Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 12

May 7, 2025

Werewolves Wednesday: The Wolf-Leader (11)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter XI: David and GoliathAfter walking the whole length of the village, they stopped before an imposing looking house at the junction of the roads leading to Longpre and Haraniont. As they neared the house the little host, with all the gallantry of a preux chevalier, went on ahead, mounted the flight of five or six steps with an agility which one could not have expected, and, by dint of standing on tip-toe, managed to reach the bell with the tips of his fingers. It should be added, that having once got hold of it, he gave it a pull which unmistakeably announced he return of the master. It was, in short, no ordinary return, but a triumphal one, for the Bailiff was bringing home a guest.

A maid, neatly dressed in her best clothes, opened the door. The Bailiff gave her an order in a low voice, and Thibault, whose adoration of beautiful women did not prevent him from liking a good dinner, gathered that these few whispered words referred to the menu which Perrine was to prepare. Then turning round, his lost addressed Thibault:

“Welcome, my dear guest, to the house of Bailiff Nepomucene Magloire.”

Thibault politely allowed Madame to pass in before him, and was then introduced into the drawing-room.

But the shoemaker now made a slip. Unaccustomed as yet to luxury, the man of the forest was not adroit enough to hide the admiration which he felt on beholding the bailiff’s home. For the first time in his life he found himself in the midst of damask curtains and gilt armchairs; he had not imagined that any one save the King, or at least his Highness the Duke of Orleans, had curtains and armchairs of this magnificence. He was unconscious that all the while Madame Magloire was closely watching him, and that his simple astonishment and delight did not escape her detective eye. However, she appeared now, after mature reflexion, to look with greater favour on the guest whom her husband had imposed upon her, and endeavoured to soften for him the glances of

her dark eyes. But her affability did not go so far as to lead her to comply with the request of Monsieur Magloire, who begged her to add to the flavour and bouquet of the champagne by pouring it out herself for her guest. Notwithstanding the entreaties of her august husband, the Bailiff’s wife refused, and under the pretext of fatigue from her walk, she retired to her own room. Before leaving the room, however, she expressed a hope to Thibault, that, as she owed him some expiation, he would not forget the way to Erneville, ending her speech with a smile which displayed a row of charming teeth. Thibault responded with so much lively pleasure in his voice that it rendered any roughness of speech less noticeable, swearing that he would sooner lose the power to

eat and drink than the remembrance of a lady who was as courteous as she was beautiful.

Madame Magloire gave him a curtsey which would have made her known as the Bailiff’s wife a mile off, and left the room.

She had hardly closed the door behind her, when Monsieur Magloire went through a pirouette in her honour, which though less light, was not less significant than the caper a school-boy executes when once he has got rid of his master.

“Ah! my dear friend,” he said, “now that we are no longer hampered by a woman’s presence, we will have a good go at the wine! Those women, they are delightful at mass or at a ball; but at table, heaven defend me, there is nobody like the men! What do you say, old fellow?”

Perrine now came in to receive her master’s orders as to what wine she was to bring up. But the gay little man was far too fastidious a judge of wines to trust a woman with such a commission as this. Indeed, women never show that reverential respect for certain old bottles which is their due, nor that delicacy of touch with which they love to be handled. He drew Perrine down as if to whisper some thing in her ear; instead of which he gave a good sound kiss to the cheek which was still young and fresh, and which did not blush sufficiently to lead to the belief that the kiss was a novelty to it.

“Well, sir,” said the girl laughing, “What is it?”

“This is it, Perrinette, my love,” said the Bailiff, “that I alone know the good brands, and as they are many in number, you might get lost among them, and so I am going to the cellar myself.” And the good man disappeared trundling off on his little legs, cheerful, alert and fantastic as those Nuremberg toys mounted on a stand, which you wind up with a key, and which, once set going, turn round and round, or go first one way and then the other, till the spring has run down; the only difference being, that this dear little man seemed wound up by the hand of God himself, and gave no sign of ever coming to a standstill.

Thibault was left alone. He rubbed his lands together, congratulating himself on laving chanced upon such a well-to-do house, with such a beautiful wife, and such an amiable husband for host and hostess. Five minutes later the door again opened, and in came the bailiff, with a bottle in either hand, and one under each arm. The two under his arms were bottles of sparkling Sillery, of the first quality, which, not being injured by shaking, were safe to be carried in a horizontal position. The two which he carried in his hands, and which he held with a respectful care which was a pleasure to behold, were, one a bottle of very old Chambertin, the other a bottle of Hermitage.

The supper hour had now come; for it must be remembered, that at the period of which we are. writing, dinner was at mid-day, and supper at six. Moreover, it had already been dark for some time before six o’clock, in this month of January, and whether it be six, or twelve o’clock at night, if one has to eat one’s meal by candle or lamp-light, it always seems to one like supper.

The Bailiff put the bottles tenderly down on the table and rang the bell. Perrinette came in.

“When will the table be ready for us, my pretty?” asked Magloire.

“Whenever Monsieur pleases,” replied Perrine. “I know Monsieur does not like waiting; so I always have everything ready in good time.”

“Go and ask Madame, then, if she is not coming; tell her, Perrine, that we do not wish to sit down without her.”

Perrine left the room.

“We may as well go into the dining-room to wait,” said the little host; “you must be hungry, my dear friend, and when I am hungry, I like to feed my eyes before I feed my stomach.”

“You seem to me to be a fine gourmand, you,” said Thibault.

“Epicure, epicure, not gourmand you must not confuse the two things. I go first, but only in order to show you the way.”

And so saying, Monsieur Magloire led his guest into the dining-room.

“Ah!” he exclaimed gaily as he went in, patting his corporation, “tell me now, do you not think this girl of mine is a capital cook, fit to serve a Cardinal? Just look now at this little supper she has spread for us; quite a simple one, and yet it pleases me more, I am sure, than would have Belshazzar’s feast.”

“On my honour, Bailiff,” said Thibault, “you are right; it is a sight to rejoice one’s heart.” And Thibault’s eyes began to shine like carbuncles.

And yet it was, as the Bailiff described it, quite an unpretentious little supper, but withal so appetising to look upon, that it was quite surprising. At one end of the table was a fine carp, boiled in vinegar and herbs, with the roe served on either side of it on a layer of parsley, dotted about with cut carrots. The opposite end was occupied by a boar-ham, mellow-flavoured, and deliciously reposing on a dish of spinach, which lay like a green islet surrounded by an ocean of gravy.

A delicate game-pie, made of two part ridges only, of which the heads appeared above the upper crust, as if ready to attack one another with their beaks, was placed in the middle of the table; while the intervening spaces were covered with side-dishes holding slices of Aries sausage, pieces of tunny-fish, swimming in beautiful green oil from Provence, anchovies sliced and arranged in all kinds of strange and fantastic patterns on a white and yellow bed of chopped eggs, and pats of butter that could only have been churned that very day. As accessories to these were two or three sorts of cheese, chosen from among those of which the chief quality is to provoke thirst, some Reims biscuits, of delightful crispness, and pears just fit to eat, showing that the master himself had taken the trouble to preserve them, and to turn them about on the store-room shelf.

Thibault was so taken up in the contemplation of this little amateur supper, that he scarcely heard the message which Perrine brought back from her mistress, who sent word that she had a sick-headache, and begged to make her excuses to her guest, with the hope that she might have the pleasure of entertaining him when he next came.

The little man gave visible signs of rejoicing on hearing his wife’s answer, breathed loudly and clapped his hands, exclaiming:

“She has a headache! she has a headache! Come along then, sit down! sit down!” And thereupon, besides the two bottles of old Macon, which had already been respectively placed within reach of the host and guest, as vin ordinaire, between the Hors-d’oeuvres and the dessert plates, he introduced the four other bottles which he had just brought up from the cellar.

Madame Magloire had, I think, acted not unwisely in refusing to sup with these stalwart champions of the table, for such was their hunger and thirst, that half the carp and the two bottles of wine disappeared without a word passing between them except such exclamations as:

“Good fish! isn’t it?”

“Capital!”

“Fine wine! isn’t it?”

“Excellent!”

The carp and the Macon being consumed, they passed on to the game pie and the Chambertin, and now their tongues began to be unloosed, especially the Bailiff’s.

By the time half the game pie, and the first bottle of Chambertin were finished, Thibault knew the history of Nepomucene Magloire; not a very complicated one, it must be confessed.

Monsieur Magloire was son to a church ornament manufacturer who had worked for the chapel belonging to his Highness the Duke of Orleans, the latter, in his religious zeal having a burning desire to obtain pictures by Albano and Titian for the sum of four to five thousand francs.

Chrysostom Magloire had placed his son Nepomucene Magloire, as head-cook with Louis’ son, his Highness the Duke of Orleans. The young man had, from infancy almost, manifested a decided taste for cooking; he had been especially attached to the Castle at Villers-Cotterets, and for thirty years presided over his Highness’s dinners, the latter introducing him to his friends as a thorough artist, and from time to time, sending for him to come up stairs to talk over culinary matters with Marshal Richelieu.

When fifty-five years of age, Magloire found himself so rounded in bulk, that it was only with some difficulty he could get through the narrow doors of the passages and offices. Fearing to be caught some day like the weasel of the fable, he asked permission to resign his post.

The Duke consented, not without regret, but with less regret than he would have felt at any other time, for he had just married Madame de Montesson, and it was only rarely now that he visited his castle at Villers-Cotterets.

His Highness had fine old-fashioned ideas as regards superannuated retainers. He, therefore, sent for Magloire, and asked him how much he had been able to save while in his service. Magloire replied that he was happily able to retire with a competence; the Prince, however, insisted upon knowing the exact amount of his little fortune, and Magloire confessed to an income of nine thousand livres.

“A man who has provided me with such a good table for thirty years,” said the Prince, “should have enough to live well upon himself for the remainder of his life.” And he made up the income to twelve thousand, so that Magloire might have a thousand livres a month to spend. Added to this, he allowed him to choose furniture for the whole of his house from his own old lumber-room; and thence came the damask curtains and gilt armchairs, which, although just a little bit faded and worn, had nevertheless preserved that appearance of grandeur which had made such an impression on Thibault.

By the time the whole of the first partridge was finished, and half the second bottle had been drunk, Thibault knew that Madame Magloire was the host’s fourth wife, a fact which seemed in his own eyes to add a good foot or two to his height.

He had also ascertained that he had married her not for her fortune, but for her beauty, having always had as great a predilection for pretty faces and beautiful statues, as for good wines and appetising victuals, and Monsieur Magloire further stated, with no sign of faltering, that, old as he was, if his wife were to die, he should have no fear in entering on a fifth marriage.

As he now passed from the Chambertin to the Hermitage, which he alternated with the Sillery, Monsieur Magloire began to speak of his wife’s qualities. She was not the personification of docility, no, quite the reverse; she was somewhat opposed to her husband’s admiration for the various wines of France, and did every thing she could, even using physical force, to prevent his too frequent visits to the cellar; while, for one who believed in living without ceremony, she on her part was too fond of dress, too much given to elaborate head-gears, English laces, and such like gewgaws, which women make part of their arsenal; she would gladly have turned the twelve hogsheads of wine, which formed the staple of her husband’s cellar, into lace for her arms, and ribands for her throat, if Monsieur Magloire had been the man to allow this metamorphosis. But, with this exception, there was not a virtue which Suzanne did not possess, and these virtues of hers, if the Bailiff was to be believed, were carried on so perfectly shaped a pair of legs, that, if by any misfortune she were to lose one, it would be quite impossible through out the district to find another that would match the leg that remained. The good man was like a regular whale, blowing out self-satisfaction from all his air-holes, as the former does sea-water. But even before all these hidden perfections of his wife had been revealed to him by the Bailiff, like a modern King Candaules ready to confide in a modern Gyges, her beauty had already made such a deep impression on the shoe-maker, that, as we have seen, he could do nothing but think of it in silence as he walked beside her, and since he had been at tale, he had continued to dream about it, listening to his host, eating the while of course, without answering, as Monsieur Magloire, delighted to have such an accommodating audience, poured forth his tales, linked one to another like a necklace of beads.

But the worthy Bailiff, having made a second excursion to the cellar, and this second excursion having produced, as the saying is, a little knot at the tip of his tongue, he began to be rather less appreciative of the rare quality which was required in his disciples by Pythagons. He, therefore, gave Thibault to understand that he had now said all that he wished to tell him concerning himself and his wife, and that it was Thibault’s turn to give him some information as regards his own circumstances, the amiable little man adding that wishing often to visit him, he wished to know more about him. Thibault felt that it was very necessary to disguise the truth; and accordingly gave himself out as a man living at ease in the country, on the revenues of two farms and of a hundred acres of land, situated near Vertefeuille.

There was, he continued, a splendid warren on these hundred acres, with a wonderful supply of red and fallow deer, boars, partridges, pheasants and hares, of which the bailiff should have some to taste. The bailiff was astonished and delighted. As we have seen, by the menu for his table, he was fond of venison, and he was carried away with joy at the thought of obtaining his game without having recourse to the poachers, and through the channel of this new friendship.

And now, the last drop of the seventh bottle having been scrupulously divided between the two glasses, they decided that it was time to stop.

The rosy champagne prime vintage of Ai, and the last bottle emptied had brought Nepomucene Magloire’s habitual good nature to the level of tender affection. He was charmed with his new friend, who tossed off his bottle in almost as good style as he did himself; he addressed him as his bosom friend, he embraced him, he made him promise that there should be a morrow to their pleasant entertainment; he stood a second time on tiptoe to give him a parting hug as he accompanied him to the door, which Thibault on his part, bending down, received with the best grace in the world.

The church clock of Erneville was striking midnight as the door closed behind the shoemaker. The fumes of the heady wine he had been drinking had begun to give him a feeling of oppression before leaving the house, but it was worse when he got into the open air. He staggered, overcome with giddiness, and went and leant with his back against a wall. What followed next was as vague and mysterious to him as the phantasmagoria of a dream. Above his head, about six or eight feet from the ground, was a window, which, as he moved to lean against the wall, had appeared to him to be lighted, although the light was shaded by double curtains. He had hardly taken up his position against the wall when he thought he heard it open. It was, he imagined, the worthy bailiff, unwilling to part with him without sending him a last farewell, and he tried to step forward so as to do honour to this gracious intention, but his attempt was unavailing. At first he thought he was stuck to the wall like a branch of ivy, but he was soon disabused of this idea. He felt a heavy weight planted first on the right shoulder and then on the left, which made his knees give way so that he slid down the wall as if to seat himself. This manoeuvre on Thibault’s part appeared to be just what the individual who was making use of him as a ladder wished him to

do, for we can no longer hide the fact that the weight so felt was that of a man. As Thibault made his forced genuflexion, the man was also lowered; “That’s right, I’Eveilli! that’s right!” he said, “So!” and with this last word, he jumped to the ground, while overhead was heard the sound of a window being shut.

Thibault had sense enough to understand two things: first, that he was mistaken for someone called L’Eveille, who was probably asleep somewhere about the premises; secondly, that his shoulders had just served some lover as a climbing ladder; both of which things caused Thibault an undefined sense of humiliation.

Accordingly, he seized hold mechanically of some floating piece of stuff which he took to be the lover’s cloak, and, with the persistency of a drunken man, continued to hang on to it.

“What are you doing that for, you scoundrel?” asked a voice, which did not seem altogether unfamiliar to the shoe-maker. “One would think you were afraid of losing me.”

“Most certainly I am afraid of losing you,” replied Thibault, “because I wish to know who it is has the impertinence to use my shoulders for a ladder.”

“Phew!” said the unknown, “it’s not you then, l’Eveille?”

“No, it is not,” replied Thibault.

“Well, whether it is you or not you, I thank you.”

“How, thank you? Ah! I dare say! thank you, indeed! You think the matter is going to rest like that, do you?”

“I had counted upon it being so, certainly.”

“Then you counted without your host.”

“Now, you blackguard, leave go of me! you are drunk!”

“Drunk! What do you mean? We only drank seven bottles between us, and the Bailiff had a good four to his share.”

“Leave go of me, you drunkard, do you hear!”

“Drunkard! you call me a drunkard, a drunkard for having drunk three bottles of wine!”

“I don’t call you a drunkard because you drank three bottles of wine, but because you let yourself get tipsy over those three unfortunate bottles.”

And, with a gesture of commiseration, and trying for the third time to release his cloak, the unknown continued:

“Now then, are you going to let go my cloak or not, you idiot?”

Thibault was at all times touchy as to the way people addressed him, but in his present state of mind his susceptibility amounted to extreme irritation.

“By the devil!” he exclaimed, “let me tell you, my fine sir, that the only idiot here is the man who gives insults in return for the services of which he has made use, and seeing that is so, I do not know what prevents me planting my fist in the middle of your face.”

This menace was scarcely out of his mouth, when, as instantly as a cannon goes off once the flame of the match has touched the powder, the blow with which Thibault had threatened his unknown adversary, came full against his own cheek.

“Take that, you beast” said the voice, which brought back to Thibault certain recollections in connection with the blow he received. “I am a good Jew, you see, and pay you back your money before weighing your coin.”

Thibault’s answer was a blow in the chest; it was well directed, and Thibault felt inwardly pleased with it himself. But it had no more effect on his antagonist than the fillip from a child’s finger would have on an oak tree. It was returned by a second blow of the fist which so far exceeded the former in the force with which it was delivered, that Thibault felt certain if the giant’s strength went on increasing in the same ratio, that a third of the kind would level him with the ground.

But the very violence of his blow brought disaster on Thibault’s unknown assailant. The latter had fallen on to one knee, and so doing, his hand, touching the ground, came in contact with a stone. Rising in fury to his feet again, with the stone in his hand, he flung it at his enemy’s head. The colossal figure uttered a sound like the bellowing of an ox, turned round on himself, and then, like an oak tree cut off by the roots, fell his whole length on the ground, and lay there in sensible.

Not knowing whether he had killed, or only wounded his adversary, Thibault took to his heels and fled, not even turning to look behind him.

…to be continued.

#WerewolvesWednesday: The Wolf-Leader (11)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter XI: David and GoliathAfter walking the whole length of the village, they stopped before an imposing looking house at the junction of the roads leading to Longpre and Haraniont. As they neared the house the little host, with all the gallantry of a preux chevalier, went on ahead, mounted the flight of five or six steps with an agility which one could not have expected, and, by dint of standing on tip-toe, managed to reach the bell with the tips of his fingers. It should be added, that having once got hold of it, he gave it a pull which unmistakeably announced he return of the master. It was, in short, no ordinary return, but a triumphal one, for the Bailiff was bringing home a guest.

A maid, neatly dressed in her best clothes, opened the door. The Bailiff gave her an order in a low voice, and Thibault, whose adoration of beautiful women did not prevent him from liking a good dinner, gathered that these few whispered words referred to the menu which Perrine was to prepare. Then turning round, his lost addressed Thibault:

“Welcome, my dear guest, to the house of Bailiff Nepomucene Magloire.”

Thibault politely allowed Madame to pass in before him, and was then introduced into the drawing-room.

But the shoemaker now made a slip. Unaccustomed as yet to luxury, the man of the forest was not adroit enough to hide the admiration which he felt on beholding the bailiff’s home. For the first time in his life he found himself in the midst of damask curtains and gilt armchairs; he had not imagined that any one save the King, or at least his Highness the Duke of Orleans, had curtains and armchairs of this magnificence. He was unconscious that all the while Madame Magloire was closely watching him, and that his simple astonishment and delight did not escape her detective eye. However, she appeared now, after mature reflexion, to look with greater favour on the guest whom her husband had imposed upon her, and endeavoured to soften for him the glances of

her dark eyes. But her affability did not go so far as to lead her to comply with the request of Monsieur Magloire, who begged her to add to the flavour and bouquet of the champagne by pouring it out herself for her guest. Notwithstanding the entreaties of her august husband, the Bailiff’s wife refused, and under the pretext of fatigue from her walk, she retired to her own room. Before leaving the room, however, she expressed a hope to Thibault, that, as she owed him some expiation, he would not forget the way to Erneville, ending her speech with a smile which displayed a row of charming teeth. Thibault responded with so much lively pleasure in his voice that it rendered any roughness of speech less noticeable, swearing that he would sooner lose the power to

eat and drink than the remembrance of a lady who was as courteous as she was beautiful.

Madame Magloire gave him a curtsey which would have made her known as the Bailiff’s wife a mile off, and left the room.

She had hardly closed the door behind her, when Monsieur Magloire went through a pirouette in her honour, which though less light, was not less significant than the caper a school-boy executes when once he has got rid of his master.

“Ah! my dear friend,” he said, “now that we are no longer hampered by a woman’s presence, we will have a good go at the wine! Those women, they are delightful at mass or at a ball; but at table, heaven defend me, there is nobody like the men! What do you say, old fellow?”

Perrine now came in to receive her master’s orders as to what wine she was to bring up. But the gay little man was far too fastidious a judge of wines to trust a woman with such a commission as this. Indeed, women never show that reverential respect for certain old bottles which is their due, nor that delicacy of touch with which they love to be handled. He drew Perrine down as if to whisper some thing in her ear; instead of which he gave a good sound kiss to the cheek which was still young and fresh, and which did not blush sufficiently to lead to the belief that the kiss was a novelty to it.

“Well, sir,” said the girl laughing, “What is it?”

“This is it, Perrinette, my love,” said the Bailiff, “that I alone know the good brands, and as they are many in number, you might get lost among them, and so I am going to the cellar myself.” And the good man disappeared trundling off on his little legs, cheerful, alert and fantastic as those Nuremberg toys mounted on a stand, which you wind up with a key, and which, once set going, turn round and round, or go first one way and then the other, till the spring has run down; the only difference being, that this dear little man seemed wound up by the hand of God himself, and gave no sign of ever coming to a standstill.

Thibault was left alone. He rubbed his lands together, congratulating himself on laving chanced upon such a well-to-do house, with such a beautiful wife, and such an amiable husband for host and hostess. Five minutes later the door again opened, and in came the bailiff, with a bottle in either hand, and one under each arm. The two under his arms were bottles of sparkling Sillery, of the first quality, which, not being injured by shaking, were safe to be carried in a horizontal position. The two which he carried in his hands, and which he held with a respectful care which was a pleasure to behold, were, one a bottle of very old Chambertin, the other a bottle of Hermitage.

The supper hour had now come; for it must be remembered, that at the period of which we are. writing, dinner was at mid-day, and supper at six. Moreover, it had already been dark for some time before six o’clock, in this month of January, and whether it be six, or twelve o’clock at night, if one has to eat one’s meal by candle or lamp-light, it always seems to one like supper.

The Bailiff put the bottles tenderly down on the table and rang the bell. Perrinette came in.

“When will the table be ready for us, my pretty?” asked Magloire.

“Whenever Monsieur pleases,” replied Perrine. “I know Monsieur does not like waiting; so I always have everything ready in good time.”

“Go and ask Madame, then, if she is not coming; tell her, Perrine, that we do not wish to sit down without her.”

Perrine left the room.

“We may as well go into the dining-room to wait,” said the little host; “you must be hungry, my dear friend, and when I am hungry, I like to feed my eyes before I feed my stomach.”

“You seem to me to be a fine gourmand, you,” said Thibault.

“Epicure, epicure, not gourmand you must not confuse the two things. I go first, but only in order to show you the way.”

And so saying, Monsieur Magloire led his guest into the dining-room.

“Ah!” he exclaimed gaily as he went in, patting his corporation, “tell me now, do you not think this girl of mine is a capital cook, fit to serve a Cardinal? Just look now at this little supper she has spread for us; quite a simple one, and yet it pleases me more, I am sure, than would have Belshazzar’s feast.”

“On my honour, Bailiff,” said Thibault, “you are right; it is a sight to rejoice one’s heart.” And Thibault’s eyes began to shine like carbuncles.

And yet it was, as the Bailiff described it, quite an unpretentious little supper, but withal so appetising to look upon, that it was quite surprising. At one end of the table was a fine carp, boiled in vinegar and herbs, with the roe served on either side of it on a layer of parsley, dotted about with cut carrots. The opposite end was occupied by a boar-ham, mellow-flavoured, and deliciously reposing on a dish of spinach, which lay like a green islet surrounded by an ocean of gravy.

A delicate game-pie, made of two part ridges only, of which the heads appeared above the upper crust, as if ready to attack one another with their beaks, was placed in the middle of the table; while the intervening spaces were covered with side-dishes holding slices of Aries sausage, pieces of tunny-fish, swimming in beautiful green oil from Provence, anchovies sliced and arranged in all kinds of strange and fantastic patterns on a white and yellow bed of chopped eggs, and pats of butter that could only have been churned that very day. As accessories to these were two or three sorts of cheese, chosen from among those of which the chief quality is to provoke thirst, some Reims biscuits, of delightful crispness, and pears just fit to eat, showing that the master himself had taken the trouble to preserve them, and to turn them about on the store-room shelf.

Thibault was so taken up in the contemplation of this little amateur supper, that he scarcely heard the message which Perrine brought back from her mistress, who sent word that she had a sick-headache, and begged to make her excuses to her guest, with the hope that she might have the pleasure of entertaining him when he next came.

The little man gave visible signs of rejoicing on hearing his wife’s answer, breathed loudly and clapped his hands, exclaiming:

“She has a headache! she has a headache! Come along then, sit down! sit down!” And thereupon, besides the two bottles of old Macon, which had already been respectively placed within reach of the host and guest, as vin ordinaire, between the Hors-d’oeuvres and the dessert plates, he introduced the four other bottles which he had just brought up from the cellar.

Madame Magloire had, I think, acted not unwisely in refusing to sup with these stalwart champions of the table, for such was their hunger and thirst, that half the carp and the two bottles of wine disappeared without a word passing between them except such exclamations as:

“Good fish! isn’t it?”

“Capital!”

“Fine wine! isn’t it?”

“Excellent!”

The carp and the Macon being consumed, they passed on to the game pie and the Chambertin, and now their tongues began to be unloosed, especially the Bailiff’s.

By the time half the game pie, and the first bottle of Chambertin were finished, Thibault knew the history of Nepomucene Magloire; not a very complicated one, it must be confessed.

Monsieur Magloire was son to a church ornament manufacturer who had worked for the chapel belonging to his Highness the Duke of Orleans, the latter, in his religious zeal having a burning desire to obtain pictures by Albano and Titian for the sum of four to five thousand francs.

Chrysostom Magloire had placed his son Nepomucene Magloire, as head-cook with Louis’ son, his Highness the Duke of Orleans. The young man had, from infancy almost, manifested a decided taste for cooking; he had been especially attached to the Castle at Villers-Cotterets, and for thirty years presided over his Highness’s dinners, the latter introducing him to his friends as a thorough artist, and from time to time, sending for him to come up stairs to talk over culinary matters with Marshal Richelieu.

When fifty-five years of age, Magloire found himself so rounded in bulk, that it was only with some difficulty he could get through the narrow doors of the passages and offices. Fearing to be caught some day like the weasel of the fable, he asked permission to resign his post.

The Duke consented, not without regret, but with less regret than he would have felt at any other time, for he had just married Madame de Montesson, and it was only rarely now that he visited his castle at Villers-Cotterets.

His Highness had fine old-fashioned ideas as regards superannuated retainers. He, therefore, sent for Magloire, and asked him how much he had been able to save while in his service. Magloire replied that he was happily able to retire with a competence; the Prince, however, insisted upon knowing the exact amount of his little fortune, and Magloire confessed to an income of nine thousand livres.

“A man who has provided me with such a good table for thirty years,” said the Prince, “should have enough to live well upon himself for the remainder of his life.” And he made up the income to twelve thousand, so that Magloire might have a thousand livres a month to spend. Added to this, he allowed him to choose furniture for the whole of his house from his own old lumber-room; and thence came the damask curtains and gilt armchairs, which, although just a little bit faded and worn, had nevertheless preserved that appearance of grandeur which had made such an impression on Thibault.

By the time the whole of the first partridge was finished, and half the second bottle had been drunk, Thibault knew that Madame Magloire was the host’s fourth wife, a fact which seemed in his own eyes to add a good foot or two to his height.

He had also ascertained that he had married her not for her fortune, but for her beauty, having always had as great a predilection for pretty faces and beautiful statues, as for good wines and appetising victuals, and Monsieur Magloire further stated, with no sign of faltering, that, old as he was, if his wife were to die, he should have no fear in entering on a fifth marriage.

As he now passed from the Chambertin to the Hermitage, which he alternated with the Sillery, Monsieur Magloire began to speak of his wife’s qualities. She was not the personification of docility, no, quite the reverse; she was somewhat opposed to her husband’s admiration for the various wines of France, and did every thing she could, even using physical force, to prevent his too frequent visits to the cellar; while, for one who believed in living without ceremony, she on her part was too fond of dress, too much given to elaborate head-gears, English laces, and such like gewgaws, which women make part of their arsenal; she would gladly have turned the twelve hogsheads of wine, which formed the staple of her husband’s cellar, into lace for her arms, and ribands for her throat, if Monsieur Magloire had been the man to allow this metamorphosis. But, with this exception, there was not a virtue which Suzanne did not possess, and these virtues of hers, if the Bailiff was to be believed, were carried on so perfectly shaped a pair of legs, that, if by any misfortune she were to lose one, it would be quite impossible through out the district to find another that would match the leg that remained. The good man was like a regular whale, blowing out self-satisfaction from all his air-holes, as the former does sea-water. But even before all these hidden perfections of his wife had been revealed to him by the Bailiff, like a modern King Candaules ready to confide in a modern Gyges, her beauty had already made such a deep impression on the shoe-maker, that, as we have seen, he could do nothing but think of it in silence as he walked beside her, and since he had been at tale, he had continued to dream about it, listening to his host, eating the while of course, without answering, as Monsieur Magloire, delighted to have such an accommodating audience, poured forth his tales, linked one to another like a necklace of beads.

But the worthy Bailiff, having made a second excursion to the cellar, and this second excursion having produced, as the saying is, a little knot at the tip of his tongue, he began to be rather less appreciative of the rare quality which was required in his disciples by Pythagons. He, therefore, gave Thibault to understand that he had now said all that he wished to tell him concerning himself and his wife, and that it was Thibault’s turn to give him some information as regards his own circumstances, the amiable little man adding that wishing often to visit him, he wished to know more about him. Thibault felt that it was very necessary to disguise the truth; and accordingly gave himself out as a man living at ease in the country, on the revenues of two farms and of a hundred acres of land, situated near Vertefeuille.

There was, he continued, a splendid warren on these hundred acres, with a wonderful supply of red and fallow deer, boars, partridges, pheasants and hares, of which the bailiff should have some to taste. The bailiff was astonished and delighted. As we have seen, by the menu for his table, he was fond of venison, and he was carried away with joy at the thought of obtaining his game without having recourse to the poachers, and through the channel of this new friendship.

And now, the last drop of the seventh bottle having been scrupulously divided between the two glasses, they decided that it was time to stop.

The rosy champagne prime vintage of Ai, and the last bottle emptied had brought Nepomucene Magloire’s habitual good nature to the level of tender affection. He was charmed with his new friend, who tossed off his bottle in almost as good style as he did himself; he addressed him as his bosom friend, he embraced him, he made him promise that there should be a morrow to their pleasant entertainment; he stood a second time on tiptoe to give him a parting hug as he accompanied him to the door, which Thibault on his part, bending down, received with the best grace in the world.

The church clock of Erneville was striking midnight as the door closed behind the shoemaker. The fumes of the heady wine he had been drinking had begun to give him a feeling of oppression before leaving the house, but it was worse when he got into the open air. He staggered, overcome with giddiness, and went and leant with his back against a wall. What followed next was as vague and mysterious to him as the phantasmagoria of a dream. Above his head, about six or eight feet from the ground, was a window, which, as he moved to lean against the wall, had appeared to him to be lighted, although the light was shaded by double curtains. He had hardly taken up his position against the wall when he thought he heard it open. It was, he imagined, the worthy bailiff, unwilling to part with him without sending him a last farewell, and he tried to step forward so as to do honour to this gracious intention, but his attempt was unavailing. At first he thought he was stuck to the wall like a branch of ivy, but he was soon disabused of this idea. He felt a heavy weight planted first on the right shoulder and then on the left, which made his knees give way so that he slid down the wall as if to seat himself. This manoeuvre on Thibault’s part appeared to be just what the individual who was making use of him as a ladder wished him to

do, for we can no longer hide the fact that the weight so felt was that of a man. As Thibault made his forced genuflexion, the man was also lowered; “That’s right, I’Eveilli! that’s right!” he said, “So!” and with this last word, he jumped to the ground, while overhead was heard the sound of a window being shut.

Thibault had sense enough to understand two things: first, that he was mistaken for someone called L’Eveille, who was probably asleep somewhere about the premises; secondly, that his shoulders had just served some lover as a climbing ladder; both of which things caused Thibault an undefined sense of humiliation.

Accordingly, he seized hold mechanically of some floating piece of stuff which he took to be the lover’s cloak, and, with the persistency of a drunken man, continued to hang on to it.

“What are you doing that for, you scoundrel?” asked a voice, which did not seem altogether unfamiliar to the shoe-maker. “One would think you were afraid of losing me.”

“Most certainly I am afraid of losing you,” replied Thibault, “because I wish to know who it is has the impertinence to use my shoulders for a ladder.”

“Phew!” said the unknown, “it’s not you then, l’Eveille?”

“No, it is not,” replied Thibault.

“Well, whether it is you or not you, I thank you.”

“How, thank you? Ah! I dare say! thank you, indeed! You think the matter is going to rest like that, do you?”

“I had counted upon it being so, certainly.”

“Then you counted without your host.”

“Now, you blackguard, leave go of me! you are drunk!”

“Drunk! What do you mean? We only drank seven bottles between us, and the Bailiff had a good four to his share.”

“Leave go of me, you drunkard, do you hear!”

“Drunkard! you call me a drunkard, a drunkard for having drunk three bottles of wine!”

“I don’t call you a drunkard because you drank three bottles of wine, but because you let yourself get tipsy over those three unfortunate bottles.”

And, with a gesture of commiseration, and trying for the third time to release his cloak, the unknown continued:

“Now then, are you going to let go my cloak or not, you idiot?”

Thibault was at all times touchy as to the way people addressed him, but in his present state of mind his susceptibility amounted to extreme irritation.

“By the devil!” he exclaimed, “let me tell you, my fine sir, that the only idiot here is the man who gives insults in return for the services of which he has made use, and seeing that is so, I do not know what prevents me planting my fist in the middle of your face.”

This menace was scarcely out of his mouth, when, as instantly as a cannon goes off once the flame of the match has touched the powder, the blow with which Thibault had threatened his unknown adversary, came full against his own cheek.

“Take that, you beast” said the voice, which brought back to Thibault certain recollections in connection with the blow he received. “I am a good Jew, you see, and pay you back your money before weighing your coin.”

Thibault’s answer was a blow in the chest; it was well directed, and Thibault felt inwardly pleased with it himself. But it had no more effect on his antagonist than the fillip from a child’s finger would have on an oak tree. It was returned by a second blow of the fist which so far exceeded the former in the force with which it was delivered, that Thibault felt certain if the giant’s strength went on increasing in the same ratio, that a third of the kind would level him with the ground.

But the very violence of his blow brought disaster on Thibault’s unknown assailant. The latter had fallen on to one knee, and so doing, his hand, touching the ground, came in contact with a stone. Rising in fury to his feet again, with the stone in his hand, he flung it at his enemy’s head. The colossal figure uttered a sound like the bellowing of an ox, turned round on himself, and then, like an oak tree cut off by the roots, fell his whole length on the ground, and lay there in sensible.

Not knowing whether he had killed, or only wounded his adversary, Thibault took to his heels and fled, not even turning to look behind him.

…to be continued.

The Architecture of Memory: Eco, Calvino, Borges, and the Digital Archive

Last week, I pursued the general hype and went to our local theatre to see a contemporary Opera inspired by Umberto Eco’s Name of the Rose, one of my favourite books of all time. And though it was mostly inspired by the 1986 movie, it captured many intellectual layers of semiology and historical geekness Eco infused in his masterpiece. From a visual point of view, te Opera was stunning and, while I was sitting there basking in the theatricality of the scenes and the magical environment, it inspired me a reflection on what literature can teach us when it comes to managing knowledge through our digital archives. Maybe I need a vacation.

Anyways, bear with me, if you will. This is dedicated to all the CDE managers out there, and to everyone who agreed with my last piece.

1. Introduction1.1. Memory as Architecture: Mapping the InvisibleThere are places that exist only in our minds, yet feel more concrete than the rooms we wake up in. A hexagonal chamber filled with endless books. A city suspended between possibility and forgetting. A library protected by fire, code, or silence. Literature has long been obsessed with memory—not the tidy kind that fits on a flash drive, but the sprawling, contradictory, dreamlike variety that defies deletion. In the pages of Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, Umberto Eco whose Name of the Rose inspired this article—and their spiritual successors—memory takes architectural form: structured yet fluid, symbolic yet functional, sacred yet unstable.

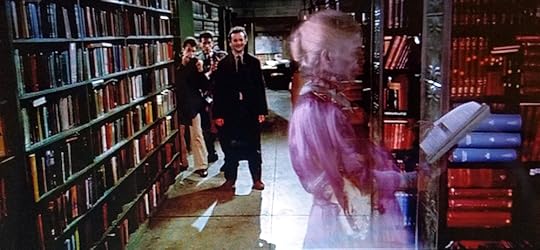

The depiction of the monastery’s library in the 1986 movie of The Name of the Rose doesn’t do it justice.What do those fictional architectures of memory reveal about our own very real, very digital attempts to remember everything? What happens when we take the infinite library of Borges and run it through an algorithm? Or ask Calvino’s Invisible Cities to become metadata categories? In other words: what can fiction teach our machines?

As we build data lakes and knowledge graphs, as we train AI models on the entire known internet and store backups in salt mines and lunar capsules, we might pause and ask: are we remembering wisely—or merely hoarding? Are we building temples of knowledge—or just very elegant labyrinths with no exits?

This is not an elegy for lost libraries (although a few might sneak in along the way). Nor is it a technical treatise. Rather, it is an invitation to use fantastic literature as it was meant to be: as a means of reflection to see our digital archives not as a database, but as a dreamscape. We’ll have Calvino’s poetic constraints conversing with cloud storage schemas, and Borges’ infinite permutations brushing shoulders with metadata taxonomies. This is what happens when I go to the theatre. Bear with me.

A shot from the fantastic modern opera by Francesco Filidei, staged at the Scala theatre last month.1.2. From Codex to Cloud: Why Fictional Libraries Still MatterIn a time when every byte of information risks becoming both permanent and meaningless, the imaginative archives of fiction become more than just metaphors—they become warnings, talismans, and perhaps even blueprints. We live amidst the illusion of total memory: every photograph backed up, every message archived, every document versioned into eternity. And yet, meaning dissolves faster than ever in the ever-growing swell of our digital hoards.

Enter the fictional library.

Umberto Eco’s Name of the Rose offers a vision of the archive as a theological labyrinth, where knowledge is deemed dangerous precisely because it is powerful. Knowledge has always been contested, and controlled through encoding. The library’s inner sanctum is both a prison and a puzzle—a reminder that curation is power, and that storage without access is merely containment. Today’s cloud architectures may lack the scent of old parchment, but they share the same double-edged seduction: they promise access, while quietly obscuring meaning through volume, structure, and complexity. Or through an undecodable naming convention.

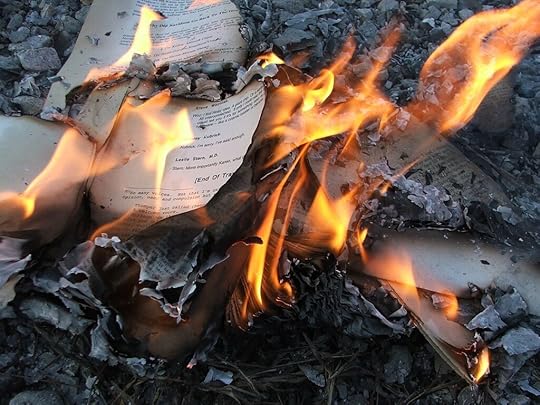

I won’t get into the topic of book censorship, as this isn’t the central theme here, but be reassured that I find it abhorrent beyond words, especially when it means to restrict access to knowledge to young people in search of their identity.

I won’t get into the topic of book censorship, as this isn’t the central theme here, but be reassured that I find it abhorrent beyond words, especially when it means to restrict access to knowledge to young people in search of their identity.Robin Sloan’s debut novel Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore brings this tension into the 21st century. His bookshelves hide a secret society obsessed with decoding a hidden message that may never exist. Digital tools—Google, OCR, data visualisation—become allies, but they never replace the aura of the archive. Sloan’s world suggests that even in the age of algorithms, the archive courts mystery. It’s not enough to know something is stored. We need to believe there is something worth finding.

On a side note, we recently explored this bias with a client. Sure you can develop a tool that crawls through all your past projects for information… but how do we make sure that it’ll find something relevant, verified and viable?

On a side note, we recently explored this bias with a client. Sure you can develop a tool that crawls through all your past projects for information… but how do we make sure that it’ll find something relevant, verified and viable?And then there is Carlos Ruiz Zafón, whose Cemetery of Forgotten Books gives us one of the most emotionally charged depictions of archival memory in modern fiction. In this hidden repository of forsaken volumes, each book is bound to a soul, a history, a secret. The library becomes a spiritual interface—a place where memory is not data, but destiny. How often do our cloud drives, with their folders named “Final_v3_REALLYFINAL”, achieve anything close to this? And all we wanted was a “unified source of truth”. That didn’t seem like asking much.

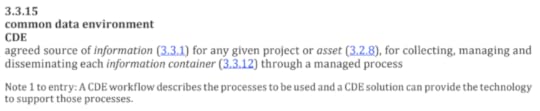

If you think that “universal source of truth” is the actual definition of the CDE in ISO 19650, you’re a victim of the Mandela Effect (see my previous article), as it’s not what it says.

If you think that “universal source of truth” is the actual definition of the CDE in ISO 19650, you’re a victim of the Mandela Effect (see my previous article), as it’s not what it says.Cloud archives are, in many ways, the shadow libraries of our age. They are modular, redundant, always accessible, yet strangely elusive. They promise immortality of information, but not intimacy with it. We back up not to remember, but to insure. We search not to understand, but to locate. They are structured not around narrative, but around retrievability, scalability, cost-per-gigabyte.

In contrast, fictional libraries challenge us to consider the quality of memory, not just its quantity. They ask: what if memory has shape? What if it has intent? What if forgetting—judicious, sacred forgetting—is as vital to knowledge as infinite recall? Books in these stories are not passive vessels. They seduce, betray, whisper, even as they burn. They are actors in the drama of knowledge. They remind us that the architecture of memory is not neutral: it directs us, confines us, even deceives us. A search engine may return every instance of a word, but it cannot explain why it matters.

To build better digital memory systems, we might need to look less at how much we store and more at how we choose. And for that, these fictional libraries may offer more wisdom than any technical whitepaper. They teach us that the archive is never just a place—it is a ritual, a relationship, a risk.

Welcome, then, to the architecture of memory. You’ll need no password, just a willingness to get a little lost.

2. Philosophical and Informational FoundationsLong before server farms blinked into existence, before hard drives and cloud backups, memory already had its architects. The Greeks and Romans rethors built palaces not of stone, but of thought—vast mental cathedrals populated by vivid images, placed along imagined corridors. This was the method of loci, the art of memory, the original cloud infrastructure suspended not in the sky but in the mind.

Sherlock did not invent the Mind Palace: he borrowed it from the anonymous Rhetorica ad Herennium, Cicero’s De Oratore, and Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria.2.1. Mnemosyne’s Architecture: From Memory Palaces to Metadata

Sherlock did not invent the Mind Palace: he borrowed it from the anonymous Rhetorica ad Herennium, Cicero’s De Oratore, and Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria.2.1. Mnemosyne’s Architecture: From Memory Palaces to MetadataIn Greek mythology, Mnemosyne, goddess of memory, was not merely a custodian of facts; she was the mother of the Muses. Memory, then, was not static—it was generative, the source of art, story, and song. Her architecture was fluid yet stable, an invisible scaffold on which the richness of human culture could be suspended. The memory palace technique was born within this cultural context, enriched by the Romans’ practical edge on politics, and formalised this principle. Thinkers like Cicero, Quintilian, and later medieval scholars described how a skilled practitioner could navigate through an imaginary building, each chamber holding a vivid, often surreal image linked to a concept or piece of information. The structure itself—the spatial organisation—was crucial. It provided retrieval hooks: a way for the mind to “walk” back through its own archive and find, not just data, but context, meaning, and associative richness.

In our own time, metadata plays a similar role. The “where” and “how” of information are almost as important as the information itself. Without tags, without relational structures, data floats unmoored, inaccessible. Metadata, like the mnemonic architecture of old, provides paths through chaos. It builds corridors where otherwise there would only be mist.

Yet there is a telling difference.

Where ancient memory palaces celebrated symbolic density, the metadata schemas of our age prefer minimalism. That’s the illuminists’ legacy, baby, and our ever-growing obsession for finding the perfect taxonomy, a way to classify stuff, One Metadatum to Rule Them All. A field labelled “Date Modified” or “Author” often lacks the imaginative punch of a flaming phoenix perched on a marble column, signalling the orator to recall the story of Icarus, but does it have to? We have gained precision but lost enchantment. The architecture of memory has become efficient to machines, but not necessarily memorable for people.

And herein lies a lesson: a machine-readable structure is not enough, and a retrieval system that forgets the texture of memory risks becoming nothing more than an index without a story. Codes need to be human-readable, and archive rules must stay within the human ability to comprehend and navigate them because they provide meaning within themselves.

Mnemosyne, goddess of memory and mother of the muses, painted by Richard Leighton2.2. Ars Memoriae and the Roots of Information Storage

Mnemosyne, goddess of memory and mother of the muses, painted by Richard Leighton2.2. Ars Memoriae and the Roots of Information StorageThe Ars Memoriae—the art of memory—was not just a set of mnemonic tricks; it was considered, in the classical and medieval mind, a foundational technology of thought itself. To know how to remember was to know how to think. The ordering of knowledge was not arbitrary; it was a spiritual exercise, a discipline of the mind.

In the libraries of the Middle Ages, knowledge was organised according to practical and theological needs, driven by function and religious utility. There was a strong medieval tendency to see the cosmos, knowledge, and architecture as interconnected and reflective of divine order, sure, but stuff was organised based on correspondences, not Dewey decimals. Finding one precise piece of information was as important as encouraging human curiosity to peruse by association. While this approach has fundamentally changed, make no mistake: to store knowledge is always to interpret it, to decide what is worth remembering, how it should be linked, and who should have access.

As Mario Carpo has always stressed in his foundational texts (I talked about them extensively, peruse the archive), modernity brings a dangerous inversion: where the old masters of memory sought compression through vividness—an entire story remembered by a single icon—modern systems sought expansion through redundancy as soon as technology allowed. Backup upon backup, copy upon copy, mirror upon mirror. We trust in storage, but not necessarily in retrieval—or understanding.

If you read one text on the topic, make sure it’s this.2.3. Redundancy, Noise, and Meaning in Systems

If you read one text on the topic, make sure it’s this.2.3. Redundancy, Noise, and Meaning in SystemsIf the ancients taught us about memory palaces, the moderns built transmission towers. With the 20th century came a new way of thinking about memory—not as a poetic structure for internal reflection, but as a problem of information transfer. In 1948, Claude Shannon, often called the father of information theory, published a seminal paper proposing that communication could be boiled down to binary signals, redundancy, and noise.

Claude Shannon was this guy.

Claude Shannon was this guy.Shannon’s genius lay in separating meaning from transmission. For the engineer, it mattered not what the message said, but whether it could survive distortion. Redundancy, once seen as a flaw or inefficiency, became an essential tool: a way of ensuring that a message arrived intact, even across chaotic channels. In Shannon’s world, duplication wasn’t waste—it was armour against entropy.

Now consider Jorge Luis Borges, writing just a few years earlier. In The Library of Babel—written in 1941, around the same years Shannon was developing his theories—Borges conjured a universe composed entirely of books, every possible permutation of letters across a fixed length. Within that infinity, every possible truth exists—alongside every lie, every mistake, every meaningless jumble of symbols. Meaning is swallowed by abundance. Redundancy, instead of protecting information, obliterates it.

Where Shannon saw redundancy as a way to guard against noise, Borges saw it as a source of existential despair. Too many copies, too many variations, too much noise—and the fragile island of meaning sinks beneath a tide of gibberish. The contrast is striking. In Shannon’s mathematical landscape, redundancy is an engineering solution. In Borges’ literary cosmos, redundancy is an ontological nightmare.

Jorge Luis Borges was this guy.

Jorge Luis Borges was this guy.And yet, both were grappling with the same essential problem we’re facing today in our own digital archives: how does information survive? How do we build systems—whether telegraphs or libraries or cloud archives—that protect the fragile signal against the inevitable decay of time, error, and misunderstanding?

Today’s digital archives embody both visions. Metadata tags, error-correcting codes, and blockchain ledgers all apply Shannon’s principles of resilient transmission. Meanwhile, the sheer volume of digital data—the endless backups, copies, revisions—threatens to recreate Borges’ infinite library, where the presence of everything ensures the retrieval of nothing.

In designing memory systems, we must balance these twin poles:

Redundancy as shield versus redundancy as suffocation.Storage as salvation of meaning versus storage as a pit of oblivion.Perhaps the perfect archive must be neither a sterile broadcast nor an endless labyrinth, but something else—a curated garden where meaning can survive without being drowned. The architect must ask not simply “Can I store this?”, but “Should I?”. And more daring still: “How will it live on, during the project?”

Don’t get me started on gardens: this piece will never end.3. The Construct of the Digital Archive

Don’t get me started on gardens: this piece will never end.3. The Construct of the Digital ArchiveIf the memory palace was a guided tour and the Library of Babel a blind wandering, the digital archive needs to support another activity: the autonomous search. Tagging and indexing are its navigational tools—the markers that help retrieve the right piece of information from an expanding sea of data.

Every time we label a file, add metadata to an image, or assign a keyword to a specification, we are not simply organising; we are shaping the pathways of discovery. Taxonomies, categories, and hierarchies are forms of storytelling in their own right, crafting routes that guide future users toward what they seek—or toward what we have anticipated they might seek.

Tagging is rarely neutral. Every keyword implies a perspective, a choice about how a piece of information fits into a broader structure of meaning. Is a document about “architecture” or “urbanism”? Should a photograph be categorised under “construction detail” or “construction flaw”? These decisions influence not only retrieval but also interpretation.

In fiction, Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore stages this beautifully: Sloan’s protagonist uses both human intuition and algorithmic power to uncover hidden patterns—not in the books’ contents, but in the way they are organised. In doing so, the novel reminds us that how we search often determines what we find, and that the architecture of discovery is as significant as the artefacts themselves.

[image error] Please read this.In our own systems, every search engine result, every database query, reflects a hidden narrative about what has been stored, indexed, and linked. If we didn’t define the system’s architecture with this in mind, thd structure and narrative is totally unconscious, like that of a chicken piling LEGO bricks with its beak. The archive is not a passive container; it is a constructed environment, where meaning emerges not just from content, but from connections.

This sure looks like a structure, but is it intentional?3.1. Curating vs. Hoarding: How Stories Shape Data

This sure looks like a structure, but is it intentional?3.1. Curating vs. Hoarding: How Stories Shape DataNot all who gather are curators. Some simply hoard.

In the digital archive, the line between collection and clutter grows perilously thin. The temptation to store everything—every draft, every redundant photo, every forgotten email chain—is fueled less by a desire for meaning than by a fear of loss or, worst, the need to get out of hypothetical, future trouble. Every “just in case” file saved, every “final_final_v2” document tucked away in a forgotten folder, is a small act of anxiety: a hedge against forgetting, a talisman against the impermanence of our digital existence.

I’m not a fan of Inside Out, but I am a fan of how their belief system is created through the meaning we give to memory, and the depiction of the panic attack as an avalanche of tucked-away memories is simply genius.

I’m not a fan of Inside Out, but I am a fan of how their belief system is created through the meaning we give to memory, and the depiction of the panic attack as an avalanche of tucked-away memories is simply genius.But accumulation without discernment leads to a slow suffocation of meaning. The more we gather indiscriminately, the more invisible each individual item becomes. Data piles up, thick and unstructured, until the archive becomes a graveyard—not of forgotten things, but of things that were never properly remembered in the first place.

Curation, by contrast, is an act of intentional storytelling. It is an editorial gesture, an active decision to shape memory, not merely to preserve it. To curate is to ask:

What matters here?What deserves to endure?What context does this memory need in order to be understood later?A curated archive says: This matters.

A hoarded archive begrudgingly mutters: Maybe something here will matter someday.

Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s The Shadow of the Wind captures this distinction vividly. In the Cemetery of Forgotten Books, entrance is not automatic. One must choose a single volume to “adopt,” to protect it from oblivion. Even in a library designed for loss, there is selection, stewardship, responsibility. Memory, in Zafón’s world, is not passive; it demands engagement. The books are not warehoused in bulk. They are given meaning by the fact that someone—reader, caretaker, future discoverer—cares enough to choose them.

In our digital systems, we too must learn to choose. And, ideally, not perish.

You know what to choose, if that’s the case.

You know what to choose, if that’s the case.We must resist the easy drift toward limitless accumulation and embrace the harder, slower work of storytelling through selection. Curation requires time, attention, and a willingness to say no. Not everything needs to be saved. Not every backup needs to be infinite.

Moreover, how we curate matters. Contextual metadata, careful categorization, meaningful tags, human-readable notes—these are the modern equivalent of illuminating a manuscript, adding a marginalia, carefully picking a Drop cap that drives home a message, or binding a codex with care. Without them, files may survive physically but die cognitively. Future readers (including ourselves) will find only shapeless noise where once there could have been living memory.

I know I said I wasn’t going to expand on this, but then again… the more I think about it, the more I feel gardening is a better metaphor than warehousing. The gardener does not try to grow everything at once. They prune, they weed, they plan for cycles of bloom and dormancy. In the same way, the storage portion of a Common Data Environment must be alive, evolving with its purpose and audience, allowing for both permanence and graceful forgetting.

Mary, Mary, quite contrary…

Mary, Mary, quite contrary…Curation is not an act of nostalgia—it is a commitment to future meaning. It recognises that memory is finite, not infinite, and that its value lies precisely in its limitation: in what is remembered instead of everything else. In the design of digital archives, as in the stewardship of project memory, the ultimate question is not how much we can store, but what stories we choose to tell with what we keep.

Add another aspect on top of this. We act as if our archives can hold an infinite amount of data, but is that actually true and what’s the environmental impact of this belief? While data centres currently account for about 1% of global energy use and contribute approximately 2–4% of global carbon emissions, projections suggest that their usage of global electricity could rise from 3% to 10% by 2030, driven by increasing demand from AI and machine learning workloads.

So, what different approach might we adopt?

3.2. The Archive as Game: Oulipo, Constraints, and DesignConstraints breed creativity. The Oulipo group—Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, or “Workshop for Potential Literature”—embraced this principle with almost mathematical fervor. Writers like Raymond Queneau, Georges Perec (see here), and Italo Calvino experimented with formal limits: novels written without the letter “e” (La Disparition), stories generated by algorithmic permutations, poems unfolding along combinatorial grids. Constraints, for the Oulipo, were not cages but engines. By setting boundaries—rules, limits, formulas—they unlocked new territories of expression that would otherwise remain hidden. Freedom was not the absence of limits; it was the richness found within them.

In the world of digital archives, this lesson is just as vital.

Without constraints, archives grow wild and unstructured, threatening to drown users in undifferentiated bulk. Every file saved without a schema, every dataset indexed without a taxonomy, every uncontrolled vocabulary breeds confusion. Discovery becomes harder, not easier, as options proliferate without guidance. And while we are listening to the courting songs of AI, promising to create flexible scaffolds of meaning around our digital mess, what are we prepared to lose when we relinquish curation? Have we really given it enough thought? Can we train a machine to do something we don’t actually understand?

I’m sure Libby can help me find the book I’m looking for, but can he advise me on searching for something I didn’t know I needed?

I’m sure Libby can help me find the book I’m looking for, but can he advise me on searching for something I didn’t know I needed?Constraints in archive design—through metadata standards, controlled vocabularies, access protocols, modular storage rules—turn accumulation into intelligible structure. They guide users along designed paths without scripting every move, and offer navigational scaffolding without dictating the journey’s meaning. That’s the work of an architect and a manager of a Common Data Environment. Not assigning reading vs writing permits in folders.

In this sense, Calvino’s Invisible Cities offers a profound model.

The novel’s intricate architecture—a precisely ordered series of dialogues, cities grouped and repeated across thematic axes—does not confine the reader’s imagination. Instead, it amplifies it. The strict formal structure creates resonances, echoes, and hidden symmetries that invite readers to participate, to notice patterns, to build their own internal maps of Marco Polo’s shifting cities, and to read the novel in a non-linear fashion, pursuing those patterns.

One of Karina Puente’s illustrations to Calvino’s Cities: Ipazia.

One of Karina Puente’s illustrations to Calvino’s Cities: Ipazia.An effective digital archive might work the same way.

Rather than presenting data as a flat inventory, it can be structured like a game board, a matrix of possibilities where users follow relational references, encounter unexpected juxtapositions, and assemble meaning through interaction. Constraints, far from being limitations, shape user experience and define the grammar of interaction. Faceted search, curated pathways, dynamically generated clusters of related materials—all these design choices echo Oulipian principles, turning the archive from a static warehouse into an active exploration, and it’s entirely within the possibility of our current technology. We’re just too busy renaming files to pursue it.

Moreover, constraints act as memory’s protectors. By deciding what types of data are admissible, how they must be described, and in what relationships they must stand, the manager preserves the possibility of future understanding. An archive without structure risks becoming, once again, Borges’ Library of Babel—vast, infinite, but ultimately unreadable.

Thus, the future of the Common Data Environment might demand a shift: from a container of information to a designed experience, a balance between rigidity and openness, order and imagination. The most enduring memory systems will not be those that store the most, but those that invite the richest and meaningful exploration.

4. Designing the Archive of the FutureNow, what do I mean when I say that the technology exists? Let’s take a closer look.

“I would like, if I may, to take you on a strange journey”4.1. The Archive Status. A.k.a. Can a Library Be Infinite and Useful?

“I would like, if I may, to take you on a strange journey”4.1. The Archive Status. A.k.a. Can a Library Be Infinite and Useful?The dream of the infinite library persists, and I won’t be the one to banish it from your imagination. It flickers in Borges’ Library of Babel, resurfaces in the boundless databases of Google, and echoes in every ambitious digital repository that promises to preserve everything. In theory, an infinite archive offers limitless discovery: every fact, every version, every forgotten trace made eternally retrievable. As we have seen, discovery doesn’t seem possible without structure. And infinity with structure is a paradox.

As Borges understood all too well, a library containing every book ever written—including every possible combination of letters—is not a paradise but a nightmare.

A useful archive, no matter how vast, must therefore impose limits of intelligibility. It must structure infinity into zones of relevance. It must prune, prioritize, and organize—not to diminish knowledge, but to make it reachable.

But I can’t decide to delete stuff.

I know, darling, I know.

Please don’t be scared: I might have solutions.

Please don’t be scared: I might have solutions.One possible compromise, that doesn’t address the environmental issue but at least tries to recuperate meaning for our Common Data Environment, is this: an infinite archive is possible only if it is also finite at the point of encounter, offering the right document at the right time to the right seeker. Otherwise, the user is left adrift, shipwrecked on the endless shores of possibility.

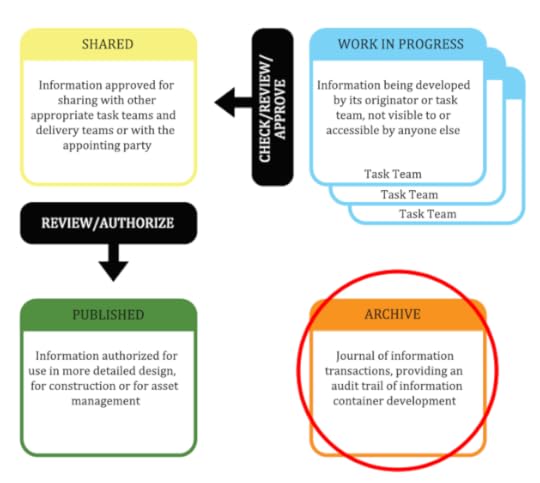

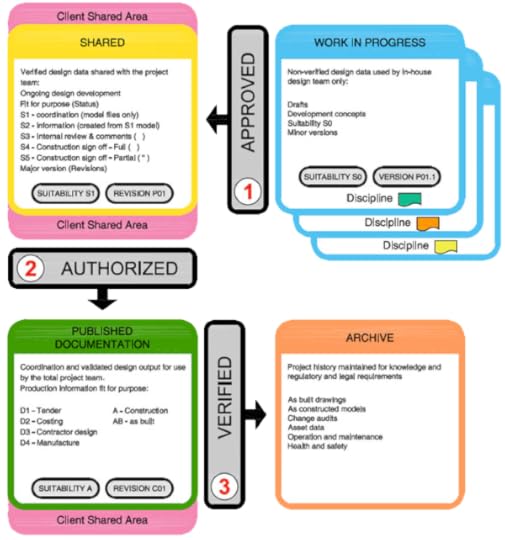

That’s why we have the Common Data Environment’s archive status, right? To keep out of the way whatever’s no longer relevant.

This little guy over here.

This little guy over here.And yet, the absence of arrows in that well-known scheme of the international norm speaks volumes: how do we get there? DO WE get there? And why? With whose clearances? Under which circumstances? An archive that’s really dynamic will not merely scale that section horizontally by adding more data or by keeping piling superseded versions upon superseded versions. It will scale vertically by adding layers of meaning, filters of interpretation, and maps of guidance to retrieve how we got to the current point in the project and—maybe—what went wrong. Usefulness is not the enemy of infinity; it is its steward.

4.2. The Classification Systems. A.k.a. From Dewey to Deep LearningClassification systems have always reflected philosophies of order. I speak at length about it at the beginning of pretty much every lesson on Levels of Development and Work Breakdown Structures, involving people like Raymond Lull, Pierre de la Ramée, Conrad Gessner and Paul Otlet (see here).

Melvil Dewey’s Decimal System, born in the 19th century, is one of those milestones that divided human knowledge into rigid, numbered categories—a structure that, despite its endurance, reveals a very particular worldview: hierarchical, Western-centric, and increasingly outdated.

Librarians everywhere, please don’t hate me. For everybody else, the Dewey Decimal System remains the most widely used library classification scheme globally, used in over 200,000 libraries in at least 135 countries, and I know it’s being continuously updated to better accommodate new fields and perspectives. I know you’re trying.

It’s never wise to upset a librarian

It’s never wise to upset a librarianToday’s information architects face a new challenge. The rise of deep learning and AI-driven retrieval threatens to make traditional categories obsolete and, as we have seen, that might not be a bad thing. In theory. Neural networks group information not by predefined taxonomies, but by fluid patterns of association. A photograph, a text snippet, and a drawing may cluster together not because they belong to the same “subject,” but because some latent vector hints at a shared essence.

Those systems, however, require designing, else the risk of delegating to the spontaneous definition of meaning inherent in neural networks. Also, designing systems isn’t enough: systems will have to be used by people. These new tools demand a new sensibility—a poetics of interface—that moves beyond rigid folders and static indexes. Interfaces must invite exploration, not just retrieval. They must allow users to connect across categories, to glimpse unexpected affinities. They must offer not just answers, but encounters with knowledge. Imagine, if you will, an archive where searching for “memory” brings you not only scientific papers, but also paintings, personal letters, city maps, and forgotten myths. Where meaning is discovered relationally, dynamically, through an interplay of forms. This isn’t any different than the concept of the Medieval library, if you’ve been paying attention.

Maybe not this one.Conclusion: Literary Templates for the Ethical Archive. Ak.a. What Fiction Teaches TechFantastic and sci-fi literature, far from being a relic, offers powerful templates for how we might design and govern our technological solutions.

In The Name of the Rose, Eco warns us that access is power, and that curating knowledge carries ethical stakes.

In Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, Sloan shows how digital tools can extend, but not replace, the thrill of human curiosity.

In The Shadow of the Wind, Zafón reminds us that archives are repositories not just of data, but of personal histories and emotional debts.

From these literary visions, we can extract guiding principles:

Curation matters as much as storage. Not everything needs to be saved; some things must be chosen.Context must be preserved. A document divorced from its origins is a memory without meaning.Discovery should remain an adventure. Archives must nurture curiosity, not just efficiency.Access must be equitable and ethical. Not all memories are harmless; not all knowledge should be stripped of its consequences.Fiction shows us that an archive is never neutral. It is a place where values are encoded into every organisational choice, every retrieval algorithm, every forgotten folder. How’s your Common Data Environment structured these days?