Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 16

February 17, 2025

#MerfolkMonday: The Water Snake

Another folk-tale translated by William Ralston Shedden-Ralston in his A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-lore (1887). It’s grouped in Chapter III, “Miscellaneous Impersonations”, together with “The Water King and Vasilissa the Wise” I gave you last week. The scholar who collected this one is of this one is A.A. Erlenwein, in a collection called Folk Tales Collected by Rural Teachers from 1863.

There was once an old woman who had a daughter; and her daughter went down to the pond one day to bathe with the other girls. They all stripped off their shifts, and went into the water. Then there came a snake out of the water, and glided on to the daughter’s shift. After a time the girls all came out, and began to put on their shifts, and the old woman’s daughter wanted to put on hers, but there was the snake lying on it. She tried to drive him away, but there he stuck and would not move. Then the snake said:

“If you’ll marry me, I’ll give you back your shift.”

Now she wasn’t at all inclined to marry him, but the other girls said:

“As if it were possible for you to be married to him! Say you will!” So she said, “Very well, I will.” Then the snake glided off from the shift, and went straight into the water. The girl dressed and went home. And as soon as she got there, she said to her mother,

“Mammie, mammie, thus and thus, a snake got upon my shift, and says he, ‘Marry me or I won’t let you have your shift;’ and I said, ‘I will.’”

“What nonsense are you talking, you little fool! as if one could marry a snake!”

And so they remained just as they were, and forgot all about the matter.

A week passed by, and one day they saw ever so many snakes, a huge troop of them, wriggling up to their cottage. “Ah, mammie, save me, save me!” cried the girl, and her mother slammed the door and barred the entrance as quickly as possible. The snakes would have rushed in at the door, but the door was shut; they would have rushed into the passage, but the passage was closed. Then in a moment they rolled themselves into a ball, flung themselves at the window, smashed it to pieces, and glided in a body into the room. The girl got upon the stove, but they followed her, pulled her down, and bore her out of the room and out of doors. Her mother accompanied her, crying like anything.

They took the girl down to the pond, and dived right into the water with her. And there they all turned into men and women. The mother remained for some time on the dike, wailed a little, and then went home.

Three years went by. The girl lived down there, and had two children, a son and a daughter. Now she often entreated her husband to let her go to see her mother. So at last one day he took her up to the surface of the water, and brought her ashore. But she asked him before leaving him,

“What am I to call out when I want you?”

“Call out to me, ‘Osip, [Joseph] Osip, come here!’ and I will come,” he replied.

Then he dived under water again, and she went to her mother’s, carrying her little girl on one arm, and leading her boy by the hand. Out came her mother to meet her—was so delighted to see her!

“Good day, mother!” said the daughter.

“Have you been doing well while you were living down there?” asked her mother.

“Very well indeed, mother. My life there is better than yours here.”

They sat down for a bit and chatted. Her mother got dinner ready for her, and she dined.

“What’s your husband’s name?” asked her mother.

“Osip,” she replied.

“And how are you to get home?”

“I shall go to the dike, and call out, ‘Osip, Osip, come here!’ and he’ll come.”

“Lie down, daughter, and rest a bit,” said the mother.

So the daughter lay down and went to sleep. The mother immediately took an axe and sharpened it, and went down to the dike with it. And when she came to the dike, she began calling out,

“Osip, Osip, come here!”

No sooner had Osip shown his head than the old woman lifted her axe and chopped it off. And the water in the pond became dark with blood.

The old woman went home. And when she got home her daughter awoke.

“Ah! mother,” says she, “I’m getting tired of being here; I’ll go home.”

“Do sleep here to-night, daughter; perhaps you won’t have another chance of being with me.”

So the daughter stayed and spent the night there. In the morning she got up and her mother got breakfast ready for her; she breakfasted, and then she said good-bye to her mother and went away, carrying her little girl in her arms, while her boy followed behind her. She came to the dike, and called out:

“Osip, Osip, come here!”

She called and called, but he did not come.

Then she looked into the water, and there she saw a head floating about. Then she guessed what had happened.

“Alas! my mother has killed him!” she cried.

There on the bank she wept and wailed. And then to her girl she cried:

“Fly about as a wren, henceforth and evermore!”

And to her boy she cried:

“Fly about as a nightingale, my boy, henceforth and evermore!”

“But I,” she said, “will fly about as a cuckoo, crying ‘Cuckoo!’ henceforth and evermore!”

February 15, 2025

Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasyev, “The Soldier and the Vampire”

Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasyev (1826–1871) was a folklorist and ethnographer who collected nearly 600 East Slavic and Russian fairy tales between 1855 and 1867. His collection is considered one of the largest folklore collections worldwide and earned him a reputation as the Russian counterpart to the Brothers Grimm. This tale, known as “The Fiend” or “The Vampire”, is a number 363 in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as it deals with the theme of the Corpse-Eater.

The version here provided comes from an English translation by one William Ralston Shedden-Ralston of the British Museum, a corresponding member of the Imperial Geographical Society of Russia, who also compiled collections called The Songs of the Russian People and Krilof and his Fables. The collection is dedicated to Alexander Afanasyev, and it’s called A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-lore, and it was published in 1887. I already gave you “The Fiend”. This tale comes near the end of the book.

This time, I also included Shedden-Ralston’s commentary.

A certain soldier was allowed to go home on furlough. Well, he walked and walked, and after a time he began to draw near to his native village. Not far off from that village lived a miller in his mill. In old times the Soldier had been very intimate with him: why shouldn’t he go and see his friend? He went. The Miller received him cordially, and at once brought out liquor; and the two began drinking, and chattering about their ways and doings. All this took place towards nightfall, and the Soldier stopped so long at the Miller’s that it grew quite dark.

When he proposed to start for his village, his host exclaimed:

“Spend the night here, trooper! It’s very late now, and perhaps you might run into mischief.”

“How so?”

“God is punishing us! A terrible warlock has died among us, and by night he rises from his grave, wanders through the village, and does such things as bring fear upon the very boldest! How could even you help being afraid of him?”

“Not a bit of it! A soldier is a man who belongs to the crown, and ‘crown property cannot be drowned in water nor burnt in fire.’ I’ll be off: I’m tremendously anxious to see my people as soon as possible.”

Off he set. His road lay in front of a graveyard. On one of the graves he saw a great fire blazing. “What’s that?” thinks he. “Let’s have a look.” When he drew near, he saw that the Warlock was sitting by the fire, sewing boots.

“Hail, brother!” calls out the Soldier.

The Warlock looked up and said:

“What have you come here for?”

“Why, I wanted to see what you’re doing.”

The Warlock threw his work aside and invited the Soldier to a wedding.

“Come along, brother,” says he, “let’s enjoy ourselves. There’s a wedding going on in the village.”

“Come along!” says the Soldier.

They came to where the wedding was; there they were given drink, and treated with the utmost hospitality. The Warlock drank and drank, revelled and revelled, and then grew angry. He chased all the guests and relatives out of the house, threw the wedded pair into a slumber, took out two phials and an awl, pierced the hands of the bride and bridegroom with the awl, and began drawing off their blood. Having done this, he said to the Soldier:

“Now let’s be off.”

Well, they went off. On the way the Soldier said:

“Tell me; why did you draw off their blood in those phials?”

“Why, in order that the bride and bridegroom might die. To-morrow morning no one will be able to wake them. I alone know how to bring them back to life.”

“How’s that managed?”

“The bride and bridegroom must have cuts made in their heels, and some of their own blood must then be poured back into those wounds. I’ve got the bridegroom’s blood stowed away in my right-hand pocket, and the bride’s in my left.”

The Soldier listened to this without letting a single word escape him. Then the Warlock began boasting again.

“Whatever I wish,” says he, “that I can do!”

“I suppose it’s quite impossible to get the better of you?” says the Soldier.

“Why impossible? If any one were to make a pyre of aspen boughs, a hundred loads of them, and were to burn me on that pyre, then he’d be able to get the better of me. Only he’d have to look out sharp in burning me; for snakes and worms and different kinds of reptiles would creep out of my inside, and crows and magpies and jackdaws would come flying up. All these must be caught and flung on the pyre. If so much as a single maggot were to escape, then there’d be no help for it; in that maggot I should slip away!”

The Soldier listened to all this and did not forget it. He and the Warlock talked and talked, and at last they arrived at the grave.

“Well, brother,” said the Warlock, “now I’ll tear you to pieces. Otherwise you’d be telling all this.”

“What are you talking about? Don’t you deceive yourself; I serve God and the Emperor.”

The Warlock gnashed his teeth, howled aloud, and sprang at the Soldier—who drew his sword and began laying about him with sweeping blows. They struggled and struggled; the Soldier was all but at the end of his strength. “Ah!” thinks he, “I’m a lost man—and all for nothing!” Suddenly the cocks began to crow. The Warlock fell lifeless to the ground.

The Soldier took the phials of blood out of the Warlock’s pockets, and went on to the house of his own people. When he had got there, and had exchanged greetings with his relatives, they said:

“Did you see any disturbance, Soldier?”

“No, I saw none.”

“There now! Why we’ve a terrible piece of work going on in the village. A Warlock has taken to haunting it!”

After talking awhile, they lay down to sleep. Next morning the Soldier awoke, and began asking:

“I’m told you’ve got a wedding going on somewhere here?”

“There was a wedding in the house of a rich moujik,” replied his relatives, “but the bride and bridegroom have died this very night—what from, nobody knows.”

“Where does this moujik live?”

They showed him the house. Thither he went without speaking a word. When he got there, he found the whole family in tears.

“What are you mourning about?” says he.

“Such and such is the state of things, Soldier,” say they.

“I can bring your young people to life again. What will you give me if I do?”

“Take what you like, even were it half of what we’ve got!”

The Soldier did as the Warlock had instructed him, and brought the young people back to life. Instead of weeping there began to be happiness and rejoicing; the Soldier was hospitably treated and well rewarded. Then—left about, face! off he marched to the Starosta, and told him to call the peasants together and to get ready a hundred loads of aspen wood. Well, they took the wood into the graveyard, dragged the Warlock out of his grave, placed him on the pyre, and set it alight—the people all standing round in a circle with brooms, shovels, and fire-irons. The pyre became wrapped in flames, the Warlock began to burn. His corpse burst, and out of it crept snakes, worms, and all sorts of reptiles, and up came flying crows, magpies, and jackdaws. The peasants knocked them down and flung them into the fire, not allowing so much as a single maggot to creep away! And so the Warlock was thoroughly consumed, and the Soldier collected his ashes and strewed them to the winds. From that time forth there was peace in the village.

The Soldier received the thanks of the whole community. He stayed at home some time, enjoying himself thoroughly. Then he went back to the Tsar’s service with money in his pocket. When he had served his time, he retired from the army, and began to live at his ease.

The stories of this class are very numerous, all of them based on the same belief—that in certain cases the dead, in a material shape, leave their graves in order to destroy and prey upon the living. This belief is not peculiar to the Slavonians but it is one of the characteristic features of their spiritual creed. Among races which burn their dead, remarks Hertz in his exhaustive treatise on the Werwolf (p. 126), little is known of regular “corpse-spectres.” Only vague apparitions, dream-like phantoms, are supposed, as a general rule, to issue from graves in which nothing more substantial than ashes has been laid. But where it is customary to lay the dead body in the ground, “a peculiar half-life” becomes attributed to it by popular fancy, and by some races it is supposed to be actuated at intervals by murderous impulses. In the East these are generally attributed to the fact of its being possessed by an evil spirit, but in some parts of Europe no such explanation of its conduct is given, though it may often be implied. “The belief in vampires is the specific Slavonian form of the universal belief in spectres (Gespenster),” says Hertz, and certainly vampirism has always made those lands peculiarly its own which are or have been tenanted or greatly influenced by Slavonians.

But animated corpses often play an important part in the traditions of other countries. Among the Scandinavians and especially in Iceland, were they the cause of many fears, though they were not supposed to be impelled by a thirst for blood so much as by other carnal appetites, or by a kind of local malignity. In Germany tales of horror similar to the Icelandic are by no means unknown, but the majority of them are to be found in districts which were once wholly Lettic or Slavonic, though they are now reckoned as Teutonic, such as East Prussia, or Pomerania, or Lusatia. But it is among the races which are Slavonic by tongue as well as by descent, that the genuine vampire tales flourish most luxuriantly: in Russia, in Poland, and in Servia—among the Czekhs of Bohemia, and the Slovaks of Hungary, and the numerous other subdivisions of the Slavonic family which are included within the heterogeneous empire of Austria. Among the Albanians and Modern Greeks they have taken firm root, but on those peoples a strong Slavonic influence has been brought to bear. Even Prof. Bernhard Schmidt, although an uncompromising opponent of Fallmerayer’s doctrines with regard to the Slavonic origin of the present inhabitants of Greece, allows that the Greeks, as they borrowed from the Slavonians a name for the Vampire, may have received from them also certain views and customs with respect to it. Beyond this he will not go, and he quotes a number of passages from Hellenic writers to prove that in ancient Greece spectres were frequently represented as delighting in blood, and sometimes as exercising a power to destroy. Nor will he admit that any very great stress ought to be laid upon the fact that the Vampire is generally called in Greece by a name of Slavonic extraction; for in the islands, which were, he says, little if at all affected by Slavonic influences, the Vampire bears a thoroughly Hellenic designation. But the thirst for blood attributed by Homer to his shadowy ghosts seems to have been of a different nature from that evinced by the material Vampire of modern days, nor does that ghastly revenant seem by any means fully to correspond to such ghostly destroyers as the spirit of Gello, or the spectres of Medea’s slaughtered children. It is not only in the Vampire, however, that we find a point of close contact between the popular beliefs of the New-Greeks and the Slavonians. Prof. Bernhard Schmidt’s excellent work is full of examples which prove how intimately they are connected.

The districts of the Russian Empire in which a belief in vampires mostly prevails are White Russia and the Ukraine. But the ghastly blood-sucker, the Upir, whose name has become naturalized in so many alien lands under forms resembling our “Vampire,” disturbs the peasant-mind in many other parts of Russia, though not perhaps with the same intense fear which it spreads among the inhabitants of the above-named districts, or of some other Slavonic lands. The numerous traditions which have gathered around the original idea vary to some extent according to their locality, but they are never radically inconsistent.

Some of the details are curious. The Little-Russians hold that if a vampire’s hands have grown numb from remaining long crossed in the grave, he makes use of his teeth, which are like steel. When he has gnawed his way with these through all obstacles, he first destroys the babes he finds in a house, and then the older inmates. If fine salt be scattered on the floor of a room, the vampire’s footsteps may be traced to his grave, in which he will be found resting with rosy cheek and gory mouth.

The Kashoubes say that when a Vieszcy, as they call the Vampire, wakes from his sleep within the grave, he begins to gnaw his hands and feet; and as he gnaws, one after another, first his relations, then his other neighbors, sicken and die. When he has finished his own store of flesh, he rises at midnight and destroys cattle, or climbs a belfry and sounds the bell. All who hear the ill-omened tones will soon die. But generally he sucks the blood of sleepers. Those on whom he has operated will be found next morning dead, with a very small wound on the left side of the breast, exactly over the heart. The Lusatian Wends hold that when a corpse chews its shroud or sucks its own breast, all its kin will soon follow it to the grave. The Wallachians say that a murony—a sort of cross between a werwolf and a vampire, connected by name with our nightmare—can take the form of a dog, a cat, or a toad, and also of any blood-sucking insect. When he is exhumed, he is found to have long nails of recent growth on his hands and feet, and blood is streaming from his eyes, ears, nose and mouth.

The Russian stories give a very clear account of the operation performed by the vampire on his victims. Thus, one night, a peasant is conducted by a stranger into a house where lie two sleepers, an old man and a youth. “The stranger takes a pail, places it near the youth, and strikes him on the back; immediately the back opens, and forth flows rosy blood. The stranger fills the pail full, and drinks it dry. Then he fills another pail with blood from the old man, slakes his brutal thirst, and says to the peasant, ‘It begins to grow light! let us go back to my dwelling.’”

Many skazkas also contain, as we have already seen, very clear directions how to deprive a vampire of his baleful power. According to them, as well as to their parallels elsewhere, a stake must be driven through the murderous corpse. In Russia an aspen stake is selected for that purpose, but in some places one made of thorn is preferred. But a Bohemian vampire, when staked in this manner in the year 1337, says Mannhardt, merely exclaimed that the stick would be very useful for keeping off dogs; and a strigon (or Istrian vampire) who was transfixed with a sharp thorn cudgel near Laibach, in 1672, pulled it out of his body and flung it back contemptuously. The only certain methods of destroying a vampire appear to be either to consume him by fire, or to chop off his head with a grave-digger’s shovel. The Wends say that if a vampire is hit over the back of the head with an implement of that kind, he will squeal like a pig.

The origin of the Vampire is hidden in obscurity. In modern times it has generally been a wizard, or a witch, or a suicide, or a person who has come to a violent end, or who has been cursed by the Church or by his parents, who takes such an unpleasant means of recalling himself to the memory of his surviving relatives and acquaintances. But even the most honorable dead may become vampires by accident. He whom a vampire has slain is supposed, in some countries, himself to become a vampire. The leaping of a cat or some other animal across a corpse, even the flight of a bird above it, may turn the innocent defunct into a ravenous demon. Sometimes, moreover, a man is destined from his birth to be a vampire, being the offspring of some unholy union. In some instances the Evil One himself is the father of such a doomed victim, in others a temporarily animated corpse. But whatever may be the cause of a corpse’s “vampirism,” it is generally agreed that it will give its neighbors no rest until they have at least transfixed it. What is very remarkable about the operation is, that the stake must be driven through the vampire’s body by a single blow. A second would restore it to life. This idea accounts for the otherwise unexplained fact that the heroes of folk-tales are frequently warned that they must on no account be tempted into striking their magic foes more than one stroke. Whatever voices may cry aloud “Strike again!” they must remain contented with a single blow.

February 13, 2025

Among the Gnomes

Chapter 4

While I was sleeping I experienced a horrible dream. The jumping-jack before me assumed the features of a baboon, having a great resemblance to Professor Cracker, and besides this there were two grotesque figures standing at the foot of the pole. One was wooden nut-cracker with goggle eyes, a long nose and protruding chin, the very image of Jeremiah Stiffbone; and the other a curiously shaped whisky-jug of stoneware, having the form and features of Mr Scalawag; and while the monkey was moving up and down on the pole, the nut-cracker and the whisky-jug danced, and all three sang the following song:

Huzza and hey-day! Up and down we go;

There being nothing that we do not know.

We prove that black is white and white is black,

And all the world admires the jumping-jack.

And as we jump go jumping all the rest;

Who jumps the highest knows his business best.

Forward and backward on the beaten track:

There’s nothing greater than a jumping-jack.

And to our stick we cling from first to last;

Who asks for more is only a fantast.

Thus up and down we go, upward and back:

This is the glory of a jumping-jack.

After they finished singing, the nut-cracker sniffed the air with his nose and turned his goggle eyes in the direction where I was hidden, after which his jaws began to move, and he said:

“I am smelling human flesh. There is some one present.”

To this the whisky-jug replied, while grinning from ear to ear:

“Who knows but it may be Mr Schneider, or his ghost.”

“Mr Schneider has no ghost,” said the baboon. “If we were to find one, we would have to destroy it immediately, to save the reputation of science.”

“I am quite sure that something of that kind is hidden somewhere,” replied the nut-cracker, and turning to the baboon, he asked: “Do you see anything?”

“Seeing is deceptive,” answered the baboon, “but we will see whether we cannot reason it out. Wait till I come down.”

So saying, the monkey stopped his motions, and to my horror I saw him unfastening his hands from the crossbar. Climbing down the yellow stick, he joined the whisky-jug and the nut-cracker, and all three searched the place and almost stumbled over me, but they did not see me.

“There is nothing,” said the baboon. “However, there can be no doubt that Schneider is dead, and the only thing to be regretted about it is that he did not die in the interest of science. If we had known that he was going to die anyhow, we might have subjected him to certain experiments.”

Strange to say, during this dream I had no thought of being a Mulligan; but my individuality was changed back to Mr Schneider. When I awoke Schneider was gone, and I was once more Mulligan.

“De mortuis nil nisi bene!” drawled out the nut-cracker. “But if Schneider had died in the interest of science, it would have been the first useful thing he ever did.” So saying, the nut-cracker clapped his jaws.

The whisky-jug blinked with his little eyes and added, “He meant well, but——”

I knew what he was going to say, and this made me very angry. I therefore jumped at him and gave him a box on the ear; but my fist went quite through his head, and it had no other effect upon him than stopping his sentence. He did not seem to notice it; but I now knew that I had died and become a spirit. I also saw that I could take possession of people and use their organs of speech, and as the nut-cracker was nearest to me, I went inside of him and caused him to exclaim:—

“I will show you whether or not I am a well-meaning fool! Confound you and your science! I have been among the gnomes and know that they exist! but you are the blind fools who cannot see anything because you are too stupid to open your eyes.”

“Brother Stiffbone has become insane,” said the baboon; “let us tie him before he does us any injury.”

Thereupon the baboon and the whisky-jug went for me while I was in the nut-cracker’s body, and I went in that shape for them. I snapped at the baboon’s ear and gave him a black eye, and I tore out a handful of hair from the head of the whisky-jug, who in his turn broke my—that is to say, the nut-cracker’s nose. At last they got the best of me; because the wooden limbs of the nut-cracker were so stiff and I could not move them quickly enough. We fell down, and the baboon was kneeling upon my breast when I awoke.

Once more I was Mr Mulligan. I opened my eyes and found myself in inky darkness. The first thing I did was to feel my nose to see whether it was broken. The nose was all right, and its solidity convinced me that I was no ghost, and my adventure with the nut-cracker’s body, however real it seemed, had been only a dream. I groped about for the purpose of finding the jumping-jack, but it was gone; neither did I regret its absence, for with the sight of it all my affection for it had departed, and I could not understand how I could have been so foolish as to permit myself to be attracted by it. My desire for the purple monkey had left me; but my love for the princess returned. I yearned for her presence and called her name; but no answer came; there was nothing around me but darkness and solitude.

Ever since that event I have often asked myself, Why do we hate to be for a long time alone? The only answer I could find is, that when we are alone with ourselves, the company of our self is not sufficiently satisfactory and agreeable to us. Perhaps we do not sufficiently know that self to fully enjoy its presence. Perhaps we do not know that self at all, and then of course we are in company with something we do not know, which means in company with nothing, and to enjoy the presence of nothing is to have no enjoyment at all.

I confess that I never realised my own nothingness so much as on that occasion. The old doubts returned again. I did not know whether I was living or whether something which imagined itself to be “I” seemed to live, and if that which only seemed to be myself was to be vivisected, why should I trouble myself about it, as the vivisection of something unknown to me did not concern me at all, unless I voluntarily chose to take any interest in it? But how could I think of making any choice at all if that “I” was something unknown? I instinctively refused to recognise as myself that personality which was governed by the spell of a jumping-jack, and I spoke to myself as if I were another person.

“Well, Mulligan!” I said, “how could you be such an idiot as to submit yourself to the power of a baboon! Really, I doubt whether you are a man. Pshaw! the gnomes are right. You are a monkey yourself, and even inferior to a monkey, because the baboon was your master. A nice lord of creation you are, being controlled by the creation of your own foolish fancy. A lord of creation, indeed! One who cannot even resist the attraction of a jumping-jack!”

Thus I went on moralising, and wondered what my real Ego was, and whether it had anything at all to do with what seemed to be myself. I wished to know whether I—that is to say, my real self—was; for what purpose I was in the world, and where I had been before I entered the world, and what that was which caused me to be born, and whether I would be born again after I—that is to say, my body—had been dissected. Alas, for all these questions Cracker’s science had no answer to give, and I envied the gnomes who had the ability to dissolve and condense into bodies at will.

The darkness was very oppressive, and I wished that I could be self-luminous like a gnome, and not be dependent upon an external light for the purpose of seeing. I wondered whether, perhaps, after the dissection of my body, my spirit would have a light of its own, or whether Bimbam was right when he pronounced the suggestive word, “Empty!” Then something, of which I do not know what it was, made me think that the worst thing anybody could possibly do was to doubt or deny the presence of a spiritual light within himself, and while I studied as to what may be that which made me think so, I came to the conclusion that it was my own spirit reminding me of its presence, and this was a more convincing proof to me that I actually had a spirit than all the arguments offered to the contrary by Professor Cracker and his ilk.

With this conviction a great deal of calmness and satisfaction came over me. At the same time the darkness grew less in intensity; a silvery mist, tinged with blue, arose like the dawn that precedes the rising sun; the light grew stronger and condensed in a luminous ball, and the next instant the princess stood before me.

“Dearest Adalga!” I said, “where have you been so long, and why did you leave me alone in this horrible darkness?”

To this the princess answered, “Truth never departs, but error always attracts us. Never for an instant have I deserted you; I was with you and around you all the time, but you kept your eyes closed and refused to see.”

“On the contrary,” I replied, “I strained my eyes to look through the darkness, but there was nothing.”

“You strained your eyes,” answered the princess, “for the purpose of seeing my form, which was not formed, and which could not be seen; but you made no effort to see that which is without form, but which may be seen with the inner eye. Know, my beloved, that when you see my form you do not see me, and when you do not see my form you may see me in truth.”

“This,” I said, “is contrary to all the doctrines of our science, which teaches that we can see nothing whatever unless it has a shape of some kind.”

“The eye of science sees only the outward form,” answered Adalga; “but the eye of wisdom sees the reality itself.”

“I understand,” I replied. “I have learned a lesson, and henceforth the delusion caused by forms shall have no more power over me. But tell me, dear, is the hour of vivisection approaching? Is there no way for escape?”

“Alas, no!” sighed the princess. “There is a jumping-jack at every door.”

A thrill of horror swept through me when I heard these words, and made me tremble. A moment before I had called myself a fool for being afraid of a jumping-jack, and now at the very mention of such a toy the old terror came back. I knew that I could not escape, because I would not dare to face a jumping-jack again. I would be sure to succumb to its influence.

“But,” continued Adalga, “why should you be afraid of being dissected? Can you not create for yourself a new body again?”

“Nonsense!” I cried. “I am not a creator.”

“But, sure enough,” answered the princess, “you have a creative spirit in you. Oh, my dear Mulligan, why will you remain incognito among us? Why do you continue to be dark? Why will you disguise yourself before me? Is it that I am not worthy to behold your true light, or that my eyes would be dazzled by its splendour? Lord of my heart, unveil yourself to me! Show yourself to me in your own essence!”

“Dearest princess!” I replied, “I do not know what you are talking about. I am not luminous, and I never saw a luminous man. In our country nobody has a light of his own.”

“Alas!” said the princess, “what a fearful fate it must be to have no light, and to live in a country of perpetual darkness.”

To this I replied—

“This is not so. Nobody in our country needs a light of his own, because we have one great luminary, called the sun, right over our head, and the light of that sun illuminates our world.”

“And can everybody see that sun?” asked the princess.

“Of course,” I said. “Everybody, unless he is as blind as a bat.”

When I had spoken these words, the princess threw her arms around my neck, and whispered to me—

“Dearest Mulligan! I have a favour to ask you. Please fetch me the sun!”

“This is quite impossible,” I said, “for although we all live in the light of the sun, nevertheless we cannot approach the sun, nor put him into our pockets.”

But the princess was not satisfied with that answer. “Surely,” she exclaimed, “you told me that the sun was right above your heads. You ought not to refuse me the first kindness I ever asked of you. I implore you to bring me the sun. I will not be contented unless I have it.”

I became alarmed. “This is a foolish request, madame,” I said. “If somebody, or anybody, could claim the sun as his own, and carry it away, there would be little chance for anyone else to enjoy it. The Government would monopolise it, and put a tax upon the use of his light; the doctors would dissect him to see of what material he is made; and there are lots of amorous fools who would not hesitate a moment to make him explode, merely for the purpose of amusing their sweethearts.”

But it was of no use to argue such a thing with a being unacquainted with the first rules of logic, and the princess went on with tears and sobs to beg me to fetch her the sun. I tried my best to explain to her the absurdity of the request, but she would not listen; and, weeping bitterly, she cried—

“O Mulligan, you do not love me! Is this your gratitude for bestowing my affection upon you?”

I felt very miserable, and began to look upon myself as the most ungrateful wretch, and to appease her I promised that I would try to do all I could.

At this moment a blast of trumpets and the tinkling of bells announced the arrival of the king. He was accompanied by the queen and her suite, and with them came all the nobility, the ministers, officers, and also the whole of the medical faculty, together with the head executioner and his assistants. The queen was a little fat woman, and rather homely. Upon her head shone a great emerald, throwing a soft green light around her. She was accompanied by her maids of honour, all of whom appeared in a green colour.

I made my bow to the queen, who, after looking at me through the spiritoscope, turned to the king and said—

“Is this the green hobgoblin who has the impudence of claiming that he is a man-spirit?”

“Yes,” answered the king; “only, as you will observe, he is not green, but red.”

“Your majesty is pleased to jest,” replied the queen. “Everybody sees that he is green.”

“He is red,” said the king sternly, being evidently annoyed by her contradiction.

“Let him be red then, if you must have it so,” answered the queen, while her voice indicated vexation; “but he is green for all that.”

“Well, I declare!” exclaimed Bimbam I., growing still more red. “I never saw a woman in my life that did not love to contradict. I say he is red, and I will leave it to Cravatu to decide.”

Cravatu stepped forward, letting his yellow light fall directly upon me, and after scanning me very carefully, he said: “I beg pardon, your majesties, but the hobgoblin is of a bright yellow colour.”

“Are you all making sport of me?” cried the king in a rage; and turning to the princess, he asked: “What does Adalga say?”

“He appears to me in a silvery light shaded with blue,” answered the princess; “but according to his own statement he does not shine at all.”

The gnomes looked at each other in amazement, and Cravatu said—

“He is a wizard who appears to everyone in another light.”

But the princess continued—

“Although he does not shine, he has a much greater light than we all, for it shines upon everything. He calls it a sun, and he has promised to fetch it to me.”

Therefore the king ordered that I should immediately show him the sun, and when I succeeded in making him understand that it could not be removed from its place in the universe, and that the only way of convincing oneself of its existence was to step within the sphere of its light, the king ordered Cravatu to select immediately a committee of three of the most clever gnomes for the purpose of going to the country of dreams and to hunt for the sun.

Accordingly three gnomes of rank were selected. They were of a white colour, and the light that radiated from them was so brilliant that it dazzled one’s eyes to look at it. They immediately assumed their spherical shapes and floated away; but the king ordered that my execution should be stayed until after their discovery of the sun.

When I heard these words I felt much relieved in my mind, for I had now some hope of escape.

“May your majesty persevere in that resolution!” I said to the king. “For these three messengers will never discover the sun. They have too splendid lights of their own to be able to see beyond it. They will be dazzled and blinded by their own radiance, and not look for the light of the sun.”

Upon hearing these words everybody seemed highly astonished. The gnomes looked at each other in surprise, and whispered: “He is a prophet! He can foretell future events! This is quite supernatural!”

“It does not require any supernatural power,” I said, “to be able to foretell that a thing cannot take place, on account of its being impossible. Everybody knows that a certain amount of darkness is required for the purpose of enabling one to perceive light. Those who are full of their own light cannot see the light of another, just as those who love to hear only themselves talking will not listen to what another one says.”

“Wonderful!” exclaimed the king, and Cravatu whispered to him: “He is one of those who see what is not.”

But I continued saying: “If your majesty wishes to obtain information regarding the existence of truth, I would advise you to send a committee of such as are less conceited and capable of seeing beyond the wall which their egoism has built around them.”

I was still speaking when the three gnomes returned, and they reported unanimously that they had been to dreamland, and that they had seen no other light but their own, and that it was an absurdity to believe in the existence of a universal sun; for if there were such a light it could not have escaped their notice, and, moreover, the presence of such a light would make everybody look of the same colour, so that not one person could be distinguished from another.

Thereupon all the dark gnomes, such as had as little light and intelligence as possible, were gathered, and out of them the king selected three almost entirely dark dwarfs. They were surely the most sorry-looking imbeciles which it has ever been my misfortune to behold. Big-headed, hydrocephalic, with shrunken brains, they were the very personification of abject stupidity; they seemed to have not more understanding than an oyster, although their power of seeing appeared good enough. These were appointed as a committee to seek for the sun, and it was ordered that they should be conducted to the frontier of the outer world, there to be left to their own fate and to begin their researches. This was accordingly done: the three idiots were taken away, and I pitied them, for I doubted whether they would ever have sense enough to find their way back.

“I am curious to hear the report of this committee,” remarked the queen, “perhaps it would have been still better to blindfold them.”

To this I replied—

“I fear that your majesty will be disappointed; for, even if the dwarfs perceive the sun, they will be incapable to understand what they see, or to describe it.”

“Hear! hear!” exclaimed the king, and all the gnomes began to regard me with awe and respect; but Cravatu said—

“Really there is more behind this person than we suspected. He is one of those who sees that which cannot be.”

Thereupon the king conferred upon me the office of head fortune-teller to the court, and I was treated with great respect. The whole behaviour of the gnomes changed; the queen smiled at me, and invited me to the palace; but the princess was delighted, and as she took my arm, she said to me with a triumphant smile: “I knew that you were more than a spook after all.”

February 12, 2025

#WerewolvesWednesday: The Wolf-Leader (introduction)

Alexandre Dumas père is the famous one, the one you have in mind when I say “Dumas”: he was born on July 24, 1802, in Villers-Cotterêts, France, and wrote both The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo.

The Wolf-Leader (original title: Le Meneur de Loups), was written in 1857 and it’s a lesser-known work, set around 1780 in Villers-Cotterêts, Dumas’s native town. The story revolves around the character of Thibault, a shoemaker who wants more from life, and his encounter with a large humanoid wolf with whom he strikes a pact.

The English version provided is the one translated by Alfred Allinson, published in London by Methuen in 1904 under the title The Wolf-Leader. If you want to look it up, there’s another edition from the United States edited and cut by L. Sprague de Camp. The text was also serialized in eight parts in the pulp magazine Weird Tales from August 1931 to March 1932.

Our serialization will keep us company for 15 weeks, including today.

Introduction to the English translationAlthough the introductory chapters were not signed until May 31st, 1856, The Wolf-Leader is to be associated in conception with the group of romances which Dumas wrote at Brussels between the years 1852 and 1854, that is to say, after his financial failure and the consequent defection of his collaborator Maquet, and before his return to Paris to found his journal Le Mousquetaire. Like Conscience V Innocent and Catherine Blum, which date from that period of exile, the present story was inspired by reminiscences of our author’s native place Villers-Cotterets, in the

department of the Aisne.

In The Wolf-Leader Dumas, however, allows his imagination and fancy full play. Using a legend told to him nearly half a century before, conjuring up the scenes of his boyhood, and calling into requisition his wonderful gift of improvisation, he contrives in the happiest way to weave a romance in which are combined a weird tale of diablerie and continual delightful glimpses of forest life. Terror, wood-craft, and humour could not be more felicitously intermingled. The reader, while kept under the spell of the main theme of the story, experiences all the charm of an open-air life in the great forest of Villers-Cotterets the forest in which the little town seemed to occupy a small clearing, and into which the boy Alexandre occasionally escaped for days together from the irksome routine of the school or from the hands of relatives who wanted to make a priest of him.

Thus Dumas, the most impressionable of men, all his life remained grateful to the forest for the poetic fancies derived from its beauty and the mysteries of its recesses, as well as for the hiding-places it afforded him, and for the game and birds which he soon learnt to shoot and snare there. Listen to his indignation at the destruction of the trees in the neighbouring park. We quote from his Memoires: “That park, planted by Francois I., was put down by Louis Philippe. Beautiful trees under whose shade once reclined Francois I. and Madame d’Etarrpes, Henri II. and Diana of Poitiers, Henri IV. and Gabrielle you had a right to believe that a Bourbon would have respected you, that you would have lived your long life the life of beech trees and oaks; that the birds would have warbled on your branches when green and leafy. But over and above your inestimable value of poetry and memories, you had, unhappily, a material value. You beautiful beeches with your polished silvery cases! you beautiful oaks with your sombre wrinkled bark! you were worth a hundred thousand crowns. The King of France, who, with his six millions of private revenue, was too poor to keep you the King of France sold you. For my part, had you been my sole fortune, I would have preserved you; for, poet as I am, there is one thing that I would set before all the gold of the earth, and that is the murmur of the wind in your leaves; the shadow that you made to flicker beneath my feet; the sweet visions, the charming phantoms which, at evening time, betwixt the

day and night, in twilight’s doubtful hour would glide between your age-long trunks as glide the shadows of the ancient Abencerrages amid the thousand columns of Cordova’s royal mosque.”

The Wolf-Leader was published in 1857, in three volumes (Paris: Cadot). Dumas reprinted it in his journal Le Monte-Crisio in 1860.

Introduction: who Mocquet was, and how this tale became known to the narratorI.Why, I ask myself, during those first twenty years of my literary life, from 1827 to 1847, did I so rarely turn my eyes and thoughts towards the little town where I was born, towards the woods amid which it lies embowered, and the villages that cluster round it? How was it that during all that time the world of my youth seemed to me to have disappeared, as if hidden behind a cloud, whilst the future which lay before me shone clear and resplendent, like those magic islands which Columbus and his companions mistook for baskets of flowers floating on the sea?

Alas! simply because during the first twenty years of our life, we have Hope for our guide, and during the last twenty, Reality.

From the hour when, weary with our journey, we ungird ourselves, and dropping the traveller’s staff, sit down by the way side, we begin to look back over the road that we have traversed; for it is the way ahead that now is dark and misty, and so we turn and gaze into the depths of the past.

Then with the wide desert awaiting us in front, we are astonished, as we look along the path which we have left behind, to catch sight of first one and then another of those delicious oases of verdure and shade, beside which we never thought of lingering for a moment, and which, in deed we had passed by almost without notice.

But, then, how quickly our feet carried us along in those days! we were in such a hurry to reach that goal of happiness, to which no road has ever yet brought any one of us.

It is at this point that we begin to see how blind and ungrateful we have been; it is now that we say to ourselves, if we could but once more come across such a green and wooded resting-place, we would stay there for the rest of our lives, would pitch our tent there, and there end our days.

But the body cannot go back and renew its existence, and so memory has to make its pious pilgrimage alone; back to the early days and fresh beginnings of life it travels, like those light vessels that are borne upward by their white sails against the current of a river. Then the body once more pursues its journey; but the body without memory is as the night without stars, as the lamp without its flame … And so body and memory go their several ways.

The body, with chance for its guide, moves towards the unknown.

Memory, that bright will-o’-the-wisp, hovers over the landmarks that are left behind; and memory, we may be sure, will not lose her way. Every oasis is revisited, every association recalled, and then with a rapid flight she returns to the body that grows ever more and more weary, and like the humming of a bee, like the song of a bird, like the murmur of a stream, tells the tale of all that she has seen.

And as the tired traveller listens, his eyes grow bright again, his mouth smiles, and a light steals over his face. For Providence in kindness, seeing that he cannot return to youth, allows youth to return to him. And ever after he loves to repeat aloud what memory tells, him in her soft, low voice.

And is our life, then, bounded by a circle like the earth? Do we, unconsciously, continue to walk towards the spot from which we started? And as we travel nearer and nearer to the grave, do we again draw closer, ever closer, to the cradle?

[image error] The royal huntsman François Antoine kills the Beast of Gévaudan in 1765 (18th-century engraving)II.I can not say. But what happened to myself, that much at any rate I know. At my first halt along the road of life, my first glance backwards, I began by relating the tale of Bernard and his uncle Berthelin, then the story of Ange Pitou, his fair fiancée, and of Aunt Angelique; after that I told of Conscience and Mariette; and lastly of Catherine Blum and Father Vatrin.

I am now going to tell you the story of Thibault and his wolves, and of the Lord of Vez. And how, you will ask, did I become acquainted with the events which I am now about to bring before you? I will tell you.

Have you read my Memoires, and do you remember one, by name Mocquet, who was a friend of my father’s?

If you have read them, you will have some vague recollection of this personage. If you have not read them, you will not remember anything about him at all.

In either case, then, it is of the first importance that I should bring Mocquet clearly before your mind’s eye.

As far back as I can remember, that is when I was about three years of age, we lived, my father and mother and I, in a little château called Les Fosses, situated on the boundary that separates the departments of Aisne and Oise, between Haramont and Longpré. The little house in question had doubtless been named Les Fosses on account of the deep and broad moat, filled with water, with which it was surrounded.

I do not mention my sister, for she was at school in Paris, and we only saw her once a year, when she was home for a month’s holiday.

The household, apart from my father, mother, and myself, consisted firstly of a large black dog, called Truffe, who was a privileged animal and made welcome wherever he appeared, more especially as I regularly went about on his back; secondly, of a gardener named Pierre, who kept me amply provided with frogs and snakes, two species of living creatures in which I was particularly interested; thirdly, of a negro, a valet of my father’s, named Hippolyte, a sort of black merry-andrew, whom my father, I believe, only kept that he might be well primed with anecdotes wherewith to gain the advantage in his encounters with Brunei and beat his wonderful stories; fourthly, of a keeper named Mocquet, for whom I had a great admiration, seeing that he had magnificent stories to tell of ghosts and werewolves, to which I listened every evening, and which were abruptly broken off the instant the General—as my father was usually called—appeared on the scene; fifthly, of a cook, who answered to the name of Marie, but this figure I can no longer recall. It is lost to me in the misty twilight of life; I remember only the name, as given to someone of whom but a shadowy outline remains in my memory, and about whom, as far as I recollect, there was nothing of a very poetic character.

Mocquet, however, is the only person that need occupy our attention for the present. Let me try to make him known to you, both as regards his personal appearance and his character.

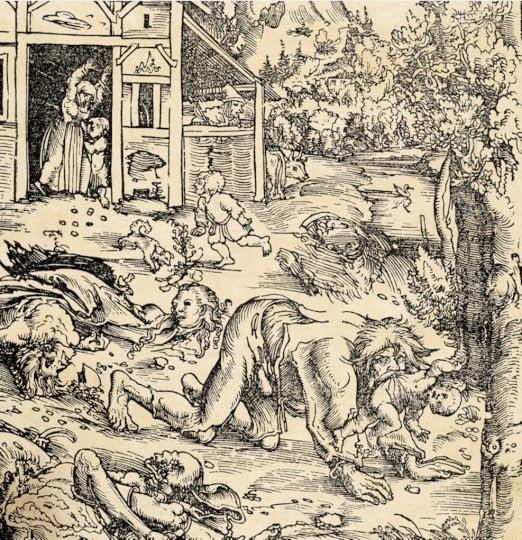

The werewolf, or “The Cannibal” Peter Stumpp, engraved by Lucas Cranach the Elder.Ill.

The werewolf, or “The Cannibal” Peter Stumpp, engraved by Lucas Cranach the Elder.Ill.Mocquet was a man of about forty years of age, short, thick-set, broad of shoulder, and sturdy of leg. His skin was burnt brown by the sun, his eyes were small and piercing, his hair grizzled, and his black whiskers met under his chin in a half-circle.

As I look back, his figure rises before me, wearing a three-cornered hat, and clad in a green waistcoat with silver buttons, velveteen cord breeches, and high leathern gaiters, with a game-bag over his shoulder, his gun in his hand, and a cutty-pipe in his mouth.

Let us pause for a moment to consider this pipe, for this pipe grew to be, not merely an accessory, but an integral part of Mocquet. Nobody could remember ever having seen Mocquet without it. If by any chance Mocquet did not happen to have it in his mouth, he had it in his hand.

This pipe, having to accompany Mocquet into the heart of the thickest coverts, it was necessary that it should be of such a kind as to offer the least possible opportunity to any other solid body of bringing about its destruction; for the destruction of his old, well-coloured cutty would have been to Mocquet a loss that years alone could have repaired. Therefore the stem of Mocquet’s pipe was not more than half an inch long; moreover, you might always wager that half that half-inch at least was supplied by the quill of a feather.

This habit of never being without his pipe, which, by causing the almost entire disappearance of both canines, had hollowed out a sort of vice for itself on the left side of his mouth, between the fourth incisor and the first molar, had given rise to another of Mocquet’s habits; this was to speak with his teeth clenched, whereby a certain impression of obstinacy was conveyed by all he said. This became even more marked if Mocquet chanced at any moment to take his pipe out of his mouth, for there was nothing then to prevent the jaws closing and the teeth coming together in a way which prevented the words passing through them at all except in a sort of whistle, which was hardly intelligible.

Such was Mocquet with respect to outward appearance. In the following pages, I will endeavour to give some idea of his intellectual capacity and moral qualities.

An attack of the Gévaudan Beast.IV.

An attack of the Gévaudan Beast.IV.Early one morning, before my father had risen, Mocquet walked into his room and planted himself at the foot of the bed, stiff and upright as a signpost.

“Well, Mocquet,” said my father, “what’s the matter now? What gives me the pleasure of seeing you here at this early hour?”

“The matter is, General,” replied Mocquet with the utmost gravity, “the matter is that I am nightmared.”

Mocquet had, quite unawares to himself, enriched the language with a double verb, both active and passive.

“You are nightmared?” responded my father, raising himself on his elbow. “Dear, dear, that’s a serious matter, my poor Mocquet.”

“You are right there, General.”

And Mocquet took his pipe out of his mouth, a thing he did rarely and only on the most important occasions.

“And how long have you been nightmared?” continued my father compassionately.

“For a whole week, General.”

“And who by, Mocquet?”

“Ah! I know very well who by,” answered Mocquet, through his teeth, which were so much the more tightly closed that his pipe was in his hand, and his hand behind his back.

“And may I also know by whom?”

“By Mother Durand of Haramont, who, as you will have heard, is an old witch.”

“No, indeed, I assure you I had no idea of such a thing.”

“Ah! but I know it well enough; I’ve seen her riding past on her broomstick to her Witches’ Sabbath.”

“You have seen her go by on her broomstick?”

“As plainly as I see you, General; and more than that, she has an old black billy-goat at home that she worships.”

“And why should she come and nightmare you?”

“To revenge herself on me, because I came upon her once at midnight on the heath of Gondreville, when she was dancing round and round in her devil’s circle.”

“This is a most serious accusation which you bring against her, my friend; and before repeating to anyone what you have been telling me in private, I think it would be as well if you tried to collect some more proofs.”

“Proofs! What more proofs do I want! Does not every soul in the village know that in her youth she was the Mistress of Thibault, the wolf-leader?”

“Indeed! I must look carefully into this matter, Mocquet.”

“I am looking very carefully into it myself, and she shall pay for it, the old mole!”

“Old mole” was an expression that Mocquet had borrowed from his friend Pierre, the gardener, who, as he had no worse enemies to deal with than moles, gave the name of mole to everything and everybody that he particularly detested.

“I must look carefully into this matter”—these words were not said by my father by reason of any belief he had in the truth of Mocquet’s tale about his nightmare; and even the fact of the nightmare being admitted by him, he gave no credence to the idea that it was Mother Durand who had nightmared the keeper. Far from it; but my father was not ignorant of the superstitions of the people, and he knew that belief in spells was still widespread among the peasantry in the country districts. He had heard of terrible acts of revenge carried out by the victims on some man or woman who they thought had bewitched them, in the belief that the charm would thus be broken; and Mocquet, while he stood denouncing Mother Durand to my father, had had such an accent of menace in his voice and had given such a grip to his gun that my father thought it wise to appear to agree with everything he said, in order to gain his confidence and so prevent him from doing anything without first consulting him.

So, thinking that he had so far gained an influence over Mocquet, my father ventured to say:

“But before you make her pay for it, my good Mocquet, you ought to be quite sure that no one can cure you of your nightmare.”

“No one can cure me, General,” replied Mocquet in a tone of conviction.

“How! No one able to cure you?”

“No one; I have tried the impossible.”

“And how did you try?”

“First of all, I drank a large bowl of hot wine before going to bed.”

“And who recommended that remedy? Was it Monsieur Lecosse?” Monsieur Lecosse was the doctor in repute at Villers-Cotterets.

“Monsieur Lecosse?” exclaimed Mocquet. “No, indeed! What should he know about spells! By my faith, no! It was not Monsieur Lecosse.”

“Who was it, then?”

“It was the shepherd of Longpré.”

“But a bowl of wine, you dunderhead! Why, you must have been dead drunk.”

“The shepherd drank half of it.”

“I see; now I understand why he prescribed it. And did the bowl of wine have any effect?”

“Not any, General; she came trampling over my chest that night, just as if I had taken nothing.”

“And what did you do next? You were not obliged, I suppose, to limit your efforts to your bowl of hot wine?”

“I did what I do when I want to catch a wily beast.”

Mocquet made use of a phraseology which was all his own; no one had ever succeeded in inducing him to say a wild beast; every time my father said wild beast, Mocquet would answer, “Yes, General, I know, a wily beast.”

“You still stick to your wily beast, then?” my father said to him on one occasion.

“Yes, General, but not out of obstinacy.”

“And why then, may I ask?”

“Because, General, with all due respect to you, you are mistaken about it.”

“Mistaken? I? How?”

“Because you ought not to say a wild beast, but a wily beast.”

“And what is a wily beast, Mocquet?”

“It is an animal that only goes about at night; that is, an animal that creeps into the pigeon-houses and kills the pigeons, like the polecat, or into the chicken-houses, to kill the chickens, like the fox, or into the folds, to kill the sheep, like the wolf; it means an animal which is cunning and deceitful—in short, a wily beast.”

It was impossible to find anything to say after such a logical definition as this. My father, therefore, remained silent, and Mocquet, feeling that he had gained a victory, continued to call wild beasts wily beasts, utterly unable to understand my father’s obstinacy in continuing to call wily beasts wild beasts.

So now you understand why, when my father asked him what else he had done, Mocquet answered, “I did what I do when I want to catch a wily beast.”

We have interrupted the conversation to give this explanation, but as there was no need of explanation between my father and Mocquet, they had gone on talking, you must understand, without any such break.

VI.“And what is it you do, Mocquet, when you want to catch this animal of yours?” asked my father.

“I set a trarp, General.” Mocquet always called a trap a trarp.

“Do you mean to tell me you have set a trap to catch Mother Durand?”

My father had, of course, said trap, but Mocquet did not like anyone to pronounce words differently from himself, so he went on:

“Just so, General; I have set a trarp for Mother Durand.”

“And where have you put your trarp? Outside your door?”

My father, you see, was willing to make concessions.

“Outside my door! Much good that would be! I only know she gets into my room, but I cannot even guess which way she comes.”

“Down the chimney, perhaps?”

“There is no chimney, and besides, I never see her until I feel her.”

“And you do see her, then?”

“As plainly as I see you, General.”

“And what does she do?”

“Nothing agreeable, you may be sure; she tramples all over my chest: thud, thud! thump, thump!”

“Well, where have you set your trap, then?”

“The trarp, why, I put it on my own stomach.”

“And what kind of a trarp did you use?”

“Oh! a first-rate trarp!”

“What was it?”

“The one I made to catch the grey wolf with, that used to kill M. Destournelles’ sheep.”

“Not such a first-rate one, then, for the grey wolf ate up your bait and then bolted.”

“You know why he was not caught, General.”

“No, I do not.”

“Because it was the black wolf that belonged to old Thibault, the sabot-maker.”

“It could not have been Thibault’s black wolf, for you said yourself just this moment that the wolf that used to come and kill M. Destournelles’ sheep was a grey one.”

“He is grey now, General; but thirty years ago, when Thibault the sabot-maker was alive, he was black; and, to assure you of the truth of this, look at my hair, which was black as a raven’s thirty years ago, and now is as grey as the Doctor’s.”

The Doctor was a cat, an animal of some fame, that you will find mentioned in my Memoires and known as the Doctor on account of the magnificent fur which nature had given it for a coat.

“Yes,” replied my father, “I know your tale about Thibault, the sabot-maker; but if the black wolf is the devil, Mocquet, as you say he is, he would not change colour.”

“Not at all, General; only it takes him a hundred years to become quite white, and the last midnight of every hundred years, he turns black as a coal again.”

“I give up the case, then, Mocquet: all I ask is that you will not tell my son this fine tale of yours until he is fifteen at least.”

“And why, General?”

“Because it is no use stuffing his mind with nonsense of that kind until he is old enough to laugh at wolves, whether they are white, grey, or black.”

“It shall be as you say, General; he shall hear nothing of this matter.”

“Go on, then.”

“Where had we got to, General?”

“We had got to your trarp, which you had put on your stomach, and you were saying that it was a first-rate trarp.”

“By my faith, General, that was a first-rate trarp! It weighed a good ten pounds. What am I saying! Fifteen pounds at least, with its chain! I put the chain over my wrist.”

“And what happened that night?”

“That night? Why, it was worse than ever! Generally, it was in her leather overshoes she came and kneaded my chest, but that night she came in her wooden sabots.”

“And she comes like this…?”

“Every blessed one of God’s nights, and it is making me quite thin; you can see for yourself, General, I am growing as thin as a lath. However, this morning I made up my mind.”

“And what did you decide upon, Mocquet?”

“Well, then, I made up my mind I would let fly at her with my gun.”

“That was a wise decision to come to. And when do you think of carrying it out?”

“This evening, or to-morrow at latest, General.”

“Confound it! And just as I was wanting to send you over to Villers-Hellon.”

“That won’t matter, General. Was it something that you wanted done at once?”

“Yes, at once.”

“Very well, then, I can go over to Villers-Hellon, it’s not above a few miles, if I go through the wood and get back here this evening; the journey both ways is only twenty-four miles, and we have covered a few more than that before now out shooting, General.”

“That’s settled, then; I will write a letter for you to give to M. Collard, and then you can start.”

“I will start, General, without a moment’s delay.”

My father rose and wrote to M. Collard; the letter was as follows:

My dear Collard,

I am sending you that idiot of a keeper of mine, whom you know; he has taken into his head that an old woman nightmares him every night, and, to rid himself of this vampire, he intends nothing more nor less than to kill her.

Justice, however, might not look favourably on this method of his for curing himself of indigestion, and so I am going to start him off to you on a pretext of some kind or other. Will you, also, on some pretext or other, send him on, as soon as he gets to you, to Danre, at Vouty, who will send him on to Dulauloy, who, with or without pretext, may then, as far as I care, send him on to the devil?

In short, he must be kept going for a fortnight at least. By that time we shall have moved out of here and shall be at Antilly, and as he will then no longer be in the district of Haramont, and as his nightmare will probably have left him on the way, Mother Durand will be able to sleep in peace, which I should certainly not advise her to do if Mocquet were remaining anywhere in her neighbourhood.

He is bringing you six brace of snipe and a hare, which we shot while out yesterday on the marshes of Vallue.

A thousand-and-one of my tenderest remembrances to the fair Herminie, and as many kisses to the dear little Caroline.

Your friend,

ALEX. DUMAS

An hour later Mocquet was on his way, and, at the end of three weeks, he rejoined us at Antilly.

“Well,” asked my father, seeing him reappear in robust health, “well, and how about Mother Durand?”

“Well, General,” replied Mocquet cheerfully, “I’ve got rid of the old mole; it seems she has no power except in her own district.”

VII.Twelve years had passed since Mocquet’s nightmare, and I was now over fifteen years of age. It was the winter of sixty-six; ten years before that date I had, alas! lost my father.

We no longer had a Pierre for gardener, a Hippolyte for valet, or a Mocquet for keeper; we no longer lived at the Château of Les Fosses or in the villa at Antilly, but in the marketplace of Villers-Cotterêts, in a little house opposite the fountain, where my mother kept a bureau de tabac, selling powder and shot as well over the same counter.

As you have already read in my Mémoires, although still young, I was an enthusiastic sportsman. As far as sport went, however, that is, according to the usual acceptation of the word, I had none, except when my cousin, M. Deviolaine, the ranger of the forest at Villers-Cotterêts, was kind enough to ask leave of my mother to take me with him. I filled up the remainder of my time with poaching.

For this double function of sportsman and poacher, I was well provided with a delightful single-barrelled gun, on which was engraved the monogram of the Princess Borghese, to whom it had originally belonged. My father had given it to me when I was a child, and when, after his death, everything had to be sold, I implored so urgently to be allowed to keep my gun that it was not sold with the other weapons, the horses, and the carriages.

The most enjoyable time for me was the winter; then the snow lay on the ground, and the birds, in their search for food, were ready to come wherever grain was sprinkled for them. Some of my father’s old friends had fine gardens, and I was at liberty to go and shoot the birds there as I liked. So I used to sweep the snow away, spread some grain, and, hiding myself within easy gunshot, fire at the birds, sometimes killing six, eight, or even ten at a time.

Then, if the snow lasted, there was another thing to look forward to—the chance of tracing a wolf to its lair, and a wolf so traced was everybody’s property. The wolf, being a public enemy, a murderer beyond the pale of the law, might be shot at by all or anyone, and so, in spite of my mother’s cries, who dreaded the double danger for me, you need not ask if I seized my gun and was first on the spot, ready for sport.

The winter of 1817 to 1818 had been long and severe; the snow was lying a foot deep on the ground, and so hard frozen that it had held for a fortnight past, and still there were no tidings of anything.

Towards four o’clock one afternoon, Mocquet called upon us; he had come to lay in his stock of powder. While so doing, he looked at me and winked with one eye. When he went out, I followed.

“What is it, Mocquet?” I asked. “Tell me.”

“Can’t you guess, Monsieur Alexandre?”

“No, Mocquet.”

“You don’t guess, then, that if I come and buy powder here from Madame, your mother, instead of going to Haramont for it—in short, if I walk three miles instead of only a quarter of that distance—that I might possibly have a bit of a shoot to propose to you?”

“Oh, you good Mocquet! And what and where?”

“There’s a wolf, Monsieur Alexandre.”

“Not really?”

“He carried off one of M. Destournelles’ sheep last night. I have traced him to the Tillet woods.”

“And what then?”

“Why then, I am certain to see him again tonight and shall find out where his lair is, and tomorrow morning we’ll finish his business for him.”

“Oh, this is luck!”

“Only, we must first ask leave…”

“Of whom, Mocquet?”

“Leave of Madame.”

“All right, come in, then, we will ask her at once.”

My mother had been watching us through the window; she suspected that some plot was hatching between us.

“I have no patience with you, Mocquet,” she said as we went in. “You have no sense or discretion.”

“In what way, Madame?” asked Mocquet.

“To go exciting him in the way you do; he thinks too much of sport as it is.”

“Nay, Madame, it is with him as with dogs of breed; his father was a sportsman, he is a sportsman, and his son will be a sportsman after him; you must make up your mind to that.”

“And supposing some harm should come to him?”

“Harm come to him with me? With Mocquet? No, indeed! I will answer for it with my own life that he shall be safe. Harm happen to him, to him, the General’s son? Never, never, never!”

But my poor mother shook her head; I went to her and flung my arms around her neck.

“Mother, dearest,” I cried, “please let me go.”

“You will load his gun for him, then, Mocquet?”

“Have no fear—sixty grains of powder, not a grain more or less, and a twenty-to-the-pound bullet.”

“And you will not leave him?”

“I will stay by him like his shadow.”

“You will keep him near you?”

“Between my legs.”

“I give him into your sole charge, Mocquet.”

“And he shall be given back to you safe and sound. Now, Monsieur Alexandre, gather up your traps, and let us be off; your mother has given her permission.”

“You are not taking him away this evening, Mocquet.”

“I must, Madame; tomorrow morning will be too late to fetch him; we must hunt the wolf at dawn.”

“The wolf! It is for a wolf-hunt that you are asking for him to go with you?”

“Are you afraid that the wolf will eat him?”

“Mocquet! Mocquet!”

“But when I tell you that I will be answerable for everything!”

“And where will the poor child sleep?”

“With Father Mocquet, of course. He will have a good mattress laid on the floor, and sheets white as those which God has spread over the fields, and two good warm coverlids; I promise you that he shall not catch cold.”

“I shall be all right, mother, you may be sure! Now then, Mocquet, I am ready.”

“And you don’t even give me a kiss, you poor boy, you!”

“Indeed, yes, dear mother, and a good many more than one!”

And I threw myself on my mother’s neck, stifling her with my caresses as I clasped her in my arms.

“And when shall I see you again?”

“Oh, do not be uneasy if he does not return before tomorrow evening.”

“How, tomorrow evening! And you spoke of starting at dawn!”

“At dawn for the wolf; but if we miss him, the lad must have a shot or two at the wild ducks on the marshes of Vallue.”

“I see! You are going to drown him for me!”

“By the name of all that’s good, Madame, if I was not speaking to the General’s widow, I should say—”

“What, Mocquet? What would you say?”

“That you will make nothing but a wretched milksop of your boy… If the General’s mother had been always behind him, pulling at his coattails, as you are behind this child, he would never even have had the courage to cross the sea to France.”

“You are right, Mocquet! Take him away! I am a poor fool.”

And my mother turned aside to wipe away a tear.

A mother’s tear, that heart’s diamond, more precious than all the pearls of Ophir! I saw it running down her cheek. I ran to the poor woman and whispered to her, “Mother, if you like, I will stay at home.”

“No, no, go, my child,” she said. “Mocquet is right; you must, sooner or later, learn to be a man.”

I gave her another last kiss; then I ran after Mocquet, who had already started.

After I had gone a few paces, I looked round; my mother had run into the middle of the road so that she might keep me in sight as long as possible. It was my turn now to wipe away a tear.

“How now?” said Mocquet, “You crying too, Monsieur Alexandre!”

“Nonsense, Mocquet! It’s only the cold makes my eyes run.”

But Thou, O God, who gavest me that tear, Thou knowest that it was not because of the cold that I was crying.

Werewolf illustration for ‘Legendes Rustiques’ by George Sand, 19th Century. The werewolves are famously waiting outside the walls of a cemetery.VIII.

Werewolf illustration for ‘Legendes Rustiques’ by George Sand, 19th Century. The werewolves are famously waiting outside the walls of a cemetery.VIII.It was pitch dark when we reached Mocquet’s house. We had a savoury omelette and stewed rabbit for supper, and then Mocquet made my bed ready for me. He kept his word to my mother, for I had a good mattress, two white sheets, and two good warm coverlids.

“Now,” said Mocquet, “tuck yourself in there and go to sleep; we may probably have to be off at four o’clock tomorrow morning.”

“At any hour you like, Mocquet.”

“Yes, I know, you are a capital riser over night, and tomorrow morning I shall have to throw a jug of cold water over you to make you get up.”

“You are welcome to do that, Mocquet, if you have to call me twice.”

“Well, we’ll see about that.”

“Are you in a hurry to go to sleep, Mocquet?”

“Why, whatever do you want me to do at this hour of the night?”

“I thought, perhaps, Mocquet, you would tell me one of those stories that I used to find so amusing when I was a child.”

“And who is going to get up for me at two o’clock tomorrow if I sit telling you tales till midnight? Our good priest, perhaps?”

“You are right, Mocquet.”

“It’s fortunate you think so!”

So I undressed and went to bed. Five minutes later, Mocquet was snoring like a bass viol.

I turned and twisted for a good two hours before I could get to sleep. How many sleepless nights have I not passed on the eve of the first shoot of the season! At last, towards midnight, fatigue gained the mastery over me. A sudden sensation of cold awoke me with a start at four o’clock in the morning; I opened my eyes. Mocquet had thrown my bedclothes off over the foot of the bed and was standing beside me, leaning both hands on his gun, his face beaming out upon me as, at every fresh puff of his short pipe, the light from it illuminated his features.

“Well, how have you got on, Mocquet?”

“He has been tracked to his lair.”

“The wolf? And who tracked him?”

“This foolish old Mocquet.”

“Bravo!”

“But guess where he has chosen to take covert, this most accommodating of good wolves!”

“Where was it, then, Mocquet?”

“If I gave you a hundred chances, you wouldn’t guess! In the Three Oaks Covert.”

“We’ve got him, then?”

“I should rather think so.”

The Three Oaks Covert is a patch of trees and undergrowth, about two acres in extent, situated in the middle of the plain of Largny, about five hundred paces from the forest.

“And the keepers?” I went on.

“All had notice sent them,” replied Mocquet. “Moynat, Mildet, Vatrin, Lafeuille—all the best shots, in short, are waiting in readiness just outside the forest. You and I, with Monsieur Charpentier from Vallue, Monsieur Hochedez from Largny, and Monsieur Destournelles from Les Fosses, are to surround the covert. The dogs will be slipped, the field-keeper will go with them, and we shall have him, that’s certain.”

“You’ll put me in a good place, Mocquet?”

“Haven’t I said that you will be near me? But you must get up first.”

“That’s true. Brrrrou!”

“And I am going to have pity on your youth and put a bundle of wood in the fireplace.”