Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 8

November 19, 2014

Seattle ship swipes totem

Of the multitude of steamships that plied the waters from California to Point Barrow during the late 1800s, one has the dubious distinction of being what some may call a “pirate ship.”

Of the multitude of steamships that plied the waters from California to Point Barrow during the late 1800s, one has the dubious distinction of being what some may call a “pirate ship.”

The City of Seattle, which sailed from Seattle to Skagway and points in between at the turn-of-the-last century, played a major role in spiriting a totem pole out of Alaska.

As the story goes, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce had wanted a totem pole to erect in Pioneer Park in downtown Seattle. However, those who carved the magnificent monuments only came from the tribes of northern Vancouver Island, the Queen Charolette Islands, and the adjacent tribes in British Columbia and Alaska.

In the summer of 1899, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer put a delegation onboard the City of Seattle to sail to Sitka to see if they could find a totem pole suitable for the park. Since most of the totems by this time were stationed in Indian burial grounds, the delegation’s mission was indeed delicate.

After a brief stay in Alaska’s ancient capitol, guests returning to the ship were advised by the purser not to believe anything they heard and only half of what they saw from that time forth.

Then, after finishing her business in the port of Sitka, the City of Seattle sailed out a short distance and then anchored in a stream. Passengers watched as the crew lowered one of the ship’s boats into the water and rowed ashore. Later, third mate R.D. McGillvery described what happened:

“The Indians were all away fishing, except for one who stayed in his house and looked scared to death. We picked out the best looking totem pole. I took a couple of sailors ashore and we chopped it down – just like you’d chop down a tree. It was too big to roll down the beach, so we sawed it in two.”

Members of the “Committee of Fifteen” paid McGillvery $2.50 for his effort to cut down the totem, which belonged to the Raven Clan. It was carved in 1790 to honor a woman called Chief-of-all-Women who’d drowned in the Nass River.

On Oct. 18, 1899, the 60-foot totem was unveiled in Seattle’s Pioneer Square and “greeted by cheers of a multitude of people.”

The Tlingits demanded $20,000 for the return of the stolen totem, but settled for $500, which the Seattle Post-Intelligencer paid.

The original totem stood proudly in Pioneer Square until a careless smoker tossed a cigarette butt against its decaying base in 1938. The city removed the original totem and replaced it in 1940 with a replica carved by the descendants of the original totem’s carvers.

The post Seattle ship swipes totem appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 10, 2014

Ship Creek plateu becomes Anchorage

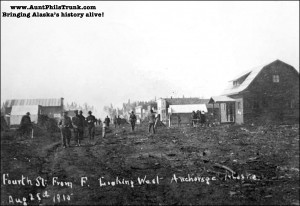

Fourth Avenue became the center for business in Anchorage because it sat along a flat plateau.

How did Fourth Avenue become the main street of Anchorage? Some say, “it just happened,” while others say look at its location in relation to the land disposition in 1915.

Many original lot owners lived in “Tent City” and had established businesses in their tents along Ship Creek. The area that was to become Fourth Avenue was the obvious choice for commercial establishments, because it was the closest land to the railroad terminal yards that offered many lots for sale on level ground. While First, Second and Third avenues were actually nearer to those yards, major portions already had been set aside for government purposes.

So Anchorage’s founding fathers designated a large portion of Fourth Avenue as the business district, while two blocks were withheld from public sale that constituted the Federal Reserve and the Municipal Reserve.

The lots then were surveyed and staked, providing for an 80-foot-wide street. According to an article in the Cook Inlet Pioneer, businessmen were encouraged “to visit the townsite and to go over the ground as thoroughly as possible so as to become informed” before the auction began.

When the bidding from the first auction ended, local merchants had paid more for lots along Fourth Avenue than anywhere else in town. The first bids on Fourth Avenue property averaged $548 per lot (almost $13,000 in today’s dollars), whereas the average price for other townsite lots ran about $225 ($5,300).

Corner lots along the center of the avenue, between C and F streets, sold for between $800-$1,000 ($19,000-$23,500), twice the appraised value. A headline in The Seward Weekly Gateway on July 10, 1915, proclaimed, “Highest Anchorage Lot Goes for $1,150.”

On July 17, 1915, the Cook Inlet Pioneer reported: “While perhaps local residents did not anticipate the fancy prices that were paid for lots, it is better that there should have been an eager demand than a lack of interest and consequent cheap prices. The one means faith and optimism and the other doubt and pessimism. And confidence is a large contributing factor that builds a center of population.”

Once lots had been purchased, merchants hurried to build along the new main street. Many businessmen had stockpiled construction supplies and had permanent commercial enterprises up and running in no time.

While some merchants hauled their tent-covered frames up to their lots, others built substantial structures like the Wendler and Lathrop buildings, Brown & Hawkins and the Carroll Building. Soon a bustling town grew up on the plateau and later became the largest city in Alaska.

The post Ship Creek plateu becomes Anchorage appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 4, 2014

New historical book just released!

Just in time for the holidays!

Aunt Phil’s Trunk Proudly Presents

The Spell of the Yukon and Other Verses

Although I still am working hard on Volume Five of my Aunt Phil’s Trunk Alaska history series (anticipating mid-2015 release), I also have been listening to Alaska history fans. Many of you have asked me how you can get your hands on a copy of The Spell of the Yukon by Robert W. Service, the Bard of the Yukon.

A thorough investigation revealed that his book, which originally debuted in 1907, now is out of copyright and in the public domain.

So, just in time for the holidays, I have reproduced his entire first published collection of poems in Aunt Phil’s Trunk Proudly Presents The Spell of the Yukon and Other Verses. This specially created book also features a biography of the famous poet, complete with photographs.

Even though he never lived in Alaska, Service helped put it on the map for most people with ballads like “The Shooting of Dan McGrew,” “The Cremation of Sam McGee” and “The Call of the Wild” – all included in this just-released, limited edition, collection of poetry.

Aunt Phil’s Trunk Proudly Presents The Spell of the Yukon and Other Verses will not be sold in stores. So click here to order your copy before the supply of this limited edition tribute to Robert W. Service is gone!

$14.95 (plus shipping)

The post New historical book just released! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

October 27, 2014

Dawson dancehall girls mine the prospectors

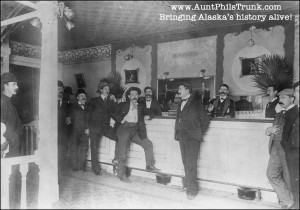

Prospectors wait at Dawson’s Savoy Bar for dancehall girls to come their way.

During the Klondike Gold Rush, Dawson’s dancehall girls offered prospectors a welcome diversion from their grueling, lonely days of digging in the sub-arctic tundra.

“The sourdoughs lay on their bunks until noon – and noon might just as well be any other time – moving painfully about only to stoke the stove or break off a chunk of rye bread, more from sheer boredom than hunger,” wrote Ellis Lucia about digging for gold during a winter in the north country in Klondike Kate: The Life of the Queen of the Klondike.

“Many were ill with dysentery and scurvy, and worst of all, the sickening depression of futility. At times the men entered into the awful bleakness to claw at the frozen ground of their claims. They returned to the drafty warmth of their cabins, holding stiffened fingers above the stove, to ask themselves aloud just why they were trapped here in this Godforsaken wilderness….

“Half-crazed with cabin fever, the sourdoughs could stand it no longer. Climbing into bulky mackinaws, mukluks and fur caps, they stuffed fat buckskin pokes into their coats and headed for Dawson City…. It was a gay, frolicsome world, filled with fun in contrast with the awful silence of the outer wilderness….

“Thousands in yellow gold changed hands in the gambling halls, to be lost and won again, and then to be lost once more to a pretty bit of fluff who called you honey, gave you a nice smile and a peck on the cheek, and would be your very own for the evening if you kept the champagne flowing her way. But you didn’t mind, for there was plenty more of this yellow stuff where that came from,” Lucia wrote.

The technique used by most dancehall girls to separate the gold miners from their wealth included getting the prospectors drunk in private boxes that surrounded dance floors in saloons. In her book Good Time Girls, Lael Morgan shares a detailed account of the separation process written by La Belle Brooks-Vincent:

“She is all nerve as she enters a room and surveys the waiting crowd…. The dancehall girl is industrious. She is never vacillating or undecided; she is persevering. She does not flit about the room bestowing a smile here, a caress there and again a pouting neglect. When she selects her victim she stays with him. The more marked her favor, the greater his triumph…. He needs her to complete a spectacle of himself as a favored beau….”

Most of the “victims” were willing single men who prospected alone and didn’t have women waiting for them back home. And they enjoyed the company of the dancehall girls, many of whom eventually ended up as wealthy as some of the miners themselves.

“The poor ginks just gotta spend it,” said Diamond Tooth Gertie Lovejoy, one of Dawson’s most famous dancehall girls. “They’re scared they’ll die before they get it out of the ground.”

The post Dawson dancehall girls mine the prospectors appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

October 21, 2014

Hudson’s Bay Company in Ft. Yukon 1846

This replica shows what the original Hudson’s Bay Co. post, established at Fort Yukon in 1846, looked like.

Fort Yukon, which can be reached by air from Fairbanks, was described by famous columnist Ernie Pyle as being “a half mile from the ends of the earth.” Its story is a page out of Alaska’s history.

John Bell, an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Co., reached the Yukon by way of the Porcupine River in 1846. A year later, Alexander Murray, another Hudson’s Bay man, started a new post about three miles upstream from the mouth of the Porcupine, well beyond the Arctic Circle.

The post was far inside Russian America. It was the most far-flung of their great chain of posts that stretched across the continent. It was so isolated that when the commander shipped a cargo of furs to London, reports were not received until seven years later.

In order to withstand Russian attack, Murray built the fort especially strong. As he wrote in his journal:

“We live on good terms with the Natives and fear nothing except to see two boatloads of Russians heave around the point.”

The Hudson’s Bay people held down their lonely outpost for 22 years. They were finally forced to move out, not by the Russians, but by the Americans after the United States purchased the vast land.

When Capt. Charles Raymond of the U.S. Army and his men jumped ashore from the first steamboat to ascend the Yukon that far, they were met by all of Fort Yukon’s inhabitants and treated with great hospitality.

On Aug. 9, 1869, the Union Jack came down and the Stars and Stripes were hoisted over the first English-speaking settlement on the river. The Canadians withdrew peaceably up the Porcupine River to a spot they thought was in Canada. However, they had to make two more moves before they finally got out of America.

The original post is gone – engulfed by the voracious Yukon River that is constantly gnawing away at the river’s banks.

However, the present Northern Commercial store is its direct descendent. Fur remained a medium of exchange, just as it was in the Hudson’s Bay days, for Fort Yukon always has been considered the “fur mother lode” of the North.Trappers from outlying settlements on the Porcupine, Chandalar, Big and Little Black and the Christian rivers brought their furs to the outpost. And although the decline in fur prices cut down on trappers’ income, there still may be strings of glossy pelts hanging cheek by jowl with modern electric stoves and washing machines in “The Store.”

The post Hudson’s Bay Company in Ft. Yukon 1846 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

October 15, 2014

Richest Native woman in the north!

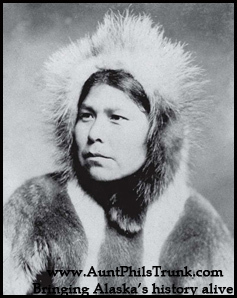

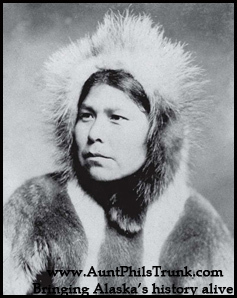

Mary Makrikoff, also known as Reindeer Mary, became the first Alaska Native woman to own a reindeer herd.

A baby girl born in 1865 would become the richest Native woman in the North and grow famous for her reindeer herd. Born to an Inupiaq Eskimo mother and a Russian trader father, Mary Makrikoff grew up in St. Michael on the southern shore of Alaska’s Norton Sound. Her mother called her Changunak.

Mary grew up speaking fluent Russian, English and Inupiaq. Her skills with these languages made her an invaluable resource for ship captains and government officials who traveled to her village.

In 1889 she met and married Charlie Antisarlook. The couple moved to Nome, which Mary found quite different from St. Michael. Later in life she said, “There were no people there (in Nome). Not any groceries, either. Their food wasn’t like what the Eskimos of St. Michael work hard to have.”

Her new life in Nome meant she had to learn how to live on “real simple food, like whale meat, seal oil, rabbits, and ptarmigan.” But the determined young woman did learn the subsistence ways and her family thrived.

Mary Makrikoff, also known as Reindeer Mary, became the first Alaska Native woman to own a reindeer herd.

Mary and Charlie lived in a settlement outside of Nome called Sinrock, where they helped the U.S. government with its reindeer herds. Years later, she and her husband became the first Natives to be given their own herd, numbering 500.

Charlie died during a measles epidemic in 1900. After his death, Mary fought hard to keep her reindeer. Because she was a Native woman, her brothers-in-law asserted that she couldn’t own property. But after a lengthy legal battle, she eventually won the right to keep her herd and became known as Reindeer Mary, as well as Sinrock Mary.

However, her good fortune brought problems. Gold rush prospectors started courting her, offering her money, liquor and even marriage so they could gain control of her herd. She finally got fed up with their uninvited attentions and left Nome.

Mary and her herd moved to Unalakleet. Over the years she increased her herd to 1,500 and sold reindeer meat to the U.S. Army, stores in St. Michael and to the miners. She eventually married Andrew Andrewuk, who had no interest in reindeer herding.

Mary never had any offspring of her own, but she did adopt 11 children. She taught them, as well as Inupiat men, to care for reindeer. And many of her children grew up to have herds of their own.When “Reindeer Mary” died in 1948, she left a legacy of compassion and generosity. People still tell stories about how she shared her wealth in the Eskimo way.

The post Richest Native woman in the north! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

October 6, 2014

Alaska’s first law officer

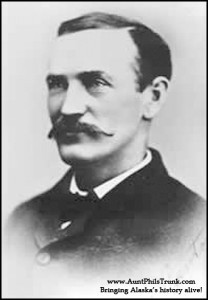

Frank Canton had a shady past when he hired on as a U.S. deputy marshal in Circle.

Alaska’s first law officer in the Interior knew a thing or two about the criminal element. Frank Canton, appointed deputy marshal for Circle in February 1898, had served with distinction as a peace officer in Wyoming and Oklahoma Territory. He’d also escaped from prison while serving time for bank robbery, murder and holding up a stagecoach in Texas.

The sketchy lawman’s reputation as a range detective in Wyoming, notably as a killer for ambushing rustlers, secured his appointment in Alaska because he’d come to the attention of one very influential man.

P.B. Weare, a leading shareholder of the North American Transportation and Trading Co., which was challenging the monopoly of the Alaska Commercial Co., felt his business needed the protection of a vigorous law enforcement officer. Weare agreed to supplement Canton’s $750 yearly salary (around $18,000 in today’s dollars).

On his way to his new post, weather forced Canton to spend the winter in Rampart in 1898. He tried his hand at prospecting but put his peace officer hat back on in April after passengers on board a steamboat wintering near Rampart mutinied against their captain. They announced their intention to take the boat to Dawson as soon as the waterway opened.

After a two-day hike, Canton reached the vessel and arrested the leaders of the conspiracy. He then convened a meeting of the other passengers, and as judge, held a trial and fined the perpetrators $2,000.

When one of the takeover leaders attempted to kill him, Canton recognized him as a fugitive from Idaho with a $2,500 reward on his head (about $50,000 in today’s dollars). Canton arrested him, and as soon as the ice went out on the Yukon River, he hauled the fellow to Circle.

By the time he reached his new post, Canton found that most of the miners had moved on to Dawson. Their exodus meant that city coffers were limited, so the lawman had no funds with which to operate. He also found that no one in the community wanted to board federal prisoners for $3 a day, nor act as jailers.

Canton had to borrow money from the Northwest Trading Co. to meet the obligations of his office. Shortly thereafter, he wrote to U.S. Marshal James Shoup in Sitka requesting money to meet daily expenses and to construct a jail.

Before he heard back from Shoup, he had several more suspects accused of robbery and attempted murder in custody. The small U. S. Army garrison at Circle helped him guard his prisoners while he awaited funds.

To his dismay, the reply he received in March 1899 didn’t include money for running the marshal’s office nor any reimbursement for out-of-pocket expenses. Canton wrote an angry letter back to the U.S. Marshal.

“I need some money very bad and wish you would send in some funds at once,” he ranted. By that time, Canton had eight prisoners he intended to take to Sitka for trial.

Canton never did receive any funds from Shoup. Instead, he was discharged as a deputy marshal when officials learned he had resigned his Oklahoma position while being audited for fraudulent expense claims. The Justice Department hadn’t been aware that Canton had been appointed a deputy marshal in Alaska until late 1898.

The post Alaska’s first law officer appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

September 29, 2014

Toll road to the Klondike

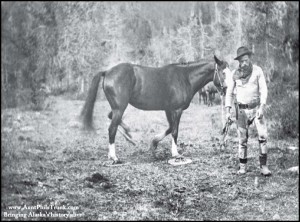

Jack Dalton leads his horse along his successful toll road trail during the late 1890s. Note: The horse is wearing snowshoes!

The short, feisty frontiersman held a rifle on the party trying to travel over his Yukon trail without paying the toll. Jack Dalton meant business, and people found he was a tough man with whom to deal. Dalton watched the group with their herd of cattle floundering through scrub trees and bushes and kept alongside for 300 miles to make sure they didn’t set foot on his right of way.

The Dalton trail opened a route in the 1890s from Pyramid Harbor on the Lynn Canal in Southeastern Alaska to the Yukon. It served a very useful purpose in the gold rush days. About 2,000 beef cattle successfully traveled it – a welcome addition to the miners’ food supply.

In later years, the trail would become part of the Haines Highway. As one rides the road in relative comfort nowadays, one can hardly realize how the pioneers traveled in toil and sweat – saddle sore horses and foot sore men made the 300-mile trek.

Dalton headed to Alaska via a sailing ship in the early 1880s, after some shooting scrapes in Oregon made it expedient to leave that part of the country. It is reported that in 1884 he and other members of the crew spent a year in the Sitka jail for seal poaching. Another source said his ship wintered at Hershel Island in 1885.

He left the sea in 1886 and became a member of Schwatka’s exploration party to Mount Saint Elias. Later he signed up with the Leslie party to explore the Interior and write reports for the Frank Leslie Illustrated Newspaper of New York.

On their first trip they’d started in the Interior and descended the turbulent Alsek River to the sea. Next time they started from the Chilkat village of Klukwan on the coast, this time using horses, and made it to Lake Kluane in Canada.

In 1896, Dalton established a pack trail to the Yukon, partly following the route he and the Leslie party had followed earlier. The Klondike gold rush would find him prepared, and the Dalton Trail became an important gateway to the gold fields.

According to historian and author Pierre Burton, Dalton was a respected figure in Dawson. Others had tried to establish a toll road, but Dalton was the only one to make it stick.

Little did Dalton know that 70-some years later another road also would bear the Dalton name. The North Slope Haul Road, or Dalton Highway, was named for his son, James Dalton.

The post Toll road to the Klondike appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

September 23, 2014

Eskimo Scouts Guard Alaska

Alaska Natives, like Henry Lockwood and his family from Unalakleet, eagerly volunteered to serve in the Alaska Territorial Guard during World War II. Mrs. Lockwood handmade the American flag they are displaying in this photo.

When the U.S. Government needed them, Alaska’s Native population came out in droves. From the beaches of Bristol Bay to the far corners of Bethel, Kotzebue and Barrow, villagers didn’t hesitate to provide Alaska with a line of defense after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

Col. Marvin “Muktuk” Marston, who’d been put in charge of organizing the Alaska Territorial Guard, traveled along 5,200 miles of western Alaska coastline to personally address the Natives, including a stop in the Norton Sound village of King Island:

“Men and women of King Island, I am here representing the President of the United States and the Governor of Alaska (Ernest Gruening). You know that we are at war with the Japanese.

“I have been to Kuskokwim, Point Barrow and up to Kobuk and the Noatak rivers to visit all of you. I have seen more Eskimos than any Eskimo, and everywhere I find them to be fine people and fine Americans. They are helping in this war 100 percent.

“We need you to be the eyes and ears of the Army. You know how to hunt the seal and the walrus. You’re fine shots. I want every man who is willing to join the Alaska Territorial Guard.”

As Marston and Capt. Carl Scheibner traveled by dog sled with an interpreter along the coast and into the Interior, they recruited and organized the homeland defense. Approximately 6,000 Natives were asked to join the Guard, and although there was no money to pay the force and little equipment available, 100 percent enlisted.

These were the original “Eskimo Scouts.”

The Scouts were accomplished shooters. And even though the government could only issue them outdated Enfield rifles, they made every shot count.

In his book “Men of the Tundra,” Marston recounts a ceremony that lasted hours because all 3,000 in attendance received medals for “expert marksman.”

The Inupiat and the Yup’ik learned the art of military reconnaissance along the shores of the Bering Sea. Young men and women routinely patrolled the coastline, keeping a sharp eye out for intruders in a war that would eventually reach Alaska by way of the Aleutians.

Alaska disbanded the Territorial Guard in 1947, with no fanfare for the volunteers who proudly wore World War I-era uniforms bearing a blue patch with the stars of the Big Dipper.

It wasn’t until 2004 that the Alaska unit was officially recognized as military veterans. The U.S. Army finally granted formal military discharge certificates to former members of the Guard, which now only numbers a few. And those who qualify also can receive a headstone, a U.S. flag and burial in a national cemetery.

The post Eskimo Scouts Guard Alaska appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

September 16, 2014

Alaska’s 1st Sourdough Governor

John Weir Troy, left, was Alaska’s first sourdough governor and served the territory from 1933 to 1939, until ill health forced him to leave office.

Alaska’s governor from 1933 to 1939 believed the vast northern territory should become a state. And John Weir Troy, who came to Alaska during the gold rush in 1897, thought a larger population and a better road system would help achieve that goal.

“More people for Alaska is her greatest need,” said the former pack-train worker. “But they won’t come and we could not take care of them if they did until we have roads to take them to the valleys, hills and mountains where gold is locked in.

“…People coming to Alaska to farm or to prospect for gold and find employment in public works would furnish population that would make markets for agricultural products, timber, and other of the vast resources of the territory.

“The success being worked out through the Matanuska Colonization Project has added a promising outlook for the Territory. Not only has it added to the population in the vicinity of the Matanuska Valley and along the Alaska Railroad, but it has caused the people in other districts to become agricultural minded … I believe that agricultural colonization should be carried further with the establishment of more colonies in other parts of Alaska,” he said.

Had Troy not been forced to leave his position as the territory’s governor because of illness, more colonization projects might have dotted Alaska’s landscape during the 1940s.

When Troy was appointed governor in 1933, Alaskans heaved a collective sigh of relief. Troy knew Alaska and knew what to do to make it stronger. He’d mined, mushed, trapped and fished with the masses. He’d been rich and poor, and he’d lived through hardships and knew about luxury. Governor “Johnny” was a true Alaskan through and through.

Born in Dungeness, Wash., Troy worked as an apprentice at his uncle’s paper in Port Townsend following graduation from high school. He learned about type, galleys, picas and presses. But when he heard the tales of nuggets lining the ground in Alaska, the then 24-year-old set sail for Skagway on a boat carrying “other mules and some horses.”

He didn’t find nuggets, but instead found work hauling gold seekers from Skagway over the mountains and waterways into Whitehorse, where they then floated down the Yukon River to Dawson.

After the gold fever subsided, he became editor of the Skagway Daily Alaskan. When it folded, he moved to Juneau and became editor of the Daily Alaska Empire, which he soon purchased and ran for 27 years.

Old-timers considered Troy a real sourdough, a pioneer who toted his bit of sourdough from camp to camp to “start” his bread and flapjacks. And they believed in his vision that a large, permanent population would help Alaska become a state instead of just a territory of Uncle Sam’s.

The post Alaska’s 1st Sourdough Governor appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.