Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 9

May 14, 2016

Mary Dyer changed the world. This is how.

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Mary Barrett Dyer didn't stop to ask if the people of New England who were being beaten and whipped (with scarring for life), imprisoned in Boston and New Haven prisons without heat during polar blizzards, fined into poverty, having their property confiscated and given to the religious magistrates to dispense, or were hanged, were "worthy" of her sacrifice.

Mary Dyer purposely left a place of safety on Shelter Island, literally crossed the ocean to get to Providence, and walked more than 40 miles through dangerous wilderness, to give up her life if the theocratic government would not rescind their "bloody law" against non-conformists. She didn't sneak into Boston: she boldly appeared there when there were hundreds or thousands more people in town for the annual elections and superior courts.

She wasn't an obscure, no-name bumpkin: she was a co-founder of Portsmouth and Newport. She was the wife of the first attorney general in America, an admiralty court judge, the commander-in-chief of the Anglo-Dutch war in New England waters, and solicitor general of Rhode Island. She was better educated than many men of her generation. She'd been reprieved from the gallows seven months before, in a scripted drama cooked up by the governor, his staff, and several ministers, because they knew killing her would antagonize the many people who respected and sided with Mary.

Mary defied that theocratic government to call attention to their brutality and injustice, and was prepared to die to stop their practices and spare people of conscience. People like Quakers and Baptists, and those who didn't share the same beliefs as the oppressors. And she went through with it, even when she was offered her life if she'd just leave Massachusetts.

That's what love does. That's what a mother would do for her children, and other peoples' children, young or old. And whether or not we carry Mary Barrett Dyer's DNA, we are all her children because of her civil disobedience unto death. That was love. Be like Mary. Love one another, whether they're worthy or not. It will change your life. And it will change the world.

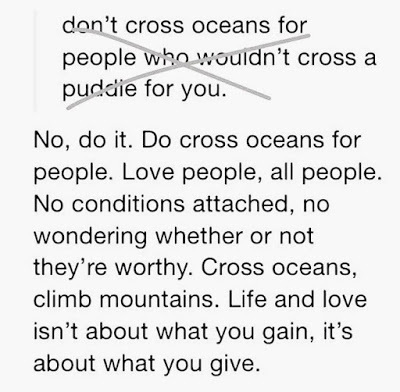

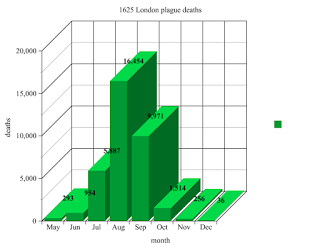

Christy K Robinson has written three books about Mary Dyer and her associates, and has been invited to take part in the "Our Founding Mothers" event at Harvard University in July 2016. If you enjoy this Dyer blog or the books, please consider helping with the travel expense at

GoFundMe

. <--Click that link. Thank you very much!

Christy K Robinson has written three books about Mary Dyer and her associates, and has been invited to take part in the "Our Founding Mothers" event at Harvard University in July 2016. If you enjoy this Dyer blog or the books, please consider helping with the travel expense at

GoFundMe

. <--Click that link. Thank you very much!

Mary Barrett Dyer didn't stop to ask if the people of New England who were being beaten and whipped (with scarring for life), imprisoned in Boston and New Haven prisons without heat during polar blizzards, fined into poverty, having their property confiscated and given to the religious magistrates to dispense, or were hanged, were "worthy" of her sacrifice.

Mary Dyer purposely left a place of safety on Shelter Island, literally crossed the ocean to get to Providence, and walked more than 40 miles through dangerous wilderness, to give up her life if the theocratic government would not rescind their "bloody law" against non-conformists. She didn't sneak into Boston: she boldly appeared there when there were hundreds or thousands more people in town for the annual elections and superior courts.

She wasn't an obscure, no-name bumpkin: she was a co-founder of Portsmouth and Newport. She was the wife of the first attorney general in America, an admiralty court judge, the commander-in-chief of the Anglo-Dutch war in New England waters, and solicitor general of Rhode Island. She was better educated than many men of her generation. She'd been reprieved from the gallows seven months before, in a scripted drama cooked up by the governor, his staff, and several ministers, because they knew killing her would antagonize the many people who respected and sided with Mary.

Mary defied that theocratic government to call attention to their brutality and injustice, and was prepared to die to stop their practices and spare people of conscience. People like Quakers and Baptists, and those who didn't share the same beliefs as the oppressors. And she went through with it, even when she was offered her life if she'd just leave Massachusetts.

That's what love does. That's what a mother would do for her children, and other peoples' children, young or old. And whether or not we carry Mary Barrett Dyer's DNA, we are all her children because of her civil disobedience unto death. That was love. Be like Mary. Love one another, whether they're worthy or not. It will change your life. And it will change the world.

Christy K Robinson has written three books about Mary Dyer and her associates, and has been invited to take part in the "Our Founding Mothers" event at Harvard University in July 2016. If you enjoy this Dyer blog or the books, please consider helping with the travel expense at

GoFundMe

. <--Click that link. Thank you very much!

Christy K Robinson has written three books about Mary Dyer and her associates, and has been invited to take part in the "Our Founding Mothers" event at Harvard University in July 2016. If you enjoy this Dyer blog or the books, please consider helping with the travel expense at

GoFundMe

. <--Click that link. Thank you very much!

Published on May 14, 2016 16:05

May 11, 2016

Send a 5-star author to Harvard University

Christy K Robinson, author of The Dyers books and this blog, has been invited to speak at Harvard University on the 17th-century civil rights pioneer and religious figure, Anne Marbury Hutchinson, and is requesting assistance to participate in this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pay for a round-trip flight, economy hotel, and related travel expenses including a 60-mile trip to Newport, Rhode Island, to investigate placing a memorial to William Dyer.

Christy K Robinson, author of The Dyers books and this blog, has been invited to speak at Harvard University on the 17th-century civil rights pioneer and religious figure, Anne Marbury Hutchinson, and is requesting assistance to participate in this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pay for a round-trip flight, economy hotel, and related travel expenses including a 60-mile trip to Newport, Rhode Island, to investigate placing a memorial to William Dyer.With years of research behind her, she’s written six books, four of them about the brilliant founders of New England: Mary and William Dyer, Anne Hutchinson and son Edward Hutchinson, Katherine Marbury Scott, Sir Henry Vane, John Winthrop, John Cotton, John Endecott, and many others. Christy’s books have received hundreds of compliments and five-star reviews from readers and other authors.

Rather than judge the history-makers by 21st-century standards, Christy places them in their own culture, climate, politics, religions, and timelines. Motivations behind their actions become clear in that light. Big holes in what we know about them are filled in with this kind of research.

Even after publication of the books, Christy’s research has continued, and is published free on several blogs. The Dyer blog receives 4,500-6,000 page views every month. Christy administers several Facebook pages about these 17th-century American founders, including a group for descendants of William and Mary Dyer, and she contributes new research to a descendants group for Anne Hutchinson. One of the organizers of the Harvard event commented on an article at the Wm & Mary Barrett Dyer blog , “You should know, Christy, this very blog posting was the inspiration for this July's OUR FOUNDING MOTHERS CELEBRATION, on the 425th birthday of Anne Marbury Hutchinson. Hope you can make it!”

But self-employment doesn’t budget for a 2,700-mile business trip to Harvard University. Your gift will help make possible this once-in-a-lifetime honor of being invited to contribute her research on Anne Hutchinson’s 425th birthday in July 2016.

Gifts of $200 or more will be rewarded with an autographed copy of Christy’s new book on Anne Hutchinson, to be published in August 2016, and an autographed set of Volumes 1 and 2 of the Dyers series.

Gifts of $100-199 will be rewarded with an autographed set of Volumes 1 and 2 of the Dyers series.

All other gifts will be gratefully received.

Will you help make this dream happen before June 25? To participate, go to this GoFundMe link and scroll to the bottom for the Donate button. And please do me the favor of Facebook sharing, tweeting, LinkedIn, and G+ shares.

Christy Robinson will take part in a presentation on Anne Hutchinson

Christy Robinson will take part in a presentation on Anne Hutchinson at Harvard University Divinity School on July 21, 2016.

Christy K Robinson has researched the Dyers for many years,

Christy K Robinson has researched the Dyers for many years,discovering previously-unknown facts about them,

and wrote three books (two fiction and one nonfiction)

about them in 2013 and 2014. You can find the books at

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

Published on May 11, 2016 19:32

April 14, 2016

May Day, the Maypole, and sincerely-held beliefs in the 1620s

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Thomas Morton was a bad, bad man. He was of a similar age with Anne Hutchinson, Gov. John Endecott, and Gov. John Winthrop, born in 1590. He was an English lawyer before he sailed to Massachusetts Bay in 1622, returned in 1625, and became a thorn in the side of the Plymouth Pilgrims and later the Puritans who founded Salem and Boston.

Thomas Morton was a bad, bad man. He was of a similar age with Anne Hutchinson, Gov. John Endecott, and Gov. John Winthrop, born in 1590. He was an English lawyer before he sailed to Massachusetts Bay in 1622, returned in 1625, and became a thorn in the side of the Plymouth Pilgrims and later the Puritans who founded Salem and Boston. He settled with some investor-adventurers in what is now Quincy, and proceeded to drink with the Indians and to give them guns to procure furs—which terrified the Pilgrims 26 miles to the south. Morton was no Separatist, Pilgrim, or Puritan, but an Anglican who would rather be hunting and fishing than sitting in a church, anyway. You can read more about Morton and his run-ins with Massachusetts government at his profile, http://www.nndb.com/people/056/000114711/ .

There probably were no women in Morton's Merrymount

There probably were no women in Morton's Merrymount community, unless they were servants or Indians.

Perhaps the event that Morton is remembered for the most is that he and his men set up an eighty-foot Maypole at a hill he named Merrymount (half a mile from Mt. Wollaston, where the Hutchinsons would own a farm from 1634 on), and there, his adventurers drank and danced with the Indians on the first day of May, 1625.

"The Inhabitants of . . . Mare Mount . . . did devise amongst themselves . . . Revels and merriment after the old English custome; (they) prepared to sett up a Maypole upon the festivall day . . . and therefore brewed a barrell of excellent beare . . . to be spent, with other good cheare, for all commers of that day. And . . . they had prepared a song fitting to the time and present occasion. And upon May day they brought the Maypole to the place appointed, with drumes, gunnes, pistols and other fitting instruments, for the purpose; and there erected it with the help of Salvages, that came thether to see the manner of our Revels. A goodly pine tree of 80 foot longe was reared up, with a peare of buckshorns nayled one somewhat neare unto the top of it: where it stood, as a faire sea mark for directions how to finde out the way to mine Hoste of Mare Mount."(Morton, The New England Cannan, Book III, Chapter 14.)

Things that are 80 feet in length:

Things that are 80 feet in length: brigantine, Airbus A380, truck.Now, an 80-foot pole is eight stories high, the length of an Airbus A380, and it would weigh about 10 tons, and that seems very large for a community of bachelors to fuss about. I watched a 1985 video of the raising of an 80-foot Maypole in Slingsby, UK, where they dug a large hole in which to seat the pole, then raised it with a crane before a band played “God Save the Queen.” To raise a 10-ton tree trunk with ropes and men to balance and stabilize it seems like a lot more work than drunken rebels would enjoy.

Unless they did it to purposelyannoy and outrage their sober Pilgrim neighbors, who, along with the Scottish Presbyterians and the English Puritans, considered the Maypole to be a pagan idol.

May Day was a spring fertility festival in many European cultures, going back to prehistory. It was a cross-quarter day, halfway between the spring equinox and the summer solstice, when the “veil” between the spirit world and our world was weak, and spirits could enter human beings and lead them astray. It was a time of sexual initiation, and girls who met boys in the tall grass or bushes came back with gowns of green, stained with chlorophyll.

During the centuries of Roman Catholic influence and authority, Christian churches were built on top of pagan worship sites to both conquer the previous culture’s gods and votive sites, and assimilate the old ways and worshipers into the new rites. Many astronomical, seasonal dates that had honored pagan gods were supplanted with saint festivals and holy days (holidays). Old customs took on new meanings, even if they were very thinly disguised.

At the English Reformation in the 16th century, Maypoles fell into disuse as the Puritan movement took the new Anglican Church further away from its Catholic (and therefore contaminated, pagan) roots. But the Puritans bent too far for many English people, and instituted a harsh, rigid, fundamentalist way of life that grated on Anglicans. In 1618, King James I, who had been plagued by rebellious and intransigent Puritan ministers, published a booklet called The Book of Sports (see article in this blog), that gave permission to, even directed, his subjects to break the Sabbath gloom with playing games and getting some healthy exercise. Among the activities the king suggested was to hold May games and set up Maypoles.

Our pleasure likewise is, That the Bishop of that Diocesse take the like straight order with all the Puritanes and Precisans within the same, either constraining them to conforme themselves, or to leave the County according to the Lawes of Our Kingdome, and Canons of Our Church, and so to strike equally on both hands, against the contemners of Our Authority, and adversaries of Our Church. And as for Our good peoples lawfull Recreation, Our pleasure likewise is, That after the end of Divine Service, Our good people be not disturbed, letted or discouraged from any lawful recreation, Such as dauncing, either men or women, Archery for men, leaping, vaultings or any other such harmelesse Recreation, nor from having of May Games,Whitsun [Pentecost] Ales; and Morris dances, and the setting up of Maypoles & other sports therewith used, So as the same be had in due & convenient time, without impediment or neglect of Divine Service: And that women shall have leave to carry rushes to the Church for the decoring of it, according to their old custome…

Morton’s first Maypole-raising was in 1625. As a lawyer and a subject of England, he knew he was within his rights, and fulfilling King James’ order, to set up a Maypole in his town. It seems that when Morton wasn’t being removed against his will to England and bouncing back to Massachusetts, he was drinking with the Indians, dealing guns to the Indians, and setting up a phallic symbol to madden the Pilgrim neighbors. But while Morton and his men were drunkenly contemplating their handiwork in 1628, Plymouth sent their military man, Myles Standish, to arrest Morton. Twenty-six miles on foot, or several hours of sailing, seems quite a distance for the Pilgrims to reach out to punish Morton, on his own land, for his revels. (The Pilgrims, who had escaped English persecution by fleeing to the Netherlands before risking their lives in savage wilderness of America, went out of their way to put an end to Morton’s religious beliefs.) They deposited Morton on an island with some provisions, until a ship could take him back to England, but he escaped with the help of his Indian associates.

John Endecott, in his first term as governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, visited Merrymount in 1629, and had the Maypole taken down. Chopping it with an ax would be more dramatic, but he may have pulled it down with ropes. (An 80-foot tree trunk might be useful as a ship mast.) Of course, you remember Endecott as the governor who sent four Quakers, including Mary Dyer, to the gallows from 1659-1661, tortured and imprisoned hundreds of others, hanged a woman who believed she saw the ghost of her dead child, and beat people to a pulp (including Baptist minister Obadiah Holmes Sr.) if they didn’t conform to his narrow fundamentalism.

John Endecott, in his first term as governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, visited Merrymount in 1629, and had the Maypole taken down. Chopping it with an ax would be more dramatic, but he may have pulled it down with ropes. (An 80-foot tree trunk might be useful as a ship mast.) Of course, you remember Endecott as the governor who sent four Quakers, including Mary Dyer, to the gallows from 1659-1661, tortured and imprisoned hundreds of others, hanged a woman who believed she saw the ghost of her dead child, and beat people to a pulp (including Baptist minister Obadiah Holmes Sr.) if they didn’t conform to his narrow fundamentalism. It wasn’t solely Endecott doing those actions. He was elected to office for numerous one-year terms as governor and assistant governor between 1629 and his death in 1665. Obviously, there was an element of colonial society who shared his ideology of religious government and enforcing certain beliefs.

In our society, we see similar events and responses in the news on a daily basis. Like the Maypole story, most of the news involves religious groups proclaiming their beliefs on morality issues such as same-sex relationships, sex outside marriage, contraconception and pregnancy termination, the death penalty, domestic violence, child molestation, anti [-Islamic/-Catholic/-Semitic/-pagan/-atheist, etc.]. There are also constant reports about prayer in public meetings, schools, and the military; and the existence of monuments or displays of the Ten Commandments at government buildings.

Knowing your history, and the forces and personalities behind it, is vitally important in slowing and stopping religious intolerance and oppression. Mary Dyer and her husband William, and the entire colony of Rhode Island, worked for years to develop a society of tolerance and human rights for all faiths, even those without faith, because without that provision, there is no true freedom. Mary intentionally defied Gov. Endecott and his system, and died to prove that religious liberty was a life and death matter. William Dyer, John Clarke, and Roger Williams codified that liberty in their constitution (the Charter of 1663), and their successful experiment with religious liberty and separation of church and state (a pet issue of Anne Hutchinson) was a huge influence on the United States Constitution written in the next century. __________________________ More reading on Morton or the Maypolehttp://lolmanuscripts.blogspot.com/2010/05/shepherds-ingenuity-or-praise-of-green.html_____________________________ http://newenglandfolklore.blogspot.com/2010/05/thomas-morton-and-maypole-of-merrymout.htmlGood material on Merrymount., which is in Quincy, half a mile from Mt. Wollaston (where the Hutchinsons owned land). ______________________________ http://www.nndb.com/people/056/000114711/ profile for Thomas Morton

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books, three of them on Mary and William Dyer.

We Shall Be Changed

(2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014)

Effigy Hunter

(2015)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books, three of them on Mary and William Dyer.

We Shall Be Changed

(2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014)

Effigy Hunter

(2015)

Published on April 14, 2016 23:47

March 26, 2016

Political correction

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Writers, reporters, critics, political satirists, internet trolls, and message-bearers, be glad of your constitutional rights to free speech and the privileges of citizenship.

Once upon a time in 1663-1664, in New Netherland (Long Island, pre-New York), the inhabitants of Bushwick complained of having money extorted by the Dutch West Indies Company (WIC), for the rights of citizenship. They could see that the colony was slipping away from the Netherlands, to become an English possession.

Once upon a time in 1663-1664, in New Netherland (Long Island, pre-New York), the inhabitants of Bushwick complained of having money extorted by the Dutch West Indies Company (WIC), for the rights of citizenship. They could see that the colony was slipping away from the Netherlands, to become an English possession.

This unrest, after three Anglo-Dutch naval wars in the English Channel, the Caribbean, and the East Indies, preceded the Dutch surrender of New Netherland to the English.

(Remember that William Dyer, Mary's husband, had been Commander-in-Chief-Upon-the-Seas in the 1652-54 First Anglo-Dutch War, part of which was carried out on a privateer basis in Long Island Sound.)

In May 1664,

Jan Willemsen Van Iselsteyn, commonly called Jan of Leyden, for using abusive language and writing an insolent letter to the magistrates of Bushwick, was sentenced to be fastened to a stake near the gallows, with a bridle in his mouth, a bundle of rods under his arm, and a paper on his breast bearing the words,

Lampoon-riterFalse-accuserDefamer of Magistrates After this ignominy he was to be banished, with costs.

On the same day, William Jansen Traphagen, of Lemgo, for being the bearer of the above insolent letter to the magistrates of Bushwick [who were employed by the WIC], as well as for using very indecent language towards them, was also sentenced to be tied to the stake, in the place of public execution, with a paper on his breast, inscribed 'Lampoon carrier.' His punishment, also, was completed with banishment and costs. Source: A History of the City of Brooklyn: Including the Old Town and ..., Volume 2, By Henry Reed Stiles

https://books.google.com/books?pg=PA338&lpg=PA338&dq=Jan+of+Leyden,+Bushwyk&sig=2ULENXeWqFpTbTeLk2HaiW-CNqw&id=p3MxAAAAMAAJ&ots=keZTaTn1T5&output=text

A "lampoon" is defined as "a sharp, often virulent satire directed against an individual or institution; a work of literature, art, or the like, ridiculing severely the character or behavior of a person, society, etc." The word was relatively new, about 20-30 years old, in 1664.

The bridle sometimes had spikes on the tongue (see image with bridle attachments), and was meant to reduce its wearer to the mute state of a farm animal. New Haven Colony tied a "key" into the mouth of Humphrey Norton, a Quaker missionary, to silence him, and if you look at the implements in the foreground of the image, you see the bridle bits look like keys.

To sum it up, the WIC government of Dutch Long Island were demanding money of the citizens, perhaps by taxing them or withholding rights over money, and several people protested in writing, since they were undoubtedly aware that the Dutch rule was doomed because the English were coming in. The WIC magistrates deemed this protest sedition and squelched it by bodily punishment, banishment, and court costs. Then the English took over in September 1664.

In the 1670s, William Dyer Jr. (son of William and Mary) was the King's customs inspector for New York, and the Mayor of New York.

Jan of Leyden wasn't the only man to be "insolent," use bad language, or react violently in the Dutch colony when his rights were threatened. I had a Dutch ancestor in that town, Dirck Volkertze, who was known, more than once, to settle arguments with a knife! On the other hand, their minister, Johann Theodorus Polhemus, also my ancestor, was well-respected and faithful to his God and his flock for decades, during both Dutch and English rule.

Related story about bridles in this site: Dorothy Waugh, young Quaker woman, described her experience with the bridle in Carlisle, England.

****************

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books (all with five-star reviews), three of them concerning William and Mary Barrett Dyer and their associates in 17th-century England and New England. Click a highlighted link to read the reviews and purchase the books or ebooks.

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Writers, reporters, critics, political satirists, internet trolls, and message-bearers, be glad of your constitutional rights to free speech and the privileges of citizenship.

Once upon a time in 1663-1664, in New Netherland (Long Island, pre-New York), the inhabitants of Bushwick complained of having money extorted by the Dutch West Indies Company (WIC), for the rights of citizenship. They could see that the colony was slipping away from the Netherlands, to become an English possession.

Once upon a time in 1663-1664, in New Netherland (Long Island, pre-New York), the inhabitants of Bushwick complained of having money extorted by the Dutch West Indies Company (WIC), for the rights of citizenship. They could see that the colony was slipping away from the Netherlands, to become an English possession.This unrest, after three Anglo-Dutch naval wars in the English Channel, the Caribbean, and the East Indies, preceded the Dutch surrender of New Netherland to the English.

(Remember that William Dyer, Mary's husband, had been Commander-in-Chief-Upon-the-Seas in the 1652-54 First Anglo-Dutch War, part of which was carried out on a privateer basis in Long Island Sound.)

In May 1664,

Jan Willemsen Van Iselsteyn, commonly called Jan of Leyden, for using abusive language and writing an insolent letter to the magistrates of Bushwick, was sentenced to be fastened to a stake near the gallows, with a bridle in his mouth, a bundle of rods under his arm, and a paper on his breast bearing the words,

Lampoon-riterFalse-accuserDefamer of Magistrates After this ignominy he was to be banished, with costs.

On the same day, William Jansen Traphagen, of Lemgo, for being the bearer of the above insolent letter to the magistrates of Bushwick [who were employed by the WIC], as well as for using very indecent language towards them, was also sentenced to be tied to the stake, in the place of public execution, with a paper on his breast, inscribed 'Lampoon carrier.' His punishment, also, was completed with banishment and costs. Source: A History of the City of Brooklyn: Including the Old Town and ..., Volume 2, By Henry Reed Stiles

https://books.google.com/books?pg=PA338&lpg=PA338&dq=Jan+of+Leyden,+Bushwyk&sig=2ULENXeWqFpTbTeLk2HaiW-CNqw&id=p3MxAAAAMAAJ&ots=keZTaTn1T5&output=text

A "lampoon" is defined as "a sharp, often virulent satire directed against an individual or institution; a work of literature, art, or the like, ridiculing severely the character or behavior of a person, society, etc." The word was relatively new, about 20-30 years old, in 1664.

The bridle sometimes had spikes on the tongue (see image with bridle attachments), and was meant to reduce its wearer to the mute state of a farm animal. New Haven Colony tied a "key" into the mouth of Humphrey Norton, a Quaker missionary, to silence him, and if you look at the implements in the foreground of the image, you see the bridle bits look like keys.

To sum it up, the WIC government of Dutch Long Island were demanding money of the citizens, perhaps by taxing them or withholding rights over money, and several people protested in writing, since they were undoubtedly aware that the Dutch rule was doomed because the English were coming in. The WIC magistrates deemed this protest sedition and squelched it by bodily punishment, banishment, and court costs. Then the English took over in September 1664.

In the 1670s, William Dyer Jr. (son of William and Mary) was the King's customs inspector for New York, and the Mayor of New York.

Jan of Leyden wasn't the only man to be "insolent," use bad language, or react violently in the Dutch colony when his rights were threatened. I had a Dutch ancestor in that town, Dirck Volkertze, who was known, more than once, to settle arguments with a knife! On the other hand, their minister, Johann Theodorus Polhemus, also my ancestor, was well-respected and faithful to his God and his flock for decades, during both Dutch and English rule.

Related story about bridles in this site: Dorothy Waugh, young Quaker woman, described her experience with the bridle in Carlisle, England.

****************

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books (all with five-star reviews), three of them concerning William and Mary Barrett Dyer and their associates in 17th-century England and New England. Click a highlighted link to read the reviews and purchase the books or ebooks.

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on March 26, 2016 00:00

February 24, 2016

Where did the DYER name come from?

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Surnames (also called family names) were adopted in the 1200s and 1300s and people took their names from places, trades or professions, the head of the family or clan, and personal characteristics.

Some occupational names we recognize today are Tyler (made ceramic or clay tiles), Cartwright (built wagons), Carter (transported goods by wagon), Carpenter (built houses, churches, ships, and furniture), Mason (stone builder), Taylor (sewed clothing), Hooper (made barrel stays), Smith (blacksmith or metal worker), and many others.

The Dyer name is not a rare one, and can't be traced back to one progenitor with many descendants. The name was one applied to a tradesman who dyed wool and cloth, which was a huge industry in Britain for hundreds of years.

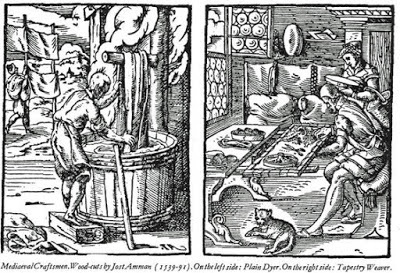

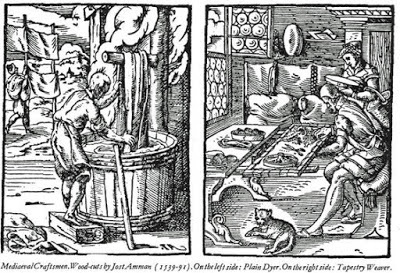

15th century wool dyer and tapestry weaver.

15th century wool dyer and tapestry weaver.

(Yay for cats!)

See below for more images of dyers.

Robert le Deyare is registered in the 1275 Subsidy Rolls of Worcestershire; Alexander Dyghere is listed in the 1296 Subsidy Rolls of Sussex; and Henry le Dyer is noted in the 1327 Subsidy Rolls of Derbyshire. Bryan Dyer and Wenefrid Ketton were married on June 3rd 1583, at Enfield, London, and the marriage of Thomas Dyer and Margaret Gibson took place at St. Mary at Hill, London, on August 27th 1593. In March 1634, John Dyer, aged 28 yrs., departed from the Port of London, aboard the "Christian" bound for New England. He was one of the earliest of the namebearers in the New World. Notice from that quotation above, that "our" William Dyer wasn't the only Dyer to emigrate to New England. Nor was he the only William Dyer, for there were a William and Mary Dyer in Sheepscot, Maine, who were not the same as our William and Mary Barrett Dyer of Boston, Portsmouth, and Newport.

William Dyer (who actually spelled his name "Dyre,") was born on his parents' farm in Kirkby LaThorpe, Lincolnshire, in September 1609. But his father, also a William Dyer, didn't have roots there. Many genealogists and researchers believe (but haven't proved) the father came from Somerset, a county in the southwest of England, near Bristol.

Concentration of Dyer name in the United Kingdom. Notice the high incidence of the Dyer surname in Somerset County, in southwest Britain. The Somerset Dyers, who are more likely to be related to us than the other "hot" areas around England, may be our cousins 12 times removed.

Another surname site,

Florentine dyers in 1458 Italy.

Florentine dyers in 1458 Italy.

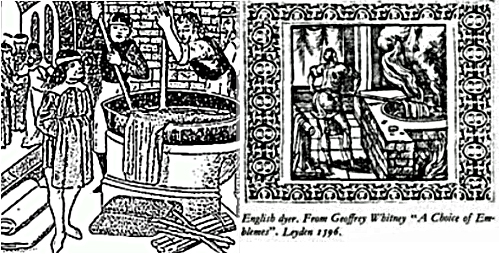

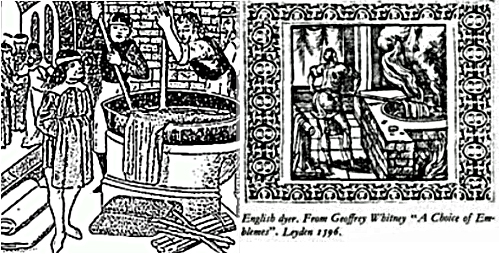

Left image: medieval English textile dyer.

Left image: medieval English textile dyer.

Right image: English dyers, published in a 1596 book in Leyden, Netherlands (the destination of the English Pilgrims between 1610 and 1620, when many of them emigrated to Plymouth, Mass., on the Mayflower.

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books: We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books: We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Surnames (also called family names) were adopted in the 1200s and 1300s and people took their names from places, trades or professions, the head of the family or clan, and personal characteristics.

Some occupational names we recognize today are Tyler (made ceramic or clay tiles), Cartwright (built wagons), Carter (transported goods by wagon), Carpenter (built houses, churches, ships, and furniture), Mason (stone builder), Taylor (sewed clothing), Hooper (made barrel stays), Smith (blacksmith or metal worker), and many others.

The Dyer name is not a rare one, and can't be traced back to one progenitor with many descendants. The name was one applied to a tradesman who dyed wool and cloth, which was a huge industry in Britain for hundreds of years.

15th century wool dyer and tapestry weaver.

15th century wool dyer and tapestry weaver. (Yay for cats!)

See below for more images of dyers.

Robert le Deyare is registered in the 1275 Subsidy Rolls of Worcestershire; Alexander Dyghere is listed in the 1296 Subsidy Rolls of Sussex; and Henry le Dyer is noted in the 1327 Subsidy Rolls of Derbyshire. Bryan Dyer and Wenefrid Ketton were married on June 3rd 1583, at Enfield, London, and the marriage of Thomas Dyer and Margaret Gibson took place at St. Mary at Hill, London, on August 27th 1593. In March 1634, John Dyer, aged 28 yrs., departed from the Port of London, aboard the "Christian" bound for New England. He was one of the earliest of the namebearers in the New World. Notice from that quotation above, that "our" William Dyer wasn't the only Dyer to emigrate to New England. Nor was he the only William Dyer, for there were a William and Mary Dyer in Sheepscot, Maine, who were not the same as our William and Mary Barrett Dyer of Boston, Portsmouth, and Newport.

William Dyer (who actually spelled his name "Dyre,") was born on his parents' farm in Kirkby LaThorpe, Lincolnshire, in September 1609. But his father, also a William Dyer, didn't have roots there. Many genealogists and researchers believe (but haven't proved) the father came from Somerset, a county in the southwest of England, near Bristol.

Concentration of Dyer name in the United Kingdom. Notice the high incidence of the Dyer surname in Somerset County, in southwest Britain. The Somerset Dyers, who are more likely to be related to us than the other "hot" areas around England, may be our cousins 12 times removed.

Another surname site,

Florentine dyers in 1458 Italy.

Florentine dyers in 1458 Italy. Left image: medieval English textile dyer.

Left image: medieval English textile dyer. Right image: English dyers, published in a 1596 book in Leyden, Netherlands (the destination of the English Pilgrims between 1610 and 1620, when many of them emigrated to Plymouth, Mass., on the Mayflower.

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books: We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books: We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on February 24, 2016 18:35

February 18, 2016

You can look at these antique maps for hours

© 2016 Christy K. Robinson

Have you ever wondered about the image used in this blog's header? It's a portion of a large panel engraved in 1616 by Claes Jansz Visscher, a Dutch artist of the 17th century (when the Dyers lived). The amazing thing is that Visscher never visited England--so where did he get the descriptions of the River Thames and the hundreds of buildings in the engraving? How did he know where to plot St. Paul's, the Tower, the Globe Theater?

Mercurius Politicus, a blog about 17th century history, says that Visscher's panorama is derived from a 1593 map engraving by John Norden, a surveyor and engraver. https://mercuriuspoliticus.wordpress.com/2008/07/22/london-panorama/

1593-John Norden's map of London. Click to enlarge.

1593-John Norden's map of London. Click to enlarge.

(Wikipedia Commons) Visscher used Norden's map as a resource, but tilted the view nearer the horizon and just higher than a cathedral spire. We can do that with Google Maps street view or Google Earth. But for a 17th century Dutchman who hadn't even visited London, his panorama is astounding!

We can go even further back to an angel's-eye view of Tudor London, with the 1560 Ralph Agas map called Civitas Londinium. (Where did these people get the idea for such a high-altitude perspective?!)

1560-Civitas Londinium, by Ralph Agas. Click to enlarge.

1560-Civitas Londinium, by Ralph Agas. Click to enlarge.

(Wikipedia Commons)

A similar panorama of London was engraved in 1647 by Vaclav "Wenceslaus" Hollar, an etcher from Prague, Bohemia.

1647-Long View of London, by Wenceslaus Hollar. (Wikipedia Commons)

1647-Long View of London, by Wenceslaus Hollar. (Wikipedia Commons)

As part of the 1616-2016 commemoration of Shakespeare's death, London's Guildhall Gallery is exhibiting the modern version of Visscher's panorama. From the same birds-eye perspective Visscher used, modern artist Robin Reynolds has created a 2016 panorama of London. Since most of us are not able to attend the exhibit, the websites will have to do. To see the Visscher and Reynolds works compared side by side and with zoomed-in sections, check out this news item at the link.

http://www.citylab.com/design/2016/02/london-panorama-1616-2016-visscher-exhibit/470085/

London panorama in 2016, by Robin Reynolds.Before I wrote the books on the Dyers, I studied all the maps of the 16th and 17th centuries to determine where the Dyers lived, in relation to their church (St. Martin-in-the-Fields), William's master Walter Blackborne's house (where William was apprenticed, and where he and Mary lived when newlyweds), the New Exchange (where Blackborne and William Dyer were proprietors of a haberdashery), where Sir Henry Vane's parents lived, and many other locations. To see some close-ups and photos of the places, see my article in this blog, The Dyers of London and where they lived.

London panorama in 2016, by Robin Reynolds.Before I wrote the books on the Dyers, I studied all the maps of the 16th and 17th centuries to determine where the Dyers lived, in relation to their church (St. Martin-in-the-Fields), William's master Walter Blackborne's house (where William was apprenticed, and where he and Mary lived when newlyweds), the New Exchange (where Blackborne and William Dyer were proprietors of a haberdashery), where Sir Henry Vane's parents lived, and many other locations. To see some close-ups and photos of the places, see my article in this blog, The Dyers of London and where they lived.

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Have you ever wondered about the image used in this blog's header? It's a portion of a large panel engraved in 1616 by Claes Jansz Visscher, a Dutch artist of the 17th century (when the Dyers lived). The amazing thing is that Visscher never visited England--so where did he get the descriptions of the River Thames and the hundreds of buildings in the engraving? How did he know where to plot St. Paul's, the Tower, the Globe Theater?

Mercurius Politicus, a blog about 17th century history, says that Visscher's panorama is derived from a 1593 map engraving by John Norden, a surveyor and engraver. https://mercuriuspoliticus.wordpress.com/2008/07/22/london-panorama/

1593-John Norden's map of London. Click to enlarge.

1593-John Norden's map of London. Click to enlarge. (Wikipedia Commons) Visscher used Norden's map as a resource, but tilted the view nearer the horizon and just higher than a cathedral spire. We can do that with Google Maps street view or Google Earth. But for a 17th century Dutchman who hadn't even visited London, his panorama is astounding!

We can go even further back to an angel's-eye view of Tudor London, with the 1560 Ralph Agas map called Civitas Londinium. (Where did these people get the idea for such a high-altitude perspective?!)

1560-Civitas Londinium, by Ralph Agas. Click to enlarge.

1560-Civitas Londinium, by Ralph Agas. Click to enlarge. (Wikipedia Commons)

A similar panorama of London was engraved in 1647 by Vaclav "Wenceslaus" Hollar, an etcher from Prague, Bohemia.

1647-Long View of London, by Wenceslaus Hollar. (Wikipedia Commons)

1647-Long View of London, by Wenceslaus Hollar. (Wikipedia Commons)As part of the 1616-2016 commemoration of Shakespeare's death, London's Guildhall Gallery is exhibiting the modern version of Visscher's panorama. From the same birds-eye perspective Visscher used, modern artist Robin Reynolds has created a 2016 panorama of London. Since most of us are not able to attend the exhibit, the websites will have to do. To see the Visscher and Reynolds works compared side by side and with zoomed-in sections, check out this news item at the link.

http://www.citylab.com/design/2016/02/london-panorama-1616-2016-visscher-exhibit/470085/

London panorama in 2016, by Robin Reynolds.Before I wrote the books on the Dyers, I studied all the maps of the 16th and 17th centuries to determine where the Dyers lived, in relation to their church (St. Martin-in-the-Fields), William's master Walter Blackborne's house (where William was apprenticed, and where he and Mary lived when newlyweds), the New Exchange (where Blackborne and William Dyer were proprietors of a haberdashery), where Sir Henry Vane's parents lived, and many other locations. To see some close-ups and photos of the places, see my article in this blog, The Dyers of London and where they lived.

London panorama in 2016, by Robin Reynolds.Before I wrote the books on the Dyers, I studied all the maps of the 16th and 17th centuries to determine where the Dyers lived, in relation to their church (St. Martin-in-the-Fields), William's master Walter Blackborne's house (where William was apprenticed, and where he and Mary lived when newlyweds), the New Exchange (where Blackborne and William Dyer were proprietors of a haberdashery), where Sir Henry Vane's parents lived, and many other locations. To see some close-ups and photos of the places, see my article in this blog, The Dyers of London and where they lived.  Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on February 18, 2016 11:41

January 26, 2016

1657 Boston courthouse where Mary Dyer was tried

Some of the images are of the Boston Town House where trials were held from 1657 on, and the undeveloped space as it would have appeared before 1630, when Boston was founded.

William Dyer, the first attorney general in America, was there several times on court business, as we know from his letter to the General Court on his wife's behalf. And Mary Dyer knew the courthouse from her arraignments and capital trials in 1657, 1659, and 1660. (The Old State House is not the same building or location as the State House where the Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson statues are located. See map below.)

I found the animation on the Facebook page of City of Boston Archaeology Program, who told me that the animated GIF is not copyrighted. This was their caption:

http://giphy.com/gifs/history-landsca...

via GIPHY

Learn more about the 1657 Boston Townhouse (Old State House) in the book

Learn more about the 1657 Boston Townhouse (Old State House) in the book

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This , by Christy K Robinson.

Available at Amazon in paperback and Kindle.

William Dyer, the first attorney general in America, was there several times on court business, as we know from his letter to the General Court on his wife's behalf. And Mary Dyer knew the courthouse from her arraignments and capital trials in 1657, 1659, and 1660. (The Old State House is not the same building or location as the State House where the Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson statues are located. See map below.)

I found the animation on the Facebook page of City of Boston Archaeology Program, who told me that the animated GIF is not copyrighted. This was their caption:

"In this one we feature the Old State House, first built in 1713, walking back its 1775 appearance during the Boston Massacre (with a cameo from the First "Old Brick" Church built in 1713), and the Town House first built in 1657 before ending with its approximate appearance before European arrival. Today, the building is operated by the The Bostonian Society."GIF created by and courtesy of the City of Boston Archaeology Program, used by permission.

http://giphy.com/gifs/history-landsca...

via GIPHY

Learn more about the 1657 Boston Townhouse (Old State House) in the book

Learn more about the 1657 Boston Townhouse (Old State House) in the bookMary Dyer: For Such a Time as This , by Christy K Robinson.

Available at Amazon in paperback and Kindle.

Published on January 26, 2016 23:25

January 23, 2016

William Dyer’s annus horribilis

Where was William Dyer during the plague of 1625?

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

The woman has a plague bubo which is being lanced. Probably

The woman has a plague bubo which is being lanced. Probably a European illustration, not English.Extraordinary floods, failed crops, pandemics of bubonic plague, typhus, and dysentery, the death of the old king and late coronation of the new king. Leaving home in the country and being apprenticed (on trial, anyway) at age 14 in the big city. William Dyer’s first year away from home was an annus horribilis.

Midsummer Day in 16th- and 17th-century England was a solstice celebration with pagan roots and a Christian blending, on the Feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist. Antiquarian John Stowe wrote:

“…every man’s door being shadowed with green birch, long fennel, St John’s Wort, Orpin, white lilies and such like, garnished upon with garlands of beautiful flowers.”

There were bonfires lit, and wealthy people supplied cakes and ale. Trade and craft guilds all over England participated in candlelit military processions, and London and its many liveries were no exception.

Procession past Charing Cross in Westminster

Procession past Charing Cross in Westminster Univ of Victoria Library

http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/society/city%20life/citylondon3.html

On Midsummer Day, June 24, 1624, when William Dyer was not quite 15 years old, he was apprenticed to Westminster (London) haberdasher and milliner, Walter Blackborne. William had been born 120 miles north of there, between Sleaford and Boston in Lincolnshire, and was educated in maths, writing, history, Latin, literature, religion, and the arts, probably at the Carre Grammar School. June 24 was a popular day for apprentices to be contracted, so there were probably initiation ceremonies at the guildhalls, after which the masters and apprentices prepared for their evening parade. William, enjoying the festival, had no way of knowing what his life would be like in the next year and a half.

In February 1625, there was a super-tidal event, when the surge up the Thames flooded London. Westminster Hall had three feet of standing water. Across eastern England, in the lowland fens (marshes) that stretched up to Boston and William's home village of Kirkby LaThorpe, the sea and the freshwater rivers and fens surged over their banks and dikes.

The old King James died on March 27, 1625, when his son and heir, Charles, was set to marry the princess Henrietta Maria of France. The princess was a Catholic, and neither the Church of England nor the Puritan dissenters held any liking for Catholics. Near the end of April, “the London apprentices – a class always foremost in city frays – catching the spirit of their sires and elders, gave it violent expression, by assaulting the Spanish ambassador’s house in Bishopsgate Street, threatening to pull it about his Excellency's ears, and to take his life in revenge for permitting English Papists to frequent his chapel.” www.archive.org/stream/.../ecclesiasticalhi01stou_djvu.txtEcclesiastical History of England, by John Stoughton, 1807

We don’t know if William was among that apprentice mob, but as a 15-year-old boy, was probably kept under the strict and watchful eyes of his master, who lived in Westminster, two miles away.

“Apprentices were reliant on their masters for their food, drink, clothing and houses; they were not to gamble, marry, or stay out to ‘haunt play-houses, taverns or ale houses’ without permission; they were rarely paid; instead they often paid their master to take them on in the first place; and this was to last for seven years – at least. In return, their master would feed, house, clothe and instruct them.”

http://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/apprenticeship-in-early-modern-london-the-economic-origins-and-destinations-of Apprenticeships in Early Modern London: Economic Origins and Destinations of Apprentices in the 16th and 17th Centuries, by Dr Patrick Wallis and Dr Christopher Minns, Gresham College, London, 2012

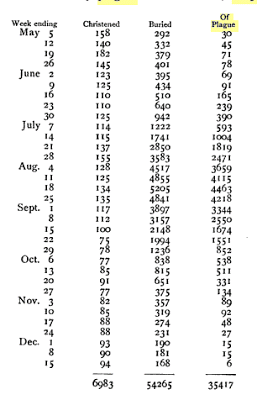

In May 1625, immediately after King James’ funeral, bubonic plague, which was a perennial threat but isolated, broke out in the poorest, most crowded streets of London, where the tenements met the edge of the Thames, and had been flooded four months before. The weekly mortality bills show that the confirmed plague deaths squared and cubed upon themselves.

These nine panels illustrate the Great Plague of 1665, but they easily fit the 1625 plague, as well.On June 12, 1625, Chamberlain writes: "We have had for a month together the extremest cold weather ever I knew in this season." The whole month of June was a time of "ceaseless rain in London."In the country, the hay-harvest was spoilt, and the corn-harvest [all grains, but not American Indian corn] was only a half crop. https://books.google.com/books?id=tXwaAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA512&lpg=PA507&focus=viewport&dq=plague+of+1625&output=text A History of Epidemics in Britain, Vol. 1, by Charles Creighton, 1894

These nine panels illustrate the Great Plague of 1665, but they easily fit the 1625 plague, as well.On June 12, 1625, Chamberlain writes: "We have had for a month together the extremest cold weather ever I knew in this season." The whole month of June was a time of "ceaseless rain in London."In the country, the hay-harvest was spoilt, and the corn-harvest [all grains, but not American Indian corn] was only a half crop. https://books.google.com/books?id=tXwaAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA512&lpg=PA507&focus=viewport&dq=plague+of+1625&output=text A History of Epidemics in Britain, Vol. 1, by Charles Creighton, 1894“The deaths from all causes in May and June were so many more than the reported plague-deaths could account for that those who watched the bills of mortality (Mead at Cambridge, Salvetti in London) suspected that plague was being concealed. "It is a strange reckoning," says Mead of the bill for the week ending June 30: "Are there some other diseases as bad and spreading as the plague, or is there untrue dealing in the account?" Probably there were both; at the end of the year the deaths from all causes were some 20,000 more than the plague accounted for; and at least half of that excess was extra to the ordinary mortality. The spotted fever [typhus] and the flux [bloody dysentery] doubtless continued side by side with the plague, having been its forerunners… The plague of 1625 was a great national event, although historians, as usual, do no more than mention it. Coinciding exactly with the accession of Charles I, it stopped all trade in the City for a season and left great confusion and impoverishment behind it; in many provincial towns and in whole counties the plague of that or the following years made the people unable, supposing that they had been willing, to take up the forced loan, and to furnish ships or the money for them. https://books.google.com/books?id=tXwaAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA512&lpg=PA507&focus=viewport&dq=plague+of+1625&output=text A History of Epidemics in Britain, Vol. 1, by Charles Creighton, 1894

On June 13, King Charles met his bride Henrietta Maria at Dover, and then sailed up the Thames to Greenwich by June 19, where he was urged to come no further toward London because of the plague. Parliament met in Westminster until early July, but thereafter at Richmond and Oxford, because there was plague in Westminster.

Was there a Midsummer celebration on June 24, with the candlelight parade of masters and apprentices, or was it suspended that year for fear of plague? In the third week of June, there were “only” 293 plague deaths, a terrible epidemic, but nothing like they were about to experience.

Magistrates, government officials, merchants, ministers, doctors, the royal court, and every rich person fled London and its suburbs for the countryside. A Tuscan envoy wrote from Richmond: “The magistrates in desperation have abandoned every care; everyone does what he pleases, and the houses of merchants who have left London are broken into and robbed." On September 1, Dr Meddus, rector of St Gabriel's, Fenchurch Street, wrote: "The want and misery is the greatest here that ever any man living knew; no trading at all; the rich all gone; housekeepers and apprentices of manual trades begging in the streets, and that in such a lamentable manner as will make the strongest heart to yearn." The city an hour after noon was the same as at three in the morning in the month of June, no more people stirring, no more shops open. https://books.google.com/books?id=tXwaAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA512&lpg=PA507&focus=viewport&dq=plague+of+1625&output=text A History of Epidemics in Britain, Vol. 1, by Charles Creighton, 1894

But outside of London, the villages and farms and manors were terrified to accept the city people, who brought the plague with them, either on fleas and ticks in their possessions, or by their coughing and sneezing of the pneumonic plague. A magistrate was having his boots fitted, when the shoemaker fell dead at his feet. A woman fled London for Cumbria, and died the day she arrived. Some victims awoke healthy and died by the evening, and some lingered in agony for days. Woodcut images of the time show the skeleton of death riding along with the coach and horses as they flee the city. The citizens left by boats, both east and west on the Thames, and on foot. They had no shelter in the country, not even a barn, for no one would allow them to stay on their land. Undoubtedly, in this cold and rainy summer of the Little Ice Age, many died of exposure, typhus, or dysentery, rather than plague. One man took his seven children with him out of the city, but when all seven children died, he moved back to his home.

“They [the Londoners] are driven back by men with bills and halberds, passing through village after village in disgrace until they end their journey; they sleep in stables, barns and outhouses, or even by the roadside in ditches and in the open fields. And that was the lot of comparatively wealthy men. Taylor says that when he was with the queen's barge at Hampton Court and up the river almost to Oxford, he had much grief and remorse to see and hear of the miserable and cold entertainment [hospitality] of many Londoners:"The name of London now both far and near

Strikes all the towns and villages with fear.

And to be thought a Londoner is worse

Than one that breaks a house, or takes a purse....

Whilst hay-cock lodging with hard slender fare,

Welcome, like dogs into a church, they are.

For why the hob-nailed boors, inhuman blocks,

Uncharitable hounds, hearts hard as rocks,

Did suffer people in the field to sink

Rather than give or sell a draught of drink.” https://books.google.com/books?id=tXwaAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA512&lpg=PA507&focus=viewport&dq=plague+of+1625&output=text A History of Epidemics in Britain, Vol. 1, by Charles Creighton, 1894

In the city, quacks posted handbills about their cures. Church bells tolled relentlessly for funerals, so no one knew the hours of the day. Coffin makers did a booming business, as did the men who slaughtered tens of thousands of dogs and cats in the city. Of the sick, some raved in delirium, some cried with pain from the buboes. Carts rumbled down the streets every day to pick up the dead, who were lowered from windows because the doors were sealed to isolate the sick from the well.

Plague cure by Thomas Sherwood, Practitioner in physick

"If any that are ancient or weak shall be infected

with the Pestilence, it shall not be necessary

to give them any purge, vomit, or sweat, or to let them bloud;

because they cannot beare the losse of so many spirits

as are spent by such evacuations. Therefore you may

lay upon the pit of the stomack of the sicke a young live puppy,

and if the sick can but sleep the space of

three or foure houres, they shall recover presently,

and the dog shall die of the Plague.

This I have known approved; and I do believe

that it will be a cure for all leane, spare, and weake

bodies both yong and old: provided, that the

dog be yonger then the sick."

"Poor people, by reason of their great want, living sluttishly, feeding nastily on offals, or the worst and unwholesomest meats, and many times, too, lacking food altogether, have both their bodies much corrupted, and their spirits exceedingly weakened; whereby they become (of all others) most subject to this sickness. And therefore we see the plague sweeps up such people in greatest heaps." https://books.google.com/books?id=tXwaAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA512&lpg=PA507&focus=viewport&dq=plague+of+1625&output=text A History of Epidemics in Britain, Vol. 1, by Charles Creighton, 1894

Churchyards’ ground level rose by several feet because the grounds were full. Fields and commons were designated as cemeteries. Many of us have seen illustrations and movies which show carts upended, and shrouded corpses sliding in a heap to the bottom of a pit. But modern archaeology has shown that to be untrue. The plague pits are arranged in orderly layers, with bodies laid out with feet toward the east, just as they’d be in a churchyard or crypt. They were buried in unmarked graves, but they were treated with respect. One has to wonder if the business of death left them with lifelong emotional trauma.

Weekly plague mortality bills for 1625

Weekly plague mortality bills for 1625 Plague deaths per mortality bills

Plague deaths per mortality bills(Christy K Robinson)

Deaths from plague fell precipitously when the winter frost set in. Who knows if it’s because the fleas died, or if the plague had taken all the weak it could and the survivors were immune. The government returned to London in November, and the coronation of Charles I and Henrietta Maria could be held on Feb. 2, before Lenten season.

Where was the 15-year-old William Dyer during the 1625 annus horibilis? Did he and the Blackbornes flee the city, or did they stay in Westminster at their home on Greene’s Alley? He was officially enrolled in the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers in August 1625 (retroactive to June 1624), the very peak of the plague, which would suggest that they stayed in (or returned to) London.

And what of his future wife, Mary Barrett, who was about 13 or 14 at this time? We don’t know. But with the descriptions we see above, we can imagine the horror and the conditions she would have known. Were she and William and the Blackbornes, and all the 35,000 people who emigrated to New England in the 1630s, blessed with genetic mutations that made them immune to plague, or did they somehow escape and avoid the dread diseases that preyed upon them?

The bubonic and pneumonic plague returned in 1630, propelled by the 30 Years War on the European continent, and ravaged London before spreading to the rest of the country. It killed 25 percent of the residents of Alford, Lincolnshire, including Elizabeth (age 3) and Susanna (age 16) Hutchinson, the daughters of Anne and William Hutchinson.

There were more epidemics of plague in 1635-36, and 1641, when 30,000 died of plague in London alone, and 1645, during the English Civil Wars. The final and most severe outbreak was in 1665, when about 100,000 people died. After the 1666 Great Fire, London was rebuilt with slightly better and less crowded conditions.

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on January 23, 2016 00:33

December 18, 2015

Behind THE DYERS books

The FIVE-STAR Dyer biographical novels are a dramatized narrative of meticulously-researched facts about their culture, their religious and political beliefs, their friends and enemies, the plagues and earthquakes and mysterious events of their lives--the things that meant everything to them but have lost their meaning to us, nearly 400 years later.

The FIVE-STAR Dyer biographical novels are a dramatized narrative of meticulously-researched facts about their culture, their religious and political beliefs, their friends and enemies, the plagues and earthquakes and mysterious events of their lives--the things that meant everything to them but have lost their meaning to us, nearly 400 years later.

You can't make snap judgments about what William and Mary Dyer did or believed, based on a Wiki article or a genealogy note in Ancestry. The research says something very different. It wasn't only the "big things" in their lives that tell the story. It was the countless "little things" of joy, faith, tragedy, risking their fortune and lives on transatlantic travel and settling the wilderness, changing their career path, gaining an education when many men and most women were illiterate, choosing freedom over oppression, having a large family and providing for their futures, creating a legacy of integrity and convictions that affects us in the 21st century.

Paper dolls available on Pinterest:

Paper dolls available on Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/138204282288915686/The Dyers and Hutchinsons were well-rounded, flesh-and-blood human beings with complicated relationships and a brilliant, long-term plan to create religious liberty, free speech, and free assembly for their society and ours. And even the people you'd think should be classified as villains led lives of great sacrifice and hard work, love and grief. Their families loved them and they did what they did from deep conviction.

In these Dyer books by Christy K Robinson, you'll get to know Mary and William Dyer, Anne and William Hutchinson, John Cotton, Edward Hutchinson, Katherine Marbury Scott, John Winthrop, John Clarke, Henry Vane, and many others not as historical icons, but as friends. Not as paper dolls, but real, four-dimensional human beings who lived and loved and sorrowed. As our spiritual, political, and (in some cases) physical forbears, they deserve the respect of having their stories told as truly as possible.

There was so much to cover, and so many important people who couldn't be left out, that it took two volumes (390 pages and 320 pages respectively) to tell the story. Mary Dyer Illuminated begins in 1629 and tells the story of why it was important to leave England and start over in the New World wilderness, and the first 20 years of their lives together. Volume 2, Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This , chronicles the 1650s with the awakening of liberty and human rights, their voluntary journey through persecution, and the prelude to Mary Dyer's hanging to bring attention to the gross miscarriage of civil and human rights. It concludes with a nonfiction timeline that ties off every character's story and life. The third volume, The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport , is nonfiction, a collection of images and short articles that explain the decisions made in the founding of New England.

You can order the Dyer books and reproduction letters at any time of the year, but if you're giving them as Christmas gifts, please note the deadlines in the photo captions.

Until Dec. 20, there's still time to order the Dyer books

Until Dec. 20, there's still time to order the Dyer books (or e-books) and have them delivered before Christmas! http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

If you order by Sunday night, Dec. 20, the Mary or William Dyer reproduction letters could make it to you on Christmas Eve. They ship by US Postal Service 3-day mail.

If you order by Sunday night, Dec. 20, the Mary or William Dyer reproduction letters could make it to you on Christmas Eve. They ship by US Postal Service 3-day mail.http://bit.ly/DyerHandwriting

Published on December 18, 2015 12:41

December 9, 2015

William and Mary Dyer handwritten letters

Order now for Christmas gift-giving. Just click the letter tab above, or

CLICK THIS LINK

to learn the history behind the letters, the size and price, and how long you should allow for the posters to arrive at your US address.

If you're giving this as a gift, allow yourself the time to purchase a 16x20" poster frame or a picture frame with a 16x20" opening for your poster(s). That's a common frame size, so it should be easy to buy from a hobby and art store, or order online. You won't need a mat.

If you're giving this as a gift, allow yourself the time to purchase a 16x20" poster frame or a picture frame with a 16x20" opening for your poster(s). That's a common frame size, so it should be easy to buy from a hobby and art store, or order online. You won't need a mat.

In a gold-painted frame with glass,

In a gold-painted frame with glass,

sitting on an easel. Charlotte hung her letters

Charlotte hung her letters

on the wall of her girl-cave.

If you're giving this as a gift, allow yourself the time to purchase a 16x20" poster frame or a picture frame with a 16x20" opening for your poster(s). That's a common frame size, so it should be easy to buy from a hobby and art store, or order online. You won't need a mat.

If you're giving this as a gift, allow yourself the time to purchase a 16x20" poster frame or a picture frame with a 16x20" opening for your poster(s). That's a common frame size, so it should be easy to buy from a hobby and art store, or order online. You won't need a mat.  In a gold-painted frame with glass,

In a gold-painted frame with glass,sitting on an easel.

Charlotte hung her letters

Charlotte hung her letterson the wall of her girl-cave.

Published on December 09, 2015 14:57