L.E. Henderson's Blog, page 8

April 17, 2017

Unheroic Heroes

Some action movie heroes bore me to tears. They are too righteous to seem real, too shallow to command my interest. They dash into danger with no fear for their safety. They will give up their life for another without a second thought. They are not characters, but brawny action figures.

Since, as a writer, I am not interested in reading about purely heroic characters, I tend to give my fictional characters flaws. For me, moral complexity creates interest and allows my characters to surprise me in a way that is in sync with their overall personality pattern.

Flaws also create sympathy with my characters and allow me to identify with them. It rounds them out. It makes them believable. But is it possible to go too far? To make them so flawed that readers lose interest? When your fictional hero behaves un-heroically, perhaps even cowardly or cruelly, will readers jump off the ride?

This is a question I have often asked myself, and I have been obsessed with it since my mom read my recently published fantasy novel Paw. My main character is a member of an intelligent cat species, a slave who is attempting to survive and escape the unbearable living conditions of a desert mining camp. At one point in the story, she becomes completely unhinged by a devastating personal tragedy. During her meltdown, she does something horrible that she regrets terribly.

As my mom was reading the first half of my novel, she tossed heaps of praise my way. She raved over how much she was enjoying, and even loving, the book. She even said that she had not been feeling well and that my book was cheering her up.

But after she had finished it, she was strangely silent, so I asked what she thought. I soon discovered that my one sad scene had ruined the whole novel for her. She had complained that what my character did was unjust and that the scene had made her too sad.

I had known the scene was intense, but I had not expected such a sharp descent of her opinion. I reminded myself that the criticism “too sad” is one I have added to my list of criticisms to ignore. Fiction covers the entire gamut of human emotions, and the contrast of despair is what gives hope meaning.

For that reason among others, my mom is not exactly my target audience. She likes books with all-happy endings and “cute” characters. To my mom, the best books are heart-warming, funny, and adorable.

She finds most classic literature to be too depressing. Her favorite movies are by Disney. She is also a serial reader of romance mysteries whereas I have been known to enjoy Kafka-esque dystopias and the brooding Russian anti-heroes of Dostoyevsky.

I had actually been surprised that she had liked the first part of my book as much as she had, much of which was violent. However, it was impossible not to get excited about her initial enthusiasm since I have had very few reactions to my novel so far.

As a result, I was crestfallen that she had been so thrilled about my novel until my pivotal dark scene had apparently blackened out everything she had previously loved about it.

I wondered: Will all my readers react the same way? I knew of at least one exception. The scene my mom had hated was one that another reader had praised highly for is raw, uncompromising honesty. As a writer, I have to constantly remind myself that art is inherently polarizing, and that universal acclaim is impossible.

However, there had been many sad scenes preceding the one in question. I wondered if the main problem had been that my hero had behaved un-heroically

The question is worth asking: Is there a limit to how morally flawed a character can be and still maintain reader sympathy? I have read conflicting advice about this subject. One writer who wrote books for children said that characters must be flawed in order to be interesting and believable; they can in fact be horribly flawed, but they should never be evil.

This has been my guiding principle so far. However, it has problems. How do you define evil? There is an entire spectrum of misdeeds going from parking in a handicapped space to Holocaust level cruelty.

Is one misguided act enough to ruin an entire character or book for a reader? Apparently, yes. There are societal taboos and personal taboos that contribute to this phenomenon. Even I have my limits.

However, because I have been interested in this question for a while, I have consciously noticed when other writers of fiction test common assumptions about what it takes to maintain audience sympathy for a main character.

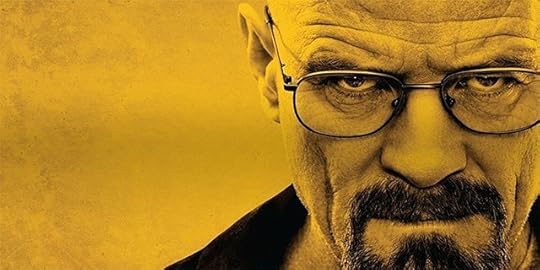

I was in awe of the writing in the television show Breaking Bad, a show about a terminally ill high school chemistry teacher named Walter who begins to manufacture and sell crystal meth in order to provide for his family after he is gone. As the story unfolds, Walter increasingly expresses his dark side. Intellectually brilliant and emboldened by his illness, he becomes a force to be reckoned with as he adapts to the violent world of drug lords and thugs.

He begins to enjoy raking in cash, and his illegal methods give him a powerful adrenaline rush. Enthralled by his thrilling new lifestyle, he ends up endangering the family he originally meant to protect.

One shocking misdeed follows another; his character drifts toward the dark side as he struggles to control his wildly unstable world. At one point he watches the girlfriend of his partner suffer from a grisly death during a heroin overdose, even though Walter has the power to save her. In one of the final episodes, we learn that he has poisoned a child. What fascinated me most about the show was the question, how far are the writers going to let him go? How far can the writers push the boundaries of morality without viewers losing all sympathy for Walter?

Incredibly, I never completely lost sympathy for the high school chemistry teacher turned drug lord. I constantly disapproved of what he did. I certainly did not always admire him, yet he remained a complex, realistic, and dynamic character that always compelled my interest. He never stopped seeming human or vulnerable. Perhaps this was a testament to the skill of the writers or maybe the boundaries between what makes a person good or evil is less clear than we like to think. I actually remember a quote by a writer I read long ago that even the most evil characters can draw sympathy if they only love someone.

Walter White did love his family above all else, however much he sometimes endangered them; maybe that is why the show worked. My character in Paw also loved someone. If my mom cannot forgive her, can I?

I can and I do. While cruelty should never be celebrated, to ignore the shadows that lurk to some extent within all of us is to write shallow fiction. I have no interest in writing a book in which everyone is happy and perfectly good. If I had could only write about saints enjoying themselves, I would not write at all.

Nor am I interested in chaperoning my characters like a stern parent, pulling them back from reckless and unwise behavior to shackle them with my own moral code. What a character does is not necessarily what I think they should do. Plausibility demands the illusion of autonomy. In my mind, my character did what she did because it was what she did, not because I told her to, or because I approved.

But here is the scary question: To what extent does the darkness of my character reflect my own darkness? Maybe more than I would like to think. Fiction wells up from the roiling, murky depths of my subconscious. My character is part of me.

Maybe that was my mom disapproved of most. Like a cruel god, I had allowed a sad injustice to take place in this fictional world where I could have made a different choice.

Nevertheless, I am not sorry for what I wrote. A book featuring slavery should be disturbing, even if the main character happens to be feline.

Slavery is not cute or heart-warming, which is why I have no intentions of pitching my story to Disney. While I hope that not everyone reacts to my character the way my mom did, my story was the story I had to write and the story that wanted to be written. I am standing by it.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my story collection “Remembering the Future” is available for purchase on Amazon.

The post Unheroic Heroes appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

April 5, 2017

How I Vanquish My Writing Monsters

Writing a novel is not just a test of skill; it is psychologically taxing, which means how I talk to myself about it matters. If I tell myself that my writing is awful, I will discourage myself into quitting. If I tell myself that my writing is not awful, just incomplete, I will feel hopeful as I imagine a way forward.

Encouraging myself constantly is essential to finishing a novel. Creating worlds and people no one else can see is a sanity challenge to the most mentally healthy among us. I have bipolar disorder, so I had better be sure that my mind is a hospitable place, that I have cleared it of mental monsters before I settle in; otherwise I can expect the kind if mood crashes that used to make writing too scary to begin and too punishing to continue.

Who are these monsters? They are the internalized critics that shame me for my efforts as I write, the morality police of my childhood who chastise me for not having more discipline, and the dark shadow looking over my shoulder that I call the pseudo-reader, the imaginary incarnation of every troll who ever lived.

I have become adept at getting rid of monsters through years of practice, but sometimes I still forget valuable lessons and find myself slipping back into unhelpful habits of thought. I have to remind myself of what liberated me to write during times of block. Here are five things I tell myself to exorcise my monsters so I can write freely.

Torch guilt and dread with the one-sentence rule

Whether it is for not writing enough or writing badly, scolding myself never pays. Impugning myself as I write only slows me down, makes writing miserable, triggers my creative inner child to throw tantrums, induces despair, and makes me want to quit.

When I scold myself for not writing enough, writing becomes a should, an act of piety, a righteous attempt to appease the writing gods, the sacrifice of a martyr, or – worse – a tedious household chore. If I write because I think I should, or of I am trying so hard to be disciplined that I trigger a procrastination response, I am only working against myself.

Writing is so much more enjoyable when I work with myself. To do this I apply the one-sentence rule. That is, I tell myself I only have to write a sentence a day. The deal I have with my conscience is that as long as I write at least a sentence, my punitive superego will refrain from harassing me. Though I do “discipline” myself to write at least one sentence, it is such a minimal requirement, no resistance ever forms.

This technique is not a way of tricking myself into writing more. Sometimes I really do stop after a sentence. However, when I take myself up on this offer, I usually discover that it is painful to stop; I almost always want to write more and I look forward to my next writing session instead of dreading it.

A great experiment that takes the rule even further is to forbid myself to write more than a sentence. This makes writing seem naughty and alluring. My rebellious inner child, outraged about my arbitrary self-imposed injustice, rushes to the defense of writing. That is what I want.

The one-sentence rule torches two monsters at once: dread and guilt. Writing a sentence induces no dread, and as long as I write at least a sentence, my conscience leaves me alone. The result: freedom!

But does writing just a sentence lead to any real progress? In my experience, it does. There is a world of difference between writing one sentence and writing nothing at all. Writing a sentence engages my imagination while liberating it from pressure.

I cannot help but come up with a second sentence, and forbidding myself to write it is frustrating. If I force myself to stop, my writing-deprived mind will often begin to write anyway; in other words, I write in my head.

If I have only written a sentence during my afternoon, scenes are more likely to appear to me when I am in bed, listening to music, or taking a shower so that when I sit down at my computer the next day, I already have an idea of what I want to write.

Setting easy goals unburdens my mind from guilt, tempts my mind to explore, and eliminates the need to use force. Making myself write is like force-feeding myself ice cream; I enjoy both ice cream and writing; why ruin them with pointless coercion? My creativity can be enticed, invited, nudged, intrigued, and seduced but force, threats, and shaming send it scrambling into a cave.

Banish fear of what others think by writing what you love.

Write what you would want to read, not what you think others want to read. There are many reasons for this. One of my biggest fears has always been having my writing unfavorably judged by others. This fear is perhaps the biggest writing monster of all. But if you write what you love, even if no one else loves it, it is certain that at least one person will be happy. That means it was not a waste of time.

Besides, writing is not lucrative even for most traditionally published writers, but if you write what you love and no one pays you for it, at least you had fun.

Not that there is necessarily a conflict between what you want to write and what readers want to read. If you enjoy writing a story, that vastly improves the chances readers will enjoy reading it. Great writing is not accomplished by writers who are bored with what they are doing.

Another reason to write what you love is that even if you try to write what others will like, you are likely to fail. No one can read minds, and no one really knows what readers like. if there is not enough you in your project, your perspective, your passions, your interests, your writing is likely to limp.

Not everyone agrees. Some editors, agents, professional writers, and publishers advise doing research on what is “trending” before you write, to see what is selling nowadays so you will know who and what to imitate. Hence, the multitude of Twilight and Fifty Shades of Grey clones.

This strategy might lead to sales, but it will not lead to art, originality, or creative fulfillment. However, if I am passionate about my content, it is far more likely that my readers will be passionate about it too.

Regardless, as long as I enjoy what I am writing, I can be sure of having at least one fan: myself.

Writing is made of printed marks, not TNT

Sometimes as writers we take ourselves too seriously, as if the fate of the universe depended upon the turn of a phrase.

We are quick to apologize for offending “the reader”, for inducing negative emotions, for breaking the rules, for being politically incorrect, for violating some hidden standard of literary etiquette. The monster is fear that terrible consequences are likely to occur as a result of writing.

It is easy to forget that writing is ultimately just a collection of marks: lines, squiggles, and curves. More specifically, writing – at least in English –is made of many thousands of variations of the same 26 marks called “letters.”

However, depending on how these marks are arranged, they can arouse intense passions. If you doubt this, read some of the book reviews on Amazon. Some readers hate certain books so much, they call for them to be removed from store shelves. Other crusaders push for books to be banned or removed from libraries.

All of the explosive controversy over printed symbols can be intimidating to a writer who just wants to tell a story. Sometimes as writers, we recriminate ourselves before others have a chance to do it. This book is too depressing, stupid, amateurish, offensive. Why bother? The thoughts are enough to drive us into a deep depression before we reach the second paragraph.

However, good writing is not a manners game. It is about honestly reflecting back life as you see it. Not everyone will appreciate that, especially if it illuminates some corner of life a reader is afraid to explore. Writing is powerful, and oftentimes it requires courage.

But writing is ultimately still just marks, and unless you are defaming someone or calling for an assassination, self-recrimination for writing is usually uncalled for.

Even if you do write a “bad,” book, the world is likely to go on. Few fiascos would prevent you from moving onto new projects. Forget about your writing being good or bad and just write. Make mistakes. Be silly. Be honest. Experiment. Write what you want to see written that you have never seen written before.

Of course I want my work to be meaningful to others, and I hope readers will enjoy what I write. However, I am ultimately the one who decides what does and does not go into it, whether it offends anyone or not. The alternative is fear and paralysis.

Treat a rough draft as a discovery tool, not as a test of talent

For me, first drafts always used to induce performance anxiety and fear of failure. My awkward rough drafts seemed to scream, “Worst writing ever! You are unworthy! Why even bother to continue?”

Writing rough drafts became far less intimidating when I stopped thinking of them as writing. A rough draft is about content, not “pretty language” – although sometimes pretty language happens spontaneously. While that is fine, that is not the goal of a rough draft.

The goal is creating raw material I can mold and shape. I took a sculpture class in college. Whenever I began a project, I would “see” a loose structure in the clay, the curves I wanted to deepen, the forms I wanted to enhance. I would become fascinated with the indentations that suggested the side of a nose or the cleft of a chin.

I react the same way to my rough drafts. A rough draft is material only partially molded to suggest the forms it has the potential to become. This is why I sometimes become truly inspired only after the rough draft is written.

Once I have my partially formed hunk of “clay” in front of me, my imagination flickers. I identify subtle conflicts that have the potential to become major, interesting minor characters who could play a major role if I let them, and barely suggested themes that beg to be strengthened. Messy though it is, a rough draft is evocative.

A rough draft does not even have to be complete to be useful. It is actually helpful to write scenes out of order, the ones I have vividly imagined, the emotion-driven scenes, while I temporarily skip the transitional scenes leading up to them. “Jumping around” leads to a manuscript that would be nonsensical to a reader, but it serves a valuable purpose for me.

If I write down enough of these scenes, a pattern begins to form; a structure starts to emerge organically from them, which become anchor points in the novel. When later I write my intermediate scenes, I will know exactly where they are leading so I am less likely to ramble.

Combat irrational self-criticism with unconditional praise

At the end of each writing session, I shamelessly heap praise on myself for everything I did right, for showing up if nothing else, and I write my accolades down in a file I have named “Therapy.” I want every session to end on a good note so I will not dread going back.

I constantly reassure myself that I am on my own side, that my mistakes do not define me as a writer, and that there is hope for solving the inevitable, and sometimes monumental, problems that are likely to arise in writing a novel. I encourage myself as if I am my own mentor and best friend. I demolish any unfair self-criticisms that may have arisen as I was writing. Keeping a consistent praise file prevents my mood from nose-diving after I leave my computer; that is, I take all necessary measures to keep the monsters away.

But where will my monsters go after I have banished them? As a fantasy writer I am perfectly willing to let my ousted monsters crawl into my fiction and scare the bejesus out of my main characters – as long as the monsters remain on the page and stay out of my head.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my story collection “Remembering the Future” is available for purchase on Amazon.

The post How I Vanquish My Writing Monsters appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

March 17, 2017

I Am About to Publish a New Novel: Paw

I

I

have an exciting announcement: I am about to release my fantasy novel Paw within the next couple of weeks, a book that combines my love of the fantasy genre with my well known fondness for cats. The edits are done. My Amazon file exists. It is around 200 pages and it is ready to go.

Publishing Paw is a big change of my original plan to release my other novel The Ghosts of Chimera first, a 600 page manuscript that was accepted by a small publisher over a year ago. I had major creative differences with my editor and I backed out of the deal so I could self-publish it as I saw fit, but I am not totally satisfied with it yet; getting all the kinks out of a 600 page book is going to take more time than I thought, so I am releasing Paw first.

Paw is about a slave who struggles to survive and protect her family as she works to escape a desert mining camp. The slave also happens to be a cat – a highly intelligent one with speech and bipedal locomotion. Actually, she prefers not to describe herself as a cat at all. This is what she has to say.

I am not a cat. I am a kat. Cats lack the ability to speak and they can only walk on four legs, while an adult kat stands proudly on two. The worst insult you can give a kat is to call her a quad, which is the generic term for beasts that walk on two legs only. Though we kats hate admitting our kinship to quads, if you look at our faces, our whiskers, and our fluffy tails, you will see a striking resemblance to our feral cousins.

Despite being about feline creatures, the story is fairly dark – much darker than I had originally intended it to be when the inspiration for the novel struck.

As is the case with my other novels, my inspiration for Paw was a video game. This story began with the role playing game Skyrim. For fun, I used visual details from the game to do a writing exercise in observation; that is, I would pay close attention to the setting and describe what I saw: soaring castles, ruined temples with stone arches, snow-covered mountains, villages full of waterfalls, bridges, and rivers. I wrote it all down.

Since my avatar was a cat creature, I wrote all my descriptions in first person from her point of view. As I wrote I discovered that she had strong opinions and feelings about what she was seeing. She experienced remorse for those she killed in battle. She saw metaphors in nature. She was curious, sensitive, and sometimes snarky. She was constantly, even obsessively, trying to understand her world.

It was during those exercises that my character came to life. I thought she had a story to tell, and I wanted to let her tell it. I am thrilled to finally release her tale in novel form; it will be my second published novel following Thief of Hades, which was published in 2001. Paw will be the first in a three-part series called the Bastis Archives trilogy.

I have already begun working on the sequel while my real cat competes with my computer for lap space. I will let you know when Book I comes out officially, which will be soon – that is, if my cat allows it. Maybe if I tell her she helped inspire it, she will tuck her paws under her belly and let me write.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my story collection “Remembering the Future” is available for purchase on Amazon.

The post I Am About to Publish a New Novel: Paw appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

March 8, 2017

Seeking the Strange in the Familiar

There is no good reason for me to ever be bored. I live on a rock that is hurtling through space at 30 kilometers per second; I am technically on a thrill ride every day of my life, soaring through space and time, a ride that like any roller coaster will someday end.

So why is it so hard to know it at every moment? Why does life ever seem dull? Why do I obsess over trivialities? Why do I grumble when I lose a sock in the dryer? Why do feel angry at life when I am unable to find the lead on a roll of paper towels?

I lose perspective. However, when I write, I try my best to regain it. As a writer I am constantly trying to wake myself up from the illusion that the world is a tedious, permanent, and predictable place; this is partly because I hate being bored, and partly because stories that assume life is inherently dull are unlikely to move anyone, including me. When I write, I want to go where the passion and the awe is.

One way to make life – and writing – more interesting is to change perspectives often. Because I want my writing to stay fresh, I am always searching new angles from which to see the world.

My writing benefits from anything new I learn, especially if it challenges what I think I know. Science in particular is good for that; it reveals a world that defies common sense expectations.

Quantum mechanics describes a world more bizarre than Alice in Wonderland where electrons can be in two places at once. Science offers a treasure trove of endless fascination for writers willing to delve into it; it paints a veneer of strangeness over the most ordinary objects and experiences.

Studying science moves me beyond stereotypical reactions to nature. My ordinary, knee-jerk response to a maple leaf is “ooh, pretty.” And it may be. However, if I stop to think about what leaves actually do and why they exist, they take on intriguing new dimensions .

Unlike animals, plants are able to make food from sunlight, and usually it is their leaves that do the work. Plants were here long before we were. Without them, humans and most animals would die. In my story “The Age of Erring” my child protagonist gets ridiculed for asking the question: Are plants smarter than people since they, and not people, are able to turn sunlight into food? Food is becoming scarce on her world, so the question – while it sounds silly – is important.

As a teenager my character undertakes an experiment in which she discovers that plants can do a lot more than she ever realized, and that they contain hidden knowledge that has the potential to save her imperiled world.

Other writers have been inspired by scientific findings that defy expectations. Madeline L’Engle, author of A Wrinkle in Time, said that she was struggling with her novel until a friend sent her some scientific findings about mitochondria, which power human cells but have their own DNA. The findings fascinated her, and afterward, she claims, her classic Newberry-Award-winning book practically wrote itself. (See her essay, “Do I Dare Disturb the Universe?)

Other subjects besides science can bring about the perspective shifts I love. In philosophy, no assumption is too sacred to be challenged, including the assumption that anything actually exists. History makes me aware of the passage of time going back way before I was born; it illuminates why the world is the way it is. It reminds me that everything that exists from napkins to cats has a past. Remembering that adds dimension – and strangeness – to everything I see.

Actively looking for the strange in the familiar triggers creativity. It flings aside the curtain of mundane unreality to reveal deeper truths. Our boring sun that we have seen every day for our entire lives is actually a star; from light years away, it would look like just another blinking dot. The body I take for granted is made of atoms, which are mostly empty space, so what am I? When curtains of old assumptions fall away, the sudden shift of perspective wakes me up, engenders awe. And sometimes it makes me want to write.

Some writers are inspired by Big Foot, ESP, and conspiracy theories, but real life is weird enough for me, and I have creative ways of making it even weirder. Viewing the ocean from the top of a Ferris Wheel or listening to music from underwater inspires me. Visiting new places gives me a fresh perspective on familiar ones.

But changing perspectives does more. It lifts me out of the mundane.; it keeps me from losing sight of the big picture so that I am less inclined to grumble about over-priced cat litter, creeping scale readings, and all the inconveniences which create the myth that life is stable and tedious.

In terms of writing technique, changing point of view can put a fresh emotional spin on any story event.

When I was in the sixth grade my teacher would once a week give the class a creative writing assignment to write from the points of view of different animals like a flea, or sometimes even objects like a chair.

I loved trying to imagine what the world would look like from the point of view of a flea; I imagined how long dog fur would look tree-like to such a tiny creature. I even imagined what it would be like to be a chair and my outrage at the indignity of people burdening me with their weight

Although I could never know exactly what it feels like to be a flea (or a chair), the exercise drove home the lesson that there is not just one world, but many, depending on who is doing the observing.

If I ever feel blocked while writing a story, switching points of view breathes new life into it. Suppose, for example, that my story is about a farmer who is murdered. What would the event look like from the point of view of his toddler son who is unfamiliar with the concept of death? What about his mother who is only visiting to bring her son a casserole? What about the chickens? Would a chicken deplore the act after witnessing the grisly fate of its siblings? Each point of view essentially creates a different story, even though the objective event is the same.

To write fiction is to inhabit a world of shifting reality, of paradoxes, of ironies and oxymorons. It means seeking the mystery beneath the obvious, the strange in the familiar, and beauty in places no one expects to see it. In my experience the ordinary always contains the extraordinary. The mission of a writer is to find it.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my story collection “Remembering the Future” is available for purchase on Amazon.

The post Seeking the Strange in the Familiar appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

February 23, 2017

The Elusive Treasure of Honest Observation

Both my mind and my eyes routinely deceive me.

Though this sounds like the definition of insanity, it is also an explanation for phenomena like optical illusions, or why we perceive that the sun is sinking below the horizon when actually the Earth is moving. Sometimes my mind is right. Other times my eyes do a better job at getting at the truth.

When I draw, I depend exclusively on my eyes, even when I know they are lying. I recently considered the many ways my eyes deceive me when I am trying to render objects from life. Giant faraway objects like trees appear smaller than tiny objects like an apple that is right in front of me. Distant objects appear bluer than close ones. If I want to create a convincing illusion, I have to go with what my eyes tell me, even if my mind correctly argues.

When I write, as when I draw, I come face-to-face with assumptions about how things ought to be, and I have to make a conscious effort to see things as they really are.

A few of the assumptions I have held since childhood are: Unhappy people frown and happy people smile; the ocean is blue; grass is green. People are sad when misfortune falls and happy when things are going well.

However, these “obvious” assumptions are not always true. People do smile when happy, but sometimes they smile when they are wistful or even grieving. The seemingly self-contradictory expression, “she smiled sadly” creates a vivid image that resonates as honest because I have seen sad smiles before.

As colors go, grass is not always green, and the ocean is not always blue. Depending on the quality of the light, grass is sometimes bluish, and the ocean green. Dried grass appears brown and sometimes, during a storm, the ocean looks purple-grey.

Other limiting “common sense” notions that my experiences have destroyed since childhood are: vacations are fun; evil people never do anything good; and smart people never do anything stupid.

None of these assumptions have fully survived the test of my experience or even the court of my personal feelings.

I learned early that vacations are not always fun. I had many miserable ones as a kid. When I was twelve, my brother and I got food poisoning at a steakhouse; we spent our week-long beach vacation subsisting on crackers and reading Mad Magazine while lying on the camper bed as sunlight streamed through the window, taunting us. Look at me! I’m the sun and I’m extra bright today. Ever notice that sun rhymes with fun? Heh heh, fun is what you could be having if you could get out of bed without feeling queasy. You could be strolling along the beach eating ice cream. Remember when ice cream used to taste good?

As for “mean” people never doing anything nice, my worst bully in the sixth grade sometimes took a break from ridiculing me to compliment me on my hair. Although her deviation mainly confused me and failed to make my life any better, her compliment makes it hard to say that she was 100 per cent evil.

Some of my other pet notions have shattered only recently. One of them is about birds; I have always thought of birds as delicate, gentle creatures – and many are, especially in the South Carolina town where I grew up. However, I had to adapt to a new kind of bird when I moved to Florida and encountered pig-sized water fowl with muscular wings that generated torrents of wind as they flew, their beating wings like thunderclaps.

Recently I was standing on a Pompano Beach pier and looked up to see a cannonball hurtling toward me, which appeared to be on a collision course with my face. Before I could decide if I should duck or run, the cannonball, which turned out to be a pelican, struck the rail of the pier right in front of me, landing with surprising grace, and gazed wild-eyed at the ocean without offering a word of apology. The lingering fear of being impaled by its long beak left me breathless. This is not a bird, I thought, this is a dog with wings.

If I am ever unsure what to write about, I can always find inspiration by writing down all the things my mind thinks it knows, and comparing them to my actual experiences.

Honest observation is a hallmark of good writing, which – beyond external, objective truth – includes saying how you really feel rather than how you are supposed to feel.

The novels I loved most as an adolescent were the ones that admitted to thoughts and feelings I was afraid to admit myself. They made me want to write about my own experiences in the same fearlessly honest way.

However, when observing places or people for later writing projects I sometimes catch myself self-censoring details I have never seen described in books; at the beach I find myself focusing on the “azure” water, the sparkling wave tips, descriptions I have probably seen many times in novels, while ignoring the slimy seaweed and mud, or the bizarre-looking sea creature flailing on the sand that I have no name for. I have to make a conscious effort to see and appreciate details I have never seen described.

Author John Gardner touches on this filtering tendency in his book On Becoming a Novelist. He said that a teacher in a creative writing class asked students to watch a short skit involving a meeting between a mother, her son, and a psychiatrist. Students were asked to describe what they observed the actors doing. Gardner writes:

One of the most interesting things that happened in this psychodrama was that the woman playing psychologist, in trying to get him to explain himself, repeatedly held out her hands to him, then looped them back like a seaman drawing in rope, saying in gesture, “Come on, come on! What do you have to say?” – to which the son responded with sullen silence. When the drama was over and the descriptions by the class were read, not one student writer had caught the odd rope-pulling gesture. They caught the son’s hostile feet on the desk, the mother’s fumbling with her cigarettes, the son’s repeated swipes of one hand through his already tousled hair – they caught everything they had seen many times on T.V., but not the rope-pulling gesture.

To “write from life,” to write honestly, means honoring what you see even if it makes no sense or seems too weird or complex to fully grasp. An example of a weird human response to bad news happened in my tenth grade typing class.

When in the eighties my high school principal announced the Challenger explosion over the intercom, most students responded with expressions of disbelief; afterward, a somber silence settled over the classroom. One girl came to class late and, sensing something was wrong, asked what was the matter. Another girl told her the news. The tardy girl did not frown, cry, or express alarm; instead, she laughed, a single clipped chuckle.

Her friend asked, “Why did you laugh?” Blushing, the girl newcomer said, “All that build-up on the news, all the trouble they went to, all those documentaries, and this is how it ends?” She shrugged. “It just struck me as funny for some reason.”

A beginning fiction writer versed in the notion that the only “logical” response to tragedy is to frown or cry would be unlikely to include such an exchange in their stories. Through conscious observation writers build ever-increasingly complex models of human behavior, leading to writing that resonates with authenticity.

That is why studying the world when I am not writing is as important as when I am typing at my computer. I keep a file on my phone where I sketch my observations of people and places. At first, I try to observe without immediately attaching words to what I see. That ensures that my content is likely to be original. Otherwise I am likely to think thoughts like, “The water sparkled like diamonds,” a description I have seen in books too many times.

When I do record my impressions in my notepad, I try not to worry about the writing quality; instead I write what I see in language that is almost always awkward. I can always go back and revise my descriptions later if I want, but writing polished prose is not the point of this exercise.

Drawing from life creates a habit of looking for fresh details so that when I do write fiction, my memory has a ready store of original content from which to create. However, observing the world as it is and not as I expect it to be changes more than my writing; it changes me.

To write is to constantly question myself and my long-held assumptions about the world, to open myself to the possibility of surprise. To write is to enter a conflict between appearance and truth as I dive headlong into the eternal question: What is real?

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my story collection “Remembering the Future” is available for purchase on Amazon.

The post The Elusive Treasure of Honest Observation appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

February 12, 2017

Writing Means Believing in the “Real yet Unborn”

Every time I begin a new novel, I feel like a beginner again. In a panic I worry I have forgotten everything I have ever learned about the craft. I search my mind for the encyclopedia of writing techniques that are supposed to be stored in my library of knowledge, but the screen of my immediate consciousness has limited space. Instead of finding knowledge, I find thoughts like this:

You don’t know enough about warfare to write traditional fantasy!

Your last book was pretty good but this one won’t be!

You’ll never finish!

This isn’t going to be worth the energy. Go play Mario Kart!

You used to be smart, but you’re not anymore!

Self-doubts over writing have been with me since high school, but, unlike now, I used to give in to them. Part of the reason I no longer do is that I have finished three novels and three story anthologies. From experience, I am confident that I can and will finish what I begin.

However, the self-doubt committee too often congregates whenever I start to write something new. Their voices are far weaker now than they once were, but their tactics are the same: to attack the worth of my project and my ability to carry it to the end.

To write anything, I need to believe that I can finish my story and that it is worth writing, but at the beginning, my novel is only a tender idea, a seed; it is barely even real.

So the question becomes, how do I believe in something, my book, that does not actually exist? And how do I know my book will be worthy of my Herculean efforts?

The question of worthiness has to do with whether my book will be “good.” No one wants to sink a ton of time and energy into a bad book, yet I can never be certain that my finished product will be the masterpiece I envision. That means I begin every new project on shaky ground. My ideas are born in the unreal space of Imagination Land.

Believing that I will write a good book is different from believing in unicorns though. A book is dependent on what I do, but an idea is only an idea until I convert it into a story or novel.

Is it a stretch to say that writing a book requires a kind of faith? I am a skeptic, so normally I shy away from that word, but psychoanalyst Erich Fromm offered a definition different from the one generally used in a religious context.

In his book The Revolution of Hope, he writes:

Faith is not a weak form of belief or knowledge…faith is the conviction about the not yet proven, the knowledge of real possibility, the awareness of pregnancy. Faith is rational when it refers to the real yet unborn…Faith, like hope, is not a prediction of the future; it is the vision of the present in a state of pregnancy.

While Fromm was probably not thinking of the writing process when he wrote that passage, it comes back to me often as I write. My story concept represents a “real possibility” that is far from certain to be born.

To write a novel, I have to trust that I will be able to solve the many thousands of problems, great and small, that I have no way of foreseeing; that I will someday realize a future product I can only partially envision; that I have the consistency of will to spend however long it takes, many months, perhaps even years, to bring my idea to fruition; and that what I am doing is worthwhile, given the energy and time commitment a novel requires.

Unless I am writing a novel just to learn, I also need – or at least want – to believe my novel will be “good.” But I am a skeptic. I want evidence. I want to do everything possible to make my artistic vision real to me at the beginning. Otherwise, I will give up before my idea ever gets off the ground.

How do I convince myself I am truly capable of making what I envision real?

As for the under-confidence problem, it is sometimes helpful to write down my self-doubts and, in writing, argue back with them.

Accusation: You don’t know enough about warfare to write traditional fantasy!

Response: Fantasy doesn’t require warfare, and even if it did, there is a thing called research.

While arguing with irrational self-doubts is time-consuming, it works. I did it during a period in which I could barely write anything without getting depressed. It created a habit of doubting my self-doubts. I even created a compliment file on my cell phone – a list of compliments on my writing I had garnered over the years. My compliment file gave me devastating evidence to present in the court of internal criticism.

As for believing in a specific artistic vision, the more I know about my story, the more real it becomes. I plan. I brainstorm. I draw mind maps. I ask myself questions about my story and write down possible answers. I write a tentative ending to give me a point to strive toward. I draw maps. I write down any scenes I have vividly imagined. I create character sketches.

I divide my story into three acts, a beginning, middle, and end, then write a four page general summary. It is encouraging to see my story in microcosm, even if I depart from it. Four pages is a manageable length that lets me see structural problems before I ever encounter them.

Anything I do to illuminate my story increases my “faith” that I will finish, my belief in the “real yet unborn.”

However, the most potent way to keep my belief in my story alive is to write on it consistently. I write every day, not because I am disciplined, but because it is easier for me to do that than to write inconsistently. Force of habit is real; it propels me farther and faster than the most moving pep talk.

A writing habit relieves the pressure to believe. It persists even on days I am not sure where I am headed. It does not require me to decide each day whether my chances of success are realistic.

It leads me to ask questions about the present, not the future. Instead of asking, “Am I ultimately going to succeed?“ I ask, “Did I write today? Was it interesting? Did I write what I love? Did my efforts reveal anything new about my novel?”

Such questions allow me to set aside my uncertainty to deal with at a later time. However, eliminating all uncertainty is not just unnecessary, but undesirable. Uncertainty energizes my writing. Creative tension sparks interest. If I knew exactly what my novel was going to look like, a big incentive to write would be gone. Part of the fun of writing lies in being surprised.

While belief in my ultimate success does matter, my love of the process matters more. Love for act of writing, more than anything else, will drive me to the end. On days when self-doubts arise, I spare myself the burden of giving myself pep talks. Instead I ask myself, what can I learn from this? When I do that, it is okay for me to feel like a beginner. There is always more about writing to learn, which means that whether I succeed or fail, writing is never a waste of time.

In writing I need my uncertainty as much as I need my belief. It is in the space between those opposite poles that creativity ignites.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my story collection “Remembering the Future” is available for purchase on Amazon.

The post Writing Means Believing in the “Real yet Unborn” appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

January 30, 2017

How I Know I Have Been Dreaming Since 2016 Ended

Since I have realized I am only dreaming, my relief has been immeasurable.

Not that my dream is all bad. I am dreaming that I recently moved to a place called Pompano Beach. I am living in an apartment with a balcony overlooking a lake, a place where I like to write.

I must have been having this dream since the last day of December. It cannot be real because this place I love is overshadowed by a dystopia, an alternate America presided over by a xenophobic demagogue whose rallying cry is Bring Back Torture.

With confidence and shrugs, he turns crimes into peccadillos. He can brag about sexual assault, then dismiss it as not important and get elected all the same. Real life Americans would never have elected him. My brain hurts. I wonder how long this dream is going to last.

When I do wake, I will cash in on my dream. I will write a novel set in a seedy, Gotham-City-like alternate universe in which such a candidate does somehow get elected president. Maybe I will even include the part about how he locks up America like an airtight mayonnaise jar so no one who looks or thinks differently from him can come in.

Thank you, dream, for giving me such an intriguing, yet implausible, premise.

I am afraid parts of my dream are too implausible for fiction though. In it Russia helped elect the alternative universe president; the CIA said so. Of course, Twitter also helped. Yes, Twitter still exists, even in my dreams.

In fact, I know my current life is unreal partly because I am not on Twitter anymore. Twitter has been an intrinsic part of my life for over three years. Twitter is amazing. It is like another planet, only dimensionless. In Twitter-verse people from all over the world can meet without actually having to go anywhere, which may sound dream-like but it is actually real.

In my waking life, I am totally and hopelessly addicted to Twitter. It is hard to imagine that Waking Me would ever go off Twitter. I try to remember why Dream Me did it, but dreams tend to be hazy even when you are having them. I believe it had something to do with my sanity and my need to save it.

However, I am looking forward to getting back to my Real Life; I intend to fully tweet all about my dream and my unlikely president. For now, instead of tweeting, I obsessively read dream news. It is impossible to turn away. Even though the president is just a nightmare, there is something fascinating about facing your worst fears while enjoying the relief that they are not real.

But sometimes when I do that, I get confused. It is funny how hard it is, even when awake, to know what is real and what is not.

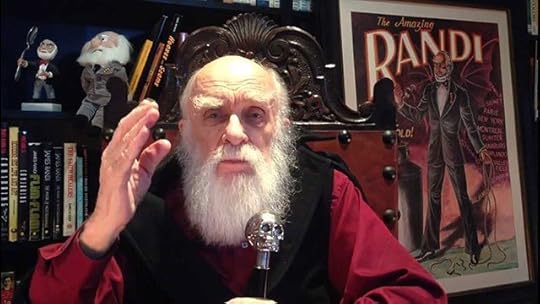

Which brings me to the most exciting part of my dream, a light of rationality amid all the darkness: I have met and spoken to the famous stage magician and skeptic James Randi. 88-year-old James Randi is my hero, along with other like Carl Sagan and Isaac Asimov who were friends with James Randi. They were rational humanists, which means they would not have liked my alternative universe president if they were still alive.

James Randi is renowned, not only for being a magician, but for exposing frauds, charlatans, and faith healers who pretend to have supernatural powers when they are actually only doing parlor tricks. As a stage magician, he was incensed to see liars using tricks to exploit sick, grieving, or disabled people for fame and financial gain.

James Randi lives in Fort Lauderdale, which is close to Pompano Beach, both in my dream and in real life. James Randi has meet-ups every month at a coffee shop which anyone can attend. I dreamed I went to a meet-up and he passed out Skeptic Magazines from his personal collection for my dream self to read – which I have been doing.

Reading them makes me wonder if I should be more skeptical about my conviction that I am dreaming. Nah, just kidding, I am absolutely certain about that.

I admire James Randi because he is dedicated to seeing reality as it is, and not as he wishes it to be. That is a quality too few people possess. In my dream, alterna-verse president lies so much he cannot even stick to his own stories during the course of a single day. Not to mention that he shuns daily intelligence briefings, preferring to govern by fantasy.

In a week, his administration has produced the term “alternative facts,” which could have only come from the Mad Hatter in Through the Looking Glass, which is another reason I know I am dreaming. I wonder: When is this dream going to end?

I want it to end because I have real-life plans. I am going to be a prolific novelist, writing one novel after another, good ones and bad ones, until I fully master the process. I have already written a few, including two I am about to publish. I also have to write my dream-inspired alterna-verse president story, which is my mission now. I just hope I can make it believable.

Therefore, I am trying to figure out how to get back to December 2016 so that I can finally enter the real 2017.

Not that the dream version is all bad. My dark world has a certain beauty. On the personal end, I inhabit a place with a thriving culture, a place where ocean waves are a common sight and where all the restaurants are off-the-charts good. It is in another dream-place called the White House where the dark clouds are gathering; I hope I wake before the storm begins.

Of course, I have little control over that. Until I do wake, I might as well settle in for a while and write on my dream balcony overseeing my dream lake. I will remind myself that the bleak alternative universe president is only a figment of my warped imagination.

I wonder what real-life critics are going to say about my disturbing novel when the real 2017 comes. My guess is that they will find it unbelievable.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my story collection “Remembering the Future” is available for purchase on Amazon.

The post How I Know I Have Been Dreaming Since 2016 Ended appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

January 29, 2017

The Silence Feeders (Short Story)

I.

I have made friends with darkness. There is a warmth in it, the dusky comfort of a plush teddy bear or the soothing delight of just-baked brownies.

I discovered the warmth of darkness two years ago when, at age 25, I lost my vision to a degenerative disease.

At first the darkness scared me. I opened my eyes wide as the color drained slowly from my life. It was like death was coming early, encasing my brain in a deeply buried coffin, isolating my mind as the world around it faded away.

I mourned my ability to see beauty until one day I discovered a different layer of experience – an unexpected world of aesthetic wonder that had been hidden from me. a world of sound and touch richer and deeper than anything I could ever have imagined.

I learned that the most grating sounds, the rattle of a shopping cart, the squeals of children, the shrill cry of the wind during a storm, could become beautiful when you stopped fighting them and just listened.

While I still mourned my sight, I embraced this new dimension of experience, another version of what life could be. All this time it had been there, this other world, sounds bursting constantly like spring blooms underground.

I fell in love with them – the music of the wind, the subtle creaks the house made, the hum of a refrigerator; my new relationship with sound was a gift, and I was grateful to darkness for granting it to me.

On the other hand, silence became my greatest fear; without sound, there was no world, and no me. But most of the time, some sound was there to anchor me to my life

However, it took me many months to fall in love with sound, and to celebrate the darkness that had fully illuminated its beauty.

II.

Beauty. That was something I knew about. I was supposed to have been beautiful – or so I had been told.

But those days were over. Though others could see me, never again would I see my own reflection. I would never see how I aged. I would never know if I was having a “good-hair day.” I was divorced not just from the world but from myself.

Who was my self? All my life I had been my reflection. My mother had taught me where my value lay with an endless sequence of tawdry childhood beauty pageants. She plastered glitzy makeup and bright lipstick to my face, encased my locks in hair spray. I was taught to preen before an admiring audience, to wear frilly sequined dresses, to smile charmingly; I was a toy.

I loved praise, yet I sensed something was wrong. The horror invaded the nightmares of my childhood in the form of rat ghosts.

The dreams began in silence. Then they came, in chirping, skittering packs, claws scraping the floor. I could feel the warmth of their bodies around my ankles. They made a collective chant which sounded like, “You are nothing, nothing, nothing” repeated again and again. They spoke the words with a strange, choppy accent. The word nothing was crisply divided into two emphatic syllables: no-thing.

I would argue back with them. “I am too something. I have won ten beauty pageants. I have the crowns in my closet if you want proof.”

You are nothing, nothing, nothing they chanted. But, even in the supposed safety of my dreams, the rat ghosts hurt more than they scared me.

I could see through them, but they had teeth I could feel. Their incisors sank into my flesh. In my dreams I felt the agony of being consumed alive.

Whenever I dreamed of being alone in a silent room, I would cringe and wait for the horror to begin. I knew somehow that it was the silence that lured the rats, maybe because even in my waking state, I dreaded the prolonged pause, the awkward gaps between words. It was in those empty spaces that critics judged me.

My childhood had been a parade of judges, evaluating the warmth of my smile and the effortless grace of my stride. My mother stressed that I must always look natural, but also happy.

I felt that my mission in living was to be judged perfect by others, to not only look perfect but to wear the perfect emotions. When I succeeded in being the ideal, my mom would love me and bestow a proud smile upon me. The irony was that trying to seem a certain way led to artifice, But, according to my mom, perfection that appeared fake was not really perfection.

The contradiction baffled me. Even as a six year old, I knew a convincing lie was no less a lie than one that appeared plastic. Part of me wanted to reveal my scar to the world, but I knew my mother would never let the world see my major flaw. Every day she painted over it with a heavy cream concealer and finished with a decisive sweep of her powder brush.

The scar had come from a sneaky rat. Not a ghostly dream rat, but a real one. It had climbed into my bassinet when I was a baby. My mother had caught it biting my cheek and scared it away, but she was too late. The rat “kiss” had left an oblong scar, my secret shame. The “beauty” I paraded before the judges was a lie. I lived in fear that the hidden taint would someday expose me as the nothing that the rat ghosts had said I was.

III.

Outwardly I complied. Inwardly I rebelled.

I was eight when I thought to defy my mom, but the fact was, she was bigger than me, so I took refuge in the secret, imaginary life of my future. As an adult, I would rebel against my mom, who wanted me to be a high-paid fashion model. I was dead set on being the opposite, whatever that was. Finally I seized on a vision that enticed me and made my pulse race.

I would become a great mathematician.

I had always made mediocre grades in math, but I rarely did my homework. What if I actually started trying? I always felt sorry for my teacher, Miss Mullins, who could never get the class to be quiet during math lessons.

I became the most attentive student in class. I began asking my teacher questions after the final bell rang. Miss Mullins was so pleased by my avid interest that she could barely contain herself. She would actually sit down with me to explain, her fingers fluttering over the pages of my math book, flashing anxious, questioning smiles. I quickly became her favorite student.

With my determination and her patience, I became adept at solving problems, which filled me with immense pride. My dream was becoming clearer. As a mathematician I would never wear sequins or frills. I would be stately, bespectacled, and powerful.

I would judge others, admiring students perhaps, instead of being judged myself. I would go to symposiums (although I was not exactly sure what a symposium was) and bask in wild applause as others gawked at my genius.

Miss Mullens was beside herself with joy when I attempted some of the “challenge” questions that were at the end of each chapter, the word problems where you had to actually think instead of just following directions.

There were no answers to those questions in the book, so I did the best I could and showed her my answers. Her face broke into a smile of pure delight. I had gotten over half of them right. I was disappointed to have missed any, but Miss Mullins was impressed. She gave me some more of those types of problems to solve. “You know, you really have a knack for this,” she said one day. “What are you trying to do? Be the next Benoit Mandelbrot?”

“Who is Benoit Mandelbrot?”

Her face brightened. “He was a genius mathematician who worked with something called fractals and the mathematics of chaos. If you go far enough in math you will be able to understand it someday.” She smiled.

“I will,” I said. And I meant it.

Miss Mullins shook her head in dismay. “I would never have guessed you were a math person at first. Why the sudden interest?”

“Because I am tired of wearing makeup.” She gave a nervous, baffled chuckle, but I could see the question in her eyes. I wanted to explain more, but held my tongue.

At home my mom taunted me for my new studiousness. One day she saw me at my desk, my head looming over my math book as I scrunched my forehead in contemplation of a baffling word problem.

She marched over to me and leaned down so that the tip of her nose was almost touching the fine hairs on my cheek. “Every time I look at you, you are staring at numbers. You are only eight, Jacquie. Is that what you want to be? A math nerd? You want to be a boring old computer person? An accountant?”

I gave her a direct, brazen stare. “I am just doing my homework, like all kids do.”

She anchored her hands against her hips. “But you spend so much time on it. You never go out and play anymore. A child should be a child.”

I could have told her the same when she was trotting me in front of judges like a show poodle, but I restrained myself. I said with all the dignity I could muster, “I want to be a great mathematician, like Benoit Mandelbrot.”

“Benny…Man…who?” She slammed my book closed. “For the love of God, Jacquie, that is enough. You are smart, you should be able to learn in class the way you used to. Your grades were just fine before, you were passing just fine. A new rule: When you are here, at home, you can spend a half hour on math homework. No more. Do most of your learning in class, like kids are supposed to. Now. I bought you some beautiful new dresses I want you to try on, real silk, too, Easter colors with fine lace trim. We are going to win the spring pageant, Jacquie.” She smiled proudly. “No one will be able to resist you.”

“I hate dresses,” I screamed. “I hate pageants And I hate you. Leave me alone. I am graphing!”

My mom paled. I must have too; my outburst had surprised even me.

Mom jerked my straight-backed chair from under my desk, the wooden chair legs screeching protest against the tile. “I bought you those dresses Jacquie, they cost me a lot of money and you are going to wear them.”

She grabbed my upper arm and pulled. I planted my feet hard on the floor, leaned forward, and clamped my fingers around the front edge of the desk, causing it to tilt. A loose sheet of graphing paper went sailing to the floor. As I reached for it with my free hand, my mom released my arm and yanked my hair to pull me out of my seat. The pain was a thousand needles pricking my scalp. I began to cry.

Minutes later, I was squeezing into a frilly Easter-egg-green sequined dress and sparkling shoes.

“Oh, oh, wonderful. It contrasts so beautifully with your red hair.” Mom stood back and clapped her bony hands. “This is what you were meant for, Jacquie. You need to work on your walking though. You seemed a little klutzy last time, which was why you lost the snow pageant. I am going to sign you up for charm school. Maybe it will fix your attitude problem along with your walk.”

“No, “ I glared at her. “I am plenty charming already.”

“Oh?” My mom chuckled, then looked at me with wistful adoration. “You are so lucky, Jacquie. When I was a kid, I would have given anything to look like you. You take me back to my own childhood. You look like the girls I always envied, the popular ones. I only want the best for you. You can have the life I never had.”

I fought her the best I could, but she enforced the thirty minute math rule. She kept a close eye on me.

I tried spending extra time on math homework, sitting on the edge of the tub in the bathroom with my number 2 pencil, but when my mom noticed how much time I was taking, and how I was dragging my textbook into the bathroom, she made a rule that I could no longer lock the bathroom door. She began bursting in on me. It was so traumatic and embarrassing, I began associating fractions with ignominy.

IV.

At school I listened in class the best I could, but without adequate time to do my homework, my grades reverted to mediocrity. I did not even know what questions to ask after class anymore. I could not look Miss Mullins in the eyes anymore. I knew I had disappointed her. She had been bragging on me whenever she passed out the graded math test. Now she was silent as she returned my tests. Now and then, sitting in her desk, she would look at me with perplexed concern. Abruptly I would turn my head away. It was unbearable to think I had disappointed her.

After the school year ended, I left my dreams of being a female Mandelbrot behind me. They seemed as silly as being a cowgirl. In adolescence others told me with admiring glances that my looks were the closest I would ever get to genius. I wanted to be some kind of genius, or at least special in some way, so every morning, I continued the tradition of sweeping a concealer brush over my scar.

During my teenage years there was a portrait I internalized as being the essential me. At age 15, I had a boyfriend who was a poet. According to his poems, there was something “eternally child-like” in the “rosy glow” of my skin and the “subtle pout” of my lips, and the “innocent curiosity” of my green eyes. He wrote that the sheen of my straight auburn hair was the kind that attracted people to ripe strawberries in summer.

The message from everyone I knew supported his message, “You are here to reward the world when it looks at you. You do it well, so for the love of God, never age.”

To compliments, I responded with a sort of queasy pride and a despairing dread of someday losing the only quality that had ever secured love from the world.

In high school, I felt the pull of interest from certain subjects from Latin to biology, but I painfully remembered my stillborn Mandelbrot fantasy. I was afraid to get attached to academic subjects, only to disappoint more teachers.

My mom got me modeling jobs with local department stores to fill my afternoons so, again, my studying time was limited.

Now at age 27 I was blind. I could no longer confirm for myself, through my mirrored reflection, who I was, I had never developed a rich inner garden, a poetic soul, an erudite mind, a personality with depth, or a self with multiple dimensions. I was completely dependent on others to define me.

V.

I soon learned that blind models were not much in demand. The curious flash of my green eyes had been my most alluring charm, photographers had told me, and now the life in them was gone.

I wanted to console myself by looking at the world outside myself. If I could not be beautiful, I wanted to admire beauty. I wanted to look at the shimmering surface of a lake or the way a falling leaf rocked slowly to the ground. To see outside myself could have soothed me, freed me from my self-conscious prison.

It was on a cool spring day that I discovered the new dimension, a porthole of escape. I was shopping in a crowded grocery store with my brother, when the clamor of screaming babies and rattling grocery carts assaulted me with such force, I thought it would knock me down.

Being blind was too noisy, I thought. There were no images to compete with the daily clamor, so I received the full brunt of it all the time.

That day I was especially tired, so instead of resisting the noise, as I usually did, I surrendered to it. I let the noises fill me. I tuned in to the grating sounds with full interest, and something incredible happened; they stopped being grating.

The shopping cart had a rhythmic, almost musical rattle. The squeals of children had fun in them; peace settled over me as I remembered my own childhood, the good parts like unwrapping Christmas presents or eating ice cream on a sweltering August day. I even found an enticing rhythm to the beeps of the scanners. Like Mandelbrot, I found patterns in chaos, and the result was music rich with wordless meaning.

I still missed my sight terribly, but far less than I once had. Although I had always been able to hear, I had never truly listened before now. What I found was an intricate fabric of nuance and natural rhythms that made the darkness more than bearable.

Sounds eased my sorrow to the point that I stopped pitying myself; my new relationship with sound was a gift.

Rattling, ticking, pealing, chiming, humming, sound became my drug, my addiction. I could not sleep without some kind of noise — relaxing music, a fan blowing, a recording of ocean waves.

I analyzed sounds, how they had form and texture, how they were round, hard, soft, and rough. Sounds moved. Like ocean waves, they rolled in and they rolled out. I mapped in my head the way certain parts of the house sounded and, with my cane and the help of my brother Zack, learned to avoid bumping into things.

However, my pleasure had a flip side: a fear of silence. I dreaded pure silence like I dreaded my own death. Even the pauses between words made me cringe because it was then that the silence feeders came.

In listening carefully to sound, I believed I had unlocked a door of my imagination where the haunts of my childhood dwelled, entered a zone between reality and illusion; maybe blindness was driving me insane, but whenever the external sounds stopped, the internal noise began.

Do the blind hallucinate? I must have. Or perhaps I really did enter a new dimension when I lost my sight.

Whenever silence fell for long, a soft, chittering chorus took its place, the same sound the rats had made in my childhood nightmares. Though I could not see them, again and again, they said the word I remembered so well: You are nothing.

It was not just the words that disturbed me, but the way they made me feel. When the words were spoken, I could feel a visceral hole opening up inside me, a chasm of loneliness; I could feel the nothingness trying to consume me, and I fought the feeling with all I had.

It was harder than it sounds. The feeling that I was nothing was not vague, but powerfully convincing. That is why, months after the silence feeders had re-entered my life, a simple power outage became a disaster that threatened my belief in my own existence.

VI.

The torture began on a mid-January day of cold rain and sleet, which had abated for a time.

I did not see the lights go out, but when the electricity died, I knew. The sounds I depended on for a sense of security all stopped at once, the stereo, the lively lilt of television voices, the watery, thumping gurgle of the dishwasher.

Gone too were the faintest sounds I had always taken for granted: the calming hum of the refrigerator, the whoosh of the heater through the floor vents, the rhythmic ticking of my wall clock.

Without a working heater, the house iced over quickly. I went to where I remembered the floor-to ceiling living room windows being to make sure they were tightly shut. They were, but I could feel the hard chill of one of the window panes when my fingers grazed the glass surface.

I could feel the silence, not just around and inside me, but in the weighted chill of the air. I grabbed an Afghan from the sofa as, by memory, I made my way toward the fuse box next to my bedroom door.

Even the Afghan felt clammy around my shoulders, as the cold wet tickle of the air invaded my lungs. My heart percussed against the walls of my chest cavity as I struggled to breathe the icy air.

The worst part was not the cold, though, but the dread. In my mind I was a child again, a six-year-old dreaming of an ominous empty room and waiting for the horror to begin. I told myself my worries were silly. I was an adult now, and if I was dreaming, I would be able to see; despite my blindness, all my dreams were visual.

Trapped in darkness, my imagination must have gone wild; an odd synaptic tumble drew me into the looking glass. It began with a whisper. At first I mistook it for wind, but it grew louder into what sounded like the collective murmur of human voices.

I hugged myself as tightly as I could to quell the trembling. I am dreaming, I told myself, maybe I am having a non-visual dream after all.

But the immediacy forced me to recognize the sound as reality. As in my childhood nightmares, skittering sounds and squeaks and panting filled the room along with the unified, genderless voice of a crowd.

The voices and, I assumed, their owners, surrounded me. You are nothing, you are nothing, you are nothing, the crowd-voice said. The words echoed darkly in the chambers of my mind as I felt something inside me give way, some desperate speck of imagined existence that I called my self. I planted my palms over my ears and screamed, “I am not nothing.”

Doubts made me falter. I was older now. I could not see or drive. My job options were limited. I was sure whatever beauty I possessed must be fading, or would fade soon, the walls of my being disintegrating, revealing me to be the empty shell, the useless object, that I was.

You are not an empty shell, I told myself. This is just a dream.

At that thought, I felt something bite my ankle, then my foot. With a sharp gasp, I swatted at the invisible culprit with flailing hands, teetering on the edge of absolute panic. I felt the resistance of furry bodies seething around me, clambering over the arch of my foot, as I made my way, panting, to the fuse box.

With a cry of hope, I found the small metal door embedded in the wall beside my bedroom. I pulled switches with the frantic desperation of someone trying to defuse a bomb.

Then I felt them swarming, felt their solid weight on the top of my sock feet, the warmth of their coarse fur, and their hard bites. When I flipped the last switch, I lost my balance. I slammed on my side and hit the floor shoulder first.

My bones vibrated with pain. As I struggled to recover control, to rise, the furry creatures surged over my prone body, scrambled over my legs, arms, and face, clawing and biting me. Screaming. I slapped them away. The true torture was not the bites themselves, but the feeling that they were stripping away my outer shell to reveal the true horror: that they would find nothing inside.

With that thought, I lost consciousness.

I woke. With relief I realized The power had returned.

I inhaled the warm whoosh of a heater, took in the humming lullaby of the refrigerator. “I am here,” I told myself, “I am not nothing.” I felt myself, my arms, my face, my hair, to reassure myself that I was real and solid and alive. I ran my hands over my arms, ankles, and face. I expected rough sores where the rats had bitten me, but there was nothing, no blood, not a sign of damage

Yet the suffering had been unbearably real. Had I gone insane? The question mattered less and less as sounds lit the shadowy recesses of my mind with life.

VII.

Though often derided, fear is more than the irrational emotion of children and cowards. It is not just dread of imaginary future suffering, but the memory of past suffering transformed into anxiety.

Over the next couple of days, I knew fear. Most people think of monsters as inhabiting the dark, but I now knew that darkness was harmless. It was the monsters that haunted silence I most feared.

I became a sound glutton. I added more and more sounds to the house, mostly electrical – synthesized bird song, music, nature sounds, multiple loud fans until the cacophony made thinking impossible.

When my brother protested, I encouraged him to wear earplugs, but he refused to do that for long. When he was home, I had to turn most everything off. I would slide padded headphones over my ears, shut the door of my room, and numb myself with loud music, good music or bad; it did not matter.

I caulked the cracks between moments, plugged any hidden holes through which chanting ghost rats could sneak, so there was no way for thoughts about being nothing to take over. I created a life of clamor, a never-ending circus, a clanging, chirping, screeching mayhem.

One day it became all too much. I had a severe headache that day, and the clamor made it worse. The drumbeat of the stereo was pulsing in time with the angry throb in my temple. Exhausted, I realized how much my clumsy auditory armor was weighing me down. I knew that what I had created was not beautiful anymore – far from it. All around me was the strident music of compulsion. It was ugly.

I decided right then that I was done with running from silence, or from the beasts – real or imagined – that I called the silence feeders. It was too much work. I had to face them, or live a life of strident clamor and fearful turmoil.

Maybe by confronting the silence feeders repeatedly, I would discover that they were not real and could not truly injure me, no matter how much their ghost bites hurt. Then, maybe I would heal; if not, at least the torturous struggle to save my self would be over.

If I truly was nothing, I wanted to know

VIII.

On the next night when I was all alone, a Tuesday, I went into my living room, feeling my way with my lightweight cane, hearing its gentle, reassuring click, click, click against the bare hardwood floor.

I had memorized well the locations of all the power switches. I clung to the walls as I circuited the house. I killed the stereo and silenced the television. I turned off the fans. I even unplugged the refrigerator. Fumbling, I removed the batteries from the wall clock. I softened my breathing.

Each time a sound went away, I felt more naked. The hole of my loneliness engulfed me. My hands trembled. My teeth chattered.