Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 9

September 10, 2014

Alaska Criminals Run Amuck

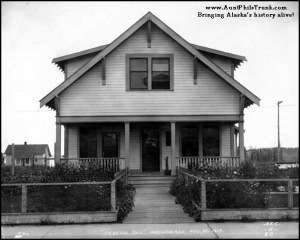

Anchorage’s early jail, in use from 1914 until 1953, originally sat at Fourth Avenue and F Street.

Criminals dabbling in everything from prostitution to bootlegging to gambling flourished in Alaska during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Believing that gold miners and other citizens easily could be parted from their hard-earned income, thugs crossed the border into Alaska when law enforcement in the rest of the United States cracked down on their criminal enterprises.

A January 1921 newspaper article from Juneau captured the flavor of the situation:

“In anticipation of an influx of criminals to Alaska, due to the drive to rid the cities on the outside of the thug element, Chief of Police T.E.P. Keegan is taking steps to secure the cooperation of the federal authorities in Alaska and at the points of debarkation, to have every man coming into Alaska inspected, with a view to ascertain their antecedents, and if not able to prevent them from coming in, to have each one accompanied by a complete record of his character, provided he has a criminal record.

“The matter has been taken up by every city in Alaska with the idea of being able to keep tab on every vicious character coming into the country. Such crimes as that of Monday night when a crew of alleged pirates arrived in Juneau after having, it is alleged, beaten up and robbed the owner of a gas boat and escaped from Petersburg, has awakened the authorities to the necessity of being prepared to cope with a possible flooding of the territory with desperate characters….”

Alaska’s early jails didn’t just fill up with criminals caught by the long arm of the law. They also served as asylums for the insane and often sheltered those who couldn’t help themselves, including alcoholics and injured indigents.

The U.S. marshal supervised the territory’s jails, which included a variety of temporary facilities like a building constructed from metal landing mats in Valdez and a dry well in Kenai. In smaller communities, early territorial police took prisoners home with them or put them in hotels until the malefactors were arraigned or put on trial.

The Anchorage jail, built at the corner of Fourth Avenue and F Street, served the community from 1914 to 1953. It originally housed the U.S. marshal, but in later years was used exclusively as a jail.

Multiple-occupant cells surrounded an open vestibule, where an oil-fired stove provided heat. Prisoners often escaped from the facility, though, because all they had to do was pull up the floorboards, crawl out and run away.

When the new Post Office and Federal Building was designed, the community moved the jail to Third Avenue and F Street and reinforced the walls and floors with tin sheathing.

The post Alaska Criminals Run Amuck appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

August 14, 2014

Nuns Head to Nome

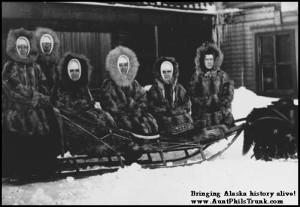

The Sisters of Providence often traveled by dog team during Nome’s cold winters.

Many images come to mind when one thinks of gold rush days in Alaska: bearded prospectors swishing pans filled with water as they search for specks of gold; saloons beckoning the hardworking boys to forget all their troubles with a slug of whiskey and a game of chance; and ladies known as “Lil” leaning against pianos, offering to help miners lighten their leather pokes.

An image that doesn’t usually come to mind is that of four nuns mingling with the masses on the virtually lawless streets of Nome.

The Sisters of Providence foray into Alaska started at the-turn-of-the-last century. At the urging of two Jesuit priests – John B. Rene and Aloysius A. Jacquet – 50-year-old Sister Mary Conrad, Sister Rodrique, Sister Lambert and Sister Mary Napoleon sailed from Montreal, Canada, on June 1, 1902, bound for the shores of Alaska’s Norton Sound to establish a much-needed hospital.

The influx of more than 20,000 prospectors working the gold-filled beaches of Nome brought with it a desperate need for medical facilities. Before the arrival of the Sisters of Providence, the miners relied on home remedies, often set their own broken bones and sometimes used Native healing methods.

After nine days of seasickness aboard the SS Senator, the Sisters’ voyage ended with 72-hours of smallpox quarantine in the Nome harbor. But once ashore, they headed toward Nome’s Catholic Church, celebrated a welcoming mass with the priests and then got down to work.

The purchase and renovation of a two-story building near the Catholic Church came to a capital debt of $7,100. But the Sisters believed that Divine Providence would provide for the material needs of their mission, and they opened the doors of the Holy Cross Hospital on July 15, 1902. They convinced the Nome City Council to pick up the tab for the indigent sick at $1.50 per day, and then charged $3 to those who stayed in the wards and could pay. Patients in private rooms paid $5.

Most of the Sisters’ patients were miners, but they also helped other white residents and Natives. A Nome News headline proclaimed, “Sisters of Providence Have Given Nome the Best Hospital in Alaska.”

The Sisters regularly visited the mines – on foot, horseback or dog sled – to solicit donations. They also sold tickets, as a form of insurance, for hospital care: $3 bought the miner a one-month stay, $12 for six months and $24 for one year.

The price included board, medicines, milk and liquor – as ordered by a doctor – as well as the use of bathrooms and the operating room. Miners had to pick and pay for their own doctors.

According to hospital records, a non-Catholic miner requested a baptism before his death in 1902. He then bequeathed his mining holdings to Holy Cross Hospital. The Sisters quickly sold the property, which helped pay off their debt. By 1911, the Sisters had taken over ownership of St. Joseph’s Hospital in Fairbanks and later expanded into Anchorage in 1938.

The post Nuns Head to Nome appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

August 5, 2014

Earthquakes and Alaska landscapes

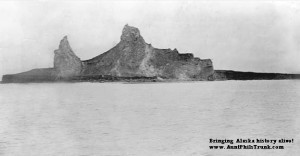

Aleuts were eyewitnesses to how earthquakes formed islands in the Aleutian Chain, including Bogoslov, pictured here.

Alaska’s earthquake history has been written on its landscape – its riverbeds, glaciers and mountains – in the centuries before and since man set foot on the Great Land.

Most of the early earthquake accounts are fragmentary. There are mentions of two in the Aleutians and the Alaska Peninsula as early as 1786 and 1788, when “the land was overflowed by a sea wave, and some lives were lost.”

Perhaps the earliest description that has come down to us, however, comes from a small spot in the Bering Sea that’s undergone greater changes of form than any other part of North America – a little jack-in-the-box island group whose continually changing shape and numbers have long been a puzzle to navigators.

It was early May 1796, when amid thunder, earthquake and steam a volcanic island emerged from the depths of the sea. Von Kotzebue, an early Russian explorer, was told about it by Krukov, a resident agent of the Russian American Co. Krukov, along with Native Aleuts of Umnak and Unalaska, saw the birth of the island because they were on the northernmost part of Umnak Island when the cataclysm occurred.

According to Krukov, on May 7 a storm came in from the northwest and a terrific roaring came back from mountains to the south. An island could be seen rising from the sea, and amid the shaking of the earth, stones were cast from it as far as Umnak, 30 miles away. At sunrise the earth stopped shaking, flames diminished and the newly risen island, shaped like a black cap, could be seen. The island grew in height and circumference, and smoke and steam continued to pour forth.

Even after eight years, Natives reported the water around the island was warm and the ground so hot no one could walk on it.

The Aleuts called the new island “Agashagok,” but since it had appeared on St. John’s Day in their calendar, the Russians called it “Joanna Bogoslova,” St. John the Theologian.

Bogoslov, the island born in the earthquake, continued to change throughout the years, and the Aleutians continued to shake. In 1884, Lt. Stoney, visiting the area in the ship Corwin, stated that many earthquake shocks could be felt even on the anchored schooner. As late as 1910 violent shocks hit Dutch Harbor, shocks probably associated with formation of new islands in the Bogoslov group.

The post Earthquakes and Alaska landscapes appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

July 31, 2014

Aunt Phil’s Trunk Series 2014

Aunt Phil’s Trunk

July 2014 International Blog Tour

1) Inspire to Read blog – South Africa

http://lynelleclarkaspiredwriter.blogspot.com/2014/07/introducing-alaska-and-its-treasures.html

“A must have for the history junky.” – Lynelle Clark

2) Reading Alcove blog – United Kingdom

http://victoriasreadingalcove.wordpress.com/2014/07/02/book-reviews-our-mysterious-and-beautiful-artic-shore/

“It’s a good read, and I highly recommend you check it all out!” – Victoria Adams

3) Book Obsessed blog – Ottawa

http://cecilesune.com/aunt-phils-trunk-vol-1-2-phyllis-downing-carlson-laurel-downing-bill/

“I wish I had books like these when I was growing up. History would have seemed a lot more interesting!” – Cécile Sune

4) Sarah Butland blog – Nova Scotia

http://sarahbutland.com/blog/2014/07/02/aunt-phils-trunk-volume-one/

“Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume One should be in all the schools in the USA, as it was easy and fun to read and contained a lot more than the usual dry facts and dates I remember reading in history class.” – Sarah Butland

5) Little Miss History blog – New York

http://bamauthor.me/2014/07/06/journeying-through-alaskas-history/

“These books are highly recommended for anyone with an interest in Alaskan history, geography and culture … All the volumes are a wonderful addition to the bookshelves of teachers, librarians, historians and the general reader. Well-written comprehensive portrait of America’s forty-ninth state.”

6) KR Morrison blog – Pacific Northwest

https://krmorrison325.wordpress.com/2014/07/09/aunt-phils-trunk-book-tour/

“I am a history nut, and I love Alaska. It would be so grand to have these books in hardcover, gracing my coffee table. Just the thing to read on a cold winter night. Or any night, for that matter.” – K.R. Morrison

7) Lenora’s Culture Center blog – Alabama

http://lenorasculture.wordpress.com/2014/07/08/author-laura-downing-bill/

“Aunt Phil’s Trunk is an entertaining and easy-to-read collection of short stories that really do bring Alaska’s history to life! Anyone interested in Alaska will love this book.” – Lenora Rogers

8) Novel Review Café blog – South Africa

http://novelreviewcafe.blogspot.com/2014/06/blog-tour-aunt-phils-trunk-series.html

“The photo-laden books are a delightful journey through Alaska’s rich past.” – Sandra Valente

9) Ramblings blog – Idaho

http://dawnchandlersramblings.blogspot.com/

“Filled with thrilling tales and wonderful photographs, it is easy to lose yourself in the past of one of our wildest states. I am glad to have had the opportunity to read the first two volumes and am looking forward to the volumes to come.” – Dawn Chandler

10) Publica tu eBook blog – Canada

http://blog.publicatuebook.ca/

“I recommend these books, not only to the people who want to learn about Alaska, but also to anyone who has doubts about the capacity, the courage or the compassion of the human race.” – Joe Cortes

11) Book Reviews by Susan Keefe – Le Mans, France

http://www.susan-keefe.com/aunt-phils-trunk-volumes-1-2-by-laurel-downing-bill/

“Through this very talented author, the true adventures in this harsh landscape are brought vividly to life, not only by the wonderful collection of stories but also by the incredible collection of hundreds of photographs which help to make this book so amazing.” – Susan Keefe

The post Aunt Phil’s Trunk Series 2014 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

July 29, 2014

White Pass Yukon Railway faces dispute

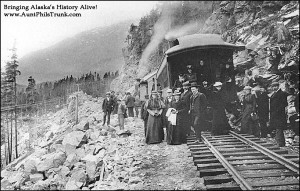

A White Pass and Yukon Railway train rests at the 2,900-foot level of the Alaska-Canada boundary, 13 miles northeast of Skagway in Southeast Alaska, in 1899.

The White Pass and Yukon Railroad Co. began construction of its narrow-gauge railway to access the Klondike gold fields in May 1898. Along with the challenge of crossing coastal mountains – and a vertical rise of 3,000 feet in 20 miles near Skagway – engineers had to work around a boundary dispute between the United States and Canada.

There was no border established between the Great Land and Canada in 1867, when the United States purchased Alaska from Russia for 2 cents an acre. The lack of an agreed-upon boundary caused problems from the get-go.

But it was the Klondike gold rush that brought the boundary issue to a head. When every square foot of ground could yield enormous wealth, the exact location of the border became critical.

The Canadians sent a detachment of North West Mounted Police to the head of the Lynn Canal in Southeast Alaska, a main gateway to the Yukon. Canadian officials wanted ownership of Skagway and Dyea, which would allow Canadians access to the Klondike gold fields without crossing American soil.

But prospectors flooding into Skagway didn’t agree. Some say that a group of heavily armed Americans demanded the Canadian flag at the police post be lowered or the Americans would shoot it down. The Yanks thought that the head of Lake Bennett, another 12 miles north, should be the boundary between the two territories.

The Canadians retreated and set up posts on the summits of the Chilkoot Pass and White Pass – each post equipped with a mounted Gatling gun.

With both the Canadians and the Americans claiming the land as far down as tidewater on Lynn Canal, one can see how relations might be strained as tracks for the White Pass and Yukon Railroad approached the summit of the pass.

A Canadian guard raced to stop construction. He told the railroad men they could come no farther, since it was British territory.

An American named Stikine Bill Robinson went to the summit as an unofficial ambassador. The story goes that he had a bottle of Scotch whiskey in each coat pocket and a box of cigars under each arm. When the guard woke up a few days later, the construction gang was working miles down the other side.

Many thought the railroad project impossible. But thousands of men with picks, shovels and explosives fought harsh climate and tough terrain to lay 110 miles of track through two tunnels, numerous bridges and dozens of trestles to connect Skagway to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, in just 26 months. The railroad was completed on July 29, 1900.

It took several more years before the boundary dispute was settled, however. In 1908, a formal treaty was signed between the United States and Great Britain that set up the International Boundary Commission to mark it officially.

And just as laying track for the White Pass and Yukon Railway was one of the greatest engineering feats of its time, the 1,538-mile-long Alaska-Canada border, marked by metal cones and a clear-cut swath 20 feet wide, signifies one of the greatest feats of wilderness surveying.

The post White Pass Yukon Railway faces dispute appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

July 21, 2014

Alaska treasure 100 years old

Brown & Hawkins general store, left, opened in Seward in 1904.

A turn-of-the-last-century pioneer set down roots in the Greatland in the early 1900s that are still with us today in a historical Seward landmark, the Brown & Hawkins building.

T. W. Hawkins came to Alaska in 1898 via the Chilkoot Pass to Dawson, Yukon Territory. He searched for gold in the Tanana country, and then traveled down river to Nome in 1800, where he met Charles E. Brown.

The pair moved to Valdez, where they formed Brown & Hawkins, a general merchandise business, in March 1903. Hawkins traveled to a new townsite called Seward later that year and opened a small store. He constructed a large building, and in 1904, transferred the firm’s business from Valdez.

The store sold groceries, clothing, hardware and other supplies for miners and fishermen. Hawkins and Brown also acted as transportation and communications agents at various times. Hawkins, who was involved in the Democratic Party, even went as a delegate to the Democratic Territorial Convention in Juneau during May 1908.

Over the years, he and Brown enlarged the original store, added warehouses and opened smaller stores at railroad construction camps.

The frontier businessmen then took advantage of a ready market for goods in an area where miners and trappers were just settling. They chartered the SS Bertha in 1912. Loaded with groceries, clothing, hardware and a gold scale, the ship sailed up the Cook Inlet and stopped off in a place called Ship Creek to trade with those who were filing into the back country.

Because the Cook Inlet tides were so severe, the Bertha was hauled up onto the mud flats and anchored. The miners and trappers who climbed aboard the trade ship called it the “anchorage,” which is where some say the town’s final name was derived.

The Bertha later met her end during a violent storm off the Aleutian Chain. After her demise, Brown and Hawkins moved their business ashore and opened a branch in Knik in 1913. They then built the first bank and general store at the corner of what is now Fourth Avenue and E Street in 1915 in the new railroad town of Anchorage. Due to extensive damage, the original building was torn down after the 1964 earthquake.

According to Virginia Hawkins Darling in an interview with the Anchorage Times in November 1970, “My father managed the Brown & Hawkins interests in Seward and Charles E. Brown managed them in Anchorage. The Anchorage interests of Brown & Hawkins were sold just before the untimely death of Charles E. Brown in 1929.”

Hawkins, in ill health in 1946, leased out the grocery and hardware portions of the Seward store to son James. T. W. Hawkins died later that year.

In 1956, Hawkins’ daughter, Virginia Hawkins Darling, and her husband took over management of the store. When Virginia became ill, her son, Hugh, and his wife, Iris, came to Seward and took over operations in 1989. The store has the distinction of being the longest one-family continuously owned and operated business in Alaska. And Iris Darling was a fixture at the store until it closed its doors permanently in 2013.

The post Alaska treasure 100 years old appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

July 14, 2014

Demon rum finds its way to Alaska

Many early Anchorage residents enjoyed illegal libations made in bootleggers’ cabins, like this one near Chester Creek.

When the U. S. Army took over responsibility for administering Alaska in 1867, law enforcement found it had its hands full trying to stem the flow of liquor into America’s newest property. Up until alcohol possession was legalized in 1899, smugglers brought their illegal brew into Alaska via whalers, fishing vessels, American and foreign ships and Indian canoes from both British Columbia and U.S. ports.

Enforcement also had problems controlling the manufacture of “hootch,” a name taken from the Tlingit village of Hootchenoo or Hootznahoo. The distillers of “this vile stuff” had learned their trade from soldiers stationed at Sitka.

Since the opportunity to make a bundle of cash in the illegal trade of spirits encouraged dishonesty, many early government officials looked the other way. Some even assisted the smugglers. Evidence that law enforcement was ineffective in rooting out “the demon rum” was evident in Southeast Alaska where 27 saloons operated openly in Juneau in 1895, and just about as many flourished in Sitka and Wrangell.

However, the tide turned against the smugglers in 1898 when a grand jury in Juneau indicted seven customs officers: four who helped smuggle liquor into Alaska and three who sold impounded liquor to thirsty prospectors.

Dry laws were enacted in Alaska in the early 1900s and not repealed until 1934. But that didn’t stop smugglers from getting alcohol into the railroad town growing along Ship Creek, even though the Alaska Engineering Commission had banned spirits on its property.

On June 19, 1915, President Woodrow Wilson issued regulations pertaining to the Alaska Railroad townsite that later became Anchorage. The detailed rules for the conditional sale of lots at public auction contained one clause that reflected hopes for high standards of sobriety. The lots and payments for them would be forfeited if the property were “used for the purpose of manufacturing, selling, or otherwise deposing of intoxicating liquors as a beverage, or for gambling, prostitution, or any unlawful purpose….”

While teetotalers, government officials and law enforcement kept a wary eye out for liquid contraband, bootleggers managed to supply those thirsty for their product by coming ashore in what’s known as “Bootleggers Cove,” an area hidden by a bend in the shore line along Cook Inlet.

Bootlegging continued to be an underground industry during the 1920s, and Anchorage children were paid a $5 reward for telling officials about the locations of illegal stills.

But even respectable families dabbled in the “devil’s drink.” Some made their own home brew, while others, like Frank M. Reed, made a few bucks off the thirst of their neighbors. Reed, who later became an Anchorage banker and community leader, started his entrepreneurial career collecting bottles discarded by guests at his mother’s Anchorage Hotel and selling them to bootleggers for 35 cents a dozen!

The post Demon rum finds its way to Alaska appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

July 8, 2014

Adventurers carve postal system through Alaska wilderness

Aviator Carl Ben Eielson, left, completed the first experimental mail flight between Fairbanks and Nenana on Feb. 21, 1924.

The first post office in Alaska was established in Sitka on July 23, 1867. John H. Kindaid, who later became an Alaskan governor, was named the first postmaster, three months before Alaska was formally transferred from Russian to American rule.

“The Russians maintained no postal system in Alaska,” wrote James S. Couch in “Philately Below Zero.” He explained: “All communications between Russia and Russian America was carried on via dispatch cases transported by Russian supply ships, and Russian residents dispatched and received both business and personal mail through the Russian commanders of the community – there was no post office system as we know it.”

With the gold rushes came the first attempt to introduce horses as beasts of burden in the new land of ice and snow. But deep snow proved too much of a handicap. Next, reindeer and dogs were tried. The reindeer proved stubborn and impossible to harness break, so it was up to the dogs.

In the Interior, the dog team was the first to prove successful in delivering mail and the last to give way to the new-fangled airplane. But the dogs did have to give way after a long and illustrious service.

On Feb. 21, 1924, Fred Milligan was driving his dog team with the U.S. mail on a bitterly cold day through deep snow on the trail between Nenana and McGrath – a 20-day run – when he and the dogs heard a sound from the sky. They stopped, looked around and then gazed skyward.

Milligan heard a strange noise. It grew louder. Then he saw an airplane passing overhead, with its pilot waving from the open cockpit. It was Carl Ben Eielson in his small, single-engine plane.

That was a milestone in Alaskan history. As Milligan and his dogs plodded on to the end of the day’s run, the plane passed again on its return trip from McGrath. Eielson had proved that carrying the mail by flying machine was practical, safe, economical and fast.

The last official dog team mail contract expired in 1949 – the mail run between Rampart and Fairbanks – but dogs continued to carry mail between Central and Miller House on the Steese Highway in emergencies. And airplane competition didn’t stop Chester Noongwook of St. Lawrence Island from continuing his dog sled mail run until 1963, the last mail deliver of its kind in the country.

The post Adventurers carve postal system through Alaska wilderness appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

June 30, 2014

Chickaloon coal drive helps to build Anchorage

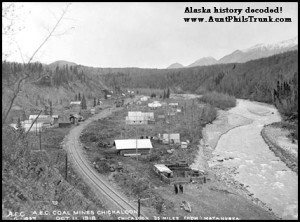

First the U.S. Navy dug for coal at Chickaloon in the Matanuska Valley and then came the Alaska Engineering Commission.

In the early 1900s, coal was being shipped from as far away as Cardiff, Wales, to the U.S. Navy’s coal station at Sitka. Some thought that the coal deposits at Chickaloon in the Matanuska Valley might meet the Navy’s requirements.

Along with federal Bureau of Mines director A.M. Holmes, Jack Dalton went to look the mine over in 1913. When Holmes concluded the coal would suffice, he gave Dalton the task of figuring out a way to get the coal from the mine to tidewater – at a cost the Bureau could afford.

Dalton concluded that the Matanuska River, when frozen, could be used and that horses could do the conveying. He headed for Seattle where he picked up supplies, men and horses. He headed back to Alaska on Nov. 5 aboard the General Hubbard, recruiting more men along the way.

He reached Knik Anchorage at the mouth of Ship Creek on Nov. 16 and put his outfit ashore. Moving up the east bank of Knik Arm, the party reached Old Knik, above Eklutna, where Dalton established his headquarters.

Forty-five miles of road and many bridges would be required. Three miles ran from the mine to the bank of the Matanuska River, and then from Eska Creek, the road would go to a tidewater landing.

As soon as the ice was thick enough, freight began to move. Fifty-four horses pulled five bobsleds, which carried from three to seven tons of coal. By January 1914, 700 tons had been carried as far as Eska Crossing. By Feb.1, the entire lot had left Chickaloon.

One month later, 900 tons of coal was stacked up at ice-blocked Cook Inlet. The estimated cost of freighting the coal stood at $65,000.

Later, after the ice went out of the Inlet, the coal was placed aboard the battleship U.S.S. Maryland, for testing. But before anything could be done about providing a regular supply of coal, the Navy converted to oil.

Although the Navy didn’t use the coal, far-reaching consequences followed Dalton’s successful plan. An article in the July 1963 Alaska Sportsman said the Matanuska coal had a great deal to do with the decision to build a government railroad from Seward to Fairbanks:

“By the time Jack Dalton died in 1944, the town at the mouth of Ship Creek, created by the railroad, was well on its way to becoming the largest city in Alaska.”

The Alaska Railroad erected a historical marker at the spot formerly known as Matanuska Landing, where the railroad track now crosses the Matanuska River. It commemorates Jack Dalton’s efforts to bring the Matanuska coal to tidewater.

The post Chickaloon coal drive helps to build Anchorage appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

June 23, 2014

Last shot of U.S. Civil War lands in Bering Sea

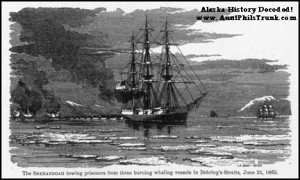

Confederate ship The Shenandoah fired on whaling ships in the Bering Sea of Alaska on June 25, 1865.

Seventy-four days after Appomattox, and almost two months after the Confederate Army stopped fighting on land, the last gun of the U.S. Civil War was fired in the Bering Sea.

Not knowing the war had ended, the commander of an English-built Confederate vessel named The Shenandoah fired upon several whalers near Saint Lawrence Island on June 25, 1865. Vessels flying British, French and Hawaiian flags were inspected and let pass, but American whalers were seized, according to an article written by Robert N. DeArmond in the July 1937 issue of The Alaska Sportsman.

The Shenandoah was one of several ships used by the Confederates to disrupt Yankee commerce on the high seas. The 1,100-ton steamer was built in Glasgow in 1863 and purchased by the Confederate government in 1864. She measured 230 feet, had a 32-foot beam and drew 15 feet of water.

During her 13-month saga with the Confederate Navy, The Shenandoah covered 58,000 miles and captured 38 Yankee ships, 25 of which were after the war was over. And her crew never took a life.

Following the capture of the American whalers in the Bering Sea, The Shenandoah followed other whalers that had slipped into the Arctic Ocean. She passed through the Bering Strait and into the Arctic, but after a few miles, was forced to turn southward due to ice.

While sailing in a dense fog, The Shenandoah slammed into ice floes that almost tore off her rudder and threatened to crush her hull. After several hours, however, she managed to steam free of the ice and continue on her course.

The Shenandoah sailed down the Aleutian Chain and set a course for the coast of California. On Aug. 2, just 13 days out of San Francisco, she overtook the English bark Barracouta. That’s when the crew learned the war was over.

The commander needed to take his ship to some port for surrender, but part of the crew wanted to put into a South American port, while others wanted to be landed in Australia or New Zealand.

After careful consideration, Lt. Waddell decided to run the gauntlet of federal cruisers and take his ship to a European port. He reached Saint George’s Channel on Nov. 5, without sighting any land on the way, 122 days after leaving the Aleutians.

On Nov. 6, The Shenandoah dropped anchor in Mersey off Liverpool. The crew hauled her flag down and surrendered her to the British government. The Brits eventually freed the officers and crew and then turned the ship over to the United States.

The post Last shot of U.S. Civil War lands in Bering Sea appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.