Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 42

December 11, 2023

Calculating Empires

Kate Crawford and Ivladan Joler present us a monumental work, through the temporary exhibition Calculating Empires currently on display at the Osservatorio Fondazione Prada (Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II). It’s going to stay on for two months only (it closes on January, 29th to be precise) and I cannot urge you enough to go and visit it. It’s almost entirely in English which is why, in a few hours, I’ll drop a rare Italian article as a vademecum to my fellow countrymen.

For everybody else, you can start by buying Joler’s Black Box Cartography – A critical cartography of the Internet and beyond, part of which is on display, and Crawford’s Atlas of AI. If you’re really an asshole, you can buy them on Amazon too. You’ll have to pay for shipping and the books have no cover thumbnail, which I didn’t think was possible.

I’ll give you an excerpt of the brief overview you can read at the entrance.

Curated by researcher-artists Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler, “Calculating Empires” exhibition project charts our technological present by depicting how power and technology have been intertwined since 1500. By merging research and design, science and art, Crawford and Joler create a new way to understand the current spectacles of artificial intelligence by asking how we got here, and considering where we might be going. This mind-expanding installation invites visitors to experience the longue durée through a visualization of time, politics, and technology historically obscured by cultures of corporate secrecy and technical architectures, the complexities of colonialism, planetary supply chains, opaque labor contracting, a lack of regulation, and by history itself.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is the Calculating Empires maps room. Here the audience is immersed in a dark environment-like walking into a literal black box. Presenting itself as a codex of technology and power,

Calculating Empires shows how the empires of the past 500 years are echoed in the technology companies of today. This detailed visual narrative extends over 24 meters and illustrates forms of communication, classification, computation, and control with thousands of individually crafted drawings and texts that span centuries of conflicts, enclosures, and colonizations. One map reveals the multiplicity of our communication devices, interfaces, infrastructures, data practices, and computational architectures and hardware. The other map explores how these technologies are woven into social practices of classification and control: from prisons to policing, time to education, colonialism and economic production, to the multitude of military systems.

To contextualize this new work, the visitor first encounters Crawford and Joler’s Anatomy of an Al System, an exploded view diagram focusing on the case study of the Amazon Echo voice-assisted Al. This anatomical map visualizes the three central extractive processes required to run any large-scale Al system: material resources, human labor, and data. Where Calculating Empires is about time, Anatomy is about space.

The exhibition concludes in a cabinet of curiosities, an eclectic collection of books, devices, and ephemera spanning from 1500 to 2023, and in a small library that invites visitors to read, reimagine, and write their own additions, revisions, and complications of history. Any exhibition that spans centuries will necessarily be incomplete, impartial, and subjective: it can never be finished. So these maps are designed to be open to feedback, and to change over time.

Well, since you’re asking… The concept of digital labor triangle, borrowed from Marx and adapted to our digital realities through heavy use of Plato, is powerful and undeniable: the content-creator is willingly subservient in a situation where he’s consumer, product and worker at the same time, and the content he absorbs is a phoney projection of another digital worker, locked in their own cave. I don’t disagree with that. Far from it.

The main idea is explained here.

Allow me, however, three main points of disagreement.

1. Is the projection systemically phoney?The idea of our digital self being a projection not very far from the shadows in Plato’s cave is not created by the system or, at least, it’s only partially created by our willingness to conform. And of course, this willingness is systemic, I’m not denying it, but it’s a chain that can be broken or at least shaken a bit even by staying in the system.

The constant showcase of our happier and wealthier versions through social media, for instance, is only one side of a coin in which it’s possible, albeit made more difficult by the algorithm, to share valuable and honest content, and create meaningful connections.

The role of the user as a willing prisoner is underplayed here, and the option of tricking the system by casting different shadows is not explored enough.

You know how much I love this.2. Where’s the trade-off?

You know how much I love this.2. Where’s the trade-off?Again, the idea that technological colossi like Amazon and Google create singularities in the digital (and I would argue physical) fabric is absolutely on-point, and I can understand why one could say that people get dragged into them: you have friends on Facebook, who increase the pull of the singularity, and you resist joining the network up until a certain point where you have literally no other option but to join it if you want to stay in touch with your friends and basically carry on with your life. It happens to me as well, all the time: I eventually joined Instagram as compensation for my sabbatical from Twitter and LinkedIn, I started displaying more of my work through stories on Instagram because the algorithm over there demands it and I want to increase my engagement before Twitter is dead, etc.

The idea that a user is swimming against the current and being dragged into the holes is a romantic one, but I do believe it’s wrong in most cases. People swim towards the current because those singularities offer commodities and services in return. In technology implementation, it’s a concept we know as trade-off: every time you ask the user to modify their behaviour, you need to offer something in return. If you don’t, or if your offer isn’t palatable enough, your users will reject your offer and keep doing what they’ve been doing.

The 75 Tools for Creative Thinking include several activities on the concept of trade-off, including a titular one in the “Break Free” category.

The 75 Tools for Creative Thinking include several activities on the concept of trade-off, including a titular one in the “Break Free” category.Come up with ideas

that consider

what people are willing to trade off

as an alternative to their current behaviour.

How do you convince people to upload their personal pictures instead of keeping them in their homes? You offer them unlimited storage space and the possibility of easily sharing those pictures with other people. How do you convince people to tell them their demographic data, such as their birthdays? You introduce a function reminding their birthday to their friends. How do you convince people to produce content for your platforms? You promise that, if that content is produced following the rules, their digital persona will be appreciated, and they will receive a gratification they’re often not getting at work.

Trade-offs are everything: people are willingly swimming towards those singularities.

This doesn’t however mean that the commodity delivered by the trade-off isn’t real, isn’t valid and cannot have a positive impact on people’s lives. The connections you make online can be valuable, people are improving their jobs and meeting new clients. This makes the system a lot more complex than presented.

3. No slavery comparisons, pleaseIn multiple points across the exhibition, the subservience of the digital worker is compared to the Atlantic Slave Trade, and Joler himself uses the expression “slave” with much freedom.

The guy looks like this.

The guy looks like this.If you’ve been following me through objections number 1 and 2 you’ll know why this comparison cannot stand: if it’s true that the modern digital worker is entrapped in a cage, and the cage is not of their own making, it is also true that we accept the deals offered by the digital platforms.

Consequently, by proposing that a willing participant in a system is a “slave”, the authors are failing to consider one point: there’s no trade-off in the physical deportation of millions and millions of people across the ocean so that they can work your fucking fields. To a philosopher, the level of choice might seem similar, but we cannot ignore the stakes when we elaborate on such concepts. No one is flogging me in the morning if I don’t open my cellphone and start posting, I’m not forcefully taken away from my family so that I can go write a tweet, a guy named Jeff isn’t entering my house through my cellphone to rape me. Plus, I do gain something from my unpaid labour: I gain connections, community, visibility, value of a digital self I do employ in my seeking for a job. Unfortunately, new African-American history standards approved in the United States promote the idea that Black people benefited from slavery too. Which is of course appalling and we cannot be complicit.

December 10, 2023

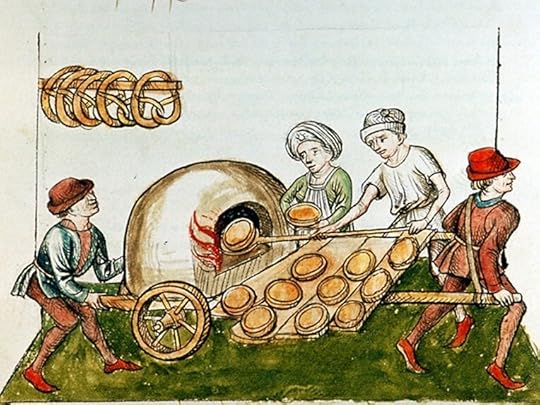

#AdventCalendar Day 11: Tarte of Apples and Orange Peels

Another recipe from Thomas Dawson’s The Good Huswifes Handmaide for the Kitchin (1594), gives us a nice easy pie that I’ll never be able to make. Maybe you’ll have better luck.

Beware: this recipe takes three days (which is why I cannot do it: I’ll do the first step and then forget all about it).

Peel the orange as thin as you can, removing as much of the white as possible: the more you’ll be able to do this, the less bitter your pie will taste. Take the peels and let them macerate in a bowl of water for around 8 hours. Overnight should do.

Day 2Drain the orange peels, put them in a pan and add 600 grams of honey and half a litre of water, lit a soft flame underneath it and bring it to a slow boil. Reduce the flame, then, and leave it there for around 2 hours, stirring from time to time and checking the honey doesn’t turn to caramel. If needed, add more water. After it’s done, remove it from the fire and let it sit for another day.

Day 3Slice the peeled apples and chop them in small cubes, mix them with 50 grams of sugar, 1 teaspoon of cinnamon and 1 teaspoon of ginger.

Drain the orange peels from their sugary water and, on the side from the apples, mix them with 100 grams of sugar, another teaspoon of cinnamon and another teaspoon of ground ginger.

If you’re doing the pastry yourself, now it’s the time: mix the flour and the sugar, place them in the form of a small volcano, and then add small pieces of butter, a pinch of salt and one egg. Start working them together and, if they mixture starts misbeheaving, remember the trick:

wash your hands with very cold water: heat is your enemy when making this pastry;add another egg;as soon as it looks like it’s holding together, wrap it in cellophane foil and slap it into the fridge.Lay the pastry and, if it’s not buttery enough already, put some curls of butter on the bottom, add a layer of apples and cover them with the orange peels, then another layer of apples and so on until you’re out of them. Cover the pie with slices of pastry, so that some of the apples are peeking out from the louvres.

Bake the pie for 50 minutes in a pre-heated oven that’s not too hot (180 °C should do).

Meanwhile, mix 4 tablespoons of sugar with the rosewater and, when the pie is almost done, take it out of the oven, brush the surface with its mixture, and put it back in.

Bake it for an additional 10 minutes.

‘To make a tarte of apples and Orange peels. Take your oranges, and lay them in water a day and a night, then seethe them in fair water and honey. Let them seethe till they be soft. Then let them soak in the syrup a day and a night. Then take them forth and cut them small, and then make your tart and season your apples with sugar, cinnamon and ginger, and put in a piece of butter. Lay a course of apples, and between the same course of apples, a course of oranges, and so course by course. And season your oranges as you seasoned your apples, with somewhat more sugar, then lay on the lid and put it in the oven. When it is almost baked, take rosewater and sugar, and boil them together till it be somewhat thick, then take out the tart. Take a feather and spread the rosewater and sugar on the lid, and set it into the oven again, and let the sugar harden on the lid, and let it not burn.

Wich Oranges?At this time, the only available oranges were Seville Oranges, very small and very bitter. Nowadays, they’re mostly used for marmalades. They originated in Southeast Asia and arrived in the Islamic world through India as early as 700 A.D. In the 10th Century, the Islamic domain brought these oranges to Spain and, from here, they were known to the rest of Europe.

The sweet orange is not a wild fruit: it was born from domestication and hybridisation of this orange with mandarins, probably due to Italian and Portuguese merchants.

What about Apples?In early 1533, Anne Boleyn developed a craving for apples, as she was now pregnant with the future legendary Queen Elizabeth. She had been formally married to the King since January, 25th (though they allegedly married in secret on November, 14th 1532), and would be crowned Queen on June, 1st of the same year. Elizabeth would be born on September, 7th.

She would have enjoyed this tart.

Note: the picture in the header is from another recipe, Apple and Quince Pie, and you can see it on this website.

December 9, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 10: Rabbit Soup à la Reine

Today I bring you an old recipe reinterpreted through a Victorian’s eyes. If you’ve been following me for a while, you’ve seen this already in one of my long articles on the Ingoldsby Legends, specifically the one on The Lay of St Cuthbert.

Ingredients (for around 3 liters of soup):3 young rabbits (approximately 200 grams of chopped meat should do, but you’ll need bones and their remains as well);4 liters of clear veal broth;2 onions;1 head of celery;3 carrots;aromatic herbs at will, such as thyme and marjoram, wrapped in a small pocket suitable for cooking;2 blades of mace and a spoonful of pounded mace;half a teaspoon of white peppercorns;a pinch of salt;cayenne pepper, if agreeable;250 grams of milk cream;1 tablespoon of starch such as arrowroot;tarragon or chive for garnish.Recipe:Wash and soak the rabbit meat, put it in the soup pot and pour the veal broth, letting it stew gently for 30 minutes. The original recipe requires that you put them whole and then take them out, skin them, flesh them and all that jazz. I don’t expect you to: you can use skinned rabbits or the chopped flesh directly, but mind following at least this step: take the chopped pieces out of the broth and mince them after they have been stewing for thirty minutes. If you put minced mean directly in the broth, it will disappear, and you won’t be able to blame me.

Also, make sure to take away every single grain of fat from the meat, because rabbit fat is thoroughly disgusting.

Put the meat aside, but the broth should simmer a little more with the rabbit bones or the rest of the body. If you used chopped meat, you should at least have the bones but I suggest you add some remains like giblets: you can ask your butcher for them, or – if you live in a bit city like I do – they’re usually on sale in a special isle of the supermarket. Add the chopped onions, the celery, carrots, the small bag of savoury herbs, the mace, peppercorns and a pinch of salt.

Stew for three hours.

Yes, you heard me right. It’s a soup.

If you’re not dead by the time it finishes, strain it off, let it settle and pour it into a clean pan, mixing it with the pounded rabbit flesh while the broth is hot. Do it with care, small portions at a time, minding that the minced rabbit doesn’t gather into spontaneous meatballs. Add some more pounded mace, an additional pinch of salt if you like it savoury, cayenne pepper, put it back on the fire and stir it continuously. When it boils, mix the cream with starch and add it. You can also add a single spoonful to each dish if you prefer it, and garnish with some tarragon or chive.

Where does it come from?This particular version is Rabbit Soup à la Reine within Eliza Acton‘s Modern Cooking for Private Families (1845). Should you not like rabbit, there’s a similarly called recipe in the same book, featuring oysters.

Four things to see in Bruges

Bruges is a truly enchanting city, especially if you have a soft spot for waterways, and it’s truly difficult to select only four things to see (but I had to: they were two in Ghent, three in Antwerp… it’s all about the progression).

There are a couple of spots everyone visits and I won’t be mentioning them because they’re fairly obvious: the Rosary Quay (Rozenhoedkaai), Ezelpoort, the Conzett Bridge… basically if you follow the waterways, you’ll find charming spots at every corner.

Seriously, this place is awesome.

Seriously, this place is awesome.I’ll try and point out a couple of other places instead.

1. The Basilica of the Holy BloodIgnore the upstairs church, where a serious priest sits all day in front of a piece of cloth and loudspeakers are boasting worship of the titular holy blood, brought back to Europe while we were ravaging the Middle East. Stay downstairs instead, and turn left, push through the door and enjoy the silence.

The building consists of two chapels one on top of the other, and the lower one, the chapel of Saint Basil, is one of the best-preserved Romanesque churches in the West Flanders. It was built between 1134 and 1149, and it’s dedicated to Basil of Caesarea because of another relic that was brought back by Count Robert II from Cappadocia (modern Turkey). It is scarcely decorated, aside from a stunning XII representation of the baptism of Saint Basil you’re likely to miss if you don’t enter the annexed chapel to the right and turn around: it’s on the tympanum above the connecting door.

If you want to go upstairs, you’ll do so through a stunning staircase with double heights, a marble-lined brick ceiling and beautiful stained glass windows overlooking the Burg square. I have no idea why the windows bear the Tudor rose.

The entrance of the Basilica is also worth a mention, as it’s not your traditional church: all it offers to the square is a slice of a Gothic facade, and those windows you see are the ones giving light to the staircase. The golden statues represent angels on the upper level, and historical figures on the lower one.

2. The Church of Our LadyThey will tell you that you have to go there because there’s a statue by Michelangelo and I’m not saying I disagree. It’s cute. I’m just saying there’s so much more to see than that.

2.1. The Painted GravesAccording to what’s written on the plaques, around 1270 it became customary to paint the inside of brick-lined graves. It’s unclear who started the tradition, but if you have to spend all eternity locked inside a box I agree you’re going to need something to read.

The Virgin and the Child are usually depicted at the door end, to intercede with God on behalf of the deceased, while the crucified Christ is often depicted at the head end. The sides are decorated with angels, often with incense burners to fend off the smell of decay, who had the task of accompanying the dead to Heaven.

The plaque describes these works as “rudimentary”. We have two very different ideas of what the word means.

The plaque describes these works as “rudimentary”. We have two very different ideas of what the word means.What’s astonishing is that the artist had very little time to paint these pictures, as the deceased were often buried on the same day they died: they painted freehand on the wet, quick-drying lime and this results in pictures of astonishing vividness. By the XV century, paintings were replaced with drawings on paper.

2.2. The tomb of Charles the Bold and Mary of BurgundyThey won’t tell you much about the people behind these two stunning golden sepulchres placed at the centre of the apse, but boy, oh boy, there is stuff to tell.

Charles the Bold was Duke of Burgundy from 1467 to 1477, when he died in the battle of Nancy and his body was allegedly found stripped, half-chewed by wolves and half-embedded in frost, up to the point that they had to go and fetch specific instruments to carve him out of the ice.

The corpse of Charles the Bold discovered after the Battle of Nancy, by Charles Houry (1862)

The corpse of Charles the Bold discovered after the Battle of Nancy, by Charles Houry (1862)Mary of Burgundy was the daughter of Charles from his second marriage to Isabella of Bourbon, and married Maximilian of Austria right shortly after her father’s death in battle, to fend off the French king Louis XI who wanted her lands. Right before her marriage, in fact, she had been forced to sign a charter of rights known as the Great Privilege, in the nearby city of Ghent, which reinstated to the provinces several privileges her father had revoked. Amongst these, she was not allowed to marry, to declare war or levy taxes without consent of the States, but her marriage to Maximilian had already been officiated, if not officialised. She and her husband slowly weakened the treaty, until it was abolished in 1482. She wouldn’t be alive to see this, though: she had befallen an accident during a falcon hunt in the woods near Wijnendale Castle, where her horse had fallen upon her, breaking her back.

Their court is said to be the origin of the legend of Dr Faust, as the priest, abbot and humanist Johannes Trithemius was accused of necromancy and, according to Luther, had summoned the spirits of past leaders to entertain the couple.

3. The City HallBuilt in a late-Gothic style between 1376 and 1421, the hall stands in Burg Square and it’s one of the oldest city halls in the region. That’s why a local architect called Louis Delacenserie and a neo-Gothic architect named Jean-Baptiste Bethune thought it best to restore the interiors and, between 1895 and 1905, they created a fake timber structure and decorated the walls with colourful scenes of the city’s history.

This is not why I’m recommending you to go.

http://www.shelidon.it/splinder/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/20231204_150921.mp4The thing you need to see is in the annexe room, and it’s a large augmented reality map telling you the territory’s history. If you wish to understand the long and complex relationship between the region and water, from Roman to modern times, you can’t miss this installation where a soothing voice (at least in English) will guide you through the many changes and evolutions, floods and human interventions, of this fascinating land.

A mention of merit to the one who thought to have earphones in different colours based on the spoken language, as it somehow creates an unspoken connection between visitors and it mitigates the sense of isolation and alienation these shows might unwillingly inspire.

The structure is one of the few preserved beguinages in the area, which means a settlement where lay, independent women lived a self-sufficient life of sharing and communing around the values of early Christianity (more on that later).

The beguinage was founded around 1244 by Margaret of Constantinople and was recognised as an independent parish in 1254. Its complete name, “Princely Beguinage Ten Wijngaerde”, refers to 1299 when it came under the direct authority of King Philip the Fair.

The complex includes a Gothic church and around thirty white-painted houses of later construction, dating between the XVII and the XVIII century, built around a central yard. Access is through the three-arched stone bridge, the Wijngaard Bridge, where you can see an effigy of Elizabeth of Hungary, the matron of many beguinages. The gate itself is from 1776.

The canal ends up in the Minnewater, the Lake of Love, where tons and tons of swans swim around.

Do not be fooled by these beasts’ appearance: they have a legendarily bad attitude, and I mean it literally.

4.1. The Curse of the SwanAs you’ll read at the Lanchlas Chapel in the abovementioned Church of Our Lady, swans in Bruges are connected with the revolt of the Flemish provinces.

Pieter Lanchals, in fact, was a close friend and advisor to Archduke Maximilian of Augsburg, husband of Duchess Mary of Burgundy. When the Flemish provinces rebelled against the Archduke in 1488, Lanchals was imprisoned and beheaded in the Market Square of Bruges, and Maximilian was forced to witness his friend’s execution.

Legend says the archduke cursed the city in a very peculiar way: since Lanchlas’ crest was a swan, he compelled the city to keep swans in the Reie River.

They are not friendly. They’re not friendly at all.

We still use the word, in Italy, to indicate an unmarried woman that’s unhealthily connected to the church and usually doesn’t have a life of her own: she’s generally nosy, not very attractive, and judgmental.

As it turns out, this is the legacy of a successful discrediting campaign.

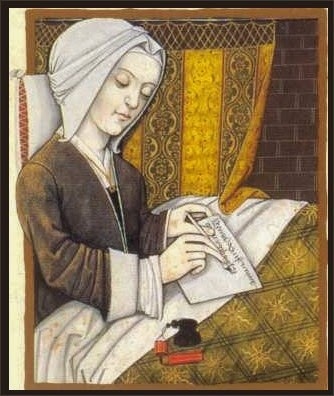

In her wonderful Heretics: Stories of Women Who Reflect, Dare and Resist, Adriana Valerio dedicates a section to the beguines in Chapter 3 on the spiritual unrest stirring in the Middle Ages and involving women of all social classes.

Popular religiosity and reform movements spreading through Europe during the Middle Ages, were not so much focused on theological disputes when they involved women — contrary to what happened in other, more masculine contexts — but instead focused on the search for a way of life that was more adherent to the Gospel and the example of the first communities described in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 4:32-35).

All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had. With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need.

Many women believed Christianity had to be lived in poverty, charity and apostolate, and joined reflection groups who were meditating on the pages of the Bible.

Around 1091, Bernard of Constance was already pointing out how many laypersons, both women and men, wanted to shape a religious experience that recalled the proto Christian communities, and — almost two centuries later, in 1274 — a concerned Gilbert of Tournai told the Council of bishops fathered in Lyons about the phenomenon of the mulierculae (“pseudo-women”) called “beghine” who, in northern France and Belgium, dared to read and comment publicly on the Bible in the vernacular, attracted by the subtilitates et novitates of theological questions.

That’s the first account we have of the word used in connection to these groups of women, and you can already see the contempt reeking from the diminishing term “mulierculae”.

The name’s etymology is uncertain, and some trace it back to the Old Saxon beggem, meaning “to pray”.

Among us are the mulierculae called beghines, some of whom are noted for their subtlety and openness to novelty. They possess in the common Gallic idiom the mysteries of the Scriptures, mysteries that are barely accessible to Scripture specialists. They read them in public, without respect, in conventicles, in squares.

According to Valerio, it’s not easy to reconstruct the complex and variegated world of the beguines, both because of the differentiated experiences that are hidden under such a generic or equivocal name, and because of the temporal extent of the phenomenon (from the XII to the XV century), and finally because of its geographical extension.

Appearing in the Netherlands at the end of the 1100s, this peculiar female presence spread rapidly, especially in the Rhineland, Provence and central-northern Italy, and was immediately perceived as a novelty in the panorama of religious movements of the time, generating astonishment and more than a little apprehension in the ecclesiastical hierarchies.

These women, in fact, wanted to experience a life of faith that was not closed within monastic walls but, on the contrary, open to the needs of the society in which they were deeply involved: they were economically autonomous because they carried out manual labour (in Bruges it was lacework), they engaged in charitable works aimed at the poorest and most marginalised, they were connected to other women with whom they shared the need to pray and study sacred texts, and they were united by an intense mystical experience that they sometimes put down in writing in their mother tongue.

For the beguines, the main focus was the problematic reconciliation between ecclesiastical practice, marked by economic interests and power, and the message of Jesus, which called for choices of poverty and participation in the condition of the poorer classes of society. The search for alternative ways of life more in line with the evangelical spirit and the need to lead a simple existence like that of the primitive Church became a priority rule of life compared to the obedience owed to the ministers of the cult.

Many of them were considered mentors by disciples who gathered around them, fascinated by the freedom with which they spoke and lived. Ida of Nivelles, Maria of Oignies, Odilia of Liège, Hadewijch of Antwerp, Ida of Gorsleeuw, Beatrice of Nazareth of Lier, Matilda of Magdeburg, and Margaret Porete are just some of the names of these magistraesses who devoted themselves to theology studies between the XII and XIV centuries.

Their literary works, whether they were treatises, letters or poems, were composed in vernacular languages and expressed with the freshness of their mother tongue an intense religious experience usually difficult to communicate through the more algid Latin. This is why women’s writing revolutionised the approach of theological narration.

To a Church preaching images of power, like an all-powerful God and a judging Christ, the lives of these women opposed a communion of intentions, the image of a loving, maternal God and the fragility of a Son who had to be cared for, loved and in whom to recognise and share the weak human condition: a model of a poor community sharing in the misery of others.

Matilda of Magdeburg, for instance, writes The Flowing Light of Divinity to explore the maternal side of God and gives us a vibrant narration of the nativity, where she explores in narrative form what Maria might have done with the gold, incense and myrrh received from the three wise kings. In light of the intellectual movement of the beguines, her answer (in the words of Mary) is obvious:

With the gift brought to my Child [Mary replied] I provided for all those whose need I truly knew. They were impoverished orphans and innocent virgins who were thus able to marry, escaping the risk of being killed by stoning. And also the abandoned sick and the old in old age were to use the gifts reserved for them.

Matilda of Magdeburg

Matilda of MagdeburgSharing was essential for the beguines, as was being autonomous in work, even though their ultimate goal was to transcend themselves and merge with God in a union that excluded any intermediary (sine medio).

These women, driven to express their faith by appropriating unusual spaces of freedom, formed spontaneous aggregations that led to the creation of structures called beguinages, small female communities such as the one in Bruges, that aspired to lead independent and self-sufficient lives.

For these reasons, they attracted suspect from the ecclesiastical hierarchy, which had difficulty controlling such a variegated and dynamic movement and, above all, could not accept the independence of this original spiritual path: a lay and autonomous path that attempted to reconcile personal growth with a community experience of sharing, study and work, and that was so attentive to the themes of renovation many advocated for the Church.

The intervention of the ecclesiastical authorities decided to push these women towards a more controlled monastic life. The strategy, already deployed by Innocent III, was to support the nascent Mendicant Orders (Dominicans and Franciscans) who, by welcoming women who wished to lead a poor and evangelical life, directed them to submit to hierarchical, patriarchal authority.

In this way, discontent could be stemmed by bringing dangerous anxieties for change back within orthodoxy on permissible paths. The Humiliati order, for example, was judged heretical at the end of the XII century but it was reintegrated and recompacted within thirty years, and the downsizing of women’s role played a big part in their readmission: in his Confessio Fidei of 1210, Bernard the First had to swear that no women would take part in preaching.

Matilda of Magdeburg herself, after the synod had taken action against the beguines, followed the indications of the Dominican fathers and entered the monastery of Helfta in 1271.

With the decretal Periculoso et detestabili of 1298, the infamous Boniface VIII steered women towards nunneries, not tolerating any outside activity that was not under the control of the authorities: he established perpetual seclusion for nuns and intensified the work of regularisation — through teaching, preaching and spiritual direction — and repression, strengthening the work of the Inquisition tribunal that had already been active for a century.

In 1311, the Council of Vienna condemned the “errors” of the beguines. The most illustrious victim was Margaret Porete, but that’s another story, and shall be told another time.

If you’re curious (and if you understand Italian), read the book.

If you’re curious (and if you understand Italian), read the book.

December 8, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 9: Boar with Scallions

This is a classical recipe for marinated boar baked with scallions. If you want something older, here you can find a Roman recipe (and the picture in the header).

Ingredients (serves 6 people):1 kg of boar meat, chopped and suitable for a stew;400 grams of scallion;a pinch of fresh marjoram;some sage leaves;abundant thyme;around 10 juniper berries;1 litre of red wine with character (an aged Sangiovese from Tuscany would do);a glass of red vinegar (better if it’s from Sangiovese too);olive oil;black pepper;salt.Recipe:Chop the meat if it’s not chopped already and remember that you have to marinate it first. If you skip this passage, the meat will have an extremely strong flavour, and some people might not like it.

Place the meat pieces in a container that will allow you to cover them with red, wasting the least amount possible: the wine will not be drinkable when the meat is done marinating it. No, I really mean it. Don’t try to drink it.

The meat should stay in wine for at least 12 hours, with a handful of salt and juniper berries. Some people recommend leaving it for 6 hours, changing the wine with some fresh one, and then leaving if again for 6 hours. I guess it depends on how tough the boar was and how much of a fight it put up before ending up in your pantry.

When the meat is done marinating, take it away from the wine and pepper it. Place it in a pan with some olive oil, the vinegar, and bake it in the oven for around half an hour at 200°C.

Meanwhile, mince the scallions and put them in a separate pan, with more olive oil, the sage leaves (you can either mince them or leave them whole), the thyme and the marjoram. Leave them on the fire until they turn blonde, then take them away and add them to the meat. Finish cooking.

Did you know?Juniper is considered a “Christmas tree”.

Many classical authors, from Pliny to Dioscurides, believed the scent of juniper could keep snakes away, and juice from its leaves and fresh berries was believed to cure the venomous bites of vipers and other snakes, some parts of Italy started the tradition of burning a branch of juniper on Christmas Eve, to keep evil away and as an allusion to the salvific destiny of Jesus. Juniper is also prickly, an allusion to the iconic crown of thorn, and its berries are bitter as the “chalice” Christ asked his father to take away from him in the Gethsemane garden.

A further connection between juniper branches and Christmas is made through a legend that says this tree was the only one to offer its branches to the Holy Family as they were fleeing to Egypt.

Other applications included making a decoction from the branch before burning it, and bathing one in this water would chase away sloth.

The resulting cinder had a usage too: aside from being a symbol of humility, it was believed that a mixture of juniper ash and water could cure leprosy.

In Germany, juniper hosts a female spirit, Frau Waccholder, who can be summoned and persuaded to act when thieves have taken something dear to you. If she hears your prayers, the thief will be summoned to appear in front of you and will be compelled to give back what they stole.

Three things to see in Antwerp

Standing at the centre of the most populated municipality in Belgium, Antwerp is the second-largest city in the Country after Bruxelles, and it’s a charming harbour city sitting on the Westerschelde estuary. Its name is said to come from the Dutch handwerpen, “hand throwing“, because a giant called Antigoon used to live on the nearby Scheldt river and used to extort a fee from boats which wanted to pass through: should they fail to comply, he cut off their hands and threw them in the river. This went on for decades until a young hero called Silvius Brabo confronted the giant, was able to defeat him, and served him a spoonful of his own soup: he cut off the giant’s hand and threw it in the river. We aren’t privy to what the river thought of this.

Should you drop by, I have a few recommendations of places for you to visit. There would be four, but the House of Rubens is currently closed.

1. Het Steen and the riverbankThis stone castle is the oldest building in Antwerp, a characteristic that apparently didn’t stop town planners and designers from attempting (and partially succeeding) in ravaging it: it was almost demolished in the XIX century, saved by just one vote against the motion, and a modern extension was hammered through the historical body in 1952.

Still, the XII Century walls provide a charming sight.

If you decide to walk around it, you’ll find yourself by the riverbank and you’ll see the only modern construction I will mention in this Belgian Chronicles: the Cruise Ponton designed by Ney & Partners.

2. The Grote Marktliterally “Big Market”, it’s the central square of the city and it’s a stunning sight, flanked by beautiful buildings all around: the Renaissance Town Hall, a mixture of Flemish and Italian design by one Cornelis Floris de Vriendt. Apparently the blue niche with a statue of the Virgin Mary is a recent addition.

The Town Hall is rivalled by the beautiful guildhalls, each of them with their golden insignia on top.

At the centre, you’ll find the 1887 fountain depicting young Brabo in the act of throwing the giant’s hand away into the river: it replaced a tree which represented freedom and I’m not sure how I feel about this replacement.

In wintertime, the square hosts a Christmas market and an ice ring with sharp wooden corners to test your skating skills.

3. Elfde GebodIt’s a pub. It’s a museum. It’s a stunning place where you can eat a delicious stew, drink your pick of a wonderful beer and be judged by countless statues of saints. Yes, you heard me right.

The first account of the building dates back to 1425, when it was a dwelling for people working in the turbaries (also known as turf bearers). This association still lives in the name of the street: Torfburg. The nearby Cathedral of Our Lady was outside the city walls, back in those days, and the road connected it to the first city centre. Allegedly it also served as a shelter and resistance stronghold during the 1576 Spanish Fury, one of the bloodiest events in Antwerp during the Eight Years War.

When it became property of the church, the house was dubbed ‘Het Paradijs’ (The paradise) and, according to the waiter who attended to our table, it was connected to the cathedral by an underground tunnel: through this passageways, priests and monks came into the building and… well… entertained themselves.

A private collector first established the extensive assemblage of statues you can admire today, with the initial idea of founding a museum, but the enterprise wasn’t successful. The second attempt of establishing a brewery was evidently much better received by locals and visitors alike.

Me and my colleague decided to drink in style.

Me and my colleague decided to drink in style.

December 7, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 8: Jely Hippocras

Allegedly a favourite drink of Henry VIII (a man for which I have zero sympathies, as you might imagine), a recipe of this jelly can be found in A Book of Cookrye Very Necessary for All Such as Delight Therin, compiled around 1591 by one A.W. You can also find a modern version in Peter Brears’ Cooking & Dining in Tudor & Early Stuart England. You can read something about the dish over here. Someone also made a miniature jelly for a doll house, and it’s the most delightful thing ever.

Ingredients:1 liter claret (red wine);300 grams sugar;5 pieces of root ginger;5 sticks of cinnamon;half of a crushed nutmeg;a handful of cloves;a teaspoon of coriander seeds;a pinch of salt;5 leaves of gelatin;a handful of flower petals of your choice (just make sure they’re clean and edible).Recipe:Crumble the cinnamon sticks, crush the nutmeg and grate the ginger root, add cloves and coriander, all into 1 l of hot water, and simmer it (without boiling it) for around 10 minutes.

Pour the claret into a pan, put the gelatine foils in to revive them and leave them there for another 10 minutes. This is what you usually do with cold water, only this time you’re doing it with wine. Just because you can. Strain the spiced water through a cloth, a coffee filter or a very fine strainer, stir in the sugar into the mixture and heat white stirring, until the gelatin foils will have fully melted into the wine.

Put the flower petals at the bottom of a fancy-shaped bowl, pour the gelatine on top of it, making sure not to mess up the arrangement, and leave it in the fridge for a couple of hours.

What’s Hippocras?It’s the name for a wine mixed with sugar and spices, usually heated, and the name comes from the special cone originally used to filter the spices. It’s the one you see in the illustration above.

In her book All the King’s Fools: Disability and the Tudors, Philippa Vincent-Connolly brings forward the argument that lack of exercise from his jousting incident and an awful diet played a big part in the King’s descent into physical decay.

His doctors repeatedly urged him to reduce his tremendous consumption of meat and wine, as he had a penchant for high cholesterol foodstuffs as was documented in the Ordinances of Eltham. […] His diet consisted of over five thousand calories a day, which makes his obesity no surprise. He would drink ale, red wine with sugar instead of water and copious amounts of white bread.

Phillipa Vincent Connolly, Disability and the Tudors: All the King’s Fools

Not drinking water is a good call, water in Tudor England sucked. Still, maybe ale was a much healthier option.

A variantHippocras Christmas pudding is a variant of this jelly. You can see a video of the recipe here.

Two things to see in Ghent

Ghent is a charming and underrated city in the upper region of Belgium, halfway between Bruxelles and the much more famous Bruges. Now, if you go to Bruges first you’ll understand why Ghent is not so famous, and that’s why I recommend you to visit it before you get there. It’s unfair to compare it: it’s like saying Padua is less pretty than Venice. No shit, Sherlock.

Should you decide to listen to me, here’s a couple of things I recommend to see.

1. Saint Bavo’s CathedralA visit to this church is recommended not only from the outside, for its stunning 89-meter-tall tower, but for its beautiful altarpiece.

The place is consecrated to the local patron, Bavo of Ghent (622–659), a saint venerated by both the Catholic and the Orthodox Church, who was converted by Saint Amand and gave away all his riches to the poor. He’s one of the missionary saints who travelled through France and Flanders alongside Amand. He’s often represented as a knight with a sword and falcon.

The church was built on the site of a Chapel dedicated to St. John the Baptist, a wooden construction from 942, and the foundations in the crypt show signs of a later Romanesque construction we know very little about. The current construction began around 1274, and underwent several expansions between the XIV and the XVI centuries. In 1539, the abbey was dissolved as a result of the rebellion of the Flemish provinces against Charles V, who had been baptised in the church. The church became a cathedral twenty years later.

The stunning entrance portal

The stunning entrance portalBetween 2019 and 2021, archaeologists made a creepy discovery on the north side of the church: a layer of human bones called “the bone walls”. Radiocarbon dating suggests they come from the second half of the XV century, but they stand at the feet of walls most likely constructed later, in the XVII or early XVIII centuries.

One source notes that the church’s cemetery was cleared during the first half of the 16th century and again after 1784 when the cemetery stopped accepting new bodies.

A project was founded to examine the skeletal remains to determine the age, sex and stature of the people these bones belonged to, adding stable isotope analysis to reconstruct their diet and origins.

The interiors sport high walls with a lower portion in grey stone and the upper parts in bricks. Someone was evidently afraid of the weight.

The interiors sport high walls with a lower portion in grey stone and the upper parts in bricks. Someone was evidently afraid of the weight.The real feature however is inside the cathedral-

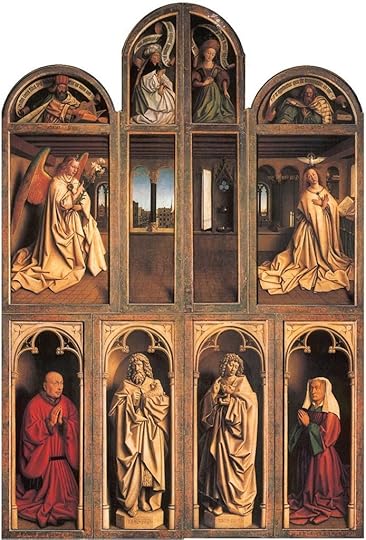

1.1. The Ghent AltarpieceThe Altarpiece, also known as the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, is a one-of-its-kind polyptych from the XV Century: it was painted by no others than Hubert and Jan van Eyck, though this attribution has been disputed, it’s considered one of the world’s treasures and, according to some scholars, it marked the transition from Middle Age to Renaissance art. It’s often defined as the first major oil painting.

A polished overview of the opened polyptych.

A polished overview of the opened polyptych.The piece is organized in three portions, with foldable wings and a central part, and it was opened only on special occasions, so it’s perfectly preserved.

On the inside, the upper part shows us a figure of God, enthroned and with an iconography reminding us of the Pope in a traditional tarot deck. On his right, the Virgin Mary is shown reading a book. On his left, a heavily bearded St. John the Baptist only pretends to read and raises a hand in warning.

Inside the wings, angels playing music are shown on the right portion, and wingless angels sing on the left. The figure of a pregnant Eve counterpoints the Virgin Mary, while Adam covering himself with a fig leaf is on the outer portion opposite St. John.

The lower portion gives the name to the polyptych: people from all trades are shown gathering in adoration of the mystic lamb, standing on an altar while the Holy Spirit, symbolised by a dove, overlooks the whole composition. We can distinguish knights and merchants, literates and the clergy, hermits and monks. Specifically, from left to right:

the first panel from the left is dubbed “the just judges“, representing power and fairness embodied by the Christian virtue of justice: this piece is not original, as it was stolen in 1934 and repainted five years later by one Jef Van der Veken;the second panel from the left is the “soldiers of Christ“: at the back of the group, behind the colourful banners, we can see crowned princes participating in the worship of the lamb;the first panel from the right is the hermits;the second panel from the right is the pilgrims, led by their protector, Saint Christopher.The city is represented in the background, grounding the composition to its time and place.

The closed altarpiece.

The closed altarpiece.On the back, on the portions meant to be seen for most of the time when the altarpiece is closed, the upper part depicts an Annunciation scene, with the archangel Gabriel on the left holding the lily and the Virgin Mary on the right, her hands crossed and the book of prayers in front of her, with again the Holy Spirit represented as a dove. The interiors are extremely interesting and many have attempted to place the street depicted outside the window, without any success. Maria answers through an upside down inscription, thus arranged so it can be read from Heaven.

Four prophets are represented in the crescents above: Zechariah is above Gabriel, with a quote from his own book saying “Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion … behold, your king comes”, while Micah is above the Virgin and I can’t read his quote. The Erythraean Sibyl is depicted on the left, and the Cumaean Sibyl on the right.

The lower portion shows us the two patrons who commissioned the work: Joos Vyd and his wife Elisabeth Borluut. Joos was a member of the city council, and Elisabeth came from one of the most influential families in Ghent.

The two central paintings in grisaille, giving the illusion of painted statues, are John the Baptist, again represented as a bearded old man, and St John the Evangelist holding the traditional cup with a little dragon taking a bath in it. You might remember we saw something similar painted by El Greco.

.

.

.

I have a weakness for grisalles, a particular style of painting in shades of grey (no reference to the appalling soft-porn pseudo-fanfiction), and the choir is decorated by a series of 11 such paintings done by Petrus Norbertus van Reysschoot (1738 – 1795) depicting five scenes from the Old Testament and six from the New. When seen from the side, they look like they’re in relief. They’re stunning.

Saint Bavo enters the Convent at Ghent, also known as The Conversion of Saint Bavo with reference to the moment the soldier encountered his future mentor Saint Amand, was painted by no other than Peter Paul Rubens in 1623 and it’s still in the Cathedral, though no one seems to be paying too much attention to it.

If you observe it and don’t think it’s particularly impressive, I suggest you take a closer look at the group of ladies on the left. That’s Rubens alright.

We were lucky enough to visit this 1180 castle while it was snowing outside, and it made for a truly magical experience.

The castle was built under the reign of Arnulf I (890–965), and it was the residence of the Counts of Flanders until 1353. Its interiors and courtyard are absolutely stunning, complemented by humorous modern banners which try to give you ideas as to what the differences rooms might have been dedicated to.

The halls host an impressive exposition of XV century weaponry, which is the fanciest and most inefficient of all times: powderkegs with ivory handles, carved guns that are most likely to blow up in your hands, heavy and unhandlable swords, crossbows that weigh a ton. You take your pick.

From the walkways you’ll have a stunning sight of Ghent, but beware the stairs in the towers: they’re so steep it is said the resident lord had impressive tights due to walking up and down the whole day. Other fancy stories include a room where people was left to choke themselves should they fall asleep, an underground jail with fishing rabbits, beheaded ladies, people whose thongue was pierced with hot nails, horses mourning their knights and other fun stuff.

December 6, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 7: Tudor Lovers’ knots

Beat the eggs together with the sugar, add the cinnamon and then flour, little by little, so the dough will not make lumps. When you’re done kneading, make long thin rolls 1 cm wide and 10 cm long, like you would do to make pretzels. Tie them into knots, and if you need inspiration, I suggest you take a look at recreations of Tudor’s gardens.

Picture taken from here.

Picture taken from here.After you’re done shaping your knots, simmer them in boiling water for a couple of minutes, minding that they float. If they stick to the pan, you’re screwed.

After 2 minutes, remove them with a flat strainer (I’m sure it’s not called that way), and leave them to drain either on a cloth or on some kitchen paper. Grease a baking tray with some butter, put the knots in the preheated oven and bake until they’re golden brown. It shouldn’t take more than 15 minutes.

While the knots are still hot, take the honey and brush them abundantly with it. Sprinkle with the seeds. To suit all your guests’ tastes, I suggest you divide the seeds and make some with sesame, some with poppy seeds, and some with caraway.

Here‘s a video, if you prefer them. Sometimes they’re also called Jumbles, and you see them referenced as such in this recipe.

That Sesame opening doorsWhile translating the 1001 Nights between 1704 and 1714, the French archaeologist and orientalist Antoine Galland took many liberties. One of them was introducing a tale not technically from the original collection, the famous tale of Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, which he had heard directly from the Syrian storyteller Hanna Diyab. The tale, as you might recall, features the famous magic formula “Open sesame!”, which became a way of speech. What you might not know, since very few people have actually read the story, is that Ali Baba’s brother forgets the formula and tries possibly any other seed known to men, staying entrapped in the treasure cave.

Why Sesame?There are many theories.

One of them comes from observation: the seeds of the sesame grow in containers or pods which spontaneously break open when they reach maturity, in their own little spectacular way: a good connection with the opening of a door to a treasure, don’t you think?

The reason might also be connected with the seed’s Indian origins and the custom of using it as a purifier and a symbol of immortality during funerary ceremonies and cleansing rites. During funerals in particular, after the body of the deceased has been cremated, the people attending the funeral bathe themselves in the nearby river and leave two handfuls of sesame seeds on the shore as a viaticum, a tribute that the dead can spend while journeying to the next life.

In the Brahma Purana, one of the eighteen major Hindu texts in the Sanskrit Language, it is said that the sesame was created when drops of sweat fell from the eyebrow of Vishnu and fell on earth. Yama, god of the dead, later blessed them and declared them a symbol of immortality. Amongst the domestic Vedic rituals listed in the Āçvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra, a funerary prayer is dedicated to the sesame and it goes like this:

Oh sesame,

consecrated to Soma,

created by the gods during the great sacrifice

and carried by them;

bring joy to the dead,

to every world,

and to ourselves.

During the expiation celebration in honour of Bhisma, a demigod hero of the epic Mahabharata, people make offerings to the gods consisting of water, sesame and rice. If one forgets to make this single offering, they lose all the good karma accumulated throughout the year.

So yeah, if you want Tudor Lovers’ Knots to ensure eternal life, go with sesame.

What about caraway?If sesame is all treasure and immortality, cumin was called karón by the Greeks, and it was a symbol of pettiness: if you wanted to say that someone was really, really greedy, you’d say he split a grain of caraway, and Dione Cassio tells us that the people nicknamed Anthony “cumin” because of his obsession to money.

For some reason, however, the same plant came to symbolise friendship: according to Plutarch, caraway came to be compared to salt, and salt was an important ingredient in welcoming friends to your house. You get distracted for a couple of centuries, and caraway becomes a charm to bind people to you and your house: in Bologna, people used to give caraway to pigeons so that they wouldn’t depart from the house (and why would one want that, really escapes me), and those friends who just wouldn’t leave are called “caraways”. In Piedmont, young girls used to sneak caraway into pastries for their fiancées, to ensure fielty. It wouldn’t work with me, since I hate the stuff.

During the Middle Ages it was also considered a medicine: Saint Hildegard of Bingen, the Sibyl of the Rhine, recommends it for people who have troubles breathing, to make cheese more digestible, and she gives us a recipe against nausea:

1 part of caraway, 1/3 part of black pepper, 1/4 part of anise seeds (which she calls pimpinella, but it’s the same thing), ground everything together. Take some grated bread, add most of the powder keeping a pinch for later, add one egg yolk, a little water to keep everything together, knead the dough and cook it either in the over or beneath the ashes.

Sprinkle on top of the warm bread the pinch of powder you kept before, and eat it against nausea.

The custom of adding caraway to wine comes from the Reinassance, and it was often employed with the same antiemetic usage Hildegard suggests, but it was enriched with another mystical property that might have been very popular in such a time: to protect against the bites of venomous animals. It’s only in Germany however that they took matters a bit too far and caraway is used to flavour a liquor called kümmel. It’s my nemesis.

In some parts of Central Europe, bread with cumin was also used to protect people from devils and witches when crossing a forest, in some parts of central Italy, but it only worked if you either made or bought the stuff: on thieves, it would have the opposite effect.

So yeah, for a Tudor Lovers’ Knot that will really knot your lover, go with caraway.

[image error] Franz Eugen Köhler (1897)What about poppy seeds?Well, poppy is a more complicated matter, and we will see it another time.

December 5, 2023

#AdventCalendar Day 6: Chestnuts and Pork Pie

This is one of my favourite recipes, though I very rarely get to cook it because boiled chestnuts aren’t that easy to find, and I have no patience for boiling chestnuts myself.

Ingredients (serves 6 people):For the filling:500 grams of large chestnuts;100 grams of ricotta (a soft cottage cheese will do);100 grams of grated pecorino cheese (according to this site, you can replace it with Spenwood);200 grams of pork meat;3 eggs;a glass of milk;a pinch of black pepper;a pinch of marjoram;a pinch of thyme;a pinch of salt.For the pastry:400 grams of flour;150 grams of butter;2 eggs;water;a pinch of salt. It’s going to be fine: if I can make it, you can make it.Recipe:For the pastry:

It’s going to be fine: if I can make it, you can make it.Recipe:For the pastry:Build a small volcano with the flour, break the eggs in the crater and work everything together with the salt. Pour water on it little by little until the dough is elastic and not too soft. It’s going to be sticky, so you need to dust your hands with more flour. Also, remember that the water needs to be cold and so do your hands, or else the eggs in the mixture start misbehaving and the dough — as we say in Italy — goes crazy.

Chop the butter into pieces and incorporate it in the mixture as well, work it into the dough until you no longer see the pieces but this requires for the mixture to warm a bit, so you’ll want to be quick about it. As soon as you’re satisfied, drop the dough in cellophane or in a cold cloth, and throw it into the fridge. Three hours is the optimum, but half an hour usually suffices.

Boil the chestnuts and peel them, if you’re brave, or buy them already boiled if you’re like me. Mash them with a potato masher or with a fork if you don’t have one, put the result into a bowl and mix it with the ricotta, the grated pecorino and the minced pork meat (yeah, I know, it’s raw: don’t worry). Work everything together with the eggs and the milk, sprinkle with pepper and herbs, and go take your dough out of the fridge.

Rub a pan with butter, split the dough in two and use the first half to line a baking pan. Pour the mixture in the dough, and then cover everything with the rest of it. You might want to pierce a some holes on the lid: there’ll be fat overflowing, and it’s better if you try to control it. If you want, you can also melt a curl of butter and use it to brush the surface of the dough.

The whole thing has to cook for around 50 minutes in a pre-heated oven that’s not too hot. Say 180°C.

What about chestnuts?Romans used to call chestnuts Jupiter’s acorns (Iovis glandes), possibly because the stern appearance of this tree made it suitable to be a “cosmic tree”, a tree connected with the great father. The actual name of the plant however has a geographical connotation, and it’s said to come from the city of Castanis, in Ponto, where the Greeks thought this plant came from. In truth, the plant originates from Iran.

The Greeks weren’t particularly fond of chestnuts: Plinius the Elder found it very strange that the plant took so much pain to protect with thorns a fruit that’s really not that appealing, but recognises that they’re not so bad if you roast them, so possibly his mistake was trying to eat them raw. He also writes about chestnut flour, and says that you can make bread out of it, for the women’s fasting period. I have no idea what the heck he’s talking about.

Romans however appreciated them more: both Columella and Apicio mention them in their recipes, and the latter suggests their use to replace lentils. Marziale lists roasted chestnuts when he talks about a banquet offered by his friend Toranio, and makes a point to state they came from Naples.

Bonvesin de la Riva writes about chestnuts around 1288, and suggests using them in legumes soup with fava beans, to temper their bitterness. He also says they’re better than dates and, as much as I might love chestnuts, I can’t help but wonder what he’s been drinking.

One of the most famous chestnut trees in the Middle Ages was set in Sicily, on the slopes of the Etna volcano, and it was called “the chestnut of the hundred horses” because Giovanna “Giovannella” d’Aragona, Queen of Naples, took refuge under its branches with her own retinue after being surprised by a storm while travelling. Pascoli dedicated a poem to this tree.

The main trunk burned down in 1923, but some parts of it are still visible and the four secondary trunks measure around 50 meters. Yes, I said meters.

This painting by Raphael is said to depict Giovanna.

This painting by Raphael is said to depict Giovanna.Throughout the Middle Ages, chestnuts have been considered food for the dead, possibly because of their nutritive and aesthetical similarities with fava beans and chickpeas which were already connected with the afterlife. They were food to be consumed during the Day of the Dead in both Venice and Piedmont, in the Valley of Aosta, in the Vienne region of France, and in some parts of Liguria.

In Ferrara, however, they had a different idea: during the feast of Saint Joseph, men gave their fiancées a romantic gift of hyacinth and a mistoca, a fritter made with chestnut flour which was a symbol for the end of winter.

It was only around the end of the XVI Century that roasted chestnuts became street food in Italy, as they still are today.

Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz (1885)

Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz (1885)