Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 16

November 16, 2013

The Bay Psalm Book, sung in the key of H-sharp

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

In New England, where the Dyers lived after 1635, there were no church organs—organs being related to the hated Catholic mass, and drawing attention away from God and to the skills of the performer. At Sabbath meetings of the Massachusetts Bay churches, they sang psalms without musical accompaniment.

Rev. John Cotton, Teacher of the Boston First Church of Christ (Congregational), disapproved of (though did not completely disavow) the use of instruments in worship. Cotton said about music: “We also grant that any private Christian who hath a gifte to frame a spirituall song may both frame it and sing it privately for his own private comfort and remembrance of some speciall benefit or deliverance. Nor doe we forbid the use any instrument therewithal: so that attention to the instrument does not divert the heart from attention to the matter of the song.”

He’s speaking of music composition and musical accompaniment in a private setting, not in public worship at the meetinghouse. At the meetinghouse, it was strictly a capella for many decades.

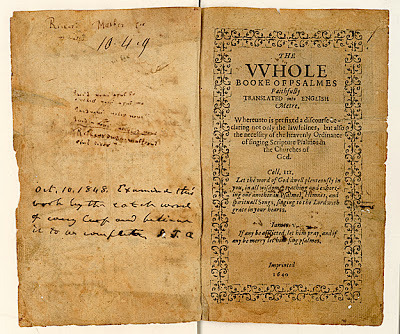

In 1640, three ministers published the first book in the American colonies: a psalter called The Bay Psalm Book that they approved for use in the churches of Massachusetts Bay. It was a text of psalms in rhyme, translated from Hebrew, without musical notation because almost no one was musically literate.

The three principal authors were Rev. Richard Mather (a very conservative Puritan minister), Rev. John Eliot (best known for his missionary work with Native Americans), and Rev. Thomas Welde (who wrote the lurid introduction to Gov. Winthrop’s book on Anne Hutchinson’s theology—the description of Mary Dyer’s “monster” baby, and he established the child-labor trafficking scheme).

Rev. Cotton wrote in the 1647 tract, Singing of Psalms as a Gospel Ordinance, “Wee lay downe this conclusion for a Doctrine of Truth. That singing of Psalms with a lively voyce is an holy Duty of God’s worship now in the dayes of the New Testament. When we say, singing with lively voyce, we suppose none will so farre misconstrue us as to thinke wee exclude singing with the heart; for God is a Spirit: and to worship him with the voice without the spirit were but lip-labour, which (being rested in) is but lost labour (Isa. xxix.13), or at most profiteth but little (Tim. iv. 8). But this wee say. As wee are to make melody in our hearts, so in our voyces also. In opposition to this there be some Anti-psalmists who doe not acknowledge any singing at all with the voyce in the New Testament, but onely spirituall songs of joy and comfort of the heart in the word of Christ.”

Like the subject and writing style of this article?

Like the subject and writing style of this article? You'll love this Kindle book of 17th-century

life and times surrounding William and Mary Dyer,

written by Christy K Robinson, author of

this blog.

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00G8GT830

In a short time, congregations forgot the tunes, and each singer sang in his or her own key, melody, and rhythm. (Perhaps something like a “Happy Birthday” cacophony today.)

Thomas Walter wrote at the end of the 17th century: "The tunes are now miserably tortured and twisted and quavered, in some churches, into a medly of confused and disorderly voices. Our tunes are left to the mercy of every unskillful throat to chop and alter, to twist and change... No two men in the Congregation quaver alike or together, it sounds in the ear of a good judge like five hundred different tunes roared out at the same time with perpetual interferings with one another." Source: Puritans at Play: Leisure and Recreation in Colonial New England, by Bruce C. Daniels, p. 54.

************

Read more: Let Bidding Begin for the Bay Psalm Book From 1640 By JAMES BARRON Published: November 15, 2013

David N. Redden recited the opening of the 23rd Psalm the way he had memorized it as a child: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures.”

Document A Closer Look at a Centuries-Old Text

Then he opened a weathered little book and read the version it contained: “The Lord to mee a ∫hepheard is, want therefore ∫hall not I. Hee in the fold∫ of tender-gra∫∫e, doth cau∫e mee downe to lie.”

Those lines were in a volume published in Massachusetts in 1640 that amounted to the Puritans’ religious and cultural manifesto. It was the first book printed in the colonies, and the first book printed in English in the New World. The locksmith who ran the hand-operated press turned out roughly 1,700 copies. The one in Mr. Redden’s hands is one of only 11 known to exist.

Mr. Redden, who is the chairman of Sotheby’s books department and has auctioned copies of Magna Carta and the Declaration of Independence, among other historic and valuable documents, will sell that copy on Nov. 26. Sotheby’s expects it to go for $15 million to $30 million, which would make it the most expensive book ever sold at auction — more expensive than a copy of John James Audubon’s “The Birds of America” that sold in December 2010 for $11.54 million (equivalent to $12.39 million in 2013 dollars), the current record. That beat the $7.5 million ($10.77 million today) paid for a copy of Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” at Christie’s in London in 1998, and the $6.16 million ($8.14 million today) paid for Shakespeare’s First Folio at Christie’s in New York in 2001.

But the Bay Psalm Book, as it is known, has a special place in bibliophiles’ hearts, so much so that Michael Inman, the curator of rare books at the New York Public Library, said the auction was “likely” to set a record, even though the Bay Psalm Book was “not a particularly attractive book” and was “rather shoddily done.” (The library owns one of the other 10 copies.)

“It’s what that book symbolizes,” Mr. Inman said. “These 11 copies symbolize the introduction of printing into the British colonies, which was reflective of the importance placed on reading and education by the Puritans and the concept of freely available information, freedom of expression, freedom of the press. All that fed into the revolutionary impulse that gave rise to the United States.”

In its way, experts say, the Bay Psalm Book laid the groundwork for famous texts of the Revolution like Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense.” It followed the first Gutenberg Bibles by more than a century and a half, and it was plagued by spelling problems. The word “psalm,” which is supposed to appear in capital letters at the top of each page, is spelled that way on the left-hand pages, but on the right-hand pages and on the title page, there is an “e” on the end: “The WHOLE Booke of Psalmes Faithfully TRANSLATED into ENGLISH Metre.” The volume also has a subtitle, as important to a religious book in the 17th century as to a 21st-century best-seller: “Whereunto is prefixed a di∫cour∫e declaring not only the lawfullne∫∫, but al∫o the nece∫∫ity of the heavenly Ordinance of ∫inging ∫cripture P∫alme∫ in the Churche∫ of God.”

The other copies are all held in libraries or museums. The Library of Congress has one. So does Harvard. So does Yale. And one copy made its way to the place the Puritans had fled — to England, and the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

The copy being sold by Sotheby’s, which the auction house will display in New York on Monday, belongs to Old South Church in Boston, whose long history includes the baptism of Benjamin Franklin when he was a day old. Old South became known as a meeting place for angry colonists before the Boston Tea Party and, more recently, as the church at the finish line of the Boston Marathon.

The Bay Psalm Book was printed on a press that had been sent over with 240 pounds of paper and one case of type. Like Mr. Inman, Mr. Redden said the workmanship was amateurish — it was, after all, the first book published in the colonies and only the third item to come off the press. “They were kind of learning on the job,” Mr. Redden said, and some of the pages were bound in the wrong order. At the bottom of one, someone wrote, “Turn back a leaf.” A version of this article appears in print on November 16, 2013, on page A14 of the New York edition of the New York Times with the headline: For First Book Printed in English in New World, Let the Bidding Begin.

Published on November 16, 2013 11:53

November 5, 2013

Blog-hopping on behalf of the Dyers

Surrounding the releases of my novels (print and e-book) and nonfiction e-book on William and Mary Dyer, I've been writing guest articles for other authors' blogs.

Here are the links, which I'll edit and refresh as needed.

Jo Ann Butler's Rebel Puritan website has an interview about the motivation and research for the novels and the nonfiction book, The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport. Find out what distinguishes this telling of the Dyer tale, from books and articles that have gone before. Click this link:

http://rebelpuritan.blogspot.com/2013/11/mary-dyer-illuminated.html

Christy English's blog, "A Writer's Life," carried my passionate plea for historical fiction readers to STOP in the seventeenth century, as they rush from medieval to Tudor to Regency novels. I gave lots of humorous and quirky factoids about the world the Dyers lived in. Click this link:

http://www.christyenglish.com/2013/10/21/sound-of-screeching-brakes-by-christy-k-robinson/

Christy English also posted her 5/5-star review of Mary Dyer Illuminated. Click this link:

http://www.christyenglish.com/2013/10/23/five-stars-for-mary-dyer-illuminated-by-christy-k-robinson/

Here are the links, which I'll edit and refresh as needed.

Jo Ann Butler's Rebel Puritan website has an interview about the motivation and research for the novels and the nonfiction book, The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport. Find out what distinguishes this telling of the Dyer tale, from books and articles that have gone before. Click this link:

http://rebelpuritan.blogspot.com/2013/11/mary-dyer-illuminated.html

Christy English's blog, "A Writer's Life," carried my passionate plea for historical fiction readers to STOP in the seventeenth century, as they rush from medieval to Tudor to Regency novels. I gave lots of humorous and quirky factoids about the world the Dyers lived in. Click this link:

http://www.christyenglish.com/2013/10/21/sound-of-screeching-brakes-by-christy-k-robinson/

Christy English also posted her 5/5-star review of Mary Dyer Illuminated. Click this link:

http://www.christyenglish.com/2013/10/23/five-stars-for-mary-dyer-illuminated-by-christy-k-robinson/

Published on November 05, 2013 21:46

October 26, 2013

London as the Dyers saw it (video)

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

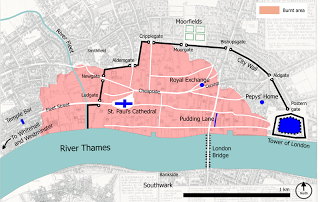

Using maps and drawings from the British Library, a team of DeMontfort University students created a three-dimensional animation of what London was like during William and Mary Dyer’s lifetime, in the mid-1600s. (Except that the designers didn't put in enough filth, dead animals, and rubbish to make it more realistic.) The model focuses on the area around Pudding Mill Lane and the bakery of Thomas Farriner, where the Great Fire of 1666 started. This was in the old walled city.

The footprint of London's Great Fire of 1666.

The footprint of London's Great Fire of 1666. The video shows the area around Pudding Lane,

near London Bridge.

They show streets, alleys, markets, a blacksmith forge, carcasses hanging from eaves at a butcher shop, the riverside warehouses, pub signs, and rooftops. A pall of coal smoke hangs over the city. The buildings are crowded so close that the sun never reaches the cobblestones in some places.

There were outbreaks of plague every few years, including 1615, 1625, 1630, 1635… The epidemics seemed to hit harder at five-year intervals, but they never really went away. A mortality table from 1632 shows that there were eight deaths from plague, but the worst were in 1635, the year the Dyers sailed to America, and of course in 1665, the year before the Great Fire. In 1635, about 30,000 Londoners died of plague, but in 1665, about 100,000 died. After the Great Fire, the huge epidemics did not recur.

Mary Barrett may have been born in the London area in 1610-11, and she was certainly a resident before she married in 1633. William Dyer, though born in Kirkby LaThorpe, Lincolnshire, apprenticed in London for nine years in the 1620s and 30s. He and Mary were living in the borough of Westminster and were members of the St. Martin-in-the-Fields parish before they emigrated to Massachusetts.

Both William and Mary visited London again in the 1650s: William twice, on Rhode Island charter business, and obtaining his commission as commander in chief upon the seas in the First Anglo Dutch War; and Mary for almost five years until about January 1657.

Of course, Mary had been executed in Boston in 1660, and William was living in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1666. The flames of the Great Fire didn’t quite reach Westminster, where they had lived, though the area was threatened because of the heavy gale and resulting fire tornados.

Their second-eldest son, William Dyer the Younger, did visit England several times on business, and lived there for a year while his treason case was decided in courts (he was acquitted). The younger William is mentioned in the diary of Samuel Pepys.

*********

Christy K Robinson is the author of two biographical novels (paperback and Kindle) on William and Mary Dyer, and a nonfiction anthology of her research into their culture: Mary Dyer Illuminated, Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This, and The Dyers of London, Boston, and Newport.

Christy K Robinson is the author of two biographical novels (paperback and Kindle) on William and Mary Dyer, and a nonfiction anthology of her research into their culture: Mary Dyer Illuminated, Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This, and The Dyers of London, Boston, and Newport.

Published on October 26, 2013 13:36

October 23, 2013

The William Dyer who wasn’t Mary Dyer’s husband

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

Over the last several years that I’ve researched William and Mary Dyer for the two novels* and nonfiction e-book* I’ve written about them, I’ve read through countless thousands of images and files, websites, books, PDFs, and sifted both scholarly papers and amateur genealogy pages. Multiply those factors by all the possible spellings of Dyer, Dyre, Diar, Dyar, Dire… and countless times countless equals some discernment and the beginning of knowledge about the Dyers and the culture they were part of.

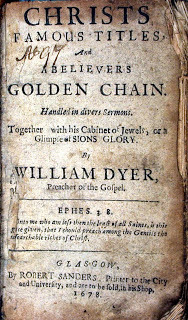

This is NOT Mary Dyer's husband.

This is NOT Mary Dyer's husband. Notice he is identified as "Preacher

of the Gospell, 1662," which was not the

occupation of William Dyer, Gent.,

of Newport, Rhode Island. When my eyes lit upon a 17th-century publication written by William Dyer, my heart beat faster—for a moment. I had discovered “a” William Dyer, but not “the” William Dyer who was married to Mary Barrett in 1633 and widowed in 1660 when she was executed for intentionally and repeatedly disobeying her banishment orders. (I take this opportunity to remind you that she was not killed “for being a Quaker.”)

This other William Dyer was born in 1632 in England (23 years after our William), and would have been twenty, perhaps still at seminary, when our Dyers visited England after the Civil War, when Oliver Cromwell was Lord Protector of the realm. Young Reverend Dyer took up the nonconformist, Puritan, Calvinist mantle when he began his gospel ministry in Chesham and then Cholesbury in Buckinghamshire in the 1650s.

In 1662, with the Act of Uniformity that restored the Church of England to the state religion, thousands of Puritan ministers were expelled from their pulpits in the Great Ejection. The Book of Common Prayer was again used in church liturgy. Reverend Dyer likely lost his employment then and perhaps turned to writing instead of preaching. His best-known work is A Cabinet of Jewels, or a Glimpse of Sion’s Glory, published in 1663.

After the 1665 bubonic plague epidemic killed 100,000 or more Londoners and continued ravaging the rest of the country, there was a massive fire that consumed the old, rickety, closely-built neighborhoods of London. Even St. Paul’s Cathedral, with its ancient monuments and tombs inside, fell to the fire.

In 1665, Rev. Dyer preached at St. Anne’s, Aldersgate Street, London, less than a thousand feet northwest of St. Paul’s. He claimed in his sermons that the plague was God’s punishment on wicked, licentious London, and the next year, he published the sermons with the title Christ’s Voice to London. (The rest of the sermon was logical and persuasive, I thought. What follows, though, is an excerpt where Rev. Dyer must have broken forth with shouting and tears.)"Oh, London, London! God speaks to you by his judgments, and because you would not hear the voice of his Word, he has made you to feel the stroke of his rod! Oh, great city! how has the plague broke in upon you, because of your abominations! "They provoked the Lord to anger by their wicked deeds—so a plague broke out among them!" Psalm 106:29. Oh, you of this city! how is the wrath of God kindled against you, that such multitudes of thousands have died within your borders, by this severe plague, God's immediate sword! London! how are your streets thinned, your widows increased, and your cemeteries filled, your inhabitants fled, your trade decayed! Oh! therefore lay to heart, you who are yet alive, all these things, and turn from your wicked ways, that the cry of your prayers may outcry the cry of your sins, and be like the city of Nineveh, who believed Jonah's message from God, who humbled themselves, and fasted, and cried mightily unto the Lord, "The Ninevites believed God. They declared a fast, and all of them, from the greatest to the least, put on sackcloth. When the news reached the king of Nineveh, he rose from his throne, took off his royal robes, covered himself with sackcloth and sat down in the dust!" Jonah 3:5-6 Oh, let not the heathen outstrip professing Christians! Did Nineveh repent and turn from their wicked ways—and shall not London?"

A Puritan website describes Rev. Dyer as “a godly pastor” of “great piety, and a serious fervent preacher.” They’ve posted the text of some his sermons.

Reverend Dyer’s book Christ’s Famous Titles and a Believer’s Golden Chain (1678) has this paragraph that rings true today. One could apply it to anything that keeps them “busy” and distracted from what is truly important. “It is the great unhappiness of our age, that the greatest part of men busy themselves most in that which concerns them least. Look into the world among rich and poor, high and low, young and old, and see whether it appear not by the whole scope of their conversations, that they set more by something else than Christ and salvation. So they may have but some of the earth in their hands, they care for nothing of heaven in their hearts, though gold can no more fill their hearts than grass their purses.”

Other books followed, and Reverend Dyer died in 1696, aged about 64. He was buried in a Quaker cemetery in Southwark (London metro area south of the River Thames), so he may have embraced Quaker beliefs at the end.

The moral of my story here is that when you turn your attention to research historical figures or ancestors, keep in mind that there are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people who have the same surname, who are probably not closely related, or not related at all. Until you’ve sorted them out and confirmed dates and locations, you should not make assumptions that this guy must be the same as that guy. *******

Christy K Robinson is the author of two biographical novels (paperback and Kindle) on William and Mary Dyer, and a nonfiction anthology of her research into their culture: Mary Dyer Illuminated, Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This, and The Dyers of London, Boston, and Newport.

Published on October 23, 2013 01:51

October 1, 2013

The 17th century: World without end

This article appeared first on Andrea Zuvich's blog, 17th Century Woman, on Sept. 26, 2013.

by Christy K Robinson

Who was Mary Dyer? Very little has been known for sure, except that Mary was a 17th-century educated Englishwoman who married at St. Martin-in-the-Fields parish in Westminster; she gave birth eight times, including to an anencephalic fetus that was called a monster; she emigrated to New England’s wilderness and cofounded America’s first democracy, and she eventually was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1660 for her intentional civil disobedience to Boston’s theocratic government.

While we don’t find much direct evidence of Mary’s life and thoughts, we can look at the culture, politics, religions, natural history, sociology, genealogical records of her associates, and journals and letters, of the friends and family—and enemies—surrounding her. All those pieces, when placed in parallel timelines and looked at with logic, create a painting of the woman only glimpsed in the journals of others or in court records of the day. Book cover painting: Jan Vermeer,

Book cover painting: Jan Vermeer,

ca 1657-59. Public domain.

Kindle book: http://amzn.to/1bHFWtW Kindle's free reading app: http://amzn.to/MtttcO

My two-part novel of the Dyers is not written for the religious or inspirational genre. It’s historical/biographical fiction based in fact. But because of the highly-charged atmosphere of the 17th century, the reader will understand that religious beliefs were paramount to every Western culture at that time. · The Separatists who became the Pilgrims fled the Anglican repression under King James I, first to the Netherlands and then to America.· The Great Migration of the 1630s from England to Massachusetts and Virginia was years in the making, but its crux was King Charles I’s re-publication of The Book of Sports which forced the Puritans to break with Anglicans, resulting in 21,000 people moving to Massachusetts and thousands more to Virginia Colony. · The English Civil Wars of the 1640s and ’50s were begun over Anglican (royal)-versus-Puritan (Parliamentary) issues. · The Thirty Years War, between Catholics and Protestants, raged across Europe carrying plague and famine with it. · The Jews of the Iberian peninsula, even if they converted to Catholicism, were still burned as heretics if they couldn’t escape Spain and Portugal. · The Dutch West Indies Company which colonized the Caribbean, Brazil, and parts of New England provided their settlers and military forts with Dutch Reformed ministers.

In every comet, eclipse, earthquake, or plague, the priests, ministers, and rabbis in Europe and America saw the hand of God and they preached it to their congregations. There was no secular or sacred demarcation: all was one fabric, and that was sacred fabric. They believed that the short years they were on earth were a preparatory time for eternity. Religious issues and morals weren’t lifestyle choices, fairy tales, or myths, but eternal matters. Strict adherence to biblical law and punishment of heretics concerned the entire community. Religious dogma was worth killing for, and religious liberty was worth dying for. From 1607, the appearance of Halley's Comet

From 1607, the appearance of Halley's Comet

(before Halley's name was associated with it).

Note the total and partial eclipses, the comet,

soldiers, and death (probably plague).

While researching my Dyer novels, I found references to · Great earthquakes (approximately 7.0-magnitude quake in New England on June 1, 1638, and another great quake with tsunami in April 1658)· The largest hurricane ever to strike New England made landfall between Plymouth and Boston in August 1635· Hurricanes which caused tsunami-like tidal surges in southern New England· Comet (May 29-30, 1630 visible over Europe in daylight at time of Charles II’s birth) · Annular and total solar eclipses (April 1652 “Bugbear” eclipse in British Isles put the rich in fast coaches out of London and stopped the laborers at their work; also annular eclipse in November 1659 in Massachusetts) · A blood-red lunar eclipse in June 1638 was reported by my book’s characters (very satisfying to this researcher!)· Clouds of pigeons that darkened the sky ate both seed and sprouts of Massachusetts corn planting· A plague of black caterpillars seemed to fall from the clear sky, and destroyed crops and orchards in Massachusetts and Connecticut· The Little Ice Age was at its coldest in the 1640s and 1650s, freezing harbors in Boston, Iceland, and London’s River Thames, and ruining crops in summer· The Leonid meteor shower of November 1636 was an every-33-year spectacular fireworks show that was considered a sign of Christ’s imminent return · Unexplained booming noises that were probably meteorites

The people of the 17th century, of every social or economic stratus, believed that these signs and wonders were directly from the hand of God and that they were precursors to further disaster. A New Testament verse says that all these terrifying things were the beginning of birth pangs, leading to the end of the world. Yes, more to come! Even the Narragansett tribe of Rhode Island believed that earthquakes would be inevitably followed by hurricanes, blizzards, epidemics, failed crops, and other disasters. Art from Germany shows comets in the sky, with war and bubonic plague victims dying below. From 1517: Comets, cities broken by war, bubonic plague

From 1517: Comets, cities broken by war, bubonic plague

victims, a two-headed monster, and blood raining

from sky.

Most of those events, because of their importance to our ancestors who experienced them, were resurrected in my novels. I didn’t even have to make them up!

What do we think today of natural events? Storm chasers follow tornados and stand outside with microphones in hurricanes. We take lawn chairs out in the middle of the night to see meteor showers or the faint glow of a comet (did you know there’s a spectacular comet predicted for November 2013?), and we don protective lenses and we photograph crescents for a solar eclipse. We moan and groan at the “snowpocalypse” or rain deluge. People of faith celebrate the Creator. Others celebrate nature. But only suicidal cultists think that we’re riding off the planet on a comet’s tail.

Whether you practice a religion or denominational affiliation, or you believe that there is a universal spirituality, or you believe there is no god, you can thank Mary Barrett Dyer for giving her life to win religious liberty for all—the right to exercise your beliefs, and (perhaps surprisingly) the right not to practice religion or to have it forced upon you. You can thank her husband, William Dyer, the first attorney general in America, for codifying that right. These liberties are still under attack today, all over the world. When organizations seek to blend religion with politics or government, repression will inevitably be the result. That has been the case in every society, for thousands of years. It’s up to you to continue the struggle to allow but not require religious expression.

Next time you see a special event in nature (I’m partial to desert lightning shows), just enjoy it. No need to flee the city, start a holy war, or form a new nation. Neither Jehovah nor Zeus is hurling disaster after you!

***** Christy K Robinson has recently published the first of three books on the Dyers and their world: Mary Dyer Illuminated (historical fiction); Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This; and The Dyers of London, Boston, and Newport (nonfiction research of 17th century culture).

by Christy K Robinson

Who was Mary Dyer? Very little has been known for sure, except that Mary was a 17th-century educated Englishwoman who married at St. Martin-in-the-Fields parish in Westminster; she gave birth eight times, including to an anencephalic fetus that was called a monster; she emigrated to New England’s wilderness and cofounded America’s first democracy, and she eventually was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1660 for her intentional civil disobedience to Boston’s theocratic government.

While we don’t find much direct evidence of Mary’s life and thoughts, we can look at the culture, politics, religions, natural history, sociology, genealogical records of her associates, and journals and letters, of the friends and family—and enemies—surrounding her. All those pieces, when placed in parallel timelines and looked at with logic, create a painting of the woman only glimpsed in the journals of others or in court records of the day.

Book cover painting: Jan Vermeer,

Book cover painting: Jan Vermeer, ca 1657-59. Public domain.

Kindle book: http://amzn.to/1bHFWtW Kindle's free reading app: http://amzn.to/MtttcO

My two-part novel of the Dyers is not written for the religious or inspirational genre. It’s historical/biographical fiction based in fact. But because of the highly-charged atmosphere of the 17th century, the reader will understand that religious beliefs were paramount to every Western culture at that time. · The Separatists who became the Pilgrims fled the Anglican repression under King James I, first to the Netherlands and then to America.· The Great Migration of the 1630s from England to Massachusetts and Virginia was years in the making, but its crux was King Charles I’s re-publication of The Book of Sports which forced the Puritans to break with Anglicans, resulting in 21,000 people moving to Massachusetts and thousands more to Virginia Colony. · The English Civil Wars of the 1640s and ’50s were begun over Anglican (royal)-versus-Puritan (Parliamentary) issues. · The Thirty Years War, between Catholics and Protestants, raged across Europe carrying plague and famine with it. · The Jews of the Iberian peninsula, even if they converted to Catholicism, were still burned as heretics if they couldn’t escape Spain and Portugal. · The Dutch West Indies Company which colonized the Caribbean, Brazil, and parts of New England provided their settlers and military forts with Dutch Reformed ministers.

In every comet, eclipse, earthquake, or plague, the priests, ministers, and rabbis in Europe and America saw the hand of God and they preached it to their congregations. There was no secular or sacred demarcation: all was one fabric, and that was sacred fabric. They believed that the short years they were on earth were a preparatory time for eternity. Religious issues and morals weren’t lifestyle choices, fairy tales, or myths, but eternal matters. Strict adherence to biblical law and punishment of heretics concerned the entire community. Religious dogma was worth killing for, and religious liberty was worth dying for.

From 1607, the appearance of Halley's Comet

From 1607, the appearance of Halley's Comet (before Halley's name was associated with it).

Note the total and partial eclipses, the comet,

soldiers, and death (probably plague).

While researching my Dyer novels, I found references to · Great earthquakes (approximately 7.0-magnitude quake in New England on June 1, 1638, and another great quake with tsunami in April 1658)· The largest hurricane ever to strike New England made landfall between Plymouth and Boston in August 1635· Hurricanes which caused tsunami-like tidal surges in southern New England· Comet (May 29-30, 1630 visible over Europe in daylight at time of Charles II’s birth) · Annular and total solar eclipses (April 1652 “Bugbear” eclipse in British Isles put the rich in fast coaches out of London and stopped the laborers at their work; also annular eclipse in November 1659 in Massachusetts) · A blood-red lunar eclipse in June 1638 was reported by my book’s characters (very satisfying to this researcher!)· Clouds of pigeons that darkened the sky ate both seed and sprouts of Massachusetts corn planting· A plague of black caterpillars seemed to fall from the clear sky, and destroyed crops and orchards in Massachusetts and Connecticut· The Little Ice Age was at its coldest in the 1640s and 1650s, freezing harbors in Boston, Iceland, and London’s River Thames, and ruining crops in summer· The Leonid meteor shower of November 1636 was an every-33-year spectacular fireworks show that was considered a sign of Christ’s imminent return · Unexplained booming noises that were probably meteorites

The people of the 17th century, of every social or economic stratus, believed that these signs and wonders were directly from the hand of God and that they were precursors to further disaster. A New Testament verse says that all these terrifying things were the beginning of birth pangs, leading to the end of the world. Yes, more to come! Even the Narragansett tribe of Rhode Island believed that earthquakes would be inevitably followed by hurricanes, blizzards, epidemics, failed crops, and other disasters. Art from Germany shows comets in the sky, with war and bubonic plague victims dying below.

From 1517: Comets, cities broken by war, bubonic plague

From 1517: Comets, cities broken by war, bubonic plague victims, a two-headed monster, and blood raining

from sky.

Most of those events, because of their importance to our ancestors who experienced them, were resurrected in my novels. I didn’t even have to make them up!

What do we think today of natural events? Storm chasers follow tornados and stand outside with microphones in hurricanes. We take lawn chairs out in the middle of the night to see meteor showers or the faint glow of a comet (did you know there’s a spectacular comet predicted for November 2013?), and we don protective lenses and we photograph crescents for a solar eclipse. We moan and groan at the “snowpocalypse” or rain deluge. People of faith celebrate the Creator. Others celebrate nature. But only suicidal cultists think that we’re riding off the planet on a comet’s tail.

Whether you practice a religion or denominational affiliation, or you believe that there is a universal spirituality, or you believe there is no god, you can thank Mary Barrett Dyer for giving her life to win religious liberty for all—the right to exercise your beliefs, and (perhaps surprisingly) the right not to practice religion or to have it forced upon you. You can thank her husband, William Dyer, the first attorney general in America, for codifying that right. These liberties are still under attack today, all over the world. When organizations seek to blend religion with politics or government, repression will inevitably be the result. That has been the case in every society, for thousands of years. It’s up to you to continue the struggle to allow but not require religious expression.

Next time you see a special event in nature (I’m partial to desert lightning shows), just enjoy it. No need to flee the city, start a holy war, or form a new nation. Neither Jehovah nor Zeus is hurling disaster after you!

***** Christy K Robinson has recently published the first of three books on the Dyers and their world: Mary Dyer Illuminated (historical fiction); Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This; and The Dyers of London, Boston, and Newport (nonfiction research of 17th century culture).

Published on October 01, 2013 00:00

September 12, 2013

The Dyers of London, and where they lived

William Dyer, as an apprentice, lived with his "master," Walter Blackborne, during his term of study, work, and learning the secrets of his master's trade as a milliner. Blackborne had a men's leather goods shop in the posh New Exchange shops on The Strand. When William himself became a master, he took over the lease on the shop and Blackborne's house on Greene's Lane (or Greene's Alley). That's where he brought his bride, Mary Barrett, to live from their marriage in October 1633 until they emigrated to Boston in 1635.

The home, probably a tall tenement building, was nestled among the palatial residences of the dukes and aristocracy of York, Northumberland, Durham, Suffolk, Bedford, Savoy, Whitehall Palace, and other wealthy members of the government, including Henry Vane (the Elder and Younger).

Clicking on the images below should enlarge them for more detail.

The image is from an engraving by Claes Visscher, a Dutch artist who may never have visited London, but created his panorama from maps and drawings. The engraving was published in 1616, during William Dyer's childhood. I've cropped out the center and east panels of the long panorama, to focus on the Dyer surroundings. Image: public domain.

The image is from an engraving by Claes Visscher, a Dutch artist who may never have visited London, but created his panorama from maps and drawings. The engraving was published in 1616, during William Dyer's childhood. I've cropped out the center and east panels of the long panorama, to focus on the Dyer surroundings. Image: public domain.

In this image, the Greene's Alley location of the Blackborne/Dyer home is covered by the west end of the Embankment riverside park and the Embankment "Tube" station.

In this image, the Greene's Alley location of the Blackborne/Dyer home is covered by the west end of the Embankment riverside park and the Embankment "Tube" station.

Image: Google Maps 2010.

This image is of the pedestrian and rail bridge at the Embankment, which I took from the London Eye observation wheel. The green trees beyond the bridge are the Embankment park where the Blackborne/Dyer house was in the 17th century.

This image is of the pedestrian and rail bridge at the Embankment, which I took from the London Eye observation wheel. The green trees beyond the bridge are the Embankment park where the Blackborne/Dyer house was in the 17th century.

Image: Christy K Robinson 2006.

The Embankment on the Thames, from the railway/pedestrian bridge. This is quite close to the spot where Greene's Alley would have been. London's city financial district is in the center background. Image: Christy K Robinson 2006.

The Embankment on the Thames, from the railway/pedestrian bridge. This is quite close to the spot where Greene's Alley would have been. London's city financial district is in the center background. Image: Christy K Robinson 2006.

The home, probably a tall tenement building, was nestled among the palatial residences of the dukes and aristocracy of York, Northumberland, Durham, Suffolk, Bedford, Savoy, Whitehall Palace, and other wealthy members of the government, including Henry Vane (the Elder and Younger).

Clicking on the images below should enlarge them for more detail.

The image is from an engraving by Claes Visscher, a Dutch artist who may never have visited London, but created his panorama from maps and drawings. The engraving was published in 1616, during William Dyer's childhood. I've cropped out the center and east panels of the long panorama, to focus on the Dyer surroundings. Image: public domain.

The image is from an engraving by Claes Visscher, a Dutch artist who may never have visited London, but created his panorama from maps and drawings. The engraving was published in 1616, during William Dyer's childhood. I've cropped out the center and east panels of the long panorama, to focus on the Dyer surroundings. Image: public domain.

In this image, the Greene's Alley location of the Blackborne/Dyer home is covered by the west end of the Embankment riverside park and the Embankment "Tube" station.

In this image, the Greene's Alley location of the Blackborne/Dyer home is covered by the west end of the Embankment riverside park and the Embankment "Tube" station. Image: Google Maps 2010.

This image is of the pedestrian and rail bridge at the Embankment, which I took from the London Eye observation wheel. The green trees beyond the bridge are the Embankment park where the Blackborne/Dyer house was in the 17th century.

This image is of the pedestrian and rail bridge at the Embankment, which I took from the London Eye observation wheel. The green trees beyond the bridge are the Embankment park where the Blackborne/Dyer house was in the 17th century. Image: Christy K Robinson 2006.

The Embankment on the Thames, from the railway/pedestrian bridge. This is quite close to the spot where Greene's Alley would have been. London's city financial district is in the center background. Image: Christy K Robinson 2006.

The Embankment on the Thames, from the railway/pedestrian bridge. This is quite close to the spot where Greene's Alley would have been. London's city financial district is in the center background. Image: Christy K Robinson 2006.

Published on September 12, 2013 16:16

August 21, 2013

Anne Hutchinson's monstrous birth

or

“Strange Newes from the Isle of Rogues”

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

Anne Hutchinson statue

Anne Hutchinson statuein Boston In books, transatlantic letters, and journals, Mary Dyer’s 1637 “monstrous birth” story was kept alive for decades, not just because it was an unusual deformation and the people of Boston had nothing else horribly fascinating to gossip about. The premature stillbirth of an anencephalic fetus with spina bifida was the first recorded in the American colonies. See Mary Dyer’s “monster.”

But the monsters of Mary Dyer and her mentor and friend, Anne Hutchinson, were spoken of as a pair. Mary’s travail took place in October 1637 in Boston, and Anne’s probably in June 1638 in Portsmouth, Rhode Island.

Deformed babies, dead or alive, were called monsters for several centuries, and seen as evidence of the mother’s heresy, sexual immorality, or that she had left her proper place in subjection to her husband and ministers, and the monstrous birth was punishment from God.

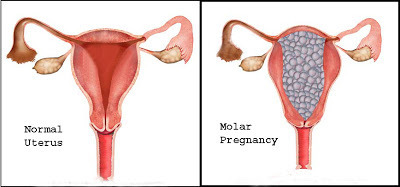

Liquid mercury Mercury, a.k.a. quicksilver, was often used as a medication for various ills, and drinking vessels and lead or pewter dishware poisoned those who used them regularly—particularly pregnant women. Mercury or lead poisoning might have been the cause of Mary’s fetus suffering an in utero stroke in her first weeks of pregnancy. Anne’s monster, which is now known to be hydatidiform moles, or a molar pregnancy, was probably due to her age, 47, as women over 40 years of age are five to ten times more likely to develop the condition.

Liquid mercury Mercury, a.k.a. quicksilver, was often used as a medication for various ills, and drinking vessels and lead or pewter dishware poisoned those who used them regularly—particularly pregnant women. Mercury or lead poisoning might have been the cause of Mary’s fetus suffering an in utero stroke in her first weeks of pregnancy. Anne’s monster, which is now known to be hydatidiform moles, or a molar pregnancy, was probably due to her age, 47, as women over 40 years of age are five to ten times more likely to develop the condition. Anne had been imprisoned at the home of Joseph Welde of Roxbury, Mass., between November 2, 1637, and her heresy trial in March 1638, when she was released to prepare to move out of Massachusetts Bay Colony by the end of April. She could not have been pregnant during her house arrest, or she would have borne the “monster” during that period; nor was she allowed conjugal visits during the time in Welde’s house. So she conceived in late March, probably, when she and William reunited. She had borne 15 babies that survived infancy by then, the youngest being two years old.

Anne, her family, and scores of other families, including the Dyers, made their exodus from Boston on foot, and walked 44 miles through fresh, deep snow to the tiny town of Providence. Shortly after that, they set up a camp in Pocasset/Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and began to build their town.

On June 1, 1638, when they’d only been there a few weeks, they experienced the largest earthquake New England has produced in recorded memory. By its description, seismologists today think it might have registered 6.5 to 7.0 on the Richter scale.

Probably soon after the earthquake, while they were still experiencing aftershocks, Anne, an experienced midwife, began feeling weak, and consulted the young doctor in their company because she feared for either her or her baby’s life.

Molar pregnancies can last three months or less before they spontaneously abort (as in Anne’s case) or are removed by surgical procedure. A hydatidiform mole is an abnormal growth of placental tissue, or it could be from a non-viable fertilized egg. It develops as a cluster of water-filled sacs, and it’s not a baby. Complications can include anemia, toxemia of pregnancy, heart failure, hemorrhage, and sepsis. If the moles invade the uterine wall, they can lead to deadly thromboses and even cancer. It seems from the description of Anne’s case, that she was very lucky or very blessed not to have suffered the latter.

Molar pregnancies can last three months or less before they spontaneously abort (as in Anne’s case) or are removed by surgical procedure. A hydatidiform mole is an abnormal growth of placental tissue, or it could be from a non-viable fertilized egg. It develops as a cluster of water-filled sacs, and it’s not a baby. Complications can include anemia, toxemia of pregnancy, heart failure, hemorrhage, and sepsis. If the moles invade the uterine wall, they can lead to deadly thromboses and even cancer. It seems from the description of Anne’s case, that she was very lucky or very blessed not to have suffered the latter.The women most likely to have delivered Anne’s moles would be midwife Jane Hawkins, Mary Dyer, and Anne’s sister Katherine Marbury Scott. Doctors did not deliver babies at that time.

**********

Even Dr. Clarke had never heard of such a delivery as Anne Hutchinson’s. Once he’d examined her and was sure that her womb was clear and she’d recover, he went home to study and record the pathology. Reverend Doctor John Clarke was the same age as William Dyer: twenty-nine. He’d emigrated to Boston in 1637, immediately joined the Hutchinson side in the Antinomian controversy, and traveled to Portsmouth with them when all were banished. He’d received his doctorate in theology at Oxford, but his subsequent training in the Netherlands had included medicine.

William Hutchinson wrote a letter to his friend and pastor of more than twenty years, Reverend John Cotton, telling him the news of their new settlement, that he’d been elected governor of Portsmouth, and that Anne’s pregnancy had ended in grief.

In his next sermon at Boston First Church, Rev. Cotton preached about the monstrous birth, proclaiming that it signified Anne’s error in “denying inherent righteousness but that all Christ was in us, and nothing of our faith, love, et cetera.” Reverend Cotton protested that goodness could not be human nature because it could only be imparted to a faithful believer by the grace of Christ, and the evidence of Christ in one’s heart was one’s faithfulness to and love for the laws of Moses. Anne Hutchinson, the heretic, said that the necessity of law-keeping had been abolished at the cross. Her heresy had been confirmed by Almighty God with this monstrous birth.

Governor John Winthrop, hearing of Anne’s miscarriage, seized upon the opportunity to write to John Clarke, to ask if the story was true.

Hydatidiform molar mass with placenta, resembling

Hydatidiform molar mass with placenta, resembling the description by Dr. Clarke. Dr. Clarke wrote in reply: “Mrs. Hutchinson, six weeks before her delivery, perceived her body to be greatly distempered, and her spirits failing, and in that regard doubtful of life, she sent to me, etc., and not long after (in a heavy discharge from the womb) it was brought to light, and I was called to see it, where I beheld, first unwashed, (and afterwards in warm water,) several lumps, every one of them greatly confused, and if you consider each of them according to the representation of the whole, they were altogether without form; but if they were considered in respect of the parts of each lump of flesh, then there was a representation of innumerable distinct bodies in the form of a globe, not much unlike the swims of some fish, so confusedly knit together by so many several strings, (which I conceive were the beginning of veins and nerves,) so that it was impossible either to number the small round pieces in every lump, much less to discern from whence every string did fetch its original, they were so snarled one within another. The small globes I likewise opened, and perceived the matter of them (setting aside the membrane in which it was involved,) to be partly wind [air] and partly water. Of these several lumps there were about twenty-six, according to the relation of those, who more narrowly searched into the number of them. I took notice of six or seven of some bigness; the rest were small; but all as I have declared, except one or two, which differed much from the rest both in matter and form; and the whole [afterbirth] was like the lobe of the liver, being similar everywhere like itself. When I had opened it, the matter seemed to be blood congealed.”

This was not enough for John Winthrop, who wasn’t after the gory pathology report, but a moral reason for Anne’s miscarriage. And Clarke’s report seemed to be at variance with Cotton’s sermon. Winthrop later spoke to Dr. Clarke, who confirmed and summarized his report. Cotton corrected himself in the pulpit, saying he’d gotten his information from William Hutchinson.

Winthrop recorded his impressions. “Thus it hath pleased the Lord to have compassion of his poor churches here, and to discover this great imposter, an instrument of Satan so fitted and trained to his service for interrupting the passage of the Kingdom in this part of the world, and poisoning the Churches here planted, as no story records the like of a woman, since that mentioned in the Revelation…”

As a result of the letters, the private meetings and public sermons to discuss Anne’s obvious divine punishment, the news of the monstrous births, including Mary’s miscarriage, spread over all of New England, and tales were told across the Atlantic as well. Anne’s teachings and prophetic authority, which brought so many to Rhode Island, lost so much respect that dissension grew among her followers. William Hutchinson had been made governor of Portsmouth, but a split had formed. Some of the Pocasset founders, led by William Coddington, prepared to begin a new town, Newport, on the south side of the island, where there was a deeper harbor and better land for development.

**********

In the months after Anne’s molar pregnancy, or monster birth, her authority and ministry suffered, perhaps because she was ill and recovering; or that once the Antinomians were out of reach of the Boston magistrates and ministers, her message lost some urgency; or it could be that the people of Pocasset still held the superstitious beliefs of their parents and grandparents: that monsters were the proof of a woman’s heresy.

By the 1650s, when scandalous women were speaking in public as sectarian preachers and missionaries, there was a caution that women who preached, or even who listened to women preachers, gave birth to monsters. This was a direct reference to Hutchinson and Dyer, who were famous on both sides of the Atlantic not for what they might have taught or spoken of, but because of their wombs.

Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson were by no means the only English women to bear monsters, but they were and are the most famous of them.

Published on August 21, 2013 17:32

August 1, 2013

William Coddington: Rhode Island’s Governor for life

© 2013 Jo Ann Butler, used by permission

This painting is said to be Coddington,

This painting is said to be Coddington, but from the clothing style,

it is probably his grandson,

William Coddington.

Rhode Island once had a governor for life, but few people apart from historians remember that peculiar incident. William Coddington was elected to govern Rhode Island nearly every year between 1638 and 1648. In 1649 he was elected again, but refused to serve. Why was that, and who was William Coddington?

Born in 1601 in Boston, Lincolnshire, William Coddington was a member of the Winthrop party which founded Boston, Massachusetts in 1630. Even before the company embarked, he was chosen as Governor John Winthrop’s assistant, a position the affluent Coddington held through 1637.

In that year, Coddington was part of a group which coalesced around Anne Hutchinson in a religious and political dispute. Out of favor with Winthrop’s Puritans, they were ordered to surrender their arms, and then questioned by the court. A few of Hutchinson’s supporters were banished, and over 140 men packed up their families and left Massachusetts.

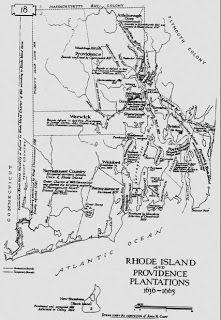

Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

Rhode Island and Providence Plantations1636-1665Most of them relocated to Aquidneck Island in Narragansett Bay, which would eventually be renamed Rhode Island. Note: at this time, Rhode Island was not the name of the entire colony, but refers to the island formerly known as Aquidneck. Providence Plantations was a separate entity comprising Providence and Warwick.

William Coddington was more gently handled by the Puritans than others of Hutchinson’s party. Governor Winthrop asked him to reconsider his error and to stay in Boston. Coddington chose to leave. Even before leaving Boston, he and eighteen other men signed a compact to bind themselves into “a Body Politicke.” Coddington was elected to lead the new community of Pocasset, now Portsmouth, Rhode Island.

As Judge, William Coddington had two votes in deciding colonial affairs, and perhaps that was typical of his leadership. Other Portsmouth residents apparently took offense, and the controversial Samuell Gorton helped stir resentment. In 1639, Coddington was voted out of office, and Anne’s husband William Hutchinson was set in his place.

Once more, Coddington and his supporters, including William and Mary Dyer, left town. They settled on the south end of the island and called their new colony Newport. Naturally, Coddington led Newport. Portsmouth and Newport soon settled their differences and Coddington led both towns until 1647. In that year, Newport and Portsmouth united with Providence and Warwick under a single government. William Coddington was elected President of the four towns for the next two years.

In 1644, Roger Williams obtained a charter from King Charles I. The charter defined Rhode Island’s boundaries and protected the colonists’ lands from seizure by the Puritan Massachusetts or Plymouth. Rhode Island’s four towns were united and Coddington ruled them, but he could foresee a day when one of his rivals might be elected to govern him.

Coddington’s next actions may be explained by deep enmity with Samuell Gorton of Warwick, and perhaps rivalry with Roger Williams of Providence. In May 1648 Coddington was again elected President, but refused to serve. Rhode Island’s records state that there “are divers bills of complaint exhibited against Mr. Coddington,” but unfortunately they do not name those charges.

Still in disfavor, Coddington sailed to England in January 1649. There he obtained a new wife, and a commission making him Rhode Island’s governor – and annulling Roger Williams’ 1644 charter. There was no provision in the commission for elections, so it appeared that Coddington was now governor for life. It seems that Coddington wasn’t entirely honest with Parliament in asking for exclusive control of Rhode Island. He told them that about thirteen years past, he had discovered two small islands, called “Aquetnet, alias Rhode Island, and Quinunagate” (Conanicut, now Jamestown), lying within Narragansett Bay, which he purchased of the Indians, and had quietly enjoyed ever since. Now, desiring to govern by English laws, he prayed for a grant of those islands from Parliament. Coddington conveniently forgot to mention that there were approximately 100 men living on Rhode Island who were allowed to vote, and perhaps a like number of non-voters, plus their families.

William Coddington returned with the document in July 1651 and set up his new government. Rhode Island was infuriated to learn that Coddington was given “full power and authority … to cause equal and indifferent justice to be duly administered to all the good people … according to the law established in this land,” to issue legal papers, “raise forces for defence … and use all lawful means to setle, improve and preserve the said Islands in peace and safety.” Coddington would choose a council of six men from Newport and Portsmouth as assistants, but those towns could not select their own representatives. Coddington now had complete power over Rhode Island. He was also allowed to choose who could settle in Rhode Island, vote, buy or be granted land, and what laws would be enacted.

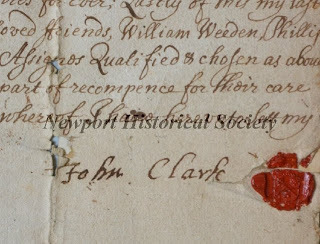

John Clarke signature By the end of 1651, most of Rhode Island’s residents had persuaded Dr. John Clarke, Roger Williams, and William Dyer to sail to England. There they would get Parliament to revoke Coddington’s commission and affirm the 1644 charter. This was done with unusual speed, and Coddington’s commission was annulled in October 1652.

John Clarke signature By the end of 1651, most of Rhode Island’s residents had persuaded Dr. John Clarke, Roger Williams, and William Dyer to sail to England. There they would get Parliament to revoke Coddington’s commission and affirm the 1644 charter. This was done with unusual speed, and Coddington’s commission was annulled in October 1652.Even before Coddington’s commission was overturned, that man had been forced to flee Rhode Island. An armed uprising against Coddington’s henchman put him in fear of “the tumultuous crew (and) their malicious thirsting after blood.” Coddington fled Newport – taking Rhode Island’s records with him into exile in Boston.

Coddington refused to lay down his commission for another four years before submitting to “the authority of his Highness in this colony as it is now united, and that with all my heart.” He returned Rhode Island’s town records and deeds. As a goodwill gesture, records critical of Coddington and his supporters (including lawsuits by William Dyer, the attorney general) were cut from the interim records and destroyed – a tragedy for historians who would love to know what happened in those years.

Coddington tombstone Though Roger Williams called Coddington more concerned with private profit and power than general welfare, eventually William Coddington was reconciled with Rhode Island’s citizens. He was even picked to govern the colony between 1674 and 1676 and in 1678, the year of his death. Was it William Coddington who mellowed with age, or was it Rhode Island which mellowed? By the 1670s the Quakers were stepping back from their dramatic civil disobedience, Rhode Island embraced them, and so did Coddington. Whatever the reason, Coddington must have been grateful for redemption at the end of his controversial life.

Coddington tombstone Though Roger Williams called Coddington more concerned with private profit and power than general welfare, eventually William Coddington was reconciled with Rhode Island’s citizens. He was even picked to govern the colony between 1674 and 1676 and in 1678, the year of his death. Was it William Coddington who mellowed with age, or was it Rhode Island which mellowed? By the 1670s the Quakers were stepping back from their dramatic civil disobedience, Rhode Island embraced them, and so did Coddington. Whatever the reason, Coddington must have been grateful for redemption at the end of his controversial life.

Jo Ann Butler is a naturalist, archaeologist, genealogist, and author of two historical novels set in Rhode Island during the lives of William and Mary Dyer: Rebel Puritan, and The Reputed Wife. Visit her websiteto learn more or to purchase the books, available in print and e-book.

Published on August 01, 2013 00:00

July 20, 2013

Who were Mary Barrett Dyer's parents?

Sorry to break it to you: Mary Dyer was not a Tudor, not the secret child of Arabella Stuart and William Seymour

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

How do you stop a very old rumor, especially if it's hit the internet? I'm going to try, by telling you, repeating it, and saying it again. I will be overly redundant on the matter. Why do I try? Because this blog has received hundreds of search inquiries on this very subject.

Many genealogy pages (and Ruth Plimpton's book) say Mary Dyer's ancestry was royal by virtue of being the secret child of Lady Arabella Stuart and Sir William Seymour. If you've copied that to your records, it's time to erase the false legend now. No researcher has found proof of Mary's parents or her birth or christening record. They have, however, found proof that Mary Barrett had a brother named William Barrett who in the custom of the times was probably named after their father. Please read researcher Johan Winsser's articles at this link.

The pure fiction that Mary was the daughter of nobility and potentially an heir to the throne of Great Britain, was created by a Dyer descendant, Frederick Nathaniel Dyer, in the 1800s, the romantic Victorian era. It resembles many other attempts by conspiracy theorists to create some sort of connection to European royalty, perhaps to explain why a girl with no known background (as yet discovered) had an above-average education and stood out among other women of her time. The romantic notion was that a commoner from Westminster could never have risen socially without a royal background. Henry VII of England,

Henry VII of England,

NOT Mary Barrett's ancestor,

therefore not your ancestor.

The false story is that Mary was the child of Lady Arabella Stuart (3x great-granddaughter of Henry VII), aged 35, and William Seymour (4x great-grandson of Henry VII), aged 22 at time of their secret and illegal marriage. King James forbade their marriage, but they married in secret in early July 1610. The secret was revealed, and by 9 July 1610, Arabella and William were arrested and imprisoned for life at the Tower of London. Separate quarters, as you must imagine! History records that there was no issue from this marriage. That means there was no secret child who would be raised as Mary Barrett. Lady Arabella Stuart, probably about the time

Lady Arabella Stuart, probably about the time

of her illegal and short-lived

marriage to William Seymour.

Age 35 was very old for first-time pregnancy in those days. It's called "elderly prima gravida" even today. If Arabella had become pregnant during her one week of married bliss and borne a baby while in the Tower or in the custody of the Bishop of Durham, it would have been noticed by servants, royal household personnel, Anglican clergy, or any of the hundreds of Tower of London employees like, oh, say, prison guards--it was impossible to hide something like that, especially since Arabella was a prisoner under a royal-watcher microscope! What about the laboring mother's screams or groans? What about a newborn baby's cry?

But according to FN Dyer's legend, the newborn Seymour child was spirited out of the Tower of London (a prison, remember, with tight security) and named after and raised by her nurse, the original Mary Dyer, and hidden from King James I while he searched for the child who had a better claim to the throne. What a crock of snooty bias!

The young William Seymour escaped the Tower and fled to France, leaving Arabella behind. Arabella also escaped, and traveled in men's clothes, but was delayed by weather, captured, and returned to prison. I've read a false rumor that Arabella Stuart Seymour was killed by King James in 1615 in the Tower of London. No, Arabella actually died-- childless --from a self-imposed hunger strike in 1615.

After Arabella died, there was no reason to keep Seymour in prison, so (no doubt after a large fine paid by his family) he went back to England, and married Lady Frances Devereux in March 1617. They had seven children. Seymour took up a political career, and was a royalist supporter of his much-removed cousins, King Charles I and II.

Let me be clear: it's impossible for Mary Dyer to have been a Stuart-Seymour daughter. I told you I'd be redundant.

Really, isn't it MORE remarkable that Mary Dyer was brilliant and accomplished on her own, without a privileged background? Now, please go to your ancestry or genealogy files and DELETE the Stuarts and Seymours from your records. Arabella Stuart Seymour had no issue. No Mary.

Celebrate that you are descended from a brilliant and beautiful woman who became great not because of whose child she was, but because of her conscious choice to lay down her life for her friends.

*********************

To join hundreds of friends and descendants of Mary and William Dyer in a discussion of their culture and experiences, join the Mary Barrett Dyer Facebook page (see the margin of this web page), and/or follow this blog (again, see margin).

http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

How do you stop a very old rumor, especially if it's hit the internet? I'm going to try, by telling you, repeating it, and saying it again. I will be overly redundant on the matter. Why do I try? Because this blog has received hundreds of search inquiries on this very subject.

Many genealogy pages (and Ruth Plimpton's book) say Mary Dyer's ancestry was royal by virtue of being the secret child of Lady Arabella Stuart and Sir William Seymour. If you've copied that to your records, it's time to erase the false legend now. No researcher has found proof of Mary's parents or her birth or christening record. They have, however, found proof that Mary Barrett had a brother named William Barrett who in the custom of the times was probably named after their father. Please read researcher Johan Winsser's articles at this link.

The pure fiction that Mary was the daughter of nobility and potentially an heir to the throne of Great Britain, was created by a Dyer descendant, Frederick Nathaniel Dyer, in the 1800s, the romantic Victorian era. It resembles many other attempts by conspiracy theorists to create some sort of connection to European royalty, perhaps to explain why a girl with no known background (as yet discovered) had an above-average education and stood out among other women of her time. The romantic notion was that a commoner from Westminster could never have risen socially without a royal background.

Henry VII of England,

Henry VII of England, NOT Mary Barrett's ancestor,

therefore not your ancestor.

The false story is that Mary was the child of Lady Arabella Stuart (3x great-granddaughter of Henry VII), aged 35, and William Seymour (4x great-grandson of Henry VII), aged 22 at time of their secret and illegal marriage. King James forbade their marriage, but they married in secret in early July 1610. The secret was revealed, and by 9 July 1610, Arabella and William were arrested and imprisoned for life at the Tower of London. Separate quarters, as you must imagine! History records that there was no issue from this marriage. That means there was no secret child who would be raised as Mary Barrett.

Lady Arabella Stuart, probably about the time

Lady Arabella Stuart, probably about the timeof her illegal and short-lived

marriage to William Seymour.

Age 35 was very old for first-time pregnancy in those days. It's called "elderly prima gravida" even today. If Arabella had become pregnant during her one week of married bliss and borne a baby while in the Tower or in the custody of the Bishop of Durham, it would have been noticed by servants, royal household personnel, Anglican clergy, or any of the hundreds of Tower of London employees like, oh, say, prison guards--it was impossible to hide something like that, especially since Arabella was a prisoner under a royal-watcher microscope! What about the laboring mother's screams or groans? What about a newborn baby's cry?

But according to FN Dyer's legend, the newborn Seymour child was spirited out of the Tower of London (a prison, remember, with tight security) and named after and raised by her nurse, the original Mary Dyer, and hidden from King James I while he searched for the child who had a better claim to the throne. What a crock of snooty bias!

The young William Seymour escaped the Tower and fled to France, leaving Arabella behind. Arabella also escaped, and traveled in men's clothes, but was delayed by weather, captured, and returned to prison. I've read a false rumor that Arabella Stuart Seymour was killed by King James in 1615 in the Tower of London. No, Arabella actually died-- childless --from a self-imposed hunger strike in 1615.

After Arabella died, there was no reason to keep Seymour in prison, so (no doubt after a large fine paid by his family) he went back to England, and married Lady Frances Devereux in March 1617. They had seven children. Seymour took up a political career, and was a royalist supporter of his much-removed cousins, King Charles I and II.

Let me be clear: it's impossible for Mary Dyer to have been a Stuart-Seymour daughter. I told you I'd be redundant.

Really, isn't it MORE remarkable that Mary Dyer was brilliant and accomplished on her own, without a privileged background? Now, please go to your ancestry or genealogy files and DELETE the Stuarts and Seymours from your records. Arabella Stuart Seymour had no issue. No Mary.

Celebrate that you are descended from a brilliant and beautiful woman who became great not because of whose child she was, but because of her conscious choice to lay down her life for her friends.

*********************

To join hundreds of friends and descendants of Mary and William Dyer in a discussion of their culture and experiences, join the Mary Barrett Dyer Facebook page (see the margin of this web page), and/or follow this blog (again, see margin).

http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com

Published on July 20, 2013 00:00

July 12, 2013

Slavery and child-trafficking in New England

© 2013 Christy K Robinson

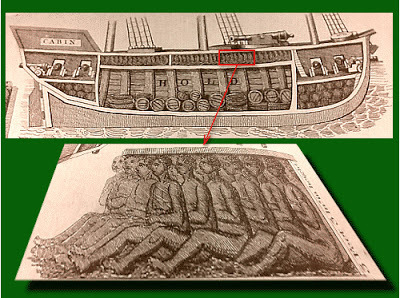

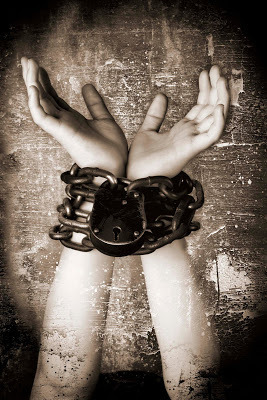

Most of us got the G-rated version of history

Most of us got the G-rated version of history in elementary school classes--

also high school--

also university. If you’re like me, you learned that American slavery was limited to the importation of African captives to the Southern colonies and states. Indentured servants were young men and women from the British Isles who desired a better life in America and contracted their services for seven years in exchange for their ocean liner ticket. Native Americans had it hard, but mostly out in the West, and they were pushed out or died out in various wars, and cheated out of their treaties and reservations. Children had some heavy-duty farm chores, and their educations were limited to eight years or so.

So yes, it was a hard life, carving a utopian republic out of the wilderness, and it took a lot of people to do it. But all my ancestors and their friends were New Englanders in the Great Migration, and they didn’t do human exploitation and trafficking.

Oh, really??

That’s not what I found while researching my biographical novel on Mary Barrett Dyer. I found pieces of the story in Governor John Winthrop’s Journal, and in snippets of social histories, genealogical websites, New England court records, and other sources.

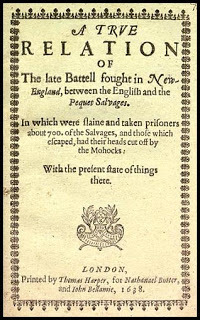

Pequot War, 1636-37

You’ll have to Google the Pequot War, because this article is concerned only with the aftermath: captured Indians becoming slaves. The few men who survived the slaughter of war were put to death. (The descriptions are grisly.) The women and children were used as house “servants” in Boston and dispersed around New England. Those who ran away and were found or turned in were branded, or sold for slavery in the Caribbean sugar and tobacco fields, which meant certain death.

You’ll have to Google the Pequot War, because this article is concerned only with the aftermath: captured Indians becoming slaves. The few men who survived the slaughter of war were put to death. (The descriptions are grisly.) The women and children were used as house “servants” in Boston and dispersed around New England. Those who ran away and were found or turned in were branded, or sold for slavery in the Caribbean sugar and tobacco fields, which meant certain death. People readily accepted these practices, but I believe it stemmed from a terrible disdain for the poor, as they were obviously not candidates for the Elect of God. Winthrop moralized the stories in his journal to contrast the blessed and cursed of God. This treatment of natives is tragic and ironic, considering that the Massachusetts seal features a native who is asking the English to come over and help him by converting him to Christianity.

Winthrop Journal, 1637 (p. 225): “Captain Stoughton and his company, having pursued the Pequots beyond Connecticut [River], and missing of them, returned to Pequot River, where they were advertised, that one hundred of them were newly come back to a place some twelve miles off. So they marched thither by night, and surprised them all. They put to death twenty-two men, and reserved two sachems [tribal chiefs], hoping by them to get Sasacus (which they promised). All the rest [72 Pequots] were women and children, of whom they gave the Narragansetts thirty, and our Massachusetts Indians three, and the rest they sent hither.”

“July 6: There were sent to Boston forty-eight women and children. There were eighty taken, as before is expressed. These were disposed of to particular persons in the country [including Winthrop, who took at least two into his service, one of whom was a sachem’s wife]. Some of them ran away and were brought again by the Indians our neighbors, and those we branded on the shoulder.”

“July 13: [Swamp fight, Capt. Davenport vs. Pequots] …life was offered to all that had not shed English blood. So they began to come forth, now some and then some, till about two hundred women and children were come out… [After the fight] … Here our men gat some booty of kettles, trays, wampum, [their food stored in pits, which was highly desirable to the English settlers whose crops were failing and people were sickening in the famine] etc., and the women and children were divided [mothers and children torn apart], and sent some to Connecticut, and some to the Massachusetts. … We had now slain and taken, in all, about seven hundred. We sent fifteen of the boys and two women to Bermuda, by Mr. Peirce; but he, missing it, carried them to Providence Isle [an island in the Caribbean, off the Nicaraguan coast, which was granted to Puritans until 1641].” In 1638, Mr. Peirce’s ship, the Desire, returned to Boston, having traded the Pequot slaves for "Salt, cotton, tobacco and Negroes."

In 1645, Emanuel Downing, brother-in-law of Governor Winthrop, wrote to him longing for another "just war" with the Pequots, so the colonists might capture enough Indian men, women, and children to exchange in Barbados for black slaves, because the colony would never thrive "untill we gett ... a stock of slaves sufficient to doe all our business." http://www.slavenorth.com/massachusetts.htm

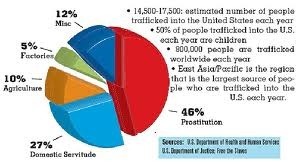

English children as “servants” Surely if you look deep enough into any country’s history, you’ll find exploitation of child labor, including sexual exploitation. It still happens all over the world today. In the seventeenth century, there are accounts of boys being “pressed” into service on merchant ships, boys kidnapped to be actors (and sexual prey) in Elizabethan theater, and Irish children whose parents had been slaughtered by Cromwell’s forces were kidnapped and sent to America (if they were lucky) or the Caribbean to die in the cane fields. In London, where thousands of children had been orphaned by the Civil Wars, famine, and plague, starving children were lured to camps or transport ships with promises of food.

No one will ever know the extent to which the children and teens of both genders were exploited for sexual slavery. In Virginia Colony, there were at least four times as many men as women, and in New England, it was about double. Virginia Colony actually sought Tobacco Brides for planters in the 1620s.

See my article on the rape and subsequent abuse of an indentured servant, Elizabeth Due, in the household of Gov. John Endecott of Salem, Massachusetts. Rather than punish the rapist who made her pregnant, one of Elizabeth’s fellow servants was accused of fornicating with her, and he was whipped 13 stripes in public and forced to marry Elizabeth.

John Winthrop’s journal, June 1643: "One of our [Massachusetts-built] ships, the Seabridge, arrived with 20 children and some other passengers out of England, and 300 pounds worth of goods purchased with the country's stock, given by some friends in England the year before; and those children, with many more to come after, were sent by money given one fast day in London, and allowed by the parliament and city for that purpose."

Translation: London Puritans took up a voluntary financial collection in the churches, to pay the passage of poor or orphan children from London to Boston, where the children were sold as indentured servants for a minimum of seven years, or to age 18 if they were younger than ten years old.

Orphans and poor were the responsibilities of parishes and their poor funds, and how convenient and easy on the consciences it was to get rid of those expensive little anklebiters and make some money at it. They cut their expenses of maintaining the poor and helpless, and they profited by selling off the liabilities. Once that lot was gone, the poor-tax collections eased.

Make no mistake, money was the issue, not the welfare of poor children.