Quinn Reid's Blog, page 23

September 16, 2011

Seeing a Sudden Drop in Sales of Your eBook?

This is based only on anecdotal information from half a dozen writers or so, but some of us are seeing a sudden, sharp drop-off in sales of eBooks on Amazon over the past couple of weeks. However, I have a hard time imagining that this is a reader trend. In the absence of some major, disruptive event, it seems to me that if the general public were to change its opinion on eBooks, it would do so gradually and noisily rather than suddenly and silently.

I've heard speculation that Amazon may have changed some of their algorithms governing which Kindle books are shown in "also bought" categories and the like. I have no evidence that anything like this has happened, but it would fit the pattern if author-publishers suddenly saw a drop-off in sales because Amazon had changed something that (intentionally or not) favored books that sold a lot of copies and/or that came from major traditional publishers. I worry that some kind of deal may have been cut, especially as I know major publishers are desperate for eBook profits these days, what with other formats all dropping in popularity while eBooks continue to rise, and as Amazon is clearly dependent on major publishers for most of their popular book content.

All of that is nothing but speculation, of course. If it's true, it still doesn't signal the end of the eBook selfpub revolution–but it sure would make an already taxing process much more difficult. If major traditional publishers do ultimately come out on top and completely squeeze out author-publishers, then the new make-a-living-as-a-writer model may be pretty much the same as the old make-a-living-as-a-writer model: sell to an agent who works with a major publisher who publishes the book and gives you some or all of the royalties that are due to you. One improvement, however, would be that if many of the copies sold as eBooks, the writer would receive a much larger portion of the sales price–not nearly as much as they would realize as an author-publisher on a copy of the same book, but if major publishing houses can sell many more copies, the likelihood that a good writer can support her- or himself might go up rather than down.

It's hard to know what to hope for: I've been envisioning tiny author-publisher empires in which we writers are happily giving our readers new books at good prices as we finish them, rather than being stuck in the slow and sometimes painful traditional publishing process. However, large eBook retailers are empowered to squeeze author-publishers out because we need them and they don't especially need us, apart from a minority of especially successful eBooks for which they might make exceptions.

How are your sales? Am I Marsh-wiggling this whole topic? If your sales have dropped off, do you have any speculations to advance?

Photo by m.prinke

September 13, 2011

Breaking Bad Habits by Changing Cues

Here's an article with some useful points about breaking bad habits, based on the results of studies by psychologists at the University of Southern California: "Obesity and Overeating: How to Break a Bad Habit." The key points here are 1) that negative behaviors are sometimes driven more by habit than by short-term pleasure, and 2) that changing minor environmental factors can help break bad habits. While there are many situations where these particular concerns don't apply, they point to some easy and potentially effective methods of breaking bad habits in situations where they do.

September 12, 2011

Three-Act Structure: Answers to All Your Questions

We've been having some lively discussion about three-act structure on Codex, a conversation that was spurred by Film Crit Hulk's post on three-act structure being useless, an allegation I pushed back against in my recent post "Three Act Structure: Essential Framework or Load of Hooey?" (Film Crit hulk posted a rebuttal comment on that post that was worth reading, too.)

Summarizing everything I gleaned from our discussion, I came up with this Q&A which answers all of your questions. (You're welcome.)

Q: Are there different structures that different people refer to as "three-act structure?"

A: Yes

Q: Are any of these structures useless?

A: Yes

Q: Are any of these structures useful to all writers?

A: No.

Q: Are any of these structures useful to any writers?

A: Yes.

Q: Is the version Film Crit Hulk describes useful?

A: No.

Q: Is the version Luc describes useful?

A: For some people, sometimes.

Q: What, if anything, is three-act structure good for?

A: Story arc, character development, keeping the reader engaged, suspense, and emotional involvement.

Q: What is the standard proportion of act lengths in three-act structure?

A: It varies, but some common ones are 25%-50%-25% and 25%-58%-17%.

Q: Are those proportions necessary?

A: No.

Q: Does three-act structure in any form, or for that matter any structure, fit all stories?

A: No.

Q: How about all good stories?

A: Still no.

Q: Does three-act structure completely describe a plot?

A: No.

Q: Do acts in three-act structure correspond to acts in a play?

A: Not necessarily.

Q: Are there other structures that aren't three-act structure?

A: Yes.

Q: Are they useful to any writers?

A: Some people seem to like some of them.

Q: Do some writers produce three-act structure without intending to?

A: Yes.

Q: Do all writers?

A: No.

Q: Can a story use a viable version of three-act structure and still suck?

A: Yes.

Photo by ~jjjohn~

September 9, 2011

Mental Schemas #16: Negativity

This post is part of a series on schema therapy, an approach to addressing negative thinking patterns that was devised by Dr. Jeffrey Young. You can find an introduction to schemas and schema therapy, a list of schemas, and links to other schema articles on The Willpower Engine here.

The negativity schema is an ongoing, oppressive feeling that everything sucks, or that life is very likely to suck soon, or that life has always sucked and is not likely to change. To put it another way, a person with this schema tends to exaggerate or dwell on negatives and minimize or ignore positives, leading to a feeling that everything is in a pattern of going badly. Not surprisingly, such a person tends to spend a lot of time worrying, complaining, not knowing what to do, or guarding against impending disaster.

In terms of broken ideas (see "All About Broken Ideas and Idea Repair,") negativity can shows up as disqualifying the positive ("he just said he liked it because he didn't want to get into an argument"), mental filter ("nobody ever helps when my workload gets out of hand!"), magnification/minimization ("that spilled cup of coffee has ruined my day"), or other kinds of destructive thinking.

People with this schema may try to avoid feelings and experiences, for instance by hiding away at home alone and watching TV for hours every night; or they may surrender to the schema, constantly complaining and expecting the worst; or they might try to overcompensate, for instance by trying to control everyone around them to prevent bad things from happening or by pretending nothing bad ever happens and that everything's always fine–or the schema might come out in a combination of these ways.

Where negativity schemas come from

How does a person get saddled with the idea that life is terrible, or that terrible things are always just around the corner? Often this attitude is passed on by a parent who has the same problems, one who worried constantly or made a point of always highlighting the darkest and worst aspects of life. Alternatively, people with this schema may have had a childhood in which they were always discouraged and their accomplishments or good fortune were never recognized or considered important. Or a person may have experienced much more than normal tragedy and sadness while growing up such that it began to feel like pain and suffering are the main patterns of existence.

Overcoming a negativity schema

Getting past a negativity schema isn't easy: after all, there will always be new tragedies and bad outcomes to point to. Coming to a different point of view requires effort over time to recognize negative thinking patterns and change them. One important change that nurtures a more positive outlook is putting time and attention into recognizing and feeling gratitude for good things that happen, large and small. Another is catching ourselves in the act of amplifying negative feelings and experiences when we use self-talk like "I know this is going to go badly" or "This is awful! What a disaster!" and stating things more rationally.

Of course some things will go wrong: part of undoing a negativity schema is being OK with this, understanding that tragedy is a part of life and that it never means that everything good in life is gone.

In terms of action, a person can fight a negativity schema by spending time with people who have a more positive outlook (and letting them bring the mood up rather than bringing their mood down!), holding back from complaints and dire predictions, and participating in activities in which it's easy to see the good, like volunteering or playing with children without trying to direct the way play goes.

In some cases we can make great strides against negativity on our own, but when any mental pattern feels too big to handle alone, a good cognitive therapist can be enormously helpful.

Photo by Christopher JL

September 6, 2011

Three Act Structure: Essential Framework or Load of Hooey?

Back in July, Film Crit Hulk posted this discourse on the utter uselessness of three-act structure. In case you're not already familiar with three-act structure, it's an approach often recommended as a key tool for writing, especially with screenplays.

The version of three-act structure Hulk takes apart in his post ("setup, rising action, resolution") is indeed pretty useless–but it's not useless because three-act structure is trash: it's useless because it's been oversimplified to the point of being hopelessly vague.

Three-act structure certainly isn't something a successful writer needs to follow, but it can be a hugely useful tool if used properly.

Act I

In effective three-act structure (says me), the first act constitutes pitting the character against the conflict. Generally speaking, the incident that defines the transition from Act I to Act II is the protagonist committing to taking on the central problem; before that there's resistance, avoidance, lack of understanding, etc. Simultaneously, you introduce the reader/viewer to the protagonist and the protagonist's world. Referring to it as "setup" is trouble, because that sounds like you're supposed to dump a bunch of background information or move characters uninterestingly into position.

Act II

Act II starts with the protagonist doing something to join the action, which usually means actively striving to make the situation better. Act II comprises repeated attempts by the protagonist to resolve the central story problem, usually resulting in disasters that up the stakes (hence "rising action," but "rising action makes it sound like it's supposed to be some kind of an upward slope rather than a cycle that gets bigger each time through). I agree with Hulk that the movie Green Lantern sucks on this count, as Hal in the movie is reactive to circumstances instead of proactively trying to do something. It's much more interesting to watch a character push to try to accomplish something–even (or perhaps especially) if that something is ill-considered–than it is to watch the character get hit with a bunch of plot developments and not do anything meaningful about them.

Act III

Act II ends with the introduction of the final gambit: this is where the protagonist commits to an all-or-nothing bid to make the thing happen. Thus Act III is the character trying to make that last plan work and probably having to adjust or reframe right in the middle of it (since if everything works as planned, it's kinda boring).

Five acts?

Hulk points out that Shakespeare wrote in five acts, but Shakespeare's stories can also be considered in the light of real three act structure. The turning point between the first and second acts is where Romeo leaps the orchard fence prior to the balcony scene (Act II, scene 1), after which the two lovers commit to each other despite their families' enmities. They struggle to be together, marry, have their moment of love, and Romeo has his run-in with Tybalt throughout the second act.

Act III is the desperate gambit, Juliet's plan to fake her death and how that pans out (Act IV, scene 1). Note that Shakespeare puts act breaks in both these places.

Formulaic?

If you're concerned that three-act structure is formulaic, I'd suggest that you can ease your mind. Three-act structure is a set of ideas about tension and satisfaction that suggest a way to structure a story. You can't simply plug in the key

Not every good story fits three-act structure. However, it's a very widespread and successful approach to story writing if properly understood. It has certainly been useful to me!

September 2, 2011

Mental Schemas #15: Emotional Inhibition

This post is the fifteenth in a series that on schema therapy, an approach to addressing negative thinking patterns that was devised by Dr. Jeffrey Young. You can find an introduction to schemas and schema therapy, a list of schemas, and links to other schema articles on The Willpower Engine here.

A person with an Emotional Inhibition schema holds back emotions in situations where it would be healthier to express them–feelings like anger, joy, affection, and vulnerability get stifled. This schema is based on trying to act rationally and impersonally at all times, regardless of what's going on inside. Someone with this schema may feel embarrassed or ashamed to feel or express certain emotions or may fear disapproval or losing control. If you find it difficult to tell people how you feel or see yourself coming across as wooden, you may find learning about this schema useful.

A person with an Emotional Inhibition schema holds back emotions in situations where it would be healthier to express them–feelings like anger, joy, affection, and vulnerability get stifled. This schema is based on trying to act rationally and impersonally at all times, regardless of what's going on inside. Someone with this schema may feel embarrassed or ashamed to feel or express certain emotions or may fear disapproval or losing control. If you find it difficult to tell people how you feel or see yourself coming across as wooden, you may find learning about this schema useful.

Where emotional inhibition comes from

People with Emotional Inhibition schemas often grow up in families where expressing emotions is frowned upon, mocked, or punished. Often the whole family–sometimes supported by the culture the family comes from–adopts a similar pattern of keeping emotions hidden at all times. In this kind of environment, hiding emotions becomes an act of self-protection. As the child grows, the habit can be very hard to break, so that someone raised this way can grow up continuing to be unable to express emotion even in situations where it's perfectly safe and entirely constructive to do so.

Overcoming an Emotional Inhibition schema

As with any schema or personal limitation, the first step is to be able to see the problem as a problem. A person who is used to holding back emotions may not appreciate on a gut level the value of expressing them appropriately. It can help to think through the consequences of this kind of expression. For example, what is likely to happen if you tell a friend that you're angry that they didn't show up to an event you'd agreed to go to together–will the friend stop associating with you, or will careful expression of these feelings help clear the air? What are the consequences of telling a family member "I love you"? Is it likely to cause trouble if you laugh out loud in a busy restaurant?

In at least one way, overcoming an Emotional Inhibition schema is more difficult than overcoming other schemas: because Emotional Inhibition encourages handling everything rationally, trying to rationally assess one's own thoughts about feeling inhibited can drag a person deeper into the Emotional Inhibition mindset rather than showing the way out. A person who falls into this snare can benefit from emotional experiences.

Using experiences to overcome emotional inhibition

Any experience that gives a person practice in constructively expressing emotions can help break down a habit of emotional inhibition. By definition these experiences tend to be uncomfortable–after all, people who do this are pushing back against deeply ingrained habits–but realizing this in advance and recognizing the discomfort as a sign of doing the right thing can be helpful.

Some examples of experiences that help with expressing emotions include group therapy, where a highly supportive environment can make it easier and more comfortable to talk about feelings; role-playing; confrontational sports like wrestling and martial arts (Olympic-style Taekwondo has a great sparring component); and dancing or dance lessons.

Spending more time with people who are comfortable expressing their emotions and using them as role models and guides can also make a positive difference.

As with any personal concern, if a schema or other personal issues feel too large or unyielding to handle alone, working with a qualified cognitive therapist can be a way to break through. You might be interested in finding a therapist qualified to work in schema therapy or some other kind of cognitive therapist.

Photo by Mags_cat

August 29, 2011

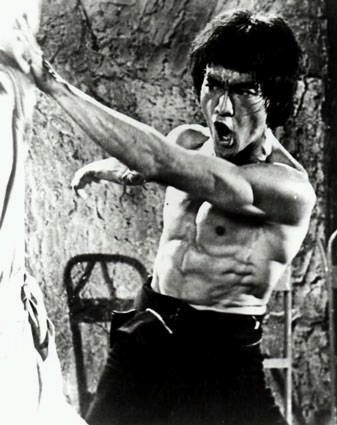

Writing and Martial Arts 2: Writing and Punching

This is the second post in the "Writing and the Martial Arts" series, this post from Steve Bein. For more on this series and on Steve, see the first post: "Writing and Martial Arts 1: How Do You Like Your Chances?"

Bruce Lee said that before he started martial arts, he thought a punch was just a punch. Then, having begun his training, he realized a punch was not just a punch. Then, having mastered the art, he understood a punch was just a punch.

Bruce Lee said that before he started martial arts, he thought a punch was just a punch. Then, having begun his training, he realized a punch was not just a punch. Then, having mastered the art, he understood a punch was just a punch.

Now you may say this sounds like advice from Yoda. You may say it's as inscrutable as a Zen koan. And if you said that, you wouldn't be far wrong; Bruce cribbed this from Zen Buddhism (in the Buddhist version it's a mountain, not a punch, that needs to be understood), and as it happens, Yoda was first conceived as a Buddhist and Daoist master (Dagobah, where he lives, is the name of a Tibetan style of pagoda, a sacred structure in both Buddhism and Daoism). But what I want to take from it here is a comparison with writing.

Before I started writing, I thought writing was just writing. That is, I thought all you did was sit down and type, and then you'd have a story. There's an episode of Californication where Hank Moody's childhood friend voices this view on writing: "I can't believe you get paid to just sit around and make stuff up." The uninitiated in the martial arts have a similar view on punching: just ball up your fist and whack somebody with it.

They're wrong about that. I've told my martial arts students many times that if you spent a year working on nothing but your jab, it wouldn't be a wasted year. People who don't want to waste time studying the punch end up breaking their hands. Their punches are slow, sloppy, and without power. They punch from the shoulder, not from the toes, and worse yet, they can't even understand what it means to punch from the toes.

In my opinion, the same goes for sitting down to write without any sense of the art. It's an old adage that stories amount to interesting characters with difficulties. But how do you invent an interesting character? How do you find the difficulty that is hardest for this specific character, yet one that this specific character is best suited to solve? How do you make a reader care about solving this difficulty? For that matter, how do you get readers to flip to the next page so they'll even find out what the difficulty is?

None of that stuff comes naturally. Every writer must go through a phase in which writing is not just writing. If that weren't true, little kids' stories would be interesting. But they're not—at least not to anybody but their parents. Little kids' stories go, "This happened and then this happened and then this happened." Good stories go, "This happened because this happened, and because of those, this happened." And when they say, "this happened," what that really means is, "this difficult thing happened to this interesting person, and it turned that person's world upside down, and now all of us really want to know how this person is going to set things right."

A good story generates both tension and a sense of inevitability. There is a causal connection between act two and act one, and enough suspense generated in act one to leave readers no choice but to read act two. And that's something we need to learn, and practice, and practice again until we get it right.

My process for this is a lot like my martial arts training. In jiujitsu, for example, you've got strategy and tactics, you've got practice in technique, and you've got actual sparring. Anyone who lacks the patience for the first two gets dominated in the third one. At 170 pounds, I've tapped 400-pounders because they didn't have technique and they didn't have a game plan.

In writing, the strategic and tactical phase—for me, anyway—is a lot of free-form scribbling just to figure out what story I want to tell. In the practice phase I create an outline for the story. Sometimes this is short; other times it's quite elaborate. (My longest outline to date was 41 pages.) The sparring phase is the actual writing itself, and then the editing, and then editing again, doing it over and over again until I've got it right—exactly like jiujitsu, or kickboxing for that matter, or any other art I've ever trained in.

In jiujitsu, sometimes technique fails me and I have to come up with something on the fly. In writing, sometimes the outline fails me and I need to take it in a different direction. In jiujitsu, when I get into a jam where the technique I learned isn't working, I always want to get a technique that will work better. In writing, when I get into a jam where the story I outlined is losing tension, I always want to start a new outline that ratchets up the tension again. And both in jiujitsu and in writing, the most important phase is the first: understanding exactly what I want to achieve, so that my practice and my execution lead to the kind of results I want.

I'm a better kickboxer than a jiujitsu player. Part of that is due to body type—I'm tall and lanky, and at my best when I can keep an opponent at a distance—but most of it is due to the fact that in jiujitsu I'm still at a point where I have to memorize techniques and apply them. That hasn't been true for me in kickboxing for years. The fight just flows. I know what it takes to make an opponent open his guard, and I know what it takes to keep him from advancing. For me, kickboxing is just kickboxing. There's no memorization. Show me something new even once and I can do it. Jiujitsu is not just jiujitsu for me; show me something new and I need to practice it a dozen times right now, and then again at the beginning of the next class, or else I'm certain to lose it.

I'm not at a phase where writing is just writing either. I used to believe that no writer can get there. Now I believe otherwise. In On Writing, Stephen King says he doesn't outline at all, nor does he formulate a game plan in advance. He just thinks of interesting characters and then watches what they do. Harlan Ellison says he writes the same way. If we take them at their word, then for them writing is just writing.

I am still looking for the magic formula that will allow me to do what they do. I don't particularly enjoy laboring over every story. I don't like doing all that free-form scribbling in advance just to throw it away and start anew. I don't like following an outline only for it to lead me to a dead end. I also don't like the process of memorizing one jiujitsu technique after another, just to get tapped because the technique came to mind a tenth of a second too late.

Here's the bitch of it: there is no magic formula. There is only time served. There is only doing it, and doing it again, and doing it again. Sooner or later I will either make myself a good jiujitsu player or I will get so old that my body can't do it anymore. And sooner or later I will either keel over dead or I will discover how to spontaneously create interesting characters, line by line tension, three act structure, and all the rest of it.

I wish I could tell you how. I can't. For me writing is not just writing. Not yet.

August 24, 2011

Codexian Writing Quotes: James Maxey

Continuing my series of quotes from writers I know through the online writing group Codex, here are some memorable thoughts from James Maxey, author of the Dragon Age trilogy and the superhero novel Nobody Gets the Girl. James's latest feat, which floored a number of us at Codex, was writing the first draft of a novel (the sequel to Nobody) in a week. The resulting book, Burn Baby Burn, can be read in its first draft form as a series of blog posts on Maxey's Web site. More on this particular accomplishment will show up in a week or two in my "Brain Hacks for Writers" column on Futurismic.

Continuing my series of quotes from writers I know through the online writing group Codex, here are some memorable thoughts from James Maxey, author of the Dragon Age trilogy and the superhero novel Nobody Gets the Girl. James's latest feat, which floored a number of us at Codex, was writing the first draft of a novel (the sequel to Nobody) in a week. The resulting book, Burn Baby Burn, can be read in its first draft form as a series of blog posts on Maxey's Web site. More on this particular accomplishment will show up in a week or two in my "Brain Hacks for Writers" column on Futurismic.

James is quoted often on Codex, so I'll be breaking up the large selection of his quotes I put together into two or possibly three posts.

Swagger when you lie.

If the WRATH OF GOD couldn't make this character give a sh**, I don't know what might.

The worst novel you ever put onto paper is better than the best novel you are walking around with in your head.

On the other hand, I may be underestimating the appeal of my main character, a homosexual, drug-addicted, Republican, vivisectionist zombie. Sweet merciful Jesus, I wish that last sentence was a joke…

Momentum matters!

I can't sing, play an instrument, dance, paint, sculpt, or act. So, in my early years, I drifted toward writing as my claim to some sort of creative ability simply because it seemed like the easiest talent to fake.

But a completed novel is always going to be haunted by the novel it might have been.

If you have affection and enthusiasm for your characters, then the readers will follow you into some very dark places.

If you and your partner find yourself co-owners of a project that gets optioned for a motion picture and I hear you complain about it on this forum, I will personally drive to your house and slap you about the head and shoulders with a rubber monkey until my envy is abated. And I can be very, very envious.

If anyone wants to power a time machine, the deadline for the first novel you ever sell from a proposal has amazing time acceleration properties. I can only imagine that committing to a whole series must propel you straight into old age.

My motto is, little by little, the writing gets done.

Is Batman really making the world a better place by wearing his underwear on the outside of his pants and clobbering muggers with boomerangs? I think that having your characters learn the wrong lessons from their private tragedies is the key to making them interesting.

… the key to writing a good novel is to first write a bad novel. You're just piling clay onto the wheel at this stage. You aren't spinning the wheel to turn it into something until the second draft.

But, I don't yell. I write. I turn our presidents and judges and televangelists into dragons and I send heroes (or, more frequently, anti-heroes) out to slay them.

Look, I've had it up to here with people dismissing all Yellow-Eyed Beasts from Hell as "evil." The idea that Judea-Christian labels for morality apply to creatures from the pit is an outdated, human-centric view of the world that I hope we, as a society, are finally outgrowing. Baby-eating and stabbing people with pitchforks may seem taboo to most Americans, but what right to we have to impose our values on the denizens of the underworld?

For me–and I can't speak for anyone else–my formula was stupid stubbornness. I kept plugging along despite rejection letters and harsh critiques because I was too dumb to understand that I really was no good at what I was doing and it was time to give up and move on to something else.

The one thing you can do is buy a lot of lottery tickets, metaphorically. Every short story you write might be the one that wins you an award. You never know. Any book you write might be the exact book that a publisher is dreaming of publishing. Productivity is key.

If Jesus himself were to tell me the sky is blue, I'd argue the point. I mean, sure, sometimes the sky is blue, but a high percentage of the time it's black, or gray, or white, or any of the zillion shades of pink or purple you find in the bookends of day.

August 22, 2011

Writing and Martial Arts 1: How Do You Like Your Chances?

I know a small but fascinating group of people who are both successful writers and accomplished martial artists, and as these are both areas of great fascination for me that I practice on a regular basis, I was very interesting to see what connections some of these friends drew between the two disciplines.

The first post in this series comes from my good friend Steve Bein, who is a martial artist with 20 years of training, a professor of Philosophy and History at SUNY Geneseo, and an award-winning fiction writer whose first novel (a thriller about modern crime and samurai history) comes out this coming year. Steve has this question for you: How do you like your chances?

I was told as I entered my Master's degree program of a plan to streamline graduate education. We could dispose of the GRE, of long hours spent walled in by stacks of books, of area exams and dissertation proposals and all the rest. We could weed out everyone who needs weeding out by collecting all of the applicants to a given grad program, lock them all in a concrete room, and tell them to bash their heads against the wall. The last one to quit gets a PhD.

I was told as I entered my Master's degree program of a plan to streamline graduate education. We could dispose of the GRE, of long hours spent walled in by stacks of books, of area exams and dissertation proposals and all the rest. We could weed out everyone who needs weeding out by collecting all of the applicants to a given grad program, lock them all in a concrete room, and tell them to bash their heads against the wall. The last one to quit gets a PhD.

As education reform goes, this plan isn't half bad.. I like my chances in this system. It certainly would be easier to get a PhD in this system than to get one the way I did, with all that old-fashioned writing and test-taking and such. But then, I've been in the martial arts for about 20 years. I learned some things along the way, things about physical and mental punishment, about perseverance, about sheer mule-headed stubbornness when perseverance gives out, and most of all about extinguishing the desire to quit.

Most writers could use some lessons on these counts too. Show me a successful writer and I'll show you someone who has learned these lessons already.

Writing will bring its share of mental and emotional punishment. Count on it. Even as I'm writing this, I'm escaping the frustrations I'm having in working out the plot to my next novel. (Don't worry. I'm only allowing myself 20 minutes of escape. Then I'll go back to that for 20 minutes, then come back to this. My sensei taught me not to quit, but tactically speaking, he and I both recognize the merit of retreating in order to launch a new attack from a different angle.)

There is good reason for a writer to feel frustrated.. 99% of people who submit work never get published. Of the 1% who do, less than half get a second publication. Of those, only a handful make enough money from writing to make protein a regular part of their diet, and even they tend to collect more rejection letters than acceptance letters.

We have a similar formula in martial arts. For every 10 students who begin a martial arts class, only one still comes a month later. For every 10 of those, only one is still training a year later. For every 10 of those, only one earns a black belt, and for every 10 black belts, only one goes on to teach the art. A sensei is one in 10,000. A writer who doesn't need to hold a day job is more like one in a million.

The more I write, the more I learn that the pains of this art go beyond the mental and emotional. I've developed neck problems and chronic eyestrain headaches. Writing cost me my 20/20 vision. I now need yoga exercises to be able to write for any length of time. As it happens, it was martial arts that led me to yoga, but that's not the important part. It was martial arts that instilled in me the discipline to actually show up to yoga classes, to actually do the stretches every day, and to actually keep on writing even when it's uncomfortable.

Charles Brown, the former editor of Locus, once shared some grim but sagacious advice with me (well, me and everyone else in that year's Writers of the Future class). He said if you're a writer, one of three things is going to happen to you: you quit, you die, or you get published. I thought, I like my chances. I'm not going to quit. My sensei drilled the quitter out of me. That only leaves death and publication.

You can read more posts by Steve Bein on the multi-writer blog It's the Story at http://itsthestory.wordpress.com.

Photo by JimRiddle_Four

August 18, 2011

Another ToDoist outage (now over) …

UPDATE 10:54 AM EST: ToDoist seems to be back up

Original post:

For ToDoist users, it appears the site is down again. Last night, Todoist tweeted "We had an 2h outage today, the service should be back up. We are still investigating why this happend, but we think it's related to our host"; 12 hours later, unfortunately, more trouble. Under Chrome I get "504 Gateway Time-out nginx/0.7.13″ and under Firefox, "An unknown error happend [sic] while loading data… We will try to reload Todoist."

This is a great service, and considering I'm getting it for free at the moment, I can't complain much, but I certainly am disappointed.

I'll post updates if I hear anything.

Quinn Reid's Blog

- Quinn Reid's profile

- 6 followers