Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 41

December 16, 2023

#Advent Calendar Day 17: the Pope’s Pie

The villain in this sequence was a pike, in case you’re wondering.Recipe:For the pastry:

The villain in this sequence was a pike, in case you’re wondering.Recipe:For the pastry:Build a small volcano with the flour, break the eggs in the crater and work everything together with the salt. Pour water on it little by little until the dough is elastic and not too soft. It’s going to be sticky, so you need to dust your hands with more flour. Also, remember that the water needs to be cold and so do your hands, or else the eggs in the mixture start misbehaving and the dough — as we say in Italy — goes crazy.

Chop the butter into pieces and incorporate it in the mixture as well, work it into the dough until you no longer see the pieces but this requires for the mixture to warm a bit, so you’ll want to be quick about it. As soon as you’re satisfied, drop the dough in cellophane or in a cold cloth, and throw it into the fridge. Three hours is the optimum, but half an hour usually suffices.

Bring the almond milk to a boil and cook the rice in it. Do not overcook it: you’re not trying to make a pudding, so you won’t have to wait until all the milk has been absorbed by the rice. Twenty minutes should suffice. Maybe less. Then pick it up with a strainer. You will need the rice but you won’t need the milk anymore, so you’d better find another use for it.

Clean the fish and remove all bones unless you want to kill your guests. Place the boiled fish inside a pan, add the ground almonds, the pine nuts, the sugar, the cooked rice, and mix it all together with a pinch of salt.

Grease a pan with butter, lay the pastry, pour the filling inside and then cover it with another layer of pastry. Brush it with the egg yolk and then sprinkle it with the ground cinnamon.

Cook at 180 °C in the oven for around 50 minutes.

Sturgeon?Oh yeah. In Italian tradition, sturgeon is a bit like caviar and, since it was already considered food for the rich, it’s of course connected with the Pope.

One of the earliest testimonies around sturgeon and caviar dates back to 1570 when Bartolomeo Scappi, private chef to Pope Pius V, created a menu entirely based on caviar and sturgeon. Other testimonies come from Cristoforo da Messisbugo (1557) and Bartolomeo Stefani (1663), who contributed to creating recipes and crafts of caviar production in Italy.

According to Ars Italica, 16th-century painting provides testimonies of the presence of sturgeon in Italy: in the painting Fish Sellers by the Cremonese Vincenzo Campi, the background shows us a faithful representation of one of the three native Italian kinds of sturgeon.

Legend also has it that Leonardo Da Vinci himself, upon seeing a sturgeon from Ticino, had the idea of giving its precious eggs enclosed in a casket set with stones and gems to Beatrice d’Este during her wedding banquet with Ludovico Sforza.

December 15, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 16: Pike in Ale and Herbs

Behead the pike, rub its body with ground salt until it stops sweating and then gut it. Remove the entrails, and throw the good ones (the ones without biles, juices or other unpleasant stuff) into a quarter of liter of water with the ale and a pinch of salt: you’re going to boil everything until it shrinks down to something you can use for garnish when the pike is baked.

Meanwhile, mix the finger and cinnamon, rosemary, marjoram, thyme, parsley and savoury, and stuff them into the guts of the pike.

Place the fish inside a pan with a curl of butter on top, and bake it until it’s cooked. Slice it and serve it with the ale-based fish stock.

Savoury‘For to seth a pyke. Kill him in the head. Stick and take a handful of great salt. Rub him till the flewme go from him. Open him at the belly and take out the refete, and take out the gall and strip all the small guts and cast them away and save the great gut. Take a fair clean pan and a quart of fair water. Take a quart of new ale and a dish full of este and take 2 handfuls of salt and cast therein. Take a little ginger and cinnamon and cast thereto rosemary, marjoram, thyme and parsley and a little savory, and break all these herbs in two. Cast in the pan. If he be not well refete, cast in a little suet butter but seethe it.’

The etymology of the genus name for this herb, Satureja or santoreggia in Italian, is uncertain. Linnaeus derived the name from an ancient Roman word whose Latin root satura means satiated: this was a reference to the digestive properties of the plants in this genus, actual or supposed. Another etymology would derive the name from sauce to indicate the aromatic properties of this plant in cooking. The English word refers to a Latin name for the “savoury herbs”, and some scholars believe it was Satureja that Virgil recommended to plant near beehives. Pliny mentions a satureia as a herb for culinary use, possibly derived from the Arabic sattur.

Beato Angelico’s Childhood of Christ (2)

Yesterday I published an overview of this temporary display at the Museo Diocesano here in Milan.

Today, as promised, I give you a piece-by-piece rundown.

The first quadrant is the most complex: it depicts two concentric wheels: an inner one alternates the four Evangelists with their effigies alternated to St Peter, Iudas, Jacobs and Paul; an outer one represents twelve prophets and Saints to symbolise the harmony between the New and the Old Testament.

The AnnunciationThe scene is a fairly traditional one, symmetrical, with the archangel Gabriel kneeling on the left and the Virgin Mary on the right. The scene was very dear to the painter, who came back on it multiple times.

The background of this version is a Renaissance-style loggia and features two symbols that infuriate me: the hortus conclusus, the closed garden, and the sealed fountain, fons signatus, both associated with Mary’s virginity. And while I understand the thing with the closed garden, though I cannot help but find it rather vulgar, it’s the thing with the fountain that infuriates me, as it associates purity not with the lack of intercourse but with the abstinence from pleasure, a thing that has absolutely nothing to do with physical virginity. The stigma on feminine pleasure starts from there, and we’re still paying for it so yeah, fuck them all.

Nativity SceneThe shack occupies the entirety of the scene, with Joseph and Mary flanking it like the sides of a theatre scene, and the infant Christ laid on the bare ground. He’s the main source of light, while the other one is up top, with the adoring angels. Shepherds dressed as friars are peeking from the sides, stealing the thunder of a charming landscape with hints of a castle that we can only imagine being Herod’s.

CircumcisionThis one is the first scene set indoors, and critics have identified the scene as the apse of San Marco in Florence, constructed by Michelozzo and well-known by the painter. The unnatural position of the baby Christ recalls the crucifixion, and the scene is painted with painstaking attention to detail.

Since a baby is circumcised ten days after birth, and there are twelve days between Christmas and the Epiphany, we can only assume Beato Angelico is telling us the Holy Family moved somewhere to perform the operation and then rushed back to their shack to greet the Three Wise Men (see following panel).

Since I think the practice of circumcision is a disgusting mutilation that holds zero medical reasons nowadays, I won’t show you this panel.

Adoration of the Three Wise MenWe’re back at the Nativity scene, as I was saying, and we have the Three Wise Kings coming to bring gifts. The tradition of depicting the kings as coming from different areas of the world, as you can read on British sources such as this one, has often been depicted as consistent throughout art history but, as we can see here, Beato Angelico depicts them all as white westerners kings. This is a recurring choice, as you can see on the fresco at San Marco in Florence.

Presentation at the TempleThe second indoor scene presents us with a Gothic temple much more similar to a church. The back window frames a symmetrical composition with the baby Jesus wrapped in a cloth that looks a lot like a burial shroud because it’s the season to be jolly, but Mary has her hands raised in another very human gesture, as if she’s struggling to let him go. The other figures are Saint Anne, the grandmother, and Saint Simeon, a character appearing in Luc’s Godspel: he was an elderly at the temple, a transitional prophet like Saint John the Baptist, and he gave praise when he was presented with the child. His prayer, known as the Nunc dimittis in the Latin version, it was thus translated in the Vulgata:

Flight to EgyptNow thou dost dismiss thy servant, O Lord, according to thy word in peace;

Because my eyes have seen thy salvation,

Which thou hast prepared before the face of all peoples:

A light to the revelation of the Gentiles, and the glory of thy people Israel.

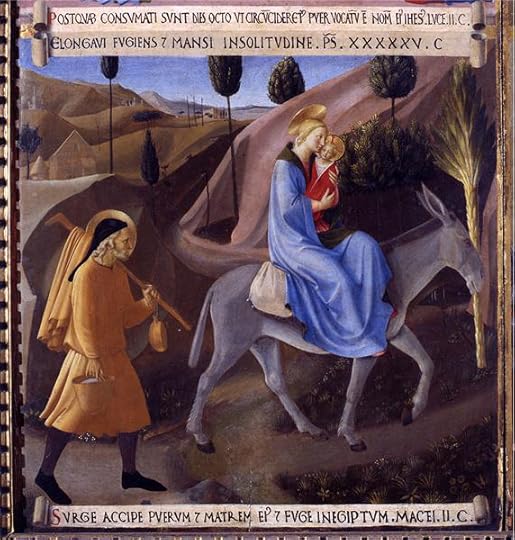

Though Christ is represented frontally and appears rather stiff in his red robe, the Virgin Mary’s sitting is natural, and the caring way she wraps her arms around the child radiates a human tenderness rarely seen in contemporary compositions. Joseph follows rather than leading, and this is also unusual for the time.

Massacre of the InnocentsDefinitely my favourite scene of the composition, far from being lyrical or polished. Compare it, if you will, with Giotto’s representation of the same scene in the famed Scrovegni Chapel in Padua: there, the most dynamic part of the composition is one soldier grabbing a child by the leg and his mother clinging to him, raising her head to the sky in desperation, but that’s it. The other mothers are all crammed at the back, the pile of dead children lies unattended in between.

Beato Angelico shows us a scene with mothers who fight back, who don’t shun pushing back the soldiers, who put themselves in between their blades and their children. They’re not presented as meek, suffering bystanders, and one of them scratches the face of the soldier who’s piercing her child, drawing blood. The children are slaughtered in a very graphical way too, bring much more drama to the whole scene.

December 14, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 15: Partridge in Ginger Sauce

This recipe comes from Moira Buxton‘s Medieval Cooking Today, which in turn takes inspiration from the Harleian manuscript collection nr. 4016.

Ingredients (serves 6 people):3 partridges;a pinch of ground cloves;a pinch of ground mace;1 litre of beef stock;150 ml of red wine, plus at least a glass for drinking;1 tablespoon of whole black peppercorns;2 hard-boiled egg yolks (you can eat the white as a snack while you cook, with that glass of red wine you saved before);half a teaspoon of ground ginger;a pinch of powdered saffron;a pinch of salt;6 slices of toasted bread.cranberry jelly (optional).Recipe:Stuff the birds with ground cloves and nutmeg, tie their legs together, bring the beef stock to a boil and throw them into the broth, with the peppercorn and the wine. A French light red wine is recommended here, like a Beaujolais.

Lower the heat and skim off the surface foam for the first five minutes. This might or might not happen, depending on how the skin of the bird has been treated in the butchery. If it doesn’t, hold onto your butcher.

Cover with a lid and simmer until the birds are soft: it should take around twenty minutes. When you think they’re done, remove them from the saucepan and cut them lengthwise into halves because only a lunatic cuts them the other way. Do not throw away the cooking liquid and refrain from drinking it.

Place each half on a dish, atop a slice of bread, and store it somewhere warm but not in the heated oven because the plate will mostly likely explode.

Meanwhile, blend in a bowl the squashed egg yolks, the ginger, the saffron, a pinch of salt and a suitable amount of the cooking broth so that it will turn into a sauce that’s not too liquid.

Pour it over the birds and serve. You can accompany this with cranberry jelly.

First of all, let me tell you that I completely understand if you hate me and you’re thinking: “where the hell am I going to find a fucking partridge?”

I know.

Sorry.

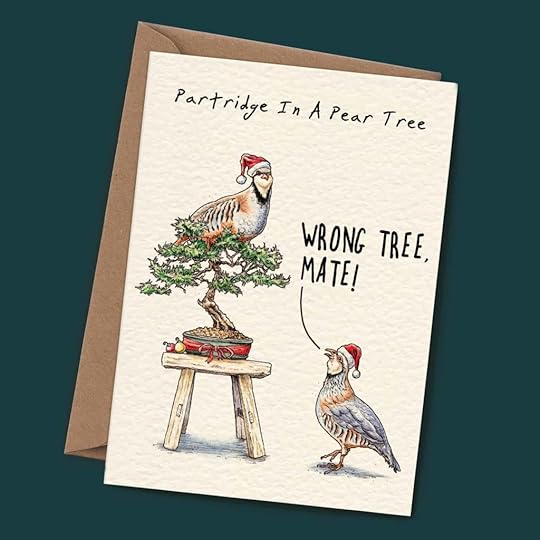

In my defence, partridges are very festive and, for some reasons, it’s the one gift you’ll get on Christmas from your true love. If you’re not British and have no idea what I’m talking about, head here. It’s one of my favourite versions.

According to Greek legend, the first partridge was born from Perdix, the nephew of the famous inventor Daedalus, when he threw him off the sacred hill of Athena in a fit of jealous rage because he had invented the saw. Supposedly mindful of his fall, the bird does not nest on trees and avoids high places. I honestly cannot blame it.

In the Middle-Ages, it became a food of love, at least according to Madeleine Pelner Cosman in her 1983 “A Feast for Aesculapius: Historical Diets for Asthma and Sexual Pleasure”:

“Partridge was superior in arousing dulled passions and increasing the powers of engendering. Gentle to the human stomach, partridge stimulated bodily fluids, raised the spirits, and firmed the muscles.”

Since the partridge will die to protect her young, it has been suggested that at a certain point, this total devotion to love had it connected with Christ, hence the impossible partridge in a pear tree featured in the famous Christmas song.

If you’re into the 12 Days of Christmas, you simply must check out the set illustrated by Iain at Bewilderbeest. They’re all hilarious.

If you’re into the 12 Days of Christmas, you simply must check out the set illustrated by Iain at Bewilderbeest. They’re all hilarious.

Beato Angelico’s Childhood of Christ (1)

Every year around Christmas, Milan’s Museo Diocesano temporarily hosts a masterpiece: last year, it was the predella from the Oddi Altarpiece, an Annunciation scene by Raphael, while in 2021 we had another Annunciation scene by Titian. This year, the initiative surpasses itself with one of the most complex and articulated works of Fra Giovanni da Fiesole, better known as Beato Angelico.

The set of miniatures comes from a piece called Armadio degli Argenti, an ex-voto door commissioned by Piero de’ Medici who wanted to build a family chapel in the Santissima Annunziata in Florence. Since he finished paying for it in 1453, we can only assume it was painted between that date and 1451, when the chapel didn’t have any roof yet. Beato Angelico would die in 1455, aged sixty, and yet the scenes attributed to him present an innovative quality in both composition and arrangement.

Nowadays we have 35 tablets left arranged on four boards, though originally there were probably 41. Three scenes on the vertical panel are attributed to Alesso Baldovinetti, who was working with him back at the time, and twenty-three more were probably outlined by an assistant who was working with Beato Angelico. The whole cycle represents all the stages in the life of Christ: his childhood, public life, passion, death and resurrection. The museum in Milan only hosts the works from the first portion, the childhood.

The scenes ascribed to the childhood of Christ, a period the canonical texts tell us very little about, are eight:

Ezekiel’s Vision;Annunciation;Nativity Scene;Circumcision;Adoration of the Three Wise Men;Presentation at the Temple;Flight to Egypt;Massacre of the Innocents.The last scene, Jesus at the Sanhedrin, usually marks the transition between his childhood and public life.

Flight to Egypt.

Flight to Egypt.The exposition of the panel is set up on the first floor of the museum (it’s one of the most underrated museums in Milan, and if you’ve never been there, I highly recommend a visit), and it consists of three rooms: an introductory one, a video installation with enlargements of the scenes, and another room with the main thing.

The enlargements are absolutely necessary, and I suggest you double back to see it after you’ve admired the original because some of the details are too tiny to see.

That’s all I can give you today: tomorrow I’ll publish a piece-by-piece runthrough.

December 13, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 14: Pork Meatballs with Currants

This recipe is based on an XV-century English Manuscript called Harleian #279, and was expanded upon by Maggie Black‘s Medieval Cookery: Recipes and History.

Ingredients:1 kg of cubed pork;1 liter of beef stock;300 ml of almond milk (you know how to do this from the Capons in Dorre recipe);6 tablespoons of currants;1 teaspoon of ground nutmeg and another teaspoon for garnishing;half a tablespoon of ground cloves;half a tablespoon of ground black pepper;a pinch of salt;2 eggs;a chunk of butter for frying;flower petals and edible violets for garnishing;2 tablespoons of sugar (yeah, it’ll make sense in a minute).Recipe:Cube the pork and cook in the beef stock until it turns whitish on the outside: it’ll still be pinkish on the inside, but that’s what we want. Then strain and keep the stock: you’ll need it.

Transfer half of the stock into the saucepan, add the almond milk, and mince the pork in smaller cubes, mixing it with currants and all the spices, adding a couple of eggs to keep it together.

Shape the mixture into balls and fry them in butter.

Now for the weird part.

Place the meatball onto a serving platter, sprinkle with sugar and the nutmeg, decorate with violets and petals, and serve to your puzzled guests.

I swear they’re good.

They are the forefathers of the Swedish meatballs, with currants worked into the mixture. Picture taken from here.Currants?

They are the forefathers of the Swedish meatballs, with currants worked into the mixture. Picture taken from here.Currants?Currants, also called Black Corinth raisins, are dried berries that come from seedless grapes. Not to be confused with its red variety called Ribes, which was first produced in Belgium and northern France in the XVII century, Zante currants is one of the oldest known raisins. The first written record of the grape was made in by Pliny the Elder in 75 AD, and he described a tiny, juicy grape which surprisingly enough doesn’t seem to be an aphrodisiac. During the XIV Century, Venetian merchants started selling them to the English market under the label Reysyns de Corauntz, and the name raisins of Corinth was recorded in the XV century. Gradually, the name was altered to simply currants, creating a lot of confusion.

Osias Beert the Elder, Dishes with Oysters, Fruit, and Wine

Osias Beert the Elder, Dishes with Oysters, Fruit, and Wine

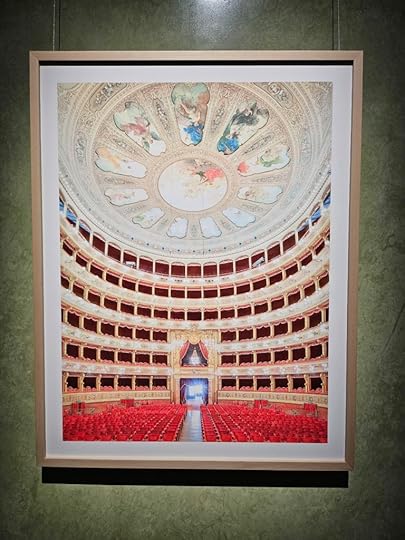

Theatre: the Architecture of Wonder

The new exhibition at Palazzo Reale, showcasing works by Patrizia Musso, complements the inauguration of the new operatic season at La Scala, a theatre that makes a point of not doing anything people might like (if I see again the Dame aux Camélias I might scream). It is part of many events organized throughout the city in a (vain) attempt to raise some interest for the opening opera of choice, Verdi’s least exciting work Don Carlos.

An Exhibition of Photographs?Not precisely, though the website at Palazzo Reale describes it that way.

Sixty large-format pictures of theatre interiors telling a story of transition from the first theatres in Vicenza, Sabbioneta and Parma, more courtyards than buildings, to grand palaces like La Scala in Milan, the San Carlo in Naples, the Fenice in Venice, the Argentina in Rome, the Massimo in Palermo, complemented by some particularly scenographic architectures that present the whole world as a theatre, such as the Royal Palaces in Venaria or Caserta. Flicking through magazines, you’ll see dreamlike pictures engulfed with light, often with frontal vision, total focus and super-exposure.

But.

If the photos almost look as if they’re coloured with pastels, it’s because they are. After taking a photograph, Mussa prints it on cotton paper and retraces details with colours, turning it into a watercolour or a tapestry.

A stunning multi-sensorial experience“A work of rigour and rethinking, a look with half-closed eyes, the triggering of a dreamlike process, of unravelling, of impoverishment, the search for a root, for a soul, for another meaning; a kind of X-ray, of retinal or cortical snapshot, imprinted on a thin veil.”

As if the stunning setting of the Prince’s Apartments were not enough to complement these wonderful pictures, Alessia Dettori works with the Scent Company and diffuses scents of white flowers like tuberose, rosehip and talc, with a crown of geranium, freesia, magnolia, violet. Famous arias are streamed through the rooms, mostly from Mozart’s Don Giovanni (I guess they couldn’t find one single palatable thing from Don Carlos, and that’s understandable), and you walk through the rooms in complete awe.

1. The original theatre in Milan was a Courtyard theatreAs Milan’s mayor Giuseppe Sala tells us in his introduction to the exhibition, the Royal Palace in Milan was furnished, like most European royal residences, with a resident theatre. It was called the Court Theatre and was first built as a temporary set-up for ceremonies and festivities, before becoming permanent.

Being constructed almost entirely of wood, the Court Theatre was destroyed by fire many times, and later rebuilt. The last time this happened, however, the flames incinerated it completely.

Maria Theresa of Austria decided then to donate a new theatre to the city, to be used not only by the court but by all the citizens. The Church of Santa Maria della Scala was demolished and, in its place the current Teatro alla Scala was built in its place, inaugurated in 1778 with an opera written by Salieri.

The first room is dedicated to this part of history, the Court Theatre, reconstructed through a maquette and brought to life by Musso’s shots of an interior that is no more.

On the central table, sketches and plans show us the idea for the new theatre that will become La Scala.

The sketches are partly based on the maquette and partly based on a watercoloured etching from 1747 by Marcantonio dal Re, an artist from Bologna who gives us a view of the interior as it appeared on the celebrations for the birth of Pietro Leopoldo Archduke of Austria.

2. Venaria and Palazzo GrimaniAfter the overview of the Court Theatre, the second room is dedicated to the Venaria Royal Palace near Turin and Palazzo Grimani in Venezia, which is kind of fun since I’m reading Maddalena and the Dark, and the titular Maddalena is Maddalena Grimani, that same Grimani.

The pictures of the court in Venaria are incredible, especially if you’ve ever been there on a sunny winter day. The light flooding the halls is magnificently rendered, and the highlights on the marble floors almost let you hear the ticking of your own heels.

Palazzo Grimani is a different thing: located in Venice in the Castello district, near Campo Santa Maria Formosa, it used to be the residence of the Grimani family since 1521, when Antonio Grimani was doge, and it stayed on as their residence till 1865, until the government acquired it.

The interiors are absolutely stunning, one of the main features being the Antiquarium where a permanent exhibition was inaugurated in 2019 and lots of works that belonged to the Grimani family, including the Ganymede stolen by the eagles, and that’s what Musso decides to represent in one of the most powerful pictures dedicated to Venice.

3. More Venaria, Pavia, Caserta, BresciaThe third room is dedicated to four theatres, one for each wall: alongside the already mentioned Venaria near Turin, we have pictures from the Fraschini Theatre in Pavia, the Court Theatre in Caserta (yeah, the Star Wars one), and the Grand Theatre in Brescia. They’re almost all neoclassical structures, aside from Brescia, which came late at the party but that’s what they do.

Teatro Fraschini, Pavia4. Novi Ligure, Turin, Parma, Vercelli and Florence

Teatro Fraschini, Pavia4. Novi Ligure, Turin, Parma, Vercelli and FlorenceThe Romualdo Marenco in Novi Ligure was built around 1839 following a design by Giuseppe Becchi who almost copied his own Carlo Felice in Genova. The theatre of course wasn’t dedicated to the local composer Marenco, who would be born three years later, and was called Carlo Alberto. The dedication only came in 1943, 37 years after the composer’s death.

Recently renovated, the theatre’s interiors display a stunning eleven-petal daisy on the ceiling, against a luxurious golden background.

Against the green background of the room, red is the main character of these pictures.

Against the green background of the room, red is the main character of these pictures.Much better known is the Royal Theatre in Turin (Teatro Regio), inaugurated in 1740 in rococò style and renovated many times throughout the centuries until, after being destroyed by a fire in 1936, it was rebuilt by Carlo Molino and it opened again in 1973.

The original construction, praised as a source of wonder by Giovanni Gaspare Craveri in his 1753 guide to the city, was commissioned by Vittorio Amedeo II, recently become King of Sardinia, to no other than Filippo Juvarra, royal architect and renowned scenographer who was also responsible for the development of the Royal Palace in Venaria. This theatre too was to replace the Court Theatre in the old San Giovanni palace, and it was a stunning, ambitious space, capable of hosting around 2500 people in the main concert hall. Turin will meber shut up about the fact that Giuseppe Piermarini, tasked with designing the future La Scala theatre in Milan, was ordered to look at the Regio as an example.

After the disastrous fire in 1936 and throughout the war, the theatre remained in ruins. Two incompetent idiots named Aldo Morbelli and Robaldo Morozzo della Rocca won the design competition for its renovation just one year later, it’s not like we wanted to leave it like that, but their project was never brought to light.

At last, the municipality decided to give direction of the project to Carlo Molino, one of the masters of those years. The theatre was reconstructed in six years, with a structural design by the engineering legend Sergio Musmeci.

The Regio Theatre in Parma only shares the name with its counterpart in Turin: constructed as a replacement of the 1689 Teatro Ducale, it was commissioned by Duchess Maria Luisa to the Court Architect Nicola Bettoli, who started construction in 1821 on the grounds of the monastery of Sant’Alessandro. The new theatre was completed after eight years that costed a fortune, and could host 1800 people.

It was then renovated in 1853, when gas lighting was brought in to replace candlelight.

The main feature of the hall is the frescoed ceiling, decorated by Giovan Battista Azzi, who decided to represent the Duchess as a Harmonia, surrounded by a court of dancing maenads.

6. Venice and MantovaWe surpass a room in which we see shots from the Teatro Massimo in Palermo, the San Carlo in Napoli, the Argentina and Teatro Valle in Roma, the Carignano in Torino and the Teatro della Pergola in Firenze, and the court theatre in Caserta. The next room is dedicated to two beloved masterpieces: the Fenice in Venice and the Scientific Theatre in Mantova.

The first one was designed by Giannantonio Selva after winning a design competition, and embodied the republic’s political ideas by proposing boxes with no ranks and no differences. That’s very Venetian of them: all citizens are the same… provided they have the money to actually get into the theatre.

Napoleon decided to redecorate the main room in turquoise and silver, following the new style, and then again new frescoes were implemented by the beginning of the XIX Century following another design competition: Giuseppe Borsato presented designs with Apollon triumphant on a carriage, surrounded by the Muses.

The theatre, owing to his name, burned down the first time in 1836 and was reconstructed with decorations by Tranquillo Orsi, but I was a kid when it was set on fire the second time, and I remember the great stirring it caused.

The current reconstruction is due to Aldo Rossi.

The Scientific Theatre in Mantova is a peculiar one, starting from its name. Also known as Teatro Bibiena, it was commissioned by Count Carlo Ottavio di Colloredo when he was rector of the famous National Virgilian Academy, better known as Accademia dei Timidi. The structure was founded to promote the study of Virgil, but Maria Teresa d’Austria reformed it in 1767, extending its theatrical and poetic scope to scientific research. The theatre was commissioned and constructed within those years: Antonio Galli da Bibbiena designed the building and the interiors, the facade was built by Paolo Pozzo following a design by Giuseppe Piermarini who was too busy to be bothered with it himself.

The interiors are quite warm, with dark red decorations on a golden background, yet Musso manages to bring us her otherworldly signature atmosphere and the lights on the boxes engulf the whole ambient.

7. Valencia, Mondovì and Racconigi, plus La Scala in MilanThe theatre in Mondovì, to which Patrizia Musso dedicates three shots, was built in 1851 by Giovan Battista Gorresio and once was the biggest in the region. Its current conditions have frequently been denounced by many photographers and organizations, including the Fondo Ambiente Italiano, which recurrently proposes it for the Places of the Heart annual competition.

The room also hosts one of the few experiments with outdoors of the exhibition: a shot of the Racconigi Castle greenhouses designed by Pelagio Pelagi. It’s not outdoor, strictly speaking, since glass windows close the right portion of the porch, but it’s close enough, and I think it has nothing to envy to the grand views of halls and foyers.

8. A proper outdoor experiment: CasertaThe proper outdoor experiment is a shot of the famous fountain atop the staircase. The represented scene is Actaeon turned into a deer and attacked by his own dogs, and counters the other fountain where Diana is represented bathing with her nymphs. As the legend goes, Actaeon was a hunter who unwillingly surprised the goddess naked and was transformed, only to be torn apart. Its inclusion in a selection on theatres should be no surprise: the whole garden of Caserta is meant to be a setting for spectacles and transforms nature into a theatre for life.

9. Mantova and the new La Scala TheatreThe last room offers us a view of Palazzo Té in Mantova, and then it completely devotes itself to the project by Giuseppe Piermarini of the new theatre in Milan.

The single shot from Mantova comes from the so-called Horses Hall, a room decorated by Giulio Romano with impressively realistic side views of… well, horses.

The shots from the theatre inside in Milan were particularly charming to me as they were taken during the construction site: plasterboard piles, electrical wires and working tools, absorbed that otherworldly light Patrizia Musso has touching all her pictures, and you’ll find yourself smiling for that touch of blue, that touch of red, that touch of yellow peeking from layers and layers of white light.

The rest of the room is occupied by a maquette of the stage in La Scala for the Europa Riconosciuta.

The exhibition is a stunning one, and Patrizia Musso’s work is absolutely stunning. Delicate and yet powerful, enticing, utterly magical. It positions itself as one of the best exhibitions to be seen in Milan, alongside Van Gogh and Rodin. It’s an exhibition to be walked and re-walked, to be taken in body and soul, and its charm will accompany you while you walk home through the crisp, winter evening.

December 12, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 13: Turnip and Parsnip Soup

You’ll have to prepare this in advance, so I give it to you before. It’s easy if you don’t get distracted, which means it’s difficult for me.

Chop the vegetables into chunks, heat the oil in a pan and then throw them in with the parsley and bay leaf, stirring frequently until they’re brown and soft (let’s say, five minutes). Then add the salt, the water, bring it to a boil and forget all about it. That’s the easiest part. Let it simmer on a lower flame for around 30 minutes, add a pinch of salt and your broth is done. Strain it, and place the vegetables aside: they’re boiled; you can eat them if you’re not feeling well, or you can find something to cook with them. Do not discard them as certain recipes say. There’s nothing wrong with them.

For the soup:Melt the butter in a large saucepan over medium-high heat and then add the chopped onions and parsnips. Cook until the vegetables are lightly caramelized around the edges, for around 4 to 6 minutes, and then add the thyme.

Add the turnips, the broth, a pinch of salt and bring it to a boil, then reduce the heat just as you did for the previous broth and cook everything until the turnips are tender. It should take around 20 minutes.

Remove the thyme and add the cream. You’ll want to add the almonds last, leaving them almost raw. A pinch of chives in each bowl might also be used for garnish.

What’s a parsnip, precious?It’s a root vegetable closely related to carrot and parsley, in Italian we call it pastinaca and… yeah, it’s not really a thing around here anymore, even if the term is Latin and it seemed to be highly appreciated in Roman times, up to the point that Emperor Tiberius accepted part of the tribute from the German provinces in the form of parsnips. Bonvesin da la Riva in his Marvels of Milan (1288) lists the roots amongst the “delicacies” you can enjoy in my city. We’ve come a long way since then.

In Roman times, parsnips were believed to be an aphrodisiac. Nowadays, they are fed to pigs, particularly those bred to make Parma ham, and maybe we can start to believe in the transitive property of love.

Turnips were an important food in the Hellenistic and Roman world, and they travelled far: spreading first to China, they reached Japan by 700 AD. It’s a winter vegetable, usually harvested between January and February, and thus has inspired many popular sayings surrounding their ability to be made stronger by adversities, a characteristic that played well with the Roman’s military propaganda. Marziale himself told us they were Romolus’ favourite food in the afterlife.

According to Plinius, turnips were an aphrodisiac and I’m starting to wonder if this was wishful thinking, since everything seems to have this property if we listen to him.

A German legend tells us that a demon of the night was taking advantage of the sun’s absence to court his fiancée, a Princess, and kidnapped her. Since the woman was lonely, and wished to have some company, the night demon uprooted some turnips and, upon touching them with his magic, turned them into beautiful maidens. They were short-lived, however, and only lasted for the time the root kept its juice.

When the first of them died, the Princess turned the girl back into a bee and sent her to warn the Sun that they were being held captive, but the bee never returned.

When the second one died, the Princess turned her into a cricket and sent her off with the same errand, but she too never came back.

The third one was turned into a stork, and was ultimately successful: she came back with her betrothed, but they both had to flee from the demon. In order to gain some time, the Princess asked him how many turnips he had in his garden, and the demon was forced to count all of them, and this is how the demon is known as Rübezahl, the one who counts turnips. The remaining turnip was turned into a horse, and this is how the Princess was able to flee with the Sun.

A wonderful tiny book on sale here.

A wonderful tiny book on sale here.

White Gold: three centuries of Ginori porcelaine

When the Richard-Ginori porcelain factory first announced they were having financial troubles, my mother declared a day of mourning, and we had to order pizza. They officially declared bankruptcy in 2013 after leaving a scar in the suburban area of southern Milan, where the 1870 factory suddenly shut down, and the whole city rejoiced when someone finally decided to do something in that area. As such, it’s no wonder when one of the most beloved house museums in Milan decides to dedicate an exhibition to Ginori’s porcelains and their three hundred years of history.

The MuseumThe Poldi-Pezzoli is one of the many noble houses in Milan that were converted to open museums, and it hosts an impressive permanent collection from furniture to the armoury, from oriental objects to textiles, up to an incredible amount of over 300 paintings, including your casual Botticelli, a famed dame by the Pollaiolo, and a grand amount of stuff from Bernardino Luini that’s particularly close to my heart for my marginal involvement in the exhibition at Palazzo Reale in 2014.

Plus they have five goldfishes in the fountain inside the grand staircase and they never see the sun and I’m pretty sure they hate everybody.The Exhibition: from Carlo Ginori to Gio Ponti

Plus they have five goldfishes in the fountain inside the grand staircase and they never see the sun and I’m pretty sure they hate everybody.The Exhibition: from Carlo Ginori to Gio PontiThe exhibition focuses on the factory in Doccia, founded by the Marquis Carlo Ginori in 1737 in Doccia, a town a few kilometres from the ancient village of Sesto Fiorentino, where the Marquis bought a villa in extension to his family’s estate. The factory started operating in July 1737, overseen by one Francesco Leonelli borrowed from Rome.

The first porcelains were highly experimental and came from the maquis’ knowledge of alchemical and chemical texts, his expertise as a chemist and his close friendship with people like Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti, one of the most famous botanists of his time.

As a result of tireless research into porcelain, the Marquis himself wrote a booklet entitled Theory of the Ingredients Suitable for Making Porcelain, noting down his experiences and experiments in the factory, alongside very personal entries on his expectations from the factory, his anxieties, and the criticisms of contemporary chemical and alchemical texts.

The initial experiments concerned mostly majolica, but on 6 July 1739, we have the first documentation of the attempt to make porcelain. The material will become mainstream in the factory thanks to the contribution of Joannon de Saint Laurent, a specialist from Lorraine, who collaborated with Carlo first and his son Lorenzo later.

The first porcelains made in Doccia are from around 1740 and they are painted cups decorated by the chief decorator of the manufactory, Johann Carl Wendelin Anreiter von Zirnfeld. He himself took them to Vienna, and donated them to the future Grand Duke of Tuscany Francesco Stefano di Lorena. With this homage, Carlo Ginori was hoping to obtain from the Grand Duke a privative for porcelain production in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, which eventually took place on March 3rd, 1741.

The factory distinguished itself on the European scene for producing large porcelain copies of antique sculpture and for porcelain translations of bronzes by late Baroque sculptors active in Florence, and the Grand Tour travellers went crazy about them.

Some of these masterpieces are exhibited in the first room, large pieces primarily intended for console table decorations and dessert table settings.

Aside from a personally unimpressive Venus, the first two groups that will catch your attention are the Atlas Holding the Globe from the galleries of Palazzo Madama in Turin, compared to the Hercules Holding the World by Ferdinando Tacca, from the collections of the Princes of Liechtenstein, and the porcelain Dancing Maenad compared with the bronze Amphitrite from the Studiolo of Francesco I de’ Medici. These two groups are a testament to how the Ginori porcelains weren’t simple copies, but reinterpretations of classical pieces that often changed the subject: Amphitrite, the goddess of the seas and wife of Poseidon, becomes a dancing follower of of Dionysus, the goddess’ shell and coral become a tambourine.

Amongst these classical reenactments, we couldn’t miss a reproduction of the Laocoön group, both in bronze and porcelain. As you might remember from the room dedicated to the subject in the recent exhibition dedicated to El Greco, the discovery of this statue had a tremendous impact on the imagination of the contemporaries, and it’s no wonder that the artists and engineers at the Ginori factory decide to reproduce it faithfully, without reinterpretations or without taking too many artistical liberties.

As the video upstairs will explain to you, the porcelain work is a veritable masterpiece in engineering, with concealed lodging for supports meant to prevent parts from falling before the porcelain was cooked and invisible mendings where pieces had to be assembled.

The second room (yeah, the exhibition only consists of two rooms, and I confess I was a little disappointed by its size), is dedicated to contaminations: the production moves away from classicism and explores other frontiers. To symbolise this period, the exposition proposes some large vases made for international exhibitions and the fabulous table service in neo-Egyptian style commissioned by the Khedivé of Egypt Ismail Pasha and created around 1872 on designs by Gaetano Lodi, which doesn’t renounce to Japanism and Michelangelo’s references.

Go Ponti’s Art DirectionIn 1896, the factory expanded and merged, becoming the Società Ceramica Richard Ginori with headquarters in Milan, which added the factory in San Cristoforo sul Naviglio to the Factory in Doccia. Gio Ponti became artistic director in 1923, and stayed on for ten years. During these years, design sprang forward into modernity by taking a humorous twist influenced by avant-gardes and metaphysics.

Some of the items he designed are still part of the current collection, now under the broad hat of Gucci: false architectural perspectives of a vase remind us of De Chirico, while decorative objects such as the tiny book of cartomancy wink to other masters like Fornasetti. The carnival is often present, as you can see in the Harlequinesque decoration of items such as the tortoise and the couple of elephants,

His works on display include two exceptional Ciste made especially for Fernanda and Ugo Ojetti, now owned by the Poldi Pezzoli Museum. The inspiring works won the Grand Prix at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, and they are the perfect summary of classical and modern, sumptuous and irreverent as it will be typical of Gio Ponti’s artistical direction.

A 2020 book, much more comprehensive than what exposed at the Poldi Pezzoli these days, provides a more comprehensive overview of the ceramics Ponti designed during his tenure: not only he contributed to modernising Richard Ginori’s production, bringing to a conservative creative environment like Florence’s a great variety of new shapes and motifs, but he allowed the pieces for playful contaminations drawing from a repertoire influenced through his travels, his reading, his interest in Greek and Roman archaeology or contemporary art.

Already a founder and director of the famed magazine Domus, he was involved in all aspects of the factory’s life, starting from communication: he assumed the role of an ante litteram press office and cultivated relationships with journalists and critics.

He was also concerned with product pricing. During the development of the modernist Inkwell with Coloured Architectures in 1925, for example, we have testimonies of his concern for the saleability of the object, and Ponti questioned that the price seemed very high compared to other pieces with richer and more complex decoration.

December 11, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 12: Nettle Bread

This recipe comes from Hannele Klemettilä‘s The Medieval Kitchen: A Social History with Recipes. She’s a Finnish historian and medievalist living in New York. Her recipe in turn is taken from Ulla Lehtonen’s Ullan luonnonyrtit : luonnon hyötykasvien keruu- ja käyttöopas (literally: Ulla’s natural herbs: a guide to collecting and using useful natural plants).

Are you out of bread and the guests are coming? We’ve got you covered, provided you’re up for a stroll in the woods.

Warm up the water and the mix yeast, caraway seeds and shredded nettle leaves with a pinch of salt. Once the leaves have been immersed in warm water, they usually lose their stinging ability, but I suggest you keep wearing gloves anyway should you have to handle them.

Mix the two kinds of flour separately and then add the mixture to the water, little by little, until it becomes a dough you have to knead with your hands.

Leave the dough to rise until it has doubled in size, then give it the shape you prefer and leave it to rise for another hour.

Before baking, Klemettilä recommends we pierce a hole in the side of the dough: it’s a Finnish and Swedish tradition meant for the hole to serve when you have to hang the cooked loaf to dry. Apparently, there’s such a thing called a breadpole.

Bake for 40-50 minutes in a 180°C oven.

Picture of a breadpole taken from this website.Nettles

Picture of a breadpole taken from this website.NettlesI wrote about the significance of caraway when we talked about the Tudor Lovers’ Knots, so here’s an excursus on the other crucial ingredient of this bread: nettles.

In the Middle Ages, nettles were a medicinal herb as they’re rich in proteins (for being a plant, that is), sulphur, calcium, iron and potassium. They have hemostatic properties, a poultice from their leaves was applied to wounds, and their roots, boiled with milk, were commonly used to cure kidney stones.

Walahfrid Strabo, an Alemannic Benedictine monk and theological writer from 800 AD, didn’t like them at all.

But this little patch which lies facing east

In the small open courtyard before my door

Was full of nettles! All over

My small piece of land they grew, their barbs

Tipped with a spear of tingling poison.

What should I do? So thick were the ranks

That grew from the tangle of roots below,

They were like the green hurdles a stableman skillfully

Weaves of pliant osiers when the horses hooves

Rot in the standing puddles and go soft as fungus.

So I put it off no longer. I set to with my mattock

And dug up the sluggish ground. From their embraces

I tore those nettles though they grew and grew again.

Catullus himself was very well aware of their properties against a cough and a cold, as he writes in his 44th poetic composition:

At this point, a chilling illness and persistent cough

shook me continually, until I fled to your embrace,

and I restored myself both by leisure and nettle.

Plinius has weirder ideas: he writes that a poultice of nettles can relax the uterus (so far so good), and that rubbing fresh leaves against an animal’s genitals might encourage them to mate. I highly discourage you from trying that.

It might be because of that (but I really hope it isn’t) that the seeds were considered an aphrodisiac throughout Germany and Italy. Castore Durante, in his Renaissance New Erbarium, tells us that:

Nettle branches, boiled in wine and drank… excite Venus.

A more romantic connection between nettles and love might be through a particular kind of butterfly, the aglais urticae or, in Italian, Vanessa dell’Ortica: they only live on these plants, and they’re absolutely beautiful. In English you call them Tortoiseshells, thus losing the connection entirely.

According to Alfredo Cattabiani, they’re a plant connected to the Sun: both in Pedimont and in Novgorod, Russia, kids either carried nettles or jumped on them during the Eve of Saint John, Summer Solstice. As many plants connected to the sun, it’s also considered a plant to fend off thunders: in Tirolo, it’s thrown into the fireplace as it’s believed that fields of nettles are never struck by lightning. And, of course, where there are thunders, there are witches: they were considered the cause of thunderstorms, and people in Pedimont used to create bundles of these plants to keep them away from the house.

In the fairy tale “The Wild Swans” by Hans Christian Andersen, the heroine’s brothers have been turned into swans by their evil stepmother and, in order to save them, she must gather nettles in a graveyard by night, spin them into a green yarn with her bare fingers, and then knit the yarn into seven coats, one for each swan. She must do so without uttering a word, or else the spell will become unbreakable. Yes, Andersen had a thing for women who are magically compelled to silence.

The Myth & Moor website dedicates a wonderful article to this tale and to the significance of nettles in folklore. It also features a family recipe for Bumblehill Nettle Soup.

”The Wild Swans: Picking Nettles by Moonlight” by Nadezhda Illarionova

”The Wild Swans: Picking Nettles by Moonlight” by Nadezhda Illarionova