Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 17

July 1, 2013

Shelter Island: Mary Dyer's last six months

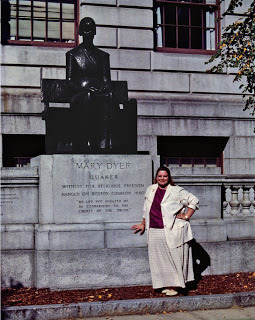

MARY DYER AND SHELTER ISLAND

© 2013 Mac Griswold This article excerpted with author's permission, from Mac Griswold’s book, The Manor: Three Centuries of a Slave Plantation on Long Island, available at Amazon.com and bookstores.

In 1652, the dashing Nathaniel Sylvester, son of an English merchant family, sailed north from Barbados, where his family owned sugar plantations that depended on the labor of hundreds of Africans. With him came his teenaged bride, Grizzell Brinley, daughter of Charles I’s court auditor, Thomas Brinley. After a dramatic shipwreck, the newlyweds landed on Shelter Island, where a large and comfortable house (built previously by Nathaniel and his servants) stood ready to receive the young couple. Nathaniel and his brother Constant and two other Barbadian planters, Thomas Middleton and Thomas Rous, had bought the island from Stephen Goodyear, the deputy governor of New Haven Colony, who had bought it as a speculative venture in 1651 from the estate of the Earl of Stirling, its first English owner, for 1,600 pounds of the unrefined brown sugar known as muscovado.

Mary Dyer was as spiritually driven and intellectually active as her friend and mentor, Anne Hutchinson. Her contemporaries repeatedly described her as “comely,” an adjective that then connoted feminine beauty and modesty matched by moral grace. Winthrop, for example, recalled her as “a very proper and comely young woman,” as if to underscore his astonishment that this paragon could commit the transgressions for which she had been banished. Gerard Croese, a Dutch minister, later praised Dyer as a “person of no mean extract and parentage, of an estate pretty plentiful, of a comely stature and countenance, of a piercing knowledge in many things, of a wonderful sweet and pleasant discourse, so fit for great affairs, that she wanted nothing that was manly, except only the name and the sex.”

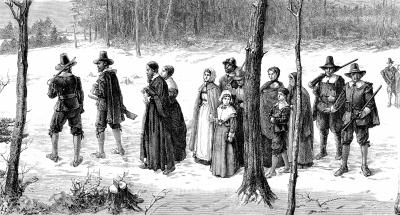

With the rest of the Boston outcasts, Dyer moved to Rhode Island and lived there for a decade. In the early 1650s, shortly after the birth of a sixth child, she left her husband, William Dyer, and their children for England. When she returned to Boston in February 1657 as a Quaker, the authorities arrested her. William secured her release on payment of a £100 bond and the promise that she would not return to Massachusetts, on pain of death. But Dyer soon reappeared in Boston to hurl herself against the colony’s 1658 capital law. Quickly imprisoned, she was sentenced to be hanged with two younger Friends, Marmaduke Stevenson and William Robinson. Quakers from all over New England converged on Boston; one woman brought winding sheets for the martyrs’ corpses.

On October 27, armed soldiers surrounded the three as they walked a mile to the scaffold. They went “hand in hand, all three of them, as to a Wedding Day,” Dyer in the middle. Onlookers said that their faces shone with joy. By official command, military drums rolled incessantly, so that only those closest to the gallows could hear the heretics’ last words. Robinson and Stevenson rejoiced that they would be at rest with the Lord; Dyer spoke of the “sweet incomings and refreshings of the Spirit.” Robinson stepped up to the platform; the hangman adjusted the noose, and after he pulled the ladder away, Robinson’s body jerked, writhed, and was still. Then came Stevenson’s turn. Having watched her companions perish, Dyer ascended. Her face was covered with a handkerchief, her arms and feet bound. Theatrically, improbably, a long pause followed. The hangman took off Dyer’s blindfold. Unmoving, and seemingly unmoved, she continued to stand with the halter around her neck. She had to be forcibly escorted from the platform, even after hearing that the magistrates had reprieved her. Unbeknownst to Dyer, they had granted this pardon some days before but kept the news secret in order to pull off the grisly charade. Perhaps the magistrates feared that hanging a woman would increase sympathy for the Quakers; perhaps they wished to look magnanimous. Dyer was banished again, set on a horse, and escorted to the Rhode Island border. Another return to Massachusetts, she was informed, would result in her execution. She made her way home, but she didn’t stay there for long.

Shelter Island is enclosed by the arms

Shelter Island is enclosed by the armsof Long Island. It's south of

Connecticut and SE of Rhode Island.

[In November 1659, Mary Dyer sailed to the eastern tip of Long Island, which encloses a smaller island called Shelter Island. Shelter Island was privately owned by Nathaniel Sylvester and his partners in Barbados. Sylvester had sheltered several Quaker missionaries well-known to Mary Dyer. When Mary arrived, Nathaniel and Grizzell Sylvester (he was 49, she was 23) had two small children, a farm that supplied food and other products for the Barbados plantation, and several Quaker guests, including Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick.]

Shortly before the Quaker missionary John Taylor left Shelter Island in late 1659, Mary Dyer arrived. Taylor found Dyer, then in her late forties, to be still “a very Comely Woman,” as well as “a Grave Matron” who “ever shined in the Image of God,” and the two led several meetings together. By the end of the following April she decided to return to Boston, to burn as a candle for the Lord, traveling north through Providence to avoid visiting her husband and children.

Sylvestor Manor and inlet. This house was built 70 years after

Sylvestor Manor and inlet. This house was built 70 years after Mary Dyer's winter on Shelter Island.

The six months or so that Dyer spent with the Sylvesters may have been the happiest, most dedicated, least fractured time of her life. Her actions embodied her faith; all the rest of life’s concerns had burned away.

Perhaps Nathaniel and Grizzell Sylvester helped her into a boat, prayed with her and waved goodbye, then watched her disappear over the rim of the bay. They could have had no doubt that she was voluntarily, knowingly, headed for death. By late May she was back in Boston’s jail. On June 1, 1660, Dyer mounted the scaffold. As her body dangled from the noose, her skirt quivered in the breeze. What a bystander scoffingly said at that sight would eventually stand as Mary Dyer’s truth: “She did hang as a Flag for them to take example by.”

*************

Mac Griswold is a cultural landscape historian and the author of Washington’s Gardens at Mount Vernon and The Golden Age of American Gardens. She has won a Guggenheim Fellowship and has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Travel + Leisure. She lives in Sag Harbor, New York.

Mac Griswold is a cultural landscape historian and the author of Washington’s Gardens at Mount Vernon and The Golden Age of American Gardens. She has won a Guggenheim Fellowship and has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Travel + Leisure. She lives in Sag Harbor, New York. Video of Shelter Island Farm, from BBC World News

See also, Mary Dyer at Shelter Island: She ever shined in the image of God by Johan Winsser

New York Times article on Sylvester Manor

Published on July 01, 2013 00:32

June 19, 2013

Zerubbabel Endecott, 17th-century physician and pharmacist

Remedies guaranteed to cure your hypochondria!

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

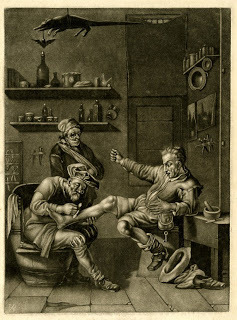

Print by Jan van der Bruggen, 1665-1690.

Interior of a surgery with a surgeon seated

on a barrel and operating on a peasant man,

an old woman standing with her arm in a sling,

several shelves on walls in background,

a stuffed animal hanging from ceiling. Mezzotint. Be very glad for modern scientific research, sterility, and effective and measured anesthesia, none of which were known in 17th-century Europe or North America. You wouldn't want your childbirth pain treated with cat's blood and human milk, curing your nosebleed with hog's dung, or your seizures treated with Salt of Man's Skull (exactly as it sounds).

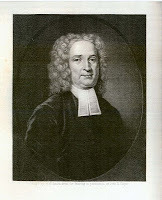

Zerubbabel Endecott, born about 1635 in Salem, was the second son of Massachusetts Bay Governor John Endecott, the father being what I call the “Hammer of the Quakers.” The governor was the man who sentenced Quaker missionaries to severe whippings, starvation and exposure, imprisonment, and death. He sentenced Mary Dyer to death by hanging for her civil disobedience.

When he was about 18 years of age, Zerubbabel was accused of raping his mother’s indentured lace-maker. The servant girl, who gave birth in 1653-54, continued to accuse Zerubbabel even after her trial for slander, two serious public whippings, being released from her indenture early as a hush-reward, being hurriedly married off to another servant who endured a whipping he didn't deserve, and told to leave. In other words, Gov. Endecott was not having his first grandchild born illegitimately, and of rape, to a mere servant girl, and he was not chaining his son to her for life, as the courts usually did after publicly whipping both fornicating parties.

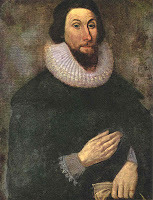

(The governor himself had fathered an illegitimate son in England in the 1610s or 1620s, but wrote at least one letter saying that although he was providing some money for his upkeep, the boy was not to be sent to New England under any circumstances.) Gov. John Endecott in the 1650s.

Gov. John Endecott in the 1650s.

He may be wearing the lace made

by his wife's abused servant.

After his shameful conduct for which he was never tried, Zerub—as I shall abbreviate his name—was immediately wedded, about eight years before most young men would marry, to a woman named Mary, and then he was not heard of for a few years. Zerub probably shipped away to England for medical education. The custom was to read medicine in the home of a physician and go with him on patient rounds. In any case, he was back in Massachusetts by 1659, for he and his brother John were fined for drunkenness, another blow to the pride of his father, the governor.

Zerub and Mary had ten children during their 23 years of marriage. He was made a freeman in 1665 (the year his father died). He was a winning defendant in a trespass suit by a Mr. Nurse (of the witchcraft name) in June 1683, Zerub having logged valuable timber for firewood off the land in question; several Salemites testified that he had logged within his own boundaries. Five months later, he made his will, which indicates a life-threatening injury or illness, and two months after that he died.

Zerub’s will, made before his death at age 49 in the winter of 1684, specified cash bequests of £50 each to his daughters Mary, Sarah, Elisabeth, Hanna, and Mehetabel; farm properties to his sons; to his son John, also a physician, he left “all my Instruments and books of phisicke and chirurgery.” The inventory of medical instruments showed “a case of lances, 2 Rasors, a box of Instruments, a saw with six Instruments for a Chirurgion, a curb bit.”

During Zerub’s medical practice, he took notes and in 1677 wrote a short book, entitled Synopsis Medicinae or a Compendium of Galenical and Chymical Physick Showing the Art of Healing according to the Precepts of Galen & Paracelsus Fitted universally to the whole Art of Healing. It contains directions for mixing and applying medicines for the cure of disease or healing from surgery. The manuscript bears the byline “Zorubbabel Endecott.” You can find the booklet in several formats, HERE.

The following recipes are a few of the concoctions Dr. Zerubbabel Endecott preferred for his treatment of Salem patients between 1659 and 1684. Interesting ingredients, considering the witchcraft craze less than 10 years later.

For ye Colic or Flux in ye Bellythe powder of Wolves guts the powder of Boars Stones [testicles?]oil of Wormwood a drop or 2 into the Navel 3 drops of oil of Fennel & 2 drops of oil of mints in Conserve of Roses or Conserve of single mallows, if ye Pain be extreme Use it again, & if need Require apply something hot to the belly

For Vomiting & Looseness in Men Women & ChildrenTake an Egg break a Little hole in one end of it & put out ye white then put in about 1/2 spoonful of bay salt then fill up the egg with strong Rum or spirits of wine & set it in hot ashes & Let it boil till ye egg be dry then take it & eat it fasting & fast an hour after it or drink a Little distilled wafers of mint & fennel which waters mixed together & drank will help most ordinary Cases

For a Person that is Distracted If it be a Woman No cat's blood!

No cat's blood!

"Take a he-Cat & Cut off one of his Ears

or a piece of it & Let it bleed..." Take milk of a Nurse that gives suck to a male Child & also take a he-Cat & Cut off one of his Ears or a piece of it & Let it bleed into the milk & then Let the sick woman Drink it, do this three Times

For the ShinglesTake house leek, Cats blood, and Cream mixed together & oint the place warm or take the moss that groweth in a well & Cats blood mixed & so apply it warm to the place where shingles be.

For a Cancer in a Womans BreastA woman at Casko bay had a Cancer in her breast which after much means used in Vain they applied strong beer to it with Double Cloths which it drank in Very Greedily & was something eased afterwards beer failing they Used Rum in Like manner which seem to Lull it asleep afterwards they put Arsenic into it and dressing it twice a day it was Perfectly whole in the mean time her Kind husband by Sucking drew her breast with ye Loss of his Fore teeth without any farther hurt. Re New Englands Experiences

For Sharp & Difficult Travail in Women with ChildTake a Lock of Virgins hair on any Part of ye head, of half the Age of ye woman in travail. Cut it very small to fine Powder then take 12 Ants Eggs dried in an oven after ye bread is drawn or otherwise make them dry & make them to powder with the hair, give this with a quarter of a pint of Red Cows milk or for want of it give it in strong ale wort.

For ye Tooth AcheTake a Little Piece of opium as big as a great pins head & put it into the hollow place of the Aching Tooth & it will give present Ease, often tried by me upon many People & never failed. Zerobabel Endecott.

Falling Sickness (epilepsy or seizure) In Children. has of the dung of a black Cow 3i. given to a newborn Infant, doth not only preserve from the Epilepsia, but also cure it. In those of ripe Age. The livers of 40 water-Frogs brought into a powder, and given at five times (in Spirit of Rosemary or Lavender) morning and evening, will cure, the sick not eating nor drinking two hours before nor after it. — Compendium of Physick (Salmon), London, 1671. Salt of Mans Skull. The skull of a dead man, calcine it, and extract the Salts as that of Tartar. It is a real cure for the Falling-sickness. Vertigo, Lethargy, Numbness, and all capital diseases, in which it is a wonderful prevalent.— Compendium of Physick (Salmon), London, 1671.

To stop bleeding of the noseIf the flux be violent, open a vein on the same side, and cause the sick to smell to a dried Toad, or Spiders tied up in a rag; the fumes of Horns and Hair is very good, and the powder of Toads to be blowed up the Nose; in extremity, put teats made of Swines-dung up the nostrils. — Compendium of Physick (Salmon), London, 1671.Hog’s Dung is also used by the Country People to stop Bleeding at the Nose; by being externally applied cold to the Nostrils. –English Dispensatory(Quincy), London, 1742.

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

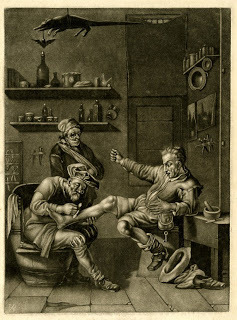

Print by Jan van der Bruggen, 1665-1690.

Interior of a surgery with a surgeon seated

on a barrel and operating on a peasant man,

an old woman standing with her arm in a sling,

several shelves on walls in background,

a stuffed animal hanging from ceiling. Mezzotint. Be very glad for modern scientific research, sterility, and effective and measured anesthesia, none of which were known in 17th-century Europe or North America. You wouldn't want your childbirth pain treated with cat's blood and human milk, curing your nosebleed with hog's dung, or your seizures treated with Salt of Man's Skull (exactly as it sounds).

Zerubbabel Endecott, born about 1635 in Salem, was the second son of Massachusetts Bay Governor John Endecott, the father being what I call the “Hammer of the Quakers.” The governor was the man who sentenced Quaker missionaries to severe whippings, starvation and exposure, imprisonment, and death. He sentenced Mary Dyer to death by hanging for her civil disobedience.

When he was about 18 years of age, Zerubbabel was accused of raping his mother’s indentured lace-maker. The servant girl, who gave birth in 1653-54, continued to accuse Zerubbabel even after her trial for slander, two serious public whippings, being released from her indenture early as a hush-reward, being hurriedly married off to another servant who endured a whipping he didn't deserve, and told to leave. In other words, Gov. Endecott was not having his first grandchild born illegitimately, and of rape, to a mere servant girl, and he was not chaining his son to her for life, as the courts usually did after publicly whipping both fornicating parties.

(The governor himself had fathered an illegitimate son in England in the 1610s or 1620s, but wrote at least one letter saying that although he was providing some money for his upkeep, the boy was not to be sent to New England under any circumstances.)

Gov. John Endecott in the 1650s.

Gov. John Endecott in the 1650s.He may be wearing the lace made

by his wife's abused servant.

After his shameful conduct for which he was never tried, Zerub—as I shall abbreviate his name—was immediately wedded, about eight years before most young men would marry, to a woman named Mary, and then he was not heard of for a few years. Zerub probably shipped away to England for medical education. The custom was to read medicine in the home of a physician and go with him on patient rounds. In any case, he was back in Massachusetts by 1659, for he and his brother John were fined for drunkenness, another blow to the pride of his father, the governor.

Zerub and Mary had ten children during their 23 years of marriage. He was made a freeman in 1665 (the year his father died). He was a winning defendant in a trespass suit by a Mr. Nurse (of the witchcraft name) in June 1683, Zerub having logged valuable timber for firewood off the land in question; several Salemites testified that he had logged within his own boundaries. Five months later, he made his will, which indicates a life-threatening injury or illness, and two months after that he died.

Zerub’s will, made before his death at age 49 in the winter of 1684, specified cash bequests of £50 each to his daughters Mary, Sarah, Elisabeth, Hanna, and Mehetabel; farm properties to his sons; to his son John, also a physician, he left “all my Instruments and books of phisicke and chirurgery.” The inventory of medical instruments showed “a case of lances, 2 Rasors, a box of Instruments, a saw with six Instruments for a Chirurgion, a curb bit.”

During Zerub’s medical practice, he took notes and in 1677 wrote a short book, entitled Synopsis Medicinae or a Compendium of Galenical and Chymical Physick Showing the Art of Healing according to the Precepts of Galen & Paracelsus Fitted universally to the whole Art of Healing. It contains directions for mixing and applying medicines for the cure of disease or healing from surgery. The manuscript bears the byline “Zorubbabel Endecott.” You can find the booklet in several formats, HERE.

The following recipes are a few of the concoctions Dr. Zerubbabel Endecott preferred for his treatment of Salem patients between 1659 and 1684. Interesting ingredients, considering the witchcraft craze less than 10 years later.

For ye Colic or Flux in ye Bellythe powder of Wolves guts the powder of Boars Stones [testicles?]oil of Wormwood a drop or 2 into the Navel 3 drops of oil of Fennel & 2 drops of oil of mints in Conserve of Roses or Conserve of single mallows, if ye Pain be extreme Use it again, & if need Require apply something hot to the belly

For Vomiting & Looseness in Men Women & ChildrenTake an Egg break a Little hole in one end of it & put out ye white then put in about 1/2 spoonful of bay salt then fill up the egg with strong Rum or spirits of wine & set it in hot ashes & Let it boil till ye egg be dry then take it & eat it fasting & fast an hour after it or drink a Little distilled wafers of mint & fennel which waters mixed together & drank will help most ordinary Cases

For a Person that is Distracted If it be a Woman

No cat's blood!

No cat's blood!

"Take a he-Cat & Cut off one of his Ears

or a piece of it & Let it bleed..." Take milk of a Nurse that gives suck to a male Child & also take a he-Cat & Cut off one of his Ears or a piece of it & Let it bleed into the milk & then Let the sick woman Drink it, do this three Times

For the ShinglesTake house leek, Cats blood, and Cream mixed together & oint the place warm or take the moss that groweth in a well & Cats blood mixed & so apply it warm to the place where shingles be.

For a Cancer in a Womans BreastA woman at Casko bay had a Cancer in her breast which after much means used in Vain they applied strong beer to it with Double Cloths which it drank in Very Greedily & was something eased afterwards beer failing they Used Rum in Like manner which seem to Lull it asleep afterwards they put Arsenic into it and dressing it twice a day it was Perfectly whole in the mean time her Kind husband by Sucking drew her breast with ye Loss of his Fore teeth without any farther hurt. Re New Englands Experiences

For Sharp & Difficult Travail in Women with ChildTake a Lock of Virgins hair on any Part of ye head, of half the Age of ye woman in travail. Cut it very small to fine Powder then take 12 Ants Eggs dried in an oven after ye bread is drawn or otherwise make them dry & make them to powder with the hair, give this with a quarter of a pint of Red Cows milk or for want of it give it in strong ale wort.

For ye Tooth AcheTake a Little Piece of opium as big as a great pins head & put it into the hollow place of the Aching Tooth & it will give present Ease, often tried by me upon many People & never failed. Zerobabel Endecott.

Falling Sickness (epilepsy or seizure) In Children. has of the dung of a black Cow 3i. given to a newborn Infant, doth not only preserve from the Epilepsia, but also cure it. In those of ripe Age. The livers of 40 water-Frogs brought into a powder, and given at five times (in Spirit of Rosemary or Lavender) morning and evening, will cure, the sick not eating nor drinking two hours before nor after it. — Compendium of Physick (Salmon), London, 1671. Salt of Mans Skull. The skull of a dead man, calcine it, and extract the Salts as that of Tartar. It is a real cure for the Falling-sickness. Vertigo, Lethargy, Numbness, and all capital diseases, in which it is a wonderful prevalent.— Compendium of Physick (Salmon), London, 1671.

To stop bleeding of the noseIf the flux be violent, open a vein on the same side, and cause the sick to smell to a dried Toad, or Spiders tied up in a rag; the fumes of Horns and Hair is very good, and the powder of Toads to be blowed up the Nose; in extremity, put teats made of Swines-dung up the nostrils. — Compendium of Physick (Salmon), London, 1671.Hog’s Dung is also used by the Country People to stop Bleeding at the Nose; by being externally applied cold to the Nostrils. –English Dispensatory(Quincy), London, 1742.

Published on June 19, 2013 22:59

June 13, 2013

Why the Pilgrim governor wanted to know about the Dyer “monster”

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

In October 1637, Mary Dyer gave birth to a premature, stillborn girl, which, according to descriptions, was an anencephalic (lacking more than a brainstem) and probably had spina bifida (neural tube defects). (See link to my article at the end.) This was the first anencephalic baby ever reported in America.

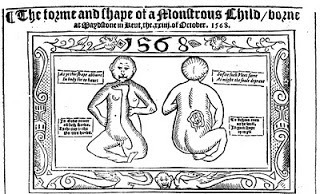

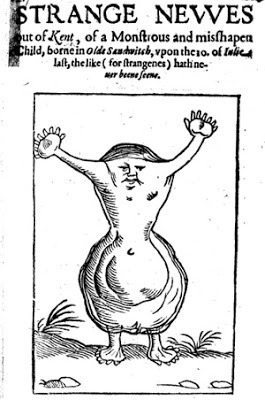

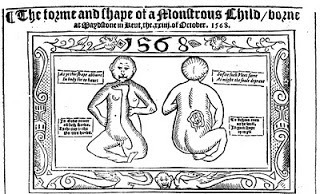

Drawing depicts an anencephalic child born in England,

Drawing depicts an anencephalic child born in England,

but not Mary Dyer's child.

It had no head, nor any sign or proportion thereof,

there only appeared as it were two faces,

the one visibly to be seen, directly placed in the breast,

where it had a nose, and a mouth, and two holes

for two eyes, but no eyes, all which seemed ugly,

and most horrible to be seen, and much offensive

to human nature to be looked upon,

the other face was not perfectly to be seen,

but retained a proportion of flesh in a great round lump,

like unto a face quite disfigured, and this was

all of that which could be discerned.

The face, mouth, eyes, nose, and breast,

being thus framed together like a deformed piece of flesh,

resembled no proportion of nature, but seemed

as it were a chaos of confusion,

a mixture of things without any description...

Back in their native country, England, gravely-deformed babies were called “monsters” or “monstrous births,” and were commonly known to be heaven-sent proof of heresy or monstrous religious or political beliefs of the mother.

Mary’s unnamed daughter’s birth deformities and burial place were kept a secret among a handful of people. But in March 1638, at Anne Hutchinson’s heresy trial and conviction in Boston, Massachusetts, Anne was excommunicated and sentenced to leave the church and colony. Anne’s and Mary’s husbands were not at the trial, because they were preparing their newly-purchased land in Pocasset, on Rhode Island, for their impending move. When Anne was told to depart the meeting house, Mary stood up, took Anne’s hand, and they walked out together. As they left the building, someone in the crowd mentioned that Mary was the mother of a “monster.” Governor John Winthrop, in his zeal to further prosecute Anne and her supporters, ordered the exhumation and examination of this monster, Mary Dyer’s baby, which had lain in the frozen ground for six months while Boston experienced a severely-cold winter, and Anne was under house arrest in Roxbury (at the home of my ancestor, Joseph Welde!).

The baby’s remains were disinterred, and more than one hundred men gawked at the corpse before it was reburied. Governor Winthrop wrote a description in his history journal, and within about four years, the baby’s features went viral in England, by way of several publications. One of those was a short book about Anne Hutchinson's theology, written by John Winthrop, with a foreword by Thomas Welde, Joseph Welde’s brother, which brought down hellfire and brimstone on both Mary and Anne.

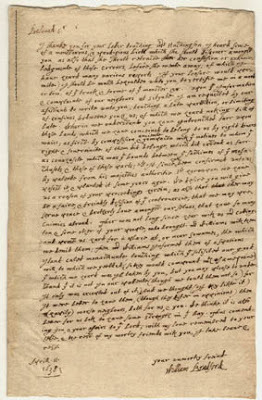

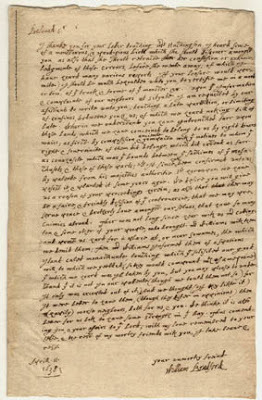

A holograph of William Bradford's letter to

A holograph of William Bradford's letter to

John Winthrop regarding Mary Dyer's stillborn baby.

Click to enlarge photo.

Source: Massachusetts Historical Society But on April 11, 1638, in the first month after the revelation of Anne’s trial and Mary’s monster, the governor of Plymouth Colony, William Bradford, wrote a letter to his friend and colleague, John Winthrop. Most of the letter was about colonial boundaries and the islands in the Narragansett Bay, which Plymouth insisted were part of their original royal patent, but generously released to the Indians—who then sold it to the Hutchinson party being routed from Boston! And there began a dispute that would last into the 1650s, when the Rhode Island charter and boundary was confirmed by the English Commonwealth government.

The first part of the Bradford letter, though, asked for juicy details of Mary Dyer’s poor baby. Like Winthrop, Bradford kept a historical journal (not a personal diary) meant for publication someday. Much of his work was used in William Brewster’s book, Mourt’s Relation, but today we know the Bradford original as Of Plymouth Plantation. Bradford, like Winthrop, used the court cases and interesting stories as moral lessons. For instance, Bradford remarked about the Pequot Indian massacre that his forces perpetrated in 1637: “It was a fearful sight to see them frying in the fire, with streams of blood quenching it; the smell was horrible, but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave praise to God.” And he described the June 1, 1638 New England earthquake as the Lord’s displeasure at a group splintering from New Plymouth and proposing to plant a new community.

So his request for information on Mary Dyer’s monster was a request for evidence of God’s displeasure with the heretics of Boston and then Rhode Island. In the end, though, he chose not to use whatever information he received. Other writers did not hesitate to reveal lurid details, in England and America. As you see in Bradford’s letter, he’d already heard “many various reports,” in the month since the baby’s exhumation, so it was a major topic of the time.

Here follows Governor Bradford’s letter to Governor Winthrop, which I’ve edited for 21st-century ease of reading:

For more information on Mary Dyer’s “monster,” visit my blog article HERE .

In October 1637, Mary Dyer gave birth to a premature, stillborn girl, which, according to descriptions, was an anencephalic (lacking more than a brainstem) and probably had spina bifida (neural tube defects). (See link to my article at the end.) This was the first anencephalic baby ever reported in America.

Drawing depicts an anencephalic child born in England,

Drawing depicts an anencephalic child born in England, but not Mary Dyer's child.

It had no head, nor any sign or proportion thereof,

there only appeared as it were two faces,

the one visibly to be seen, directly placed in the breast,

where it had a nose, and a mouth, and two holes

for two eyes, but no eyes, all which seemed ugly,

and most horrible to be seen, and much offensive

to human nature to be looked upon,

the other face was not perfectly to be seen,

but retained a proportion of flesh in a great round lump,

like unto a face quite disfigured, and this was

all of that which could be discerned.

The face, mouth, eyes, nose, and breast,

being thus framed together like a deformed piece of flesh,

resembled no proportion of nature, but seemed

as it were a chaos of confusion,

a mixture of things without any description...

Back in their native country, England, gravely-deformed babies were called “monsters” or “monstrous births,” and were commonly known to be heaven-sent proof of heresy or monstrous religious or political beliefs of the mother.

Mary’s unnamed daughter’s birth deformities and burial place were kept a secret among a handful of people. But in March 1638, at Anne Hutchinson’s heresy trial and conviction in Boston, Massachusetts, Anne was excommunicated and sentenced to leave the church and colony. Anne’s and Mary’s husbands were not at the trial, because they were preparing their newly-purchased land in Pocasset, on Rhode Island, for their impending move. When Anne was told to depart the meeting house, Mary stood up, took Anne’s hand, and they walked out together. As they left the building, someone in the crowd mentioned that Mary was the mother of a “monster.” Governor John Winthrop, in his zeal to further prosecute Anne and her supporters, ordered the exhumation and examination of this monster, Mary Dyer’s baby, which had lain in the frozen ground for six months while Boston experienced a severely-cold winter, and Anne was under house arrest in Roxbury (at the home of my ancestor, Joseph Welde!).

The baby’s remains were disinterred, and more than one hundred men gawked at the corpse before it was reburied. Governor Winthrop wrote a description in his history journal, and within about four years, the baby’s features went viral in England, by way of several publications. One of those was a short book about Anne Hutchinson's theology, written by John Winthrop, with a foreword by Thomas Welde, Joseph Welde’s brother, which brought down hellfire and brimstone on both Mary and Anne.

A holograph of William Bradford's letter to

A holograph of William Bradford's letter to John Winthrop regarding Mary Dyer's stillborn baby.

Click to enlarge photo.

Source: Massachusetts Historical Society But on April 11, 1638, in the first month after the revelation of Anne’s trial and Mary’s monster, the governor of Plymouth Colony, William Bradford, wrote a letter to his friend and colleague, John Winthrop. Most of the letter was about colonial boundaries and the islands in the Narragansett Bay, which Plymouth insisted were part of their original royal patent, but generously released to the Indians—who then sold it to the Hutchinson party being routed from Boston! And there began a dispute that would last into the 1650s, when the Rhode Island charter and boundary was confirmed by the English Commonwealth government.

The first part of the Bradford letter, though, asked for juicy details of Mary Dyer’s poor baby. Like Winthrop, Bradford kept a historical journal (not a personal diary) meant for publication someday. Much of his work was used in William Brewster’s book, Mourt’s Relation, but today we know the Bradford original as Of Plymouth Plantation. Bradford, like Winthrop, used the court cases and interesting stories as moral lessons. For instance, Bradford remarked about the Pequot Indian massacre that his forces perpetrated in 1637: “It was a fearful sight to see them frying in the fire, with streams of blood quenching it; the smell was horrible, but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave praise to God.” And he described the June 1, 1638 New England earthquake as the Lord’s displeasure at a group splintering from New Plymouth and proposing to plant a new community.

So his request for information on Mary Dyer’s monster was a request for evidence of God’s displeasure with the heretics of Boston and then Rhode Island. In the end, though, he chose not to use whatever information he received. Other writers did not hesitate to reveal lurid details, in England and America. As you see in Bradford’s letter, he’d already heard “many various reports,” in the month since the baby’s exhumation, so it was a major topic of the time.

Here follows Governor Bradford’s letter to Governor Winthrop, which I’ve edited for 21st-century ease of reading:

“Beloved Sir:“I thank you for your letter touching Mrs Huchngson [Anne Marbury Hutchinson, the result of her trials for seditions and heresy]; I heard since of a monstrous, & prodigious birth which she should discover amongst you; as also that she should retract her confession of acknowledgment of those errors, before she went away; of which I have heard many various reports. If your leisure would permit, I should be much beholden unto you, to certify me in a word or two, of the truth & form of that monster &c. Upon the Information & complaint of our neighbors at Scituate; I am requested by our assistants to write unto you, touching a late partition, or limiting of confines, between you & us; of which we heard nothing till of late. Wherein we understand you have Entrenched far upon those lands, which we have conceived to belong to us by right divers ways; as first by composition, & ancient compact with the natives to whom the right & sovereignty of them did belong, which did extend as far as Conahasete [Cohassett/Portsmouth, Rhode Island], which was the bounds between the Sachimes [sachems] of the Massachusetts, & those of these parts; 2ly. It since hath been confirmed unto us by patent from his majesties authority. 3ly. hereupon we have possessed it, & planted it some years ago. [Roger] Williams with them and pressed us hard for a place at, or near Sowames, the which we denied them; Then mr Williams Informed them of a spacious Island called monachunte, touching which the solicited our good will, to which we yielded, (so they would compound with Ossamequine) the which we heard was Ill taken by you, but you may please to understand that it is not In our patent (though we told them not so) for It only was excepted out of it.) And we thought (If they liked it) It were better to have them, (though they differ in opinions) then (happily) worse neighbors, Both for us, & you. We think it is also Better for us both to have some strength in the Bay.We desire you will give us a reason of your proceeding herein; as also that that there may be a faire, & friendly decision of the controversy; that we may preserve peace & brotherly love amongst our selves, that have so many Enemies abroad. There was not long since here with us mr Cottington [William Coddington] & some other of your people, who brought mr

Thus commending you, & your affairs to the Lord; with my love remembered to your self, & the rest of my worthy friends with you, I take leave & rest April. 11.

1638 Your unworthy friend William Bradford

For more information on Mary Dyer’s “monster,” visit my blog article HERE .

Published on June 13, 2013 01:14

June 1, 2013

Mary Dyer and Martin Luther King Jr on civil disobedience

June 1: anniversary of Mary Dyer's execution

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

“Civil disobedience is always a criticism of the existing power structure. And it's always been that way. That's the role of civil disobedience. That's the role of dissent.” ~Tim DeChristopher, environmental activist who disrupted an auction, was convicted, and then chose to serve two years in prison instead of taking a plea bargain.

The Calvinist Puritans of colonial America believed that one could never know if God would award salvation and eternal life. They obeyed the Old Testament biblical and civil laws scrupulously, and performed good works in the hope that God would find them worthy; and they took comfort from their difficult task. They believed that God had a body of people who he’d predestined for eternal life. They called themselves the Elect, or the Remnant, after the proportionately-small group of faithful believers mentioned in the Book of Revelation.

The Calvinist Puritans of colonial America believed that one could never know if God would award salvation and eternal life. They obeyed the Old Testament biblical and civil laws scrupulously, and performed good works in the hope that God would find them worthy; and they took comfort from their difficult task. They believed that God had a body of people who he’d predestined for eternal life. They called themselves the Elect, or the Remnant, after the proportionately-small group of faithful believers mentioned in the Book of Revelation. Mary Dyer, who had rejected that dogma with her adherence to the teachings on grace of Anne Marbury Hutchinson, became a Quaker in the 1650s. That sect believed that with the New Covenant that came with Christ on the cross, God would replace the laws written on stone (the Ten Commandments) with a God-given conscience that told one what was right and wrong. They believed that eternal life was a gift to any person who trusted God (that he loved his children and desired their salvation) and obeyed the conscience. Mary went to her death on the gallows with perfect confidence that her next breath would be drawn in heaven.

For the persecuting Puritans of colonial Boston and Plymouth, the Quaker loosie-goosie feel-good religion that went straight from believer to God and back, instead of through the deliberative filter of church and state, was a clear threat to their authority and would result in chaos and anarchy. They’d also lose their royal charter, life savings, tithes and taxes, political power, and personal investments in the colony if a royal governor were sent. They wanted those Quakers rooted out and kept out.

William Robinson, Marmaduke Stephenson, Mary Dyer, and many other early Quaker converts were given a choice to leave the colony and live, or stay and be brutally beaten and probably executed. Most of us today would think there’s no contest about what to do. But the Quakers believed that God had specifically commanded and placed them there, and they were happy about it! Rather than avoid trouble, they took a lot of effort to stir up the people to anger against their government—anger that would change laws and bring justice, mercy, righteousness, and liberty to their colony.

What Robinson, Stephenson, and Dyer saw in their minds’ eyes was that long-range goal, and they were not only willing, but joyful, at their selection and assignment to do God’s will.

Mary Dyer's handwriting from October 1659

Mary Dyer's handwriting from October 1659October 1659 execution date (from which Mary was reprieved) Mary’s letter to the General Court: ‘Therefore I leave these lines with you, appealing to the faithful and true witness of God, which is one in all consciences, before whom we must all appear; with whom I shall eternally rest, in everlasting joy and peace, whether you will hear or refuse. With him is my reward, with whom to live is my joy, and to die is my gain.”

Governor John Endecott of Massachusetts Bay Colony said, 'Take her away, marshal.' To which she returned, 'Yes, joyfully I go.' And in her going to the prison, she often uttered speeches of praise to the Lord; being full of joy.

The marshal asked Mary, "Are you not ashamed to walk thus between two young men?" "No,” answered Mary Dyer, "this is to me an hour of the greatest joy I ever had in this world. No ear can hear, no tongue can utter, and no heart can understand, the sweet incomes and the refreshments of the Spirit of the Lord, which I now feel."

June 1, 1660 march from prison to gallows: When offered her life if she would voluntarily leave the colony forever, Mary Dyer said no, “For in obedience to the will of the Lord I came, and in His will I abide, faithful unto death." Someone from the crowd called out, "Did you say you have been in Paradise?" Mary answered, "Yea, I have been in Paradise several days and now I am about to enter eternal happiness."

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., martyr for civil rights, in a speech just before his assassination.

“Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”

“Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”*****************

For information on the June 1, 1660 death of Mary Barrett Dyer, Englishwoman and colonial American, read the following links already posted in this blog.

Top 10 things you may not know about Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer: The establishment versus the individual

Mary Dyer and freedom of conscience

Mary Dyer and the First Amendment

Mary Dyer, pioneer of civil disobedience

Published on June 01, 2013 00:00

May 21, 2013

Mary Dyer's last 44 miles

© Christy K Robinson

The road between Boston and Providence, Rhode Island, was a familiar one to William and Mary Dyer. When it was hardly more than an Indian path through the forests and streams of Massachusetts, William had been part of the scouting parties which purchased Rhode Island from the Narragansett Indians.

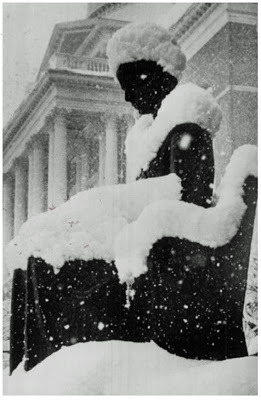

Then in the snowy spring of 1638, he and Mary elected to walk the path with the Hutchinson party after their expulsion from Massachusetts. They probably shipped their possessions around Cape Cod, but walked away like the Bible’s children of Israel, as a symbolic exodus from the heavy, theocratic hand of the Massachusetts Bay authorities.

Then in the snowy spring of 1638, he and Mary elected to walk the path with the Hutchinson party after their expulsion from Massachusetts. They probably shipped their possessions around Cape Cod, but walked away like the Bible’s children of Israel, as a symbolic exodus from the heavy, theocratic hand of the Massachusetts Bay authorities.The road would have been enlarged by commercial traffic and military expeditions during the late 1630s and early 1640s. William Dyer, as a Rhode Island government official and an attorney, would have traveled the road back to Boston many times. We don’t know if Mary accompanied him, because the next record we have of Mary is that she arrived by ship at Boston in March 1657 and was imprisoned as a Quaker.

William took Mary back to Newport, via the road to Providence, in summer 1657. But between 1658 and 1659, she’d made the trip from Providence to Boston several times with other Quakers, each time to support the imprisoned or call for their release. She was herself arrested several times, and was sentenced to be hanged on October 27, 1659. However, she was reprieved and was supposed to go home to Newport, Rhode Island.

She did, but not for long. (Her husband William said the next spring that the last time he saw his wife was in November.) About two weeks later, she’s mentioned as being in Plymouth Colony’s town of Sandwich, visiting the Quakers there. She was jailed and released.

She must have traveled from Sandwich to the Sylvester home on Shelter Island (eastern reaches of Long Island). There, she spent the winter in the company of her Friends, some of whom had been severely persecuted in Boston. In May 1660, Mary sailed across Long Island Sound, eastward to Narragansett Bay. Not stopping at her home in Newport, where resided her husband and children, she continued up the estuary and Seekonk River to Providence. Richard and Katherine (Marbury) Scott were co-founders of Providence, and were undoubtedly friends of many years—since at least 1635 when the Scotts, Hutchinsons, and Dyers lived in Boston. Katherine was Anne Marbury Hutchinson’s youngest sister, and was about a year older than Mary. Richard became a Quaker on a 1654 trip to England, which would make him the first Quaker in New England, if not America. His conversion predated the arrival of Quaker missionaries in 1656 and 1657. So the Scott home in Providence would have been the hub for Mary’s and other Quakers’ forays into Massachusetts.

This modern plotting of the route from Providence, RI, to Boston, MA, follows US 1 or 1A most of the way.

This modern plotting of the route from Providence, RI, to Boston, MA, follows US 1 or 1A most of the way. It's likely that this was also the original Indian path and later a wagon road.

Mary could have used her husband’s horses or rented a ride for herself and Patience Scott. But I believe this walk was symbolic of her first forced march from Boston, with the Hutchinsons. She walked out then, and now she was walking back to prove they’d not been able to beat her down. This was on her terms.

Mary Dyer and Patience Scott (12-year-old daughter of the Scotts, and niece of Anne Hutchinson) arrived in Boston on May 21, 1660, having walked from Providence, Rhode Island. Patience had walked this road several times, too, and had been jailed in Boston the summer before for preaching Quaker beliefs.

Mary and Patience arrived during the annual proceedings of the Massachusetts Bay Court, when the Governor, deputy governors, and other officials would be in Boston for annual elections, to hear superior court cases, and vote legislation based on their blend of religious and civil law. John Endecott had been reelected governor on May 20, and at his home in Salem that night, there had been a terrific thunderstorm for six hours, from 9pm to 3am. The lightning was so severe and long-lasting that it was recorded in the Salem annals. Mary and Patience were probably spending the night in the forest or countryside outside Boston's peninsula, and might have been subjected to similar weather.

On the morning of May 21, Mary Dyer and her Quaker Friends from Salem and Plymouth gathered in Boston to protest the extreme persecution of Quakers, knowing full well that they would be jailed, probably beaten, and in Mary's case, executed (June 1, 1660). To enter Boston, Mary would have walked past the gallows at the fortification on Boston Neck.

US 1, the road between Boston and Providence, in the Wrentham area.

US 1, the road between Boston and Providence, in the Wrentham area.As suggested by the Google map, a direct hiking route from Providence to Boston would be about 44 miles. I don’t know if this is the route Mary’s road would have taken—over the course of decades and centuries, roads don’t really move or change, they just enlarge or maybe straighten a bit. I imagine that the U.S. 1 and Interstate-95 corridors had their origins on the old Indian footpath, the most direct and easy route, that became a wagon road, then was paved, and at last became a turnpike. The path plotted on Google runs that corridor.

The estimated walk would take 14 hours, it says, but these days, the road is paved and level; in Mary’s time it would have been uphill and downhill, over streams or low, wet places, with gullies eroded after strong storms. And remembering the Ginger Rogers quip about dancing backwards and in heels, Mary and Patience did it in long skirts, carrying a pack of supplies for sleeping and eating on the journey. Surely there was plenty of time over the two or three days they were walking, for communion with God and each other. Mary’s next walk would be from the prison to the gallows on Boston Neck.

If it were you, would you make the long, hard walk of 44 miles, or would you take an alternate mode suggested by Google? They suggest public transit. Now, where's the public demonstration or the civil disobedience in that??

Published on May 21, 2013 23:11

May 1, 2013

Wall Street’s beginning: Plenty of bull

© 2012 by Christy K Robinson

Source: Bloomberg Three hundred sixty-some years ago, there were definitely bulls on Manhattan Island, but there was no Wall Street. The colonists of the Dutch West Indies Company inhabited the southern tip of the island, a city they called New Amsterdam. It was the Dutch capitol in America, from which they administered parts of Long Island, Delaware (after they snatched it from Swedish colonists), New Jersey, and their opportunistic settlements in Connecticut and the Hudson River Valley. Their director-general was Pieter Stuyvesant, who had administered the colony since 1647.

Source: Bloomberg Three hundred sixty-some years ago, there were definitely bulls on Manhattan Island, but there was no Wall Street. The colonists of the Dutch West Indies Company inhabited the southern tip of the island, a city they called New Amsterdam. It was the Dutch capitol in America, from which they administered parts of Long Island, Delaware (after they snatched it from Swedish colonists), New Jersey, and their opportunistic settlements in Connecticut and the Hudson River Valley. Their director-general was Pieter Stuyvesant, who had administered the colony since 1647.

After Stuyvesant traded away large portions of territory to the colonies of New Haven and Connecticut, his Dutch colonists were quite upset with him. The tensions with the Native Americans were always ready to flare up, and several unscrupulous Dutchmen had been discovered selling rum, firearms, and ammunition to the Indians.

In 1652, a naval war between England and the Netherlands had broken out not only in the English Channel, but in the Caribbean and the trade routes and ports of the Atlantic. Piracy and privateering were rampant. The English settlers on Long Island and the coasts along Long Island Sound learned that the Dutch were paying the Indians to attack the English and drive them off.

When settlers like the militia commander Captain John Underhill, a magistrate in the New Haven-governed area of Long Island, called for his fellow Englishmen to rise up against “the iniquitous government of Pieter Stuyvesant,” he was first imprisoned for sedition, then kicked out of New Netherland. (Captain Underhill had a Dutch wife and mother-in-law, so living among the Dutch was not a foreign concept to him.)

In the winter of 1652-53, both the English and Dutch settlers on Long Island were dissatisfied with Stuyvesant’s governing. They held community meetings and sent deputies from each village to demand reforms of the director-general, which he dismissed with the arrogant statement, “We derive our authority from God and the Company, not from a few ignorant subjects.”

Captain William Dyerwas at this time Rhode Island attorney general, and had already been commissioned by England’s Council of State in early October 1652. His orders were to “raise such forts and otherwise arm and strengthen your Colony, for defending yourselves against the Dutch, or other enemies of this Commonwealth, or for offending them, as you shall think necessary; and also to take and seize all such Dutch ships and vessels at sea, or as shall come into any of your harbors, or within your power, taking care that such account be given to the State as is usual in the like cases.”

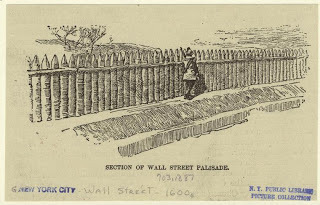

On March 17, six wealthy men of New Amsterdam, meanwhile, fearing both Indian and English attacks on their city, raised six thousand guilders to build a defensive palisade. They contracted with Thomas Baxter, a young man living there, to, within two weeks, provide masses of cut lumber and logs to build the wooden wall. (Baxter would shortly thereafter criticize Stuyvesant and leave his small home and catboat, to join the privateer forces under William Dyer and John Underhill.)

Stuyvesant ordered all men of the town, under pain of fine, loss of citizenship, and banishment, to dig a defensive ditch and post holes for the palisade that would run right across the island there, and make two gates and gatehouses, at what would later be called Broadway, and at the water gate on the East River. The wall was 2870 feet long, from the western end on the bluff of the Hudson River, to the East River. The palisade was built during the month of April, and completed on May 1, 1653. The earthen wagon road inside the palisade was called Waal Straat.

In May, Dyer and Underhill were commissioned by Rhode Island and the United Colonies of New England as Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas (Dyer) and Commander-in-Chief Upon the Land (Underhill).

William Dyer and John Underhill never attacked New Amsterdam, and the First Anglo-Dutch War ended by treaty in January 1653. But from 1680-82, Dyer’s second son, William Dyer the younger (born 1640 in Newport, Rhode Island), was mayor of the city of New York.

The Wall, having decayed over the last forty years, was dismantled in the 1690s, and the street that ran along the palisade became one of the most famous streets in the world—the home of high finance, and synonymous with greed and corruption.

Source: Bloomberg Three hundred sixty-some years ago, there were definitely bulls on Manhattan Island, but there was no Wall Street. The colonists of the Dutch West Indies Company inhabited the southern tip of the island, a city they called New Amsterdam. It was the Dutch capitol in America, from which they administered parts of Long Island, Delaware (after they snatched it from Swedish colonists), New Jersey, and their opportunistic settlements in Connecticut and the Hudson River Valley. Their director-general was Pieter Stuyvesant, who had administered the colony since 1647.

Source: Bloomberg Three hundred sixty-some years ago, there were definitely bulls on Manhattan Island, but there was no Wall Street. The colonists of the Dutch West Indies Company inhabited the southern tip of the island, a city they called New Amsterdam. It was the Dutch capitol in America, from which they administered parts of Long Island, Delaware (after they snatched it from Swedish colonists), New Jersey, and their opportunistic settlements in Connecticut and the Hudson River Valley. Their director-general was Pieter Stuyvesant, who had administered the colony since 1647. After Stuyvesant traded away large portions of territory to the colonies of New Haven and Connecticut, his Dutch colonists were quite upset with him. The tensions with the Native Americans were always ready to flare up, and several unscrupulous Dutchmen had been discovered selling rum, firearms, and ammunition to the Indians.

In 1652, a naval war between England and the Netherlands had broken out not only in the English Channel, but in the Caribbean and the trade routes and ports of the Atlantic. Piracy and privateering were rampant. The English settlers on Long Island and the coasts along Long Island Sound learned that the Dutch were paying the Indians to attack the English and drive them off.

When settlers like the militia commander Captain John Underhill, a magistrate in the New Haven-governed area of Long Island, called for his fellow Englishmen to rise up against “the iniquitous government of Pieter Stuyvesant,” he was first imprisoned for sedition, then kicked out of New Netherland. (Captain Underhill had a Dutch wife and mother-in-law, so living among the Dutch was not a foreign concept to him.)

In the winter of 1652-53, both the English and Dutch settlers on Long Island were dissatisfied with Stuyvesant’s governing. They held community meetings and sent deputies from each village to demand reforms of the director-general, which he dismissed with the arrogant statement, “We derive our authority from God and the Company, not from a few ignorant subjects.”

Captain William Dyerwas at this time Rhode Island attorney general, and had already been commissioned by England’s Council of State in early October 1652. His orders were to “raise such forts and otherwise arm and strengthen your Colony, for defending yourselves against the Dutch, or other enemies of this Commonwealth, or for offending them, as you shall think necessary; and also to take and seize all such Dutch ships and vessels at sea, or as shall come into any of your harbors, or within your power, taking care that such account be given to the State as is usual in the like cases.”

On March 17, six wealthy men of New Amsterdam, meanwhile, fearing both Indian and English attacks on their city, raised six thousand guilders to build a defensive palisade. They contracted with Thomas Baxter, a young man living there, to, within two weeks, provide masses of cut lumber and logs to build the wooden wall. (Baxter would shortly thereafter criticize Stuyvesant and leave his small home and catboat, to join the privateer forces under William Dyer and John Underhill.)

Stuyvesant ordered all men of the town, under pain of fine, loss of citizenship, and banishment, to dig a defensive ditch and post holes for the palisade that would run right across the island there, and make two gates and gatehouses, at what would later be called Broadway, and at the water gate on the East River. The wall was 2870 feet long, from the western end on the bluff of the Hudson River, to the East River. The palisade was built during the month of April, and completed on May 1, 1653. The earthen wagon road inside the palisade was called Waal Straat.

In May, Dyer and Underhill were commissioned by Rhode Island and the United Colonies of New England as Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas (Dyer) and Commander-in-Chief Upon the Land (Underhill).

William Dyer and John Underhill never attacked New Amsterdam, and the First Anglo-Dutch War ended by treaty in January 1653. But from 1680-82, Dyer’s second son, William Dyer the younger (born 1640 in Newport, Rhode Island), was mayor of the city of New York.

The Wall, having decayed over the last forty years, was dismantled in the 1690s, and the street that ran along the palisade became one of the most famous streets in the world—the home of high finance, and synonymous with greed and corruption.

Published on May 01, 2013 03:28

April 8, 2013

Does America have Founding Mothers?

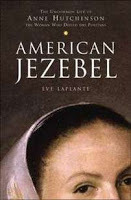

© 2013 by Eve LaPlante Used by permission

Three hundred and seventy-five years ago this month, Anne Hutchinson, forty-six years old and pregnant for the sixteenth time, became the only woman ever to co-found an American colony. She had recently been banished from Massachusetts for presuming to teach men – in addition to women, which was permissible – about the Bible. Then, in March 1638, after spending the winter under house arrest, apart from her family, Hutchinson was excommunicated by the First Church in Boston. Meanwhile, her husband and elder sons and a few male supporters sailed south to settle Portsmouth, Rhode Island, near Providence Plantation, which had been settled two years earlier by the Reverend Roger Williams, another Massachusetts outcast. In early April, accompanied by a large group of family and friends, Anne Hutchinson set out in thigh-deep snow to walk to her new home of Rhode Island, which would later merge with Williams’s settlement to form the colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation.

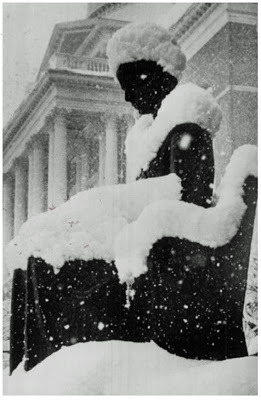

Anne Hutchinson memorial statue in Boston,

Anne Hutchinson memorial statue in Boston, near Mary Dyer's statue.Who was this remarkable woman? A child of Elizabethan England and of Shakespearean London, Anne Hutchinson had been born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1591, and spent her adolescence in a vicarage across the Thames from the Globe Theatre. Her father, a brilliant preacher who had himself been tried and imprisoned by the Church of England, gave her a defiant self-confidence and the gift of explaining Scripture. From her mother, an aunt of the poet John Dryden, she learned midwifery. At the age of twenty-one she married a wealthy merchant named William Hutchinson and returned to Lincolnshire, where she raised their large family and taught Puritan theology to other women at her home.For the next twenty years, Hutchinson collaborated with the celebrated Puritan minister John Cotton, who credited her with “preparing souls” for him to convert. “She had more resort to her for counsel about matters of conscience and clearing up men’s spiritual estates,” he said, “than any minister.” But Cotton sailed to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1633, after being silenced by the Church of England. Hutchinson and her family followed a year later, and by 1636 she was lecturing weekly to audiences of as many as eighty women and men in her Boston parlor.

Rev. John CottonIn her lectures she accused some colonial ministers of neglecting the central role of God’s grace in salvation. She charged them with preaching a “covenant of works” rather than the acceptable, Puritan “covenant of grace” elucidated by John Calvin. In Puritan theology, there was no causal link between doing good works and being saved. One could not achieve salvation through his or her own efforts or good works. To be eligible for salvation one had to be elected, before, by God. In early New England, however, ministers allied with Governor Winthrop preached that people could prove themselves worthy of salvation by displaying faith and performing good works – an appealing theological conceit that enforced obedience. This troubled Hutchinson, who was grounded in Calvinist theology and possessed of a strong sense of communion with the Holy Spirit. Moreover, her covenant of grace, with its immediate, felt sense of God’s presence, offered religious assurance to many people whose experiences at the meetinghouse left them anxious. “Seek for better establishment in Christ,” she advised her listeners, “not comfort” in “duties,” “works,” or “performances or righteousness of the law.”

Rev. John CottonIn her lectures she accused some colonial ministers of neglecting the central role of God’s grace in salvation. She charged them with preaching a “covenant of works” rather than the acceptable, Puritan “covenant of grace” elucidated by John Calvin. In Puritan theology, there was no causal link between doing good works and being saved. One could not achieve salvation through his or her own efforts or good works. To be eligible for salvation one had to be elected, before, by God. In early New England, however, ministers allied with Governor Winthrop preached that people could prove themselves worthy of salvation by displaying faith and performing good works – an appealing theological conceit that enforced obedience. This troubled Hutchinson, who was grounded in Calvinist theology and possessed of a strong sense of communion with the Holy Spirit. Moreover, her covenant of grace, with its immediate, felt sense of God’s presence, offered religious assurance to many people whose experiences at the meetinghouse left them anxious. “Seek for better establishment in Christ,” she advised her listeners, “not comfort” in “duties,” “works,” or “performances or righteousness of the law.”

Gov. John WinthropStung by her challenge, Governor Winthrop called her before the Massachusetts General Court on a charge of heresy for teaching, which he considered “not comely for [her] sex.” He derided her as “this American Jezebel,” a name any Puritan would recognize as belonging to the most evil woman in the Bible. At her civil trial, in 1637, and her church trial, in 1638, she defended herself brilliantly. Brazenly she informed the judges of the Massachusetts General Court, “I will give you the ground of what I know to be true.” In an era when a woman could not vote, hold public office, sign a legal document, teach men, or teach anyone outside her own home, Anne Hutchinson believed in the power of the individual conscience to determine the truth.Three hundred and seventy-five years later, in a nation that lacks for founding mothers, Anne Hutchinson deserves consideration. She co-founded a colony. She was midwife to the nation’s first college: a week after banishing her, the Massachusetts court ordered the building of Harvard College to enforce religious orthodoxy and to prevent a charismatic radical like her from ever again holding sway. She is one of the early Americans whose commitment to independent judgment inspired the religious-freedom clauses in the 1663 charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation and, ultimately, the 1789 Constitution of the United States. Her belief in the ability of the individual conscience to look inward to determine what is true underlies our modern concepts of religious tolerance, individual liberties, and free speech._________________

Gov. John WinthropStung by her challenge, Governor Winthrop called her before the Massachusetts General Court on a charge of heresy for teaching, which he considered “not comely for [her] sex.” He derided her as “this American Jezebel,” a name any Puritan would recognize as belonging to the most evil woman in the Bible. At her civil trial, in 1637, and her church trial, in 1638, she defended herself brilliantly. Brazenly she informed the judges of the Massachusetts General Court, “I will give you the ground of what I know to be true.” In an era when a woman could not vote, hold public office, sign a legal document, teach men, or teach anyone outside her own home, Anne Hutchinson believed in the power of the individual conscience to determine the truth.Three hundred and seventy-five years later, in a nation that lacks for founding mothers, Anne Hutchinson deserves consideration. She co-founded a colony. She was midwife to the nation’s first college: a week after banishing her, the Massachusetts court ordered the building of Harvard College to enforce religious orthodoxy and to prevent a charismatic radical like her from ever again holding sway. She is one of the early Americans whose commitment to independent judgment inspired the religious-freedom clauses in the 1663 charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation and, ultimately, the 1789 Constitution of the United States. Her belief in the ability of the individual conscience to look inward to determine what is true underlies our modern concepts of religious tolerance, individual liberties, and free speech._________________  Thank you, Eve, for this article on the remarkable character of one of America's founding mothers. I read American Jezebel several years ago, and rated it five-stars. It's well worth reading, especially if one is a descendant of Anne Hutchinson and/or Mary Dyer. For others who are descended from Samuel Sewell or other Salemites, take a look at Salem Witch Judge. I'm also looking forward to reading Marmee & Louisa, the relationship between Louisa May Alcott (author of Little Women) and her mother. Eve LaPlante is the author of American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, The Woman Who Defied the Puritans and two other biographies, Salem Witch Judge and Marmee & Louisa. She also wrote Seized and edited the 2012 collection My Heart Is Boundless: Writings of Abigail May Alcott, Louisa’s Mother. On Friday, October 25, 2013, at the Portsmouth Abbey School in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, LaPlante will deliver the Kearney Lecture in honor of Portsmouth’s 375th anniversary. For more information: visit

www.evelaplante.com

, with links to Eve's books' sales points. And you may follow her author page on Facebook.

Thank you, Eve, for this article on the remarkable character of one of America's founding mothers. I read American Jezebel several years ago, and rated it five-stars. It's well worth reading, especially if one is a descendant of Anne Hutchinson and/or Mary Dyer. For others who are descended from Samuel Sewell or other Salemites, take a look at Salem Witch Judge. I'm also looking forward to reading Marmee & Louisa, the relationship between Louisa May Alcott (author of Little Women) and her mother. Eve LaPlante is the author of American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, The Woman Who Defied the Puritans and two other biographies, Salem Witch Judge and Marmee & Louisa. She also wrote Seized and edited the 2012 collection My Heart Is Boundless: Writings of Abigail May Alcott, Louisa’s Mother. On Friday, October 25, 2013, at the Portsmouth Abbey School in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, LaPlante will deliver the Kearney Lecture in honor of Portsmouth’s 375th anniversary. For more information: visit

www.evelaplante.com

, with links to Eve's books' sales points. And you may follow her author page on Facebook. For information on the death of Anne Hutchinson and how it affected Mary Dyer, click here .

Published on April 08, 2013 20:40

March 19, 2013

Mary Dyer, pioneer of civil disobedience

© Christy K Robinson

Little did I know when I set out to write a historical novel (part fiction, lots of fact), that I’d come upon so many fantasies, assumptions, and falsities in my heroine’s so-called biographies, or discrepancies in timelines that expose obvious mistakes. Who thought that at least one of two documents thought to be written by her, was not written by her, but significantly changed; and because that happened to the first document, the second one is highly suspect? Or that much of what is “known” about her came from the highly-politicized and carefully-managed public relations wing of a budding religious movement?

Here’s what can be constructed about Mary Dyer: Shewas born Mary Barrett, about 1610-11 in England, parents unknown (though sensational-but-WRONG stories have Mary as the sixth-generation descendant of Henry VII. Did I mention this is WRONG?)seems to have been well-educated and could write beautifully when most middle-class women could barely read and rarely could writemarried William Dyer in 1633 at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church, which was an Anglican church at the time, before the Puritan regime took over in the 1640sburied newborn son on first wedding anniversaryemigrated to Boston in 1635, was admitted to church membership in a conservative Puritan church, where her new son was baptized by a man who would be a tormenter at her deathwas close friends with and mentee of outspoken female religious dissenter, Anne Hutchinsonin 1637 had a seven-months-gestation stillbirth of an anencephalic girl with spina bifida deformities; her pastor/teacher buried the fetus secretlyin 1638 offended Boston authorities by taking hand of Anne Hutchinson at Hutchinson’s heresy trial Mary’s “monster,” the stillborn fetus, was exhumed and shown to more than 100 men as proof of her heresy in following Anne Hutchinson’s beliefs.Because her husband William and 100 other men had signed a protest letter to the court in 1637, and refused to apologize, they were expelled from Massachusetts, effective May 1, 1638.William and Mary joined the Hutchinsons and about 75 families in purchasing Native American lands that would become the colony of Rhode Island. They co-founded the Rhode Island cities of Portsmouth and Newport. Mary had five children between 1640 and 1650 who lived to adulthood, but there are no existing records of what she was doing while William’s career in government and the law took off, and he increased their land holdings. In early 1652, Mary sailed to England, leaving children (aged 2-17) behind with friends. William followed later, to obtain a commission to act as privateer in the Anglo-Dutch War, in the Dutch territories around Long Island Sound. He returned to Rhode Island without Mary.In 1657, having at some point in the last 4 years become a Quaker, Mary and another woman sail from Bristol for Boston, but are detoured by extreme weather at sea. The ship waits out the winter in Barbados for a few weeks, and they return north on the Gulf Stream, arriving in Boston in March. Mary is arrested straight off the ship, having been reported as a Quaker. Her belongings are burned. She stays incarcerated for weeks until her husband receives a message in Rhode Island. He goes to Boston to rescue her and pays a bond for her release.Over the next two years, Mary supports the Quakers who come to Newport for refuge from Massachusetts, New Amsterdam, and Connecticut persecution. She protested the torture of Quakers in New Haven, Connecticut, and traveled again to Boston to support the imprisoned with material aid and spiritual comfort. After repeatedly defying her banishment orders and sentences of death if she returned, Mary and two Quaker men were condemned to death by hanging. The men are hanged before her eyes, but Mary is reprieved by the court in a piece of manufactured drama. She would rather have been martyred, and writes to the court. She is released to go home. But she can’t stay there when Quakers are beaten nearly to death, fined to the point of bankruptcy, and physically mutilated. She goes to Sandwich, Massachusetts and gets re-arrested and jailed for about a week. The man who transported her there is ordered to pay her jail costs and fine, and she is sent home to Newport. Instead of staying in safety with her family, in November 1659 Mary sails to the eastern tip of Long Island, to a small island in its harbor, called Shelter Island. She spends the winter with the Quakers who own the island. She may have taught Bible lessons to the natives there. Determined to rile the residents and defy the Boston court, Mary sails from Shelter Island past her own home without stopping, landing at Providence, Rhode Island. She and a female companion walk the same road back to Boston that the Anne Hutchinson group had walked in 1638 when they were expelled from Massachusetts Bay Colony. For the best effect, Mary times her arrival for late May 1660, for the sitting of the court. Mary is arrested for visiting Quakers being held in the prison there. This time she means to be martyred, and she is, on June 1, 1660.

Why would this Englishwoman of high social status, education, a mother of six, and economically well-off wife of an attorney general, described as beautiful and intelligent, intentionally provoke her own death at age 48 or 49?

Did her religious beliefs make her mentally unbalanced? As you know, religious beliefs, whether conservative, center, or liberal, are complicated. They’re partly about how you live your life in relationship with others and God, and partly what you expect as reward or punishment in the hereafter. For the people of the 17th century, religion was everything. Nothing happened unless God directed it. Life on earth was fleeting, especially when waves of plague, misery, poverty, and war seemed unceasing; but the hereafter was “where it was at.” It was eternal, inevitable—and the only alternative was eternal hellfire.

The American Puritans were much more conservative than those in England, perhaps due to the bitter persecutions they’d experienced prior to their emigration. They combined their civil laws with Old Testament religious laws: Ten Commandments, plus many rules in the Books of Moses that were written specifically for the Israelites during their 40-year wanderings, along with Calvinist beliefs that men had a better chance of heaven than women (because Eve sinned before Adam) and that eternal salvation was only for a relative few that had already been chosen by predestination. How did one know one was part of the Elect who would attain heaven? They never fully knew if they’d be saved, but they showed their desire and intent to God, by keeping the laws, and by making sure that one’s community members also kept the law. This, of course, led to spying and tattling.

American Puritans, then, were fearful of being lost, and frightened of a god as a harsh judge who, despite their lifelong, arduous work of being “good,” had no intention of saving them. When Anne Hutchinson in the 1630s and the Quakers in the 1650s came along saying that by faith in the free gift of God (grace), that God actually loved and desired their love, and that personal revelations of his will for their daily lives had replaced the old written law, people caught in that legalistic hell were attracted to a God of love and light. They could be saved. They would be saved.

Source: http://www.plainquaker.org/news.html

Source: http://www.plainquaker.org/news.htmlThis was, in effect, a giant threat to the Puritan judges and ministers because their authority was undermined, they expected chaos from those who felt they weren’t required to keep any laws, their “New Jerusalem” city-upon-a-hill project had failed, and not least: that the lawlessness would bring a royal governor over to administer Anglican and secular affairs, and the magistrates and founders would lose their 1629 charter and their lifelong financial investments in the colony.