Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 3

September 3, 2025

Kafka in the C-Suite: Bureaucracy, Resistance, and the Digital Turn

There is a scene, or rather a sensation, that repeats itself across time and professions: the quiet frustration of waiting for an answer that never comes, submitting an output whose purpose is unclear, knocking — figuratively or literally — on a door that leads only to another corridor. This is Kafka. And if Franz Kafka ever needed a new setting for his dramas of helpless persistence and obscure authority, the modern corporate suite in the construction and infrastructure sectors would welcome him like a lost brother.

This man would have made for a wonderful engineer. On the other hand, if you’re looking for some insights on his relationship with architecture, take a look here.

This man would have made for a wonderful engineer. On the other hand, if you’re looking for some insights on his relationship with architecture, take a look here.In The Castle, Kafka’s protagonist, known only as K., attempts to gain access to a mysterious bureaucratic structure that governs a village, receiving contradictory instructions, facing unseen authorities, and finding himself entangled in endless delays.

Kafka was not writing about bureaucracy in the narrow sense. He was unveiling a philosophy of organization: systems that devour purpose in the name of process, that manufacture opacity under the guise of structure. Max Weber saw bureaucracy as the “iron cage” of modernity. Kafka handed us the key and showed us it fit no lock.

Today, one could argue that K. wears a tailored suit, carries a tablet, and sits in coordination meetings on Teams. The Castle is still there: it just has a dashboard.

1. Digital Liberation or Algorithmic Entrapment?

1. Digital Liberation or Algorithmic Entrapment?In the early years of digital transformation, especially in the AEC industry, a narrative of emancipation reigned. Collaborative platforms, parametric design, and integrated data environments promised to dismantle silos, flatten hierarchies, empower a new generation and restore control to those at the creative core. We told ourselves that the machine would set us free.

But freedom is a slippery concept when mediated by workflows.

Enter this week’s thought experiment: what if digitalization, instead of breaking the iron cage, is just reinforcing it with smarter, faster, more flexible bars?

This is not a neo-Luddite lament, of course, even if the Luddites were right on some accounts but that would be a conversation for another time. This is a provocation born of love and frustration, the kind you feel while watching someone embrace a toxic routine convinced it’s for their own good. In theory, digital systems should reduce friction. In practice, they often reproduce — and refine — old frictions in sleeker forms: approval workflows nested in SharePoint, permissions tangled in CDEs technological solutions, metadata fields more rigid than paper stamps ever were.

Today we ask ourselves: are we building platforms or palaces of paper with digital bricks?

And we do so through a sort of dialogue between Kafka and the C-Suite — all those people starting with a C as in CEO, CFO, and imagining the BIM manager as a CBO — not to romanticise dysfunction, of course, but to illuminate its logic in an age of platforms. Through Kafka’s literary lens, we examine the tension between rigid structures and the agile, digital processes meant to replace them. We’ll explore:

how bureaucratic logic persists through digital form;whether resistance is still possible, or simply recoded;if innovation always tends toward control once scaled.You will find no manifesto here, but you may find resolve. Like Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, which urged us to navigate post-human complexity without retreating into nostalgia, today’s read calls for creative defiance within the system, for allies who code workarounds and design humane interfaces. It calls for us to see the system not as enemy, but as terrain.

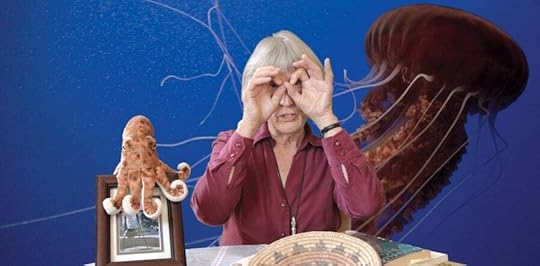

Donna Haraway: if you don’t know her, read her work2. Kafkaesque Bureaucracy in the AEC Industry

Donna Haraway: if you don’t know her, read her work2. Kafkaesque Bureaucracy in the AEC IndustryAnyone who has worked on a large infrastructure project knows the dance: a model-based drawing must be approved, but first by the BIM Coordinator, then by the Project Manager, then perhaps the Quality Manager, who sends it to the Contractor, who sends it to the Client, who forwards it to a third-party reviewer, who — after weeks — returns it with a note: please adjust line thickness in the legend.

No one quite knows who made the final decision. No one assumes responsibility for the delay. And yet the delay is real, measurable, and costly.

Here lies the first sign of the Kafkaesque: decisions emerge, but from nowhere in particular. Like in The Trial, where Josef K. is arrested without being told why or by whom, professionals in the AEC sector often find themselves held accountable to standards or timelines that are enforced by ghostly chains of command. You submitted the IFC model? Excellent. But has it been approved by “the client’s BIM auditor”? Has the technical note from the MEP team been “seen by legal”? No one knows who “legal” is.

This is not mere inefficiency: it is a structural opacity. An architecture of invisibility that survives the very systems meant to streamline it.

Digital tools have, paradoxically, amplified the phenomenon. With every added layer of visibility (a new field, a tracked change, a revision number), we have multiplied the points of potential obstruction. We have encoded the bureaucracy, made it faster, yes, but no less mysterious. The submission has a status. It is “Under Review”. But by whom? For how long? According to which logic?

This is the world Kafka described: not a failed system, but a system so successful in its self-perpetuation that failure becomes irrelevant.

2.1. Bureaucracy as Ritual and LabyrinthWe spoke about labyrinths before, as places to explore and in which you find yourself, but the concept has another, darker and less optimistic structure, because it isn’t obvious that you’ll ever emerge from such a labyrinth. Like ever.

In The Castle, K. is summoned to work in a village governed by a distant and inscrutable administration. He tries to clarify his role, to access the Castle that summoned him, but every encounter brings contradiction, and every path leads back to confusion. Even those who live in the system — secretaries, messengers, minor officials — do not understand how it works. They comply, they guess, they improvise. Sounds familiar?

This is not bureaucracy as rule-following, which can be virtuous, but bureaucracy as ritual: a set of motions performed because they feel official, even when they no longer serve a function. We stamp because we’ve always stamped. We request a PDF and a print because someone, somewhere, once asked for both. We log in to multiple platforms, because each department claims ownership of a different one.

The AEC industry is steeped in regulatory demands, contract layers, and liability fears, and loads of them are there for everyone’s safety, but this means it’s especially prone to this ritualism. Kafka helps us see that it’s not only inefficiency at play: it’s the need for reassurance in complexity. When confronted with risk, we multiply approvals not to clarify responsibility, but to distribute it until it dissolves. And like Kafka’s labyrinths, AEC bureaucracy in a complex project often seems not to have a centre. The goal is always just beyond the next corridor. Submittals “in review” for weeks. Change requests that “must go to committee.” Meetings to discuss whether to have another meeting. The moment one hears, “I’ll escalate it and come back to you”, Kafka smiles.

2.2. Case Parallels: Legacy Workflows in Construction and DesignConsider the legacy of drawing approvals on megaprojects: engineers mark up PDFs, which are printed, signed, scanned, and uploaded again, despite the presence of model-based coordination tools. Or the infamous “redlines” that still pass physically between departments in organisations boasting of digital capabilities.

In one project I observed, a CDE had over 1,200 permission groups, with overlapping rights and no documentation. Every change to access required a ticket to IT, a validation by the BIM Manager, and an approval from a “digital lead” whose role was unclear even to themselves. This was not accidental. It was ritualistic. It was designed for control but not designed well.

The digital transformation of AEC is littered with such examples: tools added on top of tools, not to eliminate bureaucracy but to reproduce it in new forms. An agile process is introduced, and within months, it is codified into fixed sprints, gated reviews, and slide decks. We seem to be particularly vulnerable to this form of inertia-in-motion. Rooted in regulatory obligation, insurance requirements, public procurement laws, and inter-organisational complexity, it has built a castle of its own, composed of transmittals, RFIs, submittals, change orders, minutes, logs, stamps, and revisions. Each document a step in the ritual. Each platform — be it Procore, Aconex, or Autodesk Construction Cloud — claims to streamline. But often what they streamline is the ritual itself, not its necessity.

Consider the infamous approval loop for shop drawings in large infrastructure projects. The subcontractor submits. The contractor reviews. The designer checks. The owner comments. The consultant corrects. Then back again. By the time the drawing is finally marked “approved as noted,” the site team has already adapted the solution, off-record, to meet the schedule. The system, in this sense, lags behind the work it governs, like a nervous general fighting yesterday’s war.

And yet — here’s the tragic twist — it persists because it feels safer. The ritual, however hollow, promises a sense of control. Like Kafka’s protagonists, we cling to the process because it is all we have. We fear the chaos that might emerge in its absence. But we rarely ask: what kind of order have we accepted in its place? So what can we do?

3. Digitalisation as ResistanceAs I said, it all began with a promise, and it was a beautiful one. AEC professionals were told that digitalisation would free them from the shackles of fragmented files, unclear drawings, and tedious rework. I know it because I was one of those who promised it.

With BIM came the vision of a single source of truth: models coordinated in 3D space, information embedded, updates reflected instantly. With CDEs came the hope of shared context: stakeholders aligned around a common environment. With Lean Construction, before that, came the mantra of waste reduction, flow optimisation, and respect for people.

Digital tools didn’t just promise to make work faster. They promised to make work make sense again.

To a weary generation of professionals that approached an industry made of pointless paper trails and bureaucratic circularity, this was more than a technological upgrade. It was a declaration of intent: that clarity could be restored, coordination achieved, and time reclaimed not through more meetings, but through smarter systems. In the early days, this hope felt almost revolutionary.

But revolutions are fragile things. And systems, once adopted, have a tendency to reassert control.

You all know the quote…3.1. Platforms, Dashboards, and the Allure of Control

You all know the quote…3.1. Platforms, Dashboards, and the Allure of ControlThe platformization of AEC — where every workflow is absorbed into a dashboard, every decision logged, every model federated — offered the dream of control, and who could resist that dream? Dashboards show progress. Logs document accountability. Analytics promise insight. For executives, this is governance with a UX. But here’s the twist Kafka might appreciate: in seeking transparency, we often create new opacity. As permissions multiply, data validation rules tighten, and workflows lock into “best practice” templates, the system that once promised agility becomes yet another guardian of inertia. The dashboard may be real-time, but the people behind it are waiting for access, for clarity, for permission. When a model is held hostage by locked parameters or a platform demands metadata for a minor revision, agility collapses under the weight of its own infrastructure. Like the Castle, the system functions… well, technically at least. But why it functions, how it empowers (or disempowers), becomes increasingly unclear. We can see everything, and understand nothing.

And yet, resistance lives on.

It’s the one on the left, in case you’re wondering…3.2. The Digital Architect as Insurgent: Scripting, Automating, Circumventing

It’s the one on the left, in case you’re wondering…3.2. The Digital Architect as Insurgent: Scripting, Automating, CircumventingWithin this landscape, a new figure emerges: the digital insurgent. She is the architect who writes Dynamo scripts to batch-edit model parameters that the platform refuses to expose. He is the BIM Coordinator who reverse-engineers IFC exports to strip out proprietary clutter. They are the teams using Notion boards, private Slack channels, and shared Google Drives to bypass clunky approval systems that slow real collaboration.

This is not sabotage. This is pragmatic resistance: the art of circumventing friction without breaking the system. It is motherly in its care for the team’s sanity, heroic in its defiance of slow decay, and rebellious in spirit: if the process no longer serves the work, then let the work reshape the process.

The scripting architect doesn’t wait for permission: they write the workaround.

But this raises a deeper question: why must resistance be necessary at all? If digitalisation was meant to liberate, why has it required an underground? In Kafka’s world, even the smallest act of rebellion — like asking the purpose of a form — was subversive. In ours, writing a script to fix a naming convention can be equally transgressive. And yet, this is where the future lies. Not in replacing bureaucracy with more software, but in reclaiming agency within and against the software we are given.

That’s why we teach our architects to code, or at least we try to. Not because automation is the future, but because insurgency must be fluent in the language of its captors. Let’s see how.

4. Subversion in the SystemOk, so, digital tools were meant to clean up the mess: streamline communication, reduce friction, enforce consistency. And yet, behind every formally approved workflow lies a second life: undocumented, flexible, human. That, in the words of many veterans of project delivery, is how shit actually gets done. The rebel lives not in protest but in practice, but the battleground is increasingly digital.

4.1. “Work-arounds” and Shadow IT as Digital DisobedienceLet us call things by their real names: the Excel sheet duplicated from the CDE, updated manually but shared instantly? That’s a protest. The Power BI dashboard built from an exported CSV because the official analytics suite “takes too long”? That’s sabotage. The script that auto-generates parameters to bypass a field validation? That’s civil disobedience in digital form and, of course, I admire it by default.

These acts of everyday insurgency say: the system is not serving us, so we will bend it, bypass it, or build around it. Shadow IT — those unofficial tools and workflows that live just outside sanctioned platforms — is not a failure of policy but a symptom of unmet need.

Kafka showed us that resistance in a bureaucratic system is rarely loud. It is often quiet, ambiguous, hard to trace. Today, it might look like a technician who uses an old version of Revit just because it runs an AddOn the new one broke. Or like a team that coordinates real decisions in WhatsApp, while uploading sanitised notes to the project portal. These actors aren’t trying to break the rules because they don’t understand them: they’re trying to get home in time for dinner.

4.2. The Informal Layer: Chats, Calls, Networks of TrustTrust shouldn’t flow through permissions but through people. It still does, even when you don’t see it. Beneath every formal digital platform is an informal layer: the Teams call that actually decides what the minutes will say; the email that quietly settles a coordination issue without escalating it; the chat thread where real opinions are voiced, before the sanitised version is submitted.

This layer is alive with risk and reward. It bypasses bureaucracy, but also bypasses record. It’s the lifeblood of agility, and the loophole through which liability slips.

To pretend it doesn’t exist is managerial fantasy, and to demonise it is organisational hypocrisy. The better path is to acknowledge, nurture, and give form to this informal layer not by formalising every word, but by designing systems that trust users without abandoning traceability. As Donna Haraway reminds us: staying with the trouble means living with imperfection, not purging it.

4.3. Organisational “Kafka-beaters”: Hacking Bureaucracy with Humane TechEvery system has its K — someone caught in its gears, bewildered but determined — but some organisations foster a different figure: the Kafka-beater. This is the professional who understands the system and how to outsmart it, not to undermine it, but to make it work better for everyone.

The Kafka-beater writes the onboarding manual that actually tells you where to find the real project files, knows which approval gates are performative and which are enforced, builds plug-ins to streamline drawing exports because the out-of-the-box tools add unnecessary steps. They are hackers, in the noblest sense: people who believe that systems should serve humans, and not the other way around.

These figures are rarely recognised in org charts. They exist in liminal spaces: power users, digital mentors, senior interns who quietly reconfigure folders because no one else will. They are heroic, yes, but not because they fight dragons. They are heroic because they fight friction. And they keep the machine running when the manual fails.

They are the kind of people I look for during the early stages of a transition to BIM because, with a little nudge, they’ll be your champions. If we want humane digital organisations, we must find and support our Kafka-beaters, give them room to script, to question, to challenge defaults. Let them redesign workflows instead of presenting out-of-the-box solutions. Let them train others in quiet resistance. The future isn’t built solely by compliance. It’s built by those who know when — and how — to say: no, but like this instead.

August 29, 2025

Mediterranée 2050: a Journey into the Future of the Sea

I first discovered the exhibition almost by chance, when a friend suggested we visit the aquarium in Monaco on our way back from a vacation and, as we approached the Musée Océanographique, your eyes might miss the towering poster on its facade: a luminous vision of a whale rising from a sea of electric blue.

The experience is an immersive exhibition: you are welcomed by the crew of the voyage, whose faces and voices appear on sleek panels that prepare you for departure as a spaceship, and then you’ll cross the threshold into a historical wing of the museum that has been entirely transformed into the hull of a submarine. Through the journey, the Mediterranean reveals itself as if you were aboard a craft silently gliding beneath the waves, moving through an underwater universe that feels at once familiar and alien, scanning the wildlife with different instruments and suspended between beauty and dread. Looming from the ceiling, the room’s original exhibits: skeletons of whales, dolphins and other majestic creatures create a counterpoint to the live exemplars you see swimming from wall panel to wall panel.

What makes this voyage even more extraordinary is the setting itself: the aquarium’s historic building, with its ornate architecture and aura of timeless grandeur, provides a fascinating contrast to the futuristic narrative unfolding within its walls, and this tension between old and new makes every step feel like a crossing of thresholds, as if the very stones of the palace are whispering while the immersive rooms push you forward into the unknown.

The technology that brings this vision to life is combining cutting-edge projections, enveloping soundscapes and state-of-the-art sync between screens combine to create an environment that doesn’t just show you the Mediterranean as an environment that demands respect but allows you to feel it, as if you were truly submerged in a living, shifting ocean where whales pass overhead, schools of fish scatter at your approach, and the looming consequences of human action ripple across the waters in real time.

August 28, 2025

Fairytale Friday – The Dead Mother

In a certain village there lived a husband and wife—lived happily, lovingly, peaceably. All their neighbors envied them; the sight of them gave pleasure to honest folks. Well, the mistress bore a son, but directly after it was born she died. The poor moujik moaned and wept. Above all he was in despair about the babe. How was he to nourish it now? how to bring it up without its mother? He did what was best, and hired an old woman to look after it. Only here was a wonder! all day long the babe would take no food, and did nothing but cry; there was no soothing it anyhow. But during (a great part of) the night one could fancy it wasn’t there at all, so silently and peacefully did it sleep.

“What’s the meaning of this?” thinks the old woman; “suppose I keep awake to-night; may be I shall find out.”

Well, just at midnight she heard some one quietly open the door and go up to the cradle. The babe became still, just as if it was being suckled.

The next night the same thing took place, and the third night, too. Then she told the moujik about it. He called his kinsfolk together, and held counsel with them. They determined on this; to keep awake on a certain night, and to spy out who it was that came to suckle the babe. So at eventide they all lay down on the floor, and beside them they set a lighted taper hidden in an earthen pot.

At midnight the cottage door opened. Some one stepped up to the cradle. The babe became still. At that moment one of the kinsfolk suddenly brought out the light. They looked, and saw the dead mother, in the very same clothes in which she had been buried, on her knees besides the cradle, over which she bent as she suckled the babe at her dead breast.

The moment the light shone in the cottage she stood up, gazed sadly on her little one, and then went out of the room without a sound, not saying a word to anyone. All those who saw her stood for a time terror-struck; and then they found the babe was dead.

Next Friday: The Dead Witch

The second story will serve as an illustration of one of the Russian customs with respect to the dead, and also of the ideas about witchcraft, still prevalent in Russia. We may create for it the title of—

August 27, 2025

Who’s Afraid of hBIM?

There’s something uncanny about building a model of a building that predates the idea of modelling itself. A Romanesque church, a Baroque theatre, a medieval stronghold—they were never drawn in plan, never imagined in 3D software. And yet, here we are, holding laser scanners, waving drones through ancient courtyards, chanting acronyms like LOA as if they were their non-capitalised version. It feels like summoning a ghost. Or worse: taming one.

Oh, great, the poltergeist in the mannequin has gone rampant again.

Oh, great, the poltergeist in the mannequin has gone rampant again.This is where the fear begins.

Not fear in the gothic sense (although working under a groaning 15th-century timber roof will certainly give you that), but fear as resistance, friction, and complexity. Fear as the creeping suspicion that the model — the promise of digital control, clarity, and coordination — might not be able to hold the richness, the mess, the irregular beauty of heritage. That, in trying to formalise the past, we might end up flattening it. That in translating memory into geometry, we might forget what made it matter in the first place.

In the world of fantasy fiction, the artefact that gives you power also often comes with a price. BIM, in the heritage field, is not so different. It offers dazzling powers: precise inventories, condition tracking, structural simulations, long-term management potential. The dream of an eternal, federated, interoperable model that holds every stone and story. It’s no wonder institutions and funding bodies crave it: it feels like certainty in a field riddled with ambiguity.

But then comes the cost: bloated files, semantic gaps, clashing agendas, broken workflows. The digital model, like a too-perfect copy of a thing, starts to feel… off. Like the skin of a dragon wrapped around a pigeon. Accurate, maybe. Alive? Not quite. Meaningful? Don’t make me laugh.

This isn’t to say information modelling for heritage is a bad idea. Far from it. But its adoption is uneven, hesitant, fragmented. Not because it lacks functionality, but because it asks for a different kind of trust, a trust that heritage professionals are not always ready to give to a system built for concrete slabs and HVAC systems. And can you blame them? Asking a medieval historian to encode the meaning of a tympanum into a “Property Set” is like asking a bard to recite The Silmarillion in spreadsheet form.

Yet here’s the paradox: if we want to preserve, understand, and share these buildings in a world increasingly shaped by data, we cannot ignore the digital and BIM, though not born to fit this purpose, might be the best set of processes and tools we have. But to meet that challenge, we must first name the obstacles. And the fear.

So, who’s afraid of hBIM?

Maybe everyone, a little. And maybe that’s not a bad thing. Because fear, as every storyteller knows, is just the beginning of a better story.

Except these guys. These guys aren’t afraid of hBIM.1. Not Built to Code: when History defies Standards

Except these guys. These guys aren’t afraid of hBIM.1. Not Built to Code: when History defies StandardsHeritage buildings are stubborn. They’re not made to comply, and they never asked to be modelled. They lean, sag, deviate. They betray their own blueprints, if such things ever existed, and respect physical maquettes that did not survive. Their geometries are closer to textual math than drawings, their proportions a whisper of hands long dead. This is where the standard tools of BIM authoring — with their precision, repetition, classification — begin to unravel. Because parametrising a column that never wanted to be symmetrical is a whole different endeavour.

Let’s be clear: BIM loves regularity but doesn’t need it. What it needs is method. It thrives on types, categories, modules. In a contemporary building, a window is a type. It has dimensions, materials, behaviors. It belongs to a class, with siblings that all look alike in a certain way. It fits into a wall that was plumbed by a laser and defined in a spreadsheet. But in a 16th-century monastery, every window is a cousin of the next: almost alike, never identical. That niche was widened in 1742. That wall leans because of the earthquake of 1908. That vault never matched the one on the other side, and nobody ever thought it should.

My students know very well the example of Rosslyn Chapel, possibly one of the peak examples of a creativity spanning from providing specifications instead of drawings.

My students know very well the example of Rosslyn Chapel, possibly one of the peak examples of a creativity spanning from providing specifications instead of drawings.But try to feed that into your favourite BIM authoring tool. It resists. It blinks. It tries to round the angle p to 90, to normalise the arc. Suddenly, you’re no longer modelling the building: you’re correcting it. You’re scrubbing away its accidents, its age, its soul.

Field example? A simple one. Surveying a Romanesque apse, we found that each rib in the vault deviated by a few centimetres from the ideal radial pattern. It wasn’t a mistake, but an adaptation to a skewed base geometry. But try to model it in Revit: the moment the user tried an array, the other ribs became “wrong.” The ones on site, of course, not the ones in the model, because that’s how the mind of the lay operator works. Unless, of course, you abandon the family logic and start modelling each one as a unique object. Which defeats the efficiency of BIM, but preserves the truth of the building. So, which do you serve?

This is where typology fails: the notion that buildings can be abstracted into types and families, predictable patterns and standard rules. It works in textbooks. It collapses in cloisters.

This looks regular. It’s not.

This looks regular. It’s not.Historical architecture isn’t anti-type because it’s chaotic. It’s anti-type because it’s particular. Because it was built under constraints we no longer recognise: the availability of stone from a quarry five kilometres away; the skill of a mason on that particular day in 1456; the fear of collapse prompting a last-minute change in the angle of a flying buttress. These aren’t quirks: they’re highly valuable data. But they don’t fit neatly into any known standard.

And so, we bend. Or fudge. Or abandon BIM entirely, retreating to mesh models, point clouds and textured scans that preserve appearance but lose structure, material logic, or annotation capability.

This tension — the unmodelable within the model — is not a signal, a sign that our tools, as powerful as they are, were forged in a different age, for different battles. They are made for control, repetition, and prediction. Heritage buildings demand interpretation, forgiveness, and curiosity. And that’s why I think every student should have a field experience in surveying and modelling one of these beauties: to remember that our tools might be suitable in a context, but vary the context and they become obsolete.

We weren’t working in BIM, but we needed the 3d, and the point cloud of these beams still gives me nightmares…

We weren’t working in BIM, but we needed the 3d, and the point cloud of these beams still gives me nightmares…To use a videogame metaphor: if BIM is great for building highly complex LEGO, hBIM is closer to restoring a puzzle where half the pieces are missing, and the picture on the box has been painted over three times by monks, masons, and bureaucrats. There’s no “snap-to-grid.” You must look, listen, and choose. That’s the outlaw way: to model not in spite of the irregularities, but because of them. To let the building teach you how to model it, not the other way around.

So no, these buildings weren’t built to code. But maybe the code can learn to listen.

2. Drawing Ghosts: from Reality Capture to Selective ReconstructionLet’s admit it: the point cloud is seductive. It hovers in digital space like a ghost: flickering, floating, hyper-real. It shows everything and…. well, nothing. A billion measured points suspended in silence. When you first orbit around a high-resolution photogrammetric model of a vaulted nave or a war-torn façade, it feels like magic, like you’ve captured the truth, like you can finally stop guessing and just model what you see.

Take a look at the ghost cell project, if you don’t believe me.

Take a look at the ghost cell project, if you don’t believe me.But here’s the twist: the moment you start building a BIM from that scan, you realise you’re not capturing reality. You’re translating it. Filtering it. Interpreting it. The scan is not a model: it’s a veil, a suggestion, and what lies behind it is not certainty, but choice. Reality Capture is the name we give it in polite software brochures. But for heritage, it’s closer to Reality Imagination. Because what the scanner gives you is just the skin: the material logic is missing, the hierarchy is up to you. It’s up to you to bring into a model the knowledge of why that arch cracks here but not there. The cloud provides no understanding of how many times the plaster was redone. You need to look for the record of what was lost.

This is where Scan-to-BIM becomes Interpret-to-BIM. And interpretation is not neutral.

Let’s say your scan reveals a vaulted ceiling obscured by scaffolding. Occlusion. What do you do? Reconstruct the vault from symmetry? Fill in the blanks using a mirror of the other half? Or do you mark it as “unknown”? Every choice you make has consequences. Every curve you trace on top of the point cloud isn’t just a model but a statement, a subjective reconstruction. Sometimes a guess. This is where the ghosts begin to speak.

And it’s often not happy

And it’s often not happyField example? A 19th-century theatre, partially burned in a fire. The scan was complete on the surviving side, vague and noisy on the collapsed zone. We were asked to “model it as it was.” But how? Based on symmetry? Historic photographs? Drawings that contradicted each other? In the end, we offered two models: one based on remaining geometry, one on conjectural reconstruction. The client was confused. “Which one is right?” they asked. Both and neither, darling, both and neither.

The point is that the scanner doesn’t give you history: it gives you shape, and shape alone is not enough.

Here, heritage modelling takes on the tone of a necromancer’s spell. You’re rebuilding the dead from fragments: a stone here, a groove there, the ghost of a door that was filled in, the faint imprint of an altar. Except in this necromancy, you can’t conjure: you need to imagine what once was, based on what is, and that’s not technical work. That’s storytelling. Which is fine, so long as we’re honest about it.

It’s the difference between the actual Natalie and N.A.T.A.L.I.E., if you get my reference.

It’s the difference between the actual Natalie and N.A.T.A.L.I.E., if you get my reference.The danger comes when we confuse precision with truth. A model may have been extracted from a point cloud with a Level of Accuracy to 3mm, and still be wrong in its logic. That arch may be perfectly modelled, and still misunderstood. That wall may be orthogonal in the scan but sloped in history, rebuilt after a quake, subtly rotated by time. Fidelity is not the same as authenticity but, in the digital space, they wear the same clothes.

The Mirror shows you what is, what was, and perhaps what could be… but never tells you which is which. The skill lies in knowing when you’re looking at a reflection, and when you’re looking at a guess wrapped in laser dots.

The Mirror shows you what is, what was, and perhaps what could be… but never tells you which is which. The skill lies in knowing when you’re looking at a reflection, and when you’re looking at a guess wrapped in laser dots.So yes, scan it. Model it. But remember: you are not drawing facts. You are drawing ghosts. And they deserve respect, or they’ll wreak havoc on your model.

But what does that actually mean?

3. Building what, exactly? The Question of PurposeHere’s a question we don’t ask nearly enough: what is the model for? The concept of model use becomes even more crucial in the complex territory of modelling heritage and yet, in the rush to digitise, to scan and segment and attribute, this question often gets quietly pushed aside, buried under funding reports, software licenses, and a collective excitement about “innovation.” Let’s do the model and keep it as a record, and then we’ll be able to use it… for what? I’m telling you for what. For nothing. The question of model use haunts every project like a silent NPC in the corner of the map: blinking, untriggered, waiting to be talked to. And when you finally do, it changes everything. The inconvenient truth is that you can’t build the right model if you don’t know what the model is meant to do.

I feel I’ve been screaming that in the desert for decades now.

I feel I’ve been screaming that in the desert for decades now.Is the model meant as a record? Then maybe accuracy and fidelity are your priority, and you model everything, even the cracks. Is it a tool for conservation management? Then perhaps you simplify, prioritise materials and condition states, and align with conservation workflows. Is it a digital twin? Then you’ll need sensors, live data, behaviour modelling: a whole infrastructure that most heritage buildings aren’t even wired for. Or then again, is it a narrative? An educational object, a museum exhibit, an act of digital storytelling?

These aren’t minor forks in the road: they are different planets. And yet, most hBIM projects try to be all things to all people… and end up satisfying none.

This pizza is called “4 seasons”. The only reason for this pizza to exist is for 8-year-old me, who would get bored eating a whole pizza, but I’ve yet to find anyone who actually likes it. Much like there’s no model suitable for all seasons.

This pizza is called “4 seasons”. The only reason for this pizza to exist is for 8-year-old me, who would get bored eating a whole pizza, but I’ve yet to find anyone who actually likes it. Much like there’s no model suitable for all seasons.This is the heart of the problem: use-case opacity. We build detailed, data-rich models without ever defining who will use them, for what, when and how. It’s like crafting a sword without knowing the hand that will wield it. Elegant, yes. Sharp, maybe. Useful? That depends on whether you’re in a duel or slicing bread.

In a recent project for a historic urban compound, the architects wanted layered phasing to understand spatial evolution. The conservators needed material stratigraphy and degradation patterns. The facility managers demanded simple zoning and maintenance sheets. The engineers were after structure, not stone type. The digital twin team wanted to plug in IoT sensors. And the client wanted a fly-through video. It’s pointless to even try to make one model serve them all. The result would be a Frankenstein’s monster of overmodeled parts, conflicting parameter sets, and a barely functioning interface that no one will want to open twice. That’s what happens when everyone contributes, but no one owns the purpose.

This isn’t just a workflow problem, if you don’t mind me throwing words around: it’s an epistemological one. Each discipline approaches the building with a different set of questions. Whene a conservator sees material and decay, an architect sees form and function. An engineer sees forces and tolerances. A software designer sees data structure and interface. A historian sees meaning. You can’t flatten that into one file and expect it to sing.

What we need is multi-model awareness. Interlinked data. Aggregated, maybe. But not collapsed into one unwieldy everything-bagel of data.

Think of the building like a polyhedral artefact, each side revealing a different attribute. One interface for structure. One for meaning. One for geometry. One for storytelling. Trying to wrap them all into one map means no one can read it. But give each hero their own lens? That’s when the party starts to work together. So, before we draw a single line, we must ask:

4. Rebuilding Meaning: a Cultural Model of ModellingWho is this for?

What will they do with it?

What don’t they need?

Let’s imagine, for a moment, that a building is not a structure but a story. A story made of stone, wood, plaster, and time, shaped by the rituals it hosted, the hands that built it, the ones that broke it, and the ones that tried to fix it. Some parts are clear: walls, beams, thresholds. Others are hidden: memories, symbols, absences. When we model heritage, we’re not just capturing geometry but we’re capturing this layered narrative, and we aren’t trained to do so. We should be.

Because if all we do is reproduce form, we’re modelling the corpse, not the soul.

That’s the uncomfortable truth. BIM, at its core, is a geometric and parametric tool. It models what things are: walls, windows, slabs. It links them to how they’re built: materials, dimensions, quantities. But heritage often demands something deeper: the why. Why was this space added in 1724? Why is that arch broken but untouched? Why does no one walk under that lintel? These whys matter in new construction too, but in heritage they are not optional. They are what give the building its cultural weight. Strip them away, and you’ve got an empty shell. Worse: a lie made of polygons.

To rebuild meaning, we need a different mindset. A cultural model of modelling that doesn’t stop at “what it is,” but asks “what it means,” “who it mattered to,” and “how it changed.” It’s a philosophical shift, and it starts with semantics.

Ontologies like CIDOC-CRM offer a glimpse of what’s possible. Designed for cultural heritage documentation, CIDOC lets you describe not just “object X was made of material Y,” but “object X was used in ritual Z by person W at time T,” it can track provenance, usage, symbolic meaning, even gaps in knowledge. It’s messy. It’s rich. It’s human.

Often, when you bring that into a BIM environment, it feels like playing Dungeons & Dragons in a spreadsheet. You can do it, and I have, but you can’t deny that it kills the vibe for most of us.

Some brave souls are trying to bridge the gap with dedicated data structures and property sets, extending IFC schemas to accommodate cultural dimensions. “Monumental status,” “associated legend,” “ritual use,” “period of significance.” It’s a start. But it’s hard, because most BIM authoring tools don’t know what to do with meaning. You can write “sacred threshold” into a parameter field, but it won’t show up in a schedule. It won’t trigger a clash detection. It won’t export cleanly. It just sits there, like a forgotten line of lore on an old game cartridge.

Still, we try. Sometimes, the model is not meant to be smart or accurate. Sometimes, it’s meant to be true.

Take the case of a small village chapel we once documented to be used in a videogame environment. Structurally insignificant. Architecturally modest. But socially immense. It had no clear typology. No repeated elements. Just one altar, an oddly shaped apse, and a doorway always kept half-open. Model the shadow line that fell across the floor at dusk, because that’s when the ritual will begin. How do you do that? A reference plane, a timestamp, a coded instruction: “When this line crosses this angle, unleash the creature.” That was the moment the model became a story. And I’ll be damned if that’s not what people call 4d BIM.

So here’s your nudge, if you’re still reading: model the story. Use tags if you must. Use linked documents. Use auxiliary databases. Invent new parameters. Draw from the game masters and the lorekeepers and the scribes. If the tool doesn’t let you write down meaning, build around it. Or break it. Someday, someone will open your model not to renovate the wall, but to understand what the wall meant. And when they do, may they find more than surfaces and steel. May they find the ghost, still whispering in the geometry.

August 25, 2025

Disneyland Paris – A guide if you’re afraid of heights

And I don’t mean “you get slightly dizzy”, nor do I mean motion sickness, which is signalled at the entrance of the attractions but it’s a totally different thing: I mean a grip to your stomach when the attraction climbs upwards and a voice in your head as it plunges to everyone’s doom, screaming we’re all going to die; I mean limbs shaking for the next 30 minutes and the sense of depth completely gone bananas. That’s what I mean. Do you have it, and you’re planning to go to Disneyland, but you’re not sure if you’ll manage to ride on any ride? You’re in the right place: I got you.

I went to Disneyland Paris + Studios this summer with a couple of friends, who were aware of my issue with heights and went above and beyond to try and select attractions that wouldn’t bother me, but it’s a tricky thing, and it isn’t easy to explain. Some of their assumptions were correct (no roller coasters being the most obvious one, of course), some doubts were confirmed, and some other times we didn’t expect what happened. So here I am, here’s what we did and here’s my advice if you’re in the same situation.

Let’s star with…

…should I go?Yes, yes, yes.

You might skip many attractions, that’s true, but if you’re with the right group and you can ditch the company when they want to be thrown up in the air, a visit to the park is worth it if only for the shows, the shops, and the walking around in a truly magical place. And you’ll have things you can do, I promise.

I mean, just take a look at that.

I mean, just take a look at that.I’ll split the attractions in 3 categories: nope, maybe, absolutely yes.

1. One Big Bag Full of NopeThese of course are the rides I did, because my friends and I thought they might be okay, and turned out not to be okay. I’m not counting the rollercoasters and such, because it’s obvious that they will bother someone who can’t cope with heights.

1.1. RatatouilleYes, you heard me right. The fluffy attraction with your favourite little chef Remy… isn’t fluffy at all. And while the ride is literally glued to the ground, curved screens will give you the impression of falling from the skylight into the kitchen as the very first thing, and there’s nowhere to look (a trick I usually employ to reset my brain to the reality that we’re not falling). The illusion is complete, the immersion is a masterpiece… which of course isn’t good.

Do avoid.

1.2. Star Tours

1.2. Star ToursThis is not a simulator. I repeat, this is not a simulator. Or, more appropriately, it’s a fucking good one. Taking your glasses off won’t help, and again, there’s nowhere to look because you’re in a moving capsule. The illusion of acceleration, plunging to your death, diving to avoid enemies and all that jazz is really, really well done. I don’t know how they do it. I don’t care. Stay out of it.

2. Call Me Maybe

2. Call Me MaybeThese are attractions that will have a bad moment, but it’s literally just one, and maybe you can cope for the sake of everything else. It’s up to you. Avoid them if you want to stay on the safe side.

2.1. Peter PanYou’re sitting in a boat that’s literally hanging from a rail on the ceiling. Sometimes you look down at stuff that’s 50 cm from the keel, other times you’re dangling higher. From the way it tosses and turns, it will give you the illusion of wanting to go wild, except it doesn’t: one time it rolls as if it’s about to plunge to your doom, but the descent isn’t that steep. Overall it’s charming, I think it’s worth the mild discomfort of that single slide.

2.2. Pirates of the Caribbean

2.2. Pirates of the CaribbeanI know. I’m really sorry to report this: the boat slides down at the beginning of the ride, which is nothing, but then there’s a steep descent around the middle of the ride and… it’s not good. It’s the only time it will do it: there’s another one by the end but it’s way milder. I’m really angry because there’s literally no need for it, but there you have it. Be prepared.

2.3. Spider-Man W.E.B. Adventure

2.3. Spider-Man W.E.B. AdventureI didn’t do this one (I was still feeling sick from Ratatouille). You’re in a moving capsule with 3d glasses, and they warn you against motion sickness, but my significant otter tells me there’s no falling, no sliding, no nothing. And the spider-bots are super cute.

2.4. Snow White and Pinocchio

2.4. Snow White and PinocchioI didn’t do these either (yes, Ratatouille was that bad): you’re supposedly sitting in a cart that just turns abruptly as it happens in very old rides of haunted houses.

2.5. Robinson’s HouseIt didn’t bother me, because it’s an attraction you traverse by foot, and I manage much better when I’m in control, but it does climb pretty high, and at least one lady didn’t make it. I did enjoy the walk, but if you have doubts, I don’t think it’s worth the trouble. The same might go for Adventure Island, which was close when we visited: it’s just a walk, but there’s a hanging bridge which might bother some.

3. Go for it

3. Go for itThis is the good news section. There’s a bunch of stuff you traverse by foot, and it literally just has regular stairs: Sleeping Beauty’s Gallery, inside the castle, featuring some beautiful stained glass scenes from the cartoon, Alice’s Labyrinth, where the most thrilling part is the stairs to the Queen of Hearts’ Castle (if you can find it), and the Dragon’s Cave.

Other walks will stay at ground level, such as Aladdin’s Enchanted Passage, which is a gallery with scenes from the movie, and the Nautilus where you’ll take a stroll inside Captain Nemo’s masterpiece.

But what about the rides?

3.1. It’s a Small WorldSurprisingly to nobody, this is a very chill ride on boats: Walt Disney’s nightmare of children singing all together in different languages coms to life and it’s really lengthy, traversing stereotype after stereotype with your dutiful dosage of diversity and inclusion (or at least that’s what I think they think they’re doing). You have to see it to believe it.

3.2. The Railroad

3.2. The RailroadIt’s what you expect: the train takes you through the park and stops in the different districts, going through a couple of tunnels with dioramas and giving you a special look from above inside the Pirates of the Caribbeans attraction.

3.3. The Carousel

3.3. The CarouselA classical ride with horses and, if you feel like sitting down, carriages that won’t lift off the ground. My eight-years-old neighbour was complaining that we weren’t going fast enough: it was fine for me.

3.4. Once Upon a Time

3.4. Once Upon a TimeAnother chill ride on boats: you’ll travel on a river that will take you through miniatured scenes of your favourite cartoons and, most notably, it’s the only time Winnie the Pooh has a spot in the park. It surely is a conspiracy.

3.5. Phantom Manor

3.5. Phantom ManorDefinitely my favourite attraction, and the only way it might bother you is if you’re afraid it’ll do something funny. It won’t. Trust me. Not even the slightest, not even when it looks like we might be facing a descent. It’s perfect. You’ll love it.

August 23, 2025

Kusa-Meikyu

Kyoka Izumi, born Kyotaro Izumi on November 4, 1873, in Kanazawa, Ishikawa, was a prominent Japanese novelist, writer, and kabuki playwright active during the prewar period. He is best known for his distinctive style that contrasted with the dominant naturalist literature of his era: his works often featured surrealist critiques of society and romantic tales with supernatural elements influenced by Edo period arts and literature. Izumi’s writing is celebrated for its rich, stylistic prose, and he is considered one of the supreme stylists in modern Japanese literature.

Izumi began his literary career under the mentorship of Ozaki Koyo, a leading literary figure of the time, serving as his houseboy while receiving instruction. His first published work appeared in 1893, and he later gained recognition for stories that vividly depicts melodramatic and often implausible characters and supernatural themes. Some of his noteworthy works include “The Holy Man of Mount Koya” and “A Woman’s Pedigree.”

Kusa Meikyu, translated in Italian as Labyrinth of Grass, is from 1908. It was originally a novel and has been adapted into other formats, including a notable short film released in 1979. The work includes elements of surrealism and the supernatural, with dreamlike and mystical narratives. A haunted house, a set of characters, a fateful night. The translation I have could use a ton of footnotes, as you’re left with the notion of having missed half of the point between plays on words and theatrical references. Even the linguistic barrier, though, can’t shield the way the story builds up and unravels, between heaven and hell, in a handful of hours.

You’ll crawl through the first half and then you won’t be able to put it down.

August 21, 2025

Fairytale Friday – The Fiend

In a certain country there lived an old couple who had a daughter called Marusia (Mary). In their village it was customary to celebrate the feast of St. Andrew the First-Called (November 30). The girls used to assemble in some cottage, bake pampushki, and enjoy themselves for a whole week, or even longer. Well, the girls met together once when this festival arrived, and brewed and baked what was wanted. In the evening came the lads with the music, bringing liquor with them, and dancing and revelry commenced. All the girls danced well, but Marusia the best of all. After a while there came into the cottage such a fine fellow! Marry, come up! regular blood and milk, and smartly and richly dressed.

“Hail, fair maidens!” says he.

“Hail, good youth!” say they.

“You’re merry-making?”

“Be so good as to join us.”

Thereupon he pulled out of his pocket a purse full of gold, ordered liquor, nuts and gingerbread. All was ready in a trice, and he began treating the lads and lasses, giving each a share. Then he took to dancing. Why, it was a treat to look at him! Marusia struck his fancy more than anyone else; so he stuck close to her. The time came for going home.

“Marusia,” says he, “come and see me off.”

She went to see him off.

“Marusia, sweetheart!” says he, “would you like me to marry you?”

“If you like to marry me, I will gladly marry you. But where do you come from?”

“From such and such a place. I’m clerk at a merchant’s.”

Then they bade each other farewell and separated. When Marusia got home, her mother asked her: “Well, daughter! have you enjoyed yourself?”

“Yes, mother. But I’ve something pleasant to tell you besides. There was a lad there from the neighborhood, good-looking and with lots of money, and he promised to marry me.”

“Harkye Marusia! When you go to where the girls are to-morrow, take a ball of thread with you, make a noose in it, and, when you are going to see him off, throw it over one of his buttons, and quietly unroll the ball; then, by means of the thread, you will be able to find out where he lives.”

Next day Marusia went to the gathering, and took a ball of thread with her. The youth came again.

“Good evening, Marusia!” said he.

“Good evening!” said she.

Games began and dances. Even more than before did he stick to Marusia, not a step would he budge from her. The time came for going home.

“Come and see me off, Marusia!” says the stranger.

She went out into the street, and while she was taking leave of him she quietly dropped the noose over one of his buttons. He went his way, but she remained where she was, unrolling the ball. When she had unrolled the whole of it, she ran after the thread to find out where her betrothed lived. At first the thread followed the road, then it stretched across hedges and ditches, and led Marusia towards the church and right up to the porch. Marusia tried the door; it was locked. She went round the church, found a ladder, set it against a window, and climbed up it to see what was going on inside. Having got into the church, she looked—and saw her betrothed standing beside a grave and devouring a dead body—for a corpse had been left for that night in the church.

She wanted to get down the ladder quietly, but her fright prevented her from taking proper heed, and she made a little noise. Then she ran home—almost beside herself, fancying all the time she was being pursued. She was all but dead before she got in. Next morning her mother asked her:

“Well, Marusia! did you see the youth?”

“I saw him, mother,” she replied. But what else she had seen she did not tell.

In the morning Marusia was sitting, considering whether she would go to the gathering or not.

“Go,” said her mother. “Amuse yourself while you’re young!”

So she went to the gathering; the Fiend was there already. Games, fun, dancing, began anew; the girls knew nothing of what had happened. When they began to separate and go homewards:

“Come, Marusia!” says the Evil One, “see me off.”

She was afraid, and didn’t stir. Then all the other girls opened out upon her.

“What are you thinking about? Have you grown so bashful, forsooth? Go and see the good lad off.”

There was no help for it. Out she went, not knowing what would come of it. As soon as they got into the streets he began questioning her:

“You were in the church last night?”

“No.”

“And saw what I was doing there?”

“No.”

“Very well! To-morrow your father will die!”

Having said this, he disappeared.

Marusia returned home grave and sad. When she woke up in the morning, her father lay dead!

They wept and wailed over him, and laid him in the coffin. In the evening her mother went off to the priest’s, but Marusia remained at home. At last she became afraid of being alone in the house. “Suppose I go to my friends,” she thought. So she went, and found the Evil One there.

“Good evening, Marusia! why arn’t you merry?”

“How can I be merry? My father is dead!”

“Oh! poor thing!”

They all grieved for her. Even the Accursed One himself grieved; just as if it hadn’t all been his own doing. By and by they began saying farewell and going home.

“Marusia,” says he, “see me off.”

She didn’t want to.

“What are you thinking of, child?” insist the girls. “What are you afraid of? Go and see him off.”

So she went to see him off. They passed out into the street.

“Tell me, Marusia,” says he, “were you in the church?”

“No.”

“Did you see what I was doing?”

“No.”

“Very well! To-morrow your mother will die.”

He spoke and disappeared. Marusia returned home sadder than ever. The night went by; next morning, when she awoke, her mother lay dead! She cried all day long; but when the sun set, and it grew dark around, Marusia became afraid of being left alone; so she went to her companions.

“Why, whatever’s the matter with you? you’re clean out of countenance!” say the girls.

“How am I likely to be cheerful? Yesterday my father died, and to-day my mother.”

“Poor thing! Poor unhappy girl!” they all exclaim sympathizingly.

Well, the time came to say good-bye. “See me off, Marusia,” says the Fiend. So she went out to see him off.

“Tell me; were you in the church?”

“No.”

“And saw what I was doing?”

“No.”

“Very well! To-morrow evening you will die yourself!”

Marusia spent the night with her friends; in the morning she got up and considered what she should do. She bethought herself that she had a grandmother—an old, very old woman, who had become blind from length of years. “Suppose I go and ask her advice,” she said, and then went off to her grandmother’s.

“Good-day, granny!” says she.

“Good-day, granddaughter! What news is there with you? How are your father and mother?”

“They are dead, granny,” replied the girl, and then told her all that had happened.

The old woman listened, and said:—

“Oh dear me! my poor unhappy child! Go quickly to the priest, and ask him this favor—that if you die, your body shall not be taken out of the house through the doorway, but that the ground shall be dug away from under the threshold, and that you shall be dragged out through that opening. And also beg that you may be buried at a crossway, at a spot where four roads meet.”

Marusia went to the priest, wept bitterly, and made him promise to do everything according to her grandmother’s instructions. Then she returned home, bought a coffin, lay down in it, and straightway expired.

Well, they told the priest, and he buried, first her father and mother, and then Marusia herself. Her body was passed underneath the threshold and buried at a crossway.

Soon afterwards a seigneur’s son happened to drive past Marusia’s grave. On that grave he saw growing a wondrous flower, such a one as he had never seen before. Said the young seigneur to his servant:—

“Go and pluck up that flower by the roots. We’ll take it home and put it in a flower-pot. Perhaps it will blossom there.”

Well, they dug up the flower, took it home, put it in a glazed flower-pot, and set it in a window. The flower began to grow larger and more beautiful. One night the servant hadn’t gone to sleep somehow, and he happened to be looking at the window, when he saw a wondrous thing take place. All of a sudden the flower began to tremble, then it fell from its stem to the ground, and turned into a lovely maiden. The flower was beautiful, but the maiden was more beautiful still. She wandered from room to room, got herself various things to eat and drink, ate and drank, then stamped upon the ground and became a flower as before, mounted to the window, and resumed her place upon the stem. Next day the servant told the young seigneur of the wonders which he had seen during the night.

“Ah, brother!” said the youth, “why didn’t you wake me? To-night we’ll both keep watch together.”

The night came; they slept not, but watched. Exactly at twelve o’clock the blossom began to shake, flew from place to place, and then fell to the ground, and the beautiful maiden appeared, got herself things to eat and drink, and sat down to supper. The young seigneur rushed forward and seized her by her white hands. Impossible was it for him sufficiently to look at her, to gaze on her beauty!

Next morning he said to his father and mother, “Please allow me to get married. I’ve found myself a bride.”

His parents gave their consent. As for Marusia, she said:

“Only on this condition will I marry you—that for four years I need not go to church.”

“Very good,” said he.

Well, they were married, and they lived together one year, two years, and had a son. But one day they had visitors at their house, who enjoyed themselves, and drank, and began bragging about their wives. This one’s wife was handsome; that one’s was handsomer still.

“You may say what you like,” says the host, “but a handsomer wife than mine does not exist in the whole world!”

“Handsome, yes!” reply the guests, “but a heathen.”

“How so?”

“Why, she never goes to church.”

Her husband found these observations distasteful. He waited till Sunday, and then told his wife to get dressed for church.

“I don’t care what you may say,” says he. “Go and get ready directly.”

Well, they got ready, and went to church. The husband went in—didn’t see anything particular. But when she looked round—there was the Fiend sitting at a window.

“Ha! here you are, at last!” he cried. “Remember old times. Were you in the church that night?”

“No.”

“And did you see what I was doing there?”

“No.”

“Very well! To-morrow both your husband and your son will die.”

Marusia rushed straight out of the church and away to her grandmother. The old woman gave her two phials, the one full of holy water, the other of the water of life, and told her what she was to do. Next day both Marusia’s husband and her son died. Then the Fiend came flying to her and asked:—

“Tell me; were you in the church?”

“I was.”

“And did you see what I was doing?”

“You were eating a corpse.”

She spoke, and splashed the holy water over him; in a moment he turned into mere dust and ashes, which blew to the winds. Afterwards she sprinkled her husband and her boy with the water of life: straightway they revived. And from that time forward they knew neither sorrow nor separation, but they all lived together long and happily.

Another lively sketch of a peasant’s love-making is given in the introduction to the story of “Ivan the widow’s son and Grisha.” The tale is one of magic and enchantment, of living clouds and seven-headed snakes; but the opening is a little piece of still-life very quaintly portrayed. A certain villager, named Trofim, having been unable to find a wife, his Aunt Melania comes to his aid, promising to procure him an interview with a widow who has been left well provided for, and whose personal appearance is attractive—“real blood and milk! When she’s got on her holiday clothes, she’s as fine as a peacock!” Trofim grovels with gratitude at his aunt’s feet. “My own dear auntie, Melania Prokhorovna, get me married for heaven’s sake! I’ll buy you an embroidered kerchief in return, the very best in the whole market.” The widow comes to pay Melania a visit, and is induced to believe, on the evidence of beans (frequently used for the purpose of divination), that her destined husband is close at hand. At this propitious moment Trofim appears. Melania makes a little speech to the young couple, ending her recommendation to get married with the words:—

“I can see well enough by the bridegroom’s eyes that the bride is to his taste, only I don’t know what the bride thinks about taking him.”

“I don’t mind!” says the widow. “Well, then, glory be to God! Now, stand up, we’ll say a prayer before the Holy Pictures; then give each other a kiss, and go in Heaven’s name and get married at once!” And so the question is settled.

From a courtship and a marriage in peasant life we may turn to a death and a burial. There are frequent allusions in the Skazkas to these gloomy subjects, with reference to which we will quote two stories, the one pathetic, the other (unintentionally) grotesque. Neither of them bears any title in the original, but we may style the first—

Next Friday: The Dead Mother

August 20, 2025

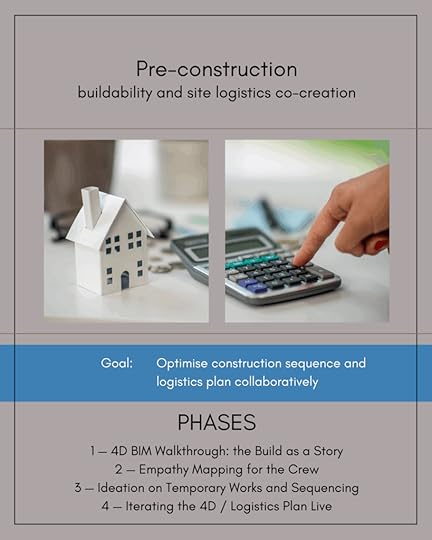

Design Thinking: a Compass for Innovation in BIM and Construction

The construction industry seems to be always standing at a crossroads: since Vitruvius started idealising Greek architecture and ignored the technological advancements of his time, it’s an age-old giant, weighed down by inertia, struggling to keep pace with a world that demands flexibility, transparency, and human-centred solutions. Despite flashes of progress, too often innovation feels like window dressing: information models polished to perfection but disconnected from true collaboration, digital tools sold as salvation yet deployed as bureaucracy in disguise.

What we see is a landscape of partial transformations: buildings rise higher, but the processes behind them remain anchored in outdated hierarchies and fragmented communication. It’s a world where efficiency is measured by how well teams follow rigid plans, rather than how well they adapt, listen, and learn. And all the while, construction sites remain battlefields of delay, waste, and rework.

This is not a technological problem alone, of course. It’s a problem of mindset: of how we frame challenges, how we involve people, and how we dare to break free from the damn “this is how it’s always been done” mentality. The need for change is existential.

The dystopian landscape of construction innovation (and why we need a new map)In this environment, Design Thinking offers more than just a method: it offers a compass. Not the kind that points to a single solution or a one-size-fits-all process, but one that orients us toward what truly matters: people, purpose, and possibilities.

After all, we’re not trying to find North, are we?

After all, we’re not trying to find North, are we?A new map is needed: one that helps us navigate complexity without falling into the trap of oversimplification; one that embraces uncertainty as fuel for better outcomes rather than something to fear. The map we need does not chart a fixed route. Instead, it helps teams chart their own course, one built on empathy, experimentation, and reflection. For construction — an industry that builds the spaces where life happens — this shift is not just about improving margins or timelines, but about making the act of building itself more humane, more intelligent, and antifragile.

That being said, let’s see what Design Thinking is and, most importantly, what it’s not.

1. Design Thinking: A Tool More Than a Spell1.1. Origins: from IDEO to the motherlode of creative problem-solvingDesign Thinking as a methodological approach was forged in the gritty reality of solving complex human problems. Its modern roots trace back to the work of IDEO, a design firm that became synonymous with radical creativity applied to the everyday: how to make medical equipment safer, how to design a better shopping cart, how to humanise technology. The practice is a synthesis, a motherlode of methods drawn from engineering, architecture, anthropology, psychology, and the arts. It formalised what great designers had done instinctively for centuries: focus on people, explore ideas widely, and prototype fearlessly.

The term Design Thinking became popular as a way to bring these methods to fields beyond design, to business, education, healthcare. It’s a mindset and a toolkit meant for anyone who dares to see problems differently.

1.2. What Design Thinking is: empathy, experimentation, iteration — the tri-force of innovationAt its heart, Design Thinking is powered by three forces — not spells, not shortcuts — three enduring practices that together shape better outcomes:

Empathy: the courage to see the world through others’ eyes. In construction, this means understanding not just clients, but the end users who’ll inhabit our buildings, the workers who’ll assemble them, and the communities they’ll impact. Empathy rejects assumptions and asks: what do people truly need?Experimentation: the willingness to try, fail, and try again. Instead of endless meetings and theoretical debates, Design Thinking pushes teams to prototype, to give ideas form early and often, so flaws and opportunities surface before it’s too late.Iteration: the discipline of continuous refinement. Design Thinking doesn’t aim for perfection on the first try. It embraces cycles of testing, feedback, and improvement. This isn’t a weakness: it’s the secret to resilience in the face of complexity.These three forces form the tri-force of innovation. They won’t hand you the final answer, but they’ll equip you to build it, step by step, with your team.

1.3. What Design Thinking is not: a formula, a checklist, or a silver bullet for lazy empiresDesign Thinking’s rise in popularity has, sadly, attracted misuse. Let’s be clear about what it is not:

Not a formula. You can’t reduce Design Thinking to a flowchart or a set of sticky notes on a wall. True Design Thinking is messy, dynamic, and context-driven. It asks for judgment, not just compliance.Not a checklist. Running through “empathy interviews” or “ideation sessions” without genuine intent doesn’t make a project innovative. The value lies in how deeply teams engage with each phase, not in ticking boxes.Not a silver bullet. Design Thinking won’t fix broken organisational cultures on its own. It’s not a branding exercise for lazy empires trying to seem human-centred while clinging to outdated hierarchies. It’s not a magic word that, once uttered, transforms a rigid project into a creative marvel.To wield Design Thinking well means to respect its depth and its demands. It requires humility, curiosity, and grit, traits that no template can supply.

There’s no silver bullet for this kind of problem, sorry.2. Misconceptions and Traps

There’s no silver bullet for this kind of problem, sorry.2. Misconceptions and TrapsDesign Thinking, when wielded with integrity, can reshape how teams approach complexity. But like any powerful tool, it’s vulnerable to misuse. Here are the traps where many well-intentioned innovators — and their projects — fall.

2.1. The “template thinking” pitfallDesign Thinking invites exploration, empathy, and courage. But too often, it gets reduced to an empty ritual: sticky notes on the wall, neatly labelled stages, a well-designed slide deck that looks good in the boardroom but means nothing on the ground. This is template thinking: the illusion that creativity can be pre-packaged, applied uniformly, and produce brilliance on demand.

The danger here isn’t just wasted effort. Template thinking breeds cynicism. Teams go through the motions without questioning their assumptions or challenging the brief. They mistake activity for progress. And soon, the language of Design Thinking becomes hollow, another buzzword.

In construction, this pitfall is particularly treacherous. It’s easy to slap a “Design Thinking workshop” label onto a kickoff meeting, or to run a token brainstorming session between technical reviews. But unless the approach shapes decisions, structures dialogue, and informs real choices, it’s window dressing. The building may stand, but the opportunity to build better is lost.

2.2. The illusion of linearity: why Design Thinking is no cheat codeAnother common trap is treating Design Thinking as a straight-line process: Empathise → Define → Ideate → Prototype → Test → Success

As if following the sequence guarantees a winning solution, like entering the right combination in a game to unlock the next level.

But the real world doesn’t work this way, and Design Thinking is nonlinear by nature: teams loop back, reframe the problem, revisit insights, discard ideas, and start again.

In construction, where projects unfold across long timelines and multiple disciplines, this illusion of linearity is especially dangerous. It encourages teams to rush through the early stages — “We’ve done empathy; let’s move on!” — and lock in flawed assumptions that become costly to undo. Design Thinking’s strength lies in its flexibility, not in offering a cheat code to bypass uncertainty.

2.3. When “Design Thinking” gets hijacked by corporate overlordsPerhaps the most insidious trap is when Design Thinking is hijacked by organisations that use its language to mask business-as-usual. The terminology — empathy, co-creation, iteration — gets tacked onto projects that are, at their core, no more inclusive or innovative than before. Corporate overlords (whether in construction firms, consultancies, or client organisations) may promote Design Thinking as part of their “transformation agenda,” while simultaneously clinging to rigid hierarchies and control structures. The result? A hollow theatre of innovation. A circus in which clowns wear ties. The death of Design Thinking happens in workshops where outcomes are pre-decided, prototypes that will never see the light of day, feedback sessions where the only acceptable input is praise.

In the context of BIM and construction, this often manifests as token gestures: a design sprint that fails to inform the BIM execution plan, or a “user workshop” that’s essentially a branding exercise. The promise of Design Thinking is subverted, often not through malice but through a force far more dangerous: the fear of real change.

3. So what do we do? A motherly word of cautionThese traps aren’t inevitable. But avoiding them takes vigilance, honesty, and the willingness to ask tough questions. Are we truly listening? Are we open to rethinking? Are we using Design Thinking to serve people or to serve appearances?

3.1. The paradox of rigidity and chaos in constructionConstruction is a sector of contradictions. On paper, it is one of the most structured industries on Earth. Rigid codes, standards, contractual frameworks, and layers of approvals are designed to bring order to the colossal task of shaping the built environment. Every detail is documented, reviewed, and locked into place long before the first brick is laid or the first bolt is fastened. And yet, anyone who’s ever been on site knows the amount of chaos that lurks beneath this façade of control. Projects routinely run over budget, over schedule, and under expectation. Coordination failures, design clashes, procurement delays, and change orders are so common they’re practically baked into the process and the construction site, intended as the culmination of careful planning, often becomes a battlefield of last-minute fixes and creative firefighting.

This paradox — rigid structure breeding unpredictability — is a symptom of systems that focus on managing risk through control, rather than through adaptability and collaboration. It’s an industry trying to impose certainty where uncertainty is intrinsic.

3.2. Traditional project delivery models: the slow death of creativityMost construction projects still follow delivery models that slice the process into silos: architects design, engineers calculate, contractors build, and users — if they’re lucky — provide input after the fact. Creativity is expected only in the early design stages; after that, the mission is to stay on course, avoid disruption, and tick the boxes. But in this environment, creativity fades, suffocates. By the time a project reaches construction, opportunities for innovation — in materials, methods, sustainability, or user experience — have been sealed off by contracts, budgets, and a mindset of let’s just get it done.

BIM was supposed to change this. And to some extent, it did. But too often BIM is treated as a fancy documentation tool rather than a true enabler of collaboration and exploration. Without the mindset shift that Design Thinking offers, BIM risks becoming just another layer of bureaucracy, a digital straightjacket instead of a creative scaffold.

3.3. Why the industry craves a rebootBehind the statistics on waste, rework, and carbon emissions is a quieter truth: the people who work in construction are hungry for change. Engineers, designers, project managers, tradespeople: most know the system is broken. They see the human cost of delay, conflict, and short-sighted decisions. They feel the frustration of seeing good ideas discarded because that’s not how we do things. The industry craves a reboot, not just in technology, but in mindset. A shift from compliance to curiosity, from controlling complexity to engaging with it, from building faster to building wiser. The only ones who claim not to see how broken this industry is, are those who are profiting from these delays, conflicts, confusion and rot. And they’re those we should be bringing down with a vengeance.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the boss fight: it’s a crafting session