Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 43

December 4, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 5: Mistress Duffield’s Capon in Orange Sauce

This one has the meat, I promise you.

Source:But will it have oranges?

The recipe comes from a book called The good Huswifes Handmaide for the Kitchin, (you have to read this like the Swedish Chef from the Muppets). The book is dated 1594 and written by one Thomas Dawson. Who’s Mistress Duffield? We don’t fucking know.

Frontispiece from the 1610 editionIngredients (4 people):A small skinned capon weighing around 1.5 kg chopped to 8 pieces, or the same amount of either fowl or chicken;a marrow bone;a pinch of salt;a cup of flour;a curl of butter;a glass of red wine;three oranges or half a cup of orange juice (the least sweet the better);a teaspoon of dried orange peel;a pinch of ground mace or nutmeg;a pinch of ground rosemary;a pinch of cinnamon;a pinch of ground ginger;a teaspoon of sugar;a cup of pitted prunes;a cup of currants;orange slices to garnish;verjuice, vinegar or balsamic vinegar.

Frontispiece from the 1610 editionIngredients (4 people):A small skinned capon weighing around 1.5 kg chopped to 8 pieces, or the same amount of either fowl or chicken;a marrow bone;a pinch of salt;a cup of flour;a curl of butter;a glass of red wine;three oranges or half a cup of orange juice (the least sweet the better);a teaspoon of dried orange peel;a pinch of ground mace or nutmeg;a pinch of ground rosemary;a pinch of cinnamon;a pinch of ground ginger;a teaspoon of sugar;a cup of pitted prunes;a cup of currants;orange slices to garnish;verjuice, vinegar or balsamic vinegar.The dosage is taken and adapted from this website.

Recipe:Sprinkle the capon with salt and boil it with the marrow bone, take away the meat when it’s almost done, but refrain from eating it: you’ll need it.

Take the broth away from the fire and preferably transfer it from a metal pan to an earthenware one. Drop currants and prunes, the nutmeg, and the rosemary (though some scholars argue that it’s not rosemary but more marrow). Add a glass of wine: the original recipe mentions claret, which means Bordeaux will do just fine. Put everything back on the fire and let it simmer for a while.

Squeeze the juice out of the oranges and pour it into the simmering broth (or pour the pre-prepared juice, you lazy ass). In the land of fairytales, you’ll be able to slice these same oranges and use them for garnish, but of course, they’ll be wrecked: you’ll need to slice up more neatly a new one when the time comes.

What you’ll have to do with these oranges, however, is put them in boiling water and let them go, and repeatedly change the water until the water is not bitter anymore. Yes you have to taste it. Please wait until it’s cold enough.

When the water has taken the bitterness away from the oranges, you can throw them in the broth with everything else.

After you’ve added the oranges, put the capon back into the broth and finish cooking it. Eventually, you’ll want to remove the capon and keep the broth going until it shrinks down to stock. When it’s dense enough, add the cinnamon, ginger and a pinch of sugar, stir and use a spoonful of the mixture as a basis for the dish. Lay upon it the pieces of capon, 2 for each plate, garnish with orange slices, some rosemary leaves and a drop of verjuice or balsamic vinegar.

David Rijckaert (1586–1642), Still life with a lemon and caponOriginal Recipe

David Rijckaert (1586–1642), Still life with a lemon and caponOriginal RecipeSince the recipe is written in old English and some passages are subject to interpretation, I also give you the original one:

‘To boil a Capon with Oranges after Mistress Duffelds way. Take a capon and boil it with veal, or with a marrow bone, or whatever your fancy is. Then take a good quantity of the broth, and put it in an earthenware pot by itself. Add thereto a good handful of currants, and as many prunes, and a few whole maces, and some marie. Add to this broth a good quantity of white wine or of Claret, and so let them seethe softly together. Then take your oranges, and with a knife scrape of all the filthiness off the outside of them. Then cut them in the middle, and wring out the juice of three or four of them. Put the juice into your broth with the rest of your stuff. Then slice your oranges thinly, and have ready upon the fire a skillet of fair seething water, and put your sliced oranges into the water. When that water is bitter, have more ready, and so change them still as long as you can find the great bitterness in the water, which will be six or seven times, or more, if you find need. Then take them from the water, and let that run clean from them. Then put close oranges into your pot with your broth, and so let them stew together till your capon is ready. Then make your sops with this broth, and cast on a little cinnamon, ginger, and sugar, and upon this lay your capon, and some of your oranges upon it, and some of your marie, and toward the end of the boiling of your broth, put in a little verjuice, if you think best.’

Picture stolen from here in case you want to try one of their recipe instead.What’s with the capon and Christmas?

Picture stolen from here in case you want to try one of their recipe instead.What’s with the capon and Christmas?Well, that’s a good question.

As Alison Weirs reminds us in her Tudor Christmas book, capon is only one of the “rich meats” traditionally served for Christmas, and its mention in this XVI Century anonymous poem is spot on:

Then comes in the second course with mickle [much] pride,

The cranes, the herons, the bitterns, by their side

To partridges and the plovers, the woodcocks, and the snipe.

Furmity for pottage, with venison fine,

And the umbles [entrails] of the doe and all that ever comes in,

Capons well baked, with the pieces of the roe,

Raisins of currants, with other spices mo[re].

Capon was also an ingredient to create and serve fantastical animals: the ‘cockatrice’ wasn’t uncommon, and it comprised of the roasted forequarters of a pig with the hindquarters of a capon itself, often adorned with other birds’ plumage, gold leaf for beak and coloured beads for eyes.

Art by Pikart.

Art by Pikart.

December 3, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 4: Plum Porridge

This is a throwback from last year’s December, 4th: that one was for patrons only, this one is published for everybody.

Plum Porridge, is described by Alison Weir as «a thick broth from mutton or beef, boiled in a skin with plums, spices, dried fruits, breadcrumbs and wine». Flour was added in late XVI Century, to turn the porridge into a pudding, and Victorian times removed the meat to turn the dish into what we now know as today’s plum pudding, usually served as a dessert. A derivative of this dish is also the New College Pudding, already mentioned when we saw “The Witches Frolic”.

The original Victorian recipe of that one can be found in Elizabeth Moxon’s English Housewifry (1764) and goes like this:

Grate an old penny loaf, put to it a like quantity of suet shred, a nutmeg grated, a little salt and some currans, then beat some eggs in a little sack and sugar, mix all together, and knead it as stiff as for manchet, and make it up in the form and size of a turkey’s egg, but a little flatter; take a pound of butter, put it in a dish or stew-pan, and set it over a clear fire in a chafing-dish, and rub your butter about the dish till it is melted, then put your puddings in, and cover the dish, but often turn your puddings till they are brown alike, and when they are enough grate some sugar over them, and serve them up hot.

For a side-dish you must let the paste lie for a quarter of an hour before you make up your puddings.

So, let us try and make some sense of it. As usual, and as you might have noticed, there are no plums in the Victorian recipe.

What is suet?As this site explains us, suet is rendered fat, typically coming from cow: it’s raw fat dehydrated through heat. You have a “recipe” here.

It comes in solid form, so you have to grate it and it’s highly recommended you use flour before you do.

If the doses seem a little off to you, they seem a little off to me too: just try it and let me know. I can’t cook for shit.

December 2, 2023

50th Anniversary’s Rocky Horror Show

On Friday evening, we went to see a Rocky Horror Show rendition put together for the 50th Anniversary of the show, and currently touring Europe. I don’t even know how many times we’ve seen this anymore: every time a new group comes to town, we try and grab a ticket. We missed them last year, so we couldn’t miss this one.

What are you blabbering about?I know that the world is divided into two people (and a half): those who are hardcore fans of the Rocky Horror Show and can carry on the joint performance throughout the whole show, and those who have no fucking idea of whatever the hell you’re going on about (more about the “and a half” later). So, just in case you’re from the third group, here’s a brief overview of the show’s meaning and significance.

The Rocky Horror Show is a theatre musical entirely written by Richard O’Brien, a New Zealand polyhedric artist, back in 1973. A pioneer in challenging the way we approach gender and one of the first to define himself neither male nor female, but possibly transgender or of a third gender, O’Brien whipped together a tribute to science fiction and horror B movies in which the innocent and unsophisticated newly-engaged Brad and Janet are caught in a storm and find themselves seeking shelter at the eccentric house of the weird and eccentric Frank-N-Furter, a creature who defines himself “a sweet transvestite from Transexual Transylvania”. We soon learn that Frank and his plethora of equally eccentric companions are engaged in some sketchy stuff, as Frank brings to life a Frankensteinian creature called Rocky, “with blonde hair and a tan”, whom he clearly wants to employ as a sexual fetish, and a previous lover springs open from the refrigerator where he was kept for pieces.

As the story progresses, both Brad and Janet are seduced by Frank, and Janet eventually hooks up with Rocky, we discover that Frank and his companions are in fact coming from another planet, called Transexual, in the galaxy of Transylvania. After managing to bring them all around to his disinhibited values through a mix of mind control and cross-dressing, Frank is ultimately killed by his servants before they leave for their home world. Brad and Janet are left on earth to deal with the downfall of their encounter.

“Glam rock allowed me to be myself more.”

– Richard O’Brian

Australian director Jim Sharman was the first one wishing to give a go to this weird and daring piece: at the small experimental space called Upstairs in the Royal Court Theatre building in Sloane Square, the show was put on stage with Tim Curry in the original role of sensual, unapologetic and seductive Frank.

And if you don’t find this sexy as hell, go see a specialist.

And if you don’t find this sexy as hell, go see a specialist.The show was turned into a movie two years ago, starring Tim Curry as the lead role and featuring Susan Sarandon as Janet. Meat Loaf guest-starred as Eddie, Frank’s former lover who gets killed on stage.

The impact of both the movie and the show was enormous: if you want to know more, you can watch the 2016 documentary Rocky Horror Saved My Life, involving fans, collectors, and people who were impacted by the production, particularly queer people struggling with their identity.

What’s the third half?Oh, you haven’t forgotten. I didn’t say “the world is divided into three halves”, though. I said: “the world is divided into two groups and a half.” I didn’t know about the other half until recently, possibly because I’m old and I can’t stand the ticky-tocky place, but apparently there’s a big group of people voicing how The Rocky Horror Show is problematic for transgender representation. The main point raised is, as you can read in this article, that Frank falls into the predatory, murderous misrepresentation of queer people. There’s also a point regarding transgender actors not being cast to play Frank, which is weird because he’s not transgender: he’s cross-dressing. We should know there’s a difference, by now.

Anyway, be mindful that you also have that.

The 50th Anniversary ShowDirected by Christopher Luscombe, this version of the show stars Stephen Webb as Frank and features an elaborate choreography (courtesy of Nathan M Wright) with many original additions throughout the classic numbers.

The scenery is a ribbon of celluloid wrapping around the upper part of the stage. From there, you have vintage movie curtains, starry satin frocks, gothic sceneries and science-fiction labs, solid and fabric stage drops framing characters engulfed in an array of lights that span from the cold, medical whiteness of the lab to the sidereal one of the ending.

Webb as Frank is magnetic, and his charisma is undeniable, though his voice wasn’t always coming through the music to where we were sitting. Riff-Raff, Frank’s Igoresque servant, is played by Kristian Lavercombe, but I’m afraid Stuart Matthew Price has ruined any other Riff Raff’s chances with his stunning 2015 performance. The real surprise was Haley Flaherty‘s Janet: in a role that’s usually reserved for actresses with good exposition and no more than decent singing (Sarandon included), she gave us a powerful performance with some serious display of lungs, especially in her duet with Rocky where she sang swinging, dangling upside down, jumping and dancing.

A word of mention also goes to Darcy Finden‘s Columbia, an actress with great moves and comic flair who’s clearly not singing within her register, and whose voice you’ll appreciate when she’ll give you a taste of her lower notes and warmer colours during the “Floor Show”.

Last but not least, the public is always an active part of the show, interacting with remarks, call-outs, shout-outs and sounds. And boy, did we have some hardcore people in the audience last night (including a spectacular middle-aged guy who was sporting the upper part of a man’s suit with a jacket and white shirt, and was in black thongs with suspenders and veiled stockings on the lower part). While certain actors decided to mostly ignore the audience and carry on with their performance, Webb included, Alex Morgan’s narrator had it the toughest, with constant interactions he carried on with grace, charm, and a not-so-bad dose of Italian.

See you next time!

[image error]Rocky Horror Show 2022 – Stephen Webb as Frank N Furter, Haley Flaherty as Janet, Richard Meek as Brad, Suzie McAdam as Magenta, Kristian Lavercombe as Riff Raff, Darcy Finden as Columbia, Joe Allen, Reece Budin, Fionán O’Carroll, Stefania Du Toit and Jessica Sole as The Phantoms#AdventCalendar Day 3: Bisket Bread

The recipe is taken from Thomas Dawson’s The Good Huswifes Jewell (1596), and it’s for a variety of long-lasting bread that was usually not particularly tasty, and it’s called this way because it’s cooked twice, like a biscuit. Alternative versions and an amended, modern one are available on this page.

Ingredients:450 grams of flour;450 grams of sugar;8 large eggs;musk (can be replaced with 8 anise seeds);aromatic seeds of your choice;half a pint of damask water (can be replaced with rosewater);a glass of sweet red wine (for some reason, the authors of The Tudor Cookbook recommend Muscadine, a native grape to North Carolina, which is a bit… counterintuitive, being this a medieval recipe).Recipe:Beat the eggs, whites and yolks and everything, and mix them with a pinch of flour; then add the mixture to the rest of the flour.

Ground the musk (of the anise seeds if you want to carry on living), add the damask water (or rosewater), mix it and add the wine. Stir the mixture and add it to the flour alongside aromatic seeds of your choice that will remain whole in the bread. If you like it. If you don’t like it, don’t do it. Work the dough until you’re satisfied with the consistency, fashion it into a loaf. When you cook it in the oven, make sure you don’t overcook it if you value your teeth.

You can candy the surface too. Should you want to do that, take rosewater and sugar, boil them together until they turn thick and brush the syrup on the bread when it’s half-cooked.

Alternatives:If you prefer videos, you can take a look below.

Musk???Yes. Apparently it was customary to use musk in cooking, and I can only assume they meant literal musk. You can also find it in this Italian recipe for biscuits by Bartolomeo Scappi (1570). I have a friend who’s allergic to mould and I’m pretty sure these cookies would kill her.

Morandi 1890-1964

As a passionate geometry student since I was a kid, Morandi and De Chirico have always fascinated me, though I must admit they don’t always spark an emotional response in me. Palazzo Reale dedicates to the metaphysical Italian painter Giorgio Morandi a neat exhibition, curated by Maria Cristina Bandera. She’s Director of the Roberto Longhi Foundation for the Study of Art History in Florence, and if you don’t know her, I suggest you check out her books, such as her commentary on the book Roberto Longhi dedicated to Morandi himself.

The exhibition creates a connection between Bologna, where the artist lived and worked, and Milan as a centre of attraction where many of his collectors resided.

“We conceived this exhibition for Milan, the city that first, thanks to its enlightened collectors and its gallery of choice, understood the importance and originality of Morandi’s pictorial research”.

– M.C. Bandera

It’s a monumental selection: over 120 works running through the painter’s entire production, following a chronological order and running through 34 sections.

I won’t be talking about all of them (it would take me a lifetime, but here’s a selection of what I liked the most). From December, 2nd you can book a tour with the curator herself. The exhibition also has a wonderfully detailed website, with much more information than the official one.

“In Morandi’s paintings, so apparently simple, so rigorous, there is always a place, a point from which to spy the infinite, the infinite also of this poetry of his, so calm, so subdued.”

– B. Bertolucci

Morandi was fascinated by the avant-garde, and painted a set of works that are very far from the metaphysical style he will be known for. He destroyed many of them, and only 34 survived. The exhibition displays seven of them.

Although Morandi could never travel to Paris, he managed to get hold of the artistic innovations through books and magazines, from Cézanne to Picasso’s analytical cubism.

2. 1918-1919: Metaphysical InfluencesThe avant-garde experience melts with suggestions from Medieval and Renaissance art, from Giotto to Piero della Francesca, and the result is one of the first masterpieces in the marriage between two-dimensional space and delicate tones of Renaissance memory: the 1916 Still Life.

The metaphysical season of 1918 sees the presence of objects such as mannequins, T-squares and rules, geometric solids that, unlike de Chirico and Carrà, remain anchored in everyday life without denying their metaphysical essence, embroidered in the contrasts of chiaroscuro, in the absolute compositional rigour, in the polished painting with few colours and by cold and artificial light, albeit softened in soft tonalism.

The shitty political atmosphere influences the artist, who abandons metaphysics and returns to order. Still, he remains connected to the values expressed in the Valori Plastici magazine, created to disseminate the aesthetic ideas of metaphysical painting and European avant-garde currents. Morandi starts representing common objects stripped of all their perceived magic, and he concentrates on rendering their perspective, their materials, their plastic presence in the illuminated space.

Landscape, still life and flowers dominate the paintings of this period and let me be plain with you: Morandi’s flowers kick some serious asses. Their abstract nature on a golden background is a direct quote from the flowers Giotto’s angels are holding in his Maestà di Ognissanti.

We’ll see more flowers, further on, and I love them all.

5. 1928-1929: EngravingsMorandi is considered the greatest engraver of the century, and not only on the Italian scene. This section showcases his etching technique and the way his artistic language evolved during this year of intense experimentation, and the influence these works had on painting: Morandi reduces colour to two fundamental tones, conquering tonal painting with unparalleled mastery.

This room is one of the most interesting in the whole exhibition, with a set of engravings side by side, the original copper plate and the source painting.

Can you see the differences? Morandi himself helps us in writing to Lamberto Vitali, a photographer his friend:

In the 2nd state, there are some horizontal lines between the two bottles in the bottom, in the long box and in the lower inner part of the jug on the right. In the 3rd state, additional vertical lines are between the bottles, and horizontal lines are in the thickness of the plane on which the objects rest. In the 4th some vertical lines in the bottom between the two bottles. In the 5th some lines in the light of the triangular bottle on the left. In the 6th state […] I erased some lines in the upper inner part of the jug, added some and deepened others.

In the 1930s, the compositional solutions intuited in the previous decade veer into a new monumentality and an intense research into colour, with sometimes contrasting results: a rich chromatic paste or, on the contrary, a less consistent and thinner one.

Landscapes, present since the beginning of his production and still relevant after 20 years of career, alternates with still life in a sort of counterbalance.

“I am constantly working from real life… It’s true, I have done more still lifes than landscapes – and to say that I loved landscapes more but one had to travel and linger in one place or another and return to complete the work.”

The painter used to isolate the motifs of his “villages”, as he preferred to call them – Grizzana and Roffeno, in the Bolognese Apennines – using a telescope or a ‘little window’ made out of a piece of cardboard. From the window of his room-studio in Bologna, he framed the courtyard of Via Fondazza, which was both a vegetable garden and a decorative one.

“The most beautiful landscape in the world is here. It’s going up towards Grizzana. At a certain point there is a curve and there, when you come out of the curve, is the most beautiful landscape in the world. But what can you see? All badlands.”

We have landscapes dilated in a marked optical zoom that abolishes the sky and deprives the subject of focus, also filtered by a diaphanous light standing between Seurat and Piero della Francesca, which flattens the forms into inlays of geometric joints.

The still lives of these years are more crowded, with objects dilating in the background, frozen in a rigid frontal view. Colours saturate the canvas and absorb the shapes, the space and the shadows, undermining the recognisability of the objects themselves.

Five central sections of the exhibition showcase more than thirty works, representing a turning point in Morandi’s career: a new impulse of simplification leads him towards the style that will be typical of his more mature production.

The progressive transfiguration of what is real and what is perceived reaches its peak in the landscape he paints during the Second World War: more than eighty works.

The Apennine houses become solitary cubes, essential geometries in the grazing light and deep cones of shadow, almost as if they were simple parallelepipeds, in a clear assonance with what the painter used to do when arranging the objects in his still lifes. The painting maintains decisive thicknesses of material in broken and segmented outlines and in colours reduced to a few tones. His landscapes are willingly “unpicturesque”.

Alternatives to this drama are a couple of works from 1941 and 1942: the image is back into focus, accentuating a timeless dimension. This Landscape in Grizzana is definitely one of my favourites.

We also have still lives, in this period, and they’re an astonishing assortment of spiral and twisted objects, ceramics that seem to be vibrating with everyday usage, and those flowers I’m so fond of.

Shadows and their absence are also subjects of experimentation during this year: we span from paintings of absolute, diffused light to dramatic sceneries in which a spotlight seems to be aimed at the object and stark shadows are pained on a defined surface.

The theme of shells, inspired by Rembrandt’s etching Conus marmoreus, has been present since 1921 and is taken up again with intensity during the war: images of a fossilised world represent the most tormented side of painting in these years. The artist devoted himself to these still lives mostly on small canvases in monochrome colours.

I love each and every one of them, so you’re getting them all.

In this still life 1943, the expanded tips of the large fossil on the right contrast with the closed, leathery fist of the other shell. The painting follows a wandering line: the shell’s wispy white colour gives off a mysterious glow, the painting’s only apparent source of light, and a sharp line separates the resting plane from the background.

In another still life from the same year, the same fossil is reversed and magnified: we get more detail, this time, the chiaroscuro excavations emphasise its alien coils and protuberances, amplified by the juxtaposition with a familiar object such as the sugar bowl.

Lastly, three bare spindle-shaped shells are tightly packed together within an almond arrangement and seem to be unhatching, like from a cocoon, emerge from an enveloping chiaroscuro that accentuates their sense of isolation and loneliness.

It was 1940.

Everyone was lonely.

The painter abandons realism and goes back to those imperceptible geometric and perspectival deviations that recall youthful abstractions and a more playful style, before the 20s, before the war and before the fucking fascists destroyed the Country.

He works and reworks on variations of the same themes, and declares:

“I think I managed to avoid the danger of repeating myself because I devoted more time and attention to the conception of each of my paintings as a variation on one or another of a few themes.”

You’ll let me know how that makes sense.

He varied by changing the way objects are arranged, framed on different table tops, fighting the laws of gravity or floating without support lined with paper. The light source came in from the courtyard of his study, and was guarded by a system of veils affixed to the window. The canvases became smaller in format and the objects, grouped together in compact geometric structures, lost their verisimilitude.

The main characters of these paintings are a crumpled yellow cloth, the spiral-shaped bottle, the famous long-necked bottles, and an inverted funnel placed on top of a cylinder specially made by Morandi, which is none other than the oil container and would fascinate Aldo Rossi. The colours veer towards unreal timbres, with an everpresent contrast between soft-warm and cold tones.

These flowers in their vertically-striped vase have lost all realism: only the substance of their petals remain, and the cramped group isn’t impervious to a light that penetrates all, almost coming from within.

Also, can we talk about these frames?

Another example of flowers from the same period isn’t shy of shadows, and give us a long, thin stroke on the table with sharp brush strokes that help us identify peonies, roses, and a fucking tulip.

The geometry of the vase is less rigorous, almost distorted by the light washing from the left.

The same goes for another composition that seems to be merging the two: the vase geometry is distorted and the shadows are licking its body, whereas the previous one seemed to be immune, but the flowers are almost falling into its mouth like preys to a hungry mother, cramming together petals and leaves.

During the 50s, Morandi also comes back to landscape painting and in particular we see a new approach in representing the Courtyard of Via Fondazza: the layout is defined by a wall and a slope of roofs now reduced to pure essence in the accentuated discordance between the flat wall that acts as an apparent backdrop on the left side and the more articulated and perspective scenery of the volumes. Aside from the fact that I love his flowers, they’re probably among the finest things he painted.

The exhibition showcases them at the sides of an audio-video installation that’s supposed to be immersive and maybe taking us into the studio of the painter but, as far as I’m concerned, it failed to evoke any emotion.

Nine charming watercolours take us on a particularly dreamy journey, an intense period that sees over 250 sheets of watercolour being produced in the span of seven years.

“For me there is nothing more surreal and nothing more abstract than the real.”

Central to these still lives is another geometrical composition, an inverted funnel on a cylindrical box, in some cases coupled with a smaller version.

Watercolours are unusually illuminated from the right and bathed in an unreal violet palette that covers the objects with a ghostly appearance. The shadows are sharp and dark, the shapes are so dense with colours that they reach the threshold of abstraction. Compare for instance a painting…

…and its corresponding watercolour.

You cannot distinguish the objects anymore.

Morandi’s last season sees the untiring variation of motifs implemented through iterations of increasingly complex intuitions.

The progressive formal despoliation reaches a total simplification of the composition, based on just a few objects, sometimes compressed and superimposed to the point of becoming a single superobject.

We will never see sharp tones again: these are clearer and more varied, lacking in texture, soft and almost impalpable. The colour sublimates in a refined range, with combinations and detachments of layers that come to dematerialise in the light, bringing the canvases closer to watercolours.

“What is important is to touch the bottom, the essence of things”.

December 1, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 2: Capons in Dorre

The dish is also known as Capons in Dorre, and it features in MS Pepys’ Gentyll Manly Cokere (1490). You can read the original here, alongside some translations.

Grind blanched almonds, temper them up with clear water and stir until it starts to look like milk. Strain the mixture, place it in a pot and use enough saffron, add a pinch of salt and a spoonful of sugar, and put it on the stove. Keep stirring (you’ll be sorry if you don’t), bring it to a boil and add a spoonful of white wine. Remove the stuff from the fire.

Take some white bread, slice it into small strips and toast it on a hot plate until it turns a nice brown.

You know where you stand in this.

You know where you stand in this.Dip the bread into the rest of the white wine, and grill again. Then pour a little of the “milk” in bowls, drop 3 or 4 pieces of the grilled bread into each bowl and cover them with additional milk. Serve lukewarm.

Which wine?Again, even if it’s a soup, never use for cooking a wine that you wouldn’t use for drinking. Since this will be a warm dish, we need something with a little personality. I’ve seen recommendations to use Greco di Tufo, a wine that doesn’t mess around and is mostly produced in the Southern part of Italy, around Avellino.

Where is the capon?Good question. There’s no capon in this recipe, it’s 100% meatless, either the author is shitting you or some scribe made a clerical error by carrying capons over from previous recipes. It’s basically a bread soup with almonds, saffron and wine.

It will look a bit like this, and I stole the picture from here (in case you’re looking for a soup with actual milk).

It will look a bit like this, and I stole the picture from here (in case you’re looking for a soup with actual milk).

#AdventCalendar Day 1: Spit-Roasted Eel

December starts on a Friday this year, and Friday used to mean fish, so let’s stick with tradition. It always amazes me how many people haven’t tasted eel, which is traditional in my part of Italy, but let’s not be like cooking blogs, so… recipe first.

Picture stolen from here: they have a wonderful recipe for eel preserved in vinegar.Spit-roasted EelIngredients (serves 4 people)800 grams of eel200 grams of finely grated bread mixed with crumbs2 tablespoons of white flour2 glasses of white wine (never cook with anything you wouldn’t drink: the sommelier recommends a glass of Soave wine)a bunch of bay leavesa bunch of sage leavesground cinnamonolive oilsaltYou’ll also need:toothpicksskewerseither an novel or an open flame (the fireplace is fine, if you don’t mind having to clean it afterwards)Recipe:

Picture stolen from here: they have a wonderful recipe for eel preserved in vinegar.Spit-roasted EelIngredients (serves 4 people)800 grams of eel200 grams of finely grated bread mixed with crumbs2 tablespoons of white flour2 glasses of white wine (never cook with anything you wouldn’t drink: the sommelier recommends a glass of Soave wine)a bunch of bay leavesa bunch of sage leavesground cinnamonolive oilsaltYou’ll also need:toothpicksskewerseither an novel or an open flame (the fireplace is fine, if you don’t mind having to clean it afterwards)Recipe:Chop the eel to pieces 4-6 cm long, sprinkle them with salt and wrap them alternatively one bay leaf or one sage leaf around each piece (don’t worry if you won’t be able to wrap all the eel in it: the flavour will spread anyway). You’ll need toothpicks to fix the leaves in place, and you’ll have to be careful not to set them on fire later on.

Skewer the pieces and roast them on the flame (if you want to live a dangerous life and you have a traditional kitchen that kicks some serious asses). If you’re a normal person, however, you might want to pre-heat the oven and suspend the skewer onto a baking pan. You’ll have to open the oven multiple times and turn the skewer. Each time you do that, water the eel with a tipple of white wine. When you see the eel is turning golden-brownish and crispy, it means it’s almost done: brush the pieces with oil, sprinkle them with the flour and thoroughly cover each pieces with grated bread and crumbs to create a crust. Cook a few more minutes.

When all is said and done, place the pieces on a serving platter and sprinkle them with the ground cinnamon.

About the wineSoave is a dry white wine produced in the northeast, around Verona. Its name seems to come from the Svevians (Suaves), who came down to Italy led by their king Alboino around 568 AD and renamed the area. Wine was already produced in the zone, though: Cassiodoro writes about it and says its colour is so pure that you’d think it’s made from fleur-de-lis(es).

About eelsAs I was saying, eels are a typical dish around my area, but they’re not so common in other parts of Italy. They were highly trendy in the Middle Ages, and if you don’t believe me, you need to follow the Surprised Eel Historian on Xitter and/or in the Blue Place.

November 30, 2023

#AdventCalendar: Medieval food

As many of you know, the novel I’m working on has flashbacks from Tudor times, and some characters come from that Era. I have a ton of notes of stuff which didn’t make it into the book and it’s customary for me to do a daily post throughout December, leading up to Christmas, so this year I thought I’d be naughty and give you a recipe a day. A couple of them will be a throwback from last year, but most of them are taken from three main sources:

Alison Weir and Siobhan Clarke’s A Tudor Christmas;Terry Breverton‘s The Tudor Cookbook: From Gilded Peacock to Calves Feet Pie;Brigitte Webster‘s Eating with the Tudors: Food and Recipes;Peter C.D. Brears‘ Tudor Cookery: Recipes and History;an Italian book on medieval cooking.Though I can’t guarantee consistency, I’ll try to balance recipes with stories and references, and make sure you have a whole menu should you wish to go medieval on your family’s ass this Christmas. Stuff will be published here and on the Patreon.

The only stuff I can cook comes from that book.

The only stuff I can cook comes from that book.

November 29, 2023

On (in)sensitive writing

I’ve been sharing with you my writing journey for a while now, either here, on the Blog or on my social platforms (mostly The App Formerly Known as Twitter), and one of the most recent developments is that I’ve closed deals with different readers to get a look at my most developed draft. Specifically, one of them was to look at how I treated gender issues, one of them was to give me feedback on characters of colour, and another group had a more general overviewing task. I had employed an editor before, back when the draft was in Italian, and I hadn’t been completely satisfied with their work: this time, I must say that the given feedback had much more value so far, and I have more than a few points I know I want to address for the 5th and final draft of the book. Then, I will start querying.

Meanwhile I have a working title, but that’s not the point right now.

What seriously surprised me was the amount of hate I got online, mostly through unsolicited private rants, because of my decision to employ sensitivity readers.

I thought we were past that.

I thought most reasonable people had reached an understanding of why it matters to write inclusive stories and, most importantly, how to approach the representation of characters that diverge from you and your experience. This only proves how much we tend to live in bubbles… which is a self-sustaining argument when it comes to sensitivity reading, but I’ll get to that in a moment.

So let us try to unpack a few things:

my approach: what is it that I’m writing, and why I felt I needed a sensitivity reader;what the heck is a sensitivity reader anyway, and what can you expect from them as an author;what’s the controversy here (and why I think it’s dangerous). It’s going to be a bumpy ride, so take a look at some bears before we start.1. I’m writing historical fiction

It’s going to be a bumpy ride, so take a look at some bears before we start.1. I’m writing historical fictionEmphasis on fiction.

My work has witches, shapeshifters, at least a guy who might or might not be a dragon, all wrapped up in a concept we might call liminal magic. It’s not a historical treaty, it’s not written in XVIII Century English and I’m sure, regardless of how much I tried, that I have a couple of anachronistic terms and concepts being used in there.

Besides, my main character swears a lot.

Accuracy only matters to me up to a certain point: I don’t want to burden the reader with incomprehensible prose, but I do want to convey the sense that some characters might be more down-to-earth than others, for instance, so the occasional anachronistic term conveys more meaning than being accurate. I assume the reader understands that we’re in 1702 after seeing it written at the beginning of each fucking chapter.

This of course begs the question: if being accurate doesn’t matter so much, why did I employ consultants?

Sometimes, I did it because I was stuck and needed ideas. I knew the ship in my story had to make a stop in Madeira, for instance, but I didn’t know how to go about it, so I consulted with an expert on Portuguese folklore and they un-stucked me.

I even took a trip there, do you remember?

I even took a trip there, do you remember?Other times, I needed a head-start: I wanted some characters to come from a specific background, and I felt I knew too little of their culture, so I consulted with local experts and I think my characters are all the better for it.

1.1. How is this different?While a person working as a sensitivity reader might also contract as a consultant, sensitivity reading steps into the picture after you wrote your thing: you basically give your draft to a consultant, ask them to read it, and require that they focus on specific areas, giving you a particular kind of feedback.

What areas?

That’s the point.

Sensitivity readers usually work on areas that are akin to their personal expertise: they might be people from marginalized cultures taking a look at how diversity is treated and represented in a work of fiction, neurodivergent people aiming to provide you with insights on how neurodivergence is experienced, people with disabilities looking for involuntary slurs, people with a different approach to gender and sexuality, and so on.

There’s an excellent introductory overview over here.

Antoine Wiertz (1806–1865), The Reader of Novels (1853)1.2. Are they spokespersons of their area?

Antoine Wiertz (1806–1865), The Reader of Novels (1853)1.2. Are they spokespersons of their area?Of course they are not. There’s no such thing. Being from a culture of having a particular experience doesn’t entitle you to speak for everyone from that culture or everyone with that experience. Just as much as being queer or neurodivergent doesn’t make you the spokesperson for every single queer and neurodivergent person out there. That’s not the point of a sensitivity reader: you’re not consulting an oracle, for fuck’s sake.

I might be Italian (which I am), I might read a work of fiction depicting Italians, and I might point out stuff that sounds offensive or misrepresentation to me, but:

I won’t speak for all Italians, I can’t, I don’t have the right to.

This becomes even broader when we’re looking at people of colour or LGBT+ characters: they’re such vast communities that no one can be elected to speak for all of them. You can only ask an opinion from a limited number of them.

So what’s the point?

People in the upper tier will be able to read my views on the Patreon. It gets published at 10:00 am CEST today.

November 28, 2023

Rodin and dance

Let me start with one simple but fundamental assumption: I hate Rodin. Not artistically, of course, but I think he was a sick piece of shit and a bastard through and through, who used women, abused Camille Claudel both emotionally and artistically, stole her stuff, and up to these days we still say she “died of consumption” after “falling into paranoia”.

Paranoia my ass.

Anyway.

The exhibition is hosted at the MUDEC, Milan’s Museum of Cultures, and springs from a collaboration with Musée Rodin in Paris, which lent 52 pieces. Don’t expect the usual exhibition, though: the project unfolds across three sections and they’re respectively curated by Aude Chevalier, Assistant Curator of the sculpture department at Musée Rodin itself, Cristiana Natali, Professor of South Asian Anthropology, Anthropology of Dance and Ethnographic Research Methodologies at the University of Bologna, and Elena Cervellati, Associate Professor of History of Dance and Dance Theories and Practices at the Department of Arts of the University of Bologna.

Rodin and Dance: a timelineThe exhibition also becomes an opportunity to take an extraordinary journey into the world of dance through a video selection referring to contemporary choreography and choreographers, who were inspired by Rodin for their performances. The continuous dialogue between Rodin’s sculptures and the multimedia and digital system, together with the immersive installation create a constant play of visual and symbolic cross-references.

At the beginning of the XX Century, Paris was at the centre of the artistic avant-garde, and this included painting, sculpture but also acting and dancing. Mobility was facilitated by the expansion of railroads, and sea transports were becoming safer, or at least less distressing, so people would come to Paris searching for fortune and they would cross their path with touring artists. Though Wolfgang A Mozart was possibly the first one to go on tour when he was a child, and even if historians attribute to Franz Liszt the first idea of concert tours, it’s undeniable that the phenomenon boomed at the beginning of 1900.

Rodin’s studio was a well-known meeting place for intellectual and artistic circles, and this included visiting dancers. The exhibition opens with a timeline, on the usual curved glass walls in the museum’s foyer, the lower part of which focuses on Rodin himself and with an upper part concentrating on the history of dance.

http://www.shelidon.it/splinder/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/20231127_145812.mp4

Rodin and dancers“In our art, the illusion of life is achieved by good modelling and movement.”

– Rodin to Paul Gsell (1911)

Rodin was attracted to both avant-garde shows, especially the ones in which the dancer was female and nude, but he showed as much interest in classical ballets as in French or foreign folk dances. The first room starts with a selection of these dancers.

Loïe Fuller (1862 – 1928)American, a pioneer of modern dance and theatrical lighting techniques, she had debuted as a toddler in Chicago, performing in dance roles just as much as dramatic performances. She exhibited in groundbreaking free dance shows, alongside Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, and developed her own movements breaking free from the figures of traditional classical dance. Her improvisation techniques involved experimenting with garments such as a long skirt or a shawl, which served as a choreography prompt and which the dancer used to play with the ways it could reflect light. These experiments led to her invention of the Serpentine Dance, in 1891, a free dance show with silk costumes illuminated by multi-coloured lighting she designed herself. This dance fascinated early filmmakers: both the Lumière brothers and Méliès filmed short takes of dancers twirling their coloured skirts.

Rodin saw her performing at the Follies Bergère between 1892 and 1893, but the two artists met in person in the summer of 1898, through their mutual friend Roger Marx, a cultural critic and fierce supporter of both. According to sources close to Rodin, it was Fuller who actively sought out the sculpture and asked to model for him. Other sources indicate that both artists admired each other’s creations and wanted to establish a connection.

In any case, Rodin was open to the idea of creating a statue based on Fuller’s movements and arts, but the dancer was either too busy or on the move and, though she expressed interest in having the statue done by the Exposition Universelle in 1900 in Paris, where she was giving performances, Rodin never undertook the work.

Fuller eventually established herself in a theatre of her own, and remained friends with the sculptor: she introduced him to other dancers such as Japanese dancer Sada Yacco, who practised a Kabuki-inspired dance style and was so tremendously popular in France that, upon returning to Japan, the local government allowed her to be the first woman to perform a dance on stage since the practice had been outlawed.

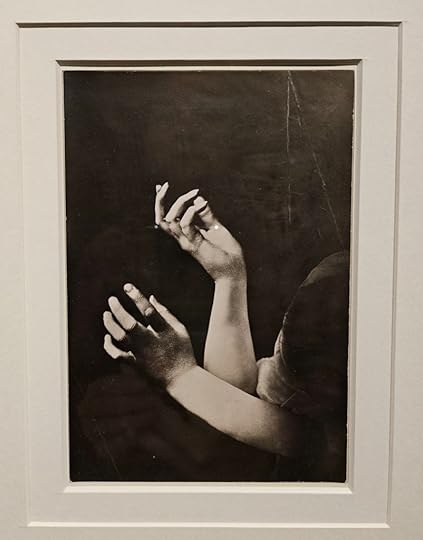

Though Fuller could rarely see Rodin due to his peculiar romantic choices, it’s speculated that he inspired her “The Dance of Hands”, which debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1908. We know for a fact that he gifted her a moulding of his hands sculpture.

This contemporary photograph of Fullers hands is preserved at the Rodin museum and displayed in room 1.

This contemporary photograph of Fullers hands is preserved at the Rodin museum and displayed in room 1.Ruth Saint-Denis (1879 – 1968)“The soul expresses itself through each and every part of the human form. A hand separated from the body can express its joy, its sorrow, its grief, with as great perfection as the complete form of man.”

Another American pioneer of modern dance, she’s mostly known for Eastern inspirations and her interest in dance as a mystic form of expression. In 1915, she founded the American Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts.

Rodin depicted her in a sketch, or, at least, he represented her uplifted torso and outstretched arms.

Hisa Ōta (1868 – 1945)Known by the name Hanako, the twice-divorced Geisha started touring Europe in 1904 and arrived in Paris in 1906, when she met Rodin. She returned to Japan in 1916, to recruit more dancers, and toured Europe until she returned to Japan for good in 1921.

One of her most famous performances involved her interpretation of a suicide, and it impressed Rodin so much that he sculpted her face in multiple masks. He donated her two of them she brought with her in Japan.

This is how Rodin’s biographer remembers her session:

Hanako did not pose like the other models. Her features were contracted into an expression of cold, terrible anger. She had the look of a tiger, an expression completely foreign to us Occidentals. Using the force of will with which the Japanese confront death, Hanako was able to hold this expression for hours.

Darling, you’ve never seen a woman this angry because “us Occidentals” lock them into an asylum to wither and die.

This variant of the mask is preserved at the MOMA.Carmen Damedoz (1890 – 1964)

This variant of the mask is preserved at the MOMA.Carmen Damedoz (1890 – 1964)If you’re thinking “Oh, like the aviator?” I’ll have to stop you immediately: she is the aviator.

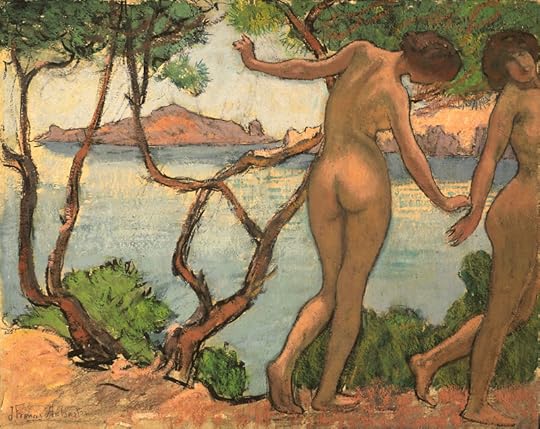

She was born in Paris from a French family, and adopted the Hispanic-sounding pseudonym to complement her natural complexion. She modelled for many artists, including Alberto Giacometti, and we have some flaming letters that might suggest an affair between her and Rodin. Jean-Francis Auburtin painted her several times, almost always from the back

She became a pilot in 1913.

Jean-Francis Auburtin, Carmen Damedoz (model of Rodin)Isadora Duncan (1878 – 1927)

Jean-Francis Auburtin, Carmen Damedoz (model of Rodin)Isadora Duncan (1878 – 1927)It would take me a book to summarize her importance, and I have neither the time nor the preparation to do it. Suffice it to say that she was born in American and lived as a complete and utter legend throughout Europe, the US and Soviet Russia.

She was a non-conformist from the start, taking inspiration from everything that was not classical dance: she looked at Greek vases and bas-reliefs in the British Museum while in London, danced in the salons of Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux and Princesse Edmond de Polignac while in Paris and eventually started touring with Loïe Fuller and they experimented together, receiving mixed reactions from critics which meant they were doing things right.

“[She] has this gift of gesture in a very high degree. Let the reader study her dancing, if possible in private than in public, and learn the superb ‘unconsciousness’ – which is magical consciousness – with which she suits the action to the melody.”

– A. Crowley on Duncan’s dancing (whom he called “Lavinia King”)

She became known for her eccentric acquaintances and her participation in extravagant avant-guards, such as the 1911 party thrown by the French fashion designer Paul Poiret, who rented a mansion and re-created La fête de Bacchus, the Bacchanalia hosted by Louis XIV at Versailles.

Despite these occurrences, she disliked money and thought it tainted her primary vocations: creating beauty and teaching. She opened her first school 1904, in Berlin, and it was a philosophy school where young women could approach her idea of dance: it became the birthplace of the so-called “Isadorables”, Duncan’s protégées.

Her figure and personality inspired Rodin to create a marble sculpture called Ève au rocher, Eve on a Rock, from 1905-1906. We think he had seen and talked to her during a jeune danseuse where he was invited by his friend, the symbolist artist Eugène Carrière, who also painted Duncan in a ghostly portrait from 1910. When Rodin was offered the Légion d’honneur in 1903, many of his friends threw him a lavish party in Vézely, and Duncan performed for the occasion.

Colonialism put up a show of itself around the second half of the 19th century, with the birth of the so-called International and Universal Exhibitions, the first of which took place in London in 1851. These events attracted tens of millions of visitors, and allowed the various nations to present industrial and technical innovations as well as some of their intellectual and artistic productions, but the participation was limited to a certain set of Countries. Peculiar, for a thing called “Universal”.

Colonial Exhibitions were organised in the same period, inviting various European nations to put on display the products from their colonies and the people they were destroying, subjugating and killing over there.

Among the initiatives of the Universal Exhibition of 1889, Rodin saw the performance of a troupe of Javanese male and female dancers from the city of Solo (Surakarta), who were performing in Paris for the first time on that occasion. The sculptor’s presence in the audience is proven by some sketches preserved at the Musée Rodin. The effect of this discovery, however, was nothing like the one produced on him in 1906 by the Cambodian dancers.

Sisowath, the King of Cambodia, and his daughter Princess Symphady, had travelled to Paris that year, accompanied by some members of their court and seventy dancers.

Rodin first saw them at two special performances offered in Paris and then again at the Colonial Exhibition in Marseilles, in 1906 when he would also meet Hanako, and was thunderstruck.

Alda Moreno (1880 – 1963)“the enchantment of my life… dancing figures in marble conceived by Michelangelo…’.

We know very little of Alda’s life. What we know is that, in June 1812, Rodin’s patron and collector Count Henry Kessler was shown some of Rodin’s studies and defined her as:

“a very supple, girl, a kind of acrobat, whose poses provide all kind of entirely new and bizarre arabesques.”

She worked an acrobat and modelled nude for him through 1903, until she disappeared in 1905. She was having an affair with one of Rodin’s friends, though I wasn’t able to find out with whom.

Rodin searched for her everywhere, as she wanted her to model for him again: eventually, a friend saw her nude photographs in the November issue of Le Nu académique. He was able to track her down, and convinced her to model for him again: from this series of works, Rodin drew his series “the creation of woman”.

To him, her poses were “something like the stages of an evolution, transitions leading from the animal world to woman”.

Rodin kept these works very secret, and they were only recently discovered.

The last dancer of the selection, she’s even more mysterious than the previous: we don’t know her birthplace, we don’t know her real name and we can only guess her birth year.

The first account we have of her comes from The Grazer Volksblatt newspaper in 1911, stating she was performing in the Berlin Überbrettl cabaret as “Duncan imitator.” She performed her own version of the Dance of the Seven Veils while reciting the tragic woman’s last monologue as written in Oscar Wilde’s Salome, and her performances incorporated themes from paintings by contemporary artists such as Franz Stuck and Arnold Böcklin. She was her own choreographer, designer, trainer. She used to appear unclothed and was prosecuted twice, and acquitted in Munich where the jury stated her performances were a work of art.

The dancer is shown, nude and performing, in a picture taken in Rodin’s atelier while she sports a hairstyle from a Greek vase.

Rodin’s WorksThe works showcased in the centre of this room are a set of clay figures, which Rodin used to sculpt and then dismember, reattaching pieces and torsos back again in new poses.

On the background on the left, photographs and details from the dancers show us some of his inspirations: Ruth St Denis in yogi position, Loïe Fuller‘s hands (I swear to God I could fall in love with these hands), the naked picture of Adorée Villany, and Carmen Damedoz dancing with a shawl.

The centre portion is made of sketches, through which Rodin tried to encapsulate the most complicated vibrations of a dance, and in between we can see a chalk sculpture, Study for Iris, from around 1892. This doesn’t differ much from the bronze he will make 1895, called Iris, Messenger of the Gods, also known by less mythological names such as Flying Figure, or Eternal Tunnel. It was a part of Rodin’s second (and second-time failed) for a monument to Victor Hugo outside the Panthéon in Paris, a monument he envisioned as a sculpture of the writer being accompanied by three female figures representing Young Age, Maturity and Old Age. Iris was neither of them, but a fourth figure personifying glory, of the spirit of his age, hovering over Hugo’s statue. Too bad that glory, at least in Rodin’s idea, had her legs spread, her right hand clasping her right foot, and a crude depiction of her genitalia for everyone to admire.

On the other side, other sculptures complete the room, with smaller clay studies and an audio-video installation.

http://www.shelidon.it/splinder/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/20231127_150336.mp4The Red Room: Cambodia, Japan and Other HorizonsThe room hosts some of the sketches the artist made when he saw the Javanese dancers, and a central piece showcasing some pieces — both original and made by Western — to signify the tremendous impact that these touring oriental shows had on the imagination of Rodin’s contemporaries.

His drawings have a futurist quality to them (the Manifesto of Futurism was published in 1909) and capture motion more than form, often exaggerating fingers and curves to highlight a certain movement, a particular vibration.

On the walls, works by contemporary artists are displayed as videos or pictures of performers posing with Rodin’s statue in Paris.

Alessandra CristianiShe’s the author of a trilogy of performing pieces called The Question of the Body and the Art of Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon, Auguste Rodin, each of which explores a different aspect of the tormented art of this men through the use of her own body.

Corpus delicti – from Egon Schiele is the first piece and starts with the dancer dressed only in a scarf, a gift from her mentor Masaki Iwana. Starting with by a patter of rain, which soon becomes the roar of the elements, the dance expresses impulses of female eroticism contaminated by the passing years, sometimes yearnings for protection, other times laying derelict and abandoned to solitude after intercourse. The light flashes over disjointed limbs, highlighting bodies made of tense nerves, melted makeup and dishevelled hair as it happens in Schiele’s paintings.

Nucleo – from Francis Bacon starts with scenic elements such as a wine goblet, a wooden pallet with scattered photos, a chair, a large white vertical canvas: the dancer starts in slow potion and then picks up the pace, but we’re far from Schiele’s passions. She’s circumspect, astonished, terrified. The wine overflows, she shakes, while sounds of nature starts screaming in the background. The body is shattered.

Naturans – from Auguste Rodin is the last piece and we find ourselves in a workshop. We hear rollers scattering, electric saws, drills, chisels, hook knives. The performance is an act of birth where the raw materials are broken and bent to create a form, whether willing or unwillingly touched by the hands of the creator. Violence and abuse are at the centre of this performance each time the matter seems to be resisting, each time sounds torture the unwilling and contorted body of the dancer.

Rodin is one of the main shows ideated by Julien Lestel’s corp-de-dance, founded in 2007.

It’s a sensual show, marked by virtuosity and sensuality, without many of the tormented traits Cristiani explored so successfully: it proposes a new interpretation of Rodin’s personality where an intense physical dialogue takes place between the ancient idea of sculpture and matter, the mystery of substance and nature, carnal fantasies and a phantasmagoria of corpses that can be solitary or entangled, anchored to the ground or taking flight, afflicted or exultant, seductive or distressing.

One of the most obvious quotes of the show is from the Age of Bronze, also in the next room of the exhibition. More parallels and references can be seen here.

Dancer, choreographer and historian, Schwartz proposes a show made of corpses and matter called Jaillissements and dedicated to the sculptor’s relationship with Isadora Duncan. The choreographic composition is based on the aesthetic principles of Isadora Duncan’s dance as she would teach them in her school, and draws from the principles of Rudolf von Laban, a late XIX century dance artist, choreographer and dance theorist. The term “jaillissement” is French for sprout, gush, also used metaphorically as an explosion of ideas.

Florin Ion Firimitã is a Romanian-born visual artist and writer who has lived in the US since 1898. He worked on some stills where a model is shown in conversation with works from the Rodin Museum, and I can only show you a couple of them, but I urge you to go and see them for yourself. They’re featured here.

Another visual artist, he’s a photographer and filmmaker who mostly works on bodies. In the exhibition you will find some photographs, but I suggest you also check out his book with sketches and stills from his movie film inspired by the French sculptor.

As he himself explained, movement was inseparable in Rodin’s work from a constant concern to represent nature and what he perceived of it. Lending movement to his sculptures allowed him to represent the skin stretched over the muscles of the model in tension, allowed him to depict the “protrusions of internal volumes”, as he would put it.

In this room, alongside more videos of other performers, we find the Walking Man, The Bronze Age, and a stunning piece called The Toilet of Venus.

The Bronze Age, compared with a scene from the ballet by Julien Lestel.

The Bronze Age, compared with a scene from the ballet by Julien Lestel.Also referred to as The Bather, The Wave or The Awawkening, the Venus has great similarities with other works such as the Kneeling Fauness in the left half of the tympanum of the Gates of Hell. In this version, the head of the figure is leaning back and facing to the right, a posture that Rodin used to illustrate the poem Le Guignon (Evil Fate) by Charles Baudelaire in Les Fleurs du Mal.

To lift a weight so heavy,

Would take your courage, Sisyphus!

Although one’s heart is in the work,

Art is long and Time is short.

Far from famous sepulchers

Toward a lonely cemetery

My heart, like muffled drums,

Goes beating funeral marches.

Many a jewel lies buried

In darkness and oblivion,

Far, far away from picks and drills;

Many a flower regretfully

Exhales perfume soft as secrets

In a profound solitude.

Because people would freak out if you held an exhibition on Rodin and didn’t feature a version of this guy, I guess.

The last room features three more videos from three more performers who were inspired by Rodin: Boris Eifman, Anna Halprin, and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. I’ll leave you with them in reverse order.

The performance was created at the invitation of the Beyeler Foundation in Riehen/Basel, Switzerland, for an exhibition called Rodin/Arp which was being held at the museum. The works of Auguste Rodin and Hans Arp are mixed in the movements as two attracting opposites: Rodin’s powerful obsession with the human body and its implicit narrative capacity is balanced by Arp’s desire for formal emancipation. The show is called Dark Red – Beyeler, possibly to highlight this duality.

Journey In Sensuality is more than a dance: it’s a movie and a documentary, an intimate account of the fusion of Halprin’s art with Rodin’s spirit. Directed by Ruedi Gerber, the movie shows us the dynamic bodies of modern dance engaged in conversation with the static statues. The performance is immersed in nature, but I had to bolt out of the room at the close-up of a naked dancer being bitten by mosquitoes. Sorry.

Boris EifmanAn absolutely stunning ballet called Rodin, Her Eternal Idol, is definitely my favourite, here, as it tells the story of Rodin with Camille Claudel, the unrecognised disciple who died in an asylum.

“The story of life and love of Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel is an amazing tale about an incredibly dramatic alliance of two artists where everything was entwined: passion, hatred and artistic jealousy. Spiritual and energy exchange between the two sculptors was an outstanding phenomenon: being so close to Rodin, Camille was not only an inspiration for his work helping him find a new style and create masterpieces, she also impetuously went through the development of her own talent becoming a great master of sculpture herself. Her beauty, her youth and her genius – all this was sacrificed to her beloved man.”

Just take a look at a piece of it and marvel at its beauty.