Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 18

January 15, 2025

Winter Tales: The Wanderings of an Immortal

William Harrison Ainsworth (February 4, 1805 – January 3, 1882) was an English historical novelist known for his contributions to the Gothic genre and historical fiction. Born in Manchester, he initially trained as a lawyer but soon turned his focus to literature, where he found considerable success. Though his first published novel, Sir John Chiverton, appeared in 1826, it was Rookwood (1834) which gained him notoriety, as it featured the infamous highwayman Dick Turpin. Fans of Good Omens have heard about him for sure.

Today’s story comes from an early collection called December Tales, published in December 1823 when the author was just eighteen, and it’s called “The Wanderings of an Immortal”. Enjoy.

For me the laws of Nature are suspended: the eternal wheels

of the Universe roll backwards: I am destined to be triumphant

over Fate and Time.

I shall take my distant posterity by the hand; I shall close the

tomb over them.

ST. LEON.

It was not a vain desire of life, or a fear of death, that made me long for immortality; nor was it the cupidity of wealth, or the love of splendour, or of pleasure, that made me spend years of anxious study to penetrate into the hidden recesses of Nature, and drag forth those secrets which she has involved in an almost impenetrable obscurity; but it was the desire of revenge, of deep-seated and implacable revenge, that urged me on, till by incredible exertion and minute investigation, I discovered that which it has by turns been the object of philosophy to obtain, and the aim of incredulity to ridiculethe philosopher’s stone. And yet, I was naturally of a mild and compassionate disposition. I had a heart open to the tenderest and best emotions of our nature; injury heaped on injury,-received, too, from one whose highest aim ought to have been to manifest the gratitude which he owed to me, who, in the hour of danger and adversity, should have been the readiest to offer assistance,has rendered me what I am.

It is useless to add to the instances of human depravity. I will not relate the miseries which I endured. I will not look back upon the prospects which have been blasted by the perfidy of him whom I thought a friend; suffice it, that they have been such as the soul shudders to contemplate; such as planted in my soul a thirst of vengeance, which I brooded over, till it became a part of my very existence.

I soon found, that by human means I had little chance of revenge. My enemy was powerful and cautious, and all my plans were anticipated and baffled. I determined to have recourse to darker agents. I had been accustomed to intense and mysterious study, and I knew that there are beings who exercise an influence over human affairs, and are, likewise, themselves in subjection to the wise and omnipotent Being, who is the mover of the first springs of the mighty machine of the universe. I knew, too, that it was possible to exert a power over these beings; and henceforth, I applied the whole force of my mind to the acquisition of the knowledge, which would make me the possessor of this power. Ten long years I employed for this purpose, and my efforts were crowned with success. But though I could summon these spirits before me, and compel them to give an answer to my inquiries, that was all; I could not, I was sensible, subject them entirely to my will, without making, on my part, certain concessions, and to ascertain what these were, was the object of my first trial.

I fixed on a night for this my first essay, and it soon arrived. I repaired to the spot which I had selected. Its secrecy was well calculated for my purpose; it was a dark and lonely glen, but it was rich in romantic beauty. Rocks, whose brinks were covered with underwood and wild herbage, frowned on each side; a few stunted oaks threw out their roots clinging to the precipice, and an immense elm on one side spread its wide arms around. The bottom of the area was covered with dark luxuriant grass, interspersed with wild and fragrant flowers. At one end a narrow but deep river tumbled its waters over the precipice, and rushed down, sometimes almost concealed by jutting fragments of rocks covered with moss and plants, which clung to it as if for protection from the force of the cataract; then again spreading out and dashing its roaring waters along, till it finally vanished under ground in a cloud of mist and foam.

The moon was shining brightly, and I ascended an eminence which commanded an extensive prospect. On one side, wide and fertile plains extended themselves, spotted at a distance with straggling cottages and small hamlets, bounded with forests, whose dark and heavy masses contrasted finely with the light of the adjacent landscape. On the right, the river rolled its waves in calm windings, between banks of lively green, adorned with groves and clusters of trees, till it terminated in the waterfall, which dashed far beneath me with a softened murmur. It was a delightful scene. The sky was beautifully clear; fleecy clouds skimmed over it, lighted up with a silvery lustre that they caught from the moon-beams, which bursting from behind them as they passed, fell on the waters of the stream and the cataract, and trembled on them in liquid beauty. Waves, rocks, woods, plains, all glittered in the lovely rays, and all spoke of peace and harmony.

As I gazed on the beauties which Nature had here scattered with so profuse a hand, I heard the tinkling of a sheep-bell. What associations did this slight sound conjure up to me! All the loved and well-remembered scenes of childhood crowded on my mind. I thought of times and of persons that were fled; of those who were joined to me by kindred, who were united by friendship, or attached by a tender passion. Again, those short but blissful moments were present-perhaps more blissful, because so short-when I had strayed, at this same witching hour, with one whose remembrance will survive the eternity which I am doomed to undergo;-when we had gazed with all the rapture of admiration on the works which attest the power and mightiness of Providence-had listened to the note of the evening songster, and the sighs of the wind among the leaves; and with hearts unstained by one evil thought or passion, and feelings unmixed with aught unworthy, had breathed forth our pure and fervent vows to that Being, whose altar is the sincere bosom, and whose purest, most grateful offering, is a tear.

The night advanced. It was time for me to begin my terrible solemnities. I trembled at the thought of what I was about to do. hesitated whether to proceed; but the hope of revenge still impelled me on, and I resolved to prosecute my design. It was soon done. The rites were begun; the flame of my lamp blazed clear and bright; I knew the moment was ap proaching when I should hold communion with beings of another world; perhaps with the prince of darkness himself. I grew faint, a heavy load weighed on my breast, my respiration grew thick and short, my eyes seemed to swell in their sockets, and a cold sweat burst from every pore of my body. The flame wavered-it decreased-it went out. The heavens were darkened : I gazed around, but the gloom was too great for me to see any thing. I looked towards the waterfall, and, amid the mist and obscurity which covered the place of its subterraneous outlet, a star shone with wild and brilliant lustre. It grew larger-it approached me-it stopped, and a brighter radiance was diffused around. The Evil One stood before me.

On I gazed with wonder and astonishment the being that stood before me in terrible beauty. His figure was tall and commanding, and his athletic and sinewy limbs were formed in the most exquisite proportions. His countenance was pale and majestic, but marked with the mingled passions of pride, malice, and regret, which, we conceive, form the character of the rebel angel; and his dark and terrible eyes gave a wilder expression to his features, as they beamed in troubled and preternatural brightness from beneath his awful forehead, shaded with the masses of his raven hair, that curled around his temples, and waved down his neck and shoulders; and amongst the jetty locks, a star, as a diadem, blazed clear and steadily. Never had I seen aught approaching to his grand and unearthly loveliness; I saw him debased by the grossness of sin, and suffering the punishment of his apostacy; yet he was beautiful beyond the sons of men. I saw him thus, and I thought what the spirit must have been before he fell.

Our conversation was brief: I wished not to prolong it, for I was sick at heart, and his voice thrilled through my whole frame. I rejected his offers, strong as was my thirst for vengeance. A small glimmering of cool reason, which I still retained, prevented me from sacrificing all my hopes of hereafter, to the gratification of any passion, however ardent. The demon perceived that I should escape his toils, and ungoverned force of his burst forth; and overcome with I fell senseless on the ground. all was still; it was quite light. I felt the light breezes sweep over me, and I heard again the roar of the cataract. I arose and looked round, but there was nothing to indicate the late presence and all the wild fiendish nature fear and horror, When I awoke, of the demon, with whom I had held unhallowed communion. I departed from the glen; the sun was just rising, and his rays shining on the summits of the lofty and distant hills. The air was sweet and refreshing, and the sky, rich in the glories of the opening morning, was painted with beautiful tints, which blend insensibly with each other, and present so lovely a feast to the eye of one, who loves to study the beauties which Nature offers on every hand, and in almost every prospect. The birds were singing in the trees; the flowers, which had drooped and hung their faded leaves the evening before, again raised up their heads, enamelled with dew; every thing was gentle, beautiful, and peaceful. The charm communicated itself naturally to my disturbed and agitated mind, and for a short time I was calm and serene; the headstrong current of my passions was checked, and the thought of revenge was forgotten. But I returned into the world; I found myself an object, by turns, of scorn and pity, and of hatred. Again, I cursed him who had wrought this wreck of my hopes; and again, was vengeance my only object.

I resolved to have no further communication with the beings of whom I have spoken determined, thenceforth, to depend on my own exertions. I again applied myself to study, and began to inquire after that secret which could bestow immortal life and wealth. I sought the assistance of none, but depended entirely on myself. I laboured long, and was long unsuccessful. I ransacked the most hidden cabinet of nature. In the bowels of the earth, in the corruption of the grave, in darkness and in solitude, I worked with unceasing toil. My body was emaciated, and I was worn almost to a skeleton ; but the vehemence of my passions supported me. At last, I discovered the object of my search. It will prove how strongly my mind was riveted on one sole object, when I say, that when I beheld myself possessed of boundless riches, and, through their agency, of almost boundless power; when the pleasures and temptations of the world lay all within my grasp, I cast not a thought on them, or on any thing, save the one great object, on the furtherance of which I had bestowed such unremitting toil of body and mind.

At this period, I learnt that the object of my hatred was going abroad, and I lost no time in preparing secretly to follow him. He shortly departed; and having disguised myself, I also commenced the journey. I was always on the watch for an opportunity when I could surprise my enemy alone; but I was still unsuccessful. We at last arrived at a sea-port town, and it was determined to proceed by water, and I entered as a passenger into the same vessel. I had never before been at sea, and the scene was new and astonishing to me, but I could not enjoy it; I saw every thing through a cloud. The ardent passion of revenge, which burnt within my breast, consumed and obliterated every gentle or pleasant feeling. At another time I should have enjoyed my situation; I should have beheld the seemingly boundless expanse of water around me, and have felt my soul expand at the view; but now I was altered, and my views of surrounding objects altered with me.

I had much trouble to keep concealed, for on board of a ship the risks of discovery were greater, because my absence from the deck, where the other passengers were accustomed to catch the fresh sea breeze, though for some time unnoticed, might at length cause me to be regarded as a misanthrope, who detested the society of his fellow creatures, which I wished to avoid equally with any other surmise which might make me an object of attention. I was standing one evening watching the gradual decline of the sun as he sunk into the heart of the ocean, which reflected his rays, and the lustre of the clouds around him. A sudden motion of the ship caused me to move from the spot on which I was gazing, when I observed some one looking steadily at me. My eye met his-our souls met in the glance-it was he whom I had followed with such relentless hatred. I sprung towards him. I uttered some incoherent words of rage. He smiled at me in scorn. 66 Madman,” he exclaimed, “dost thou tempt my rage?-Be cautious ere it is too late-you are in my power-one word of mine can make you a prisoner; think you that I am ignorant of your proceedings against my life? -No-every plot, every machination is as well known to me as to yourself;-you confess it-your eye says it-seek not to deny it; for this time you are safe.” He staid no longer, but retiring to his cabin, left me too astonished with what I had heard, to attempt to detain him. Could it be that he had spoken true? was he indeed so well acquainted with my actions? But if so, why had he

not disclosed what he knew, when the civil power could at once have forfeited my life,and deprived him of an enraged foe? Was it that he hesitated to add to his guilt by the death of one whom he had driven to desperation by his treachery? or did some spark of awakening conscience operate on his mind? I was confused with my thoughts, for I knew not what to think; I passed the time in gloomy and painful meditation, and was glad when evening came, that I might retire to my place of repose.

I was awakened by the sound of men trampling over my head, the stretching and creaking of cordage, the dashing of waves, and the violent and repeated motions of the vessel. The wind, which had been remarkably still the preceding day, was blowing with the utmost violence, and roared amongst the sails and rigging of the ship as if it would split them to shivers. It would be useless to attempt to describe what has so often been described far better than I am able to do. I was filled with most dark and melancholy ideas -I paced the cabin in a state of feverish anxiety; but yet I knew not why I felt so. It was not the storm, for my existence was beyond the power of the ocean to destroy. The tempest raged with unabating fury during the whole night. At length a plank of the ship started, and she rapidly filled with water. The boats were got out, and the crew and passengers hastily endeavoured to get into them. The boats were not large enough to contain the whole number, and a dreadful struggle took place; but it was soon terminated by those in the boats cutting the ropes, fearful of perishing, if more were added to their numbers. Just as the boats were cut from the vessel, I saw my hated foe spring out of the ship; he was toɔ late, and was whelmed in the ocean. I thought my hopes of vengeance would be entirely frustrated. I sprung after him. I fell so near him, that I caught hold of him. He grasped me by the throat, and we struggled a moment; but a wave dashed us against the ship’s side, and we were parted by the violence of the shock. Daylight was breaking, and occasionally, when lifted up by a wave, I could discern bodies floating amongst casks, planks, and pieces of broken masts. In little more than a minute after we had left the ship, I saw her sink. Her descent made a wide chasm in the waves, and the rush of the parted waters was dreadful, as they closed over, and dashing up their white foam as they met, seemed to exult over their victim. I was dashed about in the water till I was exhausted: I could no longer take my breath, and began to sink; I struggled hard to keep up, but the tempest subsided, and I was no longer borne up by the force of the waves. I descended-they were the most horrible moments of my life. I gasped for breath, but my mouth and throat were instantly filled with water, and the passage totally obstructed; the air confined in my lungs endeavoured in vain to force an outlet; I felt a tightness at the inside of my ears; the external pressure of the water on all sides of my body was very painful, and my eyes felt as if a cord were tied tightly round my brows. At last, by a dreadful convulsion of my whole body, the air was expelled through my windpipe, and forced its way through the water with a gurgling sound:-again the same sensations recurred—and again the same convulsion. Then I cursed the hour when I had obtained the fatal session which hindered me from perishing. Ardently did I long for death to free me from the suffer. ings which I endured. In a short time I was exhausted, the convulsions became more frequent but less powerful, and I gradually lost all sense and feeling.

How long I continued in this state, buried in the sea, I know not; but when I recovered my recollection, I found myself lying on a rock that jutted out into the ocean. I got up, but could scarcely stand, so great was my weakness; I soon, however, regained my faculties, and my first object was to ascertain where I was. I examined the spot-it was desolate and barren, but it seemed to be of considerable extent. I wandered about till hunger reminded me that I must look for food. A few shell-fish, which I picked up on the shore, satisfied for a time the cravings of my hunger. I then sought for a lodging, which might in some degree shelter me from the fury of the elements. There seemed not to be a tree on the whole surface of the place, nor were the slightest traces of a human habitation visible. At length I discovered a cave, into which I entered, and in which I passed the remainder of the day and the following night. I slept long and soundly, and was greeted, on awaking, by the hoarse and sullen murmurs of the waters breaking against the rock. I advanced to the shore, and strained my eyes over the sea; but nothing was discernible, save the uniform sheet of water, and the black clouds which seemed its only boundary. The day was gloomy, and hoarse sea birds flew round, screaming and flapping their wings. The hours passed slowly on, and this day passed like the preceding one, except that I discovered a spring of water, which in my present situation was a treasure. At night I retired to my cave, where a little sea-weed, spread upon sand, was my only couch. The next day I determined thoroughly to examine the place on which my unhappy fortune had cast me, and I accordingly set forth, dropping sea-weed and pebbles at short intervals, to enable me to find my way back to the cave. I wandered as near as I could guess about two hours, without perceiving any difference in the scenes around me. I was about to return, when a sound struck my ear. I listened-I turned my head, and beheld at no great distance a human figure. I rushed towards it—it was my enemy! He saw me approach, and seemed astonished; but he did not move, nor attempt to avoid me. “At last,” I said, “I have met thee on equal terms;” now thou canst not escape me.” “What seek you?” replied he; “but I need not ask. It is my life you wish to deprive me of-take it—in so doing, you will rob me of that which I wish not to preserve→ a burden that I would gladly lose. You hesitate. Why do you delay now?-vengeance is in your power-do yourself justice-think of the wrongs that you have suffered from me-the miseries you have endured; and then can you remain long inactive?” I knew not what it was, but something restrained me from any deed of violence against him, whom I had followed so long, in hopes of vengeance; whom I had hated with unnatural hatred. While I looked at him he suddenly grew paler; he staggered, and fell down. I found he had fainted-I chafed his temples-I ran for some water, with which I sprinkled his face, and after some time he opened his eyes, but closed them again with a faint shudder. In a few minutes he recovered, but was unable to walk, the hardships he had undergone having weakened his frame, unsupported by the charm which gave strength and endurance to mine. I supported him towards the cave; but the slowness with which we proceeded was such, that it was near evening before we arrived at it. When we came to it, I placed him on my rude couch, and departed in search of food for him and myself. I had much difficulty in doing this, for even the wretched fare on which since being cast on the island I had subsisted, was scanty. When I returned, he was asleep, and I sat down to watch by him.

I have not an idea what it was that induced me at the time to concern myself about the welfare of one, whom I had such reason to detest as this man. It is one of those contradictions which so strongly marked all my actions, and which will ever characterize the proceedings of one of acute feelings and ungoverned passions.

For several days I continued to watch over him, with the attention of a brother; but he was sinking rapidly, and I saw that a very short period would put an end to his existence. During the whole time, he had never spoken; but on the day of his death he broke his silence. He asked why I had attended to his wants, and why I had not rather hastened to wreak my vengeance on him. I would not suffer him to talk long, for he was too feeble to bear the least exertion without injury. But the expression of his countenance spoke for him. His eyes rolled with a wild and frenzied gaze; his features were, by fits, twisted and convulsed with agony, and smothered and lengthened groans burst from him. The evening drew on, and the scene was still more dreadful, by the uncertain and fading light that prevailed. Suddenly he started; he gazed at me, and asked, in a voice which pierced me to the soul, “if I could forgive him?” did forgive him; God is my witness how sincerely at that moment I forgave every injury, every offence which he had committed against me. He spoke not again. Two hours afterwards, he caught my hand-he pressed it fervently, and his dying look was such as I can never forget. Although I shall live till the last convulsion of the universe shall bury me in the ashes of the world, that look can never be effaced from my memory.

It was night. I could not remove the body till morning, and the deep silence rendered my situation doubly horrible. The next morning I buried the remains of him, who, while living, had been my direst foe. But every thought of that nature had now departed; my injuries and my thoughts of revenge were alike forgotten. I shortly after left the island: I was taken up by a ship passing near to it, and conveyed again to inhabited countries. Such was the termination of my labours, my sufferings, my hopes, and my fears. When I reflect on the time which was consumed in this fruitless pursuit of revenge, it seems like one of those frightful dreams from which we start in terror, but even when awake feel horror at the thought. The inconsistencies of which I was guilty, more forcibly urge this idea;-while I spent years of loathsome and anxious labours in seeking for that gift, which, when obtained, is a curse to the possessor, I never thought of the probability, that the object of my hatred might die long before I had discovered the secret of which I was in quest. Such is the contradictory conduct of one, over whose actions reason no longer retains any controul.

I am now a lone and solitary being-isolated from the rest of my species, for the social tie which binds man to the world, and connects him with his fellow creatures, cannot long subsist without equality. I mean not the mere equality of birth or fortune. I have, as it were, acquired a nature different from the rest of mankind. The spring of my affections is dried up. Should I strive to acquire friends, to what purpose were it? I should see them drop silently and gradually into the grave, conscious that I was doomed to linger out an eternity. I care not for fame; wealth lias no channs for me, for it b in my power to an unlimited extent I most wander about, alike destitnte of hope and of fear, of pleasure or of pain. I look on the paat widi diflgust and inquietude ; I regard the future with apathy and UstleBsness. It may seem egotism in me thus to intrude my personid feelings, but it is thus only that I can convey an idea of the misery, which attends the acquisition of powers, which nature has, for wise purposes, hidden from the. grasp df mortals. Thus only can I hope* to deter other rash and daring sptrite from a like course, by showing the utter and abandoned solitariness, the exhaustion of mental and bodily fitculties, and the dead and torpid desolation of spirit, ‘ which ia the unceasing companion of the Wanderings of an Immortal.

January 14, 2025

Winter Tales: Jean Bouchon

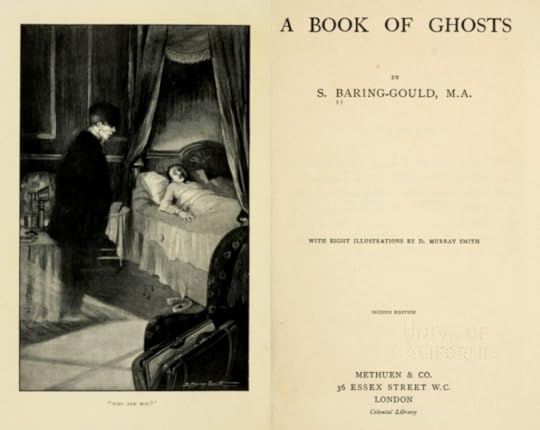

Sabine Baring-Gould an English Anglican priest, author, and folklorist, born on 1834 in Exeter, Devon, and I already featured one of his works during last year’s Advent Calendar. Topday’s story, “Jean Bouchon”, featured in his collection A Book of Ghosts, published in 1904. The anthology featured 21 short stories, each exploring various supernatural themes and experiences and combining humour and morality with an eerie atmosphere. Some notable tales in the collection include “The Leaden Ring” and “The Mother of Pansies”, which I might publish in the nearby future.

The first edition featured eight illustrations by D. Murray Smith.

The scan of the book is over here.

The scan of the book is over here.I was in Orléans a good many years ago. At the time it was my purpose to write a life of Joan of Arc, and I considered it advisable to visit the scenes of her exploits, so as to be able to give to my narrative some local colour.

But I did not find Orléans answer to my expectations. It is a dull town, very modern in appearance, but with that measly and decrepit look which is so general in French towns. There was a Place Jeanne d’Arc, with an equestrian statue of her in the midst, flourishing a banner. There was the house that the Maid had occupied after the taking of the city, but, with the exception of the walls and rafters, it had undergone so much alteration and modernisation as to have lost its interest. A museum of memorials of la Pucelle had been formed, but possessed no genuine relics, only arms and tapestries of a later date.

The city walls she had besieged, the gate through which she had burst, had been levelled, and their places taken by boulevards. The very cathedral in which she had knelt to return thanks for her victory was not the same. That had been blown up by the Huguenots, and the cathedral that now stands was erected on its ruins in 1601.

There was an enormous figure of Jeanne on the clock—never wound up—upon the mantelshelf in my room at the hotel, and there were chocolate figures of her in the confectioners’ shop- windows for children to suck. When I sat down at 7 p.m. to table d’hôte, at my inn, I was out of heart. The result of my exploration of sites had been unsatisfactory; but I trusted on the morrow to be able to find material to serve my purpose in the municipal archives of the town library.

My dinner ended, I sauntered to a cafe.

That I selected opened on to the Place, but there was a back entrance near to my hotel, leading through a long, stone-paved passage at the back of the houses in the street, and by ascending three or four stone steps one entered the long, well-lighted café. I came into it from the back by this means, and not from the front.

I took my place and called for a café-cognac. Then I picked up a French paper and proceeded to read it—all but the feuilleton. In my experience I have never yet come across anyone who reads the feuilletons in a French paper; and my impression is that these snippets of novel are printed solely for the purpose of filling up space and disguising the lack of news at the disposal of the editors. The French papers borrow their information relative to foreign affairs largely from the English journals, so that they are a day behind ours in the foreign news that they publish.

Whilst I was engaged in reading, something caused me to look up, and I noticed standing by the white marble-topped table, on which was my coffee, a waiter, with a pale face and black whiskers, in an expectant attitude.

I was a little nettled at his precipitancy in applying for payment, but I put it down to my being a total stranger there; and without a word I set down half a franc and a ten centimes coin, the latter as his pourbaire. Then I proceeded with my reading.

I think a quarter of an hour had elapsed, when I rose to depart, and then, to my surprise, I noticed the half-franc still on the table, but the sous piece was gone.

I beckoned to a waiter, and said: ‘ One of you came to me a little while ago demanding payment. I think he was somewhat hasty in pressing for it; however, I set the money down, and the fellow has taken the tip, and has neglected the charge for the coffee.”

“Sapristi!” exclaimed the garçon; ‘Jean Bouchon has at his tricks again.” I said nothing further; asked no questions. The matter did not concern me, or indeed interest me in the smallest degree; and I left.

Next day I worked hard in the town library. I cannot say that I lighted on any unpublished documents that might serve my purpose.

I had to go through the controversial literature relative to whether Jeanne d’Arc was burnt or not, for it has been maintained that a person of the same name, and also of Arques, died a natural death some time later, and who postured as the original warrior-maid. I read a good many monographs on the Pucelle, of various values; some real contributions to history, others mere second-hand cookings-up of well-known and often-used material. The sauce in these latter was all that was new.

In the evening, after dinner, I went back to the same café and called for black coffee with a nip of brandy. I drank it leisurely, and then retreated to the desk where I could write some letters.

I had finished one, and was folding it, when I saw the same pale-visaged waiter standing by with his hand extended for payment. I put my hand into my pocket, pulled out a fifty centimes piece and a coin of two sous, and placed both beside me, near the man, and proceeded to put my letter in an envelope, which I then directed.

Next I wrote a second letter, and that concluded, I rose to go to one of the tables and to call for stamps, when I noticed that again the silver coin had been left untouched, but the copper piece had been taken away.

I tapped for a waiter. “Tiens,” said I, “that fellow of yours has been bungling again. He has taken the tip and has left the half-franc.”

“Ah! Jean Bouchon once more!”

“But who is Jean Bouchon?”

The man shrugged his shoulders, and, instead of answering my query, said: “I should recommend monsieur to refuse to pay Jean Bouchon again—that is, supposing monsieur intends revisiting this café.”

“I most assuredly will not pay such a noodle,” I said; “and it passes my comprehension how you can keep such a fellow on your staff”

I revisited the library next day, and then walked by the Loire, that rolls in winter such a full and turbid stream, and in summer, with a reduced flood, exposes gravel and sand-banks. I wandered around the town, and endeavoured vainly to picture it, enclosed by walls and drums of towers, when on April 29th, 1429, Jeanne threw herself into the town and forced the English to retire, discomfited and perplexed.

In the evening I revisited the café and made my wants known as before. Then I looked at my notes, and began to arrange them.

Whilst thus engaged I observed the waiter, named Jean Bouchon, standing near the table in an expectant attitude as before. I now looked him full in the face and observed his countenance. He had puffy white cheeks, small black eyes, thick dark mutton-chop whiskers, and a broken nose. He was decidedly an ugly man, but not a man with a repulsive expression of face.

“No,” said I, “I will give you nothing. I will not pay you. Send another garçon to me.” As I looked at him to see how he took this refusal, he seemed to fall back out of my range, or, to be more exact, the lines of his form and features became confused. It was much as though I had been gazing on a reflection in still water; that something had ruffled the surface, and all was

broken up and obliterated. I could see him no more. I was puzzled and a bit startled, and I rapped my coffee-cup with the spoon to call the attention of a waiter. One sprang to me immediately.

“See!” said I, “Jean Bouchon has been here again; I told him that I would not pay him one sou, and he has vanished in a most perplexing manner. I do not see him in the room.”

“No, he is not in the room.”

“When he comes in again, send him to me. I want to have a word with him.” The waiter looked confused, and replied: “I do not think that Jean will return.”

“How long has he been on your staff?”

“Oh! he has not been on our staff for some years.”

“Then why does he come here and ask for payment for coffee and what else one may order?”

“He never takes payment for anything that has been consumed. He takes only the tips.”

“But why do you permit him to do that?”

“We cannot help ourselves.”

“He should not be allowed to enter the café.”

“No one can keep him out.”

“This is surpassing strange. He has no right to the tips. You should communicate with the police.”

The waiter shook his head. “They can do nothing. Jean Bouchon died in 1869.”

“Died in 1869!” I repeated.

“It is so. But he still comes here. He never pesters the old customers, the inhabitants of the town—only visitors, strangers.”

“Tell me all about him.”

Monsieur must pardon me now. We have many in the place, and I have my duties.”

“In that case I will drop in here to-morrow morning when you are disengaged, and I will ask you to inform me about him. What is your name?”

“At monsieur’s pleasure—Alphonse.”

Next morning, in place of pursuing the traces of the Maid of Orleans, I went to the café to hunt up Jean Bouchon. I found Alphonse with a duster wiping down the tables. I invited him to a table and made him sit down opposite me. I will give his story in substance, only where advisable recording his exact words.

Jean Bouchon had been a waiter at this particular café. Now in some of these establishments the attendants are wont to have a box, into which they drop all the tips that are received; and at the end of the week it is opened, and the sum found in it is divided pro rata among the waiters, the head waiter receiving a larger portion than the others. This is not customary in all such places of refreshment, but it is in some, and it was so in this café. The average is pretty constant, except on special occasions, as when a fête occurs; and the waiters know within a few francs what their perquisites will be.

But in the café where served Jean Bouchon the sum did not reach the weekly total that might have been anticipated; and after this deficit had been noted for a couple of months the waiters were convinced that there was something wrong, somewhere or somehow. Either the common box was tampered with, or one of them did not put in his tips received. A watch was set, and it was discovered that Jean Bouchon was the defaulter. When he had received a gratuity, he went to the box, and pretended to put in the coin, but no sound followed, as would have been the case had one been dropped in.

There ensued, of course, a great commotion among the waiters when this was discovered. Jean Bouchon endeavoured to brave it out, but the patron was appealed to, the case stated, and he was

dismissed. As he left by the back entrance, one of the younger garçons put out his leg and tripped Bouchon up, so that he stumbled and fell headlong down the steps with a crash on the stone floor of the passage. He fell with such violence on his forehead that he was taken up insensible. His bones were fractured, there was concussion of the brain, and he died within a hew hours without recovering consciousness.

“We were all very sorry and greatly shocked,” said “we did not like the man, he had dealt dishonourably by us, but we wished him no ill, and our resentment was at an end when he was dead. The waiter who had tripped him up was arrested, and was sent to prison for some months, but the accident was due to une mauvaise plaisanterie and no malice was in it, so that the young fellow got off with a light sentence. He afterwards married a widow with a café at Vierzon, and is there, I believe, doing well.

“Jean Bouchon was buried,” continued Alphonse; “and we waiters attended the funeral and held white kerchiefs to our eyes. Our head waiter even put a lemon into his, that by squeezing it he might draw tears from his eyes. We all subscribed for the interment, that it should be dignified—majestic as becomes a waiter.”

“And do you mean to tell me that Jean Bouchon has haunted this café ever since?”

“Ever since 1869,” replied Alphonse.

“And there is no way of getting rid of him?”

“None at all, monsieur. One of the Canons of Bourges came in here one evening. We did suppose that Jean Bouchon would not approach, molest an ecclesiastic, but he did. He took his pourboire and left the rest, just as he treated monsieur. Ah! monsieur! but Jean Bouchon did well in 1870 and 1871 when those pigs of Prussians were here in occupation. The officers came nightly to our café, and Jean Bouchon was greatly on the alert. He must have carried away half of the gratuities they offered. It was a sad loss to us.”

“This is a very extraordinary story,” said I.

“But it is true,” replied Alphonse.

Next day I left Orléans. I gave up the notion of writing the life of Joan of Arc, as I found that there was absolutely no new material to be gleaned on her history—in fact, she had been thrashed out.

Years passed, and I had almost forgotten about Jean Bouchon, when, the other day, I was in Orleans once more, on my way south, and at once the whole story recurred to me.

I went that evening to the same café. It had been smartened up since I was there before. There was more plate glass, more gilding; electric light had been introduced, there were more mirrors, and there were also ornaments that had not been in the café before.

I called for café-cognac and looked at a journal, but turned my eyes on one side occasionally, on the look-out for Jean Bouchon. But he did not put in an appearance. I waited for a quarter of an hour in expectation, but saw no sign of him.

Presently I summoned a waiter, and when he came up I inquired: “But where is Jean Bouchon?”

“Monsieur asks after Jean Bouchon?” The man looked surprised.

“Yes, I have seen him here previously. Where is he at present?”

“Monsieur has seen Jean Bouchon? Monsieur perhaps knew him. He died in 1869.”

“I know that he died in 1869, but I made his acquaintance in 1874. I saw him then thrice, and he accepted some small gratuities of me.”

“Monsieur tipped Jean Bouchon?”

“Yes, and Jean Bouchon accepted my tips.”

“Tiens, and Jean Bouchon died five years before.”

“Yes, and what I want to know is how you have rid yourselves of Jean Bouchon, for that you have cleared the place of him is evident, or he would have been pestering me this evening.” The man looked disconcerted and irresolute.

“Hold,” said I; “is Alphonse here?”

“No, monsieur, Alphonse has left two or three years ago. And monsieur saw Jean Bouchon in r874. I was not then here. I have been here only six years.”

“But you can in all probability inform me of the manner of getting quit of Jean.”

“Monsieur! I am very busy this evening, there are so many gentlemen come in.”

“I will give you five francs if you will tell me all—all—succinctly about Jean Bouchon.”

“Will monsieur be so good as to come here to-morrow during the morning? and then I place myself at the disposition of monsieur.”

“I shall be here at eleven o’clock.”

At the appointed time I was at the café. If there is an institution that looks ragged and dejected and dissipated, it is a café in the morning, when the chairs are turned upside-down, the waiters are in aprons and shirt-sleeves, and a smell of stale tobacco lurks about the air, mixed with various other unpleasant odours.

The waiter I had spoken to on the previous evening was looking out for me. I made him seat himself at a table with me. No one else was in the saloon except another garçon, who was dusting with a long feather-brush.

“Monsieur,” began the waiter, “I will tell you the whole truth. The story is curious, and perhaps everyone would not believe it, but it is well documetée. Jean Bouchon was at one time in service here. We had a box. When I say we, I do not mean myself included, for I was not here at the time.”

“I know about the common box. I know the story down to my visit to Orleans in 1874, when I saw the man.”

“Monsieur has perhaps been informed that he was buried in the cemetery?”

“I do know that, at the cost of his fellow-waiters.”

“Well, monsieur, he was poor, and his fellow-waiters, though well-disposed, were not rich. So he did not have a grave en perpétuité Accordingly, after many years, when the term of consignment was expired, and it might well be supposed that Jean Bouchon had mouldered away, his grave was cleared out to make room for a fresh occupant. Then a very remarkable discovery was made. It was found that his corroded coffin was crammed—literally stuffed—with five and ten centimes pieces, and with them were also some German coins, no doubt received from those pigs of Prussians during the occupation of Orleans. This discovery was much talked about. Our proprietor of the café and the head waiter went to the mayor and represented to him how matters stood—that all this money had been filched during a series of years since 1869 from the waiters. And our patron represented to him that it should in all propriety and justice be restored to us. The mayor was a man of intelligence and heart, and he quite accepted this view of the matter, and ordered the surrender of the whole coffin-load of coins to us, the waiters of the café.”

“So you divided it amongst you.”

“Pardon, monsieur; we did not. It is true that the money might legitimately be regarded as belonging to us. But then those defrauded, or most of them, had left long ago, and there were among us some who had not been in service in the café more than a year or eighteen months. We could not trace the old waiters. Some were dead, some had married and left this part of the

country. We were not a corporation. So we held a meeting to discuss what was to be done with the money. We feared, moreover, that unless the spirit of Jean Bouchon were satisfied, he might continue revisiting the café and go on sweeping away the tips. It was of paramount importance to please Jean Bouchon, to lay out the money in such a manner as would commend itself to his feelings. One suggested one thing, one another. One proposed that the sum should be expended on masses for the repose of Jean’s soul. But the head waiter objected to that. He said that he thought he knew the mind of Jean Bouchon, and that this would not commend itself to it. He said, did our head waiter, that he knew Jean Bouchon from head to heels. And he proposed that all the coins should be melted up, and that out of them should be cast a statue of Jean Bouchon in bronze, to be set up here in the café, as there were not enough coins to make one large enough to be erected in a Place. If monsieur will step with me he will see the statue; it is a superb work of art.”

He led the way, and I followed.

In the midst of the café stood a pedestals and on this basis a bronze figure about four feet high. It represented a man reeling backward, with a banner in his left hand, and the right raised towards his brow, as though he had been struck there by a bullet. A sabre, apparently fallen from his grasp, lay at his feet. I studied the face, and it most assuredly was utterly unlike Jean Bouchon with his puffy cheeks, mutton-chop whiskers, and broken nose, as I recalled him.

“But,” said I,” the features do not—pardon me—at all resemble those of Jean Bouchon. This might be the young Augustus, or Napoleon I. The profile is quite Greek.”

“It may be so,” replied the waiter. “But we had no photograph to go by. We had to allow the artist to exercise his genius, and, above all, we had to gratify the spirit of Jean Bouchon.”

“I see. But the attitude is inexact. Jean Bouchon fell down the steps headlong, and this represents a man staggering backwards.”

“It would have been inartistic to have shown him precipitated forwards; besides, the spirit of Jean might not have liked it.”

“Quite so. I understand. But the flag?”

“That was an idea of the artist. Jean could not be made holding a coffee-cup. You will see the whole makes a superb subject. Art has its exigencies. Monsieur will see underneath is an inscription on the pedestal.”

I stooped, and with some astonishment read—

“JEAN BOUCHON

MORT SUR LE CHAMP DR GLOIRE 1870

DULCE ET DECORUM EST PRO PATRIA MORI.”

“Why!” objected I,” he died from falling a cropper in the back passage, not on the field of glory.”

“Monsieur! all Orleans is a field of glory. Under S. Aignan did we not repel Attila and his Huns in 451? Under Jeanne d’Arc did we not repulse the English—monsieur will excuse the allusion—in 1429. Did we not recapture Orleans from the Germans in November, 1870?”

“That is all very true,” I broke in. “But Jean Bouchon neither fought against Attila nor with la Pucelle, nor against the Prussians. Then ‘Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori’ is rather strong, considering the facts.”

“How? Does not monsieur see that the sentiment is patriotic and magnificent?”

“I admit that, but dispute the application.”

“Then why apply it? The sentiment is all right.”

“But by implication it refers to Jean Bouchon, who died, not for his country, but in a sordid coffee-house brawl. Then, again, the date is wrong. Jean Bouchon died in 1869, not in 1870.”

“That is only out by a year.”

“Yes, but with this mistake of a year, and with the quotation from Horace, and with the attitude given to the figure, anyone would suppose that Jean Bouchon had fallen in the retaking of Orleans from the Prussians.”

“Ah! monsieur, who looks on a monument and expects to find thereon the literal truth relative to the deceased?”

“This is something of a sacrifice to truth,” I demurred.

“Sacrifice is superb!” said the waiter. “There is nothing more noble, more heroic than sacrifice.”

“But not the sacrifice of truth.”

“Sacrifice is always sacrifice.”

“Well,” said I, unwilling further to dispute, “this is certainly a great creation out of nothing”

“Not out of nothing; out of the coppers that Jean Bouchon had filched from us, and which choked up his coffin.”

“Jean Bouchon has been seen no more?”

“No, monsieur. And yet—yes, once, when the statue was unveiled. Our patron did that. The café was crowded. All our habitués were there. The patron made a magnificent oration; he drew a superb picture of the moral, intellectual, social, and political merits of Jean Bouchon. There was not a dry eye among the audience, and the speaker choked with emotion. Then, as we stood in a ring, not too near, we saw—I was there and I distinctly saw, so did the others—Jean Bouchon standing with his back to us, looking intently at the statue of himself. Monsieur, as he thus stood I could discern his black mutton-chop whiskers projecting upon each side of his head. Well, sir, not one word was spoken. A dead silence fell upon all. Our patron ceased to speak, and wiped his eyes and blew his nose. A sort of holy awe possessed us all. Then, after the lapse of some minutes, Jean Bouchon turned himself about, and we all saw his puffy pale cheeks, his thick sensual lips, his broken nose, his little pig’s eyes. He was very unlike his idealised portrait in the statue; but what matters that? It gratified the deceased, and it injured no one. Well, monsieur, Jean Bouchon stood facing us, and he turned his head from one side to another, and gave us all what I may term a greasy smile. Then he lifted up his hands as though invoking a blessing on us all, and vanished. Since then he has not been seen.”

January 13, 2025

#MermaidMonday: A Water Witch (2)

…continuing from last week.

After lunch Freda did not seem willing to go out again, so, as I was there to companion her, we both settled down to needlework and a book for alternate reading aloud. The reading, however, languished; when it came to Freda’s turn she tired quickly, lost her place twice and again, and seemed unable to fix her attention on the printed page. Was she listening, I wondered later. When silence fell between us, I became aware of a sound recurring at irregular intervals, the sound of water dropping. I looked up at the ceiling expecting to see a stain of wet, for the drop seemed to fall within the room, and close beside me.

“Do you hear that?” I asked. “Has anything gone wrong in the bathroom, do you think?” For we were in Freda’s snuggery, and the bathroom was overhead.

But my suggestion of overflowing taps and broken water-pipes left her cold.

“I don’t think it is from the bathroom,” she replied. “I hear it often. We cannot find out what it is.”

Directly she ceased speaking the drop fell again, apparently between us as we sat, and plump upon the carpet. I looked up at the ceiling again, but Freda did not raise her eyes from her embroidery.

“It is very odd,” I remarked, and this time she assented, repeating my words, and I saw a shiver pass over her. “I shall go upstairs to the bathroom,” I said decidedly, putting down my work. “I am sure those taps must be wrong.”

She did not object, or offer to accompany me, she only shivered again.

“Don’t be long away, Mary,” she said; and I noticed she had grown pale.

There was nothing wrong with the bathroom, or with any part of the water supply; and when I returned to the snuggery the drip had ceased. The next event was a ring at the door bell, and again Freda changed colour, much as she had done when we were driving. In that quiet place, where comers and goers are few, a visitor is an event. But I think this visitor must have been expected.

The servant announced Dr. Vickers.

Freda gave him her hand, and made the necessary introduction. This was the friend Robert said would come often to see us; but he was not at all the snuffy old scientist my fancy had pictured. He was old certainly, if it is a sign of age to be grey-haired, and I daresay there were crow’s feet about those piercing eyes of his; but when you met the eyes, the wrinkles were forgotten. They, at least, were full of youth and fire, and his figure was still upright and flat-shouldered.

We exchanged a few remarks; he asked me if I was familiar with that part of Scotland, and when I answered that I was making its acquaintance for the first time, he praised Roscawen and its neighbourhood. It suited him well, he said, when his object was to seek quiet; and I should find, as he did, that it possessed many attractions. Then he asked me if I was an Italian scholar, and showed a book in his hand, the Vita Nuova. Mrs. Larcomb was forgetting her Italian, and he had promised to brush it up for her. So, if I did not find it to be a bore to sit by, he proposed to read aloud. And, should I not know the book, he would give me a sketch of its purport, so that I could follow.

I had, of course, heard of the Vita Nuova, who has not! but my knowledge of the language in which it was written went no further than a few modern phrases, of use to a traveller. I disclaimed my ability to follow, and I imagine Dr. Vickers was not ill-pleased to find me ignorant. He took his seat at one end of the Chesterfield sofa, Freda occupying the other, still with that flush on her cheek; and after an observation or two in Italian, he opened his book and began to read.

I imagine he read well. The crisp, flowing syllables sounded very foreign to my ear, and he gave his author the advantage of dramatic expression and emphasis. Now and then he remarked in English on some difficulty in the text, or slipped in a question in Italian which Freda answered, usually by a monosyllable. She kept her eyes fixed upon her work. It was as if she would not look at him, even when he was most impassioned; but I was watching them both, although I never thought—but of course I never thought!

Presently I remembered how time was passing, and the place where letters should be laid ready for the post-bag going out. I had left an unfinished one upstairs, so I slipped away to complete and seal. This done, I re-entered softly (the entrance was behind a screen) and found the Italian lesson over, and a conversation going on in English. Freda was speaking with some animation.

“It cannot any more be called my fancy, for Mary heard it too.”

“And you had not told her beforehand? There was no suggestion?”

“I had not said a word to her. Had I, Mary?”—appealing to me as I advanced into sight.

“About what?” I asked, for I had forgotten the water incident.

“About the drops falling. You remarked on them first: I had told you nothing. And you went to look at the taps.”

“No, certainly you had not told me. What is the matter? Is there any mystery?”

Dr. Vickers answered:

“The mystery is that Mrs. Larcomb heard these droppings when everyone else was deaf to them. It was supposed to be auto-suggestion on her part. You have disproved that, Miss Larcomb, as your ears are open to them too. That will go far to convince your brother; and now we must seriously seek for cause. This Roscawen district has many legends of strange happenings. We do not want to add one more to the list, and give this modern shooting-box the reputation of a haunted house.”

“And it would be an odd sort of ghost, would it not—the sound of dropping water! But—you speak of legends of the district; do you know anything of a white woman who is said to drown cattle? Mrs. Elliott mentioned her this morning at the farm, when she told us she had lost her cow in the river.”

“Ay, I heard a cow had been found floating dead in the Pool. I am sorry it belonged to the Elliotts. Nobody lives here for long without hearing that story, and, though the wrath of Roscawen is roused against her, I cannot help being sorry for the white woman. She was young and beautiful once, and well-to-do, for she owned land in her own right, and flocks and herds. But she became very unhappy——”

He was speaking to me, but he looked at Freda. She had taken up her work again, but with inexpert hands, dropping first cotton, and then her thimble.

“She was unhappy, because her husband neglected her. He had—other things to attend to, and the charm she once possessed for him was lost and gone. He left her too much alone. She lost her health, they say, through fretting, and so fell into a melancholy way, spending her time in weeping, and in wandering up and down on the banks of Roscawen Water. She may have fallen in by accident, it was not exactly known; but her death was thought to be suicide, and she was buried at the cross-roads.”

“That was where Grey Madam shied this morning,” Freda put in.

“And—people suppose—that on the other side of death, finding herself lonely (too guilty, perhaps, for Heaven, but at the same time too innocent for Hell) she wants companions to join her; wants sheep and cows and horses such as used to stock her farms. So she puts madness upon the creatures, and also upon some humans, so that they go down to the river. They see her, so it is said, or they receive a sign which in some way points to the manner of her death. If they see her, she comes for them once, twice, thrice, and the third time they are bound to follow.”

This was a gruesome story, I thought as I listened, though not of the sort I could believe. I hoped Freda did not believe it, but of this I was not sure.

“What does she look like?” I asked. “If human beings see her as you say, do they give any account?”

“The story goes that they see foam rising from the water, floating away and dissolving, vaguely in form at first, but afterwards more like the woman she was once; and some say there is a hand that beckons. But I have never seen her, Miss Larcomb, nor spoken to one who has: first-hand evidence of this sort is rare, as I daresay you know. So I can tell you no more.”

And I was glad there was no more for me to hear, for the story was too tragic for my liking. The happenings of that afternoon left me discomforted—annoyed with Dr. Vickers, which perhaps was unreasonable—with poor Freda, whose fancies had thus proved contagious—annoyed, and here more justly, with myself. Somehow, with such tales going about, Roscawen seemed a far from desirable residence for a nervous invalid; and I was also vaguely conscious of an undercurrent I did not understand. It gave me the feeling you have when you stumble against something unexpected blindfold, or in the dark, and cannot define its shape.

Dr. Vickers accepted a cup of tea when the tray was brought to us, and then he took his departure, which was as well, seeing we had no gentleman at home to entertain him.

“So Larcomb is away again for a whole week? Is that so?” he said to Freda as he made his adieux.

There was no need for the question, I thought impatiently, as he must very well have known when he was required again to put up Captain Falkner.

“Yes, for a whole week,” Freda answered, with again that flush on her cheek; and as soon as we were alone she put up her hand, as if the hot colour burned.

…continues next week.

January 11, 2025

Niki de Saint Phalle in Milan

I already wrote about Niki de Saint Phalle this summer, in prospect of visiting her Tarot Garden with some friends, and I was very lucky not only because we could manage the visit but also because a large exhibition on her work just arrived in Milan. The show is at the Museum of Cultures (you might remember it from that Picasso exhibition I didn’t like), and it’ll stay on for another month, and it’s gorgeous from many points of view: the pieces are obviously stunning, the chronological narration works very well, and the staging is impressive.

“I’m Niki de Saint Phalle, and I create monumental sculptures.”

That’s the quote chosen to open the exhibition, and the curators will stress this aspect many times — for the Nanas, for the Tarot Garden, for the Totems — as one of the ways Saint Phalle chose to assert her autonomy as an artist: the dimension of her works.

Niki de Saint Phalle knew that in the history of art, few women had survived the chronicles as sculptors, and even fewer had dared to take their work into public spaces. You might remember what Vasari wrote about Properzia de Rossi, one of the first attested sculptors of our culture (I wrote about it here). Saint Phalle was one of these trailblazers and is now considered one of the most important artists of the 20th century, but the exhibition decides to start from her special connection to Italy, springing from a visit in Val d’Orcia. This connection will lead to the creation of her masterpiece of monumental sculpture, the Tarot Garden near Capalbio.

Her first significant contact with Italy occurred in 1957, when Saint Phalle stayed in Val d’Orcia and discovered 14th-century painting, its colours, and the modernity of a pre-Renaissance absence of perspective. This reassured the young self-taught artist, worried about her technical limitations. The small panels complementing her first displayed work are A City by the Sea and A Castle by the Lake by Stefano Di Giovanni Di Consolo, known as “the Sassetta”.

Saint Phalle might have seen them at the Pinacoteca of Siena, and some compositional elements suggest they inspired her piece Nightscape, which evokes the rolling Tuscan hills: coffee beans and pebbles glued together to represent houses or a city, with a central road branching off into a turreted detail, a few scattered trees in the Sienese style, a bicycle. The idea that it depicts the perched village of Talamone adds another layer of fascination: thirty years later, Saint Phalle returned to that stretch of coast to build her Tarot Garden in Capalbio. Her visit to Bomarzo deeply inspired her: the Sacred Wood would lay the basis for her masterpiece.

1. Public ShootingRebellious and sensitive, young Niki de Saint Phalle quickly realized that the roles assigned to women—wife, mother, homemaker—were way too restrictive. She dreamed big and found that art was the perfect way to express herself. Through a series of performances where she literally shot at a canvas, she made her explosive debut on the Paris art scene in the early ’60s.

“I was an angry young woman, but there are many young angry men and women who don’t become artists. I became an artist because I had no choice, no need to decide. It was my destiny.”

One of these performances also happened in Italy, in November 1970, when art critic Pierre Restany and gallery owner Guido Le Noci hosted a festival in Milan’s Piazza del Duomo to mark the 10th anniversary of Nouveau Réalisme. Part of this celebration was a group show at the Rotonda della Besana, where Saint Phalle displayed her work Composition à la trottinette (“Tir à la carabine”, 1961).

The real action, however, happened when Saint Phalle staged a live shooting performance at the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele. With a big crowd watching and police forming a cordon around the scene, Saint Phalle, dressed in a sleek black velvet suit and sporting a large cross necklace, took up a rifle and fired at a three-meter-high “altar” made of stuffed animals, sculptures of saints, Madonnas, and crucifixes. Red paint burst from hidden canisters behind the altar, splashing on the police, while smoke bombs filled the air. Just steps from the Duomo, her irreverence was impossible to ignore, and this wasn’t by chance as religion is one of the main targets of her early works.

2. Against the ChurchSaint Phalle’s anticlerical stance is evident in her “Cathedrals” and “Altars” series, created in the early 1960s. She was raised under strict bourgeois conventions and educated in religious institutions following a false and hypocritical Catholic morality, and this would be a good moment to remind everyone that her father tried to stick his cock into his mouth while she was eleven years old. Except the exhibition decides not to do so, God forbid we might think a young woman was right in rejecting her family’s education, right?

Following her beliefs and her personal trauma, the artist shed this oppressive cloak by destroying the symbols representing the Church’s power—long the source of centuries-old abuses not so different from the ones she was witnessing at home. To her, this series was “a cry of rage against all the horrors committed in the name of any religion.”

3. The Stance for Black Rights and the Nanas“I decided early on to become a heroine.

And who would I be?

George Sand? Joan of Arc?

A female Napoleon?”

Starting from 1963, the Civil Rights Act shook the United States and their struggle resonated deeply with Niki de Saint Phalle, who was spending those years in New York and California. From this period came works like Black Rosie (1965), The Lady Sings the Blues (1965), and Last Night I Had a Dream (1968), tributes to Rosa Parks, Billie Holiday, and Martin Luther‘s speech at the Lincoln Memorial.

The mutilated black body in The Lady Sings the Blues belongs to her series of “Crucifixions,” or “Prostitutes,” representing women sacrificed for humanity’s salvation like female messiahs. In the political context of the early 1960s United States, depicting the dismembered body of a Black woman was a bold stance. For Saint Phalle, it was about showing how that societal body was seen as “unfit” and thus marginalized.

Her stance with the Civil Rights movement wasn’t out of a white messiah complex.

Niki de Saint Phalle realized early in life the inequalities faced by women—in the family, at school, and in the art world. As a child, aside from the violence she went through herself, she watched her mother trapped in the domestic role dictated by the patriarchal society, and she decided to be a modern-day Prometheus to steal the fire of success and power from men. Her stunning piece defending the right to abortion should be hung in every hospital in the world.

The feminist classic The Second Sex (1949) by Simone de Beauvoir contributed to opening her eyes, while The White Goddess (1948) by Robert Graves showed her that it hadn’t always been this way: history had systematically erased women over centuries. She put the roles forced upon women at the centre of her work to obliterate them one by one: the mother, the sister, the nurse, the servant. One of the main institutions she shouted against was marriage, a de facto expectation her family had for her since her youth. In this regard, one of the most beautiful pieces in the exhibition is the bronze bride astride a monstrous, assembled horse. Pictures don’t do her justice.

Saint Phalle’s work, however, wasn’t only the destruction of oppressive archetypes. She created a new model through her monumental women—strong, mighty, larger than life—who weren’t passive muses but goddesses claiming their rightful share of power and opportunity. They were the Nanas.

“Communism and capitalism have failed. I think it’s time for a new matriarchal society. Do you think people would still starve if women were in charge? I can’t help but think they could create a world where I’d be happy to live.”

Initially crafted from papier-mâché and fabric, later in painted resin, the Nanas are a pop art rendition of the Great Mother from ancient myths—modern Willendorf Venuses with generous, abundant bodies and tiny heads and limbs. Over time, Niki de Saint Phalle created an entire army of these figures: feminist warriors, muses of gender equality, joyful and powerful, sexy and athletic, symbols of a society where women finally hold the reins of power.

Freed from the stereotypes that persist up to this day and glorify extreme thinness, the Nanas embody a positive, confident image of the body, celebrating its curves and roundness. Over time, the Nanas became monumental, transforming into Nana-Houses—protective spaces for dreaming and rediscovering oneself.

“How many Black figures have I made? Hundreds? Why would I, a white woman, create Black figures? I identify with all those who are marginalized, who have been persecuted in one way or another by society.”

Niki de Saint Phalle gave a voice to the most vulnerable because she believed that changing power dynamics—making space for women, respecting the sick and children—was the key to building a fairer society. She championed what had been silenced or pushed to the margins in Western culture and art. In the 1990s, she counterpointed this by creating a series titled Black Heroes, sculptures celebrating great African American athletes and musicians, including Josephine Baker, Michael Jordan, and Louis Armstrong.

4. The Tarot Garden“The Tarot Garden is a tribute to all the women who, for centuries, were denied the right to reveal their strength and creativity; and when they dared to, they were mocked, scorned, repressed, burned as witches, or confined to asylums.”

There’s a better framing of this place in my previous post, I think, but Niki de Saint Phalle started building the Tarot Garden in 1978 on land gifted by Carlo and Nicola Caracciolo, thanks to their connection with Marella Caracciolo Agnelli, a long-time friend of the artist. The park features 22 sculptures, some monumental and walkable, inspired by Tarot cards, adorned with vibrant mosaics and ceramics, and it’s structured as a path where visitors encounter dragons and princesses, monsters and priestesses. The project was self-funded, it took nearly two decades to complete and the artist’s health wasn’t any better for it, especially considering that Saint Phalle lived inside the Empress sculpture for a while.

The Tarot Garden was her Parc Güell, a testament that women can dream big and achieve the same goals male artists can dare to dream. The room the exhibition dedicates to this work is one of the most joyously vibrant of the whole complex.

5. The Book on AIDSIn the 1980s, Niki de Saint Phalle became one of the first artists to publicly advocate for AIDS patients. Considered the plague of the modern era, AIDS was claiming the lives of her friends and collaborators, but it was surrounded by stigma deeply intertwined with bigotry, false morals and demonization of the queer community. The booklet she published in 1986 was titled AIDS: You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands, and it was both joyful and informative, witty and grounded in science, explaining what AIDS is, how to protect oneself, and how to help those affected.

“All caresses are allowed. Long live love.”

Her goal was to challenge the prevailing, moralizing narratives around illness and sexuality, offering new imagery and dancing the fine line between advocating for a responsible behaviour and banning judgment against patients. The book became a voice for marginalized communities left unsupported by public institutions. Even before campaigns like ACT UP (1987) or “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” (1989), she had already found a powerful way to get her message across.

In 1990, the book was distributed to all French high schools.

6. The surfaced traumaMy biggest issue with this exhibition is how they decide to underplay the horrific abuse her father attempted on her when she was little, and the sequence of psychological abuses this spanned: the letter bringing it back, the chronic migraines it caused, the betrayed trust of her own therapist covering for her father. These are all events that aren’t mentioned. And while I get not wanting an artist to be defined merely in the shade of her trauma, I think the result leaves Saint Phalle as “just another angry girl”. One with artistic talent, mind you. But little more than a punk. Which upsets me a lot.

Take Saint Phalle’s statement picked for this room:

“For me, the movie is about showing

what no one wants to see:

with a few exceptions,

the family is an arena where we devour one another.”

What a punk thing to say!

Except she knows what she’s talking about, she’s not just “an angry girl” or an avant-garder aiming to shock the middle class, and she’s right. Years before Sophie Ann Lewis’ book Abolish the Family, a book I think everyone should read, Saint Phalle addresses the impossible contradictions of the family institution.

In the movie Daddy, co-directed with Peter Whitehead, Niki de Saint Phalle unflinchingly depicts the power struggle between genders, ending with the symbolic shooting of the father figure. Though it’s worth mentioning that Saint Phalle wrote her own mother urging her not to go watch the movie (another detail the exhibition fails to mention) the mother figure is a passive observer which takes on a guilty role. The film was praised by Jacques Lacan and Jean-Luc Godard during its Paris premiere in February 1974 and, up to this day, her final monologue chills you down to the bones.

In 1994, Saint Phalle wrote a letter to her daughter Laura, which became the book Mon Secret: the book contains the confession of the attempted rape at the hand of her father, and puts into perspective the monsters she sought refuge with since her earlier age.

7. More female archetypes: the Mami WataThe “Mami Wata”, a word derived from the English words “Mother” and “Water”, is a complex syncretic figure and if you want to know more about it, particularly in light of her contemporary significance, I suggest you read the thesis “Mami Wata, Diaspora, and Circum-Atlantic Performance” developed by Elyan Jeanine Hill for her degree Master of Arts in Culture and Performance at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Far from passively accepting cultural impositions, Mami Wata devotees appropriated

European images in order to understand outsiders and assert their right to reinterpret and reinvent

foreign customs.

More briefly, the Mami Wata is a water figure sometimes depicted as a mermaid and sometimes connected to the figure of the snake charmer, particularly through the persona of a woman who came to Europe in the late 19th century to perform in a circus as a snake charmer and whose story, so says the exhibition without providing more details, might have inspired Saint Phalle.

In the artist’s vision, the Mami Wata is the queen of the waters, a snake charmer, a fertility goddess, a greedy hoarder of wealth, vain and capricious, a tyrant to her followers, enchantress, prostitute, and jealous lover. Exotic and seductive, she’s the Statue of Liberty travelling astride a chariot of horses, a traveller who always remains a foreigner wherever she goes, and Saint Phalle feels a personal link to her.

8. The San Diego TotemsGoing back to California after the unhealthy life in the Tarot Gardens had made her health worse, Saint Phalle directs her imagination to the iconography and concepts of North and Mesoamerican indigenous cultures.

“I’ve been fascinated by Native American culture for years. I feel they have a protective spirituality and a mysterious brilliance, and they are part of our Californian roots. After the Tarot Garden, it felt natural to be drawn to another form of spiritual art, so connected to Mother Earth and the Universe.”

She created Queen Califia’s Magical Circle, a sculpture park honouring Queen Califia, another victorious female figure astride a mythical creature. Califia was the mythical founder of California—beautiful, fierce, and leading a band of warrior women.

One of her final series, Skulls, reflects her way of addressing aging. Just a few years before Damien Hirst would shake the art word with his For the Love of God, her skulls shimmer and sparkle. Like the Mesoamerican peoples, she viewed death as a celebration rather than a fear, writing in one of her final works: “La Mort n’existe pas. Life is eternal.”

January 10, 2025

Winter Tales: The Black Stone Statue

Mary Elizabeth Counselman (November 19, 1911 – November 13, 1995) was an American writer known for her contributions to horror, fantasy, and science fiction. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, she began writing at a young age, selling her first poem at just six years old and then proceeded to attend both the University of Alabama and the Alabama College (now the University of Montevallo), where she honed her writing skills.

“The Black Stone Statue,” today’s feature, is a short story that first appeared in Weird Tales magazine in December 1937. The narrative revolves around themes of greed, art, and the supernatural. This is how it was presented in the magazine:

An amazing tale of weird sculpture—the story of a weird deception

practised on the world by an obscure artist—by the

author of “The Three Marked Pennies”

Enjoy.

DIRECTORS,

Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston, Mass.

Gentlemen:

Today I have just received aboard the S. S. Madrigal your most kind cable, praising my work and asking— humbly, acclaim, weariness with poverty and the as one might ask it of a true genius!—if I would do a statue of myself to be placed among the great in your illustrious museum. Ah, gentlemen, that cablegram was to me the last turn of the screw!

I despise myself for what I have done in the name of art. Greed for money and contempt of my inferiors, hatred for a world that refused to see any merit in my work: these things have driven me to commit a series of strange and terrible crimes.

In these days I have thought often of suicide as a way out—a coward’s way, leaving me the fame I do not deserve. But since receiving your cablegram, lauding me for what I am not and never could be, I am determined to write this letter for the world to read. It will explain everything. And having written it, I shall then atone for my sin in (to you, perhaps) a horribly ironic manner but (to me) one that is most fitting.

Let me go back to that miserable sleet-lashed afternoon as I came into the hall of Mrs. Bates’s rooming-house—a crawling, filthy hovel for the poverty-stricken, like myself, who were too proud to go on relief. When I stumbled in, drenched and dizzy with hunger, our landlady’s ample figure was blocking the hallway. She was arguing with a tall, shabbily dressed young man whose face I was certain I had seen somewhere before.

“Just a week,” his deep, pleasant voice was beseeching the old harridan. “I’ll pay you double at the end of that time, just as soon as I can put over a deal I have in mind.”

I paused, staring at him covertly while I shook the sleet from my hat-brim. Fine gray eyes met mine across the landlady’s head—haggard now, and overbright with suppressed excitement. There was strength, character, in that face under its stubble of mahogany-brown beard. There was, too, a firm set to the man’s shoulders and beautifully formed head. Here, I told myself, was someone who had lived all his life with dangerous adventure, someone whose clean-cut features, even under that growth of beard, seemed vaguely familiar to my sculptor’s-eye for detail.

“Not one day, no sirree!” Mrs. Bates had folded her arms stubbornly. A week’s rent in advance, or ye don’t step foot into one o’ my rooms!”

On impulse I moved forward, digging into my pocket. I smiled at the young man and thrust almost my last two dollars into the landlady’s hand. Smirking, she bobbed off and left me alone with the stranger.