Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 11

June 12, 2015

How Sabbath and ‘The Book of Sports’ drove 35,000 Puritans to America

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

(Click highlighted words to open a new tab with related article.)

When we think of "Sabbath" today, we think of taking a break or a sabbatical. When our ancestors "remembered the Sabbath day to keep it holy," they took their lives in their hands.

When we think of "Sabbath" today, we think of taking a break or a sabbatical. When our ancestors "remembered the Sabbath day to keep it holy," they took their lives in their hands.

The English Parliament of 1584-1585, on behalf of the growing Puritan movement, passed a bill requiring strict observance of the Sabbath (Sunday, the first day of the week), which forbade markets and fairs, and recreation such as bear-baiting, hunting, hawking, and rowing barges—during church services (either the afternoon wasn’t as much of an issue, or they intended to take up the matter of the entire day at a later time). It was discussed for eight days over two weeks before passing and being sent to the Queen. That this Bill concerning the Sabbath, as hath been before observed, was long in passing the two Houses, and much debated betwixt them, being committed, and Amendments upon Amendments added unto it, which as appeareth in this place was the cause of some Disputation between the Lords and the said Commons. Source: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/jrnl-parliament-eliz1/pp321-331

Queen Elizabeth I vetoed the bill, in line with her policy of religious tolerance in her realm. (Though Catholics were still on the Naughty List for decades to come.) And yet at last when it was agreed on by both the said Houses, it was dashed by her Majestyat the last day of this Parliament, upon that prejudicated and ill followed Principle (as may be conjectured) that she would suffer nothing to be altered in matter of Religion or Ecclesiastical Government.

Queen Elizabeth I vetoed the bill, in line with her policy of religious tolerance in her realm. (Though Catholics were still on the Naughty List for decades to come.) And yet at last when it was agreed on by both the said Houses, it was dashed by her Majestyat the last day of this Parliament, upon that prejudicated and ill followed Principle (as may be conjectured) that she would suffer nothing to be altered in matter of Religion or Ecclesiastical Government.

(That sounds like the parliamentary recorder/secretary disagreed with the Queen's decision!)

Puritan Nicholas Bownde wrote a scholarly book in 1595, True Doctrine of the Sabbath , urging Christians to sanctify the Sabbath as a day of meditation and spiritual exercises (morning and afternoon preaching services). These Sabbaths were meant to follow the Old Testament verses about keeping the Sabbath holy by not working or “doing your own pleasure” on that special day, as it was a moral imperative. They were to be solemn and sober, with no secular speech or acts. Queen Elizabeth and the Archbishop of Canterbury decreed that copies of the book be collected and burned in 1600 and 1601.

In 1601, the House of Commons passed a bill that only restricted markets and fairs on Sundays, but the House of Lords killed it. Queen Elizabeth died two years later, and King James I came to the throne. His authority was threatened by Puritans and other Calvinist dissenters (like the group who became the Pilgrims), whose influence was growing ever stronger and whose sermons and pronouncements conflicted with the King’s authority. One of his first acts was to commission a new version of the Bible which stressed the sovereignty of God and the hierarchy of worldly kings and princes, and the Authorized Version (or as many of us know it, the King James Version—KJV) was published in 1611.

However, those dissenters continued to agitate all over England. In 1617-18, the King went on a progress through the country, holding courts and meeting his subjects. One of the complaints he heard was that the usual work week being Monday through Saturday, from dawn to dusk, people needed time for recreation, markets, fun fairs, visiting family, and the like. People were required to attend services on Sunday morning, but needed the afternoon break. And the Puritans were stopping that by holding two long services on Sunday.

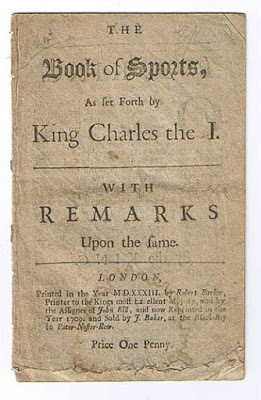

As answer to the problem of overwork and an unbalanced life—and that should he need soldiers for war, they’d be puny and weak—King James wrote

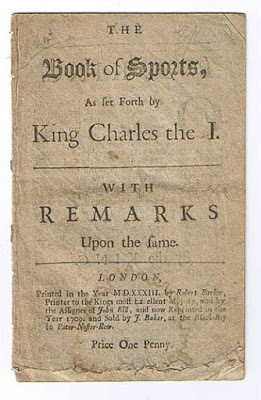

The Book of Sports

. In modern terms, it uses three pages of 12-point, single-space type, so it wasn’t large, but it was mighty! The book directed his subjects to go to church on Sunday morning and religious holidays as required, but to spend the afternoon enjoying life. He commanded that “no lawful recreation shall be barred to our good people,” and listed appropriate activities for those days: such as dancing, either men or women; archery for men, leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation, nor from having of May-games, Whitsun-ales, and Morris-dances; and the setting up of May-poles and other sports therewith used: so as the same be had in due and convenient time, without impediment or neglect of divine service: and that women shall have leave to carry rushes to the church for the decorating of it, according to their old custom; but withal we do here account still as prohibited all unlawful games to be used upon Sundays only, as bear and bull-baitings, interludes and at all times in the meaner sort of people by law prohibited, bowling.

As answer to the problem of overwork and an unbalanced life—and that should he need soldiers for war, they’d be puny and weak—King James wrote

The Book of Sports

. In modern terms, it uses three pages of 12-point, single-space type, so it wasn’t large, but it was mighty! The book directed his subjects to go to church on Sunday morning and religious holidays as required, but to spend the afternoon enjoying life. He commanded that “no lawful recreation shall be barred to our good people,” and listed appropriate activities for those days: such as dancing, either men or women; archery for men, leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation, nor from having of May-games, Whitsun-ales, and Morris-dances; and the setting up of May-poles and other sports therewith used: so as the same be had in due and convenient time, without impediment or neglect of divine service: and that women shall have leave to carry rushes to the church for the decorating of it, according to their old custom; but withal we do here account still as prohibited all unlawful games to be used upon Sundays only, as bear and bull-baitings, interludes and at all times in the meaner sort of people by law prohibited, bowling.

Really? Bowling? That could be because one objective was to win the most points by knocking down the kingpin (was that seen as sedition?), or because of this: The Character of a Bowling-Alley and Bowling-Green A Bowling-Green, or Bowling-Ally is a place where three things are thrown away besides the Bowls, viz. Time, Money, and Curses, at the last ten for one. Source: http://www.greydragon.org/library/playingbowls.html

Catholics and non-conformists were barred from Sunday recreation because they didn’t attend approved Church of England services. Further, the King commanded that The Book of Sports be read in every church, and held the bishops, ministers, and churchwardens accountable that it should be done “by the book.”

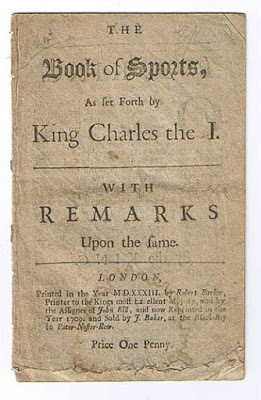

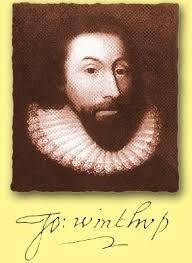

King James died in 1625, and the book was reissued several times by his son, Charles I. Charles and the Parliament were at odds over authority and taxation, and the Scots and English churches were in conflict with their respective archbishops, Spottiswoode and Laud. In an attempt to control the Puritan (and other non-conformists) uprising, King Charles decreed that The Book of Sports be read again in all churches, and churches must conform to CofE’s Book of Common Prayer—which was also a hated book . If Puritan ministers would not conform, they were “silenced” (removed from the pulpit and not licensed to preach) and some were put in prison. And prison could be a death sentence. …the Bishop, and all other inferior churchmen and churchwardens, shall for their parts be careful and diligent, both to instruct the ignorant, and convince and reform them that are misled in religion, presenting them that will not conform themselves, but obstinately stand out, to our Judges and Justices: whom we likewise command to put the law in due execution against them.

However, there was a clause in Sports that many Puritan ministers latched onto. ...either constraining them to conform themselves or to leave the county.

Leave the country.

The thing is, the King didn't want them to leave the country because he would lose out on all that lovely tax base. If they sneaked out, they couldn’t go to Catholic France or Spain, and Lutheran (pretty close to Catholic!) Germany and Austria were at war with France, Italy, and Spain. Some, like the Pilgrims of Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, went to the Netherlands for ten years before they sailed to Plymouth. One of their leaders, their pastor John Robinson, is my ancestor 12 generations back. His treatise on the Sabbath, A Just and Necessary Apology, was published in 1625, the year he died.

For the vast majority of Puritans, though, there was no place to go but America, still under English rule, but a safe 3,000 miles by ocean journey away from the King and archbishops.

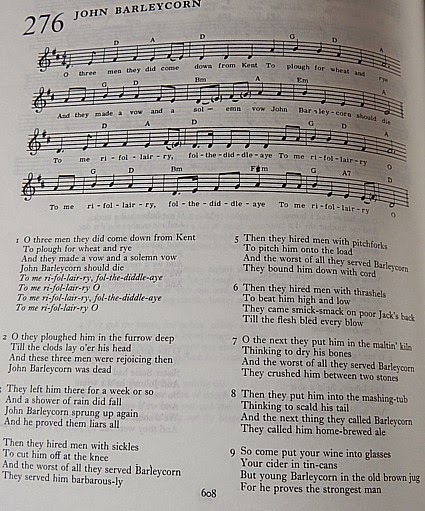

Some ministers escaped the long arm of the law by hiding with the help of sympathizers like the Earl of Lincoln—until the Earl was imprisoned. The senior pastor of the Boston St. Botolph’s, Rev. John Cotton, was one of the many ministers who had to hide before escaping to New England. Ten percent of the citizens of Boston, Lincolnshire, emigrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony with or shortly after John Cotton went there. (Cotton had been asked to come to Massachusetts several times, but declined until he was pushed out of England by fear of prison.)

William and Anne Marbury Hutchinson followed Rev. Cotton to Boston. William and Mary Dyer were married in the Anglican church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, but in 1635 were admitted to the Puritan membership in Boston’s First Church (and they were exiled from it in 1638).

Entire towns in Essex and many other counties emptied and sailed to the new Boston between 1630 and 1640. It’s estimated that about 35,000 people moved to New England during that decade. When the English Civil Wars began, with Puritans in ascendancy, thousands of the emigrants moved back to England. In May 1643, The Book of Sports was burned by angry Puritans.

Puritans now controlled the government, and they burned the hated

Puritans now controlled the government, and they burned the hated

"Book of Sports" in May 1643.

People who had had such a threat of persecution and death were deeply convicted of the truth of their beliefs. They followed the Ten Commandments and other Old Testament laws to the letter, to prove to God that they were worthy of salvation. The fourth commandment, to keep the Sabbath holy, was one of the factors that caused their persecution in the first place. Obedience to God was worth moving across the world, or dying for.

Both on the ships, and in New England, they followed their stringent regulations about Sabbath-keeping. The English church holidays like Christmas and Easter were prohibited, and people were expected to work as usual. Church services with required attendance were held morning and afternoon on Sundays. During the Sabbath there was no alcohol consumption, no unseemly walking, no court or corporal punishment, no work that could be done another day (like laundry or beer brewing), no swimming, no buying or selling, no games or dances, no unnecessary travel, no hunting or fishing. The music or literature was sacred, never secular. Sabbath began at sundown on Saturday evening and ended during the night before Monday.

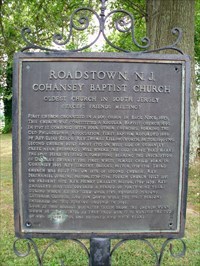

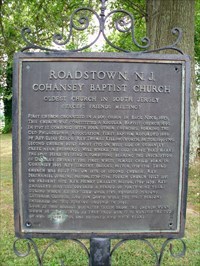

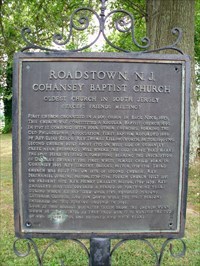

I had ancestors in the Salem, Massachusetts, area who emigrated there as Puritans, fleeing The Book of Sports style of Christianity. But at some point they converted to Baptist beliefs and risked beatings, fines, and imprisonment. They moved to New Jersey and formed a town and congregation there. They became Sabbatarians (seventh-day/Saturday was their holy day) in the 1710s and shared their Baptist minister with a first-day congregation. That branch stayed Seventh-day Baptist from then until the 20th century.

I had ancestors in the Salem, Massachusetts, area who emigrated there as Puritans, fleeing The Book of Sports style of Christianity. But at some point they converted to Baptist beliefs and risked beatings, fines, and imprisonment. They moved to New Jersey and formed a town and congregation there. They became Sabbatarians (seventh-day/Saturday was their holy day) in the 1710s and shared their Baptist minister with a first-day congregation. That branch stayed Seventh-day Baptist from then until the 20th century.

Some people who are from, or still in, Sabbatarian denominations (Seventh-day Adventist, Seventh-day Baptist, Church of God, etc.) have experienced that list of prohibitions, and it doesn’t seem foreign at all. Some see that 17th-century culture and marvel at the legalism of the Puritans and their spiritual descendants. But perhaps we can look at that strength of character, that integrity, that obey-God-rather-than-men resolve, and admire them. We can remember that we carry the DNA of those godly pioneers in our bodies and that moral fiber in our culture.

All these people were still living by faith when they died. They did not receive the things promised; they only saw them and welcomed them from a distance, admitting that they were foreigners and strangers on earth. People who say such things show that they are looking for a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have had opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country—a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared a city for them. Hebrews 11:13-16 NIV.

(Click highlighted words to open a new tab with related article.)

When we think of "Sabbath" today, we think of taking a break or a sabbatical. When our ancestors "remembered the Sabbath day to keep it holy," they took their lives in their hands.

When we think of "Sabbath" today, we think of taking a break or a sabbatical. When our ancestors "remembered the Sabbath day to keep it holy," they took their lives in their hands.The English Parliament of 1584-1585, on behalf of the growing Puritan movement, passed a bill requiring strict observance of the Sabbath (Sunday, the first day of the week), which forbade markets and fairs, and recreation such as bear-baiting, hunting, hawking, and rowing barges—during church services (either the afternoon wasn’t as much of an issue, or they intended to take up the matter of the entire day at a later time). It was discussed for eight days over two weeks before passing and being sent to the Queen. That this Bill concerning the Sabbath, as hath been before observed, was long in passing the two Houses, and much debated betwixt them, being committed, and Amendments upon Amendments added unto it, which as appeareth in this place was the cause of some Disputation between the Lords and the said Commons. Source: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/jrnl-parliament-eliz1/pp321-331

Queen Elizabeth I vetoed the bill, in line with her policy of religious tolerance in her realm. (Though Catholics were still on the Naughty List for decades to come.) And yet at last when it was agreed on by both the said Houses, it was dashed by her Majestyat the last day of this Parliament, upon that prejudicated and ill followed Principle (as may be conjectured) that she would suffer nothing to be altered in matter of Religion or Ecclesiastical Government.

Queen Elizabeth I vetoed the bill, in line with her policy of religious tolerance in her realm. (Though Catholics were still on the Naughty List for decades to come.) And yet at last when it was agreed on by both the said Houses, it was dashed by her Majestyat the last day of this Parliament, upon that prejudicated and ill followed Principle (as may be conjectured) that she would suffer nothing to be altered in matter of Religion or Ecclesiastical Government.(That sounds like the parliamentary recorder/secretary disagreed with the Queen's decision!)

Puritan Nicholas Bownde wrote a scholarly book in 1595, True Doctrine of the Sabbath , urging Christians to sanctify the Sabbath as a day of meditation and spiritual exercises (morning and afternoon preaching services). These Sabbaths were meant to follow the Old Testament verses about keeping the Sabbath holy by not working or “doing your own pleasure” on that special day, as it was a moral imperative. They were to be solemn and sober, with no secular speech or acts. Queen Elizabeth and the Archbishop of Canterbury decreed that copies of the book be collected and burned in 1600 and 1601.

In 1601, the House of Commons passed a bill that only restricted markets and fairs on Sundays, but the House of Lords killed it. Queen Elizabeth died two years later, and King James I came to the throne. His authority was threatened by Puritans and other Calvinist dissenters (like the group who became the Pilgrims), whose influence was growing ever stronger and whose sermons and pronouncements conflicted with the King’s authority. One of his first acts was to commission a new version of the Bible which stressed the sovereignty of God and the hierarchy of worldly kings and princes, and the Authorized Version (or as many of us know it, the King James Version—KJV) was published in 1611.

However, those dissenters continued to agitate all over England. In 1617-18, the King went on a progress through the country, holding courts and meeting his subjects. One of the complaints he heard was that the usual work week being Monday through Saturday, from dawn to dusk, people needed time for recreation, markets, fun fairs, visiting family, and the like. People were required to attend services on Sunday morning, but needed the afternoon break. And the Puritans were stopping that by holding two long services on Sunday.

As answer to the problem of overwork and an unbalanced life—and that should he need soldiers for war, they’d be puny and weak—King James wrote

The Book of Sports

. In modern terms, it uses three pages of 12-point, single-space type, so it wasn’t large, but it was mighty! The book directed his subjects to go to church on Sunday morning and religious holidays as required, but to spend the afternoon enjoying life. He commanded that “no lawful recreation shall be barred to our good people,” and listed appropriate activities for those days: such as dancing, either men or women; archery for men, leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation, nor from having of May-games, Whitsun-ales, and Morris-dances; and the setting up of May-poles and other sports therewith used: so as the same be had in due and convenient time, without impediment or neglect of divine service: and that women shall have leave to carry rushes to the church for the decorating of it, according to their old custom; but withal we do here account still as prohibited all unlawful games to be used upon Sundays only, as bear and bull-baitings, interludes and at all times in the meaner sort of people by law prohibited, bowling.

As answer to the problem of overwork and an unbalanced life—and that should he need soldiers for war, they’d be puny and weak—King James wrote

The Book of Sports

. In modern terms, it uses three pages of 12-point, single-space type, so it wasn’t large, but it was mighty! The book directed his subjects to go to church on Sunday morning and religious holidays as required, but to spend the afternoon enjoying life. He commanded that “no lawful recreation shall be barred to our good people,” and listed appropriate activities for those days: such as dancing, either men or women; archery for men, leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation, nor from having of May-games, Whitsun-ales, and Morris-dances; and the setting up of May-poles and other sports therewith used: so as the same be had in due and convenient time, without impediment or neglect of divine service: and that women shall have leave to carry rushes to the church for the decorating of it, according to their old custom; but withal we do here account still as prohibited all unlawful games to be used upon Sundays only, as bear and bull-baitings, interludes and at all times in the meaner sort of people by law prohibited, bowling.Really? Bowling? That could be because one objective was to win the most points by knocking down the kingpin (was that seen as sedition?), or because of this: The Character of a Bowling-Alley and Bowling-Green A Bowling-Green, or Bowling-Ally is a place where three things are thrown away besides the Bowls, viz. Time, Money, and Curses, at the last ten for one. Source: http://www.greydragon.org/library/playingbowls.html

Catholics and non-conformists were barred from Sunday recreation because they didn’t attend approved Church of England services. Further, the King commanded that The Book of Sports be read in every church, and held the bishops, ministers, and churchwardens accountable that it should be done “by the book.”

King James died in 1625, and the book was reissued several times by his son, Charles I. Charles and the Parliament were at odds over authority and taxation, and the Scots and English churches were in conflict with their respective archbishops, Spottiswoode and Laud. In an attempt to control the Puritan (and other non-conformists) uprising, King Charles decreed that The Book of Sports be read again in all churches, and churches must conform to CofE’s Book of Common Prayer—which was also a hated book . If Puritan ministers would not conform, they were “silenced” (removed from the pulpit and not licensed to preach) and some were put in prison. And prison could be a death sentence. …the Bishop, and all other inferior churchmen and churchwardens, shall for their parts be careful and diligent, both to instruct the ignorant, and convince and reform them that are misled in religion, presenting them that will not conform themselves, but obstinately stand out, to our Judges and Justices: whom we likewise command to put the law in due execution against them.

However, there was a clause in Sports that many Puritan ministers latched onto. ...either constraining them to conform themselves or to leave the county.

Leave the country.

The thing is, the King didn't want them to leave the country because he would lose out on all that lovely tax base. If they sneaked out, they couldn’t go to Catholic France or Spain, and Lutheran (pretty close to Catholic!) Germany and Austria were at war with France, Italy, and Spain. Some, like the Pilgrims of Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, went to the Netherlands for ten years before they sailed to Plymouth. One of their leaders, their pastor John Robinson, is my ancestor 12 generations back. His treatise on the Sabbath, A Just and Necessary Apology, was published in 1625, the year he died.

For the vast majority of Puritans, though, there was no place to go but America, still under English rule, but a safe 3,000 miles by ocean journey away from the King and archbishops.

Some ministers escaped the long arm of the law by hiding with the help of sympathizers like the Earl of Lincoln—until the Earl was imprisoned. The senior pastor of the Boston St. Botolph’s, Rev. John Cotton, was one of the many ministers who had to hide before escaping to New England. Ten percent of the citizens of Boston, Lincolnshire, emigrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony with or shortly after John Cotton went there. (Cotton had been asked to come to Massachusetts several times, but declined until he was pushed out of England by fear of prison.)

William and Anne Marbury Hutchinson followed Rev. Cotton to Boston. William and Mary Dyer were married in the Anglican church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, but in 1635 were admitted to the Puritan membership in Boston’s First Church (and they were exiled from it in 1638).

Entire towns in Essex and many other counties emptied and sailed to the new Boston between 1630 and 1640. It’s estimated that about 35,000 people moved to New England during that decade. When the English Civil Wars began, with Puritans in ascendancy, thousands of the emigrants moved back to England. In May 1643, The Book of Sports was burned by angry Puritans.

Puritans now controlled the government, and they burned the hated

Puritans now controlled the government, and they burned the hated "Book of Sports" in May 1643.

People who had had such a threat of persecution and death were deeply convicted of the truth of their beliefs. They followed the Ten Commandments and other Old Testament laws to the letter, to prove to God that they were worthy of salvation. The fourth commandment, to keep the Sabbath holy, was one of the factors that caused their persecution in the first place. Obedience to God was worth moving across the world, or dying for.

Both on the ships, and in New England, they followed their stringent regulations about Sabbath-keeping. The English church holidays like Christmas and Easter were prohibited, and people were expected to work as usual. Church services with required attendance were held morning and afternoon on Sundays. During the Sabbath there was no alcohol consumption, no unseemly walking, no court or corporal punishment, no work that could be done another day (like laundry or beer brewing), no swimming, no buying or selling, no games or dances, no unnecessary travel, no hunting or fishing. The music or literature was sacred, never secular. Sabbath began at sundown on Saturday evening and ended during the night before Monday.

I had ancestors in the Salem, Massachusetts, area who emigrated there as Puritans, fleeing The Book of Sports style of Christianity. But at some point they converted to Baptist beliefs and risked beatings, fines, and imprisonment. They moved to New Jersey and formed a town and congregation there. They became Sabbatarians (seventh-day/Saturday was their holy day) in the 1710s and shared their Baptist minister with a first-day congregation. That branch stayed Seventh-day Baptist from then until the 20th century.

I had ancestors in the Salem, Massachusetts, area who emigrated there as Puritans, fleeing The Book of Sports style of Christianity. But at some point they converted to Baptist beliefs and risked beatings, fines, and imprisonment. They moved to New Jersey and formed a town and congregation there. They became Sabbatarians (seventh-day/Saturday was their holy day) in the 1710s and shared their Baptist minister with a first-day congregation. That branch stayed Seventh-day Baptist from then until the 20th century. Some people who are from, or still in, Sabbatarian denominations (Seventh-day Adventist, Seventh-day Baptist, Church of God, etc.) have experienced that list of prohibitions, and it doesn’t seem foreign at all. Some see that 17th-century culture and marvel at the legalism of the Puritans and their spiritual descendants. But perhaps we can look at that strength of character, that integrity, that obey-God-rather-than-men resolve, and admire them. We can remember that we carry the DNA of those godly pioneers in our bodies and that moral fiber in our culture.

All these people were still living by faith when they died. They did not receive the things promised; they only saw them and welcomed them from a distance, admitting that they were foreigners and strangers on earth. People who say such things show that they are looking for a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have had opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country—a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared a city for them. Hebrews 11:13-16 NIV.

Published on June 12, 2015 23:15

How ‘The Book of Sports’ drove 35,000 Puritans to America

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

(Click highlighted words to open a new tab with related article.)

When we think of "Sabbath" today, we think of taking a break or a sabbatical. When our ancestors "remembered the Sabbath day to keep it holy," they took their lives in their hands. The English Parliament of 1584-1585, on behalf of the growing Puritan movement, passed a bill requiring strict observance of the Sabbath (Sunday, the first day of the week), which forbade markets and fairs, and recreation such as bear-baiting, hunting, hawking, and rowing barges—during church services (either the afternoon wasn’t as much of an issue, or they intended to take up the matter of the entire day at a later time). It was discussed for eight days over two weeks before passing and being sent to the Queen. That this Bill concerning the Sabbath, as hath been before observed, was long in passing the two Houses, and much debated betwixt them, being committed, and Amendments upon Amendments added unto it, which as appeareth in this place was the cause of some Disputation between the Lords and the said Commons. Source: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/jrnl-parliament-eliz1/pp321-331

When we think of "Sabbath" today, we think of taking a break or a sabbatical. When our ancestors "remembered the Sabbath day to keep it holy," they took their lives in their hands. The English Parliament of 1584-1585, on behalf of the growing Puritan movement, passed a bill requiring strict observance of the Sabbath (Sunday, the first day of the week), which forbade markets and fairs, and recreation such as bear-baiting, hunting, hawking, and rowing barges—during church services (either the afternoon wasn’t as much of an issue, or they intended to take up the matter of the entire day at a later time). It was discussed for eight days over two weeks before passing and being sent to the Queen. That this Bill concerning the Sabbath, as hath been before observed, was long in passing the two Houses, and much debated betwixt them, being committed, and Amendments upon Amendments added unto it, which as appeareth in this place was the cause of some Disputation between the Lords and the said Commons. Source: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/jrnl-parliament-eliz1/pp321-331 Queen Elizabeth I vetoed the bill, in line with her policy of religious liberty for the Church of England. (Catholics were still on the Naughty List for decades to come.) And yet at last when it was agreed on by both the said Houses, it was dashed by her Majestyat the last day of this Parliament, upon that prejudicated and ill followed Principle (as may be conjectured) that she would suffer nothing to be altered in matter of Religion or Ecclesiastical Government.

Queen Elizabeth I vetoed the bill, in line with her policy of religious liberty for the Church of England. (Catholics were still on the Naughty List for decades to come.) And yet at last when it was agreed on by both the said Houses, it was dashed by her Majestyat the last day of this Parliament, upon that prejudicated and ill followed Principle (as may be conjectured) that she would suffer nothing to be altered in matter of Religion or Ecclesiastical Government.Puritan Nicholas Bownde wrote a scholarly book in 1595, True Doctrine of the Sabbath , urging Christians to sanctify the Sabbath as a day of meditation and spiritual exercises (very long morning and afternoon preaching services). These Sabbaths were meant to follow the Old Testament verses about keeping the Sabbath holy by not working or “doing their own pleasure” on that special day, as it was a moral imperative. They were to be solemn and sober, with no secular speech or acts. Queen Elizabeth and the Archbishop of Canterbury decreed that copies of the book be collected and burned in 1600 and 1601.

In 1601, the House of Commons passed a bill that only restricted markets and fairs on Sundays, but the House of Lords killed it. Queen Elizabeth died two years later, and King James I came to the throne. His authority was threatened by Puritans and other Calvinist dissenters (like the group who became the Pilgrims), whose influence was growing ever stronger and whose sermons and pronouncements conflicted with the King’s authority. One of his first acts was to commission a new version of the Bible which stressed the sovereignty of God and the hierarchy of worldly kings and princes, and the Authorized Version (or as many of us know it, the King James Version—KJV) was published in 1611.

However, those dissenters continued to agitate all over England. In 1617-18, the King went on a progress through the country, holding courts and meeting his subjects. One of the complaints he heard was that the usual work week being Monday through Saturday, from dawn to dusk, people needed time for recreation, markets, fun fairs, visiting family, and the like. People were required to attend services on Sunday morning, but needed the afternoon break. And the Puritans were stopping that by holding two long services on Sunday.

As answer to the problem of overwork and an unbalanced life—and that should he need soldiers for war that they’d be puny and weak—King James wrote The Book of Sports. In modern terms, it uses three pages of 12-point, single-space type, so it wasn’t large, but it was mighty! The book directed his subjects to go to church on Sunday morning and religious holidays as required, but to spend the afternoon enjoying life. He commanded that “no lawful recreation shall be barred to our good people,” and listed appropriate activities for those days: such as dancing, either men or women; archery for men, leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation, nor from having of May-games, Whitsun-ales, and Morris-dances; and the setting up of May-poles and other sports therewith used: so as the same be had in due and convenient time, without impediment or neglect of divine service: and that women shall have leave to carry rushes to the church for the decorating of it, according to their old custom; but withal we do here account still as prohibited all unlawful games to be used upon Sundays only, as bear and bull-baitings, interludes and at all times in the meaner sort of people by law prohibited, bowling.

As answer to the problem of overwork and an unbalanced life—and that should he need soldiers for war that they’d be puny and weak—King James wrote The Book of Sports. In modern terms, it uses three pages of 12-point, single-space type, so it wasn’t large, but it was mighty! The book directed his subjects to go to church on Sunday morning and religious holidays as required, but to spend the afternoon enjoying life. He commanded that “no lawful recreation shall be barred to our good people,” and listed appropriate activities for those days: such as dancing, either men or women; archery for men, leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation, nor from having of May-games, Whitsun-ales, and Morris-dances; and the setting up of May-poles and other sports therewith used: so as the same be had in due and convenient time, without impediment or neglect of divine service: and that women shall have leave to carry rushes to the church for the decorating of it, according to their old custom; but withal we do here account still as prohibited all unlawful games to be used upon Sundays only, as bear and bull-baitings, interludes and at all times in the meaner sort of people by law prohibited, bowling.Really? Bowling? That could be because one objective was to win the most points by knocking down the kingpin (was that seen as sedition?), or because of this: The Character of a Bowling-Alley and Bowling-Green A Bowling-Green, or Bowling-Ally is a place where three things are thrown away besides the Bowls, viz. Time, Money, and Curses, at the last ten for one. Source: http://www.greydragon.org/library/playingbowls.html

Catholics and non-conformists were barred from Sunday recreation because they didn’t attend approved Church of England services. Further, the King commanded that The Book of Sports be read in every church, and held the bishops, ministers, and churchwardens accountable that it should be done “by the book.”

King James died in 1625, and the book was reissued several times by his son, Charles I. Charles and the Parliament were at odds over authority and taxation, and the Scots and English churches were in conflict with their respective archbishops, Spottiswoode and Laud. In an attempt to control the Puritan (and other non-conformists) uprising, King Charles decreed that The Book of Sports be read again in all churches, and churches must conform to CofE’s Book of Common Prayer—which was also a hated book . If Puritan ministers would not conform, they were “silenced” (removed from the pulpit and not licensed to preach) and some were put in prison. And prison could be a death sentence. …the Bishop, and all other inferior churchmen and churchwardens, shall for their parts be careful and diligent, both to instruct the ignorant, and convince and reform them that are misled in religion, presenting them that will not conform themselves, but obstinately stand out, to our Judges and Justices: whom we likewise command to put the law in due execution against them.

However, there was a clause in Sports that many Puritan ministers latched onto. ...either constraining them to conform themselves or to leave the county.

Leave the country.

The thing is, the King didn't want them to leave the country because he would lose out on all that lovely tax base. If they sneaked out, they couldn’t go to Catholic France or Spain, and Lutheran (pretty close to Catholic!) Germany and Austria were at war with France, Italy, and Spain. Some, like the Pilgrims of Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, went to the Netherlands for ten years before they sailed to Plymouth. One of their leaders, their pastor John Robinson, is my ancestor 12 generations back. His treatise on the Sabbath, A Just and Necessary Apology, was published in 1625, the year he died.

For the vast majority of Puritans, though, there was no place to go but America, still under English rule, but a safe 3,000 miles by ocean journey away from the King and archbishops.

Some ministers escaped the long arm of the law by hiding with the help of sympathizers like the Earl of Lincoln—until the Earl was imprisoned. The senior pastor of the Boston St. Botolph’s, Rev. John Cotton, was one of the many ministers who had to hide before escaping to New England. Ten percent of the citizens of Boston, Lincolnshire, emigrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony with or shortly after John Cotton went there. (Cotton had been asked to come to Massachusetts several times, but declined until he was pushed out of England by fear of prison.)

William and Anne Marbury Hutchinson followed Rev. Cotton to Boston. William and Mary Dyer were married in the Anglican church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, but in 1635 were admitted to the Puritan membership in Boston’s First Church (and they were exiled from it in 1638).

Entire towns in Essex and many other counties emptied and sailed to the new Boston between 1630 and 1640. It’s estimated that about 35,000 people moved to New England during that decade. When the English Civil Wars began, with Puritans in ascendancy, thousands of the emigrants moved back to England. In May 1643, The Book of Sports was burned by angry Puritans in Cheapside.

People who had had such a threat of persecution and death were deeply convicted of the truth of their beliefs. They followed the Ten Commandments and other Old Testament laws to the letter, to prove to God that they were worthy of salvation. The fourth commandment, to keep the Sabbath holy, was one of the factors that caused their persecution in the first place. Obedience to God was worth moving across the world, or dying for.

Both on the ships, and in New England, they followed their stringent regulations about Sabbath-keeping. They had long preaching services twice on Sunday. The English church holidays like Christmas and Easter were prohibited, and people were expected to work as usual. During the Sabbath there was no alcohol consumption, no unseemly walking, no court or corporal punishment, no work that could be done another day (like laundry or beer brewing), no swimming, no buying or selling, no games or dances, no unnecessary travel, no hunting or fishing. The music or literature was sacred, never secular. Sabbath began at sundown on Saturday evening and ended during the night before Monday.

I had ancestors in the Salem, Massachusetts, area who emigrated there as Puritans, fleeing The Book of Sports style of Christianity. But at some point they converted to Baptist beliefs and risked beatings, fines, and imprisonment. They moved to New Jersey and formed a town and congregation there. They became Sabbatarians (seventh-day/Saturday was their holy day) in the 1710s and shared their Baptist minister with a first-day congregation. That branch stayed Seventh-day Baptist from then until the 20th century.

I had ancestors in the Salem, Massachusetts, area who emigrated there as Puritans, fleeing The Book of Sports style of Christianity. But at some point they converted to Baptist beliefs and risked beatings, fines, and imprisonment. They moved to New Jersey and formed a town and congregation there. They became Sabbatarians (seventh-day/Saturday was their holy day) in the 1710s and shared their Baptist minister with a first-day congregation. That branch stayed Seventh-day Baptist from then until the 20th century. Some people who are from or still in Sabbatarian denominations (Seventh-day Adventist, Seventh-day Baptist, Church of God, etc.) have experienced that list of prohibitions, and it doesn’t seem foreign at all. Some see that 17th-century culture and marvel at the legalism of the Puritans and their spiritual descendants. But perhaps we can look at that strength of character, that integrity, that obey-God-rather-than-men resolve, and admire them. We can remember that we carry the DNA of those godly pioneers in our bodies and that moral fiber in our culture.

All these people were still living by faith when they died. They did not receive the things promised; they only saw them and welcomed them from a distance, admitting that they were foreigners and strangers on earth. People who say such things show that they are looking for a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have had opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country—a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared a city for them. Hebrews 11:13-16 NIV.

Published on June 12, 2015 23:15

June 1, 2015

Mary Dyer's execution, 1 June 1660--book excerpt

It was no accident that Mary Dyer returned to Massachusetts against her death-penalty banishment--she didn't sneak back, she arrived on a specific date for the purpose of civil disobedience. She forced the theocratic government to execute her, a high-status, well-known woman innocent of anything but carrying out Jesus' commission in Matthew 25, in the hope that her death would be so shocking that the people would cry out to the government to cease their bloody persecution and allow liberty of conscience (what we call religious freedom and separation of church and state).

My extensive research, just for this short section, included books by Quaker historians, and the records of Massachusetts Bay Colony General Court, as well as the backgrounds of all the people involved, from Gov. Endecott to the militia (their formation and purpose), and the hangman.

Excerpt from Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This ,

copyright 2014, by Christy K Robinson.

All rights reserved. This book or blog article, or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

June 1, 1660Boston, Massachusetts As she had been last October, Mary was surrounded by a troop of more than a hundred musketeers and pikemen who were there to protect the officials of the court from the angry mob. Captain Oliver was the officer in charge of the guard today. Word had spread quickly overnight, and this day thousands of men, women, and children were spread out along the streets as if for a parade. Others waited at the gallows for the spectacle to come to them. Should she attempt to speak, before and behind her, military men beat the slow execution drum call to drown out the sound of her voice. Brrr-tap-tap-rest. Brrr-tap-tap-rest. Brrr-tap-tap-rest. Brrr-tap-tap-rest.The monotonous, repetitive beat set the pace for the walk along Tremont Road, part of the Common, and finally, to the fortification and gate of the city of Boston. Then they were out on the isthmus, or Boston Neck, where the road led to Roxbury. Hundreds more people surged up from the towns of Roxbury and Weymouth.Mary remembered that the last execution here had been a chilly autumn day, appropriate, perhaps, for the murder of the two dear young men. Today, though, was a day at the height of spring, with daisies on the Common turning their faces toward the sun, and dandelion seed puffs drifting on the breeze from the bay. It was just such a day, exactly twenty-two years ago, that the great earthquake had rumbled across New England, and the little group of people praying with Anne Hutchinson had felt the Pentecostal filling of the Holy Spirit.And thirty years ago this day, Mary remembered seeing the noon-day comet that marked the birth of the future King Charles the Second, and presaged war, famine, and plague. What was it that John Donne had preached at St. Paul’s? That “all mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; God's hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again, for that library where every book shall lie open to one another.”

Like all memories, these flashed through Mary’s mind in still pictures, like landscape paintings. One could view the scene all at once, or stop and decipher the symbolism. She had lived them and learned from them, but were they connected with today? She and the guard and drummers, and all of Boston behind them, arrived at the gallows. Michaelson ceremoniously handed the end of her tether to Edward Wanton, the man at the foot of the gallows. Mary climbed the ladder, the drumbeat ended, and she stood ready. The crowds of men and women, packed shoulder to shoulder on the slim neck of land, jostled one another and a few on the edges of the marsh actually trod in the mud. “Mistress Dyer,” a man shouted over the din of the people, “if you’d only leave this colony, you might come down and save your life!” As beautiful as this world is, and as much as I love my life with family, friends, health, and prosperity, what does it avail? How does it compare to the Paradise I’ve already glimpsed? If my momentary death can shine Light on the human right to worship and obey God, then let it be. I shall be with the Lord. She answered, projecting her voice while she motioned for silence, “No, I cannot, for in obedience to the will of the Lord I came, and in his will I abide faithful—to the death.” The man in charge of her execution was Captain John Evered-Webb. She recognized him from 1635, when he and his shipmates had been caught in the great hurricane as they approached Massachusetts, but miraculously avoided shipwreck and limped in with broken masts and mere rags of sails. He and his sister and her husband had settled near Salem, and that made Webb one of Endecott’s men. He stood on the platform and shouted to be heard. “The condemned woman has been here before, here on this very gallows. She had the sentence of banishment on pain of death, but she has come again now and broken the law. Therefore she is guilty of her own blood. The executioner shall not ask her forgiveness as would be customary.”The masked hangman bowed as if he were an actor.At this insult, some in the crowd grumbled at Webb’s lack of godly grace. The angry murmur spread through the crowd like a wave as the nearest told their neighbors behind them what they’d heard. Mary answered, looking pointedly at Reverend Wilson, Major-General Humphrey Atherton (an assistant to the governor), and others of her accusers, “No, I came to keep blood guiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjustlaw of banishment upon pain of death, made against the innocent servants of the Lord. Therefore my blood will be required at your hands, who willfully do it; but for those that do it in the simplicity of their hearts, I desire the Lord to forgive them.” She raised her voice to a victorious shout. “I came to do the will of my Father, and in obedience to his will, I stand even to death!”“’Tis wrong to murder this innocent woman! Take her down! Let her go home!” came the shouts from every direction.Edward Wanton tied Mary’s legs together with the rope over her skirts for modesty when she’d be dropped.John Wilson, the man who had examined Mary and William for church membership, and baptized her baby Samuel nearly a quarter-century before, put on a dramatic act for the audience, far larger than any Sunday congregation he’d ever preached to. He added a sob to his voice: “Mary Dyer, O repent! O repent! And be not so deluded, and carried away by the deceit of the devil.” It was difficult to control her facial expression at this hypocritical display of concern for her soul, but Mary answered, “No, man, I am not now to repent.” One of the ministers asked if she would have the elders pray for her soul, if she would not pray for herself. They meant an appointed elder of the First Church of Christ in Boston. She said, “I do not know of a single elder here.” She meant she didn’t recognize their elders as having authority over her. As Anne Hutchinson had rejected the authority of that body over her. “Would you have any of the people to pray for you?”“I desire the prayers of all the people of God.” As she looked over the crowd, she recognized Friends, including Robert and Deborah Harper of Sandwich. She knew they kept her in prayer continually, and being encouraged, she felt warmth and strength fill her. A scoffer from the church cried out, “It may be she thinks there is none here!”Mary replied softly, “I know that there are only a few here.” The Light became brighter now, Mary thought. She was closer to heaven than she’d ever been. Another from the crowd below her urged, “Woman, you’re about to die, and a heretic at that. Don’t throw away your soul. Ask for an elder to pray, that his effectual, fervent prayer will be heard by God.” Mary answered, “No, first a child, then a young man, then a strong man, before an ‘elder’ in your Church of Christ.” “What?” called the critic. “You said ‘an elder in Christ Jesus?’ You don’t want a Christian man to pray for you? If not an elder in Christ Jesus, you prefer to go, then, with your master the Devil?” She said, “It is false, it is false; I never spoke those words. I said an elder in the church.”“Are you not afraid to die, knowing that you are a cursed Quaker? A heretic?” said the minister Norton. “The Lord has said to me, as to all who come to him in repentance and humility, ‘Today shalt thou be with me in Paradise.’” “You and the dead Quakers said last time that you havebeen in Paradise.”“Yes, I have been in Paradise several days,” she said with a blissful smile. John Wilson, who had a look of fear on his face now, produced a handkerchief from his coat, and young Wanton draped it over Mary’s face and tucked it under the rope before than hangman made it snug. She remembered what Sir Harry Vane had said, “Death does not bring us into darkness, but takes darkness out of us, us out of darkness, and puts us into marvelous light.” As she spoke further of the eternal happiness into which she was now to enter, Mary felt that familiar buoyancy of light and love, as if she were being borne away by angels. “Mary.”“Yes, Lord?”

***** Read everything that led up to this moment, and what transpired afterward, in Mary Dyer Illuminated and Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This, both by Christy K Robinson.

As I wrote in the foreword to both volumes on Mary Dyer and her husband William, they weren't written to be religious books for a religious market. But I did want to show that though religion in that generation was everything to them (they'd staked their lives, families and possessions on a New Jerusalem in the New World), the colony of Rhode Island, of which William Dyer was an important government member, incorporated itself as a secular democracy, with religion distinctly separate from government matters. Their founding documents influenced and inspired generations to come, and formed a template for the Constitution's Bill of Rights.

Published on June 01, 2015 00:08

May 21, 2015

Timeline of Mary Dyer’s last month

The not-very-merry month of May

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

As I was researching and writing the two novels on Mary and William Dyer (originally, I planned one book about Mary, but when I included her “other half,” I had to separate the manuscripts), I found conflicting accounts among histories that were mostly written by Quakers. They told the story for the purposes of proselytizing, for justifying the actions of their fellow believers, and some wrote short pieces as eyewitnesses, but they told Mary’s part of the story from one perspective.

As I was researching and writing the two novels on Mary and William Dyer (originally, I planned one book about Mary, but when I included her “other half,” I had to separate the manuscripts), I found conflicting accounts among histories that were mostly written by Quakers. They told the story for the purposes of proselytizing, for justifying the actions of their fellow believers, and some wrote short pieces as eyewitnesses, but they told Mary’s part of the story from one perspective. Today, we have the benefits of archived materials in both Old and New England, journals and correspondence that have been scanned and transcribed for the Gutenberg Project, satellite maps, geological surveys, online art collections, and we can analyze events with more logic and science than the historians of past centuries. We can fit Mary’s and William’s puzzle pieces into the greater picture.

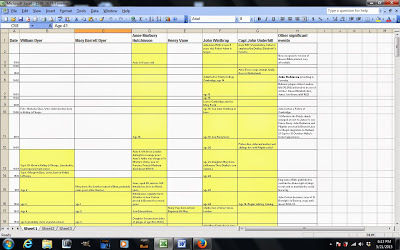

A small portion of my timeline for the Dyer books.

A small portion of my timeline for the Dyer books.© Christy K RobinsonTo clear up the conflicts in their reporting, and insert actual events and lives the Dyers interacted with, I made an Excel grid from the 1580s when Gov. John Winthrop and Anne Hutchinson were born, to 1709, when the Dyers’ youngest child died. I could figure when women were pregnant and how long sea voyages took, how many times and how long Mary Dyer was in prison (and who she was with), and where people were when earthquakes and comets and epidemics occurred. It answered many questions, and inspired story lines.

When it came to the 1650s, though, the Anglo-Dutch War broke out and Cromwell’s Protectorate ruled the British Empire, and Quaker missionaries arrived in America, the facts were terribly garbled, so I broke the 10 years into months. It helped me unravel the conflicting reports, especially about Mary’s two dates with the gallows, and to realize that there were no coincidences. The events like the Hutchinsonians making the Exodus from Boston in 1638, and Mary’s final return to Boston in 1660, were deliberate and well considered.

In May, all across New England, colonial elections were held, and courts and assemblies heard cases like incorporating towns, funding roads and bridges, and criminal cases like dealing with Quakers and Baptists, thieves, alcoholics, and adulterers. During this month, freemen (voters and jurymen) came from all over the colony to stay in town and do their civic duty, attend church services, and do trading and exports.

William Dyer was at colonial assembly in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, in late May 1660. Boston was full of thousands of people at the same time, when the annual elections returned John Endecott for another year’s term as governor. That’s precisely why Mary Dyer chose May 21 to arrive in Boston: for the greater audience to witness her civil disobedience and be forced to deal with the issues. It wasn’t a random date, it was a time when the Governor, deputy governors, magistrates, freemen, leading citizens and candidates—would all be in one place. If she were to be executed, she wanted everyone to know it and see it.

Not quite two years before, two Quaker men had had their ears cut off in private, and they were immediately shipped back to England. Their disobedience had a smaller effect on the Boston populace. Katherine Scott, who would become the mother-in-law of one of those men, protested that secret punishment, noting that it was against English law to punish in private (because punishment was meant to deter further crime in the community), and Endecott and the deputies were in violation of the law. For being impudent to the governors, Mrs. Scott was stripped to the waist and they gave her 10 lashes with the tri-corded whip before they imprisoned her for a while.

May 1660, Julian calendar Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1

From late November 1659 to May 11, 1660, Mary was staying at the northeast end of Long Island, on a smaller island called Shelter Island.

May 10-11: Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick, 62-year-olds who had been severely persecuted for Quaker beliefs and practices, died in exile on Shelter Island, where Mary Dyer had spent the winter. It’s a small island, half land and half marsh, so Mary and the Southwicks would have been in each others’ company at the Sylvester house during the extremely harsh winter. In my book, Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This, I speculated that she saw their failing health and stayed until their deaths. Her sorrow and outrage may have helped propel her return to Boston.

Approx. May 12: Mary took a ship from Shelter Island to Providence, Rhode Island. It would have taken 12-24 hours in the best of weather, so estimate a May 13-14 arrival in Providence. Mary attended a Quaker Meeting in Providence, and took young Patience Scott (daughter of Katherine Marbury Scott) with her on the 44-mile walk to Boston. It probably took three days to walk that distance, and sleep and eat in the forest, so they may have set out on May 17-18.

Saturday, May 20: “In the night there was a continuation of thunder and lightning, from 9 to 3 o’clock.” (Annals of Salem). The book only recorded remarkable events, not your everyday weather report, so this storm was severe and noticeable, and probably part of a system that included other parts of Massachusetts. There may even have been tornadoes.

Sunday, May 21: Mary arrested for returning to Massachusetts Bay Colony against her banishment order. Her arrival was timed for Sunday/First Day, when church attendance swelled the numbers of people in town. She was jailed for 10 days. (One historian wrote that Mary was free, ministering and preaching between the 21st and her arraignment on the 31st. My timeline containing all the accounts corrected that.)

Saturday, May 27: William Dyer was engaged with Assembly meetings in Portsmouth, RI, we learn from his letter of May 27. Someone needed two to three days to bring him the news that Mary was in Boston jail, meaning that she was incarcerated almost immediately on her arrival in town. And William’s letter needed 1-3 days to arrive at Boston’s General Court, even with a fast messenger.

Wednesday, May 31: Mary Dyer arraigned at General Court, and sentenced to death based on her October 1659 trial. See related article, 1660 warrant to bring Mary Dyer to trial.

Thursday, June 1: Thursday was Lecture Day in Massachusetts Bay Colony, with required church attendance. It was also the day when punishments and executions were carried out, because people were supposed to see the wages of wickedness and turn away from sin, and then go to church to hear a sermon tied to the events of the day. Mary Dyer was executed on Boston Neck at 9:00am, after which the 2,000 to 5,000 spectators went to church.

Christy K Robinson

is author of two biographical novels on William and Mary Dyer, and a collection of her nonfiction research on the Dyers. In 1660, Mary Dyer was hanged for her civil disobedience over religious freedom, and her husband’s and friends’ efforts in that human right became a model for the United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights 130 years later. The books (and Kindle versions) are available on Amazon. CLICK HERE for the links.

Christy K Robinson

is author of two biographical novels on William and Mary Dyer, and a collection of her nonfiction research on the Dyers. In 1660, Mary Dyer was hanged for her civil disobedience over religious freedom, and her husband’s and friends’ efforts in that human right became a model for the United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights 130 years later. The books (and Kindle versions) are available on Amazon. CLICK HERE for the links.And if you'd like to own or give an art-quality print of Mary Dyer's handwriting, her letter to the General Court of Massachusetts, CLICK HERE.

Published on May 21, 2015 18:34

April 22, 2015

17th-century Spirits

If you’re a fuddle-cup or swill-belly, you just might SEE spirits!

Join me in welcoming author Margaret Porter to William-and-Mary-Dyer-World. From time to time, I run articles on the 17th-century English culture that was so familiar to the Dyers and their associates, Anne Hutchinson, John Winthrop, Henry Vane, Roger Williams, John Clarke, and so many others. Margaret Porter has recently released a book that begins in 1684, the last of the reign of King Charles II, and the beginning of the reign of James II, the former Duke of York. To put this time in perspective with the Dyers, this was the adulthood of their children. Their son William Dyer was mayor of New York and a customs official, and is mentioned in the “Diary of Samuel Pepys” as assisting James, Duke of York, in investigating a scam on Long Island.

© 2015 Margaret Evans Porter

An English public house much like the

An English public house much like the

Dyers would have known.For centuries, Britain’s main beverages were ale and beer—at all times of day—brewed at home or locally, in households and in the monasteries. For ale, the necessary ingredients were water, ground malt, and yeast, mixed together and left to ferment. From the fifteenth century, influenced by Continental methods, hops were added to create beer. Small ale or small beer, watered versions of the fully-brewed sort, were consumed with breakfast and given to children. There were other variations: buttered beer, derived by brewing eggs and butter, and the unpalatable-sounding cock-ale. If interested in making the latter, here are instructions:

Take eight gallons of Ale; take a Cock and boil him well; then take four pounds of raisins…two or three nutmegs…three or four flakes of mace…half a pound of dates…beat these all up in a mortar, and put to them two quarts of the best Sack; and when the Ale hath done working, put these in and stop it close six or seven days, and then bottle it, and after a month you may drink it.

Sack was a wine obtained from Spain or the Canary islands. Sherry, its fortified cousin, is the Anglicized term for Jerez (in Andalusia) where it originated, and at the start of the 17th century it became popular in England. French wines—from Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, and other regions—were traded by Dutch merchants, although in wartime such goods might be obtained via smugglers. This was equally true of brandy, sometimes referred to as Nantz or Nantes, the area where it was produced. Bristol-made vesselsThe Gaelic peoples of Ireland and Scotland had long been distilling their “water of life” (uisce beatha) from malt, which by the 17th century was Anglicized to usquebaughand eventually to whisk(e)y. At that time there was no aging process, and the liquor was extremely potent and unrefined.

Bristol-made vesselsThe Gaelic peoples of Ireland and Scotland had long been distilling their “water of life” (uisce beatha) from malt, which by the 17th century was Anglicized to usquebaughand eventually to whisk(e)y. At that time there was no aging process, and the liquor was extremely potent and unrefined.

During the 17th century, rum began to be produced in Barbados and other sugarcane islands of the Caribbean, where molasses was fermented, distilled, and exported to England. The first rum distillery in the American Colonies started in New York in the 1660s, and rum-making soon became New England’s most notable industry. The British Royal Navy had initially provided French brandy as part of a sailor’s ration, but in the mid-17th century rum replaced it.

As well as delivering French wine and spirits to Britain, the Netherlands’ most significant contribution was gin—genever, or Hollands—made from juniper berries (often with turpentine as an additive), originating in the 16thcentury. Military men drank it when serving in the Low Countries, and Prince William of Orange’s accession to his deposed father-in-law’s throne resulted in its wider availability in Britain. Unlike ale, beer, and wine, it was unlicensed and not taxed, and therefore was the cheapest of spirits—prior to the Gin Act of 1736. Gin consumption was blamed for widespread public drunkenness, crime, and degradation of the populace.

Whether in city or countryside, taverns and alehouses were hubs of social activity, a place to meet, eat, smoke tobacco, sing, dance, converse, debate, fight, and receive messages. Female publicans—married or widowed—were not uncommon; they also managed breweries. A rich man's spirits flask

A rich man's spirits flask

Women were also skilled in making wines and spirits and cordials for medicinal or household use, from readily available plants. They distilled wine from cowslips, dandelions, parsnips, birch, and elder-blossom. Using berries plucked from hedgerow blackthorn bushes, they made sloe gin. Cider from apples and perry from pears were widely available in regions where orchards prevailed, especially Somerset, Devon, Dorset, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, and Herefordshire.

Wine and spirits were ingredients in many other drinks. Arrack or rack punch was composed of a specific sort of East Indian brandy, double-distilled in Goa, combined with sugar syrup, citrus, cinnamon and other spices, and boiling water. Syllabubs were whipped using wine or cider, fresh cream, and spices. Possets often included sack, with or without milk or cream, ale, eggs and spices. Wassail was a combination of dark sugar, hot beer, sherry, cold beer, and toasted bread, often with a roasted apple added at the last. The beverage known as Bishop involved piercing an orange with cloves and roasting it, then adding it to a saucepan of heated port wine. The steaming liquid was then poured over lemon rind to steep, served warm with grated nutmeg.

Alcoholic beverages were transported and stored in wooden hogsheads and casks of various sizes, and decanted to ceramic jars or bottles, the latter mostly manufactured in Bristol. Drinking vessels could be tankards of leather or wood or pewter, silver goblets or blown glass stemware which might be etched with a coat of arms or a device indicating political loyalties.

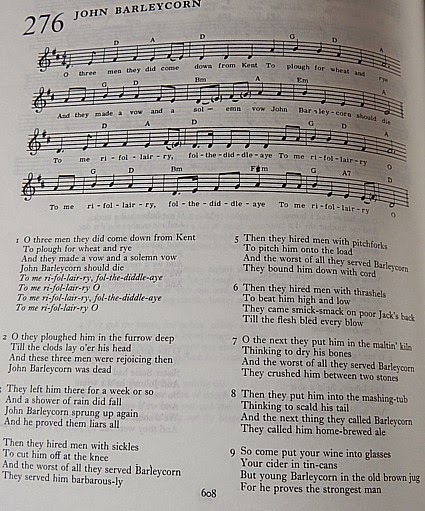

One of the best-known drinking songs is probably “John Barleycorn,” hundreds of years old:

Then they put him in the mashing-tub,Thinking to scald his tale,And the next thing they called Barleycorn,They called him home-brewed ale.

Here’s the verse of another 17th century drinking song:

Be merry, good hearts, and call for your quarts,and let not the liquor be lacking,We have gold in store, we purpose to roar,until we can set care a-packing.Mine Hostess make haste, and let no time waste,every man shall have his due,To save shoes and your trouble, bring the pots doublefor he that made one, makes two.

Seventeenth Century Drinking Vocabulary

Bawdy-house bottle—very small in sizeBingo—brandyBlackjack—leathern drinking jug The Drunkard's Cloak.

The Drunkard's Cloak.

Related article:

Alcoholism and the Drunkard’s Cloak

in this Dyer blog.Bowse—DrinkBowsy (Boozy)—DrunkBristol milk—sherryBumper—full glassCut—drunk; deep cut—very drunkFuddle-cup—drunkardHalf-seas over—almost drunkHot pot—ale and brandy boiled togetherMaul’d—swingingly drunkMaudlin—weepingly drunkMellow—almost drunkMuddled—half drunkNazy-nabs—drunken coxcombsNipperkin—half a pint of wine, half a quarter of brandyNoggin—quarter pint of brandyPot-valiant—drunkRomer—a drinking glassRot-gut—small or thin beerStingo—strong liquorStitch—very strong aleSwill-belly—a great drinkerTall boy—a pottle or 2-quart pot of wineTears of the tankard—drops of the liquor that fall besideTipsy—almost drunkTope—to drink; old toper—staunch drunkardTop-heavy—drunkVent—bung-hole in a vessel_________________________

MARGARET PORTER

is an award-winning, bestselling novelist whose lifelong study of British history inspires her fiction and her travels. A PLEDGE OF BETTER TIMES, set in England’s late 17th century royal court,

MARGARET PORTER

is an award-winning, bestselling novelist whose lifelong study of British history inspires her fiction and her travels. A PLEDGE OF BETTER TIMES, set in England’s late 17th century royal court,

Margaret’s book, A Pledge of Better Times, is reviewed on another of Christy’s blogs HERE .

Join me in welcoming author Margaret Porter to William-and-Mary-Dyer-World. From time to time, I run articles on the 17th-century English culture that was so familiar to the Dyers and their associates, Anne Hutchinson, John Winthrop, Henry Vane, Roger Williams, John Clarke, and so many others. Margaret Porter has recently released a book that begins in 1684, the last of the reign of King Charles II, and the beginning of the reign of James II, the former Duke of York. To put this time in perspective with the Dyers, this was the adulthood of their children. Their son William Dyer was mayor of New York and a customs official, and is mentioned in the “Diary of Samuel Pepys” as assisting James, Duke of York, in investigating a scam on Long Island.

© 2015 Margaret Evans Porter

An English public house much like the

An English public house much like the Dyers would have known.For centuries, Britain’s main beverages were ale and beer—at all times of day—brewed at home or locally, in households and in the monasteries. For ale, the necessary ingredients were water, ground malt, and yeast, mixed together and left to ferment. From the fifteenth century, influenced by Continental methods, hops were added to create beer. Small ale or small beer, watered versions of the fully-brewed sort, were consumed with breakfast and given to children. There were other variations: buttered beer, derived by brewing eggs and butter, and the unpalatable-sounding cock-ale. If interested in making the latter, here are instructions:

Take eight gallons of Ale; take a Cock and boil him well; then take four pounds of raisins…two or three nutmegs…three or four flakes of mace…half a pound of dates…beat these all up in a mortar, and put to them two quarts of the best Sack; and when the Ale hath done working, put these in and stop it close six or seven days, and then bottle it, and after a month you may drink it.

Sack was a wine obtained from Spain or the Canary islands. Sherry, its fortified cousin, is the Anglicized term for Jerez (in Andalusia) where it originated, and at the start of the 17th century it became popular in England. French wines—from Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, and other regions—were traded by Dutch merchants, although in wartime such goods might be obtained via smugglers. This was equally true of brandy, sometimes referred to as Nantz or Nantes, the area where it was produced.

Bristol-made vesselsThe Gaelic peoples of Ireland and Scotland had long been distilling their “water of life” (uisce beatha) from malt, which by the 17th century was Anglicized to usquebaughand eventually to whisk(e)y. At that time there was no aging process, and the liquor was extremely potent and unrefined.

Bristol-made vesselsThe Gaelic peoples of Ireland and Scotland had long been distilling their “water of life” (uisce beatha) from malt, which by the 17th century was Anglicized to usquebaughand eventually to whisk(e)y. At that time there was no aging process, and the liquor was extremely potent and unrefined.During the 17th century, rum began to be produced in Barbados and other sugarcane islands of the Caribbean, where molasses was fermented, distilled, and exported to England. The first rum distillery in the American Colonies started in New York in the 1660s, and rum-making soon became New England’s most notable industry. The British Royal Navy had initially provided French brandy as part of a sailor’s ration, but in the mid-17th century rum replaced it.

As well as delivering French wine and spirits to Britain, the Netherlands’ most significant contribution was gin—genever, or Hollands—made from juniper berries (often with turpentine as an additive), originating in the 16thcentury. Military men drank it when serving in the Low Countries, and Prince William of Orange’s accession to his deposed father-in-law’s throne resulted in its wider availability in Britain. Unlike ale, beer, and wine, it was unlicensed and not taxed, and therefore was the cheapest of spirits—prior to the Gin Act of 1736. Gin consumption was blamed for widespread public drunkenness, crime, and degradation of the populace.

Whether in city or countryside, taverns and alehouses were hubs of social activity, a place to meet, eat, smoke tobacco, sing, dance, converse, debate, fight, and receive messages. Female publicans—married or widowed—were not uncommon; they also managed breweries.

A rich man's spirits flask

A rich man's spirits flaskWomen were also skilled in making wines and spirits and cordials for medicinal or household use, from readily available plants. They distilled wine from cowslips, dandelions, parsnips, birch, and elder-blossom. Using berries plucked from hedgerow blackthorn bushes, they made sloe gin. Cider from apples and perry from pears were widely available in regions where orchards prevailed, especially Somerset, Devon, Dorset, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, and Herefordshire.

Wine and spirits were ingredients in many other drinks. Arrack or rack punch was composed of a specific sort of East Indian brandy, double-distilled in Goa, combined with sugar syrup, citrus, cinnamon and other spices, and boiling water. Syllabubs were whipped using wine or cider, fresh cream, and spices. Possets often included sack, with or without milk or cream, ale, eggs and spices. Wassail was a combination of dark sugar, hot beer, sherry, cold beer, and toasted bread, often with a roasted apple added at the last. The beverage known as Bishop involved piercing an orange with cloves and roasting it, then adding it to a saucepan of heated port wine. The steaming liquid was then poured over lemon rind to steep, served warm with grated nutmeg.

Alcoholic beverages were transported and stored in wooden hogsheads and casks of various sizes, and decanted to ceramic jars or bottles, the latter mostly manufactured in Bristol. Drinking vessels could be tankards of leather or wood or pewter, silver goblets or blown glass stemware which might be etched with a coat of arms or a device indicating political loyalties.

One of the best-known drinking songs is probably “John Barleycorn,” hundreds of years old:

Then they put him in the mashing-tub,Thinking to scald his tale,And the next thing they called Barleycorn,They called him home-brewed ale.

Here’s the verse of another 17th century drinking song:

Be merry, good hearts, and call for your quarts,and let not the liquor be lacking,We have gold in store, we purpose to roar,until we can set care a-packing.Mine Hostess make haste, and let no time waste,every man shall have his due,To save shoes and your trouble, bring the pots doublefor he that made one, makes two.

Seventeenth Century Drinking Vocabulary

Bawdy-house bottle—very small in sizeBingo—brandyBlackjack—leathern drinking jug

The Drunkard's Cloak.

The Drunkard's Cloak.Related article:

Alcoholism and the Drunkard’s Cloak

in this Dyer blog.Bowse—DrinkBowsy (Boozy)—DrunkBristol milk—sherryBumper—full glassCut—drunk; deep cut—very drunkFuddle-cup—drunkardHalf-seas over—almost drunkHot pot—ale and brandy boiled togetherMaul’d—swingingly drunkMaudlin—weepingly drunkMellow—almost drunkMuddled—half drunkNazy-nabs—drunken coxcombsNipperkin—half a pint of wine, half a quarter of brandyNoggin—quarter pint of brandyPot-valiant—drunkRomer—a drinking glassRot-gut—small or thin beerStingo—strong liquorStitch—very strong aleSwill-belly—a great drinkerTall boy—a pottle or 2-quart pot of wineTears of the tankard—drops of the liquor that fall besideTipsy—almost drunkTope—to drink; old toper—staunch drunkardTop-heavy—drunkVent—bung-hole in a vessel_________________________

MARGARET PORTER

is an award-winning, bestselling novelist whose lifelong study of British history inspires her fiction and her travels. A PLEDGE OF BETTER TIMES, set in England’s late 17th century royal court,

MARGARET PORTER

is an award-winning, bestselling novelist whose lifelong study of British history inspires her fiction and her travels. A PLEDGE OF BETTER TIMES, set in England’s late 17th century royal court,Margaret’s book, A Pledge of Better Times, is reviewed on another of Christy’s blogs HERE .

Published on April 22, 2015 14:59

March 30, 2015

The Passover Exodus from Massachusetts

Anne Hutchinson's secret theology

Anne Hutchinson statue at the Massachusetts Statehouse.© 2015 Christy K Robinson

Anne Hutchinson statue at the Massachusetts Statehouse.© 2015 Christy K Robinson

Anne Marbury Hutchinson, at her second trial before the Massachusetts Bay Colony theocratic government, was excommunicated from the Puritan First Church of Boston, on 22 March 1638*. She left her six-month house arrest, heresy conviction, and excommunication behind as she stalked out of Boston with the Passover.