among them some figures, which by their livery, Thibault recognised as keepers in the service of the lord of Vez. Then came Engoulevent, the second huntsman, giving his arm to an old blind woman, who was decked out with ribands like the others; then the major-domo of the Castle of Vez, as representative probably of the father of the little huntsman, giving his arm to the bride.

And the bride herself Thibault stared at her with wild fixed eyes; he endeavoured, but vainly, to persuade himself that he did not recognise her. It was impossible not to do so when she came within a few paces from where he was hiding. The bride was Agnelette.

Agnelette!

And to crown his humiliation, as if to give a final blow to his pride, no pale and trembling Agnelette dragged reluctantly to the altar, casting looks behind her of regret or remembrance, but an Agnelette as bright and happy as the bird that was singing, the snowdrop that flowered, the sunlight that was shining; an Agnelette, full of delighted pride in her wreath of orange flowers, her tulle veil and muslin dress; an Agnelette, in short, as fair and smiling as the virgin in the church at Villers-Cotterets, when dressed in her beautiful white dress at Whitsuntide.

She was, no doubt, indebted for all this finery to the Lady of the Castle, the wife of the lord of Vez, who was a true Lady Bountiful in such matters.

But the chief cause of Agnelette’s happiness and smiles was not the great love she felt towards the man who was to become her husband, but her contentment at having found what she so ardently desired, that which Thibault had wickedly promised to her without really wishing to give her, someone who would help her to support her blind old grandmother.

The musicians, the bride and bride groom, the young men and maidens, passed along the road within twenty paces of Thibault, without observing the head with its flaming hair and the eyes with their fiery gleam, looking out from the hollow of the tree. Then, as Thibault had watched them appear through the undergrowth, so he watched them disappear. As the sounds of the violins and hautboy has gradually become louder and louder, so now they became fainter and fainter, until in another quarter of an hour the forest was as silent and deserted as ever, and Thibault was left alone with his singing bird, his flowering snow drop, his glittering ray of sunlight. But a new fire of hell had been lighted in his heart, the worst of the fires of hell; that which gnaws at the vitals like the sharpest serpent’s tooth, and corrodes the blood like the most destructive poison: the fire of jealousy.

On seeing Agnelette again, so fresh and pretty, so innocently happy, and, worse still, seeing her at the moment when she was about to be married to another, Thibault, who had not given a thought to her for the last three months, Thibault, who had never had any intention of keeping the promise which he made her, Thibault now brought himself to believe that he had never ceased to love her.

He persuaded himself that Agnelette was engaged to him by oath, that Engoulevent was carrying off what be longed to him, and he almost leaped from his hiding place to rush after her and reproach her with her infidelity. Agnelette, now no longer his, at once appeared to his eyes as endowed with all the virtues and good qualities, all in short that would make it advantageous to marry her, which, when he had only to speak the word and everything would have been his, he had not even suspected.

After being the victim of so much deception, to lose what he looked upon as his own particular treasure, to which he had imagined that it would not be too late to return at any time, simply because he never dreamed that anyone would wish to take it from him, seemed to him the last stroke of ill fortune. His despair was no less profound and gloomy that it was a mute despair. He bit his fists, he knocked his head against the sides of the tree, and finally began to cry and sob. But they were not those tears and sobs which gradually soften the heart and are often kindly agents in dispersing a bad humour and reviving a better one; no, they were tears and sobs arising rather from anger than from regret, and these tears and sobs had no power to drive the hatred

out of Thibault’s heart. As some of his tears fell visibly adown his face, so it seemed that others fell on his heart within like drops of gall.

He declared that he loved Agnelette; he lamented at having lost her; nevertheless, this furious man, with all his tender love, would gladly have been able to see her fall dead, together with her bride groom, at the foot of the altar when the priest was about to join them. But happily, God, who was reserving the two children for other trials, did not allow this fatal wish to formulate itself in Thibault’s mind. They were like those who, surrounded by storm, hear the noise of the thunder and see the forked flashes of the lightning, and yet remain untouched by the deadly fluid.

Before long the shoemaker began to feel ashamed of his tears and sobs; he forced back the former, and made an effort to swallow the latter.

He came out of his lair, not quite knowing where he was, and rushed off in the direction of his hut, covering a league in a quarter of an hour; this mad race, however, by causing him to perspire, somewhat calmed him down. At last he recognised the surroundings of his home; he went into his hut as a tiger might enter its den, closed the door behind him, and went and crouched down in the darkest corner he could find in his miserable lodging. There, his elbows on his knees, his chin on his hands, he sat and thought. And what thoughts were they which occupied this unhappy, desperate man? Ask of Milton what were Satan’s thoughts after his fall.

He went over again all the old questions which had upset his mind from the beginning, which had brought despair upon so many before him, and would bring despair to so many that came after him.

Why should some be born in bondage and others be born to power? Why should there be so much inequality with regard to a thing which takes place in exactly the same way in all classes namely birth?

By what means can this game of nature’s, in which chance forever holds the cards against mankind, be made a fairer one?

And is not the only way to accomplish this, to do what the clever gamester does get the devil to back him up? he had certainly thought so once.

To cheat? He had tried that game himself. And what had he gained by it? Each time he had held a good hand, each time he had felt sure of the game, it was the devil after all who had won.

What benefit had he reaped from this deadly power that had been given him of working evil to others?

None.

Agnelette had been taken from him; the owner of the mill had driven him away; the Bailiff’s wife had made game of him.

His first wish had caused the death of poor Marcotte, and had not even procured him a haunch of the buck that he had been so ambitious to obtain, and this had been the starting point of all his disappointed longings, for he had been obliged to give the buck to the dogs so as to put them off the scent of the black wolf.

And then this rapid multiplication of devil’s hairs was appalling! He recalled the tale of the philosopher who asked for a grain of wheat, multiplied by each of the sixty-four squares of the chess board the abundant harvests of a thousand years were required to fill the last square. And he how many wishes yet remained to him? seven or eight at the outside. The unhappy man dared not look at himself either in the spring which lurked at the foot of one of the trees in the forest, or in the mirror that hung against the wall. He feared to render an exact account to himself of the time still left to him in which to exercise his power; he preferred to remain in the night of uncertainty than to face that terrible dawn which must rise when the night was over.

But still, there must be a way of continuing matters, so that the misfortunes of others should bring him good of some kind. He thought surely that if he had received a scientific education, instead of being a poor shoemaker, scarcely knowing how to read or cypher, he would have found out, by the aid of science, some combinations which would infallibly have procured for him both riches and happiness.

Poor fool! If he had been a man of learning, he would have known the legend of Doctor Faust. To what did the omnipotence conferred on him by Mephistopheles lead Faust, the dreamer, the thinker, the pre-eminent scholar? To the murder of Valentine! to Margaret’s suicide! to the pursuit of Helen of Troy, the pursuit of an empty shadow!

And, moreover, how could Thibault think coherently at all of ways and means while jealousy was raging in his heart, while he continued to picture Agnelette at the altar, giving herself for life to another than himself.

And who was that other? That wretched little Engoulevent, the man who had spied him out when he was perched in the tree, who had found his boar-spear in the bush, which had been the cause of the stripes he had received from Marcotte.

Ah! if he had but known! to him and not to Marcotte would he have willed that evil should befall! What was the physical torture he had undergone from the blows of the strap compared to the moral torture he was enduring now!

And if only ambition had not taken such hold upon him, had not borne him on the wings of pride above his sphere, what happiness might have been his, as the clever workman, able to earn as much as six francs a day, with Agnelette for his charming little housekeeper! For he had certainly been the one whom Agnelette had first loved; perhaps, although marrying another man, she still loved him. And as Thibault sat pondering over these things, he became conscious that time was passing, that night was approaching.

However modest might be the fortune of the wedded pair, however limited the desires of the peasants who had followed them, it was quite certain that bride, bridegroom and peasants were all at this hour feasting merrily together.

And he, he was sad and alone. There was no one to prepare a meal for him; and what was there in his house to eat or drink? A little bread! a little water! and solitude! in place of that blessing from heaven which we call a sister, a mistress, a wife.

But, after all, why should not he also dine merrily and abundantly? Could he not go and dine wheresoever he liked? Had he not money in his pocket from the last game he had sold to the host of the Boule-d’Or? And could he not spend on himself as much as the wedded couple and all their guests together? He had only himself to please.

“And, by my faith!” he exclaimed, “I am an idiot indeed to stay here, with my brain racked by jealousy, and my stomach with hunger, when, with the aid of a good dinner and two or three bottles of wine, I can rid myself of both torments before another hour is over. I will be off to get food, and better still, to get drink!”

In order to carry this determination into effect, Thibault took the road to Ferte-Milon, where there was an excellent restaurant, known as the Dauphin d’Or, able it was said to serve up dinners equal to those provided by his head cook for his Highness, the Duke of Orleans.

…to be continued.

Interoperability Is a Cultural Problem, Not a Technical One

I know, I know. I don’t speak about interoperability much, and ya’ll know what I think of IFC, but a recent discussion prompted me to submit to you a more articulated argument around the issue, because I do not think, in fact, that IFC is the problem. It’s people.

1. The Mirage of “Solving” Interoperability1.1. A.k.a. Why file formats alone haven’t fixed anything

Surprise, surprise.

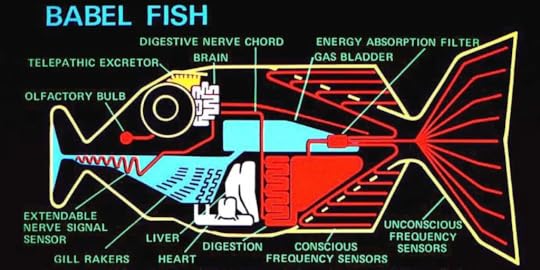

In the world of digital construction, interoperability is often viewed as a purely technical hurdle, a problem of file formats, plug-ins to untangle property sets, and One API to Rule Them All. The prevailing belief is that if only we could agree on a common data structure, standard or platform, the friction between disciplines would vanish. The industry has responded with a proliferation of interoperability solutions around structuring data: IFC and MVD, COBie, BCF, and more, each promising to act as a universal translator between software environments. The Babel Fish of BIM, if you will, without the same glorious result.

“Now it is such a bizarrely improbable coincidence that something so mind-bogglingly useful could have evolved purely by chance that some thinkers have chosen to see it as a final and clinching proof of the non-existence of God.”

Yet despite decades of standardisation efforts and the rise of so-called open formats, the actual experience on projects tells a different story. Teams still struggle to exchange information reliably. Models arrive late or incomplete. Coordination platforms become bottlenecks instead of bridges. And, perhaps most tellingly, the same questions resurface on every job: Which version of the model is this? Can I trust it? Who touched it last? Even when the IFC file arrives from someone who brags to have mastered it — trust me — the confusion remains.

Meet the Babel Fish1.2. Why’s that?

Meet the Babel Fish1.2. Why’s that?The promise of interoperability through standardised data schemes like IFC rests on a critical assumption: that data structure alone can guarantee shared understanding. But digital construction is not a purely computational endeavour. It is a fundamentally collaborative act between disciplines, each with its own set of tools, priorities, and mental models.

An IFC file may technically “contain” all the right objects — a beam, a wall, a door — but it doesn’t carry with it the context that explains why something was modelled in a certain way. It doesn’t resolve misalignments in naming conventions, object definition levels, or expectations for what constitutes a “complete” deliverable. The assumption that interoperability is achieved at the point of file exchange ignores the reality that each stakeholder reads that file through the lens of their own discipline and risk exposure.

This is not a failure of technology. It’s a mismatch between what the tools are designed to do and how people actually work together.

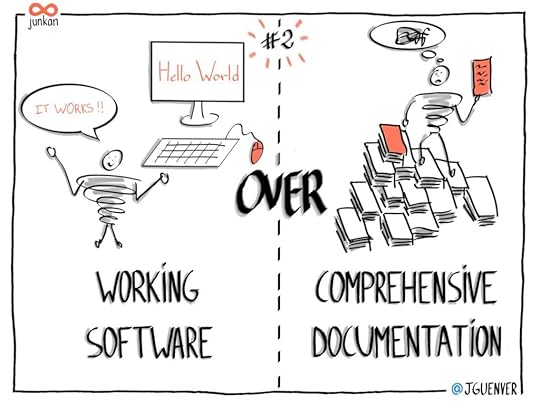

Our current solution? We document the shit out of our digital models. Which, as Agile teaches us, rarely works.

It’s one of the core principles, remember?1.3. Interoperability as a sociotechnical challenge

It’s one of the core principles, remember?1.3. Interoperability as a sociotechnical challengeTrue interoperability requires more than technical compliance and documentation — it demands cultural alignment. This means recognising that every discipline in a project team brings not just different software, but different assumptions, languages, and incentives. An architect may focus on geometry and intent; an engineer on performance and tolerances; a contractor on sequencing and risk mitigation. These aren’t just different ways of using data — they’re different ways of thinking through the model.

Interoperability, then, is not only a problem of digital infrastructure but of social infrastructure. It’s about building mutual trust, shared language, and coordinated workflows across professional boundaries. And it’s about redesigning the legal, procedural, and contractual frameworks that currently discourage meaningful collaboration, from liability fears to the rightful ban on suggesting an edit on someone else’s model.

The real barrier isn’t whether your software exports in IFC 4, and you know how to pSet like a pro. It’s whether your team can have the right conversation at the right time about what information matters, to whom, and why.

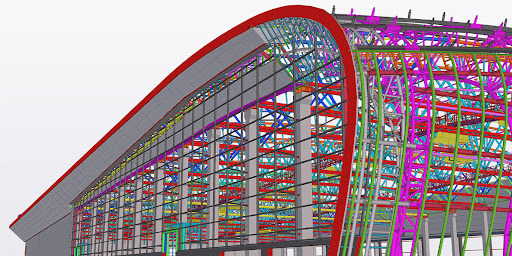

2. The Tool Paradox: Different Roles, Different NeedsGiven digital construction as a multidisciplinary ecosystem, diversity is both its strength and its weakness, as it might happen in any natural environment. The more complex an ecosystem, in fact, the more interconnected its parts and the more unpredictable the downfall. From early design to site coordination to long-term operation, each actor in the building lifecycle relies on digital tools tailored to their specific objectives, yet this diversity often clashes with the ideal of seamless interoperability. When we talk about using “a common data environment,” what we mean in practice is trying to harmonise different technological solutions and, most importantly, to fit a dozen incompatible processes into a single framework. The result often isn’t harmony. It’s a forced compromise. Let’s see how and why.

2.1. Design, Construction, Operation: Diverging Digital EcosystemsThe needs of an architect during concept design are worlds apart from those of a contractor managing sequencing or a facility manager planning long-term asset maintenance (if you’ve ever seen one, please let me know). Each role operates within a different temporal window and a different definition of precision.

Design teams prioritise spatial logic, visual intent, and formal exploration. Hence, they need freedom, fluid geometry, and tools that support iteration, not rigid structure.Contractors focus on buildability, quantities, and phasing. Hence, they care about clash detection, scheduling integration, and constructible detail, not conceptual schemes.Facility managers look for structured, persistent, queryable data tied to long-term performance. Hence, they need reliable metadata, not rapid visual prototypes.These divergent priorities generate equally divergent digital ecosystems. The software stack that empowers a designer (e.g., Rhino + Grasshopper + Dynamo + Revit) is often incompatible with the one used by the contractor (e.g., Navisworks or Synchro), let alone the CAFM system running post-handover. Even when data can be exchanged, the way it is interpreted and used is fundamentally shaped by discipline-specific goals and workflows.

Try doing that with Archicad…2.2. There’s no One Tool to Rule Them All

Try doing that with Archicad…2.2. There’s no One Tool to Rule Them AllThe construction industry has long flirted with the dream of a universal platform — a single software that could serve the entire building lifecycle. Autodesk is always pushing for Revit to be a software for all seasons, for instance. BIM, as a concept, often carries this implicit promise. In reality, this vision breaks down as soon as specialised demands come into play. What’s charming is that it breaks even if they all use the same software.

This has to do with the strategy enacted through the software of choice into the information model. No single data structure can simultaneously optimise for design fluidity, construction logistics, and asset lifecycle management without either becoming impossibly complex or diluting its value to each discipline to the point of irrelevance.

Attempts at unified data structures frequently lead to frustration: tools that try to do everything tend to do nothing particularly well and — more dangerously — they encourage the illusion of collaboration while masking the persistence of silos. Just because multiple stakeholders use the same technological solution or data structure, it doesn’t mean they’re aligned in purpose, process, or expectations.

It’s the same old matter of perspective, isn’t it?2.3. From Flexibility to Fragmentation: A Trade-off

It’s the same old matter of perspective, isn’t it?2.3. From Flexibility to Fragmentation: A Trade-offThis landscape creates a paradox. The freedom to choose the best tool for the job — essential for productivity and quality — inevitably fragments the digital environment. Every export, conversion, or workaround introduces friction and the potential for error. As a result, interoperability isn’t just a technical function. It becomes a negotiation of intent across fragmented contexts.

This is where the cultural dimension resurfaces. If teams see software as territorial — “my model,” “your file,” “their platform” — then every tool boundary becomes a political border. Instead of asking how we can share data, we end up debating whether we should. Protectionism replaces cooperation. Innovation slows down.

Real interoperability doesn’t require uniformity. It requires mutual respect for the diversity of tools and the roles they serve — and a willingness to build bridges that preserve context, not just single attributes.

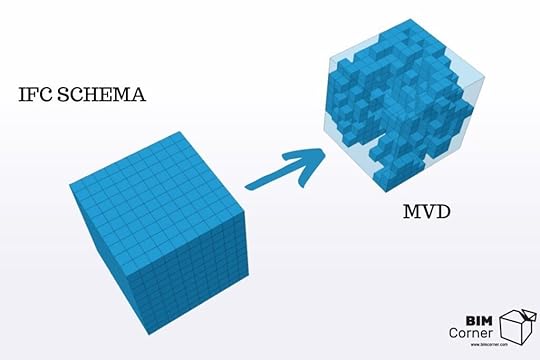

3. IDS anyone?This, in theory, is where Model View Definitions came into play. A Model View Definition (MVD) is a specification that defines a subset of the full IFC schema tailored to a particular use case or workflow within the building lifecycle, which sounds an awful lot like what we need.

3.1. What It DoesIf IFC is a rich data schema — designed to represent virtually every building element and piece of metadata imaginable — most tools and project teams don’t need or can’t handle all of its capabilities at once. That’s where the MVD comes in. An MVD queries and structures the IFC data to ensure that:

only the relevant entities, properties, and relationships for a specific purpose are included;the exported model can be reliably imported, interpreted, and used by tools aligned to that purpose. This is usually how the concept is explained (source here).

This is usually how the concept is explained (source here).Some practical examples include:

Coordination View: designed for geometric coordination between design disciplines, a.k.a. your run-of-the-mill Clash Detection;Design Transfer View: for handing off design data to other stakeholders who might be wondering what the hell it is that you’re doing with those pillars anyway;Reference View: for sharing geometry with clear visual fidelity, for people who might have to design walls around your columns.In short:

3.2. Why it Matters and Why it FailsThe MVD is the instruction manual that tells the software which parts of the IFC schema to use, for what purpose, and how.

It’s in the Junior Woodchuck Guidebook for joung BIM Managers

Even when two tools “support IFC,” they may support different MVDs… which explains why a model exported from one application might appear incomplete or garbled in another. The MVD essentially defines how interoperability is supposed to work in a given context. But if the wrong MVD is chosen — or misunderstood — the result is often frustration and data loss.

Also, consider the picture with the voxels. What happens when the subset that’s supposedly included in the MVD is not aligned with the scope, intent, and approach of the party that is developing the original model in the first place?

One of the problems is believed to be that MVD is a query. It only happens when you export the model, as many people don’t use attributes in the property set to achieve their model uses, but they just map them when exporting.

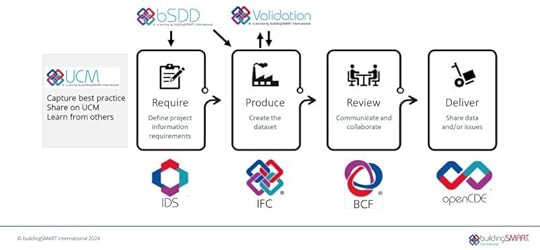

Enters IDS. The new Information Delivery Specifications promise to solve all that, as they aren’t specifications for querying the model at the end of the process: their promise is to implement a mask in the authoring tools, so that people will be warned of the data disalignments between their model and the standard data scheme as they model along.

In other words, you won’t know your Ifc sucks only after you’ve exported it – and only if you bother to check – but you could be warned step by step, as you model. Which would tremendously help, of course, as it aligns with the Agile principle of shifting quality control towards production. And it can be customised project by project. Which could be a disaster, but that’s a conversation for another time.

But will people actually bother?

This is easily one of the best schemes used to explain IDS, and I swear I couldn’t understand what was actually going on: a friend had to explain it to me.4. Misaligned Mindsets: Culture Eats Data for Breakfast

This is easily one of the best schemes used to explain IDS, and I swear I couldn’t understand what was actually going on: a friend had to explain it to me.4. Misaligned Mindsets: Culture Eats Data for BreakfastPeter Drucker’s famous adage — “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” — rings just as true in the world of digital construction. In an industry increasingly governed by models, standards, and protocols, it’s easy to assume that a structured BIM Execution Plan or a well-formed IFC export guarantees collaboration. But beneath the surface of compliance lies a deeper, more intractable problem: the human factor.

No matter how interoperable the file format, it’s the culture of the project team — the shared assumptions, behaviours, and incentives — that determines whether data will flow or stall.

Peter Drucker4.1. Protectionism, Mistrust, and “Black Box” Workflows

Peter Drucker4.1. Protectionism, Mistrust, and “Black Box” WorkflowsIn practice, many project actors operate in a mode of defensive collaboration. Rather than sharing information freely, teams tend to limit what they expose, protect their intellectual effort, and offload liability. Models become sealed containers — outputs, not shared resources. The result is a “black box” workflow, where each stakeholder receives a file, transforms it within their proprietary environment, and passes it along, without transparency or feedback.

This isn’t always malicious. Sometimes it’s about risk: who’s accountable if the model is wrong? Sometimes it’s about effort: why spend time preparing clean exports when the recipient “should have the same software”? And sometimes it’s just about habit: the inertia of siloed work inherited from CAD-era processes.

Yet, regardless of intent, the effect is the same: interoperability is reduced to transactional file exchanges. Trust is outsourced to the format, instead of being built between people.

4.2. Collaboration Stops at File Export (because contracts do)One of the most common misconceptions in digital project delivery is that exporting an IFC is the final step in collaboration. “We delivered the data.” But data without context, explanation, or dialogue is just noise. And in many projects, that’s exactly what happens.

A federated model may be hosted on a technological solution in the Common Data Environment, but if no one agrees on update cycles integrated with element responsibilities that match the progress of the project, the result is not clarity, it’s confusion. At a certain point in construction, portions of those files will have to be handed over to different subcontractors, but no one will know how to do it because the data structure still reflects the design intent of the previous stage. In these cases, the appearance of interoperability masks the absence of real cooperation. And the root issue isn’t technical capacity, even if IFC isn’t the simplest thing to master. It’s the absence of shared understanding, mutual trust, and aligned expectations — in other words, culture.

Case Example: The Broken Handoff in a BIM Coordination ProcessConsider this real-world scenario from a multidisciplinary hospital project:

the architectural team works in a parametric environment, modelling complex geometry using custom families and a grouping strategy that works for them (even if I hate groups… boy do I hate groups);the MEP engineers, on a tight schedule, rely on standard IFC imports into their discipline-specific software to coordinate the piping layout;the project has a weekly coordination meeting, with a shared glossary of naming conventions and property sets that serve the purpose of delivering a final model for maintenance.During one cycle, the architect exports a new version of the model in IFC, intending to show major updates in the surgical suite layout. But the MEP team opens the model and has no way of quickly identifying what changed. Their only option is to check spot by spot, duct by duct, if their work still has meaning. Many ducts appear misplaced or duplicated. Coordination grinds to a halt.

The problem?

Even if pSets were agreed and respected, there was no shared strategy on the here and now, on what actually mattered to the people involved in the process. The export was technically compliant. The data was “there.” But no one had discussed how changes would be interpreted, or how dependencies were being tracked, the MEP team wanted the architect to revert to PDFs with revision clouds instead of a seamless, model-based collaboration, and BIM risked being dropped altogether. The model exchange process had been devoid of its crucial element: trust. How we solved it, is a story for another time. What matters here is that interoperability had technically been accomplished, but culturally it had failed.

If construction wants to overcome its interoperability crisis, it must look beyond its own boundaries. As we often do, when, let’s seek inspiration outside the Construction Industry, because I often see IFC compared to PDFs and I’m not really sure we know what we’re talking about when we do that. Yes, because the PDF, as open as it might look, is a proprietary format. And the two things aren’t in contradiction.

Other industries — some with even more complex data landscapes — have faced similar challenges and responded not with perfect tools, but with collective agreements and shared principles that were promoted, in many cases, by the very same companies manufacturing software. That’s also how IFC started, back in the day. In each successful case, however, true interoperability was only achieved after the industry accepted that the problem wasn’t just the file format: it was the fragmentation of expectations.

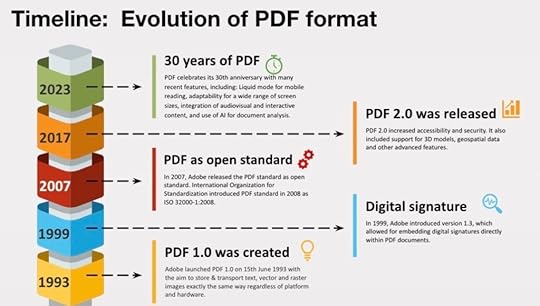

PDFs and the Publishing Industry: Standardisation Through ConsensusThe PDF (which stands for Portable Document Format, in case you didn’t know) is often cited as a success story of digital interoperability. It wasn’t the most advanced format when it launched. It didn’t offer editing, modular data, or real-time bananas. What it did offer was predictability.

The publishing industry — from graphic designers to print houses — adopted PDF not because it was imposed, but because it was badly needed to solve a common frustration: inconsistent rendering of fonts, layouts, and image placement across different devices and platforms. PDF worked because the industry agreed that the final output mattered to everyone. That cultural consensus enabled the development of stable workflows, cross-platform reliability, and trust in the “frozen” nature of content.

This is how the team at diplo explains it

This is how the team at diplo explains itIn construction, we don’t have that kind of shared consensus on what models mean at each stage, and we don’t seem to have the same level of awareness regarding how much it means that the output stays consistent after our contract is done. Also, there’s a problem of workflow. We expect deliverables to remain editable — because the work to be done would be too much if you had to start from scratch at every stage — but also reliable; flexible, but also traceable. The success of PDF lies in limiting interpretation. The AEC industry hasn’t picked a direction yet.

Excel’s XML Transformation: Embracing Modularity“But the PDF is just one example,” you might be thinking. You want another example? I’ll give you another example.

Microsoft Excel made a radical move in the early 2000s when it began introducing XML-based formats with Office XP (Excel 2002) and Office 2003. They didn’t make much noise, as they were limited in scope. The actual revolution arrived with Office 2007 (released in late 2006/early 2007), when it adopted the Office Open XML (OOXML) format. This turned what had been a proprietary, unbreakable binary file into a structured archive of modular data — spreadsheets, styles, macros, and metadata, all exposed in readable XML components. OOXML was standardised as ECMA-376 in December 2006, concurrent with Microsoft’s move, and later as ISO/IEC 29500: 2008.

The shift wasn’t about creating a “universal spreadsheet”. It was about enabling interoperability through accessibility: other applications could now parse, extract, and reuse specific data layers without needing to reverse-engineer the entire file. That opened the door to custom applications, integrations, and a wider ecosystem of tools that could speak Excel without being Excel.

The reasons for Microsoft to pursue an open strategy were several and interrelated; the change was equally driven by technological trends, customer demands, industry pressures, and regulatory expectations. For starters, adopting an XML-based file format enabled a wide array of tools and platforms to create, read, and write Office documents, thus spreading the format beyond native adopters. This fostered interoperability across different systems and applications, allowing for new levels of integration with line-of-business software and custom workflows rather than putting pressure on Microsoft to deliver all possible solutions for the multiple array of problems the software was used to tackle. In other words, the open format made it easier for developers to programmatically access and manipulate document content without relying on proprietary Office automation, broadening the ecosystem of third-party solutions and integrations.

There was also significant demand from public institutions, governments, and enterprise customers for open, standardised formats to ensure long-term access, digital preservation, and archival of documents. Governments and large organisations increasingly required open standards for procurement and compliance reasons, making openness a competitive necessity for Microsoft: the alternative was losing that chunk of the market altogether.

XML-based formats also brought several technical benefits: smaller file sizes due to ZIP compression, easier recovery from corruption, improved ability to locate and parse content, alongside the obvious ability to open and edit files with any XML editor.