Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 19

October 27, 2012

The wedding in 1633

© Christy K Robinson

A Flemish wedding, perhaps between 1615 and 1630.

A Flemish wedding, perhaps between 1615 and 1630. Not a white bridal gown to be seen.Mary Barrett and William Dyer were married at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church in Westminster (London), on September 27, 1633. One year later, on their first anniversary, they buried their newborn son at St. Martin-in-the-Fields. And on their 26thwedding anniversary in 1659, Mary was taken to the gallows in Boston, Massachusetts, and stood there with a hanging rope around her neck, prepared to die (but reprieved on that occasion).

According to legend passed down in Dyer descendants, the dress that Mary wore for the wedding ceremony was made of white silk, with gold and silver embroidery worked in insects and flowers.

A fragment of silk with (tarnished) silver thread, said to have

A fragment of silk with (tarnished) silver thread, said to havebelonged to Mary Dyer, from her wedding dress.

Another claim is that Mary Dyer wore that wedding dress to her execution on June 1, 1660, and that it was cut up to give as mementos or relics to family and friends. Alrighty, then… Mary had wintered on Shelter Island, then had skipped going home to Newport by sailing straight to Providence, then walking 60 miles to Boston. On one of the nights before she arrived and she would have been camping out or sheltering roughly, there was a terrific lightning storm. Upon arriving in Boston, she was arrested, had her possessions confiscated, and was put in prison: not a sterile environment, by any means, but rather, a dirt or mud floor crawling with vermin. And really, what woman (in any century) would wear a wedding dress to her own hanging, even if she hadn't traipsed through sea and muddy land, and sat in prison for two weeks while wearing it? No, it doesn’t add up.

Helene Fourment, wife of

Helene Fourment, wife of Peter Paul Rubens, in her 1630

wedding dress. Note the split skirt,

brocade, raised waist, and huge sleeves.

Also, the ringlet curls around the face

were fashionable, being worn by

Queen Henrietta Maria. I've seen references to the wedding dress story, but I wonder if it's a Victorian construct, like Mary’s invented royal genealogy and secret birth. Perhaps the garment with this embroidery did belong to Mary and was her own handiwork, but we'd never know for sure without fabric and dye analysis, we'd never prove it belonged to Mary, and there’s no guarantee it was from a wedding dress.

White wedding dresses didn't become fashionable until about 1840. For centuries, women wore their nicest go-to-meeting dresses to be married in, but unlike today, they wore them again and again for other occasions. The colors most commonly used were deep reds and greens. Blue was the desirable color to symbolize loyalty. The skirt for a wedding would have been split in front to reveal another skirt beneath, perhaps in silk brocade.

["Woman's jacket [English] (23.170.1)". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

["Woman's jacket [English] (23.170.1)". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-o... (May 2010)]This is an embroidered white jacket from 1616 England, with flowers, insects, gold and silver thread, popular during Mary’s childhood years. But once Henrietta Maria of France became queen consort to England's Charles I in 1625, styles changed to a higher waist with full, stuffed sleeves, making this stiff, fitted model less fashionable and rather dated by 1633. Check out the description of the jacket at http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/23.170.1

In my novel, I've made a small nod to the legend, if that's what it is, by having Mary embroider a bodice to go with a colored skirt. Seamstresses often changed sleeves, collars, bodices, skirts, etc., by picking out seams and reconstructing them in a new style, and embroidering or embellishing with lace and ribbons, which would lend a reason for the rumor of the gold bodkin (see below).

The groom in a wedding dressed colorfully, with knee breeches and ribbon rosettes at his knees. He’d have worn a long waistcoat (vest) of a rich fabric, over a white linen shirt, with a knee-length jacket over all. There would have been plenty of lace at his neck and down the front, and on his cuffs. In his large hat, he may have worn an ostrich feather. William Dyer was a milliner, which provided leather fashion accessories for men. He would certainly have worn fancy boots with turned-down top cuffs, and embroidered or beaded leather gloves.

Marriage and the Book of Common PrayerLate September and all of October was a busy time for weddings, because in the agrarian economy, the harvests were stored, and people had a bit more time to leave the farm in the care of servants and visit in a city for wedding festivities. The custom of the day was for the wedding to be performed at or near the door of the church, using the liturgy in the Book of Common Prayer, and to be followed by a Communion/Eucharist service at the chancel.

(When Prince William and Catherine Middleton were married in April 2011, I followed the words of the liturgy by reading the marriage service in the 1549 BCP as the Archbishop of Canterbury spoke it. Same words!)

An early 17th-century wedding,

An early 17th-century wedding, during the Elizabethan

or King James I years.Puritans, on the other hand, often refused to be married in churches, believing that marriage was not a sacrament (they recognized only baptism and Eucharist/Communion), and that it was a civil union. In addition, they wished to avoid the Anglican service performed from the BCP, seeing it as too closely-related to Roman Catholic liturgy. Puritans of the early to mid 17th century would often be wed by magistrates in taverns, homes, or places of business. The fact that the Dyers were married in the church tells us that at that time, they were following Anglican, not Puritan, tradition.

St. Martin-in-the-Fields parish contained fine homes of important government members. The house that William Dyer leased after living in it during his apprenticeship was around the corner from Thames-side York House and Durham House, large residences for important members of government. The ministers of St. Martin’s were Dr. Thomas Mountford and William Bray, both of whom had strong ties to William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, so we can be sure that the Dyer wedding would have been Anglican, through and through. Afterward, there would have been a feast and drinking, with hired musicians, dancing, and perhaps games. There may have been a bride-cake. It was probably an expensive party, considering their business contacts, neighbors, and living in a posh area.

The gold bodkin

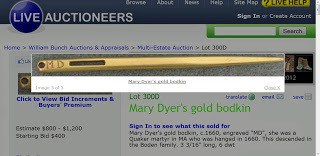

This golden bodkin, said to be Mary Dyer’s,

This golden bodkin, said to be Mary Dyer’s, was auctioned Feb. 21, 2006.

http://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/1688497 The wedding dress story is accompanied by a story that Mary Dyer’s gold bodkin was also passed down to her descendants. A bodkin is a tool with a blunt or rounded point that helps pull drawstrings or ribbons through a casing (today, a strip of elastic for a skirt waistline). My bodkin looks like a safety pin on a 12-inch metal rod. A bodkin is not the same as an embroidery needle that a seamstress would use to decorate cloth. An embroidery needle has a sharp tip, and a long eye to accommodate the multiple threads or metallic wire. It’s quite possible that Mary used a bodkin as she constructed clothing for her husband, children, and servants.

If the story is true, and if Mary owned a gold bodkin, and if it was actually this one: a gold bodkin tells us that it was probably a gift from an important, wealthy person, and that it came to her when she’d been married (because of the D for Dyer stamp). Perhaps it was a wedding gift, or it came sometime after the 1633 marriage.

The Puritan laws of Massachusetts Bay from 1634 on, forbade women to wear gold and silver embroidery, lace, or silk scarves. If they disobeyed, they could receive the same penalties as men who were drunks, petty thieves, or domestic abusers: ten lashes of the whip and time in the stocks. On the other hand, they employed lace makers to keep their husbands looking spiffy.

Hmmm, the underlying conflict is not so different from laws men attempt to impose on women in the 21st century.

Published on October 27, 2012 02:02

September 26, 2012

Making a Mary Dyer costume for school

© Judy Perry

School children (Mary Dyer at center)

School children (Mary Dyer at center)present their history reports in constume.I remember once, when looking for information on how to make Anne Boleyn-style French hoods, coming upon either the blog or the website of a historical re-enactor, who took great pains to point out that she was not a costumer; she was the real deal!

But we don't all have the time and means to be the real deal and thus I proudly will admit myself to be a costumer – as long as it looks sorta, kinda correct and nobody in the general public can tell otherwise, I'm a happy camper.

Especially when I'm given less than two weeks to come up with male and female “American colonial” costumes for my twin children. Each also had to do a stand-up talk with one of those three-paneled “science fair” type cardboard displays. My daughter wanted to do a famous person, but didn't like any of the options that were available to her. (What the teacher meant by “American colonial” was Revolutionary late 18th-century, whereas Mary Dyer lived in the mid-17th century.) Remembering Christy's research into Mary Barrett Dyer, I proposed Mary as a candidate and, after I supplied some information, my daughter's teacher agreed.

I didn't have much time and I didn't want to spend a lot of money. Basically, under such circumstances, you have three choices: •Buy a really cheap pre-made costume at a place like Party City (cheap quality but expensive). •Buy a pattern, fabric, and make it yourself (expensive and expensive). •Wing it (see below).

Winging it

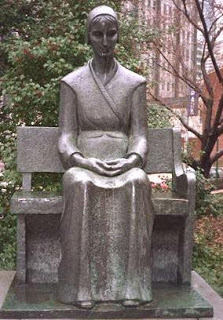

This can be either totally flying by the seat of your pants or by poring over numerous books on period costume that you might not have on hand (I didn't). Therefore, I went by the two images on Christy's website and decided to start with the bonnet and skirt (and maybe apron?) as shown on the Boston statue of Mary Dyer. The important thing in winging it, especially if you are not an experienced seamstress, is to 1) simplify, simplify, simplify! And, 2) use really cheap materials wherever possible.

This can be either totally flying by the seat of your pants or by poring over numerous books on period costume that you might not have on hand (I didn't). Therefore, I went by the two images on Christy's website and decided to start with the bonnet and skirt (and maybe apron?) as shown on the Boston statue of Mary Dyer. The important thing in winging it, especially if you are not an experienced seamstress, is to 1) simplify, simplify, simplify! And, 2) use really cheap materials wherever possible. Coif Materials:

•Millinery tape •Cheap white sheet •Double-edge binding tape •Fray-Check/Stitch Witchery (optional)

Before trotting off to your local fabric store to find the millinery tape, which was traditionally used by haberdasheries, you should be forewarned that they probably won't know what you are talking about. That's okay; ask them to direct you to their drapery department. It's a 3” wide almost grosgrain “drapery” tape. I measured (well, actually, couldn't find my measuring tape, so I just held the tape up and around the top of her head to the desired length) the proper length of drapery tape and cut. You'll probably want to hem that edge or use one of the iron-on hemming products/anti-fray products so that the cut end doesn't fray.

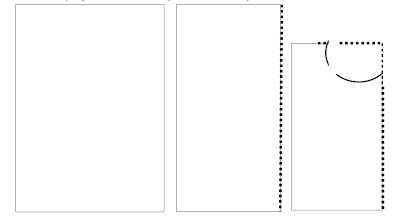

Secondly, buy the cheapest (choice of color) sheet you can find at Wal-Mart or other store in a twin bed size. Cut a circular-shaped piece of the sheet such that it's a little shorter than the millinery tape piece (to get a reasonably-shaped circle, fold the sheet vertically and then again just a little bit horizontally and cut a ¼ circle). Fold under into a straight line the portion of the circle that will fit along the top/back of the millinery tape. Dashed lines represent fold lines.

This should result in something like the following:

First pin the straight-edge onto itself, then hem the semi-circular portion (or use the non-sewing hemming products). Sew the straight-edge to the center of the length of the millinery tape, right-edges facing each other (meaning you'll be sewing on the wrong side). Decide how long you want the under-the-chin tie strips and cut two from the bias tape. Sew them to the under-side of the millinery tape up near the ears and where the semi-circular piece meets the millinery tape. Gather the edges of the semi-circular at the bottom to create a “pouf.”

First pin the straight-edge onto itself, then hem the semi-circular portion (or use the non-sewing hemming products). Sew the straight-edge to the center of the length of the millinery tape, right-edges facing each other (meaning you'll be sewing on the wrong side). Decide how long you want the under-the-chin tie strips and cut two from the bias tape. Sew them to the under-side of the millinery tape up near the ears and where the semi-circular piece meets the millinery tape. Gather the edges of the semi-circular at the bottom to create a “pouf.”The reason for using a sheet is simple: it's about the cheapest form of fabric you can buy! This means you can afford to experiment and toss anything that doesn't work out. Even after discarding a few circles and making the apron, I had plenty of white fabric left over. This coif/bonnet simply involved measuring lengths and circle sizes, cutting them and sewing them. Easy-peasy!

Above you can see the finished product, both by itself as well as on my daughter;

Above you can see the finished product, both by itself as well as on my daughter; the pouf holds in her hair for modesty's sake. Skirt Materials & Construction •Twin sheet of desired skirt (and blouse) color •Elastic ribbon or banding. •Iron-on hem product and/or Fray Check •Set of hemostats OR a large, well-made safety pin. Mary Dyer would call it a "bodkin." Here is where the additional benefits of using sheets really kicks in. The first reason I gave was that it is about the cheapest fabric you can buy. Now, let's imagine that, somehow, in a mysterious parallel universe, you could afford to buy fabric the size of a twin sheet for the same amount of money as buying the sheet. Yes, but... that same piece of fabric would have two selvage edges (which wouldn't need to be hemmed and two cut edges, which would need to be hemmed. With a sheet, you have four hemmed edges! Cuts down your work considerably, especially in making the skirt and apron.

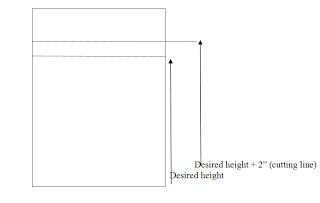

For the skirt, measure how long you'd like for the skirt to be, then add 2” or so and cut that sheet horizontally at that mark. If you use the entire width of the sheet, you now have a hemmed bottom and two hemmed sides!

For the skirt, measure how long you'd like for the skirt to be, then add 2” or so and cut that sheet horizontally at that mark. If you use the entire width of the sheet, you now have a hemmed bottom and two hemmed sides! Now you need to make an upper-casing along the cut line. The purpose of the casing – which is essentially a hemmed-off channel at the top of the skirt – is to carry the elastic ribbon which will make the skirt puffy and easy to pull on over the hips. The casing is the reason for adding the extra 2” at the top of the skirt. You have three options here: FrayCheck the rough top edge, then fold over by an inch and hem; Fold under the rough edge by 1/8” and then by nearly an inch and hem; Hem the 1/8 edge, fold again by about an inch and hem. Remember that “hemming” means using either a StitchWitchery-type of product OR sewing. Stretch the elastic tape a bit to a comfortable size for the wearer of the costume and cut that amount.

Now sew the two side edges together up to the line of the casing hem. Attach either the hemostats OR the safety pin to one end of the elastic tape/ribbon and gradually begin inserting it int one end of the casing. Don't allow the other end to be drawn into the casing! Stretch it and gather the casing until both ends exit just beyond the casing's sides. Here you can either sew them together or tie them shut. Now you can stitch shut the two ends of the casing, hiding the elastic inside of them.

Now sew the two side edges together up to the line of the casing hem. Attach either the hemostats OR the safety pin to one end of the elastic tape/ribbon and gradually begin inserting it int one end of the casing. Don't allow the other end to be drawn into the casing! Stretch it and gather the casing until both ends exit just beyond the casing's sides. Here you can either sew them together or tie them shut. Now you can stitch shut the two ends of the casing, hiding the elastic inside of them. Congratulations! You now have a skirt! Do likewise for the apron (for which I used my white sheet instead of the gray that I used for the skirt), only make the casing a separate sewn rectangle and, pinning right side to right side (with wrong side facing the sewer), sew the separate “casing” which we will now call an “apron string” and use it to tie the apron around the waist.

My sewing machine died before I could make a blouse out of the matching gray colored sheet (regrettably, only after I'd freehanded the blouse pattern), so I went with one of Sophie's white cotton karate gi tops. You can see the final results below:

Yes, I made portions of her brother's costume, as well.

Yes, I made portions of her brother's costume, as well..

*****

Judy Perry is a university educator in computer science, and is author of a blog on Katherine Swynford.

Thank you, Judy, for documenting your DIY project on Mary Dyer, and sharing your resourcefulness with desperate moms everywhere, trying to come up with a project for their children!

Published on September 26, 2012 14:53

September 19, 2012

The Ghost of Mary Dyer

The Founding Fanatics The Ghost of Mary Dyer

by David Macary, guest author

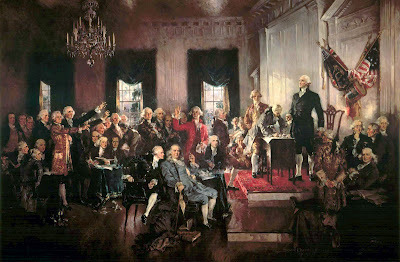

Although we regularly hear people (commentators, politicians, citizens) refer with pride to our Founding Fathers, it’s unclear whether they’re familiar with the relevant dates. Because if they had done the arithmetic, they surely would’ve noticed that every one of these illustrious “founders” had been born more than a century after this country was already formed.

Although we regularly hear people (commentators, politicians, citizens) refer with pride to our Founding Fathers, it’s unclear whether they’re familiar with the relevant dates. Because if they had done the arithmetic, they surely would’ve noticed that every one of these illustrious “founders” had been born more than a century after this country was already formed.Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in America, was established in 1607, and Plymouth, the second settlement, was established in 1620. By contrast, George Washington was born in 1732, John Adams in 1735, Thomas Jefferson in 1743, and James Madison in 1751.

Technically, these men didn’t “found” us. What they did was engineer our independence from England and invent our federal government, two magnificent achievements that set us on the successful course we’ve followed ever since. But let’s be clear: This country’s ethos—its customs, social rituals, religious beliefs, rural economy, national character—had been in place for a 150 years (that’s six generations) before Jefferson, Madison, et al, ever hung out their shingles.

We were taught in school that the Pilgrims came to America in order to practice “religious freedom.” While that statement is more or less accurate, what they fail to mention is that the Puritans were 17th-century England’s version of the Taliban. These religious zealots wanted to “purify” Christianity (hence “Puritans”) in much the same way that the Taliban wants to purify Islam.

Indeed, if we wished to be brutally honest, we could say that America was founded by a bunch of religious fanatics, and that it was the framers of the Constitution (educated products of the Enlightenment) who, bless their hearts, saved us from them.

How fanatical were they? Fanatical enough, in 1660, to execute the first female in the colonies. Her name was Mary Dyer. She, along with three male associates [Robinson, Stevenson, Leddra], were hanged by Massachusetts Bay Colony authorities. Dyer and the men had repeatedly ignored warnings not to set foot in Massachusetts, where Quakerism was outlawed, and when the warnings went unheeded, the Colony hanged them.

How fanatical were they? Fanatical enough, in 1660, to execute the first female in the colonies. Her name was Mary Dyer. She, along with three male associates [Robinson, Stevenson, Leddra], were hanged by Massachusetts Bay Colony authorities. Dyer and the men had repeatedly ignored warnings not to set foot in Massachusetts, where Quakerism was outlawed, and when the warnings went unheeded, the Colony hanged them.One can think of many religious people who deserve to be hanged, but Quakers aren’t among them. In fact, Quakerism, with its pacifism and equality for women, seems like one of the more enlightened, dignified religions. But in 1660, the good citizens of Massachusetts chose to kill a group of settlers whose only crime was belonging to another faith and defying the orthodox theocracy. And they killed them in the name of Jesus Christ.

As far as theology goes, our neighbors to the north are, by all accounts, nowhere near as demonstrably religious as we are. A few years ago, I saw Kim Campbell (former Prime Minister of Canada) on Bill Maher’s HBO television show. The panel was discussing the comparative role that religion played in the politics of Canada and America.

Reminded of the fact that George W. Bush had declared, after announcing his candidacy, that he believed God wanted him to run for president, Campbell observed that if a Canadian politician had said the same thing, people would think he was “mentally ill.” And as many will recall, during the 2008 Republican primary, three candidates (Tom Tancredo, Sam Brownback and Mike Huckabee) proudly admitted that they didn’t believe in evolution.

Our history is filled with paradoxes. We embrace founders who didn’t actually “found” us, we applaud the Pilgrims for seeking religious freedom when, in fact, they were vehemently intolerant, and we assume we were established as a reverently Christian, God-fearing nation even though the framers took careful steps to ensure that we would never become a theocracy.

In this post-New Deal, post-industrial milieu we find ourselves, we have both kinds of voters: the kind who vote for candidates on the basis of their positions on specific issues (health care, tax reform, trade policy, etc.), and the kind who ignore the boring nuts-and-bolts stuff and simply vote for the candidate they regard as the “most religious.”

And when the Tea Party says that they “want their country back,” and evangelicals say that we will never again be the nation we once were until “we put Jesus Christ back into our lives,” we’re reminded of not only how polarized we are, but of how the ghost of Mary Dyer—the first woman in Colonial America to be executed for civil disobedience—still haunts us.***** For more information on Mary Dyer and why she chose to die for her principles, please click these links:

Top 10 Things You May Not Know About Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer and the First Amendment, 1660-1791

Thank you, David, for this insightful article, used by written permission of the author. David Macaray, a Los Angeles playwright and author ( It’s Never Been Easy: Essays on Modern Labor ), is a former labor union rep. He can be reached by email.

Published on September 19, 2012 16:39

September 14, 2012

Mary Dyer, a strong-willed woman

There's an article by Christy K Robinson, second in a series on strong-willed women that includes Mary Dyer, at the Rebel Puritan blog. <--- click the link.

There's an article by Christy K Robinson, second in a series on strong-willed women that includes Mary Dyer, at the Rebel Puritan blog. <--- click the link.Author/blogger/friend (not necessarily in that order) Jo Ann Butler releases book two of her trilogy on Herodias Long Hicks Gardner Porter in autumn 2012. "Herod" or "Harwood," as Jo Ann's heroine is known, was a neighbor of the Dyers in Newport, Rhode Island, beginning in the early 1640s.

William Dyer's 1643 memo regarding Herodias

William Dyer's 1643 memo regarding Herodias and her husband John Hick's domestic violence.

“Memo John Hicks of Nuport was bound to ye pease

by ye Govr & Mr Easton in a bond of £10

for beating his wife Harwood Hicks

and prsented [at this] court was ordered to continue

in his bond till ye next C[ourt] upon which his wife

to come & give evidence concerning ye case”William Dyer recorded legal documents about Herodias' first marriage, and did business with and served in government with Herod's husbands. It's highly likely that Herodias and Mary Dyer were friends as well as neighbors, because Herodias, like Mary, protested the Puritan persecution of Quakers. Herodias, holding her unweaned baby, was stripped to the waist in public, and whipped with a knotted lash, as punishment for her support for Quakers and dissidence against the Puritan authority. She was then imprisoned for two weeks in Boston, so you can imagine that her wounds may have become infected and healed badly. However, she lived a long life after that, in Rhode Island.

For more information on Herodias Long, and to order the book, visit the Rebel Puritan website.

Images courtesy of Jo Ann Butler.

Published on September 14, 2012 12:10

September 10, 2012

Knowing people who know people

Lange Eylandt, cropped from a Dutch map.

Lange Eylandt, cropped from a Dutch map.In the 1650s-1670s, Johann Polhemus ministered at the west end,

in Brooklyn, while Mary Dyer spent the winter of

1659-1660 on Shelter Island at the east end. If you enjoy learning about the human experience and culture of the 17th century, take a look at the article I posted on my other history blog, Rooting for Ancestors. It's about the Dutch Reformed minister to Brazil, and the first minister of the first Dutch churches on Long Island, Rev. Johann Theodorus Polhemus.

I doubt that there was a direct connection to William or Mary Dyer, but Polhemus' children and his widow would almost certainly have known or come under the influence of the New York mayor, Major William Dyer, 1640-1688. Yes, the younger William, who obtained his mother's reprieve from death in October 1659. At the risk of placing that earworm song "It's a Small World," in your brain, I urge you to read:

Rev. Johann Polhemus' deadly scrapes <---Click the link

Published on September 10, 2012 11:41

August 31, 2012

What would you like to know?

© Christy K Robinson

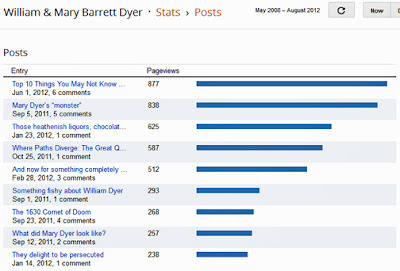

Photo by Eric Pettee. Although this blog was planned for several weeks before it went live, Sept. 1, 2012 begins a new year of posts on the culture, religion, politics, and events surrounding William and Mary Dyer, in mid-17th century Britain and New England.

Photo by Eric Pettee. Although this blog was planned for several weeks before it went live, Sept. 1, 2012 begins a new year of posts on the culture, religion, politics, and events surrounding William and Mary Dyer, in mid-17th century Britain and New England.Overall, the site has received more than 16,300 views in those 366 days. The most popular articles are shown in the graph. As an author, I'd love to believe that all those views were in pursuit of my golden prose, or my spiffy headlines--but hold on a second. If I look at other stats, I learn that at least a third of my visitors didn't come for the articles at all. They came for the images, through Google searches. <sigh>

These are the top search words that terminated at this blog:

Mary Dyer – 200; Baldness cure – 95; Cocoa beans – 56; Paths – 99; Anencephaly – 90

Most-popular articles read on this blog.

Most-popular articles read on this blog. Many of the searches were by Dyer descendants looking for genealogy lines, which isn't the purpose of this blog. But it tells me that there are many thousands of Dyer descendants who would like to either connect their lines with the famous Mary Dyer, or to find her antecedents.

Quakers/Friends visit this blog regularly, which is not surprising, considering the iconic status Mary Dyer holds for that group.

Some readers ended up at this site because they were students working on history papers. In the next few months, I'd like to add student-friendly articles that will help dispel some of the myths that most people, including history instructors, still consider to be truth.

Two very popular articles that had little to do with the Dyers (but covered their culture) were the "leg-bomb" pictures after the Angelina Jolie appearance at the Academy Awards, and the article about various disease remedies of the 17th century, specifically the baldness cure! Most of the hits on the baldness cure came from southeast Asia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Yemen and Oman. Really? Is chicken poo on the scalp a viable option there? And just how follicle-challenged are the southern Asians?

There was a big spike in views of "Mary Dyer's Monster" when the TV drama Private Practice depicted a character bearing an anencephalic baby.

Other searches were definitely creepy: when I posted about the drunkard's cloak and the scold's bridle, there were oodles of hits, some of which led back to porn bondage sites. I have not read the 50 Shades trilogy, but the scold's bridle article peaked when the book sales did. Eww.

I wonder what sort of labels or keywords

I wonder what sort of labels or keywords I need to include, to spark interest from Greenland,

New Guinea, Siberia, and Antarctica?

Six months into writing this blog, I added a map of hits to see the regions the readers came from. The dots are not the total number of hits, but the cities where the hits originated. For instance, if you click on the blog once or repeatedly, it's counted in the total number, but only shows up as one dot on the map.

Are there subjects in this period that you'd like to see covered? Are you an authority on the era who could contribute an article? Please use the comments below to let me know your ideas.

Published on August 31, 2012 22:41

August 20, 2012

How rodents carried out the will of God

Puritans versus the Book of Common Prayer

© Christy K Robinson

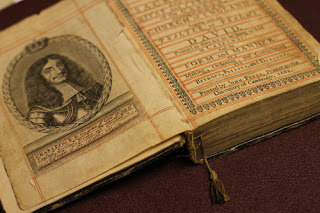

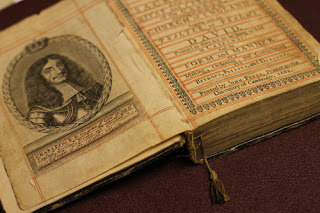

The Book of Common Prayer, 1662 editionThe Book of Common Prayer is a prayer book used by Anglicans since 1549. It contains the liturgy for various worship and sacramental services, including baptism, marriage, funeral, and communion (Eucharist) ceremonies, as well as the scripture readings for the holidays of the church year, and of course, prayers for all occasions. The book has been updated over the centuries and decades, but some phrases, particularly in the wedding service, remain virtually unchanged: “dearly beloved,” “until death do us part,” “ashes to ashes,” and many others.

The Book of Common Prayer, 1662 editionThe Book of Common Prayer is a prayer book used by Anglicans since 1549. It contains the liturgy for various worship and sacramental services, including baptism, marriage, funeral, and communion (Eucharist) ceremonies, as well as the scripture readings for the holidays of the church year, and of course, prayers for all occasions. The book has been updated over the centuries and decades, but some phrases, particularly in the wedding service, remain virtually unchanged: “dearly beloved,” “until death do us part,” “ashes to ashes,” and many others.

Non-conformists like the Puritans (who considered themselves reforming members of the Church of England) resisted or refused use of the BCP on the grounds that the Anglican church had not broken completely with the Roman Catholics at the Reformation. Puritans pointed to the priests’ garment (the surplice), bowing to the communion bread and wine (idolatry because the Eucharist were symbols, not God’s flesh and blood), the use of musical instruments and vocal harmony in services, and the stained glass and religious art, as proof that the Reformation had not put off these distractions for pure and holy worship of God. The Book of Common Prayer was too ritualized for Puritan tastes.

William Laud, Bishop of Bath, Wells, and London in the 1620s, was a “favorite” of King Charles I of England, and although he held some beliefs in common with Puritans and had at one time given them a measure of support or tolerance, he became increasingly authoritarian in his administration of church discipline. In 1633, he was enthroned as Archbishop of Canterbury, and his restrictive and punitive policies in pursuit of uniformity actually spurred the Great Migration of Puritans from England to North America.

The Book of Common Prayer was not a favorite in Massachusetts Bay Colony, a theocracy ruled by Puritan/Congregationalist magistrates and ministers. Nor was it approved in Plymouth, New Haven, or Connecticut Colonies. It wasn’t banned because the Church of England was nominally the state religion, but neither was it used in New England churches in the mid-17th century.

Because Rhode Island colonists were exiled from other colonies for their dissidence to Puritanism, the BCPwas never an issue there. From its inception in 1638, Rhode Island separated civil and ecclesiastical powers and its citizens enjoyed freedom of religion.

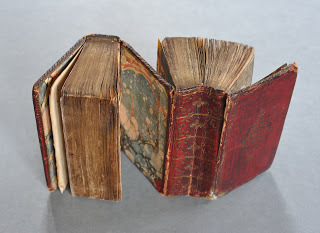

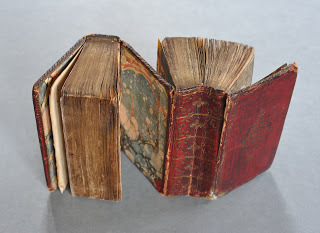

The BCP bound together with

The BCP bound together with

Psalms and the Greek New Testament,

in the same way John Winthrop Jr.'s book was bound.John Winthrop, governor of Massachusetts Bay colony for most of his nineteen years in Boston, was an attorney and magistrate, and one of the investors in the Massachusetts Bay Company. He ordered government on Puritan beliefs and with his business and ministerial partners, created a theocracy. Winthrop kept a journal intended to be a historical record of the founding of the colony. Many of the events he reported were infused with moral conclusions, like this little gem below. Notice that he doesn’t actually criticize the Book of Common Prayer—he only wondersat the strange occurrence. The reader is left to conclude that even vermin were directed by God in their foraging.

December 15, 1640—“About this time there was a thing worthy of observation. Mr. Winthrop the younger, one of the magistrates, having many books in a chamber where there was corn of divers sorts [wheat, barley, rye, Indian corn], had among them one wherein the Greek [New] testament, the psalms, and the common prayer were bound together. He found the common prayereaten with mice, every leaf of it, and not any of the two other touched, nor any other of his books, though there were above a thousand.” ~ Journal of John Winthrop

It seemed clear to John Winthrop that God had made his will plain on the matter of the Book of Common Prayer and what it was good for: mouse chow.

It seemed clear to John Winthrop that God had made his will plain on the matter of the Book of Common Prayer and what it was good for: mouse chow.

On the other hand, the Anglican hand, the mice could be considered highly selective in their choice. The winter stores of grain were not good enough for these critters. No, they knew Jesus' proverb that “It is written: ‘Man shall not live on bread alone, but on every word that comes from the mouth of God.’" Matthew 4:4.

In the English Civil War, Parliamentary forces took Archbishop Laud captive. He was imprisoned for four years and executed in 1645. The BCP was outlawed during the reign of Parliament and the Commonwealth of Oliver Cromwell, and replaced with the Directory for Publique Worship.

When Charles II was restored to the English throne in 1660, the BCP was brought back for use in Anglican churches and revised. The Act of Uniformity was passed on 19 May 1662, and the Book of Common Prayer returned to use in July.

Fast-forward to the 21st century: The Archbishop of York, John Sentamu, tweeted on 20 June 2012, “We are celebrating the 350th anniversary of the Book of Common Prayer today in Parliament. 350 years young and not out!”

© Christy K Robinson

The Book of Common Prayer, 1662 editionThe Book of Common Prayer is a prayer book used by Anglicans since 1549. It contains the liturgy for various worship and sacramental services, including baptism, marriage, funeral, and communion (Eucharist) ceremonies, as well as the scripture readings for the holidays of the church year, and of course, prayers for all occasions. The book has been updated over the centuries and decades, but some phrases, particularly in the wedding service, remain virtually unchanged: “dearly beloved,” “until death do us part,” “ashes to ashes,” and many others.

The Book of Common Prayer, 1662 editionThe Book of Common Prayer is a prayer book used by Anglicans since 1549. It contains the liturgy for various worship and sacramental services, including baptism, marriage, funeral, and communion (Eucharist) ceremonies, as well as the scripture readings for the holidays of the church year, and of course, prayers for all occasions. The book has been updated over the centuries and decades, but some phrases, particularly in the wedding service, remain virtually unchanged: “dearly beloved,” “until death do us part,” “ashes to ashes,” and many others.Non-conformists like the Puritans (who considered themselves reforming members of the Church of England) resisted or refused use of the BCP on the grounds that the Anglican church had not broken completely with the Roman Catholics at the Reformation. Puritans pointed to the priests’ garment (the surplice), bowing to the communion bread and wine (idolatry because the Eucharist were symbols, not God’s flesh and blood), the use of musical instruments and vocal harmony in services, and the stained glass and religious art, as proof that the Reformation had not put off these distractions for pure and holy worship of God. The Book of Common Prayer was too ritualized for Puritan tastes.

William Laud, Bishop of Bath, Wells, and London in the 1620s, was a “favorite” of King Charles I of England, and although he held some beliefs in common with Puritans and had at one time given them a measure of support or tolerance, he became increasingly authoritarian in his administration of church discipline. In 1633, he was enthroned as Archbishop of Canterbury, and his restrictive and punitive policies in pursuit of uniformity actually spurred the Great Migration of Puritans from England to North America.

The Book of Common Prayer was not a favorite in Massachusetts Bay Colony, a theocracy ruled by Puritan/Congregationalist magistrates and ministers. Nor was it approved in Plymouth, New Haven, or Connecticut Colonies. It wasn’t banned because the Church of England was nominally the state religion, but neither was it used in New England churches in the mid-17th century.

Because Rhode Island colonists were exiled from other colonies for their dissidence to Puritanism, the BCPwas never an issue there. From its inception in 1638, Rhode Island separated civil and ecclesiastical powers and its citizens enjoyed freedom of religion.

The BCP bound together with

The BCP bound together with Psalms and the Greek New Testament,

in the same way John Winthrop Jr.'s book was bound.John Winthrop, governor of Massachusetts Bay colony for most of his nineteen years in Boston, was an attorney and magistrate, and one of the investors in the Massachusetts Bay Company. He ordered government on Puritan beliefs and with his business and ministerial partners, created a theocracy. Winthrop kept a journal intended to be a historical record of the founding of the colony. Many of the events he reported were infused with moral conclusions, like this little gem below. Notice that he doesn’t actually criticize the Book of Common Prayer—he only wondersat the strange occurrence. The reader is left to conclude that even vermin were directed by God in their foraging.

December 15, 1640—“About this time there was a thing worthy of observation. Mr. Winthrop the younger, one of the magistrates, having many books in a chamber where there was corn of divers sorts [wheat, barley, rye, Indian corn], had among them one wherein the Greek [New] testament, the psalms, and the common prayer were bound together. He found the common prayereaten with mice, every leaf of it, and not any of the two other touched, nor any other of his books, though there were above a thousand.” ~ Journal of John Winthrop

It seemed clear to John Winthrop that God had made his will plain on the matter of the Book of Common Prayer and what it was good for: mouse chow.

It seemed clear to John Winthrop that God had made his will plain on the matter of the Book of Common Prayer and what it was good for: mouse chow.On the other hand, the Anglican hand, the mice could be considered highly selective in their choice. The winter stores of grain were not good enough for these critters. No, they knew Jesus' proverb that “It is written: ‘Man shall not live on bread alone, but on every word that comes from the mouth of God.’" Matthew 4:4.

In the English Civil War, Parliamentary forces took Archbishop Laud captive. He was imprisoned for four years and executed in 1645. The BCP was outlawed during the reign of Parliament and the Commonwealth of Oliver Cromwell, and replaced with the Directory for Publique Worship.

When Charles II was restored to the English throne in 1660, the BCP was brought back for use in Anglican churches and revised. The Act of Uniformity was passed on 19 May 1662, and the Book of Common Prayer returned to use in July.

Fast-forward to the 21st century: The Archbishop of York, John Sentamu, tweeted on 20 June 2012, “We are celebrating the 350th anniversary of the Book of Common Prayer today in Parliament. 350 years young and not out!”

Published on August 20, 2012 22:42

July 3, 2012

A peek at William Dyer's handwriting

© Christy K Robinson

William Dyer's 27 May 1660 letter to Massachusetts General Court

William Dyer's 27 May 1660 letter to Massachusetts General Court Image courtesy of Massachusetts Archives

Honored Sirs,It is no little grief of mind, and sadness of hart that I am necessitated to be so bould as to supplicate your Honored self with the Honorable Assembly of your General Court to extend your mercy & favor once again to me & my children. Little did I dream that ever I should have had occasion to petition you ina matter of this nature, but so it is that through the divine providence and your benignity my sonn obtained so much pitty & mercy att your hands as to enjoy the life of his mother. Now my supplication to your Honors is to begg affectionately, the life of my dear wife, 'tis true I have not seen her above this half yeare & therefore cannot tell how in the frame of her spiritt she was moved thus againe to runn so great a Hazard to herself, and perplexity to me & mine & all her friends and well wishers. So itt is from Shelter Island about by Pequid Narragansett & to the towne of Providence…

This is a fragment of a complete letter by William Dyer, dated 27 August 1660, written from Portsmouth, Rhode Island. It was an attempt to free his wife, Mary Barrett Dyer, from prison and her death sentence. But Mary had intentionally defied her death-penalty Massachusetts banishment order, and sailed from Shelter Island (northeastern end of Long Island) into the Narragansett Bay, perhaps gliding past her own home on the western shore of Rhode Island north of Newport. She kept going by water to Providence, and then, in a reversal of her and William’s first exile from Massachusetts in 1638, she walked to Boston.

She was arrested, imprisoned, tried, and sentenced to death, which was carried out on 1 June 1660.

A close inspection of the high-resolution image shows faded black ink on linen-textured paper that browned over the intervening 350 years. The left edge is stained by glue or book-binding. The right edge is understandably frayed and flaked. William’s handwriting here is consistent with other documents he wrote, with a fine-tipped quill and artistic flourishes. There are a few ink blots, particularly on loops, and the double t's (lett, quiett, att) are heavier than other letters, where he may have refreshed his quill.

The language, though tender when he refers to Mary, is otherwise courtly and professional (honored sirs, render you Love and Honor), as one would assume from a former clerk, secretary of state, and attorney general. He was no friend or colleague of Governor Endecott or Deputy Governor Bellingham, but he tried to appeal to their and the jury’s emotions about putting a beloved wife and mother to death, a woman who must be suffering from delusions.

What do you think William Dyer’s handwriting says about his personality or frame of mind? How does it compare with his wife’s handwriting?

Published on July 03, 2012 23:50

June 27, 2012

Grandparents-in-law: the Quaker connection

© Christy K. Robinson

Petition of imprisoned Quakers to be released from Boston's House of Correction, 24 Dec 1660.

Petition of imprisoned Quakers to be released from Boston's House of Correction, 24 Dec 1660.Photocopy of a holograph in Massachusetts Archives. (transcript follows)**** general court where as it is reported yt ye prison doors are set upon ***** that wee may have our liberty of this in spoken both in towenand country in so much yt one of our relations which came to see us questioned****** shee should find us at the prison: as touching our liberties it is yt wee ***** thing if it be granted wee are ***** to accept it yt wee may go to our**** children from whch Margaret Smith hath been detained about ten monthesand her husband three monthes Mary Traske about 8 monthes Robert Harper and his wif now about two monthesand whether yeat will [hurt? hand?] may our libertys wee desire to have an answerfrom you from ye house of correction in boston ye 24 of ye 10th mo 1660 Robert Harper John Smith Deborah Harper Margaret Smith[possibly Wenlock Christison]

[carried by?] William Salter [jailer]Ben Gwilln?

______________________

In the late 1650s, Robert Harper of Sandwich in Plymouth Colony, had been heavily fined as much as £44 over time, for attending Quaker meetings and repeatedly refusing to take the fidelity oath (taking an oath was contrary to Jesus’ command in Matthew 5:33-35 not to swear at all.); he was whipped 15 stripes with a 3-knot gut scourge (that's 45 wounds); he and his wife Deborah Perry Harper were set in Boston prison with no food unless an outsider paid for it, hard labor, and with no heat during winter in the Little Ice Age.

What earned them prison? In October 1660, they went to Salem to visit other Quakers in prison—the same thing that Mary Dyer had done several times and was hanged for the previous June 1, 1660. One of their number, Mary Southwick Trask, had Quaker family in Salem who had suffered banishment, fines, prison, and an attempt to sell her brother and sister as slaves. The entire group knew exactly what might happen to them, and they purposely set out to defy “the bloody law.” They committed civil disobedience in the cause of religious freedom.

The Harpers were no strangers to heavy fines (which seemed to be repeated several times a year, probably as a lucrative business for the magistrates) or arrests. The Boston laws passed by Governor John Endecott and his assistants stated that Quakers were to be whipped at their entrance to the prison. It was later amended to whipping them several times a week. The jailer was sometimes told to whip the prisoners harder, while Deputy Governor Bellingham stood by to be sure the scourge was properly applied. The following points are incidences of fines, whippings, and incarceration of Robert Harper:

· 1 June 1658 – Robert appeared before the court for failure to take the “oath of fidelitie,” and was fined £10 at Plymouth. · 2 Oct 1658 – Robert Harper was fined £5 for refusing to take the “oath of fidelitie,” along with twelve others of Sandwich, and was fined £5.· 7 Jun 1659 – Robert appeared before the court for failure to take the “oath of fidelitie,” and fined £5 at Plymouth.· 6 Oct 1659 – Robert appeared before the court for failure to take the “oath of fidelitie,” and fined £5 at Plymouth.· 8 or 13 June 1660- Robert Harper was fined fined £5 for refusing to take the “oath of fidelitie.” This fine was imposed by the court in regards to the 7 Mar 1660 appearance at Plymouth.· 2 Oct 1660 – Robert was convicted for refusing to take the “oath of fidelitie,” at the General Court in Plymouth; fined £6 at Plymouth.· 2 Oct 1660 – Robert and Deborah Harper were fined £4, “for being att Quakers meetings.”· 13 Oct 1660 – Robert and Deborah Harper and others visit Quaker friends in Salem’s jail, arrested and committed to Boston’s House of Correction. They petitioned for release on 24 Dec 1660, but no record is noted of their disposition at that time.· 24 Mar 1661 – Robert, who must have been recently released from Boston prison, “stood under the scaffold and caught in his arms the body of his friend William Leddra, the martyr preacher,” when Leddra’s hanging rope was cut. For this, he and his wife were banished from Massachusetts Bay Colony (different jurisdiction from Plymouth Colony). · 1 Mar 1664 – Robert Harper appeared before the court for “intollorable insolent disturbance” and was ordered to be publicly whipped at Plymouth.

Bishop, in New England Judged by the Spirit of the Lord, wrote: “Several of Salem friends ye committed, and have continued them long prisoners at Boston, as Mary [Southwick] Trask, John Smith, Margaret Smith, Edward Wharton, and others. Robert Harper, of Sandwich, and Deborah ye committed likewise, and these were in your prison, the 13th of the 10th month [13 Dec], 1660. Several ye banished upon pain of death, as Wenlock Christison, and William King of Salem, and Martha Standley, a maid belonging to England, and Mary Write [Wright], of Oyster Bay, in Rhode Island, who gave her testimony against you for your cruelty in putting Mary Dyer to death, whose blood ye also thirst after because of it.”

Mary Dyer was reprieved from hanging in October 1659, and taken away to Newport. But a week to ten days later, she showed up in Sandwich, Plymouth Colony, for a Thomas Greenfield was sentenced to pay for her lodging in prison and her transportation back to Rhode Island. Surely she would have met with the Sandwich Quakers, of which Robert and Deborah Harper were pioneer members. Mary purposely returned to Boston in May 1660, was retried and condemned for disobeying her banishment, and hanged on June 1, 1660.

When were the Quakers of the petition released from Boston’s House of Correction? I’m still looking for the rest of the group, but Wharton was kept in the freezing cold prison all winter. Leddra likewise, and he was hanged on March 24, 1661. It seems that the group were released sometime between Christmas, when they made their petition, and early February; that they went home to Sandwich briefly, and came back to Boston to defy Governor Endecott and Deputy Governor Bellingham at Leddra's execution.

Robert and Deborah Harper had two young children at the time of their Quaker activism and persecution. Mary Harper was born 25 Dec 1655, and Experience was born Nov 1657. Possibly the little girls were kept by their Perry grandparents. They grew up to marry and bear a tribe of Quakers. Deborah Perry Harper, their mother, died shortly after giving birth to a baby in December 1665. Robert married six months later, in 1666, and had more children by Prudence Butler.

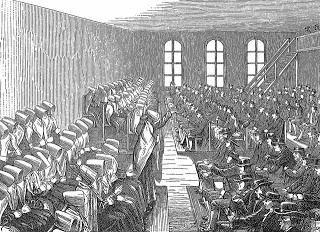

A Quaker meeting, undated art

A Quaker meeting, undated artExperience Harper married Joseph Hull in 1676 (the year William Dyer died in Newport). Their first son, born 1677, was Tristram Hull, who married William and Mary Dyer’sgranddaughter (through son Charles Dyer), Elizabeth Dyer in 1699. Thus we see that 39 years after Mary Dyer’s death in Boston, which Robert and Deborah Harper probably attended and certainly protested, the Dyers and Harpers united their family lines. They became grandparents-in-law. Robert Harper, age 74, was still alive in 1704. So he alone of the grandparents was still alive, and knew the deep connection between the families. Elizabeth and Tristram’s first four children had been born by 1704, and the firstborn was named Mary.

Other than an interesting historical factoid, perhaps the lesson we can take away, 300 years later, is to be kind and supportive of the people in our circles. You never know who your grandchildren will “hook up” with and combine genes!

William & Mary (Barrett) Dyer Robert & Deborah (Perry) HarperCharles and Mary (Lippett) Dyer Joseph & Experience (Harper) Hull Elizabeth Dyer.................................Tristram Hull

Published on June 27, 2012 01:44

June 17, 2012

The Jewish settlement of Newport in 1658: Fact or Fiction?

And you thought this blog was about Mary and William Dyer, and Puritans and Quakers! So it is. But it’s also about their culture, politics, religion, natural history, neighbors, influences, and everything around them. Many Portuguese Jewish refugees fleeing the Inquisition went first to the Netherlands or Brazil, then to New Amsterdam (now called New York), where they had a measure of religious freedom under the Dutch Reformed Church; and others went (via Brazil and Barbados) to Newport, Rhode Island, because of the Rhode Island charters granting religious freedom--and for Newport's commercial trading opportunities (sugar, rum, African slaves). If the Jewish refugees and traders came to Newport in 1658, it’s very likely that they crossed paths or did business with William Dyer, who died about 1676.

The Jewish settlement of Newport in 1658: Fact or Fiction?

Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, finished in 1763.

Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, finished in 1763.©2012 by Patricia O’Sullivan (used by permission)

When fellow author and antiquarian, Christy K. Robinson, asked me to write a guest blog about the Jewish community of Newport, Rhode Island, in the 17th century, I imagined writing the first draft in an hour. However, I got stuck immediately because I couldn’t pin down a primary source document for the establishment of the Newport Jewish community in 1658. It turns out this settlement date hinges on a mysterious letter found in an attic trunk in the 19th century.

A more detailed series on the controversy surrounding this date will appear in my blog, legendofthedead.blogspot.comin the coming weeks. What follows is a summary of my research on the 1658 Jewish settlement date.

The Jewish settlement of Newport in 1658 is often stated as common knowledge by trusted institutions and historians. However, the 1658 settlement was not common knowledge until the twenty-first century. In fact, up until 1853, no one wrote about a Jewish settlement in Newport almost two hundred years earlier. Not even Henry Wadsworth Longfellow who published a poem about the Jews of Newport on the two-hundredth anniversary of the 1658 settlement date mentioned it. Up until 1853, Jewish settlement in Newport was difficult to pin down. There are records from the Rhode Island General Assembly from 1684 and 1688 recording the presence of Jews in the colony. But there was not an actual Jewish community until the mid-eighteenth century when the Jews of Newport built a synagogue.

So what happened in 1853 that pushed the ‘common knowledge’ settlement date back one hundred years?

It began with a death, that of Hannah Hull of Connecticut in 1839. As her nephew and executor, Isaac Gould, sifted through her effects, he found an old, coverless trunk in her attic. Isaac’s son, Nathan Gould, claimed years later his father found in that trunk a letter concerning the Freemasons of Newport. According to Nathan Gould, the letter, compromised by time and weather, read:“Ths ye (day and month obliterated) 1656 or 8 (not certain which, as the place was stained and broken: the three first figures were plain) Wee mett att y House of Mordecai Campunnall and affter Synagog Wee gave Abm Moses the degrees of Masonrie.”

Memorial stone at entrance to Newport's Jewish cemetery.

Memorial stone at entrance to Newport's Jewish cemetery. In 1853, another Gould of Connecticut, James L. Gould, (whose relationship to Isaac and Nathan Gould is unclear) wrote a history of the Freemasons of Newport, citing the letter found in the trunk as evidence the masons were active in Newport in 1658.

Masonic leaders in Rhode Island and Massachusetts dismissed the letter as a fabrication after pressing the Goulds for further evidence of their claims. None of the Goulds could produce the original letter, claiming it had been misplaced.

However, a local historian, Edward Peters, cited the discredited letter in his History of Rhode Island published in 1853. Almost twenty years later, another historian, Charles P. Daly, cited Peterson’s History of Rhode Island when he claimed in “The Settlement of the Jews in North America” Jews came to Newport in 1658. In 1897 Max J. Kohler cited both Peterson and James Gould when he presented the 1658 settlement date as fact in his book, The Jews of Newport.

In the next one hundred years various historians accepted the 1658 settlement date, disputed it, or ignored it as not worthy of a scholarly discussion. Accounts of the 1658 settlement vacillated widely between fabrication, fact, and unsubstantiated tradition. However, most histories of the Jews in North America and of Newport published since 2000 present the 1658 settlement date as a longstanding fact. It has now become tradition to date the settlement of the Jews in Newport at 1658.

It is disturbing how discredited historical evidence has been repeated enough times to be valued as a tradition. It suggests that some historians are either sloppy in their research or so eager to write history in a particular way they are willing to overlook shoddy evidence.

The Newport Jewish community was enormously important in the history of the United States. Men like Aaron Lopez and Jacob Rodrigues Riviera spent their fortunes aiding the Patriot cause while Isaac Touro steadfastly supported Britain and thus saved Newport’s synagogue for posterity. And Moses Seixas’s correspondence with George Washington has been enshrined in our national consciousness as one of the strongest statements of religious freedom made by our Founding Fathers. (For more information, click the highlighted links.)

However, Newport’s Jewish community did not achieve this greatness until the middle of the eighteenth century. And following the British occupation of Newport from 1776-1779, the Newport Jewish community never recovered its former numbers. By 1812 it was a memory, not a congregation. When Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote his famous poem, “The Jewish Cemetery at Newport”, there were but a handful of living Jews in that city. The Newport Jewish community of lore comprised of a single generation. What they achieved is not diminished by their short tenure. Indeed, the fact they accomplished so much in a 35-40 year period is all the more impressive.

Facts matter. We cannot make something true by wishing it so. In addition, we need to ask ourselves: Why do we want something to be so? Does the date of Jewish settlement in Newport, be it 1658 or 1748, matter when we consider the importance of Jews in the history of this nation?

The promise of America is that it is a country for everyone no matter when they arrived or what their religion is. If that is not the reality, the problem is not when a people settled here but a disconnect between what America promises and what she is.

*****

Patricia O’Sullivan is author of

Hope of Israel

,* a novel about the readmission of the Jews to England, and an instructor of Religion and Ethics at the University of Mississippi.

Patricia O’Sullivan is author of

Hope of Israel

,* a novel about the readmission of the Jews to England, and an instructor of Religion and Ethics at the University of Mississippi. Thank you, Patti, for sharing your research, and enlarging our knowledge of what life was like in the 17th century—and how the same issues are relevant today. I’m currently reading and enjoying Hope of Israel, and look forward to the release of your next book, Legend of the Dead. (I heard its subject is connected to the Newport Jewish community!)

*Hope of Israelsynopsis: In 1656, a small community of Spanish Catholic merchants lived in London bound by a sacred secret: they were Portuguese Jews. This is the story of one of them, Domingo de Lacerda, who learns early on that survival in seventeenth-century Europe requires both deceit and conformity. But then he meets Lucy, who has secrets of her own and who challenges Domingo to question everything he has been taught to value. The political and spiritual conflicts that characterized the Iberian Inquisition, the English Civil War, and the English Interregnum provide a backdrop against which Domingo must choose between his obligation to the Jewish community that protects him and the Catholic woman who loves him.

Published on June 17, 2012 19:39