Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 15

March 12, 2025

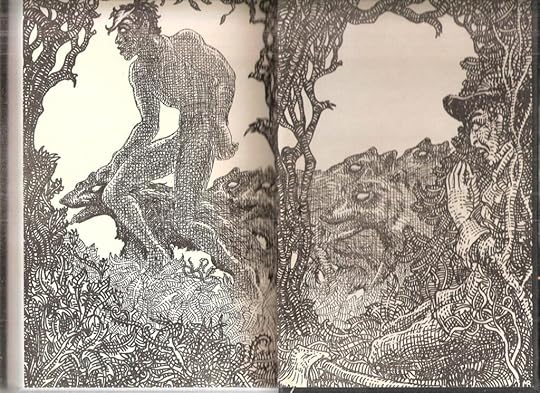

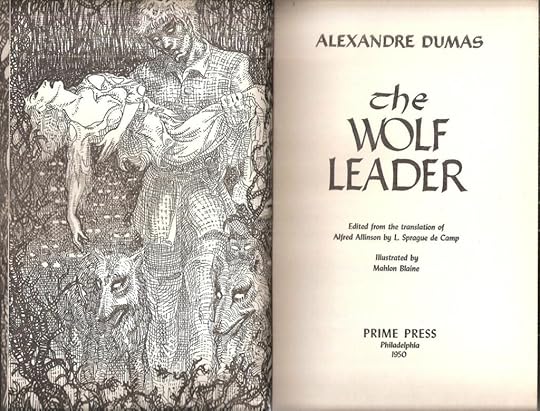

#WerewolvesWednesday: The Wolf-Leader (4)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

An illustration by Frank Adams to the British edition.Chapter IV: The Black Wolf

An illustration by Frank Adams to the British edition.Chapter IV: The Black WolfThibault’s first thought was to get himself some supper, for he was terribly tired. The past day had been an eventful one for him, and certain things that had happened were evidently enough to produce a craving for food. His supper, it must be said, was not quite as savory as he had promised himself when setting out to kill the buck. But, as we know, the animal had not been killed by Thibault, and the ferocious hunger that now consumed him made his black bread taste almost as delicious as venison.

He had hardly, however, begun his frugal repast, when he became conscious that his goat of which I think we have already spoken was uttering the most plaintive bleatings. Thinking that she, too, was in want of her supper, he went into the lean-to for some fresh grass, which he then carried to her, but as he opened the little door of the shed, out she rushed with such precipitancy that she nearly knocked Thibault over, and without stopping to take the provender he had brought her, ran towards the house. Thibault threw down the bundle of grass and went after her, with the intention of re-installing her in her proper place; but he found that this was more than he was able to do. He had to use all his force to get her along, for the goat, with all the strength of which a beast of her kind is capable, resisted all his efforts to drag her back by the horns, arching her back, and stubbornly refusing to move. At last, however, being vanquished in the struggle, it ended by the goat being once more shut up in her shed, but, in spite of the plentiful supper which Thibault left her with, she continued to utter the most lamentable cries. Perplexed, and cross at the same time, the shoemaker again rose from his supper and went to the shed, this time opening the door so cautiously that the goat could not escape. Once inside he began feeling about with his hands in all the nooks and corners to try and discover the cause of her alarm. Suddenly his fingers came in contact with the warm, thick coat of some other animal. Thibault was not a coward, far from it, none the less, he drew back hastily. He returned to the house and got a light, but it almost fell from his hand, when, on re-entering the shed, he recognised in the animal that had so frightened the goat, the buck of the Lord of Vez; the same buck that he had followed, had failed to kill, that he had prayed for in the devil’s name, if he could not have it in God’s; the same that had thrown the hounds out; the very same in short which had cost him such hard blows. Thibault, after assuring himself that the door was fastened, went gently up to the animal; the poor thing was either so tired, or so tame, that it did not make the slightest attempt to move, but merely gazed out at Thibault with its large dark velvety eyes, rendered more appealing than ever by the fear which agitated it.

“I must have left the door open,” muttered the shoe-maker to himself, “and the creature, not knowing where to hide itself, must have taken refuge here.” But on thinking further over the matter, it came back to him that when he had gone to open the door, only ten minutes before, for the first time, he had found the wooden bolt pushed so firmly into the staple that he had had to get a stone to hammer it back; and then, besides, the goat, which, as we have seen, did not at all relish the society of the new-comer, would certainly have run out of the shed before, if the door had been open. What was, however, still more surprising was that Thibault, looking more closely at the buck, saw that it had been fastened up to the rack by a cord.

Thibault, as we have said, was no coward, but now a cold sweat began to break out in large drops on his brow, a curious kind of a shiver ran through his body, and his teeth chattered violently. He went out of the shed, shutting the door after him, and began looking for his goat, which had taken advantage of the moment when the shoe-maker had gone to fetch a light, and ran again into the house, where she was now lying beside the hearth, having evidently quite made up her mind this time not to forsake a resting place, which, for that night at least, she found preferable to her usual abode.

Thibault had a perfect remembrance of the unholy invocation he had addressed to Satan, and although his prayer had been miraculously answered, he still could not bring himself to believe that there was any diabolic intervention in the matter.

As the idea, however, of being under the protection of the spirit of darkness filled him with an instinctive fear, he tried to pray; but when he wished to raise his hand to make the sign of the cross on his forehead, his arm refused to bend, and although up to that time he had never missed a day saying his Ave Maria, he could not remember a single word of it.

These fruitless efforts were accompanied by a terrible turmoil in poor Thibault’s brain; evil thoughts came rushing in upon him, and he seemed to hear them whispering all around him, as one hears the murmur of the rising tide, or the laughing of the winter wind through the leafless branches of the trees.

“After all,” he muttered to himself, as he sat pale, and staring before him, “the buck is a fine windfall, whether it comes from God or the Devil, and I should be a fool not to profit by it. If I am afraid of it as being food sent from the nether regions, I am in no way forced to eat it, and what is more, I could not eat it alone, and if I asked anyone to partake of it with me, I should be betrayed; the best thing I can do is to take the live beast over to the Nunnery of Saint-Remy, where it will serve as a pet for the Nuns and where the Abbess will give me a good round sum for it. The atmosphere of that holy place will drive the evil out of it, and I shall run no risk to my soul in taking a handful of consecrated crown pieces.

What days of sweating over my work, and turning my auger, it would take to earn even the quarter of what I shall get by just leading the beast to its new fold! The devil who helps one is certainly better worth than the angel who forsakes one. If my lord Satan wants to go too far with me, it will then be time enough to free myself from his claws: bless me! I am not a child, nor a young lamb like Georgine, and I am able to walk straight in front of me and go where I like. He had forgotten, unhappy man, as he boasted of being able to go where and how he liked, that only five minutes before he had tried in vain to lift his hand to his head.

Thibault had such convincing and excellent reasons ready to hand that he quite made up his mind to keep the buck, come whence it might, and even went so far as to decide that the money he received for it should be devoted to buying a wedding dress for his betrothed. For, strange to say, by some freak of memory, his thoughts would keep returning towards Agnelette; and he seemed to see her clad in a long white dress with a crown of white lilies on her head and a long veil. If, he said to himself, he could have such a charming guardian angel in his house, no devil, however strong and cunning he might be, would ever dare to cross the threshold. “So,” he went on, “there is always that remedy at hand, and if my lord Satan begins to be too troublesome, I shall be off to the grandmother to ask for Agnelette; I shall marry her, and if I cannot remember my prayers or am unable to make the sign of the cross, there will be a dear pretty little woman, who has had no traffic with Satan, who will do all that sort of thing for me.”

Having more or less re-assured himself with the idea of this compromise, Thibault, in order that the buck should not run down in value, and might be as fine an animal as possible to offer to the holy ladies, to whom he calculated to sell it, went and filled the rack with fodder and looked to see that the litter was soft and thick enough for the buck to rest fully at its ease. The remainder of the night passed without further incident, and without even a bad dream.

The next morning, my lord Baron again went hunting, but this time it was not a timid deer that headed the hounds, but the wolf which Marcotte had tracked the day before and had again that morning traced to his lair.

And this wolf was a genuine wolf, and no mistake; it must have seen many and many a year, although those who had that morning caught sight of it while on its track had noted with astonishment that it was black all over. Black or grey, however, it was a bold and enterprising beast, and promised some rough work to the Baron and his huntsmen. First started near Vertefeuille, in the Dargent covert, it had made over the plain of Meutard, leaving Fleury and Dampleux to the left, crossed the road to Ferte-Milou, and finally begun to run cunning in the Ivors coppices. Then, instead of continuing in the same direction, it doubled, returning along the same track it had come, and so exactly retracing its own steps that the Baron, as he galloped along, could actually distinguish the prints left by his horse’s hoofs that same morning.

Back again in the district of Bourg-Fontaine, he ranged the country, leading the hunt right to the very spot where the mis-adventures of the previous day had had their start, the vicinity of the shoe-maker’s hut.

Thibault, we know, had made up his mind what to do in regard to certain matters, and as he intended going over to see Agnelette in the evening, he had started work early.

You will naturally ask why, instead of sitting down to a work which brought in so little, as he himself acknowledged, Thibault did not start off at once to take his buck to the ladies of Saint-Remy.

Thibault took very good care to do nothing of the sort; the day was not the time to be leading a buck through the forest of Villers-Cotterets; the first keeper he met would have stopped him, and what explanation could he have given? No, Thibault had arranged in his own mind to leave home one evening about dusk, to follow the road to the right, then go down the sandpit lane which led into the Chemin du Pendu, and he would then be on the common of Saint-Remy, only a hundred paces or so from the Convent.

Thibault no sooner caught the first sound of the horn and the dogs, than he immediately gathered together a huge bundle of dried heather, which he hastily piled up in front of the shed, where his prisoner was confined, so as to hide the door, in case the huntsmen and their master should halt in front of his hut, as they had the day before. He then sat down again to his work, applying to it an energy unknown even to himself before, bending over the shoe he was making with an intentness which prevented him from even lifting his eyes. All at once he thought ha detected a sound like something scratching at the door; he was just going through from his lean-to to open it when the door fell back, and to Thibault’s great astonishment an immense black wolf entered the room, walking on its hind legs. On reaching the middle of the floor, it sat down after the fashion of wolves, and looked hard and fixedly at the sabot-maker.

Thibault seized a hatchet which was within reach, and in order to give a fit reception to his strange visitor, and to terrify him, he flourished the weapon above his head.

A curious mocking expression passed over the face of the wolf, and then it began to laugh.

It was the first time that Thibault had ever heard a wolf laugh. He had often heard tell that wolves barked like dogs, but never that they laughed like human beings. And what a laugh it was! If a man had laughed such a laugh, Thibault would verily and indeed have been scared out of his wits.

He brought his lifted arm down again.

“By my lord of the cloven foot,” said the wolf, in a full and sonorous voice, “you are a fine fellow! At your request, I send you the finest buck from His Royal Highness’s forests, and in return, you want to split my head open with your hatchet; human gratitude is worthy to rank with that of wolves.” On hearing a voice exactly like his own coming forth from a beast’s mouth, Thibault’s knees began to shake under him, and the hatchet fell out of his hand.

“Now then,” continued the wolf, “let us be sensible and talk together like two good friends. Yesterday you wanted the Baron’s buck, and I led it myself into your shed, and for fear it should escape, I tied it up myself to the rack. And for all this you take your hatchet to me!”

“How should I know who you were?” asked Thibault.

“I see, you did not recognise me! A nice sort of excuse to give.”

“Well, I ask you, was it likely I should take you for a friend under that ugly coat?”

“Ugly coat, indeed!” said the wolf, licking his fur with a long tongue as red as blood. “Confound you! You are hard to please. However, it’s not a matter of my coat; what I want to know is, are you willing to make me some return for the service I have done you?”

“Certainly,” said the shoe-maker, feeling rather uncomfortable! “but I ought to know what your demands are. What is it? What do you want? Speak!”

“First of all, and above all things, I should like a glass of water, for those confounded dogs have run me until I am out of breath.”

“You shall have it in a moment, my lord wolf.”

And Thibault ran and fetched a bowl of fresh, clear water from a brook which ran some ten paces from the hut. The eager readiness with which he complied with the wolf’s request betrayed his feeling of relief at getting out of the bargain so cheaply.

As be placed the bowl in front of the wolf, he made the animal a low bow. The wolf lapped up the contents with evident delight, and then stretched himself on the floor with his paws straight out in front of him, looking like a sphinx.

“Now,” he said, “listen to me.”

“There is something else you wish me to do” asked Thibault, inwardly quaking,

“Yes, a very urgent something,” replied the wolf. “Do you hear the baying of the dogs?”

“Indeed I do, they are coming nearer and nearer, and in five minutes they will be here.”

“And what I want you to do is to get me out of their way.”

“Get you out of their way! and how?” cried Thibault, who but too well remembered what it had cost him to meddle with the Baron’s hunting the day before.

“Look about you, think, invent some way of delivering me!”

“The Baron’s dogs are rough customers to deal with, and you are asking neither more nor less than that I should save your life; for I warn you, if they once get hold of you, and they will probably scent you out, they will make short work of pulling you to pieces. And now supposing I spare you this disagreeable business,” continued Thibault, who imagined that he had now got the upper hand, “what will you do for me in return?”

“Do for you in return?” said the wolf, “and how about the buck?”

“And how about the bowl of water?” said Thibault.

“We are quits there, my good sir. Let us start a fresh business altogether; if you are agreeable to it, I am quite willing.”

“Let it be so then; tell me quickly what you want of me.”

“There are folks,” proceeded Thibault, “who might take advantage of the position you are now in, and ask for all kinds of extravagant things, riches, power, titles, and what not, but I am not going to do anything of the kind; yesterday I wanted the buck, and you gave it me, it is true; to-morrow, I shall want something else. For some time past I have been possessed by a kind of mania, and I do nothing but wish first for one thing and then for another, and you will not always be able to spare time to listen to my demands. So what I ask for is, that, as you are the devil in person or someone very like it, you will grant me the fulfilment of every wish I may have from this day forth.”

The wolf put on a mocking expression of countenance. “Is that all?” he said, “Your peroration does not accord very well with your exordium.”

“Oh!” continued Thibault, “my wishes are honest and moderate ones, and such as become a poor peasant like myself. I want just a little corner of ground, and a few timbers, and planks; that’s all that a man of my sort can possibly desire.”

“I should have the greatest pleasure in doing what you ask,” said the wolf, “but it is simply impossible, you know.”

“Then I am afraid you must make up your mind to put up with what the dogs may do to you.”

“You think so, and you suppose I have need of your help, and so you can ask what you please?”

“I do not suppose it, I am sure of it.”

“Indeed! well then, look.”

“Look where,” asked Thibault.

“Look at the spot where I was,” said the wolf. Thibault drew back in horror. The place where the wolf had been lying was empty; the wolf had disappeared, where or how it was impossible to say. The room was intact, there was not a hole in the roof large enough to let a needle through, nor a crack in the floor through which a drop of water could have filtered.

“Well, do you still think that I require your assistance to get out of trouble,” said the wolf.

“Where the devil are you?”

“If you put a question to me in my real name,” said the wolf with a sneer in his voice, “I shall be obliged to answer you. I am still in the same place.”

“But I can no longer see you!”

“Simply because I am invisible.”

“But the dogs, the huntsmen, the Baron, will come in here after you?”

“No doubt they will, but they will not find me.”

“But if they do not find you, they will set upon me.”

“As they did yesterday; only yesterday you were sentenced to thirty-six strokes of the strap, for having carried off the buck; to-day, you will be sentenced to seventy-two, for having hidden the wolf, and Agnelette will not be on the spot to buy you off with a kiss.”

“Phew! what am I to do?”

“Let the buck loose; the dogs will mistake the scent, and they will get the blows instead of you.”

“But is it likely such trained hounds will follow the scent of a deer in mistake for that of a wolf?”

“You can leave that to me,” replied the voice, “only do not lose any time, or the dogs will be here before you have reached the shed, and that would make matters unpleasant, not for me, whom they would not find, but for you, whom they would.”

Thibault did not wait to be warned a second time but was off like a shot to the shed. He unfastened the buck, which, as if propelled by some hidden force, leapt from the house, ran around it, crossing the track of the wolf, and plunged into the Baisemont coppice. The dogs were within a hundred paces of the hut; Thibault heard them with trepidation; the whole pack came full force against the door, one hound after the other.

Then, all at once, two or three gave cry and went off in the direction of Baisemont, the rest of the hounds after them.

The dogs were on the wrong scent; they were on the scent of the buck, and had abandoned that of the wolf.

Thibault gave a deep sigh of relief; he watched the hunt gradually disappearing in the distance, and went back to his room to the full and joyous notes of the Baron’s horn.

He found the wolf lying composedly on the same spot as before, but how it had found its way in again was quite as impossible to discover as how it had found its way out.

…to be continued.

March 6, 2025

Among the Gnomes: Digging for Light

Chapter 7

I was now tolerably well satisfied. From the abject state of a nobody, existing only as a “subject” for scientific observation, looked upon as a hobgoblin, and doomed to vivisection prisoner of a jumping-jack, I had suddenly become somebody of importance, owing to my cleverness and to the credulity of the king. I saw myself now raised to the highest dignity in the kingdom of the gnomes, and engaged to a most amiable and charming—even if a little green—princess, and there was momentarily nothing to be desired except the discovery of the sun and the completion of my marriage.

This discovery of the sun caused me a certain uneasiness; but I hoped that the king would not continue to insist upon that condition. A considerable time had elapsed, and nothing was heard of the dwarfs or their expedition. It seemed to me not at all improbable that they had fallen into the hands of Professor Cracker, and were now bottled up in alcohol, adorning the shelves of some museum. At all events, I had not the faintest hope that even if they were to return, they would have discovered anything worth speaking of, or be able to describe it, and I therefore thought of means for persuading the king to alter the stipulation in regard to my marriage, and to permit it to take place before the discovery of the sun. This I did not think very difficult, for the king was very changeable and did not seem to know his own mind. Although, whenever he got some idea into his head, he was very stubborn and self-willed, nevertheless he was easily led by the nose by those who knew how to flatter him. His capriciousness was shown by the rashness with which he ordered my execution, and his instability by changing his mind and making me Grand Chancellor of his kingdom.

For this purpose I sought and obtained an interview with the king, and asked his consent that the marriage between myself and the princess should not be delayed. I proved to him by arguments that the sun could not do otherwise but exist, and that it was merely a question of time to discover it; that this event would perhaps not take place as soon as we wished it, but that this would make no difference to the sun. I took especial pains to explain to him that the interests of the state would suffer by my being doomed to live as a bachelor.

But the king had never studied logic, and was inaccessible to my arguments.

“I want the sun!” he cried, growing more than usually red in his face.

To this I replied—

“If your majesty will permit, we all know that life, and light, and heat come from the sun. The sunlight does not penetrate into your kingdom because the rays of the sun are refracted upon the surface of the earth; but the caloric rays of the sun penetrate through these rocks, otherwise there would be no heat and life, and everything would be cold and dead in this place. Now, as you feel the warmth within your residence, you will easily see that there must be a sun.”

“I see nothing,” answered the king. “All that you say may be as you say, but it does not enable me to perceive the sun.”

“And would it not be just as well,” I said, “if your majesty would accept my information that there is a sun? If I tell you so, you will know it, and knowledge is power.”

But the king would not agree. “I perceive,” he said, “that you tell me that there is a sun; but for all that I do not perceive the sun itself, and cannot eat it or have it deposited in my treasury.”

This stubbornness of Bimbam I. irritated me somewhat, and I said—

“All that your majesty says goes to show that the gnomes will have to travel still a long way before they will come up to our standard of science. We, the scientists of the human kingdom, do not need to acquire or possess or even to see anything, much less to eat or absorb it into our own constitution; it is quite sufficient for us to have a theory about it which is believed to be correct. This is what we consider to be real knowledge.”

“What a fools’ paradise this must be,”exclaimed the king. “In our country we enjoy that which we are and possess, and care very little about theories and opinions.”

While we were engaged in this conversation Cravatu entered, and brought the news that the three dwarfs had returned, and that everything had come out exactly as I predicted; for these imbeciles, not having sense enough to find their way back, had been found in the vicinity of the place where they had been left. All that could be made out by their incoherent speech was that they had seen something, but what that was nobody knew, for they were totally unable to describe it.

This fulfilment of my prediction raised me still higher in the estimation of the king, who, seeing that I could foretell future events, looked upon me as a kind of supernatural being, and wanted to be instructed in that art.

“It is very easy,” I answered. “If your majesty will only study logic, and, instead of directly looking at a thing, reject the evidence of your senses and begin to argue from the basis of what you assume to be true. Logic is the method of reasoning from particulars to generals, or the inferring of one general proposition from one or several particular ones; which means that instead of looking at a thing as a whole, and afterwards examining its parts and the relations in which they stand to it, we must look at some separate part and imagine the rest. It is a process of demonstrating to our own satisfaction and to the satisfaction of everyone who believes in our judgment——”

Here I was interrupted by the loud snoring of the king who had gone to sleep in his chair. The sudden stopping of my speech had the effect of awakening him. He yawned, and elongating his body to its full length, he stretched his limbs, and then went on to say—

“This is very interesting, and I want to have this method introduced in all the schools of my kingdom; but for the present the most important thing is the discovery of the sun, and I want you to discover it without further delay.”

I suggested that this might be done after my wedding; but the king sternly replied, “No sun, no marriage! That’s all.”

Being so near to the completion of my happiness, I was exceedingly grieved to see my hopes wrecked by their fulfilment being made to depend upon an impossible condition; but a happy thought struck me, and I said—

“I assure your majesty that the sun is right over our heads, and there is nothing to prevent you from seeing it as soon as you will get out of this mountain, except the atmospheric air, which, unfortunately enough, is impenetrable to your sight, while I can easily enough see through it. Under these circumstances, the only thing that can possibly be done will be to cut a hole through the air, and make a tunnel deep enough until you will reach the outer limits of the atmosphere, when there will be nothing to prevent you from seeing the sun.”

This proposal pleased the king exceedingly, and Cravatu could find no words strong enough to express his admiration of my wisdom. They both knew already enough of logic to understand that they would be able to see the sun if there were nothing to hinder them from seeing him. Accordingly orders were immediately issued that the best labourers, miners, and mechanics should be selected for the purpose of cutting a hole in what they called the “sky,” for the sky for them began there where their own element, the earth, ended.

On the very next day the work was begun. They selected a place on the very top of the Untersberg. The Pigmies drilled the holes, the Vulcani did the blasting, the Cubitali furnished the required materials, and the Sagani superintended the work, giving directions. We had the pleasure of seeing that already during the first twenty-four hours a hole of about ten feet depth and with a diameter of ten feet was made as the beginning of the tunnel for enlightenment.

Thus day by day, or, to speak more correctly, night after night, the work went on; for when it is day in our world no work is done by the gnomes, as with the beginning of sunrise they fall into a state of lethargy, from which they awaken only after the night has set in. Every night the king and the queen with her maids, the princess, myself, and the high dignitaries of the kingdom, went out to see the progress made in the work of the tunnel, and every night the hole grew deeper to a certain extent, according to the quality of the material which had to be cut; but when it began to dawn upon the surface of the earth the gnomes went to sleep and slept so well that nothing could have awakened them from their slumber.

In the meantime I considered it my duty to give great attention to the education of the gnomes, and to the development of their power of drawing inferences from things unknown. For the purpose of enabling them to distinguish the true from the false, I established schools of logic all over the country, in which all sorts of lies were taught, so as to give them a chance for using their own common sense and finding out the truth for themselves by overcoming the falsehood. Soon I was in possession of a corps of capable liars for assisting me in this work; but the education of the princess I took into my own charge.

At first Adalga did not enjoy the lessons, which is only natural, as the birth and beginning of everything is painful and difficult, but after a while she became delighted with my instructions. As my method may prove to be interesting and instructive to my compatriots engaged in pedagogical enterprises, I will illustrate it by an example.

First of all I tried to explain to the princess, by practical experiment, that a good scientist can never know anything whatever; he can only know what a thing is not, but not what it is, and from what he perceives that it is not he draws his inferences as to what it may be.

Thus, for instance, taking a stone and handing it to Adalga, I said—

“Queen of my heart! will you tell me what this is?”

“With pleasure!” she answered. “It is a stone.”

“How do you know it?”

“Because I see it.”

“Sight is deceptive,” I said. “It may be a pumpkin.”

“I do not care what it may be; I know it is a stone.”

“How can you prove it?”

“I do not need to prove it. I know it, and so does everybody who knows a stone.”

“You cannot know it,” I said, “unless you can give any rational reason for your belief.”

“I do not need to give any reasons for it. I am satisfied to know what I know.”

I saw that I could not get the better of her in this way, so I said—

“Will you have the kindness to imagine this stone to be a pumpkin?”

“Well, Mr Mulligan!” she answered, “if this gives you pleasure, I shall imagine it to be a pumpkin.”

“Now take a bite of it, my darling,” I said.

“I can’t, and you ought not to ask me anything so absurd.”

“But why can’t you?”

“Because it is too hard.”

“Exactly!” I exclaimed. “And now as you have discovered that it is too hard for being a pumpkin, you have a scientific right to infer that it is not a pumpkin and may possibly be a stone; quod erat demonstrandum.”

This way of making a simple thing very complicated, according to the strict rules of exact science, pleased the princess very much and amused her greatly. It now became necessary to show to her how we may arrive at a knowledge of universals by drawing logical inferences from particulars. For this purpose I told her that we must never trust to our reason, but only put faith into our method of reasoning. Pointing to the stocking which the princess was just knitting, I asked her what it was.

“A stocking,” she said. “I thought you knew that much already.”

“Who is going to wear it?”

“I.”

“And what are you?”

“A princess of this kingdom.”

“Do all the princesses of this kingdom wear stockings?”

“All those whom I know.”

“Very well!” I replied. “The consequence is that all the people who wear stockings are princesses of the kingdom of the gnomes.”

This seemed strange to Adalga, but she could not prove that it was not so, and I proceeded to explain to her that the power to draw logical inferences was the highest power which a scientist could possess, and that by means of logic almost anything could be proved, be it true or false. Thus I proved to her by way of an illustration, first, that white was black; secondly, that black was white; and thirdly, that there was no colour at all.

“White, my dear!” I said, “is, as everybody knows, no colour at all; for it is produced by a combination of all the prismatic colours in the same proportion as they exist in the solar ray, where each colour neutralises the other. Now, if there is no colour, there can be no light, and where no light exists everything is as black as night, and if everything is black, white must be black also, and consequently white is black.”

“Very strange!” exclaimed Adalga.

“If white is black,” I continued, “it follows that black is white, because if there is no difference between two things they must be identical. Moreover, everybody knows that black is no colour at all, but the negation of colour, and it follows that if a thing has no particular colour of any kind, it must necessarily be white.”

“Incredible!” exclaimed the princess.

“There is nothing incredible about it,” I said. “It is all very reasonable. Moreover, there is no such thing as a colour at all, for what we call by that name refers only to a certain sensation which is produced in our brains by means of certain vibrations transmitted through the retina and the optic nerve. If you look at any coloured thing in the dark you will find it to be without any colour at all. The sensations we receive are only due to certain vibrations of something unknown.”

“What is a vibration?” asked Adalga.

“Vibration,” I said, “is nothing but a certain kind of motion, and as motion per se does not exist, vibration is nothing, while that unknown thing which moves must be everything. But the existence of that unknown thing is not admitted by science, and consequently science knows nothing of everything, and of everything nothing, just as you like; and you can make nothing out of everything, and everything out of nothing, at your own pleasure.”

The princess was delighted to hear that she could now make everything out of nothing, although for the beginning it could be done only theoretically, and her repugnance to philosophical hair-splittings faded away. She continued her lessons with great diligence, and very soon I had the pleasure of seeing that she believed nothing and denied everything. A few weeks more, and I was highly gratified to find that she could no longer tell a mock-turtle from a tommy cat without entering into a long series of arguments for the purpose of proving which was which. Unfortunately, in proportion as she lost her power of perceiving the reality, while improving in the practice of logic, her own light grew more and more dim, her luminosity less, and the green colour in her sphere darker; but I considered this as a matter of only secondary importance; for it is said that beauty is a perishable thing, while wisdom remains.

Sometimes she was inclined to worry about the fading of her charms, but I reasoned her out of it, saying: “If everything is nothing, then, as a matter of course, beauty also is nothing, and it is not worth the while to worry about the loss of nothing.”

“But,” objected Adalga, “if beauty is nothing and nothing is everything, beauty is everything, and we must do all we can to preserve it.”

“Beauty,” I replied, “among our people is the outcome of fashion. If it were to become fashionable in our world to wear goitrès and hunchbacks, everybody would find it beautiful and adopt it at once; and even if he did not find it beautiful, he would pretend to find it so. Thus it often happens that everybody wears a most ridiculous article of dress, not because he thinks it beautiful, but because he thinks that others do so. In this way the people act foolish, and silently laugh at each other for being such fools.”

“This I should think to be very immoral,” objected Adalga.

“Human morality,” I replied, “is also a matter of custom. What is considered very moral among one nation or class of people is considered immoral among others. Some, for instance, regard stealing as a disgrace, others as a proof of great ingenuity. But we will not enter into these social questions. We would never come to an end. What you need for the purpose of evoluting into a higher and nobler sort of a being is, first of all, the three steps, or mental operations, by which you will proceed from particulars to generals, and from generals to still higher generalities by means of rejections and conclusions, so as to arrive at those axioms and general laws, from which we may infer, by way of synthesis, other particulars unknown to us, and perhaps placed beyond the reach of direct examination.”

“Oh my!” exclaimed the princess, and I saw that my explanation was not very clear to her; but this is excusable in a gnome, and I did not despair.

There is nothing more certain than that religious speculation without science leads to superstition; but it is also true that scientific speculation in regard to philosophical questions leads to blind materialism and insanity, if it is carried on without any religious basis, which means spiritual perception of truth. Adalga overdid the thing, because she was of an impulsive, fiery nature, and not used to self-restraint, and when I discovered the mistake it was too late to remedy it. I had taught her never to take anything for granted, and the end of it was that she doubted my words, disputed and denied everything, and always did the very contrary of what we expected her to do. It is said that a little learning is a dangerous thing, and I would add that the greater the learning the greater the folly, if at the foundation of all that imaginary knowledge there is no instinctive perception of truth, or what we call intuition.

The head of the princess became developed at the expense of her heart. The vital powers, which ought to have been distributed harmoniously through her system, went almost exclusively to furnish her intellect, and the consequence was that her head increased enormously in size, while her heart began to shrink. Her sight became dim, so that she could no longer distinguish right from wrong; her joyfulness left her; she became dissatisfied with herself and with everything; a continual scowl rested upon her face, and it was no pleasure to spend an hour in her company. Her former friends stampeded when they saw her approach.

I often tried to make her understand that at the basis of all creation there was an universal power, which has no name, but which men call God, and which those who reject that term, because they have formed a false conception of that which is beyond all human conception, might call by some other name, such as Love, Reason, All-consciousness, Divine Wisdom, etc., and that she might feel the manifestation of that power within her own soul, if she would only pay attention to it.

“Prove it,” she cried. “Prove that I have a soul, or that anybody has such a thing, and which has never been discovered by science, neither in the pineal gland nor in the big toe. Show me that soul, and let me examine it, and I will bottle it up and preserve it in the museum.”

“Soul means life,” I replied. “How can you know that you have a life, except by the fact that you are living?”

“Fiddlesticks!” exclaimed the princess. “There is no such thing as life. What seems life to you is only a phenomenon produced by the mechanical action of brain molecules, the result of indigestion.”

I was frightened to see the effects which my premature revelation of the mysteries of science had upon the princess. In vain I reminded her of the sentiments which she formerly used to have, and which were expressed in her song in the cave at the time of our first meeting. She called all these things “childish fancies,” unworthy of the serious attention of science. Alas! her study of the phenomenal side of nature would not have been objectionable if only her spiritual culture had not suffered by that; but while her intellect grew strong by overfeeding, her soul became starved to death; neither would she listen to my admonitions; she could not realise the possession of anything higher than the ever-doubting intellect, and this was probably because she was only a gnome.

One day, when I actually thought her reason was entirely gone, I said to her—

“Adalga, dear, do you know me?”

“Don’t dear me,” was her answer. “How can you ask such a foolish question? I know that I have an image of somebody on my brain, and that its name is said to be Mulligan, but whether your qualities correspond to that image or not I have not yet discovered. For all I know, the Mulligan with whom I fancy myself to be acquainted may be only a product of my own imagination.”

“It seems you love me no more?” I inquired despondently.

“What is love but an effect of the imagination?” she answered. “If I chose to fall in love with a pitchfork, and bestow my affection upon it, it will do me the same service as to love Mr Mulligan.”

“I assure you,” I said, “true love is an entirely different thing. That which you describe is only some kind of fancy.”

“Prove it,” she exclaimed, as usual; but alas! I could not prove to her that whose existence she could not experience.

To make the matter short, Adalga became so scientific as to lose all her loveliness of form and character, and became overbearing, ugly, conceited, and foolish, and the same was the case more or less with all the rest of the gnomes. The whole population became clever and cunning, but, at the same time, lying and hypocritical. Formerly they had been moved, as it were, only by one will, namely, the will of the king; now everybody wanted to rule everybody else, and nobody rule himself or be ruled by another. There was nothing but quarrels, disputes, dissensions, dissatisfaction, and selfishness; the gnomes lost their perception of truth and their light. The kingdom grew dark.

Formerly everything had been peaceful; but now it became necessary to employ force for the purpose of keeping order. Each gnome cared only for his or her own interests, and this caused fights. One of the first requirements was the establishment of a police. I soon found that the employees of the government, including the police, could not be relied upon. I therefore had to establish a corps of detectives, and employ for that purpose the greatest rascals, because it is known that “it requires a thief to catch a thief.” These detectives had again to be watched by others, and from this ensued an universal espionage, which was intolerable. Moreover, everybody seeing himself continually watched, was thereby continually reminded that it was in his power to steal, and the end of it was that the people considered it to be a great and praiseworthy act if one succeeded in stealing without getting caught.

At the time of my arrival it was the custom of the gnomes to believe everything that anybody said, but now it became fashionable never to believe anything whatever. The consequence was that each believed the other a liar; each mistrusted the other; nobody spoke the truth, if it was not in his own interest to do so. Nothing could be accomplished without bribery; crimes became numerous, and it became necessary to establish jails all over the country.

There was one curious feature noticeable, especially among the Sagani, who now constituted the great autocratic body of scientists. The more learned they became the more narrow-sighted they grew. They lost the power to open their eyes, and decided upon every question according to hearsay and fancy. Their limbs became atrophied, and their heads swollen. Some became so big-headed and top-heavy that they often lost their balance and fell down. It was especially funny to see how they tumbled about whenever one forgot himself, and by force of habit elongated his body. Finally, narrow-sightedness became so universal that a gnome without spectacles was quite a curiosity, and it has been reported that even children with spectacles upon their noses were born; but of this I have no positive proof.

To my horror, the head of the princess grew larger and stronger every day, and two hard horn-like excrescences began to appear upon it at the place where the phrenological bump of love of approbation is located. At the same time she grew exceedingly stubborn and vain. She was continually surrounded by flatterers who imposed upon her credulity. She could bear no contradiction, and nevertheless craved for disputes for the purpose of showing off her great learning. She lost her former natural dignity and self-esteem, and in its place she acquired a great deal of false pride; but her love of approbation revolted against the idea that anybody might consider her vain, and for the purpose of avoiding such a suspicion she joined gnomes of doubtful character, and went into bad company.

Let me draw a veil over the history of these sad events. Even now, although having resumed my individuality as Mr Schneider, I can look back only with deep regret upon the change that overcame the charming princess Adalga, owing to the ill-timed instruction of Mr. Mulligan. As to her father, the king, instead of comprehending the sad state of affairs of his kingdom, he took a very superficial view of it. He was delighted with the intellectual progress of the princess, and with the advancement of culture among his subjects, and he overwhelmed me with tokens of favour, calling me a public benefactor for civilising the gnomes.

Bimbam I. did not care to enter himself into the study of logic and elocution, nevertheless he did not wish to be regarded as a fool. He therefore tried to give himself an appearance of being learned, and whenever his arguments failed, he became very irascible, and lost his temper. He was excitable, but too great a lover of comfort to remain long in an excited state, and for this reason he was easily pacified. Often he would get raving mad, bucking his head against the walls; but a moment afterwards he would go to smoke his pipe, as if nothing had happened.

More and more the influence of the green frog was felt spreading through the kingdom, and there were some who claimed to have seen him wandering about the streets, spreading poisonous saliva from his mouth, from which green and red-spotted toad-stools grew. The world of the gnomes became continually more unnatural and perverted; impudence assumed the place of heroism, sophistry the mask of wisdom, lecherousness passed for love, hypocrisy paraded the streets under the garb of holiness; those who succeeded in cheating all the rest were considered the most clever; the most avaricious gnomes were said to be the most prudent; he who made the greatest noise was thought to be the most learned of all. Nor were the ladies exempt from this general degradation, for they assumed the most ridiculous fashions, putting artificial bumps on their backs and wearing tremendous balloons in the place of sleeves; they lost their simplicity, were full of affectations and whims, and to do anything whatever in a plain and natural way was considered vulgar.

But what is the use of continuing to describe conditions which everyone knows who has visited the Untersberg within the last few years? It is sufficient to say that the country of the gnomes at that time resembled to a great extent the human-animal kingdom of our days, and I would have wished to leave it if I had not considered it my duty to remain for the purpose of trying to undo some of the mischief which had ignorantly been caused by my prematurely opening the door of the palace of Lucifer.

March 5, 2025

#WerewolvesWednesday: The Wolf-Leader (3)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Illustration by Frank Adams to the British edition.Chapter III: Agnelette

Illustration by Frank Adams to the British edition.Chapter III: AgneletteThe Baron took the weapon which Engoulevent handed him, and deliberately examined the boar-spear from point to handle, without saying a word. On the handle had been carved a little wooden shoe, which had served as Thibault’s device while making the tour of France, as thereby he was able to recognise his own weapon. The Baron now pointed to this, saying to Thibault as he did so:

“Ah, ah, Master Simpleton! There is something that witnesses terribly against you! I must confess, this boar-spear smells to me uncommonly of venison—by the devil, it does! However, all I have now to say to you is this: You have been poaching, which is a serious crime; you have perjured yourself, which is a great sin. I am going to enforce expiation from you for the one and for the other, to help toward the salvation of that soul by which you have sworn.”

Whereupon, turning to the pricker, he continued: “Marcotte, strip off that rascal’s vest and shirt, tie him to a tree with a couple of the dog leashes, and give him thirty-six strokes across the back with your shoulder belt—a dozen for his perjury and two dozen for his poaching. No, I make a mistake—a dozen for poaching and two dozen for perjuring himself. God’s portion must be the largest.”

This order caused great rejoicing among the menials, who thought it good luck to have a culprit on whom they could avenge themselves for the mishaps of the day.

In spite of Thibault’s protestations, who swore by all the saints in the calender, that he had killed neither buck, nor doe, neither goat nor kidling, he was divested of his garments and firmly strapped to the trunk of a tree; then the execution commenced.

The pricker’s strokes were so heavy that Thibault, who had sworn not to utter a sound, and bit his lips to enable himself to keep his resolution, was forced at the third blow to open his mouth and cry out.

The Baron, as we have already seen, was about the roughest man of his class for a good thirty miles round, but he was not hard-hearted, and it was a distress to him to listen to the cries of the culprit as they became more and more frequent As, however, the poachers on His Highness’s estate had of late grown bolder and more troublesome, he decided that he had better let the sentence be carried out to the full, but he turned his horse with the intention of riding away, determined no longer to remain as a spectator.

As he was on the point of doing this, a young girl suddenly emerged from the underwood, threw herself on her knees beside the horse, and, lifting her large, beautiful eyes—wet with tears—to the Baron, cried:

“In the name of the God of mercy, my Lord, have pity on that man!”

The Lord of Vez looked down at the young girl. She was indeed a lovely child, hardly sixteen years of age, with a slender and exquisite figure, a pink and white complexion, and large blue eyes, soft and tender in expression. A crown of fair hair fell in luxuriant waves over her neck and shoulders, escaping from beneath the shabby little grey linen cap that vainly attempted to imprison them.

All this the Baron took in with a glance, in spite of the humble clothing of the beautiful suppliant, and as he had no dislike to a pretty face, he smiled down on the charming young peasant girl, in response to the pleading of her eloquent eyes.

But, as he looked without speaking, and all the while the blows were still falling, she cried again, with a voice and gesture of even more earnest supplication.

“Have pity, in the name of Heaven, my Lord! Tell your servants to let the poor man go, his cries pierce my heart.”

“Ten thousand fiends!” cried the Grand Master; “you take a great interest in that rascal over there, my pretty child. Is he your brother?”

“No, my Lord.”

“Your cousin?”

“No, my Lord.”

“Your lover?”

“My lover! My Lord is laughing at me.”

“Why not? If it were so, my sweet girl, I must confess I should envy him his lot.”

The girl lowered her eyes.

“I do not know him, my Lord, and have never seen him before to-day.”

“Without counting that now she only sees him wrong side before” Engoulevent ventured to put in, thinking that it was a suitable moment for a little pleasantry.

“Silence, sirrah!” said the Baron sternly. Then, once more turning to the girl with a smile.

“Really!” he said. “Well, if he is neither a relation nor a lover, I should like to see how far your love for your neighbour will let you go. Come, a bargain, pretty girl!”

“How, my Lord?”

“Grace for that scoundrel in return for a kiss.”

“Oh! with all my heart!” cried the young girl. “Save the life of a man with a kiss! I am sure that our good Cure himself would say there was no sin in that.”

And without waiting for the Baron to stoop and take for himself what he had asked for, she threw off her wooden shoe, placed her dainty little foot on the tip of the wolf-hunter’s boot, and, taking hold of the horse’s mane, lifted herself with a spring to the level of the hardy huntsman’s face. There, of her own accord, she offered him her round cheek, fresh and velvety as the down of an August peach.

The Lord of Vez had bargained for one kiss, but he took two; then, true to his sworn word, he made a sign to Marcotte to stay the execution.

Marcotte was religiously counting his strokes; the twelfth was about to descend when he received the order to stop, and he did not think it expedient to stay it from falling. It is possible that he also thought it would be as well to give it the weight of two ordinary blows, so as to make up good measure and give a thirteenth in; however that may be, it is certain that it furrowed Thibault’s houlders more cruelly than those that went before. It must be added, however, that he was unbound immediately after.

Meanwhile the Baron was conversing with the young girl.

“What is your name, my pretty one?”

“Georgine Agnelette, my Lord, my mother’s name! but the country people are content to call me simply Agnelette.”

“Ah, that’s an unlucky name, my child,” said the Baron.

“In what way my Lord?” asked the girl.

“Because it makes you a prey for the wolf, my beauty. And from what part of the country do you come, Agnelette?”

“From Preciamont, my Lord.”

“And you come alone like this into the forest, my child? that’s brave for a lambkin.”

“I am obliged to do it, my Lord, for my mother and I have three goats to feed.”

“So you come here to get grass for them?”

“Yes, my Lord.”

“And you are not afraid, young and pretty as you are?”

“Sometimes, my Lord, I cannot help trembling.”

“And why do you tremble?”

“Well, my Lord, I hear so many tales during the winter evenings about werewolves that when I find myself all alone among the trees, with no sound but the west wind and the branches creaking as it blows through them, I feel a kind of shiver run through me, and my hair seems to stand on end. But when I hear your hunting horn and the dogs crying, I feel at once quite safe again.”

The Baron was pleased beyond measure with this reply of the girl’s, and stroking his beard complaisantly, he said:

“Well, we give Master Wolf a pretty rough time of it; but, there is a way, my pretty one, whereby you may spare yourself all these fears and tremblings.”

“And how, my Lord?”

“Come in future to the Castle of Vez; no were-wolf, or any other kind of wolf, has ever crossed the moat there, except when slung by a cord on to a hazel-pole.”

Agnelette shook her head.

“You would not like to come? and why not?”

“Because I should find something worse there than the wolf.”

On hearing this, the Baron broke into a hearty fit of laughter, and, seeing their Master laugh, all the huntsmen followed suit and joined in the chorus. The fact was, that the sight of Agnelette had entirely restored the good humour of the Lord of Vez, and he would, no doubt, have continued for some time laughing and talking with Agnelette, if Marcotte, who had been recalling the dogs, and coupling them, had not respectfully reminded my Lord that they had some distance to go on their way back to the Castle. The Baron made a playful gesture of menace with his finger to the girl, and rode off followed by his train.

Agnelette was left alone with Thibault. We have related what Agnelette had done for Thibault’s sake, and also said that she was pretty.

Nevertheless, for all that, Thibault’s first thoughts on finding himself alone with the girl, were not for the one who had saved his life, but were given up to hatred and the contemplation of vengeance.

Thibault, as you see, had, since the morning, been making rapid strides along the path of evil.

“Ah! if the devil will but hear my prayer this time,” he cried, as he shook his fist, cursing the while, after the retiring huntsmen, who were just out of view, “if the devil will but hear me, you shall be

paid back with usury for all you have made me suffer this day, that I swear.”

“Oh, how wicked it is of you to behave like that!” said Agnelette, going up to him.

“The Baron is a kind Lord, very good to the poor, and always gently behaved with women.”

“Quite so, and you shall see with what gratitude I will repay him for the blows he has given me.”

“Come now, frankly, friend, confess that you deserved those blows,” said the girl, laughing.

“So, so!” answered Thibault, “the Baron’s kiss has turned your head, has it, my pretty Agnelette?”

“You, I should have thought, would have been the last person to reproach me with that kiss, Monsieur Thibault. But what I have said, I say again; my Lord Baron was within his rights.”

“What, in belabouring me with blows!”

“Well, why do you go hunting on the estates of these great lords?”

“Does not the game belong to everybody, to the peasant just as much as to the great lords?”

“No, certainly not; the game is in their woods, it is fed on their grass, and you have no right to throw your boar-spear at a buck which belongs to my lord the Duke of Orleans.”

“And who told you that I threw a boar-spear at his buck?” replied Thibault, advancing towards Agnelette in an almost threatening manner.

“Who told me? why, my own eyes, which, let me tell you, do not lie. Yes, I saw you throw your boar-spear, when you were hidden there, behind the beech-tree.”

Thibault’s anger subsided at once before the straightforward attitude of the girl, whose truthfulness was in such contrast to his falsehood.

“Well, after all,” he said, “supposing a poor devil does, once in a way, help himself to a good dinner from the superabundance of some great lord! Are you of the same mind, Mademoiselle Agnelette, as the judges who say that a man ought to be hanged just for a wretched rabbit? Come now, do you think God created that buck for the Baron more than for me?”

“God, Monsieur Thibault, has told us not to covet other men’s goods; obey the law of God, and you will not find yourself any the worse off for it!”

“Ah, I see, my pretty Agnelette, you know me then, since you call me so glibly by my name?”

“Certainly I do; I remember seeing you at Boursonnes, on the day of the fete; they called you the beautiful dancer, and stood round in a circle to watch you.”

Thibault, pleased with this compliment, was now quite disarmed.

“Yes, yes, of course,” he answered, “I remember now having seen you; and I think we danced together, did we not? but you were not so tall then as you are now, that’s why I did not recognise you at first, but I recall you distinctly now. And I remember too that you wore a pink frock, with a pretty little white bodice, and that we danced in the dairy. I wanted to kiss you, but you would not let me, for you said that it was only proper to kiss one’s vis-a-vis, and not one’s partner.”

“You have a good memory, Monsieur Thibault!”

“And do you know, Agnelette, that during these last twelve months, for it is a year since that dance, you have not only grown taller, but grown prettier too; I see you are one of those people who understand how to do two things at once.”

The girl blushed and lowered her eyes, and the blush and the shy embarrassment only made her look more charming still.

Thibault’s eyes were now turned towards her with more marked attention than before, and, in a voice, not wholly free from a slight agitation, he asked:

“Have you a lover, Agnelette?”

“No, Monsieur Thibault,” she answered, “I have never had one, and do not wish to have one.”

“And why is that? Is Cupid such a bad lad that you are afraid of him?”

“No, not that, but a lover is not at all what I want.”

“And what do you want?”

“A husband.”

Thibault made a movement, which Agnelette either did not, or pretended not to see.

“Yes,” she repeated, “a husband. Grandmother is old and infirm, and a lover would distract my attention too much from the care which I now give her; whereas, a husband, if I found a nice fellow who would like to marry me, a husband would help me to look after her in her old age, and would share with me the task which God has laid upon me, of making her happy and comfortable in her last years.”

“But do you think your husband,” said Thibault, “would be willing that you should love your grandmother more than you loved him? and do you not think he might be jealous at seeing you lavish so much tenderness upon her?”

“Oh,” replied Agnelette, with an adorable smile, “there is no fear of that, for I will manage to give him such a large share of my love and attention that he will have no cause to complain. The kinder and more patient he is with the dear old thing, the more I shall devote myself to him, the harder I shall work to make sure nothing is wanting in our little household. You see me looking small and delicate, and you doubt that I should have strength for this, but I have plenty of spirit and energy for work. And then, when the heart gives consent, one can work day and night without fatigue. Oh! how I should love the man who loved my grandmother! I promise you that she, my husband, and I—we should be three happy folks together.”

“You mean that you would be three very poor folks together, Agnelette!”

“And do you think the loves and friendships of the rich are worth a farthing more than those of the poor? At times, when I have been loving and caressing my grandmother, Monsieur Thibault, and she takes me on her lap, clasping me in her poor weak trembling arms, and puts her dear old wrinkled face against mine, I feel my cheek wet with the loving tears she sheds. I begin to cry myself, and I tell you, Monsieur Thibault, so soft and sweet are my tears that no woman or girl, be she queen or princess, has ever, even in her happiest days, known such a real joy as mine. And yet, there is no one in all the country round who is as destitute as we two are.”

Thibault listened to what Agnelette was saying without answering; his mind was occupied with many thoughts, such thoughts as are indulged in by the ambitious; but his dreams of ambition were disturbed at moments by a passing sensation of depression and disillusionment.

He, the man who had spent hours at a time watching the beautiful and aristocratic dames of the Court of the Duke of Orleans as they swept up and down the wide entrance stairs; who had often passed whole nights gazing at the arched windows of the Keep at Vez when the whole place was lit up for some festivity—he, that same man, now asked himself whether what he had so ambitiously desired—a lady of rank and a rich dwelling—would, after all, be worth as much as a thatched roof and this sweet and gentle girl called Agnelette. And it was certain that if this dear and charming little woman were to become his, he would, in turn, be envied by all the earls and barons in the countryside.

“Well, Agnelette,” said Thibault “and suppose a man like myself were to offer himself as your husband, would you accept him?”

It has been already stated that Thibault was a handsome young fellow, with fine eyes and black hair, and that his travels had left him something better than a mere workman. And it must further be borne in mind that we readily become attached to those on whom we have conferred a benefit, and Agnelette had, in all probability, saved Thibault’s life; for, under such strokes as Marcotte’s, the victim would certainly have been dead before the thirty-sixth had been given.

“Yes,” she said, “if it would be a good thing for my grandmother?”

Thibault took hold of her hand.

“Well then, Agnelette,” he said “we will speak again about this, dear child, and that as soon as may be.”

“Whenever you like, Monsieur Thibault.”

“And you will promise faithfully to love me if I marry you, Agnelette?”

“Do you think I should love any man besides my husband?”

“Never mind, I want you just to take a little oath, something of this kind, for instance; Monsieur Thibault, I swear that I will never love anyone but you.”

“What need is there to swear? the promise of an honest girl should be sufficient for an honest man.”

“And when shall we have the wedding, Agnelette?” and in saying this, Thibault tried to put his arm round her waist.

But Agnelette gently disengaged her self.

“Come and see my grandmother,” she said, “it is for her to decide about it; you must content yourself this evening with helping me up with my load of heath, for it is getting late, and it is nearly three miles from here to Preciamont.”

So Thibault helped her as desired and then accompanied her on her way home as far as the forest fence of Billemont, that is, until they came in sight of the village steeple. Before parting, he begged pretty Agnelette so earnestly for one kiss as an earnest of his future happiness that at last she consented. Then, far more agitated by this one kiss than she had been by the Baron’s double embrace, Agnelette hastened on her way, despite the load she was carrying on her head, which seemed far too heavy for so slender and delicate a creature.

Thibault stood for some time looking after her as she walked away across the moor. All the flexibility and grace of her youthful figure were brought into relief as she lifted her pretty, rounded arms to support the burden upon her head, and, silhouetted against the dark blue of the sky, she made a delightful picture.

At last, having reached the outskirts of the village, where the land dipped at that point, she suddenly disappeared, passing out of sight of Thibault’s admiring eyes. He gave a sigh and stood still, plunged in thought. But it was not the satisfaction of knowing that this sweet and good young creature might one day be his that had caused his sigh. Quite the contrary.

He had wished for Agnelette because she was young and pretty, and because it was part of his unfortunate disposition to long for everything that belonged or might belong to another. His desire to possess Agnelette had been quickened by the innocent frankness with which she had talked to him, but it had been a matter of fancy rather than of any deeper feeling—of the mind, and not of the heart.

Thibault was incapable of loving as a man ought to love when, being poor himself, he loves a poor girl. In such a case, there should be no thought, no ambition beyond the wish that his love may be returned. But it was not so with Thibault. On the contrary, the farther he walked away from Agnelette—leaving, it would seem, his good genius farther behind him with every step—the more urgently did his envious longings begin again to torment his soul.

It was dark when he reached home.

…to be continued.

March 3, 2025

#MerfolkMonday: Herbert James Draper (2)

Last week, I talked about Herbert James Draper and featured his painting A Water Baby. Today’s feature is another one of his works, called The Water Nixie from 1908, sometimes called The Water Nymph.

Herbert James Draper, The Water Nixie (1908)

Herbert James Draper, The Water Nixie (1908)The painting shares the title with a fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm, tale number 79 from Hanau in Hesse, Germany, so today you get a double feature: here’s the tale, an Aarne-Thompson type 313A where a girl and a boy employ magic to flee from danger. Enjoy!

A little brother and sister were once playing by a well, and while they were thus playing, they both fell in. A water-nix lived down below, who said, “Now I have got you, now you shall work hard for me!” and carried them off with her. She gave the girl dirty tangled flax to spin, and she had to fetch water in a bucket with a hole in it, and the boy had to hew down a tree with a blunt axe, and they got nothing to eat but dumplings as hard as stones. Then, at last, the children became so impatient that they waited until one Sunday, when the nix was at church, and ran away.

But when church was over, the nix saw that the birds were flown and followed them with great strides.

The children saw her from afar, and the girl threw a brush behind her, which formed an immense hill of bristles with thousands and thousands of spikes, over which the nix was forced to scramble with great difficulty; at last, however, she got over. When the children saw this, the boy threw behind him a comb which made a great hill of combs with a thousand times a thousand teeth, but the nix managed to keep herself steady on them and at last crossed over that. Then the girl threw behind her a looking-glass which formed a hill of mirrors, and was so slippery that it was impossible for the nix to cross it. Then she thought, “I will go home quickly and fetch my axe, and cut the hill of glass in half.”

Long before she returned, however, and had hewn through the glass, the children had escaped to a great distance, and the water-nix was obliged to betake herself to her well again.

March 2, 2025

Innovation Management: un’occhiata alla nuova ISO

Nel gennaio 2025 è stata pubblicata una nuova versione ISO 56000 sulla gestione dell’innovazione o, meglio, della prima parte della serie ovvero quella dedicata alla definizione dei concetti chiave e alla terminologia. Questa ISO è una norma relativamente giovane, la cui versione precedente risaleva al 2020, e che fa da preambolo e contestualizzazione per altre quattro nome nella serie:

ISO 56001:2024: Innovation management system — Requirements;ISO 56002:2019: Innovation management system — Guidance;ISO 56003:2019: Tools and methods for innovation partnership;ISO 56004:2019: Innovation management assessment;ISO 56007:2023: Tools and methods for managing opportunities and ideas.Sì, anche in ISO accade come in UNI o come per la metropolitana di Milano: ogni tanto un capitolo va per funghi, rimane indietro, e viene pubblicato solo dopo il successivo.

L’intera serie è uno strumento fondamentale per il BIM manager che non deve chiedere mai “ma io cosa sto facendo?”, sono una grande fan dei suoi contenuti e del suo approccio metodologico anziché prescrittivo. Ma cosa contiene quindi, cosa cambia in questa nuova versione e cosa ci raccontano queste modifiche?

Diamo un’occhiata.

2020 vs. 2025: le differenzeStruttura generale dell’indiceEntrambe le versioni della norma hanno una struttura simile, articolata nei seguenti capitoli principali:

Scope;Normative references;Terms and definitions;Fundamental concepts and innovation management principles;Annexe e Bibliography.E questa è la buona notizia.

Tuttavia, ci sono alcune differenze chiave che emergono dal confronto tra i due testi. E non sono necessariamente una cattiva notizia.

Vediamo quali.

New Entry: l’AntifragilitàLa versione 2025 introduce anche, per la gioia di molti, il concetto di antifragilità, assente nella versione del 2020. Se non vi ricordate cosa si intenda per antifragilità, provate a spulciare il tag sul blog oppure a questo post introduttivo.

Ecco come viene definito il termine nella norma:

3.2.14. antifragile: ability to gain from stressors, uncertainty (3.2.12) and risk (3.2.13)

Note 1 to entry: Stressors can be shocks, failures, disruptions, emergencies, crises, etc.

Note 2 to entry: An antifragile entity (3.2.11) can thrive and/or evolve from unexpected stressors, take advantage of uncertainty and positively assume risk.

Collaborazione ed Ecosistemi di Innovazione

Per capire come mai sia stato introdotto il concetto di antifragilità, viriamo un attimo su un’altra nuova definizione, quella di “innovation ecosystem” (3.1.3.4), un’altra novità della versione 2025. L’ecosistema di innovazione è identificato in un sistema di persone oppure di organizzazioni interdipendenti che sviluppano o consentono l’innovazione in modo collaborativo. Questo gruppo può includere organizzazioni pubbliche e private. L’ambito di un ecosistema dell’innovazione può essere definito in termini di piattaforma, insieme di tecnologie, area di conoscenza, insieme di competenze, settore, comunità o area geografica. Può essere un gruppo di partecipanti riunitosi in modo arbitrario oppure una comunità organizzata e diretta, componente più voci e che collabora sulla base di partnership.

La versione 2020 menzionava gli ecosistemi di innovazione nel contesto delle reti di valore e delle collaborazioni tra organizzazioni, ma senza una definizione strutturata. Si faceva riferimento alla collaborazione con partner esterni, ma senza specificare l’idea di ecosistema come un’entità organizzata e sistematica, probabilmente demandando alla ISO 56003: 2019 il compito di articolare e declinare i concetti nell’ambito della partnership. L’introduzione dell’ecosistema di innovazione anche nella parte introduttiva della serie sembra indicare una maturata consapevolezza che non ci possa essere innovazione senza collaborazione, e che ogni innovazione si muova nellì’ambito di un sistema complesso. La norma del 2025 distingue quindi chiaramente l’ecosistema di innovazione da altri sistemi e lo collega esplicitamente a concetti come le reti di valore e i partenariati collaborativi.

La collaborazione è fondamentale per il successo.

La collaborazione è fondamentale per il successo.Questa tendenza è avvalorata dall’espansione di altri concetti, strettamente legati all’ecosistema di innovazione, tra cui quello di “Open Innovation”.

Il concetto di open innovation era già presente nel 2020, ma decisamente meno dettagliato, mentre il termine “innovation partnership” veniva utilizzato per descrivere sforzi collaborativi tra più organizzazioni, ma senza un quadro sistematico. L’innovazione aperta si aggiunge ora alle modalità tramite le quali si può fare innovazione, insieme all’innovazione interna e all’innovazione collaborativa (sezione 4.2.2.3 Attributes describing how it is innovated, che purtroppo usa le parentesi tonde dentro ad altre parentesi tonde e mi sento male). Ricopre anche un ruolo esplicito nell’esecuzione dei processi di innovazione, forse nel disperato tentativo di evitare che le aziende reinventino ogni volta l’acqua calda pur di essere innovative, senza guardarsi intorno e cercare di capire se là fuori esistano già porzioni di soluzioni.

Nell’ambito della collaborazione, quindi, si inserisce l’espansione di un altro importante concetto, ovvero quello di “Innovation Partnership”, cui in Italia qualcuno si riferisce come “Partenariato per l’innovazione”, che non è esattamente la stessa cosa…

“Una partnership per l’innovazione può comportare l’istituzione di obiettivi congiunti di innovazione, strategie, ruoli, strutture e processi di supporto, inclusa la condivisione di risorse come finanziamenti, conoscenze e persone.”

L’innovazione collaborativa quindi veniva citata, anche nel 2020, ma senza una struttura chiara che la distinguesse dagli altri tipi di innovazione. Ora trova posto in un framework che spinge sempre di più verso concetti come questo. La gestione dell’innovazione è ora trattata come un fenomeno sistemico, con una chiara distinzione tra innovazione interna ed esterna, e la collaborazione con altre entità fa parte della rete di valore generata dall’innovazione.

Questo approccio, quindi, enfatizza alcuni aspetti chiave:

l’interdipendenza: le organizzazioni o gli individui coinvolti non operano in modo isolato, ma si influenzano a vicenda e traggono vantaggio dalle reciproche competenze e risorse;la collaborazione e il coordinamento: gli attori possono operare in modo formale o informale, attraverso partenariati, alleanze strategiche o network aperti;lo sviluppo e l’abilitazione dell’innovazione: l’ecosistema non si limita solo a creare innovazione, ma anche a fornire le condizioni e il supporto affinché l’innovazione possa emergere e diffondersi.Quando si parla di ecosistemi di innovazione, si immagina spesso una rete di aziende e istituzioni che collaborano, ma il concetto è molto più ricco e sfaccettato, quindi. Un vero ecosistema innovativo funziona come un organismo vivente (anche se più spesso si tratta di un gruppo di aziende che sta cercando di ritornare in vita combinando tra loro le uniche parti ancora funzionanti, ma questa è un’altra storia). Ogni componente dell’ecosistema dovrebbe giocare un ruolo cruciale, richiedendo quindi grande attenzione alle modalità di interazione tra gli attori e alla loro capacità di reazione ai cambiamenti (da cui la necessità di introdurre il concetto di antifragilità).

Collaborano con calma, dignità e classe.

Collaborano con calma, dignità e classe.Un ecosistema di innovazione, per rendere tutto più interessante, non è tale se si basa su una sola tipologia di attore: è la diversità a renderlo fertile e dinamico, facendo convivere realtà come:

grandi aziende che possono mettere a disposizione risorse e infrastrutture;startup e PMI, più agili laddove si tratta di testare idee e soluzioni, al contrario delle grandi aziende in cui l’introduzione del cambiamento può essere molto lenta;università e centri di ricerca, che ad esempio possono analizzare i dati a supporto delle soluzioni che stanno venendo sviluppate;istituzioni governative, che regolano e incentivano lo sviluppo;investitori e fondi di venture capital, che scommettono sulle idee più promettenti (o su quelle meno rischiose);utenti finali, che con i loro feedback indirizzano l’evoluzione delle innovazioni.Un esempio classico che viene portato come ecosistema di innovazione è Silicon Valley, che non avrebbe mai potuto fiorire senza la combinazione di università all’avanguardia come Stanford, aziende tech consolidate (Google, Apple), startup rivoluzionarie e investitori con capitali pronti a essere impiegati.

Un elemento che distingue un ecosistema di innovazione da una semplice collaborazione tra aziende, è la co-creazione, da cui la necessità di definire meglio principi come quello della proprietà intellettuale, che nella versione del 2025 della norma riceve rinnovata attenzione. La co-creazione può assumere diverse forme e passare per diverse modalità, dalla condivisione di risorse alla sperimentazione congiunta, introducendo quindi un importante cambio di paradigma potenziale: chi partecipa alla sperimentazione e alla fase di test è comunque da considerare parte attrice nello sviluppo dell’innovazione.