Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 25

July 30, 2011

Celtic Britain travel journal I

Celtic BritainTRAVEL JOURNAL--part 1

Monday, June 18,2001 —3:30 p.m., Los Angeles

Just settled onto the AirNew Zealand 747 for the 11+ hour flight to Heathrow. Far from getting a CelticBritain preview, a video is playing of sub-tropical New Zealand (thatched Maori houses,tree ferns, placid lagoons at sunset. Well, well — there's Uluru, Ayars Rock.They go to Oz, too.)

So we're on a plane fromthe Antipodes, bound for the"Podes?"

9:50 p.m. LA time — We'vepassed over Newfoundland and are closing in onthe southern tip of Greenland. For hours,we've been traveling with the — well, I thought it was sunset — to ourleft. But the sun just rose out of the "sunset." The video map showsthat we've passed Godthab, Greenland.I'm on a center section aisle seat, so all I see is sky, not land or sea. It'sthe time of summer solstice, and I believe we're a few degrees south of the Arctic Circle.

Tuesday, June 19,2001, 3:00a.m. LA time, 11 a.m. Greenwich time, LONDON!!!

We're off the plane, andon a bus/coach at Heathrow, waiting for the entire party to rendezvous. LaSierra zombies, all. I did verify with the coach driver that it's now Tuesdaythe 19th. Gives new meaning to the hymn, "No More Night."

"Ah!" I saidwhen I stepped off the 747 threshold. "I'm returning to the land myancestors left nearly 400 years ago. Breathe deeply of the air!" Far frombeing a Londonpea soup fog, or the bracing salt air of an island, I choked on a lung full ofdiesel and jet fumes.

"Ah!" I saidwhen I stepped off the 747 threshold. "I'm returning to the land myancestors left nearly 400 years ago. Breathe deeply of the air!" Far frombeing a Londonpea soup fog, or the bracing salt air of an island, I choked on a lung full ofdiesel and jet fumes.The coach driver neededMY map to find today's stops. Uh-oh. That's not a good sign. My map is 15 yearsold, but is well marked for all the places I want to see someday. Or on thistrip.

The tree-lined motorway,gently rolling hills, farm buildings, townhouse developments — hmmm… I suspectwe flew around the perimeter of the U.S.,and have been put down in Maryland or Virginia. Just drovepast a brewery delivery truck. Driver could have been Evil Twin of Lance Tyler.Must tell him in next e-mail.

We drove through forestsof pine, hay fields, and green sheep paddocks. (Not for green sheep, thepaddocks are green.) We saw small Quonset huts all over a field, and uponcloser inspection, we found hogs on every doorstep!

All of a sudden, on abroad hill, there was Stonehenge! (I paid£3.50 for admission.) The weather was perfect: breezy, cool, and the cloudswere breaking up. We only had 20 minutes at this place of wonder, so I rushedaround the path. Stonehenge is an awesomemonument, but based on the (probably doctored) photos, it looked a bit squat inperson. Still incredible. I wish we'd had a couple of hours there.

Bus took off for Salisbury immediately. Wesaw many barrows on the hills surrounding Stonehenge,and I was looking for other earthworks. I watched hilltops for evidence ofdigging, which would indicate a hill fort. We drove into the narrow medievalstreets of Salisbury.Still two-way vehicle traffic. We were given 90 minutes to see the cathedralclose and get lunch. I spent 85 minutes there, looking at every effigy andmemorial. (William Longespee/Longsword's effigy adorns the center aisle of the nave.) The carved stone everywhere was amazing, and I appreciate it so muchmore for having read Edward Rutherford's Sarum. I stopped in the TrinityChapel (top of the chancel) and prayed for a few minutes. Many of my Angevinand Plantagenet royal ancestors did the same, I'm sure, though with varieddegrees of devotion.

Then we went to OldSarum, which is an immense hill fort. The ditch and steep bank were dug out andbuilt up by people living here a thousand years before Abraham. What was thisgeneration of monument builders, who built the pyramids of the Middle East and Central America, who dug ramparts of earth, moved sarsenstones scores and hundreds of miles — all with stone, wood, and boneimplements?

This sense of historywith every footstep and every glance at the countryside, just makes me feel sotiny and humble. No griping about jet lag or burning feet. (Yet.) These peoplecouldn't take an ibuprofen after placing a lintel over a Stonehenge pillar, orsit in a jacuzzi after digging and building (with hands) a hill which wouldtake most of a year for earthmovers and engineers to get accomplished. How didthe Old Ones know to carve a knob on top of the pillar, to securely notch thelintel to the gateway? Who were these visionaries and engineers and slave driversthe ones buried in the barrows? No, I suspect the barrow tombs were only for royalty or priests.

This sense of historywith every footstep and every glance at the countryside, just makes me feel sotiny and humble. No griping about jet lag or burning feet. (Yet.) These peoplecouldn't take an ibuprofen after placing a lintel over a Stonehenge pillar, orsit in a jacuzzi after digging and building (with hands) a hill which wouldtake most of a year for earthmovers and engineers to get accomplished. How didthe Old Ones know to carve a knob on top of the pillar, to securely notch thelintel to the gateway? Who were these visionaries and engineers and slave driversthe ones buried in the barrows? No, I suspect the barrow tombs were only for royalty or priests.It was at least atwo-hour bus ride from Devon north to Avon, but at last (though I could nothelp dozing for five minutes at a time after 40 hours with no sleep), I saw apass in the rolling downs, which would be the south bank of the Severn Valley.We crossed a very long and modern toll bridge, over a muddy "river"that was really a sound or bay, and arrived in Cymru, the Land of the People.My people! My Celtic ancestors moved here when Jerusalem was rebuilt after its Babyloniancaptivity. Our hotel is the NewportHilton. We had a group supper, where Dr. John Jones, one of our two directors,dryly said that after the meal, we should check out the south Wales night clubs. I'm sureeveryone did the same as I: showered for the first time in 40 hours, and sleptfor the first time in about 44-48 hours. (Don't count the nodding on the bus: Iwas forcing myself to stay at least semi-conscious so as not to miss a thing.Many of the tour mates gave up the fight, however!)

I slept for 6 hours andam now awake at 4 a.m. I'm sleepy enough to get another couple hours in beforebreakfast, though.

Wednesday, June 20,2001, 3p.m., Newport,Wales

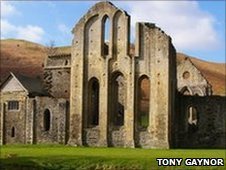

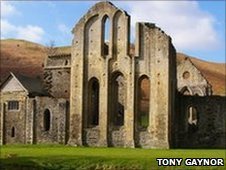

We started the morningwith a buffet breakfast. Then we bused to Glastonburyto see the abbey and cathedral ruins. The weather was perfect: 70, breezy,sunny. I prayed at the grassy place where the high altar would have been, nearthe end of the nave, before the chancel. I stood in the same place as my royalancestors had done.

We started the morningwith a buffet breakfast. Then we bused to Glastonburyto see the abbey and cathedral ruins. The weather was perfect: 70, breezy,sunny. I prayed at the grassy place where the high altar would have been, nearthe end of the nave, before the chancel. I stood in the same place as my royalancestors had done.As we drove out of Glastonbury, we could seethe Tor and its tower on a nearby hill. Some of our group climbed it while therest visited the Abbey. A few miles later, I noticed a hill-fort. They havebanks or terraces to give them an irregular profile. I've noticed 5 or 6 ofthem so far.

I keep noticing square Norman towers every fewmiles. Sometimes there's a church, but not always, if the church burned or felldown. The towers seem to last, though.

Longleat House: this isthe 16th century manor house of the Marquess of Bath. Grounds byCapability Brown: very natural meadows and lake. But Capability would freak atthe asphalt car and bus park, and the safari rides, gift shop, and ice creamshops. On the house tour, we saw huge paintings and beautiful furniture,although the gigantic windows were all shaded or shuttered so as not to fade ordamage the art treasures. The docents let me take a lift upstairs when they sawmy cane, and kept asking if I was all right. I was halfway down the grandstaircase on my way out, when I heart a docent ask if anyone wanted to play thegrand piano. Suddenly, stairs held no terror for me, and I shot up the steps,offering, "I'll play." I did an improv of "The Water isWide." (Yes, same as I sang in the glow-worm cave at Waitomo, New Zealand.)The ice cream shop had banana and Rolo flavors, so I had an exotic cone forlunch. Penny Shell and I sat on a shaded bench and ate our cones while I rubbedmy sore foot. Then we were off to Bath.

Longleat House: this isthe 16th century manor house of the Marquess of Bath. Grounds byCapability Brown: very natural meadows and lake. But Capability would freak atthe asphalt car and bus park, and the safari rides, gift shop, and ice creamshops. On the house tour, we saw huge paintings and beautiful furniture,although the gigantic windows were all shaded or shuttered so as not to fade ordamage the art treasures. The docents let me take a lift upstairs when they sawmy cane, and kept asking if I was all right. I was halfway down the grandstaircase on my way out, when I heart a docent ask if anyone wanted to play thegrand piano. Suddenly, stairs held no terror for me, and I shot up the steps,offering, "I'll play." I did an improv of "The Water isWide." (Yes, same as I sang in the glow-worm cave at Waitomo, New Zealand.)The ice cream shop had banana and Rolo flavors, so I had an exotic cone forlunch. Penny Shell and I sat on a shaded bench and ate our cones while I rubbedmy sore foot. Then we were off to Bath.I've wanted to see Bath since I first heardof it as a child. Roman mosaics. Magical hot springs. We were let out of our coach by the Avon River,and while others decided what to see first, or who would group with others, Iwas out the door, down the street, and paying for a guided city tour! I was theonly one on the double-deck bus, so the tour guide just told it all to me. Bath has narrow, curvingstreets lined with Edwardian-era tan limestone tenements. I don't mean thatthey were a slum. Just every one alike. Thousands, all alike! I went first tothe abbey church, and read a few memorial carvings in the floor. The carvingsall face east, same as Salisbury,so I believe it's so that at the Resurrection, the bodies will all come upfacing Jesus? The organist was practicing, and it still sounded great.

Found the Adventistchurch, literally in the shadow of the abbey church. About as small as agarage. Left my LSU business card in the letter slot, for the pastor to find atprayer meeting that evening.

Then I went to the RomanBath and museum. It was very interesting and lived up to all but one dream: tosoak my aching feet or dangle them in a hot spring pool. The archaeologicalsociety could have a spa concession, like 50p or £1 to let you unshoe, and rollup your pants legs, and dunk! Walking up and down stairs, and across stoneblocks, and concrete — aieeeee, my feet.

Searched desperately fora sandwich shop for supper, since I'd only had the cone for lunch. They roll upthe sidewalks at 6, though, and it was 6:15 when I was needing sustenance and atall drink. Finally found a tuna salad to go, after hobbling back and forth onthe cobblestones, and then I made it back to the coach for the 90-minute tripback to the hotel.

It's 9:35 p.m. here in Wales,and the sun is just now setting and it's getting chilly out here in the hotelcourtyard. There's a fountain splashing, and the birds are singing. Maybe I'llgo in and soak my feet in a hot bath: the porcelain tub and tap water. Tomorrowis New Moon and summer solstice, here in neo-druid headquarters. There'ssupposed to be a world-wide voluntary "rolling blackout" to make people awareof and encourage participation in energy conservation. Jay Leno will do hisshow in candlelight tomorrow night.

Thursday, June 21,2001, 7p.m., Cornwall

We're rolling across themoors of Devon and Cornwall.The sun is still high in the western sky, with two and a half hours ofbenevolent smiles left in this longest day of the year. Back in my hometown of Phoenix, there's no reasonto celebrate the long, blasting hot day, when the earth is closest to the sun andtilted toward Old Sol at the same time. And who thought up Midsummer's Eve,when there are still three-plus months of hellish heat to go? Dang! But here inBritain,I can at last understand reveling in the perfect day. There are sheep andcattle on every hillside, either grazing, ruminating, or shamelessly stretchedout for a snooze. Clear sky, green grass, fields of red poppies, the occasionalpuffy cloud…. Very nice.

We left Newport,Wales,and took small, narrow lanes to get to Cerne Abbas in Dorsetshire to see theChalk Giant. (I think our driver would have got there 45-60 minutes earlier ifhe knew where he's going, and drove faster. We are the slowest vehicle on theroad.) The Giant is a warrior with a 120-foot-long war club, and (let's not gothere for the length!) an erect penis, cavorting on a hillside in Dorset. He could be Celtic and Iron Age, orHercules/Helios ca 275 AD, or an 18th century invention.

We left Newport,Wales,and took small, narrow lanes to get to Cerne Abbas in Dorsetshire to see theChalk Giant. (I think our driver would have got there 45-60 minutes earlier ifhe knew where he's going, and drove faster. We are the slowest vehicle on theroad.) The Giant is a warrior with a 120-foot-long war club, and (let's not gothere for the length!) an erect penis, cavorting on a hillside in Dorset. He could be Celtic and Iron Age, orHercules/Helios ca 275 AD, or an 18th century invention. We poked our way throughthe rural valleys and across moors. Dorset and Devon were part of the kingdom of Wessex, where Alfred the Great (myancestor) ruled. I read aloud parts of a chapter on Alfred and his Welsh(Celtic) teacher. After more sheep, more cattle, a drive through the southerntown of Bridgport,we headed northwest past (oh, yes) more sheep, cattle, and moors. Not onesingle part was ugly or blighted—it was all beautiful. I suggested we stop fora cream tea, since this place has a world-famous reputation for clotted cream,so we started looking for a tea room. We stopped at Camelford Bridge,the site of King Arthur's last battle, where he was killed by Mordred. Wewalked 300 yards (seemed a lot farther, though) down a gravel path to thefamous bridge, and then had Cornish cream tea at the little tea room. Two smallscones, clotted cream, jam, and a pot of tea. Very nice.

About 7 miles more, andwe were in Tintagel, a clifftop village. The castle there, actually built byReginald, illegitimate son of Henry I, is supposedly Arthur's birthplace,although why anyone would be born on a cliff 600 years before the castle wasbuilt, is beyond me! The existing ruins are on a wild crag of coastline. I paida pound to ride a Land Rover down to the base of the castle stairs, but therewas no way I was traipsing up or down hundreds of steps. I stayed by the littlestream/waterfall above the cove, with its booming surf, and took some picturesof Kit and Penny and various seabirds. Just before our time was up, I bought abeef pasty, a world-famous Cornish specialty. I even influenced several othersto try pasties. We boarded the bus for the three-hour trip back to Newport. We pasty-eaterssampled the huge pies after 9:30, and everyone really liked them.

About 7 miles more, andwe were in Tintagel, a clifftop village. The castle there, actually built byReginald, illegitimate son of Henry I, is supposedly Arthur's birthplace,although why anyone would be born on a cliff 600 years before the castle wasbuilt, is beyond me! The existing ruins are on a wild crag of coastline. I paida pound to ride a Land Rover down to the base of the castle stairs, but therewas no way I was traipsing up or down hundreds of steps. I stayed by the littlestream/waterfall above the cove, with its booming surf, and took some picturesof Kit and Penny and various seabirds. Just before our time was up, I bought abeef pasty, a world-famous Cornish specialty. I even influenced several othersto try pasties. We boarded the bus for the three-hour trip back to Newport. We pasty-eaterssampled the huge pies after 9:30, and everyone really liked them.See Celtic Britain Travel Journal Part 2 in this blog. (Coming up: Ireland)

Published on July 30, 2011 11:49

July 12, 2011

Celtic Britain--my first tour of the UK

I wrote this article in July 2001, upon my return from a university tour of England, Wales, Ireland, Northern Ireland, and Scotland. This was the first of four (so far) extended trips to the UK. A joint effort of the English and religion departments, the tour members prepared research papers beforehand, and presented them to the "class" during extended coach trips. This article was published in La Sierra Today magazine in December 2001. There was also a travel journal, which I'll publish to this blog separately.

The Celtic cross, with its circle behind the cross beams, symbolizes the eternity of God.

The Celtic cross, with its circle behind the cross beams, symbolizes the eternity of God.

May those who love us, love us,And those who don't love us,May God turn their hearts;And if He doesn't turn their heartsMay he turn their anklesSo we'll know them by their limping.(old Celtic blessing)

I admit, I limped. A lot. But I have a note from my doctor, so don't tattle to my pastor. (Besides, she's seen me with my walking stick.) There were times I felt like roadkill, after a long day of pounding the cobblestones or dragging up six flights of un-air-conditioned stairs to get to the Celtic Britain display in the British Museum. The castles or cathedrals we visited were always at the hill's crown (for defensive purposes), often surrounded by an ancient stone wall (and we had to leave the bus at the bottom of the mount). But no one did it to me: it was my choice. And my clothes are much looser after all that exercise, so who's complaining?

The trip was a class for some, and business for several others. So I probably shouldn't mention that it was fun. The IRS or the academic vice president might take exception to our claims.

The Celtic Britain tour group visited a church in Dublin, Ireland.

The Celtic Britain tour group visited a church in Dublin, Ireland.

The Celtic Britain 2001 tour, June 18 to July 3, was offered for academic credit in both religion and English departments. Students researched and wrote papers before the trip, and presented them from the jump seat at the front of the coach. Non-academic tour members were educated right along with the students. There were twenty-two tour members, including directors Dorothy Minchin Comm, PhD, professor of English, and John Jones, PhD, professor and dean of the School of Religion.

We were an eclectic bunch: retired medical missionaries, university grad students, the two directors of the LSU Women's Resource Center, elementary school teachers, nurses, an actor, musicians, history buffs. Seasoned travelers and first-timers. One had hardly been out of her small town, and was terrified of her first trip on a ferry across the Irish Sea. Soon she was savoring the sea air, something like Funny Girl singing, "Don't rain on my parade," thanks to the helpful and encouraging attitude of her new friends. Some of us stayed grouped together in twos or threes, others ran out the door alone.

Kit Watts and Penny Shell enjoyed the summer solstice at Tintagel, Cornwall.We visited places we'd read about all our lives, from books or magazines on history, art, culture, and religion. Stonehenge was our first stop, and the thirteenth-century Salisbury Cathedral was our second. The architecture of cathedrals, castles, and Neolithic hillforts were equally stunning. We went to sites as diverse as southeastern England, Cornwall, Wales, Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and back into central England. In Wales, we found a stone circle in a traffic roundabout.

Kit Watts and Penny Shell enjoyed the summer solstice at Tintagel, Cornwall.We visited places we'd read about all our lives, from books or magazines on history, art, culture, and religion. Stonehenge was our first stop, and the thirteenth-century Salisbury Cathedral was our second. The architecture of cathedrals, castles, and Neolithic hillforts were equally stunning. We went to sites as diverse as southeastern England, Cornwall, Wales, Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and back into central England. In Wales, we found a stone circle in a traffic roundabout.

Our mission was to walk in the footsteps of the Celtic saints, David of Wales, Bridget, Patrick, Ciaran, Columcille/Columba, Brendan the Navigator, Cuthbert, and many others. Those footsteps included the monasteries at Clonfert and Clonmacnoise, Glastonbury, Iona and Lindisfarne, Downpatrick, and Glendalough, as well as the tiny 1600 year-old drymasonry oratory of Gallarus. The saints, of course, have many miraculous and (frankly too-fabulous) legendary feats attributed to them. In fact, they were pioneer missionaries to the pagan Celtic and Saxon settlers in the British Isles. They fearlessly risked their lives to preach the Gospel to some very wild, sometimes savage pagans!

1600-year-old Gallarus Oratory, Dingle, Ireland.We saw the original Book of Kells (illuminated Gospels) in Dublin, and a Magna Carta in Salisbury. We walked through stone cells where the Gospels were laboriously copied and illuminated with fanciful animals and Celtic Christian symbols. What would be the quality of our work, if we thought that it would be scrutinized and appreciated 1200 years from now? La Sierra Today in a climate-controlled Plexiglass box, with hundreds of pilgrims lined up daily to pay their £4 admission ticket? I wish!

1600-year-old Gallarus Oratory, Dingle, Ireland.We saw the original Book of Kells (illuminated Gospels) in Dublin, and a Magna Carta in Salisbury. We walked through stone cells where the Gospels were laboriously copied and illuminated with fanciful animals and Celtic Christian symbols. What would be the quality of our work, if we thought that it would be scrutinized and appreciated 1200 years from now? La Sierra Today in a climate-controlled Plexiglass box, with hundreds of pilgrims lined up daily to pay their £4 admission ticket? I wish!

We found the tiny Adventist church, literally in the shadow of the large Bath Abbey. We worshiped with fellow believers in churches in Dublin and Edinburgh. Members of the tour took parts of the services there, giving prayer or special music, and even the sermon. We had devotions on the coach, rolling across the green, sheep-dotted moors of Cornwall, past the Norman keeps and church towers of Wales, and the medieval city walls of Ireland. I committed myself to silently praying before the altar of every church or cathedral or abbey that we visited.

"Wear British Wool: 40 Million Sheep Can't Be Wrong," said a bumper sticker. Island of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland.

"Wear British Wool: 40 Million Sheep Can't Be Wrong," said a bumper sticker. Island of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland.

Chi-Ro carpet page from Book of KellsThose were the high points of my experience, really. It's hard to choose which place was more beautiful or perfect than the last. The 1500 year-old Clonfert cathedral was tiny and dark, with birds flying in the rafters above, and electric space heaters stored in the vestry. Glastonbury was immense, but roofed in blue sky and carpeted in grass. My ancestors prayed and took Communion 840 years ago, in that place, when it stood in all its glory. St. Margaret's Chapel, a tiny barrel-vaulted chapel on the rock at Edinburgh Castle, was dedicated to Queen Margaret by her son and my ancestor, David I of Scotland. Two generations of my Neville ancestors were interred at Durham Cathedral, the largest medieval building in Britain. I took Communion at Westminster Abbey, where other ancestors were crowned or buried; and at St. Paul's, a monument to God's glory. Holy places, all, for more than a millennium. Hard to fathom, when you're native to the American Southwest, really only habitable since the advent of air conditioning.

Chi-Ro carpet page from Book of KellsThose were the high points of my experience, really. It's hard to choose which place was more beautiful or perfect than the last. The 1500 year-old Clonfert cathedral was tiny and dark, with birds flying in the rafters above, and electric space heaters stored in the vestry. Glastonbury was immense, but roofed in blue sky and carpeted in grass. My ancestors prayed and took Communion 840 years ago, in that place, when it stood in all its glory. St. Margaret's Chapel, a tiny barrel-vaulted chapel on the rock at Edinburgh Castle, was dedicated to Queen Margaret by her son and my ancestor, David I of Scotland. Two generations of my Neville ancestors were interred at Durham Cathedral, the largest medieval building in Britain. I took Communion at Westminster Abbey, where other ancestors were crowned or buried; and at St. Paul's, a monument to God's glory. Holy places, all, for more than a millennium. Hard to fathom, when you're native to the American Southwest, really only habitable since the advent of air conditioning.

But my favorite place was the tiny, tidal island of Lindisfarne, off the North Yorkshire coast. The coach drove across the causeway scant minutes before the tide stranded us on the island for more than three hours. The rest of the group were scattered around the castle, town, and museum, and I was alone in the priory church. Again, it was green grass below and blue sky above. The afternoon sun shone through glassless windows, as I sat to rest on a low stone wall at the center of the chancel, and thanked God for bringing me to this sacred place. In my spirit, I heard, "Present yourself as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God. This is your spiritual act of worship." I knew it was God speaking, but why here, and why that text from Romans? I realized I was sitting at the very place where the stone altar had been placed in 600 AD. How many opportunities does one have in a lifetime, to be sacrificed on a stone altar? Thanks be to God, we are living sacrifices!

The trip was a religious experience for all of us, at some points. Who could not be impressed by the dedication of the pioneer missionaries and saints? Who could not hear God in the organ of a colossal cathedral or the peace of an ancient churchyard on Iona? Who could fail to see His handiwork in a brilliant rainbow shining over a Scottish loch? Who could miss the symbolism of a white dove perched on the stone arch of a ruined abbey?

But one could not ignore the anticipatory shiver as the bagpipers marched through the gates at Edinburgh Castle, the thrill of the chill wind and stray rain drops in your hair as you coasted on a rented bike down a hillside, or the growling stomach when it was overdue for that Cornish pasty you promised it three hours ago. Answering your email from an Internet café in Cork, Ireland, has a certain boast built in ("I'm in Ireland, and you're not"), even if you try to sound humble!

You could find your own joys and shivers and introspective moments, even plenty of Kodak moments, on other trips offered by La Sierra University. This year [2001], the University sponsored trips to South America, South Africa, the Mediterranean, the Holy Land. Modern Languages sent students to Paris and Central America. In 2002, LSU President Lawrence T. Geraty, director of the Madaba Plains Project, will lead an archaeological dig in Jordan. (I'm planning on that one!) And there will be others, as well. How about China and Asia? You'll learn as much from your own and fellow students' experiences as you do from the professors who are expert in their fields.

Glendalough, Republic of IrelandThe trips are not cheap, but neither are the memories. My scrapbook weighs 20 pounds! And if you start saving and sacrificing now for next year, you could do it. Sure, on the trip you'll have to wear the same few outfits over and over, drench them with Febreze fabric deodorizer, and wash them in the hotel bathtub. You'll try new and sometimes bizarre dishes in restaurants. You'll be crammed into a jet plane, and wish vainly that your bus could stop and let you have a still picture for once, instead of madly dashing to meet the ferry. You could ride a real bike, not the stationary kind. Your bags will be sniffed by dogs and maybe even some stern-looking security agents. You will put significant mileage on those athletic shoes, so put gel inserts in them. Take your ATM card to draw foreign currency there. Be sure to take your walking stick, no matter where you go or how fit you are. After I walked two miles to arrive at all those stairs at Clifford's Tower in York, my knees were jelly, and I still had miles to go that day!

Glendalough, Republic of IrelandThe trips are not cheap, but neither are the memories. My scrapbook weighs 20 pounds! And if you start saving and sacrificing now for next year, you could do it. Sure, on the trip you'll have to wear the same few outfits over and over, drench them with Febreze fabric deodorizer, and wash them in the hotel bathtub. You'll try new and sometimes bizarre dishes in restaurants. You'll be crammed into a jet plane, and wish vainly that your bus could stop and let you have a still picture for once, instead of madly dashing to meet the ferry. You could ride a real bike, not the stationary kind. Your bags will be sniffed by dogs and maybe even some stern-looking security agents. You will put significant mileage on those athletic shoes, so put gel inserts in them. Take your ATM card to draw foreign currency there. Be sure to take your walking stick, no matter where you go or how fit you are. After I walked two miles to arrive at all those stairs at Clifford's Tower in York, my knees were jelly, and I still had miles to go that day!

I'm afraid those modern Britons knew me by my limping, but it wasn't my unloving attitude. (It was my 1982 accident.) This was a journey I've wanted to make since I was a teenager, and that was several dog-years ago. I can hardly wait for Jordan in July 2002. Maybe Israel or St. Paul's journeys the year after. There are still blank pages in my passport, and I can buy new tips for my walking stick!

The Celtic cross, with its circle behind the cross beams, symbolizes the eternity of God.

The Celtic cross, with its circle behind the cross beams, symbolizes the eternity of God.May those who love us, love us,And those who don't love us,May God turn their hearts;And if He doesn't turn their heartsMay he turn their anklesSo we'll know them by their limping.(old Celtic blessing)

I admit, I limped. A lot. But I have a note from my doctor, so don't tattle to my pastor. (Besides, she's seen me with my walking stick.) There were times I felt like roadkill, after a long day of pounding the cobblestones or dragging up six flights of un-air-conditioned stairs to get to the Celtic Britain display in the British Museum. The castles or cathedrals we visited were always at the hill's crown (for defensive purposes), often surrounded by an ancient stone wall (and we had to leave the bus at the bottom of the mount). But no one did it to me: it was my choice. And my clothes are much looser after all that exercise, so who's complaining?

The trip was a class for some, and business for several others. So I probably shouldn't mention that it was fun. The IRS or the academic vice president might take exception to our claims.

The Celtic Britain tour group visited a church in Dublin, Ireland.

The Celtic Britain tour group visited a church in Dublin, Ireland.The Celtic Britain 2001 tour, June 18 to July 3, was offered for academic credit in both religion and English departments. Students researched and wrote papers before the trip, and presented them from the jump seat at the front of the coach. Non-academic tour members were educated right along with the students. There were twenty-two tour members, including directors Dorothy Minchin Comm, PhD, professor of English, and John Jones, PhD, professor and dean of the School of Religion.

We were an eclectic bunch: retired medical missionaries, university grad students, the two directors of the LSU Women's Resource Center, elementary school teachers, nurses, an actor, musicians, history buffs. Seasoned travelers and first-timers. One had hardly been out of her small town, and was terrified of her first trip on a ferry across the Irish Sea. Soon she was savoring the sea air, something like Funny Girl singing, "Don't rain on my parade," thanks to the helpful and encouraging attitude of her new friends. Some of us stayed grouped together in twos or threes, others ran out the door alone.

Kit Watts and Penny Shell enjoyed the summer solstice at Tintagel, Cornwall.We visited places we'd read about all our lives, from books or magazines on history, art, culture, and religion. Stonehenge was our first stop, and the thirteenth-century Salisbury Cathedral was our second. The architecture of cathedrals, castles, and Neolithic hillforts were equally stunning. We went to sites as diverse as southeastern England, Cornwall, Wales, Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and back into central England. In Wales, we found a stone circle in a traffic roundabout.

Kit Watts and Penny Shell enjoyed the summer solstice at Tintagel, Cornwall.We visited places we'd read about all our lives, from books or magazines on history, art, culture, and religion. Stonehenge was our first stop, and the thirteenth-century Salisbury Cathedral was our second. The architecture of cathedrals, castles, and Neolithic hillforts were equally stunning. We went to sites as diverse as southeastern England, Cornwall, Wales, Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and back into central England. In Wales, we found a stone circle in a traffic roundabout.Our mission was to walk in the footsteps of the Celtic saints, David of Wales, Bridget, Patrick, Ciaran, Columcille/Columba, Brendan the Navigator, Cuthbert, and many others. Those footsteps included the monasteries at Clonfert and Clonmacnoise, Glastonbury, Iona and Lindisfarne, Downpatrick, and Glendalough, as well as the tiny 1600 year-old drymasonry oratory of Gallarus. The saints, of course, have many miraculous and (frankly too-fabulous) legendary feats attributed to them. In fact, they were pioneer missionaries to the pagan Celtic and Saxon settlers in the British Isles. They fearlessly risked their lives to preach the Gospel to some very wild, sometimes savage pagans!

1600-year-old Gallarus Oratory, Dingle, Ireland.We saw the original Book of Kells (illuminated Gospels) in Dublin, and a Magna Carta in Salisbury. We walked through stone cells where the Gospels were laboriously copied and illuminated with fanciful animals and Celtic Christian symbols. What would be the quality of our work, if we thought that it would be scrutinized and appreciated 1200 years from now? La Sierra Today in a climate-controlled Plexiglass box, with hundreds of pilgrims lined up daily to pay their £4 admission ticket? I wish!

1600-year-old Gallarus Oratory, Dingle, Ireland.We saw the original Book of Kells (illuminated Gospels) in Dublin, and a Magna Carta in Salisbury. We walked through stone cells where the Gospels were laboriously copied and illuminated with fanciful animals and Celtic Christian symbols. What would be the quality of our work, if we thought that it would be scrutinized and appreciated 1200 years from now? La Sierra Today in a climate-controlled Plexiglass box, with hundreds of pilgrims lined up daily to pay their £4 admission ticket? I wish!We found the tiny Adventist church, literally in the shadow of the large Bath Abbey. We worshiped with fellow believers in churches in Dublin and Edinburgh. Members of the tour took parts of the services there, giving prayer or special music, and even the sermon. We had devotions on the coach, rolling across the green, sheep-dotted moors of Cornwall, past the Norman keeps and church towers of Wales, and the medieval city walls of Ireland. I committed myself to silently praying before the altar of every church or cathedral or abbey that we visited.

"Wear British Wool: 40 Million Sheep Can't Be Wrong," said a bumper sticker. Island of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland.

"Wear British Wool: 40 Million Sheep Can't Be Wrong," said a bumper sticker. Island of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland.

Chi-Ro carpet page from Book of KellsThose were the high points of my experience, really. It's hard to choose which place was more beautiful or perfect than the last. The 1500 year-old Clonfert cathedral was tiny and dark, with birds flying in the rafters above, and electric space heaters stored in the vestry. Glastonbury was immense, but roofed in blue sky and carpeted in grass. My ancestors prayed and took Communion 840 years ago, in that place, when it stood in all its glory. St. Margaret's Chapel, a tiny barrel-vaulted chapel on the rock at Edinburgh Castle, was dedicated to Queen Margaret by her son and my ancestor, David I of Scotland. Two generations of my Neville ancestors were interred at Durham Cathedral, the largest medieval building in Britain. I took Communion at Westminster Abbey, where other ancestors were crowned or buried; and at St. Paul's, a monument to God's glory. Holy places, all, for more than a millennium. Hard to fathom, when you're native to the American Southwest, really only habitable since the advent of air conditioning.

Chi-Ro carpet page from Book of KellsThose were the high points of my experience, really. It's hard to choose which place was more beautiful or perfect than the last. The 1500 year-old Clonfert cathedral was tiny and dark, with birds flying in the rafters above, and electric space heaters stored in the vestry. Glastonbury was immense, but roofed in blue sky and carpeted in grass. My ancestors prayed and took Communion 840 years ago, in that place, when it stood in all its glory. St. Margaret's Chapel, a tiny barrel-vaulted chapel on the rock at Edinburgh Castle, was dedicated to Queen Margaret by her son and my ancestor, David I of Scotland. Two generations of my Neville ancestors were interred at Durham Cathedral, the largest medieval building in Britain. I took Communion at Westminster Abbey, where other ancestors were crowned or buried; and at St. Paul's, a monument to God's glory. Holy places, all, for more than a millennium. Hard to fathom, when you're native to the American Southwest, really only habitable since the advent of air conditioning. But my favorite place was the tiny, tidal island of Lindisfarne, off the North Yorkshire coast. The coach drove across the causeway scant minutes before the tide stranded us on the island for more than three hours. The rest of the group were scattered around the castle, town, and museum, and I was alone in the priory church. Again, it was green grass below and blue sky above. The afternoon sun shone through glassless windows, as I sat to rest on a low stone wall at the center of the chancel, and thanked God for bringing me to this sacred place. In my spirit, I heard, "Present yourself as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God. This is your spiritual act of worship." I knew it was God speaking, but why here, and why that text from Romans? I realized I was sitting at the very place where the stone altar had been placed in 600 AD. How many opportunities does one have in a lifetime, to be sacrificed on a stone altar? Thanks be to God, we are living sacrifices!

The trip was a religious experience for all of us, at some points. Who could not be impressed by the dedication of the pioneer missionaries and saints? Who could not hear God in the organ of a colossal cathedral or the peace of an ancient churchyard on Iona? Who could fail to see His handiwork in a brilliant rainbow shining over a Scottish loch? Who could miss the symbolism of a white dove perched on the stone arch of a ruined abbey?

But one could not ignore the anticipatory shiver as the bagpipers marched through the gates at Edinburgh Castle, the thrill of the chill wind and stray rain drops in your hair as you coasted on a rented bike down a hillside, or the growling stomach when it was overdue for that Cornish pasty you promised it three hours ago. Answering your email from an Internet café in Cork, Ireland, has a certain boast built in ("I'm in Ireland, and you're not"), even if you try to sound humble!

You could find your own joys and shivers and introspective moments, even plenty of Kodak moments, on other trips offered by La Sierra University. This year [2001], the University sponsored trips to South America, South Africa, the Mediterranean, the Holy Land. Modern Languages sent students to Paris and Central America. In 2002, LSU President Lawrence T. Geraty, director of the Madaba Plains Project, will lead an archaeological dig in Jordan. (I'm planning on that one!) And there will be others, as well. How about China and Asia? You'll learn as much from your own and fellow students' experiences as you do from the professors who are expert in their fields.

Glendalough, Republic of IrelandThe trips are not cheap, but neither are the memories. My scrapbook weighs 20 pounds! And if you start saving and sacrificing now for next year, you could do it. Sure, on the trip you'll have to wear the same few outfits over and over, drench them with Febreze fabric deodorizer, and wash them in the hotel bathtub. You'll try new and sometimes bizarre dishes in restaurants. You'll be crammed into a jet plane, and wish vainly that your bus could stop and let you have a still picture for once, instead of madly dashing to meet the ferry. You could ride a real bike, not the stationary kind. Your bags will be sniffed by dogs and maybe even some stern-looking security agents. You will put significant mileage on those athletic shoes, so put gel inserts in them. Take your ATM card to draw foreign currency there. Be sure to take your walking stick, no matter where you go or how fit you are. After I walked two miles to arrive at all those stairs at Clifford's Tower in York, my knees were jelly, and I still had miles to go that day!

Glendalough, Republic of IrelandThe trips are not cheap, but neither are the memories. My scrapbook weighs 20 pounds! And if you start saving and sacrificing now for next year, you could do it. Sure, on the trip you'll have to wear the same few outfits over and over, drench them with Febreze fabric deodorizer, and wash them in the hotel bathtub. You'll try new and sometimes bizarre dishes in restaurants. You'll be crammed into a jet plane, and wish vainly that your bus could stop and let you have a still picture for once, instead of madly dashing to meet the ferry. You could ride a real bike, not the stationary kind. Your bags will be sniffed by dogs and maybe even some stern-looking security agents. You will put significant mileage on those athletic shoes, so put gel inserts in them. Take your ATM card to draw foreign currency there. Be sure to take your walking stick, no matter where you go or how fit you are. After I walked two miles to arrive at all those stairs at Clifford's Tower in York, my knees were jelly, and I still had miles to go that day!I'm afraid those modern Britons knew me by my limping, but it wasn't my unloving attitude. (It was my 1982 accident.) This was a journey I've wanted to make since I was a teenager, and that was several dog-years ago. I can hardly wait for Jordan in July 2002. Maybe Israel or St. Paul's journeys the year after. There are still blank pages in my passport, and I can buy new tips for my walking stick!

Published on July 12, 2011 16:14

July 5, 2011

Pirates in your face! Helen Hollick guest post

Helen Hollick, author I am honored to present to my readers a guest article by historical fiction author Helen Hollick. She's a prolific writer in the history/historical fiction genre I enjoy most, and I've come to enjoy her acquaintance with Facebook and email exchanges. I have her Harold the King/I Am the Chosen King book on Kindle for PC and am fascinated by her portrayal of that ancestor.

Helen Hollick, author I am honored to present to my readers a guest article by historical fiction author Helen Hollick. She's a prolific writer in the history/historical fiction genre I enjoy most, and I've come to enjoy her acquaintance with Facebook and email exchanges. I have her Harold the King/I Am the Chosen King book on Kindle for PC and am fascinated by her portrayal of that ancestor. Hollick's Sea Witch Voyages series of books is being republished by SilverWood Books, and I was excited to discover another tie to my (and your, if you found Spotswood in a search) ancestors. She's written pirate novels that features our pirate-stalking ancestor, Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia, as one of her characters. I'll let Helen explain from here. See my further note at the end of her article and discover an opportunity to win a book from Helen.

Bring It Close: pirates in your face!by Helen Hollick

Hello. I'm probably more well known in the US for my serious historical fiction novels – The Pendragon's Banner Trilogy, Forever Queen, and I am the Chosen King (titled A Hollow Crown and Harold the King here in the UK). Indeed I was most thrilled a few weeks ago to discover that Forever Queen had made it into the USA Today Bestseller list.

I also write a series of historical adventure fantasy – the Sea Witch Voyages. I describe these as a typical sailor's yarn, a blend of Sharpe, Hornblower, James Bond and Indiana Jones – with a dash of Jack Sparrow!

They are meant as light-hearted entertainment (fun for me to write and for readers to enjoy). I suppose they are more supernatural than fantasy, for although the female lead, Tiola Oldstaff (pronounced Te-ola Oldstaff) is a white witch, I think of her Craft more as the Force in Star Wars, not Harry Potter wizardry. My main character, Captain Jesamiah Acorne, is a charmer of a rogue. Handsome, brave, bold, quick to laugh, formidable when angry; one for the ladies – a pirate! In the first three Voyages – Sea Witch, Pirate Code and Bring It Close, he finds himself in all sorts of scrapes, from almost being killed by his jealous half brother, to spying on the Spanish and having a desperate run-in with Edward Teach – Blackbeard himself. Trouble follows Jesamiah like a ship's wake! I'm writing a fourth in the series, Ripples in the Sand.

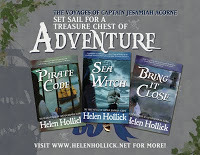

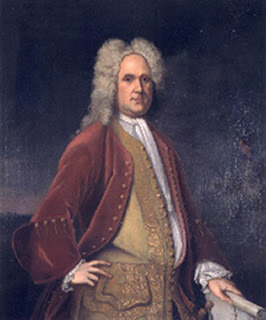

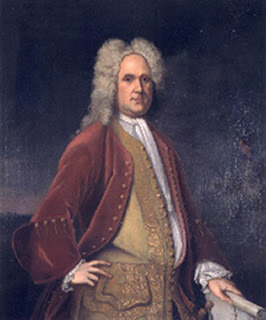

Lt Col Alexander SpotswoodIt was very interesting hearing from Christy – and being invited onto this Blog - because she is a ninth-generation direct descendent of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Spotswood, who was Governor of Virginia from 1710-1722.

Lt Col Alexander SpotswoodIt was very interesting hearing from Christy – and being invited onto this Blog - because she is a ninth-generation direct descendent of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Spotswood, who was Governor of Virginia from 1710-1722. The Governor's father, Dr. Robert Spotswood, was surgeon to the British military post in Tangiers, Morocco; his grandfather, Sir Robert Spotswood, a Privy Councillor to King Charles I, was executed by Cromwell's Parliamentarians during the English Civil War. Governor Spotswood's great-grandfather John Spottiswoode was the Archbishop of Scotland and Chancellor to King Charles I, and is buried in Westminster Abbey. [See Westminster Abbey's page on John Spottiswoode: http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/people/john-spottiswood.] Alexander Spotswood not only had his own illustrious lineage, but his wife's goes back to Norman and Scottish royalty and nobility.

Spotsylvania County, Virginia, is named after the Governor ("sylvan" being Latin for "wood"), and anyone who has visited Colonial Williamsburg will know that he was responsible for the building of the stunning Governor's Palace .

Alexander Spotswood was an exciting and adventurous person by the sound of it: leading an expedition to the Blue Ridge Mountains (the first Colonials to travel so far inland) negotiating peace with the Iroquois Indians, and introducing a standard consistency for the quality of exported tobacco – which led to Virginia tobacco being the best in the world.

As far as my novels are concerned, Governor Spotswood was also responsible for the capture and execution of Edward Teach – the notorious pirate, Blackbeard.

Pirates were a menace to the entire Caribbean, Carolina and Virginia. Around 1715-1722, there were probably several thousand pirates lurking in the Atlantic and Caribbean, intent on taking a Prize (or two, or three, or four…) A 'Prize' was literally anything of value that the pirates could easily lay their hands on and sell for a profit, or use for themselves. Normally it was the cargo they were after – tobacco, rum, molasses, timber – gold and silver of course. They were not especially good sailors, and took poor care of their ships – why bother with the hard work of keeping a vessel "ship-shape" when it was far easier to capture another and take that instead?

Few pirates actually had piles of treasure packed into chests – and sadly there seems to be no evidence that they actually buried it! Most pirates made straight for the nearest port, Nassau, Tortuga, Port Royal, and spent their ill-gotten gains on rum and women.

Blackbeard was a particular menace, a thoroughly nasty piece of work. He blockaded Charleston Harbour and held the Governor's young son to ransom until he got what he wanted. Gold? Jewels? No – medical supplies, particularly very expensive mercury.

Blackbeard's head posted: Photo: http://shoutaboutcarolina.com/index.php/2010/08/most-famous-pirates-ships-legends-historic-photos/ Why mercury? Well it was thought of as a cure for a disease that pirates (indeed most sailors) were riddled with: syphilis. Blackbeard was probably suffering from this sexually transmitted disease – all the more awful, then, to learn that later that year (1718) he decided to "settle down" in North Carolina at Bath Town and marry the daughter of a wealthy merchant. Only his idea of 'settling' was to outwardly make it seem that he was an honest man, while secretly plundering every merchant ship that hailed within site of the Ocracoke and Pamlico River, claiming the cargo for himself and splitting the profits with the Governor of North Carolina. And the girl he married, Mary Ormond? She was his fourteenth wife, was sixteen years of age, and on their wedding night he forced her to prostitute herself with his crew. Gang rape, we would call it now.

Blackbeard's head posted: Photo: http://shoutaboutcarolina.com/index.php/2010/08/most-famous-pirates-ships-legends-historic-photos/ Why mercury? Well it was thought of as a cure for a disease that pirates (indeed most sailors) were riddled with: syphilis. Blackbeard was probably suffering from this sexually transmitted disease – all the more awful, then, to learn that later that year (1718) he decided to "settle down" in North Carolina at Bath Town and marry the daughter of a wealthy merchant. Only his idea of 'settling' was to outwardly make it seem that he was an honest man, while secretly plundering every merchant ship that hailed within site of the Ocracoke and Pamlico River, claiming the cargo for himself and splitting the profits with the Governor of North Carolina. And the girl he married, Mary Ormond? She was his fourteenth wife, was sixteen years of age, and on their wedding night he forced her to prostitute herself with his crew. Gang rape, we would call it now.  Colonial Williamsburg capitol

Colonial Williamsburg capitol

Williamsburg gaolBlackbeard being a menace to the Chesapeake and threatening the stability of the Virginia Tobacco Trade, Governor Spotswood decided to put an end to the foul Edward Teach. Technically, he was outside his jurisdiction, for North Carolina was not his domain, but he hired the use of two Royal Navy sloops and under the command of Lt. Maynard, sent them off to finish Blackbeard once and for all. We know the outcome of the desperate fight in the shallows of the Ocracoke because Maynard kept a meticulous logbook – and the records of the trials of the captured crew remain in Williamsburg to this day. Blackbeard was killed in the fight – although it took a lot to finish him off, while the captured crew were tried in the Capitol Building Court Room in Williamsburg and hanged.

Williamsburg gaolBlackbeard being a menace to the Chesapeake and threatening the stability of the Virginia Tobacco Trade, Governor Spotswood decided to put an end to the foul Edward Teach. Technically, he was outside his jurisdiction, for North Carolina was not his domain, but he hired the use of two Royal Navy sloops and under the command of Lt. Maynard, sent them off to finish Blackbeard once and for all. We know the outcome of the desperate fight in the shallows of the Ocracoke because Maynard kept a meticulous logbook – and the records of the trials of the captured crew remain in Williamsburg to this day. Blackbeard was killed in the fight – although it took a lot to finish him off, while the captured crew were tried in the Capitol Building Court Room in Williamsburg and hanged. So what has all this to do with my books?

Well, Bring It Close, the Third Voyage centres around those historical facts. Arrested for piracy after an indiscretion with an old flame, Jesamiah is held prisoner in Williamsburg's gaol. After his trial he is coerced into helping Spotswood make an end of Blackbeard – which suits Jesamiah because he, too, is keen to be rid of the man, who has threatened to kill him. Another worry – Jesamiah's beloved Tiola is in Bath Town, where Blackbeard resides.

Governor's Palace by Alexander SpotswoodI have visited Williamsburg twice to research the facts behind the story – every bit of each scene set there is accurate, well apart from the involvement of Jesamiah! I investigated the gaol, the court room, the palace – and the route Jesamiah was taken on from Gaol to Palace.

Governor's Palace by Alexander SpotswoodI have visited Williamsburg twice to research the facts behind the story – every bit of each scene set there is accurate, well apart from the involvement of Jesamiah! I investigated the gaol, the court room, the palace – and the route Jesamiah was taken on from Gaol to Palace. By entwining the real facts of history with an imaginary story of Jesamiah's adventures – and blending in the supernatural storyline of the ghost of Jesamiah's father and Tiola's knowledge that Blackbeard has sold his soul to the devil, the result is, I hope, a cracking good adventure story.

And who is to say that it was not Jesamiah who planned that attack on Blackbeard? You will not find his name in Maynard's logbook, but then, Jesamiah made it quite plain that he did not want to be mentioned…

That's why I love writing this sort of fiction – who knows what is true, and what isn't?

You are welcome to visit my website , join me on Facebook , or come aboard the Sea Witch page .___________________ Thank you so much, Helen. What fun to discover details about what made our ancestors tick—and what made them ticked-off (could it be, um, pirates??). I hope our blog readers will take this opportunity to discover your books and enjoy the adventures of fiction—and the real-life people who went before us. To find and purchase Helen Hollick's books or e-books, visit her website, www.helenhollick.net.

Now, about that book giveaway contest: Helen is running a competition for fans of her Sea Witch Facebook page to win a copy of one of her books (all new "likes" welcome), but I have been told where this particular treasure trove of the competition page is located! If you decide to enter, Good Luck! Here it is: http://helen-myguests.blogspot.com/p/competition-page.html.Please note the expiration date of the contest, though this article will stay up far longer.

Published on July 05, 2011 00:00

July 1, 2011

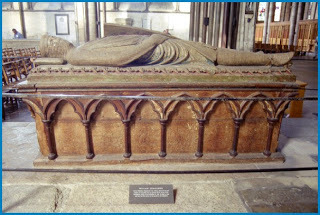

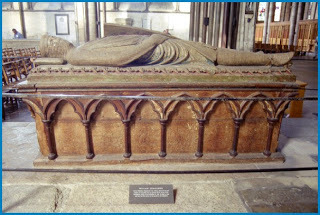

Tomb effigies

King John's tomb effigy in Worcester Cathedral, England, with Christy in 2004 Church Monumentsby George Herbert

King John's tomb effigy in Worcester Cathedral, England, with Christy in 2004 Church Monumentsby George Herbert While that my soul repairs to her devotion,

Here I intomb my flesh, that it betimes

May take acquaintance of this heap of dust;

To which the blast of death's incessant motion,

Fed with the exhalation of our crimes,

Drives all at last. Therefore I gladly trust

Visceral tomb of Eleanor of Castile, Lincoln CathedralMy body to this school, that it may learn

Visceral tomb of Eleanor of Castile, Lincoln CathedralMy body to this school, that it may learn To spell his elements, and find his birth

Written in dusty heraldry and lines;

Which dissolution sure doth best discern,

Comparing dust with dust, and earth with earth.

These laugh at jet and marble put for signs,

Euphemia de Clavering, 1269-1329, mother of Sir Ralph Neville II (1291-1367)To sever the good fellowship of dust,

Euphemia de Clavering, 1269-1329, mother of Sir Ralph Neville II (1291-1367)To sever the good fellowship of dust,And spoil the meeting. What shall point out them,

When they shall bow, and kneel, and fall down flat

To kiss those heaps, which now they have in trust?

Dear flesh, while I do pray, learn here thy stem

And true descent, that when thou shalt grow fat

Tomb of Yaroslav the Wise, Prince of Novgorod and Kiev, in St. Sophia Cathedral at KievAnd wanton in thy cravings, thou mayst know

Tomb of Yaroslav the Wise, Prince of Novgorod and Kiev, in St. Sophia Cathedral at KievAnd wanton in thy cravings, thou mayst knowThat flesh is but the glass which holds the dust

That measures all our time; which also shall

Be crumbled into dust. Mark, here below

How tame these ashes are, how free from lust,That thou mayst fit thyself against thy fall.

Effigy of Richard "Strongbow" de Clare, Dublin Ireland

Effigy of Richard "Strongbow" de Clare, Dublin Ireland

Published on July 01, 2011 00:01

June 15, 2011

The Little Ice Age, 1300-1800

The Fur Cloak, by Rubens, about 1636-1639. Is history repeating itself? (Again?) Is there global cooling in our future? Scientists are predicting a period of less solar activity. See Associated Press article following.

The Fur Cloak, by Rubens, about 1636-1639. Is history repeating itself? (Again?) Is there global cooling in our future? Scientists are predicting a period of less solar activity. See Associated Press article following. Our ancestors survived conditions with considerably less resources than we have available. There was no central heating in their homes and shops, of course, and fuel (peat, coal, and wood) was just as expensive, or more so, as the fuels we consume today. Most people just couldn't afford the luxury of warmth in winter. They didn't change clothes or bathe much, especially in cold weather when they'd have to haul and heat water. They shared beds near a kitchen hearth, too. We who need our personal space would never survive that lifestyle!

This is just my observation from studying genealogy, not backed up with statistics, but it looks like family size burgeoned during the global temperature dip of the 16th and 17th centuries: maybe the long, freezing nights were not all that boring! Certainly, a number of family members of William and Mary Barrett Dyer had birthdays in September through December. So what really happened during the deep freezes back in January, February, and March?

The Little Ice Age, from about 1317-1800, began with catastrophic floods, crop failure, and domestic animal deaths (which brought on economic depression), harsh winters—and starvation. Epidemics raged unchecked, and millions died in the bubonic plague outbreak in 1348-1350. Because so many laborers (peasants tied to the land, who owed service to their landlords) died, cathedral and castle building ground to a halt for years.

The extended Bartholomew family of Burley, early 1600s, with their seven surviving children. Two sons emigrated to colonial Massachusetts. The family are not among my ancestors.

The extended Bartholomew family of Burley, early 1600s, with their seven surviving children. Two sons emigrated to colonial Massachusetts. The family are not among my ancestors.Of course our ancestors knew nothing about it, but they experienced the effects of a plunge in sunspot activity in the 1600s, which corresponded with the coldest years of the Little Ice Age. Specifically during Mary Dyer's lifetime, 1611-1660, there was the time of famines, waves of bubonic plague across Europe, the Thirty Years War, the Great Migration to America, the English Civil War, and the explosion of African slave trade to the Americas and Europe.

Iceland's ports were ice-bound by miles for several years, and trade and passenger shipping from Europe was forced far south to avoid sea ice. Boston Harbor (sea water) froze over for two to three miles out, hard enough to walk on, for two weeks at a time.

Journal of Governor John Winthrop—January 1638: "About thirty persons of Boston going out in a fair day to Spectacle Island to cut wood, (the town being in great want thereof,) the next night the wind rose so high at N.E. with snow, and after at N.W. for two days, and then it froze so hard, as the bay was all frozen up, save a little channel. In this twelve of them gate to the Governor's Garden [an island], and seven more were carried in the ice in a small skiff out at Broad Sound, and kept among Brewster's Rocks, without food or fire, two days, and then the wind forbearing, they gate to Pullin Point, to a little house there of Mr. Aspenwall's. Three of them got home the next day over the ice, but their hands and feet frozen. Some lost their fingers and toes, and one died. The rest went from Spectacle Island to the main, but two of them fell into the ice, yet recovered again. In this extremity of weather, a small pinnace was cast away upon Long Island [in Boston Harbor] by Natascott, but the men were saved and came home upon the ice."

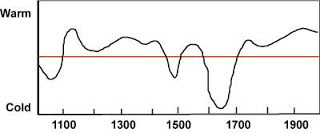

The Little Ice Age "peaked" in Mary Barrett Dyer's lifetime—the coldest years in many centuries were those she spent in colonial America. This graph shows the severity of winters in Europe and North America from 1000-2000 AD. The absolute coldest period, 1600-1675, coincides with William and Mary Dyer's life spans.

The Little Ice Age "peaked" in Mary Barrett Dyer's lifetime—the coldest years in many centuries were those she spent in colonial America. This graph shows the severity of winters in Europe and North America from 1000-2000 AD. The absolute coldest period, 1600-1675, coincides with William and Mary Dyer's life spans. More on the Dyers: Mary Dyer and freedom of conscience: http://bit.ly/kuTf4KArticle on Mary Dyer's individualism against orthodoxy and the established church: http://bit.ly/ivWJbO For a timeline on William and Mary Dyer's life together, see my post here. To learn more about the Dyers' life, join her Facebook friends.

The Dyers lived in Boston from 1635 to the spring of 1638, then co-founded Portsmouth, Rhode Island, about 60 miles away. One year later, they co-founded the city of Newport, Rhode Island, where they developed a large farm and the seaport.

When Mary Dyer was making a winter trip back to America after several years in England, her ship diverted to Barbados because of severe storms. From a letter written in Barbados on Feb 25, 1657: "A ship came in hither, which was going to New England, but the storms were so violent that they were forced to come hither, [until] the winter there was nearly over. In this ship were two Friends, Anne Burden of Bristol, and one Mary Dyer from London; both lived in New England formerly, and were members cast out of their [Puritan] churches. Mary goes to her husband who lives upon Rhode Island..."

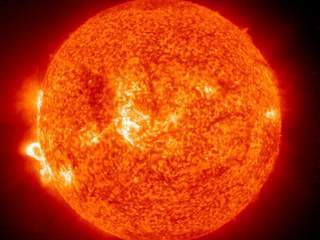

A NASA website says, "During the coldest part of the Little Ice Age, from 1645 to 1715, there is believed to have been a decrease in the total energy output from the Sun, as indicated by little or no sunspot activity. Known as the Maunder Minimum, astronomers of the time observed only about 50 sunspots for a 30-year period as opposed to a more typical 40-50,000 spots. The Sun normally shows signs of variability, such as its eleven-year sunspot cycle. Within that time, it goes from a minimum to a maximum period of activity represented by a peak in sunspots and flare activity."

More from NASA: "Between the mid-1600s and the early 1700s the Earth's surface temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere appear to have been at or near their lowest values of the last millennium. European winter temperatures over that time period were reduced by 1.8 to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1-1.5 Celsius). This cool down is evident through derived temperature readings from tree rings and ice cores, and in historical temperature records, as gathered by the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and the University of Virginia."

http://media2.abc15.com//photo/2011/06/15/sun_20110615082730_320_240.JPG

A Solar and Heliospheric Observatory image shows Region 486 that unleashed a record flare (lower left) November 18, 2003 on the sun. The spot itself cannot yet be seen but large, hot, gas-filled loops above this region are visible.

A Solar and Heliospheric Observatory image shows Region 486 that unleashed a record flare (lower left) November 18, 2003 on the sun. The spot itself cannot yet be seen but large, hot, gas-filled loops above this region are visible. Photographer: Getty Images. Goodnight sun: Scientists predict sunspots might disappear for yearsBy: Associated PressUpdate as of June 15, 2011

WASHINGTON - The sun is heading into an unusual and extended hibernation, scientists predict. Around 2020, sunspots may disappear for years, maybe decades.

But scientists say it is nothing to worry about. Solar storm activity has little to do with life-giving light and warmth from the sun. The effects from a calmer sun are mostly good.

There'd be fewer disruptions of satellites and power systems. And it might mean a little less increase in global warming. It's happened before, but not for a couple centuries.

"The solar cycle is maybe going into hiatus, sort of like a summertime TV show," said National Solar Observatory associate director Frank Hill, the lead author of a scientific presentation at a solar physics conference in New Mexico.

Scientists don't know why the sun is going quiet. But all the signs are there. Hill and colleagues based their prediction on three changes in the sun spotted by scientific teams: Weakening sunspots, fewer streams spewing from the poles of the sun's corona and a disappearing solar jet stream.

Those three cues show, "there's a good possibility that the sun could be going into some sort of state from which it takes a long time to recover," said Richard Altrock, an astrophysicist at the Air Force Research Laboratory and study co-author.

The prediction is specifically aimed at the solar cycle starting in 2020. Experts say the sun has already been unusually quiet for about four years with few sunspots -- higher magnetic areas that appear as dark spots.

The enormous magnetic field of the sun dictates the solar cycle, which includes sunspots, solar wind and ejection of fast-moving particles that sometimes hit Earth. Every 22 years, the sun's magnetic field switches north and south, creating an 11-year sunspot cycle. At peak times, like 2001, there are sunspots every day and more frequent solar flares and storms that could disrupt satellites.

Earlier this month, David Hathaway, NASA's top solar storm scientist, predicted that the current cycle, which started around 2009, will be the weakest in a century. Hathaway is not part of Tuesday's [June 14, 2011] prediction.

Altrock also thinks the current cycle won't have much solar activity. He tracks streamers from the solar corona, the sun's outer atmosphere seen during eclipses. The streamers normally get busy around the sun's poles a few years before peak solar storm activity. That "rush to the poles" would have happened by now, but it hasn't and there's no sign of it yet. That also means the cycle after that is uncertain, he said.

Matt Penn of the National Solar Observatory, another study co-author, said sunspot magnetic fields have been steadily decreasing in strength since 1998. If they continue on the current pace, their magnetic fields will be too weak to become spots as of 2022 or so, he said.

Jet streams on the sun's surface and below are also early indicators of solar storm activity, and they haven't formed yet for the 2020 cycle. That indicates that there will be little or delayed activity in that cycle, said Hill, who tracks jet streams.

"People shouldn't be scared of this," said David McComas, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, who wasn't part of the team. "This is about the magnetic field and the ionized gas coming out of the sun. It's a reduction in that, not the light and the heat."

So sunspot reduction is to blame?There are questions about what this means for Earth's climate. Three times in the past the regular 11-year solar cycle has gone on an extended vacation -- at the same time as cool periods on Earth.

OK, maybe notSkeptics of man-made global warming from the burning of fossil fuels have often pointed to solar radiation as a possible cause of a warming Earth, but they are in the minority among scientists. The Earth has warmed as solar activity has decreased.

Andrew Weaver, a climate scientist at the University of Victoria, said there could be small temperature effects, but they are far weaker than the strength of man-made global warming from carbon dioxide and methane. He noted that in 2010, when solar activity was mostly absent, Earth tied for its hottest year in more than a century of record-keeping.

Hill and colleagues wouldn't discuss the effects of a quiet sun on temperature or global warming.

"If our predictions are true, we'll have a wonderful experiment that will determine whether the sun has any effect on global warming," Hill said.

Published on June 15, 2011 22:46

June 1, 2011

Mary Dyer and freedom of conscience

"It is not the glorious battlements, the painted windows, the crouching gargoyles that support a building, but the stones that lie unseen in or upon the earth. It is often those who are despised and trampled on that bear up the weight of a whole nation." ~John Owen, English Puritan minister, 1616–1683.

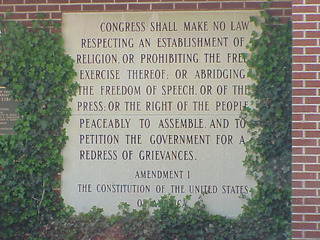

June 1, 1660 was a landmark date in American history. Its relation to civil rights guaranteed by the US Constitution's Bill of Rights should be noted, specifically the 1st Amendment regarding freedom of religion (to worship or not, as your own conscience dictates), and freedom of speech and assembly.

June 1, 1660 was a landmark date in American history. Its relation to civil rights guaranteed by the US Constitution's Bill of Rights should be noted, specifically the 1st Amendment regarding freedom of religion (to worship or not, as your own conscience dictates), and freedom of speech and assembly. Mary Barrett Dyer, hanged in Boston on June 1, 1660, was martyred for liberty of conscience that Americans enjoy under the Constitution's Bill of Rights. Other countries have modeled their constitutions and rights on those of the United States, so these liberties have become global.

In 2010, on the 350th anniversary of Mary Dyer's martyrdom, there was no mention of her in newspapers or online. No events in Boston, Rhode Island, or Washington, DC. No political or religious movements made mention of the sacrifice of the only female religious martyr in America.

Torture and persecutionIn the late 1650s, Quakers had been persecuted for their nonconformism by having their tongues bored with a hot awl; men and women were stripped bare to the waist and flogged with up to 30 strokes of the thrice-knotted lash, to add more injury to each stroke; they had their ears either nailed to a post, or sliced off altogether; without a trial, they were thrown in earthen-floored jail cells, sometimes for months, with no candle or heat in New England's harsh winters; prisoners were beaten several times a week. Even non-Quakers whose consciences were pricked by this harsh treatment were jailed, whipped, heavily fined, and disfranchised (lost their civil rights and vote) for harboring or sympathizing publicly with Quakers.

Contrary to popular opinion in genealogy sites, Mary Barrett Dyer wasn't hanged "for the crime of being a Quaker." It wasn't a crime to be a Quaker! However, they didn't attend Puritan worship or teaching services or pay required tithes, didn't keep the Sabbath holy, and criticized the government leaders for their cruelty. Mary Dyer provoked her own trials and execution for what we'd call civil disobedience, by repeatedly defying the totalitarian Puritan regime headed by Massachusetts Governor John Endecott. The Massachusetts Bay founders believed that religious error or dissent from their dogma was treasonable.

Endecott, a religious zealot, had a checkered past, leaving an illegitimate son in England before he emigrated to Salem, Massachusetts in 1629; treasonably cutting the "idolatrous" cross from the British flag; a Massachusetts committee reported in 1634 "that they apprehend [Endecott] had offended therein many ways, in rashness, uncharitableness, indiscretion and exceeding the limits of his calling;" acting in ways that endangered the patent that was their title to land in New England; creating a mint in Boston that made unauthorized—and therefore counterfeit—coins with a 1652 imprint for 30 years (so if the English government confiscated the minting, Boston could claim the coins were all from 1652 when they had little oversight during the English political upheaval); and punishing his indentured servant girl with 32 lash-stripes and public humiliation for fornication, bearing a child out of wedlock, and insistently naming his son as the predatory father (which, of course, would make John Endecott the father of a rapist and grandfather of a lowly servant's bastard—can't have that!).

Endecott, a religious zealot, had a checkered past, leaving an illegitimate son in England before he emigrated to Salem, Massachusetts in 1629; treasonably cutting the "idolatrous" cross from the British flag; a Massachusetts committee reported in 1634 "that they apprehend [Endecott] had offended therein many ways, in rashness, uncharitableness, indiscretion and exceeding the limits of his calling;" acting in ways that endangered the patent that was their title to land in New England; creating a mint in Boston that made unauthorized—and therefore counterfeit—coins with a 1652 imprint for 30 years (so if the English government confiscated the minting, Boston could claim the coins were all from 1652 when they had little oversight during the English political upheaval); and punishing his indentured servant girl with 32 lash-stripes and public humiliation for fornication, bearing a child out of wedlock, and insistently naming his son as the predatory father (which, of course, would make John Endecott the father of a rapist and grandfather of a lowly servant's bastard—can't have that!).  The colony and later state of Rhode Island was founded by Roger Williams in the 1630s as a haven for freedom of conscience, and that's where Mary and her husband and children made their home after being ejected from Massachusetts in 1637 over a religious matter prosecuted by the church state. Mary studied Quaker beliefs in England for several years, and returned to Boston only to be thrown into jail for 10 weeks with no notice to her husband in nearby Rhode Island.

The colony and later state of Rhode Island was founded by Roger Williams in the 1630s as a haven for freedom of conscience, and that's where Mary and her husband and children made their home after being ejected from Massachusetts in 1637 over a religious matter prosecuted by the church state. Mary studied Quaker beliefs in England for several years, and returned to Boston only to be thrown into jail for 10 weeks with no notice to her husband in nearby Rhode Island. Though Mary could have lived out her life in safety, she believed she was called by God to try the bloody religious laws of Connecticut and Massachusetts, and she boldly entered their territory to both preach, and support her Friends in the faith by visiting them in prison.

Prepared to dieHer letters written from Boston prison to Governor Endecott, her actions, and her statements at trial demonstrate to us that she willingly sacrificed her life to stop the torture and persecution of people who were obeying the voice of God in their hearts. She wrote, "Be not found Fighters against God, but let my Counsel and Request be accepted with you, To repeal all such Laws, that the Truth and Servants of the Lord, may have free Passage among you and you be kept from shedding innocent Blood…My life is not accepted, neither availeth me, in Comparison of the Lives and Liberty of the Truth and Servants of the Living God… yet nevertheless, with wicked Hands have you put two of them to Death, which makes me to feel, that the Mercies of the Wicked is Cruelty. I rather choose to die than to live, as from you, as Guilty of their innocent Blood… Therefore I leave these Lines with you, appealing to the faithful and true Witness of God, which is One in all Consciences, before whom we must all appear; with whom I shall eternally rest, in Everlasting Joy and Peace, whether you will hear or forebear: With him is my Reward, with whom to live is my Joy, and to die is my Gain."

Knowing that there was a death sentence hanging over her, she deliberately avoided her husband who would have stopped her, and returned to Boston, where she was arrested and jailed. She was convicted and condemned on May 31, 1660, and was hanged the next day, on June 1.

The shock over Mary Dyer's death crossed the Atlantic immediately, and King Charles II put an end to the New England death penalty for religious practice, requiring that capital cases be tried in England. Public outrage in New England over Mary's death actually consolidated sympathy for Quakers, Baptists, Jews, and others who refused to conform to Puritanism. Even some of the New England Puritans demonstrated their opposition to the harsh treatment of people of conscience, and suffered imprisonment, banishment, confiscation of property, and heavy fines. A number of those who'd suffered persecution converted to the Quaker faith. Gradually, the torture and persecution slowed.