Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 5

May 8, 2018

Kirkby La Thorpe’s Church of St. Denys

© 2018 Christy K Robinson

Photos by Roy Hackford, used by permission. Click to enlarge photos.

Church of St. Denys, view from southwest. It’s fascinating to learn the history of a place or a building that we see as a static, finished piece of fabric, and realize that it’s been changing for a thousand years or more, as generations of people have come and gone. It will continue to change during our lives and after we're gone.

Church of St. Denys, view from southwest. It’s fascinating to learn the history of a place or a building that we see as a static, finished piece of fabric, and realize that it’s been changing for a thousand years or more, as generations of people have come and gone. It will continue to change during our lives and after we're gone. The village of Kirkby La Thorpe, Lincolnshire, was the birthplace of William Dyer, 1609-1677, the polymath and accomplished man who married Mary Barrett Dyer.

Whether or not you're related to anyone who lived in this sleepy English village, it's enlightening to learn that what happened to this church also happened to large and small churches all over the British Isles for your ancestors. Churches were built and altered and enlarged in stages, and it's fair to say that those changes were part of the fabric of our ancestors who sent their experiences and DNA down the years to all of us.

The church in Kirkby La ThorpeThe church of St. Denys (a martyred evangelist) is listed as Grade II*, included among “particularly important buildings of more than special interest.” At this time, in 2018, the church is closed to services and undergoing repairs, so when Roy Hackford, a Lincolnshire history buff, agreed to take interior photos for me if he could get the key, he found it cluttered with boxes and banners, chairs askew, kneelers pushed aside, and the curtains slung over the rood screen. These photos are the first interior views available, ever, on the internet. (I’ve searched for interior shots for more than 10 years, trust me!) So please look past or through the repairs and painting supplies, to the “bones” of the ancient building, and send good thoughts to the parish, in hope of a day soon, when the church is once again the center of peace and beauty. It would be wonderful to have a pictorial update.

If this is the same church key used 400 years ago, it was

If this is the same church key used 400 years ago, it was held by William Dyer the Elder, the churchwarden.

Who lived in Kirkby La Thorpe:William Dyer the Elder, and his wife (unknown name at this time). He was a yeoman farmer (meaning he owned property instead of being a tenant) and churchwarden (he was literate) of Kirkby La Thorpe in 1609-1610. Birth and death unknown.Son, Nicholas Dyer, born 1606.Son, William Dyer, baptized September 19, 1609 in the church of St. Denys on Church Lane. Probably attended the Carre School in Sleaford, took London apprenticeship in 1624; married Mary Barrett in 1633; emigrated to Massachusetts in 1635; co-founded Newport, Rhode Island 1639; became clerk, secretary of state, recorder, general solicitor, first attorney general in all of America, naval commander in Anglo Dutch War, etc.; haberdasher, mariner, farmer, father of seven; died 1677 in Newport, RI. Daughter, Margret Dyer, born about 1610.

Kirkby La Thorpe is a village on the Boston Road between Sleaford and Boston, Lincolnshire. It’s a linear village (along a single road) in the fenlands of eastern England, with houses built along a low ridge. The church of St. Denys, at the end of Church Lane, is the highest point, which makes sense as a place of refuge in times of flooding.

Kirkby La Thorpe is a village on the Boston Road between Sleaford and Boston, Lincolnshire. It’s a linear village (along a single road) in the fenlands of eastern England, with houses built along a low ridge. The church of St. Denys, at the end of Church Lane, is the highest point, which makes sense as a place of refuge in times of flooding. The village has existed at least since Iron Age times, and there was a Saxon settlement, seen in ditch and bank earthworks across the road from the church. There may have been three medieval manors in this parish, according to the Domesday Book. The nearby fields have ridges and furrows called selions, that remain from medieval partition of farmlands, and their plowing practices.

Photo copyright Christy K Robinson The chief businesses were the wool industry, fowling (waterfowl for meat and feathers), and agriculture. Today, there are crops and seed companies still in the area. If you’ve seen images of “fields of gold,” as in the song by Sting, you’re seeing the yellow flowers of the rapeseed plant whose seeds become feed for animals and canola oil for humans. The town of Boston, about 15 miles to the east, was the port through which wool was exported to weavers in the Netherlands and Flanders in medieval and renaissance periods.

Photo copyright Christy K Robinson The chief businesses were the wool industry, fowling (waterfowl for meat and feathers), and agriculture. Today, there are crops and seed companies still in the area. If you’ve seen images of “fields of gold,” as in the song by Sting, you’re seeing the yellow flowers of the rapeseed plant whose seeds become feed for animals and canola oil for humans. The town of Boston, about 15 miles to the east, was the port through which wool was exported to weavers in the Netherlands and Flanders in medieval and renaissance periods. Once upon a timeAt various times after the Norman Conquest in 1066-67, the church in Kirkby La Thorpe belonged to Earl Morcar; and 20 years later, King William I and the Bishop of Durham shared revenues in equal portions.

It is suggested that there was a high status pre-Conquest church in Kirkby la Thorpe, due to the place-name and the presence of Saxon sculpture. The 'kirk' element of the name is normally that given by the Danes to villages in which the Danes found a church on their arrival, which suggests that there was an important pre-Conquest church in Kirkby. Paul Everson and David Stocker. 1999. Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture. Lincolnshire. page 74. https://www.lincstothepast.com/St-Denys--church-and-churchyard/239393.record?pt=S

There were two churches in Kirkby’s area, but the church of St. Peter, which may have had a monastic function, was closed in 1593, sixteen years before William Dyer was born. It was demolished in 1637, the year he was disfranchised in Massachusetts Bay and Mary had the anencephalic fetus.

Description of church interior

View of the nave and tower arch from the chancel. The nave is the largest space of the church building, and it’s where the pews or chairs are set (for the last 400 years). From the 16thcentury and back, the congregation stood for service or Mass. On 16 October 1246, King Henry III granted a market and fair to the Hospitallers at the Kirkby manor, and the fair was held annually on 25 July at the manor. However, church naves in many towns were the place to strike deals, buy and sell livestock, and a community gathering place for social events, proclaiming the will of the government, and organizing workers for the strip farms in the area. That’s a good reason to screen the chancel and altar from the nave. They didn’t consider the often-secularly used building to be the “church,” in the biblical sense of church. The church was the people.

View of the nave and tower arch from the chancel. The nave is the largest space of the church building, and it’s where the pews or chairs are set (for the last 400 years). From the 16thcentury and back, the congregation stood for service or Mass. On 16 October 1246, King Henry III granted a market and fair to the Hospitallers at the Kirkby manor, and the fair was held annually on 25 July at the manor. However, church naves in many towns were the place to strike deals, buy and sell livestock, and a community gathering place for social events, proclaiming the will of the government, and organizing workers for the strip farms in the area. That’s a good reason to screen the chancel and altar from the nave. They didn’t consider the often-secularly used building to be the “church,” in the biblical sense of church. The church was the people. On the south wall of the nave (the good side, not the demon side), there is a 13th century piscina, a basin built into the wall where holy water was kept, to cleanse the plate and cup used for the Eucharist. This one has a plain, pointed arch molding around it.

The 1925 organ is in the north aisle. You can

The 1925 organ is in the north aisle. You cansee the romanesque (Norman) arches and pillars

behind the Victorian-era pews.A four-bay arcade (meaning four arches along the sides of the nave, where the congregation stood or sat) is “transitional,” a period between Norman and English Gothic. The arcade arches are almost round, indicating a Norman origin. The pillars and capitals are round and currently undecorated, though they may have been brightly painted in medieval times.

There is a north aisle on the other side of the arcade, and on the exterior, there are buttresses to carry the weight of the lead roof down to the ground. The small pipe organ in the north aisle is a “Premier” Organ built in 1925 by Cousans, who say that "These models were particularly popular in smaller churches because of their small dimensions but big sound."

The church was restored in the 19th century, and much of the stone floor looks very plain, compared to hundreds of other churches this old. It was probably originally tiled in four-inch black and red ceramic tiles as seen all over the UK, and an educated guess is that many clerics and local people would have been buried in a sub-floor crypt, facing east toward Christ’s second coming.

View of the nave (foreground), chancel and pulpit (right),

View of the nave (foreground), chancel and pulpit (right), north aisle with early windows (left), and oak prayer desk beneath the

niche for access to the rood screen (center). An oak prayer desk (as distinguished from the lectern and the pulpit) sits on the step of the chancel, under the nook where the rood screen stretched across the chancel. A description calls the desk "made from C14 bench ends decorated with blank cusped panels and fleur de lysterminals." I haven't seen when the desk may have been built, but perhaps during a renovation of the mid-19th or early-20th century.

Memorials

There are painted-glass windows to the memory of Rector John Gorton and Alfred Anders, as well as a brass plaque for Maria Adamson. Although the painted glass is dated to the 1911 restoration of the chancel, the east window of the north aisle is said to contain bits of medieval glass.

There are painted-glass windows to the memory of Rector John Gorton and Alfred Anders, as well as a brass plaque for Maria Adamson. Although the painted glass is dated to the 1911 restoration of the chancel, the east window of the north aisle is said to contain bits of medieval glass. A glassed and framed print remembers the service of local men in the Great War (WWI). There’s a pedimented ashlar wall plaque to William Willerton, d.1845. In the reveal of the chancel south window, a small rectangular brass plate records the charitable donations of the Rev. Thomas Meriton, d.1685. If there were ever medieval effigies in a village parish church like St. Denys, it’s doubtful, because they’d have preferred grander churches like St. Andrew’s in Ewerby, or a church in Heckington, Sleaford, Boston, or Lincoln.

St. Denys churchyard near the porch.Outside, there are numerous slate headstones, but the earliest inscriptions to be seen date back to the early 1800s. The church website notes that there is still plenty of space for burials in the churchyard. And because the church site is more than a thousand years old—perhaps 1,400 years—there are probably hundreds of unmarked burials outside, and some under the church floor.

St. Denys churchyard near the porch.Outside, there are numerous slate headstones, but the earliest inscriptions to be seen date back to the early 1800s. The church website notes that there is still plenty of space for burials in the churchyard. And because the church site is more than a thousand years old—perhaps 1,400 years—there are probably hundreds of unmarked burials outside, and some under the church floor. We don’t know what happened to William Dyer’s immediate family after his sister Margret was baptized in 1610. There are no more records. They may have died in a plague, lost their land in economic upheaval of the era, or sold up and moved away. But it’s also possible that the churchwarden and his wife are buried in or just outside the church of St. Denys.

South door and porch

Wooden south door to the church, with

Wooden south door to the church, with rounded Norman-era arch overhead. The

arch may be 1,000 years old. The south door of the church has a Romanesque, barrel-shaped tympanum over the door, which was common in Norman churches of the 11th and 12th centuries. Couples were wed in the doorway of a church, then moved inside to the altar rail to take Mass or Communion. To the right of the wooden door is a niche called a stoup where people dipped their fingers into holy water before entering.

Church towerSt. Denys’s west tower is not tall, but it has crenellations at the parapet that make it look like a defensive castle wall. It also has four crocketed pinnacles for decoration. On the south face is a two-light 16thcentury window. On the west is a three-light tall window from the 14thcentury which provides light to the tower’s interior. Also on the west face, below the molding between the first and second stages of the tower, are two fragments of 10th century (that’s right—the 900s!) two-strand interlacing carving, which may be pieces of the arms of a Saxon cross or gravestone. (I’ve zoomed in on the tower, and can’t make out the carving, which has had a thousand years of weathering.) An 1872 gazetteer of the county says that the tower had three bells.

The west and south aspects of

The west and south aspects ofthe tower.

Saxon Christians developed the square church towers we expect to see on very old English churches. If the Danes came raiding, the tower could be used as a lookout, and villagers could take refuge in the strong stone tower, much like a castle keep. When the Normans invaded and conquered in the 11thcentury, they burned wattle-and-daub structures, but used the massive stonework of the square church towers, or copied their style. John Marshal, in the 12thcentury, was injured by melting roof lead that dripped down on his face while he was defending a church tower from the military forces of King Stephen.

Other architectural historians discredit the defensive theory, saying that there are church towers in valleys, or places where a watchtower was of little value, and the battlements (like St. Denys’s crenellations and crocketed—decorated with hook-like ornaments—spires), were made several centuries later than the shaft and base of the tower.

So square stone towers may have been defensive, landmarks for travelers, lookouts, or simply held a bell or two to mark time, toll for funerals, or call an alarm.

The devil’s door?

Blocked door

Blocked door on north exterior of church. This doorway on the north side of St. Denys is blocked up with stone, matching many churches around the UK. One pre-Reformation medieval belief was that the north side of a church was cold (it was shaded, of course, in winter), and that no one good was buried on the north side of the church, being a less desirable burial place for dodgy people like criminals, the very poor, or illegitimate children. At baptisms, with the font located at the back of the church, the custom was to open both the south and north doors, so any evil spirit that came out of the baptized infant would fly out the north door as the Holy Spirit entered the baby through the warm, sunny south door. This part of the baptismal service in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer pinpoints that belief: I COMMAUNDE thee, uncleane spirite, in the name of the father, of the sonne, and of the holy ghost, that thou come out, and departe from these infantes, whom our Lord Jesus Christe hath vouchsaved, to call to his holy Baptisme, to be made membres of his body, and of his holy congregacion. Therfore thou cursed spirite, remembre thy sentence, remembre thy judgemente, remembre the daye to be at hande, wherin thou shalt burne in fyre everlasting, prepared for thee and thy Angels. And presume not hereafter to exercise any tyrannye towarde these infantes, whom Christe hathe bought with his precious bloud, and by this his holy Baptisme calleth to be of his flocke.

The devil's door, which in some churches was as small as 18 inches across, was blocked up after the English Reformation to discourage the superstition.

The two fonts

The older, 14th century font:

The older, 14th century font: 700+ years of baptisms!

A font is a stone basin on a pedestal, where infants are baptized either by immersion or anointing. Fonts are usually placed at the back of the nave, where the baby begins the journey of the Christian life, ending at the chancel with the altar and the Eucharist (Communion).

In St. Denys, there are two fonts, both octagonal. At the moment, one font is in the back of the church, and has a flat cover added in the 18thcentury. The stone font is said to be 14th century (during the reigns of Edward II and III and the visitation of the Black Death), with cusped square panels containing blank shields. Perhaps the shields were painted when new.

The "younger" font is still

The "younger" font is still600 years old.

The other font is 16th century (the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth), and has a conical wood cover. It is set in the corner of the north aisle near a heater. It has blank traceried panels and sunk spandrels, plain shields and quatrefoils to the stem. Quatrefoils look like four-leaf clovers and represent the four Evangelists of the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. They also symbolize good luck.

One font would have belonged to St. Denys's church, and the other is from St. Peter’s church that had been closed in the late 1500s. The St. Peter's font was, according to an old historical account, "long used as a sink in a small farm house, but has now been rescued from such degradation and stands in front of the parish school-house as a reminiscence of the lost church." Update that to show that the font is now in the care of St. Denys church.

There’s no way to know which was in use when William Dyer was baptized in September 1609, or his older brother’s and younger sister’s baptism. We can imagine his father the churchwarden, (perhaps his mother, but not likely) the minister, the godparents, and the parish members standing in a circle around a font, saying the baptism service in the Book of Common Prayer .

And then the Godfathers, Godmothers, and people, with the children muste be ready at the Church dore…DEARE beloved, forasmuche as all men bee conceyved and borne in sinne, and that no manne borne in synne, can entre into the kingdom of God (except he be regenerate, and borne anewe of water, and the holy ghost) I beseche you to call upon God the father through our Lord Jesus Christ, that of his bounteouse mercy he wil graunt to these children that thing, which by nature they cannot have, that is to saye, they may be baptised with the holy ghost, and receyved into Christes holy Church, and be made lyvely membres of the same.

Here shall the priest aske what shall be the name of the childe, and when the Godfathers and Godmothers have tolde the name, then shall he make a crosse upon the childes forehead and breste, saying.Receyve the signe of the holy Crosse, both in thy forehead, and in thy breste, in token that thou shalt not be ashamed to confesse thy fayth in Christe crucifyed, and manfully to fyght under his banner against synne, the worlde, and the devill, and to continewe his faythfull soldiour and servaunt unto thy lyfes ende. Amen.

[More…]

Ceiling and roof

View of the chancel window and

View of the chancel window and wood ceiling over the nave.In 1881, The Antiquary magazine said,

This church is in "a most lamentable condition," to use the words of the Bishop of Nottingham, the roofs in particular requiring prompt attention.The architectural surveys I read never mentioned the ceiling of the church, but Roy Hackford’s photos show nicely finished rafters and joints that look to be in excellent and uniform condition, so they must have been rebuilt or restored.

The roof consists of lead tiles over the chancel, and tile over the rest of the building. (That’s why it looks like there are two roof styles in exterior photos.)

Rood screen, stairs, loft The rood screen in St. Denys was carved wooden openwork stretching across the opening to the smaller chancel, from the nave. In medieval times, it may have been painted or gilded, with a crucifix of the Suffering Christ, and possibly small statues of saints (like St. Denys, for instance) or apostles. Its purpose was to separate the altar with its sacred objects from the non-clerical people. During the Lenten period, the rood was veiled, then revealed for Holy Week, when the Passion story was read to the congregation.

The 13th century rood screen is inside the tower.

The 13th century rood screen is inside the tower.It once separated the chancel from the nave.The rood stair (in the north aisle) leads to the rood loft, a space that gave access for cleaning or veiling the rood screen. There’s a large niche high on the left wall of the chancel, which is the opening to the rood loft. In some churches (not St. Denys), the space was used instead as a hermitage.

The 13th century wooden screen is now installed at the tower arch at the rear of the nave. It seems to be used as a curtain rod to hide the opening to the tower. Many churches I’ve seen use the floor of the tower to store music, Sunday school materials, or cleaning supplies.

Most roods, whether stone or wood, were destroyed in the English Reformation iconoclasm and the Civil War a century later, but perhaps Kirkby La Thorpe was such a small parish that it was missed by soldiers.

William Dyer the churchwarden and his family have been obscured over time, except for the legacy to his remarkable son William, whose countless thousands of descendants are nearly all Americans.

The northeast view of St. Denys includes the blocked-up devil's door,

The northeast view of St. Denys includes the blocked-up devil's door, the north aisle, the buttresses that support the lead

roof, and the north side of the tower. Before the English Reformation,

the north side of the church was the undesirable place for burials.

Most people now wouldn't know that. But you do!

********** Thanks from this author, and the thousands of modern friends and descendants of William Dyer, go to Roy Hackford, who generously agreed to travel from his home in Boston, Lincolnshire, to Kirkby La Thorpe, and take photos on a lovely spring day. He scanned the images and emailed them to me in high resolution, which meant that I could zoom in on certain features and crop them for this article.

Also, thanks to Rev. Valerie Greene, MA, the rector of St. Denys, for opening the church to Roy for photographs after I emailed her for permission. **********

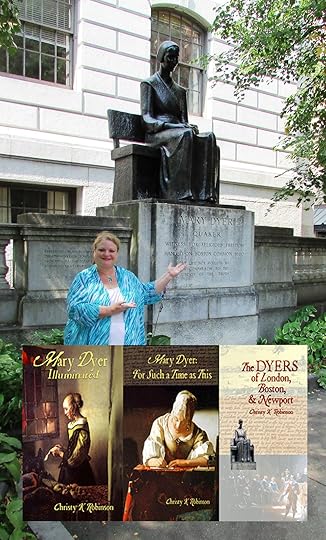

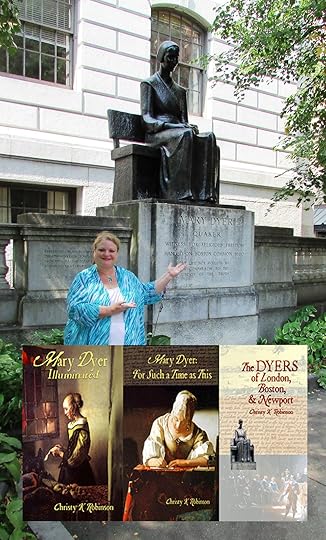

Christy K Robinson is author of the books:

Christy K Robinson is author of the books:· We Shall Be Changed (2010)

· Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)

· Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)

· The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014)

· Effigy Hunter (2015)

· Anne Hutchinson, American Founding Mother (2018)

If you enjoyed this study of a 1,000- to 1,400-year-old place of worship, you'll also enjoy

Effigy Hunter

, Christy K Robinson's five-star travel guide and handbook for the discovery of medieval burial monuments and places in UK and Europe. Said one reviewer:

If you enjoyed this study of a 1,000- to 1,400-year-old place of worship, you'll also enjoy

Effigy Hunter

, Christy K Robinson's five-star travel guide and handbook for the discovery of medieval burial monuments and places in UK and Europe. Said one reviewer: "The book you didn't know you needed, but you do! A must for medieval lovers."

Published on May 08, 2018 21:47

March 23, 2018

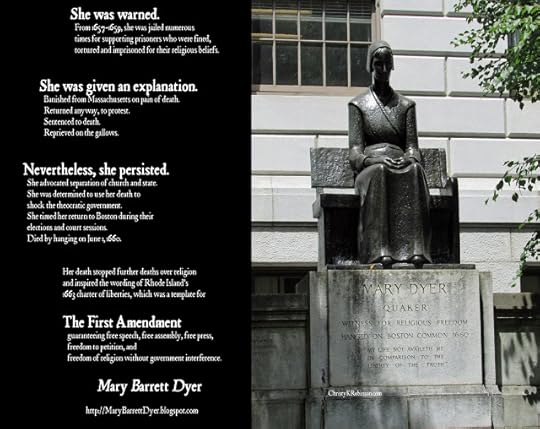

Mary Dyer featured in guest post on Americans United blog

© 2018 Christy K Robinson

Americans United, a religious liberty advocacy group, celebrates Women’s History Month, and I am honored that they posted my article on MARY BARRETT DYER (1611-1660) at their “Wall of Separation” blog <http://bit.ly/MaryDyerOnAU>. Feel free to share or use the Facebook/Twitter/Google+ buttons at the bottom of this post.

Though Mary Dyer was a deeply religious woman, she understood the life-and-death importance of liberty of conscience and the separation of church and state as a human right and protection of all believers and nonbelievers, from government imposing a narrow belief system or particular morals upon every person or group.

Though Mary Dyer was a deeply religious woman, she understood the life-and-death importance of liberty of conscience and the separation of church and state as a human right and protection of all believers and nonbelievers, from government imposing a narrow belief system or particular morals upon every person or group.  Christy K Robinson is author of the books:

Christy K Robinson is author of the books:· We Shall Be Changed (2010)

· Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)

· Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)

· The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014)

· Effigy Hunter (2015)

· Anne Hutchinson, American Founding Mother (2018)

Published on March 23, 2018 09:45

January 23, 2018

Life sketch of Capt. Roger Clapp

© 2018 Christy K Robinson

An unusual place to find an emotional declaration of love: a 17th-century Puritan. I thought Roger Clapp was a relative, but as it turns out, he’s the father-in-law of my eighth great-grandfather. No relation. I still like him for his cheerful gratitude in the face of life-threatening harsh conditions.

Capt. Roger Clapp arrived in Massachusetts Bay two months before Gov. John Winthrop did in 1630, resided in Dorchester, Mass., and was captain of the Castle Fort at Boston Harbor.

Click the link to read about Roger Clapp.

< http://bit.ly/2n4j5DH > (This is my devotional blog, so it has a religious bent. If that is not to your taste, I hope you'll still appreciate the historical context.)

In his Memoir, Roger Clapp mentioned the Antinomian Controversy, which involved Rev. Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson, as well as Anne's followers including William and Mary Dyer. Even though Clapp found a true love of Christ in his Puritan church of Dorchester, he had hard feelings for the Hutchinson group, and later on the Quakers. Like his ministers and fellow church members, he thought that grace and forgiveness meant that one thanked God by keeping the Old Testament laws to the best of their abilities.

In his Memoir, Roger Clapp mentioned the Antinomian Controversy, which involved Rev. Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson, as well as Anne's followers including William and Mary Dyer. Even though Clapp found a true love of Christ in his Puritan church of Dorchester, he had hard feelings for the Hutchinson group, and later on the Quakers. Like his ministers and fellow church members, he thought that grace and forgiveness meant that one thanked God by keeping the Old Testament laws to the best of their abilities.

The Antinomians believed that the Old Testament laws (all the laws, including the Ten Commandments), had been fulfilled with the cross of Christ, and that the new "law" was explained in the New Covenant of Hebrews 8, that God would reveal his will in the minds and hearts of his people. That Puritan Calvinism-versus-New Covenant believers is still debated in churches of the 21st century. And why wouldn't it be, with so many American denominations forming and reforming in northeastern American colonies and states?

This is what Roger Clapp said about the Controversy with the Wheelwright-Hutchinson faction, without naming names:

An unusual place to find an emotional declaration of love: a 17th-century Puritan. I thought Roger Clapp was a relative, but as it turns out, he’s the father-in-law of my eighth great-grandfather. No relation. I still like him for his cheerful gratitude in the face of life-threatening harsh conditions.

Capt. Roger Clapp arrived in Massachusetts Bay two months before Gov. John Winthrop did in 1630, resided in Dorchester, Mass., and was captain of the Castle Fort at Boston Harbor.

Click the link to read about Roger Clapp.

< http://bit.ly/2n4j5DH > (This is my devotional blog, so it has a religious bent. If that is not to your taste, I hope you'll still appreciate the historical context.)

In his Memoir, Roger Clapp mentioned the Antinomian Controversy, which involved Rev. Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson, as well as Anne's followers including William and Mary Dyer. Even though Clapp found a true love of Christ in his Puritan church of Dorchester, he had hard feelings for the Hutchinson group, and later on the Quakers. Like his ministers and fellow church members, he thought that grace and forgiveness meant that one thanked God by keeping the Old Testament laws to the best of their abilities.

In his Memoir, Roger Clapp mentioned the Antinomian Controversy, which involved Rev. Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson, as well as Anne's followers including William and Mary Dyer. Even though Clapp found a true love of Christ in his Puritan church of Dorchester, he had hard feelings for the Hutchinson group, and later on the Quakers. Like his ministers and fellow church members, he thought that grace and forgiveness meant that one thanked God by keeping the Old Testament laws to the best of their abilities. The Antinomians believed that the Old Testament laws (all the laws, including the Ten Commandments), had been fulfilled with the cross of Christ, and that the new "law" was explained in the New Covenant of Hebrews 8, that God would reveal his will in the minds and hearts of his people. That Puritan Calvinism-versus-New Covenant believers is still debated in churches of the 21st century. And why wouldn't it be, with so many American denominations forming and reforming in northeastern American colonies and states?

This is what Roger Clapp said about the Controversy with the Wheelwright-Hutchinson faction, without naming names:

But this glorious Work of God towards his People here was soon maligned by Satan; and he cast into the minds of some corrupt Persons, very erroneous Opinions, which did breed great Disturbance in the Churches. And he [Satan] puffed up his Instruments with horrible Pride, insomuch that they would oppose the Truth of God delivered Publickly: and some times, yea most times they would do it by way of Query, as if they desired to be informed: but they did indeed accuse our godly Ministers of not preaching Gospel, saying they were Legal Preachers, but themselves were for free Grace, and Ministers did Preach a Covenant of Works; which was a false Aspersion on them. The Truth was, they would willingly have lived in Sin, and encouraged others so to do, etc. And yet think to be saved by Christ, because his Grace is free; forgetting (it seems) that those whom Christ doth save from Hell, he also freely of his Grace doth save from Sin; for he came to save his People from their Sins, to give Repentance and Remission of Sins.Clapp described the home meetings of Anne Hutchinson, and her accusations that most ministers preached a Covenant of Works (having to earn salvation with good works) instead of the Covenant of Grace (faith alone in the gift--grace--of Christ's saving power) she said Rev. John Cotton preached. But Cotton would turn his back on Hutchinson, his friend of 20 years, in the early autumn of 1637, when he was pushed to conform to the orthodoxy of New England Puritanism.

Published on January 23, 2018 14:13

December 23, 2017

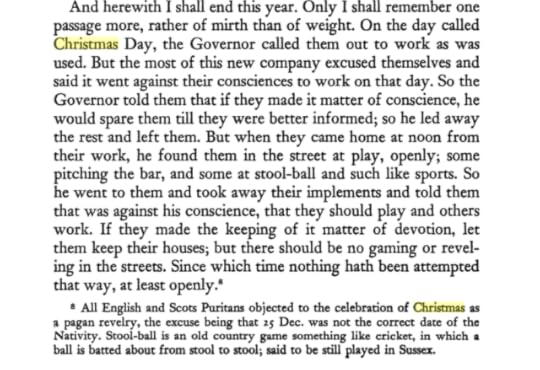

The 17th century war on Christmas

From Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647, by William Bradford, governor of Plymouth Colony. He was writing of Christmas, 1621.

From Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647, by William Bradford, governor of Plymouth Colony. He was writing of Christmas, 1621. Apparently, there was a "war on Christmas" long before Fox News' Bill O'Reilly invented one. Puritans, Pilgrim separatists, Presbyterians, Dutch Reformed, and almost every religious group in New England (except a few Anglicans and Catholics) treated Christmas as any other day on the calendar. I read a court record in the 1640s, where the Rhode Island colonial assembly met for regular business on Christmas, as reported by the Rhode Island Recorder, William Dyer.

So as the author of this William and Mary Barrett Dyer website, I wish you happy holy-days in whatever traditions and beliefs you and your family are free to cherish. The Dyers were part of the tapestry of religious liberty and freedom of conscience for all, that were encoded as freedom of religion and speech in the US Constitution.

So as the author of this William and Mary Barrett Dyer website, I wish you happy holy-days in whatever traditions and beliefs you and your family are free to cherish. The Dyers were part of the tapestry of religious liberty and freedom of conscience for all, that were encoded as freedom of religion and speech in the US Constitution. Peace,

Christy K Robinson

Published on December 23, 2017 09:40

November 27, 2017

Soe Scandalous a Life

Or: The Evolution of a Novelist

© 2017 Jo Ann ButlerI’d like to share a bit about myself by way of introducing my latest book, The Golden Shore. It joins Rebel Puritan and The Reputed Wife in my Scandalous Life series, homage to Rhode Island’s diverse origins, and also to one of its most notorious rebels, Herodias Long.I’ve been in love with colonial America for 45 years. The seeds of that love affair were planted by a 1961 National Geographic article about Pompeii. I was only 7, but I read that magazine to shreds. From that day on I longed to become an archeologist!My first dig was not in the shadow of Vesuvius, but at an 18th century mill village Connecticut. That summer I was immersed in the durable minutiae of colonial life – stuff people threw away or lost – as I excavated a cellar dug in the mid-1700s, then filled with 18th century trash after the house burned.Most of my finds were the stuff we leave behind at picnics today – bones, bottles, and food containers. Organic stuff – apple cores & such – decay quickly, but glass survives burial very well. I found scads of glass fragments, and a few intact bottles as well. Metal was precious, so they reused or reworked it, but pins, buttons, coins, nails, and children’s toys are easily lost, to be found by me.Ceramics were the plastics of the colonial world. Clay is cheap, widely available, and more easily shaped than molten glass, but earthenware is also fragile, especially porcelain and fine tableware. I found shattered plates, mugs, and storage jars by the bucket load. I went on to dig at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina, site of a Revolutionary War victory over the British, and then at the burned-out home of Robert Livingston, a New York signer of the Declaration of Independence. Do you see a trend here? I love colonial America, and can still guess the age of a ceramic chip by its glaze and design, a nail by its head and shank, and a bottle by tool marks on its neck and lip. I use that knowledge to set scenes and furnish Herodias Long’s home in my Scandalous Life series.Then I tore up a knee, and had to quit archeology. It wasn’t long before Mom and I took up genealogy – more colonial America! Mom’s ancestry is top-heavy with Rhode Islanders, most of them younger sons with no chance to inherit the family farm. They were given their portions and told, in essence, “Go west, young man.”Cast out, or trailblazing? My forefathers were Rhode Island’s founders, creating one town after another because, as one researcher quipped, nobody wanted to live with anybody else. In 1636 Roger Williams, champion of Rhode Island’s freedom of worship, was cast out of Salem, Mass., for heresy. Several families followed him, and they built Providence. A few years later, those who preferred Samuel Gorton’s firebrand preaching followed him south to build at Warwick.The Puritans left England because they didn’t want to live with Anglicans. In 1637 Anne Hutchinson’s heresy spurred them to eject her and her numerous followers, and they created Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Two years later, yet another factional schism sent a large group, including George Gardner and the Dyer family, to the far end of the island, where they built Newport. At the same time, John Hicks and his fourteen-year old wife Herodias arrived from Weymouth, MA, seeking new opportunities as described in Rebel Puritan. I am proud to claim Herodias and George Gardner as my most notorious ancestors. The child bride Herodias (Long) Hicks, or Herod, as I spell the shortened name she used, is the inspiration of my Scandalous Life series.

Butler's trilogy, screenshot from Amazon.

Butler's trilogy, screenshot from Amazon.The books are listed in reverse order.

The Gardners’ children, along with other second-generation Rhode Islanders, bought huge tracts of land from the Indians and built Kingstown on the western shore of Narragansett Bay. Their children prospered on that golden shore.George Gardner never left Newport to live in Kingstown, but Herod did. Though he was near 60, John Porter also left his home – and his aged wife – for Kingstown. Why? I set forth my thoughts in The Golden Shore.Genealogy led me to these intriguing persons, but when I work up a family line, I am never content with a list of names and birth dates. Why did a family leave a community – was it a shortage of land or a natural disaster? Were they exchanging one preacher for another? Were they seeking a fresh start or were they cast out? These are the sort of questions a novelist loves, and many are answered by town histories and colonial records.Each leaf I painted on my family tree added to my knowledge of New England’s history, politics, and what misbehavior was considered worthy of punishment. As the title of my series hints, Herod Long’s contemporaries considered her scandalous. Early genealogists agreed. They described her as erratic, impulsive, and neurotic. Perhaps so, but Herod had good reasons to feel cranky.

In Rebel Puritan, Herod gave a petition to Rhode Island’s governor in December 1643, begging to be divorced from John Hicks. She preferred to subject herself to any misery than to live with his abuse. Even though Governor Coddington found ample evidence of Hicks’ inhumane and barbarous behavior and cruel blows on divers parts of her bodie, he persuaded them to try married life again.Six months later Hicks had not reformed, as an order to pay a substantial bond to ensure his good behavior shows. Instead, he vanished, taking the couple’s young children with him. At the end of 1644 a letter surfaced from Hicks, now living on Long Island. He declared that he wanted nothing more to do with Herod, for the Knot of affecion on her part have been untied long since, and her whoredome have freed my conscience. Shortly thereafter, Herod was living with George Gardner, bore a son to him in 1645, and that is where Rebel Puritan ends._________________For a post about a land deed from William and Mary Dyer toGeorge Gardner in 1644, click HERE._________________A colonial soap opera, right? Yes, and no. I prefer a broader viewpoint, and include the tumultuous alliances and divisions of New England’s early history, largely forgotten these days.As for what drew me to Herod Long, I like kick-ass women, and her character shines over the 400 years and 11 generations that separate us. Also, looking at that big picture again, Rebel Puritan, The Reputed Wife, and now The Golden Shore let me explore the impact that our foremothers had on the formation of New England.What impact could colonial women have? After all, we’ve all heard that they lived humble lives. Married women couldn’t enter contracts, and very few were literate. Herod was typical when she signed documents with an X.Paintings of the first Thanksgiving depict Pilgrim women serving food (I can set a colonial table with ease thanks to my archeology background), but that’s not all they did. They gardened, sewed and spun, and cared for livestock, but they also defended their homes if need arose.With primitive forms of contraception deemed evil, women bore children one after another (with many births recorded only under the father’s name). Divorces due to abandonment, infidelity, or abuse were rare, but even an abusive man kept his children unless he didn’t want them. Herod lost her children when John Hicks abandoned her.

If a woman brought land to a marriage, it became her husband’s. Herod received an inheritance, but bitterly complained in a petition that John Hicks took it from her. Yes, he did, and it was completely legal. Women weren’t allowed to vote, but the same was true of men who weren’t approved by the town. Puritan colonies took it even further – men who were not church members could not vote, and they would not be admitted to membership if their beliefs were unorthodox.Women could be church members, but could not preach. When Anne Hutchinson critiqued Puritan sermons in her own home, Massachusetts’ government jailed and banished her, and her heretical soul was condemned to hell. The Puritans came to regret their actions, for that strong-willed woman’s charisma was responsible for the existence of Rhode Island. Before Anne Hutchinson’s exile, no Englishmen lived near Narragansett Bay, apart from a few traders and Roger Williams’ fledgling Providence. When Anne was cast out, some 80 families followed her, establishing towns on land they bought from the Narragansett Indians. The Puritan colonies – Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Connecticut – indignantly claimed the Narragansett Bay region, but King Charles I gave Rhode Island a charter anyway and validated its deeds.Mary Dyer, prominent in The Reputed Wife, was one of many Quaker missionaries who preached in defiance of law. Many Rhode Islanders were receptive to the Quakers’ message, but when they preached in Puritan colonies, they were punished with increasing severity. Herod Gardner carried her infant daughter 60 miles through wilderness to protest the whippings and brandings, and was herself jailed and whipped. Two years later, Mary Dyer and several Quaker men were hanged in Boston for defying banishment.

English Quakers reported the barbarities to the newly-enthroned King Charles II, already no friend of Puritans (who had deposed and beheaded his father). Especially horrified by the abuse of women, including Mary Dyer and Herod Gardner, he ordered the hangings to cease. Charles praised Rhode Island’s liberty of conscience – freedom to worship as one chose without molestation, upheld Rhode Island’s charter and protected them from encroachment by Puritan colonies.These women truly influenced American history. Anne Hutchinson’s popularity with liberal-minded colonists led directly to the creation of Rhode Island. The sacrifices of Mary Dyer, Herodias, and the other Quakers, influenced a king to support Rhode Island’s freedom of worship – a concept enshrined a century later in the Declaration of Independence.Unfortunately, it took much longer for women to gain legal rights, but their struggles are a dominant theme in my books. In The Golden Shore, Herod again faces the loss of her children and property to her husband – actually her unwed domestic partner of two decades, as she reveals to the court. What will she do to retain her independence, and what will she surrender for love? As we saw in Rebel Puritan and The Reputed Wife, Herod is capable of great sacrifice, and great strength.Many women endured horrible marriages because they feared their abusive husbands’ revenge, but though she faced impoverishment and humiliation, Herod Long stood up and said, “I want out.”In The Reputed Wife, Herod stood up to Massachusetts’ Puritan governor and said, “Torturing people for their beliefs is wrong.” Whether she acted from faith or pure humanity; Herod walked into harm’s way to defend them, knowing what would happen.In The Golden Shore, Herod stands up again when a relationship goes sour. She seeks a second legal separation, but it’s clear that she learned a lesson from John Hicks. This time she asks for ownership of land she worked for, child custody, and support for her youngest daughter.Genealogists are familiar with these details of Herod Long’s life, but I won’t reveal any more secrets here. However, in The Golden Shore I sought solutions that work for everyone, and leave my characters as friends – and more. Hopefully they will leave readers content as well.*******

Jo Ann Butler is an archaeologist, musician, 17th-century researcher, and the author of three books and numerous articles on early-colonial America. She lives in Fulton, New York. Her website is http://rebelpuritan.com/ and her Amazon author page is

HERE

.

Jo Ann Butler is an archaeologist, musician, 17th-century researcher, and the author of three books and numerous articles on early-colonial America. She lives in Fulton, New York. Her website is http://rebelpuritan.com/ and her Amazon author page is

HERE

.

Published on November 27, 2017 23:53

November 14, 2017

Announcing new Dyer book, by Johan Winsser

Occasional guest blogger, Johan Winsser, announces the publication of his scholarly study of Mary and William Dyer.

Winsser's book, published Nov. 13, 2017, is

Winsser's book, published Nov. 13, 2017, is available on Amazon, at

http://amzn.to/2zDhTyx

“An authoritative and careful biography of Mary Dyer and her husband, William, which breaks new ground, dispels common beliefs, and balances both the Quaker and puritan sides of the story.”—H. Larry Ingle, author of First Among Friends: George Fox and the Creation of Quakerism

“A well-researched and balanced work that makes a valuable contribution to our understanding of the people and issues of the seventeenth-century Atlantic world.”—Francis Bremer, author of John Winthrop: American’s Forgotten Founding Father

Mary Dyer is widely esteemed as one of the “Boston martyrs”— four Quakers hanged by the Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1659 and 1661. When she returned to Boston in 1660, after having been banished twice from Massachusetts, she committed an act of deliberate civil disobedience that cost her her life, led to the downfall of the puritan government, and advanced the fundamental principles of freedom of conscience and expression.

More than three-and-a-half centuries later, the state continues to exercise its mandate to preserve the peace and social order, while also protecting the constitutional exercise of free speech and self-expression. The challenge, always, has been to identify and then enforce the balance between the rights of individuals or groups to practice their beliefs,Breaking New Ground: A Partial List· Gloucestershire, Saint Martin’s, and the Dyer Origins· The Dyers and the London Antinomian Underground· The Case for William Dyre’s Previously Unidentified Brother· William Dyre’s Second Return to England· The Dyre Portrait· Mary Dyer, the Quakers, and the Limits of Toleration

*****Johan Winsser is a former college professor, telecommunications engineer, and competitive runner. He is the author of several academic articles related to Mary Dyer and early New England, and now pursues his interests as an independent scholar. He lives with his family in the Northwest Hills of Connecticut. For more information, visit http://www.dyerfarm.com.

*****Johan Winsser is a former college professor, telecommunications engineer, and competitive runner. He is the author of several academic articles related to Mary Dyer and early New England, and now pursues his interests as an independent scholar. He lives with his family in the Northwest Hills of Connecticut. For more information, visit http://www.dyerfarm.com.

Published on November 14, 2017 14:23

October 30, 2017

Test blog article

Checking the formatting for color changes on the links.

blah-blah-blah-blah

blah-blah-blah-blah

blah-blah-blah-blah

blah-blah-blah-blah

The End.

http://ChristyKRobinson.com

http://ChristyKRobinson.blogspot.com

blah-blah-blah-blah

blah-blah-blah-blah

blah-blah-blah-blah

blah-blah-blah-blah

The End.

http://ChristyKRobinson.com

http://ChristyKRobinson.blogspot.com

Published on October 30, 2017 19:31

Reflector ovens…in the 17th century?!

© March 9, 2012 by Carolina Capehart

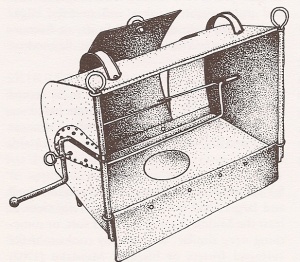

On Facebook recently [2012] there was quite a lively discussion, as well as plenty of oooohhhing and ahhhhhing, amongst my assorted friends about the tin (or is it copper?) reflector oven that’s depicted in the painting below:

This is entitled simply “The Cook.” It was done by the Dutch painter Gabriel Metsu (1629-1667) and was most likely completed by him at some point between 1657 and 1662.

Yes, you read that correctly: between the years 1657 and 1662. Indeed, Metsu was a mid-17th century painter.

Now, I’ll be the first to admit it: I thought these ovens were only in use during the 19th, maybe the very late 18th, century (at least here in America). I’m not really sure why. I’ve used them often, but I’ve never really given it much thought. I’ve never investigated whether they were available/used earlier. Of course, I’ve done quite a bit of 18th century hearth cooking, but my main focus has typically been the 19th. Not to mention, that’s the time period in which I was initially trained (at Conner Prairie, back when the year 1836 was the focus). However, based on this painting, apparently reflector ovens were around, even as early as the mid-1600s.

At the same time, though, it is a Dutch painting. So perhaps reflector ovens were common in Europe, even during the 17th century, but were they also used on this side of the pond? It seems likely that they may’ve been imported. Or perhaps they were made here. However, I think it is generally believed that being a tinsmith was more of an 1800s profession. You know, due to British control of manufactured goods, that sort of thing. Or, perhaps not? It’d definitely be interesting to research this further, and to look at store inventories, newspaper ads, ship records, and other assorted documents, to see if, and when, such ovens were made in, or transported to, the colonies.

In any event, when this painting and the ensuing discussion took place on Facebook, I remembered a passage I’d read in Prospect Books’ facsimile reprint of Hannah Glasse’s book, The Art of Cookery, made Plain & Easy (1747). In the glossary is this definition (and illustration) of “Tin Oven”: The reference to a tin oven, [on page] 91, is to the ‘Dutch oven’ which was in common use and which stood in front of the fire. The food being cooked was exposed to direct heat and also to reflected heat from the polished tin interior. A door in the back could be opened to permit viewing and basting.

Now, what’s interesting is that all the receipts on page 91 in Glasse’s book are for fish, and only one specifically calls for cooking the dish in “a Tin Oven.” It’s the receipt [recipe] “Salmon in Cases.” The instructions say to wrap salmon pieces in paper and “lay them on a Tin Plate.” It then states that “a Tin Oven before the Fire does best” (I imagine as opposed to a brick bake oven). Which, of course, obviously means that the fish is not put on the spit!

Now, what’s interesting is that all the receipts on page 91 in Glasse’s book are for fish, and only one specifically calls for cooking the dish in “a Tin Oven.” It’s the receipt [recipe] “Salmon in Cases.” The instructions say to wrap salmon pieces in paper and “lay them on a Tin Plate.” It then states that “a Tin Oven before the Fire does best” (I imagine as opposed to a brick bake oven). Which, of course, obviously means that the fish is not put on the spit!So, in a typical tin reflector oven, where would you put a plate of fish “in cases”? On the floor/bottom of it? But that puts it too low in relationship to the fire, yes? So, in order to gain some height, could the plate perhaps be balanced on top of the spit? Could that work, would it stay securely? (I’m thinking maybe, but not likely?) Then I thought, “Well, perhaps Glasse means one of those tin ovens with a shelf? The ones that are often used for small breads (either loose or in a pan)?” And if so, does that mean those types of tin ovens were also around in the early to mid 18th century? Makes perfect sense, yes? Or no? And so, is there possibly a slight problem with this glossary’s definition of “Tin Oven”: i.e. it’s not just the ones with a spit and basting door, but it’s also other types?

Luckily for me, I was scheduled to cook again at the hearth in the kitchen of the Israel Crane House on Sunday, March 1, which meant I’d be able to conduct my own experiments.

I could figure out just how this fish receipt was to be cooked. What fun!

So, stay tuned!

For the results of Carolina’s experiment with reflector ovens, along with photos, see her blog article: https://firesidefeasts.wordpress.com/2012/03/15/a-tin-oven-before-the-fire-does-best/

***** ***** *****

Carolina Capehart, who passed away in April 2017, dabnabit (one of her favorite words), was a friend of those of us who study and report on the 17th century. This is my remembrance of Carolina: http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2017/09/big-respect-for-departed-friend.html

Carolina Capehart, who passed away in April 2017, dabnabit (one of her favorite words), was a friend of those of us who study and report on the 17th century. This is my remembrance of Carolina: http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2017/09/big-respect-for-departed-friend.html

Published on October 30, 2017 16:50

October 19, 2017

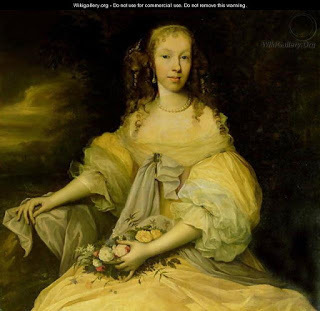

Clothing fashions during the Dyers' lifetimes--part 2

This post is the second of two, on fashions of the early and mid-17th century, during the lifetimes of William and Mary Barrett Dyer and Anne and William Hutchinson. I tried to cover the various social strata. Part one of the fashion parade is HERE.

25. 1630s: Posthumous Portrait of Mary Fielding,

25. 1630s: Posthumous Portrait of Mary Fielding,

by Anthony Van Dyck

26. Lady Penelope Nicholas Wearing a Brown Dress and White Chemise

26. Lady Penelope Nicholas Wearing a Brown Dress and White Chemise

27. 1630s: Portrait of Miss May, by John Michael Wright

27. 1630s: Portrait of Miss May, by John Michael Wright

28. 1637: Lucy Percy, Countess of Carlisle.

28. 1637: Lucy Percy, Countess of Carlisle.

Her husband was governor of Barbados.

29. 1638: Anne Carr, Countess of Bedford

29. 1638: Anne Carr, Countess of Bedford

30. 1640s: Frances, Lady Whitelock, 1614-1649, by Michael Dahl

30. 1640s: Frances, Lady Whitelock, 1614-1649, by Michael Dahl

31. 1649-Gloves worn to his execution by King Charles I

31. 1649-Gloves worn to his execution by King Charles I

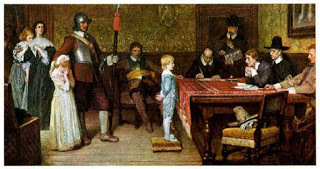

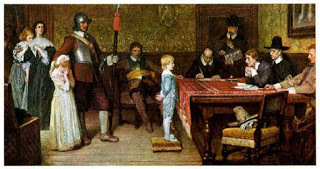

32. 1640s: A royalist's child is interrogated by Roundheads

32. 1640s: A royalist's child is interrogated by Roundheads

(puritans/parliamentarians) during the Civil Wars.

"When did you last see your father?"

33. 1640s-Esther Tradescant and son detail

33. 1640s-Esther Tradescant and son detail

34. English puritan children

34. English puritan children

35. Dutch colonists in New Netherland (New York)

35. Dutch colonists in New Netherland (New York)

36. 1640s-50s: Lady Elizabeth Cromwell, daughter of Oliver Cromwell

36. 1640s-50s: Lady Elizabeth Cromwell, daughter of Oliver Cromwell

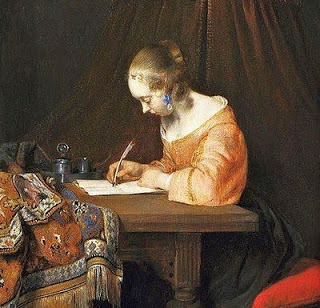

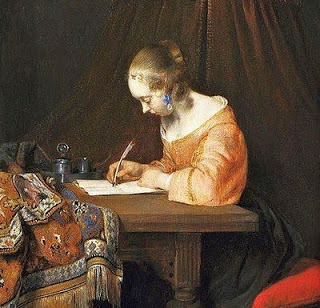

37. 1655: Woman Writing a Letter, by Gerard Terborch

37. 1655: Woman Writing a Letter, by Gerard Terborch

38. Woman Reading a Letter, by Jan Vermeer

38. Woman Reading a Letter, by Jan Vermeer

39. A woman arranging flowers, by William Bradford.

39. A woman arranging flowers, by William Bradford.

40. 1650s-60s: Lady Elizabeth Cromwell

40. 1650s-60s: Lady Elizabeth Cromwell

41. ca 1630s: Anna Dalkeith, Countess of Morton and Lady Anna Kirk

41. ca 1630s: Anna Dalkeith, Countess of Morton and Lady Anna Kirk

42. ca 1640s-50s: Anne Dudley Bradstreet, 1612-1672,

42. ca 1640s-50s: Anne Dudley Bradstreet, 1612-1672,

Massachusetts Bay Colony pioneer. Her father was

Governor Thomas Dudley, and her husband,

Simon Bradstreet, also became governor.

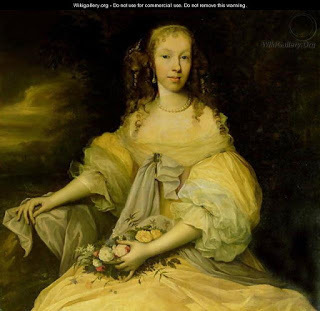

43. 1660: Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-feather Fan,

43. 1660: Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-feather Fan,

by Rembrandt

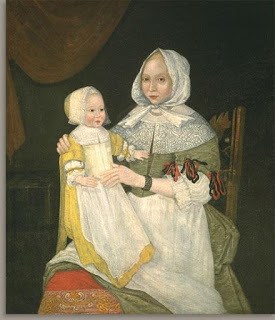

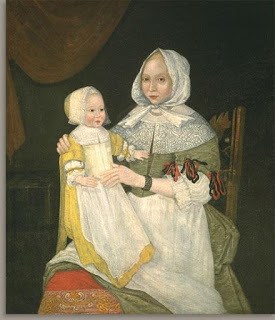

44. 1670s: Elizabeth Clarke Freake and Baby Mary

44. 1670s: Elizabeth Clarke Freake and Baby Mary

45. Netherlands family group: The Christmas Feast or St. Nicholas Feest, by Jan Steen.

45. Netherlands family group: The Christmas Feast or St. Nicholas Feest, by Jan Steen.

The puritan English did not observe Christmas, and no New Englanders

celebrated Christmas, as it was considered too close to Catholicism.

I like the details of new toys, new shoes, food treats, and all the children happy

but the boy--I wonder what disappointed him?

46. Late 1600s (or more likely early 1700s): An English family group.

Notice the extended family of grandparents, adult children, and grandchildren.

47. 1660s-Man and woman holding hands

47. 1660s-Man and woman holding hands

Mary Dyer Illuminated (Vol. 1)

Mary Dyer Illuminated (Vol. 1)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (Vol. 2)

The DYERS of London, Boston & Newport (Vol. 3)

All are available in paperback and Kindle at

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

25. 1630s: Posthumous Portrait of Mary Fielding,

25. 1630s: Posthumous Portrait of Mary Fielding, by Anthony Van Dyck

26. Lady Penelope Nicholas Wearing a Brown Dress and White Chemise

26. Lady Penelope Nicholas Wearing a Brown Dress and White Chemise  27. 1630s: Portrait of Miss May, by John Michael Wright

27. 1630s: Portrait of Miss May, by John Michael Wright  28. 1637: Lucy Percy, Countess of Carlisle.

28. 1637: Lucy Percy, Countess of Carlisle. Her husband was governor of Barbados.

29. 1638: Anne Carr, Countess of Bedford

29. 1638: Anne Carr, Countess of Bedford  30. 1640s: Frances, Lady Whitelock, 1614-1649, by Michael Dahl

30. 1640s: Frances, Lady Whitelock, 1614-1649, by Michael Dahl 31. 1649-Gloves worn to his execution by King Charles I

31. 1649-Gloves worn to his execution by King Charles I 32. 1640s: A royalist's child is interrogated by Roundheads

32. 1640s: A royalist's child is interrogated by Roundheads (puritans/parliamentarians) during the Civil Wars.

"When did you last see your father?"

33. 1640s-Esther Tradescant and son detail

33. 1640s-Esther Tradescant and son detail  34. English puritan children

34. English puritan children  35. Dutch colonists in New Netherland (New York)

35. Dutch colonists in New Netherland (New York)  36. 1640s-50s: Lady Elizabeth Cromwell, daughter of Oliver Cromwell

36. 1640s-50s: Lady Elizabeth Cromwell, daughter of Oliver Cromwell  37. 1655: Woman Writing a Letter, by Gerard Terborch

37. 1655: Woman Writing a Letter, by Gerard Terborch 38. Woman Reading a Letter, by Jan Vermeer

38. Woman Reading a Letter, by Jan Vermeer 39. A woman arranging flowers, by William Bradford.

39. A woman arranging flowers, by William Bradford. 40. 1650s-60s: Lady Elizabeth Cromwell

40. 1650s-60s: Lady Elizabeth Cromwell

41. ca 1630s: Anna Dalkeith, Countess of Morton and Lady Anna Kirk

41. ca 1630s: Anna Dalkeith, Countess of Morton and Lady Anna Kirk  42. ca 1640s-50s: Anne Dudley Bradstreet, 1612-1672,

42. ca 1640s-50s: Anne Dudley Bradstreet, 1612-1672, Massachusetts Bay Colony pioneer. Her father was

Governor Thomas Dudley, and her husband,

Simon Bradstreet, also became governor.

43. 1660: Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-feather Fan,

43. 1660: Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-feather Fan, by Rembrandt

44. 1670s: Elizabeth Clarke Freake and Baby Mary

44. 1670s: Elizabeth Clarke Freake and Baby Mary  45. Netherlands family group: The Christmas Feast or St. Nicholas Feest, by Jan Steen.

45. Netherlands family group: The Christmas Feast or St. Nicholas Feest, by Jan Steen. The puritan English did not observe Christmas, and no New Englanders

celebrated Christmas, as it was considered too close to Catholicism.

I like the details of new toys, new shoes, food treats, and all the children happy

but the boy--I wonder what disappointed him?

46. Late 1600s (or more likely early 1700s): An English family group.

Notice the extended family of grandparents, adult children, and grandchildren.

47. 1660s-Man and woman holding hands

47. 1660s-Man and woman holding hands Mary Dyer Illuminated (Vol. 1)

Mary Dyer Illuminated (Vol. 1)Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (Vol. 2)

The DYERS of London, Boston & Newport (Vol. 3)

All are available in paperback and Kindle at

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

Published on October 19, 2017 12:00

October 9, 2017

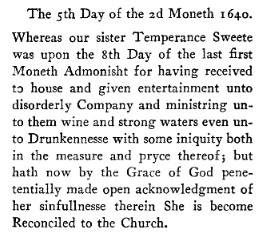

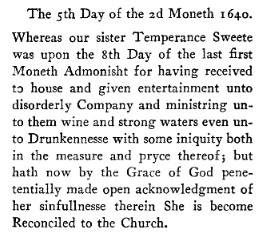

The intemperate Temperance Sweete and government discipline

© 2017 Christy K Robinson

For those of us raised practicing temperance (no alcohol use), this is ironic.

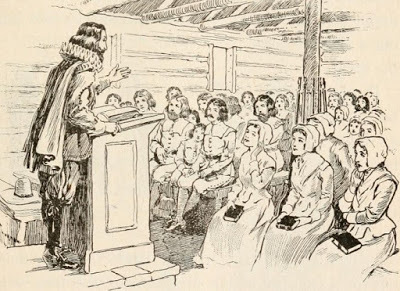

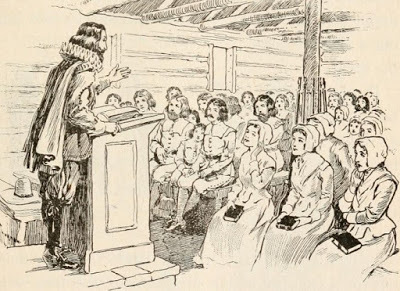

This slice of life is from the First Church of Boston,

This slice of life is from the First Church of Boston,

the Puritan congregation from which Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer

were cast out in 1638. The event happened two years later,

perhaps around the first of March, then her admonishment

was given on the 8th day of March (the first month on their calendar),

1640, and her restoration took place on the fifth of April.

Screen shot: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/62/

Temperance Sweete (one of those Puritan virtue names), a member of the church, was admonished for intemperance. Temperance was the wife of John Sweete, a ship's carpenter.

Her husband must have been at sea when she decided to have a party at home (not the licensed tavern, where women weren't allowed). She served wine and "strong waters" (whisky) and it looks like there was a standard pour amount and price that she exceeded. Venti instead of grande, perhaps. Not to mention, her raucous customers were drunk. Puritans drank all the time, but drunkenness was sinful. Their Geneva Bible said: And be not drunk with wine, wherein is excess: but be fulfilled with the Spirit. Ephesians 5:18.

It sounds as if they were drunk on wine and spirits. (Be sure to lift your eyebrows here, as a proper Church Lady would.)

Temperance's admonishment (probably quite the shaming sermon in front of the congregation at beginning and end of her time) lasted a month. We can almost be sure that the sermon would have made pokes at her name.

Church members submitted to the "laws of Christ" and to oversight of their fellow members. The church as a body desired to be purified from the world and sanctified holy to the Lord. The point of coming under church discipline was not to cast out the wicked, but to remove them from fellowship and possible contamination of other members for a time. They were to examine their behavior, and they could be visited by their ministers and elders. (This is how Anne Hutchinson was treated while under house arrest in the winter of 1637-38, before her excommunication trial.) Then, if they were properly penitent, they could be brought back into full membership privileges, allowed to take Communion, and if they were men, to vote. If they lost their membership, they were still required to attend services and pay tithes to the church and fines to the government, and they couldn't vote.

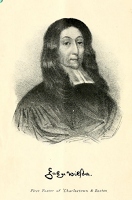

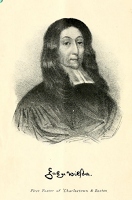

Rev. John Wilson,

Rev. John Wilson,

minister of Boston

First Church of Christ.Being a member of the church was a serious matter. It showed that you might be one of the Elect, the people predestined to salvation who showed their salvation by doing good works. After a short life on earth, they were concerned about the soul's eternity in heaven and not in hell.

Even the ministers were not immune to censure or admonishment. Rev. John Wilson, senior pastor of Boston First Church, had been in England for three-quarters of a year and had recently returned to Boston. Perhaps feeling like he hadn't been missed and Cotton had taken over, he stirred up negativity against the very popular Rev. John Cotton, the teacher of the same church. When Cotton and his faction got their hackles up and demanded censure of Wilson, Cotton graciously turned the situation to one of church unity. Men dunk a suspected witch in a mill pond.

Men dunk a suspected witch in a mill pond.

If she was not a witch,

she'd drown and go to heaven. If she was a witch,

she'd float, rejected by the cleansing water,

and then she'd be hanged and go to hell. Note the

black demons in the water and on shore.

There were people who were not allowed into membership, and some of them committed suicide because of their despair. One man had terrible dreams and leaped out of his bed and into the snow and took off running and praying (they could see in the snow where he'd knelt). He perished before he could be found. A woman who felt herself lost to hell threw her toddler into a body of water, and when the child climbed out, she threw it back. (In her mind, was she dunking the child like witch finders dunked suspected witches, to see if the water would reject them?) The child was rescued and the mother was hanged. Governor Winthrop connected their acts to not being admitted to church membership.

In a theocratic society, where church and state were one authority, this is the anguish that not only consumes the minds of those who are marginalized, but it creates surveillance and oppression among the people. Everyone judges the others, and watchful eyes report to superiors. People could actually drop in on a home and require the children to recite their catechism from memory.

In our mostly secular society, we might think that people could withdraw from that fundamentalist and judgmental body, and either go to another church or denomination, or stop religious fellowship altogether. But on the personal level, some believe that they must continue with that church or face hellfire. Some are tied there by family, or other expectations like their employment. It's not as easy to pull up stakes and drive two miles to another church as you might think.

In the seventeenth century, it was impossible to change churches. There were no strangers. And though they didn't have networked computers, they all knew each other, for generations, from their former cities and villages in England, and the continued associations in New England. They didn't just move out to the wilderness and start a farm. They were required to live in towns and attend church, and pay tithes and taxes to the church. Probably the best way to "disappear" if you'd been accused or falsely condemned would be to go back to England, but that was very expensive.

Theocracy tolerates no dissent from its established orthodoxy. We can see the theocratic politicians and religious leaders coming out of the woodwork, denying civil rights to LGBT or women, demanding that their rights are more important than the rights of those who don't believe the same way (or believe in God at all), rejecting vetted refugees or assaulting Muslim women wearing the scarf, because they fear Islamic culture or that sharia law will be imposed in America. Please don't allow yourself to be distracted by "morality" issues like abortion, LGBT rights, or women's rights, in this article. I'm attempting to go beyond specific points to the broader issue of who should be in charge of morality policing.

Even the issue of abortion is related to theocracy--religious groups working with legislators to legislate their morality on a pluralistic society and its individual situations, whether it's life or death for a woman and her fetus, or for a same-sex couple to foster or adopt children. It means that one group wants to force every other group, as sincere as their beliefs might be, to follow one narrow path.

And that is the genius in the language of the charter of Rhode Island, the first such document in the world. It was devised and written by Rev. Roger Williams, Dr. John Clarke, the colonial agent (representative) in England, and (because of the wording and the list of Rhode Island founders), probably their first secretary of state and attorney general, William Dyer. When they'd drafted the legal points and the principles they wanted included, they sent the text to John Clarke, who presented it to someone in the royal government, perhaps the secretary of state. When it was written so as to appear to be in the king's voice, it was reviewed by King Charles II and he affixed his seal.

This is part of the religious liberty section in the charter, which acted as a constitution or covenant.

President James Madison wrote a letter in 1822 that said that religion that is free from government interference flourishes. "If a further confirmation of the truth could be wanted, it is to be found in the examples furnished by the States, which have abolished their religious establishments. I cannot speak particularly of any of the cases excepting that of Virginia, where it is impossible to deny that Religion prevails with more zeal, and a more exemplary priesthood than it ever did when established and patronised by Public authority. We are teaching the world the great truth that Govts. do better without Kings & Nobles than with them. The merit will be doubled by the other lesson that Religion flourishes in greater purity, without [rather] than with the aid of Govt.” http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendI_religions66.html

President James Madison wrote a letter in 1822 that said that religion that is free from government interference flourishes. "If a further confirmation of the truth could be wanted, it is to be found in the examples furnished by the States, which have abolished their religious establishments. I cannot speak particularly of any of the cases excepting that of Virginia, where it is impossible to deny that Religion prevails with more zeal, and a more exemplary priesthood than it ever did when established and patronised by Public authority. We are teaching the world the great truth that Govts. do better without Kings & Nobles than with them. The merit will be doubled by the other lesson that Religion flourishes in greater purity, without [rather] than with the aid of Govt.” http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendI_religions66.html

Poor Mrs. Temperance Sweete surely never considered such weighty matters as religious liberty. She was lucky to keep her membership in Boston First Church of Christ, her hope of salvation. But these very issues, "liberty of conscience" and toleration of other belief systems, were what drove Anne Hutchinson, Mary Dyer, Roger Williams, and many others to flee for their lives from theocratic oppression, found the first secular government in America, and send their wisdom down to the founders of the United States.

When we accept prejudice, racial and social bigotry, and discriminating against or excluding people whose beliefs and practices we disapprove of, we've not only gone back to the 1950s or 1930s, but back to the 1600s, when people were imprisoned, whipped to a pulp, tortured, and killed for their beliefs.

When we accept prejudice, racial and social bigotry, and discriminating against or excluding people whose beliefs and practices we disapprove of, we've not only gone back to the 1950s or 1930s, but back to the 1600s, when people were imprisoned, whipped to a pulp, tortured, and killed for their beliefs.

Do we really have to go to that extreme, or can we learn to accept our differences and respect other human beings' rights because it's the right thing to do to be loving, happy, peaceful, patient, kind, good, faithful, gentle, and self-controlled? As the Bible says, "against such is no law."

*****

If you wish to comment on this article, please do so in the comment section below, remembering to be respectful. Do not attack my politics and morals which you have no knowledge of. To save you time, I am conservative and faith-based in my personal behavior, liberal (that means open and generous) in how I treat others and their rights, and in politics I'm independent of party affiliation. In the article, I have given links to primary sources. Kindly do the same for your rebuttals. Comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Do not state your political or religious views in Facebook groups, because your comments will likely be deleted by the group administrators.

If you wish to share the article, please use this shortened URL in your own status or tweet, instead of shares, because sharing from a Facebook group doesn't attach the link for friends who are not in the group: http://bit.ly/2xt3Lra

*****

Mary Dyer Illuminated (Vol. 1)

Mary Dyer Illuminated (Vol. 1)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (Vol. 2)

The DYERS of London, Boston & Newport (Vol. 3)

All are available in paperback and Kindle at

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor Christy K Robinson has written a trilogy (two historical novels based in fact, and a nonfiction book) on Mary and William Dyer. Traditionally, Mary Dyer, who is known for giving her life in the cause of religious liberty, gets all the attention because Quaker historians used her story for political and evangelization purposes. Because he never became a Quaker, William Dyer’s history has been much more difficult to tease out of archives and records in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and the British Library. But this English farmer's son was a foundation stone of American democracy and civil rights.

For those of us raised practicing temperance (no alcohol use), this is ironic.

This slice of life is from the First Church of Boston,

This slice of life is from the First Church of Boston, the Puritan congregation from which Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer

were cast out in 1638. The event happened two years later,

perhaps around the first of March, then her admonishment

was given on the 8th day of March (the first month on their calendar),

1640, and her restoration took place on the fifth of April.

Screen shot: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/62/

Temperance Sweete (one of those Puritan virtue names), a member of the church, was admonished for intemperance. Temperance was the wife of John Sweete, a ship's carpenter.

Her husband must have been at sea when she decided to have a party at home (not the licensed tavern, where women weren't allowed). She served wine and "strong waters" (whisky) and it looks like there was a standard pour amount and price that she exceeded. Venti instead of grande, perhaps. Not to mention, her raucous customers were drunk. Puritans drank all the time, but drunkenness was sinful. Their Geneva Bible said: And be not drunk with wine, wherein is excess: but be fulfilled with the Spirit. Ephesians 5:18.

It sounds as if they were drunk on wine and spirits. (Be sure to lift your eyebrows here, as a proper Church Lady would.)

Temperance's admonishment (probably quite the shaming sermon in front of the congregation at beginning and end of her time) lasted a month. We can almost be sure that the sermon would have made pokes at her name.

Church members submitted to the "laws of Christ" and to oversight of their fellow members. The church as a body desired to be purified from the world and sanctified holy to the Lord. The point of coming under church discipline was not to cast out the wicked, but to remove them from fellowship and possible contamination of other members for a time. They were to examine their behavior, and they could be visited by their ministers and elders. (This is how Anne Hutchinson was treated while under house arrest in the winter of 1637-38, before her excommunication trial.) Then, if they were properly penitent, they could be brought back into full membership privileges, allowed to take Communion, and if they were men, to vote. If they lost their membership, they were still required to attend services and pay tithes to the church and fines to the government, and they couldn't vote.

Rev. John Wilson,

Rev. John Wilson, minister of Boston

First Church of Christ.Being a member of the church was a serious matter. It showed that you might be one of the Elect, the people predestined to salvation who showed their salvation by doing good works. After a short life on earth, they were concerned about the soul's eternity in heaven and not in hell.

Even the ministers were not immune to censure or admonishment. Rev. John Wilson, senior pastor of Boston First Church, had been in England for three-quarters of a year and had recently returned to Boston. Perhaps feeling like he hadn't been missed and Cotton had taken over, he stirred up negativity against the very popular Rev. John Cotton, the teacher of the same church. When Cotton and his faction got their hackles up and demanded censure of Wilson, Cotton graciously turned the situation to one of church unity.

Men dunk a suspected witch in a mill pond.

Men dunk a suspected witch in a mill pond. If she was not a witch,

she'd drown and go to heaven. If she was a witch,

she'd float, rejected by the cleansing water,

and then she'd be hanged and go to hell. Note the

black demons in the water and on shore.