Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England

March 16, 2024

Mary Dyer was NOT hanged for “being a Quaker”

© 2012, 2024 Christy K Robinson

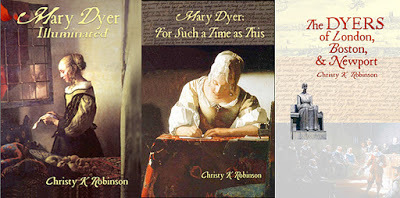

This nonfiction e-book

This nonfiction e-book by Christy K Robinson

(author of this blog) is an

anthology of research

on the Dyers, Anne Hutchinson,

John Winthrop, the cultures they

lived in and shaped, and the

civil liberties issues they

raised which affect us today.

http://amzn.to/1hWa8mc I know, that’s what most of the genealogy websites—and Wikipedia, and Ruth Plimpton's book, and countless opinions and feature articles say (actually, it's a wide circle of quoting one another). Recently, I learned that FamilySearch.org has quoted those sources, and that they plagiarized this very article despite its copyright notice.

But it’s not true that Mary Dyer was hanged for "being a Quaker."

Thanks to the Quaker missionaries from England, there were hundreds of Quaker (Religious Society of Friends) converts in New England in the late 1650s and early 1660s. They were subject to persecution and physical torture (imprisonment in wet or freezing jail cells, topless whipping for men and women, branding, having ears notched or sliced off, tongues bored through, being dragged from town to town, put in stocks, fined heavily and/or their possessions confiscated, banished) because they represented anarchy to the church-state government formed by the Massachusetts Bay founders. Quaker persecution also happened in England, and for the same reason—fear of anarchy to established traditions and government.

Not one person was hanged for religious beliefs in their hearts and minds for "being a Quaker," but because they were intentionally disobedient to anti-Quaker laws. You can see by Mary's 1659 letter to the Massachusetts court that she was ready for heaven, that she was appalled at their cruelty and wickedness, and that she chose to die.

When she left Shelter Island (now in the state of New York) in the spring of 1660 and walked from Providence, Rhode Island to Boston, Massachusetts, it was her intention to defy the anti-Quaker laws and be executed, specifically to bring attention to the cruelty of the theocratic governor and magistrates and their unjust laws, and raise public outcry against them. According to a Quaker observer, she believed 'it was required of her once more to visit Massachusetts, to finish, as she expresses it, "her sad and heavy experience in the bloody town of Boston."'

Today, we call this civil disobedience. She broke Puritan and Anglican societal rules of women remaining silent before men's authority. She defied her legal banishments by the rulers of Massachusetts Bay Colony. She provided comfort care to already-incarcerated Quakers.

Mary was re-tried on May 31, and hanged on June 1, 1660.

By the way, it is incorrect grammar to say that Mary was "hung." People are hanged, objects are hung.

***** This is one of many articles I've seen over the years, that repeats the error that Mary Dyer was hanged for "being a Quaker." https://www.southcoasttoday.com/story/news/state/2024/03/15/women-in-art-at-mass-state-house/72944627007/

*****

Christy K Robinson is author of these sites: Discovering Love (inspiration)Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)and of these books:· We Shall Be Changed (2010)

Christy K Robinson is author of these sites: Discovering Love (inspiration)Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)and of these books:· We Shall Be Changed (2010)· Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013)

· Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)

· The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014)

· Effigy Hunter (2015)

· Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother (2018)

July 21, 2022

How did Mary Dyer ride away after her prison release?

© 2022 Christy K Robinson

In the winter or early spring of 1657, Mary Dyer had returned from a four-year stay in England. Based on the timeline of a ship's voyage, she probably left Bristol around the end of December or early January. The ship fought heavy storms in the North Atlantic (which is why winter voyages were uncommon), and the captain was forced to sail past Boston all the way to a winter haven in Barbados. We know the ship stayed in Barbados for a few weeks because of two documents: a letter from Henry Fell to Margaret Fell, and the journal of John Taylor, which described Mary in glowing terms.

The ship left Barbados for Boston at about the middle of March, probably making a stop or two as it sailed north. When it arrived in Boston Harbor, the captain was ordered to show any Quakers known to be on board. The colony had created laws between August and October of 1656, ordering the whipping and jailing of Quakers, and the burning of their books and papers. Mary and her companion Anne Burden would have been aware of the laws when they landed in Barbados and stayed with Quakers there.

The women had decided to sail to Boston anyway, though they could have found ships bound for New Amsterdam (New York) or Rhode Island. When they arrived in Boston, probably in late March, they were arrested on the ship and dumped in the prison in Boston, there to languish for months. They were committed to "close confinement" so that "none could come at them."

How do we know? The Massachusetts General Court met in mid-May, and Mary was not on the docket, though she should have been. Her husband William was Solicitor General of Rhode Island, and he was engaged in Rhode Island colonial business during their May court sessions and elections, unaware of Mary's arrest and incarceration during that time. Anne Burden was not allowed to take care of her late husband's business affairs in Boston, but was banished and sent back to England after about three months in prison, during which time she was very ill.

These events give us an approximate timeline of Mary Dyer's first time in prison. After her husband William learned of her harsh treatment, he made an appearance in Boston and had her released. They would have ridden horses on the Post Road back to Rhode Island, a distance of perhaps 60 miles through farmlands and forest wilderness, crossing rivers and creeks. The journey needed to be as quick as possible, because Mary had been banished by Gov. John Endecott’s court, and that distance would probably mean at least two days of horse riding.

In my book, Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (Vol. 2 of The Dyers), I used those deductions to dramatize Mary's and William's reunion after several years apart.

The images here are sidesaddles of the type ridden by women in the early and mid-17th century. Women didn't often ride astride because of their undergarments (or lack of them), their skirts hitched up over their ankles which was immodest, and they didn't wear breeches unless they were "that" kind of woman. So they rode by sitting sideways on the back of a horse, with their skirts modestly draped around them, turning forward to guide the horse. Women riders rested their feet on the platform (planchette). Yes, there was a risk of sliding off.

One of the things an author needs to research is how people moved about in their world. I had to learn about how women rode horses in the 1650s. It required core strength to sit sideways and turn forward to guide the horse, and after a two-month stormy voyage followed by solitary confinement for three months, Mary would not have much strength or muscle tone. I decided (as the author, 356 years later) that she must have ridden some or most of the distance astride on her horse, or astride on William's.

After 1830, women hooked one knee over a second, lower pommel and put the other foot in the stirrup, as in this blue and red saddle.

********************Christy K Robinson is author of these books (click the colored title): We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Vol. 3 (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother (2018)

And of these sites: Discovering Love (inspiration and service)Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)Editornado [ed•i•tohr•NAY•doh] (Words. Communications. Book reviews. Cartoons.)

July 10, 2022

What our immigrant ancestors ate on the 17th-century Atlantic voyage

© 2022 Christy K Robinson

A 2017 article in Atlas Obscura pointed out the nasty foods and drinks consumed by ships' crews in the 17th century: decomposing brined beef and cod, dirty water, hardtack biscuits, and sour beer. Seasickness had less to do with motion than spoiled provisions. But what did the passengers eat and drink on the ships which carried them from Great Britain and Europe to North America? Voyages lasted a minimum of eight weeks, and up to 12 weeks if they fought winds, currents, or hurricanes.

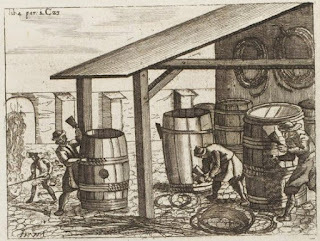

Coopers making barrels for ship cargo.

Coopers making barrels for ship cargo. Most passengers and their servants probably consumed similar fare of salted meat, or a stew of pease if they were lucky. Only three days into the 1630 voyage of the Winthrop Fleet, while the fleet’s occupants were fasting and praying, some farm laborers they’d brought “pierced a rundlet of strong water” (a 15-gallon barrel of whisky used primarily for medicinal purposes), and were put in "a bolt" (probably tied or chained to part of the ship) for a night and day to punish them.

A servant made a private deal with a boy (presumably the ship’s boy) to purloin three biscuits a day from the communal food supply, and upon discovery, the servant was tied to a bar and had a basket of stones placed around his neck for two hours. A maidservant, being seasick, drank so much whisky that she was “senseless, and had near killed herself. We observed it a common fault in our young people, that they gave themselves to drink hot waters [whisky] very immoderately.”

Lucky angler Marten Hvam has recently broken the record

Lucky angler Marten Hvam has recently broken the record for the biggest cod caught in Europe, with a specimen

that measured 4ft 9ins long and tipped the scales at 91lbs 15ozs.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2148477/Angler-catches-largest-cod-fish-caught-Europe-weighing-whopping-91lb.html

Running low on provisions after 12 weeks at sea, the Winthrop Fleet stopped to fish for fresh cod off Maine, and hauled in huge fish of a hundred pounds each, 67 on one day, and 36 on another. They made fires in sand-bottomed braziers on the ships' decks and cooked their fish for immediate feasting and to store for the remainder of the voyage.

Going back ten years to the Mayflower voyage, some historians speculate that the illness that killed half the passengers and crew in the winter and spring of 1620-21 was scurvy or some other severe nutrition deficiency. The Endecott Fleet in 1629 and the Winthrop Fleet in 1630 had terrible disease outbreaks and hundreds of immigrants died of fever or nutrition deficiencies in their first months on land. In February 1631, at a time when ships rarely crossed the Atlantic in winter because of violent storms, Captain Pearce brought desperately needed foods to Boston, along with "a store of lemons" that was needed to combat scurvy. Citrus is high in Vitamin C, which helps cure scurvy symptoms.

For people who were accustomed to dining on poultry, cheese, fish, pigeon pie, bread, root vegetables and leafy greens, ship fare could be a daunting prospect. ******************Christy K Robinson is author of these books (click the colored title): We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Vol. 3 (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother (2018)

And of these sites: Discovering Love (inspiration and service)Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)Editornado [ed•i•tohr•NAY•doh] (Words. Communications. Book reviews. Cartoons.)

January 29, 2022

Mary Dyer 'shined in the image of God'

© 2022 Christy K Robinson

John Taylor's journal was published

John Taylor's journal was published

in London in 1710.

In 2013, I did some background reading on the conversion experiences of Quakers, one of them from the public journal of a man born in the early 1630s in York, England. He actually met Mary Dyer on Shelter Island, New York, in the winter of 1659-60, a few months before she was hanged for civil disobedience. John Taylor spent the rest of his 70 years as an itinerant Quaker minister (they didn't believe in paid clergy) and a trans-Atlantic trader and merchant.

Taylor wrote of the 49-year-old Mary, "She was a very comely woman and grave matron, and even shined in the image of God. We had several brave meetings there together and the Lord's power and presence was with us gloriously. And Mary Dyer went away for Boston again, and said, she must go and offer up her life there and desire them to repeal that wicked law which they had made against God's people."

Taylor's assertion that Mary Dyer "shined in the image of God," a Quaker expression of their belief in God as Light, was one of the reasons I titled my first book on the Dyers, Mary Dyer Illuminated.

Christy K Robinson is author of these books: We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Vol. 3 (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother (2018)

And of these sites: Discovering Love (inspiration and service)Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)Editornado [ed•i•tohr•NAY•doh] (Words. Communications. Book reviews. Cartoons.)

September 19, 2021

#OnThisDay: William Dyer's baptism

I want to know who allowed the werewolves on the left side of the image.

I want to know who allowed the werewolves on the left side of the image.The woodcut is of an English christening in 1581.

© 2021 Christy K Robinson

William Dyer was born, say many genealogical sites, on Sept. 19, 1609. Well, maybe not "on this day" precisely, as he was baptized (christened) on Tuesday, Sept. 19. He might have been born up to a week earlier.

The church where William Dyer was baptized still stands in Kirkby LaThorpe, Lincolnshire. For a description of the interior, and photos, please read my article at

https://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2018/05/kirkby-la-thorpes-church-of-st-denys.html

To read some of the many articles on this site that describe William Dyer's remarkable life and accomplishments, read this selection, and then hit "Next Posts" at the bottom of that page.

June 13, 2021

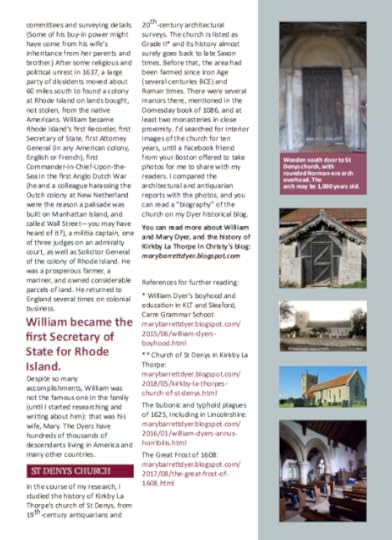

Lincolnshire magazine posts Dyer hometown connection

Copyright 2021 by Christy K Robinson

In the spring of 2021, I was asked to write a 600-word magazine article on William Dyer and Kirkby LaThorpe, the village where he was born in 1609. The article was published in "Heckington Living," a 40-page lifestyle magazine for Lincolnshire. The magazine editor had discovered my article and photos about the Kirkby LaThorpe church, from this website.

The editor, Amy Lennox, wrote: "Thank you again for your article - the locals were very complimentary about this issue!" I took screenshots, so here you go:

See:

* William Dyer's boyhood and education in KLT and Sleaford, Carre Grammar School <William & Mary Dyer: William Dyer’s boyhood (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)>

** Church of St Denys in Kirkby La Thorpe <William & Mary Dyer: Kirkby La Thorpe’s Church of St. Denys (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)>

The bubonic and typhoid plagues of 1625, including in Lincolnshire: <William & Mary Dyer: William Dyer’s annus horribilis -- Plagues of 1625 (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)>

The Great Frost of 1608: <William & Mary Dyer: The Great Frost of 1608 (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)>

** Church of St Denys in Kirkby La Thorpe

Denys in Kirkby La Thorpe <William & Mary Dyer: Kirkby La Thorpe’s Church of St. Denys (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)>

The bubonic and

typhoid plagues of 1625, including in Lincolnshire: <William & Mary Dyer: William Dyer’s annus horribilis -- Plagues of 1625 (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)>

The Great Frost of

1608: <William & Mary Dyer: The Great Frost of 1608 (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)>

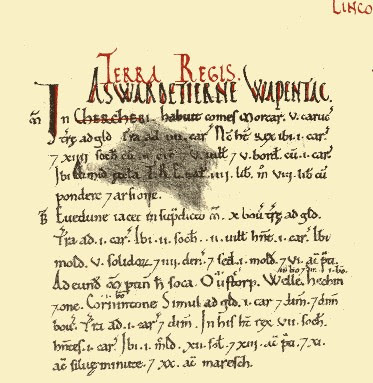

Domesday Book of 1086 that mentions the Saxon Earl Morcar and the

Domesday Book of 1086 that mentions the Saxon Earl Morcar and the area of Kirkby LaThorpe. (You can make out "thorp" in the second paragraph.)

The Domesday Book was a survey of who owned what and how much

could the king levy in rents and fighting men.

February 2, 2021

Anne Hutchinson featured in television documentary

In 2019, six documentary film producers were tasked with researching and filming six hour-long segments on the spread of Christianity across the world. The documentaries were pulled together by a script writer and narrated by actor Dennis Haysbert. Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) began airing the monthly episodes called “INEXPLICABLE: How Christianity Spread to the Ends of the Earth” in early 2020, but stopped at the beginning of the pandemic. They restarted the series, on a weekly basis, in January 2021.

Segment Four, the spread of Christianity in North America, was created by filmmaker James Langteaux, and airs Thursday, February 4, at 8:00 p.m. ET, 7:00 CT, 6:00 PT, and 5:00 PT, on TBN, which is a worldwide network, so it should be available to viewers of cable, satellite, and broadcast channels. (It may be available online after a few days.) The series combines interviews with experts and dramatic recreations of people and events.

Producer Langteaux contacted Christy K Robinson, author of two popular historical research blogs and four historical books that center on early colonial New England religious leaders, and asked her to speak “passionately” about Anne Marbury Hutchinson and her “bold, heroic life,” as he put it. Though he filmed Robinson for several hours, she doesn't expect to be onscreen more than a few seconds or minutes at the beginning of the episode.

She says, “I hope that my synopsis on Anne Hutchinson and Mary Barrett Dyer, the Quaker martyr who died for religious liberty in 1660, came in handy to the script writer. Both women were pioneers of religious and civil liberties in the 1630s through 1650s, almost 400 years before their time—and their struggle continues to this day.”

Robinson's interest in Anne Hutchinson began in the 1980s, when a Bible teacher talked about Antinomianism, which many historians have ascribed to Hutchinson's name. “Antinomian” means “against the entire (Old Testament/old covenant) Law,” which some believe was supplanted by the new covenant of salvation by grace. Robinson learned through years of research that religious denominations which arose in New England, owed much of their theology to the early colonial Puritan ministers, whose experiences, beliefs, and practices influenced generations of our ancestors, and numerous American denominations.

For more information on Anne Hutchinson, please visit <https://MaryBarrettDyer.blogspot.com/2020/01>

For more information on INEXPLICABLE, please visit Inexplicable | TBN <https://www.tbn.org/programs/inexplicable/episodes> .

Short trailer of Episode Four:

December 23, 2020

Run, Shepherds, Run, a 17th century poem

William Drummond was a Scottish poet who lived at the time when William and Mary Barrett Dyer and William and Anne Marbury Hutchinson were children and adults. They would not have known Drummond, but reading his poetry shows us the type of literature to which they were exposed during their lives.

Attributed to Abraham van Blijenberch.

Attributed to Abraham van Blijenberch.William Drummond of Hawthornden, 1585-1649.

Scottish National Portrait Gallery

This 1623 poem is religious in nature, but surprisingly, not of a Presbyterian (similar to Puritan) theology. It was written from a more episcopal (Church of England) perspective.

Run, Shepherds, run where Bethl’em blest appears,

We bring the best of news, be not dismayed:

A Saviour there is born, more old than years

Amidst Heaven’s rolling heights this earth who stayed;

In a poor cottage inned, a Virgin Maid,

A weakling did Him bear, who all upbears,

There is He poorly swaddled, in a manger laid

To whom too narrow swaddlings are our spheres:

Run, Shepherds, run, and solemnize His birth.

This is that night−no, day, grown great with bliss,

In which the power of Satan broken is;

In Heaven be glory, peace unto the Earth,

Thus singing through the air the angels swam,

A cope of stars re-echoed the same.

William Drummond

from Flowres of Sion

William Drummond (13 December 1585 – 4 December 1649), called "of Hawthornden", was a Scottish poet.

Our Dyers and Hutchinsons did not celebrate a Christmas holiday. It wasn't part of their religious beliefs to do so. But 400 years later, we do celebrate Christmas, whether as a secular day of family, food, and gift-giving, or as a holy day of thanks to God, or somewhere between. Whatever camp you fall into, I wish you a wonderful season of peace, prosperity, health, fellowship, and joy. I wish you a "cope of stars."

William & Mary Dyer: A 17th-century Christmas (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)

William & Mary Dyer: “Purifying” the customs and fun of Christmas (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)

William & Mary Dyer: The Puritan Problem with Father Christmas (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)

William & Mary Dyer: Christmas in 17th century England and America (marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com)

May 4, 2020

Book excerpt from Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

If you’re a descendant or admirer of the people mentioned in this chapter, you’re already primed to appreciate the historical research and writing expertise that went into this biographical novel: Mary Barrett Dyer Lawrence and Cassandra SouthwickNathaniel SylvesterJohn Endecott

And in the preceding chapter, you’d find: Katherine Marbury ScottIsaac RobinsonWilliam DyerSir Henry VaneGiles SlocumWilliam Brenton

There’s a lot of real, historical names and characterizations in my Mary Dyer books, because they were the people in William’s and Mary’s lives that helped define who they were, how they were interacting with one another, and what they were doing at the time.

Book extract from Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014), © 2014 Christy K Robinson

http://bit.ly/DyersSeries

http://bit.ly/DyersSeries May 12, 1660Shelter Island, Long Island

Mary was exhausted. She was not in the mood to hear or make another condolence. She didn’t want to hear, much less feel, more angry words about the wickedness of the colonial governments against the Friends, not in New England, and not in Virginia. She wanted something, but what? This morning, she and the Shelter Island Friends had gathered for a blessedly silent Meeting and then a burial service for Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick. Both of those dear people had died this week: first Cassandra and then a day later, Lawrence. Though Mary had done all she could to loosen the terrible knots under their skin caused by the triple lash, and soothe their pains by gently working scented and pain-relieving balm into their scars, all it took in the end was a respiratory fever. Once Cassandra was gone, Lawrence gave up and followed her. Again, Mary thought of the life force in a human being: sometimes it was strong, like a mighty river current, and other times, it was merely a trembling leaf on an aspen. The sixty-two-year-olds could endure savage beatings, they could tolerate the loss of every material thing they’d worked so hard for, they could hear of their adult children sitting in dark, cold prison, and grieve that their adolescent children had barely escaped being sold as slaves. But finally, they had left behind their torn old bodies for freedom and eternal joy in God’s presence. She wasn’t sure whether to rejoice or to weep, or to nurse a very natural fury at the evil that could inhabit the governor, assistants, and ministers of Boston, Salem, and Plymouth, who claimed to speak for God but were voracious lions seeking to devour harmless lambs. Nathaniel Sylvester hadn’t been convinced of the Friends’ teachings when Copeland, Holder, Robinson, and others visited here in previous years. Perhaps his sympathetic support of the Friends had something to do with his Barbados partners and past experience with Friends there—and something to do with his antagonistic attitude to the New Haven Colony which administered the English settlements on Long Island and had so gravely injured the Quaker missionaries. But something had changed. Perhaps it was Lawrence and Cassandra, perhaps it was Mary herself, for now Sylvester was in a hot lather to send a letter to the General Court at New Haven and declare himself a Friend. An outraged Friend, furious about the unwarranted, malevolent persecution by New England’s governments. How dare they, to hold Mary Fisher and Ann Austin in prison for five weeks, and inspect their naked bodies for marks of witchcraft or imp teats, to threaten death, and then ship them off to Barbados. Ann had said that though she’d borne five children in England, she’d never suffered as much as she had under those barbarous and cruel hands.Mary already knew what the false minister Davenport would say: that Nathaniel was slandering New England’s godly magistrates and himself in particular, and blaspheming God with his pernicious doctrines, and that he was entertaining members of a cursed sect. There would be fury, accusations, and perhaps arrests. These were the people who had begun their bloody work with Humphrey Norton. New Haven. Davenport. The earthquake. Was it really only two years ago? How the faces had changed in that time. Some had gone back to England. Sarah Gibbons drowned. William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson hanged. Richard Doudney, Mary Clark, and Mary Wetherhead all drowned in a shipwreck off Barbados. Anne Robinson dead of a fever in Jamaica. Now the Southwicks. And soon, Mary Dyer. She felt it. She knew the time was near, for the madness and hate of New England were still not ripe.But did she mourn her Friends? Deep down, no, for she knew that their salvation was secure and they were now part of that great cloud of witnesses. Instead, she mourned the suffering of the converts who were only obeying the quiet voice of God, and acting as scripture prescribed: to visit the sick and imprisoned, to be just, merciful, and humble, to love one another. She mourned for the families and children who didn’t understand where the hate came from, and why their naked, bleeding mothers had been dragged out to the wilderness and left to die, or suffered the winter in Boston prison, with no heat and little food. And because these women were not well-known, were not as educated or experienced as men, and to be honest, not as privileged and connected as Mary Dyer, they needed an obelisk or flag to rally around. They needed an advocate, and someone important enough to draw the attention of Endecott and Bellingham away from the outrages they visited upon the faithful. They needed the hearts of the people of New England turned from bloodthirst to pity and charity. And that Mary could do by God’s grace. She would have done it last October, but the Lord in his wisdom had used his two willing servants, Robinson and Stephenson, and reserved Mary’s sacrifice for such a time as this, when it would have a greater effect.Ah! That’s what Mary had been longing for. Not the prison and hardship, but knowing that every moment, she was fulfilling God’s will. She longed for the kingdom that was closer and more real than this world, and being in that place of perfect love.The annual Court of Elections would be held in Boston in ten days’ time, and she would be there. Even in taking the Southwicks home and releasing Mary from their care, the Lord was preparing her way. She had nothing to fear.

Read more from the five-star Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This .

*****

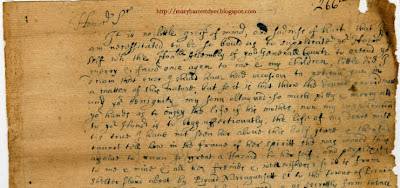

On May 27, 1660 (360 years ago), Mary’s husband, William Dyer, wrote an impassioned letter to the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, pleading with them to save his wife from the gallows. You can own a high-resolution 16x20” print of that letter written in William’s beautiful hand, by ordering it at this page:

http://

bit.ly/DyerHandwriting

On May 27, 1660 (360 years ago), Mary’s husband, William Dyer, wrote an impassioned letter to the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, pleading with them to save his wife from the gallows. You can own a high-resolution 16x20” print of that letter written in William’s beautiful hand, by ordering it at this page:

http://

bit.ly/DyerHandwriting

*****

Christy K Robinson is author of these books (click the colored title):

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Vol. 3 (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother (2018)

And of these sites: Discovering Love (inspiration and service)Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)Editornado [ed•i•tohr•NAY•doh] (Words. Communications. Book reviews. Cartoons.)

January 17, 2020

Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother chapter excerpt

© 2018 Christy K Robinson

In September 2018, I published a new, contemporary biography (nonfiction) on the life and legacy of Anne Marbury Hutchinson, 1591-1643. Its research, presentation, style, images, sources, and conclusions are unlike any other book written on Hutchinson.

The following article is part of a chapter introducing Anne Hutchinson to readers in the 21stcentury.

One of the interesting things about Anne is that she was a deeply spiritual woman all her life. But her legacy is that of promoting and practicing separation of church and state, and secular democracy, which was almost unheard of in the 17thcentury and earlier.

Here is the chapter section that shows the differences in the two compacts (a covenant) on which Rhode Island’s government began to form in 1638.

Anne Marbury Hutchinson: Founding mother of secular democracy Massachusetts Bay Colony was not founded as a democracy where the People govern themselves with elected representatives. Rev. John Cotton wrote:

"Democracy, I do not conceive that ever God did ordain as a fit government either for church or commonwealth. If the people be governors, who shall be governed? As for monarchy, and aristocracy, they are both of them clearly approved, and directed in scripture, yet so as referreth the sovereign to himself, and setteth up Theocracy in both, as the best form of government in the commonwealth, as well as in the church. … Purity, preserved in the church, will preserve well ordered liberty in the people, and both of them establish well-balanced authority in the magistrates. God is the author of all these three and neither is himself the God of confusion, nor are his ways of confusion, but of peace." Excerpted from The Correspondence of John Cotton. Sargent Bush, Jr., editor. The University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

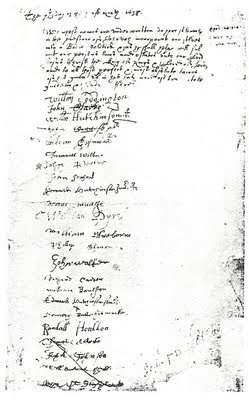

Portsmouth Compact, March 1638When the signers of the Wheelwright Remonstrance were disfranchised and disarmed by the Winthrop government in 1637, they determined to form a new “plantation,” or settlement, outside the Massachusetts charter boundaries. During Anne Hutchinson’s second trial, they organized themselves, purchased land, and prepared to move their households. The leading men signed the Portsmouth Compact, which appears to be written in William Dyer’s hand. In March 1638, they pledged:

Portsmouth Compact, March 1638When the signers of the Wheelwright Remonstrance were disfranchised and disarmed by the Winthrop government in 1637, they determined to form a new “plantation,” or settlement, outside the Massachusetts charter boundaries. During Anne Hutchinson’s second trial, they organized themselves, purchased land, and prepared to move their households. The leading men signed the Portsmouth Compact, which appears to be written in William Dyer’s hand. In March 1638, they pledged: The 7th Day of the First Month, 1638 [7 March 1638].We whose names are underwritten do hereby solemnly in the presence of Jehovah incorporate ourselves into a Bodie Politick and as He shall help, will submit our persons, lives and estates unto our Lord Jesus Christ, the King of Kings, and Lord of Lords, and to all those perfect and most absolute laws of His given in His Holy Word of truth, to be guided and judged thereby.

In the margin are noted three Bible texts, given here for your convenience: Exodus 24:3-4. Afterward Moses came and told the people all the words of the Lord, and all the Laws: and all the people answered with one voice, and said, All the things which the Lord hath said, will we do. And Moses wrote all the words of the Lord and rose up early, and set up an altar under the mountain, and twelve pillars according to the twelve tribes of Israel;1 Chronicles 11:3. So came all the Elders of Israel to the King to Hebron, and David made a covenant with them in Hebron before the Lord. And they anointed David king over Israel, according to the word of the Lord, by the hand of Samuel; and 2 Kings 11:17. And Jehoiada made a covenant between the Lord, and the King and the people, that they should be the Lord’s people: likewise between the King and the people.

We don’t know who suggested or insisted upon the scripture references, which have in common making a covenant with one another before God to obey his word and laws. It may have been William Coddington, who was a magistrate of the Bay Colony and one of the 1630 Winthrop Fleet pioneers who dreamed of building the New Jerusalem that would hasten the return of Jesus.It appears that the new plantation would have that familiar combination of church and state, and an adherence to the religious laws and government model of the Old Testament.After some disagreements about what Anne Hutchinson called “the magistracy,” a group led by William Coddington moved ten to 15 miles south on Aquidneck Island and founded Newport. The settlement at Portsmouth, Rhode Island, incorporated itself as a secular democracy in 1639, contrasted with the theocratic governments of the other English colonies – and of England, their native land. Portsmouth formed a new government, with William Hutchinson elected their “judge,” like the Old Testament judges of Israel before the monarchy of King Saul. Their new compact, signed by William and thirty others, read:

April 30, 1639 We, whose names are under written do acknowledge ourselves the legal subjects of his Majestie King Charles, and in his name do hereby bind ourselves into a civil body politick, unto his laws according to matters of justice.

The difference between the 1638 and 1639 agreements is stark. Religious language in the first, civil language in the second. Then, in March 1641, the island’s general court resolved,

It is ordered and unanimously agreed upon that the Government which this Bodie Politick doth attend unto in this Island, and the Jurisdiction thereof, in favour of our Prince is a Democracie, or popular Government; that is to say, It is in the Power of the Body of Freemen orderly assembled, or the major part of them, to make or constitute Just Laws, by which they will be regulated, and to depute from among themselves such Ministers [public servants] as shall see them faithfully executed between Man and Man.

Between man and man. They weren’t cutting out the relationship between God and man, or their devotion to serving God. But secular democracy for this group, who had fled religious persecution in England only five to ten years before, and theocratic oppression just one year before, was the very freedom they longed for and now had in their grasp. They were the point of a movement. And the movement, beginning with those conventicles in her parlor, was led by Anne Hutchinson.

To read more (299 pages more!) about Anne Hutchinson's life and legacy, see the 5-star book at Amazon:

Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother

*****

Christy K Robinson is author of these books (click the colored title): We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Vol. 3 (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother (2018)

And of these sites: Discovering Love (inspiration and service)Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)Editornado [ed•i•tohr•NAY•doh] (Words. Communications. Book reviews. Cartoons.)