Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 18

February 14, 2013

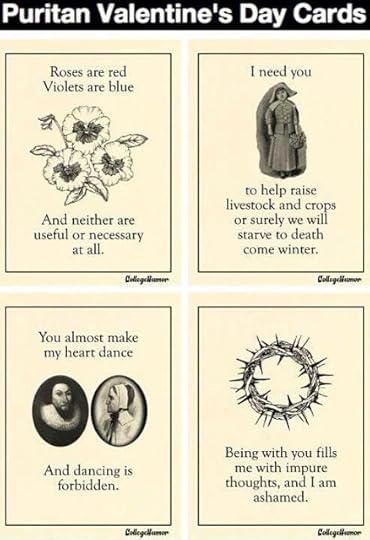

A Puritan valentine?

© Christy K Robinson

In frame 3 of the cartoon image, I'd like to point out that

In frame 3 of the cartoon image, I'd like to point out that Massachusetts Bay Gov. John Winthrop (d. 1649), a Puritan,

is courting a Quaker or Mennonite woman of the 19th century.

Winthrop married four times: his first two wives died because of childbirth,

his third wife, Margaret, died in middle age of yellow fever,

and his fourth wife survived him by eleven years--before she committed suicide.

Click HERE for that story. Puritans of the early and mid-17th century did NOT celebrate Catholic holidays or saint days like St. Valentine’s. Anathema!

But they did have an extremely strong commitment to families and a godly community, which they saw as a necessity to bring on the Second Coming of Christ. They were the Elect, the Remnant of God living in the earth’s last days. They were building the ideal "City Upon a Hill," the New Jerusalem. Puritans revered the institution of marriage.

New England Puritans were probably more strait-laced than those in Old England, due to their harrowing experiences and pioneering courage needed to build a new society in the harsh wilderness. They enjoyed social events, military exercises, fishing, cooking and sewing competitions, music performances, and dancing, though most dancing was segregated by gender.

Unmarried adults did not live alone--they were placed in families. (If they fornicated before marriage, which was fairly common, men and women were stripped to the waist and publicly whipped 10 stripes.) More than the sin of fornication, it seems that they were extremely concerned about the Christian raising and financial support of a resulting baby.

Adultery could result in execution, but if the Court was “merciful,” the offender might go the gallows and stand there with a rope around their neck before being released.

A holdover from England that was practiced in coastal America: If a widow had property and her neighbors were envious, she could be accused as a witch. If a widower had children, he often remarried within 3-6 months for companionship, as well as to keep the household running, and to make even more children. His new wife was sometimes a young widow with children who needed a father and support. This solution reduced the community's need to provide welfare relief. Though this sounds rather crass, it also celebrated godly, married love as a choice, instead of "romantic" or superficial relationships. It was a model of Christian salvation, like Christ and the Church as a bride.

Enjoy the laughs, and have a happy Valentine's Day.

Published on February 14, 2013 12:02

February 5, 2013

Watery Villagers: sea creatures of colonial New England

As observed by William Wood in New Englands Prospect, published in 1634-35 as an advertisement for Englishmen to emigrate to Massachusetts Bay Colony. Some of the species Wood mentions may have become extinct from over-fishing in the 17th and 18th centuries. Fishing and whaling in the North Atlantic were big business even before the New England colonies were established, and became one of the chief recreational pursuits of the settlers.

Let me leade you from the land to the Sea, to view what commodities may come from thence; there is no countrey knowne, that yeelds more variety of fish winter and summer: and that not onely for the present spending and sustentation of the plantations, but likewise for trade into other countries, so that those which have had stages & make fishing voyages into those parts, have gained (it is thought) more than the Newfoundland Jobbers. Codfish in these seas are larger than in Newfoundland, six or seven making a quintall, whereas there they have fifteene to the same weight; and though this they seeme a base and more contemptible commoditie in the judgement of more neate adventurers, yet it hath bin the enrichment of other nations, and is likely to prove no small commoditie to the planters, and likewise to England if it were thorowly undertaken. Salt may be had from the salt Islands, and as is supposed may be made in the countrey. The chiefe fish for trade is Cod, but for the use of the countrey, there is all manner of fish as followeth.

The king of waters, the Sea shouldering Whale,The snuffing Grampus, with the oyly Seale,The Storme presaging Porpus, Herring-Hogge,Lineshearing Sharke, the Catfish, and Sea Dogge,The Scale-fenc'd Sturgeon, wry mouthd Hollibut,The flounsing Sammon, Codfish, Greediguts [see below].Cole, Haddocke, Haicke, the Thornebacke, and the Scale,Whose Slimie outside makes himselfe in date, Still-Life of Fish and Cat by Clara Peeters, 1594-1657.

Still-Life of Fish and Cat by Clara Peeters, 1594-1657.

The stately Basse old Neptunes sleeting post,That tides it out and in from Sea to Coast.Consorting Herrings, and the bony Shad,Big bellied Alewives, Machrills richly cladWith Rainebow colours, thy Frost fist and the Smelt,As good as ever lady Gustus [taste] felt.The spotted Lamprons, Eeles, the Lamperies,That seeke fresh water brookes with Argus eyes;These waterie villagers with thousands more,Doe passe and repasse neare the verdant store.

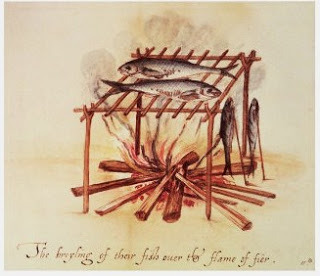

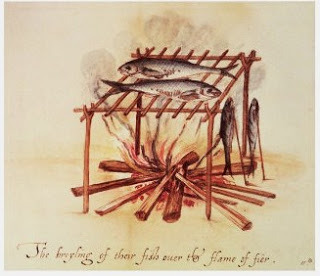

Broyling Fish Over Fire,

by John White c 1540-1593.

Broyling Fish Over Fire,

by John White c 1540-1593.

“The men bestow their time in fishing,

hunting, wars, and such man-like exercises,”

William Strachey wrote of Native Americans in 1609-1610. Kinds of all Shel-fish. The luscious Lobster, with the Crabfish raw,The Briniy Osier, Muscle, Periwigge,And Tortoise sought for by the Indian Squaw,Which to the slats daunce many a winters Jigge,To dive for Coddes, and to digge for Clamms,Whereby her lazie husbands guts hee cramms.

To omit such of these as are not usefull, therefore not to be spoken of, and onely to certifie you of such as be usefull.

First the Sealewhich is that which is called the Sea Calfe, his skinne is good for divers uses, his body being betweene fish and flesh, it is not very delectable to the pallate, or congruent with the stomack; his Oyle is very good to burne in Lampes, of which he affords a great deale.

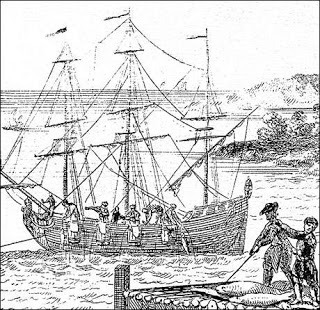

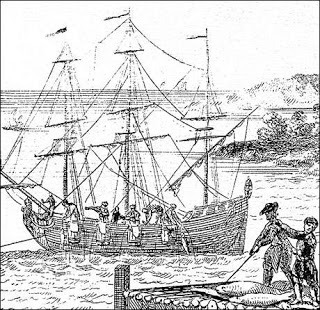

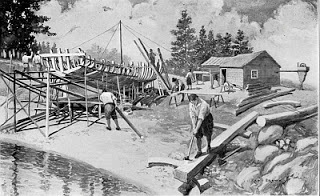

Late 17th century fishing vessel.

Late 17th century fishing vessel.

Ships such as this one often frequented the coastal waters

around the island of Newfoundland on a seasonal

basis during the 17th and 18th centuries. Ship detail

from a French woodcut of unknown origins. In 1710,

a similar scene appeared on the Herman Moll map

of North America with the English description,

"A VIEW OF A STAGE & ALSO YE MANNER OF

FISHING FOR, CURING & DRYING COD AT

NEWFOUNDLAND."

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/17century_vessel.html The Sharke is a kinde of fish as bigge as a man, some as bigge as a horse, with three rowes of teeth within his mouth, with which he snaps asunder the fishermans lines, if he be not very circumspect: This fish will leape at a mans hand if it be over board, and with his teeth snap off a mans legge or hand if he be a swimming; These are often taken, being good for nothing but to put on the ground for manuring of land.

The Sturgeons be all over the countrey, but the best catching of them be upon the shoales of Cape Codde, and in the River of Mirrimacke, where much is taken, pickled and brought for England, some of these be 12. 14. 18. foote long: I set not downe the price of fish there, because it is so cheape, so that one may have as much for two pence, as would give him an angell in England. The Sammon is as good as it is in England and in great plenty. The Hollibut is not much unlike a plaice or Turbot, some being two yards long and one wide: and a foot thicke; the plenty of better fish makes these of little esteeme, except the head and finnes, which stewed or baked is very good: these Hollibuts be little set by while Basse is in season. Thornebackeand Scates [rays] is given to the dogges, being not counted worth the dressing in many places.

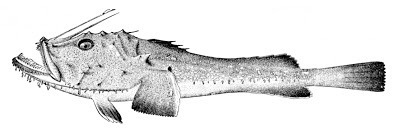

Atlantic bass, William Wood's favorite fish, apparently.

Atlantic bass, William Wood's favorite fish, apparently.

Do not neglect the "sweet, good, pleasant to the palate,

wholesome" marrow in the headbone. (Ack!)

Wood describes bass as 3-4 feet long or larger,

so today's bass must be wimps compared

to those in the 1630s. The Basse is one of the best fishes in the countrey, and though men are soone wearied with other fish, yet are they never with Basse; it is a delicate, fine, fat, fast fish, having a bone in his head, which containes a sawcerfull of marrow sweet and good, pleasant to the pallat, and wholsome to the stomack. When there be great store of them,we onely eate the heads, and salt up the bodies for winter, which exceedes Ling or Haberdine. Of these fishes some be three and some foure foot long, some bigger, some lesser: at some tides a man may catch a dozen or twenty of these in three houres, the way to catch them is with hooke and line: The Fisherman taking a great Cod-line, to which he fastneth a peece of Lobster, and throwes it into the Sea, the fish biting at it he pulls her to him, and knockes her on the head with a sticke.

These are at one time (when Alewives passe up the Rivers) to be catched in Rivers, in Lobster time at the Rockes, in Macrill time in the Bayes, at Michelmas in the Seas. When they use to tide it in and out to the Rivers and Creekes, the English at the top of an high water do crosse the Creekes with long seines or Basse Netts, which stop in the fish; and the water ebbing from them they are left on the dry ground, sometimes two or three thousand at a set, which are salted up against winter, or distributed to such as have present occasion either to spend them in their houses, or use them for their ground. The Herrings be much like them that be caught on the English coasts. Alewives be a kind of fish which is much like a Herring, which in the latter end of Aprill come up to the fresh Rivers to spawne, in such multitudes as is allmost incredible, pressing up in such shallow waters as will scarce permit them to swimme, having likewise such longing desire after the fresh water ponds, that no beatings with poles, or forcive agitations by other devices, will cause them to returne to the sea, till they have cast their Spawne. The Shaddesbe bigger than the English Shaddes and fatter.

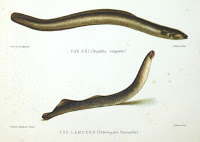

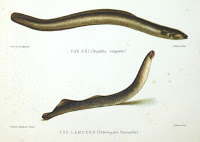

The Macrills [mackerel] be of two sorts, in the beginning of the yeare are great ones, which be upon the coast; some are 18. inches long. In Summer as in May, June, July, and August, come in a smaller kind of them: These Macrills are taken with drailes which is a long small line, with a lead and hooke at the end of it, being baited with a peece of red cloath: this kind of fish is counted a leane fish in England, but there it is so fat, that it can scarce be saved against winter without reisting. Eel and lampern There be a great store of Salt water Eeles, especially in such places where grasse growes: for to take these there be certaine Eele pots made of Osyers, which must be baited with a peece of Lobster, into which the Eeles entering cannot returne backe againe: some take a bushel in a night in this manner, eating as many as they have neede of for the present, and salt up the rest against winter. These Eeles be not of so luscious a taste as they be in England, neyther are they so aguish [feverish? shivering? quivering?], but are both wholesome for the body, and delightfull for the taste: Lamprons and Lampreyes be not much set by. [See Kathleen Wall's article on Eels--Fat and Sweet HERE.]

Eel and lampern There be a great store of Salt water Eeles, especially in such places where grasse growes: for to take these there be certaine Eele pots made of Osyers, which must be baited with a peece of Lobster, into which the Eeles entering cannot returne backe againe: some take a bushel in a night in this manner, eating as many as they have neede of for the present, and salt up the rest against winter. These Eeles be not of so luscious a taste as they be in England, neyther are they so aguish [feverish? shivering? quivering?], but are both wholesome for the body, and delightfull for the taste: Lamprons and Lampreyes be not much set by. [See Kathleen Wall's article on Eels--Fat and Sweet HERE.]

Lobsters be in plenty in most places, very large ones, some being 20. pound in weight; these are taken at a low water amongst the rockes, they are very good fish, the small ones being the best, their plenty makes them little esteemed and seldome eaten. The Indians get many of them every day for to baite their hookes withall, and to eate when they can get no Basse.

The Oisters be great ones in forme of a shoo horne, some be a foote long, these breede on certaine bankes that are bare every spring tide. This fish without the shell is so big that it must admit of a division before you can well get it into your mouth.

The "periwig fish" is

The "periwig fish" is

probably the starlet sea

anemone, which lives in

salt marshes. Thanks to

Alysa Farrell for

help in identification.

The Perewig is a kind of fish that lyeth in the ooze like a head of haire, which being touched conveyes it selfe leaving nothing to bee seene but a small round hole.

Muscles [mussels] be in great plenty, left onely for the Hogges, which if they were in England would be more esteemed of the poorer sort. Clammsor Clamps is a shel-fish not much unlike a cockle, it lyeth under the sand, every six or seven of them having a round hole to take ayre and receive water at. When the tide ebbs and flowes, a man running over these Clamm bankes will presently be made all wet, by their spouting of water out of those small holes: These fishes be in great plenty in most places of the countrey, which is a great commoditie for the feeding of Swine, both in winter, and Summer; for being once used to those places, they will repaire to them as duely every ebbe, as if they were driven to them by keepers: In some places of the countrey there bee Clamms as bigge as a pennie white loafe, which are great dainties amongst the natives, and would bee in good esteeme amongst the English were it not for better fish.

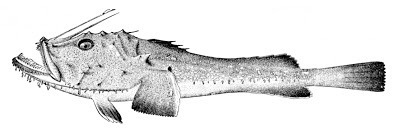

************* Greediguts fish (Lophius piscatorius) is one U.G.L.Y. fish!

Greediguts fish (Lophius piscatorius) is one U.G.L.Y. fish!

'The singular appearance and habits of the goosefish have gained it numerous appellations. In Massachusetts the fishermen know it by the names "goosefish," "angler," or "fishing frog." In Maine it is the "monkfish," in Rhode Island the "bellows-fish," in eastern Connecticut the "molligut," and in South Carolina "allmouth." The early colonial writers refer to it as the "greedigut." It is also known as the "wide-gap," "kettle-maw," and "sea devil."' ~Unutilized fishes and their relation to the fishing industries, by Irving Angell Field.

Color photo of greediguts fish: http://www.marlin.ac.uk/imgs/o_loppis2.jpg

More about New England fish: http://www.narragansettbay.info/swgamefish.cfm

Massachusetts Bay underwater: http://www.mwra.state.ma.us/harbor/html/mb_images.htm

17th-century sea monsters: http://scolarcardiff.wordpress.com/2012/01/19/science-and-sea-monsters/

Let me leade you from the land to the Sea, to view what commodities may come from thence; there is no countrey knowne, that yeelds more variety of fish winter and summer: and that not onely for the present spending and sustentation of the plantations, but likewise for trade into other countries, so that those which have had stages & make fishing voyages into those parts, have gained (it is thought) more than the Newfoundland Jobbers. Codfish in these seas are larger than in Newfoundland, six or seven making a quintall, whereas there they have fifteene to the same weight; and though this they seeme a base and more contemptible commoditie in the judgement of more neate adventurers, yet it hath bin the enrichment of other nations, and is likely to prove no small commoditie to the planters, and likewise to England if it were thorowly undertaken. Salt may be had from the salt Islands, and as is supposed may be made in the countrey. The chiefe fish for trade is Cod, but for the use of the countrey, there is all manner of fish as followeth.

The king of waters, the Sea shouldering Whale,The snuffing Grampus, with the oyly Seale,The Storme presaging Porpus, Herring-Hogge,Lineshearing Sharke, the Catfish, and Sea Dogge,The Scale-fenc'd Sturgeon, wry mouthd Hollibut,The flounsing Sammon, Codfish, Greediguts [see below].Cole, Haddocke, Haicke, the Thornebacke, and the Scale,Whose Slimie outside makes himselfe in date,

Still-Life of Fish and Cat by Clara Peeters, 1594-1657.

Still-Life of Fish and Cat by Clara Peeters, 1594-1657.

The stately Basse old Neptunes sleeting post,That tides it out and in from Sea to Coast.Consorting Herrings, and the bony Shad,Big bellied Alewives, Machrills richly cladWith Rainebow colours, thy Frost fist and the Smelt,As good as ever lady Gustus [taste] felt.The spotted Lamprons, Eeles, the Lamperies,That seeke fresh water brookes with Argus eyes;These waterie villagers with thousands more,Doe passe and repasse neare the verdant store.

Broyling Fish Over Fire,

by John White c 1540-1593.

Broyling Fish Over Fire,

by John White c 1540-1593.“The men bestow their time in fishing,

hunting, wars, and such man-like exercises,”

William Strachey wrote of Native Americans in 1609-1610. Kinds of all Shel-fish. The luscious Lobster, with the Crabfish raw,The Briniy Osier, Muscle, Periwigge,And Tortoise sought for by the Indian Squaw,Which to the slats daunce many a winters Jigge,To dive for Coddes, and to digge for Clamms,Whereby her lazie husbands guts hee cramms.

To omit such of these as are not usefull, therefore not to be spoken of, and onely to certifie you of such as be usefull.

First the Sealewhich is that which is called the Sea Calfe, his skinne is good for divers uses, his body being betweene fish and flesh, it is not very delectable to the pallate, or congruent with the stomack; his Oyle is very good to burne in Lampes, of which he affords a great deale.

Late 17th century fishing vessel.

Late 17th century fishing vessel.Ships such as this one often frequented the coastal waters

around the island of Newfoundland on a seasonal

basis during the 17th and 18th centuries. Ship detail

from a French woodcut of unknown origins. In 1710,

a similar scene appeared on the Herman Moll map

of North America with the English description,

"A VIEW OF A STAGE & ALSO YE MANNER OF

FISHING FOR, CURING & DRYING COD AT

NEWFOUNDLAND."

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/17century_vessel.html The Sharke is a kinde of fish as bigge as a man, some as bigge as a horse, with three rowes of teeth within his mouth, with which he snaps asunder the fishermans lines, if he be not very circumspect: This fish will leape at a mans hand if it be over board, and with his teeth snap off a mans legge or hand if he be a swimming; These are often taken, being good for nothing but to put on the ground for manuring of land.

The Sturgeons be all over the countrey, but the best catching of them be upon the shoales of Cape Codde, and in the River of Mirrimacke, where much is taken, pickled and brought for England, some of these be 12. 14. 18. foote long: I set not downe the price of fish there, because it is so cheape, so that one may have as much for two pence, as would give him an angell in England. The Sammon is as good as it is in England and in great plenty. The Hollibut is not much unlike a plaice or Turbot, some being two yards long and one wide: and a foot thicke; the plenty of better fish makes these of little esteeme, except the head and finnes, which stewed or baked is very good: these Hollibuts be little set by while Basse is in season. Thornebackeand Scates [rays] is given to the dogges, being not counted worth the dressing in many places.

Atlantic bass, William Wood's favorite fish, apparently.

Atlantic bass, William Wood's favorite fish, apparently. Do not neglect the "sweet, good, pleasant to the palate,

wholesome" marrow in the headbone. (Ack!)

Wood describes bass as 3-4 feet long or larger,

so today's bass must be wimps compared

to those in the 1630s. The Basse is one of the best fishes in the countrey, and though men are soone wearied with other fish, yet are they never with Basse; it is a delicate, fine, fat, fast fish, having a bone in his head, which containes a sawcerfull of marrow sweet and good, pleasant to the pallat, and wholsome to the stomack. When there be great store of them,we onely eate the heads, and salt up the bodies for winter, which exceedes Ling or Haberdine. Of these fishes some be three and some foure foot long, some bigger, some lesser: at some tides a man may catch a dozen or twenty of these in three houres, the way to catch them is with hooke and line: The Fisherman taking a great Cod-line, to which he fastneth a peece of Lobster, and throwes it into the Sea, the fish biting at it he pulls her to him, and knockes her on the head with a sticke.

These are at one time (when Alewives passe up the Rivers) to be catched in Rivers, in Lobster time at the Rockes, in Macrill time in the Bayes, at Michelmas in the Seas. When they use to tide it in and out to the Rivers and Creekes, the English at the top of an high water do crosse the Creekes with long seines or Basse Netts, which stop in the fish; and the water ebbing from them they are left on the dry ground, sometimes two or three thousand at a set, which are salted up against winter, or distributed to such as have present occasion either to spend them in their houses, or use them for their ground. The Herrings be much like them that be caught on the English coasts. Alewives be a kind of fish which is much like a Herring, which in the latter end of Aprill come up to the fresh Rivers to spawne, in such multitudes as is allmost incredible, pressing up in such shallow waters as will scarce permit them to swimme, having likewise such longing desire after the fresh water ponds, that no beatings with poles, or forcive agitations by other devices, will cause them to returne to the sea, till they have cast their Spawne. The Shaddesbe bigger than the English Shaddes and fatter.

The Macrills [mackerel] be of two sorts, in the beginning of the yeare are great ones, which be upon the coast; some are 18. inches long. In Summer as in May, June, July, and August, come in a smaller kind of them: These Macrills are taken with drailes which is a long small line, with a lead and hooke at the end of it, being baited with a peece of red cloath: this kind of fish is counted a leane fish in England, but there it is so fat, that it can scarce be saved against winter without reisting.

Eel and lampern There be a great store of Salt water Eeles, especially in such places where grasse growes: for to take these there be certaine Eele pots made of Osyers, which must be baited with a peece of Lobster, into which the Eeles entering cannot returne backe againe: some take a bushel in a night in this manner, eating as many as they have neede of for the present, and salt up the rest against winter. These Eeles be not of so luscious a taste as they be in England, neyther are they so aguish [feverish? shivering? quivering?], but are both wholesome for the body, and delightfull for the taste: Lamprons and Lampreyes be not much set by. [See Kathleen Wall's article on Eels--Fat and Sweet HERE.]

Eel and lampern There be a great store of Salt water Eeles, especially in such places where grasse growes: for to take these there be certaine Eele pots made of Osyers, which must be baited with a peece of Lobster, into which the Eeles entering cannot returne backe againe: some take a bushel in a night in this manner, eating as many as they have neede of for the present, and salt up the rest against winter. These Eeles be not of so luscious a taste as they be in England, neyther are they so aguish [feverish? shivering? quivering?], but are both wholesome for the body, and delightfull for the taste: Lamprons and Lampreyes be not much set by. [See Kathleen Wall's article on Eels--Fat and Sweet HERE.] Lobsters be in plenty in most places, very large ones, some being 20. pound in weight; these are taken at a low water amongst the rockes, they are very good fish, the small ones being the best, their plenty makes them little esteemed and seldome eaten. The Indians get many of them every day for to baite their hookes withall, and to eate when they can get no Basse.

The Oisters be great ones in forme of a shoo horne, some be a foote long, these breede on certaine bankes that are bare every spring tide. This fish without the shell is so big that it must admit of a division before you can well get it into your mouth.

The "periwig fish" is

The "periwig fish" is probably the starlet sea

anemone, which lives in

salt marshes. Thanks to

Alysa Farrell for

help in identification.

The Perewig is a kind of fish that lyeth in the ooze like a head of haire, which being touched conveyes it selfe leaving nothing to bee seene but a small round hole.

Muscles [mussels] be in great plenty, left onely for the Hogges, which if they were in England would be more esteemed of the poorer sort. Clammsor Clamps is a shel-fish not much unlike a cockle, it lyeth under the sand, every six or seven of them having a round hole to take ayre and receive water at. When the tide ebbs and flowes, a man running over these Clamm bankes will presently be made all wet, by their spouting of water out of those small holes: These fishes be in great plenty in most places of the countrey, which is a great commoditie for the feeding of Swine, both in winter, and Summer; for being once used to those places, they will repaire to them as duely every ebbe, as if they were driven to them by keepers: In some places of the countrey there bee Clamms as bigge as a pennie white loafe, which are great dainties amongst the natives, and would bee in good esteeme amongst the English were it not for better fish.

*************

Greediguts fish (Lophius piscatorius) is one U.G.L.Y. fish!

Greediguts fish (Lophius piscatorius) is one U.G.L.Y. fish! 'The singular appearance and habits of the goosefish have gained it numerous appellations. In Massachusetts the fishermen know it by the names "goosefish," "angler," or "fishing frog." In Maine it is the "monkfish," in Rhode Island the "bellows-fish," in eastern Connecticut the "molligut," and in South Carolina "allmouth." The early colonial writers refer to it as the "greedigut." It is also known as the "wide-gap," "kettle-maw," and "sea devil."' ~Unutilized fishes and their relation to the fishing industries, by Irving Angell Field.

Color photo of greediguts fish: http://www.marlin.ac.uk/imgs/o_loppis2.jpg

More about New England fish: http://www.narragansettbay.info/swgamefish.cfm

Massachusetts Bay underwater: http://www.mwra.state.ma.us/harbor/html/mb_images.htm

17th-century sea monsters: http://scolarcardiff.wordpress.com/2012/01/19/science-and-sea-monsters/

Published on February 05, 2013 22:07

January 20, 2013

Mary Dyer at Shelter Island: She ever shined in the image of God

Guest post © Johan Winsser

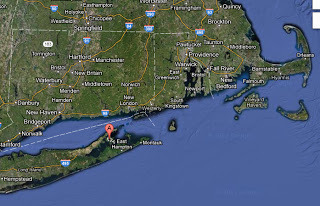

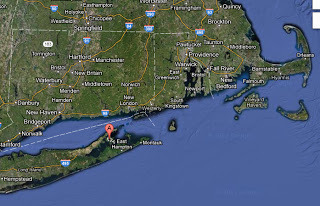

Shelter Island (marked) in relation to New England After spending the winter of 1659-60 witnessing to her faith on Long Island, Mary Dyer went in the early spring to Shelter Island, thinking to go from there back to Rhode Island. About seven miles in breadth and width, Shelter Island lies between the two peninsulas at the eastern end of Long Island. It was largely owned by Captain Nathaniel Sylvester, one of four wealthy Barbados sugar planters who in 1651 purchased the island from New Haven Colony, intending it as a station for their flourishing triangular trade between England, the West Indies, and New England.

Shelter Island (marked) in relation to New England After spending the winter of 1659-60 witnessing to her faith on Long Island, Mary Dyer went in the early spring to Shelter Island, thinking to go from there back to Rhode Island. About seven miles in breadth and width, Shelter Island lies between the two peninsulas at the eastern end of Long Island. It was largely owned by Captain Nathaniel Sylvester, one of four wealthy Barbados sugar planters who in 1651 purchased the island from New Haven Colony, intending it as a station for their flourishing triangular trade between England, the West Indies, and New England.

Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island

Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island

Photo courtesy of Johan Winsser

At Shelter Island, Sylvester gave succor to traveling and expelled Friends. Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick of Salem came to the island in the summer of 1659 after their harsh treatment at Boston. Being elderly and in frail health, Lawrence made his will and died there the next spring. His wife and yokefellow Cassandra followed three days later. William Robinson, who would die for his faith and principles on the Boston gallows in October 1659, was appointed one of the two overseers of Southwick’s will. No tombstones were erected for the Southwicks—not surprising since early Friends usually did not erect memorials to the dead, giving no nod to worldly vanity.

Quaker cemetery, Shelter Island

Quaker cemetery, Shelter Island

Photo courtesy of Johan Winsser In 1884 a four-sided monument to the early Friends who had visited the Island was erected in a quiet grove. Each step was inscribed as follows:

West Top Step – THE PURITAN AND HIS PRIDEWest middle step- OVERCOME BY THE FAITH OF THE QUAKERWest bottom step – GAVE CONCORD AND LEXINGTON AND BUNKER HILL TO HISTORY

South top step – DANIEL GOULD BOUND TO THE GUN CARRIAGE AND LASHEDSouth middle step – EDWARD WHORTON THE MUCH SCOURGEDSouth bottom step – CHRISTOPHER HOLDER THE MUTILATED

East top step - LAWRENCE AND CASSANDRA SOUTHWICKEast middle step- DESPOILED IMPRISIONED STARVED WHIPPED BANISHEDEast bottom step- WHO FLED HERE TO DIE

North top step – OF THE SUFFERINGS OF CONSCIENCE SAKE OF FRIENDS OF NATHANIEL SYLVESTER MOST OF WHOM SOUGHT SHELTER HERE INCLUDINGNorth middle step - GEORGE FOX FOUNDER OF THE SOCIETY OF QUAKERS AND OF HIS FOLLOWERSNorth bottom step - MARY DYER MARMADUKE STEVENSON AND WILLIAM ROBINSON WILLIAM LEDDRA WHO WERE EXECUTED ON BOSTON COMMON Zoom on northeastern part of Shelter Island, from Google Maps.

Zoom on northeastern part of Shelter Island, from Google Maps.

Quaker cemetery is close to head of Gardiners Creek.

When Dyer arrived, she found other Quakers already there and was warmly received. Like Elijah sojourning on the mountain before returning to confront Ahab, she decided to stay, to rest and reflect, waiting for the next clear command from God. A young Quaker, John Taylor, noted her arrival in his journal.

Shelter Island (marked) in relation to New England After spending the winter of 1659-60 witnessing to her faith on Long Island, Mary Dyer went in the early spring to Shelter Island, thinking to go from there back to Rhode Island. About seven miles in breadth and width, Shelter Island lies between the two peninsulas at the eastern end of Long Island. It was largely owned by Captain Nathaniel Sylvester, one of four wealthy Barbados sugar planters who in 1651 purchased the island from New Haven Colony, intending it as a station for their flourishing triangular trade between England, the West Indies, and New England.

Shelter Island (marked) in relation to New England After spending the winter of 1659-60 witnessing to her faith on Long Island, Mary Dyer went in the early spring to Shelter Island, thinking to go from there back to Rhode Island. About seven miles in breadth and width, Shelter Island lies between the two peninsulas at the eastern end of Long Island. It was largely owned by Captain Nathaniel Sylvester, one of four wealthy Barbados sugar planters who in 1651 purchased the island from New Haven Colony, intending it as a station for their flourishing triangular trade between England, the West Indies, and New England.

Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island

Sylvester Manor, Shelter IslandPhoto courtesy of Johan Winsser

At Shelter Island, Sylvester gave succor to traveling and expelled Friends. Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick of Salem came to the island in the summer of 1659 after their harsh treatment at Boston. Being elderly and in frail health, Lawrence made his will and died there the next spring. His wife and yokefellow Cassandra followed three days later. William Robinson, who would die for his faith and principles on the Boston gallows in October 1659, was appointed one of the two overseers of Southwick’s will. No tombstones were erected for the Southwicks—not surprising since early Friends usually did not erect memorials to the dead, giving no nod to worldly vanity.

Quaker cemetery, Shelter Island

Quaker cemetery, Shelter Island Photo courtesy of Johan Winsser In 1884 a four-sided monument to the early Friends who had visited the Island was erected in a quiet grove. Each step was inscribed as follows:

West Top Step – THE PURITAN AND HIS PRIDEWest middle step- OVERCOME BY THE FAITH OF THE QUAKERWest bottom step – GAVE CONCORD AND LEXINGTON AND BUNKER HILL TO HISTORY

South top step – DANIEL GOULD BOUND TO THE GUN CARRIAGE AND LASHEDSouth middle step – EDWARD WHORTON THE MUCH SCOURGEDSouth bottom step – CHRISTOPHER HOLDER THE MUTILATED

East top step - LAWRENCE AND CASSANDRA SOUTHWICKEast middle step- DESPOILED IMPRISIONED STARVED WHIPPED BANISHEDEast bottom step- WHO FLED HERE TO DIE

North top step – OF THE SUFFERINGS OF CONSCIENCE SAKE OF FRIENDS OF NATHANIEL SYLVESTER MOST OF WHOM SOUGHT SHELTER HERE INCLUDINGNorth middle step - GEORGE FOX FOUNDER OF THE SOCIETY OF QUAKERS AND OF HIS FOLLOWERSNorth bottom step - MARY DYER MARMADUKE STEVENSON AND WILLIAM ROBINSON WILLIAM LEDDRA WHO WERE EXECUTED ON BOSTON COMMON

Zoom on northeastern part of Shelter Island, from Google Maps.

Zoom on northeastern part of Shelter Island, from Google Maps. Quaker cemetery is close to head of Gardiners Creek.

When Dyer arrived, she found other Quakers already there and was warmly received. Like Elijah sojourning on the mountain before returning to confront Ahab, she decided to stay, to rest and reflect, waiting for the next clear command from God. A young Quaker, John Taylor, noted her arrival in his journal.

And there came several Friends from other Parts in New-England, to see us: One was Mary Dyer … She was a very Comely Woman and a Grave Matron, and eve[r] shined in the Image of God. We had several brave meetings there together, and the Lord’s Power and Presence was with us Gloriously.By May, as the days warmed, the osprey nested, the dogwood bloomed, and the gardens brightened with daffodils, lupines, and sweet peas, Dyer’s clear call had come. Her unwanted gallows reprieve last October enabled the Bay magistrates to avoid the only two choices she hoped to press upon them: repeal the bloody anti-Quakers laws or hang Mary Dyer. Furthermore, the reprieve allowed the magistrates another opportunity to dissemble about the Quakers. Any appearance of backing down from the tyranny of the Boston magistrates and ministers meant that the Quaker cause would be compromised. Dyer believed she had no choice but to go forward and put her life on the line again. Nothing less than a full revocation of those “bloody laws” could stay her course and spare her life.

__________________________ Johan Winsser has been researching and writing about Mary Dyer for many years. Some of his research is found on his DyerFarm website. Thank you, Johan, for your contributions to Dyer genealogy research, and to this Dyer blog.

John Taylor, An account of some of the Labours, exercises, Travels, and Perils, by SEA and LAND, of John Taylor of York: and also His DELIVERANCES; By way of Journal. London: J. Soule, 1710, 8.

Published on January 20, 2013 21:57

Shelter Island, Mary Dyer’s last earthly comfort

Guest post © Johan Winsser

Shelter Island (marked) in relation to New England After spending the winter of 1659-60 witnessing to her faith on Long Island, Mary Dyer went in the early spring to Shelter Island, thinking to go from there back to Rhode Island. About seven miles in breadth and width, Shelter Island lies between the two peninsulas at the eastern end of Long Island. It was largely owned by Captain Nathaniel Sylvester, one of four wealthy Barbados sugar planters who in 1651 purchased the island from New Haven Colony, intending it as a station for their flourishing triangular trade between England, the West Indies, and New England.

Shelter Island (marked) in relation to New England After spending the winter of 1659-60 witnessing to her faith on Long Island, Mary Dyer went in the early spring to Shelter Island, thinking to go from there back to Rhode Island. About seven miles in breadth and width, Shelter Island lies between the two peninsulas at the eastern end of Long Island. It was largely owned by Captain Nathaniel Sylvester, one of four wealthy Barbados sugar planters who in 1651 purchased the island from New Haven Colony, intending it as a station for their flourishing triangular trade between England, the West Indies, and New England.

Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island

Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island

Photo courtesy of Johan Winsser

At Shelter Island, Sylvester gave succor to traveling and expelled Friends. Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick of Salem came to the island in the summer of 1659 after their harsh treatment at Boston. Being elderly and in frail health, Lawrence made his will and died there the next spring. His wife and yokefellow Cassandra followed three days later. William Robinson, who would die for his faith and principles on the Boston gallows in October 1659, was appointed one of the two overseers of Southwick’s will. No tombstones were erected for the Southwicks—not surprising since early Friends usually did not erect memorials to the dead, giving no nod to worldly vanity.

Quaker cemetery, Shelter Island

Quaker cemetery, Shelter Island

Photo courtesy of Johan Winsser In 1884 a four-sided monument to the early Friends who had visited the Island was erected in a quiet grove. Each step was inscribed as follows:

West Top Step – THE PURITAN AND HIS PRIDEWest middle step- OVERCOME BY THE FAITH OF THE QUAKERWest bottom step – GAVE CONCORD AND LEXINGTON AND BUNKER HILL TO HISTORY

South top step – DANIEL GOULD BOUND TO THE GUN CARRIAGE AND LASHEDSouth middle step – EDWARD WHORTON THE MUCH SCOURGEDSouth bottom step – CHRISTOPHER HOLDER THE MUTILATED

East top step - LAWRENCE AND CASSANDRA SOUTHWICKEast middle step- DESPOILED IMPRISIONED STARVED WHIPPED BANISHEDEast bottom step- WHO FLED HERE TO DIE

North top step – OF THE SUFFERINGS OF CONSCIENCE SAKE OF FRIENDS OF NATHANIEL SYLVESTER MOST OF WHOM SOUGHT SHELTER HERE INCLUDINGNorth middle step - GEORGE FOX FOUNDER OF THE SOCIETY OF QUAKERS AND OF HIS FOLLOWERSNorth bottom step - MARY DYER MARMADUKE STEVENSON AND WILLIAM ROBINSON WILLIAM LEDDRA WHO WERE EXECUTED ON BOSTON COMMON Zoom on northeastern part of Shelter Island, from Google Maps.

Zoom on northeastern part of Shelter Island, from Google Maps.

Quaker cemetery is close to head of Gardiners Creek.

When Dyer arrived, she found other Quakers already there and was warmly received. Like Elijah sojourning on the mountain before returning to confront Ahab, she decided to stay, to rest and reflect, waiting for the next clear command from God. A young Quaker, John Taylor, noted her arrival in his journal.

Shelter Island (marked) in relation to New England After spending the winter of 1659-60 witnessing to her faith on Long Island, Mary Dyer went in the early spring to Shelter Island, thinking to go from there back to Rhode Island. About seven miles in breadth and width, Shelter Island lies between the two peninsulas at the eastern end of Long Island. It was largely owned by Captain Nathaniel Sylvester, one of four wealthy Barbados sugar planters who in 1651 purchased the island from New Haven Colony, intending it as a station for their flourishing triangular trade between England, the West Indies, and New England.

Shelter Island (marked) in relation to New England After spending the winter of 1659-60 witnessing to her faith on Long Island, Mary Dyer went in the early spring to Shelter Island, thinking to go from there back to Rhode Island. About seven miles in breadth and width, Shelter Island lies between the two peninsulas at the eastern end of Long Island. It was largely owned by Captain Nathaniel Sylvester, one of four wealthy Barbados sugar planters who in 1651 purchased the island from New Haven Colony, intending it as a station for their flourishing triangular trade between England, the West Indies, and New England.

Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island

Sylvester Manor, Shelter IslandPhoto courtesy of Johan Winsser

At Shelter Island, Sylvester gave succor to traveling and expelled Friends. Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick of Salem came to the island in the summer of 1659 after their harsh treatment at Boston. Being elderly and in frail health, Lawrence made his will and died there the next spring. His wife and yokefellow Cassandra followed three days later. William Robinson, who would die for his faith and principles on the Boston gallows in October 1659, was appointed one of the two overseers of Southwick’s will. No tombstones were erected for the Southwicks—not surprising since early Friends usually did not erect memorials to the dead, giving no nod to worldly vanity.

Quaker cemetery, Shelter Island

Quaker cemetery, Shelter Island Photo courtesy of Johan Winsser In 1884 a four-sided monument to the early Friends who had visited the Island was erected in a quiet grove. Each step was inscribed as follows:

West Top Step – THE PURITAN AND HIS PRIDEWest middle step- OVERCOME BY THE FAITH OF THE QUAKERWest bottom step – GAVE CONCORD AND LEXINGTON AND BUNKER HILL TO HISTORY

South top step – DANIEL GOULD BOUND TO THE GUN CARRIAGE AND LASHEDSouth middle step – EDWARD WHORTON THE MUCH SCOURGEDSouth bottom step – CHRISTOPHER HOLDER THE MUTILATED

East top step - LAWRENCE AND CASSANDRA SOUTHWICKEast middle step- DESPOILED IMPRISIONED STARVED WHIPPED BANISHEDEast bottom step- WHO FLED HERE TO DIE

North top step – OF THE SUFFERINGS OF CONSCIENCE SAKE OF FRIENDS OF NATHANIEL SYLVESTER MOST OF WHOM SOUGHT SHELTER HERE INCLUDINGNorth middle step - GEORGE FOX FOUNDER OF THE SOCIETY OF QUAKERS AND OF HIS FOLLOWERSNorth bottom step - MARY DYER MARMADUKE STEVENSON AND WILLIAM ROBINSON WILLIAM LEDDRA WHO WERE EXECUTED ON BOSTON COMMON

Zoom on northeastern part of Shelter Island, from Google Maps.

Zoom on northeastern part of Shelter Island, from Google Maps. Quaker cemetery is close to head of Gardiners Creek.

When Dyer arrived, she found other Quakers already there and was warmly received. Like Elijah sojourning on the mountain before returning to confront Ahab, she decided to stay, to rest and reflect, waiting for the next clear command from God. A young Quaker, John Taylor, noted her arrival in his journal.

And there came several Friends from other Parts in New-England, to see us: One was Mary Dyer … She was a very Comely Woman and a Grave Matron, and eve[r] shined in the Image of God. We had several brave meetings there together, and the Lord’s Power and Presence was with us Gloriously.By May, as the days warmed, the osprey nested, the dogwood bloomed, and the gardens brightened with daffodils, lupines, and sweet peas, Dyer’s clear call had come. Her unwanted gallows reprieve last October enabled the Bay magistrates to avoid the only two choices she hoped to press upon them: repeal the bloody anti-Quakers laws or hang Mary Dyer. Furthermore, the reprieve allowed the magistrates another opportunity to dissemble about the Quakers. Any appearance of backing down from the tyranny of the Boston magistrates and ministers meant that the Quaker cause would be compromised. Dyer believed she had no choice but to go forward and put her life on the line again. Nothing less than a full revocation of those “bloody laws” could stay her course and spare her life.

__________________________ Johan Winsser has been researching and writing about Mary Dyer for many years. Some of his research is found on his DyerFarm website. Thank you, Johan, for your contributions to Dyer genealogy research, and to this Dyer blog.

John Taylor, An account of some of the Labours, exercises, Travels, and Perils, by SEA and LAND, of John Taylor of York: and also His DELIVERANCES; By way of Journal. London: J. Soule, 1710, 8.

Published on January 20, 2013 21:57

January 6, 2013

Puritan baby names of the 17th century

© Christy K Robinson

A baby-christening party, 1629, Flemish.

A baby-christening party, 1629, Flemish. The mother lies recovering in the cupboard bed

at the rear, where two women are holding a baby in white. In Western culture, we know people with virtue names such as Hope, Faith, Irene, Zoe, and Joy, and those with biblical names like John, David, Jacob, Esther, Naomi, Mary, and scores of others. From ancient times, parents all over the world have named their children with religiously-significant meanings or prophecies in mind, names that would be something to live up to, names that could form a child's character and destiny. Many named their babies after kings, queens, and nobility, or after parents and other family members.

I christen thee "Flee-Fornication"

I christen thee "Flee-Fornication" and thy twin, "Sorry For Sin." William and Mary Dyer named their children in this manner. William’s father was William, Mary’s brother was William (which means her father was probably William), and they named their firstborn William. He died within a day or two of birth, and a later son was named William—that one became a savior of his mother’s life in 1659, and later was mayor of New York. They named one son Samuel (“Asked For”), another son Charles after the recently-executed king, another son Henry (probably after Sir Henry Vane), a daughter Mary, and a son Mahershallalhashbaz. Oh, yes! It was shortened to Maher, but the name was bestowed based on Isaiah 8:4, after the death of their friend and mentor, Anne Hutchinson.

Only in the last few hundred years have children been named for popular figures or in an attempt to make unique sounds or word combinations.

In the late 16th and throughout the 17thcenturies, the Reformation gained ground in England, and splintered further when non-conformists insisted on “purifying” the Church of England. There was a large pocket of Puritans (as one branch of non-conformists was known) in Essex, and they tended to name their children with virtue names. I found a list of jury men in a PDF, with given names, followed by a comma and their surnames.

That's right, a grown man had lived his life thus far with the name, "Kill Sin Pimple." Thousands of Puritan emigrants to New England came from Essex, including Governor John Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay Colony. So many of them left England with money and possessions that the government of King Charles I believed that the English economy would fail. Eight ships were stopped in the River Thames in 1634, and the emigrants were prohibited from leaving. Among the passengers was Oliver Cromwell, bound for Connecticut—who would make war on the royalists in less than 10 years, and have King Charles beheaded in 15 years.

The Puritans of England and America—self-described as the Remnant or Elect in the book of Revelation— thought that the “world” was evil and they were living in the last days (indeed, deadly plagues and famines, religious wars, economic depression, and vicious crime regularly swept Europe), and Jesus would come in his second advent, in their lifetime, to take them to heaven and destroy the earth. Some of their names reflect that apocalyptic expectation: Return, Hope For, Redeemed, The-Lord-is-Near, and Wayte-a-While. Most of the Puritan emigrants to New England believed that the civilization they’d build would be a New Jerusalem, and these faithful ones would be hastening the Second Coming with their passion for perfection in keeping Old Testament laws. That was the reasoning behind the marriage of civil and ecclesiastical (blend of state and church) law. It wasn’t enough to live the sanctified life oneself. Oh, no. They were part of a larger community, and the entire community must conform to the law, or God would withhold his blessings, leave them in the dust, and rain down curses. A familiar story in this decade, don’t you think?

Church members were encouraged to report those who didn’t conform, or those who spoke against authorities, which was considered sedition. Hate-Evil, Obedience, and Zeal-for-the-Lord might be appropriate names given by families who believed that. The charge of sedition (for signing a mild remonstrance against the governor and assistants) prompted punishment and exile for about 75 families, including William and Mary Dyer and Anne and William Hutchinson. They purchased Aquidneck Island (later Rhode Island) from the Narragansett Indians and founded Portsmouth in 1638 and Newport in 1639. Massachusetts Puritans scornfully referred to the new colony as the Isle of Error or Rogues Island.

Most of the awkward names faded away with the English Civil Wars, replaced by virtue names such as Purity, Patience, and Faith. The vast majority of names we find in colonial archives and genealogies are what we’d consider “normal” names: names we still use 400 years later.

Published on January 06, 2013 00:03

January 1, 2013

In the tempest, power

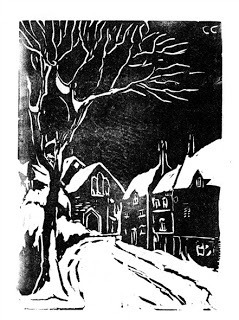

Ada Bottesfordian, 1951.

Ada Bottesfordian, 1951.18 Winter Street. George Fox on Winter

"And Friends, though you may have tasted of the power and been convinced and have felt the light, yet afterwards you may feel winter storms, tempests, and hail, and be frozen, in frost and cold and a wilderness and temptations. Be patient and still in the power and still in the light that doth convince you, to keep your minds to God; in that be quiet, that you may come to the summer, that your flight be not in the winter. For if you sit still in the patience which overcomes in the power of God, there will be no flying. For the husbandman, after he hath sown his seed, he is patient. For by the power and by the light you will come to see through and feel over winter storms, tempests, and all the coldness, barrenness, emptyness. And the same light and power will go over the tempter’s head, which power and light were before he was. And so in the light standing still you will see your salvation, you will see the Lord’s strength, you will feel the small rain, you will feel the fresh springs . . ."

Thanks to the Hay Quaker blog by Ray Lovegrove, for this lovely quote and provision of the artwork.

George Fox, 1624-1691, was founder of the movement Society of Friends, which came to be called Quakers. Mary Dyer was "convinced" of their beliefs in the 1650s, and gave her life to stop the deadly persecution of Quakers in New England.

Published on January 01, 2013 23:00

December 19, 2012

Oliver Cromwell Cancels Christmas

William and Mary Dyer were citizens of Great Britain who emigrated to New England in 1635 and co-founded the colony of Providence Plantations and Rhode Island in 1638. They were born during the reign of King Charles I, lived under Cromwell’s rule in the 1640s and 1650s, and after Mary died in 1660, William lived during the reign of Charles II.

Guest post © Sarah Butterfield, used by permissionOriginally published on Sarah’s History, 18 December 2012

“It’s only seven sleeps until Christmas Day!” was my dawn chorus this morning. Tomorrow six, the next day five... My three children will be practically exploding with excitement on Christmas Eve as they go to bed full of anticipation for the wonderful day that lies ahead of them when they wake up in the morning. Christmas Day is, for those that celebrate it, a day of present exchanging, feasting and having fun. Imagine, then, if all of that was taken away.

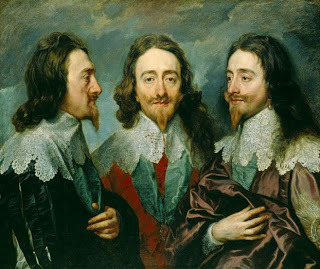

Charles I triple portrait,

Charles I triple portrait, painted by Anthony Van Dyke

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms in seventeenth-century Britain were a desperately unsettling time for the common people, as were the events that took place before them. Charles I believed in his divine right to rule very passionately, ruling without parliament for more than a decade. He also taxed his people to breaking point; enforcing ship money in peacetime away from coastal areas was one of his more unpopular moves. His poor rule over England and Scotland was one of the many complex reasons civil war broke out between the crown and parliament in the summer of 1642. At the same time, a form of Protestant Christianity known as puritanism was on the rise. Puritans believed in the simplicity of faith. To them, Christmas (among other celebrations) was an unnecessary Roman Catholic tradition; they disapproved of celebrating the feast day, and the gluttony, frivolity and excess that came with. In 1642, dedicated puritan soldiers and members of parliament did not celebrate Christmas.

In 1643, the threat towards Christmas was more severe. The parliamentarian leaders had signed a treaty with the Scottish in the autumn, sealing themselves military support against the royalist army of Charles I. As part of this treaty, parliament promised to further reform religion in England, bringing the faith of England closer to that of Scotland. The Scottish had been practicing presbyterianism, another form of simple faith, as their national religion for several decades. In the late sixteenth century Christmas festivities had been stopped (save for a brief spell beginning in 1617 when James I reinstated them), and now England were expected to follow suit.

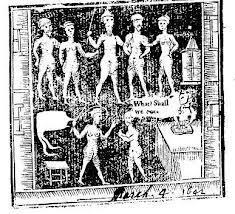

“Love one another: A Tub Lecture Preached”

“Love one another: A Tub Lecture Preached” by John Taylor, warned that

Parliamentarian puritans

were a threat to the

celebration of Christmas

in January 1643.

The English puritans followed the Scottish Presbyterian lead, treating Christmas Day in 1643 as a day like any other. Shops were opened and church doors closed. Puritan members of parliament went to work at the Houses of Parliament, leading where they expected subjects to follow. John Taylor’s satirical pamphlet ‘Tub Lecture,’ published earlier that year, had become a gloomy reality. Still, the civil war could have gone either way, and Christmas wasn’t legally banned—yet.

In 1644, the non-celebration of Christmas became more extreme again, as the feast day clashed with a puritan fast day. Members of parliament favoured the fast over the feast; remembering their own sins as well as the sins of their ancestors for indulging themselves during the twelve days of Christmas. Parliamentary power was ever increasing by this time, and Charles’ power slipping away.

Oliver Cromwell,

Oliver Cromwell, successful soldier,

parliamentarian and Puritan Christmas 1645 was equally, if not more solemn than that of the year before. In 1645, Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Fairfax had created their New Model Army. Their army was structured, disciplined and puritan in the extreme. In addition to these qualities the army was incredibly powerful, and all but destroyed Charles’ royalist forces during two crucial battles—Naseby and Langport—that summer. Charles was captured and handed over to the Parliamentarian army. Decisions were to be made about Charles’ status now, but one thing was sure in the minds of parliament; they had won the war. Charles would be their puppet ruler. Earlier in 1645, parliament had issued their alternative to the Book of Common Prayer, ‘The New Directory for the Worship of God’; the book did not mention Christmas at all. With the king defeated, Christmas was gone. It was noted that man could walk the streets on Christmas Day in 1645, and have no idea that it was a Holy feast day.

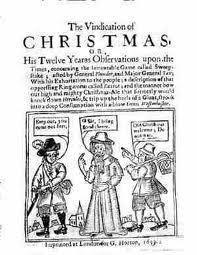

John Taylor published another

John Taylor published another pamphlet in 1652, titled

“The Vindication of Christmas,”

supporting the continuing

celebration of Christmas. Still, England’s Anglican subjects did not want to give up Christmas without a fight. John Taylor published another pro-Christmas pamphlet, ‘Complaint of Christmas’, persuading his fellow Christian men to continue celebrating Christmas in defiance of parliament. This the people did, and more besides. On Christmas Day 1546 men celebrated as normal, and attacked local tradesmen who had opened their shops for business as if it were a normal day.

June 1647 saw an act pass through parliament. Christmas was now a banned celebration, and anyone caught celebrating could be lawfully punished. This act was highly unpopular throughout the country, and sparked the pro-Christmas riots that erupted all over the country on Christmas Day that year. Holly was hung in blatant defiance of the new law. Shops that were open for business were attacked and smashed to pieces and men were killed.

Shortly after Christmas Day in 1647, Charles I opened communication with the Scottish to free himself from captivity and rule in his own way again. This sparked a second English civil war between parliament and crown; this time, however, the conflict was short lived and parliament enjoyed a decisive victory the following August. Christmas 1648 passed with Charles imprisoned and parliament in charge. In January 1649, Charles was tried, found guilty and executed for high treason against his country. The war was over, and Christmas was gone. The parliamentary ban of Christmas held fast, with Oliver Cromwell continuing the law after he was named Lord Protector of England in 1653. Of course, just because Christmas was banned didn’t mean people didn’t celebrate it. They just did so in secrecy.

Charles II: The king who brought back Christmas!

Charles II: The king who brought back Christmas!In September 1658, Oliver Cromwell died and was replaced as Lord Protector by his son, Richard. (Interesting move for a man who was against the hereditary monarchy, but that’s a moan for another day.) Richard was an unsuccessful Lord Protector, and the people of England decided they wanted a monarch after all. Charles II was recalled from exile and restored to the throne in 1660. He brought with him the restoration of Christmas, which was a hugely popular and successful move. Hurrah for Charles II! No wonder he was such a popular king.

__________________ Further Reading-

“The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700″ by Ronald Hutton, Oxford University Press, 1994.

“Cromwell: Our Chief of Men” by Antonia Fraser, Phoenix Books, 2008.

“The English Civil Wars” by Blair Worden, Phoenix Books, 2009.

PS: I know it wasn’t technically all Cromwell’s fault, I just thought that title sounded pretty cool._____________ Sarah Butterfield is a history student living in Derbyshire, England. Visit her blog, Sarah’s History, for her studies in English history.

Published on December 19, 2012 00:38

December 12, 2012

Enlightened

This post was written for the Viriditas blog of Mary Sharratt, author of Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen, in a series on Light and Advent, December 2012. My article is an opinion piece on Light, not intended to tell the entire story of Mary Barrett Dyer. The theological concepts are complicated and I've simplified them here.

© Christy K. Robinson

Mary Dyer sculpture at Boston.

Mary Dyer sculpture at Boston.

Photo by Eric Pettee, used by permission.

If you know of Mary Barrett Dyer, perhaps it’s the memorial statue at the Massachusetts State House; or that she was the Quaker woman hanged in Boston in 1660.

Mary was born in London at the time the King James Bible was published, and was admired for her intellectual, spiritual, and physical beauty. She and William Dyer were married under Anglican liturgy at St. Martin-in-the-Fields, but in 1635, they emigrated to ultra-Puritan Boston in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and were immediately admitted to membership in the First Church. (Some people committed suicide because their membership was denied.) The Dyers had to conform to Puritan ways to be accepted so quickly. However, Governor Winthrop observed that Mary was “addicted to revelations.”

Mary became a disciple of Anne Hutchinson, a religious dissident who claimed that God revealed insights about scripture to her—a “weak-minded” (but highly-educated) woman. She pointed out that instead of trying in vain to earn salvation by perfectly keeping the law, believers were set free from eternal damnation by God’s grace. They could trust divine leading in their conscience, with no need for intercessors or interpreters.

But the Puritan theocracy believed if every man did as he pleased, all would be anarchy. After several ecclesiastical trials, the Hutchinsons and Dyers and about 75 Massachusetts families were exiled for sedition and heresy. They purchased Rhode Island from the Indians, and founded a new colony in 1638.

Mary visited England in early 1652, where she observed several new religious movements, including the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). In some respects similarly to Anne Hutchinson, the Friends believed that Old Testament laws were obsolete, and had been replaced by God’s voice in the individual’s conscience, which was revealed during times of silent reflection and worship. They experienced God as Light and overwhelming Love, in contrast to the vengeful Judge who predestined only certain people for eternal life. Some of the scripture they quoted included:

God is light; in him there is no darkness at all. … If we walk in the light, as he is in the light, we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of Jesus, his Son, purifies us from all sin. 1 John 1:5-7. Believe in the light while you have the light, so that you may become children of light. ~Jesus. John 12:36. “For you were once darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Live as children of light.” Ephesians 5:8In 1657, Mary returned to America, was accused of being a Quaker, and was cast into Boston’s prison for weeks before William Dyer learned of it and rescued her. Thus began three years of Mary’s repeatedly defying religious oppression to gain relief and freedom for the violently persecuted.

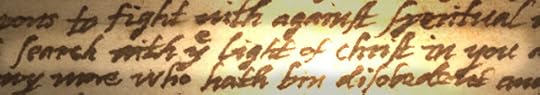

Quakers in New England were fined, beaten, branded, whipped with a knotted cord, banished, tied to carts and dragged from town to town, imprisoned without food or heat in winter, and banished “on pain of death” for their efforts and beliefs. Those severe persecutions only made them more determined to share the Light.For supporting Quakers, Mary was arrested and imprisoned at least five times. Finally, she was sentenced to death. She wrote a letter to the General Court on the night before her execution date. “I therefore declare that in the fear, peace, and love of God I came … and have found such favor in his sight as to offer up my life freely for his truth and people’s sakes. If this life were freely granted by you, it would not avail me to accept it from you, so long as I shall daily hear or see the suffering of my dear brethren and sisters.” Mary Dyer's handwriting. Letter to the General Court, October 1659. She believed that her death would be so shocking to the public that it would bring about the end of the severe tortures and repression of Quakers by the Puritan leaders. Many Puritans sympathized with and helped Quakers, and had begun to turn away from their harsh government. Fearing unrest, the court granted a reprieve when she was on the gallows. She was imprisoned in Plymouth two weeks later, spent the winter at Long Island, then deliberately returned to Boston seven months later—to obey God’s command, and commit civil disobedience.

Mary Dyer's handwriting. Letter to the General Court, October 1659. She believed that her death would be so shocking to the public that it would bring about the end of the severe tortures and repression of Quakers by the Puritan leaders. Many Puritans sympathized with and helped Quakers, and had begun to turn away from their harsh government. Fearing unrest, the court granted a reprieve when she was on the gallows. She was imprisoned in Plymouth two weeks later, spent the winter at Long Island, then deliberately returned to Boston seven months later—to obey God’s command, and commit civil disobedience.

She was again condemned to death, and was hanged on June 1, 1660. Because her vengeful former pastor offered a cloth to cover her face, I believe that the Light was strong on her countenance.

Mary’s sacrifice was successful. Her letters were presented posthumously to Charles II, who ended executions for religious offenses. Her husband and close friends had significant influence on the 1663 Rhode Island royal charter of liberties that granted freedom of conscience to worship (or not), and retained separation of church and state. The charter was a model for the US Constitution’s Bill of Rights, which has in turn been the beacon of light for constitutions around the world.

The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. John 1:5.

© Christy K. Robinson

Mary Dyer sculpture at Boston.

Mary Dyer sculpture at Boston. Photo by Eric Pettee, used by permission.

If you know of Mary Barrett Dyer, perhaps it’s the memorial statue at the Massachusetts State House; or that she was the Quaker woman hanged in Boston in 1660.

Mary was born in London at the time the King James Bible was published, and was admired for her intellectual, spiritual, and physical beauty. She and William Dyer were married under Anglican liturgy at St. Martin-in-the-Fields, but in 1635, they emigrated to ultra-Puritan Boston in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and were immediately admitted to membership in the First Church. (Some people committed suicide because their membership was denied.) The Dyers had to conform to Puritan ways to be accepted so quickly. However, Governor Winthrop observed that Mary was “addicted to revelations.”

Mary became a disciple of Anne Hutchinson, a religious dissident who claimed that God revealed insights about scripture to her—a “weak-minded” (but highly-educated) woman. She pointed out that instead of trying in vain to earn salvation by perfectly keeping the law, believers were set free from eternal damnation by God’s grace. They could trust divine leading in their conscience, with no need for intercessors or interpreters.

But the Puritan theocracy believed if every man did as he pleased, all would be anarchy. After several ecclesiastical trials, the Hutchinsons and Dyers and about 75 Massachusetts families were exiled for sedition and heresy. They purchased Rhode Island from the Indians, and founded a new colony in 1638.

Mary visited England in early 1652, where she observed several new religious movements, including the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). In some respects similarly to Anne Hutchinson, the Friends believed that Old Testament laws were obsolete, and had been replaced by God’s voice in the individual’s conscience, which was revealed during times of silent reflection and worship. They experienced God as Light and overwhelming Love, in contrast to the vengeful Judge who predestined only certain people for eternal life. Some of the scripture they quoted included:

God is light; in him there is no darkness at all. … If we walk in the light, as he is in the light, we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of Jesus, his Son, purifies us from all sin. 1 John 1:5-7. Believe in the light while you have the light, so that you may become children of light. ~Jesus. John 12:36. “For you were once darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Live as children of light.” Ephesians 5:8In 1657, Mary returned to America, was accused of being a Quaker, and was cast into Boston’s prison for weeks before William Dyer learned of it and rescued her. Thus began three years of Mary’s repeatedly defying religious oppression to gain relief and freedom for the violently persecuted.

Quakers in New England were fined, beaten, branded, whipped with a knotted cord, banished, tied to carts and dragged from town to town, imprisoned without food or heat in winter, and banished “on pain of death” for their efforts and beliefs. Those severe persecutions only made them more determined to share the Light.For supporting Quakers, Mary was arrested and imprisoned at least five times. Finally, she was sentenced to death. She wrote a letter to the General Court on the night before her execution date. “I therefore declare that in the fear, peace, and love of God I came … and have found such favor in his sight as to offer up my life freely for his truth and people’s sakes. If this life were freely granted by you, it would not avail me to accept it from you, so long as I shall daily hear or see the suffering of my dear brethren and sisters.”

Mary Dyer's handwriting. Letter to the General Court, October 1659. She believed that her death would be so shocking to the public that it would bring about the end of the severe tortures and repression of Quakers by the Puritan leaders. Many Puritans sympathized with and helped Quakers, and had begun to turn away from their harsh government. Fearing unrest, the court granted a reprieve when she was on the gallows. She was imprisoned in Plymouth two weeks later, spent the winter at Long Island, then deliberately returned to Boston seven months later—to obey God’s command, and commit civil disobedience.

Mary Dyer's handwriting. Letter to the General Court, October 1659. She believed that her death would be so shocking to the public that it would bring about the end of the severe tortures and repression of Quakers by the Puritan leaders. Many Puritans sympathized with and helped Quakers, and had begun to turn away from their harsh government. Fearing unrest, the court granted a reprieve when she was on the gallows. She was imprisoned in Plymouth two weeks later, spent the winter at Long Island, then deliberately returned to Boston seven months later—to obey God’s command, and commit civil disobedience.She was again condemned to death, and was hanged on June 1, 1660. Because her vengeful former pastor offered a cloth to cover her face, I believe that the Light was strong on her countenance.

Mary’s sacrifice was successful. Her letters were presented posthumously to Charles II, who ended executions for religious offenses. Her husband and close friends had significant influence on the 1663 Rhode Island royal charter of liberties that granted freedom of conscience to worship (or not), and retained separation of church and state. The charter was a model for the US Constitution’s Bill of Rights, which has in turn been the beacon of light for constitutions around the world.

The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. John 1:5.

Published on December 12, 2012 12:13

November 22, 2012

How the English colonists celebrated thanksgiving

© Christy K. Robinson

In 1630, the first ripples of the Great Migration brought small convoys of ships from England to Massachusetts Bay after ten to twelve arduous weeks at sea, where they prevailed despite adverse winds and stale and insect-infested food. These were the Winthop Fleet, named for their governor, John Winthrop, and they had left families, farms, and inheritance to found a New Jerusalem and usher in the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

They fought winds and tides to sail south along the islands and shoals of Maine to Cape Ann, to find the Endecott party at Salem, who had sailed there in 1628-29 and were supposed to have built houses and planted crops for the 1630 emigrants. But what the Winthrop Fleet, who were hungry and sick, found when they reached Salem, was a village of miserable huts, its residents politely but alarmingly asking if the new arrivals had any food to share. Half the Endecott party were dead or dying, and now the Winthrop party began to die of fevers or scurvy. When they arrived in early July, it was too late to plow and plant for the autumn which came in August and the winter which would come in early October. The fleet staggered into harbor between late June and mid-August. Winthrop’s second son, Henry, had drowned in a river almost immediately upon arriving in Massachusetts in early July.

When a ship arrived safely at Cape Ann, John Winthrop wrote in his journal on Thursday, August 8, 1630, “We kept a day of thanksgiving in all the plantations.”

On thanksgiving days, non-essential work and commerce was prohibited, and families and servants were required to attend church services for hours. It was a day for solemn, agonizing prayer and soul-searching to discover hidden sin and confess it, so that God’s wrath would be appeased and he would not withhold his blessing from his recalcitrant children.

Thanksgiving was not a feast day. It was a fast day. Thanksgiving was a day of sorrow, to repent, to turn away from a sinful, rebellious life and return to God’s grace. It wasn’t enough for an individual person to repent—they were the Church, the body of Christ, and repentance and atonement were important for the entire community. They didn’t conceive of “rugged American individualism” at this time. They were wed to Christ and one another. Unmarried people were not permitted to live alone—they were placed in families. Wilderness pioneers were up to no good. In Plymouth Colony, a family tried to build a farm out in the woods by themselves, but were brought back by court order to live in community for the good of all.

Thanksgiving was not a feast day. It was a fast day. Thanksgiving was a day of sorrow, to repent, to turn away from a sinful, rebellious life and return to God’s grace. It wasn’t enough for an individual person to repent—they were the Church, the body of Christ, and repentance and atonement were important for the entire community. They didn’t conceive of “rugged American individualism” at this time. They were wed to Christ and one another. Unmarried people were not permitted to live alone—they were placed in families. Wilderness pioneers were up to no good. In Plymouth Colony, a family tried to build a farm out in the woods by themselves, but were brought back by court order to live in community for the good of all. In 1630, the majority of the Winthrop Fleet arrivals stayed in Massachusetts, though they couldn’t be supported in Salem as hoped: they needed fresh water. They scouted on foot, and planted the Dudley group at Charlestown, and the Winthrop group nearby at Boston. Some of the intended colonists returned to England, but the passengers faced piracy, broken masts, and even greater privation on the way back to “Babylon,” which was experiencing another wave of bubonic plague.

The ones who stayed in America lived in dugout shelters, tents, and cabins that resembled stables—and this was during the Little Ice Age, when they experienced severe winters with frozen bays. They had few stored provisions, no grain, no vegetables or fruit. The Plymouth colony (the Pilgrims) helped as they could, and the few Indians who hadn’t moved to their winter camps traded bits of Indian corn and venison, and dried fish. This season was the Starving Time.

On the 11th of February 1631, when “great drifts of ice” floated in Boston Harbor, a sentry spotted the Lyon, one of the ships of the Massachusetts Bay Company, lying at anchor nearby. The ship’s master had rushed home to England, filled up with foodstuffs, and sailed back across the dangerous North Atlantic in winter (almost unheard-of because of the severity of storms), to relieve the suffering at the Bay.

John Winthrop wrote: “The poorer sort of people (who lay long in tents, etc.) were much afflicted with the scurvy, and many died, especially at Boston and Charlestown; but when this ship came and brought store of juice of lemons, many recovered speedily. It hath been always observed here, that such as fell into discontent, and lingered after their former conditions in England, fell into the scurvy and died.”

In other words, those who regretted leaving the comforts of Babylon for the privations of New Jerusalem, were more prone to disease and death. Scurvy is a wasting disease caused by lack of Vitamin C.

Winthrop’s Journal, Feb. 22, 1631: “We held a day of thanksgiving for this ship's arrival, by order from the governor and council, directed to all the plantations.”

On Nov. 2, 1631, the Lyonarrived again with important people, including the Winthrop family, Rev. John Wilson (who would baptize the Dyers’ son Samuel in 1635 and revile Mary Dyer at her execution), Isaac Robinson (son of the Pilgrim pastor, Rev. John Robinson), etc., and food to last them the winter. On Nov. 11, Boston held a day of thanksgiving.

Many times throughout the 1630s and 1640s, Winthrop wrote of holding fast days and thanksgivings. Ironically, when famine and disease came upon the Bostonians, the governor, magistrates, and ministers would call a fast day to confess the sins they and their neighbors must have committed to deserve all the disasters which befell them.

Thursdays were the days when people were required to attend church services for teaching, and when courts would schedule the punishment of sex offenders, thieves, and (ahem) church members who neglected regular attendance, with time in the stocks and/or public whipping. Mary Dyer’s first execution date, October 27, 1659, was a Thursday. Her two Quaker friends were hanged; she was reprieved. Then the people who had come to town for the “festival” went to church, no doubt to hear sermons and lectures related to the just judgments of God and the courts. Days of thanksgiving, called “public days,” were also set for Thursdays.