Quinn Reid's Blog, page 21

November 15, 2011

How Do You Fix Greed, Part III: Why Should I Sacrifice Myself?

In a recent comment to my post "How Do You Fix Greed? Part II: American Society Is Built for Greed," someone asked

Why should l sacrifice my self to others? Read Ayn Rand, and you will know where greed comes from.

I was surprised by the question, because the answer seemed obvious to me, but the more I thought about the response, the more grateful I am for the comment, because it's a fair question: even if greed is bad for society, which is something I've been asserting in recent posts, from a certain perspective there's the following pressing question: So what? If I can get everything I want, why should it matter to me if other people are unhappy about that, or if it interferes with things society or culture expects from me?

For the asker's interest, I've read Ayn Rand, and I'm familiar with a lot of arguments for greed. If you're looking at the question on a strictly personal level, it comes down to this: people who let themselves fall prey to their own greed are assuming that getting more will bring them more pleasure, and that pleasure and happiness are the same thing. The truth–and there's good science backing this up–is that having more stuff does not necessarily bring more pleasure, and that even if it did (which it doesn't, remember), that pleasure doesn't by itself amount to happiness.

I'm not going to go into detail about all the research here, to prevent this post from becoming unmanageably long, but before I continue I'll link to other articles on this site, several of which reference the studies that provide the raw information for the connections between human relationships, happiness, and pleasure that I'm about to describe.

The Difference Between Pleasure and Happiness

If It's Not Fun, Why Do It? A Few Pointed Answers

Why Happiness Is Key

How Other People's Happiness Affects Our Own

Want to Reduce Stress? Increase Social Time

The Best 40 Percent of Happiness (this one covers lottery winners)

The High Cost of Not Liking Your Job

Why doesn't "more" bring more pleasure?

Getting more things does not necessarily lead to more pleasure, although it's true that some things, in some situations, can add to pleasure and even happiness. Unfortunately for our pleasure levels, though, the more we get, the less any given part of it matters. If you go to a restaurant and eat the most delicious meal in the world, the first time you eat it, you may be in ecstasy. If you eat it again the next day, due something psychologists call "hedonic adaptation," it simply won't be as good. It's similar to the process a drug addict may go through, whether that drug is caffeine or crack or something in between. The first hit has an enormous effect, but subsequent experiences produce less and less dopamine, the neurochemical that makes us feel pleasure. In other words, the more I have, the less pleasure I get from each thing.

Additionally, having more power, money, resources, or things also means I have more concerns, because I need to defend myself from people who want to usurp my power, siphon off my money, use my resources, or take my things. As I get more and more, what I have pleases me less and adds more to my stress load. We often envy celebrities, people with political power, and others who have "more," yet the rates of scandal, failed marriage, substance abuse, and other indicators of severe unhappiness seem to be exceptionally high among these kinds of people. Some of it is surely the pressure of being in the public eye all of the time, but regardless, it lends support to the point that having more is not necessarily pleasurable. Ask the many people who've won the lottery and later committed suicide–oh wait, you can't: they're dead.

Isn't "happiness" just another word for "pleasure"?

Even the pleasure that we can get from having more doesn't amount to happiness. Happiness, according to research, has a lot to do with having enough and not much to do with having extra. It also has a lot to do with how we think and feel about ourselves and about our relationships with other people. If I feel like a good person, am proud of my accomplishments and integrity, enjoy the company of people close to me, experience trust and connection with others, and otherwise make the most of myself and my relationships, I'm far, far more likely to be happy than if I have piles of stuff, people whose interest in me might be mainly about my having piles of stuff, and things I don't need that I have to defend from people who either don't have enough stuff or are as greedy as I am.

Greed at its heart is a misunderstanding, at attempt to substitute money, power, or stuff for the things that really make us happy (see the first article in this series, "How Do You Fix Greed? Part I: The Roots of Greed"). The altruistic and kind behavior that seems like sacrificing ourselves, when done in a healthy and proportionate way, surprisingly turns out to get us the most individual happiness of anything we could possibly do. Greed is an easy path to falling short of the happiness we could otherwise achieve.

Photo by CaptPiper

November 10, 2011

Sandra Tayler on Some Persistent Advantages of Plain Old Paper Books

Sandra Tayler, a friend from Codex, recently posted her reasons for sticking to a large extent with paper books over eBooks. While she has a much different take than I do on the issue, she makes some very meaningful points, and I especially like her ideas about children's books, which she makes better use of than many of us parents. You can read her thoughts on the matter at http://www.onecobble.com/2011/11/05/kindle-update-why-i-still-buy-paper-books/.

Sandra Tayler, a friend from Codex, recently posted her reasons for sticking to a large extent with paper books over eBooks. While she has a much different take than I do on the issue, she makes some very meaningful points, and I especially like her ideas about children's books, which she makes better use of than many of us parents. You can read her thoughts on the matter at http://www.onecobble.com/2011/11/05/kindle-update-why-i-still-buy-paper-books/.

Photo by altopower

November 9, 2011

Would Scrivener Make You a Happier Writer?

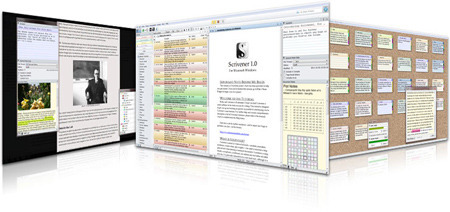

The process of writing has changed enormously in the past 50 years. Word processors transformed writing from something you have to redo every time you want to make changes to something that can include any number of changes with no extra effort beyond the edits themselves. The Web has elevated research from a limited, time-consuming, and sometimes expensive process into a few minutes communing with Google. Laptops and similar devices have taken these improvements out on the road. Print on demand and especially eBooks have opened an entirely separate career path for some independent writers.

In comparison to these game-changing tools and resources, what difference does Scrivener make? Well, if you're like about 80% of writers, the answer used to be "none at all," because Scrivener was originally a Mac-only program. Unless you've been beta testing the Windows version, all that changed yesterday when Scrivener 1.0 for Windows was introduced.

What's so great about Scrivener?

I originally posted about Scrivener in an article called "How Tools and Environment Make Work Into Play, Part I: The Example of Scrivener." My main point in that article was that for long or complex writing projects–novels, screenplays, stage plays, non-fiction books, articles with lots of information, or even short stories with especially detailed worlds or plots–Scrivener takes the heavy lifting out of organizing a lot of thoughts, resources, research, ideas, plot points, facts, scenes, or other details into a living outline that naturally evolves into your actual book.

For example, when I wrote my short book The Writing Engine: A Practical Guide to Writing Motivation (available in PDF form for free on this site, or for 99 cents on Amazon for the Kindle), I had an enormous number of tips, tricks, insights gleaned from scientific research, anecdotes, and whole articles to organize into a well-structured book. Using Scrivener, I dumped everything in without worrying about the order and then was easily able to organize it all into a structure that I could write and rewrite my way through until I had a clean final draft. While organizing, I was able to focus on just a few elements at a time, which took away that crazy, overwhelmed feeling of worrying that I'd forget some important piece of information. Once I began my actual writing, it also allowed me to focus singlemindedly on what I was writing.

How does Scrivener work?

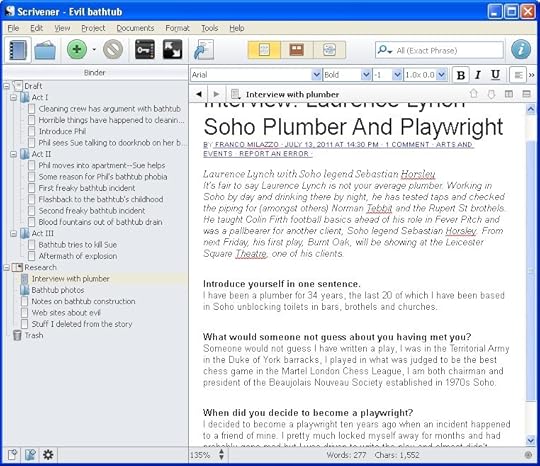

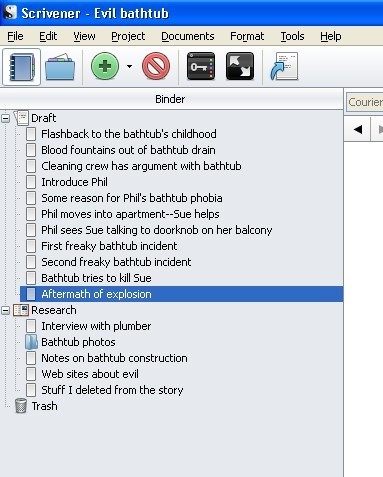

The basic idea behind Scrivener is very simple: it conceives of a piece of writing as a bunch of pieces of text, each of which might be a paragraph, a scene, a chapter, an illustration, some research material, notes for your reference, etc. These pieces are organized into two general categories: Draft (for the writing itself) and Research (for supporting material that's not intended to wind up in the actual book).

All of these pieces can be organized into an outline. For instance, I might start with these ideas for an evil bathtub story:

Note that in this picture I'm just showing the "binder," the section on the left where I come up with the pieces I want to organize. I typed the names of my pieces right into there. I also could have started with some material I'd already written, which would go into the text area on the right that appears as I click on each item.

As you can see, I'm starting with some ideas about characters, a few plot points, some incidents, and some research. I'm not sure what happens when yet: all I have is glimpses of what's happening in a short story about an evil bathtub.

(It's ironic to me that I had forgotten, in putting together this example, that in college I actually wrote a story in college about a cursed bathtub. I guess this is a thing with me. I think the title was "Miriam Pzicsky and the Handyman from Hell." I'm pleased to say that I have improved as a writer somewhat since college.)

In the next picture, you'll see what I did with those pieces of information: I chose to impose three-act structure (something I don't have to do and generally don't do explicitly) and then dragged the items around into something resembling an order for the story. One of the great things about Scrivener is that in doing this, I automatically begin to see where there are holes in the story, where it might get repetitive, and what kind of structure I'm dealing with. Just seeing the story as an outline helps me improve the story.

click to enlarge

Once I'm done adding or changing elements in my outline, I'll just start clicking on items in it and writing those items one by one. I can add, delete, and move around pieces as I write (which is why I refer to this as a "living outline"), and the click-and-write experience makes it easy to focus on one part of the piece at a time.

Scrivener has many, many more useful features. This glimpse is only meant to show what I think is the key useful concept behind the program. Fortunately, it's more than a concept: the software has been developed with a lot of appropriate, productive, and easy-to-use features.

While Scrivener is useful, it's also fun, at least for me. When I use Scrivener, I use less of my attention to keep track of details and more of it to write. This makes me a happier writer.

When is Scrivener not useful?

Scrivener isn't for everyone. If you like to start writing a piece from the beginning and then go right through to the end, or if you tend to make a traditional outline just to get a grip on what you're doing and then don't do much with that outline except consult it as you write, I'm not sure Scrivener would be especially helpful for you. If you write off the cuff, without research or planning, there won't be much Scrivener can help you organize. Personally, I love Scrivener's organizational features, but I rarely use it for short stories: I find it much more useful for outlined novels and non-fiction projects.

Even if you write by the seat of your pants, though, you may find Scrivener invaluable. You can start writing a novel by typing "Chapter 1″ and plunging ahead with only the most general sense of where you're going, but even in that kind of situation you will probably start coming up with scenes you want to include later, plot developments that need to occur, bits to insert into what you've already written, research materials, and more things to be organized. Scrivener doesn't care whether you organize before, during, or after writing: it just helps you get everything into a usable structure.

If I've piqued your interest

The fine folks at Literature and Latte offer a free, 30-day trial which is in fact far better than most 30-day trials in that it doesn't count calendar days, but instead days you use Scrivener. If you use it twice a week, your 30-day trial will last you 15 weeks. You also don't have to create an account, sign up for anything, or even supply an e-mail address to get the trial. You can download it here: http://www.literatureandlatte.com/scrivener.php .

If you do opt to buy, the price is $40, but there's a 20% discount you can find at http://www.literatureandlatte.com/nanowrimo.php . A 50% discount is available for people who "win" NaNoWriMo, completing at least 50,000 words of a novel project in the month of November. (For more info on NaNoWriMo, go to http://www.nanowrimo.org/ .)

November 8, 2011

Amazon Starts Free Kindle Lending Library

This came as a surprise: today Amazon announced they are starting a free lending library for Kindle owners who have an Amazon Prime membership. Amazon Prime has to be one of the most unlikely bargains out there. Who thought of putting streaming movies, free shipping, and temporary eBook access together in one package (for $79 a year)? Counterintuitive or not, it's an attractive option if you order a lot of things on the Web.

Even if you do already own a Kindle and have Amazon Prime, don't plan on suddenly being able to read whatever you want for free. Amazon is only offering a limited number of books under the program, with a maximum of one loan per month per Prime member. With that said, though, there's an impressive array of books available–more than 5,000 of them, including some current bestsellers.

I continue to worry about the fate of libraries as eReading spreads and the eBook world becomes more flexible and friendly to readers. Post your comments, links to articles elsewhere on the Web, or links to your own blogging on the subject below.

November 7, 2011

Marie Curie's Losses and Triumphs

Today is the 144th anniversary of the birthday of Marie Skłodowska-Curie, a woman who won two Nobel prizes in different disciplines: Physics (in 1903, with her husband Pierre and a third scientist) and Chemistry (in 1911, by herself). In and among many other accomplishments–for her family and for her native Poland, for example–she managed to simultaneously drive the dawning of a greater level of respect for women in general and to make paradigm-changing discoveries in science.

Today is the 144th anniversary of the birthday of Marie Skłodowska-Curie, a woman who won two Nobel prizes in different disciplines: Physics (in 1903, with her husband Pierre and a third scientist) and Chemistry (in 1911, by herself). In and among many other accomplishments–for her family and for her native Poland, for example–she managed to simultaneously drive the dawning of a greater level of respect for women in general and to make paradigm-changing discoveries in science.

I would like to be able to comment on what drove Skłodowska-Curie, but without a lot more research, my comments would be too little observation and too much speculation. What I do know is that she seemed driven to better her understanding of science and to accomplish much else of value from an early age. Based on research on both intelligence and temperament, it seems likely she maximized some benefits she was born with in both areas: a sharp mind and emotional resilience.

I mention resilience because Skłodowska-Curie didn't have an easy time of it in childhood. She did benefit from a highly educated and supportive family, but it was a family that suffered a series of painful losses as Marie was growing up: her eldest sister, Zofia, died of typhus when Marie was ten, and her mother died of tuberculosis when Marie was twelve.

Both sides of her family had been wealthy, but both had worked for Polish independence from the Russian empire and had been stripped of their wealth, so getting a decent university education was a significant struggle for Marie. While as a young woman, she worked as a governess to earn money to be able to attend university and to support her sister doing so in Paris. At this point she fell in love with a young and brilliant mathematician, but his family rejected her because of her poverty.

We all react differently to loss and adversity, whether it is our country being dominated by a tyrannical neighboring empire, the death of friends and families, being kept from the ones we love, or being frustrated in our attempts to accomplish our goals in life. It's easy sometimes to retreat into self-pity, complaining, giving up, becoming hard and cynical, compromising our visions of what our lives could be, taking the next easy situation that comes along even if it's wrong for us … but Marie did none of these, which makes her birthday more than a historical note: it can, if we like, become a day on which we're inspired to let our setbacks, disappointments, and losses fuel our commitment to doing great things in the world.

If you enjoyed this post, you might be interested in reading "Do You Have Enough Talent to Become Great At It?" and "Randall Munroe and Zombie Marie Curie on Greatness."

November 4, 2011

Body Language for Actors Part 1: Common Mistakes

There are valuable lessons for actors in one of my favorite areas of behavior study, body language. From moment to moment we communicate far more to each other than our words would suggest, and learning to read body language opens up new channels of communication to understand much better when people are feeling annoyed, confident, defensive, or flirtatious, how serious they are about what they're saying, what they intend, what they want, and how they're reacting to you.

How good are actors at body language? As you can probably guess, there's quite a range. My sense is that what works best as a rule is method acting, in which the actor is conjuring up the same emotions the character is feeling, usually (as I understand it) by connecting with events and memories from the actor's own life. For instance, if I were playing the part of an athlete who had just lost an important game, I might conjure up my recollection of losing in the finals of the school spelling bee in 4th grade by misspelling "chief" (I had trouble with "i before e" for quite a while, partly because of my last name). Method acting appears to work in part because some of the body language the character would be showing comes out as a natural expression of the actor's emotions. Regardless, a better awareness of body language can help create stronger performances.

In articles in this series we'll look at mood, confidence, attitude, courting gestures, truth and lies, attention, and more. The goal is to allow readers to harness some of these gestures consciously or semi-consciously to act more convincingly. I hope to follow up with video versions of some of these posts to demonstrate what I mean.

Of course, this knowledge is useful for a lot more than acting and public speaking. Surprisingly, just mimicking a gesture or position that tends to go with a certain emotion can help evoke that emotion itself (see "Using Body Language to Change Our Moods").

Limitations of body language

Body language is not a simple one-for-one system of communication: when interpreting body language, it's important to take in the whole sense of what's going on and not fixate on one particular gesture. For example, if I say something and then scratch my nose, it might mean I'm a dirty rotten liar–or it might mean that I'm recovering from a mild sunburn.

With that caution, let's start this series by looking at some common body language mistakes–or if that's too cut-and-dried a term, perhaps we can call them "infelicities"–seen in both beginning and experienced actors. We'll look at most of these in more detail in later articles, but the point of this piece is to point out a few specific things to avoid.

"I don't really mean it"

Here's one that appears regularly even in major studio films, most often when someone's professing their love for someone else: the head shake. The actor says "Darling, I love you more than life itself," and all the time he's shaking his head slowly as though overcome with the passion of it all. He's not overcome with the passion of it all, though: he's probably worrying a little about how his real life wife is feeling about the scene, or thinking about how little he likes the actress who's playing his love interest. To borrow language from another sphere, "No means no."

People do shake their heads for emphasis when they're saying something negative, though. For instance, if someone says "I won't leave you" or "That's not what happened," a head shake just reinforces the point.

"Gosh, I'm nervous!"

Of course being on stage can be nerve-wracking. Unfortunately, if the nervousness comes through in a character who is meant to be confident, focused, or relaxed, the character becomes hard to believe. Watch out for repetitive motions, tapping, fidgeting, clasping hands together, holding something in front of you (like a pencil or a hat) to connect your hands, or holding your arm or leg (a reassurance gesture). Of course, the best way to stop being nervous is to be so submerged in the character that you're feeling the character's emotions instead of your own.

"Say that to my face"

Personal space is something that actors seem to get better at with experience, so issues with it are especially common in, for instance, school productions. We all have a zone of personal space around us, and generally speaking, people don't enter that space unless their interests are either romantic or aggressive. This is one reason that doctors and dentists (for example) can be so unnerving: to do their jobs, they have to violate personal space in a big way.

If someone's being loud and aggressive from across the room, or if a character is trying to seduce another character but is sitting at the other end of the couch, it's hard to take the intention seriously: seduction is much more convincing within a few inches of the body, and we can see a fight coming if Mary gets just a foot away from Ellen's face and Ellen doesn't back down.

"I want you! But not really"

Love and attraction are hard to convey even when the personal space issue is managed well. People who are interested in others use a complex combination of courting gestures that vary based on a person's personality, level of interest, gender, sexuality, status, and other measures. What's least convincing, though, is an attempted seduction where there are no courting gestures. If a straight woman sits down and entwines her legs or brushes her hair from her face, we start getting the signal that there's interest there even if no words have been spoken. Gaze also plays a part, as someone experiencing attraction might glance briefly–or stare openly–at the objects of their of affection. People who are trying to convey romantic interest find excuses to touch each other, face their bodies toward one another, and show off their prize physical traits (for instance, by a woman putting her fingers together and resting her chin on them, a gesture called "the platter," to show off her face). We'll touch on these points more in the article on courting gestures, and you can read about them in some detail in "How to Tell If Someone's Interested in You, and Other Powers of Body Language".

Photo by slava.toth

November 3, 2011

How Do You Fix Greed? Part II: American Society Is Built for Greed

[image error]

Recently I posted about the emotional roots of greed–that is, some reasons we sometimes act or think greedily. Today I want to pick up where I left off and talk about how we've gotten ourselves in trouble with greed as a society and what we'd need to do to if we want to root it out.

It would be great if greed were a simple problem, but it appears that it has at least five different parts.

We already talked about where greed comes from individually, the emotional component in Part I of this series.

We have a culture where greed is not only OK, but encouraged.

The effects of how we use money are hidden.

Most of the organizations that handle money in our society are set up to maximize profit.

Laws and regulations about taxation, corporations, and commerce in some cases make greed the law.

Our Greedy Culture

Rich people in our culture tend to be admired, and poor people tend to be looked down on. We tend to think of wealth and success as being closely related, and the role models we see in the media are usually people with a lot of money. This isn't unique to Americans or particularly shocking, but it is harmful. If we can gradually focus more on people's accomplishments, integrity, regard for other people, happiness, and personal fulfillment instead of their cars, houses, financial resources, and lifestyle, we'll move toward justice and compassion as a society and away from celebrity worship and the quest to Have More Stuff.

But it's hard to change who we envy. If offered the choice between becoming as a balanced and compassionate as the Dalai Lama or as rich as Bill Gates, which would you choose? I'd have a really difficult time with that challenge, I have to admit. When I think of having huge financial resources, I imagine how many of the things in my life that currently take a lot of effort would be much easier, how much good I could do, what great things I could get for my family, and so on. I don't necessarily think about the complications that come with money or the disparity between the wealth I'd have and the poverty a lot of people live through day after day. I also have a lot of trouble weighing the benefits of being as happy and at peace as the Dalai Lama appears to be against the seemingly more obvious benefits of having tons of cash. Even those of us who work hard at staying out of the consumerist mindset can get hung up on this problem–but that's exactly the kind of conscious change that will help us transform our culture's attitudes toward greed.

Hidden impacts of our money decisions

We rarely see the help or harm that comes from our investing or spending. It's very hard to know exactly who gets our money or what they do with it when we buy something or make an investment. It's possible be an ardent anti-tobacco activist and to unknowingly have a retirement account that invests heavily in the tobacco industry, for instance. We may buy a product and not know how much of the money we spent goes to people who worked to get us the thing in the first place, how much to investors, and how much to parasites (like corrupt government officials in the country where the thing was made or speculators). It's even harder to get a clear idea of our money's impact on things like the environment or the availability of good jobs.

Even when we do know something about the impact of our money–for instance, buying a cheap electronic item made in China at a local Walmart, which is likely to be supporting underpaid labor both in the factory where the item is made and at the Walmart where it's sort–we often don't act on it, probably in part because we can't be sure we're right. Maybe those Chinese workers are really getting paid a living wage. Or even if they aren't, maybe the money they are getting paid is better than what would happen to them if that job moved to a country where people get paid fairly for their work.

By not knowing the real effects our financial choices have in the rest of the world, we're cut off from making better choices. Ideally, whenever I wanted to buy or sell or rent or borrow or lend or invest, I could get a little scorecard that showed me how much good or ill my choice was making all the way down the line to people, places, and organizations. In practice, that's probably next to impossible (though in a few decades we might have enough information available electronically that something like that would be possible). However, we can educate ourselves about where the things we buy come from, where our investments go, and all the rest. We might not know the exact details of every purchase we make, but any insight empowers us to make decisions with our money that otherwise would be made for us by somebody else.

Designed for profit

Usually, companies are set up by investors or entrepreneurs who are trying to make a bunch of money. While they might have other priorities, money usually comes first. The penniless immigrant chef who starts with a sandwich cart that grows over time to a restaurant and then a chain of restaurants is probably cooking at least in part out of a love of cooking, a desire to do work that's valued, and all the rest, but … well, I was about to say "the bottom line is still profit," but that's what "the bottom line" means. The need for profit has come to be central even in how we talk about what's important. We can even things like "The bottom line is that a lot of people don't have adequate healthcare coverage" without realizing we're being ironic.

What's the alternative? Different kinds of organizations: fewer entrepreneurial start-ups and money-worshipping corporations and more non-profits and cooperatives. I'll grant you, this doesn't solve everything itself. For example, the health insurance I had up until a year or two ago was run by a not-for-profit, and yet it was terrible. Still, organizations like my local food co-op and the credit union where I bank show that these kinds of organizations can be reliable and successful without anyone trying to turn them into little money factories.

Greed is the law

Like a lot of things that have become part of our culture, greed has naturally made its way into our laws as well. Probably the biggest example of this kind of legislation is that for-profit corporations are legally required in many situations to maximize short-term shareholder profits, and corporations are also treated as individuals with legal rights of their own, just like a person.

Laws won't change much until the culture does, but laws that make profit sacred get in the way of cultural change away from greed. There are only two ways I know of to get out of a bind like this: one of them is to make improvements wherever possible and gradually drag the legal system along with the priorities of the people it governs. The other is for there to be a huge catastrophe that ruins everything we've built so that we have to go back and start over.

I favor the first approach.

In the next post in this series, I'll talk about ways we can take greed out of businesses.

Photo by Michael Aston

October 27, 2011

How Do You Fix Greed? Part I: The Roots of Greed

How do you fix greed? It's a question that's plagues our country and much of the world right now, although I'm going to talk about America specifically–because let's face it, where greed is concerned, we Americans are at the top of the charts. In some other countries, corruption and greed in the government is an especially nasty problem, but here in America greed is more or less a core value, something that's encouraged for every citizen. As a result, we're the wealthiest large nation in the world and consume a percentage of the world's resources that's far out of proportion to our population.

What specifically is so bad about greed? Isn't it natural, anyway? Even if it isn't, what can you do if greed is just something bad people embrace?

What's wrong with greed?

The problem with greed is that it leads to people and corporations trying to amass resources they don't need and can't use well, often straining the capacity of the rest of society and the natural environment in the process. It's not just the multi-millionaire tossing back caviar while homeless families try to survive on canned soup: it's kids amassing electronic devices instead of going outside and playing with friends, adults trapping themselves in jobs that make them miserable in order to get the larger houses and better cars they think they "should" be able to have, and people whose lives are dominated by abject envy of everyone wealthier or more famous than they are. Greed is bad investments, celebrity idolization, consumerism grown out of proportion, lousy jobs, waste, inequity, and disconnection of us all from one another.

Isn't greed natural?

We've grown to think it's natural and normal for people to want as much money as they can get, but we don't really want money at all: what we want is what money gets us, and by this I don't mean the products and services, but rather things like a sense of safety, power, indulgence, or validation. When we talk of caring about something, we're saying we have an emotional stake in it. Our emotional stake in money doesn't have anything to do directly with having the assets: it's first about answering physical needs—the minimum of food, shelter, health care, safety, clothing, transportation, and education that is the baseline for our society–and second about gratifying unmet emotional needs.

The emotional roots of greed: some examples

Let's say Ed grows up in a house where his parents only pay attention to him when he accomplishes something–gets good grades or wins a trophy in a track meet, for example. Ed may very well internalize the idea that the only way people will care about him–in fact, the only way he's actually worth anything–is if he has something to show for it that everyone can appreciate. He may therefore go into a high-income career and spend his money on trophies: trophy house, trophy clothes, trophy vacations, trophy foods … all so that he can impress people into caring about him and so that he can feel worthwhile. This may sound a little pathetic, but consider how many people buy things–cars, houses in the right neighborhood, even certain foods–in order to act out the life they want to be seen leading.

Actual human connection could make all of this trophy-getting unnecessary. If Ed acquires a set of friends who appreciate his sense of humor and determination and don't care about his money, Ed may come to stop caring about money so much too, which could lead to enormous changes in making his life happier–like living where he really wants to live, doing what he really wants to do, and prioritizing experiences with friends and family or meaningful accomplishments in the world over acquiring things.

Ed's situation isn't the only way we get emotionally involved with money. Imagine Deborah, whose childhood was one disaster after another resulting in moves, loss of friends and homes, and other kinds of upsets. Once Deborah gets out into the world on her own, she may prioritize security over all else, meaning that she has to pile up a lot of things and a lot of money so that she will feel safe against things like the layoffs her father went through or the loss of her home to a flood because her parents couldn't afford flood insurance.

Or imagine Nick, who was awkward and shy as a kid and ended up being the butt of everyone else's jokes. They won't be laughing at him when he pulls up to the high school reunion in a Ferrari while wearing a twenty-six hundred dollar suit, now will they?

Or Andrea, whose parents gave her all the physical things she wanted but left her actual care to a string of nannies and boarding schools. As an adult, Andrea buys anything she wants, whether she can afford it or not, because she "deserves" it–constantly trying to fill an emotional void with things, and probably failing just as badly as her parents did no matter how delightful that first, brief glow of pleasure may be.

That's not nearly the whole list, but I hope my point is clear: the roots of greed are emotional ones. People want to feel safe, loved, valued, validated, and respected. In different ways, money promises all of those things, even though it often doesn't deliver.

Are greedy people bad people?

It's tempting to write off anyone who acts greedy as simply a bad person, yet there's a more exact and constructive way to look at the problem. First, problem behaviors like greed usually come from people trying to meet their emotional needs, which is a pretty understandable thing to try to do, even if somebody hasn't chosen a very successful method.

Almost all people who act greedy also do things that we would admire in their lives–they might parent their children well, give to charities, have a strong work ethic, work for causes, help friends and neighbors, have a lot of integrity, or otherwise show their true value.

Writing these people off also means writing off whatever part of ourselves might agree with them, the part that may covet clothes or free time, travel, cars, expensive foods, luxury, or even having a lot of money to help other people with.

Writing off anyone who acts greedy is wasteful, too, because if people can learn not to be greedy, as surely seems to be the case even without the fictional or legendary examples of Siddhartha and Ebeneezer Scrooge, then there's a powerful reason to try to find ways to fix greed: if a greedy person becomes a non-greedy person, we've gained an ally–sometimes a powerful one.

In the next part of this series, I'll take a look at how greed is entrenched in American culture and what would be necessary to root it out.

Photo by subsetsum

October 25, 2011

What Will Amazon's New Kindle Format Mean for Writers (and Readers)?

A few days ago, Amazon announced their new Kindle 8 format, the format the Kindle Fire will use to show newer Amazon books. I've heard some questions arise about this–whether Kindle authors will have to re-convert books, whether the older Kindle devices will support the new format and what will happen if they don't, etc. Fortunately, digging into Amazon's information the new format answers these questions clearly. Here are the implications for Kindle authors and some answers for readers who use the Kindle.

You won't have to convert your existing Kindle books

The Kindle Fire and other devices and apps that support the Kindle 8 format will continue to support older Kindle formats. If you have existing books available for Kindle, the only disadvantage they'll have if you don't do a Kindle 8 version is not taking advantage of the new Kindle 8 features, which most non-graphic-intensive books won't have a use for. If you have complex layouts, lots of graphics, etc., you probably will want to come out with a new, improved version.

Apps and new Kindle devices will support Kindle 8; old Kindle devices won't

The newest generation of Kindles–the Kindle Fire, the touchscreen Kindles, and the latest keyboard Kindle–will soon support the new format. So will Kindle reader apps for iPhone, Windows, the Web, etc. Older Kindles won't.

Older Kindles downloading newer books will just get a Kindle 7 version

Amazon is rolling out new software for formatting and previewing Kindle books, KindleGen 2 and Kindle Previewer 2. This software will automatically generate both an older Kindle 7 version of the book and a newer Kindle 8 version. If you're reading on a device or app that supports the Kindle 8 format, you'll get that, including any enhanced content that may be included. If you're reading on an older Kindle–that is, any Kindle device bought previous to the launch of the Kindle Fire generation–you'll get the older format. Kindle Previewer 2 allows viewing how the book will look on various devices, so you'll have ample opportunity to test and tweak the appearance of your book. The only real drawback to using an older Kindle device is that there will be some content in graphics-intensive eBooks that won't translate well to the older, more limited format.

Newer Kindle devices and apps will support the old format

Just to be clear, nothing has to change about existing Kindle books for the newer devices to read them: Kindle 7 is just another format they support.

The new format will no longer be straight Mobi

Prior to Kindle 8, the only difference between Amazon's Kindle format and the industry standard Mobi format was Amazon's DRM, "digital rights management" encoding that helped prevent unauthorized copying of Amazon books. For books that don't have DRM, the current Kindle 7 format is identical to Mobi, and in fact you can take a non-DRM-protected Kindle book off a Kindle, change the extension (the last part of the file name) from .azw to .mobi, and read it on any Mobi-compatible device. With Kindle 8, it appears this will end. Amazon appears to have decided that with the direction eBooks are going, Mobi alone is too restrictive. They do seem to be using other industry standard specifications, though, including HTML 5 (the newest, most dynamic, and most design-friendly format for Web pages, which is now supported by current browsers) and CSS (a way to specify text formatting and page layout that is also supported by current browsers).

Kindle 8 format books can have a lot more design to them

In Kindle 8 format, Kindle books can have colors, fonts, and complex layouts. Frankly, I'm not very enthusiastic about this for most books. For books where text and images need to be intermingled in a particular way or that require tables or vector graphics, it will be great. For the vast majority of books, it will be completely unnecessary, and unfortunately some of these books will be designed in a way that will make them harder to read. Oh well. Just please don't be one of the people who takes a book that is just text and tries to pretty it up with special fonts and color. From my point of view, when I read, I want to be barely aware of the text so that I can focus on what's being said. I'm willing to bet most readers have the same basic response to overfancified text.

Kindle 8 won't support audio and video

Amazon's information isn't clear about this, but at least according to this gentleman, audio and video will not be included in this version of the Kindle format. This surprises me, actually. It seems almost a no-brainer that the Kindle Fire should be able to read books with embedded audio and video–for instance, language courses that will pronounce words when you tap on them, or a book about the history of film with pertinent clips–not that any of that would work on my 3rd generation Kindle anyway. Oh well. Maybe in Kindle 9.

October 20, 2011

Should Writers Have Blogs?

Writers of the Future winner and successful science fiction short story author (Analog, Intergalactic Medicine Show, etc.) Brad Torgersen recently brought up a useful question in a writers' group: what use is a blog to a writer of fiction? Even if you manage to attract a lot of readers, are they people who are likely to be interested in your stories or novels? Is the payoff worth the effort? My response from my experience with the two blogs (ReidWrite and The Willpower Engine) that I merged together into LucReid.com some time back turned out to be fairly long and potentially of interest to some readers, so here, with a little cleanup, is that response.

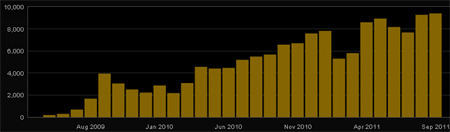

An experiment in blog as marketing

Several years back I began two blogs, one for writers and the other on the psychology of habits. I started the writing blog because I often found I had things to say about writing that I was drawing from my experiences and from discussions with a large number of other new and successful writers. The psychology of habits blog was designed to build up a reputation and readership for me on the subject: in publishing-speak, to establish my platform. I was writing a book on the subject of psychological finds about self-motivation and had concluded that I wouldn't be able to sell it without a good platform, which is really the case for most nonfiction books these days. If you don't have credentials or a lot of people who associate you with the topic–and preferably both–then you're probably out of luck.

For quite some time I worked on the psychology of habits blog, posting first three times a week on a regular schedule, then every weekday. I worked up a brand, promoted it around the Web, commented on other people's sites, and in general did everything I read I was supposed to in order to build my readership. Over the course of a year, my blog grew (slowly) to the level of readership I thought was minimal for helping me sell the book I'd been working on, so after that year was up, I started contacting agents about the book.

Nobody was interested.

The main reason I couldn't sell the book seemed to be that I had no credentials–no advanced degree in psychology, especially–and that a blog with a thousand reads a week (this was about 18 months ago) wasn't substantial enough for anyone in publishing to really care.

So despite a load of work, the blog-as-marketing approach ultimately failed for me. Still, I continued the blog. The topic has never failed to keep me interested.

Is your blog a pleasure or an obligation?

Posting regularly felt like a huge obligation and time drain, even when I cut back down to three posts a week. It was only when I decided to combine my two blogs, to rebrand the site to just use my name, and to post only when I had something I really wanted to share that things changed and it stopped feeling oppressive.

I now blog when I have something to say, although I do prod myself if it's been a week and I haven't posted anything. The blog does a lot of good in helping me structure research and integration of new ideas, and from the occasional communications I get it's sometimes meaningfully helpful in other people's lives. However, though it's continued to grow in readership, it has never become a base for community: it's more of an information outlet. It's a good place to find out how to get motivated quickly, how to figure out if someone's romantically interested in you, or how to stop feeling hungry, but I talk very little about my personal life or even about my adventures in writing, and try to stick to facts or extrapolate from facts, tending to qualify my statements (like this one), so I'm neither very personally engaging nor very inflammatory. It shows up in my comment counts: more often than not, I don't get any, and yet a goodly number of people are reading what I'm putting out. I'm informative, but I'm not building community here.

By contrast, I've been extremely successful building a community of talented, improvement-oriented writers at Codexwriters.com, but rather than trying to do that based on the impact of my personality, I've done it by pulling together groups of writers who are dedicated to their craft and want to share ideas with and learn from other writers who are similarly dedicated. All you have to do to throw a good party is to get great people to come.

Who should have a blog?

My belief about blogs is that they should generally be expressions of things that the blogger really wants to share. Sure, there may be a cost-benefit calculation to determine whether or not to spend time on a particular post or on having a blog at all, but I'm not enthusiastic or optimistic about blogs that are put up primarily as marketing vehicles. I don't think there's anything wrong with that ethically; it's just it's a lot of work to plow into something that's unlikely to pay off proportionately.

I agree too with those who say that the golden age of blog-starting is over. With the literally millions of blogs out there, there's too much noise to really stand out in the vast majority of cases. Like writing fiction in the first place, there's not much point in doing it unless it's something you love doing for its own sake.

On Facebook, Twitter, and the rest of the social computing world

For the record, I don't think that social computing is an effective marketing strategy either. I see people rushing to socially compute with people who are already successful: they'll seek out Twitter feeds and Facebook pages of authors they already like, while lesser-known writers who are scrambling for attention may get a lot of personal contacts, but won't be building their readership. I admit, though, that I'm working from personal experience and impressions of other people's experiences, not from any carefully-gathered body of information. It's possible that using social networking as an author can be a great marketing strategy for some people: I've just never seen (or heard of) it working.

As for blogs, I think the bottom line is that they are more writing that will take time away from writing fiction, and so they are worth doing only if they're something you really want to do or would be doing in some form anyway. It's enthusiasm for the ideas I write about and interest in spreading those ideas that keeps me writing on this blog. What keeps you writing yours?

Quinn Reid's Blog

- Quinn Reid's profile

- 6 followers