Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 7

January 16, 2015

Alaska troublemakers earned one-way ticket south

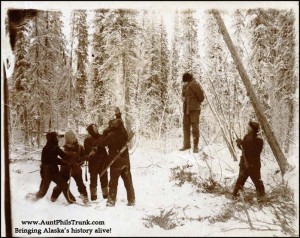

As the Territory of Alaska grew up, the people in the Great Land distanced themselves from frontier justice – as in the photo here – and turned to sending criminals back to the Lower 48 with one-way tickets south.

An abundance of gamblers, con men and thieves made their way north following the discovery of gold in the Klondike in the late 1890s. And with no official lawmen to take care of evildoers, miners took the law into their own hands and dispensed frontier justice. Murder was punished by hanging; stealing meant a sound whipping or banishment.

After Alaska became a territory in 1912, Alaskans turned away from hanging and whipping offenders, but they kept their tradition of banishment to deal with “undesirables.” When rascals could not, or would not, find legal employment and instead led lives that included drinking alcohol to excess and crime, they were given one-way tickets back to the “Lower 48.”

Referred to as “blue ticketing,” this method of removing ne’er-do-wells from Alaska society often was used by police officers. The miscreants were given a choice of a trip to jail or a one-way ticket south. The accused usually chose the ticket and then was escorted via train to Seward to catch a steamship bound for Seattle.

The term “blue ticket” stemmed from the color of steamship passes at the time. Sometimes concerned citizens pooled their resources to purchase a ticket for a scallywag, other times businessmen donated funds. Once a person was issued a blue ticket, his or her name was put on a special list that prohibited a return to the territory by boat.

This system worked pretty well, according to sources that lived in Alaska at the time. Once in a while a blue-ticket passenger would sell the ticket in Seward. Then he’d use the money to buy alcohol and resume the conduct that got him the ticket in the first place. But overall, it proved an effective way to rid the territory of troublemakers.

The practice of blue ticketing eventually died out. And good riddance, some attorneys today would say, as the procedure did not offer the offenders due process and probably was unconstitutional.

However, a form of blue ticketing continues to live on in several Alaska villages. Although rare, village councils have been known to banish persons whom they believe are dangerous to their communities.

One of the most recent instances involved the village of Tanana. The Tanana Village Council, the Athabascan Indian tribal authority in the northern village of 250, took steps to expel two men who contributed to the homicides of two Alaska State Troopers in 2014.

And when a man suspected of drug dealing stepped off a plane in Sand Point last year, residents of the community surrounded him and told him he was not welcome in their village. They handed him a return ticket to Anchorage and made sure he got back on the airplane.

Those living in the Yup’ik Eskimo village of Akiak in southwest Alaska also voted in April 2013 to banish a man for bootlegging and drug dealing.

Village councils rely on the state to enforce the banishments when they are handed down, and the Alaska Department of Law appears to unofficially support the practice.

The post Alaska troublemakers earned one-way ticket south appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

January 10, 2015

Alaska Native Brotherhood organizes in 1912

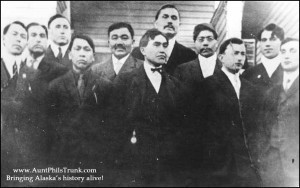

Alaska Native Brotherhood founding fathers in 1912, from left: Paul Liberty, James Watson, Ralph Young, Eli Kalanvok (Katinook), Peter Simpson, Frank Mercer, James C. Jackson, Chester Worthington, George Fields, William Hobson, and Frank Price. Not pictured are Seward Kunz and Marie Moon Orsen.

After decades of oppression by Russian fur traders, and then American interests, the Natives of Southeast Alaska decided it was time to organize into a united voice to change the way people perceived them and to better their circumstances in a land that their ancestors had inhabited for thousands of years. A dozen men and one woman from Sheldon Jackson Training School (later known as Sheldon Jackson College) met in 1912 and wrote a charter for what became known as the Alaska Native Brotherhood.

For generations white people had deemed these young people and their forefathers as savages. They were not citizens of Alaska, could not vote on issues that affected them, could not own land and had no civil rights. Most Americans viewed Alaska’s Natives at the bottom of the ladder of civilization.

When the gold rushes of the late 1800s began, Alaska’s first people were not allowed to stake mining claims, either, because the Mining Act of 1874 stated that only two groups of people could do so: American citizens or immigrants in good standing – which usually meant white immigrants.

Also, more often than not, white hire preferences were in place for jobs in businesses, government and communities. And if a Native did land a job, he received a lower wage than a white man doing the same job.

Other inequities existed, too. Natives could not testify against a white person in civil courts, Native children could not attend white schools, and much of Alaska’s society was segregated with “whites only” signs. Sometimes entire communities were off limits to Alaska’s Native people.

After the United States “purchased” Alaska from Russia in 1867, some officials wanted to move the Natives out of this lower status. To that end, the Commissioner of Education banned Native languages in schools and declared an English only policy in 1884 – which is perhaps why the founding fathers of the ANB specified that its membership must speak English.

The original charter for membership into the Alaska Native Brotherhood also featured other stipulations to promote white American culture among the Natives, including that its members be Christian, take a sobriety oath, not participate in potlatches and dedicate their lives to service.

These forward-thinkers of the ANB knew that the only way to better the Natives’ situation in their own land was to get an education and play the game of the white man. They learned to organize and soon pursued the right to become citizens of the United States, pushed the issue of Native land claims and promoted the social, civic and educational well being of Alaska Natives.

After only three years, the Alaska Native Brotherhood achieved passage of the Native Citizen Act. It was limited, however, as a Native could only become a U.S. citizen after he passed a literacy test, pledged to move from his ancestor’s ways to Western ways and had the written endorsement of five white men. It wasn’t until the 1940s that Native citizenship, without restrictions, was assured.

The land claims issue would take many more years, but finally was settled with the passage of the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

Although the ANB has been largely a Southeast Alaska organization, many other groups were formed because of it that have been instrumental in moving Alaska’s Native people from second-class citizens to leaders who are helping to shape the future of the 49th state.

The post Alaska Native Brotherhood organizes in 1912 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

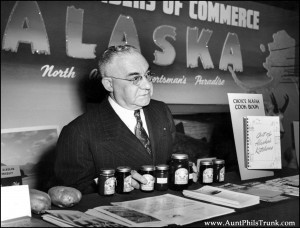

January 5, 2015

Alaska establishes boroughs

William A. “Bill” Egan, convention president and later governor, served as the Valdez delegate to Alaska’s Constitutional Convention and helped to establish boroughs as the intermediate government between municipalities and the state.

Alaska officially became the 49th state in the Union 56 years ago this month. Gov. William A. Egan was sworn in on Jan. 3, 1959, and the new state got down to the business of figuring out how to govern itself. The job was made easier, however, because many diligent Alaskans had meet three years earlier and created a road map for the newly elected officials to follow.

The participants of that convention found one of their most difficult problems to be the intermediate government between municipalities and the state. Their solution was the creation of a unit known as the “borough.”

“It’s a county with a New York name,” a legislator once said.

Most delegates to the Constitutional Convention did not want to slice the territory into a large number of counties as in other states. Valdez delegate William A. “Bill” Egan listed “make-up of the political subdivision” as one of the four major issues to be solved.

And opinions on how to do that ranged widely.

“The issue of the basic composition of local government is a thorny one which must be met,” said then-delegate to the U. S. Congress Sen. E.L. “Bob” Bartlett when the convention opened.

The problem was turned over to a local government committee headed by John Rosswog of Cordova. Serving with him were John Cross of Kotzebue, Victor Fischer and Victor Rivers, both of Anchorage, Eldor Lee of Petersburg, Maynard D. Londborg of Unalakleet, and James P. Doogan of Fairbanks.

“The problem is to get a modern local government without duplication, one that will not be burdensome to the people,” Rivers said a few weeks later. “The tax structure, for example, should be equitable and overlapping.”

The committee called in Dr. Vincent Ostrom of Oregon State College and Stanford to assist in formulating a “workable relationship between the new local government unit and the existing cities within its jurisdiction.”

Two days later, the committee recommended the convention “divide the future states into cities and rural municipalities, eliminating counties.”

With the new form of government generally conceived, the committee started looking for a name for the unit. While other states used towns, counties, shires, parishes, boroughs and bergs, members of the committee initially felt the identity should be one of Native derivative.

One suggestion combined “nuna,” meaning inhabited area, with “puk,” which means big, to call the units “nunapuks.” But borough eventually won out after much debate.

At its third reading on Jan. 31, 1956, the committee decided “all local government powers of the state of Alaska shall be vested in boroughs and cities.” Approval came only after a vote in which 16 delegates voted for the word “county” and 21 for the word “borough” adopted the local government provision.

As adopted, Article X spelled out “that the entire state shall be divided into boroughs, organized and unorganized,” with the Legislature to “classify boroughs and prescribe their powers and functions.”

There was probably more speculation and less consensus on the future of the borough system under the Alaska Constitution than on any other single subject connected with local government. But the writers of the state’s Constitution were united on its purpose, “to provide for maximum local self government with a minimum of local government units and duplicating tax-levying jurisdictions.”

And 56 years later, the system of boroughs still is working well for the young state.

The post Alaska establishes boroughs appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 27, 2014

Russian Orthodox Christmas Celebrated January 7

A Russian Orthodox priest blesses water that will become holy water in St. George in the Pribilof Islands following the celebration of Russian Orthodox Christmas in the early 1900s.

While most people celebrated Christmas on Dec. 25 last week, many Alaskans from the Pribilof Islands to Nikiski to Sitka will celebrate next week. The Russian Orthodox Church still observes the Julian calendar, and each day on that calendar occurs 13 days after the corresponding day on the modern Gregorian calendar – so January 7 is their day of rejoicing the birth of Jesus.

Alaska’s Native people and the Russian Orthodox Church go back to the mid-1700s when Russian fur traders first arrived. These men were from a culture that believed in Christianity and they shared their beliefs with the Natives. And it wasn’t long before Russian Orthodox priests began arriving in the vast land.

The first Russian Orthodox missionaries came to Alaska in 1794. These priests believed in learning the language and culture of Alaska’s people, and then teaching them in their own dialect. They also shared their customs for celebrating Christmas.

Christmas is more of a religious festival in Orthodox communities. It’s traditional to light candles in honor of Jesus, as light of the world. Then people walk in procession to a sea, lake or river where a priest will bless the water as part of an outdoor ceremony, as in the photo above. Some people will take the blessed water back to their homes.

Christmas is a time of reflection and renewal, as well as a time to affirm the bonds of friendship and family. Villagers celebrate for an entire week with church services, fireworks and special foods.

Part of their week long celebration includes “starring,” which also is called slaviq. People make huge “stars of Bethlehem” out of wood, crepe paper and tassels and then twirl these stars as they travel from home to home and village to village.

They sing songs outside of a house and then are invited inside to sing carols – sometimes in English, Russian, Slavonic, Yup’ik, Alutiiq, Dena’ina and other Native languages. The group then feasts on food the family has prepared.

After eating, the family joins the carolers and they all go off to another house to repeat the ritual until late at night. Those chosen to be the last home on the celebration circuit will have a huge houseful of guests!

Aunt Phil’s Trunk wishes a very merry Christmas to all our Russian Orthodox Alaska history fans on January 7!

The post Russian Orthodox Christmas Celebrated January 7 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 23, 2014

Airfield emerges from Anchorage wilderness

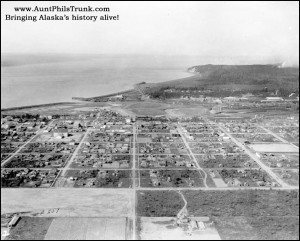

In 1923, Anchorage residents cleared land between Ninth and Tenth avenues so newfangled flying machines could land near town.

More than 90 years ago, Anchorage residents prepared to usher in a new form of transportation. Bush pilots, flying open-cockpit planes, needed a place to land, so the community dedicated an area “outside” of town as its first airstrip.

Townspeople turned out in force in the spring of 1923 to clear 16 acres of land between Ninth and Tenth avenues and C and L streets, which had served as a firebreak to keep fires from coming into Downtown Anchorage from the south. The May 27 issue of the Anchorage Daily Times reported the event:

“Men whose hands had not been soiled by anything heavier than a pen for many years, grappled the mattock or the axe and shook the kinks out of their flabby muscles. Ladies with rakes and other implements cleared away the small debris while others piled it upon the small mountain of stumps ready for the torch.”

The airstrip was put to use for the first time a year later, when 24-year-old barnstormer Noel Wien took off in his J-One standard open-cockpit biplane on July 6 and followed the railroad north. Although the gutsy aviator encountered thick smoke from wildfires near Healy that hampered his visibility, he landed safely at Weeks Field in Fairbanks.

Anchorage’s first local airline made the new airfield home soon thereafter. Anchorage Air Transport Inc., formed by Art Shonbeck, Oscar Anderson, Gus Gelles and Ray Southworth in 1926, used the strip for several years with its chief pilot, Russ Merrill, making countless successful take-offs and landings.

But some aviators, like well-known bush pilot Merle Sasseen, also had a few mishaps.

Sasseen, who had survived three crashes in as many months, two of which while landing on the “runway” at the out-of-town field, had to fill out a detailed federal report to describe his last accident. The final, crucial question on the form asked him: “General ability as a pilot?”

While most pilots lost no time responding to the ego-challenging question and filled in the blank with “Excellent,” Sasseen was weighed down with chagrin at his third aviation smashup in a row. He studied the question.

“General ability as a pilot?” he asked.

Then, after scratching his head, he wrote: “I used to think I was pretty good, but lately I’ve begun to wonder.”

Bush pilots used what’s now called the Park Strip, or Delaney Park, as an aviation field for about seven years. It then became the town’s first golf course. But even after the completion of Merrill Field in 1929, spring breakup occasionally forced pilots to use the more solid town strip.

The post Airfield emerges from Anchorage wilderness appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 15, 2014

Alaska’s Operation Santa Claus brings smiles

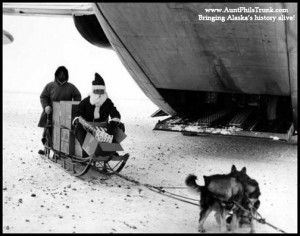

Santa Claus and his sled loaded with gifts come dashing from the back of a C-123 airplane at Savoonga on St. Lawrence Island in 1963.

The Alaska Air National Guard has been putting smiles on faces from Savoonga to Ruby to Barrow at Christmas time for 59 years. Its Operation Santa Claus program, which delivers gifts and goods to many Alaska villages, began in 1956 after the Guard received a request from St. Mary’s Mission for toys for their children.

Guardsmen heeded the call for this Yup’ik Eskimo village, located about 90 air miles north of Bethel. They asked for donations of new and used toys from the residents of Anchorage and were humbled by the generosity of the community.

A few weeks before Christmas, Santa Claus and all the gifts were loaded aboard an Air Guard C-123 airplane. Upon arrival at the tiny Southwest Alaska village, Santa and the airmen were greeted with loud cheers and huge smiles.

This was the first time many of the children had seen Santa Claus in person. Some eagerly climbed onto his lap and whispered their wishes into his ear. Others were too shy and didn’t know what to make of this jolly old man dressed in red.

Santa then passed out presents and enjoyed a small snack while watching the village’s basketball team handily defeat the Air Guard all-stars.

Operation Santa Claus was such a success, that it continued its flights with gifts to the children of St. Mary’s into the early 1980s. It added more stops when other villages, schools and groups invited Santa into their communities. Operation Santa became a joint mission between the Air and Army National Guard, and to date has served tens of thousands of Alaska’s children, according to the Guard’s Website.

Santa traded in the C-123, though, and now relies on the sturdy C-130 Hercules to carry him and his presents, books and school supplies to villages across Alaska. He also has help sometimes from National Guard members who deliver gifts to youth and elders with a Blackhawk helicopter.

There was a rumor going around that Santa’s reindeer get a bit jealous because they are not invited on these grand adventures, but that story has not been verified. I’m thinking they probably don’t, however, as they stay busy enough eating lots of lichen and resting so they will have the energy needed to haul the big guy and his sleigh all over the world on Christmas Eve.

Ho, Ho, Ho – Merry Christmas to all from Aunt Phil’s Trunk!

The post Alaska’s Operation Santa Claus brings smiles appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 8, 2014

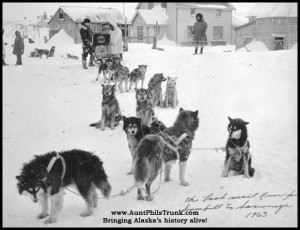

The last sled dog mail service

Dogs gear up to haul the U.S. mail on its last sled run between Gambell and Savoonga in 1963.

The explosion of airplane competition didn’t stop Chester Noongwook of St. Lawrence Island from continuing his sled dog mail service run until 1963. His was the last mail delivery of its kind in the country.

Wien Airlines established the first commercial airplane base on St. Lawrence Island at Gambell and built a landing strip at Savoonga. The company took over the mail-carrying duties for the U.S. Post Office. But Noongwook was retrained on a supplemental basis whenever the planes couldn’t get through. For six years, Noongwook never once let bad weather keep him from carrying the mail between Gambell and Savoonga.

He had the last laugh on the planes that superseded him, too. A modern airplane, delayed by bad weather, caused the young Eskimo to be late for what may have been one of the most important occasions of his life – receiving an award from the post office upon his retirement.

Noongwook, who made his weekly 100-mile runs sometimes in blinding snowstorms where visibility was about 10 feet and temperatures ranged to 40 degrees below zero, was four hours late for a special ceremony in Fairbanks when fog prevented his airplane from departing Nome.

He didn’t know why he was to report to Fairbanks, and when he finally arrived at that city, he was overwhelmed when presented with a large, framed certificate as movie cameras began to roll and flashbulbs clicked all around him. After the presentation of the special award – the first of its kind – for outstanding service as the last sled dog mail carrier, Noongwook enjoyed dinner with many high-ranking government officials.

With that ceremony, the curtain was drawn on an exciting, dramatic era when dogs carried the mail in Alaska. It seems fitting to close that chapter of Alaska’s history with a poem by Alaska Nellie Lawing. She and her dogs had carried mail and knew from firsthand experience that:

The Mail Goes Through

It matters not how rough the trail,

You must fight it through when you take the mail.

It matters not how the north wind blows

How bitter cold or how hard it snows.

Remember, it’s not how or what you do

The important thing is – the mail must go through.

Do your best to succeed – you dare not fail –

For you must mush on when you take the mail.

The post The last sled dog mail service appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 2, 2014

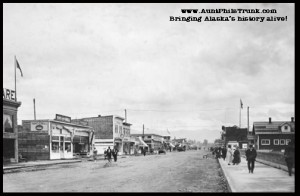

Happy Birthday, Anchorage!

By 1920, Anchorage residents had built 12-foot-wide concrete sidewalks along Fourth Avenue, the town’s main street.

Although railroad workers began laying tracks along Ship Creek in 1915, technically speaking, Anchorage was born in November 1920. So this month marks its 94th year as a city. According to information gleaned by the League of Women Voters many years ago, it was eligible to become a first-class city because it had a population in excess of 400 – provided that two-thirds of the voters were ready to assume responsibilities of city government for its 2,500 residents (it boasts a population of more than 300,000 now).

A group of interested citizens filed a petition with the U.S. District Court at Valdez, which was the headquarters of the Third Judicial Division. The petition requested that a special election be held to determine the wish of the majority in the former Tent City.

There was some organized protest during a hearing on the matter, so Judge Frederick Brown ordered an election. That ruling wasn’t to be the last that Judge Brown would render on the issue, however. The judge would be called upon again after the citizens of Anchorage cast their ballots to decide the question.

The election returns showed a count of 328 votes for incorporation and 130 votes against. Another 85 ballots had been stuffed into the ballot box blank. If all 543 ballots were considered cast, then the percentage of those for incorporation would miss the two-thirds mark necessary.

After careful consideration, Judge Brown ruled the 85 blank votes were to be ignored. He decided it was as if those voters had not been to the polls at all and that Anchorage had voted itself into incorporation.

Anchorage became a city on Nov. 23, 1920, under the mayor-council system with Leopold David serving as its first mayor.

Boundaries for the new city stretched from one-half mile off shore in Cook Inlet to East G (now Gambell Street) and from 11th Avenue to Government Hill, including a small section that is now inside Fort Richardson.

The city received restricted patents for some properties reserved for recreation or municipal purposes, including the City Hall block, a school block between Fifth and Sixth avenues and E and G streets, the cemetery, the baseball park, the playground on M Street between Ninth and 10th avenues and the golf course between Ninth and 10th avenues from Gambell Street to the Inlet.

Some say the golf course was originally planned as a firebreak between the city and the wilderness. Other sources say that during the early days of World War II, residents erected barricades of all sorts on the strip to prevent enemy planes from landing.

Primarily a railroad worker’s town, Anchorage also became a trading center for miners, trappers and homesteaders who traveled via train, plane and dog sled to stock up on supplies. The highway connecting Palmer and Anchorage, built by the Alaska Road Commission, wasn’t completed until 1939.

The post Happy Birthday, Anchorage! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 26, 2014

ZJ Loussac – Down but never out

Philanthropist Z.J. Loussac, seen here, supported his community of Anchorage.

Z.J. Loussac was broke when he arrived in the United States from his native Russia in 1901. The 18-year-old boy, a refugee from the Tsar’s secret police, landed in New York City and found a job running errands for a drug store in a Russian neighborhood. He worked there long enough to learn basic English – enough so he could understand the glowing tales he heard of Klondike gold.

When a man emptied large nuggets from his pockets to prove his stories of Yukon wealth, it was enough for Loussac. Since the streets of New York weren’t paved with gold, as so many immigrants had been led to believe, Loussac decided to go where he thought he could pick up gold by the handful.

Twice he sought riches and failed – once in 1903 and again in 1907. The North drew him back again, though, and in 1916, he landed in a new tent city on Cook Inlet. The third time proved to be the charm for Zachariah J. Loussac, for he got in on the ground floor of the town that would grow to be Alaska’s largest city.

He soon made a reputation for himself as an up and coming merchant. He opened a drug store and advertised it as having “what you want when you want it.” He put in a writing desk and supplied it with paper and envelopes free to anyone who wanted to write a letter home.

Each succeeding year proved better than the last for Loussac. By 1939, he was out of debt for the first time since 1901. The mushroom growth of Anchorage during World War II was the turning point in his business – he found money “rolling in by the bushel baskets!”

He then threw himself into a civic career and was elected to three terms as mayor of Anchorage. Ben Boeke, who was city clerk during Loussac’s terms, said he was a “progressive mayor,” who pressed for street paving and utility expansion.

In 1946, Loussac set up the Loussac Foundation, funding it with half his wealth, which he dedicated to the recreational, cultural, scientific or educational activities in the Anchorage area. It was hailed as the “most generous gesture ever made by a living Alaskan toward his fellow Alaskans.”

“I hope it will set an example for others who came here to Alaska and accumulated some wealth,” Loussac said. “I hope it will encourage them to keep the wealth here and make Alaska a better place to live.”

Loussac died in March 1965 at the age of 82.

The post ZJ Loussac – Down but never out appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 20, 2014

Seattle ship swipes totem

This Tlingit-carved totem pole, stolen from a seaside village near Fort Tongass in Southeast Alaska, is a landmark in the city of Seattle, Wash., in 1900.

Of the multitude of steamships that plied the waters from California to Point Barrow during the late 1800s, one has the dubious distinction of being what some may call a “pirate ship.” The City of Seattle, which sailed from Seattle to Skagway and points in between, played a major role in spiriting a totem pole out of Alaska.

As the story goes, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce had wanted a totem pole to erect in Pioneer Park in downtown Seattle. However, those who carved the magnificent monuments only came from the tribes of northern Vancouver Island, the Queen Charolette Islands, and the adjacent tribes in British Columbia and Alaska.

In the summer of 1899, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer put a delegation onboard the City of Seattle to sail to Sitka to see if they could find a totem pole suitable for the park. Since most of the totems by this time were stationed in Indian burial grounds, the delegation’s mission was indeed delicate.

After a brief stay in Alaska’s ancient capitol, guests returning to the ship were advised by the purser not to believe anything they heard and only half of what they saw from that time forth.

After finishing her business in the port of Sitka, the City of Seattle sailed out a short distance and then anchored in a stream. Passengers watched as the crew lowered one of the ship’s boats into the water and rowed ashore. Later, third mate R.D. McGillvery described what happened:

“The Indians were all away fishing, except for one who stayed in his house and looked scared to death. We picked out the best looking totem pole. I took a couple of sailors ashore and we chopped it down – just like you’d chop down a tree. It was too big to roll down the beach, so we sawed it in two.”

Members of the “Committee of Fifteen” paid McGillvery $2.50 for his effort to cut down the totem, which belonged to the Raven Clan. It was carved in 1790 to honor a woman called Chief-of-all-Women who’d drowned in the Nass River.

On Oct. 18, 1899, the 60-foot totem was unveiled in Seattle’s Pioneer Square and “greeted by cheers of a multitude of people.”

The Tlingits demanded $20,000 for the return of the stolen totem, but settled for $500, which the Seattle Post-Intelligencer paid.

The original totem stood proudly in Pioneer Square until a careless smoker tossed a cigarette butt against its decaying base in 1938. The city removed the original totem and replaced it in 1940 with a replica carved by the descendants of the original totem’s carvers.

The post Seattle ship swipes totem appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.