Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 12

January 15, 2014

The Voice of the Yukon

Robert Service, who left Dawson when he was 36, wrote hundreds of poems during his lifetime. He died at 84.

Robert Service would have been the first to call what he wrote verse – and he advised young men to “write verse, not poetry – the public wants verse.”

Although this Englishman of Scottish ancestry spent most of his life in the New World in Canada, Alaskans adopted the poet of the Yukon, too. For surely no one before or since has better interpreted the vastness, power, beauty and cruelty of the North.

After landing in Skagway in the early 1900s, he boarded a White Pass and Yukon Railroad coach. As it inched up over the narrow gauge tracks by precipitous cliffs, he could see where so many gold seekers had fallen to their deaths. When he arrived in Whitehorse it was 40 below, and he found the town teeming with Klondikers on their way to and from the mines, loaded with gold dust and yarns.

The sensitive young man found it a thrilling environment and began to write rhymes describing the North Country. Most of them ended up condemned to the bottom of a drawer. But some people thought his rhymes had merit.

Service later told how “Dangerous Dan McGrew” began: “Stoller White, editor of the Whitehorse Star, first suggested my writing an original poem to recite (at a church gathering). I decided to give it a try and went for a long walk to think it over. As I returned from my walk, I had nothing doped out. It was a Saturday night, and from the various bars I heard sounds of revelry. The line popped into my mind, ‘A bunch of the boys were whooping it up,’ and it stuck there. Good enough for a start….”

The rest of the stanzas came so easily he was amazed. It was as if someone was whispering in his ear. Before he crawled into bed at 5 a.m., his ballad was in the bag. However, he decided against using it for the initial purpose – the cuss words, he thought, made it impossible to recite at a church concert.

“The Cremation of Sam McGee,” “The Call of the Wild,” “The Spell of the Yukon” and many other ballads followed within short order. And although we know Service was never in the Klondike, his poems seem strangely authentic and true to the country.

Will Rogers’ tribute back in the 1930s explains the popularity of Robert Service. Rogers said Service served the common man “literary steak, well seasoned with plenty of calories and tasty trimmings.”

Service died in September 1958.

The post The Voice of the Yukon appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

January 6, 2014

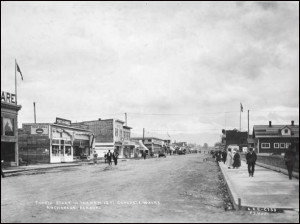

First Anchorage mayor faced weighty issues

During the summer of 1917, 18 blocks of 12-foot concrete sidewalks and two blocks of 6-foot sidewalks were constructed in downtown Anchorage. The townsite at that time had more than 1,349 buildings, five churches, electric lights and telephones.

With all the recent talk about the nation’s leading lawmakers, and politics in general, I started thinking about the early movers and shakers in Alaska history. They had huge problems to deal with, too.

For instance, Anchorage’s first mayor, elected on Nov. 29, 1920, bore the responsibility of governing a railroad town after five years of Alaska Engineering Commission management ended.

When Judge Leopold David became Anchorage’s mayor, he helped the new city council develop ordinances to provide law and order. The laws included establishing a 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. curfew for youth under 16, setting a speed limit of 8 mph in town and outlawing spitting in public places.

Judge David, an immigrant from Germany, came to Alaska in 1904 with the U.S. Army and served as a pharmacist’s assistant in the Hospital Corp. at Fort Egbert. After his discharge a year later, the 24-year-old settled in Seward, married Anna Karasek and managed the Seward Drug Co. Like many pharmacists of the time, his basic medical knowledge earned him the title “Dr. David” among the townspeople.

Ever public service minded, he served as the U.S. Marshal at Susitna Station in 1909 and also as a U.S. Commissioner at Knik when he moved there in 1910. It’s believed he studied law while living in Knik and served as ex-officio probate judge.

David continued his role as Commissioner and District Recorder after he arrived at Ship Creek in 1915 and affixed his signature to almost every land transaction in the new community.

Documents for land use for Anchorage’s 1915 townsite stated the property was not to be “used for the purpose of manufacturing, selling or otherwise disposing of intoxicating liquors, or for gambling, prostitution or any unlawful purpose.” However, those vices flourished.

Thirty or 40 women “entertained” construction workers in tents and shacks southeast of town, but they were forbidden to mingle on the main street with the townspeople.

The mayor and Anchorage City Council tried to curtail gambling by adopting a “curtain ordinance,” which required an unobstructed view from the street into “pool halls, cigar stores, soft-drink emporiums, and other businesses of a similar character.”

The problem of alcohol and bootlegging proved more difficult to address. Although prohibition had been adopted in 1918, David found it virtually impossible to keep alcohol from flowing in the frontier town.

After two terms as mayor, David, who’d passed the Bar of the state of Washington, turned his attention to his law practice with L.V. Ray. But at 43, heart disease took his life. He died on Nov. 22, 1924.

The city’s first mayor was buried in the Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery, where his headstone erroneously identified him as “Physician and Surgeon” rather than “Attorney at Law.”

Many stories about early Anchorage fill the pages of Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume Three.

The post First Anchorage mayor faced weighty issues appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 30, 2013

Happy Russian Orthodox Christmas!

A group of people hold a Russian Christmas star on a beach in Unalaska in the early 1900s.

Many Alaska Native families will celebrate the Russian Orthodox Christmas this next week, beginning on January 7.

This observation of Christ’s birth began after Christmas celebrations were banned following the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Russian families turned decorating trees and giving presents into New Year’s traditions.

Alaska’s First People have a long history with the Russian Orthodox Church, as Native cultures were heavily influenced following the arrival of Russian fur traders in 1741. And although Russia sold Alaska to America in 1867, the Russian Orthodox Church continues to be a vital part of Native culture in many Alaska communities.

The common symbols of the Russian Orthodox Christmas are a decorated fir tree, baby Jesus and a star – like the one held by this group near Unalaska in the early 1900s. The celebration lasts for a week and includes church services, fireworks and special foods.

Part of the tradition involves “starring,” also called slaviq, in which a brightly decorated star is carried from house to house and carolers sing a song outside until the family invites them in.

The singers face the folks inside the home and twirl the star as they sing carols, sometimes in English, Russian, Slavonic, Yup’ik, Alutiiq, Dena’ina and other Alaska Native languages. After the carolers eat food the family has prepared, they move on to other houses where the ritual is repeated until late into the night. Sometimes presents are given, as well.

Some of my Native friends tell me that they travel from village to village with their stars and caroling. A bonfire on the last day signals the end of the festivities until the next year.

Happy Russian Orthodox Christmas to all!

The post Happy Russian Orthodox Christmas! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 24, 2013

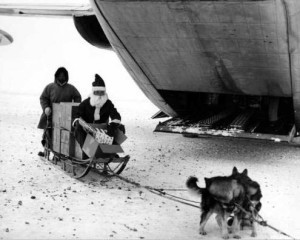

Santa visits rural Alaska villages

A team of huskies pulled Santa and a sled full of toys away from a C-123 plane at Savoonga, on St. Lawrence Island, in 1963. Frost built up on the driver’s parka on that minus 20-degree temperature day.

Ho! Ho! Ho! Merry Christmas! I hope you all had a marvelous Christmas with family and friends. Thought you might enjoy this short note about Operation Santa Claus, which began in 1956.

Alaska’s Air National Guard received a request from St. Mary’s Mission for toys for its children that year. Spring floods meant a dismal fishing season, then a drought pretty much eliminated any successful hunt for game. The villagers had to spend their money to ship food into the village, so they had no money to buy gifts for the children.

The Guardsmen decided to help bring joy to the little ones. They collected new and used toys from folks in Anchorage to take to the little village, located 450 air miles west-northwest of Anchorage.

St. Mary’s, which began as a supply depot and winter headquarters for the Northern Commercial Company in 1899, was named after the Andrea family settled on the Yukon River and built a Russian Orthodox Church there. A mission school soon followed. Villagers moved their settlement to higher ground in 1948. They used lumber and other materials from an abandoned gold rush hotel to build a new mission and several homes.

Loaded with gifts for the children, the first Operation Santa Claus took off from Anchorage in a C-123J Provider aircraft. The Yup’ik people of St. Mary’s warmly greeted Old Saint Nick and the airmen who accompanied him.

Operation Santa Claus turned into a joint venture between the U.S. Air and Army National Guard. Santa, who now flies in a C-130 Hercules, brings toys, clothing, books, school supplies, fresh fruit and sundaes to youngsters and elders in communities across the state.

The post Santa visits rural Alaska villages appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 19, 2013

Aunt Phil’s Trunk Goes Digital!

It’s happened! All four books in the Aunt Phil’s Trunk Alaska history series now are available as e-pubs. It took a lot of research, determination and help from e-book experts, but the series launched as e-books last week.

Anyone interested in the getting the series in e-book formats – including for Nook, Kindle, iPhone and most other platforms – can come to my Website www.AuntPhilsTrunk.com and order them for only $14.95 each!

Merry Christmas to each and every one of my incredibly awesome Alaska history folks. You are why this series has become so popular and why they now are available as e-books. Aunt Phil has the best fans in the world!

The post Aunt Phil’s Trunk Goes Digital! appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 11, 2013

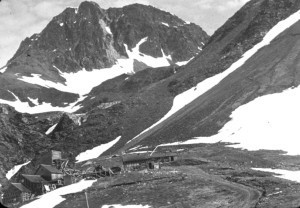

Girdwood settles on Crow Creek

Glacier City, later renamed Girdwood, was a small distribution settlement on a trading and transportation route over the Chugach Range in 1906.

Kudos to Girdwood! The rustic little ski town near Crow Creek south of Anchorage was named in the top 25 of the World’s Best Ski Towns by National Geographic! Like many of Alaska’s towns, Girdwood can trace its roots to the gold rush era more than 100 years ago.

As news of Alaska gold spread through America in the mid-1890s, hundreds of people flooded Seattle docks seeking transportation northward. Among the 100 passengers who packed onto the Cook Inlet-bound steamship Utopia was a man whose name would become synonymous with an Alaska ski resort.

James E. Girdwood traveled to Kachemak Bay in early May 1896, where he hopped aboard the small steamer L.J. Perry, run by “Cap” Austin E. Lathrop. Girdwood made his way through the ice-filled Cook Inlet to settle for a short time around Sunrise City and Hope.

Girdwood, the son of a Dublin linen merchant, studied the region and eventually staked placer ground on Crow Creek, across Turnagain Arm from Sunrise. He built his cabin at Glacier City, a small distribution settlement on a trading and transportation route over the Chugach Range. He then rolled up his sleeves and dove into prospecting for gold.

The linen salesman was used to hard work. After arriving in New York City in 1882 with only $400 in his pocket, the then 20-year-old managed to control more than half of the Irish linen market in the United States within 14 years. Girdwood came north with the money from the sale of his business and put it into his mining venture on Crow Creek.

By 1900, Girdwood had staked four claims called the Annex, Omega, Alpha and Little Gussie. His Crow Creek Alaska Hydraulic Gold Mining Co. was operating some of the largest hydraulic plants in the Turnagain Arm region by June 1904.

The mining claims paid off in subsequent years, yielding bullion income exceeding $106,000 a year. And Girdwood proved so popular with his fellow miners that they gave him the honorary title of “colonel” and renamed Glacier City after him.

With his gold-mining operation doing well, he shifted his attention to another metallic element found in abundance in Alaska.

Girdwood staked copper claims on Latouche Island. On Jan. 4, 1907, he formed the Latouche Copper Mining Co. in New York and became a close friend of Daniel and Isaac Guggenheim. He sold his copper claims to the Ladysmith Corp. in 1921, which later sold them to Kennecott Copper Co.

Girdwood’s gold mining company operated high in the Crow Creek Valley for many years. It built several cabins, had a five-ton derrick and brought in a large giant to undertake the mammoth task of removing boulders from the streambeds. About 50,000 yards of gravel were removed in 1905 in order to get those flakes and nuggets known as placer gold.

Eventually the operation became too demanding, and the practice of dumping tailings into the creek started raising legal problems. A court injunction finally closed the operation.

A short-lived effort to raise money to revive the mine in the mid-1920s failed, and Girdwood returned to the East Coast. He died in 1928 at his home in New Jersey.

The post Girdwood settles on Crow Creek appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

December 5, 2013

Trappers help economy throughout Alaska History

A trapper scrapes a fresh skin, as a beaver hide stretches on a frame nearby.

Trappers helped to build the economy throughout Alaska history. These adventurous souls didn’t search the creek beds and mountains for golden riches. Instead they chose to make their fortunes through trapping furs. From early in the fall to the close of trapping season in April, many trappers traveled miles and miles of trap lines with no company but that of their dogs. It was no job for a “cheechako.”

Trappers like Ed Ueeck covered around 80 miles a week, checking to see if any animals had been caught in hidden traps.

“About 14 miles a day is my average travel on the circle, although I cover considerably more than that, of course, on the side trails,” Ueeck told Tom Jackson in an article for the October 1939 issue of The Alaska Sportsman. “During the trapping season there are only six hours of daylight at the most, and it is long after dark before I reach the trail cabin at the end of a day’s hike complete.”

Once trappers fixed something to eat and fed their dogs, they then had to skin and care for the furs they’d picked up along the line and get ready for the next day.

“Blinding storms are sometimes encountered far out on the trail between shelter cabins, and a biting wind with the thermometer at 40 below zero makes it seem twice that cold,” Ueeck said. “When a trap has been sprung, it has to be reset with bare hands, and it must be done quickly and carefully … frozen hands can easily spell disaster to a trapper who is a hundred miles from civilization.”

Ueeck started out in the Matanuska Valley helping colonists harvest their crops. But when he saw the prices paid for furs, he switched professions and headed into the wilderness. He chose a spot near Lake Leila, on the divide between the Nelchina and Matanuska rivers.

After unloading six months of supplies from a pontoon aircraft, he picked up an ax and began swamping a trail through a heavy growth of willows to build his headquarters cabin on higher ground.

Once that cabin was finished, he spent a few years building another six cabins on the circumference of a circle, whose center was the main cabin. He stored his winter supplies in a cache, about 18 feet above ground, to prevent wild critters from helping themselves to his grub.

Ueeck’s story is similar to hundreds of early trappers who turned to the Last Frontier to eek out livings in the wilderness. Most didn’t talk much about the money they made, nor the hardships they endured climbing creeks and mountain ridges as they routed out any unlucky fur bearers that happened to cross their paths. But they knew that any man who could make a living from trapping in Alaska could make a success of anything.

Excerpted from Aunt Phil’s Trunk Volume 2

The post Trappers help economy throughout Alaska History appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 26, 2013

Miners’ Code ruled the Last Frontier

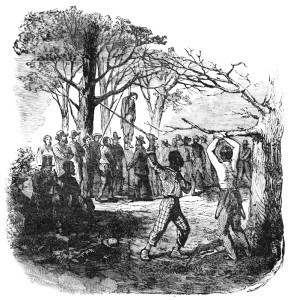

Far from the long arm of the law, prospectors during Alaska’s gold rush days relied on the miners’ code to mete out justice in the Last Frontier.

Prior to the arrival of sheriffs and judges to the Far North, a practical application of frontier democracy called the Miners’ Code ruled the Last Frontier. Each camp decided matters of common concern by majority vote and meted out justice to fit the crime.

When a situation came along that necessitated a meeting, the miners came together and elected a judge and a sheriff. Defendants and plaintiffs then gave their sides of the story, and after all the evidence was weighed, the miners would render a verdict.

Murder was punished by hanging; stealing meant a sound whipping or banishment. The guilty had no notice of appeal, no bill of exceptions and no stay of execution.

Miners sometimes took justice into their own hands when it came to matters of the heart, too. With no judges or preachers in the camps, they had to think up unique ways to perform nuptials, as was the case of some lovers on the Koyukuk trail.

Aggie Dalton and Frank McGillis wanted to marry, and in lieu of an official marriage contract, they created a substitute document along with one “French Joe.” An account of the ceremony, which took place at a night camp with a group of stampeders en route to a Koyukuk River gold camp, was reported in the society columns of the Yukon Press on March 17, 1899.

“On the evening of Nov. 10, 1898, a romantic union took place between Frank McGillis and Aggie Dalton, near the mouth of Dall River. Splicing was done by ‘French Joe’ (J. Durrant), and the form of the contract was as follows:

Ten miles from the Yukon on the banks of this lake,

For a partner to Koyukuk, McGillis I take;

We have no preacher, and we have no ring,

It makes no difference, it’s all the same thing.

Aggie Dalton.

I swear by my gee-pole, under this tree,

A devoted husband to Aggie I always will be;

I’ll love and protect her, this maiden so frail,

From those sourdough bums, on the Koyukuk trail.

Frank McGillis.

For two dollars apiece, in Chechaco money,

I unite this couple in matrimony;

He be a rancher, she be a teacher,

I do the job up, just as well as a preacher.

French Joe.”

(Volume 2, Aunt Phil’s Trunk)

By Laurel Bill

AuntPhilsTrunk@gmail.com

Alaska history

The post Miners’ Code ruled the Last Frontier appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 18, 2013

Petroglyphs found in Alaska history

Mouths of salmon streams in Southeast Alaska are filled with inscriptions pecked into hard rock like this one found near Hoonah.

Not only is Alaska history steeped in fur trading, whale harvesting and gold mining. It also has drawings on rocks that are usually associated with primitive people in exotic far-away lands.

Greek for rock carving, petroglyphs are among many enigmas of science. Because their true meanings are elusive, they remain a mysterious link to a people who inhabited the world a long time ago.

The petroglyphs, which are in abundance in Southeastern Alaska, are unique because they are associated with salmon streams, rather than primitive village sites, and they always face the sea. Mouths of salmon streams are filled with inscriptions pecked into hard rock-like sandstone, slate and granite, while good rocks for carving remain bare in villages near those streams.

To those familiar with the ancient beliefs and oral traditions of the Tlingit and Haida Indians, the petroglyphs show that salmon is life. These Native Alaskans, whose diet was primarily fish, were not hunters and had no agriculture. If the salmon failed to return, it could mean starvation for the clans.

It made sense, therefore, for them to try to avoid small runs and to do everything possible to try and increase the runs. They may have carved images of intermediaries, including deities, “Raven” and others in special favor with the Salmon People, on the rocks in an effort to bring salmon back to their communities.

Legend has it that a Tlingit boy named Shin-quo-klah, or “Mouldy End,” was punished by the Salmon People for wasting dried salmon. They took him under the sea, but later returned him to his people.

He became a great shaman. It’s said that his image is etched on a rock at Karta Bay, placed near where he died after he accidentally killed his own soul that was inhabited by a supernatural salmon at the time. Copies of the etching were all around the beaches of Hydaburg and Wrangell, where it’s believed his influence was being used with the Salmon People to insure adequate runs of salmon.

Petroglyphs also appear in the Kodiak Archipelago, where at least seven sites have carvings that depict human figures, animal forms and geometric designs. There are four large clusters of petroglyphs at Cape Alitak, at the entrance to Alitak Bay. Some Alaskans think that the designs were made to mark territory, to act as permanent signs that linked families with particular subsistence harvesting areas.

The oldest rock drawings appear to have been carved as early as 10,000 years ago, and archaeologists have found similar abstract symbols along the coast of Siberia. There is no way to discern the true intent or motivation of the artists, but the drawings are one of the few sources of ancient art that tie Alaska Natives to their heritage.

Petroglyphs and associated sites are under the protection of federal laws and state of Alaska antiquities laws.

The post Petroglyphs found in Alaska history appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

November 11, 2013

Alaska military history spurred by WW II

Soldiers who arrived in Anchorage in 1940 had to chop trees and make a space in the wilderness on which to build Fort Richardson. Soldiers can be seen here exercising in front of their tents.

Soldiers who arrived in Anchorage in 1940 had to chop trees and make a space in the wilderness on which to build Fort Richardson. Soldiers can be seen here exercising in front of their tents.

This week we give thanks to all the U.S. military folks who served, are serving and will serve in the future. And Alaskans give our gratitude to the brave soldiers who came north in 1943 and forced the Japanese to leave the Aleutian Islands. Some people don’t know this, but the enemy landed on Alaska’s shores in June 1942 and occupied two of our islands, Attu and Kiska, for 11 months. That was the first time since the War of 1812 that foreign enemies were on American soil.

Alaska military history dates back to the purchase of of Alaska from Russia in 1867. The Department of War was put in charge of American’s new possession. But by the beginning of World War II there were only about 100 GIs in Alaska – all in the Southeast region. However, six years before the war broke out, Anthony J. Dimond, Alaska’s delegate to Congress, started asking for military planes, airfields, army garrisons and a highway to link Alaska to the Lower 48.

When the war actually began in September 1939, rumors ran rampant around Anchorage that his pleas had been heard and military bases soon would be built to protect the northern front.

Congress finally appropriated funds for Alaska in 1940, and the military started making plans for the construction of U.S. Navy and Army bases, ranging from Anchorage to Sitka and Kodiak to Unalaska. On June 27, Anchorage’s 4,000 residents greeted the first troops.

Under the command of Maj. B.B. Talley, engineers started construction of Fort Richardson, in honor of Brig. Gen. Wilds P. Richardson, who’d served as the first president of the Alaska Board of Road Commissioners from 1905 to 1917. The engineers also worked on an airfield, named to honor Capt. Hugh M. Elmendorf who’d died in an aircraft accident at Wright Field in Ohio in 1933.

Fort Richardson later became a U.S. Air Force base and took the name Elmendorf. The U.S. Army built a new Fort Richardson seven miles away, near the foothills of the Chugach Mountains.

Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner arrived in Anchorage in July 1940 and took charge of all military operations in the territory.

With the building of the military facilities stretching out over several years, serious housing shortages developed as the city’s population swelled to about 9,000 by mid-summer 1941.

However, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the population dropped as the government evacuated Army families. By April 1942, Anchorage had an estimated 3,200 men, 1,500 women and 1,300 children under the age of 18. Only about 75 of the 6,000 who remained in the city were Alaska Native.

The U.S. military increased its presence in Alaska, however, from 1942 until the end of the war in 1945. Then the numbers dwindled from 152,000 members to 19,000 by 1946.

Thank you again to all the veterans who fought, and still are fighting, to keep America free (more than 77,000 veterans live in Alaska)!

The post Alaska military history spurred by WW II appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.