Laurel Downing Bill's Blog, page 10

June 16, 2014

Japanese invade Aleutian Islands 72 years ago

Japanese troops settle in to defend the Aleutian Island of Kiska during 1942.

The remote islands of the Aleutian Chain, home to the Unangan people for more than 8,000 years, endured the first invasion on American soil since the War of 1812.

On June 6, 1942, at around 10:30 p.m., 500 Japanese troops came ashore at Kiska. They captured a small American naval weather detachment of 10 men, along with a dog. One member of the detachment escaped, but surrendered after 50 days – thin, starving and cold.

The enemy then invaded Attu at 3 a.m. on June 7.

Villagers, who’d been expecting American evacuation ships, instead found themselves running from bullets that Sunday morning. Thousands of Japanese troops poured over the hills surrounding the village of Chichagof – shooting as they came and wounding several villagers.

“The Japs are here,” screamed an Aleut woman amid a hail of bullets as she rushed into the cabin of Bureau of Indian Affairs teacher Etta Jones.

Jones’ husband, a 60-year-old radio technician who operated a government radio and weather-reporting station, began transmitting messages of the attack to Dutch Harbor.

Soon the Japanese were on the couple’s doorstep, and the Jones’ surrendered. Most sources agree that Charles Foster Jones was taken by the enemy and never seen again. Some say he committed suicide. Other sources say he was executed.

The villagers were all rounded up and herded to the schoolhouse. Once they all were accounted for, the Japanese allowed them to return to their homes, said Olean Prokopeuff (Golodoff) in a story that appeared in an Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association Inc. article for Aang Angagin. Prokopeuff, who lived through the event, said bayonet-carrying enemy soldiers guarded them.

The Japanese kept the Aleut fishermen busy for three days supplying the troops with food. Then the villagers were told to grab some food and personal items for themselves, because they were leaving the island. Prokopeuff said she then watched as Japanese soldiers burned her home.

Etta Jones, 62, and the village’s 40-plus Aleuts were transported in the hold of a freighter to Hokkaido, Japan, for internment. Prokopeuff said they were kept in the unpleasant-smelling hold for the entire trip, never seeing daylight until they reached Japan.

Etta Jones was separated from the Natives and interred at Yokohama, along with U.S. Navy personnel captured on Kiska, while the Aleuts were interred at Otaru, Hokkaido. Only 20 Natives survived the ordeal and returned to Alaska after the war ended.

After the Aleuts departed, the Japanese garrisons, which now numbered more than 11,000 troops, set up defensive positions on Kiska and Attu and began watching for attacks from the Americans.

The U.S. military finally ousted the enemy from Attu in fierce fighting during May 1943. Before the battle was over, there would be 549 American and 2,351 Japanese dead.

The Allied invasion of Kiska that followed found no opposition to the 32,000 U.S. and Canadian forces because no Japanese troops were left on the island.

Under cover of fog, the Japanese fleet had secretly removed its 5,000 soldiers from Kiska by I-class submarines and surface vessels prior to the Allied attack. Allied casualties during the invasion still numbered close to 200, however, as the enemy had set booby traps prior to leaving the island.

A mine in the harbor sunk a destroyer, killing 72 men. Another 17 Americans and four Canadians were killed from either booby traps or friendly fire, and 50 others wounded. Trench foot infected about 130 men.

Following the battles for Attu and Kiska, hundreds of American servicemen would have their feet amputated as a result of frostbite and trench foot, an infection of the feet caused by cold, wet and insanitary conditions.

The post Japanese invade Aleutian Islands 72 years ago appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

May 28, 2014

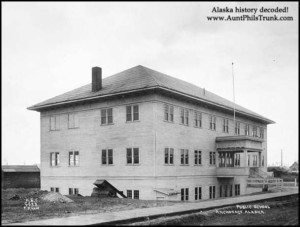

School Days Delayed in Early Anchorage

This school building, constructed by the U.S. government, was paid for by using 50 percent of the funds raised by selling lots in Anchorage during 1915. Congress authorized its construction on April 17, 1917.

When Land Office chief Andrew Christensen opened the auction for the townsite above Ship Creek on July 10, 1915, bidding became so brisk that prospective lot owners couldn’t hold down prices. After sales closed a week later, 655 lots had sold for almost $150,000 (more than $3.5 million in today’s dollars). Christensen claimed the sale had “injected confidence in the people of the town.”

But that confidence may have been tempered somewhat when the residents realized the Alaska Engineering Commission had overlooked a vital component in the new town. The Commission had sold the parcels of land with the understanding that the lots could be assessed to finance such public services as water and sewer utilities, fire protection and garbage pickup, but it had neglected to provide for financing a school.

It took months to solve the dilemma. In summer 1915, the editor of the Cook Inlet Pioneer wrote: “If we are to retain the families, and they compose the backbone of any community, we must provide the children with adequate school facilities. It is highly important that this should be done without undue delay. …”

The federal government finally solved the predicament in late September after commissioners William C. Edes and Frederick Mears convinced the Comptroller General to issue funds for construction of a school house.

Completed in November 1915, Anchorage’s first school was built to serve about 90 students. From the beginning, residents labeled the school “entirely inadequate,” “unsanitary,” and “of an order of the early eighteenth century.” The school lacked a solid foundation, paint and a satisfactory heating system, and its unheated outdoor toilets didn’t meet townsite standards.

Edes ordered Andrew Christensen to take over the responsibility of “school director in addition to your other duties,” in 1917. Although school board members A.J. Wendler, Mrs. W.T. Normile and M. Finkelstein had handled the first year of operation admirably, enrollment had doubled to more than 200 pupils by the fall of 1917. The school also had management problems. One teacher taught 70 primary students in half-day shifts.

Christensen told the principal he “must quit going to the pool halls and must get down to business,” and he advised one teacher “to stop gossiping, complaining and criticizing, and to bring her work up to standard.”

That one-room school house was used only for overflow after a second school, finished in December 1917, opened on the School Reserve. The three-story structure (pictured above), known as Pioneer School, had all the modern conveniences. Soon it was maintained day and night, with seven teachers and 300 schoolchildren attending classes by day and 10 teachers and about 200 students in the building in the evenings, according to information on the photograph.

It served both elementary and high school students until the mid-1930s.

Pioneer School now sits at Third Avenue between Eagle and Denali streets and is used as a public meeting place.

The post School Days Delayed in Early Anchorage appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

May 21, 2014

Alaska history filled with law and order on high seas

This 1907 photograph shows a little cub, carried as a pet on board the U.S. Revenue Cutter Bear, after he climbed up the ship’s rigging. The little guy appears to have a line tethered to the deck.

A “floating court” of sorts evolved when justice was meted out from the decks of revenue cutters beginning in the late 1880s. And Capt. Michael A. Healy, commander in the U.S. Revenue Marine (precursor to the U.S. Coast Guard), became the first revenue cutter commander to make regular patrols into the harsh Arctic waters. He was about the only source of law in a lawless land and transported criminals on board the cutter Bear from remote Alaska communities to Sitka for trial.

Healy began his 49-year sea career in 1854 at age 15 when he signed on as a cabin boy aboard the American East Indian Clipper Jumna bound for Asia.

The son of a Georgia plantation owner and an African slave from Mali, Healy quickly became an expert seaman. He requested and was granted a commission as a third lieutenant in the U. S. Revenue Marine from President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War.

After serving successfully on several cutters in the East, Healy began his lengthy service in Alaska waters in 1875 as the second officer on the cutter Rush. He was given command of the revenue cutter Chandler in 1877. Promoted to captain in March 1883, he then was given command of the cutter Thomas Corwin in 1884. Finally, in 1886, he became commanding officer of the cutter Bear, taking her into Alaska waters for the first time. Here Healy remained until 1895.

He became a legend enforcing federal law along Alaska’s 20,000-mile coastline. In addition to befriending missionaries and scientists, he rescued whalers, Natives, shipwrecked sailors and destitute miners, according to the U.S. Coast Guard.

The captain often drove himself and his crew beyond the call of duty, as in 1888, when the Alaska whaling fleet was anchored behind the bar at Point Barrow to ride out a southwest gale. The wind veered to the north, and huge waves broke over the bar. Four ships broke apart and sank, tossing the ships’ crews into the icy waters. Healy and the Bear’s crew saved 160 whalers, Coast Guard records show.

Healy also assisted in serving the humanitarian needs and welfare of Native Alaskans through the introduction of reindeer to Alaska in order to replace the declining whale and seal populations, which were among the Natives’ primary food sources.

While serving as second-in-command of the Thomas Corwin as it searched for the lost exploration ship Jeanette along the Siberian coast in 1881, he noticed that the Chukchi people were able to sustain themselves by raising reindeer. In 1890, Healy used that knowledge to work with Dr. Sheldon Jackson and famous naturalist John Muir to import reindeer to Alaska.

At his own expense, Healy transported 16 reindeer from the Natives of the Siberian Coast to the Seward Peninsula. In 1892, another 171 reindeer were added to the herd and Teller Reindeer Station was established. More reindeer followed. These selfless acts and humanitarian efforts helped Natives continue their subsistence ways and probably saved many lives.

The captain was sidelined for a few years following a controversial court-martial conviction for “tricing” some of his crew, although the practice of lashing up deckhands with arms behind their backs and toes just touching the deck was legal punishment at the time.

Healy was given command of the cutter McCulloch in 1900 when the gold rush called for more cutters. He then spent his last two years of service on Alaska waters aboard the cutter Thetis and retired in 1904 at the mandatory retirement age of 64. He died the next year.

For his service to his country, the Alaska Native people and to their way of life, Healy was honored by Congress, the whaling industry, missionary groups and civic organizations on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. He earned the nickname “Hell Roaring Mike” for his forceful leadership and determination to succeed in all missions, whether military or humanitarian, and some say for his actions when under the influence of alcohol.

The post Alaska history filled with law and order on high seas appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

May 13, 2014

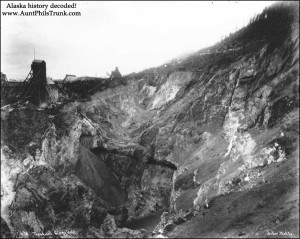

Juneau ‘Glory Hole’ yielded tons of Alaska gold

A bird’s eye view shows the great depth of the “Glory Hole” at the Treadwell Mine on Douglas Island circa 1900.

A gambler’s hunch compelled California mining magnate John Treadwell to purchase a claim near Juneau from “French Pete” for $400. That decision turned into the discovery of the famed “Glory Hole,” located on Douglas Island in Southeastern Alaska, in 1881.

Treadwell Mine, which over time grew to use 900 stamps, became one of the largest quartz lode mines in the world. It was so deep that men working at the bottom and along the sides appeared scarcely larger than flies when one looked down on them from the top.

Ella Higginson recounted her experience of dropping down into the mine in 1905 in her book, “Alaska: The Great Country.”

“…there was barely room on the rather dirty ‘lift’ for us. We stood very close together. It was dark as a dungeon.

“As we started, I clutched somebody – it did not matter whom. I also drew one wild and amazed breath; before I could possibly let go of that one – to say nothing of drawing another – there was a bump, and we were at a level 1,080 feet below the surface of the earth.

“We stepped out into a brilliantly lighted station, with a high, glittering quartz ceiling,” Higginson continued. “The swift descent had so affected my hearing that I could not understand a word that was spoken for fully five minutes.”

The scenes which met Higginson’s eyes included shafts, ore bins, drifts, levels, stations where quartz-laden cars passed and stopes, which were areas where the ore was removed.

Tram cars, each drawn by a single horse, carried ore from one location to another.

“One horse had been in the mine seven years without once seeing sunlight or fields of green grass,” Higginson wrote. “But every man passing one of these horses gave him an affectionate pat, which was returned by a low, pathetic whinny of recognition and pleasure.

“Each man worked by the light of a single candle (in a dark stope). They were stoping out ore and making it ready to be dumped into lower levels – from which it could finally be hoisted out of the mine in skips.

“The ceiling was so low that we could walk only in a stooping position. The laborers worked in the same position; and what with this discomfort and the insufficient light, it would seem that their condition was unenviable. Yet their countenances denoted neither dissatisfaction nor ill-humor.”

During its 36 years of operation, the famous mine produced $66 million worth of gold. A cave-in and extensive flooding in 1917 brought its era of prosperity to an end.

The post Juneau ‘Glory Hole’ yielded tons of Alaska gold appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

May 6, 2014

Early Alaska railroader tunnels to Whittier

Alaska Railroad engineer Anton Anderson sought out routes for the “Iron Horse” in Alaska’s wilderness.

One of Anchorage’s earliest settlers carved a name for himself in the Last Frontier. Literally. Anton Anderson engineered the project that pierced through three miles of solid granite to open the Port of Whittier to the railbelt in Southcentral Alaska.

Anderson began his Alaska Railroad career in 1915.

“Tents without floors, pole bunks covered with wild hay for mattresses and no bedding were the accommodations then available,” is how he described the early living conditions of railroad workers. “There was no smiling assistant camp steward to direct the new arrivals to their quarters….

“The bunks were built out of poles in tiers across both ends of the room, similar arrangement to post office boxes. They usually were four feet square and eight feet in depth and were known as ‘muzzleloaders.’

“It was no uncommon sight to find four tiers of such bunks, six bunks wide at each end of the room. Two coal lamps suspended from the ceiling provided illumination to the group who gathered around the central heating stove, or climbed up and down the crude ladders to and from their muzzle-loading bunks. One should not claim to be a real sourdough unless he has spent at least one night in an Alaska muzzle-loading bunkhouse.”

Later Anderson sought out routes for the “Iron Horse” to steam into the Interior and eventually became the railroad’s chief engineer. Through his work, Anderson was instrumental in the development of western Alaska and surveyed and engineered much of the railroad line.

But the feat that he considered to be his greatest achievement was the construction of the Whittier railroad tunnel, about 60 miles south of Anchorage. Crews operated from both ends of the mountain, part of the Chugach Range, drilling toward each other. The following excerpt from the Nov. 22, 1978, issue of The Greatlander Shopping News, tells of the moment they met in the middle.

“Anderson was at the end of one of the shafts, deep in the mountain, when the holing through was about to occur. Under pounding of air hammers, rocks gave way and through a small hole at his feet, Anderson could shout through to the drilling crew on the other side.

‘Where’d it come through?’

Back came a muffled reply, ‘It’s up by our heads!’

Anderson was stunned. What had happened to his careful surveys, the figures determined by triangulation over the tops of a high mountain?”

It turns out that the two shafts were only off by about six inches, an unusual degree of accuracy for such a difficult undertaking. Anderson’s companions had played a joke on him.

A bronze plaque appears above the tunnel entrance, which bear his name, giving credit to the man who engineered the project.

Anderson led a full, productive life in his adopted country. He was location engineer for the Matanuska Valley colonization project, active in the promotion of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Eklutna hydroelectric plant, chairman of the Anchorage Public Utilities and was elected councilman. He also became Anchorage’s 22nd mayor in 1956.

The railroad man resigned as mayor due to ill health late in 1958. He was honored by the Greater Anchorage Chamber of Commerce, which presented him with an honorary life membership in that group.

“The Anchorage area is a better place to live because Anton chose to come our way,” said then Alaska Railroad general Manager Robert Anderson.

Anton Anderson died in 1961 after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease.

The post Early Alaska railroader tunnels to Whittier appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

April 28, 2014

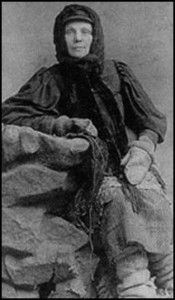

A Mother’s Quest into Alaska-Yukon Wilderness

Anna DeGraf, 55, hiked the Chilkoot Trail on crutches and headed toward the Yukon in search of her gold-mining son in 1894.

Many adventurous souls headed north during the 1890s after prospectors first discovered coarse placer gold in the Yukon River basin on Fortymile River. But a widowed German immigrant who traveled that arduous route was in search of something much more precious: her son.

Anna DeGraf, who lost her husband in a gold-mining accident in the West many years before, climbed the Chilkoot Trail in 1894 at the age of 55. She hoped to find her youngest son, George, who’d left for the gold-filled Yukon region six years earlier.

Wearing a heavy skirt, blouse, warm jacket, cap and heavy boots, DeGraf hiked the trail on crutches while carrying her sewing machine and a feather bed. She later wrote:

“I was so impressed I felt I could never go on. Some of the party were impatient and wanted to push ahead. ‘Oh, come on,’ they said. ‘We don’t care about scenery, we want to find gold.’

“I exclaimed aloud, ‘My God, how beautiful you have made the world!’ We camped there overnight and the next morning started over the deep crevasses in the ice. One misstep might have sent us into oblivion.”

When the widow heard that a man named DeGraf had passed through the Interior, she continued toward the Yukon to join her son. Weather forced her to winter in Circle City, where she found work sewing tents for the Alaska Commercial Company, owned by Jack McQuesten and his wife, Katherine.

DeGraf asked everyone she met if they had news of her son. She spent two winters in Circle City sewing tents, as well as dresses for dancehall girls, before selling her sewing machine and heading to San Francisco to be with her daughter.

In 1897, after hearing of the Klondike strike, she exchanged her gold dust for $1,200 cash, bought another sewing machine and bolts of fabric, and headed north again over the Chilkoot Trail, hoping to locate her son.

Ultimately DeGraf traveled north seven times. Along with Circle City, where she helped start the first school, her search took her to Dawson, Whitehorse, Skagway and Juneau. She supported herself with her sewing machine and befriended miners, dancehall girls, theater performers and Alaska Natives.

At the age of 78, she finally left Alaska for good after she learned about the birth of a great-granddaughter in San Francisco. She found employment as a wardrobe mistress with the Pantage’s theater company in the Bay area and worked there until she turned 90 in 1929.

The following year she died, never having heard from the son whose disappearance first sent her over the Chilkoot Trail.

The post A Mother’s Quest into Alaska-Yukon Wilderness appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

April 21, 2014

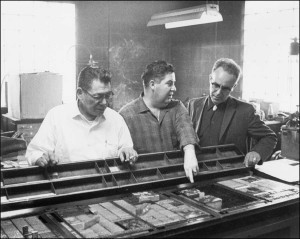

Howard Rock’s light lives on

Howard Rock, left, along with Theodore Hetzel and Tom Snapp discuss printers’ type blocks and plates.

One of Alaska’s most respected men died this week in 1976. Howard Rock, editor of the Tundra Times newspaper, united Alaska’s Native people and helped lead them into the new world when crude oil and land claims dominated the news.

In 1911, near the village of Tikigaq, Rock’s shaman grandmother predicted he would become a great man. More than 50 years later, the prophecy came true. Rock, small in stature, did indeed become a giant among men.

In October 1962, the Point Hope Eskimo was asked by the Arctic Slope Native Association to start the Tundra Times with Fairbanks journalist Tom Snapp. Through the newspaper, Rock changed the way many Native people saw themselves by actively encouraging them to have pride and respect for their heritage and cultures – and to fight for them.

“He was the most soft-spoken man,” said reporter Tom Richards, who worked at the Tundra Times from 1968 to 1974. “But he had tremendous impact with just a few words.”

After taking on the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to prevent an Arctic atomic test project, Rock used the Tundra Times to fight the federal government on behalf of Aleuts virtually enslaved in the Pribilofs.

Rock, through his newspaper, unified Alaska Natives by “knowing the hearts and minds of the people,” Alaskan leaders said.

At a time when there was often disharmony around the state, Rock pushed for the formation of a statewide gathering of Natives, helping to set the stage for the first Alaska Federation of Natives convention.

“Perhaps more than anyone else, he (Rock) helped weld together the frontier state’s 55,000 Natives for their successful years-long fight to win the largest aboriginal land claims settlement in American history,” wrote Stan Patty of the Seattle Times. He added that Rock was their voice; at times about the only calm voice when crescendos of dissent threatened to tear Alaska apart.

Thanks in part to Rock’s activism, the fledgling AFN began demanding land and money from the federal government. When the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was signed into law in 1971, Rock hailed its passage as “the beginning of a great era for the Native people of Alaska.”

In 1975, Rock’s leadership was recognized with Alaska’s Man of the Year award, which he shared with U.S. Sen. Ted Stevens. That same year, the newspaper was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for meritorious public service.

Rock died of cancer on April 20, 1976.

“I’ve never seen anybody die the way Howard died – he went in a blaze of glory,” Richards said. “His eyes had a burning light.”

A granite headstone and the rib of a giant bowhead whale, which typically pay tribute to a mighty hunter, mark his final resting place in the Tikigaq tundra about a mile from Point Hope. But Rock’s legacy – that of Native unity and activism – lives on.

The post Howard Rock’s light lives on appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

April 14, 2014

Seward’s Folly becomes U.S. Treasure

Russia officially turned Alaska over to the Americans in October 1867 in the Southeast town of Sitka, seen here in the 1880s.

On April 9, 1867, by a margin of just one vote, the U.S. Senate voted to ratify the treaty to purchase Alaska from Russia. The purchase of the northern frontier was ridiculed by the press at the time and called “Seward’s folly,” “Seward’s icebox” and President Andrew Johnson’s “polar bear garden.”

But its main architect, Secretary of State William Seward, saw a huge benefit to owning the land that sat so close to Russia.

“Standing here and looking far off into the northwest, I see the Russian as he busily occupies himself in establishing seaports and towns and fortifications on the verge of the continent … and I can say, ‘Go on and build up your outposts all along the coast, up even to the Arctic Ocean; they will yet become the outposts of my own country – monuments of the civilization of the United States in the northwest!’ ”

So predicted Seward in a memorable speech many years before the purchase took place. That Alaska came into the possession of the United States was almost wholly due to Seward’s foresight and persistent efforts.

The Imperial Government of Russia first approached the U.S. government with a secret offer to sell its Russian possessions in America in 1859. The Russians had expended vast amounts of capital during the Crimean War in a futile struggle with France and England and needed to replenish the royal coffers.

However, with the Civil War raging during the early 1860s, the United States didn’t pursue the purchase of Alaska until March 1867 when Seward received word that the Russians were ready to unload their northern property.

Seward was playing a game of whist with members of his family when he was interrupted by a late call from Russian Ambassador Baron Edouard de Stoeckl, who came to announce the arrival of a dispatch from St. Petersburg conveying the Emperor’s assent to the cession of Alaska to the United States.

The Russians wanted “a cash payment of $7 million, with an additional $200,000 on condition that the cession should be free and unencumbered by any reservations, privileges, franchises or possessions by any associated companies, corporate or incorporate, Russian or any other.”

The Secretary of State abandoned his game of whist. He and the Russian ambassador collected their clerks and had the treaty ready for transmission to the U.S. Senate by sunrise.

But many legislators didn’t think the purchase was a good idea. “… that Alaska was created for some purpose I have just as little doubt as I have had since the Rebellion of the necessity for the infernal regions …,” one member of Congress said. Most Americans at the time also thought the idea fantastic and ridiculous. Some asked, “How can there be anything of value in that barren, worthless, God-forsaken region.”

Six months after the Senate ratified the purchase, Russia officially turned Alaska over to the Americans in a ceremony held in Sitka. And since the hand off, Seward’s “God-forsaken region” has yielded millions of dollars in resources for its sister states, including furs, fish, coal, copper, gold and crude oil.

The post Seward’s Folly becomes U.S. Treasure appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

April 8, 2014

Russian settlement near Sitka attacked 1802

The Russians built a stronger trading post after Tlingits attacked and burned the original settlement near Sitka in 1802.

Scientists plan to travel to the Aleutian Chain of Alaska this summer to see if they can find evidence of a Russian attack on the Aleut people that happened 250 years ago. They will be looking for bullets and other artifacts that would confirm stories that have been passed down for generations.

There have been many stories about the brutality of Russian fur traders and merchants upon the people of Alaska that date back to first contact in the mid-1700s. There’s also record of Alaska’s people rebelling against the Russians in other parts of the Great Land, including Southeast Alaska.

After finding a spot about six miles north of the present town of Sitka, Alexander Baranof – chief manager for the profitable and influential Russian American Company – exchanged beads and other trading goods for a small piece of Tlingit ground on which to erect a Russian settlement in 1800.

Although the inhabitants of the new trading post became less fearful of an attack from their Tlingit neighbors during the next two years, the Natives in the area remained sullen and hostile toward the Russian intruders. And by 1802, they were ready to take back their land.

That summer, while Baranof was away in Kodiak, a horde of warriors quietly crept out of the woods and climbed over the stockade at Mikhailovsk before any alarm was made.

The Russians attempted to barricade the main buildings, but the assailants broke down the doors and windows and poured into the settlement.

A hunter, who survived the massacre and destruction of the fort, later told his tale:

“In this present year 1802, about the 24th of June – I do not remember the exact date, but it was a holiday – about two o’clock in the afternoon, I went to the river to look for our calves, as I had been detailed by the commander of the fort, Vassili Medvednikof, to take care of the cattle.

“On returning soon after, I noticed at the fort a great multitude of Kolosh people, who had not only surrounded the barracks below, but were already climbing over the balcony and to the roof with guns and cannon; and standing upon a little knoll in front of the outhouses, was the Sitka toyon, or chief, Mikhail, giving orders to those who were around the barracks, and shouting to some people in canoes not far away, to make haste and assist in the fight.”

The Tlingits soon slaughtered the males within the settlement and carried the women and children away as slaves. After emptying out the buildings, they set fire to the compound and retreated back into the woods and their villages.

The hunter spent eight days hiding in the woods until he spotted an English ship in the bay and then told its commander his story.

Capt. Barber accompanied the hunter to the destroyed fort, where they examined and buried the dead. He then seized the Tlingit chiefs and threatened to hang them if they did not hand over all captives and possessions taken from the Russian post.

The commander took the returned survivors to Kodiak, where he demanded Baranof pay him 50,000 rubles in furs as ransom. Baranof, learning that the captain’s only expense had been in feeding and clothing his passengers, paid him 10,000 rubles for the release of three Russians, five Aleut men and 18 women and children.

In April 1804, Baranof returned to Sitka with four small ships and 300 canoes, along with a crew of 121 Russians and 800 Aleuts. He retook the fort, erected a stronger stockade and buildings and renamed the settlement New Archangel.

Following the purchase of Alaska from the Russians in 1867, it was renamed once more. Sitka – Tlingit for “by the sea” – is Alaska’s fourth most populated city today. It has the largest harbor system in Alaska, with more than 1,350 permanent ships, and is the sixth largest port by value of seafood harvested in the United States.

The post Russian settlement near Sitka attacked 1802 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.

April 1, 2014

Massive Earthquake Shakes Alaska in 1964

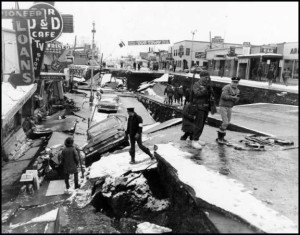

The Good Friday Earthquake on March 27, 1964, destroyed many businesses on Fourth Avenue in Downtown Anchorage. Along with National Guardsmen, U.S. Army soldiers from nearby Ft. Richardson helped guard the ravaged city.

It began with a gentle roll on March 27, 1964. Then the ground surged. Waves, like those on water, rippled across the earth. Cracks up to 30 feet wide formed, and then snapped shut. People clutched light poles, parking meters and anything else they could grab to keep from being hurled to the ground.

Few who experienced the Good Friday earthquake 50 years ago will ever forget where they were at 5:36 p.m. when the magnitude 9.2 quake hit Southcentral Alaska. The largest earthquake in North American history devastated many communities and altered more of the earth’s crust than any other earthquake on record.

The massive quake disrupted an area of 185,000 square miles. Some areas dropped as much as 8 feet, others rose 38 feet. The quake killed 143 people from Alaska to California. A few were crushed. Several drowned. Some buried.

Alaskans understand that earthquakes are part of life in the Last Frontier. More than 10,000 earthquakes occur at various depths and magnitudes each year – that’s more than the number of quakes reported in the other 49 states combined.

In fact, earthquakes have been shaping Alaska’s landscape for centuries. Their handiwork can be seen from islands rising up in the Aleutian Chain to the country’s riverbeds, glaciers and mountains.

Most early earthquake accounts are fragmented. There are mentions of two in the Aleutians and the Alaska Peninsula as early as 1786 and 1788, when “the land was overflowed by a sea wave, and some lives were lost.”

Another on April 2, 1836, shook the entire coast of Southeast Alaska and triggered a series of waves that threatened to wipe out the town of Sitka. Several earthquakes rocked the area again near Yakutat in September 1899. A few Natives and prospectors witnessed a 30-foot wave hit land. Sitka continued to have quakes, including a severe shaker in 1917, and again in 1927, that stopped clocks and cracked buildings.

On a fine June evening in 1958 a monster shaker registering 8.0 on the Richter scale hit a vast area of Southeastern Alaska and northern British Columbia. At about 10:15 p.m. the earth shook so violently that glaciers moved in Lituya Bay near Yakutat.

Geologists say there is a great “loose joint” in the earth’s crust at Lituya Bay. Some of the world’s mightiest peaks and glaciers lie astride it, and when earthquakes occur, mountains twist, shake and tumble around.

But so far, Mother Nature hasn’t succeeded in shaking Alaskans off the land!

The post Massive Earthquake Shakes Alaska in 1964 appeared first on Aunt Phil's Trunk.