Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 11

March 24, 2014

Exxon Valdez spills oil 25 years ago

Following the grounding of Exxon Valdez (the larger of the two ships seen here) on Bligh Reef on March 24, 1989, its oil cargo was pumped into the Exxon San Francisco. It is estimated that 11 million gallons of crude seeped into Alaska’s Prince William Sound before the tanker was emptied.

One of the worst disasters of our lifetime happened 25 years ago this week in the pristine Prince William Sound. Under the command of Capt. Joseph Hazelwood, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground and spilled millions of gallons of crude into Alaska waters.

Hazelwood placed a call to the U.S. Coast Guard at 12:27 a.m. on March 24, 1989, to report that he had diverted course from normal shipping lanes to avoid icebergs in the Sound. At 12:04 the Exxon Valdez had bashed into Bligh Reef. The captain said several holes had been ripped in the bottom of the single-hulled tanker.

“We’ve fetched up hard aground, north of Goose Island off Bligh Reef and, evidently we’re leaking some oil,” Hazelwood said.

Leaking some oil was an understatement. It’s estimated that 11 million gallons of crude dumped into the Sound, covering birds, otters and other wildlife with its black sheen. It is considered one of the worst human-caused environmental disasters in history.

The remote location, and lack of safety plans at the time, made response efforts difficult. The seeping oil, which had flowed through the 800-mile-long Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline from Prudhoe Bay and been loaded onto the ship at Valdez the day before, eventually covered 1,300 miles of coastline and 11,000 square miles of ocean.

Despite extensive cleanup efforts, including the use of dispersants and solvents, booms and skimmers and high-pressure hot water, less than 10 percent of the oil was recovered. A NOAA study later showed that more than 23,000 gallons of oil remained in the sandy soil along Alaska’s coastline as of 2010, breaking down at a rate less than 4 percent per year. Experts say it will take at least 30 years for the habitat to fully recover.

Estimates show between 100,000 and 250,000 seabirds died as a result of the spill, and about 2,800 sea otters, 12 river otters, 300 harbor seals, 247 bald eagles, 22 orcas and countless salmon and herring perished, as well.

For weeks and months thereafter, the disaster made news across the world. Hazelwood was later found to have been drinking that evening, which made him an easy target for those looking for someone to blame. Although he was asleep in his bunk at the time of the accident, he was in command of the ship so was ultimately responsible for the ship’s third mate, who actually was at the helm at the time.

But other factors played a part in the environmental catastrophe, including an industry-wide lack of giving adequate rest to tanker crews, a third mate who failed to properly maneuver the vessel and malfunctioning radar equipment that had not been operational for more than a year leading up to the accident. If working, the ship’s radar would have indicated to the third mate an impending collision with Bligh Reef. It would have detected the “radar reflector” placed on the next rock inland from Bligh Reef to keep boats on course.

Although Alaska communities still have not fully recovered from this disaster, and plaintiffs against Exxon are still waiting for settlements, the accident did result in new marine pollution prevention rules. In the aftermath, Alaska Gov. Steve Cowper issued an executive order requiring two tugboats escort each loaded tanker from Valdez out through Prince William Sound. And Congress passed legislation that requires all tankers to be double hulled by 2015.

The post Exxon Valdez spills oil 25 years ago appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

March 19, 2014

Miners stampede to Nome during Klondike Gold Rush

Prospectors sift through sand looking for gold along the beaches of Nome in 1903.

Nome’s Caucasian claim to Alaska’s history goes back more than 100 years after three greenhorn Scandinavians stumbled across gold in Cape Nome in 1898. Swedish tailor Eric Lindblom, 41, who worked his way north as a deck hand on a whaling ship, Norwegian Jafet Lindberg, 24, who got free passage by pretending to be an experienced reindeer herder, and Swedish coal miner John Brynteson, 27, all ended up in Nome because the promising land in the Klondike already had been claimed.

Their discovery led to America’s last big placer gold rush and yielded $3.5 million in gold by 1900. During the next two decades, it brought in another $80 million. The Nome stampede gave amateurs a chance to make fortunes, as well as provided a second chance to prospectors who’d failed elsewhere.

Following the Scandinavians’ find, thousands of people left Dawson and headed to Nome. The town filled with shady characters and hardened criminals who didn’t pay much attention to American mining laws. By July 1899, almost every potentially valuable claim had been jumped at least twice and some had multiple claimants.

Confusion and unrest reigned among the community’s 3,000 residents. Until a soldier, assigned to a small detachment sent up from St. Michael to guard the settlement, and an old prospector from Idaho found gold in the sands of Nome’s beaches.

Known as the “Poor Man’s Gold Rush,” the discovery of gold on Nome’s beaches meant that anyone could work the public property without staking or recording claims. The area’s population swelled to around 20,000 by 1900, and according to an article in the Nome News, the post office hired 23 clerks to handle 546,000 letters between June and August.

Veteran prospector E. C. Trelawney-Ansell later reported:

“Nome was different, it was a place where the creeks and the town itself filled with thousands of cheechakos who had never known the hardship of the trail and few if any other hardships. Worse still, the camp and surrounding country was filled with gamblers, cutthroats and murderers of the worst kind.”

With more than 60 saloons, dozens of criminals, a few hundred prostitutes and dishonest officials, including an embezzling postmaster, a tax assessor who went to prison for illicit financial dealings and a federal judge who made crooked rulings, it’s not surprising that robberies, murder and mayhem flourished in Nome.

The Poor Man’s Gold Rush played itself out by the end of 1900, and after a fierce storm destroyed the business district and the beach mining operations, thousands left on steamships heading south. Some stayed behind and continued on with placer mining, but by 1910, Nome’s population had dropped back to around 2,000.

The post Miners stampede to Nome during Klondike Gold Rush appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

March 11, 2014

Sled dogs lead the way through Alaska’s history

Sled dogs have an illustrious history in the North Country, from the early days of Native settlements to the gold-rush booms during the 1890-1900s. Alaska Natives relied on pack dogs to help carry fish and supplies during the seasons.

The great Iditarod sled dog race from Willow to Nome ended at 4:04 a.m. Tuesday morning with an upset when Dallas Seavey and his seven-dog team braved a harsh storm and beat four-time Iditarod champion Jeff King who led much of the prior day. Seavey made the journey with a time of eight days, 13 hours, 4 minutes and 19 seconds, shattering Kotzebue musher John Baker’s 2011 record for the fastest time to Nome by more than five hours. In the end, Seavey’s dogs had the stamina and speed needed to win.

Speed has not always been what dogs in the north have been noted for, however. In fact, Natives of Alaska, northern Canada, Greenland and Siberia used their dogs as winter draft animals for centuries. Russians arriving in western Alaska during the early 1800s found Alaska Natives using dogs to haul sleds loaded with fish, game, wood and other items.

The Natives ran ahead of the dogs as they guided them on the yearly trips between villages and fish and hunting camps. Russians improved the dog and sled system by adding handlebars to sleds and harnessing dog teams in single file or in pairs. They also trained the dogs to follow commands given by sled drivers and introduced the “lead dog.”

Russian exploration via dog teams was limited to Alaska’s coasts, as well as along some rivers, and followed existing Native trails between villages. Both Natives and Russians found frozen rivers also made useful winter trails.

Extensive use of dogs for long-distance transportation developed as gold discoveries were made in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Stampeders quickly learned that dog teams were worth their weight in gold. Thousands of dogs were imported from the Lower 48 to help prospectors and adventurers reach the gold fields.

By the turn of the century, dog teams were helping cheechakos blaze new trails to establish law and order, develop mail routes and transport gold-crazed prospectors to new strikes north and west of Prince William Sound.

From Valdez, a route was made to get to the Interior boomtown of Fairbanks. It became known as the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail.

From Seward, winter trails developed north and west. Then roughly blazed sled dog trails connected the communities of Sunrise, Hope and scattered trading posts at Resurrection Bay, Knik Arm and the Susitna River after Al King discovered gold on Resurrection Creek. Miners and merchants also combined to build a wagon road from Sunrise up Six-Mile Creek along the mining claims.

When winter came, some miners hooked up their dogs and pulled Yukon sleds loaded with needed supplies up the Kenai, Susitna, Knik or other rivers and made camp at promising locations. They then spent the winter thawing ground and digging gravel. At spring breakup, the prospectors sluiced the hoped-for gold from pay dirt. At season’s end they built rafts or poling boats and floated with their dogs back downstream to the trading posts or towns. This is the way the land was prospected.

The main trail from Seward to the various prospects in Southcentral Alaska traveled along the railroad right-of-way to Turnagain Arm, then along the north side of the Arm to Girdwood and over Crow Pass. It dropped into the Eagle River valley, to the Indian village of Eklutna and then around the upper end of Knik Arm to Knik.

By 1905, dog teams were carrying mail over 180 miles of trail between Seward and Susitna Station, a steamboat stop on the lower Susitna River that served as a supply point for dozens of mines in the foothills of the Alaska Range. The system of trails extended as goldfields were discovered to the north in the Talkeetna Mountains and the Yentna River drainage.

And when gold was discovered along the Innoko River around 1906-1907, another trail was forged by dogs that would become one of the most famous sled dog trails in history. Yes, dogs helped to blaze the famous Iditarod Trail from Seward to Nome between 1908-1910. Walter Goodwin of the Alaska Road Commission made the first official trip across the completed wilderness trail and arrived in Seward in February 1911. It took him several months to travel a route than now can be crossed in just over a week.

The post Sled dogs lead the way through Alaska’s history appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

March 3, 2014

First Anchorage Rendezvous brought loads of fur and fun

The blanket toss was a popular event at winter festivals in early Anchorage. It represents how Natives were tossed high in the air to see if seals were in the distance in remote Alaska.

The streets of Anchorage came alive this past week with the 42nd Iditarod Trail race festivities and the 79th Fur Rendezvous. The Fur Rondy is a 10-day celebration, which includes winter sports, cultural activities and lots of fur auctions that delight all ages.

Seventy-nine years ago a few fellows got together and decided it would be great to put together a winter tournament for all of Anchorage’s residents. Vern Johnson, Clyde Conover, Thomas Bevers and Dale Bowen wanted to organize several teams to compete in hockey and basketball.

With the city’s population less than 4,000 at the time, the idea took hold and turned into a carnival to show community support and celebrate the beginning of the end of winter. Revelers bought tickets for $2 apiece, which got them in to all of the activities around town.

And it didn’t take long for fur trading to become part of the winter festival, held at the end of February. The second-leading industry in the territory, a fur-trading venue provided trappers and buyers a golden opportunity to meet and ply their trade without using middlemen.

Organizers of the event came up trapping contests that included categories for the longest fox, the best fox and the finest ermine pelts.

In 1937, the carnival was dubbed the Fur Rendezvous festival, and in 1939, the first Fur Rendezvous pin was designed. Every year since, a different design has been selected and reproduced on pins, spoons, tie tacks and other collectables.

In just a few years, the idea for a competitive sporting event turned into a major revenue-maker and stress-reliever for Anchorage residents, as well as for those who traveled into town from other parts of the territory and “Outside.”

Bevers, a local businessman and Anchorage Fire Department chief, auctioned several lots of furs at the 1939 Fur Rendezvous. Josie Lester later recounted what she had witnessed at the fur auction.

“…Lot 87C: Eleven otter—$40—what? Eleven otter for $40? Maybe you didn’t understand me,” hollered Bevers. “You did? 40, 110, 125 … 174, 5, 182, 182 bid. Eleven otter for $182. Otter be worth more’n that! Going for $190. Once, twice, sold!

“I surely enjoyed seeing those fellows scrap among themselves for the furs. They meant business, too, and to watch them you’d think that they’d gladly cut each other’s throats if not restrained by the ethics of the game. I never have seen such a bunch of men get so deep down in a batch of notes as they did – hat and all….”

Lester observed that the reason for the Rendezvous may have been sports and furs, but most Anchorage residents turned out just to have a good time.

And that hasn’t changed in 79 years!

The post First Anchorage Rendezvous brought loads of fur and fun appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 24, 2014

Iditarod Trail Race Conceived 50 Years Ago

A dog team howls along the Iditarod Trail.

Alaska’s 2014 Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race unofficially begins on Saturday, March 1, with a ceremonial start in downtown Anchorage. And after weeks of worry that a lack of snow could jeopardize the famous race, about 70 mushers will take off from Willow and begin the dash to Nome in earnest on March 2.

The two legendary visionaries who conceived the 1,049-mile race to Nome hardly could have imagined the success and changes that would happen over the next 40-plus years of the “Last Great Race.”

It all started when a history buff living in Wasilla had an idea in 1964. Dorothy Page, secretary of the Aurora Dog Mushers Club, saw that snowmachines were fast taking the place of dog teams and mushing. She thought a sled dog race on the historic Iditarod Trail, which originally began in Seward during the gold rush days and stretched to Knik, then on to the gold camp of Iditarod and eventually to Nome, might revitalize a longtime Alaska tradition. But Page knew that she would have to find a musher to share her dream before it could become reality.

She endured comments such as “Are you crazy?” for two years, until she talked to Joe Reddington Sr. during a break at the Willow Winter Carnival sled dog races in 1966. Page explained her idea to the veteran musher, who had traveled over sections of the historic Iditarod Trail while homesteading near Flat Horn Lake.

His response, “I think that’s a great idea!” has been echoed by hundreds of mushers from all parts of Alaska, the Lower 48 and even foreign countries ever since.

Fifty-eight mushers signed up to compete for $25,000 in prize money for the 1967 inaugural race. Since only nine miles of the trail had been cleared, the race ran from Knik to Big Lake on Saturday, and from Big Lake to Knik on Sunday, for a total of 56 miles. Isaac Okleasik, an Eskimo from Teller on the Seward Peninsula north of Nome, won the “Iditarod Centennial Race.”

Due to a lack of snow in 1968, a lack of money in 1969 and a lack of interest from 1970-72, the race was put on hold. But the behind-the-scenes work continued as volunteers cleared the brush from both the Nome and Knik ends of the trail.

Finally, on March 3, 1973, amid the cheers of hundreds of well wishers, 34 mushers left Anchorage headed for Nome in pursuit of not only a dream, but also $50,000 in prize money pledged by Reddington Sr.

Dick Wilmarth, a hardworking gold miner from the Interior village of Red Devil, crossed the finish line first. It took him 20 days, 49 minutes and 41 seconds to travel the old winter trail that mushers hadn’t used for 45 years.

Forty years later, modern mushers have cut that time by more than half through new technology in sled design and the breeding of faster dogs. Last year’s champion, Mitch Seavey of Seward, crossed the finish line in Nome in 9 days, 7 hours, 39 minutes and 56 seconds.

Alternating every year between the southern route and the northern route, the current trails cross the Alaska Range, Kuskokwim Mountains, Nulato Hills and over 200 miles along the mighty Yukon River. Once the mushers take off from Knik, they leave civilization behind and only have small towns and villages such as Skwentna, Nikolai, Ophir and Unalakleet to break the monotony of traveling in bone-chilling cold until they reach the historic Gold Rush town of Nome, perched on the shores of the Bering Sea.

#AuntPhilsTrunk #AlaskaHistory

The post Iditarod Trail Race Conceived 50 Years Ago appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 15, 2014

Last surviving territorial governor dies at 94

Alaska Territorial Gov. Michael Anthony “Mike” Stepovich, center, holds a newspaper proclaiming Alaska’s admission to the Union as President Dwight D. Eisenhower, left, and then-U.S. Rep. Gerald Ford look on in 1958

The curtain closed on a chapter in Alaska history last week. Michael Anthony Stepovich, known as “Mike,” died on Friday – Valentine’s Day – at the age of 94. He was the last surviving territorial governor of Alaska.

Born at St. Joseph Hospital in Fairbanks on March 12, 1919, Stepovich was the son of a gold miner from Montenego who had come north like other gold rush stampeders, And although he grew up in Oregon, Stepovich came back to Alaska and made a name for himself in the territory.

After he earned a law degree at Notre Dame, and served with the U.S. Navy during World War II, he returned to Alaska and set up a law office in Fairbanks. As politics heated with statehood talk following the war, he tossed his hat in the ring for the Alaska Territorial Legislature.

He ran as a Republican and won a house seat in 1950. Then in 1952, he was elected to the territorial senate.

Five years later, Stepovich made history when U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him to the office of territorial governor – he became the youngest, 38, and the first Alaska-born governor of the Great Land.

Stepovich was a staunch supporter of statehood for Alaska and worked tirelessly toward that end. He traveled constantly across the country lobbying for Alaska’s admission to the union. He appeared on “Tonight with Jack Paar,” the TV show “What’s My Line,” and was featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1958 standing in front of a totem pole.

The young governor met often with Eisenhower, who was not keen on the idea of Alaska becoming a state. But Stepovich, along with other political leaders in the territory, eventually changed the president’s mind about the issue.

There probably was no one happier than Stepovich when the U.S. Congress finally voted to allow Alaska to become a state on June 30, 1958. But since the territory still had to elect a U.S. congressman, two senators and a governor, Alaska’s official entry to the union was on Jan. 3, 1959.

After three unsuccessful political campaigns – one for the U.S. Senate and two for governor of Alaska, Stepovich returned to his law practice and eventually retired to Oregon in 1978. His wife, Matilda, died at 81 in 2003. He is survived by his 13 children.

The post Last surviving territorial governor dies at 94 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 10, 2014

Love and Marriage – Gold Rush Style

When ministers were in short supply along the trails to the golden riches of the Klondike, love-crazed couples might just gather some friends, exchange their vows and then declare themselves married.

As Cupid flits about flinging arrows into unsuspecting lovers this week, I thought it would be fun to take a look back in Alaska’s history and see what love-struck couples did when their stars crossed and they wanted to marry.

Well, it turns out that miners during the Klondike Gold Rush sometimes had to improvise when it came to matters of the heart. With no judges or preachers in the camps, they had to think up unique ways to perform nuptials. And so it was for two lovers on the Koyukuk trail.

Aggie Dalton and Frank McGillis wanted to marry, and in lieu of an official marriage contract, they created a substitute document – along with one “French Joe.” An account of the ceremony, which took place at a night camp with a group of stampeders en route to a Koyukuk River gold camp, was reported in the society columns of the Yukon Press on March 17, 1899:

Unique contract of marriage

“On the evening of November 10, 1898, a romantic union took place between Frank McGillis and Aggie Dalton, near the mouth of Dall River. Splicing was done by ‘French Joe’ (J. Durrant), and the form of the contract was as follows:

“Ten miles from the Yukon on the banks of this lake,

For a partner to Koyukuk, McGillis I take;

We have no preacher, and we have no ring,

It makes no difference, it’s all the same thing.”

– Aggie Dalton

“I swear by my gee-pole, under this tree,

A devoted husband to Aggie I always will be;

I’ll love and protect her, this maiden so frail,

From those sourdough bums, on the Koyukuk trail.”

– Frank McGillis

“For two dollars apiece, in cheechaco money,

I unite this couple in matrimony;

He be a rancher, she be a teacher,

I do the job up, just as well as a preacher.”

– French Joe

Happy Valentines Day to all my Alaska history fans!

This story appears in Aunt Phil’s Trunk, Volume Two.

The post Love and Marriage – Gold Rush Style appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

February 4, 2014

‘The Cheechakos’ – Alaska’s first homegrown movie

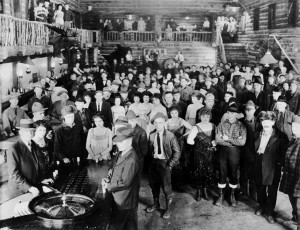

Many Anchorage residents enjoyed a bit of celebrity as they portrayed dancehall enthusiasts in Austin E. “Cap” Lathrop’s production of “The Cheechacos” in 1923.

Movies about Alaska, mostly based on books by Jack London and Rex Beach, thrilled audiences during the early 1900s. But all motion pictures were filmed outside of Alaska. So when a group of Oregon promoters planning a travelogue and feature film about the territory toured Alaska’s towns in 1922, several Anchorage residents decided to go into the filmmaking business themselves.

They formed the Alaska Motion Picture Corp. and elected Austin E. “Cap” Lathrop, who owned theaters in Anchorage, Fairbanks, Seward, Valdez and Cordova, as president. The businessmen raised $75,000 to produce a 12-reel picture, which included a three-reel travelogue followed by a nine-reel drama.

The group built a 7,000-square-foot studio in downtown Anchorage with an eye to becoming the “Hollywood of the North.” About 1,000 Anchorage residents hosted a “free dance and jollification at the moviedome,” to welcome the cast of actors recruited from Oregon, New York and Hollywood when they arrived in 1923.

Shortly thereafter, the cast and production crew traveled by train to McKinley National Park to film winter scenes with dog teams to show the drama of the gold-rush days. They also traveled to Girdwood, where they recreated the days of 1898 when miners climbed the Chilkoot Trail.

The Anchorage Daily Times reported on the production of the silent film in its April 4, 1923, edition:

“The struggles of former years will once again be fought by real veterans of the early days, many of them still retaining and wearing the identical garments and packs, such as jackets, parkas, fur hats and pack boards used by their owners during the stampede days over the great Chilkoot Pass. Tandem dog teams will once again hit the trail with the Yukon sled in prominence. The vast illumination will portray sled loads of supplies of flour, bacon, salt, beans, sugar, coffee, tobacco and other bare necessities used by the prospectors.”

The script of the only movie made by the Alaska Motion Picture Corp. tells the story of two good-hearted gold prospectors who take in a young girl who was left motherless after a ship explosion. When the sourdoughs strike it rich, the younger miner falls in love with the girl. Through tough experiences, they all learn that disreputable gamblers can be as dangerous as the frozen north.

When released in New York in 1924, Variety dismissed the plot as “hokey,” and expressed doubt that a film with such an unpronounceable title could succeed. Indeed, The Cheechakos failed in the Lower 48 and dropped from movie history.

Although Lathrop and his group had hoped to make more movies in their Anchorage studio, they soon modified it into an exhibition center for the Western Alaska Fair during the 1924 Labor Day weekend. It later served as the Anchorage community center for years.

This story was included in Volume Two of the Aunt Phil’s Trunk Alaska history series.

The post ‘The Cheechakos’ – Alaska’s first homegrown movie appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

January 27, 2014

Wacky weather warms Alaska winter

A glacier-sized avalanche at Snow Slide Gulch in Keystone Canyon has blocked the Richardson Highway and cut off the town of Valdez from road access

The wacky weather across the Continental United States this winter is really crazy. While those who live in the Midwest and East Coast dig out from the 2014 Snowcropolis, Alaskans are seeing one of the warmest January’s on record.

And as the thermometer hovers in the mid-40s across much of the state, the melting snow is causing havoc to many residents. My son-in-law said his sump pump started up as the water from the melting snow is now seeping into his crawl space in Anchorage. And a friend from Fairbanks just told me that school was cancelled because the standing water on the icy streets is causing hazardous driving conditions to the community that normally sees below-zero temps during the winter months.

But this unusually warm January has really brought headaches to the folks who live in the little coastal community of Valdez, located about 300 miles south of Anchorage.

Two massive avalanches, which have left debris about 100 feet deep on the Richardson Highway, have blocked the only road into Valdez and left about 4,000 people isolated.

The first avalanches hit on Friday. Townspeople said the snow slides sounded like jet airplanes coming in. More massive slides occurred late Saturday afternoon. The Alaska Department of Transportation has closed the road from mileposts 12 to 64.

“These are some of the largest avalanches they’ve ever seen come down on Thompson Pass,” a DOT spokesman said in an Anchorage Daily News interview.

Residents of Valdez are fearful of major flooding, too, as the avalanche on Saturday has blocked the Lowe River in Keystone Canyon and a large amount of water is backing up behind it.

Crews, who have been dropping aerial explosives on chutes in an attempt to avert more snow slides, also are facing record rainfall for this time of year. Up to three inches fell on Friday, a record for that day in January.

Authorities report that the road may be closed for a week or more, but the airport remains open and food is being barged in on ships. Ferry runs also are being increased between Whittier (about 60 miles south of Anchorage) and Valdez.

One can only wonder if this wacky weather is going to become our new winter normal or if it is just a flash in the pan that will fade with our memories and become another anecdote in Alaska’s history.

The post Wacky weather warms Alaska winter appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

January 21, 2014

One gold-rusher prospects the prospectors in Nome!

After steaming into waters near Nome, prospectors then jumped into small boats and headed to the beaches to find their fortunes.

Fired with the romance of the undertaking and inspired by exciting rumors, thousands thronged to Nome’s beaches in 1900 after gold nuggets were found in the sand. Lured by the siren’s cry of “gold,” prospectors who’d not had luck elsewhere in Alaska came in the hopes that Nome’s sand would become their pay dirt.

But several adventurers, like A.F. Raynor, swarmed to the Seward Peninsula to mine the gold-mad prospectors.

Raynor, a port steward for the Blue Star Navigation Co., was working in St. Michael when he heard the news of Nome’s riches. He immediately resigned his post and joined the stampede. His goal: to make “easy money” off the miners by feeding their stomachs.

Along with a stock of groceries, the gold-rusher purchased a large range and an assortment of crockery that had never been claimed for a hotel up the Yukon River. Raynor also bought a 30-by-40-foot tent.

He piled his provisions onto the schooner Hera and sailed to Nome, where he was put ashore in between heavy surfs. Once he’d hauled his outfit to safety, he found the only lumber dealer and picked up enough wood, at $1 per board, to build a lunch counter and a few crude stools.

The tent city housed about 2,500 people, and every steamer arrival boosted Nome’s population more. Raynor quickly set up his cook tent opposite “Tex” Rickard’s saloon and gambling house, which was the largest in the camp.

He kept his menu simple, offering dishes like beans for $1 a plate; ham and eggs for $2.50; evaporated potatoes for 50 cents an order; and black coffee for 25 cents a cup. When a man with a cow walked into Raynor’s café two weeks after it opened, Raynor ordered a gallon of milk to be delivered daily for $1 a quart. He then slapped up signs announcing “Fresh Milk.”

But after the first order was delivered, he learned that the man had contracted to deliver 50 gallons of “fresh” milk a day to others in the community from this one remarkable cow. Raynor quickly tasted the gallon that he’d just purchased and cancelled his contract. He told the “dairyman” he could make a better batch by mixing a can of evaporated milk with water.

A few days later, the man offered Raynor the beast, because he couldn’t get feed for it. Raynor bought the cow, skinned and dressed, but soon learned that its steaks were too tough to eat.

“I will always believe that the cow never met her death at the hand of a butcher, but just laid down and died from malnutrition,” he said later. “Such a scrawny array of bones as I had to work with I never saw before and never expect to see again.”

Raynor put the carcass through a meat grinder and still made a tidy profit on hamburgers and stew!

The post One gold-rusher prospects the prospectors in Nome! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.