Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 10

November 18, 2015

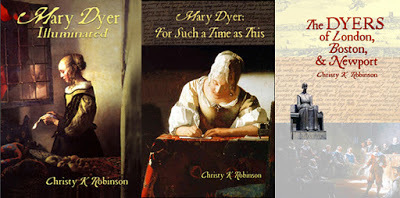

Thanksgiving week DISCOUNTS on books by Christy K Robinson

Plan now for your holiday shopping--here are the books and dates when they'll be discounted on Amazon.com in the United States. The dates don't match up exactly because Amazon's calendars have a mind of their own! So mark your calendar or set a notification for your mobile phone, because this is the best deal I'm allowed to make for you.

Plan now for your holiday shopping--here are the books and dates when they'll be discounted on Amazon.com in the United States. The dates don't match up exactly because Amazon's calendars have a mind of their own! So mark your calendar or set a notification for your mobile phone, because this is the best deal I'm allowed to make for you. If you already own the paperbacks or Kindle editions, remember your family members: parents, siblings, your favorite cousins... All four titles (five, if you count the out-of-print devotional book!) by Christy Robinson have five-star reviews, so you know you're giving a quality gift.

You can quickly open the Amazon sales page from the hyperlinks below. Checkout is extremely secure and easy: I've been an Amazon customer since 1997 and have never had a security issue with them.

The Kindle editions have every word and image that the paperback books do, but most readers (and I) prefer to read history on paper because you can return to sections or review the resources and images in the front and back of the text. And paperbacks are keepers that you can leave out on the sofa table or loan to your family, while Kindle is more limited. In any case, you have the choice!

Of course, a paperback is easy to send directly to your recipient, gift-wrapped, but did you know that you can give a Kindle e-book as a gift? Amazon offers that option. Your recipient needs to have either a Kindle device, or the free Kindle app on their tablet or computer.

Kindle editions are found at Amazon's site. Click the book titles to go to the book's sales page.

Mary Dyer Illuminated (Vol. 1)Nov. 24 $7.99 regular priceNov. 25-26 $4.99 38% offNov. 27-28 $5.99 26% offNov. 29 $6.99 13% offDec. 1 $7.99 regular price

Mary Dyer: For Such aTime as This (Vol. 2)Nov. 19 $7.99 regular priceNov. 20 $4.99 38% offNov. 21-22 $5.99 26% offNov. 23-24 $6.99 13% offNov. 25 $7.99 regular price (Amazon Kindle wouldn’t allow me to use the same dates for this one as the other Dyer books.)

The DYERS of London, Boston, & Newport (Vol. 3) Nov. 24 $6.99 regular priceNov. 25-26 $3.99 43% offNov. 27-28 $4.99 29% offNov. 29 $5.99 15% offDec. 1 $6.99 regular price

Paperback books are also on sale between these dates. Note that these books are discounted at Amazon's subsidiary, CreateSpace, NOT at Amazon's regular site. Click the book title to go to its sale page on CreateSpace. Use the discount code, which is unique to each book title.

Mary Dyer Illuminated (Vol. 1) Regular price $19.99Nov. 25-30 $15.00 25% offPaperback book only, not available in e-book

Use 25% Discount code N52GM43B at CreateSpace link. Dec. 1 $19.99

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (Vol. 2)Regular price $19.99Nov. 25-30 $15.00 25% off

Use 25% Discount code BFJMT9AG at CreateSpace link.Dec. 1 $19.99

The DYERS of London, Boston, & Newport (Vol. 3) Regular price $12.00 This is already the minimum price I’m allowed to set, so no discount can be made.

Effigy Hunter (Medieval history/travel/genealogy/not Dyers)by Christy K Robinson

Regular price $14.00Nov. 25-30 $10.50 25% off

Use 25% Discount code: TAPDAVEQ

at CreateSpace link.Dec. 1 $14.00

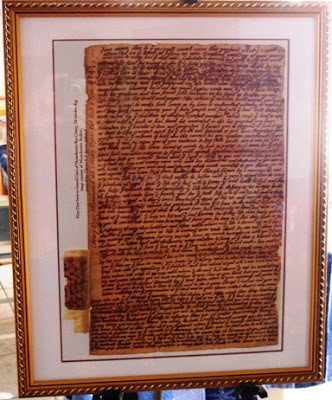

Another gift idea is buying reproduction letters

Another gift idea is buying reproduction lettersin the handwriting of Mary Barrett Dyer

and her husband William Dyer.

Click the tab above this article,

or click this link to open a new page:

http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/p/mary-dyer-1659-letter.html

Published on November 18, 2015 21:36

Early-colonial thanksgiving customs and foods

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

Have you wondered how your early American ancestors celebrated Thanksgiving customs, and what foods they feasted upon? Check out these articles and books for some vivid details! (Click the colored links to read the articles.)

How the English colonists celebrated thanksgiving Thanksgiving in Massachusetts Bay Colony bit.ly/R2Kt14

Thanksgiving in New England--no parties or football bit.ly/1iPehJa

Heart-stopping meals of colonial New England: Recipes you can try

bit.ly/skQaJT

How To Make 17th-Century Delights: Whipp'd Syllabub (a frothy cocktail)

http://www.theawl.com/2012/07/17th-century-delights-whippd-syllabub

************** For a first-hand description of thanksgiving days held in Boston and Salem in the 1630s and 1640s, read it in Mary Dyer Illuminated, by Christy K Robinson. It's Volume I of the two-part story of William and Mary Dyer. The Dyers series , which has won almost unanimous five-star reviews, is available in paperback and Kindle at online booksellers like Amazon. B e sure to order the series for yourself, and as gifts for friends and family members. http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

This article shortened URL: bit.ly/1X8QWDy

Have you wondered how your early American ancestors celebrated Thanksgiving customs, and what foods they feasted upon? Check out these articles and books for some vivid details! (Click the colored links to read the articles.)

How the English colonists celebrated thanksgiving Thanksgiving in Massachusetts Bay Colony bit.ly/R2Kt14

Thanksgiving in New England--no parties or football bit.ly/1iPehJa

Heart-stopping meals of colonial New England: Recipes you can try

bit.ly/skQaJT

How To Make 17th-Century Delights: Whipp'd Syllabub (a frothy cocktail)

http://www.theawl.com/2012/07/17th-century-delights-whippd-syllabub

************** For a first-hand description of thanksgiving days held in Boston and Salem in the 1630s and 1640s, read it in Mary Dyer Illuminated, by Christy K Robinson. It's Volume I of the two-part story of William and Mary Dyer. The Dyers series , which has won almost unanimous five-star reviews, is available in paperback and Kindle at online booksellers like Amazon. B e sure to order the series for yourself, and as gifts for friends and family members.

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

This article shortened URL: bit.ly/1X8QWDy

Published on November 18, 2015 15:53

October 27, 2015

27 October--big day for William and Mary Dyer

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

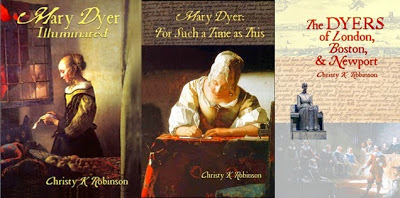

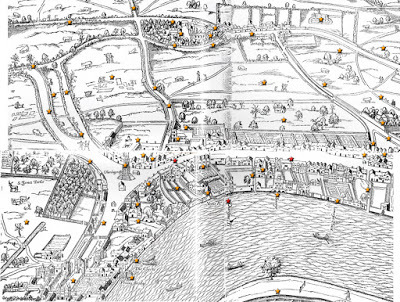

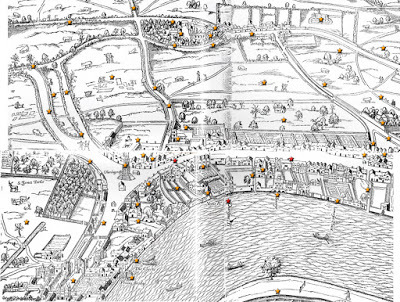

1605 map of the parish of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, showing

1605 map of the parish of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, showing

the church as the Dyers would have known it

in the 1620s and 1630s. The church is in the top-left

quadrant, near the center of the map.

Do you know the three major events that occurred in the lives of William and Mary Dyer on October 27?

They were married at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church in the borough of Westminster, near London, on October 27, 1633.

They buried their newborn, first-born son, William, at the same church on Oct. 27, 1634.

Mary was taken to the gallows on Boston Neck, outside the city gate, to participate in the hanging of Marmaduke Stevenson and William Robinson, on Oct. 27, 1659. She stood with a noose around her neck until the last moment, thinking she'd be hanged and would enter God's presence. Her reprieve had been arranged nine days earlier, according to court records, but the "honor" of bringing the news of the reprieve was given to her fourth child, then a teenager, William Dyer. He would later receive the royal appointment of customs inspector for New York, and then mayor of New York.

Christy K Robinson is the author of

Christy K Robinson is the author of

three 5-star books on the Dyers.

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

1605 map of the parish of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, showing

1605 map of the parish of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, showingthe church as the Dyers would have known it

in the 1620s and 1630s. The church is in the top-left

quadrant, near the center of the map.

Do you know the three major events that occurred in the lives of William and Mary Dyer on October 27?

They were married at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church in the borough of Westminster, near London, on October 27, 1633.

They buried their newborn, first-born son, William, at the same church on Oct. 27, 1634.

Mary was taken to the gallows on Boston Neck, outside the city gate, to participate in the hanging of Marmaduke Stevenson and William Robinson, on Oct. 27, 1659. She stood with a noose around her neck until the last moment, thinking she'd be hanged and would enter God's presence. Her reprieve had been arranged nine days earlier, according to court records, but the "honor" of bringing the news of the reprieve was given to her fourth child, then a teenager, William Dyer. He would later receive the royal appointment of customs inspector for New York, and then mayor of New York.

Christy K Robinson is the author of

Christy K Robinson is the author of three 5-star books on the Dyers.

http://bit.ly/RobinsonAuthor

Published on October 27, 2015 15:52

October 22, 2015

Boston’s prison during the Dyer years

Mary Dyer kept in a Cobhole, said her husband

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

The English and colonial American judicial and penal systems of four centuries ago were much different from ours. In our modern system, we often (incorrectly) use “prison” and “jail” interchangeably, but there is a distinction. A jail is meant for short-term detention between arrest and court conviction, or for terms of a year or less, and it’s run by a local authority such as a city or county. A prison is meant for long-term incarceration of convicted felons, and is administered by a state or federal authority. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=qa&iid=322

Back in Merry Olde England, the American settlers had experienced, or known of, harsh prison conditions. Incarceration for theft or assault could become a death penalty because of rampant disease and infection, cholera and tuberculosis, exposure to extreme cold, starvation, and injury. Prison terms were generally short because if a prisoner was guilty, he or she would be hanged, put to labor to pay off a debt, pressed onto a ship’s crew, or transported elsewhere. If they were acquitted, of course, they were released.

The Puritans of Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth Colonies remembered that their ministers, and their relatives and neighbors, had been jailed and died there for rebelling against the Church of England. It was not their intention to throw offenders into prison and forget them. They believed their punishments would be merciful, for the instruction, example, and purification of their flock.

1743 map of Boston, showing location of its prison that stood

1743 map of Boston, showing location of its prison that stood

on the spot from 1635, for almost 200 years.In New England, courts inflicted physical punishment for fornication or adultery, drunkenness, theft of food or property, servants assaulting masters, rape, swearing, and other crimes. Blasphemy, reviling a member of the court, or slandering could get your tongue stuck in a forked stick for several hours, and possibly a whipping. An alcoholic would be made to wear a “D” (for drunkard) on his chest. A bondservant’s theft of food from his master was a serious crime because food was rationed in the winter and spring—that could get 10 stripes on his bare back. Assault could mean whipping and time in the stocks. While adultery could be a capital crime, the courts usually showed mercy at the last moment by whippings and fines. Boston, March 7, 1637Thomas Pettet for suspition of slaunder, idlenes, & stubbornenes, is censuredto bee severely whiped, & to bee kept in hould.William James being presented for incontinency, knowing his wife before Marriage[the baby must have been born in under 9 months], was sentenced to bee set in the bilboes at Boston, the 5th, in the afternoone, & in the stocks at Salem upon the next Courte day, & bound in 20£

Boston, Sept. 1637Mr John Greene, of New Providence, was fined 20£, & commited untill he Jn Green the fine of 20£ bee payd, & enjoined not to come into this jurisdiction vpon paine of fine or imprisonment, at the pleasure of the Courte, for speaking contemptuously of the magistrates.

Some crimes, notably those of conscience, religious practice, or dissent with the government, were punished with banishment, including putting the offender on an outbound ship at their own considerable expense, and shipped back to England.

More serious crimes that theocratic courts believed couldn’t be repented of and apologized for, like murder, buggery of animals, or homosexuality, were punished with hanging. Women who were accused of being witches (they weren’t, of course) were stripped and examined for “witches marks” like skin tags and moles, and if they were convicted, they were hanged.

There are several colonial court actions regarding the Boston prison: Sept. 1635: ordered, that Mr Brenton shall finishe, att the publ charge, all that is necessary to be done att the prison att Boston./3 March 1636: All offenders which shalbe in the prison att Boston att the tyme of any Court there holden, shalbe tryed att that Court, except in the war’t of his commitment hee be reserved to the greate Quarter Court. [Yet, Mary Dyer was imprisoned in late March 1657, when she arrived in Boston after five years in England, and they held court and even elections, without bringing her to trial. She had to get a letter out to William Dyer to come rescue her.] 2 June 1641: The Governor & 2 other magistrates have power to agree with the marshal & Gov & the keeper or the prison./7 Oct. 1641: It is ordered, the prison should be made warme & safe./

A 17th-century prison door in Warwick, UK.Boston’s prison on Prison Lane, later called Queen Street, had “outer walls ... of stone three feet thick, its unglazed windows barred with iron, the cells partitioned off with plank, the doors covered with iron spikes, the passage-ways like the dark valley of the shadow of death.” https://archive.org/stream/annalsofkingscha01foot/annalsofkingscha01foot_djvu.txt(page 86)

A 17th-century prison door in Warwick, UK.Boston’s prison on Prison Lane, later called Queen Street, had “outer walls ... of stone three feet thick, its unglazed windows barred with iron, the cells partitioned off with plank, the doors covered with iron spikes, the passage-ways like the dark valley of the shadow of death.” https://archive.org/stream/annalsofkingscha01foot/annalsofkingscha01foot_djvu.txt(page 86)

In the 1630s and 1640s, prison or jail terms weren’t meant to be life terms, or particularly long incarcerations. They were a way to punish misdemeanor offenses by forced labor, or holding prisoners between court sessions and immediately after corporal punishment like flogging, branding, or ear removals. But with the dawn of the 1650s, under Gov. John Endecott and Richard Bellingham, punishments became more harsh and prolonged, and prisoners were held without trial.

There are anecdotes about English prisons that mention fleas and lice, rats that bit or fed on bodies, and rampant disease and infection. It seems reasonable to expect similar conditions in Salem, Plymouth, and Boston.

Some of the notable cases I found that involved prison time were these: Sept. 1636: Edward Woodley, for attempting a rape, swearing, & breaking into a house, was censured to be severely whiped 30 stripes, a yeares imprisonment, & kept to hard labor, with course dyot [coarse diet], & to weare a coller of yron./ Mrs Hutchinson, (the wife of Mr William Hutchinson,) being convented for traduceing the ministers & their ministery in this country, shee declared volentarily her revelations for her ground, & that shee should bee delivred & the Court ruined, with their posterity, & therevpon was banished, & the meane while was comited to Mr Joseph Weld untill the Court shall dispose of her. [Anne Marbury Hutchinson was sentenced to house arrest in custody of Joseph Welde because she was married to a very high-status man who was wealthy, a magistrate, and a merchant who was a friend of many ministers and members of the government and church.]In the 1650s and 1660s, Quakers were thrown in prison for possessing Quaker literature, for refusing to take the loyalty oath (which meant they weren’t serving on juries or voting in the assemblies), refusing to attend Congregational/Puritan church services and pay tithes, meeting with other Quakers for religious service, not showing proper etiquette to members of the court or government, or for entering Boston Harbor on a ship. Their incarcerations were accompanied by whippings that at first were upon entry to prison, but then became weekly or twice-weekly. Furthermore, those short stays intended in the 1630s under Gov. Winthrop became terms of 10 months or more under Gov. John Endecott. A shilling illegally minted in Boston

A shilling illegally minted in Boston

because there were precious few coins

in New England with which to do business.

They were ALL minted with the 1652 date to

be able to claim innocence and necessity

during the English Civil Wars chaos. Only

the English mint was supposed to create currency,

so Gov. Endecott and others were actually

counterfeiters. By the 1650s, the courts were holding prisoners for months at a time, without trying them. At times, there were more than 20 Quakers in the Boston prison, in addition to criminals. Prisons charged 13-30 shillings a month for food and "lodging," in addition to hard labor, to each prisoner, so it was a lucrative business. Even if the charges were dropped or the prisoner acquitted, the lodging fee was still required upon release. The courts had already fined offenders or seized property, and the “room and board” was in addition to fines. But that fee didn’t always include food, and that’s why some members of the community, whether Congregational or Quaker, visited their friends and family with supplies. Samuel Shattuck was a Quaker who brought food to imprisoned Quakers, and that’s probably what Mary Dyer was doing when she was arrested for visiting Quakers at the Boston prison. There may have been the aspects of encouragement or carrying messages, but providing medical care for those who had been whipped, clothing and coats and blankets against the intense cold, and daily food would have been essential to survival for the Friends who were imprisoned—as Mary knew firsthand. In 1658, Katherine Marbury Scott knew that private corporal punishments were against the law, because executions and whippings were meant as a warning to the public not to err. She publicly protested the wrongdoing of Gov. Endecott and his deputies on two points: that they were cruelly torturing the Quakers, and that they were going about it against their own laws. Her protest, made worse because a woman was accusing men, resulted in her being cast into the prison for a month, as well as being publicly exposed, nude to her waist, and whipped 10 stripes with the triple knots, which was a common punishment for lawbreakers. In 1663, an African servant, Zipporah, was arrested and imprisoned for fornication and murder a few days after miscarrying a seven-months fetus. A Boston attorney asked the court to release her from her just imprisonment “that she may not lye where she is to perrish.” There was a danger that she could die in prison even though she wasn’t convicted of a crime. It’s unclear if Zipporah was released at that time, or if she had to stay in prison through the fall and winter, until her charges were dropped in the spring. She married and was widowed, and lived until at least 1705. In August 1659, William Dyer, a former Rhode Island attorney general who had represented numerous cases in Boston, wrote to the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, asking that his wife Mary be released from prison. The letter described how Mary was soaking wet (probably from rain), and thrust into a bare, cold room with an earth floor, which was worse treatment than they’d give to a domestic animal in their care, and that she’d been kept solitary and not let outside for fresh air or exercise.

Having received some letters from my wife, I am given to understand of her commitment to close prison to a place (according to description) not unlike Bishop Bonner's [Catholic torturer] rooms ... It is a sad condition, in executing such cruelties towards their fellow creatures and sufferers ... Had you no commiseration of a tender soul that being wett to the skin, you cause her to thrust into a room whereon was nothing to sitt or lye down upon but dust ... had your dogg been wett you would have offered it the liberty of a chimney corner to dry itself, or had your hoggs been pend in a sty, you would have offered them some dry straw, or else you would have wanted mercy to your beast, but alas Christians now with you are used worse [than] hoggs or doggs ... oh merciless cruelties. …My wife writes me word and information, she had been above a fortnight and had not trode on the ground, but saw it out your window; what inhumanity is this, had you never wives of your own, or ever any tender affection to a woman, deal so with a woman, what has nature forgotten if refreshment be debarred?

He continued, saying that when a Quaker was arrested merely for visiting prisoners (as William himself had done without molestation), and “answer be not made according to the ruling will; away with them to the Cobhole or new Prison, or House of Correction…”

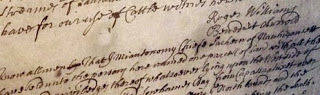

Silver cobsI’d never seen the word “cobhole” until I read William’s letter. So I looked it up, and there was absolutely nothing. I found that the English word for the Spanish silver coin or cabo, was “cob.” Coins were difficult to come by in New England, and cobs were much-clipped lumps of silver that were used as currency. So a cobhole was probably sarcastic slang for a money pit—a lucrative extortion racket where they threw away money for “services” a prisoner didn’t receive.

Silver cobsI’d never seen the word “cobhole” until I read William’s letter. So I looked it up, and there was absolutely nothing. I found that the English word for the Spanish silver coin or cabo, was “cob.” Coins were difficult to come by in New England, and cobs were much-clipped lumps of silver that were used as currency. So a cobhole was probably sarcastic slang for a money pit—a lucrative extortion racket where they threw away money for “services” a prisoner didn’t receive.

Mary Dyer was imprisoned at Boston in the spring of 1657, twice in the late summer and early fall of 1659 (her first date with the gallows), and from May 21-June 1, 1660, when she was hanged. According to Plymouth Colony records, Thomas Greenfield, a man who had brought her to Sandwich from Newport in violation of the “No Quakers Allowed in Our Colony” law had to pay 11 shillings for her November 1659 imprisonment in Plymouth, as well as 15 shillings for her boat passage away from there, probably to Shelter Island. If we compare a monthly rate of some other prisoners, eleven shillings represented about a week or 10 days of prison fees.

Many Quakers, men and women, were stripped to the waist and whipped 10 stripes upon entry to prison. Women like Katherine Scott were whipped for speaking out against men, pointing out that the court violated their own laws. And it seems (to me) that female Quaker preachers were whipped more for the "abomination" of being women preachers than for their beliefs or actions. I’ve found no evidence that Mary Dyer was whipped. If she was not, perhaps it’s because she didn’t do public speaking (there’s no report or evidence of her words being recorded), or because she was a high-status woman with a powerful husband.

Mary Dyer was acquainted with the horrors of prison, both in the experience of her friends, and of her own. She still chose to endure the persecution to make a statement to the theocratic court that their torture and hangings must stop.

See also Grandparents-in-Law, the Quaker Connection for a letter sent from Quaker prisoners being held in the Boston prison for many months without trial.

*************************************** More great anecdotes about mid-17th century England and New England, supported by research, can be found in the nonfiction paperback and ebook The DYERS of London, Boston, & Newport, by Christy K Robinson. It's the third in a series about Mary Dyer, Anne Hutchinson, Sir Henry Vane, Roger Williams, and John Winthrop.

More great anecdotes about mid-17th century England and New England, supported by research, can be found in the nonfiction paperback and ebook The DYERS of London, Boston, & Newport, by Christy K Robinson. It's the third in a series about Mary Dyer, Anne Hutchinson, Sir Henry Vane, Roger Williams, and John Winthrop.

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

The English and colonial American judicial and penal systems of four centuries ago were much different from ours. In our modern system, we often (incorrectly) use “prison” and “jail” interchangeably, but there is a distinction. A jail is meant for short-term detention between arrest and court conviction, or for terms of a year or less, and it’s run by a local authority such as a city or county. A prison is meant for long-term incarceration of convicted felons, and is administered by a state or federal authority. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=qa&iid=322

Back in Merry Olde England, the American settlers had experienced, or known of, harsh prison conditions. Incarceration for theft or assault could become a death penalty because of rampant disease and infection, cholera and tuberculosis, exposure to extreme cold, starvation, and injury. Prison terms were generally short because if a prisoner was guilty, he or she would be hanged, put to labor to pay off a debt, pressed onto a ship’s crew, or transported elsewhere. If they were acquitted, of course, they were released.

The Puritans of Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth Colonies remembered that their ministers, and their relatives and neighbors, had been jailed and died there for rebelling against the Church of England. It was not their intention to throw offenders into prison and forget them. They believed their punishments would be merciful, for the instruction, example, and purification of their flock.

1743 map of Boston, showing location of its prison that stood

1743 map of Boston, showing location of its prison that stoodon the spot from 1635, for almost 200 years.In New England, courts inflicted physical punishment for fornication or adultery, drunkenness, theft of food or property, servants assaulting masters, rape, swearing, and other crimes. Blasphemy, reviling a member of the court, or slandering could get your tongue stuck in a forked stick for several hours, and possibly a whipping. An alcoholic would be made to wear a “D” (for drunkard) on his chest. A bondservant’s theft of food from his master was a serious crime because food was rationed in the winter and spring—that could get 10 stripes on his bare back. Assault could mean whipping and time in the stocks. While adultery could be a capital crime, the courts usually showed mercy at the last moment by whippings and fines. Boston, March 7, 1637Thomas Pettet for suspition of slaunder, idlenes, & stubbornenes, is censuredto bee severely whiped, & to bee kept in hould.William James being presented for incontinency, knowing his wife before Marriage[the baby must have been born in under 9 months], was sentenced to bee set in the bilboes at Boston, the 5th, in the afternoone, & in the stocks at Salem upon the next Courte day, & bound in 20£

Boston, Sept. 1637Mr John Greene, of New Providence, was fined 20£, & commited untill he Jn Green the fine of 20£ bee payd, & enjoined not to come into this jurisdiction vpon paine of fine or imprisonment, at the pleasure of the Courte, for speaking contemptuously of the magistrates.

Some crimes, notably those of conscience, religious practice, or dissent with the government, were punished with banishment, including putting the offender on an outbound ship at their own considerable expense, and shipped back to England.

More serious crimes that theocratic courts believed couldn’t be repented of and apologized for, like murder, buggery of animals, or homosexuality, were punished with hanging. Women who were accused of being witches (they weren’t, of course) were stripped and examined for “witches marks” like skin tags and moles, and if they were convicted, they were hanged.

There are several colonial court actions regarding the Boston prison: Sept. 1635: ordered, that Mr Brenton shall finishe, att the publ charge, all that is necessary to be done att the prison att Boston./3 March 1636: All offenders which shalbe in the prison att Boston att the tyme of any Court there holden, shalbe tryed att that Court, except in the war’t of his commitment hee be reserved to the greate Quarter Court. [Yet, Mary Dyer was imprisoned in late March 1657, when she arrived in Boston after five years in England, and they held court and even elections, without bringing her to trial. She had to get a letter out to William Dyer to come rescue her.] 2 June 1641: The Governor & 2 other magistrates have power to agree with the marshal & Gov & the keeper or the prison./7 Oct. 1641: It is ordered, the prison should be made warme & safe./

A 17th-century prison door in Warwick, UK.Boston’s prison on Prison Lane, later called Queen Street, had “outer walls ... of stone three feet thick, its unglazed windows barred with iron, the cells partitioned off with plank, the doors covered with iron spikes, the passage-ways like the dark valley of the shadow of death.” https://archive.org/stream/annalsofkingscha01foot/annalsofkingscha01foot_djvu.txt(page 86)

A 17th-century prison door in Warwick, UK.Boston’s prison on Prison Lane, later called Queen Street, had “outer walls ... of stone three feet thick, its unglazed windows barred with iron, the cells partitioned off with plank, the doors covered with iron spikes, the passage-ways like the dark valley of the shadow of death.” https://archive.org/stream/annalsofkingscha01foot/annalsofkingscha01foot_djvu.txt(page 86)In the 1630s and 1640s, prison or jail terms weren’t meant to be life terms, or particularly long incarcerations. They were a way to punish misdemeanor offenses by forced labor, or holding prisoners between court sessions and immediately after corporal punishment like flogging, branding, or ear removals. But with the dawn of the 1650s, under Gov. John Endecott and Richard Bellingham, punishments became more harsh and prolonged, and prisoners were held without trial.

There are anecdotes about English prisons that mention fleas and lice, rats that bit or fed on bodies, and rampant disease and infection. It seems reasonable to expect similar conditions in Salem, Plymouth, and Boston.

Some of the notable cases I found that involved prison time were these: Sept. 1636: Edward Woodley, for attempting a rape, swearing, & breaking into a house, was censured to be severely whiped 30 stripes, a yeares imprisonment, & kept to hard labor, with course dyot [coarse diet], & to weare a coller of yron./ Mrs Hutchinson, (the wife of Mr William Hutchinson,) being convented for traduceing the ministers & their ministery in this country, shee declared volentarily her revelations for her ground, & that shee should bee delivred & the Court ruined, with their posterity, & therevpon was banished, & the meane while was comited to Mr Joseph Weld untill the Court shall dispose of her. [Anne Marbury Hutchinson was sentenced to house arrest in custody of Joseph Welde because she was married to a very high-status man who was wealthy, a magistrate, and a merchant who was a friend of many ministers and members of the government and church.]In the 1650s and 1660s, Quakers were thrown in prison for possessing Quaker literature, for refusing to take the loyalty oath (which meant they weren’t serving on juries or voting in the assemblies), refusing to attend Congregational/Puritan church services and pay tithes, meeting with other Quakers for religious service, not showing proper etiquette to members of the court or government, or for entering Boston Harbor on a ship. Their incarcerations were accompanied by whippings that at first were upon entry to prison, but then became weekly or twice-weekly. Furthermore, those short stays intended in the 1630s under Gov. Winthrop became terms of 10 months or more under Gov. John Endecott.

A shilling illegally minted in Boston

A shilling illegally minted in Boston because there were precious few coins

in New England with which to do business.

They were ALL minted with the 1652 date to

be able to claim innocence and necessity

during the English Civil Wars chaos. Only

the English mint was supposed to create currency,

so Gov. Endecott and others were actually

counterfeiters. By the 1650s, the courts were holding prisoners for months at a time, without trying them. At times, there were more than 20 Quakers in the Boston prison, in addition to criminals. Prisons charged 13-30 shillings a month for food and "lodging," in addition to hard labor, to each prisoner, so it was a lucrative business. Even if the charges were dropped or the prisoner acquitted, the lodging fee was still required upon release. The courts had already fined offenders or seized property, and the “room and board” was in addition to fines. But that fee didn’t always include food, and that’s why some members of the community, whether Congregational or Quaker, visited their friends and family with supplies. Samuel Shattuck was a Quaker who brought food to imprisoned Quakers, and that’s probably what Mary Dyer was doing when she was arrested for visiting Quakers at the Boston prison. There may have been the aspects of encouragement or carrying messages, but providing medical care for those who had been whipped, clothing and coats and blankets against the intense cold, and daily food would have been essential to survival for the Friends who were imprisoned—as Mary knew firsthand. In 1658, Katherine Marbury Scott knew that private corporal punishments were against the law, because executions and whippings were meant as a warning to the public not to err. She publicly protested the wrongdoing of Gov. Endecott and his deputies on two points: that they were cruelly torturing the Quakers, and that they were going about it against their own laws. Her protest, made worse because a woman was accusing men, resulted in her being cast into the prison for a month, as well as being publicly exposed, nude to her waist, and whipped 10 stripes with the triple knots, which was a common punishment for lawbreakers. In 1663, an African servant, Zipporah, was arrested and imprisoned for fornication and murder a few days after miscarrying a seven-months fetus. A Boston attorney asked the court to release her from her just imprisonment “that she may not lye where she is to perrish.” There was a danger that she could die in prison even though she wasn’t convicted of a crime. It’s unclear if Zipporah was released at that time, or if she had to stay in prison through the fall and winter, until her charges were dropped in the spring. She married and was widowed, and lived until at least 1705. In August 1659, William Dyer, a former Rhode Island attorney general who had represented numerous cases in Boston, wrote to the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, asking that his wife Mary be released from prison. The letter described how Mary was soaking wet (probably from rain), and thrust into a bare, cold room with an earth floor, which was worse treatment than they’d give to a domestic animal in their care, and that she’d been kept solitary and not let outside for fresh air or exercise.

Having received some letters from my wife, I am given to understand of her commitment to close prison to a place (according to description) not unlike Bishop Bonner's [Catholic torturer] rooms ... It is a sad condition, in executing such cruelties towards their fellow creatures and sufferers ... Had you no commiseration of a tender soul that being wett to the skin, you cause her to thrust into a room whereon was nothing to sitt or lye down upon but dust ... had your dogg been wett you would have offered it the liberty of a chimney corner to dry itself, or had your hoggs been pend in a sty, you would have offered them some dry straw, or else you would have wanted mercy to your beast, but alas Christians now with you are used worse [than] hoggs or doggs ... oh merciless cruelties. …My wife writes me word and information, she had been above a fortnight and had not trode on the ground, but saw it out your window; what inhumanity is this, had you never wives of your own, or ever any tender affection to a woman, deal so with a woman, what has nature forgotten if refreshment be debarred?

He continued, saying that when a Quaker was arrested merely for visiting prisoners (as William himself had done without molestation), and “answer be not made according to the ruling will; away with them to the Cobhole or new Prison, or House of Correction…”

Silver cobsI’d never seen the word “cobhole” until I read William’s letter. So I looked it up, and there was absolutely nothing. I found that the English word for the Spanish silver coin or cabo, was “cob.” Coins were difficult to come by in New England, and cobs were much-clipped lumps of silver that were used as currency. So a cobhole was probably sarcastic slang for a money pit—a lucrative extortion racket where they threw away money for “services” a prisoner didn’t receive.

Silver cobsI’d never seen the word “cobhole” until I read William’s letter. So I looked it up, and there was absolutely nothing. I found that the English word for the Spanish silver coin or cabo, was “cob.” Coins were difficult to come by in New England, and cobs were much-clipped lumps of silver that were used as currency. So a cobhole was probably sarcastic slang for a money pit—a lucrative extortion racket where they threw away money for “services” a prisoner didn’t receive. Mary Dyer was imprisoned at Boston in the spring of 1657, twice in the late summer and early fall of 1659 (her first date with the gallows), and from May 21-June 1, 1660, when she was hanged. According to Plymouth Colony records, Thomas Greenfield, a man who had brought her to Sandwich from Newport in violation of the “No Quakers Allowed in Our Colony” law had to pay 11 shillings for her November 1659 imprisonment in Plymouth, as well as 15 shillings for her boat passage away from there, probably to Shelter Island. If we compare a monthly rate of some other prisoners, eleven shillings represented about a week or 10 days of prison fees.

Many Quakers, men and women, were stripped to the waist and whipped 10 stripes upon entry to prison. Women like Katherine Scott were whipped for speaking out against men, pointing out that the court violated their own laws. And it seems (to me) that female Quaker preachers were whipped more for the "abomination" of being women preachers than for their beliefs or actions. I’ve found no evidence that Mary Dyer was whipped. If she was not, perhaps it’s because she didn’t do public speaking (there’s no report or evidence of her words being recorded), or because she was a high-status woman with a powerful husband.

Mary Dyer was acquainted with the horrors of prison, both in the experience of her friends, and of her own. She still chose to endure the persecution to make a statement to the theocratic court that their torture and hangings must stop.

See also Grandparents-in-Law, the Quaker Connection for a letter sent from Quaker prisoners being held in the Boston prison for many months without trial.

***************************************

More great anecdotes about mid-17th century England and New England, supported by research, can be found in the nonfiction paperback and ebook The DYERS of London, Boston, & Newport, by Christy K Robinson. It's the third in a series about Mary Dyer, Anne Hutchinson, Sir Henry Vane, Roger Williams, and John Winthrop.

More great anecdotes about mid-17th century England and New England, supported by research, can be found in the nonfiction paperback and ebook The DYERS of London, Boston, & Newport, by Christy K Robinson. It's the third in a series about Mary Dyer, Anne Hutchinson, Sir Henry Vane, Roger Williams, and John Winthrop.

Published on October 22, 2015 02:47

September 30, 2015

Free-born daughter of Boston slaves goes to jail

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

Annibale Carracci, attrib.,

Annibale Carracci, attrib., Portrait of an African Slave Woman, ca. 1580s.

(fragment of a larger painting). Wikimedia.Zipporah, a free African servant in Boston, was the daughter of Grace and Richard Done, slaves of Boston's richest man, Robert Keayne.

As a young woman, and servant (by choice, not bond) of Richard Parker, Zipporah had lain with an African bondservant named Jeffere at the beginning of March 1663, and appeared to be pregnant in early September, at which time two African women told Parker's housekeeper that Zipporah must report her fornication and pregnancy and name the father, so she could claim child support. One of the women who counseled Zipporah was Elizabeth or Bess, the freed African bondservant of Abigail and Edward Hutchinson, eldest son of Anne Marbury Hutchinson.

Zipporah declared that she was only fat, not pregnant, since she had "ye custom of women upon her" (a regular menstrual cycle). But three weeks later, she went into a quick labor and miscarried a seven-months’ fetus on Sept. 23, 1663. Her mistress, Mrs. Parker, pinned the fetus in a “ragge” and told Zipporah to bury it in a field the next day, but the young mother instead buried it in a tidal marsh with sandy mud, from which the infant's body washed away, never to be found.

Upon learning of the miscarriage and burial, authorities ordered an inquiry. Searchers never found her dark-skinned, black-haired fetus, but they did find the headless body of a larger, fully-formed, fairer-skinned newborn not far away.

She was charged with murder of the lighter-skinned child, but the jury of inquest would not say the body was her child because it didn't match the description of the miscarried fetus that the white women had seen born to Zipporah.

You are to take into yor costody Zippoer a negro woman for comittinge fornication wth Jeffere a negro man and haveing a bastard it was in a seccret way buryed by the sd Zippoer as shee confesseth but the child where she saith it was buryed is not yet foundDat 1-8-1663 [1 October 1663] To the keep of the Prisonin Boston Ri. Bellingham Dept Govr

To the honord County Courte now sitting at BostonThe humble petition of Zipporah a negro woman priso'rhumble beseecheth this Courte to take her and her miserable Conditioninto yor pious Consideration, for that she hath most justly deservedgods displeasure and yors for her sinn in being so wicked as to committthat sinn of fornication with that Jeffere the negro man, and is therforejustly imprisoned, but in reguard he is bound to appeare before thisCourte, to answer it, and she not bound over, to appeare anywhere doetherfore humbly beseech this honored Court, to call her before you,and to deal with her, as to yor wisedomes and mercy shall see meet,that she may not lye where she is to perrishAnd yor pour petticionr and prisoner shall dayly prayWO the mark of Zippora

It's unclear if Zipporah stayed in Boston prison over the winter. A grand jury refused to indict her and the case was dropped March 1, 1664. Zipporah may have had the first case of habeus corpus in America.

Whose baby was the one found murdered and buried about 10 days later? Was that baby also illegitimate, or did its mother kill it? Was that baby the product of Judge Parker’s son Jonathan assaulting an African slave? (Jonathan Parker fled to England after his alleged assaults.) Why was the murdered baby beheaded--was it to mask the identity of the mother or father, or because it was biracial, or was it a "monster" with birth defects, like Mary Dyer's third pregnancy?

The second generation of New England colonists, now coming to maturity in the 1650s and 1660s, were no angels. Governor John Endecott’s son Zerubbabel assaulted an Englishbondservant ten years earlier, and Zerubbabel went to England for a medical apprenticeship. The girl was flogged 30 stripes after giving birth and naming Zerubbabel as the father, but she was given the remainder of her bond time, she was married off to a fellow servant, and they disappeared from records.

Who was the man who composed Zipporah’s request for release from prison? Could it have been Elizabeth's former master, attorney Edward Hutchinson? Or Richard Parker, on whose land the missing fetus was supposed to have been buried (whose grandchild the headless baby may have been)?

You can read the original research on the case at this link: Did Interracial Sex in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Lead to THE CASE OF THE HEADLESS BABY: DID INTERRACIAL SEX IN THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY COLONY LEAD TO INFANTICIDE AND THE EARLIEST HABEAS CORPUS PETITION IN AMERICA?A 2009 paper by Melinde Lutz Sanborn, Program Director, Boston University, Center for Professional Education. Life election as one of the fifty Fellows of the American Society of Genealogists, selected for the quality and quantity of published work, 1993. Donald Lines Jacobus Award winner. Vice-President of ASG. Co-editor of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, a peer-reviewed scholarly journal. This paper was presented at a workshop at Hofstra University School of Law on November 2, 2009.

Published on September 30, 2015 18:15

August 31, 2015

Happy anniversary to us!

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

© 2015 Christy K Robinson Today is the fourth anniversary of going live with this William and Mary Barrett Dyer research blog in 2011. I’d been writing articles for a year before that, so I’d have material with which to make a splash. My desire is to share with you not only the extraordinary people the Dyers and their friends and enemies were, but give you a new take on what their motivations might have been in light of 21st-century research.

A snapshot today shows that this blog has passed 167,000 page views, and visitors are clicking in from 148 countries, including United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Germany, France, Brazil, Netherlands, India, Ireland, and Italy.

Of the 131 posts published, the top stories are:Top 10 Things You May Not Know About Mary Dyer 11,064 viewsMary Dyer’s “monster” 7,777 viewsI’ve found numerous articles copied and pasted into other people’s ancestry blogs and in newsletters as diverse as an astronomy site in southern England. Though I’m a little bit flattered that readers liked them, this is not cool . Flattery does not pay my bills. It’s a violation of my copyright. I did the research and the writing and polishing, and I haven’t been paid by anyone or any publisher. If I advertise my books and letter reproductions in the blogs, it’s a small way of recouping my expenditures. But my products are not being copied along with the purloined articles. If you borrow or steal my copy instead of linking to MY web pages, you’re doing me no favors. Some articles were graciously written by guest authors, and I’ve noted that in every copyright byline and the author tag at the end of the post, along with links to theirsites or products. Please respect our rights and ask permission. Simply asking to use the articles will probably result in pleasant chat and a “yes.”

Sparking juice, wine, or

Sparking juice, wine, orwhatever you like--

CHEERS!

A hearty thank-you to everyone who has shared these posts in social media, commented, or “followed” this blog. You've become friends, and we've discovered distant cousin relationships between this blog and Facebook pages. That's a fantastic side effect I never anticipated.

Published on August 31, 2015 19:32

August 25, 2015

The Dyers’ 1635 voyage from England to New England

and the Great August Hurricane of New England

© 2015 by Christy K Robinson

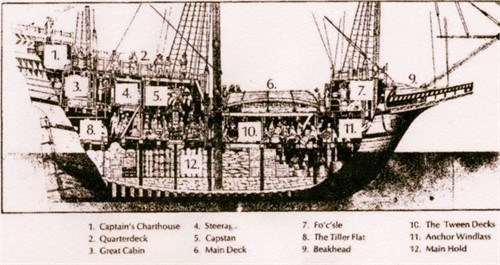

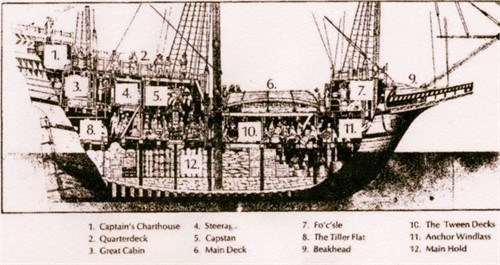

A ship of the time, in 1638: William Rainsborough’s

A ship of the time, in 1638: William Rainsborough’s

warship, Sovereign of the Sea, was used in the wars

of the Barbary Coast. Rainsborough, a contemporary

of Gov. John Winthrop, was the father of Winthrop’s

fourth wife, Martha, and of Judith, who married

Stephen Winthrop. Autumn 1635—Three hundred eighty years ago, William and Mary Dyer boarded an English ship with their Westminster neighbor, Henry Vane the Younger, and perhaps 100 others, and sailed to new Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony. No one knows the name of the ship or the exact date they arrived, but it probably arrived in October before one of the terrible winters of the Little Ice Age. Ship passages took an average of eight weeks if the winds were favorable, and up to twelve weeks if not.

The strongest hurricane ever to come ashore in New England made landfall in mid-August 1635, between Connecticut and Cape Cod, with massive 20-foot storm surges and winds that knocked down thousands of trees. Modern meteorologists estimate sustained winds of 135mph, from the descriptions of damages. Depending on which calendar historians used, Julian (old style) or Gregorian (new style, which we use now), the date for the hurricane is as early as August 13 or as late as August 26. Either way, the damage to shorelines and forest was still visible for many years.

Some historians have said that the eye of the storm passed between Boston and Plymouth. Native Americans in Narragansett Bay climbed high into trees to keep from being swept away by the waves. Gov. William Bradford of Plymouth Colony wrote, “Diverce vessels were lost at sea, and many more were in extreme danger… It caused ye sea to swell about 20 foote, right up & downe, and made many of the Indeans to clime into trees for their safetie.”

The 400-ton Great Hope, a ship full of passengers and their possessions, was just sailing into Massachusetts Bay when the gale struck them. They were driven aground near Charlestown, but when the wind shifted, they were blown back out on the Bay, and with the storm surge, pushed back aground at Charlestown. Those people survived, but a small pinnace broke up at Marblehead, and two families were washed away. On the pinnace, only Mr. and Mrs. Thacher survived, injured, but they lost all their children and goods.

Imagine leaving your home country, and being in sight of the shore of the Promised Land--and losing your entire family.

An English passenger ship, James, full of new immigrants (including my ancestors Hannah and John Ayers), nearly foundered as they came south along the New England coast, making for Boston. Rev. Increase Mather wrote, "At this moment,... their lives were given up for lost; but then, in an instant of time, God turned the wind about, which carried them from the rocks of death before their eyes. ...her sails rent in sunder, and split in pieces, as if they had been rotten ragges..."

Wikipedia: They tried to stand down during the storm just outside the Isles of Shoals, but lost all three anchors, as no canvas or rope would hold, but on Aug 13, 1635, torn to pieces, and not one death, all one hundred plus passengers of the James managed to make it to Boston Harbor.

There would have been search and rescue parties looking for survivors up and down the coast and small islands. I haven't found records of salvage operations, but the colonists were fully aware of their rights to salvage wreckage and possessions lost in shipwrecks.

August 1635 was about the time when the ship carrying the Dyers and Henry Vane would have left England to arrive by October, so it’s unlikely that they’d have been affected by that particular hurricane, unless the storm rode the Gulf Stream and they caught it in the North Atlantic. Even if they weren't caught in a tropical storm or hurricane themselves, they probably experienced high waves and winds from distant storms. There was always a high risk of violent storms.

Some of my research indicated that Puritans leaving England at that time had to swear loyalty to the King (the Dyers were royalists, so no problem there) and pay a large tax (or bribe) to be permitted to leave the country, so there’s speculation that some emigrants sneaked out on trading ships by way of Barbados and the Caribbean, and then up to Boston, which might be why not every emigrant shows up in passenger lists.

Ships rarely traveled alone. For armed protection from pirates, and to share resources (like physician or midwife), or if another ship needed repairs, they traveled in convoy. The ships carried not only the colonists and their many children, but their servants, the materials and tools the colonists needed to build homes, some livestock, seeds, furnishings, enough food for 18 months, clothing, guns and powder, and goods they couldn’t get or make in the wilderness of the New World. Privacy might have consisted of sheets hung from ropes. I’ve not seen a description of hygiene, but imagine that some passengers were seasick, others had diarrhea, there was animal waste, and children in nappies. Probably pregnant women and gassy men whose diet consisted of legumes and salted fish or meat. Although they could wash themselves with basins and towels, there weren't tubs or showers.

For John Winthrop's account of his fleet's 1630 arrival in New England, see http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2014/06/winthrop-fleet-fights-its-way-to-new.html

The Memoir of Captain Roger Clapp said that on board the ships, there were two sermons every day of the 70 days they were upon the deep. From the other paragraphs of his memoir, Capt. Clapp (my uncle about 14 generations back), describes this intensely religious sequestering as joyful and grace-filled, nothing like we’d consider with dread. He wrote of the frights and starvation of landing in Dorchester and trying to survive the polar vortexes of the Massachusetts winter, but Capt. Clapp was a silver-linings man of deep faith.“For was it not a wondrous work of God, to put it into the hearts of so many worthies to agree together, when times were so bad in England that they could not worship God after the due manner prescribed in his most holy word, but they must be imprisoned, excommunicated, etc., I say that so many should agree to make unto our sovereign lord the King to grant them and such as they should approve of, a Patent of a tract of land in this remote wilderness, a place not inhabited but by the barbarous nations? And was it not a wondrous good hand of God to incline the heart of our King freely to grant it, with all the privileges which the Patent [Massachusetts Bay Colony charter] expresseth? And what a wondrous work of God was it, to stir up such worthies to undertake such a difficult work, as to remove themselves and their wives and children from their native country, and to leave their gallant situations there, to come into this wilderness to set up the pure worship of God here — men fit for government in the magistracy and in families, and sound, learned, godly men for the ministry, and others that were very precious men and women, who came in the year 1630.”

Mary Dyer either gave birth during the 1635 voyage, or shortly after their arrival in Boston, because their second son, Samuel, was baptized in December 1635 at Boston First Church of Christ by Rev. John Wilson. Imagine being heavily pregnant or giving birth in a 300-400-ton ship rolling around in the Atlantic Ocean in hurricane season.

But if the Dyers and other early colonists were anything like Capt. Clapp, they took their difficult experiences as a challenge and necessary discipline as God’s chosen people, building the New Jerusalem society.****************

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

© 2015 by Christy K Robinson

A ship of the time, in 1638: William Rainsborough’s

A ship of the time, in 1638: William Rainsborough’s warship, Sovereign of the Sea, was used in the wars

of the Barbary Coast. Rainsborough, a contemporary

of Gov. John Winthrop, was the father of Winthrop’s

fourth wife, Martha, and of Judith, who married

Stephen Winthrop. Autumn 1635—Three hundred eighty years ago, William and Mary Dyer boarded an English ship with their Westminster neighbor, Henry Vane the Younger, and perhaps 100 others, and sailed to new Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony. No one knows the name of the ship or the exact date they arrived, but it probably arrived in October before one of the terrible winters of the Little Ice Age. Ship passages took an average of eight weeks if the winds were favorable, and up to twelve weeks if not.

The strongest hurricane ever to come ashore in New England made landfall in mid-August 1635, between Connecticut and Cape Cod, with massive 20-foot storm surges and winds that knocked down thousands of trees. Modern meteorologists estimate sustained winds of 135mph, from the descriptions of damages. Depending on which calendar historians used, Julian (old style) or Gregorian (new style, which we use now), the date for the hurricane is as early as August 13 or as late as August 26. Either way, the damage to shorelines and forest was still visible for many years.

Some historians have said that the eye of the storm passed between Boston and Plymouth. Native Americans in Narragansett Bay climbed high into trees to keep from being swept away by the waves. Gov. William Bradford of Plymouth Colony wrote, “Diverce vessels were lost at sea, and many more were in extreme danger… It caused ye sea to swell about 20 foote, right up & downe, and made many of the Indeans to clime into trees for their safetie.”

The 400-ton Great Hope, a ship full of passengers and their possessions, was just sailing into Massachusetts Bay when the gale struck them. They were driven aground near Charlestown, but when the wind shifted, they were blown back out on the Bay, and with the storm surge, pushed back aground at Charlestown. Those people survived, but a small pinnace broke up at Marblehead, and two families were washed away. On the pinnace, only Mr. and Mrs. Thacher survived, injured, but they lost all their children and goods.

Imagine leaving your home country, and being in sight of the shore of the Promised Land--and losing your entire family.

An English passenger ship, James, full of new immigrants (including my ancestors Hannah and John Ayers), nearly foundered as they came south along the New England coast, making for Boston. Rev. Increase Mather wrote, "At this moment,... their lives were given up for lost; but then, in an instant of time, God turned the wind about, which carried them from the rocks of death before their eyes. ...her sails rent in sunder, and split in pieces, as if they had been rotten ragges..."

Wikipedia: They tried to stand down during the storm just outside the Isles of Shoals, but lost all three anchors, as no canvas or rope would hold, but on Aug 13, 1635, torn to pieces, and not one death, all one hundred plus passengers of the James managed to make it to Boston Harbor.

There would have been search and rescue parties looking for survivors up and down the coast and small islands. I haven't found records of salvage operations, but the colonists were fully aware of their rights to salvage wreckage and possessions lost in shipwrecks.

August 1635 was about the time when the ship carrying the Dyers and Henry Vane would have left England to arrive by October, so it’s unlikely that they’d have been affected by that particular hurricane, unless the storm rode the Gulf Stream and they caught it in the North Atlantic. Even if they weren't caught in a tropical storm or hurricane themselves, they probably experienced high waves and winds from distant storms. There was always a high risk of violent storms.

Some of my research indicated that Puritans leaving England at that time had to swear loyalty to the King (the Dyers were royalists, so no problem there) and pay a large tax (or bribe) to be permitted to leave the country, so there’s speculation that some emigrants sneaked out on trading ships by way of Barbados and the Caribbean, and then up to Boston, which might be why not every emigrant shows up in passenger lists.

Ships rarely traveled alone. For armed protection from pirates, and to share resources (like physician or midwife), or if another ship needed repairs, they traveled in convoy. The ships carried not only the colonists and their many children, but their servants, the materials and tools the colonists needed to build homes, some livestock, seeds, furnishings, enough food for 18 months, clothing, guns and powder, and goods they couldn’t get or make in the wilderness of the New World. Privacy might have consisted of sheets hung from ropes. I’ve not seen a description of hygiene, but imagine that some passengers were seasick, others had diarrhea, there was animal waste, and children in nappies. Probably pregnant women and gassy men whose diet consisted of legumes and salted fish or meat. Although they could wash themselves with basins and towels, there weren't tubs or showers.

For John Winthrop's account of his fleet's 1630 arrival in New England, see http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2014/06/winthrop-fleet-fights-its-way-to-new.html

The Memoir of Captain Roger Clapp said that on board the ships, there were two sermons every day of the 70 days they were upon the deep. From the other paragraphs of his memoir, Capt. Clapp (my uncle about 14 generations back), describes this intensely religious sequestering as joyful and grace-filled, nothing like we’d consider with dread. He wrote of the frights and starvation of landing in Dorchester and trying to survive the polar vortexes of the Massachusetts winter, but Capt. Clapp was a silver-linings man of deep faith.“For was it not a wondrous work of God, to put it into the hearts of so many worthies to agree together, when times were so bad in England that they could not worship God after the due manner prescribed in his most holy word, but they must be imprisoned, excommunicated, etc., I say that so many should agree to make unto our sovereign lord the King to grant them and such as they should approve of, a Patent of a tract of land in this remote wilderness, a place not inhabited but by the barbarous nations? And was it not a wondrous good hand of God to incline the heart of our King freely to grant it, with all the privileges which the Patent [Massachusetts Bay Colony charter] expresseth? And what a wondrous work of God was it, to stir up such worthies to undertake such a difficult work, as to remove themselves and their wives and children from their native country, and to leave their gallant situations there, to come into this wilderness to set up the pure worship of God here — men fit for government in the magistracy and in families, and sound, learned, godly men for the ministry, and others that were very precious men and women, who came in the year 1630.”

Mary Dyer either gave birth during the 1635 voyage, or shortly after their arrival in Boston, because their second son, Samuel, was baptized in December 1635 at Boston First Church of Christ by Rev. John Wilson. Imagine being heavily pregnant or giving birth in a 300-400-ton ship rolling around in the Atlantic Ocean in hurricane season.

But if the Dyers and other early colonists were anything like Capt. Clapp, they took their difficult experiences as a challenge and necessary discipline as God’s chosen people, building the New Jerusalem society.****************

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed

(2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on August 25, 2015 23:44

August 10, 2015

Aug. 9-16: Chance to win a Dyer book at Unusual Historicals

Yes, you'll have to click another link, but there, you'll be able to read two articles on the Unusual Historicals website:

Yes, you'll have to click another link, but there, you'll be able to read two articles on the Unusual Historicals website:1. an excerpt from Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This, and

2. an author Q&A with Christy K Robinson. (Click the highlighted words to go there.) Clicking will open new tabs, so you won't have to leave this site.

On either of the posts, you can leave a comment (or question), with your email, to be entered in the drawing. The Unusual Historicals team will choose the lucky winner. The prize is an autographed paperback to US postal addresses, or a Kindle edition to US or international readers. After the drawing is made, the two articles will remain on their website.

Thinking about reading the Dyer books? You should, if you enjoy escaping to a different time and culture, and being entertained while you learn. And if you're a descendant of any of the following notable people, you could learn a lot about what your ancestors were doing and how they affected history.

William and Mary Barrett Dyer

William and Anne Marbury Hutchinson

Edward Hutchinson

Katherine Marbury Scott

Roger Williams

Sir Henry Vane

Nicholas Easton

Rev. John Cotton

Gov. John Winthrop Sr.

Capt. John Underhill

Gov. William Coddington

Nathaniel Sylvester of Shelter Island

Rev. John Davenport

Rev. John Wilson

Gov. John Endecott

Rev. Obadiah Holmes

Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick

The first Quaker missionaries

I recommend the paperback editions because they have character lists, maps, and extensive end notes. They're easier to refer to than the Kindle versions, though the Kindle contains exactly the same material. Where to find the books? http://bit.ly/DYERbooks

If you've read the books and would like to discuss them, why not hold a discussion group about them in your home, book club, or church hall? The author can speak with your small group by phone or Skype.

Published on August 10, 2015 15:53

July 20, 2015

The 17th century woman barbecues

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

Meat turns on spits at a cookhouse or tavern.

Meat turns on spits at a cookhouse or tavern.Gervase Markham’s book, The English Housewife, was published in 1615, when Mary Barrett (Dyer) was a small child, just the age to have to watch carefully around the large kitchen hearth with its multiple hot spots for roasting, baking, and boiling. She would have been raised to a familiarity with cooking for a household of adults, children, and servants.

We don’t know if she merely had an introduction to hearth cooking in order to supervise servants, or if she performed the work herself. But when the Dyers moved from London to new Boston in late 1635, and set up their home, they might have been short-handed until they were more firmly established. The chores for the colonial settlers were endless: candle-making, soap-making, beer brewing, food and herb gardening, domestic animal feeding, milking, and slaughter, cleaning, sewing and weaving, preparing summer food for winter storage, and a multitude of other tasks.

A look at Markham's barbecue lessons reveals that not much has changed in 400 years. Who doesn’t take primal satisfaction in food cooked over a fire, from steaks to S’mores to mystery-meat hot dogs? Vegetarians and vegans like a slight char on their vegetable skewer. People still love a barbecue meal, whether it’s a holiday party on the patio, or a sit-down in the restaurant.

What we'd call barbecued or grilled, Markham called meat that’s cooked over flames “carbonado.” That’s not far off what we call burned food: carbonized.

From The English Housewife, by Gervase Markham, 1615.

"The Cook" by Bernardo.On Carbonadoes

"The Cook" by Bernardo.On CarbonadoesCharbonadoes, or carbonadoes, which is meat broyled upon the coals (and the invention thereof was first brought out of France as appears by the name) are of divers kinds according to mens pleasures; for there is no meat either boyled or roasted whatsoever, but may afterwards be broyled if the master thereof be disposed, yet the general dishes which for the most part are to be carbonadoed, are a breast of Mutton half boyled; a shoulder of Mutton half roasted, the legs, wings, and carkasses of Capon, Turkey, Goose or any other fowl whatsoever, especially Land fowl.

What is to be carbonadoed

And lastly, the uttermost thick skin which covereth the ribbs of beef, and is called (being boyled,) the Inns of Court Goose, and is indeed a dish used most for wantonness, sometimes to please the appetite, to which may also be added the broyling of Pigs heads, or the brains of any fowl whatsoever after it is rosted and drest.

The manner of Carbonadoing

This scored meat was called "skotched." Now for the manner of Carbonadoing, it is in this sort; you shall first take the meat you must Carbonado, and scotch [score or cut deeply] it both above and below; then sprinkle good store of salt upon it, and baste it all over with sweet butter melted; which done, take your Broyling-iron, I do not mean a Grid-iron (though it be much used for those purpose) because of the smoak of the coals, occasioned by the dropping of the meat, will ascend about it, and make it stink: but a Plate iron made with hooks and pricks, on which you may hang the meat; and set it close before the fire, and so the Plate heating the meat behind, as the fire doth before, it will both the sooner and with more neatness be ready: then, having turned it, and basted it till it be very brown, dredge it, and serve it up with Vinegar and Butter.

This scored meat was called "skotched." Now for the manner of Carbonadoing, it is in this sort; you shall first take the meat you must Carbonado, and scotch [score or cut deeply] it both above and below; then sprinkle good store of salt upon it, and baste it all over with sweet butter melted; which done, take your Broyling-iron, I do not mean a Grid-iron (though it be much used for those purpose) because of the smoak of the coals, occasioned by the dropping of the meat, will ascend about it, and make it stink: but a Plate iron made with hooks and pricks, on which you may hang the meat; and set it close before the fire, and so the Plate heating the meat behind, as the fire doth before, it will both the sooner and with more neatness be ready: then, having turned it, and basted it till it be very brown, dredge it, and serve it up with Vinegar and Butter. "The Vegetable Stall" by Quiringh van Brekelenkam

"The Vegetable Stall" by Quiringh van BrekelenkamOf the toasting of Mutton

Touching the toasting of Mutton, Venison, or any joynt of Meat, which is the most excellentest of all Carbanadoes, you shall take the fattest and the largest that can possibly be got (for lean meat is less of flavour, and little meat not worth your time:) and having scotcht it and cast Salt upon it, you shall set it on a strong fork, with a dripping pan underneath it, before the face of a quick fire, yet so far off that it may be no means scorch, but toast at leasure; then with that which falls from it, and wiht no other basting, see that you baste it continually, turning it ever and anon many times and so oft that it may soak and brown at great leasure, and as oft as you baste it, to oft sprinkle Salt upon it, and as you see it toast, scotch it deeper and deeper, epecially in the thickest and most fleshy parts where the blood most resteth, and when you see that no more blood droppeth from it, but the gravy is clear and white, then you shall serve it up either with Venison sauce, with Vinegar, Pepper, and Sugar Cinnamon, and the juyce of an Orange mixt together, and warmed with some of the gravy.

*****

Christy K Robinson is the author of the series "The Dyers," which have five-star reviews. The books are available in paperback and Kindle versions on Amazon. Read the synopses and get the links here . <--Click highlighted link.

Published on July 20, 2015 23:40

June 20, 2015

William Dyer’s boyhood

© 2015 Christy K Robinson

There’s no biography or journal that can describe the boyhood of William Dyer, 1609-1677, but we can learn some details by looking at his background and what he studied as a boy and youth.

1615, boy with golf club,

1615, boy with golf club, unknown artist,

from the blog of

Barbara Wells Sarudy,

bit.ly/1TEOGFk

William Dyer’s father (also William) and grandparents probably came from the southern county of Somerset, but no connection is proven. He was a yeoman farmer in Kirkby LaThorpe, Lincolnshire, which means he owned his farm, in contrast to others who rented, and that was a sign of the rising middle class. It may be that even though he wasn’t the firstborn, his parents set him up with a substantial inheritance. Or maybe the money came from a financially advantageous marriage. Why he moved so far is a mystery, unless the land came to him by marriage or distant relationship (see below).

Our William was born and baptized in September 1609. He had an older brother, a younger sister, and perhaps more siblings who were miscarried or died as infants. In 1624, he was apprenticed in London, in a prestigious guild that produced councilmen and mayors for the city of London, and this was no mean accomplishment. So he must have been a worthy student as a boy. Where was he educated? Where did he learn that elegant penmanship that distinguishes his writing from the undecipherable scratchings of his Massachusetts and Rhode Island contemporaries?

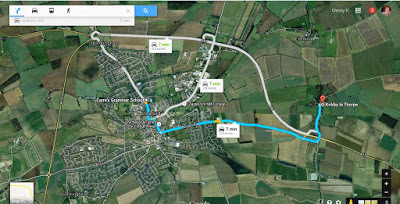

The current location of Carre's Grammar School may not be the exact

The current location of Carre's Grammar School may not be the exactlocation where William Dyer attended school, but it's probably close.

Screenshot from Google Maps, click to enlarge.Not quite three miles west of Kirkby LaThorpe, where William was born, is the larger town of Sleaford. It was a market and mill town lying near the Great Northern Road built by the Romans, and the Boston Road to the river port that led to the North Sea. Sleaford and surrounding lands were owned by the Catholic Church until the Dissolution under Henry VIII, then purchased and controlled by the Carre family. In 1581, during the reign of Elizabeth I, Robert Carre was High Sheriff of Lincolnshire. He’d been treasurer of the army when the Catholics of Northumberland and Durham rebelled against Protestant Queen Elizabeth. Sir Robert was married twice, but had no children. (Robert’s youngest brother, Edward Carre, married for the second time to an Anne Dyer and had three children with her before he died in 1618. There may be a distant relationshipbetween Anne Dyer Carre and our William Dyer, and the Carre family came from Somerset, too, but there’s no proof of a relationship. Dyer was a common name all over England. (If you’re doing genealogy, you need proof. This is circumstantial and does not constitute proof.)

In 1604, in one of many acts of benevolence, Sir Robert Carre founded a school for boys of all the nearby villages, called the Free Grammar School of Sleaford. A hundred-acre estate he’d inherited from his second wife endowed the school, and any excess funds were distributed as alms to the poor. Sir Robert died in 1606. The school has gone through a few tough times in 400 years, but lives today as a coeducational secondary school, Carre’s Grammar School.

Young William Dyer would have begun his formal education at the Free Grammar School, but at that time, a boy had to be able to read and write before he entered the school, so there would have been home-schooling even before. His father was a churchwarden, who recorded births, marriages, and deaths, and the history of the church: he was literate. Teaching little children to write their letters and numbers involved the child tracing large letters with a dry pen or chalk, then writing the figures repeatedly until they’d mastered one letter after the other.

William Dyer's handwriting in the 1640s. The curriculum for the early 17th-century grammar school consisted of religion, grammar (Latin and its translation, literature reading, rhetoric/composition), science, mathematics, and music. Writing was sometimes an extracurricular course, as we learn from this book. (See end of article for a how-to on teaching writing.) Grammar schools from Halifax to Southwark, Guildford to Durham, required that students speak Latin at school, not English. Schoolmasters appointed observers to enforce the practice.