Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 11

May 23, 2025

KPIs and Gaming the Metrics

Earlier this week I wrote about KPIs and how we’re using them wrong, l but I fear I left something out, which is how KPIs are used in education. Nowhere is the distortion of goals by poorly chosen KPIs more visible than in the classroom. And no one can teach us to break the system better than students.

Gaming the Metrics: how does that work?In teaching BIM, AI, and other digital tools, I often see students approach assignments not with the intent to solve a problem or test a strategy, but to optimise for the assessment.

It’s okay. I’m not blaming you. It’s a rational response.

If you tell someone they’ll be evaluated on technical complexity, they will prioritise that—even if it sabotages usability, collaboration, or conceptual clarity. When a grading rubric emphasises “parametric richness,” students pile on constraints. If the focus is on visual output, they produce glossy renderings with no functional backbone. If the benchmark is a complete dataset, they’ll cram the model full of placeholder properties—empty shells of metadata that look impressive in a spreadsheet but offer no actual insight. I could go on for hours.

This isn’t laziness. It’s adaptation. And this is the classic problem of metric gaming.

In a digital design context, it leads to a surface-level performance of understanding rather than actual competence. Students quickly learn that complexity is easier to simulate than quality, especially when the evaluation system doesn’t account for context.

This is particularly risky when we’re teaching tools that will be used in high-stakes environments:

an information model cluttered with unnecessary parameters becomes a liability when it needs to be handled by third parties;a process trained on irrelevant data may automate the wrong task altogether;a dashboard full of green lights may hide critical blind spots.When we reward the wrong outcomes, we train future professionals to mimic efficiency without developing the capacity to interrogate goals or evaluate impact. In doing so, we create a culture of digital performance—impressive models, empty of strategy.

As educators, we need to stop asking: “Did they use the tool correctly?” and start asking:

“Did they make the right decisions about when, how, and why to use it at all?”

This is why KPIs in digotal education, if we must have them, should prioritise reasoning, decision-making, and clarity of intent—not just output. Digital education is not about producing the most complex object. It’s about helping students develop the critical mindset to know which complexity serves a purpose—and which is just noise. This has never been more relevant, with the rise of the obsession to catch students who are “cheating with AI”.

May 22, 2025

Anna Kavan – Ice

Oh. My. God.How come this novel isn’t up there alongside Ph. K. Dick, Asimov, and the rest of the greatest sci-fi works of our time?

Oh, yeah, it might be because it talks about violence over a woman.

This anxious, delicate masterpiece follows an unreliable, possibly schizophrenic narrator through a world ravaged with violence and unravels its gradually falling apart, while ice relentlessly advances and threatens to cover everything. How? Why? It’s not important. What’s important is the Girl, a woman the narrator is obsessed with, and whose fragility he’s morbidly attracted to. Claiming he wants to save her, he speaks of abuse and control with the same tranquility he uses in detailing the end of the world, of physical violence and the denial of autonomy, flawlessly describing her brittle bones and delicate appearance as the cause for this obsession. Obviously it’s going to be the girl’s fault. That, or the ice.I

It’s a must read.

It should be studied at school.

Ice is a novel by British writer Anna Kavan, published in 1967

May 21, 2025

Werewolves Wednesday: The Wolf-Leader (13)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter XIII: Where it is demonstrated that a Woman never speaks more eloquently than when she holds her tongueAs Thibault was talking to himself he did not catch the few hurried words which Suzanne whispered to the Baron; and all he saw was that she appeared to totter, and then fell back into her lover’s arms, as if in a dead faint.

The Bailiff stopped short as he caught sight of this curious group, lit up by his candle. He was facing Thibault, and the latter endeavoured to read in Monsieur Magloire’s face what was passing in his mind.

But the Bailiff’s jovial physiognomy was not made by nature to express any strong emotion, and Thibault could detect nothing in it but a benevolent astonishment on the part of the amiable husband.

The Baron, also, evidently detected nothing more, for with a coolness and ease of manner, which produced on Thibault a surprise beyond expression, he turned to the Bailiff, and asked:

“Well, friend Magloire, and how do you carry your wine this evening?”

“Why, is it you, my lord?” replied the Bailiff opening his fat little eyes.

“Ah! pray excuse me, and believe me, had I known I was to have the honour of seeing you here, I should not have allowed myself to appear in such an unsuitable costume.”

“Pooh-pooh! nonsense!”

“Yes, indeed, my lord; you must permit me to go and make a little toilette.”

“No ceremony, I pray!” rejoined the Baron. “After curfew, one is at least free to receive one’s friends in what costume one likes. Besides, my dear friend, there is something which requires more immediate attention.”

“What is that, my lord?”

“To restore Madame Magloire to her senses, who, you see, has fainted in my arms.”

“Fainted! Suzanne fainted! Ah! my God!” cried the little man, putting down his candle on the chimney-piece, “how ever did such a misfortune happen?”

“Wait, wait, Monsieur Magloire!” said my lord, “we must first get your wife into a more comfortable position in an armchair; nothing annoys women so much as not to be at their ease when they are unfortunate enough to faint.”

“You are right, my lord; let us first put her in the armchair… Oh Suzanne! poor Suzanne! How can such a thing as this have happened?”

“I pray you at least, my dear fellow, not to think any ill of me at finding me in your house at such a time of night!”

“Far from it, my lord,” replied the Bailiff, “the friendship with which you honour us, and the virtue of Madame Magloire are sufficient guarantees for me to be glad at any hour to have my house honoured by your presence.”

“Triple dyed idiot!” murmured the shoemaker, “unless I ought rather to call him a doubly clever dissembler… No matter which, however! we have yet to see how my lord is going to get out of it.”

“Nevertheless,” continued Maitre Magloire, dipping a handkerchief into some aromatic water, and bathing his wife’s temples with it, “nevertheless, I am curious to know how my poor wife can have received such a shock.”

“It’s a simple affair enough, as I will explain, my dear fellow. I was returning from dining with my friend, de Vi vie res, and passing through Erneville on my way to Vez, I caught sight of an open window, and a woman inside making signals of distress.”

“Ah! my God!”

“That is what I exclaimed, when I realised that the window belonged to your house; and can it be my friend the Bailiff’s wife, I thought, who is in danger and in need of help?”

“You are good indeed, my lord,” said the Bailiff quite overcome. “I trust it was nothing of the sort.”

“On the contrary, my dear man.”

“How! on the contrary?”

“Yes, as you will see.”

“You make me shudder, my lord! And do you mean that my wife was in need of help and did not call me?”

“It had been her first thought to call you, but she abstained from doing so, for, and here you see her delicacy of feeling, she was afraid that if you came, your precious life might be endangered.”

The Bailiff turned pale and gave an exclamation.

“My precious life, as you are good enough to call it, is in danger?”

“Not now, since I am here.”

“But tell me, I pray, my lord, what had happened? I would question my wife, but as you see she is not yet able to answer.”

“And am I not here to answer in her stead?”

“Answer then, my lord, as you are kind enough to offer to do so; I am listening.”

The Baron made a gesture of assent, and went on:

“So I ran to her, and seeing her all trembling and alarmed, I asked, “What is the matter, Madame Magloire, and what is causing you so much alarm?”

“Ah! my lord,” she replied, “just think what I feel, when I tell you that yesterday and to-day, my husband has been entertaining a man about whom I have the worst suspicions. Ugh! A man who has introduced himself under the pretence of friendship to my dear Magloire, and actually makes love to me, to me.”

“She told you that?”

“Word for word, my dear fellow! She cannot hear what we are saying, I hope?”

“How can she, when she is insensible?”

“Well, ask her yourself when she comes to, and if she does not tell you exactly to the letter what I have been telling you, call me a Turk, an infidel and a heretic.”

“Ah! these men! these men!” murmured the Bailiff.

“Yes, race of vipers!” continued my lord of Vez, “do you wish me to go on?”

“Yes, indeed!” said the little man, forgetting the scantiness of his attire in the interest excited in him by the Baron’s tale.

“‘But Madame,’ I said to my friend Madame Magloire, ‘How could you tell that he had the audacity to love you?'”

“Yes,” put in the Bailiff, “how did she find it out? I never noticed anything myself.”

“You would have been aware of it, my dear friend, if only you had looked under the table; but, fond of your dinner as you are, you were not likely to be looking at the dishes on the table and underneath it at the same time.”

“The truth is, my lord, we had the most perfect little supper! just you think now cutlets of young wild-boar …”

“Very well,” said the Baron, “now you are going to tell me about your supper, instead of listening to the end of my tale, a tale which concerns the life and honour of your wife!”

“True, true, my poor Suzanne! My lord, help me to open her hands, that I may slap them on the palms.”

The Lord of Vez gave all the assistance in his power to Monsieur Magloire, and by dint of their united efforts they forced open Madame Magloire’s hands.

The good man, now easier in his mind, began slapping his wife’s palms with his chubby little hands, all the while giving his attention to the remainder of the Baron’s interesting and veracious story.

“Where had I got to?” he asked.

“You had got just to where my poor Suzanne, whom one may indeed call the chaste Suzanne…”

“Yes, you may well say that!” interrupted the lord of Vez.

“Indeed, I do! You had just got to where my poor Suzanne began to be aware…”

“Ah, yes that your guest like Paris of old was wishing to make another Menelaus of you; well, then she rose from table … You remember that she did so?”

“No … I was perhaps a little just a little overcome.”

“Quite so! Well then she rose from table, and said it was time to retire.”

“The truth is, that the last hour I heard strike was eleven,” said the jovial Bailiff.

“Then the party broke up.”

“I don’t think I left the table,” said the Bailiff.

“No, but Mndame Magloire and your guest did. She told him which was his room, and Perrine showed him to it; after which, kind and faithful wife as she is, Madame Magloire tucked you into bed, and went into her own room.”

“Dear little Suzanne!” said the bailiff in a voice of emotion.

“And it was then, when she found herself in her room, and all alone, that she got frightened; she went to the window and opened it; the wind, blowing into the room, put out her candle. You know what it is to have a sudden panic come over you, do you not?”

“Oh! yes,” replied the Bailiff naively, “I am very timid myself.”

“After that she was seized with panic, and not daring to wake you, for fear any harm should come to you, she called to the first horseman she saw go by and luckily, that horseman was myself.”

“It was indeed fortunate, my lord.”

“Was it not?… I ran, I made myself known.”

“‘Come up, my lord, come up,’ she cried. ‘Come up quickly I am sure there is a man in my room.'”

“Dear! dear!…” said the bailiff, “you must indeed have felt terribly frightened.”

“Not at all! I thought it was only losing time to stop and ring; I gave my horse to l’Eveille, I stood up on the saddle, climbed from that to the balcony, and, so that the man who was in the room might not escape, I shut the window. It was just at that moment that Madame Magloire, hearing the sound of your door opening, and overcome by such a succession of painful feelings, fell fainting into my arms.”

“Ah! my lord!” said the Bailiff, “how frightful all this is that you tell me.”

“And be sure, my dear friend, that I have rather softened than added to its terror; anyhow, you will hear what Madame Magloire has to tell you when she comes to.”

“See, my lord, she is beginning to move.”

“That’s right! burn a feather under her nose.”

“A feather?”

“Yes, it is a sovereign anti-spasmodic; burn a feather under her nose, and she will revive instantly.”

“But where shall I find a feather?” asked the bailiff.

“Here! take this, the feather round my hat.” And the lord of Vez broke off a bit of the ostrich feather which ornamented his hat, gave it to Monsieur Magloire, who lighted it at the candle and held it smoking under his wife’s nose.

The remedy was a sovereign one, as the Baron had said; the effect of it was instantaneous; Madame Magloire sneezed.

“Ah!” cried the bailiff delightedly, “now she is coming to! my wife! my dear wife! my dear little wife!”

Madame Magloire gave a sigh.

“My lord! my lord!” cried the bailiff, “she is saved! saved!”

Madame Magloire opened her eyes, looked first at the Bailiff and then at the Baron, with a bewildered gaze, and then finally fixing them on the Bailiff:

“Magloire! dear Magloire!” she said, “is it really you? Oh! how glad I am to see you again after the bad dream I have had!”

“Well!” muttered Thibault, “she is a brazen-faced huzzy, if you like! If I do not get all that I want from the ladies I run after, they, at least, afford me some valuable object lessons by the way!”

“Alas! my beautiful Suzanne,” said the Bailiff, “it is no bad dream you have had, but, as it seems, a hideous reality.”

“Ah! I remember now,” responded Madame Magloire. Then, as if noticing for the first time that the lord of Vez was there:

“Ah! my lord,” she continued, “I hope you have repeated nothing to my husband of all those foolish things I told you?”

“And why not, dear lady?” asked the Baron.

“Because an honest woman knows how to protect herself, and has no need to keep on telling her husband a lot of nonsense like that.”

“On the contrary, Madame,” replied the Baron, “I have told my friend every thing.”

“Do you mean that you have told him that during the whole of supper time that man was fondling my knee under the table?”

“I told him that, certainly.”

“Oh! the wretch!” exclaimed the Bailiff.

“And that when I stooped to pick up my table napkin, it was not that, but his hand, that I came across.”

“I have hidden nothing from my friend Magloire.”

“Oh! the ruffian!” cried the Bailiff.

“And that Monsieur Magloire having a passing giddiness which made him shut his eyes while at table, his guest took the opportunity to kiss me against my will?”

“I thought it was right for a husband to know everything.”

“Oh! the knave!” cried the Bailiff.

“And did you even go so far as to tell him that having come into my room, and the wind having blown out the candle, I fancied I saw the window curtains move, which made me call to you for help, believing that he was hidden behind them?”

“No, I did not tell him that! I was going to when you sneezed.”

“Oh! the vile rascal!” roared the Bailiff, taking hold of the Baron’s sword which the latter had laid on a chair, and drawing it out of the scabbard, then, running to ward the window which his wife had

indicated, “He had better not be behind these curtains, or I will spit him like a woodcock,” and with this he gave one or two lunges with the sword against the window hangings.

But all at once the Bailiff stayed his hand, and stood as if arrested like a school boy caught trespassing out of bounds; his hair rose on end beneath his cotton night-cap, and this conjugal head-dress became agitated as by some convulsive movement. The sword dropped from his trembling hand, and fell with a clatter on the floor. He had caught sight of Thibault behind the curtains, and as Hamlet kills Polonius, thinking to slay his father’s murderer, so he, believing that he was thrusting at nothing, had nearly killed his crony of the night before, who had already had time enough to prove himself a false friend. Moreover as he had lifted the curtain with the point of the sword, the Bailiff was not the only one who had seen Thibault. His wife and the Lord of Vez had both been participators in the unexpected vision, and both uttered a cry of surprise. In telling their tale so well, they had had no idea that they were so near the truth. The Baron, too, had not only seen that there was a man, but had also recognised that the man was Thibault.

“Damn me!” he exclaimed, as he went nearer to him, “if I mistake not, this is my old acquaintance, the man with the boar-spear!”

“How! how! man with the boar-spear?” asked the Bailiff, his teeth chattering as he spoke. “Anyway I trust he has not his boar-spear with him now!” And he ran behind his wife for protection.

“No, no, do not be alarmed,” said the Lord of Vez, “even if he has got it with him, I promise you it shall not stay long in his hands. So, master poacher,” he went on, addressing himself to Thibault, “you are not content to hunt the game belonging to his Highness the Duke of Orleans, in the forest of Villers-Cotterets, but you must come and make excursions in the open and poach on the territory of my friend Maitre Magloire?”

“A poacher! do you say?” exclaimed the Bailiff. “Is not Monsieur Thibault a landowner, the proprietor of farms, living in his country house on the income from his estate of a hundred acres?”

“What, he?” said the Baron, bursting into a loud guffaw, “so he made you believe all that stuff, did he? The rascal has got a clever tongue. He! a landowner! that poor starveling! why, the only property he possesses is what my stable-boys wear on their feet the wooden shoes he gets his living by making.”

Madame Suzanne, on hearing Thibault thus classified, made a gesture of scorn and contempt, while Maitre Magloire drew back a step, while the colour mounted to his face. Not that the good little man was proud, but he hated all kinds of deceit; it was not because he had clinked glasses with a shoe-maker that he turned red, but because he had drunk in company with a liar and a traitor.

During this avalanche of abuse Thibault had stood immovable with his arms folded and a smile on his lips. He had no fear but that when his turn came to speak, he would be able to take an easy revenge. And the moment to speak seemed now to have come. In a light, bantering tone of voice which showed that he was gradually accustoming himself to conversing with people of a superior rank to his own he then exclaimed; “By the Devil and his horns! as you yourself remarked a little while ago, you can tell tales of other people, my lord, without much compunction, and I fancy if every one followed your example, I should not be at such a loss what to say, as I choose to appear!”

The lord of Vez, perfectly aware, as was the bailiffs wife, of the menace conveyed in these words, answered by looking Thibault up and down with eyes that were starting with anger.

“Oh!” said Madame Magloire, some what imprudently, “you will see, he is going to invent some scandalous tale about me.”

“Have no fear, Madame,” replied Thibault, who had quite recovered his self-possession, “you have left me nothing to invent on that score.”

“Oh! the vile wretch!” she cried, “you see, I was right; he has got some malicious slander to report about me; he is determined to revenge himself because I would not return his sheep’s-eyes, to punish me because I was not willing to warn my husband that he was paying court to me.” During this speech of Madame Suzanne’s the lord of Vez had picked up his sword and advanced threateningly towards Thibault. But the Bailiff threw himself between them, and held back the Baron’s arm. It was fortunate for Thibault that he did so, for the latter did not move an inch to avoid the blow, evidently prepared at the last moment to utter some terrible wish which would avert the danger from him; but the Bailiff interposing, Thibault had no need to resort to this means of help.

“Gently, my lord!” said the Maitre Magloire, “this man is not worthy our anger. I am but a plain citizen myself, but you see, I have only contempt for what he says, and I readily forgive him the way in which he has endeavoured to abuse my hospitality.”

Madame Magloire now thought that her moment had come for moistening the situation of affairs with her tears, and burst into loud sobs.

“Do not weep, dear wife!” said the Bailiff, with his usual kind and simple good-nature. “Of what could this man accuse you, even suppose he had some thing to bring against you! Of having deceived me? Well, I can only say, that made as I am, I feel I still have favours to grant you and thanks to render you, for all the happy days which I owe to you. Do not fear for a moment that this apprehension of an imaginary evil will alter my behaviour towards you. I shall always be kind and indulgent to you, Suzanne, and as I shall never shut my heart against you, so will I never shut my door against my friends. When one is small and of little account it is best to submit quietly and to trust; one need have no fear then but of cowards and evil-doers, and I am convinced, I am

happy to say, that they are not so plentiful as they are thought to be. And, after all, by my faith! if the bird of misfortune should fly in, by the door or by the window, by Saint Gregory, the patron of

drinkers, there shall be such a noise of singing, such a clinking of glasses, that he will soon be obliged to fly out again by the way he came in!”

Before he had ended, Madame Suzanne had thrown herself at his feet, and was kissing his hands. His speech, with its mingling of sadness and philosophy, had made more impression upon her than would have a sermon from the most eloquent of preachers. Even the lord of Vez did not remain unmoved; a tear gathered in the corner of his eye, and he lifted his finger to wipe it away, before holding out his hand to the Bailiff, saying as he did so:

“By the horn of Beelzebub! my dear friend, you have an upright mind and a kind heart, and it would be a sin indeed to bring trouble upon you; and if I have ever had a thought of doing you wrong, may God forgive me for it! I can safely swear, whatever happens, that I shall never have such another again.”

While this reconciliation was taking place between the three secondary actors in this tale, the situation of the fourth, that is of the principal character in it, was becoming more and more embarrassing.

Thibault’s heart was swelling with rage and hatred; himself unaware of the rapid growth of evil within him, he was fast growing, from a selfish and covetous man, into a wicked one. Suddenly, his eyes flashing, he cried aloud: “I do not know what holds me back from putting a terrible end to all this!”

On hearing this exclamation, which had all the character of a menace in it, the Baron and Suzanne understood it to mean that some great and unknown and unexpected danger was hanging over everybody’s heads. But the Baron was not easily intimidated, and he drew his sword for the second time and made a movement towards Thibault. Again the Bailiff interposed.

“My lord Baron! my lord Baron!” said Thibault in a low voice, “this is the second time that you have, in wish at least, passed your sword through my body; twice therefore you have been a murderer in thought! Take care! one can sin in other ways besides sinning in deed.”

“Thousand devils!” cried the Baron, beside himself with anger, “the rascal is actually reading me a moral lesson! My friend, you were wanting a little while ago to spit him like a woodcock, allow me to give him one light touch, such as the matador gives the bull, and I will answer for it, that he won’t get up again in a hurry.”

“I beseech you on my knees, as a favour to your humble servant, my lord,” replied the Bailiff, “to let him go in peace; and deign to remember, that, being my guest, there should no hurt nor harm be done to him in this poor house of mine.”

“So be it!” answered the Baron, “I shall meet him again. All kinds of bad reports are about concerning him, and poaching is not the only harm reported of him; he has been seen and recognised running the forest along with a pack of wolves and astonishingly tame wolves at that. It’s my opinion that the scoundrel does not always spend his midnights at home, but sits astride a broom-stick oftener than becomes a good Catholic; the owner of the mill at Croyolles has made complaint of his wizardries. However, we will not talk of it any more now; I shall have his hut searched, and if everything there is not as it should be, the wizard’s hole shall be destroyed, for I will not allow it to remain on his Highness’s territory. And now, take yourself off, and that quickly!”

The shoemaker’s exasperation had come to a pitch during this menacing tirade from the Baron; but, nevertheless, he profited by the passage that was cleared for him, and went out of the room. Thanks to his faculty of being able to see in the dark, he walked straight to the door, opened it, and passed over the threshold of the house, where he had left behind so many fond hopes, now lost forever, slamming the door after him with such violence that the whole house shook. He was obliged to call to mind the useless expenditure of wishes and hair of the preceding evening, to keep himself from asking that the whole house, and all within it, might be devoured by the flames. He walked on for ten minutes before he became conscious that it was pouring with rain, but the rain, frozen as it was, and even because it was so bitterly cold, seemed to do Thibault good. As the good Magloire had artlessly remarked, his bead was on fire.

On leaving the Bailiff’s house, Thibault had taken the first road he came to; he had no wish to go in one direction more than another, all he wanted was space, fresh air and movement. His desultory walking brought him first of all on to the Value lands; but even then he did not notice where he was until he saw the mill of Croyolles in the distance. He muttered a curse against its fair owner as he passed, rushed on like a madman between Vauciennes and Croyolles, and seeing a dark mass in front of him, plunged into its depths. This dark mass was the forest.

The forest-path to the rear of Ham, which leads from Croyolles to Preciamont, was now ahead of him, and into this he turned, guided solely by chance.

…to be continued.

The KPI Trap

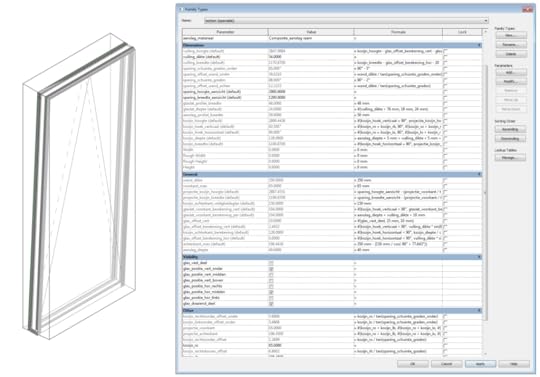

One of my students once proudly told me their Revit family—a window—had 42 parameters.

They had worked hard on it, tuning and nesting constraints, adding types, and connecting dimensions to carefully labeled values. Their excitement was tangible: a sense of mastery over a complex digital object, the satisfaction of building something with layers of control and variability.

“How did that impact the usability of the family?” I asked. ‘cuase I’m fun at parties.

They looked puzzled. It was the first time someone had questioned whether the complexity added by all those parameters actually served a purpose. Usability hadn’t even crossed their mind. The goal had been clear in their head: make it parametric. In their perception, it was the indicator of success.

Everybody loves a parametric window, right? (source here)

This is exactly how the problem starts.

The Metric of Perfection vs. The Perfect MetricI talked about quality a few weeks ago, with a bejewelled toilet brush, and how the measure of what we deliver has to be the actual impact change it’s able to produce for the client.

When we talk about KPIs—Key Performance Indicators—we act as if they’re neutral, just as we do with Quality. As if they’re convenient labels that help us monitor and improve. But KPIs are not neutral. KPIs shape behaviour. They define what “success” looks like, and more dangerously, they condition people—students, professionals, managers—to optimise for visibility rather than value. A thing needs to be parametric? Let’s parameter the shit out of it! A process needs to be full digital? Let’s jump on the throat of anyone who’s doodling.

In this case, the student’s implicit KPI was “number of parameters.” More parameters equalled better design. But anyone who’s ever had to use a bloated, fragile Revit family in a real project knows that this is the digital equivalent of putting lipstick on a spreadsheet. The model looks impressive, but resists actual use.

If you’re not particularly interested in KPIs but you are interested in Revit windows, this article talks you through the issue of usability from a technical point of view.

But a Revit window is a Revit window, and—as long and tiresome as that might be—if you encounter one that’s not usable, you can always make another one.

What worries me is how often this happens, not only in student projects but also across entire organisations. The wrong metrics, especially when left unchallenged, end up driving the wrong outcomes. They reward the appearance of complexity, the documentation of activity, the illusion of progress. And in doing so, they suffocate usability, clarity, and strategic intent.

Let’s take a look at KPIs then, at how does this happen and at how we can avoid it.

The Measurable Trap: When Metrics Replace MeaningThe problem, I believe, lies not just in which KPIs we choose, but in why we feel compelled to define KPIs in the first place. In digital processes—whether in architectural design, BIM workflows, or AI deployment—we often begin with qualitative, complex goals: improve collaboration, enhance design intent, support better decisions. But these ambitions are difficult to track. They don’t fit neatly into charts or dashboards.

So instead, we measure what we can. We substitute the original goal with something quantifiable. The result is a proxy—and that proxy, once formalised as a KPI, slowly begins to replace the original goal in people’s minds.

Take the student’s Revit family: their original intent might have been to create a flexible, reusable object for multiple contexts. That’s a valid design goal. But flexibility is hard to measure. It doesn’t come with an automatic score. So they reached for what could be counted—parameters—and took that count as proof of success.

The same logic applies to many digitalisation strategies in the AEC industry.

Consider a few examples (I changed them around a bit, but they all come from real life).

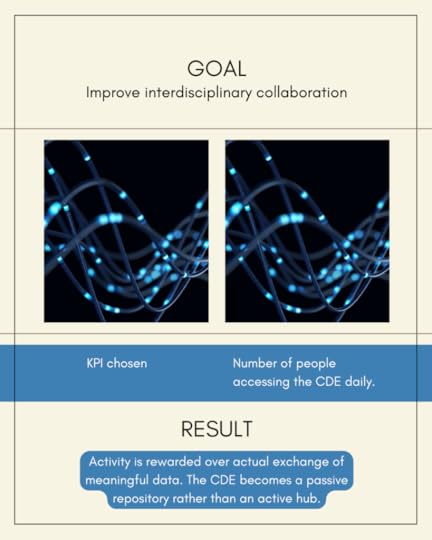

Goal: improve interdisciplinary collaboration.

KPI chosen: number of people accessing the CDE daily.

Result: activity is rewarded over actual exchange of meaningful data. The CDE becomes a passive repository rather than an active hub.

Goal: increase model quality.

KPI chosen: number of warnings or clashes detected.

Result: teams optimise to reduce clash counts rather than confront the real, systemic issues behind coordination problems.

Goal: empower decision-making through information.

KPI chosen: number of data-rich objects or parameters per object.

Result: the model becomes saturated with data nobody uses, complicating both authoring and maintenance.

These examples might seem like implementation failures, but they’re deeper than that. They’re failures of translation—a breakdown between intent and evaluation. And they reveal a fundamental issue with the very imperative to quantify.

What gets measured, gets managed—but only if the measurement is meaningful. If the measurement is a proxy, and the proxy becomes the focus, the system starts to drift. Over time, people no longer remember the original question. They just keep chasing the number.

Incidental Note: Not All KPIs Are NumbersWhile KPIs are often thought of as strictly quantitative, it’s worth remembering that qualitative KPIs exist—and matter. As you can see from a quick Google search (see here for instance), qualitative KPIs rely on observations, interviews, and subjective feedback to measure outcomes that resist numerical expression. They’re helpful for tracking things like team sentiment, client satisfaction, or creative value, where success is contextual rather than countable.

The catch? They require interpretation. Unlike dashboards that light up in green or red, qualitative indicators demand conversation. They’re not about how much but how well, and that shift can feel uncomfortable in data-driven environments. Still, if we care about strategic alignment and meaningful transformation, they’re often the only way to measure what matters.

KPIs? Where we’re going we don’t need KPIsYou might be thinking, “Let’s get rid of them!” Nope. This is not a call to abandon KPIs. Rather, it’s a call to treat them with caution and context. Especially in education and innovation, where so much of the value lies in what resists simple measurement—insight, clarity, provocation, perspective—we need to be more thoughtful about how we define “performance” at all.

Reframing the KPI: From Measurement to MeaningSo, how do we move forward, as educators and professionals, without falling into the measurable trap?

First, we stop thinking of KPIs as immutable targets and start thinking of them as strategic questions. Instead of asking how much or how fast, we begin with why, for whom, and to what end. That’s the difference between an actual KPI and a metric performance: the key, as in something that’s used to unlock meaningful insights and, in turn, to make decisions.

A good KPI is not just a number on a dashboard. It’s a signal—a way to check if a process is aligned with its purpose. In this light, a “Key Performance Indicator” becomes less about performance as output, and more about performance as navigation: are we still headed in the right direction?

In the context of BIM or digital workflows, this might mean replacing surface metrics like:

“Number of LOD 400 objects in the model” → “Number of modelling decisions made in coordination with downstream users”;“Speed of response from the AI assistant” → “Number of decisions meaningfully augmented by the AI process”These indicators don’t lend themselves to automated scoring. They require review, reflection, and dialogue. But that’s the point. Qualitative or hybrid KPIs force us to revisit strategy. They introduce friction—the productive kind—that makes room for interpretation.

In the classroom, I’ve begun encouraging students to define their own evaluation metrics at the start of a project. Not just to tell me what they’ll produce, but what kind of value they want to create, and how they’ll know if they’ve succeeded. The goal is to shift the centre of gravity from compliance to intentionality.

This doesn’t eliminate assessment. It makes it richer, more situated, and more honest. And in practice, it trains students to approach digital work not as an exercise in ticking boxes, but as a field of strategic decision-making, where the most important skill is knowing what not to automate, what not to model, and what to leave open.

Ultimately, the best KPIs are not measurements but mirrors. They help us see whether the process we’re following reflects the values we claim to hold. If it doesn’t, it’s not the indicator that failed us—it’s our failure to question it.

May 19, 2025

Exploring the Symbiotic Future in Sabrina Ratté’s Digital Art

In the heart of Milan, the MEET Digital Culture Center is currently hosting Realia, the first Italian solo exhibition of Canadian visual artist Sabrina Ratté. Running from March 13 to June 1, 2025, this immersive showcase delves into the convergence of technology and biology, inviting visitors to explore speculative ecosystems where the digital and natural worlds intertwine.

The technique used is generative: objects from everyday life are scanned or otherwise digitised, and then used to create forms that are either evolutions (or involutions) of those objects, or use the given geometry as a basis for growing something else. Do not expect anything too immersive or interactive, though: it’s a series of animated videos displayed in rooms with different surface treatments.

The Artist: Sabrina Ratté

The Artist: Sabrina RattéSabrina Ratté, born in Quebec in 1982, has been a prominent figure in digital art since the early 2010s. Her work often explores the interplay between architecture, virtual spaces, and the organic world, creating immersive environments that challenge perceptions of reality. Ratté’s art has been exhibited internationally, including at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of the Moving Image in New York.

The Exhibition: Realia

The Exhibition: RealiaRealia presents three of Ratté’s recent works, displayed in the galleries of the Digital Culture Center, plus a special display in the last, “immersive” room.

InflorescencesAs you step into the first gallery of Realia, you’re greeted by the voice of Sabrina Ratté herself—her words resonating from the video installation behind you in a calm yet deliberate introduction, which sets the philosophical tone of her work. Her aim is to reflect on a world where the artificial and the organic are no longer in opposition, but part of the same evolutionary narrative, and lost natural worlds are preserved and reborn into the digital one.

The centrepiece of the first room is Inflorescences, a video installation that transports us into a speculative ecosystem of the future where the boundaries between plant, machine, and the unknown dissolve. In a time after humans, Earth is emptied of our presence and still bears the marks of our existence through the technological debris we’ve left behind. Yet instead of a bleak, dystopian aftermath, Inflorescences offers a nuanced meditation on continuity and transformation. Discarded electronic devices—remnants of forgotten use and failed obsolescence—become the fertile ground for new life.

Ratté collected these abandoned objects from various locations and scanned them using 3D technology. In her hands, they are reborn as habitats and breeding grounds for strange new life forms: hybrid organisms that pulse and bloom with an eerie vitality.

The video sequences bring these beings to life with uncanny grace. Floral structures grow from circuit boards, metal casings, chips. The effect is haunting yet oddly hopeful, as if the Earth, left to its own devices, has found a way to reclaim and reimagine even the most toxic remnants of human invention.

What’s particularly striking is the aesthetic language of the work: vibrant and luminous, almost iridescent textures invite the viewer into intimate observation. It’s not just about ecological recovery, but about beauty—an alien, synthetic beauty that challenges our assumptions about what is natural or desirable. These creatures are not grotesque mutations; they are graceful, otherworldly testaments to adaptation and resilience.

In this first encounter with Realia, the tone is set: what we call waste can become substrate, and what we see as dead technology can be reanimated through imagination. It’s a powerful reminder that the digital—so often framed as cold, sterile, or disconnected—can also be a medium of regeneration, storytelling, and surprising beauty.

CyberdeliaThe second gallery offers a more intimate and participatory experience: Cyberdelia. Unlike the contemplative observation demanded by the first room, with lights and mirrors and secondary screens enhancing the videos, this installation invites you to engage through a sort of digital ritual.

The room offers a set of video works, accompanied by their soundscape co-composed by Sabrina Ratté and musician Roger Tellier-Craig, with the contributions of artificial intelligence. These audiovisual visions are paired with cards, each one representing a metaphysical concept. The invitation is to “consult the oracle”: visitors are encouraged to choose one of the cards, then place it on a glowing reader. In response, the chosen card triggers a corresponding video projection.

The title, Cyberdelia, evokes the spirit of a particular cultural moment: the cyberculture of the 1980s and ’90s, when digital technology was imagined as a portal to transcendence, and the virtual was about freedom, exploration, altered states of consciousness. Ratté resurrects that dream but reframes it for our current reality, one weighed down by ecological anxiety and the consequences of hyper-connectivity.

Plane of Incidence

Plane of IncidenceAs you move into the third and final gallery, the tone shifts again. The ambience goes back being quieter, mirrors appear again, and you find yourself in a room with two videos facing each other. Here, the work Plane of Incidence unfolds not so much as a narrative but as an ontological question. What is alive? What is dead? And what forms of consciousness or memory might linger in between? At the heart of this installation is a proposition both poetic and disquieting: what if objects, too, possess a kind of soul? What if the tools we discard, the devices we break, the trinkets we leave behind on sidewalks and in alleyways, are more than inert matter? Plane of Incidence opens up that imaginative space, drawing from traditions as old as animism and as futuristic as speculative evolution to propose a world where the boundaries between the inert and the animate are radically porous.

To create this work, Ratté collected abandoned objects—found by chance on the streets of Montreal and Marseille. These were not carefully curated artefacts but rather the cast-offs of urban life: broken electronics, rusted mechanical parts, forgotten toys, mundane plastic debris. Each was digitally scanned and lifted into a virtual plane, removed from the noise of the real world and recontextualised within luminous, otherworldly environments. Once in this new space, the objects begin to change. They don’t just sit as remnants of a bygone era—they morph, mutate, and merge with imagined biological entities. Shapes stretch and contort with uncanny grace; surfaces bloom and pulse with an internal rhythm; limbs, tendrils, wings—something not-quite-organic, not-quite-machine—emerges. These new hybrid beings occupy a realm where nature and artefact are no longer distinct, but fluidly entangled.

The title itself, Plane of Incidence, evokes geometry and optics—a point where light strikes a surface, where angles and refractions shape what we perceive. But here, it also speaks to philosophical intersections: between being and becoming, object and subject, presence and absence. Ratté’s work lives precisely in that liminal zone.

Floralia

FloraliaThe heart of the show is a large, dark room where every surface is occupied by Floralia, a four-act digital installation that pulses with memory, absence, and renewal. It is the most expansive and contemplative moment of Realia.

The setting is anchored firmly in loss: Floralia imagines a world where botanical life as we know it has vanished—plant species rendered extinct by climate catastrophe, human negligence, or the inevitable entropy of time. In this imagined tomorrow, what remains is not the flora itself, but a virtual archive: a digital sanctuary where the spectral presence of these plants is preserved, catalogued, and quietly mourned. The space is configured as a kind of memory vault. Through four cinematic movements, visitors traverse an unfolding landscape of archived plant samples, but this is no sterile repository of taxonomies; the digital environment pulses with strange vitality, the visuals seem to glitch, dissolve, and reform—not from technological error, but as though the memories of the plants themselves were interfering with the simulation. Instead of static data sets, they feel like haunted presences, pressing against the boundaries of their own containment.

Is it worth the visit?I would say yes, but it depends on what you’re looking for. Realia is more an art exhibition that explores possible futures where technology and nature are not adversaries but collaborators, and yet it doesn’t do so in a way that puts technological experimentation at the centre. While the artist’s work challenges us to rethink our place in the world and inspires hope for a harmonious coexistence, her methods are left in the shadows and this might be disappointing for technological geeks such as myself.

And yet, in an age where digital art is often associated with coldness or detachment, Ratté’s work stands out for its warmth and humanity. The beauty of the digital in Realia lies in its ability to mirror the complexities of life, growth, decay, and rebirth, a reminder that technology, when intertwined with artistic vision, can offer profound insights into our existence.

And the MEET Digital Culture Center is a must-see experience if you’ve never been there, and a place to monitor constantly for the cutting-edge reflections they host. If you visit, let me know what you think. You have time until June, 1st.

May 16, 2025

Rediscovering the Magic of Practical Effects

The Infinite Art of Practical Effects, at the museum venue called Fabbrica del Vapore, is an invitation to embark on a nostalgic journey through how movies used to be made, and it’s closing this week-end, on May 18.

This unique showcase pays homage to a movie that terrified me as a child, The NeverEnding Story—celebrating its 40th anniversary— and shows how the artists involved came from other masterpieces of the same era: Dark Crystal, Flash Gordon, Labyrinth, Battlestar Galactica, and—of course—Star Wars. Through a curated collection of original artworks, behind-the-scenes photographs, and a few meticulously crafted replicas, visitors gain insight into the practical effects that brought these stories to life.

The NeverEnding Story in particular heavily relied on practical effects, both for its fantastical creatures and the magical world of Fantastica. This included animatronic models for large creatures, physical sets like the Ivory Tower, and innovative use of lighting and blue screens to create a magical atmosphere.

A collaborative effort between GoPractical and FXLAB, it features original sketches and paintings by renowned poster artist Renato Casaro, an archive of over 200 restored behind-the-scenes photographs, and interactive replicas created in collaboration with Magnoli Props.

Visitors can also explore detailed set reconstructions developed with Idea Factory Store and WhiteLabel, as well as exclusive video content produced by GoPractical.

In an era dominated by CGI and virtual effects, this exhibition underscores the enduring value of practical effects—the physical craftsmanship that once defined cinematic storytelling. By showcasing the tangible techniques of the past, it encourages a renewed appreciation for the artistry that continues to inspire filmmakers and audiences alike.

May 14, 2025

Werewolves Wednesday: The Wolf-Leader (12)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter XII: Wolves in the Sheep FoldThe forest was not far from the Bailiff’s house, and in two bounds Thibault found himself on the further side of Les Fosses, and in the wooded path leading to the brickyard. He had no sooner entered the forest than his usual escort surrounded him, fawning and blinking with their eyes and wagging their tails to show their pleasure. Thibault, who had been so alarmed the first time he found himself in company with this strange body guard, took no more notice of them now than if they had been a pack of poodles. He gave them a word or two of caress, softly scratched the head of the one that was nearest him, and continued on his way, thinking over his double triumph.

He had beaten his host at the bottle, he had vanquished his adversary at fisticuffs, and in this joyous frame of mind, he walked along, saying aloud to himself:

“You must acknowledge, friend Thibault, that you are a lucky rascal! Madame Suzanne is in every possible respect just what you want! A Bailiff’s wife! my word! that’s a conquest worth making! and if he dies first, what a wife to get! But in either case, when she is walking beside me, and taking my arm, whether as wife or mistress, the devil take it, if I am mistaken for anything but a gentleman! And to think that unless I am fool enough to play my cards badly, all this will be mine! For she did not deceive me by the way she went off: those who have nothing to fear have no need to take flight. She was afraid to show her feelings too plainly at first meeting; but how kind she was after she got home! Well, well, it is all working itself out, as I can see; I have only got to push matters a bit; and some fine morning she will find herself rid of her fat little old man, and then the thing is done. Not that I do, or can, wish for the death of poor Monsieur Magloire. If I take his place after he is no more, well and good; but to kill a man who has given you such good wine to drink! to kill him with his good wine still hot in your mouth! why, even my friend the wolf would blush for me if I were guilty of such a deed.”

Then with one of his most roguish smiles, he went on:

“And besides, would it not be as well to have already acquired some rights over Madame Suzanne, by the time Monsieur Magloire passes, in the course of nature, into the other world, which, considering the way in which the old scamp eats and drinks, cannot be a matter of long delay?”

And then, no doubt because the good qualities of the Bailiff’s wife which had been so highly extolled to him came back to his mind:

“No, no,” he continued, “no illness, no death! but just those ordinary disagreeables which happen to everybody; only, as it is to be to my advantage, I should like rather more than the usual share to fall to him; one cannot at his age set up for a smart young buck; no, every one according to their dues … and when these things come to pass, I will give you more than a thank you, Cousin Wolf.”

My readers will doubtless not be of the same way of thinking as Thibault, who saw nothing offensive in this pleasantry of his, but on the contrary, rubbed his hands together smiling at his own thoughts, and indeed so pleased with them that he had reached the town, and found himself at the end of the Rue de Largny before he was aware that he had left the Bailiff’s house more than a few hundred paces behind him.

He now made a sign to his wolves, for it was not quite prudent to traverse the whole town of Villers-Cotterets with a dozen wolves walking alongside as a guard of honour; not only might they meet dogs by the way, but the dogs might wake up the inhabitants.

Six of his wolves, therefore, went off to the right, and six to the left, and although the paths they took were not exactly of the same length, and although some of them went more quickly than the others, the whole dozen nevertheless managed to meet, without one missing, at the end of the Rue de Lormet. As soon as Thibault had reached the door of his hut, they took leave of him and disappeared; but, before they dispersed, Thibault requested them to be at the same spot on the morrow, as soon as night fell.

Although it was two o’clock before Thibault got home, he was up with the dawn; it is true, however, that the day does not rise very early in the month of January.

He was hatching a plot. He had not forgotten the promise he had made to the Bailiff to send him some game from his warren; his warren being, in fact, the whole of the forest-land which belonged to his most serene Highness the Duke of Orleans. This was why he had got up in such good time. It had snowed for two hours before day-break; and he now went and explored the forest in all directions, with the skill and cunning of a bloodhound.

He tracked the deer to its lair, the wild boar to its soil, the hare to its form; and followed their traces to discover where they went at night.

And then, when darkness again fell on the Forest, he gave a howl, a regular wolfs howl, in answer to which came crowding to him the wolves that he had invited the night before, followed by old and young recruits, even to the very cubs of a year old.

Thibault then explained that he expected a more than usually fine night’s hunting from his friends, and as an encouragement to them, announced his intention of going with them himself and giving his help in the chase.

It was in very truth a hunt beyond the power of words to describe. The whole night through did the sombre glades of the forest resound with hideous cries.

Here, a roebuck pursued by a wolf, fell, caught by the throat by another wolf hidden in ambush; there, Thibault, knife in hand like a butcher, was running to the assistance of three or four of his

ferocious companions, that had already fastened on a fine young boar of four years old, which he now finished off.

An old she-wolf came along bringing with her half-a-dozen hares which she had surprised in their love frolics, and she had great difficulty in preventing her cubs from swallowing a whole covey of young partridges which the young marauders had come across with their heads under their wings, without first waiting for the wolf-master to levy his dues,

Madame Suzanne Magloire little thought what was taking place at this moment in the forest of Villers-Cotterets, and on her account.

In a couple of hours’ time the wolves had heaped up a perfect cart-load of game in front of Thibault’s hut.

Thibault selected what he wanted for his own purposes, and left over sufficient to provide them a sumptuous repast. Borrowing a mule from a charcoal-burner, on the pretext that he wanted to convey his shoes to town, he loaded it up with the game and started for Villers-Cotterets. There he sold a part of this booty to the gamedealer, reserving the best pieces and those which had been least mutilated by the wolves’ claws, to present to Madame Magloire.

His first intention had been to go in person with his gift to the Bailiff; but Thibault was beginning to have a smattering of the ways of the world, and thought it would, therefore, be more be coming to allow his offering of game to precede him. To this end he employed a peasant on payment of a few coppers, to carry the game to the Bailiff of Erneville, merely accompanying it with a slip of paper, on which he wrote: “From Monsieur Thibault.” He, himself, was to follow closely on the message; and, indeed, so closely did he do so, that he arrived just as Maitre Magloire was having the game he had received spread out on a table.

The Bailiff, in the warmth of his gratitude, extended his arms towards his friend of the previous night, and tried to embrace him, uttering loud cries of joy. I say tried, for two things prevented him from carrying out his wish; one, the shortness of his arms, the other, the rotundity of his person.

But thinking that where his capacities were insufficient, Madame Magloire might be of assistance, he ran to the door, calling at the top of his voice: “Suzanne, Suzanne!”

There was so unusual a tone in the Bailiff’s voice that his wife felt sure some thing extraordinary had happened, but whether for good or ill she was unable to make sure: and downstairs she came, therefore, in great haste, to see for herself what was taking place.

She found her husband, wild with delight, trotting round to look on all sides at the game spread on the table, and it must be confessed, that no sight could have more greatly rejoiced a gourmand’s eye. As soon as he caught sight of Suzanne, “Look, look, Madame!” he cried, clapping his hands together. “See what our friend Thibault has brought us, and thank him for it. Praise be to God! there is one person who knows how to keep his promises! He tells us he will send a hamper of game, and he sends us a cart-load. Shake hands with him, embrace him at once,

and just look here at this.”

Madame Magloire graciously followed out her husband’s orders; she gave Thibault her hand, allowed him to kiss her, and cast her beautiful eyes over the supply of food which elicited such exclamations of admiration from the Bailiff. And as a supply, which was to make such an acceptable addition to the ordinary daily fare, it was certainly worthy of all admiration.

First, as prime pieces, came a boar’s head and ham, firm and savoury morsels; then a fine three year old kid, which should have been as tender as the dew that only the evening before beaded the grass at which it was nibbling; next came hares, fine fleshy hares from the heath of Gondreville, full fed on wild thyme; and then such scented pheasants, and such delicious red-legged partridges, that once on the spit, the magnificence of their plumage was forgotten in the perfume of their flesh. And all these good things the fat little man enjoyed in advance in his imagination; he already saw the boar broiled on the coals, the kid dressed with sauce piquante, the hares made into a pasty, the pheasants stuffed with truffles, the partridges dressed with cabbage, and he put so much fervour and feeling into his orders and directions, that merely to hear him was enough to set a gourmand’s mouth watering.

It was this enthusiasm on the part of the Bailiff which no doubt made Madame Suzanne appear somewhat cold and unappreciative in comparison. Nevertheless she took the initiative, and with much graciousness assured Thibault that she would on no account allow him to return to his farms until all the provisions, with which, thanks to him, the larder would now overflow, had been consumed. You may guess how delighted Thibault was at having his cherished wishes thus met by Madame herself. He promised himself no end of grand things from this stay at Erneville, and his spirits rose to the point of himself proposing to Maitre Magloire that they should indulge in a preparatory whack of liquor to prepare their digestions for the savoury dishes that Mademoiselle Perrine was preparing for them.

Maitre Magloire was quite gratified to see that Thibault had forgotten nothing, not even the cook’s name. He sent for some vermouth, a liqueur as yet but little known in France, having been imported from Holland by the Duke of Orleans and of which a present had been made by his Highness’s head cook to his predecessor.

Thibault made a face over it; he did not think this foreign drink was equal to a nice little glass of native Chablis; but when assured by the Bailiff that, thanks to the beverage, he would in an hour’s time have a ferocious appetite, he made no further remark, and affably assisted his host to finish the bottle. Madame Suzanne, meanwhile, had returned to her own room to smarten herself up a bit, as women say, which generally means an entire change of raiment.

It was not long before the dinner-hour sounded, and Madame Suzanne came down stairs again. She was perfectly dazzling in a splendid dress of grey damask trimmed with pearl, and the transports of amorous admiration into which Thibault was thrown by the sight of her prevented the shoe-maker from thinking of the awkwardness of the position in which he now unavoidably found himself, dining as he was for the first time with such handsome and distinguished company. To his credit, be it said, he did not make bad use of his opportunities. Not only did he

cast frequent and unmistakable sheep’s eyes at his fair hostess, but he gradually brought his knee nearer to hers, and finally went so far as to give it a gentle pressure. Suddenly, and while Thibault was engaged in this performance, Madame Suzanne, who was looking sweetly towards him, opened her eyes and stared fixedly a moment. Then she opened her mouth, and went off into such a violent fit of laughter, that she almost choked, and nearly went into hysterics Maitre Magloire, taking no notice of the effect, turned straight to the cause, and he now looked at Thibault, and was much more concerned and alarmed with what he thought to see, than with the nervous state of excitement into which his wife had Deen thrown by her hilarity.

“Ah! my dear fellow!” he cried, stretching two little agitated arms towards Thibault, “you are in flames. you are in flames!”

Thibault sprang up hastily.

“Where? How?” he asked.

“Your hair is on fire,” answered the Bailiff, in all sincerity; and so genuine was his terror, that he seized the water Dottle that was in front of his wife in order to put out the conflagration blazing among Thibault’s locks.

The shoe-maker involuntarily put up his hand to his head, but feeling no heat, he at once guessed what was the matter, and fell back into his chair, turning horribly pale. He had been so preoccupied during the last two days, that he had quite for gotten to take the same precaution he had done before visiting the owner of the mill, and had omitted to give his hair that particular twist whereby he was able to hide the hairs of which the black wolf had acquired the proprietorship under his others. Added to this, he had during this short period given vent to so many little wishes, one here, and one there, all more or less to the detriment of his neighbour, that the flame-coloured hairs had multiplied to an alarming extent, and at this moment, any one of them

could vie in brilliancy with the light from the two wax candles which lit the room.

“Well, you did give me a dreadful fright, Monsieur Magloire,” said Thibault, trying to conceal his agitation.

“But, but…” responded the Bailiff, still pointing with a certain remains of fear at Thibault’s flaming lock of hair.

“That is nothing,” continued Thibault, “do not be uneasy about the unusual colour of some of my hair; it came from a fright my mother had with a pan of hot coals, that nearly set her hair on fire before I was born.”

“But what is more strange still,” said Madame Suzanne, who had swallowed a whole glassful of water in the effort to control her laughter, “that I have remarked this dazzling peculiarity for the

first time to-day.”

“Ah! really!” said Thibault, scarcely knowing what to say in answer.

“The other day,” continued Madame Suzanne, “it seemed to me that your hair was as black as my velvet mantle, and yet, believe me, I did not fail to study you most attentively, Monsieur Thibault.”

This last sentence, reviving Thibault’s hopes, restored him once more to good humour.

“Ah! Madame,” he replied, “you know the proverb: ‘Red hair, warm heart,’ and the other: ‘Some folks are like ill-made sabots, smooth outside, but rough to wear?'”

Madame Magloire made a face at this low proverb about wooden shoes, but, as was often the case with the Bailiff, he did not agree with his wife on this point.

“My friend Thibault utters words of gold,” he said, “and I need not go far to be able to point the truth of his proverbs … See for example, this soup we have here, which has nothing much in its appearance to commend it, but never have I found onion and bread fried in goose-fat more to my taste.”

And after this there was no further talk of Thibault’s fiery head. Nevertheless, it seemed as if Madame Suzanne’s eyes were irresistibly attracted to this unfortunate lock, and every time that Thibault’s eyes met the mocking look in hers, he thought he detected on her face a reminiscence of the laugh which had not long since made him feel so uncomfortable. He was very much annoyed at this, and, in spite of himself, he kept putting up his hand to try and hide the unfortunate lock under the rest of his hair. But the hairs were not only unusual in colour, but also of a phenomenal stiffness it was no longer human hair, but horse-hair. In vain Thibault endeavoured to hide the devil’s hairs beneath his own, nothing, not even the hair-dresser’s tongs could have

induced them to lie otherwise than in the way which seemed natural to them. But although so occupied with thinking of his hair, Thibault’s legs still continued their tender manoeuvres; and although Madame Magloire made no response to their solicitations, she apparently had no wish to escape from them, and Thibault was presumptuously led to believe that he had achieved a conquest.

They sat on pretty late into the night, and Madame Suzanne, who appeared to find the evening drag, rose several times from the table and went backwards and forwards to other parts of the house, which afforded the Bailiff opportunities of frequent visits to the cellar.

He hid so many bottles in the lining of his waistcoat, and once on the table, he emptied them so rapidly, that little by little his head sank lower and lower on to his chest, and it was evidently high time to put an end to the bout, if he was to be saved from falling under the table.

Thibault decided to profit by this condition of things, and to declare his love to the Bailiff’s wife without delay, judging it a good opportunity to speak while the husband was heavy with drink; he

therefore expressed a wish to retire for the night. Whereupon they rose from table, and Perrine was called and bidden to show the guest to his room. As he followed her along the corridor, he made enquiries of her concerning the different rooms.

Number one was Maitre Magloire’s, number two that of his wife, and number three was his. The Bailiff’s room, and his wife’s, communicated with one another by an inner door; Thibault’s room had access to the corridor only.

He also noticed that Madame Suzanne was in her husband’s room; no doubt some pious sense of conjugal duty had taken her there. The good man was in a condition approaching to that of Noah when his sons took occasion to insult him, and Madame Suzanne’s assistance would seem to have been needed to get him into his room.

Thibault left his own room on tiptoe, carefully shut his door behind him, listened for a moment at the door of Madame Suzanne’s room, heard no sound within, felt for the key, found it in the lock, paused a second, and then turned it.

The door opened; the room was in total darkness. But having for so long consorted with wolves, Thibault had acquired some of their characteristics, and, among others, that of being able to see in the dark.

He cast a rapid glance round the room; to the right was the fireplace; facing it a couch with a large mirror above it; behind him, on the side of the fire-place, a large bed, hung with figured silk; in front of him, near the couch, a dressing table covered with a profusion of lace, and, last of all, two large draped windows. He hid himself behind the curtains of one of these, instinctively choosing the window that was farthest removed from the husband’s room. After waiting a quarter of an hour, during which time Thibault’s heart beat so violently that the sound of it, fatal omen! reminded him of the click-clack of the mill-wheel at Croyolles, Madame Suzanne entered the room.

Thibault’s original plan had been to leave his hiding place as soon as Madame Suzanne came in and the door was safely shut behind her, and there and then to make avowal of his love. But on consideration, fearing that in her surprise, and before she recognised who it was, she might not be able to suppress a cry which would betray them, he decided that it would be better to wait until Monsieur Magloire was asleep beyond all power of being awakened.

Perhaps, also, this procrastination may have been partly due to that feeling which all men have, however resolute of purpose they may be, of wishing to put off the critical moment, when on this moment depend such chances as hung on the one which was to decide for or against the happiness of the shoemaker. For Thibault, by dint of telling himself that he was madly in love with Madame Magloire, had ended by believing that he really was so, and, in spite of being under the protection of the black wolf, he experienced all the timidity of the genuine lover. So he kept himself concealed behind the curtains.

The Bailiff’s wife, however, had taken up her position before the mirror of her Pompadour table, and was decking herself out as if she were going to a festival or preparing to make one of a procession.

She tried on ten veils before making choice of one.

She arranged the folds of her dress.

She fastened a triple row of pearls round her neck.

Then she loaded her arms with all the bracelets she possessed.

Finally she dressed her hair with the minutest care.

Thibault was lost in conjectures as to the meaning of all this coquetry, when all of a sudden a dry, grating noise, as if some hard body coming in contact with a pane of glass, made him start. Madame Suzanne started too, and immediately put out the lights. The shoemaker then heard her step softly to the window, and cautiously open it; whereupon there followed some whisperings, of which Thibault could not catch the words, but, by drawing the curtain a little aside, he was able to distinguish in the darkness the figure of a man of gigantic stature, who appeared to be climbing through the window.

Thibault instantly recalled his adventure with the unknown combatant, whose mantle he had clung to, and whom he had so triumphantly disposed of by hitting him on the forehead with a stone. As far as he could make out, this would be the same window from which the giant had descended when he made use of Thibault’s two shoulders as a ladder. The surmise of identity was, undoubtedly, founded on a logical conclusion. As a man was now climbing in at the window, a man could very well have been climbing down from it; and if a man did climb down from it–unless, of

course, Madam Magloire’s acquaintances were many in number, and she had a great variety of tastes–if a man did climb down from it, in all probability, it was the same man who, at this moment was climbing in.

But whoever this nocturnal visitor might be, Madame Suzanne held out her hand to the intruder, who took a heavy jump into the room, which made the floor tremble and set all the furniture shaking. The apparition was certainly not a spirit, but a corporeal body, and moreover one that came under the category of heavy bodies.

“Oh! take care, my lord,” Madame Suzanne’s voice was heard to say, “heavily as my husband sleeps, if you make such a noise as that, you will wake him up.”

“By the devil and his horns! my fair friend,” replied the stranger. “I cannot alight like a bird!” and Thibault recognised the voice as that of the man with whom he had had the altercation a night or two before. “Although while I was waiting under your window for the happy moment, my heart was so sick with longing that I felt as if wings must grow ere long, to bear me up into this dear wished-for little room.”

“And I too, my lord,” replied Madame Magloire with a simper, “I too was troubled to leave you outside to freeze in the cold wind, but the guest who was with us this evening only left us half an hour ago.”

“And what have you been doing, my dear one, during this last half hour?”

“I was obliged to help Monsieur Magloire, my lord, and to make sure that he would not come and interrupt us.”

“You were right as you always are, my heart’s love.”

“My lord is too kind,” replied Suzanne or, more correctly, tried to reply, for her last words were interrupted as if by some foreign body being placed upon her lips, which prevented her from finishing the sentence; and at the same moment, Thibault heard a sound which was remarkably like that of a kiss. The wretched man was beginning to understand the extent of the disappointment of which he was again the victim. His reflections were interrupted by the voice of the newcomer, who coughed two or three times.

“Suppose we shut the window, my love,” said the voice, after this preliminary coughing.

“Oh! my lord, forgive me,” said Madame Magloire, “it ought to have been closed before.” And so saying she went to the window, which she first shut close, and then closed even more hermetically by drawing the curtains across it. The stranger meanwhile, who made himself thoroughly at home, had drawn an easy chair up to the fire, and sat with his legs stretched out, warming his feet in the most luxurious fashion. Reflecting no doubt, that for a man half frozen, the most immediate necessity is to thaw himself, Madame Suzanne seemed to find no cause of offence in this behaviour on the part of her aristocratic lover, but came up to his chair and leant her pretty arms over the back in the most fascinating posture Thibault had a good view of the group from

behind, well thrown up by the light of the fire, and he was overcome with inward rage. The stranger appeared for a while to have no thought beyond that of warming himself; but at last the fire having performed its appointed task, he asked:

“And this stranger, this guest of yours who was he?”

“Ah! my lord!” answered Madame Magloire, “you already know him I think only too well.”

“What!” said the favoured lover, “do you mean to say it was that drunken lout of the other night, again?”

“The very same, my lord.”

“Well, all I can say is, if ever I get him into my grip again!…”

“My lord,” responded Suzanne, in a voice as soft as music, “you must not harbour evil designs against your enemies; on the contrary, you must forgive them as we are taught to do by our Holy Religion.”

“There is also another religion which teaches that, my dearest love, one of which you are the all-supreme goddess, and I but a humble neophyte … And I am wrong in wishing evil to the scoundrel, for it was owing to the treacherous and cowardly way in which he attacked and did for me, that I had the opportunity I had so long wished for, of being introduced into this house. The lucky blow on my forehead with his stone, made me faint; and because you saw I had fainted, you called your husband; it was on account of your husband finding me without consciousness beneath your window, and believing I had been set upon by thieves, that he had me carried indoors; and lastly, because you were so moved by pity at the thought of what I had suffered for you, that you were willing to let me in here. And so, this good-for-nothing fellow, this contemptible scamp, is after all the source of all good, for all the good of life for me is in your love; nevertheless if ever he comes within reach of my whip, he will not have a very pleasant time of it.”

“It seems then,” muttered Thibault, swearing to himself, “that my wish has again turned to the advantage of someone else! Ah! my friend, black wolf, I have still something to learn, but, confound it all! I will in future think so well over my wishes before expressing them that the pupil will become master … but to whom does that voice, that I seem to know, belong?” Thibault continued, trying to recall it, “for the voice is familiar to me, of that I am certain!”

“You would be even more incensed against him, poor wretch, if I were to tell you something.”

“And what is that, my love?”

“Well, that good-for-nothing fellow, as you call him, is making love to me.”

“Phew!”

“That is so, my lord,” said Madame Suzanne, laughing.

“What! that boor, that low rascal! Where is he? Where does he hide himself? By Beelzebub! I’ll throw him to my dogs to eat!”

And then, all at once, Thibault recognised his man. “Ah! my lord Baron,” he muttered, “it’s you, is it?”

“Pray do not trouble yourself about it, my lord,” said Madame Suzanne, laying her two hands on her lover’s shoulders, and obliging him to sit down again, “your lordship is the only person whom I love, and even were it not so, a man with a lock of red hair right in the middle of his forehead is not the one to whom I should give away my heart.” And as the recollection of this lock of hair, which had made her laugh so at dinner, came back to her, she again gave way to her amusement.

A violent feeling of anger towards the Bailiff’s wife took possession of Thibault.

“Ah! traitress!” he exclaimed to himself, “what would I not give for your husband, your good, upright husband, to walk in at this moment and surprise you.”

Scarcely was the wish uttered, when the door of communication between Suzanne’s room and that of Monsieur Magloire was thrown wide open, and in walked her husband with an enormous night-cap on his head, which made him look nearly five feet high, and holding a lighted candle in his hand.

“Ah! ah!” muttered Thibault. “Well done! It’s my turn to laugh now, Madame Magloire.”

…to be continued.

Still Lives: A Casoratian Walk Through Milan

After seeing the splendid exhibition dedicated to Casorati here in Milan, I was reminded by an old-time friend that once upon a time I used to organise themed visits around Milan and bring them about. It was nice, so here I am. Have you been to see the recent exhibition? Have you ever been a long-time lover of the painter? Do you like architecture, or do you simply want a stroll around Milan that doesn’t take you to see the same old things and doesn’t worship ugly, fascist architecture? Here I am. I’ve come to save you with my Casoratian Walk Through Milan (or, as it has been dubbed by that same friend, A Metaphysical Urban Diary in Seven Movements).

“To paint is not to describe, but to frame a silence.”

– Felice Casorati

Felice Casorati’s world is one of perfect pauses. His paintings, whether depicting suspended female figures, interior spaces dense with geometry, or scenes drained of narrative tension, resist action. Instead, they offer stillness, structure, and a profound, disquieting sense of presence. Casorati did not paint to explain; he composed, balanced, and withheld. Each canvas is a psychological container—a space where time hesitates and emotion is sublimated into form.