Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 6

April 8, 2015

Baseball in the Arctic 1894

Alaskans play baseball in all seasons, as seen by this photograph taken in the 1960s during winter. Snowshoes pose an extra challenge.

As the days get longer and winter begins to wane, the boys of summer are gearing up for another awesome season of baseball – a mainstay in Alaska for generations. Before Anchorage had plotted out its main street on Fourth Avenue in 1915, baseball teams faced off near the mud flats to put bats to balls that Fourth of July.

Following statehood in 1959, Alaska attracted a multitude of collegiate players who played for teams like the Anchorage Bucs, Alaska Glacier Pilots, Peninsula Oilers and the Mat-Su Miners. Many went on to play for the majors, including homerun king Mark McGwire, fantastic pitcher Randy Johnson and Hall of Famer Tom Seaver.

But the earliest reference to a baseball game in the north comes from the arctic region in March 1894, according to research by Alaska historian Stephen Haycox.

Funston first came into Alaska via the Chilkoot Pass, later made famous by the Klondikers, in April 1893. He then wind-sailed across the upper Yukon lakes of Lindeman, Bennett, Marsh and LeBarge and then shot Miles Canyon and Whitehorse Rapids, according to Haycox.

He spent the summer of 1893 working for the Department of Agriculture, collecting botanical specimens in the Canadian Yukon and near Fort Yukon in Alaska. Funston did not want to hang around the trading post when winter set in, so he joined some Canadian Indians and traveled up the Porcupine River to Rampart House and then over the Canadian divide to Fort McPherson, a Hudson’s Bay Company post on the Peel River.

“Although the trip over the Chilkoot Pass had been strenuous, Funston’s trek over the Richardson Mountains to the Peel River was a veritable arctic survival test,” Haycox wrote in an article titled, “Baseball on arctic ice,” which appeared in The Anchorage Times on July 29, 1984.

When Funston learned that ice floes had crushed seven ships of the Pacific Steam Whaling Company’s arctic fleet, he set out on another trek 175 miles north from Rampart House to see if he could help out. He found the reports exaggerated, however, as he found the ships were frozen in but had not been destroyed. What Funston did find on that chilly March day in 1894, though, were two teams from the stranded ships playing a heated game of baseball.

Finding that his services were not needed, Funston returned to Fort Yukon. He then traveled on to St. Michael, where he hopped on a steamer bound for San Francisco to report to his superiors.

They were pleased with his report about resources in Alaska, and stunned at the extent of his travels in the arctic. But they had one criticism of his northern adventure.

He had forgotten to record the score of the baseball game!

The post Baseball in the Arctic 1894 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

March 24, 2015

Great Alaska Earthquake

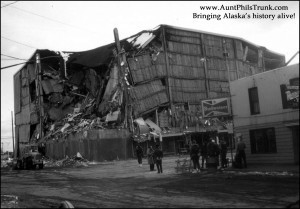

Two people were crushed when two concrete panels fell off the year-old J.C. Penny building in downtown Anchorage during the violent earthquake that hit Southcentral Alaska at 5:36 p.m. on Good Friday, March 27, 1964.

The second-largest earthquake in recorded history struck at 5:36 p.m. Anchorage time. Measuring 8.4 on the Richter scale – experts later upgraded it to 9.2 on the Mw (moment magnitude) scale as the Richter scale was determined to be inaccurate at measuring earthquakes above 8.0. Many Alaskans later said they lived through hell on earth during those 4 minutes and 38 seconds of violent shaking and the tsunamis that followed.

The temblor’s epicenter was located about 75 miles southeast of Anchorage, 54 miles west of Valdez and 15 miles beneath the tranquil waters of Prince William Sound. Centuries of pressure and strain finally broke loose when the crust of the Pacific Plate moved an estimated 25 to 30 feet northward, driving beneath the North American Plate with such force it released 200,000 megatons of energy in an instant – more energy than 10 million Hiroshima-vintage atomic bombs, according to experts.

The effects were felt around the world – even in Chile, where the largest quake ever recorded at 9.5 hit on May 22, 1960. While 114 people died in Alaska, another 12 were killed in Crescent City, California, and four children camping on Beverly Beach State Park in Oregon lost their lives when tsunamis hit the Pacific Coast. Tsunami, an adapted Japanese word meaning “port wave,” refers to the fact that the wave’s danger and destructive power only becomes evident as it approaches the shore.

The tsunamis also damaged boats in Los Angeles and Hawaii. Tide gauges in Freeport, Texas, recorded waves similar to seismic waves. And surfers at Collaroy Beach in Sydney, Australia, reported their usually gentle and small waves peaked violently at more than 20 feet on Easter Sunday.

Entire towns across Southcentral Alaska crumbled, streets buckled and cars, stores and homes dropped into wide crevices that split across the ground. This earthquake altered more of the Earth’s crust than any other earthquake on record, according to U.S. Geological Survey reports.

Uninhabited Montague Island, near the quake’s epicenter, raised the land as much as 33 feet. It lowered the ocean floor up to 150 feet under the devastated harbors of Seward and Valdez. The shoreline in parts of the Kenai Peninsula lifted 8 feet. Kodiak Island dropped 5.5 feet. And Anchorage shifted laterally 6 feet.

The Good Friday earthquake, which disrupted 185,000 square miles – larger than California – was the first “properly interpreted” megathrust quake, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Megathrust quakes occur in subduction zones, where tectonic plates converge. When forces build up and those plates slip, the results can be catastrophic, as in Alaska.

The military and Alaska Communication System labored all night to restore phone lines to the Lower 48, and local radio stations moved swiftly to get back on the air so people with transistor radios could keep abreast of vital news. The American Red Cross and The Salvation Army jumped into high gear, as well.

Soon more than 800 U.S. Army troops guarded devastated areas, provided medical support, and assisted Corps of Engineers crews in clearing slides and opening roads and railroad tracks. The U.S. Air Force immediately donated food, medical and other supplies for Alaska residents. And the Alaskan Air Command quickly moved hundreds of thousands of pounds of cargo throughout stricken areas.

The grim news reached the LBJ Ranch in Texas, where President Lyndon B. Johnson was spending the Easter weekend. Advisors woke the president twice during the night to give him updates on the devastation, according to newspaper articles. In the morning, Johnson officially declared the 49th state a disaster area.

One Anchorage policeman said it was worse than a disaster. After assisting with emergency services for 24 hours, he told a Newsweek reporter “it was hell.”

The post Great Alaska Earthquake appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

March 17, 2015

Radios: Early Alaska Lifelines

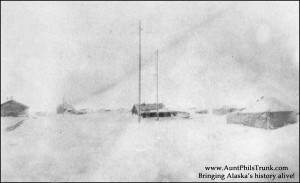

Alaska Communication System radiophone stations and antenna poles dotted remote Alaska villages and were lifelines to the outside world, as in Barrow seen here.

Before the Internet and cell service became synonymous with instant communication, Alaska’s remote villages relied on a military network of telephone-telegraph radiophone stations to relay messages. Only a few cables reached a few Alaska cities back in the mid-1900s, so messages from these Alaska Communication System stations were transmitted to and from these radiophone stations scattered all over the territory. With no roads and no other forms of communication, these radiophones were the lifeline for bush Alaska.

Every bush community had many antenna poles sticking high into the air, and often more than one battery-operated radio set in several homes. Radio waves hummed every evening as interested listeners tuned in their sets on every schedule, which they knew by heart, according to an article in the Alaska Call in September 1959.

The health of those living in remote regions of the territory often depended on messages sent and received by the dedicated radiophone operators to doctors and hospitals, which were few and far between. In fact, only two doctors and one dentist, in Bethel and Dillingham, practiced in the 1,000 miles between Nome and Adak on the Aleutian Chain.

The Alaska Native Service Hospital in Anchorage had its radiophones on a daily schedule. Every day the call went out: “This is ANS Hospital, and the doctor is ready for the traffic.”

The doctor then called each station on the network, listened to reports about old and new patients, tried to diagnose issues and gave medical advice. He then signed off until the next day.

This radiophone system not only was a critical link in providing medical advice from doctors, but it also was instrumental in saving lives when emergencies arose.

A teacher in one remote coastal town recalled just such an event for the Alaska Call, when he and a villager attempted to get medical help for a man with a broken his leg late one night.

“This is an emergency message. A man with a broken leg needs immediate aid. Notify the 10th Rescue Squadron for help,” they called out.

They did not receive any calls back, so they kept up their shout-outs well into the early hours of the morning. Just as they were thinking that their radio was not working properly, they heard a knock on the schoolhouse door and another villager entered.

“They heard your message. Iliamna and other stations repeated it also,” he told the schoolteacher, adding that a rescue plane was coming.

When the plane had not arrived by noon the next day, the teacher was about to send out a message when he heard an announcement.

“This is the 10th Rescue Squadron plane. We are coming in but will be unable to land. A helicopter is following us. Tell us if the man still needs help.”

The pilot then instructed the teacher how to let the helicopter crew know if the injured man still needed assistance.

“Get some people to form a cross on the beach if no help is needed, or form a circle if help is still needed,” the pilot said.

The plane then swooshed over the beach, and when the pilot saw the people standing in a circle, he flew in lower and dropped a message with instructions on how to prepare the injured man for a helicopter pickup.

Soon a chopper sat down on the beach. The villagers carried the man on a stretcher to the beach, where he was attached to the side of the helicopter and taken to the hospital.

The days of the radiophone may be gone now, but they have not faded from the memories of many rural Alaskans.

The post Radios: Early Alaska Lifelines appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

March 12, 2015

How Did Seward Get Its Name?

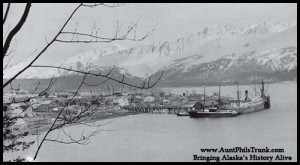

Seward’s deepwater port in Resurrection Bay, seen here around 1908, made it an ideal spot for a railroad terminus.

In March, Alaska celebrates Seward’s Day in honor of the man who succeeded in persuading the United States to buy Alaska from the Russians. And there are many landmarks named after President Lincoln’s Secretary of State. However, when Seward was chosen for the name of the town on Resurrection Bay, it took the personal intervention of President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt to make it possible.

By 1902, John Ballaine, originator and promoter of the Alaska Central Railway and founder of Seward, had selected the spot to be the tentative ocean terminus of the railroad he planned to build. His engineer, C.M. Anderson, had designated the place “Vituska” on the blue prints – a combination of Bering’s first name, Vitus, and the last syllable of Alaska.

But since Ballaine was convinced this new site would one day be the metropolis of a great territory, he wanted it to bear the name of the man who foresaw the primacy of the Pacific Ocean in the world’s future.

In March 1903, he bestowed upon the new town the name of Seward. Ballaine wrote Frederick Seward that he’d chosen his father’s name and received the following reply from Seward’s son on April 6:

“I need hardly say that the selection of the name seems to me an appropriate one and that it will be gratifying to those who knew him in life and the still greater number who hold his name in esteem and loving remembrance. Time has now shown that his prediction in regard to the future of Alaska was not at all exaggerated.”

However, the postal inspector of the district filed a protest, arguing that there were already several places named Seward in the territory.

Ballaine personally went to President Roosevelt and explained his reason for wanting to call the new place Seward. He pointed out that the other Sewards were canneries or temporary camps that could easily change their names.

Roosevelt agreed and asked Ballaine to write him a letter embodying the reasons given verbally and have it back to him by 10 a.m. the next day.

Later, Ballaine recalled what Roosevelt said upon receipt of the letter.

“‘You are quite right,’ Roosevelt said. ‘This railroad should give rise to an important city at the ocean terminus. The city deserves to be named in honor of the man who is responsible for making Alaska an American territory.’

“Thereupon, Roosevelt wrote on the margin of the letter a note addressed to Fourth Assistant Gen. Bristow, saying that he agreed with Ballaine, and signed it T.R.”

Ballaine had won his point and Seward was officially recognized. And although it did not become the metropolis as envisioned by Ballaine, its citizens overcame many disasters – fires, floods, earthquakes – to be named an All-American City three times by the National Chambers of Commerce. William H. Seward would be proud of his namesake.

The post appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

March 4, 2015

Anchorage: A Jewel on the Tundra

Anchorage was a bustling, growing city by 1951.

By the early 1950s, the tent city at the mouth of Ship Creek had turned into a bustling, modern city. Clifford Cernick wrote that Anchorage was much like Baghdad in an article that appeared in the Seattle Times on March 4, 1951 – a time when Baghdad was a bustling city, a jewel in the desert.

“A grizzled prospector, back in Anchorage after three years in the Alaskan wilderness, noted the towering framework of a new apartment building, the paved streets, the bustling downtown traffic and glistening shops.

“Nudging his companion, he declared: ‘Hey! Look what they’ve gone and done to Anchorage!’”

Cernick wrote that old-time prospectors, Natives from remote Bering Sea villages and the majority of tourists from the states all thought Anchorage was an amazing town.

“Mingled with the town’s frontier atmosphere is a new spirit of feverish construction and growth. It is a city reaching for the clouds, with one 14-story building planned and several others on the drawing boards,” Cernick wrote.

“The average Statesider’s conception of life in the ‘ice-locked land of glaciers, totem poles and Eskimos’ is shattered forever when he notes the city’s modern buildings, its three radio stations, three theaters, two newspapers and well-stocked shops.”

He added that the downtown area was a hub of activity.

“Along Fourth and Fifth avenues – the city’s main stems – frontier-type honky-tonks stand side by side with gay, sophisticated night clubs. Multi-colored neons splash glittering pools of color across the wide, paved streets at night.”

Cernick noted that women in fashionable mink coats were as much a part of the Anchorage landscape as Native maidens with moose-hide parkas. And that dogs and sleds didn’t warrant any more notice than panel delivery trucks. He said it was normal to see business executives and bank presidents sharing lunch counters with trappers and prospectors.

The reporter said the contrast and modern style of the town caused one airline pilot to make the observation that struck Cernick as fitting.

“An airline pilot, arriving over Anchorage at night after the long flight from Tokyo and seeing for the first time its pattern of flickering lights, winking like jewels in the midst of a vast, forbidding wilderness, described the city as a ‘Tundra Baghdad.’ In many respects, the name fits.

“Since the Second World War, the city has been charging ahead like a downriver steamer at full speed,” Cernick wrote. “In 1940, the census credited Anchorage with a population of 3,495. Today, the city proper has 11,060, and when suburban areas are counted, the total is close to 30,000.

“In the past few years, a city-wide swath of cleared land has been moving steadily southward. Hundreds of settlers have come and have constructed homes, roads and streets….”

But he also noted that all Alaskans were not too pleased with the evolution of Anchorage into such a going concern.

“An Alaskan old-timer named Russian ‘Jack’ is not too happy about what he calls ‘all this hustle and bustle.’ Gazing down traffic-choked Fourth Avenue, the city’s main thoroughfare, Jack remembers he ‘used to hunt moose there,’” Cernick wrote.

However, noted Cernick, the “city’s younger generation, unhampered by memories of the past, is looking to the promise-filled future – the not-too-distant time when Anchorage will rival many of the large cities in the States.”

The post Anchorage: A Jewel on the Tundra appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 23, 2015

First Miss Alaska Turns Heads

Helmar Liederman, originally from Sweden, became the first Miss Alaska in the early 1920s.

Dubbed The Arctic Venus by newspapers across the globe, Helmar Liederman turned many heads as she strutted her stuff in 1922 during the Inter-City Beauty Contest – forerunner of the Miss America Pageant. The 23-year-old beauty, who immigrated from Sweden in 1921, proved to be one of the most popular contestants of the 57 that entered the Atlantic City event. Only 10 girls had competed in the inaugural contest the previous year.

“A real beauty from the north country, Miss Helmar Liederman of Juneau, Alaska, is a striking type with luxurious brown hair and skin browned by constant exposure to the elements,” reported the papers. “An all-round lover of sports, Miss Alaska made the long trip from her native town by dog sled, hiking and automobiling to reach the famous seaside resort of Atlantic City, New Jersey.”

Atlantic City had initiated the beauty pageant in 1921 as a way to generate national publicity and put a new light on its tarnished image. During the 1920s the resort community was filled with gamblers, prostitutes and bootleggers – not to mention crooked cops and politicians who were happy to look the other way if the price was right.

Local newspapers sponsored various beauty pageants and used photos of the contestants to boost circulation. The news photo shown above featured Liederman, who had been sponsored by the Alaska Daily Empire in Juneau, wearing a white, tight-fitting one-piece bathing suit – a daring outfit for this era. Her tanned body and muscular physique gave her an “undercurrent of sexuality,” according to one magazine.

Liederman did not win the pageant that year, but she again entered the contest in 1923. Based on her reception the year before, the stunning beauty was filled with optimism that she would place well. However, a few days before the pageant, the Atlantic City Sunday Gazette reported that officials had banned her entrance into the pageant.

The newspaper reported that pageant director Harry L. Goshall had “raised the question that the fair entrant was married, that the Alaska newspaper had not been given authority to conduct a contest and had failed to ‘elicit information required to officially enter a contestant.’”

While Liederman was indeed married, there was no formal prohibition against matrimony anywhere in the official rules at that time. And she produced a letter of support from the Alaska newspaper. But the director’s disqualification stood.

It is interesting to note that Liederman actually lived in New York. How she got the Alaska Daily Empire to sponsor her is a mystery.

Journalist Frank Deford later wrote a book about the Miss America Pageant titled, There She Is: The Life and Times of Miss America (1971). He interviewed Godshall about those early days and Liederman.

“She had never seen Alaska,” Godshall asserted. “She was the wife of a fellow by the name of Earle Liederman, who was a physical culture expert looking for publicity. Where she got that letter from the Juneau newspaper, we never knew, but we were damned sure not going to Alaska to find out.”

Liederman later addressed the controversy about her Alaska ties in an article published in the New Zealand Truth.

“As for the charge that I am not a resident of Alaska, that is absurd. My brother is a hunter and trapper there; I have lived in Alaska for years and have become so acclimated that I have taken my daily plunge in the Copper River, with the Childs Glacier in front of me, and the temperature of the water thirty above.”

The post First Miss Alaska Turns Heads appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 16, 2015

Conman topples Alaska Governor

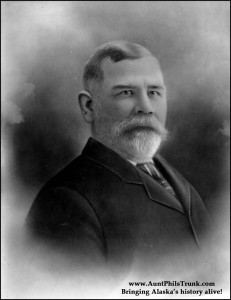

John Brady, who served as Alaska’s governor from 1897-1906, lost his job when he chose to believe that a conman was a good man.

Many have heard tales touting the shenanigans of conmen like Jefferson “Soapy” Smith and a man named Hendrickson, better known as the “Blue Parka Bandit.” But neither of them caused the demise of an Alaska governor’s political aspirations. That dubious honor falls upon H.D. “Harry” Reynolds, who singlehandedly brought down Gov. John Brady in 1906, according to a 1984 article written by Alaska historian Stephen Haycox for the Anchorage Daily Times.

Brady came to Alaska in 1878 as a protégé of missionary-educator Sheldon Jackson and helped establish the Sheldon Jackson College. He taught school in Sitka for several years and then opened a dry goods store. He later opened a freighting service and a sawmill and lumberyard.

It appears that Brady met Reynolds while in Sitka. He may have recognized Reynolds as a kindred spirit, an entrepreneur like himself who was making his way in the last frontier.

Sources say the two became good friends and that Reynolds may have invested in Brady’s sawmill business. So when Brady was appointed governor for Alaska in July 1897, just as the Klondike Gold Rush was beginning, Reynolds seized upon the opportunity to use the governor’s good name to convince people that he was an upstanding citizen and businessman.

Reynolds first appeared in Valdez in the early 1900s when folks were trying to pick the best route for a railroad to the Interior to carry valuable ore from the Kennecott mine. Reynolds convinced the people of Valdez that his Alaska Home Railway starting at their town was a better idea than the Morgan-Guggenheim Alaska Syndicate’s idea of building a line from either Cordova or Katalla.

“My railroad is your railroad,” he claimed.

Many Valdez residents believed in Reynold’s plan and invested their entire savings and businesses into supporting the Reynolds-Alaska Development Company. They may have felt secure in doing so, too, because Alaska Gov. John G. Brady was listed as one of the company’s five trustees.

Soon Reynolds had enough money to start his railroad. He also bought up much of the town and owned a newspaper, hotel, bank and some of the town’s streets. But when the powerful Alaska Syndicate chose Cordova as the terminus for its Copper River and Northwestern Railway, Reynolds skedaddled out of town in a hurry owing money to many of the fine folks of Valdez who now had no railroad and 500 unemployed workers.

This turn of events did not dampen Gov. Brady’s faith in Reynolds, however. Brady blamed the Guggenheim trust, believing it was a ruthless company that conspired against Valdez investors.

While the governor may have been blind to Reynold’s schemes, the higher-ups in Washington, D.C. were not, according to Haycox. Brady’s superiors warned him that Reynolds was up to no good. But the governor ignored their warnings.

A special investigator finally was assigned to check into Reynolds’ business dealings, and it didn’t take him long to discover that Reynolds was a fraud.

Brady’s steadfast support of his friend cost him his job. The Department of Interior called for his resignation in March 1906.

The post Conman topples Alaska Governor appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 7, 2015

Alaska’s archaeological sites explored

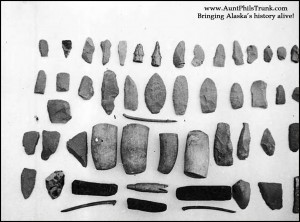

Archaeological teams dig up items like knives, scrapers, drills and points of stone and then radiocarbon date them to calculate the age of the items. This helps paint the picture of when humans arrived in an area.

Theories about how and when Alaska became inhabited with people ebb and flow like the state’s rivers. Archeologists pretty much agree that Alaska’s mainland was physically and ecologically a part of Asia 10,000 years ago, and that the Bering Strait was a grassy land area that separated the Bering Sea to the south and the Chukchi Sea to the north.

While the picture of who crossed the land bridge and when is still murky, the strongest hypothesis leans toward people crossing over from Asia in three waves.

Researchers say the first passed through Alaska and continued down to the New World. The second wave may have been what we know now as Athabaskans that settled the taiga areas. And the last wave were the ancestors of our Eskimo and Aleut people. However, other researchers think there were many waves made up of small groups of people.

An archeological crew surveying potential locations for new drill sites for Arco made a significant discovery in 1983 about 35 miles northwest of Prudhoe Bay. They noticed a collapsed “pingo,” which is a hill created by ice buildup, along the shore of a lake about eight miles south of Oliktok Point on the Beaufort Sea. They excavated about a foot below the sandy surface of what they learned was a fire pit. There they found burned caribou bones, tools and sophisticated weapons that radiocarbon dating showed to be 6,000 years old.

Radiocarbon dating measures the atomic half-life of biological materials, such as wood and bone, and is accurate within 5 percent. The dating on this discovery, while not the oldest site in Alaska, proved that nomadic hunters populated Alaska’s far north 4,000 years before Christ.

Side-notched spear points, worked-bone tools and end scrapers used for working hides also were unearthed. But one of the most exciting finds were fragments of a prized rock – moss agate. This type of rock originated in the Livengood area, which is about 360 miles south of the arctic coast, and indicates that people may have carried and traded raw materials for tools.

Older sites of human habitation have been found in Alaska. The oldest proven sites date back 11,000 years, including one at Onion Portage, located on the Kobuk River in the northwest. Tools excavated from this area are similar to those found in Siberia. Others on the Seward Peninsula and in Interior Alaska indicate humans were there as early as 15,000 years ago.

Archaeological evidence from a site near Nikolski, a settlement on the Aleutian Chain, dates back 8,500 years, according to the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association Website, and is the oldest continuously occupied community in the world. This area, which lies 116 air miles west of Unalaska, shows 4,000 years of continuous occupation at the Chaluka site. This means that people were there before Egyptians built their pyramids, the Mayans created their calendar and the Chinese developed written language!

The oldest human site found in North America lies just across the Alaska border in the Yukon Territory. It dates back 27,000 years.

The post Alaska’s archaeological sites explored appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 2, 2015

Gold rush entertainers dazzle Hollywood

Famed Hollywood actress Majorie Rambeau got her start in the entertainment business by performing on stage in Nome during the 1906 gold rush.

Although the frenzied gold seekers of the North lacked most of the luxuries, not to mention necessities, of civilized living, they did have theaters – even opera houses.

There had been entertainment in California’s gold rush of 1849, but never had there been such garish and colorful entertainers as in the days of ’98. And many of them went on to fame and fortune.

Sid Grauman, later owner of Hollywood’s Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and high priest of Hollywood’s cinematic palaces, started his career producing tent shows in Nome. Even before that he had been Dawson’s foremost newsboy, and he never became so lordly that he disowned his Klondike newsboy days. In fact, he credited them as giving him the ideal background for his later career.

Another future showman early discovered that a man would spend his last dollar to be amused. Alexander Pantages concluded that supplying amusement was sounder business than supplying supposedly primary needs. Like Grauman, he started in Dawson and ended up at Nome. His Pantages Orpheum provided the best show in town. After he returned to the states, he started acquiring film palaces and ended up selling his circuit for $24 million.

Most of the actors and actresses providing gold-rush entertainment were “waitresses, box hustlers, salesmen, tinhorn gamblers and the usual hangers-on of a mining camp,” sources report. A few, however, were professionals – and some went on to stardom.

Marjorie Rambeau, for instance, who later became one of Broadway’s leading beauties, was a child performer when she came North, traveling with her mother and missionary grandmother.

The mother took no chances with her little daughter and dressed her as a boy, and it was as a street urchin Rambeau made her debut. She was a great hit singing and playing a banjo at Tex Rickard’s famous Northern Saloon in Nome. Enchanted customers pelted her with gold nuggets.

In 1959, Rambeau told famous columnist Hedda Hopper about her early days performing and growing up in Alaska. She lived in a cabin with a sod roof, worked fur traps, ate seal meat and ran her own dog team.

She later traveled to Dawson and appeared in theaters there. Rambeau said she knew Robert Service. She also told Hopper that her manager ran off with the box office receipts and left the acting company stranded in the Yukon Territory.

Another small fry who later became famous was Hoagy Carmichael. He also entertained Tex Rickard’s customers in Nome. Only 8 years old, he was billed as the “boy wonder,” playing the piano in the Northern.

The entertainment business proved as profitable a gold mine as any of the rich claims on Bonanza Creek, and there were no lack of entrepreneurs to take advantage of the gold seekers’ frantic search for amusement and forgetfulness.

The post Gold rush entertainers dazzle Hollywood appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

January 26, 2015

The Mall in Anchorage turns 47

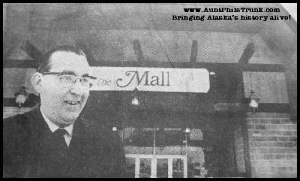

Anchorage grocer Lawrence J. “Larry” Carr beams at the opening of his state-of-the-art mall on Northern Lights Boulevard in 1968.

Forty-seven years ago this month, an Anchorage landmark opened its doors to the public for the first time. When shoppers streamed into The Mall, then Alaska’s largest shopping center, on Jan. 31, 1968, they found a covered, weather-conditioned facility anchored by Sears Roebuck Co. at one end and the newest Carr’s Quality Food Center at the other.

The Mall, located at Northern Lights Boulevard and New Seward Highway, was the brainchild of Lawrence J. “Larry” Carr and was the fulfillment of a dream that he’d had since he sold peaches as a youngster in New Mexico.

Born in Albuquerque, Carr came to Alaska in 1947. The then 18-year-old got jobs working for the Alaska Railroad by day and Thrifty Market at night. He later worked for the H & D markets in Anchorage.

Carr became intrigued by food retailing early in life. He filled his toy wagon with peaches from the family tree and sold them around his neighborhood when he was just a little tyke. As he grew older, owning his own grocery store was always on his mind.

By the time he was 20, Carr had saved enough money to buy a deserted food store in a Quonset hut at 13th Avenue and Gambell Street. For 2-1/2 years, the young grocer tried to turn the dilapidated building into a successful business.

“The walls were so thin and so easy to break through that it was burglarized 14 times,” the great developer of quality supermarkets and artistic shopping centers told the Anchorage Times in 1968. “Another time I went there in the middle of the night to find that the oil line had broken and the heater was off. Almost all the stock had frozen and was a complete loss. And then there was a Thanksgiving when the roof blew off. …”

His young bride, Wilma Moseley, worked shoulder to shoulder with him to build a permanent store at the same location in 1952. But a fire destroyed the building in February 1957. Undaunted, Carr made plans for a bigger store before the ashes had cooled.

Carr teamed up with wholesale grocer Barney Gottstein, president of J.B. Gottstein Co. who’d started a new store, Foodland, in Fairbanks. They built a shopping center in Fairbanks in 1960 and opened Aurora Village in 1965. They also bought the Oaken Keg Spirit shops at Aurora Village and at Foodland in Fairbanks. The same year, the entrepreneurs opened Carr’s Quality Food Center in Kenai.

In 1966-68, the Carr-Gottstein partnership bought two Ben Franklin variety stores and introduced a third when they threw open the doors to The Mall, which still is a staple for Anchorage shoppers today.

The post The Mall in Anchorage turns 47 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.