Quinn Reid's Blog, page 22

October 18, 2011

How Can Bad Relationships Feel So Right?

I've been doing a lot of reading lately on schema therapy and mental schemas, a subject I've written about here a number of times: see links on my Mental Schemas and Schema Therapy page. One of the most intriguing insights that's come up in that reading is "schema chemistry." What's schema chemistry? The short version is this: sometimes the people we are most strongly attracted to are the ones who are the most likely to make us crazy.

I don't want to overstate this: I don't imagine for a minute that all love, romance, chemistry, and attraction are based on people fitting their mental baggage together–but it's pretty fascinating that some of it seems to be, for some people.

The apparent reason schema chemistry happens is that the kinds of troubles we're used to are comfortable and normal-feeling to us, so a person who causes the same problems we're used to will feel more familiar and closer. If Mary grew up in a house where her parents always left her alone, she might very well feel more "at home"–not happier, but in more familiar and "right-feeling" territory–if she dates someone who always leaves her home alone, too. If Jack's mom was always telling him he was a hopeless screw-up, he might have more respect for and feel more familiar with a girlfriend who always tells him the same thing.

According to some accounts in Schema Therapy: A Practitioner's Guide by Drs. Jeffrey Young and Janet Klosko, it appears this isn't always a mild effect, either: sometimes it really makes the sparks fly.

As you might expect, this can be bad news. Two people might fall madly in love, have a breathtaking romance, and then settle down into a pattern of gradually making each other miserable. Apart from breaking up, the best hope for a couple like this is often to get couples therapy–I'd be inclined to suggest couples schema therapy specifically–and to learn there not only how to handle their own emotional baggage better, but also how not to push the other person's destructive buttons.

Here are a few more examples of schema chemistry:

A person who feels defective (the Defectiveness schema) gets together with a person who feels like people should be punished for even small mistakes (the Punitiveness schema)

A person with a sense of being better and more deserving than other people (the Entitlement schema) gets involved with someone who is constantly taking care of other people at the expense of their own needs (the Self-Sacrifice schema)

Someone who grew up feeling lonely and neglected in a house where there was very little nurturing or expression of love (the Emotional Deprivation schema) dates someone to whom expressing emotions seems unnecessary and disturbing (the Emotional Inhibition schema).

There are any number of combinations, given that there are 18 different schemas and a variety of ways to express each one. Fortunately, there are many other factors to bringing two people together than schema chemistry. Here's hoping it's not at work in your relationship! If it is, just becoming aware of how the two schemas interact may start to help. I'm working on a short, informal book on mental schemas that I hope will make it easier for people to gain insights on their own and others' schemas; it should be out in November or December. For information on that, stay tuned.

Photo by jb_brooke

October 14, 2011

15 Ways to Avoid Embarrassment Over Your Young Adult Fiction Habit

Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, Twilight, even A Wrinkle In Time … technically, these books were never meant for those of us over the age of 18 or so. As Young Adult (or in the case of Harry Potter, Middle Grade) fiction, they were intended for the younger generation, and yet adults–by which I mean possibly you and definitely me–are still reading them by the bookmobileful. I think we're supposed to be reading more serious stuff–maybe The Grapes of Wrath, or Moby Dick … War and Peace is probably good. I always tell people I'm reading War and Peace, and I'm at that part right near the end. This helps make sure they'll change the subject quickly so that I don't have to prove I don't know what it's about. Except, you know, obviously war, and also peace. Probably there's something there about Russia invading … I don't know, somebody. Maybe Russia invading Russia. Russia is pretty big: they could probably get away with that.

Anyway, my point is that it's not always impressive and mature-sounding to say "Oh, I just read this great book written for 12-year-olds …" Here, as a public service, are some excuses writers and readers can use to cover for an addiction to young adult fiction.

I have a teen at home, so I have to know what they're reading to be a good parent.

I work with teens, so I have to know what they're reading to do my job.

I know my kid is only four, but I have to be up to speed by the time she hits middle school.

While I don't have or work with kids now, I might someday, and it's better to be safe than sorry.

I mistook it for the latest long, boring novel about the grim reflections of an emotionally deprived settlement camp volunteer. That's what I really meant to read.

I'm a writer, and that market's hot right now.

I'm a writer, and I just want to make sure that I know what's Young Adult so that I don't write some by mistake.

Actually, I'm pretty sure Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is classified as a technothriller.

What, that? That's not mine.

Well you know, it's interesting: it turns out that there are moral and ethical threads to the subtext that really delineate an entirely separate and more cerebral story not immediately evident if you don't really dig in, but that with energetic literary analysis really emerges with a characteristic–wait, come back! Don't you want to hear about the affective parallelism?

Young adult fiction is where all the really steamy stuff is these days. Who wants to read about two old people doing it?

Oh, I just have that because I'm translating it into Serbo-Croatian.

That's just one of the fake covers I use to hide my D.H. Lawrence books.

That's from when I was a kid. I only read eBooks now.

Yes, I'm reading young adult fiction. When's the last time you read a book you couldn't put down?

October 12, 2011

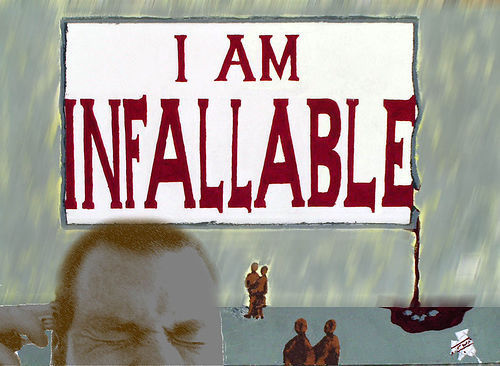

Mental Schemas #18: Punitiveness

This is the 18th of 18 mental schema posts from my series on schema therapy, an approach to addressing negative thinking patterns that was devised by Dr. Jeffrey Young. You can find an introduction to schemas and schema therapy, a list of schemas, and links to other schema articles on The Willpower Engine here.

I have often been severe in the course of my life towards others. That is just. I have done well. Now, if I were not severe towards myself, all the justice that I have done would become injustice. Ought I to spare myself more than others? No! What! I should be good for nothing but to chastise others, and not myself! Why, I should be a blackguard!

– Inspector Javert in Victor Hugo's novel Les Misérables

The Punitiveness schema is a lifelong conviction that people should suffer if they don't follow the rules. People with this schema feel the responsibility to be angry and to ensure punishment is given out, whether to family members, employees, acquaintances, strangers, or themselves. They tend to feel they have a strong moral sense and that their insistence on punishment is about justice and fairness, and they have a hard time forgiving other people or forgiving themselves. They don't generally consider reasonable circumstances that could explain what they see as bad behavior, and the idea that people are imperfect and just make mistakes sometimes doesn't usually enter into their thinking. The standards applied in a Punitiveness schema are usually pretty high, too. Wiggle room is a foreign concept.

The Punitiveness schema is a lifelong conviction that people should suffer if they don't follow the rules. People with this schema feel the responsibility to be angry and to ensure punishment is given out, whether to family members, employees, acquaintances, strangers, or themselves. They tend to feel they have a strong moral sense and that their insistence on punishment is about justice and fairness, and they have a hard time forgiving other people or forgiving themselves. They don't generally consider reasonable circumstances that could explain what they see as bad behavior, and the idea that people are imperfect and just make mistakes sometimes doesn't usually enter into their thinking. The standards applied in a Punitiveness schema are usually pretty high, too. Wiggle room is a foreign concept.

It's sometimes hard for people with Punitiveness schemas to get close to others because of a tendency to get angry easily and to react harshly to errors of any size.

A harsh, critical tone or moral inflexibility can indicate that a person may be saddled with a Punitiveness schema.

Schemas that can go along with Punitiveness

People with this schema in many cases have been treated very badly in childhood, and such people often have an added schema called Mistrust/Abuse, which leads them to assume that people will usually act badly and take advantage when given the chance.

Another schema that can commonly occur along with Punitiveness is Unrelenting Standards, which is a habit of having such difficult requirements for good conduct that they're virtually impossible to meet.

The Defectiveness schema, too, fits well with Punitiveness. People with Defectiveness schemas have a deep-down conviction that they're not good enough, that they're fundamentally flawed, contemptible, and not worthy of love. A sense of Defectiveness can drive people to want to punish themselves, and punishment can reinforce people's feelings that they are defective.

Where Punitiveness schemas come from

People with Punitiveness schemas often grew up in families where parents were harsh or even abusive when a child made a mistake. Parents or other major figures during a person's childhood may have been critical and perfectionistic. Children in such families may grow up with a sense of harsh punishment as normal, just the way things are; they can feel that when someone makes a mistake and isn't punished, it's a miscarriage of justice and a serious problem. As we grow up, we tend to internalize some of the things our parents say or do to us, and people with this schema learn to have a voice inside them that demands everyone do things the right way or they'll be sorry.

Overcoming a Punitiveness schema

The Queen turned crimson with fury, and, after glaring at her for a moment like a wild beast, screamed 'Off with her head! Off—'

'Nonsense!' said Alice, very loudly and decidedly, and the Queen was silent.

– from Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

It's hard to change from thinking that people who do things wrong should be punished to the idea that they should be forgiven or ignored much of the time, but this is exactly what needs to happen to transform a Punitiveness schema. Even more than with most other schemas, it can be very valuable for people with a Punitiveness schema to weigh the pros and cons of their schema-driven actions. In addition to the obvious problems with this schema, like feeling bad a lot of the time and others not wanting a person with this schema around, it's also the case that punishment is a pretty lousy way to change behavior most of the time, if you're willing to believe the research. Punishment tends not to make people reconsider the actions they were punished for as much as it encourages them to find ways to avoid punishment in future, or just generates anger and resentment. Even people who are responsive to punishment are often just acting out their own schemas. For instance, people with a Defectiveness schema won't usually take punishment as encouragement to become a better person, but instead will take it as proof that they're horrible and deserve to be punished.

Forgiveness and discussion instead of punishment are especially important in parenting, where excessive punishment tends to create the same schemas in children that we've talked about above: Punitiveness, Mistrust/Abuse, Defectiveness, and Unrelenting Standards. Parents may consider it their duty to get angry at their children and punish them, but a little of this goes a long way–sometimes far too long–and much more effective parenting strategies are easy to find in a library or local parents' group.

People working to shake off a Punitiveness schema can benefit from reflecting on circumstances that contribute to behavior they think is bad, from considering people's intentions in addition to their actions, and in general by building the ability to empathize and forgive. Punishment isn't necessarily ruled out, but the idea is to restrict it to, at most, people who have bad intentions as well as bad actions, or people who are severely negligent, whether or not those people should be punished becomes a broader ethical question.

October 5, 2011

Writing and Martial Arts 3: On Mushin and Ignoring the Footwork

This is guest post by Donald Mead is part of the "Writing and the Martial Arts" series, in which other writer/martial artists talk about parallels between these two seemingly very different disciplines.

Donald Mead is a Writers of the Future winner, and his work has also appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Strange Horizons.

You may be interested in the two earlier posts in the series, both by black belt, professor of History and Philosophy, and fantasy novelist Steve Bein: "How Do You Like Your Chances?" and "Writing and Punching."

In Japanese martial arts culture, the pen and sword exist together as equals. This contrasts with the Western adage: "the pen is mightier than the sword." The historical roots of the Japanese view come from certain restrictions imposed by the Tokugawa Shogunate and from Bushido, the philosophy of the warrior. Both of these topics are as dull as they sound.

I've found surprising similarities between martial arts and writing that are much more personal, in particular, the concept of mushin or empty mind.

Me? I have black belts in Shotokan karate, kendo, iaido and minor training in a variety of other arts. Thirty years of training in all, and I have to admit, I'm tired, but I've learned a few things.

One of those arts I mentioned is iaido, which is the Japanese sword art of drawing, cutting and returning the blade to its saya (scabbard). I've also had years of training in Shinkendo, which is an Americanized version of Japanese sword. Both of these arts make use of two-person exercises in which one person cuts at the defender, and the defender blocks. The number of cuts and blocks increases with the skill level of the students. Mind you, this isn't kendo with its flexible bamboo swords and thick padding from head to toe. In this traditional art, the participants have no armor and use solid-wood bokken (wooden swords).

Once, we invited a Japanese instructor from California to lead a seminar. We learned a rather fast and dynamic two-person exercise–a series of cuts and blocks moving in a square. Step-cut, block, step-cut, block, cut and square up to your partner. Hard to describe–harder to do. There's a lot to keep in mind in these types of exercises. The cut has to be aimed at the head or your partner has no reason to block. The block has to be at the correct height and angle or you'll end up with a cracked noggin. And of course, there's footwork. It's a dance with consequences more serious than stepped-on toes.

After class, we treated Sensei to dinner and a couple of drinks. Someone asked about the footwork of the exercise and Sensei responded "Oh, there is no footwork in this art."

This had all of us more than befuddled since Sensei had been pounding us about footwork for the past three hours. Here's what he meant we eventually figured out. We learned a new exercise that required us to concentrate on technique: footwork, cutting angle, blocking, distancing and timing. We went slowly over the months, breaking down each move and smoothing out the bumps (figurative and literal). We celebrated small milestones like getting all the way through without tripping over ourselves. Later, we felt brave enough to speed up–not as fast as Sensei, but pretty good. Within a year, we were doing the exercise with no hesitation. There was no thought of our feet, or of getting

our fingers bashed or the effectiveness of the block. We were simply building and maintaining the energy of the exercise that flowed from one side to the other. That's mushin–the mind doesn't stop to think about technique or safety. That's all built in now–instinctual. But you're not empty-headed either. You have a partner, and you're having a non-verbal conversation. To the participants the swords and footwork are gone, but the energy of the conversation is real and quite pleasant in most cases. That's what Sensei meant when he said the art had no footwork. A student might begin with footwork, but at an advanced level, the footwork doesn't matter at all.

I was a white belt when I started writing fiction. A beginner. I didn't know that at the time; I thought I had all the tools I needed to write. I took one of my stories to a writers' workshop at Chicon 2000 and had an eye-opening experience. I mean, what was this point of view thing the pros kept harping about? And what was wrong with my thirty adverbs per page? They didn't even like my surprise ending where the main character wakes up, and it was all a dream. Yep, it was that bad.

I had to learn how to write step by step. Just like a martial arts student learning the cut, block and footwork, I had to learn the basics of prose, and that took concentration. My flabby verbiage had to go along with most of those adverbs and passive sentence structure. Then I had to think about my stilted

dialogue and how to smooth it out. Finally, I had to think of the story as a whole–the use of tension, the motivation of my characters, the believability of the fantasy element and a satisfying and logical ending.

You know that "million words" saying? I my case it applied; I wrote at least a million words before my writing noticeably improved and I started making sales. But by that millionth word, I wasn't thinking about the prose anymore. All of those writing rules, the traditional ones and my personal ones, were all instinctive. I saw a picture of the story in my mind, and my hand moved over the paper. It wasn't perfect mind you, a fact my critique group is quick to remind me, but the fundamentals were there now.

I bet you've been there–writing in the zone. When the story takes off and your hand can barely keep up. That's mushin.

October 4, 2011

News Fasting: Is There Too Much News in Your Life?

Years ago I read a book that advised going on a "news fast"–that is, not watching, listening to, or reading the news for at least a week. The idea seemed strange to me: I was listening to the news in my car every day on the way into work and back. If I didn't keep up with the news, wouldn't I be uninformed? Wouldn't I miss important things?

Well, maybe. I mean, if I were an investment counselor, I'd need to keep up with financial news. Almost everyone can use weather reports–though we can get that online without going near any other kinds of news. I certainly need to know something about what's been going on in politics sooner or later if I'm going to vote responsibly. On a day-to-day basis, though, is news actually doing me any good?

News and stress

I could phrase this question another way: is what I get from keeping up with the news worth the stress it causes me?

Because it's definitely stressful. I listened to NPR while in the car this morning and ended up turning it off after 20 minutes, because it had already managed to offer me stress-producing material about 1) biased journalism, 2) world overpopulation, 3) declining birth rates (notice how this is in direct conflict with #2 and yet each offers things to worry about), 4) drug shortages, and 5) invasive plant species.

I'm not advocating not knowing about these things. The dangers of overpopulation should (if you ask me) figure into any family planning discussion. There are practices I can avoid, like bringing unchecked fill onto my property, that can help limit the spread of invasive species. Having a sense of how responsible my sources of information are helps me take their statements in a more well-considered light.

What's the news for, anyway?

Yet on the whole, the news tends to be filled with things to worry about, very few of which we can do much about directly unless we choose to make it a key personal mission. There are some positive stories, but they're rare. You've probably heard the saying "If it bleeds, it leads": people pay more attention to the news–watch more, listen more, and read more–if something bad is happening. Imagine a newspaper with a huge front page headline: "Everything is fine; not much to worry about!" It might have novelty value, but if it began to happen regularly, people might well stop buying newspapers.

When we listen to something negative on the news, we have three choices: we can do something about it right away, we can ignore it completely, or we can keep it in mind. Since we can rarely do anything about corruption in Afghanistan or declining salmon populations right away, and since ignoring is difficult and seems counter-intuitive when we've gone out of our way to get the news in the first place, we do a lot of just keeping things in mind. Does this make us better people? Does it help us make better decisions?

For that matter, are we even necessarily better informed? The news often emphasizes the unusual, the shocking, or the disturbing, making the world seem more extreme and upsetting than it actually is. "Two people fall in love, have minimal relationship problems, and live happily together into old age" isn't usually news, but knowing that things like that happen is crucial in terms of how we experience our lives. News tends to skew the way we view the world. It's depressing. It's stressful.

Less news is good news

So what am I advocating here? Just that if you're in the habit of listening to, watching, or reading the news every day, you might want to try taking a vacation for a while. Also, when you come back from that vacation, you might consider the possibility of limiting your news consumption on a regular basis.

I'd suggest two weeks. One week probably isn't long enough to completely feel the effects, and anything longer runs the risk of making a person feel so out of touch the whole thing might backfire.

But old habits are hard to shake off, so I also recommend substitute behaviors.

If you read your news, whether on paper or online, consider introducing more enjoyable fiction and blogs, magazines, or books on topics you care about into your literary diet.

If you tend to listen on the radio, substitute music (which can be a highly effective mood changer), audiobooks, or just thinking about your life, the things that are important to you, and what makes you happy (see Getting Past Our Own Uncomfortable Silences). If you own a Kindle, you can have it read some books aloud to you (depending on the publisher's settings) by pressing Shift+Sym and using space bar to pause/play. I plug my Kindle into my car's stereo system and "read" articles, blog posts, and books this way. If you enjoy singing, doing more of that–with or without the radio–is another way to boost mood.

If your news mainly comes from the television, consider watching less television and spending the time instead with family or friends, reading or listening to music, or engaging in projects that leave you with a sense of satisfaction and meaning.

I'm not sure there is a perfect balance of taking in the news and staying clear of it. Even though news is often stressful, it's occasionally enlightening or uplifting, and even when it's stressful, sometimes that stress has a purpose (see The Benefits of Feeling Bad). Still, getting large amounts of news on a regular basis seems as though it would enough to increase anyone's stress levels. If you're a daily news consumer, what's it doing to yours?

Photo by matsimpsk

September 29, 2011

New Futurismic Column: Wait, You're Not a Real Writer at All!

Some time back I posted here about Impostor Syndrome, which was a recent topic of discussion on Codex, the online writing group I run. That discussion led to my most recent "Brain Hacks for Writers" column on Futurismic, "Wait, you're not a real writer at all!" which you can read here: http://futurismic.com/2011/09/28/wait-youre-not-a-real-writer-at-all.

Some time back I posted here about Impostor Syndrome, which was a recent topic of discussion on Codex, the online writing group I run. That discussion led to my most recent "Brain Hacks for Writers" column on Futurismic, "Wait, you're not a real writer at all!" which you can read here: http://futurismic.com/2011/09/28/wait-youre-not-a-real-writer-at-all.

You might also enjoy reading Alex J. Kane's follow-up on the subject on his blog.

September 28, 2011

Amazon Announces $200 Tablet, $80 Kindle, and Touchscreen Kindles

In just the past hour or so, Amazon announced the new Kindle Fire, a $200 Android-based tablet that prioritizes reading, music, and media; they also introduced new touchscreen Kindles and a new standard Kindle (with ads and with no keyboard; the version without ads goes for $109) for $79. Prices of existing Kindle models have also dropped substantially.

The tablet and touchscreen eReaders will be available November 21st, in time for the holidays, while the new standard Kindle is available immediately.

I would be very surprised if this didn't mean a host of new eReader users and a rise in sales of Kindle eBooks that starts immediately and builds through Christmas and (if last year is any guide) beyond.

Mental Schemas #17: Unrelenting Standards

This post is part of a series on schema therapy, an approach to addressing negative thinking patterns that was devised by Dr. Jeffrey Young. You can find an introduction to schemas and schema therapy, a list of schemas, and links to other schema articles on The Willpower Engine here.

How good is "good enough"? For a person with an Unrelenting Standards Schema (also called "Hypercriticalness"), only perfection is acceptable: anything less is a disaster.

Unrelenting standards can be expressed in a variety of ways, but the three most common are

Time and efficiency. Some people with this schema feel that it's always necessary to do things efficiently, to use all time productively, to never waste time or do things for purposes that aren't primarily practical.

Perfectionism. A person who expresses the Unrelenting Standards Schema through perfectionism is always anxious that everything go exactly the way it's supposed to, that there never be any flaws or mistakes.

Rigidity. A third group of people with the Unrelenting Standards Schema have an unyielding set of rules, which might be philosophical, moral, religious, practical, etc. When such people see someone not adhering to these rules, they often get involved whether that makes things worse or not. They also tend to be very hard on themselves in the same way, feeling like they've absolutely failed whenever they don't follow meet their own dictates to the letter.

How Unrelenting Standards come out in daily life

To someone who has this schema, their own rules may not seem extreme at all–they may feel like a normal standard. It's only when such a person's expectations are compared to other people's that the differences begin to show themselves.

A lot of people try to do things really well. What's the difference between that and having an Unrelenting Standards Schema? One of the key signs is that an Unrelenting Standards schema causes harm in a person's life. For instance, a normal event like a picnic or a presentation becomes a terrible ordeal because it would feel like a catastrophe if any little thing went wrong. People with this schema may have a hard time enjoying successes. After all, if perfection is the normal way things are meant to be, how is it in any way impressive or special when something is done really well?

Unrelenting Standards often come out in as all-or-nothing propositions. To a person with this schema, a partial success is a failure, and "pretty good" is bad.

People with Unrelenting Standards schemas may find themselves hit hard when they fail to live up to their own impossible requirements. The flip side of perfectionism is avoiding responsibilities altogether and procrastinating, because it's so difficult to face past and possible future mistakes. When such a person finally jars loose from their procrastination, their schema may affect them far more than usual as their excruciating awareness of how badly they've recently been failing to meet their own expectations makes them lash themselves into expecting even more from themselves.

Overcoming an Unrelenting Standards schema

Changing an Unrelenting Standards schema isn't easy, because it means changing ideas that may have been deeply held for a long, long time. Also, a person with this schema will often have a habit of expecting too much of their own efforts, so that a long, effortful struggle against a habit is hard to tolerate. Fortunately, there are strategies such a person can use to transform standards, expectations, and responses to success and failure.

Make risks feel less scary. The risks of failure are often mild compared to our fears of them. Using idea repair to bring things back into proportion and to become OK with making mistakes sometimes takes a lot of the anxiety and discomfort out of trying to get something done.

Get a hobby. This may sound like trivial advice, but for people who can't let go of the feeling that every second has to be productive and efficient or something terrible will happen, getting used to spending time in a non-productive way can be powerful and freeing. My favorite account of this kind of benefit so far is from this blogger, for whom taking up knitting helped drive a sea change in her happiness and self-acceptance.

Make friends with imperfection. Another approach a person with this schema can take is to consciously choose to sometimes do things imperfectly (something the blogger I just mentioned did with her knitting). Being able to do something less than perfectly but still experience the benefits it brings helps put expectations in perspective. For example, it would be terrific if the U.S. Congress could get together on legislation that made the absolute biggest possible impact on the economy, job creation, and deficit reduction, but most of us voters would be pretty thrilled if they would just make some kinds of modest gains in each area, even if it wasn't done in the ideal way.

Do a cost-benefit analysis. This very pragmatic approach tends to expose an unintuitive truth: perfection is inefficient. For instance, consider a situation in which you could get 90% of the juice out of an orange in 2 minutes or 100% of the juice in 5 minutes. A single orange yields about 2 ounces of juice, so that last 10% would be 3 minutes of effort for .2 ounces of juice. If you get paid twenty-five dollars per hour at your job, one eight-ounce glass of perfection juice would cost you $50 in labor under these circumstances. Is the last 10% of the juice worth fifty bucks? Probably not.This same kind of analysis holds true in many situations, personal and professional. When we analyze what perfection costs us compared to pretty good performance, often "pretty good" wins hands down.

That's not to say there's no place in the world for perfection. Sometimes it's worth spending 4 years painting a ceiling. It's just that usually it really isn't.

Are you a perfectionist, a recovering Time Nazi, or is someone in your life driven to never accept anything that is flawed in any way? Talk about it in comments!

Image by fisserman

September 26, 2011

What's the Drug in Your Life? Part II

This post is a continuation of a discussion of addictive behaviors that started in my previous article, "What's the Drug in Your Life? Part I."

Quitting addictive behaviors

Dealing with addictions often needs two things at once: a way to address the problem or problems that made running away attractive in the first place, and a change in habit to stop the addiction. In my case, I moved to a new place where I had a number of supportive friends around me. In this context, it became clear that playing computer games was stupid: it shut out my friends and created problems with them, and it wasn't really necessary because with my friends around me, I wasn't lonely. The fact that I didn't see this in my life until my change in situation broke the pattern is disappointing, but I'm encouraged that I understood myself well enough, all those years ago, to take the step that put me in a situation where I could stop acting addictively.

I hadn't realized it for years, but recent reflection made something obvious to me: the time when I stopped playing computer games was also the time when I started writing seriously again. After years of avoiding writing (following a year or two of earnest effort and no sales right after college), I was working hard once again, and I began to see signs of success early on in that process. It led directly to my being admitted to an exclusive writer's workshop, getting an agent, selling my first book, and winning the Writers of the Future contest.

Putting ourselves in situations where we have more supportive people in our lives on a day to day basis makes a huge difference. This can be accomplished sometimes by moving, by making different lifestyle choices, by starting a new activity (check out the free site www.meetup.com for regular activities in your area), by participating in group therapy, or by re-energizing relationships with friends or family. A bonus of this approach is that increased time spent with supportive friends, family, and acquaintances cuts into addiction time, helping address the problem both directly and indirectly. Of course, it's counter-productive to spend more time with people if they're encouraging taking part in the addictive behavior; avoid that pitfall!

Counseling (my personal recommendation would usually be to work with an experienced cognitive therapist of some kind) can also help: when we identify what the problem or lack was that helped drive the addictive behavior in the first place and take steps to change that in our lives, the addiction loses a lot of its power.

Benefits of quitting

More benefits can come from beating an addiction than might be immediately obvious. Of course the ongoing damage the addictive behavior was doing is gone, but another major benefit is that our brains eventually return to handling dopamine in a normal way, making other activities more pleasureable. The addiction also yields time to do other things, opening up the possibility for more pleasure and improvements in our lives.

Quitting an addiction is also seen as a mark of strength and character by other people; being successful in this tends to raise our opinion of ourselves as well as other people's opinions of us.

Finally, quitting an addiction opens up the opportunity of stepping up and facing whatever problem contributed to the addictive behavior in the first place. Is it loneliness? Fear of failure? Depression? All of these are much easier to address without an addiction in the way to complicate things.

So, while I hope your answer is "I don't have one," let me ask you this question: what's the drug in your life?

Photo by absentmindedprof

September 23, 2011

What's the Drug in Your Life? Part I

I used to play computer games, a lot, mostly of the build-a-civilization-up-from-scratch variety–Civilization, Age of Empires, that kind of thing. I'd be annoyed when people interrupted me, even for important obligations. I might have to answer the door, go back to the computer grumbling afterwards, and then two hours later the phone would ring, and I would think "Again? Can't I have a moment's peace?"

Addiction to behaviors

You may have noticed how similar that behavior sounds to drug addiction–and the similarity isn't just metaphorical. It turns out that the brain chemistry of addiction to drugs is very much like the brain chemistry of addiction to food, sex, shopping, television, computer games, and much else: the neurotransmitter dopamine activates receptors in our brains when we do the thing we're addicted to, giving us a jolt of pleasure. There's nothing wrong with that: the same process happens whenever we feel pleasure in anything. With addiction, though, we keep repeating the activity that gave us pleasure over and over, and this causes us to be less responsive to dopamine, which creates two problems: first, we have to do more of the addictive thing to get any pleasure out of it, and second, pleasure in other things we're not addicted to is dampened. This can keep going and going, resulting in a situation where we take every possible opportunity to do the addictive behavior and give up on everything else in our lives.

Of course, some drugs have other chemical effects on our brains that can make addiction even worse. For instance, withdrawal from shopping can be difficult, but it doesn't usually doesn't involve vomiting, fever, and an inability to sleep like heroin withdrawal.

Also of course, not all shopping, eating, sex, television watching, and computer gaming is addictive behavior. The next section helps explain what addiction to a behavior looks like.

What addictive behavior does

Addictive behaviors may not start because the behavior itself is especially pleasureable. As cleverly-designed as games like Civilization are, they're not necessarily a rollercoaster of pleasure so much as some pleasure interspersed with long periods of obsessively reacting to prompts. Like sex, shopping, eating, and television, computer gaming is something that we can lose ourselves in: almost all of our attention and awareness is caught up in improving food production in our capital city, or in comparing the stitching on one jacket compared to another, or in being passively entertained by a literally nonstop parade of television shows.

This can be a key insight for some of us: addictive behavior may not be so much about wanting the thing we're doing too much of as about shutting out something we don't want to face. Failure, feeling unsafe, conflict, lack of love in our lives, unfulfilling jobs–these things and many more can cause us to turn away from life and lose ourselves in running up credit cards or systematically munching through a large bag of Doritoes or playing World of Warcraft straight through the night.

Unfortunately, distracting ourselves from our problems rarely does anything to make them better, and the addiction tends to create problems of its own, damaging relationships, threatening physical and financial well-being, and otherwise pushing out things we'd need to do to make our lives better in favor of more and more of the addiction.

The second article in this series will appear Monday, and will talk about ways to overcome addictive behaviors.

Photo by DJOtaku

Quinn Reid's Blog

- Quinn Reid's profile

- 6 followers