Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 14

June 24, 2014

Winthrop Fleet fights its way to New England in 1630

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

Beach roses or salt-spray roses, growing on the shores of Maine

Beach roses or salt-spray roses, growing on the shores of Maine

in June 2014, 384 years after the Winthrop Fleet passed this spot.

Flower photos courtesy of Dr. Rondi Aastrup. In late March 1630, in their new year and on Easter Monday, the Winthrop Fleet of business investors and religious refugees heard a sermon and blessing by their favorite minister, John Cotton, and left the harbor on England’s south coast. The strong winds and rain kept the fleet glued to the coast, though, for a few weeks, and many of the passengers, including Thomas Dudley’s family and John Winthrop’s son Henry, spent time ashore rather than on the cramped ships.

Only three days into their venture, while the fleet’s occupants were fasting and praying, some farm laborers they’d brought “pierced a rundlet of strong water” (a 15-gallon barrel of whisky used primarily for medicinal purposes), and were put in "a bolt" (probably tied or chained to part of the ship) for a night and day to punish them.

The ships set their sails for Salem, Massachusetts, where a previous party, led by John Endecott, had gone a year earlier to found a town and plant crops to support itself and the hundreds of people set to arrive in 1630.

The 350-ton Arbella, admiralty ship of the Winthrop Fleet,

The 350-ton Arbella, admiralty ship of the Winthrop Fleet,

was often separated from the other ships by high seas and

a succession of raging tempests. The fleet was at sea for 10 weeks, two weeks longer than expected, and they were two months later than their original plan called for. Storms blew the fleet apart for days at a time. They’d fought the westerly gales and sailed south to the 43rd parallel before they tacked back to the North Atlantic. After a month, they were only halfway across the Atlantic, north of the Azores and west of the Bay of Biscay. The ships had to strike their sails in the tempest and were reduced to drifting if they wanted to keep their masts in one piece. “The sea raged and tossed us exceedingly, yet, through God’s mercy, we were very comfortable, and few or none sick, but had opportunity to keep the Sabbath and Mr. Phillips preached twice that day.” The Effects of Intemperance,

The Effects of Intemperance,

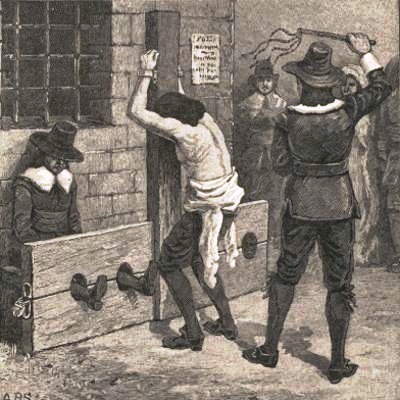

by Jan SteenTensions mounted. Men fought and spent the night in chains. A servant made a private deal with a boy (presumably the ship’s boy) to purloin three biscuits a day from the communal food supply, and upon discovery, the servant was tied to a bar and had a basket of stones placed around his neck for two hours. A maidservant, being seasick, drank so much whisky that she was “senseless, and had near killed herself. We observed it a common fault in our young people, that they gave themselves to drink hot waters [whisky] very immoderately.”

We will resist the temptation to call Mr. Winthrop “Captain Obvious” about young people and hard drinking, because in their world, their era, their religious customs, alcohol poisoning was a rare thing. As a rule, their drinks were very low in alcoholic content.

By the 29th of May, two months after their launch, three of the fleet were just off the Grand Banks, south of Sable Island and about 600 miles east of Salem. On the third of June, knowing they were nearing dangerous shoals, they sounded for depth, but found no bottom.

Cape Neddick, Maine, called Aquamentius in

Cape Neddick, Maine, called Aquamentius in

John Winthrop's Journal Finally, on June 6, they sounded at 80 fathoms/486 feet. They were offshore of Aquamentius, Maine. The next day, Monday, they were becalmed, and they threw lines and a few hooks over the sides of the ship, and in two hours caught 67 codfish, “some a yard and a half long, and a yard in compass.” Any fish of 5½ to 6 feet will weigh 100 pounds or more, says Gulf of Maine Research Institute.

Still, they couldn’t proceed too fast for fear of running on the rocks of the Isle of Shoals, a long line of rocks and small islands. They took a large boat out of storage to sail before the ships and take soundings so they could safely sail south to Salem.

"We had now fair sunshine weather,

"We had now fair sunshine weather,

and so pleasant a sweet air as did much refresh us,

and there came a smell off the shore like the smell of a garden." John Winthrop wrote in his journal on June 8, "We had now fair sunshine weather, and so pleasant a sweet air as did much refresh us, and there came a smell off the shore like the smell of a garden." They celebrated by catching another 36 cod, much needed because during the extra-long voyage, they had consumed their stores of salted fish, and were low on other provisions.

On June 9, they could see mountains on the mainland, and many islands or half-submerged rocks between the ship and the shore. On the 10th, they saw several large and small ships doing commercial fishing. On the 12th of June, they came around Cape Ann and arrived at Salem.

But conditions at Salem were harsh, with a short growing season exacerbated by the frosts and famines of the Little Ice Age. The fierce storms that had battered the Winthrop Fleet had also worn down the settlers—and killed perhaps half of them. The Endecott party used up the rations they’d brought, and were barely surviving on seafood and wild strawberries by the spring of 1630. Until the meager harvest in August, or the arrival of the Winthrop Fleet with their provisions, Salem was hungry, run down, and sick. The Winthrop Fleet, by WF Halsall (wiki)

The Winthrop Fleet, by WF Halsall (wiki)

Some of the officials of the Massachusetts Bay Company went ashore and supped on venison pasties (meat pies) and “good beer.” They met the Endecott party of settlers—who were not in good shape, and begged for the food stores on board the Winthrop ships. The town was not ready to receive the hundreds of passengers—not with food and fresh water, and not with shelter. The Winthrop party was too late to plant a food crop and build shelters for the next winter, and they had enough food only for a few more weeks.

What were they to do? You’ll find out in my book, Mary Dyer Illuminated. See the tab on this page or click this link: Books on William and Mary Dyer. The books closely follow and personalize many more luminaries than the Dyers: William and Anne Hutchinson, John Winthrop, John Cotton, Thomas Dudley, Isaak Johnson, and other brave and brilliant people.

Beach roses or salt-spray roses, growing on the shores of Maine

Beach roses or salt-spray roses, growing on the shores of Maine in June 2014, 384 years after the Winthrop Fleet passed this spot.

Flower photos courtesy of Dr. Rondi Aastrup. In late March 1630, in their new year and on Easter Monday, the Winthrop Fleet of business investors and religious refugees heard a sermon and blessing by their favorite minister, John Cotton, and left the harbor on England’s south coast. The strong winds and rain kept the fleet glued to the coast, though, for a few weeks, and many of the passengers, including Thomas Dudley’s family and John Winthrop’s son Henry, spent time ashore rather than on the cramped ships.

Only three days into their venture, while the fleet’s occupants were fasting and praying, some farm laborers they’d brought “pierced a rundlet of strong water” (a 15-gallon barrel of whisky used primarily for medicinal purposes), and were put in "a bolt" (probably tied or chained to part of the ship) for a night and day to punish them.

The ships set their sails for Salem, Massachusetts, where a previous party, led by John Endecott, had gone a year earlier to found a town and plant crops to support itself and the hundreds of people set to arrive in 1630.

The 350-ton Arbella, admiralty ship of the Winthrop Fleet,

The 350-ton Arbella, admiralty ship of the Winthrop Fleet, was often separated from the other ships by high seas and

a succession of raging tempests. The fleet was at sea for 10 weeks, two weeks longer than expected, and they were two months later than their original plan called for. Storms blew the fleet apart for days at a time. They’d fought the westerly gales and sailed south to the 43rd parallel before they tacked back to the North Atlantic. After a month, they were only halfway across the Atlantic, north of the Azores and west of the Bay of Biscay. The ships had to strike their sails in the tempest and were reduced to drifting if they wanted to keep their masts in one piece. “The sea raged and tossed us exceedingly, yet, through God’s mercy, we were very comfortable, and few or none sick, but had opportunity to keep the Sabbath and Mr. Phillips preached twice that day.”

The Effects of Intemperance,

The Effects of Intemperance,by Jan SteenTensions mounted. Men fought and spent the night in chains. A servant made a private deal with a boy (presumably the ship’s boy) to purloin three biscuits a day from the communal food supply, and upon discovery, the servant was tied to a bar and had a basket of stones placed around his neck for two hours. A maidservant, being seasick, drank so much whisky that she was “senseless, and had near killed herself. We observed it a common fault in our young people, that they gave themselves to drink hot waters [whisky] very immoderately.”

We will resist the temptation to call Mr. Winthrop “Captain Obvious” about young people and hard drinking, because in their world, their era, their religious customs, alcohol poisoning was a rare thing. As a rule, their drinks were very low in alcoholic content.

By the 29th of May, two months after their launch, three of the fleet were just off the Grand Banks, south of Sable Island and about 600 miles east of Salem. On the third of June, knowing they were nearing dangerous shoals, they sounded for depth, but found no bottom.

Cape Neddick, Maine, called Aquamentius in

Cape Neddick, Maine, called Aquamentius in John Winthrop's Journal Finally, on June 6, they sounded at 80 fathoms/486 feet. They were offshore of Aquamentius, Maine. The next day, Monday, they were becalmed, and they threw lines and a few hooks over the sides of the ship, and in two hours caught 67 codfish, “some a yard and a half long, and a yard in compass.” Any fish of 5½ to 6 feet will weigh 100 pounds or more, says Gulf of Maine Research Institute.

Still, they couldn’t proceed too fast for fear of running on the rocks of the Isle of Shoals, a long line of rocks and small islands. They took a large boat out of storage to sail before the ships and take soundings so they could safely sail south to Salem.

"We had now fair sunshine weather,

"We had now fair sunshine weather, and so pleasant a sweet air as did much refresh us,

and there came a smell off the shore like the smell of a garden." John Winthrop wrote in his journal on June 8, "We had now fair sunshine weather, and so pleasant a sweet air as did much refresh us, and there came a smell off the shore like the smell of a garden." They celebrated by catching another 36 cod, much needed because during the extra-long voyage, they had consumed their stores of salted fish, and were low on other provisions.

On June 9, they could see mountains on the mainland, and many islands or half-submerged rocks between the ship and the shore. On the 10th, they saw several large and small ships doing commercial fishing. On the 12th of June, they came around Cape Ann and arrived at Salem.

But conditions at Salem were harsh, with a short growing season exacerbated by the frosts and famines of the Little Ice Age. The fierce storms that had battered the Winthrop Fleet had also worn down the settlers—and killed perhaps half of them. The Endecott party used up the rations they’d brought, and were barely surviving on seafood and wild strawberries by the spring of 1630. Until the meager harvest in August, or the arrival of the Winthrop Fleet with their provisions, Salem was hungry, run down, and sick.

The Winthrop Fleet, by WF Halsall (wiki)

The Winthrop Fleet, by WF Halsall (wiki)Some of the officials of the Massachusetts Bay Company went ashore and supped on venison pasties (meat pies) and “good beer.” They met the Endecott party of settlers—who were not in good shape, and begged for the food stores on board the Winthrop ships. The town was not ready to receive the hundreds of passengers—not with food and fresh water, and not with shelter. The Winthrop party was too late to plant a food crop and build shelters for the next winter, and they had enough food only for a few more weeks.

What were they to do? You’ll find out in my book, Mary Dyer Illuminated. See the tab on this page or click this link: Books on William and Mary Dyer. The books closely follow and personalize many more luminaries than the Dyers: William and Anne Hutchinson, John Winthrop, John Cotton, Thomas Dudley, Isaak Johnson, and other brave and brilliant people.

Published on June 24, 2014 02:20

June 18, 2014

Four things to learn from Quakers

Mary Dyer was a Quaker in the last five to seven years of her life, and is the most famous of the four Quakers who were executed for defying the theocratic government of Massachusetts Bay Colony.

This links to an article about Quakers (Religious Society of Friends) published on Huffington Post. Click the headline to read the article.

4 Things We Can All Learn From One Of America's Oldest Religious Communities by Alena Hall A Quaker woman preaching in

A Quaker woman preaching in

New Amsterdam (New York City)

This links to an article about Quakers (Religious Society of Friends) published on Huffington Post. Click the headline to read the article.

4 Things We Can All Learn From One Of America's Oldest Religious Communities by Alena Hall

A Quaker woman preaching in

A Quaker woman preaching in New Amsterdam (New York City)

Published on June 18, 2014 14:28

Ballad: Prescription for a girl's lost virtue

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

This ballad, intended to be humorous and performed as entertainment, was published as an English broadsheet in 1624, the year that William Dyer left the family farm in Lincolnshire and apprenticed as a milliner (imported men’s accessories) in London. He was 14 going on 15.

A young man shows a prescription to the apothecaryWilliam would have been very strictly supervised by his master, and he would have spent much of his nine years of service in studying (William must have been good at geometry and other mathematics, as he was a surveyor a few years later), as well as learning the skills and secrets of his master’s trade (imports, exports, taxes and customs, accounting, business administration, maybe a smattering of law). The master was also responsible for his apprentices’ spiritual education. They were members of St. Martin-in-the-Fields Church, which had Church of England ministers and was under the authority of St. Paul’s Cathedral. William would have had a half-day off each week, on Sundays after church services in the morning.

A young man shows a prescription to the apothecaryWilliam would have been very strictly supervised by his master, and he would have spent much of his nine years of service in studying (William must have been good at geometry and other mathematics, as he was a surveyor a few years later), as well as learning the skills and secrets of his master’s trade (imports, exports, taxes and customs, accounting, business administration, maybe a smattering of law). The master was also responsible for his apprentices’ spiritual education. They were members of St. Martin-in-the-Fields Church, which had Church of England ministers and was under the authority of St. Paul’s Cathedral. William would have had a half-day off each week, on Sundays after church services in the morning. King James, and his son Charles I after him, encouraged people to play sports on Sunday, partly as a healthy outlet for their energies, and partly as a calculated persecution of the Puritans, who disapproved of sports (like the violent rugby/football/soccer and bear-baiting), and used their Sabbath afternoons for teaching and preaching—and possibly fomenting rebellion.

But though a milliner in training, William Dyer was an apprentice in the Fishmongers guild with friends who worked at the big-city docks and markets, he was a boy off the farm, and he was a normal teenager with hormones, so chances are good that he would have been knowledgeable about the birds and bees, the prostitutes and immoral girls of London, and the taverns where drinking, gambling, and singingwent on. We don’t know any details of his behavior or morals. I’m only setting the scene that he probably heard ballads like this on several occasions, especially when he was older.

The ballad reproduced below tells of a physician or apothecary who put some thought into how to “revirginate” a girl who had erred from the moral way. He described a woman of easy virtue and the remedy for restoring her maiden status. But as you read the impossible ingredients and remedies of her week-long treatment plan, you see that revirgination is impossible, but heaping shame on her might serve to change her behavior. You'll search in vain for any mention of the man who took the young woman's virginity. It's all on the woman.

The lyricist wrote on the seventh day of this eight-day remedy for spoiled maidens, “to comfort her stomach with the syrup of shame: Although she be past all hope of good name, and unto her honesty a very great stain. Let her take it to remedy the same.”

What makes the ballad funny, though, is that the treatment and pharmacological components were really not that far from established medicine of the early 17th century! At the end of this post, you’ll find related articles in this blog that list medicinal compounds made of human milk, blood from a cat’s ear, dung, insects, and mercury. At least those items were easier to obtain than the prescription below, which calls for a Spanish friar’s fart, bee brains, and three leaps of a louse.

*****

A marvellous Medicine to cure a great paine, If a Mayden-head be lost so get it againe.

To a pleasant new tune.

Once busy in study betwixt night and day,

with choice of inventions I had in my mind,

And many odd matters my mind did assay,

but any to please me I could not well find:

then suddenly casting the nose in the wind,

I smelt out a Medicine both precious and plain,

How to help silly Maidens that had been somewhat kind

to get by good order their Maiden-head again.

First the Maid must be brought into a sleep,

for three hours together before she awake,

And seven days after this diet must keep,

with these kind of compounds the which she must take,

She must eat neither roast-meat, sod, neither bake,

but all kind of dainties she must refrain,

save only this medicine, the which if she take,then it will restore her Maiden-head again.

The first day give her the slime of an Eel,

blown through a Bag-pipe with the wind of a bladder,

with two or three turnings of a spinning wheel,

boiled in an Egg-shell, and strained through a ladder:

The tongue of an Urchin, the sting of an Adder,

boiled in a blanket in a shower of rain,

With seven notes of music to make her the gladder,

and it will restore her maiden-head again.

The second day give her the peeping of a Mouse,

with three drops of thunder that falls from the sky,

And temper it with three leaps of a Louse,

and put therein three skips of a Fly,

With a gallon of water of a Widow's eye,

that weeps for her husband when death hath him slain,

Let her take this medicine and drink by and by,

and it will restore her maiden-head again.

The third day give her the chattering of a Sparrow,

roasted in Mitten of untann'd Leather,

Give it her with the rumbling of a wheel-barrow,

and baste it with three yards of a black Swans feather,

The juice of a Whetstone thereto put together,

with the fart of a Friar brought hither from Spain

Let her lay all these in an ell of Louse leather,

and lay warm her belly to help her great pain.

The fourth day give her the song of a Swallow,

well tempered with Marrow wrung out of a log,

With three pound and better of Stock-fish tallow

hard fried in the left horn of a Butchers blue dog,

With the gaggling of a Goose, & the frisks of a Frog

the bill of a shovel, or a Humble-bee's brain:

Give her this tasting, with the grunting of a Hog,

and it will restore her mayden-head again.

The fifth day give her betwixt eight a clock and nine,

Some gruel of Grantum made for the nonce,

The brains of a birdbolt powdered very fine,

and beat in a Morter of Ginne-wrens bones,

Boiled in a nut-shell betwixt two mill-stones:

with the guts of a Gudgin before she be staine:

Let her be sure to drink all this at once,

and it will restore her maiden-head again.

Now mark well the sixth day what must be her trade,

she must have a Woodcock, a Snipe, or a Quaile,

Bak'd fine in an Oven before it be made,

and mingle it with the blood of a Snaile,

With four or five Inches of a Jack-an apes tail:

what though for a while it put her to paine,

Yet let her take it without any faile,

and it will restore her maiden-head again.

Musicians in a tavern scene by David TeniersThe seventh day give her a pound of Maid's moths,

Musicians in a tavern scene by David TeniersThe seventh day give her a pound of Maid's moths,braid in a basket of danger and blame,

With conserves of Coleworts bound in a box,

to comfort her stomach with the syrup of shame:

Although she be past all hope of good name,

and unto her honesty a very great stain.

Let her take it to remedy the same,

and it will restore her maiden-head again.

Lo these are our Medicines for Maidens each one,

which in their Virginity amiss somewhat fell,

Pray you if ever you hear them make moane,

and gladly would know the place where I dwell,

At the sign of the Whip and the Egg-shell,

near Pancake alley on Salisbury Plain,

There shall they find remedy using this well

or else never to recover their maiden-head again.

********* Related articles(17th-century health and medical remedies) within this blog: Cures for what ails ye Remedies guaranteed to cure hypochondria and malingering!

Published on June 18, 2014 00:00

June 16, 2014

The ballad of The Cruel Shrew

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

Click the highlighted text for links to more information within this blog.

Seventeenth-century broadsheets, like today’s tabloid newspapers, told lurid tales of witchesand monster babies (born of heretical women like Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer), or murders or political scandals. Sometimes broadsheets were long ballads of romance or comedy, to be sung in taverns. And sometimes, they were sermons or political articles like we’d see on a blog today.

From 1200-1250, when the upper class spoke Norman French, the Middle-English word "shrew" began to describe a bad-tempered, spiteful man or woman. A shrew is a tiny rodent of two to three inches in length, weighing half an ounce at best. The European common shrew, an insectivore, is described as having red-tipped teeth, suggesting blood, and a powerful bite, so perhaps that’s the source of calling a scold or gossip a shrew. Another similarity might be the long nose, getting into others' business!

In about 1590-92, William Shakespeare wrote The Taming of the Shrew, and described a shrewish woman in this way: "Petruchio, since we are stepp'd thus far in,

I will continue that I broach'd in jest.

I can, Petruchio, help thee to a wife

With wealth enough and young and beauteous,

Brought up as best becomes a gentlewoman:

Her only fault, and that is faults enough,

Is that she is intolerable curst

And shrewd and froward, so beyond all measure

That, were my state far worser than it is,

I would not wed her for a mine of gold."

In the southern counties of England, a shrewish woman might be forced to undergo the ducking stool, which was a life-endangering ordeal where she’d be at risk of drowning while bound to a chair—and possibly gagged. In Scotland and the north of England, a shrew was sometimes dehumanized by being bridled or branked for her disrespectful utterances. In 1655, Dorothy Waugh, a young Quaker known well to Mary Dyer, was bridled in Carlyle, northwest England. Dorothy sailed to New England in 1656, and was further persecuted and beaten for sharing her faith and defying the theocratic colonial governments.

The Cruell Shrow(shrew) was written by Arthur Halliarg, between 1607 and 1641. (Based on the clothing worn in the broadsheet drawings, I'd guess the earlier date.) This is the sort of humorous entertainment that William Dyer or any of his colleagues and family might have enjoyed in their leisure time in England.

The Cruell Shrow

Or, The Patient Man's Woe

Declaring the misery, and the great pain, By his unquiet wife he doth daily sustain.To the tune of "Cuckolds -All A-row"

Come, bachelors and married men, and listen to my song,

And I will show you plainly, then, the injury and wrong

That constantly I do sustain by the unhappy life,

The which does put me to great pain, by my unquiet wife.

She never lins' her bawling, her tongue it is so loud;

But always she'll be railing, and will not be controlled.

For she the breeches still will wear, although it breeds my strife.

If I were now a bachelor, I'd never have a wife.

Sometime I go i'the morning about my daily work,

My wife she will be snorting, and in her bed she'll lurk

Until the chimes do go at eight, then she'll begin to wake.

Her morning's draught, well-spicèd' straight, to clear her eyes she'll take.

As soon as she is out of bed her looking-glass she takes,

(So vainly is she daily led); her morning's work she makes

In putting on her brave attire, that fine and costly be,

Whilst I work hard in dirt and mire. Alack! What remedy?

Then she goes forth a-gossiping amongst her own comrades;

And then she falls a-boozing with her merry blades.

When I come home from my labor hard, then she'll begin to scold,

And calls me rogue, without regard, which makes my heart full cold.

When I come home into my house, thinking to take my rest,

Then she'll begin me to abuse (before she did but jest),

With -- "Out, you rascal! you have been abroad to meet your whore!"

Then she takes up a cudgel's end, and breaks my head full sore.

When I, for quietness' sake, desire my wife for to be still,

She will not grant what I require, but swears she'll have her will.

Then if I chance to heave my hand, straightway she'll "murder!" cry;

Then judge all men that here do stand, in what a case am I

THE SECOND PART

To the Same Tune "Husband, beware the Stocks," she says to the drunk man

"Husband, beware the Stocks," she says to the drunk man

with overturned cups and jugs

And if a friend by chance me call to drink a pot of beer,

Then she'll begin to curse and brawl, and fight, and scratch, and tear,

And swears unto my work she'll send me straight, without delay,

Or else, with the same cudgel's end, she will me soundly pay.

And if I chance to sit at meat upon some holy day,

She is so sullen, she will not eat, but vex me ever and ay;

She'll pout, and lour, and curse, and bann. This is the weary life

That I do lead, poor harmless man, with my most doggèd wife.

Then is not this a piteous cause? Let all men now it try,

And give their verdicts, by the laws, between my wife and I,

And judge the cause, who is to blame. I'll to their judgment stand,

And be contented with the same, and put thereto my hand.

If I abroad go anywhere, my business for to do,

Then will my wife anon be there, for to increase my woe.

Straightway she such a noise will make with her most wicked tongue,

That all her mates, her part to take, about me soon will throng.

Thus am I now tormented still with my most cruel wife;

All through her wicked tongue so ill, I am weary of my life.

I know not truly what to do, nor how my self to mend.

This ling'ring life doth breed my woe; I would 'twere at an end.

Oh that some harmless honest man, whom death did so befriend,

To take his wife from of his hand, his sorrows for to end,

Would change with me, to rid my care, and take my wife alive

For his dead wife unto his share; then I would hope to thrive.

But so it likely will not be, (that is the worst of all!)

For, to increase my daily woe, and for to breed my fall,

My wife is still most froward bent - such is my luckless fate! -

There is no man will be content with my unhappy state.

Thus to conclude and make an end of these my verses rude,

I pray all wives for to amend, and with peace to be endued.

Take warning, all men, by the life that I sustainèd long:

Be careful how you'll choose a wife, and so I'll end my song.

FINIS.

**************************** Like this article? Read my non-fiction book on 17th-century life and times (click this highlighted title),

Like this article? Read my non-fiction book on 17th-century life and times (click this highlighted title),

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport, by Christy K Robinson.

Nonfiction, illustrated. The research and recent discoveries behind the Mary Dyer books. The Dyers is a lively nonfiction account of background color, culture, short stories, personality sketches, food, medicine, interests, recreation, cosmic events, and all the "stuff" that made up the world of William and Mary Dyer in the 1600s. Chapters on John Winthrop, Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, John Endecott, and many others. More than 70 chapters, and all-new, exclusive content found nowhere else!

Click the highlighted text for links to more information within this blog.

Seventeenth-century broadsheets, like today’s tabloid newspapers, told lurid tales of witchesand monster babies (born of heretical women like Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer), or murders or political scandals. Sometimes broadsheets were long ballads of romance or comedy, to be sung in taverns. And sometimes, they were sermons or political articles like we’d see on a blog today.

From 1200-1250, when the upper class spoke Norman French, the Middle-English word "shrew" began to describe a bad-tempered, spiteful man or woman. A shrew is a tiny rodent of two to three inches in length, weighing half an ounce at best. The European common shrew, an insectivore, is described as having red-tipped teeth, suggesting blood, and a powerful bite, so perhaps that’s the source of calling a scold or gossip a shrew. Another similarity might be the long nose, getting into others' business!

In about 1590-92, William Shakespeare wrote The Taming of the Shrew, and described a shrewish woman in this way: "Petruchio, since we are stepp'd thus far in,

I will continue that I broach'd in jest.

I can, Petruchio, help thee to a wife

With wealth enough and young and beauteous,

Brought up as best becomes a gentlewoman:

Her only fault, and that is faults enough,

Is that she is intolerable curst

And shrewd and froward, so beyond all measure

That, were my state far worser than it is,

I would not wed her for a mine of gold."

In the southern counties of England, a shrewish woman might be forced to undergo the ducking stool, which was a life-endangering ordeal where she’d be at risk of drowning while bound to a chair—and possibly gagged. In Scotland and the north of England, a shrew was sometimes dehumanized by being bridled or branked for her disrespectful utterances. In 1655, Dorothy Waugh, a young Quaker known well to Mary Dyer, was bridled in Carlyle, northwest England. Dorothy sailed to New England in 1656, and was further persecuted and beaten for sharing her faith and defying the theocratic colonial governments.

The Cruell Shrow(shrew) was written by Arthur Halliarg, between 1607 and 1641. (Based on the clothing worn in the broadsheet drawings, I'd guess the earlier date.) This is the sort of humorous entertainment that William Dyer or any of his colleagues and family might have enjoyed in their leisure time in England.

The Cruell Shrow

Or, The Patient Man's Woe

Declaring the misery, and the great pain, By his unquiet wife he doth daily sustain.To the tune of "Cuckolds -All A-row"

Come, bachelors and married men, and listen to my song,

And I will show you plainly, then, the injury and wrong

That constantly I do sustain by the unhappy life,

The which does put me to great pain, by my unquiet wife.

She never lins' her bawling, her tongue it is so loud;

But always she'll be railing, and will not be controlled.

For she the breeches still will wear, although it breeds my strife.

If I were now a bachelor, I'd never have a wife.

Sometime I go i'the morning about my daily work,

My wife she will be snorting, and in her bed she'll lurk

Until the chimes do go at eight, then she'll begin to wake.

Her morning's draught, well-spicèd' straight, to clear her eyes she'll take.

As soon as she is out of bed her looking-glass she takes,

(So vainly is she daily led); her morning's work she makes

In putting on her brave attire, that fine and costly be,

Whilst I work hard in dirt and mire. Alack! What remedy?

Then she goes forth a-gossiping amongst her own comrades;

And then she falls a-boozing with her merry blades.

When I come home from my labor hard, then she'll begin to scold,

And calls me rogue, without regard, which makes my heart full cold.

When I come home into my house, thinking to take my rest,

Then she'll begin me to abuse (before she did but jest),

With -- "Out, you rascal! you have been abroad to meet your whore!"

Then she takes up a cudgel's end, and breaks my head full sore.

When I, for quietness' sake, desire my wife for to be still,

She will not grant what I require, but swears she'll have her will.

Then if I chance to heave my hand, straightway she'll "murder!" cry;

Then judge all men that here do stand, in what a case am I

THE SECOND PART

To the Same Tune

"Husband, beware the Stocks," she says to the drunk man

"Husband, beware the Stocks," she says to the drunk man with overturned cups and jugs

And if a friend by chance me call to drink a pot of beer,

Then she'll begin to curse and brawl, and fight, and scratch, and tear,

And swears unto my work she'll send me straight, without delay,

Or else, with the same cudgel's end, she will me soundly pay.

And if I chance to sit at meat upon some holy day,

She is so sullen, she will not eat, but vex me ever and ay;

She'll pout, and lour, and curse, and bann. This is the weary life

That I do lead, poor harmless man, with my most doggèd wife.

Then is not this a piteous cause? Let all men now it try,

And give their verdicts, by the laws, between my wife and I,

And judge the cause, who is to blame. I'll to their judgment stand,

And be contented with the same, and put thereto my hand.

If I abroad go anywhere, my business for to do,

Then will my wife anon be there, for to increase my woe.

Straightway she such a noise will make with her most wicked tongue,

That all her mates, her part to take, about me soon will throng.

Thus am I now tormented still with my most cruel wife;

All through her wicked tongue so ill, I am weary of my life.

I know not truly what to do, nor how my self to mend.

This ling'ring life doth breed my woe; I would 'twere at an end.

Oh that some harmless honest man, whom death did so befriend,

To take his wife from of his hand, his sorrows for to end,

Would change with me, to rid my care, and take my wife alive

For his dead wife unto his share; then I would hope to thrive.

But so it likely will not be, (that is the worst of all!)

For, to increase my daily woe, and for to breed my fall,

My wife is still most froward bent - such is my luckless fate! -

There is no man will be content with my unhappy state.

Thus to conclude and make an end of these my verses rude,

I pray all wives for to amend, and with peace to be endued.

Take warning, all men, by the life that I sustainèd long:

Be careful how you'll choose a wife, and so I'll end my song.

FINIS.

****************************

Like this article? Read my non-fiction book on 17th-century life and times (click this highlighted title),

Like this article? Read my non-fiction book on 17th-century life and times (click this highlighted title),The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport, by Christy K Robinson.

Nonfiction, illustrated. The research and recent discoveries behind the Mary Dyer books. The Dyers is a lively nonfiction account of background color, culture, short stories, personality sketches, food, medicine, interests, recreation, cosmic events, and all the "stuff" that made up the world of William and Mary Dyer in the 1600s. Chapters on John Winthrop, Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, John Endecott, and many others. More than 70 chapters, and all-new, exclusive content found nowhere else!

Published on June 16, 2014 22:45

June 1, 2014

The anniversary of our civil rights

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

On June 1, 1660, our constitutional right to religious liberty began with the execution of Mary Dyer in Boston. The result of her civil disobedience was a royal charter of liberties granted to Rhode Island, which was a model for the United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

There were many factors along the way, of course: Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, John Clarke, and a hundred others who founded the colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation as a secular democracy; and those who governed the infant colony at their own expense while the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies tried again and again to annex the Rhode Islanders and bring them back under the theocratic fist.

There were many factors along the way, of course: Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, John Clarke, and a hundred others who founded the colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation as a secular democracy; and those who governed the infant colony at their own expense while the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies tried again and again to annex the Rhode Islanders and bring them back under the theocratic fist. Mary Dyer was a co-founder of both Portsmouth and Newport in 1638 and 1639. Her husband William was the first attorney general in all of America, and New England’s first commissioned naval commander in the Anglo-Dutch War.

William Dyer and the Rhode Island government created laws that supported the separation of church and state functions. They were no atheists—they belonged to Christian fellowships pastored by John Clarke, Obadiah Holmes, Roger Williams, and others—but they’d felt the iron grip of theocracy both in England where they’d been born, and in the short time they’d lived in Massachusetts before moving to Rhode Island. Their friends and relatives were still living under Puritan theocratic rule in Connecticut and MassBay. They were determined to keep religion in homes and churches, and government by both ancient laws and consent of the governed. They created the first democracy in America.

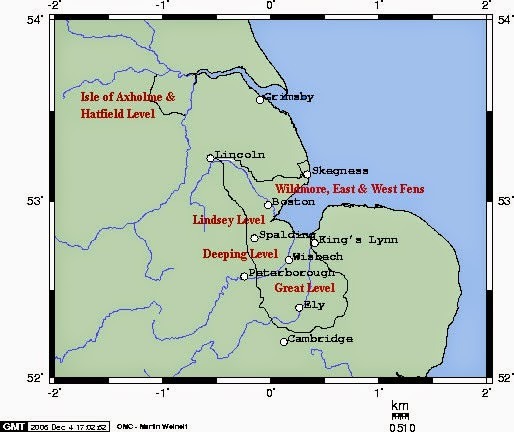

When England’s new sect of Quakers sent missionaries to New England in 1656 and 1657, they were granted refuge in Rhode Island, but the other colonies imprisoned Quakers and Baptists, sometimes without food and water, fire, or blankets in the severe winters of the Little Ice Age. Men and women were stripped naked to the waist and given severe whippings, branded with the H for heretic, had ears cut off, were choked or “bridled” with foreign objects forced into their mouths, were heavily fined, and had their lands, crops, and farm animals seized by greedy magistrates and ministers. When the teenage children of Quakers couldn’t pay fines on their elderly parents’ account, they were put on the slave block to be sold in the South, where the girl surely would have died a sex slave. (When slave ship owners refused to buy the boy and girl, they were released because Governor John Endecott was shamed before his own incensed hometown.)

When England’s new sect of Quakers sent missionaries to New England in 1656 and 1657, they were granted refuge in Rhode Island, but the other colonies imprisoned Quakers and Baptists, sometimes without food and water, fire, or blankets in the severe winters of the Little Ice Age. Men and women were stripped naked to the waist and given severe whippings, branded with the H for heretic, had ears cut off, were choked or “bridled” with foreign objects forced into their mouths, were heavily fined, and had their lands, crops, and farm animals seized by greedy magistrates and ministers. When the teenage children of Quakers couldn’t pay fines on their elderly parents’ account, they were put on the slave block to be sold in the South, where the girl surely would have died a sex slave. (When slave ship owners refused to buy the boy and girl, they were released because Governor John Endecott was shamed before his own incensed hometown.) News services, if they mention the June 1 anniversary of Mary Dyer’s execution at all, tend to repeat the old hash of Wikipedia. Several of those "facts" were reported (biased to fit their agenda) by Quakers of the time, or by a Victorian descendant of the Dyers who fantasized a royal genealogy for Mary Dyer. The text on Boston’s Mary Dyer statue did not come from her last letters, but was composed by a Quaker in London. The tale about Mary Dyer being hanged on an elm on the Boston Common was disproved decades ago. She did not die “because she was a Quaker,” as many websites repeat.

Mary Dyer deliberately broke the law (violated her banishment) on a particular date (election day and court hearing) to bring the largest audience and most attention for her protest, knowing that she would be executed—and hoping that her death as a high-status woman would be notorious enough to stop the religious executions and torture perpetrated by the religious and political government coalition. Outrage was so great that a 100-member militia of pikemen and musketeers was ordered to accompany her to the gallows—to protect the government from the crowds. Dyer went willingly, intending to die.

And when she did, the news went back to England, where her “last words” letter to the Boston authorities was rewritten by a Quaker minister, in a pamphlet submitted to King Charles II. The king wrote back to Boston and ordered the cessation of capital punishment, saying to send death-penalty cases back to England for trial. John Clarke, the Rhode Island doctor and minister, with strong input from Roger Williams and William Dyer, wrote the 1663 charter of liberties (constitution) that became a model for the United States Constitution 130 years later. The charter granted “liberty of conscience” to worship—or not—according to each person’s conscience, so long as it didn’t interfere with other laws.

So even if you don’t believe in a higher power, you owe that religious freedom and separation of powers to Mary Dyer’s death, and the brilliance of the leaders of Rhode Island. June 1, 1660 is a day to celebrate her sacrifice and our blood-bought rights. _______________

What else happened on June 1 during the Dyers' and Hutchinsons' lifetimes? It was BIG! _______________

Christy K Robinson is author of four books, including ‘Mary Dyer Illuminated’ and ‘Mary Dyer For Such a Time as This;’ and the nonfiction ‘The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport.’ All three of the Dyer books tell the story of theocratic oppression, and the birth of democracy and religious liberty in colonial America.

Published on June 01, 2014 00:00

May 11, 2014

Mary Dyer, the mother

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

Family in a Landscape, ca 1635, National Gallery, London Over the years that I’ve been researching the circumstances of Mary Dyer’s life, I’ve read articles and fielded questions in the Dyer website, wondering what kind of mother would leave her six children motherless in Rhode Island, and run off to England for five years? Why did Mary abandon her children for so long? Was she that selfish?

Family in a Landscape, ca 1635, National Gallery, London Over the years that I’ve been researching the circumstances of Mary Dyer’s life, I’ve read articles and fielded questions in the Dyer website, wondering what kind of mother would leave her six children motherless in Rhode Island, and run off to England for five years? Why did Mary abandon her children for so long? Was she that selfish?

We have no record of her thoughts about her family. No journal. No letters between wife and husband, or mother and children. But we do have some hints from her husband William Dyer, in his letters to the General Court at Boston. There are English customs that have been forgotten in the intervening centuries. There was a war going on, on both sides of the Atlantic.

Between 1633 and 1650, Mary bore eight babies that we know of, though it’s possible she miscarried during the years between the babies that lived. She spent 19 years of her young adult life, bearing and raising babies. Jan Steen, The Feast of St Nicholas Fosterage was a British custom from at least 500BC, when the Celts invaded the island. In the Celtic culture, people traded five- or six-year-old children for relatives’ or nobles’ children, in order to teach moral, religious, and societal values with less possibility of spoiling their heirs. The children were reared with the greatest love and respect, as well as discipline. This strengthened clan alliances and often, children were raised together, knowing they’d be married at puberty. When the Saxons invaded the islands, they brought similar customs of fosterage, and it was well-known among the Normans, who would send their boys to the guilds, knights, or the Church to be trained as squires, cavalry, infantry, farmers, clerks, or monks or priests. The girls learned the necessary skills of administering estates, nursing, midwifery, seamstressing, and many other roles. Later, as professional guilds evolved, boys of 12 or 14 were apprenticed from seven to nine years to a trade or profession, and girls were given to convents or to other families to be trained. Finally, from the English Reformation and well through the 18thcentury, when infant and child mortality were very high, parents were told not to love children too dearly so they wouldn’t be so broken when a child died of illness or injury, and they farmed children out to learn skills without the interference of doting, spoiling parents.

Jan Steen, The Feast of St Nicholas Fosterage was a British custom from at least 500BC, when the Celts invaded the island. In the Celtic culture, people traded five- or six-year-old children for relatives’ or nobles’ children, in order to teach moral, religious, and societal values with less possibility of spoiling their heirs. The children were reared with the greatest love and respect, as well as discipline. This strengthened clan alliances and often, children were raised together, knowing they’d be married at puberty. When the Saxons invaded the islands, they brought similar customs of fosterage, and it was well-known among the Normans, who would send their boys to the guilds, knights, or the Church to be trained as squires, cavalry, infantry, farmers, clerks, or monks or priests. The girls learned the necessary skills of administering estates, nursing, midwifery, seamstressing, and many other roles. Later, as professional guilds evolved, boys of 12 or 14 were apprenticed from seven to nine years to a trade or profession, and girls were given to convents or to other families to be trained. Finally, from the English Reformation and well through the 18thcentury, when infant and child mortality were very high, parents were told not to love children too dearly so they wouldn’t be so broken when a child died of illness or injury, and they farmed children out to learn skills without the interference of doting, spoiling parents.

William Dyer served nine years as an apprentice in London, 125 miles from his parents’ home. We don’t know Mary’s background, but she was well-educated, and was a skilled writer when most women could read a little but not write, and not even every man could write. It’s possible that Mary had a private tutor, or she was encouraged by a foster parent.

So you see, putting your children in fosterage was not abandoning them. It was done with the best of intentions, and indeed love, to ensure their future as useful members of society.

When Mary left for England in early 1652, she almost surely did not expect to stay there for five years! War and God's call changed her trajectory.

Samuel (the Dyer’s eldest and the heir) would have been 16 and well into his training. Because he married Edward Hutchinson’s daughter Anne in 1660, my guess was that he trained with Edward. William (the younger), about 11 when his mother sailed, wrote that he’d trained on a ship from an early age (probably 12 or 14), but he also had some financial and royal-court influence behind him to later obtain an appointment as a royal customs inspector, so he was probably fostered or sponsored with someone well-placed in English society. Maher was 9, and Henry and Mary (unknown birth dates but presumed from later life events) were about 5 and 4. Charles was a weaned toddler when Mary left Rhode Island.

Something else that is never mentioned: The Anglo-Dutch War of 1652-53 had begun after Mary went to England. Though the official battles took place in the eastern English Channel shores, the trade war was being fought by privateers in the Caribbean and to a smaller extent, the Dutch territories in what is now New York. The coves of England from the Thames estuary to Hastings to the Lizard of Cornwall housed Dutch pirates who would venture forth and assault English ships in the channel. William Dyer was commissioned as Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas for New England, and there was very real danger of piracy, privateering (government-regulated piracy), and other mayhem on America’s shores from the Carolinas to Nova Scotia. In 1654, a ship of refugees left Recife, Brazil, heading to Manhattan, but they were kidnapped by pirates and taken to the Canary Islands (off Africa) and when released after paying ransom, they were pirated again by a French ship, which sailed them to their destination and demanded another ransom to release them.

It seems that even if Mary Dyer had intended to sail back to America within a year or two, it would have been at huge risk of life and limb. She was better off in England, and obviously, her four youngest children were cared for either by William (who was often out of town on legal or government business), or by foster parents. In my biographical novels, I called it for Anne Hutchinson’s sister Katherine Marbury Smith, who was Mary’s age, wealthy, lived in nearby Providence, and who had young children of her own. But it could have been any one of scores of families in Rhode Island or Massachusetts. Surely there would have been letters between parents and children, and foster parents to parents.

When Mary did go back to America, she sailed from Bristol with another Quaker woman whom she’d known two decades before in Boston. They left at about New Year, in 1657, and sailed well north of the risky, pirate-ridden Caribbean for eight to ten weeks—but the sea ice and severe storms of the worst years of the Little Ice Age drove them right past Cape Cod and down the coast to Barbados, where there were Quakers with whom they could take refuge. Finally, the worst winter storms abating, they left Barbados and arrived in Boston Harbor in the third week of March. They were promptly arrested and imprisoned until her husband learned of it and rescued Mary. Over the next three years, we only know of a few short periods where she appears outside of Rhode Island, with the Quakers, so she must have been at home most of the time, caring for the younger children, Maher, Henry, Mary, and Charles.

Pieter de Hooch, Woman with a Baby in her Lap,

Pieter de Hooch, Woman with a Baby in her Lap,

and a Small Child Now about William’s hints about Mary. From his letters to the hostile Boston court in 1659 and 1660, he mentions Mary with tenderness and bewilderment that she would choose death for her principles, over safety with her husband and children. He implores them with tears (he says) not to deprive his children of their mother. And he’s angry with Endecott, Bellingham, Bradstreet, and others at the harsh treatment of Mary: “Had you no commiseration of a tender soul that being wett to the skin, you cause her to thrust into a room whereon was nothing to sitt or lye down upon but dust .. had your dogg been wett you would have offered it the liberty of a chimney corner to dry itself, or had your hoggs been pend in a sty, you would have offered them some dry straw, or else you would have wanted mercy to your beast, but alas Christians now with you are used worse [than] hoggs or doggs ... oh merciless cruelties… I have written thus plainly to you, being exceedingly sensible of the unjust molestations and detaining of my deare yokefellow, mine and my familyes want of her will crye loud in yo' eares together with her sufferings of your part but I questions not mercy favor and comfort from the most high of her owne soule, that at present my self and family bea by you deprived of the comfort and refreshment we might have enjoyed by her [presence].”

In May 1660, William wrote: “… extend your mercy and favor once again to me and my children…. yourselves have been and are or may be husbands to wife or wives, so am I: yea to one most dearly beloved: oh do not you deprive me of her, but I pray give her me once again and I shall be so much obliged for ever, that I shall endeavor continually to utter my thanks and render you Love and Honor most renowned. Pity me, I beg it with tears…”

If Mary had been a bad wife or mother, or had abandoned her family to run off and “find herself,” William Dyer would not have begged for her life, or submitted to Boston’s authorities in tears. I suspect that when Mary spent that last winter at Shelter Island, William arranged it so she could be safe and it would be difficult for her to go back to Boston as she felt compelled by God to do. William had had dealings with the owner of Shelter Island, whose wife was the sister of Governor Coddington’s young wife.

But, you say, at the end, she left her six children to go to an unnecessary death. She chose to make a political statement rather than raise her children to maturity. But in the Quaker mindset, they were leaving their families in better than human hands--they went out into the world as God's call moved them, knowing that God would be a better Parent and provide for them through the fellowship of believers. The believed that they must be willing to leave "father, mother, brothers and sisters" --and children if necessary-- to take up the Cross. "He that loveth father or mother more than me, is not worthy of me. And he that loveth son, or daughter more than me, is not worthy of me." Matthew 1037 Geneva Bible.

When Mary accomplished the mission she believed God called her to do, supporting the persecuted and imprisoned who were there to testify of God’s revelations to them, and giving her life to shock the theocratic government and its people, she exhibited a love for all people, even those she didn’t know. Her sacrifice gave life and liberty to countless millions of people since.

And whether or not she is your ancestor by DNA, she is your mother by virtue of her gift of selfless love. You have liberty of conscience. You have the freedom to practice and believe what you think is best, without interference or control of a government. In that sense, Mary Dyer is a mother to all of us.

********** Christy K Robinson is author of two biographical novels on William and Mary Dyer, and a collection of her nonfiction research on the Dyers. In 1660, Mary Dyer was hanged for her civil disobedience over religious freedom, and her husband’s and friends’ efforts in that human right became a model for the United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights 130 years later. The books (and Kindle versions) are available on Amazon. CLICK HERE for the links.

Family in a Landscape, ca 1635, National Gallery, London Over the years that I’ve been researching the circumstances of Mary Dyer’s life, I’ve read articles and fielded questions in the Dyer website, wondering what kind of mother would leave her six children motherless in Rhode Island, and run off to England for five years? Why did Mary abandon her children for so long? Was she that selfish?

Family in a Landscape, ca 1635, National Gallery, London Over the years that I’ve been researching the circumstances of Mary Dyer’s life, I’ve read articles and fielded questions in the Dyer website, wondering what kind of mother would leave her six children motherless in Rhode Island, and run off to England for five years? Why did Mary abandon her children for so long? Was she that selfish? We have no record of her thoughts about her family. No journal. No letters between wife and husband, or mother and children. But we do have some hints from her husband William Dyer, in his letters to the General Court at Boston. There are English customs that have been forgotten in the intervening centuries. There was a war going on, on both sides of the Atlantic.

Between 1633 and 1650, Mary bore eight babies that we know of, though it’s possible she miscarried during the years between the babies that lived. She spent 19 years of her young adult life, bearing and raising babies.

1633: William, baptized and buried within 3 days. 1635: Samuel1637: unnamed anencephalic 7-months’ gestation girl, miscarried~1640: William 1643: Maher~1647: Henry~1648: Mary1650: Charles

Jan Steen, The Feast of St Nicholas Fosterage was a British custom from at least 500BC, when the Celts invaded the island. In the Celtic culture, people traded five- or six-year-old children for relatives’ or nobles’ children, in order to teach moral, religious, and societal values with less possibility of spoiling their heirs. The children were reared with the greatest love and respect, as well as discipline. This strengthened clan alliances and often, children were raised together, knowing they’d be married at puberty. When the Saxons invaded the islands, they brought similar customs of fosterage, and it was well-known among the Normans, who would send their boys to the guilds, knights, or the Church to be trained as squires, cavalry, infantry, farmers, clerks, or monks or priests. The girls learned the necessary skills of administering estates, nursing, midwifery, seamstressing, and many other roles. Later, as professional guilds evolved, boys of 12 or 14 were apprenticed from seven to nine years to a trade or profession, and girls were given to convents or to other families to be trained. Finally, from the English Reformation and well through the 18thcentury, when infant and child mortality were very high, parents were told not to love children too dearly so they wouldn’t be so broken when a child died of illness or injury, and they farmed children out to learn skills without the interference of doting, spoiling parents.

Jan Steen, The Feast of St Nicholas Fosterage was a British custom from at least 500BC, when the Celts invaded the island. In the Celtic culture, people traded five- or six-year-old children for relatives’ or nobles’ children, in order to teach moral, religious, and societal values with less possibility of spoiling their heirs. The children were reared with the greatest love and respect, as well as discipline. This strengthened clan alliances and often, children were raised together, knowing they’d be married at puberty. When the Saxons invaded the islands, they brought similar customs of fosterage, and it was well-known among the Normans, who would send their boys to the guilds, knights, or the Church to be trained as squires, cavalry, infantry, farmers, clerks, or monks or priests. The girls learned the necessary skills of administering estates, nursing, midwifery, seamstressing, and many other roles. Later, as professional guilds evolved, boys of 12 or 14 were apprenticed from seven to nine years to a trade or profession, and girls were given to convents or to other families to be trained. Finally, from the English Reformation and well through the 18thcentury, when infant and child mortality were very high, parents were told not to love children too dearly so they wouldn’t be so broken when a child died of illness or injury, and they farmed children out to learn skills without the interference of doting, spoiling parents.William Dyer served nine years as an apprentice in London, 125 miles from his parents’ home. We don’t know Mary’s background, but she was well-educated, and was a skilled writer when most women could read a little but not write, and not even every man could write. It’s possible that Mary had a private tutor, or she was encouraged by a foster parent.

So you see, putting your children in fosterage was not abandoning them. It was done with the best of intentions, and indeed love, to ensure their future as useful members of society.

When Mary left for England in early 1652, she almost surely did not expect to stay there for five years! War and God's call changed her trajectory.

Samuel (the Dyer’s eldest and the heir) would have been 16 and well into his training. Because he married Edward Hutchinson’s daughter Anne in 1660, my guess was that he trained with Edward. William (the younger), about 11 when his mother sailed, wrote that he’d trained on a ship from an early age (probably 12 or 14), but he also had some financial and royal-court influence behind him to later obtain an appointment as a royal customs inspector, so he was probably fostered or sponsored with someone well-placed in English society. Maher was 9, and Henry and Mary (unknown birth dates but presumed from later life events) were about 5 and 4. Charles was a weaned toddler when Mary left Rhode Island.

Something else that is never mentioned: The Anglo-Dutch War of 1652-53 had begun after Mary went to England. Though the official battles took place in the eastern English Channel shores, the trade war was being fought by privateers in the Caribbean and to a smaller extent, the Dutch territories in what is now New York. The coves of England from the Thames estuary to Hastings to the Lizard of Cornwall housed Dutch pirates who would venture forth and assault English ships in the channel. William Dyer was commissioned as Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas for New England, and there was very real danger of piracy, privateering (government-regulated piracy), and other mayhem on America’s shores from the Carolinas to Nova Scotia. In 1654, a ship of refugees left Recife, Brazil, heading to Manhattan, but they were kidnapped by pirates and taken to the Canary Islands (off Africa) and when released after paying ransom, they were pirated again by a French ship, which sailed them to their destination and demanded another ransom to release them.

It seems that even if Mary Dyer had intended to sail back to America within a year or two, it would have been at huge risk of life and limb. She was better off in England, and obviously, her four youngest children were cared for either by William (who was often out of town on legal or government business), or by foster parents. In my biographical novels, I called it for Anne Hutchinson’s sister Katherine Marbury Smith, who was Mary’s age, wealthy, lived in nearby Providence, and who had young children of her own. But it could have been any one of scores of families in Rhode Island or Massachusetts. Surely there would have been letters between parents and children, and foster parents to parents.

When Mary did go back to America, she sailed from Bristol with another Quaker woman whom she’d known two decades before in Boston. They left at about New Year, in 1657, and sailed well north of the risky, pirate-ridden Caribbean for eight to ten weeks—but the sea ice and severe storms of the worst years of the Little Ice Age drove them right past Cape Cod and down the coast to Barbados, where there were Quakers with whom they could take refuge. Finally, the worst winter storms abating, they left Barbados and arrived in Boston Harbor in the third week of March. They were promptly arrested and imprisoned until her husband learned of it and rescued Mary. Over the next three years, we only know of a few short periods where she appears outside of Rhode Island, with the Quakers, so she must have been at home most of the time, caring for the younger children, Maher, Henry, Mary, and Charles.

Pieter de Hooch, Woman with a Baby in her Lap,

Pieter de Hooch, Woman with a Baby in her Lap, and a Small Child Now about William’s hints about Mary. From his letters to the hostile Boston court in 1659 and 1660, he mentions Mary with tenderness and bewilderment that she would choose death for her principles, over safety with her husband and children. He implores them with tears (he says) not to deprive his children of their mother. And he’s angry with Endecott, Bellingham, Bradstreet, and others at the harsh treatment of Mary: “Had you no commiseration of a tender soul that being wett to the skin, you cause her to thrust into a room whereon was nothing to sitt or lye down upon but dust .. had your dogg been wett you would have offered it the liberty of a chimney corner to dry itself, or had your hoggs been pend in a sty, you would have offered them some dry straw, or else you would have wanted mercy to your beast, but alas Christians now with you are used worse [than] hoggs or doggs ... oh merciless cruelties… I have written thus plainly to you, being exceedingly sensible of the unjust molestations and detaining of my deare yokefellow, mine and my familyes want of her will crye loud in yo' eares together with her sufferings of your part but I questions not mercy favor and comfort from the most high of her owne soule, that at present my self and family bea by you deprived of the comfort and refreshment we might have enjoyed by her [presence].”

In May 1660, William wrote: “… extend your mercy and favor once again to me and my children…. yourselves have been and are or may be husbands to wife or wives, so am I: yea to one most dearly beloved: oh do not you deprive me of her, but I pray give her me once again and I shall be so much obliged for ever, that I shall endeavor continually to utter my thanks and render you Love and Honor most renowned. Pity me, I beg it with tears…”

If Mary had been a bad wife or mother, or had abandoned her family to run off and “find herself,” William Dyer would not have begged for her life, or submitted to Boston’s authorities in tears. I suspect that when Mary spent that last winter at Shelter Island, William arranged it so she could be safe and it would be difficult for her to go back to Boston as she felt compelled by God to do. William had had dealings with the owner of Shelter Island, whose wife was the sister of Governor Coddington’s young wife.

But, you say, at the end, she left her six children to go to an unnecessary death. She chose to make a political statement rather than raise her children to maturity. But in the Quaker mindset, they were leaving their families in better than human hands--they went out into the world as God's call moved them, knowing that God would be a better Parent and provide for them through the fellowship of believers. The believed that they must be willing to leave "father, mother, brothers and sisters" --and children if necessary-- to take up the Cross. "He that loveth father or mother more than me, is not worthy of me. And he that loveth son, or daughter more than me, is not worthy of me." Matthew 1037 Geneva Bible.

When Mary accomplished the mission she believed God called her to do, supporting the persecuted and imprisoned who were there to testify of God’s revelations to them, and giving her life to shock the theocratic government and its people, she exhibited a love for all people, even those she didn’t know. Her sacrifice gave life and liberty to countless millions of people since.

And whether or not she is your ancestor by DNA, she is your mother by virtue of her gift of selfless love. You have liberty of conscience. You have the freedom to practice and believe what you think is best, without interference or control of a government. In that sense, Mary Dyer is a mother to all of us.

********** Christy K Robinson is author of two biographical novels on William and Mary Dyer, and a collection of her nonfiction research on the Dyers. In 1660, Mary Dyer was hanged for her civil disobedience over religious freedom, and her husband’s and friends’ efforts in that human right became a model for the United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights 130 years later. The books (and Kindle versions) are available on Amazon. CLICK HERE for the links.

Published on May 11, 2014 00:00

April 22, 2014

*Mary Dyer Illuminated* Kindle sale for limited time

SALE on the Kindle edition of Mary Dyer Illuminated . Please take advantage of the incremental sale April 25-29, 2014, and please SHARE on Facebook and Twitter.

Tell your friends and family, people at work, people at church (choir, ministers, members), people who enjoy history, genealogy, culture, England and New England, and stories about America's FIRST founders, the great-grandparents of the nation's founders.

http://amzn.to/1rl8sEV

See the image for info about the lowest prices and times, and the free Kindle reading app.

If you've already read the book in paperback or Kindle, please leave a review on Amazon and Goodreads. Thank you for your support!

Published on April 22, 2014 23:13

April 21, 2014

William Dyer co-founds Newport, RI in 1639

And for the first time anywhere, learn who the

FEMALE co-founders of Newport were!

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

William Dyer was 28 years old when he co-founded Portsmouth, Rhode Island, in 1638. (It was called by its native American name, Pocasset, at the time.) His name appears on the Portsmouth Compact with the other men who bought Aquidneck Island from the natives.

He was 29 years old on April 28, 1639, when he co-founded the city of Newport, Rhode Island and signed the Newport Compact. As clerk of the town, and later Secretary of the colony, it's almost surely William Dyer's handwriting that headed the compact that the founders signed.

Newport Compact -- click to enlarge

Newport Compact -- click to enlarge

Battery Park in Newport, formerly Dyer's Point, is on land

Battery Park in Newport, formerly Dyer's Point, is on land

where Mary and William Dyer had their farm.

After the town was legally incorporated came the distribution of community, home, and farm land parcels, and, of course, the streets and highways. William Dyer was one of the small commission that surveyed and apportioned the lots and boundaries. The following records are scanned from Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in New England, Vol. 1, 1636-1663. (I added the modern dates.)

For a modern map of the city of Newport,

For a modern map of the city of Newport,

with labels for its harbor walk which would take you

along the western edge of 17th-century Dyer land, click here.

Historical records mention only the men who attended assembly meetings, voted, held court, or signed documents, but the women should be remembered for their many sacrifices in moving the household, servants, small children, livestock, and possessions, and starting in a new, rugged place where they lived in wigwams while their first houses were being built. It was the Little Ice Age, and winters were longer and more severe than we experience now. They had just settled in Boston for a few months to four years when they were exiled and had to start again in the wilderness of Rhode Island. A year later, some of the settlers at Portsmouth began again at Newport.

Unidentified English family circa 1640.Newport's female co-founders were:

Unidentified English family circa 1640.Newport's female co-founders were:

******************* ******************* *******************

Christy K Robinson is author of two biographical novels on William and Mary Dyer, and a collection of her nonfiction research on the Dyers. Key characters are Anne Hutchinson, Edward Hutchinson, John Winthrop, Katherine and Richard Scott, Roger Williams, Dr. John Clarke, Nicholas Easton, John Endecott, Henry Vane the Younger, and others.

Christy K Robinson is author of two biographical novels on William and Mary Dyer, and a collection of her nonfiction research on the Dyers. Key characters are Anne Hutchinson, Edward Hutchinson, John Winthrop, Katherine and Richard Scott, Roger Williams, Dr. John Clarke, Nicholas Easton, John Endecott, Henry Vane the Younger, and others.

The books (and Kindle versions) are available on Amazon. CLICK HERE for the links.

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

© 2014 Christy K Robinson William Dyer was 28 years old when he co-founded Portsmouth, Rhode Island, in 1638. (It was called by its native American name, Pocasset, at the time.) His name appears on the Portsmouth Compact with the other men who bought Aquidneck Island from the natives.

He was 29 years old on April 28, 1639, when he co-founded the city of Newport, Rhode Island and signed the Newport Compact. As clerk of the town, and later Secretary of the colony, it's almost surely William Dyer's handwriting that headed the compact that the founders signed.

Newport Compact -- click to enlarge

Newport Compact -- click to enlarge

Battery Park in Newport, formerly Dyer's Point, is on land

Battery Park in Newport, formerly Dyer's Point, is on land where Mary and William Dyer had their farm.

After the town was legally incorporated came the distribution of community, home, and farm land parcels, and, of course, the streets and highways. William Dyer was one of the small commission that surveyed and apportioned the lots and boundaries. The following records are scanned from Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in New England, Vol. 1, 1636-1663. (I added the modern dates.)

For a modern map of the city of Newport,

For a modern map of the city of Newport, with labels for its harbor walk which would take you

along the western edge of 17th-century Dyer land, click here.

Historical records mention only the men who attended assembly meetings, voted, held court, or signed documents, but the women should be remembered for their many sacrifices in moving the household, servants, small children, livestock, and possessions, and starting in a new, rugged place where they lived in wigwams while their first houses were being built. It was the Little Ice Age, and winters were longer and more severe than we experience now. They had just settled in Boston for a few months to four years when they were exiled and had to start again in the wilderness of Rhode Island. A year later, some of the settlers at Portsmouth began again at Newport.

Unidentified English family circa 1640.Newport's female co-founders were:

Unidentified English family circa 1640.Newport's female co-founders were:William Coddington and MaryMosely Coddington Nicholas Easton (widowed, 2 sons, married widow Christiana Beecher later in 1638)John Coggeshall and Mary___ Coggeshall, 7 childrenWilliam Brenton and Dorothy____ BrentonJohn Clarke and ElizabethHarges ClarkeJeremy Clarke and FrancesLatham Dungan Clarke, 4 Dungan childrenThomas Hazard and MarthaPotter Hazard, 5 childrenHenry Bull and Elizabeth___ Bull, 1 childWilliam Dyer and MaryBarrett Dyer, 1 child

******************* ******************* *******************

Christy K Robinson is author of two biographical novels on William and Mary Dyer, and a collection of her nonfiction research on the Dyers. Key characters are Anne Hutchinson, Edward Hutchinson, John Winthrop, Katherine and Richard Scott, Roger Williams, Dr. John Clarke, Nicholas Easton, John Endecott, Henry Vane the Younger, and others.

Christy K Robinson is author of two biographical novels on William and Mary Dyer, and a collection of her nonfiction research on the Dyers. Key characters are Anne Hutchinson, Edward Hutchinson, John Winthrop, Katherine and Richard Scott, Roger Williams, Dr. John Clarke, Nicholas Easton, John Endecott, Henry Vane the Younger, and others.The books (and Kindle versions) are available on Amazon. CLICK HERE for the links.

Published on April 21, 2014 00:00

April 14, 2014

Bronx street named after Dyer son, mayor of NYC

© 2014 Christy K Robinson

In the borough of Bronx, New York, a street is named for Mary and William Dyer’s son, Maj. William Dyre (as his father and he spelled it), mayor of New York City in 1680-81. This William was born in Newport, Rhode Island, possibly about 1640, and died in the spring of 1688.

North-South streets in the area were named in honor of New York state governors and mayoralty, so William Dyre probably did not own land here. He owned several acres of property in the 1670s between Maiden Lane and Wall Street (the wall having much to do with his father, Capt. William Dyer!) on Manhattan Island for a few years. William also owned Dyer Island by deed from his father, and he purchased land in Rhode Island and large tracts of land in the Delaware area.

Dyre Avenue in the borough of Bronx, New York, is marked with the A pin.

Dyre Avenue in the borough of Bronx, New York, is marked with the A pin. It's very close to the Hutchinson farm where Anne Marbury Hutchinson and her younger children

were murdered in 1643.