Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 5

September 1, 2015

Black Wolf Squadron touches down in Nome

Fairbanks residents inspect one of the planes from the U.S. Army Black Wolf Squadron in September 1920 during the squadron’s return flight from Nome to the Lower 48.

Soon after the end of World War I, Brigadier Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell organized a flight of four De Havilland DH-4B aircraft from Mineola, New York, to Nome. The general wanted to show that airplanes could play an integral part in the nation’s defense.

The Alaska flying expedition was named the Black Wolf Squadron. The group set out from New York on July 15, 1920, to “demonstrate that we could establish an airway to Alaska and Asia,” according to Stevens.

Due to a multitude of stops, inclement weather and a few mechanical problems, it took a month for the planes to fly across America and Canada. The squadron landed in Wrangell on August 14.

The pilots then had a couple more stops on their way to Nome, including layovers in Fairbanks and Ruby. One pilot made a side trip after the planes left Wrangell, and became the first ever to fly over Juneau. He dipped down over the city and dropped a package to Governor Thomas Riggs.

The Black Wolf Squadron finally touched down on the old parade ground at abandoned Fort Davis, three miles east of Nome at the mouth of the Nome River, at 5:30 p.m. on August 23. The citizens of Nome had readied a strip 400 yards long and 100 yards wide for the event.

The squadron had traveled 4,500 miles in 55 hours flying time, proving that air travel to the northwest corner of America was possible – and that air transportation in Alaska could become more than a dream.

The four airplanes arrived back in New York on October 20, 1920, three months and five days after their departure.

Then Clarence Oliver Prest decided to fly from New York to Nome in his biplane named Polar Bear II in the summer of 1922. All went well until Prest departed from Dawson City, Yukon Territory. After having engine trouble, he crash-landed on an isolated beach near Fort Yukon.

Prest, who had failed a year earlier to fly Polar Bear 1 from Mexico to Siberia – an idea conceived in a darkened saloon with friend “Mort” Bach – was transported by riverboat operator Gilbert Cook to Tanana and then made his way to Fairbanks. Prest became the first in a long and famous list of aviators to crash in the unforgiving terrain of Alaska’s wilderness.

Early Alaska aviators could not call ahead and ask if a community had a suitable landing strip for their new-fangled flying machines. The adventurous flyboys simply looked for open spots to land.

A controlled crash into deep snow usually followed.

The post Black Wolf Squadron touches down in Nome appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

August 20, 2015

An update of happenings with Aunt Phil

Come by the Aunt Phil’s Trunk booth on the Purple Trail at the Alaska State Fair from Aug. 27-Sept. 7!

The Alaska State Fair is opening next Thursday, Aug. 27, and will run through Labor Day, Sept. 7. If you are planning to visit the fair this year, make sure to stop by my booth on the Purple Trail (next to the face-painting people and across from the Pasty Shack) and say “Hi!”

In other news, I just finished writing Volume Five in the Aunt Phil’s Trunk Alaska history series. It will feature stories from the first 25 years of statehood, including accounts of those who experienced the Good Friday earthquake of 1964, building the Alaska pipeline during the 1970s and a few mass murders from the early 1980s that ended that period in Alaska’s past. Hopefully, this exciting new book will be available by November, so I will have it for all the holiday shows and in time for Christmas presents for all you history buffs! I am designing the cover now, so stay tuned for a sneak peak in the weeks to come.

And it appears that my new weekly television show, titled “Alaska Story Time with Aunt Phil” on CBS KTVA Channel 11, is a hit. Rave reviews are reaching both the TV station and me, so it looks like I will be sharing Alaska’s history every Monday morning for quite some time! I’m posting a link below so you can watch these short shows if you don’t live in Alaska (they are only about 4 minutes each).

Click here to watch segments of Alaska Story Time with Aunt Phil!

The post An update of happenings with Aunt Phil appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

August 3, 2015

Alaska Natives earn recognition by 1900s

Only Natives who wore Western clothing and met other conditions could vote in the early 1900s.

After decades of not being recognized by the federal government, Alaska Natives marked a milestone in the mid-1930s. Amended in 1936 to include Alaska, the Indian Reorganization Act of 1935 allowed American Indians to locally govern their affairs by a tribal government that was established by constitution and bylaws for each tribe.

Through its enactment, tribes were allowed to manage their own affairs, such as ownership and transfer of title to land and to keep records of vital events, establish their own police and court systems and set the terms of enrollment in their tribes. Alaska Natives had been working toward recognition decades before the Act was passed.

They were not considered citizens when America purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867 because they were not “civilized.”

And only citizens of the new American possession could own land, operate a business or vote.

In 1912, tribes in Southeast organized the Alaska Native Brotherhood; three years later the Alaska Native Sisterhood held its first meeting in Sitka.

Although the groups originated in Southeast Alaska – primarily among Tlingit and Haida Indians – the organizations eventually included Natives from all regions, as well as some Caucasian members.

It took years of hard work, but Alaska Natives were given the right to vote in 1922. However, certain conditions had to be met.

“Wear Western clothing; not eat Indian foods or speak Indian languages; and live apart from Indian village communities” were among the list of criteria that would make an Alaska Native eligible to vote. This was nothing new. Alaska Natives were familiar with restrictions put upon them by the government.

In 1915, the Alaska Territorial Legislature had passed a law that allowed a Native to become a citizen only if five white people testified that the Native person had met legal criteria – meaning he or she had given up Native culture in favor of Western ways. But early Native leaders knew that the only way to improve their situation in the white man’s world was to work within the system.

An article titled “Alaska Native civil rights history shaped the state,” which appeared in the December 4, 2007, issue of The Northern Light newspaper, described what life was like behind the scenes.

“What was done in public and what was done in the home, was not necessarily the same,” Helen McNeil, a Tlingit in the Alaska Native Sisterhood, told reporter Mary Lochner. “Many (Tlingits) would speak only English in public, but still speak Tlingit in the home.”

Alaska Native leaders learned to use the power of the vote to influence policies that affected Natives’ lives.

They sent advocates for anti-discrimination legislation to testify before the Territorial Legislature and pushed for equal education and recognition of land ownership for their people.

A milestone was passed in 1924 when Congress extended citizenship to all Indians in the United States and Tlingit William L. Paul Sr. was elected as the first Native to the Territorial Legislature.

But all was not rosy for the Alaska Native population following these two historic events. The Alaska Territorial Legislature put its own restrictions on who could become an Alaska citizen.

It passed a law requiring a literacy test be passed before a Native would be allowed to vote. That requirement was in effect until Alaska adopted its constitution in the late 1950s.

The post Alaska Natives earn recognition by 1900s appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

July 21, 2015

How did Alaska get its name?

Russia transferred Alaska to the United States at Sitka in 1867.

The man credited with purchasing Alaska from the Russians in 1867 probably signed his name to more government documents than any man of his day. He also appears to be the chief architect of the name given to America’s new possession.

William H. Seward, born May 16, 1801 in Orange County, New York, held many high political offices during his career in government. Along with the Treaty of Cessation for the purchase of Alaska, he also signed the Emancipation Proclamation and the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, signed on July 9, 1868, which grants citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” including slaves recently freed. It also forbade states from denying any person “life, liberty or property, without due process of law,” and guaranteed equal protection under the law to all.

Prior to that, the people of New York had elected Seward governor of their state – twice – and he served as the state’s U.S. senator. He later joined the anti-slavery movement, which split the Whig Party. He then ran in the Republican primary against an Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. He lost the primary, but Lincoln appointed him his Secretary of State.

Seward also may have been responsible for giving Russia America its new name following the famous land negotiations during 1867. His son, Frederick W. Seward, was the assistant secretary of state at the time and witnessed his father deciding what the new possession would be called after he struck a deal with the Russians, according to an article titled, “What’s In The Name ‘Alaska?’ written by Jay Stauter of Seward for The Anchorage Times on May 16, 1966.

Stauter found the following excerpt in the middle of page 364 in junior Seward’s book, Reminiscences Of A Wartime Statesman And Diplomat, published in 1916.

“On a bright day in August [actually was Oct. 18], 1867, with brief but impressive ceremonies, amid salutes from the Russian and American naval vessels, the American flag was raised over the new territory thenceforth known as ‘Alaska,’” Frederick Seward wrote of the transfer ceremony in Sitka.

“This ceremony might be called a christening as well as the transfer. The territory had previously been known as ‘Russian America.’ During the progress of the treaty through the Senate, there were occasional discussions of the name to be bestowed upon it by the United States.

“Several were suggested as appropriate, among them ‘Sitka,’ the name of the capital, ‘Yukon,’ that of its chief river, ‘Aliaska’ or ‘Alaska,’ derived from the name of its great peninsula ‘Oonalaska’ and ‘Aleutia,’ derived from its chain of islands. Seward, with whom the final decision rested, preferred ‘Alaska’ as being brief, euphonious (agreeable to the ear), and suitable. The name was generally accepted with favor and began to be used before the transfer was made.”

Stauter went on to say that since William Seward was in intimate daily contact with his father, and included in conferences and correspondence during this period, he is a rather reliable witness to how the name Alaska was chosen over all other names suggested at the time.

The post appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

July 6, 2015

Aunt Phil Featured on CBS KTVA Channel 11 Anchorage!

CBS Channel 11 reporter Rhonda McBride interviewed author Laurel Downing Bill, who shared bits and pieces about some colorful characters that helped make Anchorage the wonderful city it has become over the past 100 years.

CBS KTVA Channel 11 of Anchorage featured Aunt Phil last Sunday on Rhonda McBride’s show, Frontiers, at 8:30 a.m. and 10:30 p.m. Reviews have been overwhelming – looks like people really enjoyed learning about a few colorful characters in early Anchorage history.

Here is a link to the expanded Web version if you’d like to check out the television program: http://www.ktva.com/shows/frontiers/web-extra-history-of-anchorage-546/

Also, producers enjoyed the segment so much they invited me on the early morning show today. Here is the link to that short segment: http://www.ktva.com/alaskan-book-series-a-treasure-trove-of-historical-goodness-310/

And it looks like they want me to come back! Beginning in a week or so, I will be featuring stories from Alaska’s rich past on a regular basis once a week. I’ll keep you posted about that in the next blog.

Happy July to all you wonderful Alaska history fans!

The post Aunt Phil Featured on CBS KTVA Channel 11 Anchorage! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

June 23, 2015

St. Michael Alaska Awakens

After miners discovered gold in the Klondike, St. Michael became a shipbuilding hub.

On June 25, 1897, the sleepy old Russian town of St. Michael Alaska awoke when the river steamer Alice arrived with 25 miners from Dawson carrying $500,000 among them in gold dust. That was enough to liven up just about any town.

But the party wasn’t over. Two days later, the P.B. Weare carried in another group of successful men who staggered off the small steamer with pokes of gold estimated to be worth up to $175,000.

And more miners followed. St. Michael became the hub for those with visions of nuggets dancing before their eyes, both coming from and going to the rich fields in the Yukon.

The Yukon River carries about two-thirds the volume of water of the mighty Mississippi and is loaded in the summer with the soil debris of ground glacial rock and silt from banks cut by the current.

The debris, deposited on the wide, fan-shaped flats that reached out into the Bering Sea, prohibited large ocean ships from entering into the deep current of the stream. All passengers and cargo had to land at St. Michael and transfer to small river steamers.

With the lure of big money to be made, commercial and trading companies built warehouses to help with the transfer of goods and fleets of steamers to convey the “gold-crazed lunatics” and their freight up the Yukon.

The Northern Commercial Co., and its rival, the North American Transportation and Trading Co., enlarged their facilities and built boats at a feverish pitch. New companies like the Alaska Exploration Co. and the Seattle Yukon Transportation Co. also sprang up.

Some of the companies shipped parts and pieces for boats on ocean liners headed north, and then men assembled the steamers, barges and tugs in St. Michael. As the gold rush wore on, river steamers were built in Seattle and gingerly made the 2,300-mile voyage on the open ocean under their own power. Some were towed by large ships.

Transportation opportunists weren’t the only ones eying the potential for profits in St. Michael. Gangs of gamblers pitched tents along the beach and welcomed those passing through to try their hands at games of chance.

In an effort to dissuade the con men, the U.S. War Department built an army post, Fort St. Michael, and set up a 100-mile reserve around it. The commander of the post then ordered the gamblers and “sure thing” men to leave.

River steamers could only make 100 miles a day churning against the powerful current of the muddy Yukon. Running one-half to six miles per hour, it took more than two weeks for the boats to make the 1,600-mile trip to Dawson and the Klondike.

The post St. Michael Alaska Awakens appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

June 9, 2015

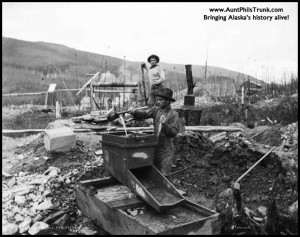

Gold helped settle Alaska

Prospectors worked hard to find golden riches in Alaska during the gold-rush era.

Gold fever began rather tepidly in Alaska. Although Russian fur traders were aware of gold deposits found in Russian America in the mid-1700-1800s, they weren’t anxious to have gold-seeking outsiders combing their new land. So they said little about the discoveries of the bright gold metal.

English missionary Robert McDonald, who researchers say found gold in the Circle area round 1863, also did not bring light to his discovery. He was more interested in souls than gold.

Once the Americans took possession of the Great Land in 1867, however, interest in gold began to rise. Especially when a few men found promising prospects on the Stikine River in Southeast.

The first known discovery of gold by a white man came in 1861 when Hudson Bay Company employee Buck Choquette found gold on the Stikine, on what is now called Buck’s Bar. His find attracted a few men into the region through the Stikine waterway near Redoubt St. Dionysus – or Wrangell, one of the oldest non-Native communities in Alaska. It has been governed by four nations: Tlingit, Russian, British and American.

When Henry Thibert and Angus McCulloch found gold in the Cassiar District of Canada in 1871, a huge stampede headed north via the Laird and Cassiar routes.

Over the next several years, prospectors found small deposits in Southeast and several near Sitka, Alaska’s capital at the time. The lodes near Sitka drew interested mining parties north, and in the late 1870s, a German assayer George Pilz encouraged Richard Harris and Joe Juneau to prospect more of the mainland.

In August and September of 1880, the men made a discovery that led to the development of the Harris Mining District. They named the gold-mining settlement Harrisburg. The named changed to Rockwell in 1881, and it was changed again soon thereafter to Juneau.

Within a short time, many mines became active in Juneau and Douglas, an island across from what now is the capital of Alaska. The world-famous Alaska-Juneau mine became the largest low-grade ore gold mine in the world.

The rich strikes in the Juneau area drew many more prospectors into the coastal regions of Southeast Alaska. Many became miners for a few months in Juneau to grubstake themselves so they could seek their own pots of gold. Some found prospecting to be a miserable disease. Others saw it as a way to become self-sufficient. But for Alaska, their mining activities helped the economic development of Alaska as an American possession through exploration and settlement.

Many prospectors moved on to the Klondike in 1898 and then into Alaska’s Interior during the early 1900s. Their histories show some worked a winter or two in the Juneau area in order to finance their journeys into the Yukon and Tanana watersheds. Reseachers who followed the rush for gold into the north can trace some names from the Juneau district to the Fortymile, Circle, Nome and Fairbanks districts.

The post Gold helped settle Alaska appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

May 27, 2015

Railroad births Anchorage

Miss White drove the first spike into the track for the Alaska Railroad in Anchorage on April 29, 1915.

Unlike other settlements in Alaska’s past, Anchorage didn’t evolve as a result of gold, furs, fish or timber. As late as 1913, there was no town at the head of Cook Inlet. There was only a spot called Ship Creek, where small ships entered because the creek was deep enough.

But a couple of years later, the federal government needed coal for its Pacific fleet. In order to access massive coal fields in the Matanuska Valley, it started laying 470 miles of railroad track that would eventually connect Seward with Fairbanks. Anchorage, which was at the midpoint and had a protected anchorage that could be dredged, was chosen as headquarters for the project.

Hordes of job seekers poured off boats during spring 1915 and pitched tents all along Ship Creek. With no sewers, and Cook Inlet tides providing the only means of waste disposal, the Alaska Engineering Commission surgeon warned that water supply would become contaminated if settlement on the flats continued.

The AEC had its railroad engineers quickly lay out a town, and in July, the Land Office auctioned off 655 lots for a total of $148,000. Among those buying lots were Swedish-born Oscar Anderson, the town’s first butcher, and Della and Irving Kimball, who bought lots at the corner of West 5th Avenue and E Street and started a dry goods business.

The AEC gave the order that all tents had to be moved from the Ship Creek flats to the new town site by mid-August. While some lot owners moved their tents, others hastily chopped down trees and constructed frame buildings. The new town became a hodgepodge of dwellings.

During the mad dash to develop the town site, settlers also decided their new city needed a name. Monikers considered included Matanuska, Whitney, Terminal, New Knik, Alaska City, Ship Creek, Woodrow City, Gateway, Winalaska, Homestead, Lane – then Secretary of the Interior – and Brownsville – after one of the original settlers. It’s widely believed that Anchorage, submitted by Ray McDonald, won in an election held on Aug. 2, 1915.

However, according to records of the AEC, discovered by M. Diane Brenner, past archivist for the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, the vote went to Alaska City. The second-highest vote was for Lane. Anchorage came in third.

The settlers later learned that the U.S. Post Office already had arbitrarily named the new Alaska settlement Anchorage.

As the town boomed with the construction of the railroad, the Land Office continued to sell lots and lease business sites. By 1917, Anchorage had a population between 6,000-7,000 and boasted a hospital, a school, a telephone/telegraph/electric office, several churches, a Masonic temple, concrete sidewalks and graded streets.

Today, Anchorage is home to more than 300,000 and is Alaska’s largest city.

The post Railroad births Anchorage appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

May 14, 2015

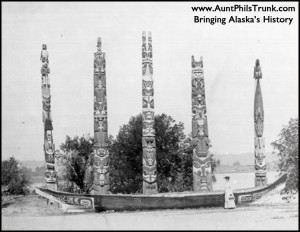

Alaska totems educate millions in 1904

Chief Saanaheit from the Kaigani Haida village of Kasaan on Prince of Wales Island donated these totem poles and a canoe to Gov. John Brady for a display at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis.

When John Green Brady, governor of the District of Alaska, was asked to create an exhibit to publicize the Great Land for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904, he decided to showcase one of Southeast Alaska’s most recognizable features: totem poles.

Brady thought a display of poles carved by Alaska’s Native people would draw crowds to the exhibit where they then could learn about the real Alaska – not an icebox, but a land that offered much for tourism, settlement and development.

The governor sailed to Tlingit and Haida villages between 1903-1904 and asked leaders along the way to donate poles and other cultural objects for the exposition. Several decided to trust Brady and chose to share their heritage with the world.

Fifteen totem poles, two dismantled Haida houses and a canoe from villages like Old Kasaan, Howkan, Koianglas, Sukkwan, Tuxekan, Tongass, Klinkwan and Klawok were delivered to the St. Louis fairgrounds. A crew of Native carvers accompanied the poles in case some of the pieces needed repair.

When the Louisiana Purchase Exposition opened that April, Alaska Native totem poles helped tell close to 19 million visitors about Alaska’s past, heritage and resources. Exhibits filled with technological marvels like electric lighting, the wireless telegraph and newfangled automobiles showed them the future.

When the exposition closed that December, the Alaska exhibit traveled to the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. There the poles and canoe stood along the shores of a man-made lake on the fairgrounds from June until October.

The poles then began their long journey home. They arrived in Sitka in January 1906 and were repaired by skilled local carvers before going to their final home – the first totem pole park in Alaska.

Photographer E.W. Merrill designed the alignment of the poles, and prisoners from the local jail contributed the labor to get the poles in place. By March, Brady’s vision for a totem park in Sitka came to fruition. However, the totem tradition in other parts of Southeast Alaska almost died out a few years later.

Some missionaries visiting several Native villages mistakenly assumed that these poles were pagan symbols. They did not know that Alaska’s First People carved the poles as a way to share the stories of their ancestors, their history and their culture. They did not know that the carved figures stacked on the totems each had a specific significance that helped tell family and clan histories, major events, achievements, deaths and more.

Zealous missionaries persuaded the people of Kake to cut down and burn their totems in 1926. Other villages lost their totems, as well. But a decade later, U.S. Forest Service people and workers in the Civilian Conservation Corp found a few forgotten totems in villages along the waterways of Southeastern Alaska. They knew the totems had to be saved.

They organized a totem roundup, and using CCC funds, paid for more than 200 Native carvers and laborers to restore and replicate the poles. Some poles were so badly damaged that they had to be recreated from memory.

This effort proved successful. Many totems were brought back to their former glory.

It took another 40 years, but Kake also brought its totem culture back when, on Oct. 1 1971, it raised what was proclaimed to be “The World’s Tallest Totem Pole.”

Carved in 1967 to honor the 100th anniversary of the Alaska purchase, the raising of the pole in Kake was an attempt to symbolically rectify the burning of Kake totems in 1926. And although it is not the tallest in the world (it is the third tallest), the totem still stands in Kake at 137.5 feet tall.

The post Alaska totems educate millions in 1904 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

April 23, 2015

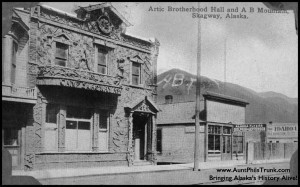

Arctic Brotherhood born on the high seas

This postcard from 1912 shows the first lodge of the Arctic Brotherhood, with driftwood placed on the façade, as well as a mountain behind with the letters AB prominently painted on its side in Skagway. A note on the back of the photo states: “Only ‘sourdough’ Alaskans may be members of this lodge.”

What Alaska connection do England’s King Edward VII, Al Capone’s chief legal counsel, Albert Fink, and American presidents Warren G. Harding, Theodore Roosevelt and William McKinley have in common? They are all honorary members of the Arctic Brotherhood club.

This fraternal club, which at its height boasted around 10,000 members in the early 1900s, was the brainchild of sea captain William Connell, a hospitable man who had a reputation for keeping company with his passengers aboard the steamer, City of Seattle. On this particular voyage from Seattle to Skagway, he and a group of Klondike gold-seekers were having a great time sharing stories, as well as drinking a bit of alcohol, in the ship’s dining room.

“We should form a great social brotherhood of the North where men from all parts of the world could meet and get to know one another,” Connell told his new comrades.

The 11 men seated around him whole-heartily agreed, according to Arctic Brotherhood historian I.N. Wilcoxen, who in 1903 described that original meeting.

“Being liberal of purse, and always enjoying the best obtainable, they ate, smoked and drank liberally of the best the Steward had. They found they were ‘Arctic Brothers,’ and proposed to celebrate the discovery by a night of revelry, mirth and laughter.”

And while enjoying their new-found friendships, the men drafted up the bylaws to their club and the rules of order. The preamble to the fraternity’s constitution stated:

“The object of this organization shall be to encourage and promote social and intellectual intercourse and benevolence among its members, and to advance the interests of its members, and those of the Northwest section of North America.”

The rules restricted membership to white males more than 18 years old who lived in Alaska, the Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territory or British Columbia north of the 54th parallel. The men also decided that membership into their elite club could only be achieved if a candidate was nominated by a member in good standing and that said nomination had to be approved by a membership committee.

Since the idea for this one-of-a-kind northern fraternity was born during an evening where liquid spirits liberally flowed, it is no great surprise that the first badges for the officers were champagne corks and ordinary members wore beer corks.

The men settled on an initiation fee of $1 to be used on “a royal good time,” according to an article written by Ken Spotwood for Dawson’s community newspaper, The Klondike Sun.

Soon after the ship docked, the founding fathers established Camp. No. 1 in Skagway. They also created an official emblem for the Arctic Brotherhood that featured two crossed flags – the English Union Jack and the American Stars and Stripes – along with a miner’s gold pan that had a crossed pick and shovel with the letters A.B. emblazoned upon it. Gold nuggets encrusted the entire design with the motto: No Boundary Line Here.

No boundary line, indeed. These original members took off toward the gold fields of the Klondike and spread their message of friendship and camaraderie. Within a month, their membership numbered more than 300. They established Camp No. 2 at Lake Bennett and Camp No. 3 at Atlin, B.C. It wasn’t long before they had 30 clubs going throughout the North Country.

The Arctic Brotherhood was generally a social club for adventurers, but it also included doctors, celebrities, elected officials (both American and Canadian) and lawyers like the honorable James Wickersham. The AB lodges didn’t just have drinking parties, they also took care of members when they were sick, buried those that died and worked toward improving conditions in the mining camps. The club appears to have disbanded around 1931.

The post Arctic Brotherhood born on the high seas appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.