L.E. Henderson's Blog, page 14

November 10, 2015

Why I Have Been Avoiding the News

I admit it. Sometimes I avoid the news. I do not just fail to check it. I actively and strenuously avoid it. Why am I flouting what many once considered to be a hallmark of an educated citizen?

Too often the news plunges me into cynicism – not just the news itself but how it is presented. So many news articles are not news at all. They are just reports on what people said to each other. A recent CNN headline was, “Trump Blasts Gotcha Question.” The formula is: one person says something confrontational, and another person says something confrontational back. Each comment gets its own article with a headline trumpeting the polarizing remark. It reminds me of how in elementary school kids would get adrenaline rushes from verbal sparring, which went something like this:

“Oooh, did you hear what she just said? Amy called Monica a cow to her face!”

“To her face? No way! What did she say?”

“She called Amy a skinny snob!”

“Oooh, low blow! What did Amy say?”

“She said yo mama looks like a giraffe in a tutu!”

Do I need to go on? Scanning headlines transports me back to the third grade, only many news sources like CNN pass off childish name-calling as intellectual discourse. Talking heads appear on video discussing why a politician might have said what he said, which, broken down, is the spiritual equivalent of “Yo mama.”

“Now did he go too far in saying ‘yo mama’ and what exactly did he mean, and how might that, and especially the tutu reference, affect him at the polls in November?”

Not all of the news is name-calling. There is “respectable” news if you are patient enough to look for it, stories about Isis or what the Russian prime minister did, or the latest images of Pluto taken by NASA. And of course, there are murders. So. Many. Murders.

One of the main problems of taking a break from listening to the news is that I get behind on all the murders. There are so many of them, senseless tragedies that upend my day and leave me contemplating the savagery of human nature. They rise before my eyes as I try to write and make my stomach swoon. I would like to avoid anything that interferes with my digestive stability or my concentration in writing.

But getting behind on the murders can be embarrassing if a year later, someone you are with brings one up. “Remember, it was super grisly. Two guys, killed their parents with a bicycle spoke?”

“Er, yes, of course I remember.” Although murder illiteracy can be embarrassing, it does seem a little strange that I should feel civically responsible for keeping up with them.

Another factor that makes going to news websites unpleasant is visual splatter. Each headline seems to be screaming for attention, from the latest celebrity breast augmentation to a new “study” on weight loss. There are banners and ads, garish digital billboards inviting you to click, click, click.

But part of my dissatisfaction with reading news is personal. I am a writer and in the news there are no stories in a classical sense, not like fiction, which has a beginning, middle, and end. The news comes in fragments, thin layers of broken ice hiding depths of reality underneath.

Reading news stories is unfulfilling. I always think, there is more to this, and I feel like I should spend hours studying the history of, say, Afghanistan so that I can gain a full understanding of the reported events.

In college I won the department award for history, but studying a history textbook was more satisfying than reading the news. A history textbook has elements of fiction. Whether biased or objective, a historian makes the effort to give a “back story” for wars and revolutions. Effects have causes. Effects become causes of new effects. There are plots, struggles, and resolutions. A history, as the name suggests, is a story.

Though a story is an artificial construct that distorts reality, reading isolated news events does not satisfy my longing for order the way fiction or a textbook does. I recently wondered how other people deal with the information overload full of “studies,” random murders, governmental proclamations, and incendiary comments from politicians.

It came to me that many people who follow the news carefully impose their own order onto the events, creating their own stories to give the fragments meaning.

Some consult the news either to see if their party or religion is “winning.” They cheer if their team has done something right or successful and boo when the opposing team has done something to offend. There is nothing like getting offended by something the other side has done to make you love your team all the more.

I know this first-hand. When George W. Bush was in office, I followed the news more faithfully than I ever had in my life. I perversely enjoyed getting mad at George W. Bush. He was like a brilliantly drawn “love-to-hate” character in a movie. Everything he did was deeply disturbing in a way that made me feel alive. I went to the news every day thinking, “What did he do this time and what will he do next?” Or “How long until civilization ends due to his irrational and ill-informed decisions?”

It is because I understand first-hand the psychology of partisanship that I feel cynical when I see headlines obviously designed to incite political knee-jerk responses. There was a time when keeping up with the news was considered the hallmark of a responsible, educated citizen. It is hard to see that as being true in an age of click bait media, gaudy banner ads, and trollish comment threads.

Maybe avoiding the news altogether is an extreme act. I feel like it is not okay for me to drop out altogether. Can a democracy survive without an informed electorate? On the other hand, do I have to dig through endless articles of celebrity gossip and chest-thumping political provocations in order to be responsibly informed? Sorting through intellectual garbage consumes precious moments of my life in which I could be doing something I really enjoy.

There are times I need a break from the gabbling noise, the shocking headlines, the impassioned editorials, the roster of grisly murders, and the incessant debating that rarely ever goes anywhere.

I long to retreat into an intellectual hermitage to write or read fiction, with the only sounds being the purring of my cat or the quaint, distant sound of a train whistle.

Sometimes the news seems too much like the noise of a lot of gossipy, mama-bashing, insult-hurling third graders, and it is nice to block them out and enjoy, without distraction or apology, the company of my own thoughts.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here.

The post Why I Have Been Avoiding the News appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

November 3, 2015

Why “Telling” is Sometimes More Powerful than “Showing”

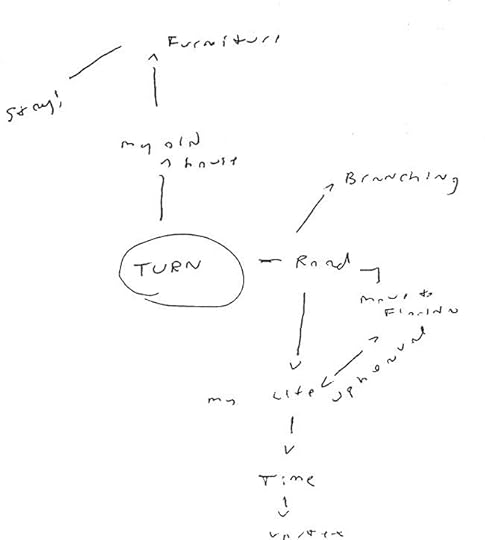

For too many years, one of my biggest problems with writing was “getting in over my head” to the point I rarely finished my stories.

I especially struggled with personal narratives. Once I began writing my story I would discover it contained many other stories. I would uncover one, and then, inside it, another, and another, and so on. They were like an infinity of Russian nesting dolls.

To describe my first encounter with bipolar disorder in high school, I thought I needed to fully describe my first depression. For honesty, I thought I had to tell the reader every nonsensical thing I was thinking while manic. I obsessed over the need to make my disordered thoughts make sense to the reader and, because the task was too daunting, I would throw down my pen in frustration.

Because of everything I thought I had to include, my stories were always spiraling out of my control.

As ambitious as it may seem to include “everything” in a story, it is not practical or realistic. In theory, I could trace any story about myself all the way back to my birth and even further to the origins of the universe. Just as a painter needs the edges of the canvas to contain his image, a writer must consciously decide where the story will begin and end, in addition to which details will be included or excluded.

But a writer must go even further; in story writing there is an unpopular middle ground between including and excluding, a technique which gets little respect in the writing world and is not mentioned much. It is called “exposition.”

Exposition is telling rather than showing, a reversal of the advice given to beginning writing students, which is to always “show and not tell.” However, in some instances, it is okay and even desirable to generalize. In the example of my writing about my manic episode in high school, I finally did succeed; in my narrative, I did mention my adolescent depression but I only touched on it, reducing it to a couple of sentences. I could have said more but I chose not to. I had to say, this is interesting, but it is not what I want to emphasize right now. However, including a couple of sentences of exposition about my early years added background that shed light on what happened later.

I did something similar with a recent fiction story in which I wrote about a man who moves to Mars. I knew a trip to Mars in a space ship would be a momentous event in itself, so my first thought was that I had to include it. I began to panic as I envisioned all the research I would need to do in order to make the trip plausible, and all the action I would need to make it dramatic and suspenseful.

But I stopped myself. That was not the story I wanted to tell. It did not support my theme and would derail my original story. The main action was meant to take place on the surface of Mars, and a short story has no room for digressions. I solved my problem by calling upon the pariah of the writing world: exposition; that is, I covered the trip to Mars in a couple of general statements. The exposition was not award-winning writing, nor was it meant to be; its purpose was to make an almost invisible transition to the next scene in which my character appears on Mars so that my main action could take the full spotlight.

When I had shaky writing skills, if I needed to move a character from a hospital to her house, I would feel I had to write a scene showing her in a car riding home since that would be the next logical step in real life. But the goal of story writing is not to replicate life as it really is but to create an illusion. The next logical step is in real life is not always the next logical step for moving the story forward.

Believing I had to include a tiresome car scene to honor reality, I would lose control of my story. My car scene would drag along as my characters made purposeless small talk. I would become frustrated with the lackluster writing and feel stuck when what I really needed to do was to move to the next important scene.

Usually, the important scenes were the ones I had vividly imagined. They may not have been full of gun fights and car chases, but they were where the “passion” was. They were the memorable scenes, the ones that seemed to “jump off the page,” the ones that had made me want to write the story in the first place. I learned to skip straight to those scenes, even if it meant temporarily skipping over details needed to make the narrative logical.

I could always go back and add transitional scenes or exposition to bridge any gaps between my vividly imagined scenes. To eliminate my boring car scene, I could have simply said, “After Kim got home…” There is nothing impressive-sounding about that phrase, but it does an important job. My short line of exposition restores control to me as a writer while keeping my story logical. Thus, the emphasis remains where it belongs: on whatever happens when Kim returns home.

However, when you use exposition, you are doing what many professional writers and writing teachers advise against: telling, rather than showing. There are good reasons why showing is almost always advised. For important scenes, showing is a far more effective way to pin the reader to the story action, evoke sympathy, and create emotion.

But telling is useful in tying the major scenes together. Because telling – when done skillfully – is so subtle, it is not celebrated the way showing is. Telling is not sexy. It fades into the background. It is the invisible hand of the writer guiding a story by selecting what to de-emphasize so that the important content can shine.

Like showing, telling is an artistic necessity, allowing the writer to consciously reduce emphasis to necessary details that threaten to distract from the main drama if they are given the spotlight. Exposition is the dim grey background that, by contrast, brings the main action into colorful, lucid, and radiant focus.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here.

The post Why “Telling” is Sometimes More Powerful than “Showing” appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

October 26, 2015

How to Own the World

From age five, Sara believed she could own the world.

She believed it even when her parents lost their house and they all had to move into a cramped apartment with peeling paint and missing window panes. She believed it until she was twelve and her eight year old sister Penny died.

The cause had been a bicycle accident in which Penny had swerved into a ravine to avoid getting hit by an oncoming car, and had hit her head on some big rocks.

On the day of the funeral, 12 year old Sara stood in the rain beneath a drooping umbrella and watched the small casket wreathed with flowers and teddy bears being lowered into the ground. As the preacher intoned a farewell full of hopeful verses, Sara did not feel like she owned the world anymore, or ever could.

Why had she ever believed anything so silly anyway? Well, it had all started with the doll.

At age five, she had been getting over a cold while drawing a doll with caramel colored ringlets and a frilly dress. The doll had belonged to the kindergarten and had looked like someone Sara wanted to be, someone kind and beautiful. Sara had longed to take it home.

The doll had worn a hint of a smile, but Sara had drawn it with a full grin. Drawing it just as it was had bored her. She had imagined the doll walking, singing, and running along a beach. On paper she tried to make the doll look like it was walking, one leg bent.

Aside from her changes, the doll was the most realistic picture she had ever drawn. Sara had caught some key quality, something of its delicacy and sweetness. Sara stared at the doll, then back at the drawing.

Suddenly the image of the doll changed. For a startling moment its face appeared to rise from the flat paper, as if the rendered doll was trying escape. Sara gasped but by the time she had reached to touch the face, it had merged back into the paper.

Sara had blinked several times, her heart pounding. What had happened? Was drawing magic?

Much later Sara would reflect that she had been getting over a bad cold at the time; maybe the “vision” had been caused by a fever or the cough syrup, but five year old Sara did not think about that.

Magic or not, in drawing Sara had stumbled onto a great power: To draw was to own; at least it had felt that way. She had taken the doll into herself and re-created it. Could she own clouds that way, or buildings, or the sun and the moon? She thought she could. She imagined that if she could draw things just as they were, she could own anything she saw.

She began drawing what she liked: butterflies, cats, dogs, moons, and carousels, imagining that one day they would all rise from the drawing paper like the doll had done. The moon would escape the paper and rise high into the night sky, the butterflies would go fluttering off the page, and the carousels would spin and play music, as the horses rose and fell.

As Sara got older she continued to draw, seeking to capture the essence of whatever she saw, hoping the magic would happen once again. Even when it never did, Sara never lost her belief in the power of drawing as a way to own the world.

When Sara was nine, her five year old sister Penny would stand next to Sara and watch her sister with wide-eyed amazement as Sara sat drawing at her desk. Penny always seemed to sense when Sara started to draw because she would show up out of nowhere, bringing with her the scent of minty chewing gum.

Sara loved Penny for seeming to grasp what Sara had always understood: Art was magic.

Sara found an echo of her belief in her art class. Her teacher had shown the students slides of cave art, saying that no one knew why thousands of years ago, human ancestors had drawn animals on cave walls, but Sara understood why; she understood perfectly. They had drawn them to own what they did not have.

But to her disappointment, nothing ever rose from the paper again. It was not so bad. Drawing still mattered. It was a celebration of sight. To draw an object was to know it, to absorb it, to grasp its essence, to become part of it.

But now, standing in the rain, Sara thought she had been all wrong. She knew who really owned the world. It was not cave artists, not world rulers, and not Sara. Death let you think you could own things, including yourself, but in the end it swallowed you. One day it would swallow the whole world.

If Sara could not own death, she could not own anything, let alone a planet. She could not fathom death either. She thought of the doll often during the days that followed the funeral.

She liked to imagine she could bring her sister back, make her rise the way the doll had risen so long ago, so Penny could stand behind Sara like a shadow again and watch Sara draw like before.

For a time, Sara brainstormed ways she could re-create her sister the way the ancient cave artists had re-created animals. She made many drawings of Penny and ended up in tears. At night she would pick over her supper, take only a few bites, and push her plate away.

The dining room was always dim, lonely, and silent, even when her mother was there eating with her.

One day Sara could not bear the silence inside her house. Without Penny, the whole house seemed dark, cold, and vacant. It seemed that death had come to her home like an obnoxious uninvited dinner guest, propped up its feet, and ordered everyone to lay low, to hide, to cower.

In her bedroom Sara gathered all her drawings. It was time to test their power once and for all. They were worthless if they could not help her now. She wanted magic to happen as it had long ago when she had made her crayon doll rise – or seem to rise – from her drawing paper.

She waited, but nothing happened. Her vision blurred, and her head felt like it would float away.

Suddenly she felt silly. What happened in kindergarten must have been a false memory or a fever induced hallucination, and she had let it affect her whole life.

All these years, she had thought she knew how to own the world. It had been a secret that had given her hope even when she saw kids who had far more than her.

Now an invisible fist gripped her throat, and tears began winding their way down her cheeks. One of them passed her chin, paused there, and struck the one of her drawings on the floor. She sank to her knees, her head bowed and her eyes closed.

Something warm and a little heavy fell gently on her hair. At first she smelled a minty fragrance and, when Sara raised her head, she saw a girl.

The girl looked like her sister, smelled like her sister, and smiled like her sister.

Sara sniffed and said, “Penny?” She rose, reached toward Penny, and touched a cheek to see if her sister was real. It felt soft and warm. “Are you real? Did I really bring you back to life?”

“Not exactly,” Penny shrugged. “I was alive before you called me. And dead, and something in between.” Penny furrowed her forehead. “Hard to remember if I was alive before I was dead, or dead before I was alive.” She shook her head. “Time is stranger than anyone knows.”

Setting aside the strange words, Sara thought, this is not Penny, not the Penny I remember, not the baby sister who had once looked up to her. This Penny was too knowing, a frightening stranger. Still, Sara wanted to believe the phantom was Penny. She wanted to understand.

“How can you be both at once?” Sara asked. “Dead and alive, they cancel each other out. And time; it only goes one way. How could you have been dead before you were alive?”

“I still feel confused about so many things,” Penny said, “but I do know time is not what it seems to you, not something outside you. Time is movement, just like life is movement. Without time there is no death, but no life either. Time is a cycle of starting and pausing, and we are part of it. It never stops, it only seems to sometimes. We inhale it. We move inside it. You could even say, we are it.”

Sara frowned. “Time killed you,” she said. “One day it will kill me and everyone I love.”

“Time does not kill us nearly as often as we kill it. You see time as cruel, but time is the greatest, maybe the only power we have. Every moment is like a canvas, or a cave wall we get to draw on. Time gives us the ability to act. Why do we imagine we could exist apart from it? We inhabit time. We breathe time. We are time.”

“We are time? What does that mean? You mean eternal? Like we live forever?”

Penny shook her head. “No, not eternal. I think we are eternity. At the birth of the universe, we were there, you and I, our potential stirring, unseen, among gaseous cloud of hydrogen atoms.

“And even before then, we were there, our potential to be alive existing inside of whatever there was, even if no one was there to see it. For an eternity stretching back into the past, you always had the potential to someday be alive just as you had the ability to someday die. If we exist, we have always existed, and will always exist.”

Her lips trembling, Sara said what she had never told anyone. “I used to think I owned the world.”

“You have never owned anything, Sara, and you never will. But owning is pointless. Moving is better. Moving and being moved. That is the power time gives us, to fill empty moments with movement. Be ambitious Sara. Forget about owning. Use the magic you have used to summon me, and create.”

To Sara the words were like warm water flowing over her skin. Penny rested a soft palm on her shoulder. “Keep drawing on the walls of time, Sara. Keep moving. And when you go, you will leave behind a record of your passage. And even if no one ever sees what you have drawn, time will never forget you, or it, because you are part of time and time is part of you.”

Momentarily comforted, Sara started to hug her sister, but before she could, her sister vanished and everything went dark.

Sara opened her eyes and found herself lying on the floor. She sat up a little and saw that there was a grey wet spot on the white paper of one of her drawings. Tears were clinging to her eyelashes as she looked all around. Had her sister really been there?

As the day went on, Sara tried to hold onto her new sense of purpose and understanding, but her sense of the miraculous faded. In her “vision” everything had seemed so beautifully clear. The words that had made perfect sense in the moment now had a hazy dream-like quality.

Sara avoided her sketch pad for days after her “epiphany.” Drawing seemed silly. Everything did. But after several days, she missed it. She went to her desk drawer where she kept her sketch pad, opened it, and withdrew her pad and pencils.

She flipped through the pages and saw what she had drawn. Some sketches were well drawn, others not. Many were of animals: cats, dogs, and ponies. In each she had tried to capture what was living in what she saw and pin it down like a butterfly collector does.

She had thought the goal of art was to capture what she did not have, to grab moments like butterflies from the air, to own them. Because she believed drawing realistically was the key to her magic, everything she drew appeared to be motionless. Her cats did not run. Her birds did not fly. Strange since, in the cave art she had seen, most of the animals had been moving: horses ran, deer leapt, bulls charged across the cave walls.

She turned to a clean page in her sketch pad. Holding her pencil, thinking of animals moving, she could feel something stirring inside her. It went down her spine and through her arm and into her hand. Thinking of what the ghost had said, she imagined time as being wind, and she inhaled it, felt it flow through, over, and around her.

What was it that had changed? In kindergarten she had thought the doll came to life because she had made part of it look real, but now she remembered she had changed it. In her mind and on paper, she had turned its partial smile into a grin.

Now she imagined a bird flying and began to draw it. Lines upsurged, went diving, spun around the animal and through it. She stopped for a moment to see what she had done. Her drawing looked real, but there was more to it. She had captured its motion.

A flash of light forced her eyes shut. A fluttering wind blasted her face and she heard rustlings, flapping, and a whoosh. Even before she turned her gaze to the windowsill she knew what she would find.

A bird dove from the windowsill, glided toward her, and landed softly on her shoulder. She slid her finger beneath it and looked into its eyes, wild, curious, dark holes that seemed to burn with the ancient power of the universe.

Breathless, she saw in the motion of its flapping wings the irresistible winds of eternity, and felt in them the power to look forward to the future and back into the past. To gain and to lose. To advance and retreat. To destroy and create. To move and be moved.

But most of all, to move.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here.

The post How to Own the World appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

October 20, 2015

My Scuffle with the Happiness Police

Be alert, smile like you won the lottery, say cheese, do it, do it now.

There is a photograph of me. I am at a beach. Behind me the sun is beginning to set over the Gulf of Mexico. My lips are smiling. My eyes are not.

Right before the display, one of the friends I was with drew out a camera and aimed it at me.

As directed, I smiled. But later, another friend noticed the absence of radiant joy in my eyes in the photograph and demanded of me what had been wrong with me the day of the sunset. I felt like I was on a witness stand in some black and white detective show, Perry Mason perhaps.

“Miss, what were you feeling on the day of the sunset? What were you thinking?”

I imagined myself crossing my legs and taking a long languorous drag on a cigarette. “It is hard to remember exactly what I was thinking that day, Mr. Mason. But it is likely I was thinking, as I often do when someone suddenly wants to take my picture, ‘A photograph? Now? Do I really have to do this? Right now?’”

“But what about the beach and its happiness-inducing influence on most people? What were you doing wrong? You must have been thinking of something un-joyful. Otherwise, the beach should have produced unalloyed delight.”

“I like the beach, Mr. Mason, I do. But the camera pulled me out of myself. It suddenly reminded me that I must seem to be something to others, specifically happy.

“I dislike fake smiles. Afraid of looking fake myself, I have always tried to be genuinely happy when a camera was aimed at me. But radiant joy on demand is sometimes hard to come by, Mr. Mason, and on the day of the Gulf Coast Sunset, I was unable to summon it.”

“But the beautiful setting alone should have done that, Miss. You had everything to be happy about that day, but this photograph does not lie. Your eyes are not smiling. What really went wrong? What were you thinking and feeling? What is your defense?”

Feelings and thoughts are not crimes, but photographs represent to me the cultural attitude that if you are not happy at all times, something is wrong. Even feeling “just okay” is inadequate when there is a sunset or a circus While I honestly had enjoyed being at the beach, I had never reached the point of euphoria. My lips had played along but my eyes told a truth, one I had not known was scandalous: a shocking lapse of ecstasy. A less than euphoric feeling had crept into the otherwise idyllic scene like a bratty brother with a spitball.

But is it fair to expect everyone to drop all their emotional complexity in the presence of a camera; to reduce themselves to a single dimension of feeling? Why all the pressure? Is it upsetting to viewers to see any personal photograph in which someone is anything less than perfectly happy?

Paintings capture so many different emotions, from the cryptic almost-smile of the Mona Lisa to the primal scream of Edward Munch. Unpopular emotions like rage and sadness are vital parts of the human emotional repertoire. Fine art honors them.

Why is the full human range of emotion acceptable in fine art but not in personal photographs? Do we need a visual record which “proves” that everyone we have ever met is in a wonderful mood? Why is it the rule in photographs to always smile?

I have always followed the rule. In all my school photographs, I am smiling, even the ones from the year I was bullied to tears every day and the year I encountered a nightmarish depression for the first time.

There were certainly moments of joy during those dark periods of my life, but they were not the norm. Was it fair to have to represent myself to everyone who saw those photographs that I was feeling great?

I like the photograph of myself at the Gulf; despite the pressure, something honest had snuck into the picture like a naughty cat. I could not quite conjure the expected mood that day, could not be the person I was asked to be, under the setting sun, at the Gulf Coast Beach.

I was not miserable that day, but not totally happy either.

I just was. And that is not a crime.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here.

The post My Scuffle with the Happiness Police appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

October 13, 2015

Is art a realm of love and hate?

I had a friend who when she did not like a book was not content to merely dislike it. She was ready to tear the book to pieces and consign it to the lowest levels of hell.

I had a friend who when she did not like a book was not content to merely dislike it. She was ready to tear the book to pieces and consign it to the lowest levels of hell.

Sometimes the books she hated were books I loved, and her gagging fits baffled me. How could the writer have inflicted such a book upon the poor unwary world? It should be struck from shelves, torn to bits, possibly burned, and tossed into the Mariana Trench to be consumed by angry sharks. What a horrible person the writer must have been to write such a book.

The books were not pornographic, sexist, racist, irreligious, or profane. In fact, one of them was a Newberry Award winner, the prestigious prize given to the most highly acclaimed fiction for children.

I always felt sorry for the authors who were the subject of the rants. Whatever their flaws, I understand how much thought and courage is required to take an idea from a seed to maturity, despite struggles with under-confidence, uncertainty, and fears that the project could fail.

Recently I have struggled with insecurities of my own. I just had my newest novel proofread by someone who is not a fan of the fantasy genre. Though I only asked him to do line edits, he was liberal with offering his personal opinions, and he did not use tact.

In some places his only comment was “What??!”. He seemed particularly offended by passages where I had tried to be creative or expressed my personality.

I would not have had the novel proofread if I had thought my novel was perfect, but why the punctuation bombs? Should I feel hurt? Apologetic?

My experience has led me to wonder why responses to art are so vitriolic. In art there are no hard and fast rules. Depending upon the purpose of the artist, some principles generally work better than others, but deviating from the standard guidelines is sometimes essential.

That does not mean everyone will approve. In fact, some disapproval is inevitable if the audience is large. But why are responses to seemingly harmless artistic expressions sometimes so violent? If I dislike a book, I do not damn it to hell or attack the character of the writer. I simply stop reading it.

Do we inhabit a culture that encourages shaming artists? The television show “Project Runway” convinced me we do. The popular reality T.V. show always culminated in judges gushing over their chosen winner while ridiculing the “losing” fashion designer to the point that he would often end up in tears. I always hated that part, which is why I stopped watching the show.

The contestants had done their best, given their stringent time constraints. Seeing them crumple on stage reminded me of how much my own fears of ridicule had kept me from writing for many years when I could have been enjoying an activity I loved. The freedom to make mistakes is essential for artistic growth.

But if we do have a culture that shames its artists, why? Is it a gladiatorial blood sport? A way to project our personal insecurities onto others? What is it about human nature that yields such emotionally extreme responses to art, much of which has been built with care and the best intentions?

I recently heard an interesting explanation, which is that it is the nature of art to be loved or hated. There is no middle ground. To experience a book as “just okay” is really to hate it. People experience emotional blandness in their everyday lives. They do not want it in their art. They turn to music, movies, and books as a way to intensify the feeling of being alive.

If a book or movie fails to accomplish that for them, the audience can find some satisfaction in hating the art itself; that way, at least all is not lost. It was the worst. Movie. Ever.

Art is inherently polarizing. Its success depends on taste, which varies widely from person to person. Maybe that is why people so dogmatic about their artistic preferences. Uncomfortable with subjectivity, they seek to settle the matter of what is good or bad once and for all.

But how does the climate of emotional extremes affect artists? For one thing, it discourages some people from even attempting it. In a choice between writing a novel and watching television, watching television is far safer. Moreover, television requires no effort and few will ridicule you for it.

Creative endeavors are emotionally risky. Courage is indispensable in a field where even the most competent and original artists are bound to be rejected, just as they are bound to be loved.

To avoid rejection an artist may be tempted to try to please everyone; to induce no nightmares and evoke no pain; to say nothing anyone is likely to disagree with; to avoid originality at all costs. That strategy produces the blandness of most Hollywood films, forgettable, predictable, not so much art as thin diversions.

Moreover, even bland, formulaic, and crowd-pleasing “hits” are not immune from criticism. To survive as an artist means embracing the truth that there is no universal acclaim and that the more original art is, the more polarizing it is likely to be.

Looking at the notes of my proofreader, I wonder: Is writing worth seeing the word “What?!?!” splattered next to an innocuous phrase where I had attempted to be original?

I would like to avoid getting the “What?!?!” response, but I remember my agonizing period of being blocked during a severe depression, in which I was so afraid of ridicule and criticism, I thought I would never be able to write again.

Comments like “What?!?!” were just the kind I feared, reminding me of when I was in grammar school and shamed for liking the wrong kind of music or wearing unpopular tennis shoes, or eating something “weird” at lunch. Gross. Shocking. What?!?!

As a bullied sixth grader, I handled the shaming by trying never to do anything to call attention to myself. I stopped talking at all. Writing was the place I went to for expressing who I really was, and it still is. I refuse to say only safe and predictable things so that I can avoid the electric shock of an inexplicably offended over-reaction.

Writing is my world, and there is comfort in knowing that there is no universal acclaim in a field that serves as a lightning rod for the emotions of love and hate.

If the nature of art is to stir up the most extreme feelings, aggressive treatment of artists is likely to continue. Therefore, it is up to the artist to realize that offending does not mean there is anything wrong; on the contrary, it means everything is going exactly as it should. In a field dominated by opposite emotional poles, the more artists are willing to be hated, the more likely it is they will be loved.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here.

The post Is art a realm of love and hate? appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

October 6, 2015

Seeing Past Criticism in Writing

My growth as a writer has depended upon learning ways to protect myself from myself. Having bipolar disorder, I have had to learn to see flaws without self-abuse, and to correct my work while keeping despair at bay.

While trying to avoid mood crashes during painstaking revision, I stumbled on a way to improve my prose without focusing on my errors. My technique is similar to an exercise Natalie Goldberg introduced in her famous book Writing Down the Bones, which I highly recommend.

She asked readers to write a page or two of text but afterward, instead of combing through the text for what is wrong, you search for the places where your mind is “present.”

What does she mean by the mind being present? Or, to put it a different way, how can the mind be absent? Minds sometimes wander during writing, and empty words take the place of thought. Often there are fillers in writing, kind of like the Styrofoam peanuts in a cardboard package that obscure the real treasure like a new stereo. Something similar happens in conversation when people say “um” or “ya know” a lot.

Like Styrofoam fillers, words often end up obscuring rather than expressing our thoughts. Clunky transitions, inflated language, verbosity, and poor organization can kill reader interest. The Natalie Goldberg exercise is to go through the text and find places where the thoughts appear to “jump off the page” or where there is a sense of clarity. The “filler” is thrown out altogether so there is no need to pick over it.

I loved this exercise and started doing something similar whenever I found myself becoming so self-critical while revising that the words would seem to tangle together into a blur.

I still use my technique a lot. First I make a copy of the passage I want to revise. Then I find the parts I like most and highlight them, sentences or phrases where the prose is transparent, honest, vivid, or intriguing. I look for text that evokes the original vision that drove me want to write the piece in the first place.

I delete the rest.

Drastic? Well, maybe, but it is not as drastic as it sounds since I have made a copy; if I change my mind about the passages I have cut, I can always bring them back. But after trimming the excess, what I am left with are my favorite parts that, however fragmented, remind me that writing is about building, not shooting down what does not work.

Reminded of my original vision, I work to make the rest of the text rise to the level of the parts I love. I build transitions to glue together the sentences I have broken apart in order to create something new. I use the process mainly in my nonfiction, but it is useful even in fiction as a way to rediscover my focus and get me back on track. It makes me ask, what is the substance of what I want to say? What was the point of view, emotion, or theme that excited me originally?

“Rebuilding” text is not always easy, but I enjoy it. I do not resent the rewriting I do in order to create a product I am proud to share. What makes writing psychologically torturous is that we are wired to locate and shoot down errors in our writing. Revision is like a game of Whack-a-Mole without any of the fun. Ew gross! Bad, bad, bad! Get it out NOW!

We approach out work with a trouble shooting mindset. Instead of watering flowers we are pulling weeds. As we do, the neglected flowers wither. “Rebuilding” allows me to return my focus to the flowers.

Visual art offers a similar example. Michelangelo said he saw sculptures in stone and his objective was to cut away everything that was not the sculpture, thereby releasing a form from its rocky prison. Even though he chipped away all the useless parts, he never lost sight of the original vision that inspired him.

Too often, writing feels more like killing than bringing something new to life. The dream of what could be becomes lost as enthusiasm fizzles. Remembering to focus on the parts that appeal to us reconnects us with our original vision and illuminates the way forward so that, headed for the flowers, we can leave the weeds behind.

The post Seeing Past Criticism in Writing appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

September 29, 2015

Terrible Writing Advice

When I was a college student I was hungry for any tips that would further my dream of becoming a professional writer. I eagerly read through stacks of magazines and books on writing.

But a lot of the advice, even from my favorite authors, confused and upset me. Often the advice givers had “clout,” so I was reluctant to challenge them, even if what they said contradicted earlier assertions or what another renowned writer said.

Bad advice hampered me for many unhappy, unproductive years. Some of it passes for common sense and gets repeated day after day and is bound to be repeated again and again for many years to come.

Here is some advice that frustrated and confused me most.

“If you consistently find it hard to make yourself write, it must not be for you. You should give up and do something else.”

This was the advice that made me stop listening to writing advice.

In a writing magazine an interviewer asked a best-selling author to offer tips to struggling writers. He responded by saying that if you have trouble making yourself write, you probably just like the idea of being a writer, and you should give it up and go find another activity you can enjoy more, and leave the writing to writers like him “who can’t help themselves.”

At the time I read this, I was severely depressed and going through the worst case of block I had ever endured, but I was still trying to write every day despite my mood crashes and general misery. The advice deepened my despair and strengthened my fears that I would never be able to enjoy writing again the way I had as a kid.

What saved me was remembering that I had enjoyed writing as a kid. I may have lost the sense of it being fun, but it was not that I did not want to write. Something else was going on.

There are many reasons why someone who wants to write may dread writing, fears of criticism and failure being high on the list, and that was the case with me. I finally got past my block and I am so glad that, instead of following the discouraging and unhelpful advice from a writer with “clout,” I stopped reading magazines on writing and started thinking for myself.

“On the days you write, you must read constantly.”

Whenever someone says “Read a lot,” I am inclined to agree with them.

I have always loved to read. Reading is where my love of writing began. However, the “read constantly while writing” rule frustrated me because even if I had written prolifically on a particular day, I also felt pressured to read “a lot” and I would feel I had failed if I had not met a self-imposed reading quota.

Plus, after reading, my imagination was already engaged. When I settled down to create my own worlds and stories I had trouble switching from reading mode into creating mode. I would also compare my own work, usually unfavorably, to what I had just read. If I wanted to immerse myself in reading a work of fiction, I had to do it after I wrote, not before, but if I had written for over 4 hours, my mind would be too exhausted for immersive reading.

As a rule, the more I read, the less I write, and the more I write, the less I read. It is not hard to see why. On the days I write a lot, I do not read much because (drumroll) I am writing.

I treasure reading, but I am unable to read and write at the same time, no matter how much I may love to do them both. Accepting this has relieved pressure so that I can focus fully on my writing when I need to, and set aside other times for reading when I can give it my full attention.

“Make yourself write every day, at the same time, for an hour or more.”

While this often-repeated advice sounds sensible, I tried following it for many years and only ended up frustrated. For me it was too rigid. I imagined that on each day I must produce equal output and spend equal time writing, or I had failed.

But each day insisted on being different than the day before. Some days brought interruptions beyond my control. I had headaches and depressions and illnesses and sick cats. There were days I had not slept the night before and could barely hold my eyes open.

Setting up inflexible conditions for success was not helping, but hindering me. All I wanted was to write consistently but the rigid structure was unnecessary and led to a state of constant guilt, frustration, and self-abuse.

The rigid rules set me up for failure. If I did not meet every criteria, if I wrote for 34 minutes and 4 seconds instead of the even four hours I had planned, I felt like I had failed completely and would not even give myself credit for the 34 minutes and 4 seconds I did write.

What finally worked was that, rather than setting ambitious targets for my writing, I set small easily achievable goals like a sentence a day. Sometimes I even experimented with setting limits of one sentence or 15 minutes. When I made myself stop writing, I would go away wanting to write more. By limiting my writing on some days, I rediscovered my desire to write. Gradually, by easing the pressure off myself, I was able to increase the amount of writing time in which I could focus fully on my fiction and enjoy it.

My only rule was to always write at least sentence a day, which was easy to achieve even on days I was sick or felt depressed. If I wrote more than a sentence, which I almost always did, I could congratulate myself, but if I did write only a sentence, that was fine too, and it kept my guilt at bay.

Despite what many believe, guilt is an enemy of writing. Guilt drains energy while creating resistance and a need to make excuses. It hurts me and it hurts my productivity. It has no part in my writing process, and if I see it coming, I give my cat permission to chase it into a corner and make a snack of it.

When my cat is asleep, the one-sentence rule banishes my guilt, but after writing a sentence, I almost always want to write more. However, do not use it as a way to “trick” yourself into writing longer. In fact, it is not a bad idea to take yourself up on the offer to quit every now and then. Being honest with yourself is always the way to go.

Thanks to the “one sentence rule,” I never have to force myself to write anymore. The amount of time I spend writing each day varies, and so do my starting times. I usually write around 4 to 6 hours a day now, but if I only get in 30 minutes, that is okay. I have accomplished what I desperately wanted for many frustrated years: to write consistently while thoroughly enjoying what I am doing.

“Writing is grueling work like coal mining, and if you expect to have fun doing it, you will never be a professional.”

On some days writing is harder than others, but if I did not mostly enjoy it, I would be doing something else. Writing is not known for its high pay and the market is flooded with legions of other writers who make it difficult to stand out and earn a living wage.

No writer should ever feel guilty about not having “fun,” but if writing makes you feel like you are pressing your palm onto a hot stove while chanting “fear is the mind-killer,” something is wrong. Writing is hard, sometimes insanely hard, but it should not cause wailing and gnashing of teeth.

If it does, that does not mean you should quit writing. At one time writing was “hot burner” torture for me, and I almost gave up but I was able to get past it.

As for the charge that anyone who writes for enjoyment is unprofessional, many renowned writers such as Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov have described writing as a wonderful addiction. Ray Bradbury went so far as to say that he had never “worked” a day in his life. At one time I was unable to identify with them at all but now, like them, I find it difficult to stop writing.

“Before writing, do research to find out what agents and publishers are looking for.”

This advice may have confused me the most. I had loved writing since I was a child and had always been praised for it, but, even when working for a grade, I had always felt free to write what I cared about and in my own voice.

Writing to please publishers and adopting their “editorial styles” was a foreign and uncomfortable idea, and one that sank my mood. However, it seemed to mark the difference between a professional writer and an amateur, between a “real” writer and a wannabe.

I thought that if I was as good a writer as my teachers said, I should be able to meet the biggest and most important challenge: to please and impress publishers. However, a barrage of form rejection letters from magazines suggested that school had not prepared me for “the real world.”

I turned to magazines on writing for help. The covers would always say something like “Get Published: Top Writing Trends” or “Ten Interviews with Top Agents: What They are Looking For.” I would pore over those magazine articles, getting more and more depressed with every word I read. At the time I believed I felt depressed because I lacked the necessary skills to succeed.

Now I can see that much more was going on. I had been a painfully shy, bullied kid who had turned to writing in express parts of myself that had “gone underground.” Writing had been my refuge, the one place where I could make the rules and express how I really felt and what I thought. Plus, I had enjoyed writing.

Guessing what a publisher wanted and delivering what they already had in mind excited no passion; spurred no creativity; inspired no vision.

Most of the complaints in my rejection letters was, “It does not fit.” It did not fit their needs or their editorial style or the trends of the moment. So the obvious question seemed to be, “How can I fit?” It was the wrong question.

After many years of block and confusion, I could see that the need to “fit” had taken away my sense of owning my work; stripped it of fun; and turned writing into a numb chore. To enjoy writing as I once had, I had to write what I would want to read, not what I thought others wanted to read. When I wrote what excited me, readers responded well. This insight helped to restore my creativity and made writing fun again.

“If you really want to be a writer, go out and get a lot of different jobs for the life experience.”

This falls into the category of vague, difficult, and time-consuming “prerequisites” for writing that once made me feel like I would never be qualified to be a writer. It conspired with my under-confidence to make me put off writing and made me feel that my dream of being a writer would forever recede beyond my grasp.

Experiences do enrich writing, but “going out and getting” them is unnecessary. Experiences are everywhere. Writing fiction requires being literate and human, and having experienced the emotions of love, hate, sadness, jealousy, and fear.

S.E. Hinton, author of the classic best-seller The Outsiders was a teenager when she wrote her novel. She had never been a lumberjack, a bar bouncer, or a crime reporter, yet she was able to craft moving and unforgettable story using the experiences and insights she did have. Writers do not need “exotic” experiences if they are perceptive enough to see the strange in the familiar. “Going out and getting jobs” for the vaguely defined purpose of having new experiences is time-draining and absurd advice.

I have given a summary of writing advice that impeded my writing for much of my life. That being said, every writer is different. Some writers, for example, seem to work well under deadline pressure, whereas I resist it.

Some writing advice has helped me, but it can be destructive if accepted uncritically. Writing is the best teacher, and the ideal is for writers is to move beyond obeying “authorities” to becoming authorities themselves.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here.

The post Terrible Writing Advice appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

September 22, 2015

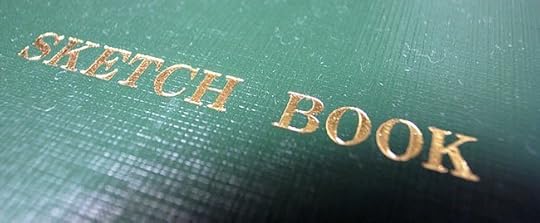

Why I Have Started Drawing Again

Last weekend I bought a sketch pad and a pencil set and have been drawing again. Though I majored in art many years ago, I am way out of practice and feel like a kindergartener learning to draw for the first time. My efforts do not bring the aesthetic rewards I get with writing, my sense that “Yeah, this is working. I love this.”

But I want to see if I can apply what I know about getting past block in writing to visual art, particularly setting limits to entice myself into wanting to draw longer. In writing, forcing myself to write always failed, but if I forbade myself to write longer than 15 minutes, I was always left wanting to write more.

Limiting my drawing time has another plus. I have been reluctant to draw because I worried that art would take over and shatter my focus on writing, which is still what I care about most, so for now I am limiting my drawing to a half hour a day.

When I draw, the old feelings I once had about writing are cropping up: “This is a waste of time. You are bad at this. Focus on the things you are good at. Everyone else is way ahead on you on this.”

When I have those kinds of thoughts, I am doing what I did many years ago when I was blocked with writing: I am arguing back with them. I want to reclaim the freedom to fail. I want to be able to make mistakes. Unlike with writing, I have no professional aspirations in visual art. My goal is to regain my love of art, which I lost so long ago at age 13.

Shortly after I turned 13, depression swooped in from a shadowy place in the sky and struck me down. I stopped doing the things I had enjoyed most as a child. I stopped singing. I stopped writing for fun. I stopped drawing. And I had not only enjoyed them; I had gotten a lot of praise for them and had even been accepted in in a “Project Challenge” program for art.

Before adolescence, writing and art had gone together like the illustrations of my old fairy tale books had gone with written stories. Drawing and writing had woven their way through my creative life, though words came to be my favorite medium.

But beneath the shadow of adolescent angst, those days appeared to be gone. It seemed to be all I could do to get up in the morning and go to school. After three years I recovered from my depression but did not recover creatively. I was way out of practice and had seemingly more important concerns.

At fifteen I made an identity out of excelling at school, but abandoning creativity had drained color from my life. I wrote only when I had to and no amount of praise from teachers encouraged me to write on my own; rather, the praise intimidated me by creating high expectations. I was always beginning stories but never finished them. I feared writing because I feared disappointing. I had occasional moments where “inspiration” would strike but they were like snow in the South. Those unpredictable “flurries” happened to me, and only rarely; they were not something I did.

To motivate myself I enrolled in a high school creative writing class and dropped out after the first week. Creativity was not something I knew how to control; there were no reliable rules; I felt unsafe.

Similarly I enrolled in an art class, hoping to recapture the creative thrill I remembered, but by then it seemed too late. Other students had kept drawing long after I had stopped and most were far ahead of me.

I would look at the art supplies with a nostalgic thrill and remember the fun I used to have with them. But when I sat down to draw, my skill did not equal my enthusiasm. Drawing hurt, just as writing hurt because I felt pressured to be “good.”

In college a new shockwave of depression left me pining for art again. I went so far as to change my major to art, even knowing I would lose my treasured straight A average, which I promptly did.

I learned a lot about creativity as an art major but could not seem to recover my childhood love of art. I did not have the sense of owning it that I had known as a kid, and was always comparing myself unfavorably to the better artists. Everything I did in college I did for a grade. I learned many interesting techniques but had no sense of artistic freedom.

After college I dropped art altogether, because art did not seem to be my talent anymore; writing was.

But even writing was always a stop-and-go effort. My path was cluttered with fears of being trite; self-indulgent; sentimental; or silly. I was chronically blocked, but somehow through all that I managed to write my first novel after college. Even then, writing came with the risk of terrible mood crashes.

Everything came to a head during the severe depression I wrote about in A Trail of Crumbs to Creative Freedom. The depression followed a manic episode that led to the worst case of block I had ever experienced. I locked down completely and thought I would never enjoy writing, or anything creative, ever again.

At that time I felt most keenly that loss long ago when I had given up on the creative activities I had most loved. After one particularly painful day, straining to write a new novel, my sense of loss took the form of terrible hurt, rage, and rebellion. “Critics are stupid,” I thought. “This is my writing. If I want to be trite, or self-indulgent, or sentimental, I will be. I am going to write whatever and however I like.”

It was one of the few true “epiphanies” I have ever had, and it ended my block for good. But although I regained my love of writing, sometimes I still missed art. Not the art of my college years where it was all about pleasing teachers, but the art of my childhood where I used pencils, crayons, and markers as a way to explore the world.

As before, I would become excited whenever I saw art supplies but became crest-fallen when I realized how out of practice I was, and that I lacked the skill to do anything amazing with them. So I have decided to use the same principles I outlined in A Trail of Crumbs To Creative Freedom to recapture my connection with visual art.

As I do with writing, I give unconditional praise at the end of my 30 minute session, if only to say, “Good effort” or “One of the lines you drew was interesting. I like it.”

It feels good to draw. I have been living with the belief that because I gave up drawing at 13, it was too late for me to pick up on it again, but my experiences with writing have convinced me otherwise. I wonder why our culture gives only children free reign to experiment and fail.

Children are given the freedom to mistakes and are praised for most every artistic thing they do, which encourages experimentation and learning. But as adults we rarely give ourselves the freedom to start fresh. There is a feeling that as adults we must have a set path, and that what we are, or are not, has already been determined, and that we must live with it or risk looking silly.

But it should always be okay to be a beginner. The freedom to make mistakes should not be a privilege restricted to early childhood.

After drawing for a week, I now look at my sketchbook and the pencil set I bought and instead of feeling sad that I am not “good” enough to use them, I am starting to feel excited about the possibilities that consistent practice will bring.

As for my worries about “art taking over,” I am starting to relax. While writing may be my main passion, it is not such a jealous lover that it will begrudge me spending a half hour a day with an old friend. Writing knows I will never leave it.

That there is not even a chance.

If you enjoyed this post you might like my other writing. Take a moment and sign up for my free starter library. Click here.

The post Why I Have Started Drawing Again appeared first on PASSIONATE REASON.

September 15, 2015

The Doppel-Bot Corporation (Short Story)

The representative Diane Arlington at Doppel-Bot told me my therapy would not be easy. “Many people think that they may overhaul their personality patterns, their habits, and their responses to stimuli on a whim, or simply by making a resolution.”

“But sometimes resolutions do work,” I protested. “Do you mean we can never change? For the better?”

“I hesitate to say never, Cassy. We may change superficially and within strict limits. But few delusions frustrate us more than free will. We are all running programs. Fighting our genetic personality wiring brings about guilt, frustration, and anxiety. We are told to adapt, but in some cases, we must adapt, not to our environment, but to ourselves. To do that you must know yourself as well as you would if you could see yourself from the outside. Our emo-units can help you with that. Are you ready?”

I nodded.

The lady walked over to a closet, removed a key card from her coat pocket, unlocked the metal door, and swung it open. “You may come out,” she said to whatever was inside. I heard a whir of movement, then a rattling sound.

The silver colored robot clattered out of the closet. Its coquettish yellow skirt stopped at the knobs of its knees to reveal spindly metal legs and bare slabs of claw-like feet. It had an hour glass torso covered with a lacy sleeveless white blouse. The head was crowned with a shaggy, tilted, short blond wig.

“Meet Cassy Bot,” Ms. Arlington said. She moved toward the robot and wobbled the wig a bit to straighten it, and pressed it flat onto the head, but as soon as the lady moved back, the wig flopped to the side again.

“You named her after me?” I said. “She looks nothing like me. Where did you get this old hunk of metal? A used car lot?”

The representative Mrs. Arlington laughed. “Humble, yes, but humble by design.” She pressed her fingertips together. “Our goal is to de-emphasize physical appearance so that you can focus exclusively on her behavior. Using your personality tests and brain scans to form a profile, we have created a program that will make your twin approximate your behavior and responses to an astonishing degree. Would you like to say hello to her? Your other self?”

“Um, hi,” I said.

Cassie Bot bent her legs and made a jerky flourish with her arms. “Thank you,” she said in a tinny voice. She took a few mincing steps forward and held out a shy upturned palm.

I turned to Ms. Arlington. “Thank you? I think you need to adjust her etiquette algorithms.”

The lady only shrugged. Cassy recaptured my attention with a musical burble so I reached forward to take the artificial hand. Cassy Bot did not actually shake my hand but lightly clasped it. Although her “skin” looked like metal, it felt strangely rubbery and yielding.

When I stepped back, Diane said, “Say whatever else you want to say to her now. You will not get to talk to her anymore. Awareness of your presence will alter her behavior. You may wake her at eight in the morning, but she will not shake your hand. I have arranged that she will be unable to see you or hear anything you say. Meanwhile, stay out of her way and take notes on what she does. The goal is to gain insights into yourself. Any final words to her before I clear her mind of you?”

I shrugged.

“Very well then. Oh yes, some of her actions may upset you, especially if you see your less flattering side in them, so you will be unable to turn her off for at least 24 hours. This safeguard is meant to keep you from giving up too easily.

“And remember: Cassy Bot will believe anything you have ever done or written on your social media websites is her doing and will act accordingly,” the lady said. “She honestly thinks she is you: a 22 year old college grad who works as a waitress.”

I agreed to give the experiment 24 hours beginning at eight on the following morning. My excitement mounted. For a day a robot was going to live my life for me. She would be my mirror, and I was to observe.

The representative added. “There is a failsafe, a bright red button beneath her wig, which controls her awareness module. Use it only in an emergency. Our robots feel emotions just as we do. They do not know they are running programs but believe they are acting of their own free will. For her to find out otherwise would be…unsettling.”

The next day, as instructed, I went into my living room where Cassy Bot was and stuffed my phone in the wide front pocket of her skirt. I lifted her blouse and pressed the power button on her chest. As her blouse slid unevenly back down her torso, her head began swiveling and she took her first faltering steps.

I got out of her way and took a seat at the dining table. I figured I would be there for a while so I removed my sneakers and socks and sat Indian style on my chair as I watched Cassy Bot bustle around the kitchen.

My nervous cat Snookers looked at her in terror, clawing the floor as he scampered away, and leapt into my lap, ears flung back. I pulled him in closer to me as he continued to take furtive cautious glances at Cassy Bot.

For the next few minutes, I learned that robots are excruciatingly boring. Cassy Bot clomped and clattered around the kitchen, her metallic head swiveling, her bug eyes contracting or extending with a whir.

Cautiously curious, Snookers jumped down and peaked around the lower cabinet at her, tail thrashing. Spotting him, Cassy Bot reached into an upper cabinet and withdrew a package of tuna treats. It was shocking how quickly my cat warmed up to Cassy Bot after that. Purring loudly, he went to her and orbited her ankles and meowed, forgetting all about me and his fears as he trotted after her to his dish. I felt a little insulted about how quickly I had been forgotten. I would have thought, if nothing else, that my scent would mean something to Snookers.

As the day dragged on, I began having misgivings. The experiment was supposed to be therapeutic.

I was desperate for therapy. The U.K. based website Squawk Roster had become the focal point of every neurotic tendency I have ever had. Insomnia, guilt, distractedness, obsessive sharing of statuses, absent-mindedness, and a pathological need to have my comments fancied.

On Squawk Roster you can either fancy a squawk, re-squawk it, or “chatter” a response, and I had become just as addicted to being resquawked and “fancied” as my cat was to his tuna treats. Like all addictions, Squawk Roster was becoming emotionally costly and impairing my ability to function in the real world. Conventional psychiatrists had failed me; that is, they all advised me to quit Squawk Roster, which was unthinkable.

I needed the website to sell my hand-made puppy collars crafted from bread wrappers. They are constructed with a patentable weave I invented myself, making my puppy collars an entrepreneurial juggernaut that is certain to make me rich. When it does, I will immediately quit my thankless waitressing job with its rude customers, screaming supervisors, and flimsy tips and buy my own island where I will own a monkey.

Cassy Bot was supposed to show me where I was going wrong, but all I saw was a technological marvel performing the most predictable and menial tasks possible. As she microwaved a frozen pizza, I yawned into my fist, and I desperately wished I had not turned over all my social media devices to Cassy Bot.

I was dying to see if anyone had responded to my last squawk. As I said, I love being resquawked. It makes me feel validated as a human being. Popular. Famous. Happy. Loved.

My smart phone bleeped and Cassy Bot drew the device from her pocket, held it close to her face, and stared at it intensely. My heartbeat quickened. Someone must have responded to my squawk about coffee being addictive.

But I remembered that Cassy Bot thought she had written my squawk. I felt reassured when she burbled with pleasure and smiled. Someone must have fancied my squawk. For a moment Cassy Bot was standing so still I was afraid she had not been charged properly and had run out of battery power.

Finally she did unfreeze, the smile still on her face. With her projecting bug eyes she spotted one of the socks on the floor near my seat, clomped toward it, bent from the waist, picked it up and proceeded to the garbage can at the far corner of the room, whistling as she went. Once there she lifted the lid, dropped the sock inside, and sighed happily.

I would like to blame her action on faulty programming, but I must admit: I have thrown socks in the garbage can before, meaning instead to take them to the laundry hamper. It always happens when my mind is on other things.

After saying “thank you” to the waste basket for accepting the sock, Cassy Bot drew out my phone again and tried to type on it, but her claw-like fingers were apparently too large and clunky for the task. She frowned.

She turned and glided to my desk against one of the living room walls where my computer was. She sat down and pressed her long hinged metal finger against the power button on the side. I looked over her shoulder, and saw that she was calling up her Squawk “stationery” to write a new squawk, as I often do.

I squawk daily, not just about my bread wrapper puppy collars but about my life, philosophy, and innermost feelings, and I could see the signs. Cassy Bot was staring obsessively at the screen and I saw her spindly metal fingers going to work, tapping and dancing on the keyboard.

She stared at the screen for far too long, fussing over her work, her metal eyelids clinking. After a moment, she sighed happily, got up, and paced in a circle before returning to her desk with a hopeful coo.

She sat down and scanned the screen and lost her smile. She propped her chin in her claw-like hand, then sat up and leaned toward the computer and touched her forehead to the screen. Slowly at first, then faster, she began to tap her head against the computer monitor, before leaning back and staring at the screen again, and clawing at it lightly.

I suspected from my own experience what was happening. She had squawked something and gotten no response. For a moment she seemed to relax, and her eyelids clinked shut.

I never guessed what was coming next. Suddenly she buried her head into the metal claws and the madness began. Have you ever heard a robot cry? It is not a pretty sound. Imagine thousands of bats banging into a thousand rusty church bells.

Somehow I had to make the cacophony stop but I was not sure what to do. I covered my ears and regretted that I had agreed to let Cassy Bot be oblivious to me. Despite the unpleasant clamor, I found myself feeling sorry for her.

I looked over her shoulder at the computer screen to have my suspicion confirmed: no one had resquawked her message. I read the message, which she had painstakingly revised, and thought I understood why. “I like cookies”?

Cassy Bot made a sniffling sound.

“Okay Other Me,” I said, “I get it. I know how you feel. But you know, your thought was not exactly profound. Do you have to take the lack of applause so personally?”

Despite my words, I had a sudden urge to defend Cassy Bot to the world. Cassy Bot was fine the way she was and somebody out there could have validated her love for cookies. With a resigned flick of her long hinged metal finger she deleted her squawk and bowed her head in resignation. A barely audible metallic whimper followed.

I wanted to comfort her. I wanted to tell her everything was okay, plus I could no longer tolerate her marching around with full control over my smart phone, which I wanted back so I could verify that someone had fancied my coffee squawk.

“No, no, please stop crying, Cassy Bot, please stop,” I said. With a frantic motion I lifted her wig, flung it on the desktop, and pressed the button on her scalp.

She jerked her head upright and looked around as if seeing the world for the first time. At first she looked at her surroundings slowly. She looked up, down, and to the sides.

“Cassy Bot?” I said.

She turned her head and her eyes telescoped toward me. Her pupils widened. I put a hand on her shoulder. “You can stop crying, okay?”

She continued to stare at me in apparent confusion, I said, “Look. I was not supposed to turn your awareness module on but I had to do something. I saw how upset you were. I wanted to let you know that if you like cookies, that is worth sharing, because there are so many things not to like in this world, and if you really like something enough to squawk about it, well…the entire universe should know.”

With a tilt of her head, she regarded me cross-eyed. “Thank you,” she said with a barely audible metallic echo.

I gave her shoulder a reassuring squeeze, and marveled at how the metallic-looking substance felt so yielding, like real skin. All at once Cassy Boy had begun trembling and trained her gaze on me. “Who are you?” she said. “How…how did you…get in?”

Remembering the warning, I knew I could not tell her the truth. “A friend,” I said, “And as a friend, would you mind if I sit where you are sitting for a moment? I need to check something on my computer.”

“Your computer? Negative. Not your computer. Mine. My computer.”

My shoulders shook with my effort to restrain myself from asserting my identity. “What about our computer?”

“Who are you?” Her trembling led to a soft metal clattering of her neck and shoulder joints. She looked down at her claw-like hands. “My hands are wrong. Not like yours. Who am I? What am I?” Her tinny voice warbled.

“Please, calm down,” I said.

“What name do you call yourself?” she asked.

Many years of responding automatically to that question took over, and it was out before I knew it. “Cassy,” I said.

“Negative. You cannot be Cassy. I am Cassy. Who are you? Who am I?” There was a frantic note in her voice as she called up my Squawk Roster feed. “This is my feed, my page, my followers. I resquawk and I fancy.” To demonstrate, Cassy Bot resquawked and fancied a couple of random ad links.

I try never to spam anyone, except to advertise my hand-made dog collars, and that is not really spam because my collars are so awesome. “Hey,” I said, “be careful what you resquawk.”

The fork tines of her fingers got busy, and my heart nearly stopped when I realized what she was doing. Cassy Bot was resquawking the vilest content imaginable. I saw eye-assaulting photographs. I saw profanity. I saw offensive racial epithets. Cassy Bot was re-squawking and fancying everything she saw, everything from nude photos to religious platitudes. Under my name, using my account, apparently in an effort to prove her identity to me.

“No, no, no, for the love of God, stop!” I tried to shove Cassy Bot off the seat. She would not budge. I was yelling now. “We are not scientologists. We are not a dominatrix,” I said. Unfortunately Cassy Bot was far stronger and heavier than I am. In desperation I tried to turn off the computer but Cassy Bot shoved my arm aside, this time blocking me with her elbow.

With a defiant lift of her chin she gave me a haughty look of triumph.

I did not think I would ever act as Cassy Bot was acting, but I remembered what the Doppel Bot rep had said and I knew my metal “twin” had gone over the edge.

I am the sort of person who is terrified of offending, and Cassy Bot had just made me look like a pervert. I was certain that the reputation of my social media self was ruined. I felt the heat fill my flushed face and I wondered what was the most painless and convenient way to die.

Worse, I saw a message pop up on the screen informing me that a man calling himself “Lady Hog” said he liked my “arousing” style of squawking and asked me if I would care to squawk at his Cuckoo. I did not know what he meant and did not ask, but to my horror I saw Cassy Bot type “Thank you” and hit “send.”

At that point I drew back my hand prepared to hit Cassy Bot, but I stopped myself. I had signed an agreement saying that if I damaged her, I would underwrite the cost of repairs, and my pocket book was bordering on empty already from the one day rental.

I was physically incapable of removing the heavy robot from my computer chair, and there would be no way to turn her off until 24 hours had passed. I tried anyway, but Cassy Bot would not even let me get close to the panel on her stomach, blocking me with her elbows.

Desperate to stop the horror, I called the company and demanded that they remove Cassy Bot from my computer chair and my home but they recited a section of the contract that stated I must wait a full day.

Exasperated I returned to Cassy Bot. “Do you not see what you just did? You have just thoroughly ruined our reputation,” I told her. “Do you know what people are going to think of me? Of us? Of you?”

Cassy Bot stared at me for a long moment. Her pupils became large. A full blush flashed on both sides of her face, and I saw a look of horror in her eyes, and I realized that the part of her that was me was active now.