Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 4

March 2, 2016

Dinosaurs roam Alaska grasslands

This photo shows the footprint of a hadrosaur, also called the duck-billed dinosaur. The first evidence of dinosaurs in any national park unit in Alaska were those found in Aniakchak National Monument.

My 2-year-old grandson Aiden is crazy about dinosaurs. So much so that we decorated his birthday cake last weekend with small brontosaurus, nanosaurus and T-rex replicas. He received an abundance of dinosaur-themed gifts, too, including dino sippy cups, dino books, dino imprinted T-shirts and a multitude of dinosaur toys.

I went to bed Sunday night and dreamt about dinosaurs all night! When I woke up, I still was thinking about T-Rex and his buddies. Then something rang a bell in my memory bank about dinosaurs once inhabiting Alaska.

In 1978, two geologists stumbled across evidence that proved giant duck-billed dinosaurs – 30 feet long and weighing several tons – roamed the semi-tropical swamps of northern Alaska around 80 million years ago.

Gary Stricker and Henry Roehler, geologists with the U.S. Geological Survey, were searching for coal when they found fossilized footprints, along with skin impressions of the prehistoric beast, along the Kokolik River in northwest Alaska, about 150 miles north of Kotzebue. Reports of the time stated the discovery was the northernmost evidence of dinosaurs ever found in the Western Hemisphere.

These dinosaurs were from the family of unarmored, herbivorous hadrosaurs, also called duck-billed dinosaurs. They were bipedal and had heavy hind limbs and tail. Hadrosaurs were amphibious, had webbed feet and could feed underwater. These big boys had no defense against carnivores – other than to escape and lay in deep water.

Hundreds of dinosaur and bird prints also were found in Denali National Park and Preserve in 2005. Researchers saw the fossilized prints in rocks that formed 65 million to 80 million years ago – during the Late Cretaceous Period.

Another major dinosaur site was discovered nearly inside the Arctic Circle in summer 2013. Scientists from the University of Alaska Museum of the North found thousands of fossilized dinosaur footprints, large and small, along the rocky banks of the Yukon River.

“We found dinosaur footprints by the scores on literally every outcrop we stopped at,” said expedition researcher Paul McCarthy with the University of Alaska Fairbanks in a statement later issued. “I’ve seen dinosaur footprints in Alaska now in rocks from southwest Alaska, the North Slope and Denali National Park in the Interior, but there aren’t many places where footprints occur in such abundance.”

The university’s museum curator told the press that such a huge and varied find was rare in this day and age.

“We found a great diversity of dinosaur types, evidence of an extinct ecosystem we never knew existed.”

So how cool is that … Alaska once was a tropical area where dinosaurs roamed and fossil evidence proves it. I love that I now can share some Alaska dinosaur history with my grandson … even if he is only 2 and just giggles at my dino noises.

The post Dinosaurs roam Alaska grasslands appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 3, 2016

Alaska’s first dog team relay run

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Amb7n...

Anchorage doctor saves Iditarod banker’s life by traveling via dog team relay in 1921.

Did you know, Balto the dog, the four-legged hero who helped deliver the diphtheria serum to Nome, wasn’t the first to make an epic medicine run in Alaska? One of Anchorage’s most respected doctors took on a similar task four years earlier.

The year was 1921. Alaska Railroad doctor John Beeson got word that the banker in Iditarod is near death’s door. Beeson didn’t hesitate to attempt a rescue but would need some help along the way.

I shared this story on last week’s episode of Alaska Story Time with Aunt Phil that aired on Monday’s CBS station KTVA Channel 11. This is the last show for a couple of months, as I am spending part of my winter this year with four grandsons (all under the age of 4) in northern California.

Here’s the link to the “rest of the story,” from this broadcast.

And here’s a link to my newly released Volume Five if you haven’t ordered your copy yet.

Hugs to all!

Laurel

The post Alaska’s first dog team relay run appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

January 4, 2016

Maternity suit ends with wedding bells

Interior Alaska miners took the law into their own hands when a dance hall fiddler skipped out of Circle City, seen here in 1914, and left a damsel in distress.

Long before marshals and judges brought law and order to Alaska’s Interior districts, miners made a point of policing themselves. When a wrong was perceived, a meeting of miners was called and both the offender and offendee could explain their sides of the matter. Then the miners would render a verdict and carry out the sentence when necessary.

Such was the case in Circle City, called the biggest log cabin city in the world during the early 1900s, when a young lady claimed “a dance hall fiddler had played his way into her heart, then waltzed away from his promise of marriage,” according to a story recounted in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner on July 20, 1966. The pregnant girl urged the miners to call a meeting.

When word went out about the damsel in distress, miners poured into town to make the matter right. They elected a judge and sheriff and issued a warrant to bring the fiddler back to Circle City for a trial.

“It was the ‘Minute Waltz’ to a tee,” the newspaper reported. “The girl told her story to appropriate murmurs of sympathy and the fiddler told his in the midst of an ominous silence.”

When all was said and done, the miners ruled that the fiddler had to pay the girl’s $500 hospital bill, give another $500 to the young lady herself and marry her as he had promised to do in the first place. They further ruled that the marriage had to happen that day by 5 p.m.

The saloons did a booming business the rest of the day, according to the newspaper account. And a “rip-roaring” wedding went off without a hitch by late afternoon.

Famous judge James Wickersham, who lived in Fairbanks at the time of the Yukon Valley’s first maternity suit, later said: “It would have taken my court two years, with many pleadings, hearings and arguments, instead of two hours, to give judgment, which in all probability would have been reversed on some technicality!”

The post Maternity suit ends with wedding bells appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 8, 2015

Archbishop of Vancouver Island murdered near Nulato

Archbishop of Vancouver Island Charles John Seghers was murdered near Nulato in November 1886.

When Archbishop of Vancouver Island Charles John Seghers journeyed down the Yukon River in November 1886, he had no way of knowing he would never return to civilization. The Catholic priest, who originally came from Belgium, had spent many years doing missionary work in Canada and Alaska.

Seghers first came to Alaska in 1873, as it was included in his diocese. He made five visits to the Great Land and set up a temporary headquarters in Nulato. In 1878, he was appointed Coadjutor Archbishop of Oregon City, according to church records. But Seghers wanted to return to Alaska.

He petitioned Pope Leo XIII to reassign him to Vancouver. The Pope granted his wish and Seghers returned to missionary work. He established missions in Juneau and Sitka and founded a school and hospital in Juneau.

Then in 1886, along with two other Jesuit priests and a layman named Frank Fuller, Seghers sailed from Victoria, British Columbia, on a journey to the upper Yukon River. After the group reached the confluence of the Yukon and Stewart rivers, Seghers left the two priests to spend the winter there as he and Fuller continued on to Nulato.

Seghers’ companions had noted changes in Fuller’s temperament during the voyage and told the Archbishop that they were concerned about him continuing the trip alone with Fuller. However, Seghers felt he must push on as eight years earlier he had promised the people of Nulato that he would return.

The Archbishop also was worried about getting established in the region before the arrival of an Anglican priest, who was rumored to already be in St. Michael. Another priest intruding into his territory should have been the least of his worries.

As the two men continued down the river toward Nulato, Seghers noticed that Fuller’s mind continued to deteriorate, as did the boat and the traveling conditions. The missionary wrote in his diary on Oct. 16: “Peculiar conversation with (Fuller) in which, for the third time, he gives evidence of insanity.”

A month later, the two men and two Native guides who had joined them at Nuklukayet spent the night at a fish camp that today is called “Bishop’s Rock.” The Archbishop was happy that night, as he believed they would reach Nulato the next day. Fuller, however, appeared agitated, paranoid and sullen, according to the Native guides.

The next morning, between 6 and 7 a.m., the men all arose and readied themselves for the final push to Nulato. For reasons unknown, Fuller fired a single shot into Seghers, who was bent over picking up his mittens. The Archbishop died instantly.

The men carried Seghers’ body to St. Michael, where he was buried. Fuller was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years in a federal penitentiary.

Many people at the time reflected that Fuller’s sentence wasn’t much of a punishment. After all, the murderer was sent to do time in the pleasant climate of San Francisco and would get free clothes and free food.

One Native from the Charley River area thought it might be nice to live in California and have all his needs met by others, as life along the Charley could be tough. The 88-mile tributary of the Yukon River flows northeast from the Mertie Mountains and enters the larger river downstream about 55 miles southwest of Eagle. It was a pretty desolate region.

He decided to murder a prospector, and when White men came along, the Native told them what he had done. He then said he was ready to go to San Francisco and live in the “skookum” (strong) house, according to an article titled “Charley River Indian Murders for Better Life” that appeared in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner on July 20, 1966.

The man did not get his wish. The White men convened a quick wilderness trial and sentenced the murderer to death. They hanged him on the spot to discourage others from thinking they might get sent to balmy California if they murdered someone.

The post Archbishop of Vancouver Island murdered near Nulato appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 23, 2015

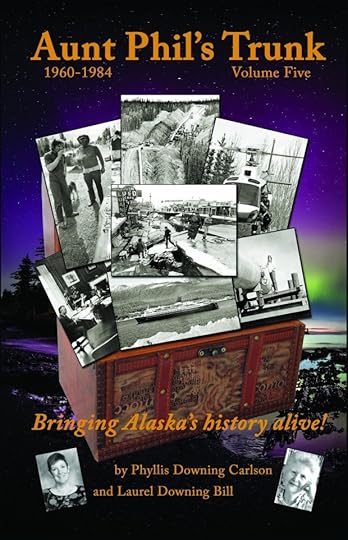

Give the gift of Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five!

Order the newly released Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five before the Christmas holiday rush!

Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five, the last book in this critically acclaimed Alaska history series, is chock full of stories from the Great Earthquake of 1964. I found true gold last year while sifting through the archives at the University of Alaska Consortium Library – firsthand accounts of people from all of the communities who lived through the quake and tsunamis that followed. Their riveting stories were recorded by a journalist two weeks after the event while the experiences were fresh in their minds.

This book also features stories about the controversy surrounding Native land claims in the Last Frontier. Stories highlight what happened between politicians, pipeline companies and Alaska’s First People that led to the largest settlement for Native Americans in U.S. history.

Volume Five shares stories about the trials and tribulations of building an 800-mile-long oil pipeline across some of the most remote and rugged country in the world. One of the stories in this book was the subject of a recent episode of Alaska Story Time with Aunt Phil on the Anchorage CBS affiliate KTVA Channel 11. Here is the link so you can watch the program:

Early trans-Alaska pipeline days

Many more entertaining short stories and hundreds of historical photographs fill the pages of Volume Five. Readers will learn how Homer residents collected millions of Betty Crocker coupons to purchase a much-needed firetruck; how Cordovans created a mythical creature to brighten up their long winter days; and how Anchoragites helped grow their local zoo by selling art done by their prolific painting pachyderm!

Click Here to order your copy of Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five in time for Christmas!

The post Give the gift of Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 11, 2015

Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five is here!

Last book in the Aunt Phil’s Trunk series is now available.

After 10 years of research, the final volume in the Aunt Phil’s Trunk Alaska history series is making its debut this week. Copies now are available on my Website for $19.95, plus shipping – Click Here to Purchase!

Volume Five features Alaska’s first 25 years of statehood. And just like the rest of the series, it is filled with dozens of short stories and hundreds of historical photographs that bring to life Alaska’s history from 1960 to 1984. Not only did the optimistic citizens of the Great Land create a government from scratch in just a few years, they also dealt with many other challenges.

Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five shares firsthand accounts of survivors who experienced the 1964 Good Friday earthquake and the devastating tsunamis that followed the 9.2 temblor. It also features stories about the discovery of “black gold” on the North Slope in the late 1960s, and how Alaska’s Native people said “not so fast” to developing that oil until their land issue was sorted out.

Alaska’s First People then banded together to fight for title to their land. They eventually won the largest settlement ever granted Native Americans, and that agreement cleared the way to begin developing Alaska’s crude.

The oil industry and the people of Alaska worked hard during the mid-1970s to build a pipeline to carry oil through some of the most rugged and remote country in the world. Men and women worked day and night to create what some called “the eighth wonder of the world.” And when finished in 1977, the 800-mile line stretched from Alaska’s North Slope to the Prince William Sound town of Valdez.

While Alaskans began enjoying the promise of a fiscally sound future for their new state in the 1980s, they also learned that evil lurked under the midnight sun. In fact, they ended the first 25 years of statehood with several mass murders. Women in Anchorage became prey when a mild-mannered baker turned into a butcher. Residents of Manley Hot Springs disappeared soon after a drifter arrived in their quiet town. And several citizens of McCarthy died when a newcomer decided he wanted to destroy Alaska’s oil pipeline.

Volume Five also highlights the top headlines that graced the state’s newspapers’ front pages between 1960 and 1984.

This final volume in the Aunt Phil’s Trunk Alaska history series debuts just in time for the 2015 holiday season – Order your copy now!

If you don’t want to go through my Website, or you live outside of the United States, please email me so we can make arrangements to get a copy of Volume Five in your hands!

The post Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five is here! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

October 27, 2015

Anchorage’s first police chief murdered

Anchorage Chief of Police John “Jack” Sturgus was gunned down in 1921 in an alley behind the Hotel Anchorage, seen here off E Street.

In an effort to curb rampant crime in Anchorage in the early 1920s, the town’s newly formed city council officially created a police department in December 1920. The council then sifted through many applications, and settled on John “Jack” Sturgus as its first chief of police.

The council told him to crack down on gambling in the railroad town in February 1921. So Sturgus spent the next several weeks patrolling the streets and attempting to halt the proliferation of gambling, along with bootleg whiskey and ladies of the evening. But less than a month after taking the job, someone shot the chief in the chest with his own gun.

Oscar Anderson, Anchorage’s first butcher, passed the 60-year-old police chief on Fourth Avenue at around 9 p.m. on Feb. 20, 1921, according to inquest transcripts and news articles of the time. Anderson noted that the chief was heading up E Street.

A few moments later, the chief lay dying at the bottom of a flight of stairs behind the Kyvig Building, which housed the Anchorage Drug store and now is an alley next to the Anchorage Hotel.

Night watchman John McNutt, who patrolled the downtown area and stoked fires for local businesses, saw what he thought was a drunken man lying in the snow in an alley off E Street at 9:15 p.m. McNutt called out, but only heard groans.

Instead of investigating, McNutt decided to inform the chief. He turned and walked to a nearby newsstand that Sturgus often frequented during his rounds. Along the way, McNutt met Mrs. Baxter, who lived in an apartment above the drugstore. He told her about the fallen man.

Mrs. Baxter went to have a look and immediately recognized her longtime friend. She later testified that she knelt beside Sturgus, and while he drifted in and out of consciousness, he called out her nickname, “Ma.” She then rushed to the Baxter’s cigar store and cried for help.

Those who came to the chief’s aid noticed his .32 caliber Colt revolver lying near him in the snow. A bullet had pierced his woolen shirt at the left pocket. His Mackinaw coat and vest were thrown open. He was cold and in pain.

They carried the gravely injured man to nearby Richter’s Hotel and Bathhouse. After a brief examination, firefighters rushed Sturgus to the hospital in their new hose wagon. As Drs. Romig, Spalding and Cannon prepared for surgery to stem the bleeding from the bullet that had lodged near his spine, Sturgus complained about the bright lights and his hands being cold. But he remained silent on repeated questions from U.S. deputy marshals Clarence Mossman and Frank Hoffman as to the identity of his attacker.

Sturgus died at 10:50 p.m. “with his lips sealed and a mystery remaining to be unraveled by the long arm of the law.”

During the official inquest, people said they either “saw the flash of a gun” or “heard the report of a gun” the night of the shooting. But no one saw any suspicious characters.

The bullet taken from the body during autopsy matched the gun found at the scene. The coroner’s inquest, conducted by Judge Leopold David on Feb. 23, concluded that Sturgus came to his death at the hands of unknown parties.

People speculated about the motive for the shooting. Some suggested the chief was killed “while endeavoring to make an arrest or while watching in the rear of the drug store for some man under suspicion.”

Other suggested that Sturgus had been “murdered by members of an illicit liquor gang,” “in revenge” because of the “activity of the marshal’s office during the past week,” and while “watching for someone conveying moonshine liquor through the alley, and when attempting to halt them, met his death,” according the various articles in the Anchorage Daily Times.

Although the city offered a reward of $1,000 for information about its chief’s death, and council members pledged another $950, the murder has never been solved.

Sturgus is buried along the iron fence that faces Cordova Street in the Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery. But some say his spirit still lingers in the alleyway where he was shot.

The post Anchorage’s first police chief murdered appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

October 12, 2015

Big Sickness Arrives in Alaska in 1918

The influenza pandemic of 1918 devastated the Native village at Nome.

During the spring of 1918, as World War I veterans returned to their home countries, flu spread across the world and sickened many people. By that fall, the virus had mutated and become a mass killer.

It preyed on the young and healthy. A dull headache signaled the beginning. Then came chills so intense that no amount of blankets warmed the body. As the fever climbed, delirium followed. Lungs filled with fluid. Pneumonia took over.

Sometimes it took days. Sometimes hours. But nothing could stop the relentless march toward death for many. And even though Territorial Gov. Thomas Riggs did everything in his power to keep it away from Alaska’s shores, the killer still came.

Juneau’s first reported case came on Oct. 14, and soon it had spread along the coast. Juneau officials advised people not to congregate in groups, which meant staying away from churches, schools, social functions and pool halls.

The panhandle came through the epidemic better than areas farther north and west, because it had services and physicians who set up quarantine areas, emergency hospitals and buried the dead immediately. It also had help from professionals in Seattle and San Francisco.

When passengers from the S.S. Victoria, the last ship of the season from Seattle, docked in Nome, the killer disease enveloped the Seward Peninsula. Before leaving Seattle, the ship’s passengers and crew had been checked by three physicians, separately and independently, to assure that no one who exhibited symptoms would be traveling.

And when the Victoria arrived in Nome on Oct. 20, all those who came ashore were quarantined in the hospital for five days and all freight and mail were fumigated. No one showed any signs of influenza.

But within days, Alaska Natives were sick and dying. Few escaped infection. It became known as the “big sickness,” and in a single eight-day period, 162 had died. Earlier epidemics of smallpox, measles and typhoid fever had instilled a paralyzing fear in Alaska’s Native population.

“They believed in the spirit of death and feared that, if a person died in their home, that spirit would claim them next,” wrote Gay and Laney Salisbury in their book, The Cruelest Miles. A death often caused family members to panic and flee, which helped to spread the diseases.

“Some Eskimos, hounded by superstitious horror, fled from cabin to cabin, infecting increasing numbers with disease and panic. The temperature fell below freezing, and when rescuers broke into cabins from whose chimney came no sign of smoke, they found many, sometimes whole families, who had been too sick to renew their fires and who had frozen to death,” wrote Alfred Crosby in his book, America’s Forgotten Pandemic.

Thousands of people died, leaving many orphans left behind. The Bureau of Education opened orphanages to care for these homeless children, including one at Kanakanak, near Dillingham, and one at White Mountain, near Nome. Rev. Bellarmine LaFortune, a Jesuit priest, also started a private home for children at a hot springs 90 miles east of Nome that had been a getaway for miners in the early 1900s. When the roadhouse and resort at Kruzgamepa Hot Springs burned in 1908, the property was abandoned.

LaFortune named his children’s home Pilgrim Springs. He persuaded Ursaline sisters to join him in the care and nurturing of the orphans, and soon they even had crops of fresh vegetables flourishing near the warm waters.

The home, which included seven buildings on site, became a beloved institution among both Natives and Caucasians in the area, according to Alaska historian Stephen Haycox. By 1925, about 70 children lived at the home.

But when World War II necessitated a military airfield at Nome, many Natives left the hot springs to assist in its construction. The orphanage closed and LaFortune died in Fairbanks in 1947.

The post Big Sickness Arrives in Alaska in 1918 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

September 28, 2015

Alaska’s first serial killer strikes

The fine print reads:

“Krause is five feet, ten inches in height, about forty-five years of age, heavy set, broad shoulders; walks with shoulders back, with short quick steps; has sandy hair, curly; bald in front, blue eyes, a heavy red mustache; may now be shaved. General sandy complexion, and is pale from confinement; weight about 200 pounds; wore a dark-blue suit of heavy material. Is of very powerful build and has large muscular hands.”

Between 1912 and 1915, a number of single, unattached men mysteriously disappeared in Southeast Alaska. The few law enforcement officials in the territory were baffled, but a suspect finally emerged in the fall of 1915.

A Petersburg man named Edward Krause, who’d run for the Territorial Legislature as a Socialist Party candidate in 1912, represented himself as a U.S. Marshall to officials at the Treadwell Mine in Douglas in mid-September. Krause told the bosses that he had a court summons for a mine worker named James Christie, according to Alaska State Troopers’ 50 Years of History.

Christie departed with the bogus lawman and was never seen again.

The managers at the mine started an investigation of their own into Christie’s disappearance. When it was learned that Krause also was identified as the last person to see a missing charter boat operator out of Juneau, a warrant for his arrest was issued on charges of impersonating a federal officer.

Krause escaped the clutches of the law in Ketchikan and jumped on board a steamer heading for Seattle. But a savvy passenger, who had seen posters plastered by the Treadwell Mining Company, recognized him as the man with a bounty on his head. When the steamer docked in Puget Sound, police detectives were waiting.

A search of Krause’s possessions turned up incriminating evidence including forged documents, bank accounts and real estate transactions, which tied him to not only the recent disappearances in Juneau, but to the disappearances of at least eight other men, too.

After Krause was returned to Alaska, his true identity surfaced. Krause was really Edward Slompke, who’d served with the U. S. Army at Wrangell in 1897. By using forged documents, and stealing a military payroll, he deserted from the 12th U.S. Infantry in 1902 when his regiment was sent to China to participate in the Boxer Rebellion.

A yearlong investigation, which used the services of the newly formed Federal Bureau of Investigation, as well as the U.S. State Department, revealed a series of disappearances and an intricate pattern of forged property transactions.

Authorities found that over the years Krause recovered the assets of the murdered men. They also learned that a “murder gang,” run by Krause at Petersburg, was involved in additional mysterious disappearances. However, none of Krause’s victims were found, so authorities had to rely on strong circumstantial evidence to try him.

His first murder trial, of Juneau charter boat operator James O. Plunkett, began in July 1917. Based on the overwhelming circumstantial evidence, the jury found Krause guilty of first-degree murder. His conviction was affirmed by the U.S. Court of Appeals in San Francisco, and Krause was sentenced to die by hanging at Juneau.

After sawing through the bars of his cell, Krause escaped from the Juneau Federal Jail two days before his slated execution. That launched the most widespread manhunt in the territory’s history.

Fishing fleets in every community in Southeast mobilized to block Krause’s escape out of Alaska. The mines on both sides of Gastineau Channel closed down, and 1,000 miners joined in the hunt. While house-to-house searches were conducted, Governor Strong announced his $1,000 reward, “dead or alive.”

A few days later, a homesteader claimed the reward. He’d killed Krause after the fugitive stepped out of a stolen skiff onto the beach at Admiralty Island.

The post Alaska’s first serial killer strikes appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

September 14, 2015

Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five coming soon!

The fifth volume in my Aunt Phil’s Trunk Alaska history series went off to the printers last week. If all goes as planned, it will be available before Thanksgiving!

This 448-page book, which will sell for $19.95, completes the series and features the first 25 years of Alaska’s statehood. Just like the first four books in the series, Volume Five (1960-1984) is filled with many short stories and more than 350 historical photographs that bring the history of the Last Frontier to life.

Stories in Volume Five include first-hand accounts of survivors who experienced the Good Friday earthquake of 1964, tales from the trans-Alaska oil pipeline building days and highlights of some “highs” and “lows” during those first 25 years as a state.

I will send out an announcement as soon as copies of Volume Five are available for sale!

The post Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Five coming soon! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.