Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 7

February 10, 2017

She persisted!

In honor of the persistence of Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who stood up for civil rights, and was silenced--but only until she could livestream the remainder of her remarks outside the Senate doors.

Four male Senators were allowed to read the letter that got Senator Warren silenced.

Click picture to enlarge

Click picture to enlarge

Four male Senators were allowed to read the letter that got Senator Warren silenced.

Click picture to enlarge

Click picture to enlarge

Published on February 10, 2017 22:28

January 30, 2017

Well, that wasn’t very nice

© 2017 Christy K Robinson

When the religious dissidents left (or were exiled from) Massachusetts Bay Colony in early 1638, they went first to the small town of Providence Plantations on the Seekonk River to meet with another dissident, Roger Williams, who had helped them negotiate with the Indians. Then they went on another few miles to the beautiful wooded island they’d purchased from the Native Americans during the extremely harsh winter when the Boston women were preparing to move their households (children, servants, household goods, domestic animals), the men were selling properties in Massachusetts and surveying and exploring their new island and Narragansett Bay, Mary Dyer was recovering from her traumatic miscarriage, and Anne Hutchinson was under house arrest in the home of one of the richest, most strict Puritans in New England, Joseph Weld.

When the religious dissidents left (or were exiled from) Massachusetts Bay Colony in early 1638, they went first to the small town of Providence Plantations on the Seekonk River to meet with another dissident, Roger Williams, who had helped them negotiate with the Indians. Then they went on another few miles to the beautiful wooded island they’d purchased from the Native Americans during the extremely harsh winter when the Boston women were preparing to move their households (children, servants, household goods, domestic animals), the men were selling properties in Massachusetts and surveying and exploring their new island and Narragansett Bay, Mary Dyer was recovering from her traumatic miscarriage, and Anne Hutchinson was under house arrest in the home of one of the richest, most strict Puritans in New England, Joseph Weld. The island was called Aquiday or Aquidneck (“the floating mass” or “island”), and the town they founded at the north end was first called Pocasset, the native name for “where the stream widens.” The Narragansett Bay is actually not an ocean bay, but an estuary for several rivers, so it does appear that you cross a river when you drive over the bridge from Massachusetts onto the island. Or in the 17th century, take a ferry or boat ride from the mainland.

Within two years of settlement, the island was The Isle of Rhodes or Rhode Island, and the town officially became Portsmouth.

But because of the heresy of the founders of Rhode Island, Governor John Winthrop called the place “the Isle of Error,” and that name was often used by other New England leaders in letters and journals.

The city and harbor of Newport, Rhode Island were founded and surveyed in 1639 by, among others, William Dyer. The deep-water harbor became the second-largest harbor and commerce center in New England after Boston, and traded in molasses and rum, horses and lumber, ship-building, food for the Caribbean plantations—and slaves. It was a center for smuggling and piracy. Mind you, Boston was no City Upon a Hill when it came to the same trade goods, piracy, and human trafficking, but Rhode Island had a bad reputation from the very beginning because of its religious tolerance and its rejection of a church-state government.

There were other names for the first colony to encode full religious liberty as law:Rogues Island: This pun was an early name for the colony, used in the time of the Dyers. But its nickname was renewed at the time of the American Revolution, and its popularity continues today in websites, newspapers, and a restaurant name. Asylum to evil-doers.The sink into which the other colonies empty their heretics. The sink-hole of New England, actually a 17th-century reference to the morals of its residents, but now useful as a meme.

That's actually a sinkhole!

That's actually a sinkhole!The licentious republic. A modern nickname I found while googling: Rude IslandThe receptacle of all sorts of riff-raff people.In 1657, two Dutch Reformed ministers reported their encounter with Quakers to their religious board in Amsterdam, that “We suppose they [the majority of the Quaker missionaries] went to Rhode Island; for that is the receptacle of all sorts of riff-raff people. … They left behind two strong young women. As soon as the ship had fairly departed, these began to quake and go into a frenzy, and cry out loudly in the middle of the street, that men should repent, for the day of judgement was at hand.”

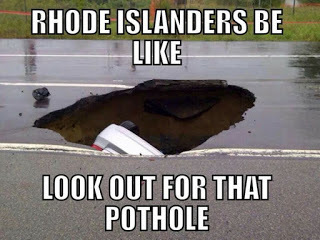

Caeca latrina. Probably the same two ministers (of the colony of New Amsterdam) sent this report to the Classis of Amsterdam. The Classis was the religious arm of the Dutch West Indies Company (WIC). The WIC appointed the governor to administer the colony’s business affairs, and the Classis provided Reformed, Calvinist ministers to serve the WIC’s towns and outposts. The Reformed doctrines were not far different from Puritan beliefs.

1658, Sept. 24th.[from] Revs. J. Megapolensis and S. Drisius

Reverend, Pious and Learned Fathers and Brethren in Christ: —

Your letter of May 26th last, (1658,) came safely to hand. We observe your diligence to promote the interests of the church of Jesus Christ in this province, that confusion may be prevented, and that the delightful harmony which has hitherto existed among us here, may continue. At the same time we rejoice that the Hon. Directors have committed this matter to you, and we hope that God will strengthen you in your laudable efforts. Last year we placed before you particularly the circumstances of the churches both in the Dutch and English towns. And as this subject has been placed by your Rev. body before the Hon. Directors, we hope that their honors will take into earnest consideration the sadly destitute circumstances of the English towns. …The raving Quakers have not settled down, but continue to disturb the people of the province by their wanderings and outcries. For although our government has issued orders against these fanatics, nevertheless they do not fail to pour forth their venom. There is but one place in New England where they are tolerated, and that is Rhode Island, which is the caeca latrina of New England. Thence they swarm to and fro sowing their tares.

A 17th-century anatomical illustration seems

A 17th-century anatomical illustration seemsto have the man flipping up his belly skin

to look at his own large and small

intestines. The letter went on to complain about a Lutheran minister that they didn’t like interfering with their Reformed churches and people.

Source: (Abstract of, in Acts of Deputies, Jan, 13, 1659. xx. 391.) https://books.google.com/books?pg=PA433&lpg=PA433&dq=caeca+latrina&sig=JVSVCS9zqu10HXu_CjS95XKfnYo&id=U3EAAAAAMAAJ&ots=2P2AE1C-z2&output=text

The Classis, and indeed the Netherlands government, was very tolerant of various religions in their country and colonies. The Reform church was prominent, but they tolerated Jews, Catholics and Protestants, Lutherans, Musselmen (Muslims), and English Separatists like the Pilgrims who came from England and later moved to Plymouth, Massachusetts. And Rev. Megapolensis himself had redeemed a French Catholic missionary who had been captured by the Mohawks of the Hudson River Valley. But it seems they had no tolerance for Quakers (like Mary Dyer) or rogues (like her husband, the privateer)! In the mid-1660s, New Netherland gave over control of their colony to the English and it was named New York, after James Stuart, Duke of York. Who was one of the first mayors of New York City in the 1670s? None other than William Dyer the Younger, the son of Mary and William Dyer. Few of my readers saw that coming!

What did the Dutch Reformed ministers mean by calling Rhode Island a caeca latrina? Caecum, in 17th century anatomy, was the colon or rectum (they used the term interchangeably). Latrina was the public toilet or sewer used by a military barracks. So the epithet of caeca latrina meant, basically, the outdoor toilets for feces, a.k.a. “number two” or “poop.” (One could go on, but surely you’ve heard other slang terms.)

Well, that wasn’t very nice.

***********

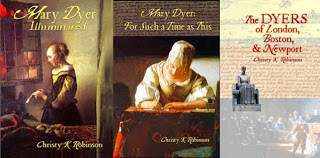

Christy K Robinson is the author of this award-winning blog and books on the notable people of 17th century England and New England. Click the links to find the books.

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on January 30, 2017 23:48

December 28, 2016

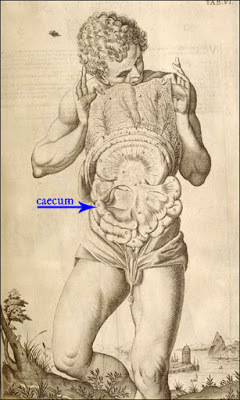

Life sketch: George Herbert versus the prosperity gospel

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

From time to time, I post a life sketch of people who were important members of 17th-century England and New England.

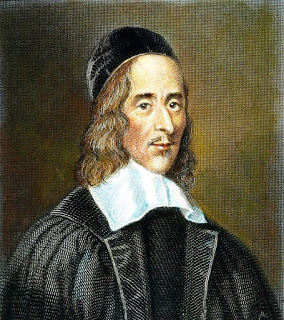

George Herbert, 1593-1633, was an English Parliamentarian, an orator (a spokesman for a college of Cambridge University), an author, a poet who was well connected with notables like Rev. John Dunne and scientist Francis Bacon, and the minister of a tiny chapel of ease just outside Salisbury, Wiltshire. He was one of ten children raised by a widowed mother, and homeschooled by her before he entered the prestigious schools at Westminster and Cambridge. He was married for only a few years before his death, and had no children. Rev. George Herbert

Rev. George Herbert

He was the creator of phrases and proverbs we still recognize today: "His bark is worse than his bite." "Living well is the best revenge.""Whose house is of glass must not throw stones at another." "The eye is bigger than the belly.""Half the world knows not how the other half lives."I used a poem by Herbert in my biographical novel of Mary and William Dyer, when Mary was walking from Providence, Rhode Island, to her arrest and certain death at Boston in 1660. On page 292 of Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This, I created a dialogue between Mary Dyer and Patience Scott, regarding George Herbert and his care for the poor, and for widows and orphans.

The Anglican pastor died of consumption (tuberculosis) at age 39, and was buried in front of the altar of the medieval chapel of St. Andrews, of which he was the rector, and that he rebuilt from his own funds. There is no effigy to mark his resting place or distract from the simplicity of the chapel’s purpose: to worship God and serve people.

A carved plaque is set into a wall of the rectory in Bemerton, Salisbury, where Herbert served in ministry to the poor for the last four years of his life. It’s a poem Herbert left for his successor in the ministry. Herbert’s legacy was no monumental work of art or vanity, it was his message and his poetry.To my Successor.If thou chance for to findA new House to thy mind,

And built without thy Cost:

Be good to the Poor,

As God gives thee store,

And then, my Labour’s not lost.

George Herbert would have had much to say about the income inequality of the twenty-first century, and the hijacking of the earnings, retirements, and healthcare of the poor and middle class by the politicians, oligarchs, and billionaire class. He would have spoken sharply against the so-called prosperity gospel advocates, who teach that those who “invest” in media ministries and morality watchdogs are financially blessed by God; that God makes people wealthy to show his blessing and favor.

But wait! Rev. Herbert did have an answer for that!“But perhaps being above the common people, our credit and estimation calls on us to live in a more splendid fashion; but O God! how easily is that answered, when we consider that the blessings in the holy Scripture are never given to the rich, but to the poor. I never find Blessed be the Rich, or Blessed be the Noble; but Blessed be the Meek, and Blessed be the Poor, and Blessed be the Mourners, for they shall be comforted.”

Mic drop.

*****To read more about George Herbert, click his hotlinked name at the top of this article. *****

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books and two history sites, three of the books revolving around the titans of New England. Click their titles to read the five-star reviews and purchase the paperback or Kindle editions.

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books and two history sites, three of the books revolving around the titans of New England. Click their titles to read the five-star reviews and purchase the paperback or Kindle editions.

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014)

From time to time, I post a life sketch of people who were important members of 17th-century England and New England.

George Herbert, 1593-1633, was an English Parliamentarian, an orator (a spokesman for a college of Cambridge University), an author, a poet who was well connected with notables like Rev. John Dunne and scientist Francis Bacon, and the minister of a tiny chapel of ease just outside Salisbury, Wiltshire. He was one of ten children raised by a widowed mother, and homeschooled by her before he entered the prestigious schools at Westminster and Cambridge. He was married for only a few years before his death, and had no children.

Rev. George Herbert

Rev. George HerbertHe was the creator of phrases and proverbs we still recognize today: "His bark is worse than his bite." "Living well is the best revenge.""Whose house is of glass must not throw stones at another." "The eye is bigger than the belly.""Half the world knows not how the other half lives."I used a poem by Herbert in my biographical novel of Mary and William Dyer, when Mary was walking from Providence, Rhode Island, to her arrest and certain death at Boston in 1660. On page 292 of Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This, I created a dialogue between Mary Dyer and Patience Scott, regarding George Herbert and his care for the poor, and for widows and orphans.

The Anglican pastor died of consumption (tuberculosis) at age 39, and was buried in front of the altar of the medieval chapel of St. Andrews, of which he was the rector, and that he rebuilt from his own funds. There is no effigy to mark his resting place or distract from the simplicity of the chapel’s purpose: to worship God and serve people.

A carved plaque is set into a wall of the rectory in Bemerton, Salisbury, where Herbert served in ministry to the poor for the last four years of his life. It’s a poem Herbert left for his successor in the ministry. Herbert’s legacy was no monumental work of art or vanity, it was his message and his poetry.To my Successor.If thou chance for to findA new House to thy mind,

And built without thy Cost:

Be good to the Poor,

As God gives thee store,

And then, my Labour’s not lost.

George Herbert would have had much to say about the income inequality of the twenty-first century, and the hijacking of the earnings, retirements, and healthcare of the poor and middle class by the politicians, oligarchs, and billionaire class. He would have spoken sharply against the so-called prosperity gospel advocates, who teach that those who “invest” in media ministries and morality watchdogs are financially blessed by God; that God makes people wealthy to show his blessing and favor.

But wait! Rev. Herbert did have an answer for that!“But perhaps being above the common people, our credit and estimation calls on us to live in a more splendid fashion; but O God! how easily is that answered, when we consider that the blessings in the holy Scripture are never given to the rich, but to the poor. I never find Blessed be the Rich, or Blessed be the Noble; but Blessed be the Meek, and Blessed be the Poor, and Blessed be the Mourners, for they shall be comforted.”

Mic drop.

*****To read more about George Herbert, click his hotlinked name at the top of this article. *****

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books and two history sites, three of the books revolving around the titans of New England. Click their titles to read the five-star reviews and purchase the paperback or Kindle editions.

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014)

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books and two history sites, three of the books revolving around the titans of New England. Click their titles to read the five-star reviews and purchase the paperback or Kindle editions.

Mary Dyer Illuminated

(2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

(2014)

The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport

(2014)

Published on December 28, 2016 23:49

November 10, 2016

The Leonid meteors: nothing new under the sun

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Every year in November, peaking at about the 17th of the month, a meteor shower can be seen, dropping tiny streaks of light. Some flashes are so slight that you think you’ve imagined them. Other meteors are so bright that they make the annual pilgrimage to the back yard lawn chair, in your warm bathrobe and thick socks, worth the 2am alarm clock call.

************* Boston supermoon in 2013. In 2016, we may not see many meteors because of the Nov. 14 "supermoon," when the full moon appears larger and brighter than any other in the 21st century. http://www.sciencealert.com/we-re-about-to-see-a-record-breaking-supermoon-the-biggest-and-brightest-in-nearly-70-years *************

Boston supermoon in 2013. In 2016, we may not see many meteors because of the Nov. 14 "supermoon," when the full moon appears larger and brighter than any other in the 21st century. http://www.sciencealert.com/we-re-about-to-see-a-record-breaking-supermoon-the-biggest-and-brightest-in-nearly-70-years *************

The mid-November Leonid meteor shower is caused by the dust particle trail of the Comet Tempel-Tuttle. Its journey around our solar system takes it close to the sun (perihelion) and the earth crosses that debris path of sand-sized particles, which strike our atmosphere and flare up on entry. Every 33 years, we pass through a zone of particles a little more dense than the other years, and that’s when we experience a more spectacular starfall.

I was educated in a Christian school where we learned in Bible class that the signs of Jesus’ second coming would be war, pestilence and plagues, earthquakes, deadly persecution of those who professed they followed him, offending one another, hate, false prophets, and taking the gospel to the entire world. (You might connect most of those with a US presidential election!)

But that wasn’t yet the end! There would be false prophets and those claiming to be the messiah and savior and who did miracles, and the “elect” or people who loved and served God would have to flee for their lives. Anne Hutchinson and her followers believed themselves to be the Elect, and when they were banished on pain of death, they felt it was confirmed. 1966 Leonid meteor storm--NASA photo.

1966 Leonid meteor storm--NASA photo.

How to find the Leo constellation from your back yard:

download the free app "SkEye" for Android or iOS, then

point your device at the eastern sky. The meteors will

come from the space between Regulus and the Big Dipper.

In the fullness of God's mysterious timing, that’s when the heavens and earth would be jolted. “The sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light; the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken” (Matt. 24:29), said Jesus, who may have been referring to the destruction of Jerusalem in 67-70AD, or of the final events of this world. Theologians disagree, but most say the similar heavenly events (that take place all at once) described in Revelation 6:12-15 point to the end of the world.

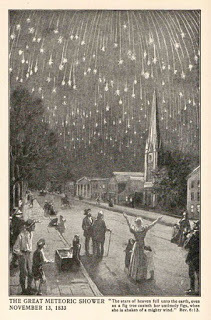

In Bible class, we were taught that the earthquake and tsunami at Lisbon in 1798 was The Big One, and that the sun and moon had darkened in the early 19th century (it was the result of a catastrophic forest fire in eastern Canada), and that the starfall on November 17, 1833, when the stars rained down in a terrifying and bright cascade for hours, fulfilled that prophecy.

Several religious movements sprang up in the 19th century, and they came out of New England, where the churches were still preaching like the hellfire and damnation sermons of the earliest Puritan ministers like John Wilson, Thomas Sheperd, John Cotton, Thomas Weld, Hugh Peter, John Davenport, Increase Mather, and others. Some of the new movements were the Latter-day Saints (Mormons), Millerites, Seventh-day Adventists, and later, Christian Science, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. They had in common that they believed that their law-keeping and pure lives would hasten the coming of the Lord, the world would soon be destroyed by sin, then be restored by God, and we would return in peace and live here eternally. (Understand that I’m being very broad here!)

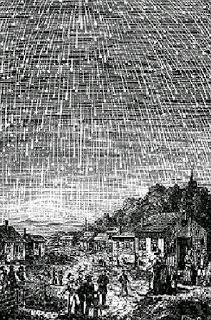

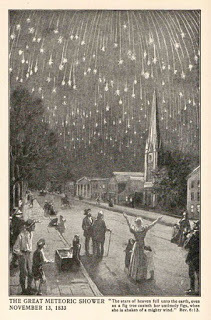

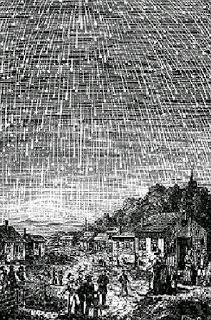

While the LDS and Millerites were in their infancy, the 1833 Leonid meteor shower produced its strongest showing in recorded history. It was one of the years in the 33-year cycle of Tempel-Tuttle comet dust, though the comet wouldn’t be named until 1866 (33 years later). "On the night of November 12-13, 1833, a tempest of falling stars broke over the Earth... The sky was scored in every direction with shining tracks and illuminated with majestic fireballs. At Boston, the frequency of meteors was estimated to be about half that of flakes of snow in an average snowstorm. Their numbers... were quite beyond counting; but as it waned, a reckoning was attempted, from which it was computed, on the basis of that much-diminished rate, that 240,000 must have been visible during the nine hours they continued to fall." - Agnes Clerke's Victorian Astronomy Writer

While the LDS and Millerites were in their infancy, the 1833 Leonid meteor shower produced its strongest showing in recorded history. It was one of the years in the 33-year cycle of Tempel-Tuttle comet dust, though the comet wouldn’t be named until 1866 (33 years later). "On the night of November 12-13, 1833, a tempest of falling stars broke over the Earth... The sky was scored in every direction with shining tracks and illuminated with majestic fireballs. At Boston, the frequency of meteors was estimated to be about half that of flakes of snow in an average snowstorm. Their numbers... were quite beyond counting; but as it waned, a reckoning was attempted, from which it was computed, on the basis of that much-diminished rate, that 240,000 must have been visible during the nine hours they continued to fall." - Agnes Clerke's Victorian Astronomy Writer

I used that 33-year cycle factoid when writing my first biographical novel, Mary Dyer Illuminated. Counting in 33-year intervals, I saw that 1635 was one of the peak years, and I wrote a scene about it. There was no journal entry for John Winthrop or the other historians regarding a meteor shower, perhaps because that year, the shower was seen better in Asia or Europe, or it might have been cloudy in Massachusetts. But it made a wonderful scene in which Mary Dyer experienced the Light of God that would shine at her very core in the last years of her life.

In the 17th century, every natural event was considered apocalyptic, from the hand of God. If you review the signs of Matthew 24, our ancestors and founders had endured religious persecution and fled from it. They’d experienced bubonic plague, smallpox, and typhus epidemics. On May 30-June 1, 1630, they’d seen a comet so bright that it, along with the noonday sun, cast a double shadow. There were religious-based wars in Europe. There was a great earthquake in New England on June 1, 1638, and a blood moon (annular eclipse) three weeks later. Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer, teaching the Covenant of Grace, were considered false prophets. When the Massachusetts exiles settled in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, they even called the men who believed they’d discovered new biblical truths “prophets,” because it meant that they’d be inspired or received a revelation from God. (Prophet didn’t mean a foreteller of events, but a messenger.) In Great Britain and Europe, new sects, including the Friends/Quakers, emerged and drew thousands of adherents away from established state denominations.

A Seventh-day Adventist illustration of the

A Seventh-day Adventist illustration of the

1833 starfall in New England.

"Lo, there was a great earthquake;

and the sun became black as

sackcloth of hair, and the moon became

as blood; And the stars of heaven

fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree

casteth her untimely figs, when she

is shaken of a mighty wind. And the

heaven departed as a scroll when it is

rolled together; and every mountain and island

were moved out of their places." Rev. 6:12-15You can understand why the experiences and observations of the first New England settlers were still resounding in the lives of the New Englanders (and prophets) who founded the 19th-century denominations whose beliefs revolved around “End Times.”

“In the year 2034, Earth is forecast to move through several clouds of dusty debris shed by comet Tempel-Tuttle from the years 1699, 1767, 1866 and 1932. If we’re lucky, we might see Leonids fall at the rate of hundreds per hour, perhaps briefly reaching "storm" rates of 1,000 per hour, experts have estimated.But sadly, in the year 2028, Jupiter is expected to throw comet Tempel-Tuttle off from its current path through space, making it all but impossible — at least through the beginning of the 22nd century — to see a repeat of the Great Leonid Storm of 1966.” http://www.space.com/13613-leonid-meteor-shower-peak-1966-storm.html

When you see a single shooting star, or a meteor shower, remember your ancestors, and their fascination and fear at seeing the same thing you see today. As the wise man said in Ecclesiastes, three thousand years ago,“What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

***********

Christy K Robinson is the author of this award-winning blog and books on the notable people of 17th century England and New England. Click the links to find the books.

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Every year in November, peaking at about the 17th of the month, a meteor shower can be seen, dropping tiny streaks of light. Some flashes are so slight that you think you’ve imagined them. Other meteors are so bright that they make the annual pilgrimage to the back yard lawn chair, in your warm bathrobe and thick socks, worth the 2am alarm clock call.

*************

Boston supermoon in 2013. In 2016, we may not see many meteors because of the Nov. 14 "supermoon," when the full moon appears larger and brighter than any other in the 21st century. http://www.sciencealert.com/we-re-about-to-see-a-record-breaking-supermoon-the-biggest-and-brightest-in-nearly-70-years *************

Boston supermoon in 2013. In 2016, we may not see many meteors because of the Nov. 14 "supermoon," when the full moon appears larger and brighter than any other in the 21st century. http://www.sciencealert.com/we-re-about-to-see-a-record-breaking-supermoon-the-biggest-and-brightest-in-nearly-70-years *************The mid-November Leonid meteor shower is caused by the dust particle trail of the Comet Tempel-Tuttle. Its journey around our solar system takes it close to the sun (perihelion) and the earth crosses that debris path of sand-sized particles, which strike our atmosphere and flare up on entry. Every 33 years, we pass through a zone of particles a little more dense than the other years, and that’s when we experience a more spectacular starfall.

I was educated in a Christian school where we learned in Bible class that the signs of Jesus’ second coming would be war, pestilence and plagues, earthquakes, deadly persecution of those who professed they followed him, offending one another, hate, false prophets, and taking the gospel to the entire world. (You might connect most of those with a US presidential election!)

But that wasn’t yet the end! There would be false prophets and those claiming to be the messiah and savior and who did miracles, and the “elect” or people who loved and served God would have to flee for their lives. Anne Hutchinson and her followers believed themselves to be the Elect, and when they were banished on pain of death, they felt it was confirmed.

1966 Leonid meteor storm--NASA photo.

1966 Leonid meteor storm--NASA photo.How to find the Leo constellation from your back yard:

download the free app "SkEye" for Android or iOS, then

point your device at the eastern sky. The meteors will

come from the space between Regulus and the Big Dipper.

In the fullness of God's mysterious timing, that’s when the heavens and earth would be jolted. “The sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light; the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken” (Matt. 24:29), said Jesus, who may have been referring to the destruction of Jerusalem in 67-70AD, or of the final events of this world. Theologians disagree, but most say the similar heavenly events (that take place all at once) described in Revelation 6:12-15 point to the end of the world.

In Bible class, we were taught that the earthquake and tsunami at Lisbon in 1798 was The Big One, and that the sun and moon had darkened in the early 19th century (it was the result of a catastrophic forest fire in eastern Canada), and that the starfall on November 17, 1833, when the stars rained down in a terrifying and bright cascade for hours, fulfilled that prophecy.

Several religious movements sprang up in the 19th century, and they came out of New England, where the churches were still preaching like the hellfire and damnation sermons of the earliest Puritan ministers like John Wilson, Thomas Sheperd, John Cotton, Thomas Weld, Hugh Peter, John Davenport, Increase Mather, and others. Some of the new movements were the Latter-day Saints (Mormons), Millerites, Seventh-day Adventists, and later, Christian Science, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. They had in common that they believed that their law-keeping and pure lives would hasten the coming of the Lord, the world would soon be destroyed by sin, then be restored by God, and we would return in peace and live here eternally. (Understand that I’m being very broad here!)

While the LDS and Millerites were in their infancy, the 1833 Leonid meteor shower produced its strongest showing in recorded history. It was one of the years in the 33-year cycle of Tempel-Tuttle comet dust, though the comet wouldn’t be named until 1866 (33 years later). "On the night of November 12-13, 1833, a tempest of falling stars broke over the Earth... The sky was scored in every direction with shining tracks and illuminated with majestic fireballs. At Boston, the frequency of meteors was estimated to be about half that of flakes of snow in an average snowstorm. Their numbers... were quite beyond counting; but as it waned, a reckoning was attempted, from which it was computed, on the basis of that much-diminished rate, that 240,000 must have been visible during the nine hours they continued to fall." - Agnes Clerke's Victorian Astronomy Writer

While the LDS and Millerites were in their infancy, the 1833 Leonid meteor shower produced its strongest showing in recorded history. It was one of the years in the 33-year cycle of Tempel-Tuttle comet dust, though the comet wouldn’t be named until 1866 (33 years later). "On the night of November 12-13, 1833, a tempest of falling stars broke over the Earth... The sky was scored in every direction with shining tracks and illuminated with majestic fireballs. At Boston, the frequency of meteors was estimated to be about half that of flakes of snow in an average snowstorm. Their numbers... were quite beyond counting; but as it waned, a reckoning was attempted, from which it was computed, on the basis of that much-diminished rate, that 240,000 must have been visible during the nine hours they continued to fall." - Agnes Clerke's Victorian Astronomy WriterI used that 33-year cycle factoid when writing my first biographical novel, Mary Dyer Illuminated. Counting in 33-year intervals, I saw that 1635 was one of the peak years, and I wrote a scene about it. There was no journal entry for John Winthrop or the other historians regarding a meteor shower, perhaps because that year, the shower was seen better in Asia or Europe, or it might have been cloudy in Massachusetts. But it made a wonderful scene in which Mary Dyer experienced the Light of God that would shine at her very core in the last years of her life.

In the 17th century, every natural event was considered apocalyptic, from the hand of God. If you review the signs of Matthew 24, our ancestors and founders had endured religious persecution and fled from it. They’d experienced bubonic plague, smallpox, and typhus epidemics. On May 30-June 1, 1630, they’d seen a comet so bright that it, along with the noonday sun, cast a double shadow. There were religious-based wars in Europe. There was a great earthquake in New England on June 1, 1638, and a blood moon (annular eclipse) three weeks later. Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer, teaching the Covenant of Grace, were considered false prophets. When the Massachusetts exiles settled in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, they even called the men who believed they’d discovered new biblical truths “prophets,” because it meant that they’d be inspired or received a revelation from God. (Prophet didn’t mean a foreteller of events, but a messenger.) In Great Britain and Europe, new sects, including the Friends/Quakers, emerged and drew thousands of adherents away from established state denominations.

A Seventh-day Adventist illustration of the

A Seventh-day Adventist illustration of the 1833 starfall in New England.

"Lo, there was a great earthquake;

and the sun became black as

sackcloth of hair, and the moon became

as blood; And the stars of heaven

fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree

casteth her untimely figs, when she

is shaken of a mighty wind. And the

heaven departed as a scroll when it is

rolled together; and every mountain and island

were moved out of their places." Rev. 6:12-15You can understand why the experiences and observations of the first New England settlers were still resounding in the lives of the New Englanders (and prophets) who founded the 19th-century denominations whose beliefs revolved around “End Times.”

“In the year 2034, Earth is forecast to move through several clouds of dusty debris shed by comet Tempel-Tuttle from the years 1699, 1767, 1866 and 1932. If we’re lucky, we might see Leonids fall at the rate of hundreds per hour, perhaps briefly reaching "storm" rates of 1,000 per hour, experts have estimated.But sadly, in the year 2028, Jupiter is expected to throw comet Tempel-Tuttle off from its current path through space, making it all but impossible — at least through the beginning of the 22nd century — to see a repeat of the Great Leonid Storm of 1966.” http://www.space.com/13613-leonid-meteor-shower-peak-1966-storm.html

When you see a single shooting star, or a meteor shower, remember your ancestors, and their fascination and fear at seeing the same thing you see today. As the wise man said in Ecclesiastes, three thousand years ago,“What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

***********

Christy K Robinson is the author of this award-winning blog and books on the notable people of 17th century England and New England. Click the links to find the books.

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014)The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on November 10, 2016 23:00

October 2, 2016

Centennial: An unlikely influence on lives and books

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Alf Wight on the moors

Alf Wight on the moors

overlooking the Dales.If I hadn’t read Alf Wight’s autobiographical books about his life and career as a veterinarian in the Yorkshire Dales, there might not have been a William and Mary Dyer website with a third of a million page views, nor the books* I’ve written about them and their world.

Alf Wight wrote under the pseudonym of James Herriot. Ah! You recognize that name. When I was a teenager, reading and rereading his books from All Creatures Great and Small to his Yorkshire travelogues shaped my expectations of and propelled my determination to visit the UK. My first visit there came 30 years after reading the first volume, but I’ve been there five times now, on research and sightseeing trips.

On the first trip, I was with a university study group, and as we rolled past the directional sign to Thirsk, where Wight had his vet practice, I may have left a face-print on the tour bus window, reminiscent of the Munch painting, The Scream.

On the first trip, I was with a university study group, and as we rolled past the directional sign to Thirsk, where Wight had his vet practice, I may have left a face-print on the tour bus window, reminiscent of the Munch painting, The Scream.

But on my next trip, I had a rental car, and Thirsk was on my itinerary for months before my plane left LAX. My stop was in the Yorkshire Dales, a series of valleys across north Yorkshire. Though they’re populated with farms, the Dales are a national park, with recreation sites and trails throughout the area. I was close to the town of Masham, the home of one branch of ancestors, and I stopped the car on the side of a shady road to get my bearings on the atlas (cars didn’t have GPS at that point). I was parked by a stone wall when I stepped out into damp grass and wildflowers, next to a brilliant-green field of fat, woolly sheep. The sweet scent of new-mown hay, flowers, and trees wet from a shower wafted to me, and I inhaled deeply. It was exactly as Wight had described his Yorkshire. I hadn’t read the books in 25 years and hadn’t expected it. But my first breath of the Dales was right out of James Herriot.

In Thirsk: the Herriot museum and the veterinary surgeryWhen I visited Thirsk, a small market town holding a weekly market day in its square (which I used in a Dyer book), I went into the James Herriot museum and shop, and though the beloved author had passed way, his son was there in the shop. I bought his biography of his father, The Real James Herriot, and had him sign it.

In Thirsk: the Herriot museum and the veterinary surgeryWhen I visited Thirsk, a small market town holding a weekly market day in its square (which I used in a Dyer book), I went into the James Herriot museum and shop, and though the beloved author had passed way, his son was there in the shop. I bought his biography of his father, The Real James Herriot, and had him sign it.

While in the northern county of Durham, I visited Raby Castle, the home of Henry Vane (which I used in a Dyer book). And in the Midlands near Bicester, my friend and I had supper in a small country pub that traced its history back to at least the 13thcentury. Its fireplace and low ceiling made it into one of my books.

On other visits to the UK, I visited abbeys, cathedrals, parish churches, large cities, and tiny villages. On the “tiny village” side of it, I drove through William Dyer’s boyhood neighborhood of Kirkby LaThorpe (which I used in a Dyer book), Lincolnshire and Norfolk fens (which I used in a Dyer book), and a farm with 16th-century house and barns (which I used in a Dyer book). On the big city end, St. Martin’s Lane in London (which I used in a Dyer book), and the area where William Dyer’s master, Walter Blackborne, and the Dyers themselves had lived (which I used in a Dyer book) became part of my memories and part of this website.

If you remember the delightful "All Creatures" books, Wight/Herriot described his disastrous dates with his future wife, at a hotel restaurant in Harrowgate. I drink their brand of tea, Yorkshire Gold. And I visited Bolton Castle, where he proposed to her. I only wish I could get the fabulous Wensleydale cheese in Arizona. Alas...

Bolton Castle

Bolton Castle

On October 3, 2016, Alf Wight (aka James Herriot) would have been 100 years old. He was a Scot who qualified as a veterinarian in 1939, just as Europe plunged into World War II. Stationed in Great Britain, he worked as a horse vet during the war, so he was able to visit his adopted home shire when he was on leave. After the war, he practiced on the Dales farms, as well as keeping office hours at his surgery in Thirsk. He was recovering from clinical depression in the 1960s when he began writing about Yorkshire as he’d known it before large-scale agriculture and commercial cattle farms changed the business. The first of his books was published in 1969, and they exploded worldwide in 1972. He passed away in 1995, and his son Jim, also a veterinary surgeon, has carried on the business.

One of the writing techniques I learned from the veterinarian was to pace a conversation or scene by using an animal's familiar mannerisms. In my books, I used dogs, cats, and even Canada geese to do that. Another device was humor, and in the dark and frightening days of England before the Great Migration, I made a young Puritan minister, Rev. Isaak Johnson, into a ray of sunshine who was a light to the dour, preachy John Winthrop. I was sorry to kill him off when the timeline said I must.

As touching and as comedic as Wight wrote his stories of Yorkshire life, some of the people uneducated and grouchy, some of them who risked their lives for their flocks and herds, Alf Wight didn’t make fun of the real people. (His son wrote that Alf changed names, dates, and locations, and denied that the stories were from real life because he was afraid the characters would recognize themselves and be hurt or angry. Yet one Yorkshireman was angry because he thought he hadn't been depicted in the books!) Alf Wight's superpower was making himself the butt of the joke, and lifting up his friends, family, and clients, often with humor, but always with love.

Happy birthday, James Alfred Wight. You changed my life. I hope that in turn, I’ve illuminated others’ lives.

*********** Christy K Robinsonis the author of this award-winning blog and books on the notable people of 17th century England and New England. Click the links to find the books. We Shall Be Changed Mary Dyer Illuminated Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Effigy Hunter

Christy K Robinsonis the author of this award-winning blog and books on the notable people of 17th century England and New England. Click the links to find the books. We Shall Be Changed Mary Dyer Illuminated Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Effigy Hunter

Alf Wight on the moors

Alf Wight on the moorsoverlooking the Dales.If I hadn’t read Alf Wight’s autobiographical books about his life and career as a veterinarian in the Yorkshire Dales, there might not have been a William and Mary Dyer website with a third of a million page views, nor the books* I’ve written about them and their world.

Alf Wight wrote under the pseudonym of James Herriot. Ah! You recognize that name. When I was a teenager, reading and rereading his books from All Creatures Great and Small to his Yorkshire travelogues shaped my expectations of and propelled my determination to visit the UK. My first visit there came 30 years after reading the first volume, but I’ve been there five times now, on research and sightseeing trips.

On the first trip, I was with a university study group, and as we rolled past the directional sign to Thirsk, where Wight had his vet practice, I may have left a face-print on the tour bus window, reminiscent of the Munch painting, The Scream.

On the first trip, I was with a university study group, and as we rolled past the directional sign to Thirsk, where Wight had his vet practice, I may have left a face-print on the tour bus window, reminiscent of the Munch painting, The Scream. But on my next trip, I had a rental car, and Thirsk was on my itinerary for months before my plane left LAX. My stop was in the Yorkshire Dales, a series of valleys across north Yorkshire. Though they’re populated with farms, the Dales are a national park, with recreation sites and trails throughout the area. I was close to the town of Masham, the home of one branch of ancestors, and I stopped the car on the side of a shady road to get my bearings on the atlas (cars didn’t have GPS at that point). I was parked by a stone wall when I stepped out into damp grass and wildflowers, next to a brilliant-green field of fat, woolly sheep. The sweet scent of new-mown hay, flowers, and trees wet from a shower wafted to me, and I inhaled deeply. It was exactly as Wight had described his Yorkshire. I hadn’t read the books in 25 years and hadn’t expected it. But my first breath of the Dales was right out of James Herriot.

In Thirsk: the Herriot museum and the veterinary surgeryWhen I visited Thirsk, a small market town holding a weekly market day in its square (which I used in a Dyer book), I went into the James Herriot museum and shop, and though the beloved author had passed way, his son was there in the shop. I bought his biography of his father, The Real James Herriot, and had him sign it.

In Thirsk: the Herriot museum and the veterinary surgeryWhen I visited Thirsk, a small market town holding a weekly market day in its square (which I used in a Dyer book), I went into the James Herriot museum and shop, and though the beloved author had passed way, his son was there in the shop. I bought his biography of his father, The Real James Herriot, and had him sign it. While in the northern county of Durham, I visited Raby Castle, the home of Henry Vane (which I used in a Dyer book). And in the Midlands near Bicester, my friend and I had supper in a small country pub that traced its history back to at least the 13thcentury. Its fireplace and low ceiling made it into one of my books.

On other visits to the UK, I visited abbeys, cathedrals, parish churches, large cities, and tiny villages. On the “tiny village” side of it, I drove through William Dyer’s boyhood neighborhood of Kirkby LaThorpe (which I used in a Dyer book), Lincolnshire and Norfolk fens (which I used in a Dyer book), and a farm with 16th-century house and barns (which I used in a Dyer book). On the big city end, St. Martin’s Lane in London (which I used in a Dyer book), and the area where William Dyer’s master, Walter Blackborne, and the Dyers themselves had lived (which I used in a Dyer book) became part of my memories and part of this website.

If you remember the delightful "All Creatures" books, Wight/Herriot described his disastrous dates with his future wife, at a hotel restaurant in Harrowgate. I drink their brand of tea, Yorkshire Gold. And I visited Bolton Castle, where he proposed to her. I only wish I could get the fabulous Wensleydale cheese in Arizona. Alas...

Bolton Castle

Bolton CastleOn October 3, 2016, Alf Wight (aka James Herriot) would have been 100 years old. He was a Scot who qualified as a veterinarian in 1939, just as Europe plunged into World War II. Stationed in Great Britain, he worked as a horse vet during the war, so he was able to visit his adopted home shire when he was on leave. After the war, he practiced on the Dales farms, as well as keeping office hours at his surgery in Thirsk. He was recovering from clinical depression in the 1960s when he began writing about Yorkshire as he’d known it before large-scale agriculture and commercial cattle farms changed the business. The first of his books was published in 1969, and they exploded worldwide in 1972. He passed away in 1995, and his son Jim, also a veterinary surgeon, has carried on the business.

One of the writing techniques I learned from the veterinarian was to pace a conversation or scene by using an animal's familiar mannerisms. In my books, I used dogs, cats, and even Canada geese to do that. Another device was humor, and in the dark and frightening days of England before the Great Migration, I made a young Puritan minister, Rev. Isaak Johnson, into a ray of sunshine who was a light to the dour, preachy John Winthrop. I was sorry to kill him off when the timeline said I must.

As touching and as comedic as Wight wrote his stories of Yorkshire life, some of the people uneducated and grouchy, some of them who risked their lives for their flocks and herds, Alf Wight didn’t make fun of the real people. (His son wrote that Alf changed names, dates, and locations, and denied that the stories were from real life because he was afraid the characters would recognize themselves and be hurt or angry. Yet one Yorkshireman was angry because he thought he hadn't been depicted in the books!) Alf Wight's superpower was making himself the butt of the joke, and lifting up his friends, family, and clients, often with humor, but always with love.

Happy birthday, James Alfred Wight. You changed my life. I hope that in turn, I’ve illuminated others’ lives.

***********

Christy K Robinsonis the author of this award-winning blog and books on the notable people of 17th century England and New England. Click the links to find the books. We Shall Be Changed Mary Dyer Illuminated Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Effigy Hunter

Christy K Robinsonis the author of this award-winning blog and books on the notable people of 17th century England and New England. Click the links to find the books. We Shall Be Changed Mary Dyer Illuminated Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Effigy Hunter

Published on October 02, 2016 00:00

September 23, 2016

1644 land deed sheds light on families of early Newport

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Newport Historical Society:

Newport Historical Society:

Molly Bruce Patterson, right, scanned or photographed

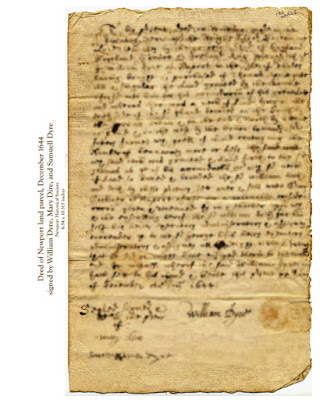

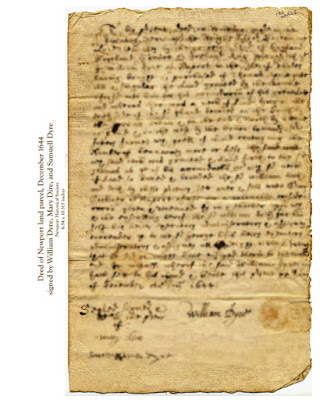

several documents, including the 1644 deed here. When in Newport, Rhode Island in July 2016, I had an appointment to meet an archivist at the Newport Historical Society, to view documents in William Dyer’s handwriting. Most of the records that William wrote, I was informed, are in Providence, the state capitol.

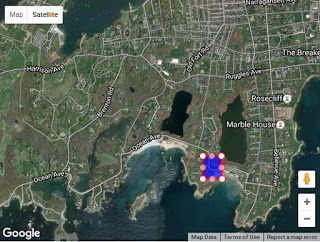

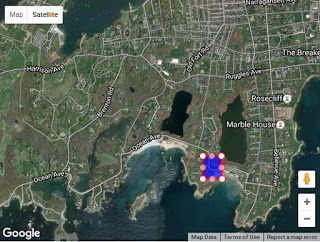

But they brought out a land deed from December 1644, and it has the signature of his wife, Mary Dyer! Further, under Mary’s name is the mark and first-name signature of their eldest son, Samuel. He would have been nine years old at the time, so it’s interesting that a child would be a witness to a legal transaction. By this time, Samuel had two younger brothers, William, about 4, and Maher, 1 year old.

The town of Newport was only five years old, and Robert Applegate had sold two pieces of land (that I know of so far) to William Dyer. William may have given part of it as a gift to his little boy, who had been baptized in December 1635 in Boston. And this land sale was made in December 1644, so it may have been connected to Samuel’s birthday. Did Samuel receive money or barter (sheep, a cow) from this sale? We’ll never know, but Samuel’s signature does mark a very human event for these families that we study, 370 years later.

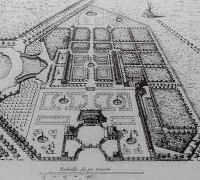

William bought 30 acres adjacent to his 87-acre farm on Newport’s west coast on May 5, 1644, from Thomas Applegate. But he also owned other parcels around the island, including land at the southernmost part of Aquidneck Island, and it appears that he bought 15 acres from Applegate on this rocky piece of land (with fantastic views) at the bottom of the island. In October 1644, he resold 10 acres of it to George Gardner, and again in December 1644, he sold four acres to Gardner. We don't know the dimensions of the farm William Dyer resold

We don't know the dimensions of the farm William Dyer resold

to George Gardner, but this is what a 15-acre parcel would

look like. William, in addition to other skills, was a surveyor,

so he knew geometry and could calculate an area. I used an

online calculator.

Who was Thomas Applegate? He’d been born in England in 1604, and emigrated to Boston in 1635. He was given the job of ferryman from Wessagusset (Weymouth) to Mt. Wollaston (Quincy), but he overloaded his boat and it capsized, drowning three people, so by court order, he was fined and his boat staved in. His wife Elizabeth was 'censured to stand with her tongue in a cleft stick for swearing, reviling, and railing' (Boston Court, Sept. 6, 1636). They moved to Newport in 1640, where Thomas was a weaver and owned several pieces of real estate. After he sold the southern-Newport farm to William Dyer in May 1644, Thomas and Elizabeth moved to Flushing, Long Island. There, he purchased land. In a court where his accusers had conflicts of interest, he was convicted of slander with a sentence of having his tongue bored with a red-hot poker; but he confessed his guilt and begged for mercy. He was pardoned. He died sometime between 1656 and 1662.

Tall native grasses and Queen Anne's

Tall native grasses and Queen Anne's

Lace grow in the place William Dyer

describes in the deed, land that became

George Gardner's farm.By the landmark descriptions, this part of Newport is now occupied by large, expensive homes with manicured grounds. When my friend Valerie drove me through the area on a tour, I noticed tall wild grasses (possibly spartina alterniflora, smooth cordgrass) with Queen Anne’s Lace and other flowers blooming along private drives. The native cordgrass would have been useful for thatching roofs. The soil is rocky, having been scraped by glaciers thousands of years ago. To the north is lovely green farmland with verdant trees. To the west is the estuary of Narragansett Bay. To the east is the Sakonnet River (actually a saltwater tidal body). And to the south is the Atlantic Ocean. View of a pond to the right, and the

View of a pond to the right, and the

Atlantic Ocean straight on, from the

guest room of my friend's home.

This is less than a mile from the

land described in the deed.

The transcription of the deed comes from my dear friend Jo Ann Butler, author of the historical fiction trilogy, Rebel Puritan . George Gardner and Herodias Long are Jo Ann’s ancestors. When I saw George’s name on the deed, I had to share it with her. To learn more about George and Herodias, visit the Rebel Puritan link and purchase Jo Ann's excellent books.

*************** I've purposely made the deed blurry

I've purposely made the deed blurry

to protect the interests of the

Newport Historical Society, which

charges a fee to scan documents.

But you can click to enlarge. This prsent deed or writing made in the [twentieth] yeare of the Raigne of Ye Soverigne Lord Charles by the grace of God of England Scotland ffrance & Ireland King wittnesseth yt I William Dyre of Nuport in the Ile of Rhodes having bought & purchased of Thomas Applegate All ye singular the Land granted by the colonie aforsd unto him for his accommodation of his granted Lott and whereas ther was a neck of Land lying on the South side of the sd Iland bounded on the South by the present Ocean & on the East & North by a [Cone] or pond & on the West by the Comon (towards Mr Fosters farme) wch prcell of Land containing the Number of four acres more or Less the said [will] wch said neck was granted & Laid forth to the sd Thomas as pt of his accommodation, & wch sd neck of Land so butted & bounded the sd William hath and doth by this presents for ever & sell unto Georg Gardiner of Nuport aforsd for a valeuable consideration given & [bargained] by on & th other upon wth & the unsealling herof the sd Wiliam doth for him self his heirs & executors administrators & assigns surrender up to the sd George his heirs & exctors administrators & assigns all right tittle & futour that he did or might have enjoyed therein to the worlds end for witness whereof the said William Dyre in hath sett to his hand & Seale this present XX day of December Ano Domy 1644: William Dyre

Sealed signed & [notice the darker paper by William's signature where the seal was]

Wthin the prsenc of: mary dire Samuell X Dyre [William Dyer signed Samuel's surname]

*************** Speaking of sealed, there’s a waxy, oily spot on the paper where a seal would have been before the deed was unsealed later, for George Gardner to sell the land. Seals are about the size of a dime. I would love to know what William’s seal looked like. Two engraved seals and a

Two engraved seals and a

silver pendant of an anchor seal

by Suegray Jewelry of Newport.

At this time, several men shared seals, and Roger Williams and Benedict Arnold were known to use the image of an anchor to seal documents. Three years later, in 1648, William Dyer presented the Rhode Island assembly, for which he was Recorder and then Secretary of State, with an ivory-handled seal that had an anchor and the word “Hope” on it. See my article at http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2014/03/william-dyer-and-rhode-island-state-seal.html The anchor/hope logo is still the symbol of the state of Rhode Island.

The paper was a yellowed "laid" paper, with texture lines rolled onto the paper when it was made. The paper was made of linen rags, and imported from England. There were no paper mills or factories in America until 1690.

Christy K Robinson is the author of this Dyer website and three five-star-reviewed books on the Dyers, available by clicking these links.

Christy K Robinson is the author of this Dyer website and three five-star-reviewed books on the Dyers, available by clicking these links.

We Shall Be Changed Mary Dyer Illuminated Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Effigy Hunter

Newport Historical Society:

Newport Historical Society: Molly Bruce Patterson, right, scanned or photographed

several documents, including the 1644 deed here. When in Newport, Rhode Island in July 2016, I had an appointment to meet an archivist at the Newport Historical Society, to view documents in William Dyer’s handwriting. Most of the records that William wrote, I was informed, are in Providence, the state capitol.

But they brought out a land deed from December 1644, and it has the signature of his wife, Mary Dyer! Further, under Mary’s name is the mark and first-name signature of their eldest son, Samuel. He would have been nine years old at the time, so it’s interesting that a child would be a witness to a legal transaction. By this time, Samuel had two younger brothers, William, about 4, and Maher, 1 year old.

The town of Newport was only five years old, and Robert Applegate had sold two pieces of land (that I know of so far) to William Dyer. William may have given part of it as a gift to his little boy, who had been baptized in December 1635 in Boston. And this land sale was made in December 1644, so it may have been connected to Samuel’s birthday. Did Samuel receive money or barter (sheep, a cow) from this sale? We’ll never know, but Samuel’s signature does mark a very human event for these families that we study, 370 years later.

William bought 30 acres adjacent to his 87-acre farm on Newport’s west coast on May 5, 1644, from Thomas Applegate. But he also owned other parcels around the island, including land at the southernmost part of Aquidneck Island, and it appears that he bought 15 acres from Applegate on this rocky piece of land (with fantastic views) at the bottom of the island. In October 1644, he resold 10 acres of it to George Gardner, and again in December 1644, he sold four acres to Gardner.

We don't know the dimensions of the farm William Dyer resold

We don't know the dimensions of the farm William Dyer resoldto George Gardner, but this is what a 15-acre parcel would

look like. William, in addition to other skills, was a surveyor,

so he knew geometry and could calculate an area. I used an

online calculator.

Who was Thomas Applegate? He’d been born in England in 1604, and emigrated to Boston in 1635. He was given the job of ferryman from Wessagusset (Weymouth) to Mt. Wollaston (Quincy), but he overloaded his boat and it capsized, drowning three people, so by court order, he was fined and his boat staved in. His wife Elizabeth was 'censured to stand with her tongue in a cleft stick for swearing, reviling, and railing' (Boston Court, Sept. 6, 1636). They moved to Newport in 1640, where Thomas was a weaver and owned several pieces of real estate. After he sold the southern-Newport farm to William Dyer in May 1644, Thomas and Elizabeth moved to Flushing, Long Island. There, he purchased land. In a court where his accusers had conflicts of interest, he was convicted of slander with a sentence of having his tongue bored with a red-hot poker; but he confessed his guilt and begged for mercy. He was pardoned. He died sometime between 1656 and 1662.

Tall native grasses and Queen Anne's

Tall native grasses and Queen Anne'sLace grow in the place William Dyer

describes in the deed, land that became

George Gardner's farm.By the landmark descriptions, this part of Newport is now occupied by large, expensive homes with manicured grounds. When my friend Valerie drove me through the area on a tour, I noticed tall wild grasses (possibly spartina alterniflora, smooth cordgrass) with Queen Anne’s Lace and other flowers blooming along private drives. The native cordgrass would have been useful for thatching roofs. The soil is rocky, having been scraped by glaciers thousands of years ago. To the north is lovely green farmland with verdant trees. To the west is the estuary of Narragansett Bay. To the east is the Sakonnet River (actually a saltwater tidal body). And to the south is the Atlantic Ocean.

View of a pond to the right, and the

View of a pond to the right, and the Atlantic Ocean straight on, from the

guest room of my friend's home.

This is less than a mile from the

land described in the deed.

The transcription of the deed comes from my dear friend Jo Ann Butler, author of the historical fiction trilogy, Rebel Puritan . George Gardner and Herodias Long are Jo Ann’s ancestors. When I saw George’s name on the deed, I had to share it with her. To learn more about George and Herodias, visit the Rebel Puritan link and purchase Jo Ann's excellent books.

***************

I've purposely made the deed blurry

I've purposely made the deed blurryto protect the interests of the

Newport Historical Society, which

charges a fee to scan documents.

But you can click to enlarge. This prsent deed or writing made in the [twentieth] yeare of the Raigne of Ye Soverigne Lord Charles by the grace of God of England Scotland ffrance & Ireland King wittnesseth yt I William Dyre of Nuport in the Ile of Rhodes having bought & purchased of Thomas Applegate All ye singular the Land granted by the colonie aforsd unto him for his accommodation of his granted Lott and whereas ther was a neck of Land lying on the South side of the sd Iland bounded on the South by the present Ocean & on the East & North by a [Cone] or pond & on the West by the Comon (towards Mr Fosters farme) wch prcell of Land containing the Number of four acres more or Less the said [will] wch said neck was granted & Laid forth to the sd Thomas as pt of his accommodation, & wch sd neck of Land so butted & bounded the sd William hath and doth by this presents for ever & sell unto Georg Gardiner of Nuport aforsd for a valeuable consideration given & [bargained] by on & th other upon wth & the unsealling herof the sd Wiliam doth for him self his heirs & executors administrators & assigns surrender up to the sd George his heirs & exctors administrators & assigns all right tittle & futour that he did or might have enjoyed therein to the worlds end for witness whereof the said William Dyre in hath sett to his hand & Seale this present XX day of December Ano Domy 1644: William Dyre

Sealed signed & [notice the darker paper by William's signature where the seal was]

Wthin the prsenc of: mary dire Samuell X Dyre [William Dyer signed Samuel's surname]

*************** Speaking of sealed, there’s a waxy, oily spot on the paper where a seal would have been before the deed was unsealed later, for George Gardner to sell the land. Seals are about the size of a dime. I would love to know what William’s seal looked like.

Two engraved seals and a

Two engraved seals and a silver pendant of an anchor seal

by Suegray Jewelry of Newport.

At this time, several men shared seals, and Roger Williams and Benedict Arnold were known to use the image of an anchor to seal documents. Three years later, in 1648, William Dyer presented the Rhode Island assembly, for which he was Recorder and then Secretary of State, with an ivory-handled seal that had an anchor and the word “Hope” on it. See my article at http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2014/03/william-dyer-and-rhode-island-state-seal.html The anchor/hope logo is still the symbol of the state of Rhode Island.

The paper was a yellowed "laid" paper, with texture lines rolled onto the paper when it was made. The paper was made of linen rags, and imported from England. There were no paper mills or factories in America until 1690.

Christy K Robinson is the author of this Dyer website and three five-star-reviewed books on the Dyers, available by clicking these links.

Christy K Robinson is the author of this Dyer website and three five-star-reviewed books on the Dyers, available by clicking these links.We Shall Be Changed Mary Dyer Illuminated Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport Effigy Hunter

Published on September 23, 2016 00:00

September 17, 2016

Shine on Harvest Moon

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

William Dyer, in addition to being the first Attorney General in America, a haberdasher and shipping investor, a cofounder of Newport, Rhode Island, a militia captain, surveyor, admiralty court judge, and Commander-in-Chief-Upon-the-Seas, was a farmer. He was the son of a farmer in Lincolnshire, and his sons were farmers and husbandmen (animal breeders).

William Dyer, in addition to being the first Attorney General in America, a haberdasher and shipping investor, a cofounder of Newport, Rhode Island, a militia captain, surveyor, admiralty court judge, and Commander-in-Chief-Upon-the-Seas, was a farmer. He was the son of a farmer in Lincolnshire, and his sons were farmers and husbandmen (animal breeders).

Mary Dyer, his wife, would have been occupied during the years for which we have no record, with managing their household and farm, and probably their financial accounting (as other women were known to do). She witnessed a property transfer, and she had a well-practiced hand at cursive and italic writing, so she might have carried on business correspondence or matters relating to the Dyers’ enterprises.

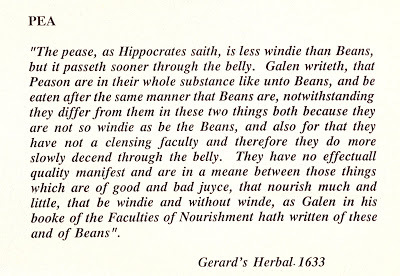

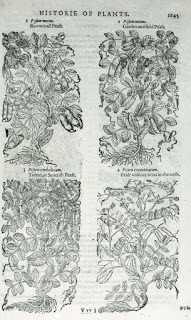

In household inventories taken for probate in England and New England, the books that many people owned were a family Bible (the Geneva Bible was preferred by Puritans) and an “herball.” The herbal book identified edible and medicinal plants and gave recipes for preparing them as remedies for injury and illness.

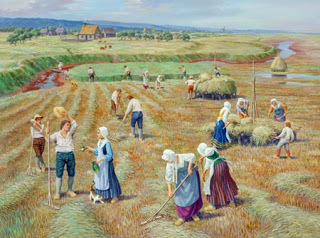

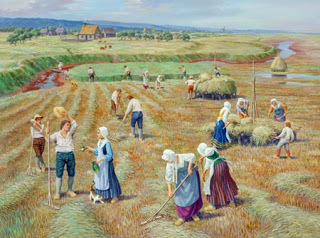

Early Acadia (Maine and eastern

Early Acadia (Maine and eastern

Canada), by Claude Picard,

mid-17th centuryOur New England ancestors had large home lots, sometimes two or three acres even in the towns, in order to plant gardens and orchards to supply the needs of their large households of children and servants. Many also held tracts of land in forest, marsh, and meadow, to provide for their sustenance, building materials, hunting, and crops.

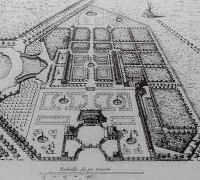

To judge by the woodcut images of the 16th and 17thcenturies, the home gardens were often planted in raised beds with walkways between them, something we’ve noticed making a comeback in cities where backyard gardeners cultivate tomatoes and salsa or salad veggies.

They had fruit and nut orchards, blackberry brambles, the raised beds for cultivated vegetables and legumes, and even shelves with round pots for herbs, as I saw in a woodcut. The formal gardens were laid out not only for ornamental delight, but to facilitate irrigation in droughts. The gardeners preferred fences made of wood, stone, and hedge, but not of earth because it held excess water to drown or mildew the plants.

Wheat, rye, barley and Indian corn, squash, melons, beans, peas, and other crops were grown in the larger fields. We’ve often heard that potatoes didn’t come on the scene for another century or two, but letters from the 1630s indicate that John Winthrop Jr., in Connecticut, had a plentiful supply of Virginia potatoes, shipped in from Bermuda, and one of his correspondents who lived in Saybrook, on Long Island Sound, grew potatoes.

Wheat, rye, barley and Indian corn, squash, melons, beans, peas, and other crops were grown in the larger fields. We’ve often heard that potatoes didn’t come on the scene for another century or two, but letters from the 1630s indicate that John Winthrop Jr., in Connecticut, had a plentiful supply of Virginia potatoes, shipped in from Bermuda, and one of his correspondents who lived in Saybrook, on Long Island Sound, grew potatoes.

One cash crop New Englanders planted that we usually connect with the American South is tobacco. But tobacco quickly robbed the soil of nutrients, and subsequent food crops failed, so famine was rampant. Combined with Little Ice Age late frosts, wet springs, and summer droughts, the meager fields weren’t always sufficient to feed families for a year. In early Newport, food supplies were inventoried household by household, and grain rations were redistributed in the lean winter months so no one would starve.

Wampanoag garden at Plimoth Plantation, July 2016.When the Plymouth colonists were planting their first crops in 1621, they were doing so in poor, sandy soil. The native Wamapanoags taught them what to plant and how to plant most effectively, and to “manure” (as the English called it) the seed hills with decomposing fish. The decomposition process both fertilized the soil and warmed it, a desirable outcome in the Little Ice Age. The “Three Sisters,” corn, beans, and squash, were planted together so that the bean vines climbed the corn stalks and returned nitrogen to the soil.

Wampanoag garden at Plimoth Plantation, July 2016.When the Plymouth colonists were planting their first crops in 1621, they were doing so in poor, sandy soil. The native Wamapanoags taught them what to plant and how to plant most effectively, and to “manure” (as the English called it) the seed hills with decomposing fish. The decomposition process both fertilized the soil and warmed it, a desirable outcome in the Little Ice Age. The “Three Sisters,” corn, beans, and squash, were planted together so that the bean vines climbed the corn stalks and returned nitrogen to the soil.

Some New England colonists’ food was foraged in forest and field: groundnuts and purslane (the latter is a common weed rich in omega fatty acids), wild berries, grapes, tree nuts, and other plants. Though purslane was popular as a salad ingredient in Europe, Native Americans considered it an inedible weed.

They ate bears?In addition to domestic animals and seafood, colonists ate wild game and fowl. William Dyer was sent with other men to trade goods with the Narragansett and Wampanoag Indians, for their venison. That was considered a more efficient way of obtaining venison than hunting, because of the risk of injury, getting lost in the forests, or musket accidents. They also ate animals that make us shudder in horror: squirrel, muskrat, raccoon, bear, and other creatures. (My northern Minnesota grandparents and their siblings ate bear, walleye pike, and venison during the Great Depression and World War II, to supplement their ration card foods.)

They ate bears?In addition to domestic animals and seafood, colonists ate wild game and fowl. William Dyer was sent with other men to trade goods with the Narragansett and Wampanoag Indians, for their venison. That was considered a more efficient way of obtaining venison than hunting, because of the risk of injury, getting lost in the forests, or musket accidents. They also ate animals that make us shudder in horror: squirrel, muskrat, raccoon, bear, and other creatures. (My northern Minnesota grandparents and their siblings ate bear, walleye pike, and venison during the Great Depression and World War II, to supplement their ration card foods.)

Back in Olde England, unless they were gentry, their diets had been mostly vegetarian with a bit of rabbit or chicken, or possibly fish for special occasions. Beef, venison, pork, and turkey were for the privileged class. Peas and beans were their staple diet, and "pease porridge in the pot nine days old" wasn't just a nursery rhyme--it was every meal for the common man. Dried peas were also a staple for ships' passengers and crew.

Back in Olde England, unless they were gentry, their diets had been mostly vegetarian with a bit of rabbit or chicken, or possibly fish for special occasions. Beef, venison, pork, and turkey were for the privileged class. Peas and beans were their staple diet, and "pease porridge in the pot nine days old" wasn't just a nursery rhyme--it was every meal for the common man. Dried peas were also a staple for ships' passengers and crew.

But in America, that was turned on its head. “Flesh” foods saved their lives when crops repeatedly failed. Giant lobsters caught off Maine and Massachusetts were disdained as food for servants, slaves, and dogs. In the late 1630s and 1640s, it was forbidden to butcher sheep or lambs for meat because they were still scarce, the colony needed to develop the wool industry, and they weren’t getting textiles from England during its civil wars. But they slaughtered wildlife by thousands and millions, according to William Wood's 1634 book, New-Englands Prospect.

Although I’ve seen second-hand references to almanacs that taught when to plant and harvest, by the phase of the moon, or the equinox or solstice, it’s been more difficult to find primary sources of that information, perhaps because modern agricultural practices are based on observed science and not religion-based (including pagan) views of astrology. See the examples from 17th-century herbal encyclopedias that I’ve reproduced at the end of this article.

Although I’ve seen second-hand references to almanacs that taught when to plant and harvest, by the phase of the moon, or the equinox or solstice, it’s been more difficult to find primary sources of that information, perhaps because modern agricultural practices are based on observed science and not religion-based (including pagan) views of astrology. See the examples from 17th-century herbal encyclopedias that I’ve reproduced at the end of this article.

Some lore suggests that the moon phases affecting bodies of water also affect animals and plants. Humans are more than 75 percent water-based, and our words lunatic and loony derive from centuries-old beliefs that erratic or insane behavior is heightened at the full or new moon because of our water content. From time immemorial, women have measured their menstrual cycles and fertility by the 28-day moon phases.

Traditional beliefs were that during a waxing (increasing) moon, it was the perfect time to plant seeds, and sow fields; but during the waning period beginning at the full moon, it was time for harvest, pruning, weeding, and drying of herbs or garden produce.

There are names assigned to the full moon in every month of the year, but the Harvest Moon is the full moon nearest the autumn equinox. It’s named so because the Harvest Moon occurs at the climax of the harvest season, so farmers can work late into the night by the moon's light. Illustration from Gerard's Herball, 1633.

Illustration from Gerard's Herball, 1633.

Click to enlarge.

There are also traditions about planting certain crops or garden foods in the winter or spring, by the moon phases. Carrots, parsnips, potatoes, onions, and other root plants that produce below the ground were planted during new moon because of the lower ground moisture that increased with the waxing of the moon and its tides.

Following are excerpts from some of the 17th-century herbal encyclopedias available online.

https://archive.org/details/neworchardgarden00laws A new orchard and garden: or, The best way for planting, grafting, and to make any ground good, for a rich orchard: particularly in the North and generally for the whole kingdom of England. With The country housewifes garden for herbes of common use, as also the husbandry of bees, all being the experience of 48. yeeres labour, and now the third time corrected and much enlarged by William Lawson, 1618

“Garden flowers shall suffer some disgrace, if among them you intermingle Onions, Parsnips, &c.”