L.E. Henderson's Blog, page 12

March 15, 2016

The Awesome Privilege of Artistic Failure

How do writers and other artists live with the knowledge that despite their best efforts, they might fail?

A couple of weeks ago I blogged about a book that “sells” an answer that question – Big Magic, written by mega-bestselling author Elizabeth Gilbert. Anyone who read my blog knows I did not think much of the book. A reader told me that a lot of the ideas Gilbert had mentioned in Big Magic had also appeared in her world famous TED talk, which was watched by millions.

I felt compelled to watch the video and, when I did, I realized that I had more I wanted to say about her ideas, particularly her strangely dim opinion about artists accepting personal responsibility for their art. In her TED talk, Elizabeth Gilbert makes the extraordinary claim that the terrible pressure of artists taking either blame or credit for their art “has been killing off our artists for the last 500 years.” What does she mean? is she talking about artists going extinct like the wooly mammoth? When I last checked Twitter, there was no artist shortage; in fact, there seems to be more artists than the world knows what to do with. Besides, almost everyone who has lived during the last 500 years has died.

So does Gilbert think that humans are fragile souls? We have survived famines, Ice Ages, plagues, pestilences, earthquakes, wars, and fearsome predators, yet taking responsibility for having written a good or bad story kills us? According to Gilbert, essentially yes. She argues that, as artists, we need a “protective construct” to shelter us from fears of failure and to keep us from soaring too high on tsunamis of praise.

Her “protective construct” is for us artists to stop taking either credit or blame for our work, and to instead give credit to our elusive “spirit guardians,” whom Gilbert believes are responsible for our best ideas. “Stop thinking this extraordinary energy comes from you,” she says.

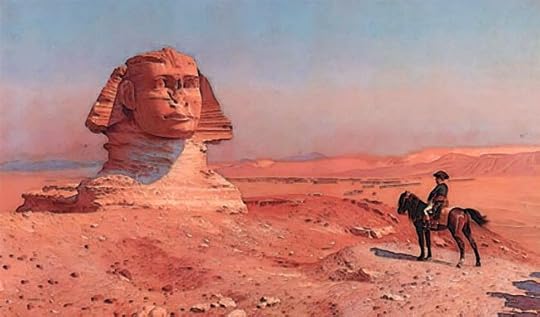

Our overwhelming sense of personal responsibility, she argues, is an ugly outcome of the Renaissance. Before the Renaissance, she says, the Greeks and Romans believed, more “sanely,” that artists, instead of being geniuses, had geniuses – creative spiritual beings that gave artists their greatest ideas, removing the terrible burden of responsibility of art from the artist.

To prove that humans must have relief from artistic responsibility, Gilbert makes some bizarre assumptions. She assumes that artists claiming responsibility for their art is the main cause of mental illness, addiction, narcissism, and suicide in creative types. Where is she getting her information? Does what she is saying align with what mental health professionals say about the causes of mental illness, addiction, and suicide?

From all I have read, mental illness has roots in the biochemistry and physiology of the brain. That is why drugs like lithium relieve symptoms of bipolar disorder. Mental illness also tends to run in families; it has a genetic origin. Environmental factors may also play a part, but how much of a part is hard to say.

Does taking responsibility for the success or failure of artistic creations bring latent mental illness to the surface? Or does it go further and turn normally sane people into mentally ill ones? Does accepting blame of credit for art cause a mentally healthy person to contract bipolar disorder?

It is true that mentally ill people tend to be drawn to the arts, but did art make them that way, or is mental illness somehow conducive to creativity? No one is quite sure. What we do know is that not everyone who is mentally ill is an artist, and not everyone who is an artist is mentally ill. Some of my favorite writers such as Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Carl Sagan never ascribed credit for their work to spirit guardians, yet they never suffered from mental illness or addiction; in fact, overall, they were happy with their lives.

Were they freaks? How did they manage to evade the unbearable burden of taking credit for their work? Maybe it is clear by now that I totally disagree with Elizabeth Gilbert about almost everything. Her arguments are fear-based and I do not believe taking responsibility for art causes mental illness.

I have bipolar disorder, and it manifested long before I began writing regularly. My problem with Gilbert is not just her fuzzy thinking and acrobatic feats of illogic. For me, the issue of being able to take ownership of my art is personal.

I lived most of my life with the “elusive genius” theory of creativity, but I called it the “elusive muse.” I had experienced those rare moments of euphoric inspiration that seemed to come from nowhere; the rest of the time, I was chronically frustrated because I was unable to summon that altered state at will.

Believing creativity was beyond my control kept me blocked for many years that I could have been writing. While I did not believe that inspiration is literally magic as Gilbert does, I did think of it as an elusive force I was helplessly dependent upon and terrified of scaring away.

Gilbert fuels that fear in her book on Big Magic by warning artists that the best creative ideas will “lose interest” in you unless you act on them at once. She claims that when inspiration strikes, you must not hesitate; to keep an idea from dashing off, you must make a “contract” with it promising to express the idea to the best of your ability; if you neglect to fulfill your promise in a timely manner, the idea will scamper off and seek representation elsewhere.

But back to my story: After a long spell of creative drought, I finally realized that writing was an act of will; it was not about waiting to be acted upon by a mysterious outside force. What makes writing special, what makes it art, is the fact that, from start to finish, I create it.

Gilbert says that most of the time she spends writing is just “unglamorous labor”; to her, that kind of writing is nothing special; it is only special if it comes from outside her. I could not disagree more; there is nothing special about being the conduit of something else. I am an artist, not a secretary.

But what about that euphoric feeling I used to get when an amazing idea would strike? Did I give up on that? For a while, I did. I stopped expecting it. I stopped trying to force it. I told myself, “Just write a sentence.”

When I limited myself to a sentence, I had a happy surprise: I almost always wanted to write more, and it took discipline to stop. In other words, I rediscovered my desire to write so that I no longer needed to force myself.

Writing became fun again. I stopped clock-gazing. I began writing whenever I chose, and I stopped whenever I chose. At every moment, my writing came from a place of wanting, so I ended up writing a lot. It became easier and easier to enter the relaxed state where ideas flow freely.

There were no spirits at work. Everything I experienced is explainable by what goes on inside my mind. I read an insightful book on the psychology of creativity called Writing the Natural Way by Gabriele Rico. It offers practical ways to make the mental shift that I associate with focused creative activity. It made me aware that I had control over the experience of most people refer to when they say “inspiration.”

However, I do sometimes suffer from anxiety about sharing my work. Here, Gilbert did me a big favor; she made me realize that I want to take credit for my mistakes. They were how I learned. By trying to convince artists to surrender the privilege of claiming their errors, Gilbert has made me determined to keep it.

Even if my writing fails on every level, despite my best efforts, failure is not bad. It means I tried. It means that of all the passive things I could have been doing, such as watching television, I chose to do something exciting and risky, even knowing that I might be ridiculed for my efforts. Failure means that my love for writing overcame my fear of looking foolish. That is not a disaster, but something to celebrate.

The freedom to claim responsibility for my writing, all of it, the good and the bad, is a gift. Without the possibility of failure, there is no triumph in success. Any art worth doing is an expression of courage; without risk, courage withers and art loses its power. Believing fairy tales to ease my fears is not the answer, which is why if I ever see a “spirit guardian” trying to seize control of my hand as I type, I will not make a “contract” with it; I will call an exorcist.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my new novel “The Ghosts of Chimera” will soon be published by the folks over at Rooster and Pig Publishing.

The post The Awesome Privilege of Artistic Failure appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

March 8, 2016

What Is Up With Fantasy Writers and Riddles?

When I write short stories, I love experimenting with fantasy tropes such as dragons, trolls, and prophesies. Though they may seem trite, I like to see if I can do anything with them that has not been done before: play with them; flip them upside down; personalize them; use them as metaphors that represent psychological truths.

One of those fantasy elements, which I see over and over, is riddles. Among the most famous are the riddles Gollum gives Bilbo Baggins in in The Hobbit. They are clever and even poetic.

Voiceless it cries.

Wingless flutters.

Toothless bites.

Mouthless mutters.

(Answer: wind)

J.R.R. Tolkien was not the only one to use riddles. J.K. Rowling used one for the climax in the Harry Potter series: “I open at the close,” referring to an enchanted Snitch that would only open once Harry was willing to die. And Stephen King used riddles extensively in The Dark Tower series in his confrontation with a smart-mouthed, evil train.

Why do fantasy writers like using riddles in their fiction? What is their appeal? Why are monsters and trolls constantly challenging heroes to battles of wits? Maybe it is partly because, if you are fighting a magical entity immune to fisticuffs such as a ghost, a demon, or The Grim Reaper, you are not going to win with a swift uppercut to the jaw. A different kind of battle, a more cunning one, is needed.

Also, riddles engage readers by making them part of the struggle against an enemy. If the reader gets the riddle right along with the hero, he shares in the feeling of triumph. But why are riddles such an entrenched tradition in the fantasy genre specifically?

I did some research on riddles. After answering some of them, I am beginning to understand why monsters and fantasy writers like them so much. They challenge both the intellect and the imagination; they imbue the world with mystery and magic; they make common objects irresistibly strange.

An example: The more you take of me, the more of me you leave behind. What am I? It sounds like something that could only exist in another universe. To solve it, my first impulse is to try to think of some item I can grab and stuff in my pocket, something that would magically replenish itself tenfold as I stepped away.

Of course, that is logically impossible. The puzzle depends on a quirk of the English language that turns the ordinary answer, which is “footsteps,” into something more than itself; the riddle propels footsteps into the world of magic.

At the same time, the puzzle brings attention to the odd expression “take footsteps.” The expression makes no sense at all when you analyze it. No one reaches down and takes footsteps by hand; if anything we make them. But for a moment the riddle leads you imagine that somewhere in the universe there is an object that magically replenishes itself after you take it.

Riddles are perfect for the fantasy genre because, through linguistic slight of hand, they transform boringly common objects into mysteries. The common practice of phrasing riddles in self-contradictory terms makes the answers seem as if they could not possibly exist in a universe built on orderly laws of cause and effect. Some examples:

How can a pants pocket be empty and still have something in it?

What word becomes shorter when you add to letter to it?

What has four eyes but cannot see?

What has hands but cannot clap?

In case anyone wants to solve them, I left out the answers, but these are all classic riddles, so you can find the answers quickly on Google. My point is that many riddles depend on contradictory phrasing, but the contradictions are illusions; usually they depend on a linguistic knot.

What goes up and down without moving? When I first heard this riddle, my mind went in two opposite directions at once. I imagined things that move and things that are absolutely still, and tried to reconcile them into one object, which is impossible.

The correct answer is “a staircase.” There is no contradiction, because a staircase does not really go up or down; it does not go anywhere at all. It is just a hunk of material constructed in a certain way. We say that a staircase goes up or down only because of how we use it, but the inaccurate expression was like a wand that enchanted the staircase.

These observations of how riddles work are new to me because, until recently, I have never given them much thought. But after having fun with them and getting stumped by them, my opinion of them had improved. Riddles enchant common objects; they probe into the nature of death, time, fate, and nothingness. They awaken a sense of wonder that makes you feel like you are encountering a common object or idea for the first time.

Riddles require a different way of thinking. They celebrate paradoxes. They employ ingenious metaphors. They frustrate. They illuminate. They misdirect. And solving a challenging riddle comes with a soaring sense of triumph.

As a fantasy writer and unapologetic nerd, I decided that I should be able to write riddles as well as J.K. Rowling, so for practice I made one up. “As I sit, I go far. To tell truth, I lie. With a touch of my fingers, I make dragons fly.” As far as I know, there are not any other riddles about fantasy writers, but if any of you can think of any, let me know.

There are more practical reasons to write riddles than building nerd cred: In case the Grim Reaper ever comes to my doorstep in a sporting mood, it is not a bad idea to be prepared. I will have a far better chance of winning a battle of wits with Death if my riddles are not ones he has heard before, and, like any self-respecting metaphysical entity, he is bound to have read The Hobbit.

Maybe if my riddles are clever and challenging enough, I can keep Death afraid of me. Or better yet, he will become so addicted to my riddles, he will want to keep me alive. Or, best case scenario: he and I will become so chummy, he will read my books and write reviews of them on Amazon. Favorable ones, I hope. I hear death has a lot of clout in the literary world – both here and beyond.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my new novel “The Ghosts of Chimera” will soon be published by the folks over at Rooster and Pig Publishing.

The post What Is Up With Fantasy Writers and Riddles? appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

March 2, 2016

Is Writing Magic?

Years ago I stopped reading books that gave writing advice. Too often, instead of helping, they confused or even discouraged me. So last Christmas someone who knew I shunned books on writing decided that maybe I would enjoy a book on the more general topic of creativity.

The book was Big Magic by best-selling author Elizabeth Gilbert, who wrote the phenomenal hit Eat, Pray, Love. However, I did not think I needed the book. I have written my own book on creativity that chronicles my journey through a severe case of block. When I got over my block, I really got over it. Inspiration is not hard for me anymore. Creativity is something I practice every day, like putting on shoes.

That is why the book Big Magic stayed on my book shelf for months until someone suggested to me that I ought to at least open it up and look through it. With a sigh, I relented. I am interested in the creative process after all; I thought that maybe the author could add something to what I already know, so I picked it up and leafed through it.

At first I was charmed by the playful, humorous, and informal writing style. I surprised myself by actually liking the book – until Gilbert began describing how creativity “works.” Suddenly I found myself tumbling down a rabbit hole and through a kaleidoscopic looking glass.

Gilbert claims that creative ideas originate from outside their creators. According to her, divinely inspired ideas float around seeking human hosts who will nurture them and transmit them to others; discovering these pre-existing ideas requires “receptivity.” When one of these ideas visits you, she says, you undergo physical symptoms like sweating palms, euphoria, and even nausea, a response resembling that of falling and love.

Once you agree to accept responsibility for the idea you have fallen in love with, you enter a “contract” with the idea, in which you promise it that you will do everything possible to bring it to fruition. If you neglect your duty, the idea will consider the contract breached. It will lose interest in you and move on to someone else.

Gilbert writes, “I believe inspiration will always try its best to work with you – but if you are not ready or available, it may indeed choose to leave you and to search for a different human collaborator. This happens to people a lot actually.”

At first I thought Gilbert was joking, but to erase any doubt, she frankly states, “When I refer to magic here, I mean it literally. Like in the Hogwarts sense. I am referring to the supernatural, the mystical, the inexplicable, the surreal, the divine, the transcendent, the otherworldly. Because the truth is, I believe that creativity is a force of enchantment – not entirely human in its origins.”

It is not uncommon for writers to describe the creative process in mystical terms, but I usually assume they are speaking metaphorically, not literally, about how writing feels. Fascinated, I continued to read.

Gilbert tries to prove her claims with an anecdote about a novel she began long ago. She was writing it with enormous enthusiasm until a personal crisis forced her to set the project aside for awhile. When much later she returned to the novel, the “spirit” of the idea had abandoned her; she was unable to capture the thrill that had been present in the beginning; it was understandable, she says, because she had violated her contract with the idea.

Years later she met and befriended a famous writer. One day, as they were talking, the famous writer revealed she was working on a novel that was strikingly similar to the idea Gilbert had been forced to abandon. Gilbert takes this as unmistakable evidence of what she calls “big magic.” There were far too many similarities, Gilbert claims, for them to have been a coincidence. Gilbert concludes that her great idea must have “moved on” to her writer friend, and Gilbert believes the idea must have been transmitted through a kiss she had given her friend at one time. She concludes the anecdote with the words, “And that, my friends, is Big Magic.”

Never before have I encountered such a bizarre interpretation of the creative process as being “magical.” Julia Cameron, author of The Artist’s Way, also embraces magical ideas, such as the idea of “synchronicity,” meaning that when you begin to create art, the mystical forces of “the universe” will go out of their way to assist you. However, compared to Gilbert, Julia Cameron seems like a poster child for rationalism; Cameron does not make magic her central thesis, and she got the idea of synchronicity from Carl Jung; she did not just make up random things and believe them.

Gilbert has many beliefs. Aside from believing that creative ideas originate from a divine source, she believes that whenever you take on a big idea and promise it that you will see it through, spirits will labor alongside you to help you reach completion.

Gilbert argues that viewing creative ideas as originating from an external reservoir is good for writers because it helps them stay humble; that is, an artist has no business taking credit for his work if it turns out great, but on the flip side, he can blame his failures not on himself, but on the universe.

To reinforce this viewpoint, she discusses how artists of ancient Greece, when their work was going amazingly well, would give credit to a spirit guardian they called a “genius.” In other words, artist did not see themselves as geniuses, but gave credit to invisible helpers they called “geniuses.” Gilbert laments that in modern language the word “genius” now describes a human and not an invisible helper that breathes inspiration into the artist. She says that, as a result of people being geniuses rather than having them, all the weight of creative responsibility now falls onto the poor artist, creating stress and unhappiness.

Under the “genius partner” view of creativity, not only does the artist avoid the crime of “narcissism”; if the art goes awry, the artist can simply say, “Hey, don’t look at me – my genius didn’t show up today!” (Her words)

As for me, I would much rather take responsibility for both my successes and my failures than to give credit for my hard work to fairies.

But back to Gilbert; other than her anecdote about her conversation with the famous writer, Gilbert makes no effort to offer any evidence for her outlandish claims or to explain the strange contradictions that arise from them.

While she writes that ideas emerge from a divine external reservoir, she also states that “hidden gems” lie buried within each and every writer, and it is the job of every writer to dig them up and share them with the world. Gilbert never explains how to tell the difference between an idea that comes from within versus the kind that come from without.

Neither does she address the full implications of her claims. Do creative ideas that contradict each other come from the same divine source? Does her book and my blog post criticizing her book originate from the same place? Did The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe emerge from the same spiritual reservoir as Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler?

Gilbert does answer one question, which is, what do you do if the spirits fail to show? She says the only option is “unglamorous disciplined labor.” But for me writing does not feel laborious because I love writing enough that discipline is not required. Gilbert is describing kind of self-coercion that used to make my writing far more miserable than it had to be.

On a side note, I wonder why spirits would abandon an artist in the first place if they are so committed to seeing creative ideas realized. Do they get tired? Do they need to go grocery shopping? Gilbert says she does not know why on some days she and other writers have trouble writing anything and on other days they are creatively stoked. She says she is content to view the problem as one of the great enigmas of the universe which defy her comprehension.

While Gilbert has no problem with claiming certainty about spirit helpers and ideas that make “contracts,” she does not mind confessing uncertainty about the writing process.

The irony is that questions about the writing process have discoverable answers. The question “Why do I have slow writing days?” is not on the same level as asking “What happened before the Big Bang?” When I was suffering from a severe case of block, I finally discovered that whenever I had lethargic or painful writing days, it was usually due to punishing self-criticism, self-coercion, under-confidence, and flaws in my process.

When I learned to stop expecting the rough draft to be “good” and divided the process into distinct stages, I stopped getting “stuck” because I always knew what the next step was. Learning to suspend my self-criticism during my rough drafts freed me to concentrate fully on what I was doing. The answers of other writers might not be the same as my answers, but the question of why individual writers have “dry” writing days is hardly a great enigma of the universe. It is answerable.

Turning answerable questions into cosmic mysteries is no better for writers than claiming to have spirit companions that do their work for them. But is there any real harm of calling writing magic? Aside from it being untrue, focusing on magic helpers diverts attention away from the practical and truly effective ways of approaching creative projects.

There are many non-magical ways to reignite inspiration and get the words moving again. What helps me more than anything is a mind-mapping technique called clustering, described by Gabriele Rico in the book Writing the Natural Way. Whenever I feel stuck, I stop writing and create a mind map. It works every time.

Contrary to what Gilbert believes, postulating magical entities that make art for us is not helpful but disempowering. It makes writers dependent on mysterious and uncontrollable forces, when everything we need to create is within us.

While I do not believe spirits dictate my novels to me, I do concede that at times, writing feels magical. Creativity inspires feelings of awe and wonder; transforms the flotsam of daily life into meaningful patterns; weaves beauty from pain; lets me create something for no other reason than I want to see it exist. The exhilaration that comes with all that feels magical.

But writing is not magic. Creativity does not require the physical laws of the universe to be overturned. It does not require spirit laborers to cheer me along or dictate divine messages. But even without invoking magic, creativity it is still beautiful, powerful, awesome, and often euphoric.

However, my creativity comes from within me. Brains are adequate for explaining ideas. And if I ever write a masterpiece, I am damn well going to take credit for it, no matter what the ancient Greeks believed. Unless of course, I see a Minotaur, a satyr, or a wood nymph frolicking outside my window. No, scratch that. Even if Zeus himself shows up at my front door bearing a goblet of ambrosia from Mount Olympus, his visit will change nothing; I am still signing my name to my novels, not the name of my “spirit guardian.”

I am narcissistic, that way.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my new novel “The Ghosts of Chimera” will soon be published by the folks over at Rooster and Pig Publishing.

The post Is Writing Magic? appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

February 25, 2016

“The Toppling Tap” (A Poem About Over-reacting)

I wrote the following poem on a day when some absurdly minor mishap propelled my mood into a downward spiral. My poem did what writing often does: it made me feel better. I want to share it.

I live in fear of the toppling tap

The nudge that sends me reeling

The paper clip that flattens me

The crushing force of feeling

I long to be free of a tyrant brain

That scalds me with emotion

For a slight, a sneeze, or a sidelong glance

Or some deluded notion

Someday I will go to a quiet place

Where I am free from feeling

A place where thoughts are safe as rain

And maybe just as healing

In that rare state

I will see

An unfiltered reality

Unclouded by my wants and fears

Unbent by my prismatic tears

A tap will only be a touch

And nudges will not hurt so much

Paper clips will bind reports

Where tyrant brains must go through courts

I will finally have my way

When reeling is done just for play

When crushing forces barely kiss

As I go toppling into bliss

The post “The Toppling Tap” (A Poem About Over-reacting) appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

February 18, 2016

The Mind Thief (Short Story)

Stamps bored him, and butterflies were too hard to catch, but inventor Maxwell J. Peabody was an avid collector of oddities, and of all he had collected, nothing ever truly satisfied him until he began collecting human minds.

He would leave world-ruling to other “mad scientists,” the lazy, ferret-stroking, cackling geriatrics who needed armies to feel good about themselves; perhaps Maxwell would dabble in world domination when he retired from his true calling: penetrating the individual human psyche.

To study it Maxwell was highly selective about the minds he captured for study, vetting subjects for their intelligence, creativity, and emotional insecurity. He preserved his minds in a sky-lit museum-like room on the topmost floor of his five story mountain home which seemed to absorb, rather than repel, the cold from the snow-swept grounds outside.

He had filled his “mind room” with carefully labeled glass cases where he kept remnants of his old collections, including his extinct beetle fossils, moon rocks, and octopus eyeballs, but most of his private museum contained minds now, each one confined to a glowing elevated round stand resembling a dinner plate.

Maxwell could see them, ghost-like human figures smiling adoringly at him from their circular stands as he passed. Others sat hunched and rocking back and forth, their knees bent upward, their interlocked hands cuffing their ankles, but he could see veiled pain in all of their eyes, even as they smiled at him.

Maxwell had made the minds visible with “Blue MINK,” a self-concocted metaphysical ink he had sprayed on the minds to reveal ghosted versions of themselves which he called “mind shadows.” Mind shadows were wispily transparent, and each was surrounded by a wavering blue outline. As ghosts were reputed to sometimes do, mind shadows could move small objects for short periods of time due to the energizing quality of the MINK, but mostly the “shadows” were just images.

However, instead of looking as they did in real life, his subjects looked the way they saw themselves. A skinny person could manifest as being fat, for example, and an elderly person could look twenty.

How the mind shadows looked changed for better or worse depending on how they saw themselves on any particular day. To his infinite delight, Maxwell could influence this change, and watching the daily flux of their appearance could be more mesmerizing than gazing at a lava lamp while stoned.

Right after entrapping his minds with his extraordinary invention, the Mind Extraction Machine, Maxwell set about conditioning his subjects to adore him, because where was the fun of being a mad scientist if you could not have your test subjects worship you as a god? And what better way to do that than by controlling minds?

Of course, minds did depend on brains – one reason Maxwell made sure not to kill the bodies upon mind extraction. Rather, he sought to preserve the metaphysical threads that united their minds with their bodies. The farther away from their bodies he pulled their minds, the thinner the thread linking them became, and the less communication got through. The mind shadows shifted into an almost perpetual dream state, processing any new stimuli sent from their bodies as vague and not quite real.

The extraction was not total. Maxwell left enough auto-control in their bodies for them to do what was needed for self-maintenance, like driving, eating, paying bills, and going to their slavish dead-end jobs. But their dreams, their secret hopes, and their imaginations, he took for himself to mold according to his liking.

Validation seekers were the best candidates. To “capture” minds he baited sleeping subjects with compliments so honeyed that they came to his Mind Extraction cage of their own free will.

Thus, once possessed and confined in the museum, his mind shadows did not even need bars on their “cages,” as long as he fed them enough compliments, peppering in a little criticism here and there, so that the praise would not lose its power.

The mind shadows were toys to Maxwell, and he played with them as a child plays with dolls. Maxwell particularly enjoyed getting his subjects to change their careers, the aspect of their lives that consumed most of their time and attention.

He convinced some subjects to give up magnificent careers as singers to become accountants, and he persuaded accountants who loved their work to overthrow their careers for minimum wage jobs stacking grocery shelves or manufacturing styrofoam peanuts.

Sometimes he went into the city and followed the physical bodies of his subjects around to make sure the mind-to-body command link was working properly. He observed them as they ate lunch or went from their cars to their jobs, until he was satisfied that the “robot” bodies were obeying the orders he had given his mind shadows.

Of course, Maxwell did not give a damn what his subjects did for a living. He Just liked being the puppeteer who pulled the strings of his subjects so that they believed they were acting freely.

He was making outstanding progress with an 18 year old girl named Christine. When captured she had already been proficient enough as a painter to make a living at it, but he had more than half convinced her she was far more suited for a job cutting and styling hair.

She was insecure and craved approval more than anything, especially his approval, and her craving for affection shaped her mind shadow.

Like her real body, her shadow self had clear ivory skin and long blond hair, but there was a big difference; she looked dreadfully cold. Overall her skin had an anemic bluish pallor, except on her face where some chapping appeared as red blotches. Ice cycles had frozen parts of her hair into clumps. Her lips were the palest pink, and her elbows appeared sheathed in ice. What appeared to be frozen tears glimmered on her cheeks. There was lively warmth only in her eyes.

At least there had been at one time. Even her eyes were losing their life-like glimmer now. Her mind shadow was losing its personality, and soon it would become a dull and empty vessel just like her robotic real body. It was a shame that he would be forced to abandon her as he had his other exhausted experiments.

Controlling his subjects was both good and bad. The price of success for which Maxwell sometimes felt regretful was that it meant turning once vibrant and spontaneous creatures into tedious drones whose admiration was hardly worth having. After a while of being with Maxwell, his subjects became as predictable as the seasons, and just as jejune.

Christine was hurrying down that path until one day, when he thought she was fully under his power she began to act unpredictably. There were few things Maxwell hated more than unpredictability.

An alarm actually wailed from his computer, and Maxwell rushed to it to see what was wrong. He kept the computer in his museum to monitor the thoughts of his subjects, especially their thoughts about him. He made sure his subjects would always see a handsome photograph of his face every day along with the messages he sent them, and his computer would reveal how his image appeared when filtered through the eyes of his admirers; according to his plan, he had been elevated by his subjects, enlarged, haloed in light, and imbued with a divinely mysterious aura.

But when he came to Christine, he saw himself as a silhouette, a hazy shadow that kept blinking on and off. What did it mean? He checked her verbal thoughts, and sure enough, they confirmed his fears. “Where am I? Why can I not escape this damned circle?” Maxwell hurried to the circular elevated “cage” to get a closer look at the mind shadow in distress.

Christine was looking around the “museum” as if trying to get her bearings. All at once she closed her eyes tight, as if the sight were too much for her. After taking a deep breath, she went so still she looked like a mid-eastern guru, on her knees, her posture perfectly erect, and her movements perfectly controlled. She reached her slender, frost-bitten fingers toward the invisible outer circle of her cage, and seemed surprised when she could only reach them so far, considering no barrier was visible. She blinked several times and tried again.

Appearing to sense Maxwell looking at her, she turned a direct blue gaze on him.

Maxwell tensed. It was not unusual for subjects to look around, but they rarely did so with real curiosity. And while they sometimes gave him vague, adoring smiles, none of them had ever studied him like the girl was doing. Her blue-grey eyes appeared to scan every contour of his face. She seemed disarmingly…aware.

His heart accelerated as she looked straight at him. “Where am I?” she asked him, “and who are you? And what is this? She held up the hairstyling magazine called “Snipping Beauty” that he had left in her “cage” in an almost flat, gift-wrapped box with a spiraling red velvet ribbon on top.

Maxwell, a man of few words, was again taken off guard. To speak to one of his belongings, to reward it for questioning him seemed beneath his dignity. The rest of his subjects had regarded him as most behold a creature in a dream; they tended to be bleary-eyed and adoring, nothing more. Maxwell made a mental note to record the aberration of Christine in his experimentation log; he was nothing if not conscientious about his work.

Before he could get away, the girl repeated her question, “Where am I?” At first, the question came out as a whisper. Then she said it again, more insistently, her voice rising toward a frantic pitch, “Where am I?” She glanced at the last compliment message Maxwell had written on the text mirror and read it aloud, “I applaud your unselfish efforts to lend your artistic talents to the endlessly fascinating world of hairdressing.” She regarded the message with an expression of dismay.

The text mirror was one of four mirrors Maxwell had placed around Christine as he had with each of his other subjects. They were more than mirrors; they also served as monitors. One mirror displayed the compliments or criticisms Maxwell sent to subjects through his computer. Another showed videos extolling the careers he had chosen for his subjects, only instead of seeing real employees carrying out the jobs, his subjects saw themselves performing them with expressions of extreme bliss on their faces. Another mirror, their “dream mirror,” displayed their deepest wishes and most fanciful imaginings; it reflected their true longings, personalities, and aspirations.

For Maxwell the game was to get the control mirror and the dream mirror to match; for Christine that meant replacing her fantasies of being a painter with those of cutting hair. The final mirror contained an enlarged image of him, Maxwell, looking the way his subjects saw him at any particular moment, ideally haloed in divine light.

Maxwell decided to talk to the girl, lest his messages lose their power over her. Honesty, deliberately applied, could be powerful at times, he had noticed. “My name is Maxwell J. Peabody, and I am your god. You are part of my collection,” he said, “a fact that should make you most proud. I do not collect just anyone, you see, only interesting people with interesting dreams.”

“A collection?” Her voice sounded baffled, but he could tell his compliments had affected her, if only a little, by the way a blush touched the tops of her cheeks. However, it faded quickly. “Why do I feel so…disconnected? The compliments,” she looked around, “every day, so many compliments. I loved them at first, they felt good…they felt warm. But now…I wonder why I never asked why there were so many. I see other people here, yet I feel isolated.” Frantically she looked around. “I remember I used to have a room with an easel with a palette full of oil paints. And brushes. Where did they all go?” She looked down at her circular platform and drew in a sharp gasp. “And how did I get here…on this big cake plate? Oh my God, am I an object in a museum? Is this a dream?”

Maxwell did not respond. It was obviously time to “reline” her cage with praise the way you might reline a parakeet cage. Maxwell hurried to his main computer in the center of the room. The kind of awareness the girl was expressing must have been due to a fluke or a glitch.

He drew out his dossier on her, the one he had compiled when he was doing research on her to determine her viability as a subject. She had come from a household dominated by abusive parents. The had employed an unusual form of punishment; whenever she had “misbehaved,” they had locked her outside their house to suffer in the brutally cold wind and snow where her toes and fingers had gone numb.

Where she had lived, it was almost always cold, white blanketing the ground, fir trees, and rooftops. She had gone through her life obsessively collecting warm items, symbolic and literal: space heaters, quilts, cats, teddy bears, and varieties of hot chocolate. As for getting back into the house as a child, her parents had always given her an unjust condition: Christine was forced to make a self-degrading apology, even when she had done nothing wrong.

She had tried to rebuild her self-esteem by being a good artist, a painter. She had spent every free moment painting and there was nothing she liked better than praise for her work.

In doing research Maxwell had collected a few of her paintings and hung them on his office wall: leafy mountain landscapes with moons too large to be real, portraits of children with troubled eyes, and ferocious animals that appeared to be charging toward the viewer. One of her paintings was particularly striking: a baby bundled in a pink blanket lying alone on a twilit snow-swept landscape.

Her most recent paintings were the best because two years ago, she had endured the death of her younger brother, the only person she had loved and been close to. Her suffering during that period had brought her artistic talents to a peak, and her paintings had begun, modestly, to sell, presaging a vibrant career.

She had appeared to be a worthy acquisition; he liked his subjects to be dreamers, after all.

He pattered out a bunch of fresh compliments on his keyboard. “You have a flawless sense of design, Christine, and an imagination bigger than the universe.” He smiled at his hyperbole, “qualities that would delight any customer seeking to improve the appearance of their hair.” He smiled and typed out the coup de grace designed to hammer her into full compliance. “While certainly creative. your paintings nevertheless reveal a lack of emotional depth; therefore, applying your creativity toward becoming a professional painter would be selfish folly at best. Let roller brushes be your paintbrushes, Christine. Let hair dye be your paints. Make the world more beautiful, one person at a time. Be a hairdresser, Christine, and my favor will be eternally yours.”

But the girl was not looking at his messages; she was sitting on the heels of her white sneakers, knees still bent, stretching her arms, trying to straighten them on either side, toward the invisible edges of the “cage,” testing, observing, studying, and perhaps wondering, if the cage was so uncomfortable, why she was still there.

When she glimpsed the march of new messages, she turned, flinching, toward the mirror displaying them. Wide-eyed, she read them aloud. At one point a slight smile touched her lips. Maxwell could tell by her sudden pallor when her gaze landed on the critical remarks at the end.

Maxwell expected to see her attractiveness fade when she saw the last message. Instead she frowned thoughtfully, bit her lip, and turned her head to look directly at Maxwell. “Operant conditioning,” she murmured. “Operant and classical.”

Her response surprised him. “Excuse me?”

“These messages, they come to me every day. I expect them. I hope for them. I thought they meant something, but now I know: To you I am neither an artist nor a hair dresser, but Pavlov’s dog. How long have you been training me to drool at the sound of your bell? You do resemble him, you know. Pavlov. Are you him, reincarnated? Or a zombie version, risen from the dead?”

“Pavlov? No, my name is…”

“B.F. Skinner? Another big conditioning maven. I learned about him in my tenth grade psychology class. He was a psychologist who experimented with operant conditioning, manipulating animal behavior through rewards and punishment. To control someone, intermittent rewards mixed with punishment are far more effective than rewards alone, especially when neither are predictable. You applied his insights perfectly. On me. Using praise as bribes, you pushed me to study hair dressing, an occupation I would never have considered by myself. You gave me generous rewards at first only to later withhold them in order to punish me. Your praise sends me soaring, but you have to criticize and punish me, too, so I will struggle hard to please you. Your game is like a Vegas slot machine; one I will never win.”

Maxwell felt the muscles in his jaw ache with tension. “Now, Christine, what astounding accusations. Do you hear yourself? You are overthinking. I am your friend.”

Christine looked at him as she were regarding a mythical sea monster. “Before, whenever I would see you pass me beneath the sky light, your face shadowed by your cowl, my heart would beat faster. I took it all so seriously, but all along, you were just conditioning me. Who are you? Why am I here? And why do you, a scientist, care if I cut hair?”

Frantic, Maxwell returned to his computer keyboard and pattered out more praise to be displayed on the monitors but when he glanced at Christine, she seemed oblivious to him. She raised her arms again, slowly, by her sides, a human bird testing outstretched wings, trying to straighten them fully as she lifted them, unbending her elbows, struggling to move her arms past the invisible wall, and looking perplexed when she found her hands still blocked.

“Why is it so hard,” She spoke with deep despair, “when there is nothing here to hold me? That is the question I keep asking myself, the question that woke me up: Why am I still here when it hurts to stay, why can I not just leave? And now I know. The praise gives the illusion of warmth.” She dropped her arms, then made a fist with her right hand, and struck out against the invisible barrier. Her fist could not penetrate the wall. She dropped her arms and stared at Maxwell in total confusion, tears clinging to her eyelashes.

Looking at her, Maxwell felt a great measure of relief. It was wonderful; she had guessed what he was doing, yet still found it difficult to escape the compliment trap he had woven since the day he had collected her. He was more powerful than he knew.

She squirmed in her small, cramped circular space. Her virtual hair was messed up, she looked disheveled in her jeans and wrinkled Van Gogh “Starry Night” t-shirt. Yesterday she had been wearing a black hair styling smock. What had happened? “Was none of it real?” she asked. “Everything you said about my flawless sense of design? Was it all a lie to keep me here, inside your circle, or web, or cage, or whatever this is? To make me cut hair, just because you said so?”

Despite his reluctance to lower himself by engaging in conversation with a test subject, Maxwell was curious enough to ask a question. “If you think I am trying to hurt you, why do you stay?”

She had a faraway look. “I only wish I knew. Why do I stay? This cage is cramped. I feel lonely. And so cold. For months now, the highlight of my day has been your messages, especially at first when they were all praise, but then the criticism came, and then the silence. I have been confused ever since. But with all of that, it is hard for me to leave.”

The mad scientist enjoyed an electrical surge of hope. She was still his. Even knowing everything, she would continue striving to please him for the single ray of warmth his praise represented. He had known his methods of control were effective, but not nearly as effective as they were. He could not wait until she began her hair dressing career; he would take photographs of her cutting hair and post them on the walls of his trophy room.

The girl continued to press her pale palm against the invisible wall. “All my life,” she said, “I wanted to be liked. As a kid, my parents were always telling me I would either grow up to be a homeless bag lady or a criminal, just a loser of some sort. More than anything I craved their approval. And when I came here, you gave me what I had always wanted, for a little while, the warmth, the validation. But then the criticism began, with the little bits of praise stirred in like croutons in a salad, and I stopped having fun. I want to leave now.” She looked into his eyes. “Why can I not leave?”

Maxwell could not help but grin. How much more satisfying to be admired by a thinking person, someone who knew he was controlling them, yet still stayed. “You will remain with me. Like you said, where else will you go? The warmth you sensed was no illusion, Christine. I do treasure you. You are perhaps the most interesting object I possess, although I only just realized it. To question me, yet still remain. You have the ability to fight and defy me, yet still you submit. I have to say, I like it.”

She looked at him with tortured confusion. “Some part of me keeps saying, stay here, what is the matter with styling hair if it makes Maxwell beam at me? I forget to ask the question that really matters: Why do you want me to style hair? What difference could it possibly make to you? What is wrong with me?” She shook her head vigorously, as if trying to dislodge a leaf from her icy hair.

“Nothing is wrong with you, Christine. Quite the contrary: You are my favorite possession. At the moment, of course.” He decided to push his luck with honesty since it had been so rewarding the first time. “That does not mean you will never be replaced as my favorite. You see, I am easily bored. If you defy me, you will be punished beyond what you can imagine, but the more I control you, the more you obey me, the less interested in you I will become. Eventually your eyes will go dull and your movements will turn sluggish. You will lose every quality that made you interesting to me. You will become a lifeless shell, if that.” He looked at her with pain in his eyes, as if he expected sympathy. “Such is the trial of my existence, that all good things must pass, in time. You may enjoy my full attention for now, for as long as your dreams continue to interest me, and for as long as you are able to obey me without boring me too much.”

Christine glared at him.

“Now, now, stop that,” Maxwell went on. “Even after I drain you of your innermost essence, I may still allow you to serve as my top minion. My other assistant, Mongrel Jim, is loyal to a fault but, I must confess, he is not the brightest light in the sky. Some tasks require more…finesse…than he is able to offer. Even with your innermost essence drained, you are likely to make more intelligent decisions than he.”

She shot a burning glare at him. “Staying here with you is wrong. Your warmth is fake. I want to be…independent.” The last word may have meant to come out as a call of defiance, but it tapered into something more like a mewl. “All the time I tried to please my parents, I knew better. Even when I was little and they locked me out of the house, in the cold, I tried to deny the truth: that they were far colder than any snow, sleet, or wind could ever be. I should have braved the physical cold, I should have escaped, for even the slightest shred of hope of finding a place with people who had real pulses.”

“When I turned thirteen, I knew I needed to move on, to stop seeking hugs from ice burgs, and to make my own decisions without apologizing or asking their permission.”

“I am not denying you independence, Christine,” Maxwell said. “It is fully within your grasp. You should be able to support yourself nicely once you become a proficient hair dresser. Stand on your own, as it were.”

She glared at him. “I do not want to become a hair dresser, nor your minion, and if you begin draining me of anything, particularly my essence, I will bite your hand.”

“Oh please Christine. Be realistic. Your last couple of paintings were no better than the scrawling of a child. Do be practical. Grandiosity does not become you.”

“Grandiosity? Me?” She scalded him with her glare. “You called yourself a god.” She wrinkled her forehead thoughtfully and said, “Your compliments seduced me into adoring you. but all along, your praise was just a handle for you to swing me by. Nothing more. I feel so stupid.”

“Oh, come, Christine. Do you honestly think…?”

“I need to throw it all away, all of the fluff, all the denial, all of the delusion, I need to let it all go, and if I die, at least I will die as myself, as an artist, not a hair dresser, not your pawn, not your minion, and certainly not your worshipful devotee.”

She knocked one of the rectangular mirrors from its metal stand. With her opposite hand, she struck down another. She hit the one in front of her so hard, it went flying off the circular stand and shattered on the floor. She turned around and swept the one behind her from the platform, until all four mirrors had fallen, including one with a video of herself smiling radiantly as she snipped the white locks from an elderly woman. But once the mirrors were all lying flat, Christine looked not victorious, but deeply sad.

“Ha! I knew it!” Maxwell said. “You worship me. You will never leave,” Maxwell said. “What are you planning to do? Go back to your old life trying to please your thankless parents?”

“I don’t know,” she said, “but I’ve lost something, Maxwell J. Pavlov. And I need to find it.”

“Oh please, Christine, cut the puerile antics. Call me by my real name and give up chasing unicorns. Leave me and you will be going back to a life full of loneliness and insecurity. Stay here, I can protect you from the winds of life, the unbearable chill of reality. I can liberate you from having to make choices. I know you. I know what is best for you. Do you have any idea how high my I.Q. Is?”

Christine said. “I want freedom.”

“Making decisions is not freedom, Christine; it is a terrible burden and the biggest source of anxiety there is. I know you are upset but I am not the enemy. Life is the enemy. Uncertainty is the enemy. I am your helper. Besides,” he made his eyes as sincere as he could, “it is lonely being superior to everyone else, and I have taken a fancy to you. I like you Christine. Perhaps I even need you.”

“Ha! You need me? Sorry. You will have to cut your own hair. Or get Mongrel Jim to do it.” With renewed determination, Christine had begun reaching her right arm out again, again and again. She sent a defiant glare toward Maxwell as her hand at last slipped past one of the fallen mirrors and shot through the invisible barrier. Maxwell tensed in alarm as she tried with her other arm, which also went through. Christine turned in her circle, unfolded her legs, swung them around, then stepped onto the checkered museum floor. “I am going to leave you now, Maxwell. I want my body back.”

“Your body?” Maxwell sighed wearily. “I am terribly disappointed in you Christine. So shallow. It is your mind and your personality that matter. They are why I like you, why you should like yourself. Besides, you said you adored me. Worshiped me.” Maxwell grinned.

Christine crossed the floor of the room to the iron door on the back wall made of wide, chunky grey stones. She tried grabbing the brass door knob before realizing that her non-corporeal self was too weak to move it. For a moment she appeared perplexed, but then she took a step back from the door and fixed a solid gaze on it.

In its center, a swirling vortex appeared as the mouth of a tunnel which allowed a view to the world outside the door. A powerful wind gusted into the room, tossing in a wild flurry of snow and sleet. With a gasp she stumbled backward, but she did not fall. The wind at surface level roared and the wind far above made high, plaintive whistles in the soaring white-capped cedar trees.

“There, Christine, see? The weather on this mountain is terrible. Darkness is falling. Are you not afraid?”

With wide, child-like eyes, Christine looked at him. “Scared, yes,” She turned her head and focused on the stormy drama outside. Slowly, she reached a hand beyond the opening, seeming to test the impact of wind and snow on her. Then, relaxing, she released a slow, tremulous breath. “My brother used to try to comfort me whenever I felt sad in our drafty old house. He would say, there is beauty beyond these walls, Christine, warmth beyond the snow, and I think he was right. If I can just move through the snow storm and let it do its worst, another world is waiting for me on the other side, a place with real warmth, and not just the light of illusion.” She took a step toward the spinning window.

Maxwell felt an odd sensation grip his chest; panic? He could not lose his possession as soon as he had come to value it, not like this. Surely there was a way to stop her, but all his gratification rested upon his acquisitions choosing to stay. Maxwell was not one to employ violence; using force seemed so…rude, so crass, so beneath him. Quickly he crossed the room and stepped in front of her. “Stop, Christine. You adore me. You said so yourself.”

She stared at Maxwell. “Adore you? If any part of me does, it’s not why you think. All my life I have sought approval, and all my life I have tried to change the empty place inside me that craves it. Wanting my parents to love me gave them power to hurt me. More than anything, I wanted not to care. But you have shown me, as no one else ever could, that praise means nothing, except to those who weave it into webs. By imprisoning me with my own vice, you have set me free.”

Christine tried to go around him but he side-stepped in front of her. She tried again, but once more he blocked her. Finally, she locked eyes with him, stepped toward him, and walked right through him. As she passed through Maxwell, he felt an odd sensation like a breeze, a blending of warm and cold, a mixture of yearning, fear, anger, and defiance.

Before he could react, he heard her say, “Goodbye Maxwell J. Pavlov.” Abruptly he turned to see her translucent back receding from him. The wind roared through the circular window as she took a homeward step beyond its threshold, at first tentative, and then another, more certain step, into the icy, vast unknown.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my new novel “The Ghosts of Chimera” will soon be published by the folks over at Rooster and Pig Publishing.

The post The Mind Thief (Short Story) appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

February 10, 2016

Writing Fictional Characters from the Inside

If you read much advice on writing fiction, you will at some point encounter questionnaires meant to help you build your characters. Questions about characters include: “What are their specific gestures? How did their culture impact them? If they had a day to themselves, what would they do?”

For many years those kinds of questionnaires both thrilled and frustrated me. I would begin them with so much excitement until I realized I could not get a full sense of who my characters were by simply writing out a list of traits. I would always write the first answer that came into my head, and the first answer was always obvious, trite, and dull.

What does Lucy do if she has a day all to herself? She watches television, she goes shopping, she talks on the phone. All of these answers are logical, but they are generic and boring; they could apply to almost anyone. They do not give me the sense of who Lucy is as a complex, unique, rounded-out individual. Answering character questions in the mechanical way you would fill out a medical form is a waste of time.

Is there a better way to approach character-building questionnaires? Yes. And what helps me more than anything is to take the preliminary step of writing a short point-of-view sketch.

I think about point-of-view sketches as “pretend you are a flea” assignments.

When I was in the sixth grade my teacher used to give the class point of view creative writing assignments such as “write a story from the perspective of a flea.” The exercise sprang me from my desk chair, flung me onto a dog, and sent me crawling through a dense forest of towering fur, searching for the tenderest spot of canine skin to quench my insatiable thirst for blood.

I rarely write from the point of view of fleas anymore, but the technique works just as well with human characters.

Point of view sketches are more important than questionnaires because they allow me to grasp my character from the inside and not just from the outside.

For my point of view sketches, I pick a situation, usually one I have imagined happening in my novel, drop my new character into it, and write what she sees, hears, thinks, and feels. For the sketch to work, I have to know a little bit about my character but not much. Is she a child, a school teacher, a sociopath? I start with what I “know” and after a few moments of writing, a mental shift will occur. If I put my character into a situation and have her think about it, react to it, and feel it, she is more likely to “come to life” than if I reduce her to a sterile list of questionnaire traits.

After doing my point of view study, I am ready to use my character-building questionnaire to add developmental layers to a character that now has the first hopeful murmurings of a heartbeat.

The questions encourage me to think about aspects of character I have not explored in my sketch, but I have to remember not to approach the questionnaire as I would a medical form. In fiction there are no “right” answers and closing in on a single solution too quickly suffocates creativity.

Planning fictional characters should not be rushed; it should be as creative, divergent, and fun as the actual writing. Besides, if I have done my point of view sketch before beginning to fill in my questionnaire, I am likely to find that many of the questions are already answered.

For any unanswered questions, I try to avoid writing the first answer that comes to mind, which is likely to be sensible but mind-numbingly boring. That is why I use a mind-mapping technique called clustering, which turns answering the questions into a fun and creative game rather than a dull chore.

To cluster, you start with a central idea or nucleus, which can be a question such as, “What would your character do if she had a full day to herself?” You circle the question as your nucleus and draw lines radiating from the center, free-associating as many possible answers as you can think of: “goes shopping,” “reads voraciously,” “bakes cookies.” In clustering, you can circle any of your free-associated ideas as a new center and shoot lines from it to even newer associations. “Goes shopping” might lead to the association “shop-lifting.” “Reads voraciously might lead to the contrasting idea “reads shallowly.”

After a few minutes you will have a radial web containing ideas that intrigue you. When an idea interests you, you will feel an inspirational tug. Go back to the original question: What would your character do if she had a full day to herself?

A sample of the kind of boring generic answer I usually end up when I neglect to cluster is: She watches television, she eats three meals, she talks on the phone.

But clustering allows me to choose what most interests me from multiple possibilities. For example, if I am drawn to the phrase “reads shallowly,” I might write: She would drag a stack of hardbacks off her book shelf, haul them to the living room, and plop down on the sofa; she would open a random book, scan the first few paragraphs, and stop. Then she would close the book, set it aside, and with a sad smile take up another book, always reading the first few paragraphs and always closing the book after the first page.

Better. And certainly not what most people would do with a day off. Lucy is still confusing at this point but she is starting to seem like an individual. And she is beginning to intrigue; what is up with her not continuing to read her novels beyond page one?

If I have written a point of view sketch before answering form questions, I might already know. I might add, Lucy liked the beginnings of things best. Middles and endings, she had too often learned, were bound to disappoint. Lucy unfolds even more when you add an unusual point of view to her actions, which brings up enticing questions. What trauma has caused Lucy to view middles and endings with suspicion?

While answering form questions about characters can be fun and useful, if I had to choose between questionnaires and point of view exercises, I would always choose the point of view sketches.

Character-building questionnaires invite the writer to view characters from the outside. We “see” how the character looks and acts as if we were watching television. Knowing a character from the outside does matter, but for a character to act in a way that make sense intuitively, I need to know what she is thinking or feeling.

If I skip the point-of-view step and try to write a character in third person, something usually seems “off” about their behavior, but once I get inside the head of my character, everything changes.

Admittedly, writing from the inside is not the only way to “know” characters. Observing real life models for inspiration is invaluable. Not everyone is like me or thinks the way I do. As a writer I am constantly striving to stretch myself as far as I can beyond the narrow confines of my skull in order to understand those who are different from me.

In real life I might fail. No matter how much I try to empathize, I am not a mind reader. I may reach beyond myself as far as I can, but ultimately I can only understand others in terms of my personal frames of reference. Fortunately, writing is not about mind reading; it is about using what I do know as a “jumping off point” to create.

The “pretend you are a flea” exercise drives me to reach toward the world outside myself, and the ambition to cross the barrier separating me from a different person or species dislodges familiar ways of thinking and inspires.

Will I actually ever fully understand what it is like to be a flea or, for that matter, another person? Probably not. But I can imagine.

And imagining can take me farther and higher than a flea can jump; farther, in fact. Much farther.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my new novel “The Ghosts of Chimera” will soon be published by the folks over at Rooster and Pig Publishing.

The post Writing Fictional Characters from the Inside appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

February 3, 2016

Am I My Blog?

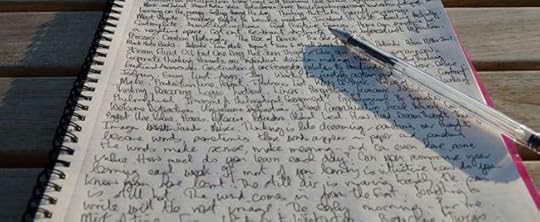

The world of writing is where my mind lives even when I am away from home. In a grocery store, when my companion wonders why I have a faraway look in my eyes or why am being so quiet, the answer is simple: I am writing. And in many cases, what that specifically means is, I am blogging.

My blog has become such an intrinsic part of my life, I have trouble imagining being without it. But not all my experiences have been pleasant. Readership-wise, my blog has had many ups and downs, like the time I was thrown off Reddit and my blog views plummeted. But I always kept writing. I loved coming up with something new to say each week.

When last week I was told I had lost my blog, all of my blog, due to a failed monthly payment, I had a feeling I had been down that path before, building my blog up, losing it, and then starting from scratch. Looks like it is time to begin again. Again.

As it turned out, I was able to get my entire blog back, but when I thought I had lost it and my followers, an interesting thought process began. What had I really lost? It felt like I had lost part of myself, but had I?

I am not my blog and my blog is not my writing. If my blog went away, I could still write, although my mind would not be able to go to Blog World anymore when I am grocery shopping; most likely my only retreat would be the fictional worlds of my novels, which sometimes take a backseat to my blog.

But I would really miss blogging if I stopped. Though my blog has made no money, I have enjoyed other kinds of rewards; knowing others would be reading what I wrote has driven me to become a better writer, and I have enjoyed all the writing I have done. Besides, I believe that posting my stories on Twitter led to my book publisher inviting me to submit my novel manuscript, which led to my book deal.

But I keep going back to the question: What if I really had lost my blog for good, and how much have I come to identify myself with it? I have always been fascinated about what lies at the core of people, including myself, when the things that they use to prop up their egos goes away, because I think that is where the truth of a person lies. How strong is my sense of self?

Ever since I have been writing my blog, I have struggled to vanquish the part of me that craves approval because I know it is my greatest weakness. I often wonder where it comes from, and why it is so hard to expunge from my emotional programming. Maybe it was spawned in the sixth grade, the year I was bullied relentlessly and validation was scarce.

In high school I rebuilt my shattered self-esteem by studying hard and making good grades. Making an A in every class was validation I could control. No matter how challenging a subject was, I knew that if I read my assignments and learned the material I would get accolades from teachers. To me an A on a biology exam meant “You are worthy.”

However, I was still seeking outside sources of approval when I really needed to seek it within myself.

Now that I am a writer, I have no choice but to look inside myself for confidence if I want to continue writing at all. As in high school, working hard to get the results I want is effective, but unlike in high school, hard work does not guarantee praise for my writing, no matter how great my efforts are. In fact, some readers are inevitably going to dislike my writing.

What keeps me writing is that I love to write. I love how the process feels. I love the planning. I love the rough draft stage. I love solving creative puzzles. And I love being able to write something just because writing it makes me happy. That was the epiphany that saved me from block, when I could write a sentence and simply say “I like this.”

Looking outside myself for approval and validation fragments me. Though I dislike criticism, I am more afraid of praise because it hooks me into wanting to please, which is something I struggle against constantly. I wrote a poem expressing my conflict:

Heaps of praise I hope to get

When I do not “get,” I get upset

A breach of self, do I detect?

It is risky to expect

To want what I cannot control

Endangers what I call my soul

To give is what I do myself

It puts my self-doubts on the shelf

If I gave, and only gave

I would not have to be afraid

Seeking approval is to expect, to pin my hopes for happiness on what happens to me, not on what I do. The act of writing is more like giving. It is acting, not waiting, not hoping, not expecting. As long as I focus on the writing itself and not how others react to my writing, even if my blog ever does go away, I will not be devastated.

My love for writing is the only wellspring of confidence that matters. When all around it praise and criticism swirl, what really matters is my ability to look at a sentence I have written and to simply say, I like this.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here. Also my new novel “The Ghosts of Chimera” will soon be published by the folks over at Rooster and Pig Publishing.

The post Am I My Blog? appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

January 28, 2016

How My Twitter Followers Saved My Blog This Week

The last few days have been an emotional rollercoaster. Over a week ago, my entire blog was deleted, due to a failed monthly payment to my hosting service GoDaddy. Usually the payment is automated, but my debit card had been compromised so I was waiting for a new one to take effect.

By the time I learned the payment had failed, my blog had been deleted in its entirety, and I was told by a GoDaddy rep that getting it back would be impossible; it was lost in the cyber-void and there was absolutely nothing they could do, especially since the problem was due to a payment failure, which made it an “expired account.”

Having my blog pulled from cyberspace felt painfully personal, like I had just had every one of my teeth extracted. My blog has a history, having followed me through many moods and life events, plus it contains many comments from readers that I treasure. My blog is my online identity. Now everything was erased, and I had never even been told my blog was in danger.

I tweeted about the obliteration of my blog, and a GoDaddy rep on Twitter offered to help until he learned that the deletion was due to a “failed payment.” At that point, he essentially reiterated what the first representative had told me: Sorry.

Although the news was disappointing, I only felt the full impact of my loss on Tuesday when I posted my new blog entry. No one responded with likes or comments the way they usually do. The reality was impossible to ignore. My follower list had been erased.

While I could replace my hundred plus posts, which I had been struggling to do using a website called “The Way Back Machine,” rebuilding my following was going to be something else entirely.

On Tuesday night, feeling frustrated and angry, I posted a blog entry describing what had happened to my blog. It was titled, “A Brief Note About GoDaddy Deleting My Blog and Erasing My Followers.” I shared it with my 38,000 Twitter followers.

At first the tweet went nowhere, but ten minutes later, I came back and saw that a few people had retweeted it. Later I checked again and was astonished; within less than an hour the post had been retweeted 50 times. The GoDaddy rep I had spoken to before contacted me and this time offered to try restoring my blog, suggesting that a restore attempt had been previously tried but had failed. I agreed to let him try — and it worked.

My relief was immeasurable. I felt like I had just learned that a beloved pet I thought had died was actually still alive.

While I am thrilled to have my blog back, I am also grateful to my Twitter followers for sharing my post. I have no doubt that it is because of all the shares that my problem received the attention it did, so to everyone who retweeted it, thank you!!

Unfortunately, due to my situation, my posting has been inconsistent lately, but now that the cyber-tempest has passed I am looking forward to resuming my regular posting schedule. Until then, I will be writing. And backing up my blog.

A lot.

The post How My Twitter Followers Saved My Blog This Week appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

January 26, 2016

Is All Writing Propaganda?

George Orwell said, “All art is propaganda.”

This quote haunts me. But should it? Propaganda is not necessarily evil; it is just “anything that promotes a cause or idea.” Yet the word feels sinister to me; I envision Hitler Youth posters or soaring statues of communist dictators depicted in “glorious” battle postures.

But Orwell was not just talking about politics; he believed all art was propaganda – which must include his own novel 1984. According to him, propaganda includes every story ever written. His statement is debatable, but even the idea that I am generating propaganda when I write fiction is…creepy.

Themes are an integral part of fiction, and some themes reflect “real life” better than others, which leads me to ask a strange question:

Does fiction lie?

Well, yes. “Writing that lies” is the very definition of fiction. But some fiction stories have “lied” more than others, misleading on a much deeper level than surface details they present. In fact, many of the stories I read as a kid created hopes and expectations that crumbled upon contact with reality – or at least with my experience.

As a kid, I burrowed through stacks of Archie Comic Digests. I loved them because they gave me a picture of what high school would be like. I was eager to get to high school because grammar school was a bully-driven hell.

But according to Archie Comics, high school was all about having amusing capers. All the girls were beautiful, even the rejected ones like Betty. Archie Comics created the expectation that, when I got into high school, I would metamorphose into a care-free Barbie doll.

Life would be amusing love triangles and lazy summer days spent reapplying lipstick on beaches. Conflicts would naturally arise because some characters were selfish and conceited like Veronica or mean like Reggie, but all in all conflicts were light-hearted, and everything would work out fine in the end.

In the Archie world, friendship always prevailed; high school principals were bumbling, lovable goofs that could be out-witted; and proms appeared to happen once a day. And what high school experience would be complete without being in a sexy band?

When I actually got into high school, I realized that the stories were thin. Maybe some girls had lives that resembled Archie Comic books, but for me the chasm was wide. Unlike Betty and Veronica, I had to spend most of my time studying.

Unlike them, I struggled with depression. No member the Archie gang – as far as I could tell – ever experienced mental illness. And unlike voluptuous Veronica, I looked so young for my age that people were constantly mistaking me for an eleven-year-old.