Andrew Skurka's Blog, page 31

December 26, 2018

Spiderwoman’s KCHBR Tips || Section 6: Monarch Divide

Spiderwoman thru-hiked the Kings Canyon High Basin Route in 2017 with her partner, The Brawn. These are her “tips” about the route, a term that does not do justice to their comprehensiveness and detail. The information has been split into eight posts to improve readability:

Introduction

Section 1: Tablelands

Section 2: Great Western Divide

Section 3: South Fork Basins

Section 4: Cartridge Basins

Section 5: Ionian Basin

Section 6: Monarch Divide

She has shared all of her photos from her trip, available here.

Wind whips through a larger-than-life amphitheater

Simpson Meadow Trail

I ate a nice big breakfast. Our food bags were full again, so I was back to my normal, stick-to-the-ribs pot full of energy. By the time we got to the “small trailside campsite at Horseshoe Creek” (which I thought was kinda big), I was feeling sick to my stomach. The problem was obvious – I’d eaten more than my stomach wanted to digest, so I knew it was just a matter of time and I’d feel fine. Skurka’s head’s up that there’s no water until “8 miles and 4000 vertical feet of climbing away” had us stocking up on water out of the creek. Not wanting to run out, I decided to carry 3 liters.

And what a mistake that was. I didn’t drink a drop of water until after setting up camp at State Lakes. It was a complete cluster to have humped 3 liters of water up there while my stomach was hurting and I was faux vomiting from the pressure of my hip belt. But how funny. You have too little food and you suffer. You have too much food and you suffer.

The trail does indeed “climb aggressively” in the first part of the 8 mile walk to State Lakes. We ascended 1000 vertical feet per hour, almost like clockwork, and took short, but much needed, breaks at each interval. There were several inviting places to camp along the way. If I were to do this section again, I’d try and set myself up to climb 2000’ish in the evening, dry camp at one of the lovely spots along the way, and finish the ascent in the morning. The view is wide open for so much of the climb. It would be a real treat to enjoy the evening and morning lightshows from up there.

Prostrate, thick-stemmed shrub. Old growth? The things we get to contemplate while traveling 1 mph.

Goat Crest

Emily and her ponies were just finishing their morning packing as we walked up the “use trail” into gorgeous Glacier Valley. I took a liking to one of the mules and he let me pet him until my hand was as black as he was. Emily understood the attraction; turned out he was her favorite. She stopped what she was doing and patiently answered all my questions. I had to reign myself in though because 3 or 4 or 10 new questions would bloom for every 1 answer she gave. I love learning about subcultures and I love women. But I knew she was on the clock so I wrangled my enthusiasm and self away.

Tiny delicate frogs call this meadow home. Ribbit.

Skurka’s instructions for reaching “PR-65 Goat Crest” from “PR 63” are spot on. Our only hiccup was a challenging little scramble as we made our way up “Slabs + chutes” on the “valley’s east side” to “Lake 10,429”. It’s an uncomplicated stroll over and up to “PR-66 Grouse Lk Pass”.

A typical rhythm. ID’d this tucked away pass with map/compass a few hours prior. Getting ever closer.

Ah, Grouse Lake. That lake is so meaningful to me. Grouse Lake marked my first camp on my first thru-hike of a route. Stepping off Copper Creek Trail with Josh “Buddy” in August of 2010…picking our way around and over granite slabs…trying to avoid crushing wildflowers and being dismayed that that would be impossible and then feeling sad and concerned and wondering how in the world do you walk on a carpet of wildflowers without beating them up?…and following our bearing up a rolling horizon of rock and trees until, like a magic trick, a lake appeared. Our lake. And we found it with a freaking map and compass?!? I was hooked.

Some people get baptized in a lake. I got baptized by finding a lake.

Skurka writes that there is a “horse trail” that will get you to Copper Creek Trail. His instructions are spot-on. We used it. In reverse, the spot where it leaves Copper Creek Trail is obvious. It’s cairned and there’s a well-worn use trail at the intersection. I don’t remember it from my 2010 and 2011 walks up Copper Creek Trail – I wonder if it was there?

Grouse Lake was hoppin’. There were lots of folks camped there, and the several we met were neat to talk with. One couple who’d just attempted the Bailey Range Traverse in the Olympics rode up on mules in order to save their energy for the section of the SHR they were starting. Another man from a trio who were also starting a cross country route was kicked back in a full-on chair. After shaking off my initial surprise, I showered that chair with so many compliments it would have blushed if it could. I love having my thinking challenged by alternative approaches, my paradigm expanded by diversity.

I’d always been curious what camping at the established site (with bear locker and stream) just below 8000’ along Copper Creek Trail would be like, so it was neat our timing let that happen. Despite passing lots of folks on the trail, we had it all to ourselves. It’s on a hill, but there are lots of platforms that have been stamped level. It was a nice night.

Striding it out on trails and backroads for the next couple days didn’t hurt our feelings any

Head’s up. Small black flies were borderline unbearable the next morning. They appeared below about 7000’. A head net was key because they wanted IN…corners of the eyes, nostrils, ears, mouth. The other 2 places we were hounded by them was walking down the Middle Fork Trail as we neared Simpson Meadow, and then from Cedar Grove up the first half of the Don Cecil Trail.

We got a quick hitch from Roads End down to Cedar Grove. Agnes, the founder of Eastern Sierra Conservation Corps, had just dropped a group off and joked that it didn’t seem right not to pick us up since she had a big empty van. She told us all about her work and I swooned at how focused it is on female empowerment and creating opportunities for underrepresented populations. She knew Emily the packer and then over this winter, listening to the She Explores podcast, I was like Agnes! I know you! Such a small world.

But it gets better.

An hour later and we were sitting on the upper deck outside the café, stomachs full, planning our next errands: laundry, showers, and walking back to the Ranger Station for our resupply box. A man walked up. He had kind eyes, was squeaky clean, and was clearly intent on starting a conversation. He commented on my ice axe and maps and we invited him to sit. Very quickly, startlingly quickly, he cracked me open and had me telling him ya, we’ve heard of KCHBR, we’re enjoying the heck out of it right now! (I rarely talk about walking a route while I’m out there. On my 2010 SHR, a random dude hauled off and yelled at me on Mather Pass, saying I was lying, that I surely hadn’t just descended Frozen Lake Pass. I was speechless in front of the crowd up there. I didn’t push reasoning with the poor guy cause his ego was obviously unstable. That’s just one of a few strange examples. It’s wayyyy better to be incognito.)

I told him I was surprised he’d heard of KCHBR with it being new and all. He said it was because he was following someone’s blog, and he must’ve mentioned her first name, Katherine, because when I asked what her last name was, he gave me a look. An almost stern look. He slowly said Cook, then finished with, are you Spiderwoman and The Brawn? My jaw dropped. We really looked into each other’s eyes this time. We had exchanged several emails in the past, and here we were meeting in real life for the first, most blessedly random, time.

Philip had reached out to me via email a couple years prior because he and his lovely wife Helen, who had just joined us at the table, were planning on doing a section of the HDT and he’d found my Tips online. They were here in Cedar Grove for some section backpacks of KCHBR and the SHR. It turns out we are both big fans of Katherine’s writing and we sat there jockeying for who’s the most awed by her physical and mental prowess in the wilderness.

I was so stoked to hear she was just starting KCHBR (which she was capping off her SHR and SoSHR thru-hikes with – a feat that shows she possesses elite-level stamina), and that she and Philip had the technology to communicate with each other out there, because I wanted to pass on some beta, particularly about King Col, Should-Go Canyon, Dumbbell Pass, and Amphitheater Pass. (Spoiler – Katherine made it over King Col! It was so cool finding that out. I was so happy for her, and highly valued hearing a first-person account of the changed conditions up there after a bit of time passed since our encounter with it.)

It was getting late. Helen kindly drove The Brawn to pick up our resupply box. Intuiting we had lots to focus on before sunset, Philip and Helen said their good-byes. I’m looking forward to the next time we get to say hello again, share a round of hugs, and hopefully share some special trail time.

Glamour shot of my power plant framed by Kings Canyon in the background

After sorting through our resupply box, we some odds and ends we wanted to ship home. Since the closest PO is at Grant Grove, a 30 mile drive away, it was time to get creative. I asked a friendly young cashier if she had any brainstorms for us, and since she didn’t, she offered to mail the box for us since she was leaving the next day to catch a plane. I thanked her profusely, gave her cash for postage and to treat herself to a gift on us, included a little note with repacking instructions and our address, and let her get back to work – this all went down lightning-fast because people were waiting in line behind me.

We showed up to long lines at the laundry/shower building. Shoot! It was decision time. It’d be dark by the time we finished. Instead of dealing with the hassle that would be finding a place to camp in the dark, we donated our brand new bottles of laundry soap/shampoo/conditioner/body soap (and shower tokens that the custodian had gifted to The Brawn while the building was closed for cleaning earlier) to the same custodian and left. It was a beautiful and cooler time of day for a walk up the Don Cecil trail anyway.

Not knowing what the next day had in store in terms of water, we grabbed plenty from Sheep Creek. You can access water where the trail crosses it on a pretty stone bridge; it’s a small waterfall here. We walked steadily uphill on great tread and got to mingle with oaks, my favorite tree. Their graceful reaching limbs were showcased against the backdrop of a strikingly pink evening sky. It was a gorgeous combination, but the burrowing black flies were bad enough for head nets again and the netting unfortunately detracted from the sightseeing (and breathing).

Then it was pitch dark and we walked by head lamp. We got into an area that looked like it must’ve been a mess of blow downs. There weren’t too many to crawl over or around though. We weren’t sure where or when we’d find campable terrain, so when we topped out (when looking at a Tom Harrison map this is where the trail ends and road 14S11 begins) and found a huge flat area we were relieved and more than ready to pitch our tents.

We followed cougar tracks down gravel 14S11 the next morning and quickly came upon very nice flowing water. There was a lot of sign of development/large equipment activity up there, like maybe underground cable was being laid? The activity looked fresh enough that we commented that thank goodness it was a Sunday. We had the place to ourselves. It may have been dusty and noisy otherwise.

There were some side roads to avoid as we made our way down toward Horse Corral Meadow – staying on our main road was obvious though. The turn onto gravel 13S12 was also obvious because there was a sign for Sequoia High Sierra Camp. That windy, uphill road terminates in a large, well-used parking lot. A trailhead sign welcomes users to Jennie Lakes Wilderness, and a posted note warns that for some perturbing, unknown reason, trail signs were being stolen, so carry a map and double check yourself at trail junctions.

After walking up that trail for a short bit, the left turn toward the High Sierra Camp is obvious. We stayed right, and several miles and trail junctions later, eventually walked over JO Pass and camped at the established site at the junction with the trail that heads east to Twin Lakes. Walking on a path all day was so relaxing. We talked with nice people, enjoyed big trees and flowers, and most luxuriously, got to zone out.

I figure it was approximately 28 miles to walk from Cedar Grove to the use trail that leads up to Silliman (just shy of Lodgepole). We linked the Don Cecil Trail with gravel roads 14S11 and 13S12, then walked through Jennie Lakes Wilderness over JO Pass and rejoined KCHBR at the use trail. Tom Harrison Maps were great: Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, Mt Whitney High Country, and Kings Canyon High Country. There was plenty of water, it was pretty, and I was glad we did it. I recommend it as worthwhile if you have a desire for even more variety while you’re in the area, to stride it out on a couple dozen quick miles, to make KCHBR into a loop, and to ease transportation logistics.

The post Spiderwoman’s KCHBR Tips || Section 6: Monarch Divide appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

Spiderwoman’s KCHBR Tips || Section 5: Ionian Basin

Spiderwoman thru-hiked the Kings Canyon High Basin Route in 2017 with her partner, The Brawn. These are her “tips” about the route, a term that does not do justice to their comprehensiveness and detail. The information has been split into eight posts to improve readability:

Introduction

Section 1: Tablelands

Section 2: Great Western Divide

Section 3: South Fork Basins

Section 4: Cartridge Basins

Section 5: Ionian Basin

Section 6: Monarch Divide

She has shared all of her photos from her trip, available here.

Never mind the roaring chaos underfoot. Keep your eye on the prize.

We skipped Ionian Basin due to Skurka’s cautionary advice. Our less-than-perfect encounters with King Col, Should-Go Canyon, Woods Creek, Dumbbell Pass, and Amphitheater Pass were still fresh in our minds. Connecting our steps via the Middle Fork Trail still gave us that special brand of satisfaction that a thru-hike brings. We also got to see the very pretty gorge that the Middle Fork passes through, meet a trail crew (who, upon seeing us, expressed satisfaction with feeling their labors were justified – it’s an overgrown trail, especially up near the JMT, and apparently infrequently used), and later run into Emily, the packer out of Cedar Grove Pack Station. She’s the epitome of the capable woman. I hope she’s still at it in 50 years.

When water finds the low point and just pushes its way through

We passed a kayak stashed way up in the brush that looked a lot like one of the two we saw on our way to resupply out Bishop Pass a few days ago.

It was crazy. We had been taking a break on a slabby bank of the Middle Fork when out of nowhere popped a couple kayakers. We got to watch them scout the drop they were about to make. Kicking back in my front row seat, I whooped and clapped at each of them as they got to show off their whitewater skills to an appreciative audience. They were grinning and even managed to briefly look straight at and wave at me – the brief connection made me feel giddy as a kid. Then the questions started, where did they come from? Where did they launch? How did they get their kayaks and gear down? Is this normal, or especially adventurous?

proper

Back to the Middle Fork Trail. The kayak was tucked up off the trail, kinda hidden but not really. Hmmm. We wondered what that meant? One person kayaked all the way, while the other walked out? We hoped the guys were okay. Really hoped they were whole and okay. The whitewater we’d been passing did not look like child’s play.

We camped on the bank of the Middle Fork Kings River, just a mile and change upstream of Simpson Meadow. Skurka warns this is the “Most difficult ford of the entire route”. We had been super curious (and on edge) about this ford since before leaving home, so we were stoked to check things out in person.

We found a campable area, dropped our packs, and made a beeline to the water’s edge. Well well well. Crossing the Middle Fork would have been do-able after all. Don’t get me wrong – the crystal-clear water was moving for sure, and the round rocks on the bottom were big enough that I would have been appreciating having The Brawn to balance with while crossing. The depth was hard to gauge – probably above my knees? But nothing about it was treacherous. And it could have gotten even safer: wait for a morning crossing and do it down in Simpson Meadow. Damn!

Curiosity satisfied. I might have said a bad word. Maybe two.

The uncertainty of the safety of this ford was the primary reason I skipped Ionian Basin. We’ll never know how the rest of Ionian Basin, and descending Goddard Creek, would have gone for us. That’s the thing about accidents. We’ve probably racked up more than one near-miss in the course of our lives, and we’re none the wiser to them. But if I was to bet, I’d bet it would have gone just fine. Shoot!

But that’s one of the most wonderful parts of this lifestyle: the object of your affection will be there another day…unless it’s strip mined, or melted away, or submerged, or mismanaged/fire suppressed, or sold to Extractionists (as The Brawn calls them), or turned into a fee-heavy paved-over permit-driven Humans First! wonder of the world that selects for people with financial, transportation, pre-planning, and digital means… okay, big breath. Back to our walk.

The post Spiderwoman’s KCHBR Tips || Section 5: Ionian Basin appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

December 22, 2018

Just released: CalTopo app for Android

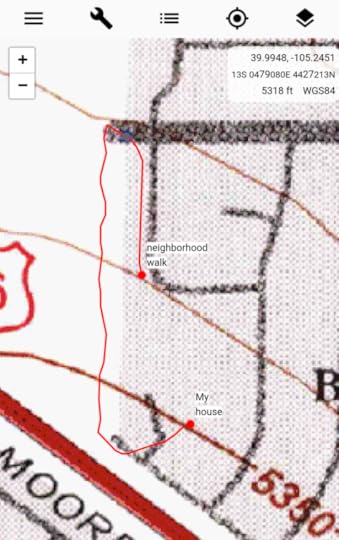

Screenshot of the CalTopo app, displaying some of my Yosemite High Route data.

The website CalTopo has been my go-to mapping platform for four over years. I primarily use it to make and print topographic maps, including for all of my guided trips and high route guides. It has come a long way since I began to use it, with regular improvements to the user-interface and imagery database.

Historically, the usefulness of CalTopo has stopped at my office door, however, because it had no off-line mobile functionality, which is essential for field use. Instead, I typically export my route data to GaiaGPS, an app that allows me to download my data for off-line use and that gives my smartphone the functionality of a conventional handheld GPS.

Today, CalTopo released its own app, creating a seamless office-to-field and field-to-office experience. It’s available for Android users only; get it at the Play Store. The founder of CalTopo, Matt Jacobs, tells me that he’s shooting for an April release of the app for iOS.

The app is free, but a CalTopo subscription ($20 to $50 per year) is required to download map layers.

By Matt’s own admission, the app is still buggy. When he sent me a download link last night, for example, I was able to successfully install it and to link my CalTopo account with it, but then it crashed and kept crashing. That issue has since been fixed. On the CalTopo blog, Matt writes:

“The app is still in development, and this is a beta test. There are probably some major bugs related to specific platforms or android versions that we haven’t caught yet, and some obvious functionality is missing, such as the ability to place a marker at your current location. We’re releasing this not because it’s a finished product, but because we’re at the point where we need testing and feedback from a broader audience.”

A track of my route during an evening walk. The track was displayed live back on the website, one of the neat features of this system.

Questions about the CalTopo app? Leave a comment.

Disclosure. Matt comp’d me a Pro subscription when it become a paid service. If he didn’t, I’d happily pay for it — it’s a great platform, and I admire how he has developed it. I have no financial interest in CalTopo.

The post Just released: CalTopo app for Android appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

December 21, 2018

Admission: Yes, I sleep with my food

Sunset in the Yukon Arctic. My food was stored in the clear OPSAK at the front of the shelter.

In a post yesterday I shared my recommended food storage techniques. Some readers responded skeptically to my fifth method — sleeping with it — so I thought I’d discuss it more fully. I’m intentional about when and where I’ll do it, and I don’t have a death wish.

First, a disclaimer

Sleeping with your food seems riskier than storing it further away from camp. There’s little (or no?) data to support that assumption, but it seems intuitive. If you decide to sleep with your food, it’s on you.

In this post I’ll explain my approach, but I’m not recommending that you do the same, nor can I guarantee that you’ll have the same results.

Defining “sleeping with food”

If I’m sleeping in an enclosed shelter, I’ll keep my food inside it. If I’m cowboy camping, I’ll sleep on it or immediately next to it. Often I use my food bag as a knee rest, to relieve pressure on my back; it can make a decent pillow, too.

The food cannot be left on the ground “nearby.” From the perspective of an opportunistic food thief, unattended food is open for the taking. Wildlife look for easy calories, and only the most brazen and desperate bears and mini-bears would try to take food that’s obviously in my possession.

Cowboy camp on slickrock in Escalante-Grand Staircase. My food bag is the clear bag on the far side of my sleeping bag and bivy.

Why do I sleep on my food?

When the conditions are right, I always sleep on my food. It’s the lightest, least time-consuming, least fussy, and least expensive storage method. In other words, it’s the most convenient.

When & where will I sleep on my food?

If I decide to sleep on my food, three conditions must be met:

The land agency must not require a specific storage method;

The risk of a bear entering my camp is acceptably low, and ideally zero; and,

The risk of rodents in camp is also low, and ideally zero.

If the land agency requires a specific method, then I’ll adhere to the regulation.

If I’m not comfortable with the bear risk, I’ll use permanent infrastructure, a hard-sided canister like the BV500, or a soft-sided bear-resistant sack like the Ursack Major.

If I think that rodents may occupy my camps, I’ll plan to: hang my food out of their reach (a.k.a. “rodent hang,” which will not be out of reach for a bear, because the food will be only a few feet off the ground); or to use a soft-sided rodent-resistant sack like the Ursack Minor.

In areas where canisters are not required and where I’m not concerned about bears or mini-bears, I will sleep on or next to my food. This Wind River Range campsite was several miles off-trail, at treeline, and showed no signs of previous use.

Assessing risk

How do I determine the risk of bears or rodents? I rely on personal experience and research. What have I observed before, and what am I being told by area guidebooks, online forums, trip reports, rangers, and the local news?

I would consider an area to have low bear risk if:

Few or no bears live in the area,

Little or no bear sign has been seen (e.g. prints, scat, root digging),

I’m camping far from seasonal food sources (e.g. berry patches), and/or

There are no recent reports (and, ideally, no reports at all) of bears stealing food from backpackers or campers.

Assessing the risk of rodents is more straightforward, and also less consequential:

At high-use and moderate-use campsites, I expect mini-bear problems.

At low-use campsites, it’s rare but possible.

At virgin campsites, I don’t recall ever having a rodent issue.

The softest bed of moss on which I’ve ever slept, along Alaska’s Lost Coast.

Personal results

I haven’t kept count, but I’ve probably slept with my food for more nights than all other overnight storage methods combined. This includes many thru- and section-hikes of long-distance trails (e.g. AT, CT, IAT, NCT, PNT, PCT, CDT), a little loop around Alaska and the Yukon, and weeks on the Wind River High Route and Pfiffner Traverse.

I’ve had a few bears enter my camp, each time in Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park (where hard-sided bear canisters are generally required, and always required for commercial groups). I’ve had far more problems with mini-bears, especially at high-use campsites in popular areas like the AT and in National Parks.

If I repeated these trips, I’d do things differently in some cases. In the past fifteen years, the risks, regulations, available methods, and my thinking have changed or evolved, and will continue to do so in the future.

Have a question, opinion, or experience with sleeping with your food? Leave a comment?

Disclosure. This website is supported mostly through affiliate marketing, whereby for referral traffic I receive a small commission from select vendors, at no cost to the reader. This post contains affiliate links. Thanks for your support.

The post Admission: Yes, I sleep with my food appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

December 20, 2018

Spiderwoman’s KCHBR Tips || Section 4: Cartridge Basins

Spiderwoman thru-hiked the Kings Canyon High Basin Route in 2017 with her partner, The Brawn. These are her “tips” about the route, a term that does not do justice to their comprehensiveness and detail. The information has been split into eight posts to improve readability:

Introduction

Section 1: Tablelands

Section 2: Great Western Divide

Section 3: South Fork Basins

Section 4: Cartridge Basins

Section 5: Ionian Basin

Section 6: Monarch Divide

She has shared all of her photos from her trip, available here.

Creeping along the thin melted out edge between a lake below and icy snowfields above

Cautionary Advice

Boy did we read Skurka’s cautionary advice at a sensitive time. We were in the middle of rationing our way to running out of food, an impassable cornice had blocked King Col, we had a physically challenging time descending Should-Go Canyon…and had high anxiety not knowing if it would even go near the bottom. The large snow plug choking all but a sliver of the north side of Gardiner Pass was a surprise, fording Woods Creek would have been frightening if the guys hadn’t found the tree to cross on, and since before even leaving home I was preparing for our upcoming descent of Goddard Creek and crossing of Middle Fork Kings River with a very, very risk-averse mentality…to the point of even promising my events-aware family that we’d absolutely turn around and retrace our steps back up to the JMT if high water made either too risky.

The backpackers’ deaths just a couple months prior while attempting Sierra fords weighed heavily on all our minds. Since sketchy fords are my #1 fear out there, the news of their deaths really hit home and made me sad when I thought about how they must have felt in those awful, out-of-control, final moments.

So when, safely nested in my tent that evening, protected from the bzzzzing mosquitoes and innocently studying the data for the next day, I was suddenly confronted with Skurka’s warnings: “most dangerous”, “most isolated”, “uncontrollable factors e.g. high water and extensive lingering snow that can make it completely impassable”, “unless earlier portions of the Primary Route have gone flawlessly”…I reacted with an unequivocal, WHAT THE, nope, not this year, we’re out.

I got out my Tom Harrison overview maps, quickly figured out plan B, and ran the new plan by The Brawn. He agreed it was prudent to come back another year, a low snow year!, to experience what we were about to miss. So this year, after resupplying and walking back in over Bishop Pass, instead of turning north on the JMT at LeConte Ranger Station, we’d instead turn south, retrace a quick couple miles, then turn west onto the Middle Fork Trail.

We’d rejoin the route at Simpson Meadows (this is the 3rd option in Skurka’s list of 4). The Brawn couldn’t have cared less – he, as always, was doing a described route to humor me. If left to his own devices, he’d be scrambling all over tarnation, an overview map stuffed in his pocket, following whatever line seemed most intriguing and challenging at the time.

Case in point. The Brawn making a bee line in lieu of a mellow line. Skill building opportunities for me for sure.

I was disappointed though. That disappointment didn’t even come close to the level of caution I was nursing, though. So it was all good. But still, for a goal-oriented person that had a burning curiosity to move through the ominous looking terrain that I’d seen from a distance on my previous SHR hikes (gazing northwest while standing on Windy Ridge), it was a loss, and I felt it.

Besides that big decision, we were at an even more immediate decision point. Would we bail out the JMT near Bench Lake or South Fork Kings River tomorrow morning, or would we continue on the route and mos def go hungry?

Our textbook perfect day over White Fork Creek Pass had us hoping for the best with upcoming Cartridge, Dumbbell, and Amphitheater Passes. Plus, it would have been too much of a blow to give up even more of the route, so Cartridge Pass, here we come.

Cartridge Pass/ Lake Basin

Crossing South Fork Kings River was just fine. We reached its bank before the morning sun did and the smooth, cold water flowed tranquilly by.

Finding “PR-40 old Cartridge Pass Tr” was and wasn’t tricky. You walk through nondescript forest here. Fortunately there are subtle cairns that lead the way (look close, you can see them in a few pictures I included). We walked slowly, spread out, methodically kept track of whatever cairns we could spot, and would feel very relieved whenever we’d spot the next breadcrumb.

Skurka says “also look for two small meadows”. Head’s up to this good guidance because old trail tread was visible here and shot up the hill out of a meadow (I included a picture of this spot). Cairns showing you to turn north were here as well.

Expect to lose the trail as you zigzag your way north up the steep grade. It’s no problem, you’ll just all of a sudden wonder is this the trail? It won’t be (it wasn’t for us several times). So just backtrack 20 or so feet and try a different way. No problem whatsoever.

“It contours sharply at 3140 meters” – definitely watch for this contour to the west. You abruptly change from walking steeply northward to turning west and walking flat ground.

From the first (largest) lake you reach up to “PR-41” Cartridge Pass, old trail tread was mostly obvious and the alpine setting was exquisite. It was really neat to visit part of where the original JMT traveled.

It was slow through here. Taunting fish and a showy display of wildflowers demanded full attention.

When planning your walk up to “PR-43 Dumbbell Pass” from Lake Basin, definitely set your course so as to use the “Sandy gravel ramp, tundra”. We made the mistake of approaching “PR-43” on a westward contour that had us doing slow and sketchy moves across a steep slope made of nothing but large blocks of unstable broken down mountainside. We’re smarter than that. I’m not sure what happened there, other than to say we didn’t know the slope was going to be so unstable. Just stay low enough through Lake Basin to line up with the obvious “Sandy gravel ramp, tundra” and enjoy what looked to be a sweet little walk up to “PR-43”.

But! Our mistake turned out to be a blessing in disguise. The extra time and exertion we gave to that steep talus slope tired us out, the weather was deteriorating, and the constant uncertainty of finding campable spots when they’re needed made us stop for an early camp at the lake just below Dumbbell Pass. Thank goodness we did, because there wasn’t much campable terrain for quite a ways, perhaps north of Amphitheater Pass? Do know that I’m picky about campspots though, and we did have a lot of snow that might have been obscuring good spots.

This is why those cheeseball posters use scenes like this to inspire tranquility, serenity, oneness. Cause they do, yo!

Just FYI. Our camp spot at the lake just south of Dumbbell Pass was outstanding, and our next camp, “Good campsite” near “A-AMP-02” was excellent, too.

Dumbbell Basin

I think my obsession with cross country routes comes from the thrill of figuring out where to go next. A special brand of intimacy develops between you and your environment, map, compass, and brain.

It was a quick ascent to Dumbbell Pass the next morning. And surprise surprise, it was covered in snow. The snow was absolutely, full-on, I-kid-you-not, frozen solid ice. Our microspikes helped on the broad, flat pass, but were useless once we had to make our way down the rapidly steepening decline. My ice axe would almost certainly not have arrested a fall. It just would have been a near-frictionless hell sail to the talus heap down below.

We would have loved to descend on the west/left side but couldn’t make it over due to the imminent fall risk. So we found a barely hospitable place in the large talus on the east/right to tuck ourselves in and take off the microspikes. OMG. The talus on the east/right was full-on, I-kid-you-not, no exaggeration, in a word: lethal. It was the most unstable talus I’ve been on, ever. Descending the talus on the east/right is not safe; it is not an option. It was so dangerous we had to bail very soon after trying it out. We had just gotten past the steepest snow section though, so when we got back on the icy snow we were less fearful of the consequences of a fall.

You travel west from “PR-44” to get around “Lake 11,108”. We had more icy snow obstacles to get through as we part “talus-hopped”, part used microspikes and shared my ice axe, to reach the “lake’s west shore”. Nice warm sun rays were finally thawing us out and getting around the lake had turned out to be a fun little obstacle course. Plus, I got to watch The Brawn use an ice axe for the first time! (His first swing: he drove the pick down through a thin layer of snow and clanked off solid rock. Oops.)

Learning on the fly

Alternate: Amphitheater Pass

It was a nice walk up toward “A-AMP-01 Amphitheater Pass”. We were relaxed and happy, feeling like we were on schedule to make it a ways up the JMT that afternoon, aka make it closer to food, aka make it to food by tomorrow! That would only put us one day behind our original schedule, and would mean we were accomplishing what I’d planned back at the camp just before Bench Lake (the point of our last bail out option). We were on-track and things were looking great!

Until they weren’t. Again.

Our expressions turned slack-jawed and wide-eyed as we walked to the north edge of the pass and ran smack into a broad carpet of snow. WHAT THE! Another one? A large cornice blocked Amphitheater Pass. Deflated. Flashbacks of King Col. Can we get around and down? Backtracking was a disgusting thought.

Yep, I couldn’t agree more, that there pass has a snow plug in it

We scouted up to the west/left to check things out. To our great relief, the west/left side was open for business. It wasn’t easy scrambling. It was slow, loose, and steep. There were a couple spots near the top where we spotted each other on down climbs of short sections of smooth granite. As soon as the snow looked safer we got off the rock and enjoyed a fast cruise to the bottom.

Got around the snow plug on the right side of the photo

Our timeline wasn’t looking quite so rosy, but we didn’t have to backtrack!!!!!!!!!!!!! Moving forward was glorious.

Skurka’s notes did a great job leading us around Amphitheater Lake. The “flat area with grass and willows” was very obvious. From there, we just contoured on large stable talus until we could see a route down the “ledges north of the lake outlet”.

An interesting (that’s being diplomatic) thing we noticed along this walk so far was that mosquito presence varied widely. There were some places that were basically mosquito-free, and others that were hit hard. I couldn’t see an obvious pattern or explanation in terms of elevation or water content, it just seemed to be a random variation.

Well, the descent from the “flat area with grass and willows” on down was teeming with mosquitoes. They were horrendous. Usually you can walk your way to sanity, just suck it up and deal with them on little pit stops, but this time it was ugly. No matter how fast we moved, swarms of at least 20 mosquitoes buzzed around our heads like halos. They were diving for our mouths. We couldn’t stop for a snack, you couldn’t have paid me to pee, and I exhausted myself trying to out-walk them.

Walking on broken down mountainside is an inherent, and often stupid fun (when the large chunks are stable, as they are here), part of traversing a high route

So after picking “up the old trail” and reaching the “great camping on the bench”, I made a compelling case for us to stop: the mosquitoes were driving me crazy and I needed the sanctuary of my tent. We’d had a physically vigorous day. Who knew how long it would take to reach the JMT. And last point, this campsite was amazing…and much better than a potentially crowded and bear-harassed campsite along the JMT.

The Brawn was reluctant (the case our hungry stomachs had been making was pretty compelling, too) but was on-board by the time we finished filtering water. The poor guy didn’t have a head net. Skeeters swarmed his face and neck while we filtered to the point that we both had to swat them away. Buying a head net moved to the top of the to-do list. Our resupply box was at Parchers, so an unplanned trip into Bishop, a place chock-full of restaurants and fresh fruit, was going to be necessary. Shucks.

The next day saw us walking with a purpose: food was our only mission. We’d eaten our last dinner and breakfast. I had no snacks, but I did have an emergency slice of dried mango in case I started to suffer any ill effects of hypoglycemia. I knew what it was like to walk with no calorie input, and since I did it that time (albeit with tears, it unfortunately coincided with the HDT’s crux move in Coyote Gulch), I knew I could cruise on these very familiar trails. It might get uncomfortable, but uncomfortable is part of thru-hiking by definition, right!

The trail does indeed peter out. Further on, a narrow but chaotic band of downed “fire-killed timber” needs to be negotiated just before reaching “Palisades Creek”. I made it into a little game and tried to see how close I could get to the creek without touching the ground.

We easily found a couple old logs to use for our Palisade Creek crossing. Part way across, I got my left pole stuck in the tangled mass of dead limbs (I included pictures). Creatively balancing on things like trees and rocks in order to safely cross rushing water is one of my favorite challenges out there. I get all calm and peace-filled because of the concentration that’s required to stay safe. But not being able to extract my pole threw me for a loop, and the subsequent loss of balance I felt when I shifted my gaze away from a fixed point out in front to the flowing water beneath me, exploded a detestable adrenaline surge all over me. The picture of my relieved smile as I step off the logs says it all.

The JMT was crowded. Nearly every passing group stopped us to ask how the Golden Staircase was, and to tell us how nervous they were about it. I said I thought it was pretty. That’s truthful.

Speaking of pretty, it was so exciting knowing The Brawn was going to experience that stunner of a tree along the Bishop Pass Trail. I felt like I was in on a secret, like he was on his way to walking into a surprise party. Once there, he was like whoa, check this out! He was smitten.

I love Bishop Pass Trail. I knew it was a big commitment to use it to resupply, but I chose to anyway because of wanting to share its beauty with The Brawn. It had taken him 54 years to step foot into the Sierra in the first place. I didn’t want to take any chances if it was going to take another long stretch of years for him to return.

Upon reaching Dusy Basin, he was smitten all over again. It was early evening so shadows highlighting the craggy peaks were sliding into place and puffy clouds were starting to hint at the upcoming lightshow. Smiling, he asked me to sit down for a second. He gave me hug, told me to close my eyes, and started to put morsels of food into my mouth. Fireworks went off in my brain. This was so totally unexpected, so totally sweet. I couldn’t believe the things he was feeding me – things I’d plowed through in my own food bag while we were probably still with Kelby. This also meant he’d been rationing even more strictly than me. He’s so Brawnly. Looks like 2 can play at the surprise party game!

At Bishop Pass, I got into a long conversation with a beautiful soul (and math teacher) from SoCal. She was super inspired to start backpacking more and hopefully have that lead into thru-hiking the PCT. I stood there mesmerized by her passion, trying to send silent vibes her way, vibes with the sneaky aim of targeting whatever switches in her would be turned ON for making firm plans for an upcoming PCT adventure. I was in her shoes not 10 years ago. Well, not the math teacher part. Thank goodness for those brains.

I caught up to The Brawn who was waiting a few hundred feet away. Neither of us thought we’d be up there so long and we hadn’t thought to put on warm layers. Strange. I’m usually diligent about layering up on breaks in order to prevent the chill. And now we were going downhill. Brrr.

At the same time, a search and rescue was happening on adjacent Mt Agassiz. Helicopter overhead, brightly-coated people zipping up the flanks on foot. It was going to be a cold night. Was someone out there, unprepared, perhaps injured, alone? It made me sad.

In the fading light we set up camp below Bishop Pass. It was a long set-up, all the stakes had to be secured with rock piles. That’s fine normally, but this time I was struggling. I was cold – absolutely chilled to the bone. Once in my tent and nestled in my sleeping bag I started subtly, involuntarily writhing and moaning. It blindsided me, came out of nowhere, and took me to a place I’ve never been. I was aware I was feeling ashamed of my behavior, that a search and rescue was going on for goodness sake, but all my thoughts were coming from a detached place outside myself. It was like despite my warm layers, despite my sleeping bag, I could tell my core wasn’t going to warm up. It was like putting a cold rock in a sleeping bag and hoping the rock would warm up.

The Brawn came over and I brought him inside, get this, with his boots on! Just know that that says it all. He spooned me while I writhed and soaked in his body heat. I was trying to describe to him how I felt. The best I could do was that everything ached inside, like every bone, every joint, every muscle, and to top it off, my brain felt highly involved, like any chemical or process that is normally involved in day to day pain control had left me high and dry. I had the peculiar thought is this what people feel like when they detox off hardcore drugs?

He left and came back a few times. The first time he brought dried fruit, a big baggie worth. It might as well have been a burlap sack’s worth for how the volume of food struck me at the time. He told me to eat, and he’d be right back. I tried to eat, but was having a hard time just moving my body parts due to the pain. He came back with his pad and sleeping bag. He set up the spoon therapy again and held me tight. Then he left yet again and came back with a mostly eaten bag of chips. I did have the presence of mind to comment that he’d not only eaten less than me this past week, but he’d carried more weight in uneaten food. And now, when he took it upon himself to save for a so-called rainy day, he was just giving it to me. He just held me in his typical quiet, understated manner. He was such a kind, kind hero to me in that moment.

He was cold so went back to his tent so he could seal himself into his bag. I was still chilled and suffering from body aches. I don’t know where it came from…I suspect it was from a combination of feeling ashamed at my good fortune (and being a writhing moaning wuss despite it) of being warm, intact, and safe compared to what the victim(s) of the search and rescue must be enduring…and the pain that didn’t seem to be improving…but I started to sob. It came out of nowhere. Deep sobs. Scrunched up babyface sobs. Sobs from deep in my chest. And just as abruptly, within the same minute, a warmth flickered in my chest, rose to become a bona fide radiant heat, and I dropped into a deep sleep.

We randomly got to South Lake TH on a Sunday (shuttle service was cut to weekends only by this point…uh, we’re still in August. Seriously?), and 15 minutes before the (once, maybe twice per day?) shuttle was scheduled to arrive. In other words, we stumbled into luck. That was when a shiny Toyota Tacoma pulled up. It had a professional decal on the door advertising it as a shuttle service. The driver asked if we were waiting for the shuttle, and we, looking confused, answered slowly yeah.

The rest happened in a flash: he hopped out, opened a very nicely protected rear compartment, loaded our packs for us, and held the rear door open as we loaded up. He slid back into the driver’s seat but before he pulled away I, struck by the oddness of the fancy-pants ride, managed to ask how much is it down to Bishop? I almost saw goose bumps prick the hairs on the back of his neck. He slowly turned around and with a frown asked are you so and so? We were like who?

The actual bus shuttle felt pretty fancy-pants, too, seeing it was delivering us to a long overdue reunion with food.

Why is that lake over there so familiar looking? Any SHR alumni wanna guess?

Big Thanks To

Brown’s Town Campground – lawn for pitching tents, quiet sleep, flush toilets, showers, laundry, gift shop, soda fountain, a local business

Eastern Sierra Transit Authority’s Dial-A-Ride – took us from Brown’s all the way to Vons, we used it a bunch

Eastside Sports – head net, check. Excellent customer service and selection as always

Vons – continues to be one of the best resupply selections ever, organic produce

Bishop Twin – treated us to child’s fare tickets since the only choice was a kid’s movie

Bishop City Park – free potable water, picnic in the shade, could have used Bike Share for errands if we had a smartphone to unlock them, disappointing

Dwayne’s Friendly Pharmacy – still have their Kodak Kiosk for printing/sending photos to family

White Mountain Ranger Station – for being so chill with permit details once they understood we were doing a route

Mountain Light Gallery – I met you in ’09 on my PCT hike, then never missed a visit when I was in the area, even brought my family, you always left me wonderstuck, so sad to see you go

Post Office – for sharing your counters and floor space with hikers

Food – Schat’s, Yamatani, Jack’s, and Vons for feeding us

Local man with college-bound daughter – I barely got my thumb out and you were pulling over, you made a pit stop at Parchers for our box, you weren’t even going to South Lake to begin with, you’re the best. And…my wish for you, young woman, is open doors. May you get everything you work for as you travel the road toward your ambitious career

Remember Bird and Bill? The couple we passed en route to Gardiner Pass? We had an unexpected opportunity to catch back up with them shortly after arriving in Bishop.

Not 20 minutes after parting ways with them that day a week and a half ago, The Brawn was up ahead, slowly weaving through random thickets of manzanita, keeping an eagle-eye out, trying to get back onto the rough trail, when a decidedly nonorganic object briefly passed across his peripheral vision. It was a smartphone.

He showed me his find that evening in camp and I said uh oh, I wonder how long ago someone lost it, I know smartphones are really important to people these days, let’s see what we can do once back in civilization.

In Bishop, I powered on the phone, held my breath, and broke into a relieved grin when I saw it wasn’t going to require a code to access it. I scrolled through a long list of recent calls, picked two of the most frequently made, and dialed. I couldn’t have chosen better (no credit taken, just dumb luck!). I got calls back from both the owner’s next-door neighbor and, get this, husband! And you’ve guessed already, but yep, hubs is Bill.

Turns out, Bird lost the phone while using the loo. Although she was happy her irreplaceable pictures weren’t lost forever, she most enthusiastically, and repeatedly, expressed relief from knowing she wasn’t littering. Isn’t that something! Imagine what the state of the health of our Earth’s living systems would be if Bird was in charge.

I’m so glad you got your phone back and I look forward to some hearty conversations, hearing how your new approach shoes are treating you, and sipping one of your stiff-looking, mountain-inspired drinks when we’re in your neck of the woods and taking you up on your warm offer for a home-stay someday!

The post Spiderwoman’s KCHBR Tips || Section 4: Cartridge Basins appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

Tutorial || How to store & protect food from bears & mini-bears

In areas where canisters are not required and where I’m not concerned about bears or mini-bears, I will sleep on or next to my food. This Wind River Range campsite was several miles off-trail, at treeline, and showed no signs of previous use. My food sack is the see-through bag to the left of the blue stuff sack. I often will use it as a pillow or knee rest.

You’ve set up camp for the night and cooked dinner. Now what should be done with the Snickers, salami, peanut noodle dinners, and the other calories that will sustain you for the remainder of your backpacking trip?

Protect from what?

Most backpackers seem to protect their food overnight because they’re worried about bears. In places like the High Sierra, that concern is entirely warranted.

But proper food storage is important in other locations, too, even if the bear population is low or non-existent, and even if there are few or no reports of bears obtaining human food.

Why? Because of so-called “mini-bears” — the mice, rats, squirrels, rabbits, marmots, pikas, racoons, porcupines, gray jays and other small animals that reside in popular frontcountry and backcountry campsites. Mini-bears may not run off with your entire food bag or give you nightmares, but they definitely can ruin a few chocolate bars, sometimes after first chewing a hole in your food bag, backpack pockets, and shelter.

A black bear in Bubbs Creek, Sequoia-Kings National Park

Protect what?

Anything that is supposed to go in you or on you should be properly stored overnight. That obviously includes food, but also lip balm, sunscreen, toothpaste, etc. The thinking is that wildlife may not discern between cherry-flavored Lipstick and a bag of Craisins.

I don’t protect my stove and pot, which I clean thoroughly after dinner. While they may have some residual food smell, most of my other gear does, too, and this isn’t the threshold for what should or should not be protected overnight.

How to protect your food overnight

I rely on and recommend five techniques to protect food overnight in the backcountry:

Permanent infrastructure,

Hard-sided canisters,

Soft-sided sacks,

Rodent hangs, and

Sleep with it.

The exact method I use is determined or informed by local regulations, personal familiarity, local guidebooks, online forums, trip reports, and informal conversations with rangers.

Video: Overnight food protection

I’m no longer with Sierra Designs, but this video nicely summarizes my recommended methods:

In-depth: Food storage pros & cons, and best practices

1. Permanent infrastructure

High-use areas and campsites may have permanent food protection infrastructure. For example, Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park has installed large bear boxes in 55 backcountry locations. Elsewhere, I have seen cable, pole, and cross-beam systems.

If this type of infrastructure is available, I use it. It’s effective, convenient, free, and weight-less — and it was probably installed for good reason.

A permanent bear box (lower-left) at a high-use campsite on the John Muir Trail

2. Hard-sided canister

Permanent infrastructure has downsides. It’s:

Expensive to install,

A contributing factor to concentrated use; and,

Undermined by dispersed camping.

So an increasing number of land agencies require that backpackers carry hard-sided bear-resistant canisters, including in Yosemite, Sequoia-Kings, Rocky Mountain, Olympics, Adirondack High Peaks, Canyonlands, and more.

When canisters are required, I carry one. Personally, I use the BearVault BV450 or BV500, because they offer the best volume-to-weight ratio and because I’m too frugal to spend $300+ on a carbon fiber Bearikade.

Where hard-sided canisters are required, I carry one. My personal pick is the BearVault (lower-right corner), which has the best volume-to-weight ratio among economically priced models.

3. Soft-sided animal-resistant sack

Hard-sided canisters are effective (well, mostly — they’re not idiot-proof) and they keep me compliant with local regulations, but of course I don’t like to carry them — they’re heavy and they don’t pack well.

I would rather carry a soft-sided animal-resistant food sack, which is ideal for an area where:

Bears and/or mini-bears are a potential problem; and,

Hard-sided canisters are not required.

You might think of these products as inexpensive and lightweight insurance. Two companies serve this niche: Armored Outdoor, which makes the Ratsack; and Ursack, which has rodent- and bear-resistant sacks:

Ursack Minor ($65, 5 oz), which is for mini-bears only;

Ursack Major ($80, 8 oz), which has been certified by the IGBC and is suitable for bears only;

Ursack AllMitey ($125, 13 oz), which is both rodent- and bear-resistant.

The BV500 and Ursack Major are both about 650 cubic inches in volume. But the Ursak is 60 percent lighter and is soft-sided. Which would you rather carry?

4. Rodent hang

As a substitute for a Ratsack or Ursack Minor, food can be successfully protected from rodents by hanging it. Keep it a few feet off the ground, a few feet from the trunk, and a few feet below the limb.

This is not a bear hang. An adult should be able to hang it and take it down without throwing a rope or standing on someone’s shoulders, and it can be set up a few feet from your shelter. To suspend it, use the drawstring on the food sack — or, better yet, add a length of heavy-duty fishing line, which rodent’s can’t climb.

At this established camp at the foot of the Dinwoody Glacier, I should have known that rodents could be an issue, and either hung my food or used a rodent-resistant sack. Instead, one chewed a small hole in my OPSAK food bag.

5. Pillow or knee rest

If I’m not required to store my food in a hard-sided canister and if I’m not concerned about bears or mini-bears, I will sleep on my food. I think I can get away with this because of where I backpack and where I camp — in big wilderness areas and at low- or no-use campsites. Surely, don’t try this at a Yosemite Valley campground, a designated backcountry site in Rocky Mountain National Park, or an established camp on the Appalachian Trail.

A food sack makes a decent pillow, though I prefer a pneumatic model like the Sierra Designs Animas Pillow ($25, 2 oz). As a back-sleeper, I prefer to put it under my knees, which helps to reduce pressure on my back.

To store my food I use OPSAK Barrier Bags 12″ x 20″. These bags are odor-proof, at least when new — within a few days, I bet the exterior smells like food. I still like them though: they are tough and see-through.

Discouraged: Bear hangs

You may have noticed that the classic bear hang does not make my list of recommended protection techniques. I discourage bear hangs of any variety, including the counter-balance and PCT Method. I may elaborate in a future post, but in general I find them to be:

Time-consuming, frustrating, and dangerous;

Infeasible where trees are spindly, short, or non-existent; and,

Largely ineffective against a determined bear.

I think bear hangs are akin to triangulation: they’re old-school techniques that are taught by some programs as if it’s still 1970. If you’re really serious about finding yourself, stay found, or use a GPS. And if you’re really serious about protecting your food from bears, use one of the first three methods I described in this post.

Completely ineffective: a typical bear hang on the Aspen Four Pass Loop.

Questions about food storage techniques, or have an experience to share? Leave a comment.

Disclosure. This website is supported mostly through affiliate marketing, whereby for referral traffic I receive a small commission from select vendors, at no cost to the reader. This post contains affiliate links. Thanks for your support.

The post Tutorial || How to store & protect food from bears & mini-bears appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

December 19, 2018

Program orientation: My 2019 guided trips

Atop Colorado’s Continental Divide, following the Pfiffner Traverse with views south to Longs Peak

My 2019 guiding program is coming together. A few details are still being finalized, but everything should be settled by Monday, January 7, when the open application period will begin.

For in-depth details about the trips, go here or follow other links below. This post is a succinct summary.

Guide roster

The program has always stood out for its guide roster, and that remains the case in 2019. Let me boast for a second: It’s the most accomplished and credible group of backpacking guides out there.

Leading most of the trips will be Mike Clelland, “Adventure Alan” Dixon, Flyin’ Brian Robinson, or me. Vital assistance will be provided by Mary Cochenour, David Eitemiller, Paul Magnanti (“Mags”) Justin Simoni (“Long Ranger”), and Jessica Winters (“Wildflower”).

I also made two new hires: Heather Anderson (“Anish”) and Joe McConaughy (“Stringbean”). My one worry about them is: Will I be able to keep up?

We’re experts at all things backpacking

Trip types

We’re offering three types of trips:

Level 1: Fundamentals (3 days/2 nights)

Level 2: Adventures (5 days/4 nights and 7 days/6 nights)

Level 3: Expeditions (7 days/6 nights)

The trips are best suited for beginner, intermediate, and advanced backpackers, respectively, although some crossover is expected (e.g. I’ll consider strong, fit, and well read beginners for Adventure trips).

Hammock camping: the best way to sleep in the Appalachians

Physical intensities

Experience is not necessarily correlated with fitness, so I decouple these variables. Each trip type is offered in several intensity levels: Low, Moderate, High, and Very High.

By pairing like-abled backpackers together, the pace is “just right” for about everyone, including those at the front and the back.

Trip schedule

Several weeks ago I released a tentative trip schedule. Its summary:

Early-May: Fundamentals courses in West Virginia

July: Fundamentals and Adventure trips in the High Sierra

August (or June): Expeditions in Alaska

September: Fundamentals and Adventure trips in the Colorado Rockies

Overlooking the Yanert River valley.

Locations

Special permits are required to operate commercially on public lands, and the process takes months.

My permit in West Virginia is pending. If approved (which is likely), the location will be near Elkins.

I hope to run the High Sierra trips in Yosemite National Park, pending permit approval (which I believe is likely). As a backup, the trips will be in Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park.

In Alaska, I’m debating between the eastern Alaska Range and the Brooks Range. This is the least settled location.

The Colorado trips will definitely be in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Rock Island Lake, a rarely visited alpine basin

Prices

The trip prices are around the market average, and not inexpensive. But they’re justifiable: if you’re new to backpacking, we’ll save you hundreds or maybe thousands of dollars in regrettable purchases; and if you’re more experienced, we’ll teach you skills that would take years to learn on your own, and we’ll spare you from hours of tedious trip planning.

Women-only trips

For the first time, we will be offering women-only sessions.

Fundamentals: Sept 6-8

Adventure: Sept 9-13

These trips will be in the Colorado Rockies and be guided by Mary Cochenour, Jessica Winters, and Heather Anderson. You’re in good hands:

How to apply

The open application period will start on Monday, January 7 and end on Sunday, January 20. Applications received during this time will be divided into three groups: alumni, previously waitlisted, and newcomers. Priority will follow that order, but all applications within each group will be given equal consideration.

Starting January 21, I’ll move to a first-come-first-serve system, with new applicants eligible for any remaining spots. In 2019 I’m offering more trips and more spots than I ever have before, but I’m still expecting the most popular trips to fill completely or mostly with applications received during the open period.

Questions?

Leave a comment below, or contact me directly.

The post Program orientation: My 2019 guided trips appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

December 18, 2018

Spiderwoman’s KCHBR Tips || Section 3: South Fork Basins

Spiderwoman thru-hiked the Kings Canyon High Basin Route in 2017 with her partner, The Brawn. These are her “tips” about the route, a term that does not do justice to their comprehensiveness and detail. The information has been split into seven posts to improve readability:

Introduction

Section 1: Tablelands

Section 2: Great Western Divide

Section 3: South Fork Basins

Section 4

Section 5

Section 6

She has shared all of her photos from her trip, available here.

Charlotte Lake

Kelby, The Brawn, and I started our KCHBR thru-hike loop at Onion Valley TH and walked to Charlotte Lake from Kearsarge Pass. Kelby planned to hike with us to “PR-51” at LeConte Ranger Station and we would all hike over Bishop Pass together. Kelby would leave in his rental car to catch a plane back home and the Brawn and I would pick up our resupply at Parchers Resort.

Building up to late afternoon thunder and drizzle

We passed several picturesque campsites as we walked toward the west end of Charlotte Lake. All were unoccupied. The sites’ older-style bear lockers gave me the impression that bears figured out the human food/Charlotte Lake connection a long, long time ago.

Skurka mentions “Rick Sanger”. This guy’s name keeps popping up on my radar. I first heard of him in Eric Blehm’s The Last Season. I was reading it while simultaneously walking through the Sierra on my ’09 PCT thru-hike. Then guess who I met while walking through the Sierra on my ’09 PCT thru-hike? Yep.

Rick was fantastically charming. Told us some cute details about just having gotten married. He for some reason sat down to hang out and goof around with us – he let my friend Alex pose with his walkie-talkie – this was all instead of asking to see our permits or bear canisters. He was A-class lovely, warm and light and smiley, so I didn’t know if mentioning The Last Season would be weird or not, so I chose not to. The next time we crossed paths was on my ’11 SHR thru-hike. I saw that he had signed the Frozen Lake Pass register just before I was there. I can’t remember if it was that morning, or the day before? Anyway, of all the rangers, Sanger’s name is mentioned in the KCHBR guide. In such a big world, it feels grounding to cross paths, even if it’s just an ephemeral experience in my own head, with the same characters time and time again.

The trail was obvious past Charlotte Lake’s outlet…until all of a sudden it wasn’t. This was the spot where “the trail crosses to the south side of the lake outlet”. Even knowing that we should be looking for a stream crossing we still had to drop our packs and look around when our trail petered out in an open flat grassy area. I went to get water and followed the path of least resistance through some light brush to reach the small stream. And wouldn’t you know it, that path of least resistance ended up being the use trail.

Further along, thunder boomed as we got our first view of the striking granite tower that is Charlotte Dome. Kelby was telling us about his fun climb of it some years earlier, and was trying to remember how he’d approached it, because it wasn’t from the direction we were walking. Then we met a couple walking back to their camp at Charlotte Lake. Bird and Bill from SoCal. They had the best energy. They were grateful to be out there, had an air of professionalism yet were down to earth, and were wonderful conversationalists. I was like, here we go again, meeting the crème de la crème, and needing to say good-bye so quickly. That’s one of the most difficult parts of thru-hiking – the schedule trumping relationship building. But in this case, we got a very unexpected 2nd chance…

The trail is indeed “less obvious” for quite a stretch through the “open lodgepole forest”. It was nice having 3 people to spread out and look for clues. Knowledge that we had both a baseline to eventually catch us if it came to that (the creek that passes just to the east of Charlotte Dome) and that the mapped trail showed our goal was to contour at a steady elevation helped us through the forest when we weren’t finding trail or cairns.

After crossing “the creek that flows from the base of Mt Gardiner”, Kelby, seeing how diligently I was following the cairns, was helpful in pointing out that this was where we “leave the climbers trail and all the cairns”. You’ll soon see the avalanche debris to the right. Indeed, just follow its west edge and it’ll soon be over. Your reward is a nice uphill walk through stately old growth. I led, and did eventually “intersect the old trail”, but lost it here and there. The trail wasn’t necessary anyway. While standing back at the upper margins of the “debris field”, before entering the dense tree cover, I got a sense for the lay of the land and the general area the pass would be. It was neat finding the way up to the pass for us, navigating based impressions and feelings I was being fed by my brain’s memory of the earlier view. Good stuff.

Whoa. The “north side” of Gardiner Pass looked steep and had a plug of icy snow in its middle. Standing at the edge with the wonderful mid-morning sun on our backs, peering down into the shaded notch, I think we all took a couple gulps and thought let the route begin. After putting on microspikes and taking out ice axes (Kelby and I brought axes, The Brawn, having a markedly different perception of and relationship with risk, did not), Kelby stepped over the edge and led down the chute. Luckily there was just enough moat for us to squeeze down along the edge. Our microspikes + axes would have been worthless in this situation if it’d been solid ice all the way across the chute. Kelby remarked that we would have to have had front pointed down it with 12-point crampons. Having been in similar mountaineering situations, too, I completely agreed.

For safety, before I made each small move down the chute, I was relying heavily on getting as much purchase as possible into the ice with my axe’s pick. But the shape of the axe’s head was starting to really hurt my palm (I was using my CAMP Corsa. Was wishing for a BD Raven Pro). Next thing I knew, Kelby was taking off his gloves for me. And they weren’t minimal, typical thru-hiker gloves. These were big, fluffy, cushy – proper gloves. He wouldn’t let me decline, so we compromised. He ended up with one, and I ended up with the other. So sweet. Such a considerate teammate! That started a chain reaction – made me want to look for opportunities to help him if he could benefit from something extra.

On the descent to “Lake 2906”, the trail is indeed “obvious in many places”, and it also wasn’t an issue when we lost it. The creek and tarns provided an obvious handrail in this open terrain. We did get into a bit of “brush”, and more than a bit of mosquitoes. Boy were they excited to smell us. Poor Kelby was really irritated.

Once at “Lake 2906”, the advice to “follow the east shore to its north end, then hike east” to intersect the trail was spot-on. The terrain on that quick little walk east was that of walking on the edge of a steep, slabby granite drop-off. The Brawn and Kelby weren’t convinced, so they hung back at the lake while I scouted ahead and found the trail. The trail was indeed further west than it appears on the map, so it was an easy shout back to them to come on. The trail from there does indeed “steepen considerably” as it descends through stately old growth; you’ll definitely want to be on it.

Navigating from “PR-31” east to where the mapped trail recrosses Gardiner Creek was the most confusing cluster of the entire trip. We expended a lot of energy trying to stick to the mapped trail and it was such a mistake. I hope someone in the near future attempts staying “on the south side of the creek” as they proceed east from “PR-31”. I hope that it is “more practical”, and I hope they contact Skurka with feedback so he can include it in future updates. If I were doing this section again, I would stay on the south side of Gardiner Creek after reaching “PR-31”. I can’t imagine any scrambling through there that would be worse (time and energy and frustration-wise) than we experienced crossing to the north side.

So here’s what happened. We lost the trail after crossing to the north side of the narrow, rushing Gardiner Creek. (I can’t remember how we crossed – it must’ve been on large rocks?) It was an extremely brushy area. Literally impenetrable in places. There was this very distinct, dried out, large depression immediately to the west that looked like it was once a tarn, and should definitely be represented on a map, but was there any such landform depicted on the map? No… and was there a tarn where one is drawn on the map? No… (“satellite imagery”). Oh it was such a frustrating stretch through there.

Kelby and I scouted up the area on the map that is white, and on the ground is a steep talus + brushy slope. We climbed high. Up Up Up. We gave it a hearty effort. Thinking we were wrong, The Brawn stayed low and enjoyed taking some pictures of wildflowers. They were awfully pretty. The Brawn kept contouring east, and Kelby and I descended to meet him. We hopped across a fairly flat boulder field and entered the “flat forested area that holds standing water for much of the summer”. We walked over to the tranquil, flat-water that was Gardiner Creek up here, and, since we couldn’t find a better way, took our shoes off to cross the crotch-deep cold water. It was a fitting way to kinda cleanse ourselves of the last couple hours of pointless exertion.

The trail was not obvious to “PR-32”. We really tried to stick to it though because navigating through the woods here wasn’t straight forward. The 3 of us would spread out, move along super slowly, and one of us would eventually find a cairn, or a foot or two of evidence of a trail long abandoned. We’d reward each find with a genuine squeal and grin and Kelby would chime in with his new high routes are fun! (Dogged by pointless fatigue, dispirited by never ending woodlands views, I had said to Kelby earlier that day: high routes are fun. They’re not usually like this.)

We used the lake directly south of mapped “PR-32” as the point at which we stopped looking for trail and turned north to head for “PR-33 King Col”.

Once we popped out of the woods we had a great view of the towering ridgeline running from west to east. King Col was up there somewhere. We stood there for a long time trying to match up terrain features to our map. The Brawn’s interpretation had him advocating for ascending straight north toward terrain he thought was in the “King Col (central)” vicinity. Kelby and I weren’t seeing it that way though. Very, very unfortunately, 2 opinionated voices were louder than 1, and we all headed east-northeast up the valley that terminates on the southern flanks of Mount Clarence King.

The Brawn and Kelby wore themselves out by hopping across an extensive side hill of boulders. We knew from the map we were supposed to be high, so they stayed high, dammit. I thought to myself, screw this, I’m making up for that one morning on the WRHR by Bewmark Lake and I’m headed for a carefree walk on the fairyland down below.

I ended up traveling so much more efficiently, so much faster, that they became little specks in my rearview. It was touching watching The Brawn stop every dozen feet and look back, straining to locate me. I stopped once I had a definite grasp on our location – I was near the two sizable tarns. Cool! King Col must just be north up the slope. But on closer inspection, the chutes we’d have to ascend were incredibly steep and filled with unstable-looking rubble. And there were multiple chutes to choose from. Hmmm.

As I stood there studying the map, analyzing the terrain, studying the map, analyzing the terrain, it suddenly became cold. Like, really cold. Strangely cold. I dove into my pack and changed into all my warmest layers. Then it dawned on me. It’s the solar eclipse! Neat! It was already a whitish overcast sky, and the amount of overall light only decreased slightly, but the temperature plummeted. Kelby and The Brawn caught up and shivered into their spare layers. Kelby kept exclaiming I was outsmarted by a girl! I was outsmarted by a girl! That’s right.

Bundled up in our long johns, puffies, raingear, warm hats, and mittens, we stood there and talked through the navigation situation. We ID’d where we stood on the map. We were oriented. But where were we supposed to go from here? We kept studying the mapped ridge between “PR-33 King Col” and Mount Clarence King, and comparing it to the terrain in front/above us, and it just wasn’t coming together. We took foorrreeeevvvvveeeeeerrrrrrrrrrrrr. Brrrrrrrrrr. Confusinggggggg. Argggggggg.

We were nearly convinced, like high 90s%, that we were supposed to just head directly north from where we stood in order to find King Col. So a lot of our time standing there was trying to figure out which debris chute to ascend. They were all nasty looking. Like, for reals. Like, there was a high possibility of injury. None of us was gung-ho. Not one of us thought that ascending any one of those chutes was appropriate for a backpacking route. We must be off course.

Thankfully that very real, very immediate threat kept stalling us, because I kept going back to this one mapped feature that we DID NOT WALK, and that looked like a virtual red carpet entrance to King Col. On the map, the red carpet is between “King Col (central) and “PR-33 King Col”. It spans from 3400 to about 3580 meters. The contour lines are widely and evenly spaced in a west-southwest to east-northeast direction and give the impression that once up there it would be like walking up a broad, nicely angled slope that would terminate smack at King Col.

I advocated vigorously: WE DID NOT WALK THAT. WE DID NOT WALK THAT. Kelby and The Brawn definitely agreed. Relieved, we were like f’ya, let’s get the hell outta here and go find it. We turned. And walked back. And yes, they stayed down in the fairyland with the smart woman.

We laughed and apologized to The Brawn for the extracurricular jaunt up to the base of Mount Clarence King. He was rightfully smug with repeated I told you so’s…to this very day in fact as I sit here writing this (we just had a cute little exchange).

Some hours later, back standing approximately between “PR-32” and “King Col (central)”, we headed up The Brawn’s slope. This slope is open, composed of talus + brush that was easy to weave through, and is sandwiched between trees. We also chose this slope because it hugs the east end of the ridgeline that spans from “King Col (west)” to “King Col (central)”. YOU CANNOT SEE THE RED CARPET FROM DOWN BELOW. You can’t see it because the escarpment-like terrain on its southern edge hides it from view when you’re standing below it looking up.

That blocked view was exactly what messed us up. Studying the data in camp the night before I read “confirm your approach with a GPS”. I totally appreciate how much a GPS would have helped in this tricky navigational situation. Time is a critical commodity out there. I knew though that we’d make it through and later I’d regard it as a learning opportunity – albeit a forced, cold, confusing, time consuming, and stomach clenching one (thinking about those awful chutes we thought we had to climb).

We weren’t making our miles, so we’d most likely suffer from dwindling food supplies as the days went on. But just how late we’d be to our resupply was tbd. We were starting to think about early bail out options onto the JMT by this point.

The red carpet’s mellow, consistent grade and fool-proof navigable terrain was a well-deserved opportunity to daydream all the way up to King Col. I was excitedly anticipating the upcoming “crabwalk” challenge (and had been since seeing Wired and E’s bad-ass ’16 photo, you two rocked it), so it was invigorating to be able to settle on a maintainable pace and just stride it out, all the way up to…what the f#?!